Abstract

Physical exercise is an effective intervention in controlling gestational plasma glucose (PG) and reducing adverse pregnancy outcomes. However, evidence regarding the appropriate levels of physical exercise for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) women is still limited, especially in China. This study aims to explore the association between physical exercise time and the abnormal plasma glucose (APG) during third trimester, and to develop physical exercise instruction for GDM women with different characteristics. In this study, GDM was diagnosed by 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). During the routine antenatal checkups subsequent to GDM confirmation, APG was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.10 mmol/L, or 2-h plasma glucose ≥ 8.5 mmol/L with breakfast consumption. Information regarding prenatal examination and birth records among GDM women was extracted from the health information system, and physical exercise data was collected through face-to-face interviews. Group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) was implemented through R software to identify distinct trajectories of APG percentage, and the restricted cubic spline (RCS) curves with four knots were used to model the dose–response relationship between physical exercise time and the APG percentage among GDM women, in the total and different subgroups. In this study, a P-value less than 0.05 (two-tailed) was viewed as statistical significance. The age of 1448 GDM women ranged from 18 to 45 years, with an average age of 31.22 years. GDM women was divided into low APG group (n = 974, 67.27%) and high APG group (n = 474, 32.73%) based on the GBTM. Logistic regression indicated that GDM women with advanced maternal age (odds ratio (OR) = 2.37 and 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.44–3.90 for those aged 36–45 years, and OR = 1.62 (95% CI 1.02–2.56) for those aged 31–35 years), overweight and obese (OR = 1.70, 95%CI 1.34–2.16) had higher APG risk. The RCS curve indicated that physical exercise could lower the APG percentage among GDM women. However, GDM women with advanced maternal age, overweight and obese still had high APG percentage even when physical exercise exceeded 90 min/day. Physical exercise over 60 min/day could effectively lower the APG risk among GDM women, but even over 90 min/day is less efficient for those with advanced maternal age, overweight and obese, so physical exercise incorporated with other intervention measures should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is one of the most common metabolic disorders in pregnancy, which refers to the first occurrence of impaired glucose tolerance of varying degrees during gestation1. GDM seriously impacts both maternal and neonatal health, which not only lead to immediate complications, but also lead to long-term adverse pregnancy outcomes2. Studies indicate that high glucose environment in the uterus of GDM women can affect the development of placental morphology and function, and induce the hazard of fetal chronic diseases 2–8 times higher than normal levels3,4. The rapidly growing epidemiological trend of GDM and rising healthcare expenditures have seriously affected the quality of the neonatal population5,6.

In UK, over 90% of GDM women can achieve well treatment effect by physical exercise and nutrition interventions7. Physical exercise is an effective intervention measure in promoting fat decomposition and reducing insulin resistance, which can improve gestational plasma glucose and reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes8,9,10. In addition, physical exercise can also help GDM women adjust their emotions, relieve depression and anxiety, improve physical health and maintain a healthy lifestyle11. While the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommend that pregnant women engage in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical exercise weekly, but did not put forward a specific guide for GDM women12,13. Meanwhile, previous research found that the abnormal plasma glucose (APG) percentage among some GDM women was still high even with long physical exercise time14. Therefore, evidence regarding the appropriate levels of physical exercise for GDM women with different types is limited, especially in China.

Group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) has been increasingly applied for its usefulness in describing dynamic change and identifying unobserved heterogeneity in trajectories among the population15. GBTM is beneficial in trajectory simulation and identification which prevent the dissemble the differences between groups16. Previous studies explore the association between physical exercise and poor glycemic control are mainly based on the individual APG percentages, but without considering the dynamic changes of APG percentage among GDM women, which prevent the accurate understanding of the dynamic trajectory of APC changes among GDM women with good glycemic control. However, we can accurately delineate the characteristics of GDM women with good APG control grouped based on GBTM, and to explore the associated influencing factors.

In this study, we aim to explore the association between physical exercise and the APG percentage among GDM women based on GBTM and RCS curve, and to develop physical exercise instruction for GDM women.

