Abstract

Postmenopausal estrogen deficiency accelerates bone mineral density (BMD) decline, significantly elevating the risk of osteoporotic fractures. Choline, a vital nutrient involved in lipid homeostasis and inflammatory pathways, has been associated with skeletal health. Yet its role in preserving bone density among postmenopausal populations, a group at high risk of osteoporosis, requires further investigation. This study also examined the modifying effects of socioeconomic factors, including income and race, on the relationship between dietary choline intake and BMD. Using data from 4,160 postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2018, we employed weighted linear regression models to characterize the dose-response relationship between total dietary choline intake and lumbar spine BMD. In fully adjusted models, each 1 g/day increment in choline intake corresponded to a 0.082 g/cm² increase in lumbar spine BMD (β: 0.082, 95% CI: 0.025–0.139). Participants in the highest choline intake quartile (Q4) exhibited a 0.025 g/cm² higher BMD compared to the lowest quartile (Q1) (β: 0.025, 95% CI: (0.007, 0.042)). Stratified analyses revealed significant effect modifications by obesity (P interaction = 0.015), income (P interaction = 0.003), and race (P interaction = 0.039), with amplified protective effects observed in obese individuals (β: 0.146, 95% CI: 0.067–0.22), high-income subgroups (PIR > 4)(β: 0.121, 95% CI: 0.013–0.228), and non-Hispanic Whites (β: 0.110, 95% CI: 0.034–0.185). This study demonstrates for the first time the positive association of dietary choline with BMD in postmenopausal women, supporting the potential of choline-targeted nutrition strategies for osteoporosis prevention and emphasizing the role of socioeconomic factors in influencing bone health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone mineral density (BMD), recognized as a gold standard for assessing bone strength, is characterized by a progressive decline that constitutes the central pathological feature of osteoporosis1. Postmenopausal women experience a sharp decline in estrogen levels, which markedly accelerates BMD depletion. The risk of osteoporotic fractures escalates when BMD falls below the diagnostic threshold (T-score ≤ -2.5)2,3. Osteoporosis-related fractures may lead to diminished quality of life, increased fracture-associated mortality, and substantial healthcare costs, with annual expenditures in the United States approximating $17.9 billion4,5. However, early-stage bone loss often remains clinically silent until osteoporotic fractures occur6. Therefore, identifying modifiable factors influencing BMD in postmenopausal women is critical for refining osteoporosis risk assessment and advancing targeted prevention strategies.

Choline, an essential dietary nutrient, is integral to multiple physiological processes. It underpins neural signaling, lipid homeostasis, and inflammatory regulation, supporting human health from early to old age7,8,9. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommends a daily choline intake of approximately 425 mg for postmenopausal women, a level considered sufficient to maintain critical functions such as liver health and neurological performance10. Although prior research has delineated associations between total choline intake and bone mineral density (BMD) in both elderly populations (≥ 65 years) and adolescents 11,12, the dose-dependent relationship between choline and BMD remains uncharacterized in postmenopausal women, the highest-risk demographic for osteoporotic fractures. Potential socioeconomic modifiers, such as income and racial disparities, have yet to be fully elucidated.

Here, we conducted a population-based cross-sectional study to quantify the association between total dietary choline intake and lumbar spine BMD in postmenopausal women and explore the potential modifying effects of socioeconomic factors.

Materials and methods

Data source and study population

The NHANES program, jointly administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), employs a demographically stratified sampling framework to evaluate health and nutritional metrics among community-dwelling U.S. residents. The cross-sectional initiative integrates multimodal data acquisition strategies, including structured interviews, clinical examinations, and biomarker analyses, to generate population-level health insights13. Ethical oversight for all procedures was provided by an institutional review board, with documented participant consent obtained before enrollment.

