Abstract

Hypertensive left ventricular (LV) remodeling may influence coronary artery pathology due to anatomical proximity, yet its association with coronary chronic total occlusion (CTO) remains unclear. This cross-sectional, hypothesis-generating study included patients with coexisting coronary artery disease (CAD) and hypertension. LV geometry was classified by echocardiography as normal, concentric remodeling (CR), concentric hypertrophy (CH), or eccentric hypertrophy (EH). CTO was identified by coronary angiography. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between LV geometry and CTO incidence. A total of 3430 patients were included, with a mean age of 65.3 years and 68.9% male. LV remodeling was present in 2427 (70.8%) patients. CTO lesions were identified in 300 (8.7%) patients, with incidence rates of 6.1% in normal geometry, 6.9% in CR, 9.9% in CH, and 12.7% in EH. Compared to normal geometry, LV remodeling was associated with a higher risk of CTO (OR, 1.696; 95% CI 1.258–2.285, p = 0.001), particularly in patients with CH (OR, 1.798; 95% CI 1.276–2.535, p = 0.001) and EH (OR, 2.355; 95% CI 1.656–3.349, p < 0.001). These observational findings suggest an association between LV remodeling and CTO in hypertensive CAD patients, although causal inference remains limited and further prospective investigations are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is a leading global health burden, accounting for around 30% of all deaths worldwide1. Among these, hypertension and coronary artery disease (CAD) are highly prevalent comorbidities, with more than 45% of CAD patients also diagnosed with hypertension2.

Hypertension leads to chronic pressure overload, which in turn causes adaptive structural changes in the left ventricle, a process known as left ventricular (LV) remodeling3. These changes are commonly assessed using echocardiography, with measurements of left ventricular mass index (LVMI) and relative wall thickness (RWT), which classify LV geometry into normal geometry, concentric remodeling (CR), concentric hypertrophy (CH), or eccentric hypertrophy (EH)4. LV remodeling is strongly linked to increased morbidity and mortality in a variety of cardiovascular diseases, including atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure5,6. In addition, LV remodeling has been shown to have widespread effects on the coronary arteries due to their anatomical proximity, including impaired coronary flow reserve, exacerbated coronary remodeling, and the development of hemodynamic abnormalities7,8.

Coronary chronic total occlusion (CTO) is a severe lesion of CAD, defined as a complete occlusion of the coronary artery lasting more than three months9. The incidence of CTO among patients undergoing coronary angiography typically ranges from 10 to 20%10. Patients with CTO lesions often experience inadequate myocardial perfusion, leading to ischemic symptoms and an increased risk of heart failure11. Despite advances in cardiac interventions, CTO remains a significant challenge due to the complexity of the lesions12,13. Severe CTO lesions may even require coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), greatly increasing the treatment risks14. The coronary arteries are anatomically adjacent to the myocardium. Therefore, the pathological features of LV remodeling, such as cardiac inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and myocardial fibrosis, may affect the coronary arteries, thus increasing the risk of CTO15,16. We hypothesize that hypertensive LV remodeling may increase the risk of CTO lesions.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the association between LV remodeling and coronary CTO in hypertensive CAD patients, providing valuable insights into the role of cardiac structural changes in the progression of severe coronary lesions.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 3,430 patients with CAD and hypertension were included in the study, among whom 300 (8.7%) were diagnosed with CTO. The mean age of the study population was 65.3 ± 10.8 years, and 68.9% were male (Table 1). LV remodeling was more prevalent in patients with CTO (79.7% vs. 69.9%, p < 0.001). Patients with CTO were more likely to be male (80.0% vs. 67.8%, p < 0.001), had higher BMI (25.2 ± 3.8 vs. 24.6 ± 3.3 kg/m2, p = 0.004), and lower LVEF (61.5 ± 11.0% vs. 65.5 ± 9.2%, p < 0.001). They also had a slightly higher rate of blood pressure control (56.7% vs. 50.5%, p = 0.049), while the distribution of hypertension duration was comparable between groups.