Methods

Study population

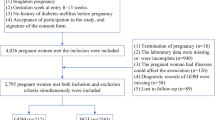

This is a prospective study conducted in Shanghai, China from 2020 to 2024. We established a prospective cohort with over 1000 GDM women to explore the influence of physical exercise on plasma glucose during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Participants were recruited from the Songjiang Maternal and Children’s Healthcare Hospital (SMCHH) at their 24–28 weeks of gestation, and followed until the delivery. The sample size calculation has been described in detail in our previously published work17. In this study, the inclusion criteria were: (1) aged 18–45 years; (2) lived in Songjiang District without any migration plan in the next two years; (3) gestation of 24–28 weeks, confirmed GDM diagnosis with 75 g OGTT; (4) singleton pregnancy; (5) without preexisting diabetes history; (6) being able to read and sign the informed consent form9,17,18. GDM women with pharmacological interventions for glycemic control, with physical exercise restrictions and psychological disorders during pregnancy were excluded. Finally, 1448 GDM woman were enrolled in the study. The review board of SMCHH reviewed and approved this study (IRB 2019-12-003), and the written informed consent were obtained from all participants prior to data collection. This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000028832), Fig. 114.

Data collection

This study employed a structured questionnaire to collect data from GDM women. The questionnaire had four parts, Part A encompassed demographic characteristics, including age, education, occupation, and residency status. Part B encompassed detailed information regarding obstetric history, diabetes history, pre-pregnancy height and body weight, and routine antenatal check records. Part C encompassed perinatal outcomes, including gestational age at delivery, delivery mode, and any adverse outcomes. Part D recorded the frequency and duration of physical exercise during the late gestational period (27–40 weeks).

Data in Part A, B, and C was directly extracted from the electronic health records and antenatal care records maintained by the hospital. Data in Part D was collected through face-to-face interviews conducted in the wards by trained nurses after the delivery of GDM women and verified by a random selection of 15% of all GDM women. To ensure data integrity, records with incomplete or missing values were systematically flagged and cross-verified against the original paper-based medical records. All collected data were anonymized to ensure participants’ privacy and prevent any potential linkage to individual identities.

Definition and index calculation

In this study, the diagnosis of GDM was in line with the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG). Women without prior diabetes underwent a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) at 24–28 weeks of gestation. GDM was diagnosed if any of the following plasma glucose thresholds were met: (1) fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.1 mmol/L, (2) 1-h plasma glucose ≥ 10.0 mmol/L, or (3) 2-h plasma glucose ≥ 8.5 mmol/L19. During the routine antenatal checkups subsequent to GDM confirmation, APG was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.10 mmol/L, or 2-h plasma glucose ≥ 8.5 mmol/L with breakfast consumption. The percentage of abnormal blood glucose was determined through dividing the number of abnormal plasma glucose tests by the total number of plasma glucose tests conducted in each GDM women.

Pre-pregnancy BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by 2 times of height (m), and categorized as < 18.5 kg/m2 (underweight), 18.5–24 kg/m2 (normal weight), and > 24 kg/m2 (overweight/obese). The age of GDM women was divided into 18–25 years, 26–30 years, 31–35 years, and 36–45 years (defined as advanced maternal age). Education was quantified based on the total years of formal education completed and divided into 6–9 years (primary/junior high), 10–12 years (senior high), and > 12 years (college and above). The level of physical exercise was assessed through the self-reported total physical exercise times, and was classified into " < 30 min/day", "30–59 min/day", "60–89 min/day", "90–119 min/day", and " ≥ 120 min/day".

Statistical analysis

This study utilized SAS (version 9.4) and R software (version 4.4.2) for data analysis. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were employed to describe normally distributed quantitative data, and median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to describe skewed distributed quantitative data. Student’s t test and Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare the difference of quantitative data between groups as appropriate. Qualitative data was expressed as frequency and percentage (%) and Chi-square test was employed to compared differences between groups. In this study, GBTM was implemented through R to identify distinct trajectories of the APG percentage among GDM women. Firstly, trajectories with one, two and three groups was fitted based on the GBTM, respectively (Table 2), and then the selected two group GBTM was fitted with different random effects and functions (Table 3). The best fitted model was determined based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Logistic regression model was applied to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) to explore factors associated with the high APG percentage divided based on the GBTM among GDM women. Restricted cubic spline curves with four knots were used to model the dose–response relationship between daily physical exercise time and APG percentages among GDM women with different trajectories group categorized by the GBTM and with different demographic features as well. In this study, a P-value less than 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered as statistically significant.