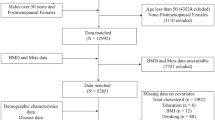

The current study analyzed data from the 2007–2018 NHANES cycles, excluding periods with missing bone density measurements (2011–2012 and 2015–2016). From an initial pool of 40,115 participants, we excluded individuals aged < 50 years (N = 28,163), males (N = 5,870), those with missing or non-postmenopausal status (N = 1,187), those lacking lumbar spine BMD data (N = 592), and those without dietary choline intake data (N = 143). The final analytical cohort comprised 4,160 postmenopausal women aged ≥ 50 years. A detailed flowchart of exclusion criteria is provided in Fig. 1.

Total dietary choline intake

Total dietary choline intake was calculated as the mean of two 24-hour dietary recalls, including both dietary and supplemental sources. Dietary intake was assessed using the USDA Automated Multiple-Pass Method, with the first recall conducted in-person at a mobile examination center and the second via telephone within 3–10 days14. Supplemental choline intake was self-reported, including the type and quantity of all dietary supplements.

Lumbar spine BMD

Lumbar spine BMD was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) by certified radiologic technologists. The lumbar 1, lumbar 2, lumbar 3, and lumbar 4 vertebral BMDs were averaged to represent the mean lumbar BMD for the outcome variable studied 15.

Definition of menopausal status

Menopausal status was determined via self-reported reproductive health questionnaires. Women who had not menstruated for ≥ 12 months due to natural menopause or hysterectomy were classified as postmenopausal16.

Covariates

Covariates were collected through questionnaires, physical examinations, and laboratory tests, including: Demographics: Age (< 65, ≥ 65 years), race (Mexican American, Other Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Other Race)17education (less than high school, high school, college or above), and poverty-to-income ratio (PIR: <1, 1–4, > 4). Lifestyle factors: Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²), physical activity level (categorized by intensity based on metabolic equivalent task [MET]-minutes per week: low moderate-to-vigorous physical activity [LMVPA], 1–599 MET-mins/week; moderate moderate-to-vigorous physical activity [MMVPA], 600–1199 MET-mins/week; and high moderate-to-vigorous physical activity [HMVPA], ≥ 1200 MET-mins/week), diabetes (self-reported diagnosis, insulin/oral hypoglycemic use, fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, or HbA1c ≥ 6.5%), family history of osteoporosis, and glucocorticoid use. Dietary factors: Mean carbohydrate intake (µg/day), mean dietary fiber intake (mg/day), and dairy consumption. Biochemical markers: Serum calcium (mg/dL), creatinine (mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase (U/L), alanine aminotransferase (U/L), alkaline phosphatase (IU/L), and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (nmol/L).

Detailed covariate definitions and data collection procedures are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Missing covariate data were imputed using mean substitution for normally distributed variables and median substitution for non-normally distributed variables.

Statistical analysis

To account for the stratified probability sampling methodology employed in NHANES, we incorporated survey weights to harmonize data across multiple collection waves, thereby enhancing the generalizability of findings to the broader U.S. demographic. For analytical consistency, primary analyses employed the WTDRD2 (Dietary two-day sample weight) weighting scheme, with WTDR1D (Dietary day one sample weight) weights serving as a fallback for cases lacking follow-up dietary recall data.

First, baseline characteristics of the weighted population were analyzed using descriptive statistics, with continuous variables expressed as means (standard errors) and categorical variables as percentages (95% CI)18. Comparative analyses employed weighted statistical tests: t-tests for continuous measures and chi-square tests for categorical variables 19. Three regression models were then used to control for confounders: model 1 was unadjusted, model 2 adjusted for age, race, education level, and proportion of families in poverty, and model 3 adjusted for age, race, education level, poverty/income ratio (PIR), obesity status, physical activity, diabetes, family history of osteoporosis, glucocorticoid use, dairy consumption, average carbohydrate intake (mg/d), average dietary fiber intake (mg/d), and serum calcium (mg/dL), blood creatinine (mg/dL), aspartate transferase (U/L), alanine transferase (U/L), alkaline phosphatase (IU/L), and serum 25-vitamin D3 (nmol/L).

