Abstract

In people with chronic spinal cord injury (SCI), the excitability of spinal reflexes of muscle afferent origins changes, likely contributing to sensorimotor impairments (e.g., spasticity). In contrast to changes in muscle afferent reflexes that are well-recognized, little is known about potentially altered processing of nociceptive and non-nociceptive cutaneous input in chronic incomplete SCI. Thus, this study aimed to systematically examine spinal processing of nociceptive and non-nociceptive cutaneous input in people with sensorimotor impairments due to chronic incomplete SCI, using non-invasive cutaneous nerve stimulation. To characterize non-nociceptive processing, cutaneous reflexes to non-painful stimulation was measured in the triceps surae; we found that the soleus reflexes were smaller and frequently inhibitory when they should be excitatory, suggesting altered processing of non-noxious cutaneous input in people with sensorimotor impairments due to chronic SCI. In parallel, when the persistence of pain pathway activation was assessed near the pain threshold, it was found robust and could be enhanced more with a higher input frequency. These key findings are discussed in the context of altered spinal neurophysiology in chronic incomplete SCI. This study supports potential utilities of electrical nerve stimulation in probing spinal non-nociceptive and nociceptive pathways in persons with SCI

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After spinal cord injury (SCI) disrupts supraspinal ascending and descending pathways, the excitability of spinal reflex pathways involving muscle afferents changes1,2,3,4,5. For example, in individuals with chronic incomplete SCI, in the plantarflexor soleus, the H-reflex, a partial electrical analog of the spinal stretch reflex, is larger6,7,8,9; reciprocal inhibition is diminished5,10,11; presynaptic inhibition is reduced6,12,13; recurrent inhibition is increased14; and Ib inhibition is reduced15. As to if and how the excitability of reflexes arising from cutaneous afferents is altered in chronic incomplete SCI, currently little is known. Cutaneous afferents come with different axonal diameters16,17,18,19. Excitation of large diameter low-threshold non-nociceptive Aβ afferents gives rise to the sensation of non-painful touch20 and produces non-noxious cutaneous reflexes16,21,22. Those non-noxious cutaneous reflexes are highly modulable and can be excitatory or inhibitory23,24,25,26,27,28. Excitation of smaller diameter high-threshold nociceptive Aδ afferents and C-fibers produces noxious sensation16,22,29 and reflex responses to painful stimuli [e.g., RIII reflexes (i.e., flexor or withdrawal reflex)]30,31,32,33,34. In people with chronic incomplete SCI, cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious stimuli are abnormally modulated during functional tasks/movements4,35,36; however, it is yet to be determined whether non-noxious cutaneous reflexes are hypo- or hyperexcitable compared to those in people without injuries. Altered amplitude modulation3,15,37,38,39,40 and heightened/reduced excitability6,9,10,41,42,43 are different kinds of reflex impairments44. Notably, when a reflex is present, even if its modulation pattern is abnormal, such presence indicates that the corresponding reflex pathway is accessible4,35,36,45,46 and therefore its excitability and modality (i.e., inhibitory/excitatory) can be assessed.

When SCI alters spinal somatosensory processing, it manifests in motor disorders such as spasticity, which affects 65–78% of this population47,48,49, as well as sensory disorder such as neuropathic pain (NP), which impacts up to 70% of individuals with SCI50,51,52. Despite the fact that pain management is a problem of a high priority among people with SCI53,54, spinal mechanisms of post SCI neuropathic pain are not well understood. Much of our limited knowledge on them comes from animal studies55,56,57,58; anatomical, physiological, and behavioral changes in nociceptive Aδ and C fiber afferents and interneurons that receive input from Aβ, Aδ, and C-fiber afferents could explain enhanced pain responses58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68, at least partly. In humans with SCI, when nociceptive fields were examined with nociceptive RIII reflexes, the receptive fields are expanded in foot sole69 and location specificity was diminished70. These support the possibility of enhanced nociceptive and reduced non-nociceptive processing in the spinal cord of individuals with SCI; yet to date, no studies have systematically examined spinal nociceptive and non-nociceptive processing in people with chronic incomplete SCI. Given the potential interactions between nociceptive and non-nociceptive processing in producing somatosensation at the spinal level71, it is important to study these pathways concurrently to better understand somatosensory impairments in chronic incomplete SCI.

Thus, to characterize spinal nociceptive and non-nociceptive processing concurrently in individuals with impaired somatosensory processing due to chronic incomplete SCI, we stimulated cutaneous nerves electrically and non-invasively in individuals with sensorimotor impairments (i.e., spasticity and/or neuropathic pain) due to SCI. Stimulating a peripheral nerve electrically creates a unique opportunity to examine spinal somatosensory processing comprehensively72,73,74,75,76. When we stimulate a bundle of nerve axons of different diameters and gradually increase the stimulus intensity, the afferents with larger diameters get excited first (i.e., at lower currents), and then, as we increase the stimulus intensity, more afferents with smaller diameters get excited. Thus, by purposefully setting the stimulus intensity with differences in axonal diameter in mind, we can examine the excitability (e.g., hypo- or hyperexcitable) of the spinal pathway originated from a targeted group of afferents. By electrically stimulating a cutaneous nerve at a non-noxious level, targeting large diameter Aβ afferents, non-noxious cutaneous reflexes can be measured as electromyographic (EMG) muscle responses77,78,79. When the same nerve is stimulated at noxious levels, smaller diameter Aδ and C-fiber afferents are recruited16 and nociceptive responses such as RIII reflexes can be observed. (Note that the peripheral nerve stimulation sufficiently strong to excite small diameter afferents and induce pain would also excite larger diameter afferents that convey non-noxious sensation.) In this study, we stimulated superficial peroneal nerve (SPn, innervating the foot dorsum), sural nerve (SRn, lateral aspect of the foot), and distal tibial nerve (DTn, medial aspect of foot extending toward the plantar surface of digits one through three) in individuals with sensorimotor impairment due to chronic incomplete SCI and individuals with no known neurological conditions. Cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious stimuli21 were examined in the triceps surae as a surrogate measure of spinal non-nociceptive processing. The threshold intensity that was perceived as painful was obtained as a measure reflecting spinal nociceptive processing.

Results

Stimulation intensities for investigating cutaneous reflexes

When determining nerve stimulation intensity, it is often based on the perceptual threshold (PerT) or radiating threshold (RT)4,24,25,78,80. In the present study, PerT was higher in SCI than in non-SCI for SPn, SRn, and DTn, and RT was higher in SCI than in non-SCI for SPn and DTn (P < 0.05 for both). The absolute stimulus current (mA) for 5 × PerT stimulation (among those in whom this level of stimulation was below the pain threshold) tended to be higher in SCI than in non-SCI, but it differed between the groups significantly for SPn (SCI: 15.1 ± 9.6 mA, Non-SCI: 10.0 ± 4.4 mA) (P = 0.049) and DTn stimulation (SCI: 12.3 ± 9.3 mA, Non-SCI: 6.7 ± 5.1 mA) (P = 0.048) but not for SRn (P > 0.05). Table 1 provides PerT and RT values for the SCI and non-SCI groups.

To assess where in the non-noxious stimulus current space the cutaneous reflexes were examined, the stimulus intensity used to elicit cutaneous reflexes was expressed as a multiple of the pain threshold (PainT), which was determined with 4 s inter stimulus-train interval (ITI) for each participant’s each nerve stimulated. For 5 × PerT stimulation, the intensities were 0.62 ± 0.17 (mean ± SD), 0.50 ± 0.23, and 0.62 ± 0.21 × PainT for SPn, SRn, and DTn stimulation in SCI, and 0.53 ± 0.21, 0.48 ± 0.16, and 0.46 ± 0.26 × PainT for SPn, SRn, and DTn stimulation in non-SCI. This verifies that 5 × PerT stimulation was indeed delivered within a non-noxious stimulus range, and thus, the elicited cutaneous reflexes were most likely originated from non-nociceptive cutaneous afferents. For 1 × and 1.5 × RT stimulation, Fig. 1 summarizes the relative range used for SPn, SRn, and DTn stimulation in SCI (a-c) and non-SCI (d-f), among those in whom 1.5 × RT stimulation was below the pain threshold. For SPn, SRn, and DTn stimulation, the relative stimulus intensity (i.e., expressed in × PainT) did not differ between the groups at 1 × and 1.5 × RT intensities (all P > 0.05, by one-tailed independent t test).