Results

In this study, the average age of 1448 GDM women was 31.22 years (SD = 4.59 years), with 677 primipara (46.75%) and 771 multipara (53.25%). The percentage of GDM women in age group of 18–25 years, 26–30 years, 31–35 years, and 36–45 years was 10.01%, 35.98%, 35.57%, and 18.44%, respectively. The majority of GDM women had an education of college and above (61.40%), and 42.40% of them had a balanced diet with doctors’ suggestion. The median value of BMI among GDM women was 22.77 kg/m2 (IQR: 20.67–25.15), and 4.63%, 59.25%, and 36.12% were underweight, normal weight, and overweight/obese, respectively. The median value of daily physical exercise time was 55.00 min (IQR: 35.00–75.00), and the percentage of GDM women with daily physical exercise time < 30 min, (30–59) min, (60–89) min, (90–119) min, and ≥ 120 min was 14.64%, 38.33%, 32.80%, 10.64%, and 3.59%, respectively. The median weight gain during gestation was 8.60 kg (IQR: 5.00–11.60), and approximately 25% GDM women had adverse pregnancy outcomes, including premature rupture of membranes (206, 14.23%), macrosomia (89, 6.15%), premature infants (77, 5.32%), low birth weight (55, 3.80%), postpartum hemorrhage (36, 2.49%), polyhydramnios (23, 1.59%), puerperal infection (5 cases), neonatal asphyxia (3 cases) and 1 case of forceps delivery. Moreover, the median percentage of APG was 37.50% (IQR: 20.00–62.50%) among 1448 GDM women (Table 1).

Trajectories of the abnormal plasma glucose percentage

In this study, a sequence of trajectory models varying from 1 to 3 classes were established, and then compared to determine the best-fitted model. The best fitted model would be used to characterize the heterogeneity in dynamic change of the APG percentage among GDM women (Table 2). Tables 2 and 3 indicated that model with 2 distinct trajectories had the lowest AIC and BIC value, which was then selected as the best fitted APG percentage trajectories (with random intercept and linear) (Table 3). To facilitate the interpretability, we assigned labels to present the different trajectories of the APG percentage based on the modeled graphical patterns (Fig. 2), and then divided GDM women into Class 1 (with low APG group, n = 974, accounting for 67.27%) and Class 2 (with high APG group, n = 474, accounting for 32.73%).

Characteristics of GDM women within different trajectories based on GBTM

The average age of GDM women in the low and high APG group was 30.77 years (SD = 4.41) and 32.14 years (SD = 4.83), respectively. The median BMI value among GDM women was 22.41 kg/m2 (IQR: 20.47–24.61) in the low APG group, and 23.70 kg/m2 (IQR: 21.40–25.71) in the high APG group. The median physical exercise time was 57.83 min/day (IQR: 38.00–75.00) and 50.00 min/day (IQR: 30.00–75.00) among GDM women with low APG and high APG, respectively. The median weight gain during gestation among GDM women was 9.05 kg (IQR: 5.80–12.00) in the low APG group and 7.50 kg (IQR: 3.60–10.60) in the high APG group. In this study, GDM women in the high APG group had higher proportion of advanced maternal age,and higher proportion of overweight and obese than those in the low APG group, the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Table 4).

GDM women with different pregnancy outcomes status

In this study, 26.17% of GDM women had adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO). The average age was 31.38 years (SD = 4.63) for GDM women without APO, and 30.77 years (SD = 4.46) for GDM women with APO. The median BMI value was 22.66 kg/m2 (IQR: 20.54–24.79) and 23.23 kg/m2 (IQR: 20.96–25.59) among GDM women without and with APO, respectively. The median daily physical exercise time was 55.00 min both in the GDM women with and without APO. GDM women without APO had statistically significant lower weight gain (8.40 kg, IQR: 4.60–11.40) during gestation than those with APO (9.10 kg, IQR: 5.60–12.10). In this study, GDM women with APO had slightly lower proportion of advanced maternal age, higher proportion of overweight and obese, but lower proportion of multipara than those without APO, the difference were all statistically significant (P < 0.01). Moreover, GDM women with APO had lower proportion of advanced education, and non-local resident than those without APO, but without statistically significant (Table 5).