To mitigate the potential impact of extreme values on the robustness of results across choline intake quartiles, outliers in dietary choline intake were identified and excluded using the interquartile range (IQR) method, a standard approach in nutritional epidemiology to enhance data validity and reduce bias20. Sensitivity analyses were conducted subsequently to verify the stability of observed associations after outlier exclusion21.

Additionally, smoothed curves were then fitted to assess whether there was a nonlinear relationship between total choline intake and mean lumbar spine BMD, with all covariates controlled. Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate potential interactions between dietary choline intake and key covariates, including age, race, household income, obesity status, physical activity level, dairy consumption, glucocorticoid use, family history of osteoporosis, and diabetes. All statistical analyses were performed using R Studio (version 4.2.2) and EmpowerStats (version 4.2), with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Participant characteristics

This study included 4,160 postmenopausal women aged ≥ 50 years, with the weighted sample representing 182 million U.S. postmenopausal women. Weighted baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Among the weighted population, 55.31% were aged < 65 years, and 43.66% were ≥ 65 years. The mean lumbar spine BMD in the weighted population was 0.95 g/cm². Participants were stratified into quartiles based on dietary choline intake. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed across quartiles for poverty-to-income ratio, education level, race, dairy consumption, dietary carbohydrate intake, dietary fiber intake, serum creatinine, and alkaline phosphatase. Compared to the lowest quartile (Q1), the highest quartile (Q4) exhibited distinct sociodemographic and metabolic profiles: higher income (41.25% with PIR > 4), higher education (63.89% with college or above), predominance of non-Hispanic Whites (76.23%), and greater intake of dietary fiber and dairy products (all P < 0.01). No significant differences were observed for age, obesity status, glucocorticoid use, family history of osteoporosis, physical activity level, diabetes, serum calcium, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, or serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (all P > 0.05).

Association between dietary choline intake and lumbar spine BMD

In Table 2, we used three linear regression models to examine the independent association between total choline intake and lumbar spine BMD. Model 1 (unadjusted) revealed a significant positive association (β: 0.101, 95% CI: 0.034–0.167), which persisted in Model 2 (adjusted for demographic variables: β: 0.090, 95% CI: 0.026–0.155) and Model 3 (fully adjusted for all covariates: β: 0.082, 95% CI: 0.025–0.139). These findings indicate that each 1 g/day increase in dietary choline intake was associated with a 0.082 g/cm² increase in lumbar spine BMD. Quartile-based analyses yielded consistent results, with the highest quartile (Q4) showing a 0.025 g/cm² higher BMD compared to the lowest quartile (Q1) (β: 0.025, 95% CI: 0.007–0.042; P for trend = 0.0234).

Considering that extreme values might affect the robustness of the results, sensitivity analyses were performed excluding outliers identified by the interquartile range (IQR) method. These sensitivity analyses produced results consistent with the primary findings, reinforcing that the observed associations are stable and not unduly influenced by extreme dietary choline intake. Detailed results from these analyses are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Additionally, the smoothed curve-fitting results further demonstrated a positive correlation between total choline intake and mean BMD of the lumbar spine (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analyses

Finally, subgroup analyses evaluated the stability of the choline-BMD association across population strata, stratified by age, PIR, education level, obesity status, physical activity level, dairy consumption, glucocorticoid use, family history of osteoporosis, and diabetes. Significant interactions were observed for obesity status (Pinteraction = 0.015), race (Pinteraction = 0.039), and income level (Pinteraction = 0.003) in Table 3. Specifically, stronger associations were observed in non-Hispanic Whites (β: 0.110, 95% CI 0.034, 0.185), obese individuals (β: 0.146, 95% CI: 0.067, 0.22), and high-income groups (PIR > 4)(β: 0.121, 95% CI 0.013, 0.228). No significant interactions were detected for age, physical activity, or diabetes (all Pinteraction > 0.05).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of 4,160 postmenopausal women, we found that total dietary choline intake—whether analyzed as a continuous or categorical variable—was positively and linearly associated with lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) in fully adjusted models. Notably, subgroup analyses revealed significant metabolic and population heterogeneity in this association, with stronger effects observed in obese individuals, high-income groups, and non-Hispanic Whites. These findings provide critical evidence for precision nutrition interventions targeting osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