Expression of cutaneous nerve stimulus intensities used to elicit cutaneous reflexes in the non-noxious intensity space (i.e., below the pain threshold). Group data for 1 × and 1.5 × radiating threshold (RT) stimulus intensities expressed as a multiple of pain threshold (PainT) for the participants with SCI (a-c) and the participants without SCI (d-f). a and d for superficial peroneal nerve (SPn) stimulation, b and e for sural nerve (SRn) stimulation, and c and f for distal tibial nerve (DTn) stimulation. For each panel, each dashed line indicates each participant’s values, a colored solid line indicates the group average, and a shaded band indicates ± 1SD range. The number of participants in each dataset is indicated in top left of each panel.

Cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious stimuli

In this study, cutaneous reflexes were measured in the 80–120 ms post-stimulus onset time window, known as the medium latency response (MLR)4,81,82,83,84, since the MLR is a spinal reflex21,77,79,82,85,86, whose amplitude modulation can be robust4.

To characterize the excitability of spinal non-nociceptive pathway and its processing in SCI in comparison to non-SCI, cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious stimulation (i.e., MLR at 5 × PerT) were compared between the groups, per muscle and nerve (by independent t test). Figure 2a and b show examples of the soleus EMG sweeps highlighting MLR elicited with 5 × PerT of SPn stimulation from one participant with SCI (Fig. 2a) and one participant without SCI (Fig. 2b). Figure 2c-e summarizes MLRs in the soleus, medial gastrocnemius (MG), and lateral gastrocnemius (LG) elicited at 5 × PerT. In general, MLRs are smaller in SCI than in non-SCI; significant differences were found for soleus MLR with SPn (-0.19 ± 0.78%Mmax [SCI] vs. 0.55 ± 0.38%Mmax [non-SCI], P = 0.003), soleus MLR with SRn (-0.16 ± 0.74%Mmax [SCI] vs. 0.31 ± 0.18%Mmax [non-SCI], P = 0.04), and MG MLR with SRn (0.03 ± 0.23%Mmax [SCI] vs. 0.35 ± 0.39%Mmax [non-SCI], P = 0.01).

Triceps surae cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious stimuli in people with and without chronic incomplete SCI. a and b: 20 peristimulus EMG sweeps to 5 × perceptual threshold (PerT) level of superficial peroneal nerve (SPn) stimulation are superimposed for a person without SCI (a) and a person with chronic SCI (b). A pink highlighted time window indicates the window for the medium latency reflex (MLR). c: Amplitudes of soleus MLRs (group mean ± SD) to stimulation of the SPn, sural nerve (SRn), and distal tibial nerve (DTn) at 5 × PerT in individuals with SCI (filled bars) and without injuries (open bars). The reflex amplitudes are expressed in %maximum M-wave (Mmax)124. d: Amplitudes of MG MLRs to stimulation of the SPn, SRn, and distal DTn stimulation at 5 × PerT. e: Amplitudes of LG MLRs to stimulation of the SPn, SRn, and distal DTn stimulation at 5 × PerT. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the groups (p < 0.05). Each x symbol represents an individual’s value. The number of participants in each dataset is denoted next to the figure legend.

To examine if the spinal cord circuit can process different levels of non-noxious cutaneous input differently, we compared the MLR amplitudes between 1 × RT and 1.5 × RT stimulation, per group, muscle and nerve (by paired t test). Figure 3 shows the soleus, MG, and LG, MLRs at 1 × and 1.5 × RT stimulation in the non-SCI and SCI groups. In non-SCI, in two instances MLR at 1.5 × RT was larger than MLR at 1 × RT stimulation: soleus MLR with SPn (0.39 ± 0.25%Mmax [1 × RT] vs. 0.68 ± 0.48%Mmax [1.5 × RT], P = 0.007) and LG MLR SRn (0.13 ± 0.16%Mmax [1 × RT] vs. 0.33 ± 0.26%Mmax [1.5 × RT], P = 0.008). In SCI, MG MLR with SPn was larger at 1.5 × RT than at 1 × RT stimulation; -0.06 ± 0.23%Mmax [1 × RT] vs. 0.15 ± 0.27%Mmax [1.5 × RT], P = 0.04). No other differences between stimulus intensities were significant in SCI or non-SCI.

Triceps surae cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious stimuli (1 × and 1.5 × radiating threshold [RT] in people with and without chronic incomplete SCI. Each panel shows the amplitudes of the medium latency reflex (MLR, group mean ± SD) to stimulation of the superficial peroneal nerve (SPn), sural nerve (SRn), and distal tibial nerve (DTn) at 1 × and 1.5 × RT. a and d: Amplitudes of soleus MLRs. b and e: Amplitudes of MG MLRs. c and f: Amplitudes of LG MLRs. The reflex amplitudes are expressed in %maximum M-wave (Mmax). Mean values for individuals with SCI are shown in filled bars and mean values for individuals without injuries are shown in open bars. Asterisks indicate significant differences between 1 × and 1.5 × RT (p < 0.05). Each x symbol represents an individual’s value. The number of participants in a given dataset is indicated beneath the panels c and f.

Pain threshold and persistence of pain pathway activation

In this study, two kinds of pain thresholds were measured by ramping up and down the stimulus current in a triangular manner. PainTup was determined by gradually increasing the stimulus current to the point at which the stimulation becomes painful; and PainTdown was defined as the last stimulus intensity that is perceived to be painful when the current was gradually decreased. To characterize the excitability of spinal nociceptive pathway in SCI in comparison to non-SCI, measures of pain processing (e.g., PainT and ΔI [see below for description]) were compared between the groups, per nerve (by independent t test).

Pain thresholds (PainT) determined by gradually increasing the stimulus current (i.e., same as PainTup) with 4 s inter stimulus train interval (ITI) was significantly larger for SRn stimulation in SCI (21.4 ± 8.7 mA) than non-SCI (14.6 ± 6.1 mA) (P = 0.02) but did not differ significantly between SCI and non-SCI for SPn 22.6 ± 8.8 mA (SCI) vs. 19.7 ± 6.7 mA (non-SCI) (P = 0.18) or 18.3 ± 9.0 mA (SCI) vs. 14.0 ± 7.0 mA (non-SCI) for DTn (P = 0.1).

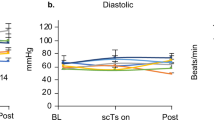

The difference between PainTup and PainTdown (i.e., difference in up- and downward threshold currents, ΔI) was also calculated as a surrogate measure of the persistence of pain pathway activation. Figure 4 shows ΔI obtained with 4 s and 1 s ITI, and the difference in ΔI between 4 and 1 s ITI (i.e., rate-dependent enhancement of pain) for SPn, SRn, and DTn stimulation in SCI and non-SCI. With 4 s ITI, ΔI did not differ significantly between the groups for any nerves stimulated (P = 0.12, 0.48, and 0.43 for SPn, SRn, and DTn, respectively). With 1 s ITI, ΔI was more prominent; 4.4 ± 2.1, 4.0 ± 2.9, and 3.6 ± 2.2 mA in SCI and 3.2 ± 1.3, 2.1 ± 0.7, and 1.9 ± 1.0 mA in non-SCI for SPn, SRn, and DTn stimulation, respectively, and larger in SCI than in non-SCI (P = 0. 05, 0.01, and 0.02 for SPn, SRn, and DTn, respectively). The rate-dependent enhancement of pain was stronger in SCI than in non-SCI two of three nerve conditions: 2.4 ± 1.8 mA [SCI] vs. 0.8 ± 0.6 mA [non-SCI], P = 0.002 for SRn and 2.2 ± 1.7 mA [SCI] vs. 0.7 ± 0.6 mA [non-SCI], P = 0.002 for DTn stimulation.

Persistence of pain pathway activation and rate-dependent enhancement of pain for individuals with and without SCI. Nerve stimulation conditions are color-coded: magenta for superficial peroneal nerve (SPn) stimulation, green for sural nerve (SRn) stimulation, and brown for distal tibial nerve (DTn) stimulation. For each nerve stimulated, the data for 4 s inter stimulus train intervals (ITIs), 1 s ITIs , and the difference between 4 s ΔI and 1 s ΔI (Diff.) are shown for individuals with (filled bars) and without SCI (open bars). Each x symbol represents an individual’s value. For a given nerve stimulation condition, the number of participants included in comparison is indicated in the right most set of bars.