Factors associated with the high abnormal plasma glucose percentage

In Fig. 3, logistic regression analysis with covariates adjustment indicated that GDM women aged 36–45 years (OR = 2.37, 95% CI 1.44–3.90), 31–35 years (OR = 1.62, 95% CI 1.02–2.56), and 26–30 years (OR = 1.44, 95% CI 0.92–2.24) had higher APG percentage than those aged 18–25 years. Moreover, GDM women with overweight/obese (OR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.34–2.16) had higher APG percentage than those with normal weight, and GDM women with more physical exercise time tended to have a lower APG percentage, the OR was 0.86 (95% CI 0.61–1.22) for 30–59 min/day, 0.55 (95% CI 0.39–0.79) for 60–89 min/day, 1.08 (95% CI 0.69–1.68) for 90–119 min/day and 0.77 (95% CI 0.40–1.48) for ≥ 120 min/day (Fig. 3).

Factors associated with the trajectory of high abnormal plasma glucose percentage based on logistic regression analysis among GDM women. Adjusted covariates include age group, education group, BMI group, pregnant status, daily physical exercise time and weight gain in gestation. The bold values indicate the OR was statistically significant (P < 0.05). BMI body mass index.

Factors associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes

In Fig. 4, the logistic regression analysis with the adjustment for covariates indicated that GDM women with overweight/obese (OR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.32–2.19) had higher APO risk than those with normal weight, and GDM women with more physical exercise time tended to have a lower APO risk, the OR was 0.81 (95% CI 0.58–1.13) for 30–59 min/day, 0.50 (95% CI 0.35–0.71) for 60–89 min/day, 0.97 (95% CI 0.63–1.50) for 90–119 min/day and 0.73 (95% CI 0.38–1.40) for ≥ 120 min/day. Moreover, primipara (OR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.25–2.09) had higher APO risk than multipara (Fig. 4).

Factors associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes based on logistic regression analysis among GDM women. Adjusted covariates include age group, BMI group, pregnant status, daily physical exercise time, types of physical activity and weight gain in gestation. The bold values indicate the OR was statistically significant (P < 0.05). BMI body mass index.

Association between physical exercise time and abnormal plasma glucose percentage

In general, the predicted percentage of APG decreased dramatically with the increase of physical exercise time when it was less than 60 min/day, but stabilized or even increased slightly with the increase of physical exercise time when it exceeded 90 min/day (Fig. 5). For GDM women in low APG group, the predicted APG percentage decreased continuously when physical exercise time was under 30 min/day, and stabilized when physical exercise time was 30–90 min/day, but decreased slightly again when physical exercise time exceeded 90 min/day (Fig. 6, Part A). For GDM women in high APG group, the predicted APG percentage decreased continuously with the increase of physical exercise time, but was all over 70% (Fig. 6, Part B).

The association between physical exercise time and the percentage of abnormal plasma glucose based on the restricted cubic spline among GDM women with in low APG group (A), with in high APG group (B), with ≤ 35 years old (C), with > 35 years old (D), with underweight/normal weight (E), with overweight/obese (F).

Subgroup analysis indicated that the APG percentages was all under 45% and decreased continuously with the increase of physical exercise time among GDM women aged ≤ 35 years (Fig. 6, Part C). The post-hoc power analysis indicated that with n = 1181 in the aged ≤ 35 years subgroup, the study achieved 90.1% power (α = 0.05, two-tailed) to detect a significant difference. For GDM women aged over 35 years, the predicted APG percentage decreased substantially when the physical exercise time was under 90 min/day, but increased gradually when physical exercise time exceeded 90 min/day (Fig. 6, Part D). The post-hoc power analysis indicated that with n = 267 in the age over 35 years subgroup, the study achieved 98.8% power (α = 0.05, two-tailed) to detect a significant difference.

For GDM women with underweight or normal weight, the predicted APG percentage decreased continuously when physical exercise time was under 90 min/day, but increased slowly when physical exercise time was over 90 min/day (Fig. 6, Part E). The post-hoc power analysis indicated that with n = 925 in the underweight or normal weight subgroup, the study achieved 88.6% power (α = 0.05, two-tailed) to detect a significant difference. For GDM women with overweight and obese, the predicted percentage of APG decreased substantially when physical exercise time was under 60 min/day, but decreased slightly when physical exercise time was over 60 min/day (Fig. 6, Part F). The post-hoc power analysis indicated that with n = 523 in the overweight and obese subgroup, the study achieved 92.4% power (α = 0.05, two-tailed) to detect a significant difference.