Distribution of LV geometric patterns

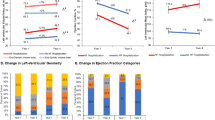

The density plot (Fig. 1) demonstrates the distribution of patients across different LV geometric patterns: 1,003 with normal geometry, 709 with CR, 1,011 with CH, and 707 with EH, corresponding to CTO incidence rates of 6.1%, 6.9%, 9.9%, and 12.7%, respectively. The restricted cubic spline analysis indicated a higher likelihood of CTO among patients with higher LVMI, with a significant rise in risk when LVMI exceeds approximately 100 g/m2 (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the risk of CTO increases with lower RWT, particularly when RWT falls below approximately 0.4 (Fig. 2B).

Population Distribution and CTO Incidence Based on Left Ventricular Mass Index and Relative Wall Thickness in Hypertensive CAD Patients. The density plot depicts the distribution of the population based on left ventricular mass index (LVMI) and relative wall thickness (RWT), with density levels indicated by a color gradient from low (blue) to high (red). Left ventricular geometry is categorized into four patterns: normal, concentric remodeling (CR), concentric hypertrophy (CH), and eccentric hypertrophy (EH), based on LVMI (95 g/m2 for females, 115 g/m2 for males) and RWT (0.42). The corresponding incidence of chronic total occlusion (CTO) for each pattern is indicated on the plot.

Dose–Response Association of Left Ventricular Mass Index and Relative Wall Thickness with the Risk of CTO. Restricted cubic spline models demonstrate the dose–response association between left ventricular mass index (LVMI) (A) and relative wall thickness (RWT) (B) with the risk of chronic total occlusion (CTO). After excluding patients with LVMI or RWT values beyond the 1st and 99th percentiles, spline analyses were conducted with four knots placed at specific distribution percentiles (5%, 35%, 65%, and 95%). The spline model was adjusted for age, gender, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, type 2 diabetes, controlled hypertension, LDL-C, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and medications. Odds ratios (OR) for CTO are shown with 95% confidence intervals (CI). In panel (A), the risk of CTO increases with higher LVMI, particularly when LVMI exceeds approximately 100 g/m2. In panel (B), a decrease in RWT is associated with an increased risk of CTO, especially when RWT falls below approximately 0.4.

Association between LV remodeling and CTO risk

In comparison to normal geometry, LV remodeling was statistically associated with higher odds of CTO (OR, 1.696; 95% CI 1.258–2.285; p = 0.001) (Table 2). Among specific LV geometric patterns, CH (OR, 1.798; 95% CI 1.276–2.535; p = 0.001) and EH (OR, 2.355; 95% CI 1.656–3.349; p < 0.001) were associated with greater odds of CTO, whereas CR was not (Table 2). The association between LV remodeling and CTO remained consistent across subgroups stratified by age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65 years), gender (male vs. female), BMI (< 24 vs. ≥ 24 kg/m2), type 2 diabetes (absent vs. present), hypertension status (controlled vs. uncontrolled), hypertension duration (< 5 vs. ≥ 5 years), LDL-C (< 1.8 vs. ≥ 1.8 mmol/L), and clinical presentation (ACS vs. non-ACS), with no significant interactions observed (all P values for interaction ≥ 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Subgroup Analysis of Left Ventricular Remodeling and CTO in Hypertensive CAD Patients. Subgroup analysis of the association between left ventricular remodeling and CTO in hypertensive CAD patients. The odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented for different subgroups, including age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65 years), gender (male vs. female), BMI (< 24 vs. ≥ 24 kg/m2), type 2 diabetes (no vs. yes), current hypertension status (controlled vs. uncontrolled), hypertension duration (< 5 vs. ≥ 5 years), LDL-C (< 1.8 vs. ≥ 1.8 mmol/L), and clinical presentation (ACS vs. non-ACS). The P values for interaction are provided to assess the heterogeneity of the associations across subgroups.