Non-nociceptive cutaneous reflexes × persistence of pain pathway activation

When ΔI obtained with 1 s ITI was plotted against the amplitude of MLR reflexes elicited with 5 × PerT stimulation, very weak to strong correlation was observed per group and across all participants. In SCI, negative correlation was observed for the soleus and LG with SPn stimulation (r = -0.59 and -0.45). In non-SCI, only very weak to weak correlation was observed across all muscles and nerves stimulated (r = -0.002 to 0.38). When all data were plotted together, r values for the soleus MLR × ΔI were -0.57 for SPn (P = 0.003), -0.1 for SRn (P = 0.69), and 0.22 for DTn (P = 0.32) (Fig. 5). The correlation was very weak to weak for MG and LG; r values ranged from -0.41 to 0.24 across those 2 muscles × 3 nerve stimulation conditions (P > 0.05 for all).

Correlation between the soleus cutaneous reflex to non-noxious stimuli and the persistence of pain pathway activation in individuals with and without SCI. In each panel, the persistence of pain pathway activation (ΔI) is plotted against the amplitude of soleus medium latency reflex (MLR) elicited by 5 × PerT stimulation of the superficial peroneal nerve (left), sural nerve (middle), and distal tibial nerve (right). Each symbol represents each individual’s value. Filled symbols for participants with SCI. Open symbols for participants without SCI. The number of participants is indicated in each panel.

Relationship between the severity of pain or spasticity × persistence of pain pathway activation or non-nociceptive cutaneous reflexes

To assess whether a clinical measure of pain or spasticity is correlated with persistence of pain or non-nociceptive cutaneous reflexes, additional correlation analyses were performed. In participants with SCI, the correlation coefficient (r) for the Montreal Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) score × ΔI at 4 s ITI, MPQ × ΔI at 1 s ITI, and MPQ × rate-dependent ΔI enhancement was consistently positive across all three nerves stimulated (r = 0.08–0.58); yet, a statistically positive correlation was found only for MPQ ×Δ I with SPn stimulation at 4 s and 1 s ITI (P < 0.05 for both). In contrast, the correlation between MPQ and MLR at 5 × PerT was poor; r-values ranged -0.28 to + 0.31 across the three nerves stimulated and the three muscles studied (i.e., soleus, MG, and LG), with none being statistically significant.

The correlation for modified Ashworth Scale [mAS] × ΔI or mAS × rate-dependent ΔI enhancement was consistently negative (r = − 0.45 to − 0.05) but none was statistically significant across the three nerves. The correlation coefficient (r) between mAS and MLR varied across the nerves and muscles (from −0.32 to + 0.57); the significant positive correlation was found only for mAS × soleus MLR to DTn stimulation (r = 0.57, p < 0.05).

Discussion

This study investigated spinal nociceptive and non-nociceptive processing in people with sensorimotor impairments (i.e., with spasticity or neuropathic pain) due to chronic incomplete SCI and people without injuries, using non-invasive cutaneous nerve stimulation. To characterize the excitability of spinal non-nociceptive pathways, cutaneous reflexes to non-painful 5 × PerT stimulation was measured; we found that the soleus cutaneous reflexes to SPn or SRn stimulation, which are normally excitatory, were less consistently present and frequently inhibitory across people with chronic incomplete SCI, suggesting impaired processing of non-noxious cutaneous input in this population. To assess whether the cutaneous input within the non-noxious range is processed in a graded manner, cutaneous reflexes were compared between l × and l.5 × RT stimulation; the reflex amplitude difference between l × and l.5 × RT was not very apparent – observed only in 2/9 muscle × nerve combinations in participants without SCI and 1/9 combinations in participants with chronic incomplete SCI. To quantitatively express the potency of pain pathway activation, ΔI (i.e., gap between PainTup and PainTdown during a triangular increase and decrease of stimulus current) was measured; we observed larger ΔI with 1 s ITI for SPn, SRn, and DTn and rate dependent enhancement of pain for SRn and DTn stimulations in participants with chronic incomplete SCI. The measures of ΔI were weakly positively correlated with the clinical pain measure of MPQ in participants with SCI across all three nerves stimulated with statistical significance found only for SPn stimulation, supporting the potential utility of SPn stimulation in indicating enhanced nociceptive processing. Below we discuss these key findings from the neurophysiological perspectives, towards understanding altered excitability of spinal non-nociceptive and nociceptive pathways in people with sensorimotor impairments due to chronic incomplete SCI and demonstrating the potential utility of electrical nerve stimulation in proving spinal non-nociceptive and nociceptive pathways in health and diseases.

This study found that the soleus MLRs to non-noxious cutaneous nerve stimulation were inconsistently present among individuals with chronic incomplete SCI; this was clear with SPn and SRn stimulation that normally produce excitatory response. At the spinal level, cutaneous afferents, interneurons, and motoneurons are involved in producing cutaneous reflexes, and therefore, changes in their excitability could contribute to producing smaller or larger responses or inhibitory instead of excitatory (or vice versa) responses. First, if the excitability of motoneurons is reduced, it would result in smaller cutaneous reflexes. However, this is a less-likely mechanism in the present study population, since the present group of participants with chronic incomplete SCI were mostly clinically spastic and the excitability of spinal motoneurons (or at least the excitability of motoneurons to muscle spindle afferent input2,4,5,10,11,43) is not low but tends to be high in spastic individuals with chronic SCI87,88,89. Second, if the effectiveness of 5 × PerT intensity stimulation in exciting non-nociceptive Aβ afferents is compromised, e.g., due to the reduced excitability of non-nociceptive afferents, then, that would produce less input to interneurons that excite motoneurons. In the present study, the 5 × PerT stimulation in participants with SCI was 11.8 ± 7.3 mA equivalent of 0.6 ± 0.2 × PainT across three nerves stimulated, larger than that in participants without SCI (8.2 ± 4.4 mA, equivalent of 0.5 ± 0.2 × PainT). Existing animal studies do not provide indications on if/how the excitability of non-nociceptive afferents changes in chronic incomplete SCI. Altogether, the currently available data and studies do not support the possibility that 5 × PerT stimulation would produce weaker excitation of non-nociceptive afferents in participants with SCI (although this remains to be confirmed). Third, thus, at the spinal level, the most likely mechanisms of altered cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious input lie in altered interneurons and their network that serve as the bridge between the afferents and motoneurons17,58,90.

Spinal interneurons in the dorsal horn receive input from multiple afferent sources (i.e., including muscle, skin, load, and joint receptors91,92,93,94 either directly or indirectly91,95,96,97,98. Since the excitability of those interneurons is regulated by supraspinal descending drive13,85,99, after SCI disrupts such drive, the excitability of interneurons that convey and process non-nociceptive input from Aβ afferents may be diminished. The excitability of those non-nociceptive interneurons may also be impacted by enhanced activity of nociceptive interneurons58. This possibility is further discussed in the section below.

In the present study, as an extension of cutaneous reflex excitability assessment, we extended the range of non-noxious cutaneous inputs to examine if/how the spinal cord would process the difference in cutaneous input within the non-noxious range. When the reflexes were compared between the two intensities of l × and l.5 × RT, they differed only occasionally in both participants with and without SCI. In considering where in the non-nociceptive cutaneous input space these reflexes were examined, we expressed the stimulus intensities as proportion of the pain threshold (Fig. 1). This helped to visualize the input range covered by l × and l.5 × RT, which were 0.47–0.68 × PainT on average across three nerves stimulated for participants with chronic incomplete SCI and 0.46–0.70 × PainT for participants without SCI. The implication from this analysis is that the 0.22–0.24 × PainT extent of non-nociceptive cutaneous input (i.e., Aβ excitation) difference might be processed only marginally differently during static standing. The spinal pathways may process the gap more clearly if the input difference is larger, delivered during a dynamic motor task such as walking23,25, or occupied a different range within the non-noxious range (e.g., 1.9 × and 2.3 × RT25). These possibilities are to be explored in future studies.