Discussion

GDM poses significant risks to maternal and neonatal health outcomes. Maternal complications include increased susceptibility to preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, and long-term progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus20, while neonatal consequences encompass macrosomia, hypoglycemia, and respiratory distress syndrome21. Maternal hyperglycemia disrupts fetal pancreatic development and insulin regulation, predisposing both generations to lifelong metabolic dysfunction22,23. In recent years, the implementation of new childbirth policies and intensified social pressures regarding child rearing issue induced a progressive decline in younger women alongside a marked increase in pregnant women with advanced maternal age. Moreover, the delayed pregnancy time among women has become an important factor inducing the elevated prevalence of GDM in China24,25. In our previous studies, we identified the negative correlation between physical exercise time and abnormal blood glucose percentage in GDM women17. Furthermore, we also noticed that multiparous women had lower efficacy in controlling blood glucose levels through physical exercise than primiparous women14,18. In this study, we identified that GDM women with advanced maternal age, overweight and obese need more physical exercise to achieve a lower APG percentage during pregnancy.

This present study applied GBTM to identify distinct trajectories of the APG percentage as a function of physical exercise time, and demonstrated that the APG percentage was higher among GDM women with advanced maternal age, overweight and obese. The increased risk of APG among GDM women with advanced maternal age may attribute to the high level of chronic inflammation, which may interfere with insulin signaling pathway, lead to increased insulin resistance, and then increase the risk of abnormal blood glucose26,27. Meanwhile, the increase of age is usually accompanied by the decrease of body metabolic rate, which might further aggravate the fluctuation of blood glucose during pregnancy. The increased risk of APG in GDM women with overweight and obese is related to their impact on the secretion of large amounts of free fatty acids and inflammatory factors by adipocytes, which exacerbate insulin resistance and make it difficult to maintain normal plasma glucose levels28.

In this study, the restricted cubic splines indicated that GDM women with advanced maternal age, overweight and obese had higher APG risk and need at least 60 min/day physical exercise to keep the APG percentage under 45%. Previous researches have indicated that physical exercise during pregnancy could increase the expression of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) in muscle cells. GLUT4 could enhance insulin sensitivity, improve glucose utilization and reduce insulin resistance, which provide a fundamental approach for glycemic control among GDM women29,30. Meanwhile, due to the significant association between obesity and APG, engaging in physical activities can further mitigate the risk of APG by increasing energy expenditure, improving body metabolism, and regulating maternal appetite, thereby promoting weight management31. Therefore, it is recommended that GDM women with advanced maternal age, overweight and obese should engage in physical exercise over 60 min/day to achieve plasma glucose control during pregnancy.

In this study, we also noticed that the predicted APG percentage among GDM women with advanced maternal age increased with the physical exercise time when exceeding 90 min/day. This might be due to the fact that GDM women with advanced maternal age was more likely to be advised by healthcare professionals to engage in more physical exercise, especially when the poor glycemic control was encountered. However, we should notice that the glycemic level was still high even when physical exercise time was over 90 min/day among some GDM women with advanced maternal age, indicating that additional intervention measures were required. The ACOG and the RCOG recommend that pregnant women should engage in over 150 min of moderate-intensity physical exercise weekly12,13. However, findings in this study suggested that GDM women with advanced maternal age, overweight and obese should engage in physical exercise for at least 60 min/day to achieve glycemic control, and additional intervention measures should be provided for those with unsatisfied glycemic control32,33. The poor glycemic control effect even with longer physical exercise time might be also attributed to the low intensity physical exercise types among GDM women in China. In the traditional Chinese cultural perception, pregnancy is viewed as a physiological state requiring augmented rest and nutritional support17. These deep-rooted beliefs contribute to the prevalent pattern among GDM women in China to favor low intensity physical exercise, with walking as the predominant exercise modality. This cultural preference may lead to an underestimation of the effectiveness of physical exercise interventions, so it is necessary to conduct more relevant research in regions with special cultural backgrounds. In addition, when conducting research on physical exercise interventions in regions with special cultural backgrounds such as China, it is recommended to focus on easier to implement types of physical exercise such as walking, housework, body stretching exercise to improve the compliance of research subjects. Moreover, no adverse events were observed or reported due to the high duration of the low intensity physical exercise among GDM women in this study.