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the findings. First, after excluding patients with LVMI or RWT values outside the 5th and 95th percentiles (77 patients in total), results remained consistent (Table S1). Second, SBP was positively associated with LV remodeling (OR, 1.005; 95%CI, 1.001–1.009; p = 0.025) (Table S2), but not with CTO (Table S3). Third, after further adjusting for cardiac functional indicators, including volume load (NT-proBNP), pressure load (SBP and DBP), systolic function (LVEF), and diastolic filling pattern, the observed associations persisted (Table S4). Fourth, no significant association was observed between LV remodeling and CTO across specific coronary branches (Table S5). Fifth, after further adjusting for indicators of chronic disease burden—including multivessel disease, left main coronary artery disease, and categorized hypertension duration (< 5, 5–9, ≥ 10 years)—the association remained robust (Table S6). Finally, in a restricted analysis of patients with low disease burden (no multivessel and left main disease, controlled blood pressure, and hypertension duration < 10 years), associations persisted and appeared stronger (Table S7), further supporting the consistency of the observed pattern.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional, hypothesis-generating study of 3,430 hypertensive CAD patients, LV remodeling was observed in approximately 70.8% of the patients and was statistically associated with an increased likelihood of CTO, particularly in those with CH and EH. This association remained robust after adjusting for multiple cardiac functional parameters, including systolic and diastolic function, pressure load, and volume status. While causality cannot be inferred, these findings support the hypothesis that LV remodeling may represent a structural marker—or potential contributor—to increased CTO risk in this population.

Hypertension is the most common cause of chronic pressure overload on the heart, leading to adaptive LV remodeling in response17. Epidemiological evidence has shown that LV remodeling is associated with an increased risk of coronary events in hypertensive patients. In essential hypertension, Koren et al.18 identified an independent association between LV remodeling and the risk of coronary events, primarily myocardial infarction. They rereported the 10-year cardiac mortality rates were 1%, 6%, 10%, and 24% in individuals with normal geometry, CR, EH, and CH, respectively18. In elderly hypertensive patients, Aronow et al.19 found that LV hypertrophy was an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events during a median follow-up of 40 months. In patients with a first myocardial infarction and normal LV function, Carluccio et al.20 found LV remodeling can be a good predictor of subsequent unstable angina and non-fatal reinfarction. In agreement with these studies, our findings confirm that LV remodeling is associated with a higher risk of CTO in CAD patients with hypertension.

Several potential pathogenic mechanisms may explain the relationship between LV remodeling and increased risk of CTO. First, biological mediators associated with LV remodeling significantly contribute to the formation of CTO. When the heart undergoes chronic pressure overload, there is an increase in the secretion of cardiac neurohormones such as angiotensin II, aldosterone, endothelin, and bradykinin, which regulate hemodynamics and further promote LV remodeling21,22,23. Additionally, cytokines, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor 1, which are known to regulate myocardial growth and composition, play an essential role in the progression of LV remodeling by facilitating structural changes in the heart tissue24,25. These mediators also trigger vascular inflammation, which stimulates collagen synthesis in the vessel wall and promotes compensatory angiogenesis, thereby accelerating the development of atherosclerotic lesions that eventually lead to CTO formation26,27,28. Second, LV remodeling may contribute to the development of CTO through coronary endothelial dysfunction. The process of LV remodeling significantly increases myocardial oxygen demand due to the rise in LV mass and wall stress29. In patients with CH and EH, the oxygen demand is twice and three times that of a normal heart, respectively29. When the coronary arteries are unable to meet this increased demand, chronic oxygen insufficiency leads to endothelial dysfunction, which in turn promotes coronary artery remodeling, accelerates atherosclerosis, and ultimately contributes to the development of CTO30,31,32.