In this study, to quantify the persistence of pain pathway activation, we measured the pain thresholds with a triangular increase and decrease of stimulus current and calculated the threshold gap, ΔI; thus, the larger ΔI the stronger the persistence of pain pathway activation would be. We found that ΔI tended to be larger in individuals with chronic incomplete SCI than in individual without, suggesting enhanced pain pathway activation in people with incomplete SCI. This trend was clearer with 1 s ITI than 4 s, partially reflecting a more robust rate-dependent enhancement of pain pathway activation. The present findings are in agreement with Hornby et al.100 who investigated the windup of flexion reflexes by stimulating the plantar surface of the foot. Hornby et al. found that reflex facilitation with sub-threshold stimuli occurs with 1 s ITI but not with longer ITIs, and that reflex windup with supra-threshold stimuli occurs with ITI of ≤ 3 s but not with longer ITIs. Thus, we believe the validity of measuring pain thresholds with 4 s ITI; however, we cannot completely discard a possibility that using an ITI of > 4 s might have resulted in a more robust assessment of rate-dependent pain enhancement. To better characterize spinal pain processing in people with and without chronic incomplete SCI, this ITI issue would warrant more thorough investigation of its own in future studies. While more details of the ITI—pain pathway activation relation remain to be clarified, the present findings suggest the potential utility of electrical nerve stimulation in characterizing spinal nociceptive processing in chronic incomplete SCI. The positive correlation between MPQ and ΔI measures to SPn stimulation found in this study further support such possibilities.

As to a spinal mechanism of enhanced persistence of pain pathway activation in individuals with sensorimotor impairments due to chronic incomplete SCI, an increase in the excitability of nociceptive afferents is unlikely, since the PainT itself was not reduced in the present group of participants with chronic incomplete SCI. This leaves altered excitability and/or behaviors of spinal interneurons that receive input from nociceptive afferents and/or changes at afferent – interneuron synapses as potential spinal mechanisms of abnormal pain pathway activation in this population. Reduced inhibition of interneurons that receive input from nociceptive afferents is a possible mechanism; in rats with SCI, GABAergic inhibitory neurons in the dorsal horn are lost17,58,101,102,103, which could explain a sign of hyperalgesia (e.g., a reduction in the stimulus required to elicit a withdrawal response) in those animals102 (see103 also). Aberrant sprouting of Aδ and C afferents as well as Aβ in the superficial layers in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord beyond their typical termination zones observed in animals with SCI59,60,61,62,63,64,104,105 could also change the spinal pain processing58,106; for instance, interneurons that are responsive specifically to nociceptive input could become responsive also to non-noxious input65 and continue firing even after cessation of noxious stimulation66,67,68. These changes would also help to explain allodynia among individuals with neuropathic pain. Altered excitability and firing behaviors in wide dynamic range (WDR) neurons, a class of spinal interneurons that receive multimodal nociceptive and non-nociceptive input, including noxious and non-noxious cutaneous input107,108, could also be a part of prolonged pain pathway activation. The firing rate of WDR neurons increases with increasing stimulus intensity (e.g., from innocuous light touch to noxious pinch)109,110, and it increases further in response to continual nociceptive input, which in turn can reinforce the pain state via a positive feedback loop. Either reduced inhibition of WDR neurons from Aβ afferent input (directly or indirectly) or disinhibition of WDR neurons by Aδ and C-fiber afferents (directly or indirectly) would result in enhanced pain perception above the spinal cord111. In sum, presynaptic or postsynaptic alteration of the excitability and/or firing behaviors of interneurons likely contributed to persistent pain pathway activation observed in the present group of individuals with chronic incomplete SCI.

In the present study, we observed inconsistent and altered cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious stimuli and enhanced persistence of pain pathway activation in participants with spasticity or neuropathic pain due to chronic incomplete SCI, suggesting the concurrent occurrence of altered non-nociceptive processing and enhanced nociceptive processing in this population. The present correlation analyses between MLR and ΔI suggest that the nociceptive and non-nociceptive processing is not immediately correlated as default (i.e., in people without injuries), however. Interestingly, in participants with chronic incomplete SCI, a negative correlation for MLR × ΔI appears with SPn stimulation, in part due to the concurrence of more inhibitory non-nociceptive reflexes and pain persistence much stronger than that observed in individuals without SCI. It is possible that the observed negative correlation is a product of SCI-induced adaptive plasticity112, or a partial reveal of existing neurophysiological link between the nociceptive and non-nociceptive processing71. Admittedly, the present observations alone are not sufficient to adequately discuss whether the same neural substrates or pathways are involved in both the nociceptive and non-nociceptive processing in the human spinal cord. Yet, it should still be noted that there are interneurons whose dendrites extend from laminae III where non-nociceptive Aβ afferents terminate to laminae I where nociceptive afferents terminate113 and that stimulating Aβ afferents can influence transmission of nociceptor afferents likely via inhibitory interneurons114,115. Clearly, more mechanistic studies are needed to determine whether and to what extent nociceptive and non-nociceptive pathways interact in the spinal cord of people with sensorimotor impairments (e.g., spasticity and neuropathic pain) due to chronic incomplete SCI and people without neurological injuries.

Implications

This study used non-invasive cutaneous nerve stimulation concurrently to characterize spinal processing of nociceptive and non-nociceptive cutaneous input in individuals with sensorimotor impairments due to chronic incomplete SCI. The findings from this study show that spinal processing of non-noxious cutaneous input is inconsistent and altered while the processing of nociceptive input is enhanced in this population. Overall, in the lower leg, these key observations are more readily spotted in the soleus muscle with SPn or SRn stimulation, and thus, these muscle – nerve combinations could serve as useful tools for proving spinal non-nociceptive and nociceptive pathways. MG or LG responses and responses to DTn stimulation were more variable across individuals even without SCI, leading to less certainty of their potential utilities for diagnostic or characterization purposes, at the moment.

With non-invasive nerve stimulation, by electrically stimulating the nerve axon bundle at different stimulus intensities, we can examine non-nociceptive and nociceptive processing in a predictable manner, helping to estimate the targeted pathways’ excitation threshold and their proportional recruitment116,117,118,119. In using peripheral nerve stimulation for examining spinal pathways and their excitability characteristics, what afferents are stimulated at what stimulus intensities should be kept in mind. While weaker non-noxious stimulation likely excites non-nociceptive Aβ afferents with larger axonal diameters only, the stimulation sufficiently strong to induce pain sensation excites smaller diameter nociceptive Aδ and C fiber afferents and larger diameter Aβ afferents. Thus, a sensation or muscle response elicited by noxious stimuli would be a product of mixed effects of nociceptive and non-nociceptive input arrived and processed in the spinal cord, at least partly. In such spinal processing (i.e., via interneuron circuits), different afferent input could be weighted differently (i.e., enhanced or suppressed)28,36,82,120, in different individuals (e.g., people with SCI or without) and in different posture or sensorimotor tasks (e.g., at rest or during active muscle contraction)120,121,122. These facts and issues differentiate electrical nerve stimulation from mechanical stimulation over skin surface100,123, which would excite only the sensory endings located in the skin that receive direct stimulation. Not limited to the specific experimental procedures used in this study, it would be quite possible to use non-invasive electrical stimulation of a cutaneous nerve with many different intensities and/or intervals to investigate and characterize the excitability, modulation, and plasticity of spinal nociceptive and non-nociceptive pathways in people with chronic incomplete SCI.

Note that since both SCI and non-SCI groups contained participants over wide age ranges, with the SCI group’s mean age being higher, the age is a methodological limitation of the present study. To address this potential aging effect concerns, we assessed the presence and extent of study measures × age correlation in each group (see Methods–Participants). Pearson’s r values were not significant for all measures in both groups. Thus, the impact of age difference on the study findings was likely limited.

Methods

Participants

Seventeen individuals with sensorimotor impairment due to chronic incomplete spinal cord damage (11 males, 6 females) aged 39–74 yrs (55.5 ± 9.8 years, mean ± SD) and thirteen individuals with no known neurological conditions (6 males, 7 females) aged 24–60 yrs (40.2 ± 11.2 years) participated in this study. Profiles of individuals with SCI are summarized in Table 2. Prior to testing, all participants provided written informed consent that was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of South Carolina. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Since both SCI and non-SCI groups contained participants over wide age ranges, and the SCI group’s mean age was higher, Pearson’s r (correlation coefficient) between different study measures and participant age was calculated in each group. For each and all of the soleus, MG, and LG MLRs elicited by SPn, SRn, or DTn stimulation at 5 × perceptual threshold (PerT), the correlation with age was not significant in either the SCI group or non-SCI group (P > 0.05 for all). Similarly for the age × ΔI correlation was not statistically significant for 4 s ITI or 1 s ITI and for SPn, SRn, or DTn stimulation (P > 0.05 for all in both groups). Thus, it is unlikely that the difference in age between the groups influenced the study findings in major ways.