In this study, we identified that GDM women with underweight or normal weight require less physical exercise to achieve plasma glucose control than those with overweight and obese, indicating the importance of weight control before pregnancy. However, we should also notice that the blood glucose level was still high among some GDM women with under or normal weight even when their physical exercise time was over 90 min/day, demonstrating that they were unable to achieve glycemic control through unique physical exercise. However, the reason for this phenomenon was still not clear which should be explored in the future study. So the monitor and whole round management of GDM women with underweight or normal weight is important for them to achieve good plasma glucose control, especially for those who was not sensitive to physical exercise.

The important strength of this study lies in the prospective cohort design with 1,448 GDM women, and data derived from the real-world clinical settings enhances the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, data in this study is extracted directly from the electronic health information records and antenatal care documents maintained by the hospital which lower the potential recall and measurement bias, is another strength. Furthermore, this study applies GBTM to identify distinct trajectories of the APG percentage as a function for physical exercise time, and employs the restricted cubic spline curves to flexibly model the dose–response relationship between physical exercise time and the APG percentage among GDM women, which could demonstrate the dynamic changes of blood glucose during pregnancy and offer valuable physical exercise guidance for GDM women, is also another strength in this study.

There are several limitations in this study. First, GDM women was recruited exclusively in Shanghai which ensured high internal authenticity, but the generalization of the findings to GDM women in other regions of China was limited. Second, data regarding the physical exercise assessment was collected through face-to-face interviews might introduce potential recall bias, which could systematically distort the collected data, cause deviation in specific directions and threaten the validity and credibility of research results. So the electronic device collecting real-time data on exercise should be considered in future studies. Third, the detailed dietary patterns and environmental factors associated with blood glucose control among GDM women were not collected and analyzed, which should be incorporated in future studies. So a multi-center study design with the incorporation of individualized physical exercise monitoring, detailed covariates information collection should be considered to enhance the validity and generalizability of findings.

Conclusions

Physical exercise over 60 min/day could effectively lower the APG risk among GDM women, but even over 90 min/day is less efficient for those with advanced maternal age, overweight and obese, so physical exercise incorporated with other intervention measures should be considered.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Koning, S. H. et al. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Current knowledge and unmet needs. J. Diabetes. 8(6), 770–781. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-0407.12422 (2016).

Sklempe Kokic, I. et al. Combination of a structured aerobic and resistance exercise improves glycaemic control in pregnant women diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus. A randomised controlled trial. Women Birth. 31(4), e232–e238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.10.004 (2018).

Johns, E. C., Denison, F. C., Norman, J. E. & Reynolds, R. M. Gestational diabetes mellitus: Mechanisms, treatment, and complications. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 29(11), 743–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2018.09.004 (2018).

Damm, P. et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus and long-term consequences for mother and offspring: a view from Denmark. Diabetologia 59(7), 1396–1399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-3985-5 (2016).

Filardi, T. et al. Impact of risk factors for gestational diabetes (GDM) on pregnancy outcomes in women with GDM. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 41(6), 671–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-017-0791-y (2018).

Gao, C., Sun, X., Lu, L., Liu, F. & Yuan, J. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Diabetes Investig. 10(1), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.12854 (2019).

Walker, J. D. NICE guidance on diabetes in pregnancy: Management of diabetes and its complications from preconception to the postnatal period. NICE clinical guideline 63. London, March 2008. Diabet. Med. 25(9), 1025–1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02532.x (2008).

Mottola, M. F. & Artal, R. Role of exercise in reducing gestational diabetes mellitus. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 59(3), 620–628. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000211 (2016).

Zhang, R. et al. Longer physical exercise duration prevents abnormal fasting plasma glucose occurrences in the third trimester: Findings from a cohort of women with gestational diabetes mellitus in Shanghai. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1054153. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1054153 (2023).

de Barros, M. C., Lopes, M. A., Francisco, R. P., Sapienza, A. D. & Zugaib, M. Resistance exercise and glycemic control in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 203(6), 556.e1-556.e5566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.07.015 (2010).

Brown, J. et al. Lifestyle interventions for the treatment of women with gestational diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5(5), CD011970. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011970.pub2 (2017).

Physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period: ACOG committee opinion, number 804. Obstet. Gynecol. 135(4), e178–e188 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003772

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Physical activity and pregnancy [EB/OL]. https://www.rcog.org.uk/for-thepublic/browse-our-patient-information/physical-activity-and-pregnancy/. Accessed February 19, 2025.