There are some findings in the current study that are worth noting. First, CH and EH represent more severe LV geometric patterns compared to CR. LV remodeling consists of three geometric patterns: CR, CH, and EH. Unlike CH and EH, the current study did not identify a significant association between CR and CTO, which may be due to CR being an early adaptive response to hypertension33. A similar finding was reported by Jalal et al.34, who found that EH and CH, but not CR, were associated with higher mortality during an average 9-year follow-up in patients with suspected CAD. The authors suggested that the relatively poor predictive ability of the RWT, compared to LVMI, may explain this finding34. In agreement, our spline plots (Fig. 2) demonstrate that LVMI has a stronger association with CTO risk than RWT. Second, cardiac structure may serve as an independent factor contributing to the increased risk of CTO, independent of cardiac function itself. This is supported by our adjustments for volume load, pressure load, diastolic function, and systolic function in the present study.

In this hypothesis-generating study, we carefully considered whether the observed association between LV remodeling and CTO reflects a direct relationship or is instead a shared consequence of the cardiovascular disease chronicity. To test this possibility, we conducted several additional analyses. First, we included measures of disease chronicity (hypertension duration) and severity (controlled hypertension status, multivessel disease, and left main coronary artery involvement) in fully adjusted models. The association between LV remodeling and CTO remained significant after adjustment (Table S6), suggesting that this relationship was not entirely explained by baseline disease burden. Second, in a restricted analysis of patients with low disease burden—defined as absence of multivessel and left main disease, hypertension duration < 10 years, and well-controlled blood pressure—the association became even stronger (Table S7), further supporting its potential independence. Third, we found that systolic blood pressure was positively associated with LV remodeling (Table S2), but not with CTO risk (Table S3), implying that pressure overload may drive myocardial structural changes without directly contributing to occlusive coronary lesions. Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that LV remodeling may be independently associated with CTO risk, beyond what can be explained by the chronicity burden of cardiovascular disease. Further studies are warranted to validate this association and investigate the underlying mechanisms.

Although this study is exploratory, the observed association may have important clinical implications. Since LV geometry can be readily assessed through routine echocardiography, identifying hypertensive CAD patients with concentric or eccentric hypertrophy may help flag individuals at higher risk of silent or advanced coronary lesions. This could prompt more vigilant clinical surveillance, including consideration of ischemia testing or early coronary imaging in selected cases. Furthermore, recognizing high-risk geometric phenotypes may refine risk stratification and support more personalized preventive or diagnostic strategies in this population.

This study still has several limitations. First, although hypertension duration was included as a categorical variable to reflect disease chronicity, its accuracy may be limited by reliance on patient-reported or chart-recorded history. Second, the study is limited to hypertensive patients, and the findings may not be generalizable to broader populations. Third, the assessment of left ventricular remodeling in this study was based on echocardiographic measurements, which may be subject to inter-operator variability. Fourth, the absence of septal e′ velocity limited accurate assessment of diastolic filling, although surrogate classification using E/A ratio and left atrial diameter was applied. Finally, as an observational study, this analysis cannot establish causality, and the associations observed may be subject to residual confounding. Accordingly, these findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating and warrant validation in prospective mechanistic studies.

In this hypothesis-generating study, LV remodeling was associated with an increased risk of CTO in hypertensive patients with CAD, particularly among those with concentric or eccentric hypertrophy. These findings suggest a possible link between myocardial structural changes and advanced coronary lesions. Further prospective studies are warranted to confirm this association and explore underlying mechanisms.