Choline, an essential nutrient, serves as a key component of phosphatidylcholine and a precursor to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. It plays a central role in lipid homeostasis, membrane integrity, and inflammatory regulation8. Recent studies have explored the relationship between choline and bone health. For instance, a cross-sectional analysis of NHANES 2005–2018 data identified a positive association between dietary choline intake and BMD in male adolescents, suggesting that choline supplementation may support bone development during growth 12. Similarly, an analysis of NHANES 2005–2010 data found that low dietary choline intake was an independent risk factor for osteoporosis in older U.S. adults (> 65 years)11. However, these studies did not focus on postmenopausal women, the group with the most rapid bone loss, nor did they examine socioeconomic modifiers (e.g., income, race) of choline’s effects.

Our study quantified the relationship between dietary choline intake and lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) in postmenopausal women, showing that for every 1 g increase in choline intake, BMD increased by 0.082 g/cm². It is well known that one large egg contains approximately 147 mg of choline; therefore, consuming about two-thirds of a large egg per day (roughly 100 mg of choline) corresponds to an approximate increase of 0.0082 g/cm² in BMD. The clinical significance of an increase of 0.0082 g/cm² in BMD warrants further discussion. Notably, a previous study demonstrated that an increase in BMD as small as 0.01 g/cm² is associated with a significant reduction in hip fracture risk22. This suggests that an additional daily intake equivalent to two-thirds of an egg, resulting in a BMD increase of 0.0082 g/cm², may have clinically meaningful benefits. Other foods, such as chicken liver and beef liver—each containing approximately 356 mg of choline per 3 ounces—can also substantially contribute to choline intake and potentially further improve bone density. However, the current study did not include fracture data, which limits our ability to assess whether the observed increases in BMD translate into reduced fracture rates. Future studies incorporating fracture outcomes are warranted to better evaluate the clinical relevance of these findings.

This study establishes the first evidence of a positive dose-response relationship between dietary choline intake and lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) in postmenopausal women, though the mechanistic underpinnings require further elucidation. Current evidence points to choline’s multifactorial skeletal protection through interconnected biological pathways. Functioning as a betaine precursor, choline contributes to one-carbon metabolism, facilitating homocysteine remethylation and thereby reducing serum homocysteine levels—a recognized biomarker associated with accelerated bone loss and fracture risk23. This metabolic pathway may be especially relevant in postmenopausal women, where estrogen depletion suppresses phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) activity, as shown in preclinical studies, leading to increased reliance on dietary choline to sustain bone remodeling homeostasis24. Furthermore, choline may mitigate estrogen deficiency-induced pro-inflammatory states—marked by elevated TNF-α and IL-6—by inhibiting NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathways, thereby reducing inflammation-driven osteoclastogenesis 25. Therefore, estrogen may be a potential modulator of the relationship between dietary choline intake and bone mineral density (BMD) in postmenopausal women. However, due to insufficient estrogen data in the current cycle, further analysis could not be performed. This presents an important avenue for future research.

Our subgroup analyses revealed that obesity significantly modified the association between dietary choline intake and lumbar spine BMD. This may be explained by higher endogenous estrogen production in obese individuals due to increased aromatase activity in adipose tissue, which converts androgens to estrogens, thereby supporting bone maintenance26. This biological mechanism offers a plausible explanation for the significant interaction between obesity and the choline-BMD relationship. Additionally, we observed significant interactions by race and socioeconomic status. Higher choline intake among African Americans, along with genetic and metabolic differences, may influence BMD outcomes27,28. Moreover, greater access to choline-rich foods and supplements in higher-income groups could amplify osteoprotective effects 29. These findings highlight the complex interplay of hormonal, genetic, metabolic, and socioeconomic factors in modulating choline’s impact on bone health, underscoring the need for tailored nutrition strategies.