For participants with SCI, the inclusion criteria were (1) neurologically stable (> 1 year after lesion, and no changes to medication for the past 3 months), (2) at least unilateral presentation of clinical spasticity in the plantarflexors (e.g., increased muscle tone, ≥ 1 on modified Ashworth Scale [mAS]) or at least unilateral presentation of clinical pain in the lower extremity (e.g., score of ≥ 20 on the Montreal Pain Questionnaire [MPQ]), (3) medical clearance to participate, and (4) ability to stand with or without an assistive device for 3 min. Note that chronic stable use of anti-spasticity medication such as baclofen and gabapentin was accepted. Exclusion criteria were (1) motoneuron injury, (2) known cardiac conditions, (3) medically unstable conditions (including pregnancy), (4) cognitive impairment, (5) uncontrolled peripheral neuropathy, (6) extensive use of electrical spinal stimulation (transcutaneous or epidural) for pain treatment, (7) daily use of electrical stimulation (e.g., foot-drop stimulator), and (8) complete lack of cutaneous sensation around the foot. In each participant with SCI, the more affected leg was studied. The more affected leg was defined as the one with more severe spasticity, or if the person also had neuropathic pain, the one with more severe pain and spasticity. The presence of spasticity and/or neuropathic pain was confirmed with standard clinical examination and medical record review performed by a licensed research therapist (BHSD).

For participants without SCI, inclusion criterion was 1) ability to stand with or without an assistive device for 3 min. Exclusion criteria were free from (1) known neurological conditions and (2) lower limb orthopedic injuries within the past year.

General procedures

For each participant, all data were collected in a single experimental session. At the beginning of the session, electromyography (EMG) recording electrodes were placed over the triceps surae and tibialis anterior (TA). Then, by stimulating the posterior tibial nerve in the popliteal fossa, the maximum M-wave (Mmax) was measured for each of the triceps surae [soleus, medial gastrocnemius (MG), and lateral gastrocnemius (LG)] while the participant stood and maintained the natural standing level of soleus and TA EMG activity. Next, the SPn, SRn, and DTn stimulating electrodes were placed around the ankle, and the perceptual threshold (PerT) and radiating threshold (RT) were obtained with SPn, SRn, and DTn stimulation separately during standing. Then, cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious stimuli were elicited while the participants stood and maintained the natural standing level of soleus and TA EMG activity (see EMG and nerve stimulation). Finally, the two kinds of pain thresholds were measured by ramping up and down the stimulus current in a triangular manner during standing (see EMG and nerve stimulation below). During the experimental session, a two-wheeled walker was placed in front of the participant. The participant was allowed to use the walker for balancing during standing as needed.

EMG and nerve stimulation

EMG signal was recorded continuously from the soleus, MG, LG, and TA ipsilateral to the stimulation site, using pairs of self-adhesive surface Ag–AgCl electrodes (2.2 × 3.3 cm, Vermed/ Nissha Medical Technologies, Buffalo, NY) with their centers ~ 3 cm apart. TA, MG, and LG electrodes were placed over the muscle belly, and soleus electrodes were placed below the gastrocnemii and in line with the Achilles tendon as reported in previous studies that examined EMG and reflexes in these muscles4,45,46,120,121,122,124,125,126,127 (for visualization of electrode locations, see Fig. 1 of4 and127). EMG signals were amplified and bandpass filtered at 10–1000 Hz (AMT-8, Bortec Biomedical, Calgary, AB, Canada), and sampled and stored at 4000 Hz (Axon Digidata 1440A, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

To obtain the Mmax in each of the triceps surae (i.e., soleus, MG, and LG), the posterior tibial nerve was stimulated in the popliteal fossa using Ag–AgCl electrodes (2.2 × 2.2 cm for the cathode and 2.2 × 3.3 cm for the anode, Vermed). Single square pulses (typically 1 ms in pulse-width) were delivered through a Digitimer DS7A constant current stimulator (Digitimer Limited, Letchworth Garden City, UK) while the participant stood and maintained the natural standing level of soleus and TA EMG activity. This natural standing level of background EMG corresponded to 13–19 µV (in SCI) and 14–20 µV (in non-SCI) of absolute EMG activity for the soleus and < 7 µV for the TA in both groups. The minimum inter-stimulus interval was 5 s. The tibial nerve stimulus intensity was increased gradually from below soleus H-reflex threshold level to the maximum H-reflex (Hmax) to beyond a level that was required to elicit the Mmax4,124,125,128. Typically, two to four responses were averaged at each stimulus level including the Mmax level.

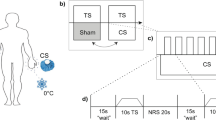

To stimulate cutaneous nerves, pairs of 2.2 × 2.2 cm electrodes were placed near the ankle to target each of the SPn, SRn, and DTn innervation area of the skin. For SPn stimulation, an anode was placed near the anterior portion of the ankle and a cathode on the foot dorsum. The SRn was stimulated posteriorly to the lateral malleolus while the DTn was stimulated posteriorly and/or distally to the medial malleolus (Fig. 6). Cutaneous nerve stimulation was delivered as a train of five 1 ms pulses at 200 Hz through a Grass S48 stimulator (Natus Neurology Grass, Warwick, RI) and a Digitimer DS7A constant current stimulator (Digitimer Limited). Cutaneous nerve locations were optimized to generate the strongest cutaneous sensation over the largest skin area at a given stimulus current. Once optimized, PerT (i.e., smallest stimulus intensity that produces discernible sensation) and RT (i.e., smallest stimulus intensity that produces radiating paresthesia over the maximum skin area) were determined in standing.

Experimental setup. a: Locations of cutaneous nerve stimulating electrodes; the nerve stimulated are the superficial peroneal nerve (SPn), sural nerve (SRn), and the distal tibial nerve (DTn). b: An example of stimulus current control during pain threshold detection with 1 s inter stimulus train interval (ITI). Each dot indicates delivery of a stimulus train. PainTup: stimulus current at which the stimulation became first painful. PainTdown: the last stimulus current at which the stimulation was painful. See text for detailed descriptions.

To measure cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious stimuli, each cutaneous nerve was stimulated at the 5 × PerT current intensity while the participant stood and maintained the natural standing level soleus and TA EMG activity. If a participant perceived 5 × PerT stimulation as painful, this portion of the experimental procedure was skipped. To assess how/if the spinal cord processes different intensities of non-noxious cutaneous input, cutaneous reflexes to 1 × and 1.5 × RT levels of stimulation were also measured. For each stimulus intensity (i.e., 5 × PerT, 1 × RT, and 1.5 × RT), 20 responses were obtained while the participant stood and maintained the natural standing level soleus and TA EMG activity.

To measure the pain thresholds, the cutaneous nerve stimulation current was gradually increased and decreased in a triangular manner with 1 s and 4 s inter stimulus train intervals (ITIs) during standing. For each ITI, two pain thresholds were measured: PainTup and PainTdown. PainTup was determined by gradually (i.e., by 1–2 mA, every two stimulus trains) increasing the stimulus current from PerT to the point at which the stimulation became painful. At the intensity that was perceived as painful the first time (i.e., PainTup), four trains were delivered. Then the stimulus current was gradually decreased by ≈1 mA steps every two trains until the stimulation was no longer painful. PainTdown was defined as the last stimulus intensity that was perceived to be painful. A specific set of descriptors were used to determine these pain thresholds. The occurrence of one or more of the following sensations was defined as pain experience: “sharp,”, “burning,” “drilling,” “aching, and “stinging”129.