Methods

Study population

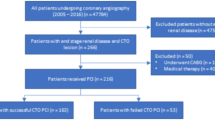

This cross-sectional study used data from the Department of Cardiology at Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Patients underwent diagnostic coronary angiography and newly diagnosed with CAD were screened. The collected data included demographic characteristics, medical history, treatment procedures, and clinical outcomes. The study included patients who met both of the following criteria: (1) diagnosed with CAD according to current guidelines through coronary angiography35, and (2) diagnosed with hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, a documented history of hypertension, or the use of antihypertensive medication36. Exclusion criteria included: (1) absence of preoperative echocardiography or incomplete echocardiographic data; (2) presence of secondary hypertension; (3) history of myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting; (4) severe cardiopulmonary diseases, including pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary heart disease, or valvular heart disease; (5) severe comorbidities, including end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, hyperthyroidism, severe anemia, or terminal malignancy. Ultimately, 3,430 hypertensive CAD patients were enrolled (Figure S1). This retrospective observational study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital (Ethics ID: 20,201,217–36) and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective design and the use of de-identified data, the ethics committee granted a waiver of individual informed consent.

Left ventricular remodeling

LV structural parameters were assessed using two-dimensional guided M-mode echocardiography, performed by experienced sonographers, in accordance with the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) guidelines37. To minimize measurement bias, all echocardiographic examinations were conducted prior to coronary angiography, and the sonographers were blinded to the angiographic findings, including the presence or location of CTO lesions. The following measurements were taken: left ventricular internal diastolic diameter (LVIDd), posterior wall diastolic thickness (PWd), and interventricular septal end-diastolic thickness (IVSd). RWT was calculated as (IVSd + LVPWd)/LVIDd33, while LVMI was derived using the formula LVMI (g/m2) = LVM/BSA, where left ventricular mass (LVM) was determined as 0.8 × 1.04 × [(LVIDd + IVSd + PWd)3—LVIDd3] + 0.638, and body surface area (BSA) was calculated as 0.61 × height (m) + 0.0128 × body weight (kg)—0.152933.

According to the ASE/European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) guidelines, LV geometry was classified using cut-off values of 0.42 for RWT, 95 g/m2 for LVMI in females, and 115 g/m2 for LVMI in males33. LV geometry was then categorized into four patterns: normal geometry, defined as low LVMI with low RWT; CR, defined as low LVMI with high RWT; CH, defined as high LVMI with high RWT; and EH, defined as high LVMI with low RWT. LV remodeling was defined as the presence of any of the CR, CH, or EH patterns.

Coronary chronic total occlusion

Coronary CTO was defined as a complete and persistent occlusion of a coronary artery for more than three months, with no antegrade or collateral flow to the distal vessel9. Coronary CTO was diagnosed using coronary angiography, the gold standard for identifying CTO lesions. Diagnostic coronary angiography was performed by experienced interventional cardiologists in accordance with the most current international guidelines39. The lesion characteristics, including its location, length, and complexity, were recorded to assess its severity and determine the appropriate management strategy. The location of CTO lesions was classified according to the affected coronary artery, including the left anterior descending artery, left circumflex artery, or right coronary artery.

Covariates

Smoking status was categorized into never (never smoked), former (smoked previously but had quit for at least 6 months), and current (smoked within the past 6 months). Alcohol consumption was classified as never (never drank alcohol), former (ceased alcohol consumption for at least 6 months), and current (drank alcohol within the past 6 months). Type 2 diabetes was defined by a medical history of the disease, use of anti-diabetic medications, or blood glucose levels meeting the American Diabetes Association criteria40. Clinical presentation was classified as acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or non-ACS, according to the fourth universal definition of acute myocardial infarction41. Controlled hypertension is defined as a patient with hypertension whose blood pressure is maintained at a level of less than 140/90 mmHg based on repeated measurements over a period of time42. Hypertension duration was determined based on patient-reported diagnosis history, supplemented by longitudinal antihypertensive prescription records when available, and categorized as < 5 years, 5–9 years, or ≥ 10 years. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured by echocardiography using the Simpson’s method, reflecting cardiac systolic function. The E/A ratio was calculated as the ratio of peak early diastolic flow velocity (E velocity) to the peak velocity of atrial contraction (A velocity), with an E/A ratio < 1 indicating diastolic dysfunction43. Left main (LM) disease was defined as ≥ 50% diameter stenosis in the left main coronary artery, as determined by coronary angiography. Multivessel disease (MVD) was defined as the presence of ≥ 50% diameter stenosis in at least two of the three major epicardial coronary arteries—the left anterior descending, left circumflex, and right coronary artery—regardless of whether CTO was present.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were summarized based on the presence or absence of CTO lesions. Normally distributed continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and compared using the independent samples t-test. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were presented as median [interquartile range] and compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables were presented as counts (percentages) and compared using the chi-square test.