This study benefits from several methodological strengths, including the use of the nationally representative NHANES database, a large sample size (N = 4,160), and complex survey weighting to ensure generalizability to the U.S. postmenopausal population. The robust adjustment for demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and biochemical confounders enhances the validity of the observed association.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, and reliance on 24-hour dietary recalls for estimating choline intake may introduce measurement errors, particularly due to dietary variability. Self-reported dietary data are susceptible to recall and reporting biases, potentially resulting in over- or underestimation of actual choline intake. This limitation is inherent in the 24-hour recall methodology employed in NHANES30. Secondly, the limited availability of estradiol data prevented subgroup analyses based on estrogen levels, which may have modulated the relationship between choline intake and bone mineral density (BMD). This highlights the need for future research to explore the role of estrogen deficiency in this association. Finally, residual confounding from unmeasured genetic or environmental factors may persist despite comprehensive covariate adjustment. Future studies should prioritize longitudinal designs incorporating objective biomarkers of choline metabolism (e.g., plasma phosphatidylcholine) and repeated dietary assessments to establish temporality. Furthermore, Mendelian randomization approaches could help disentangle confounding factors and provide stronger evidence for precision nutrition interventions aimed at osteoporosis prevention.

Conclusions

The cross-sectional study is the first to demonstrate a significant linear dose-response relationship between total dietary choline intake and lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) in postmenopausal women aged ≥ 50 years (β = 0.082, 95% CI: 0.025–0.139). The association was particularly pronounced in obese individuals (β = 0.146), high-income subgroups (PIR > 4; β = 0.121), and non-Hispanic Whites (β = 0.110). These findings suggest that optimizing dietary choline intake may serve as a cost-effective intervention strategy for improving bone health in postmenopausal women.

Data availability

All NHANES data for this study are publicly available and can be found here: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

References

Hamdy, R. C. Bone mineral density and fractures. J. Clin. Densitom. 19, 125–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocd.2016.03.012 (2016).

Kanis, J. A., Cooper, C., Rizzoli, R. & Reginster, J. Y. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos. Int. 30, 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4704-5 (2019).

Clark, P., Tamayo, J. A., Cisneros, F., Rivera, F. C. & Valdés, M. Epidemiology of osteoporosis in mexico. Present and future directions. Rev. Invest. Clin. 65, 183–191 (2013).

Osteoporosis prevention. diagnosis, and therapy. Jama 285, 785–795. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.6.785 (2001).

Clynes, M. A. et al. The epidemiology of osteoporosis. Br. Med. Bull. 133, 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldaa005 (2020).

Tothill, P. Methods of bone mineral measurement. Phys. Med. Biol. 34, 543–572. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/34/5/001 (1989).

Gallo, M., Gámiz, F. & Choline An essential nutrient for human health. Nutrients 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132900 (2023).

Wiedeman, A. M. et al. Dietary Choline Intake: Current State of Knowledge Across the Life Cycle. Nutrients 10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10101513

Goh, Y. Q., Cheam, G. & Wang, Y. Understanding choline bioavailability and utilization: first step toward personalizing choline nutrition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 10774–10789. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.1c03077 (2021).

Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline (National Academies, 1998). https://doi.org/10.17226/6015

Zhang, Y. W. et al. Low dietary choline intake is associated with the risk of osteoporosis in elderly individuals: a population-based study. Food Funct 12, 6442-6451 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1039/d1fo00825k

Gong, H., Jiang, J., Choi, S. & Huang, S. Sex differences in the association between dietary choline intake and total bone mineral density among adolescents aged 12–19 in the united States. Front. Nutr. 11, 1459117. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1459117 (2024).

Frank, S. M. et al. Adherence to the planetary health diet index and correlation with nutrients of public health concern: an analysis of NHANES 2003–2018. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 119, 384–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.10.018 (2024).