Gao, X. et al. More physical exercise is required for overweight or obese women with gestational diabetes mellitus to achieve good plasma glucose control during pregnancy: Finding from a prospective cohort in Shanghai. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 16, 3925–3935. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S439106 (2023).

Zhang, B. et al. Associations between trajectories of depressive symptoms and rate of cognitive decline among Chinese middle-aged and older adults: An 8-year longitudinal study. J. Psychosom. Res. 160, 110986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110986 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Associations between social and intellectual activities with cognitive trajectories in Chinese middle-aged and older adults: A nationally representative cohort study. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 12(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00691-6 (2020).

Wang, R. et al. Physical exercise is associated with glycemic control among women with gestational diabetes mellitus: Findings from a prospective cohort in Shanghai, China. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 14, 1949–1961. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S308287 (2021).

Wang, R. et al. Number of parous events affects the association between physical exercise and glycemic control among women with gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study. J. Sport Health Sci. 11(5), 586–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2022.03.005 (2022).

International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 33(3), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1848 (2010).

Aziz, F., Khan, M. F. & Moiz, A. Gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia as the risk factors of preeclampsia. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 6182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56790-z (2024).

Yu, Z. et al. Pre-pregnancy body mass index in relation to infant birth weight and offspring overweight/obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 8(4), e61627. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061627 (2013).

Davis, J. N., Gunderson, E. P., Gyllenhammer, L. E. & Goran, M. I. Impact of gestational diabetes mellitus on pubertal changes in adiposity and metabolic profiles in Latino offspring. J. Pediatr. 162(4), 741–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.001 (2013).

Venkatesh, K. K. et al. Impact of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus on offspring cardiovascular health in early adolescence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 232(2), 218.e1-218.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2024.04.037 (2025).

Zhu, H. et al. The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus before and after the implementation of the universal two-child policy in China. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 960877. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.960877 (2022).

Zhang, H. X., Zhao, Y. Y. & Wang, Y. Q. Analysis of the characteristics of pregnancy and delivery before and after implementation of the two-child policy. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 131(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.4103/0366-6999.221268 (2018).

Khalil, A., Syngelaki, A., Maiz, N., Zinevich, Y. & Nicolaides, K. H. Maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcome: A cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 42(6), 634–643. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.12494 (2013).

Cleary-Goldman, J. et al. Impact of maternal age on obstetric outcome. Obstet. Gynecol. 105(5 Pt 1), 983–990. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000158118.75532.51 (2005).

Catalano, P. M. & Shankar, K. Obesity and pregnancy: Mechanisms of short term and long term adverse consequences for mother and child. BMJ 356, j1. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1 (2017).

Warner, S. O., Yao, M. V., Cason, R. L. & Winnick, J. J. Exercise-induced improvements to whole body glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes: The essential role of the liver. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 567. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00567 (2020).

Peters, T. M. & Brazeau, A. S. Exercise in pregnant women with diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep. 19(9), 80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1204-8 (2019).

Sanabria-Martínez, G. et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions on preventing gestational diabetes mellitus and excessive maternal weight gain: A meta-analysis. BJOG 122(9), 1167–1174. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13429 (2015).

Mu, A., Chen, Y., Lv, Y. & Wang, W. Exercise-diet therapy combined with insulin aspart injection for the treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus: A study on clinical effect and its impact. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 4882061. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4882061 (2022).

Dingena, C. F. et al. Nutritional and exercise-focused lifestyle interventions and glycemic control in women with diabetes in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Nutrients 15(2), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15020323 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Roger Adams from University of Sydney for giving suggestions and comments for this manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (SHDC2022CRS053, SHDC2024CRX032), the Clinical Research Program of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (202240371), Intelligence Fund of Shanghai Skin Disease Hospital (2021KYQD01), Shanghai Talent Development Fund (2021073). These funders have no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors in this paper made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, agreed to submit to the current journal, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Review Board of Songjiang Maternal and Children’s Healthcare Hospital (IRB 2019-12-003). Informed consent was signed by each participant before the questionnaire interview.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, X., Zhang, X., Cai, R. et al. Advanced maternal age, overweight and obese positively correlate to the abnormal plasma glucose among gestational diabetes mellitus women even with physical exercise > 90 min/day: a prospective cohort study in Shanghai. Sci Rep 15, 21191 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09097-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09097-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Quality of life of women with gestational diabetes mellitus in a tertiary care hospital, Ajman, UAE: A cross-sectional descriptive study

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2025)