The distribution of the population and the CTO incidence were visualized by a density plot based on the echocardiography-derived metrics of LVMI and RWT. Restricted cubic spline models were employed to assess the dose–response association between continuous LVMI and RWT with the incidence of CTO. Four knots were placed at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles of the distribution. Multivariable logistic regression models were fitted to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between LV remodeling and CTO. Model 1 adjusted for age (continuous), gender (male or female), and body mass index (BMI, continuous); Model 2 further adjusted for smoking status (none, quit, or current), alcohol consumption (none, quit, or current), type 2 diabetes (no or yes), controlled hypertension (no or yes), LDL-C (continuous), and ACS (no or yes); Model 3 additionally adjusted for medications, including angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), calcium channel blockers (CCB), thiazide diuretics, metoprolol, and angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI). Subgroup analysis was performed by stratifying patients based on age (< 65, ≥ 65 years), gender (male, female), BMI (< 24, ≥ 24 kg/m2), type 2 diabetes (no, yes), hypertension status (controlled, uncontrolled), hypertension duration (< 5, ≥ 5 years), LDL-C (< 1.8, ≥ 1.8 mmol/L), and symptom (non-ACS, ACS). Interactions between LV remodeling and stratified factors were evaluated by including the interaction term in the model.

To test the robustness of our findings, several sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, considering potential outliers in LVMI and RWT, we excluded patients with LVMI or RWT values outside the 5th and 95th percentiles and refitted the model. Second, to assess whether these associations were independent of cardiac function, we further adjusted for cardiac volume load (NT-proBNP), pressure load (SBP and DBP), systolic function (LVEF), and diastolic filling pattern. Diastolic pattern was classified into three categories based on mitral inflow velocity (E/A ratio) and left atrial diameter (LAD): impaired relaxation (E/A < 1), normal filling (E/A ≥ 1 with LAD < 40 mm), and pseudonormal pattern (E/A ≥ 1 with LAD ≥ 40 mm). Third, we explored the relationships between these cardiac functional indicators, LV remodeling, and CTO to better understand their potential roles. Fourth, the association between LV remodeling and CTO risk across specific coronary artery branches was examined to determine if lesion location affected the results. Fifth, to address confounding by disease severity, we adjusted for multivessel disease, left main coronary artery involvement, and hypertension duration categorized as < 5, 5–9, or ≥ 10 years. Finally, we repeated the analysis in a clinically lower-risk subgroup—patients without multivessel or left main disease, with hypertension duration < 10 years and well-controlled blood pressure—to examine whether the associations persisted in a population with milder cardiovascular burden.

Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistical significance. Data were analyzed by R software (R version 4.1.1).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CTO:

-

Coronary chronic total occlusion

- LV:

-

Left ventricular

- LVMI:

-

Left ventricular mass index

- RWT:

-

Relative wall thickness

- CH:

-

Concentric hypertrophy

- EH:

-

Eccentric hypertrophy

- CR:

-

Concentric remodeling

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- NT-proBNP:

-

N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide

- ACEI:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- ARB:

-

Angiotensin receptor blockers

- CCB:

-

Calcium channel blockers

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

References

Vaduganathan, M., Mensah, G. A., Turco, J. V., Fuster, V. & Roth, G. A. The global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk: A compass for future health. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80, 2361–2371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.005 (2022).

Lawes, C. M., Vander Hoorn, S. & Rodgers, A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet 371, 1513–1518. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8 (2008).