Data analysis

Mmax

For each of the triceps surae, Mmax sizes was calculated in the full-wave rectified EMG signal as the difference between the background (i.e., prestimulus) EMG and the mean amplitude over the M-wave window. Typically, the M-wave was measured over 6–22 ms post-stimulus period for the soleus and 5–20 ms post-stimulus for the MG and LG4,45,124. In addition, to aid the description of participants with SCI, the maximum H-reflex (Hmax) was also calculated from the triceps surae recruitment curve measurement and expressed as a % Mmax. The Hmax values were 51.1 ± 32.4%Mmax [SCI] and 45.5 ± 23.3%Mmax [non-SCI]) for the soleus (see Table 2), 29.1 ± 24.1%Mmax [SCI] and 14.7 ± 7.2%Mmax [non-SCI] for the MG, and 29.0 ± 25.7%Mmax [SCI] and 20.6 ± 12.4%Mmax [non-SCI] for the LG.

Cutaneous reflexes

Cutaneous reflexes can be measured in two latency components: short latency response (typically measured over 50–80 ms post-stimulus onset) and medium latency response (MLR, over 80–120 ms post-stimulus onset)4,81,82,83,84. While both reflex components reflect spinal non-nociceptive processing21,77,79,82,85,86, amplitude modulation tends to be more robust with MLRs4. Thus, we examined MLRs for the purposes of this study. For each nerve stimulation condition for each participant, the MLR window was determined individually with visual inspection of the averaged EMG sweep. If no discernable MLR was present, the latency window of 80–120 ms post stimulus onset that was used for MLR4,83,130,131,132. The MLR amplitude was calculated on the full-wave rectified EMG as the difference between the EMG amplitude over an MLR window and the background EMG calculated over 50 ms of prestimulus period. MLR amplitude was calculated for each trial first, and then 20 MLR values were averaged together for each participant’s each nerve stimulation condition. To compare cutaneous reflexes amplitudes between the groups (i.e., at 5 × PerT) or between the intensities (i.e., 1 × and 1.5 × RT), MLR reflex amplitude was normalized to the Mmax for each participant’s each triceps muscle.

Expression of cutaneous nerve stimulus intensities

In the present study, we used three relative levels (i.e., 5 × PerT, 1 × RT, and 1.5 × RT) of non-noxious cutaneous nerve stimulation to examine cutaneous reflexes. To assess where in the non-noxious stimulus current space these reflexes were examined, each of the 5 × PerT, 1 × RT, and 1.5 × RT stimulus intensities was expressed as a multiple of the pain threshold (PainT). For this, PainT was the same as PainTup measured with 4 s ITI.

Persistence of pain pathway activation

The difference (or gap) between PainTup and PainTdown (i.e., difference in up- and downward pain threshold currents, ΔI) reflects “how much reduction in input current is needed to turn off the persistent activation of pain pathway.” Thus, ΔI was treated as a surrogate measure of the persistence of pain pathway activation. Conceptually, this measure shares some similarities with the analysis of dendritic persistent inward current in motoneurons89,133,134,135,136,137. For each participant’s each nerve stimulated, ΔI was calculated separately for 1 s and 4 s ITIs.

Rate-dependent enhancement of pain

To examine the presence and extent of a rate-dependent enhancement of pain, the difference in ΔI between 1 s ITI and 4 s ITI conditions was calculated. The greater ΔI difference between the two ITIs would indicate the greater rate-dependent enhancement of pain pathway activation. ΔI difference of “0” means no rate-dependent enhancement.

Statistical analysis

With cutaneous nerve stimulation and non-noxious cutaneous reflexes, nerve specificity and inter-muscle differences in how the reflexes appear (i.e., inhibitory or excitatory) are well known79,82,138. Thus, in this study, to address the question of whether the values of a study measure are different between the SCI group and the non-SCI group, we used independent t test on SCI vs. non-SCI, instead of group × nerve or group × muscle 2-way ANOVA. Participant characteristics, PerT and RT, stimulus intensities, MLRs at 5 × PerT, PainT, and ΔI were all analyzed this way. For the assessment of whether the spinal cord would process two different levels of non-noxious cutaneous input, 1 × RT vs. 1.5 × RT cutaneous reflex comparisons were made using a paired t test within each group. For these 1 × RT vs. 1.5 × RT comparisons, the sample size became smaller than those of between-group comparisons, since RT could not be established and/or a stimulus current for 1 × or 1.5 × RT were perceived as painful129 in some of the participants. To evaluate if the extent of non-nociceptive stimulus range covered by 1 × and 1.5 × RT stimulation differed between the groups, the stimulus intensity range expressed in × PainT was also assessed with independent t test. For all independent t tests, variances were tested with Levene’s test for equality of variances. When equal variance could not be assumed, the degrees of freedom were adjusted. Homogeneity was assessed with Levene’s test for equality of variances. When equal variances could not be assumed, un-pooled variances and a degrees of freedom correction was applied. Note that in no part of the statistical analysis, a given set of measures (e.g., MLR to SRn stimulation at 5xPerT) was compared through multiple t-tests.

To evaluate whether cutaneous reflex measures are related to ΔI obtained with 1 s ITI, Pearson’s r (correlation coefficient) for cutaneous reflexes × ΔI was calculated for each muscle and nerve. In addition, to assess whether a clinical measure of pain or spasticity is correlated with persistence of pain or non-nociceptive cutaneous reflexes, in participants with SCI, Pearson’s r was calculated for MPQ score × ΔI at 4 s ITI, MPQ × ΔI at 1 s ITI, MPQ × rate-dependent ΔI enhancement, MPQ × MLR at 5 × PerT stimulation, mAS score × ΔI at 4 s ITI, mAS × ΔI at 1 s ITI, mAS × rate-dependent ΔI enhancement, and mAS × MLR at 5 × PerT stimulation.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Version 28 and α level was set at 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Crone, C., Johnsen, L., Biering-Sørensen, F. & Nielsen, J. Appearance of reciprocal facilitation of ankle extensors from ankle flexors in patients with stroke or spinal cord injury. Brain 126, 495–507 (2003).

Thompson, A. K., Estabrooks, K. L., Chong, S. & Stein, R. B. Spinal reflexes in ankle flexor and extensor muscles after chronic central nervous system lesions and functional electrical stimulation. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 23, 133–142 (2009).

Stein, R., Yang, J., Belanger, M. & Pearson, K. Modification of reflexes in normal and abnormal movements. Prog. Brain Res. 97, 189–196 (1993).

Phipps, A. M. & Thompson, A. K. Altered cutaneous reflexes to non-noxious stimuli in the triceps surae of people with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 129, 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00266.2022 (2023).

Boorman, G., Lee, R., Becker, W. & Windhorst, U. Impaired, “natural reciprocal inhibition” in patients with spasticity due to incomplete spinal cord injury. Electroencephalograph. Clin. Neurophysiol. Electromyograph. Motor Control 101, 84–92 (1996).

Ashby, P., Verrier, M. & Lightfoot, E. Segmental reflex pathways in spinal shock and spinal spasticity in man. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 37, 1352–1360 (1974).

Hiersemenzel, L.-P., Curt, A. & Dietz, V. From spinal shock to spasticity: neuronal adaptations to a spinal cord injury. Neurology 54, 1574–1582 (2000).

Mailis, A. & Ashby, P. Alterations in group Ia projections to motoneurons following spinal lesions in humans. J. Neurophysiol. 64, 637–647 (1990).

Taylor, S., Ashby, P. & Verrier, M. Neurophysiological changes following traumatic spinal lesions in man. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 47, 1102–1108 (1984).

Ashby, P. & Wiens, M. Reciprocal inhibition following lesions of the spinal cord in man. J. Physiol. 414, 145–157 (1989).

Boorman, G., Hulliger, M., Lee, R. G., Tako, K. & Tanaka, R. Reciprocal Ia inhibition in patients with spinal spasticity. Neurosci. Lett. 127, 57–60 (1991).

Burke, D. & Ashby, P. Are spinal “presynaptic” inhibitory mechanisms suppressed in spasticity?. J. Neurol. Sci. 15, 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-510x(72)90073-1 (1972).

Calancie, B. et al. Evidence that alterations in presynaptic inhibition contribute to segmental hypo-and hyperexcitability after spinal cord injury in man. Electroencephalograph. Clin. Neurophysiol. Evoked Potent. Sect. 89, 177–186 (1993).

Shefner, J. M., Berman, S. A., Sarkarati, M. & Young, R. R. Recurrent inhibition is increased in patients with spinal cord injury. Neurology 42, 2162–2162 (1992).