Lu, L. & Ni, R. Association between polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure and hypertension among the U.S. Adults in the NHANES 2003–2016: A cross-sectional study. Environ. Res. 217, 114907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.114907 (2023).

Xie, R., Huang, X., Liu, Q. & Liu, M. Positive association between high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and bone mineral density in U.S. Adults: the NHANES 2011–2018. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17, 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-02986-w (2022).

Tang, Y. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: A cross-sectional study of the National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2007–2018. Front. Immunol. 13, 975400. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.975400 (2022).

Cave, C. et al. Omega-3 Long-Chain polyunsaturated fatty acids intake by ethnicity, income, and education level in the united states: NHANES 2003–2014. Nutrients 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12072045 (2020).

Ye, W., Li, X. & Huang, Y. Relationship between physical activity and adult asthma control using NHANES 2011–2020 data. Med. Sci. Monit. 29, e939350. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.939350 (2023).

Feng, G., Huang, S., Zhao, W. & Gong, H. Association between life’s essential 8 and overactive bladder. Sci. Rep. 14, 11842. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62842-1 (2024).

Mramba, L. K. et al. Detecting potential outliers in longitudinal data with time-dependent covariates. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 78, 344–350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-023-01393-6 (2024).

Tajima, R. et al. Association of alcohol consumption with prevalence of fatty liver after adjustment for dietary patterns: Cross-sectional analysis of Japanese middle-aged adults. Clin. Nutr. 39, 1580–1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2019.07.001 (2020).

Cawthon, P. M. et al. Change in hip bone mineral density and risk of subsequent fractures in older men. J. Bone Min. Res. 27, 2179–2188. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.1671 (2012).

Horita, D. A. et al. Two methods for assessment of choline status in a randomized crossover study with varying dietary choline intake in people: isotope Dilution MS of plasma and in vivo single-voxel magnetic resonance spectroscopy of liver. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 113, 1670–1678. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa439 (2021).

Zhan, X. et al. Choline supplementation regulates gut Microbiome diversity, gut epithelial activity, and the cytokine gene expression in gilts. Front. Nutr. 10, 1101519. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1101519 (2023).

Zhang, L., Zheng, Y. L., Wang, R., Wang, X. Q. & Zhang, H. Exercise for osteoporosis: A literature review of pathology and mechanism. Front. Immunol. 13, 1005665. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1005665 (2022).

Kuryłowicz, A. Estrogens in adipose tissue physiology and Obesity-Related dysfunction. Biomedicines 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11030690 (2023).

Al-Barazenji, T. et al. Association between vitamin D receptor BsmI polymorphism and low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women in the MENA region. Pathophysiology 32 https://doi.org/10.3390/pathophysiology32010006 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Correlation of metabolic markers and OPG gene mutations with bone mass abnormalities in postmenopausal women. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 19, 706. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-024-05162-4 (2024).

Mokari-Yamchi, A., Omidvar, N., Tahamipour Zarandi, M. & Eini-Zinab, H. The effects of food taxes and subsidies on promoting healthier diets in Iranian households. Front. Nutr. 9, 917932. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.917932 (2022).

Saxby, S. M. et al. Feasibility and assessment of self-reported dietary recalls among newly diagnosed multiple sclerosis: a quasi-experimental pilot study. Front. Nutr. 11, 1369700. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1369700 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control for designing, collecting, and collating the NHANES data and creating the public database.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B. participated in the conceptualization and methodology of the study. J.B. and P.L. carried out the methodology. J.B. and L.L. contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of data. J.B. and S.C. performed the statistical analysis. J.B. wrote the manuscript and tables. J.B. prepared the figures. J.C. supervised the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

All participants provided informed consent before enrollment.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, J., Lv, P., Li, L. et al. Association between total dietary choline intake and lumbar spine bone mineral density in postmenopausal women based on NHANES 2007–2018. Sci Rep 15, 23483 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08891-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08891-6