Tadic, M., Cuspidi, C. & Marwick, T. H. Phenotyping the hypertensive heart. Eur. Heart J. 43, 3794–3810. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac393 (2022).

Marwick, T. H. et al. Recommendations on the use of echocardiography in adult hypertension: A report from the European association of cardiovascular imaging (EACVI) and the American society of echocardiography (ASE)dagger. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 16, 577–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jev076 (2015).

Stewart, M. H. et al. Prognostic implications of left ventricular hypertrophy. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 61, 446–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2018.11.002 (2018).

Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Meng, Y., Wang, Q. & Guo, Y. Correlation between the hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) score and left ventricular hypertrophy in older patients with hypertension. Cardiovasc. Innov. App. 8, 946. https://doi.org/10.15212/cvia.2023.0068 (2023).

Hamasaki, S. et al. Attenuated coronary flow reserve and vascular remodeling in patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 35, 1654–1660. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00594-5 (2000).

de Simone, G. & Palmieri, V. Left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension as a predictor of coronary events: Relation to geometry. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens 11, 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1097/00041552-200203000-00013 (2002).

Stone, G. W. et al. Percutaneous recanalization of chronically occluded coronary arteries: A consensus document: Part I. Circulation 112, 2364–2372. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.481283 (2005).

Fefer, P. et al. Current perspectives on coronary chronic total occlusions: The Canadian multicenter chronic total occlusions registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 59, 991–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.007 (2012).

Chi, W. K. et al. Impact of coronary artery chronic total occlusion on arrhythmic and mortality outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 4, 1214–1223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2018.06.011 (2018).

Assali, M. et al. Update on chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 69, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2021.11.004 (2021).

Gogineni, V. S. & Shah, K. B. High-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: Challenges and considerations. Cardiovasc. Innov. App. 9, 949. https://doi.org/10.15212/cvia.2024.0029 (2024).

Werner, G. S. et al. A randomized multicentre trial to compare revascularization with optimal medical therapy for the treatment of chronic total coronary occlusions. Eur. Heart J. 39, 2484–2493. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy220 (2018).

Burchfield, J. S., Xie, M. & Hill, J. A. Pathological ventricular remodeling: mechanisms: Part 1 of 2. Circulation 128, 388–400. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001878 (2013).

Fraccarollo, D. et al. Improvement in left ventricular remodeling by the endothelial nitric oxide synthase enhancer AVE9488 after experimental myocardial infarction. Circulation 118, 818–827. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717702 (2008).

Messerli, F. H., Rimoldi, S. F. & Bangalore, S. The transition from hypertension to heart failure: Contemporary update. JACC Heart Fail 5, 543–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2017.04.012 (2017).

Koren, M. J., Devereux, R. B., Casale, P. N., Savage, D. D. & Laragh, J. H. Relation of left ventricular mass and geometry to morbidity and mortality in uncomplicated essential hypertension. Ann. Intern. Med. 114, 345–352. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-114-5-345 (1991).

Aronow, W. S., Ahn, C., Kronzon, I. & Koenigsberg, M. Congestive heart failure, coronary events and atherothrombotic brain infarction in elderly blacks and whites with systemic hypertension and with and without echocardiographic and electrocardiographic evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am. J. Cardiol. 67, 295–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(91)90562-y (1991).

Carluccio, E. et al. Prognostic value of left ventricular hypertrophy and geometry in patients with a first, uncomplicated myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 74, 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-5273(00)00264-3 (2000).

Frohlich, E. D. Overview of hemodynamic and non-hemodynamic factors associated with left ventricular hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 21(Suppl 5), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2828(89)90767-0 (1989).

Weber, K. T., Sun, Y. & Guarda, E. Structural remodeling in hypertensive heart disease and the role of hormones. Hypertension 23, 869–877. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.869 (1994).