Morita, H. et al. Lack of modulation of Ib inhibition during antagonist contraction in spasticity. Neurology 67, 52–56 (2006).

Collins, W., Nulsen, F. E. & Randt, C. T. Relation of peripheral nerve fiber size and sensation in man. Arch. Neurol. 3, 381–385 (1960).

Todd, A. J. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 823–836. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2947 (2010).

Harper, A. A. & Lawson, S. N. Electrical properties of rat dorsal root ganglion neurones with different peripheral nerve conduction velocities. J. Physiol. 359, 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015574 (1985).

Ward, A. R. in Comprehensive Biomedical Physics (ed Anders Brahme) 231–253 (Elsevier, 2014).

Lai, H. C., Seal, R. P. & Johnson, J. E. Making sense out of spinal cord somatosensory development. Development 143, 3434–3448. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.139592 (2016).

Van Wezel, B. M. H., Van Engelen, B. G. M., Gabreëls, F. J. M., Gabreëls-Festen, A. A. W. M. & Duysens, J. Aβ fibers mediate cutaneous reflexes during human walking. J. Neurophysiol. 83, 2980–2986. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2980 (2000).

Gasser, H. S. & Erlanger, J. The rôle played by the sizes of the constituent fibers of a nerve trunk in determining the form of its action potential wave. Am. J. Physiol.-Legacy Content 80, 522–547. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplegacy.1927.80.3.522 (1927).

Duysens, J., Tax, A., Trippel, M. & Dietz, V. Increased amplitude of cutaneous reflexes during human running as compared to standing. Brain Res. 613, 230–238 (1993).

Komiyama, T., Zehr, E. P. & Stein, R. B. Absence of nerve specificity in human cutaneous reflexes during standing. Exp. Brain Res. 133, 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002210000411 (2000).

Zehr, E., Stein, R. & Komiyama, T. Function of sural nerve reflexes during human walking. J. Physiol. 507, 305–314 (1998).

Forssberg, H., Grillner, S. & Rossignol, S. Phase dependent reflex reversal during walking in chronic spinal cats. Brain Res 85, 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(75)91013-6 (1975).

Duysens, J., Trippel, M., Horstmann, G. A. & Dietz, V. Gating and reversal of reflexes in ankle muscles during human walking. Exp. Brain Res. 82, 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00231254 (1990).

De Serres, S. J., Yang, J. F. & Patrick, S. K. Mechanism for reflex reversal during walking in human tibialis anterior muscle revealed by single motor unit recording. J. Physiol. 488(Pt 1), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020963 (1995).

Yam, M. F. et al. General pathways of pain sensation and the major neurotransmitters involved in pain regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19082164 (2018).

Sandrini, G. et al. The lower limb flexion reflex in humans. Prog. Neurobiol. 77, 353–395 (2005).

Willer, J. Nociceptive flexion reflexes as a tool for pain research in man. Adv. Neurol. 39, 809–827 (1983).

Kugelberg, E., Eklund, K. & Grimby, L. An electromyographic study of the nociceptive reflexes of the lower limb. Mech. Plantar Respons. Brain 83, 394–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/83.3.394 (1960).

Wiesenfeld-Hallin, Z., Hallin, R. G. & Persson, A. Do large diameter cutaneous afferents have a role in the transmission of nociceptive messages?. Brain Res 311, 375–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(84)90104-5 (1984).

Schomburg, E. D., Steffens, H. & Mense, S. Contribution of TTX-resistant C-fibres and Adelta-fibres to nociceptive flexor-reflex and non-flexor-reflex pathways in cats. Neurosci. Res. 37, 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00129-2 (2000).

Knikou, M., Angeli, C. A., Ferreira, C. K. & Harkema, S. J. Flexion reflex modulation during stepping in human spinal cord injury. Exp. Brain Res. 196, 341–351 (2009).

Jones, C. A. & Yang, J. F. Reflex behavior during walking in incomplete spinal-cord-injured subjects. Exp. Neurol. 128, 239–248 (1994).

Thompson, A. K., Mrachacz-Kersting, N., Sinkjær, T. & Andersen, J. Modulation of soleus stretch reflexes during walking in people with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury. Exp. Brain Res. 237, 2461–2479 (2019).

Morita, H., Crone, C., Christenhuis, D., Petersen, N. & Nielsen, J. Modulation of presynaptic inhibition and disynaptic reciprocal Ia inhibition during voluntary movement in spasticity. Brain 124, 826–837 (2001).

Knikou, M. & Mummidisetty, C. K. Reduced reciprocal inhibition during assisted stepping in human spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 231, 104–112 (2011).

Perez, M. A. & Field-Fote, E. C. Impaired posture-dependent modulation of disynaptic reciprocal Ia inhibition in individuals with incomplete spinal cord injury. Neurosci. Lett. 341, 225–228 (2003).

Downes, L., Ashby, P. & Bugaresti, J. Reflex effects from Golgi tendon organ (Ib) afferents are unchanged after spinal cord lesions in humans. Neurology 45, 1720–1724. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.45.9.1720 (1995).

Kim, H. E., Corcos, D. M. & Hornby, T. G. Increased spinal reflex excitability is associated with enhanced central activation during voluntary lengthening contractions in human spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 114, 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.01074.2014 (2015).

Nakazawa, K., Kawashima, N. & Akai, M. Enhanced stretch reflex excitability of the soleus muscle in persons with incomplete rather than complete chronic spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 87, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2005.08.122 (2006).

Thompson, A. K. & Wolpaw, J. R. Restoring walking after spinal cord injury: Operant conditioning of spinal reflexes can help. Neuroscientist 21, 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858414527541 (2015).

Thompson, A. K. & Wolpaw, J. R. H-reflex conditioning during locomotion in people with spinal cord injury. J. Physiol. 599, 2453–2469 (2021).

Thompson, A. K., Pomerantz, F. R. & Wolpaw, J. R. Operant conditioning of a spinal reflex can improve locomotion after spinal cord injury in humans. J. Neurosci. 33, 2365–2375 (2013).

Adams, M. M. & Hicks, A. L. Spasticity after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 43, 577–586. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101757 (2005).

Skold, C., Levi, R. & Seiger, A. Spasticity after traumatic spinal cord injury: nature, severity, and location. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 80, 1548–1557 (1999).

Maynard, F. M., Karunas, R. S. & Waring, W. P. 3rd. Epidemiology of spasticity following traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 71, 566–569 (1990).

Kim, H. Y. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of neuropathic pain in patients with spinal cord injury referred to a rehabilitation center. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 44, 438–449. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.20081 (2020).

Finnerup, N. B., Johannesen, I. L., Sindrup, S. H., Bach, F. W. & Jensen, T. S. Pain and dysesthesia in patients with spinal cord injury: A postal survey. Spinal Cord 39, 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101161 (2001).

Burke, D., Fullen, B. M., Stokes, D. & Lennon, O. Neuropathic pain prevalence following spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pain 21, 29–44 (2017).

Kennedy, P., Lude, P. & Taylor, N. Quality of life, social participation, appraisals and coping post spinal cord injury: A review of four community samples. Spinal cord 44, 95–105 (2006).

Widerström-Noga, E. G., Felipe-Cuervo, E., Broton, J. G., Duncan, R. C. & Yezierski, R. P. Perceived difficulty in dealing with consequences of spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 80, 580–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90203-4 (1999).

Nees, T. A., Finnerup, N. B., Blesch, A. & Weidner, N. Neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury: the impact of sensorimotor activity. Pain 158, 371–376 (2017).

Hulsebosch, C. E. in Spinal Cord Injury Pain 45–86 (Elsevier, 2022).

Hulsebosch, C. E., Hains, B. C., Crown, E. D. & Carlton, S. M. Mechanisms of chronic central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Brain Res. Rev. 60, 202–213 (2009).

Drew, G. M., Siddall, P. J. & Duggan, A. W. Mechanical allodynia following contusion injury of the rat spinal cord is associated with loss of GABAergic inhibition in the dorsal horn. Pain 109, 379–388 (2004).

Weaver, L., Cassam, A., Krassioukov, A. & Llewellyn-Smith, I. Changes in immunoreactivity for growth associated protein-43 suggest reorganization of synapses on spinal sympathetic neurons after cord transection. Neuroscience 81, 535–551 (1997).