Duan, X. & Yu, Z. HNP-1 reverses hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway. Cardiovasc. Innov. App. 8, 957. https://doi.org/10.15212/cvia.2023.0057 (2023).

Tanaka, N. et al. Effects of growth hormone and IGF-I on cardiac hypertrophy and gene expression in mice. Am. J. Physiol. 275, H393-399. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H393 (1998).

Ruwhof, C. & van der Laarse, A. Mechanical stress-induced cardiac hypertrophy: Mechanisms and signal transduction pathways. Cardiovasc. Res. 47, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00076-6 (2000).

Cheng, Z. J., Vapaatalo, H. & Mervaala, E. Angiotensin II and vascular inflammation. Med. Sci. Monit. 11, RA194-205 (2005).

Rizvi, M. A., Katwa, L., Spadone, D. P. & Myers, P. R. The effects of endothelin-1 on collagen type I and type III synthesis in cultured porcine coronary artery vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 28, 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmcc.1996.0023 (1996).

de Lima, M. C. F., Dos SantosReis, M. D., da Silva Ramos, F. W., Ayres-Martins, S. & Smaniotto, S. Growth hormone modulates in vitro endothelial cell migration and formation of capillary-like structures. Cell Biol. Int. 41, 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbin.10747 (2017).

Devereux, R. B. et al. Left ventricular wall stress-mass-heart rate product and cardiovascular events in treated hypertensive patients: LIFE study. Hypertension 66, 945–953. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05582 (2015).

Palombo, C. et al. Early impairment of coronary flow reserve and increase in minimum coronary resistance in borderline hypertensive patients. J. Hypertens 18, 453–459. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-200018040-00015 (2000).

Lerman, A., Cannan, C. R., Higano, S. H., Nishimura, R. A. & Holmes, D. R. Jr. Coronary vascular remodeling in association with endothelial dysfunction. Am. J. Cardiol. 81, 1105–1109. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00135-0 (1998).

Hays, A. G. et al. Regional coronary endothelial function is closely related to local early coronary atherosclerosis in patients with mild coronary artery disease: Pilot study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 5, 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.969691 (2012).

Yildiz, M. et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy and hypertension. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 63, 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2019.11.009 (2020).

Ghali, J. K., Liao, Y. & Cooper, R. S. Influence of left ventricular geometric patterns on prognosis in patients with or without coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 31, 1635–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00131-4 (1998).

Bangalore, S. et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 79, 21–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006 (2022).

Stergiou, G. S. et al. 2021 European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for office and out-of-office blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens 39, 1293–1302. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000002843 (2021).

Schiller, N. B. et al. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American society of echocardiography committee on standards, subcommittee on quantitation of two-dimensional echocardiograms. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2, 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8 (1989).

Devereux, R. B. et al. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: Comparison to necropsy findings. Am. J. Cardiol. 57, 450–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x (1986).

Levine, G. N. et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: An update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 1235–1250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.005 (2016).

American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 43, S14–S31. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-S002 (2020).

Thygesen, K. et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 2231–2264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038 (2018).

Whelton, P. K. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive summary: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension 71, 1269–1324. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066 (2018).

Yuan, L. et al. Reversal E/A value at end-inspiration might be more sensitive and accurate for diagnosing abnormal left ventricular diastolic function. Echocardiography 24, 472–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00433.x (2007).

Funding

This study was supported by Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (grant number: 2023ZD0503900, 2023ZD0503904) and 13th Session of the Hangzhou Biopharmaceutical and Health Industry Development Support Technology Program (grant number: 2024WJC026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wujian He: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original draft. Qiang Yao: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – Review & editing. Duanbin Li: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – Review & editing, Funding acquisition. Xiangqian Sui: Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – Original draft. Wenbin Zhang: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – Review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, W., Yao, Q., Li, D. et al. Association between left ventricular remodeling and coronary chronic total occlusion in hypertensive coronary artery disease patients. Sci Rep 15, 24239 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09054-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09054-3