Polistina, D. C., Murray, M. & Goldberger, M. E. Plasticity of dorsal root and descending serotoninergic projections after partial deafferentation of the adult rat spinal cord. J. Comparat. Neurol. 299, 349–363. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.902990307 (1990).

Ondarza, A. B., Ye, Z. & Hulsebosch, C. E. Direct evidence of primary afferent sprouting in distant segments following spinal cord injury in the rat: colocalization of GAP-43 and CGRP. Exp. Neurol. 184, 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.07.002 (2003).

Murray, M. Axonal sprouting in response to dorsal rhizotomy. Spinal Cord Reconstruction, 445–453 (1983).

Goldberger, M. E. & Murray, M. Patterns of sprouting and implications for recovery of function. Adv. Neurol. 47, 361–385 (1988).

Christensen, M. D. & Hulsebosch, C. E. Spinal cord injury and anti-NGF treatment results in changes in CGRP density and distribution in the dorsal horn in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 147, 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1006/exnr.1997.6608 (1997).

Latremoliere, A. & Woolf, C. J. Central sensitization: A generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J. Pain 10, 895–926 (2009).

Handwerker, H. O., Anton, F., Kocher, L. & Reeh, P. W. Nociceptor functions in intact skin and in neurogenic or non-neurogenic inflammation. Acta Physiol. Hung. 69, 333–342 (1987).

Handwerker, H. O. Electrophysiological mechanisms in inflammatory pain. Agents Actions Suppl 32, 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-0348-7405-2_12 (1991).

Bennett, D. L., Clark, A. J., Huang, J., Waxman, S. G. & Dib-Hajj, S. D. The role of voltage-gated sodium channels in pain signaling. Physiol. Rev. 99, 1079–1151. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00052.2017 (2019).

Andersen, O. K., Finnerup, N. B., Spaich, E. G., Jensen, T. S. & Arendt-Nielsen, L. Expansion of nociceptive withdrawal reflex receptive fields in spinal cord injured humans. Clin. Neurophysiol. 115, 2798–2810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2004.07.003 (2004).

Schmit, B. D., Hornby, T. G., Tysseling-Mattiace, V. M. & Benz, E. N. Absence of local sign withdrawal in chronic human spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol 90, 3232–3241. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00924.2002 (2003).

Melzack, R. & Wall, P. D. pain mechanisms: A new theory: a gate control system modulates sensory input from the skin before it evokes pain perception and response. Science 150, 971–979 (1965).

Zehr, E. P. Training-induced adaptive plasticity in human somatosensory reflex pathways. J. Appl. Physiol. 101, 1783–1794 (2006).

Nakajima, T., Mezzarane, R. A., Hundza, S. R., Komiyama, T. & Zehr, E. P. Convergence in reflex pathways from multiple cutaneous nerves innervating the foot depends upon the number of rhythmically active limbs during locomotion. PLoS ONE 9, e104910. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104910 (2014).

Misiaszek, J. E. The H-reflex as a tool in neurophysiology: Its limitations and uses in understanding nervous system function. Muscle Nerve 28, 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.10372 (2003).

Stein, R. B. & Thompson, A. K. Muscle reflexes in motion: how, what, and why?. Exerc. Sport. Sci. Rev. 34, 145–153 (2006).

Schieppati, M. The Hoffmann reflex: A means of assessing spinal reflex excitability and its descending control in man. Prog. Neurobiol. 28, 345–376 (1987).

Van Wezel, B. M., Ottenhoff, F. A. & Duysens, J. Dynamic control of location-specific information in tactile cutaneous reflexes from the foot during human walking. J. Neurosci. 17, 3804–3814 (1997).

Zehr, E., Komiyama, T. & Stein, R. Cutaneous reflexes during human gait: electromyographic and kinematic responses to electrical stimulation. J. Neurophysiol. 77, 3311–3325 (1997).

Zehr, E. P. & Stein, R. B. What functions do reflexes serve during human locomotion?. Prog. Neurobiol. 58, 185–205 (1999).

Zehr, E. P., Fujita, K. & Stein, R. B. Reflexes from the superficial peroneal nerve during walking in stroke subjects. J. Neurophysiol. 79, 848–858. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.848 (1998).

Burke, D., Dickson, H. G. & Skuse, N. F. Task-dependent changes in the responses to low-threshold cutaneous afferent volleys in the human lower limb. J. Physiol. 432, 445–458 (1991).

Yang, J. F. & Stein, R. B. Phase-dependent reflex reversal in human leg muscles during walking. J. Neurophysiol. 63, 1109–1117. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1990.63.5.1109 (1990).

Madsen, L. P., Kitano, K., Koceja, D. M., Zehr, E. P. & Docherty, C. L. Effects of chronic ankle instability on cutaneous reflex modulation during walking. Exp. Brain Res. 237, 1959–1971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-019-05565-4 (2019).

Zehr, E. P. & Loadman, P. M. Persistence of locomotor-related interlimb reflex networks during walking after stroke. Clin. Neurophysiol. 123, 796–807 (2012).

Brooke, J. D., McIlroy, W. E., Staines, W. R., Angerilli, P. A. & Peritore, G. F. Cutaneous reflexes of the human leg during passive movement. J. Physiol. 518, 619–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0619p.x (1999).

Zehr, E. P. & Duysens, J. Regulation of arm and leg movement during human locomotion. Neuroscientist 10, 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858404264680 (2004).

Hultborn, H. Changes in neuronal properties and spinal reflexes during development of spasticity following spinal cord lesions and stroke: studies in animal models and patients. J. Rehabil. Med., 46–55 (2003).

Wallace, D. M., Ross, B. H. & Thomas, C. K. Motor unit behavior during clonus. J. Appl. Physiol. 99, 2166–2172. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00649.2005 (2005).

Gorassini, M. A., Knash, M. E., Harvey, P. J., Bennett, D. J. & Yang, J. F. Role of motoneurons in the generation of muscle spasms after spinal cord injury. Brain 127, 2247–2258. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh243 (2004).

Drew, G. M., Siddall, P. J. & Duggan, A. W. Responses of spinal neurones to cutaneous and dorsal root stimuli in rats with mechanical allodynia after contusive spinal cord injury. Brain Res 893, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03288-1 (2001).

Lundberg, A. Multisensory control of spinal reflex pathways. Prog. Brain Res. 50, 11–28 (1979).

Hendry, S. & Hsiao, S. in Fundamental Neuroscience (Fourth Edition) (eds Larry R. Squire et al.) 531–551 (Academic Press, 2013).

Hultborn, H. Spinal reflexes, mechanisms and concepts: From Eccles to Lundberg and beyond. Prog. Neurobiol. 78, 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.04.001 (2006).

Hultborn, H. Convergence on internneurons in the recirprocal Ia inhibitory pathway to motorneurones. Acta Physiol. Scand. 85, 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05298.x (1972).

Jankowska, E. & McCrea, D. Shared reflex pathways from Ib tendon organ afferents and Ia muscle spindle afferents in the cat. J. Physiol. 338, 99–111 (1983).

Jankowska, E. & Edgley, S. A. Functional subdivision of feline spinal interneurons in reflex pathways from group Ib and II muscle afferents: An update. Eur. J. Neurosci. 32, 881–893 (2010).

Jankowska, E. Interneuronal relay in spinal pathways from proprioceptors. Prog. Neurobiol. 38, 335–378 (1992).

Brink, E., Jankowska, E., McCrea, D. & Skoog, B. Inhibitory interactions between interneurones in reflex pathways from group Ia and group Ib afferents in the cat. J. Physiol. 343, 361–373 (1983).

Brooke, J. et al. Sensori-sensory afferent conditioning with leg movement: gain control in spinal reflex and ascending paths. Prog. Neurobiol. 51, 393–421 (1997).

Hornby, T. G., Rymer, W. Z., Benz, E. N. & Schmit, B. D. Windup of flexion reflexes in chronic human spinal cord injury: A marker for neuronal plateau potentials?. J. Neurophysiol. 89, 416–426. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00979.2001 (2003).

Tsuda, M., Koga, K., Chen, T. & Zhuo, M. Neuronal and microglial mechanisms for neuropathic pain in the spinal dorsal horn and anterior cingulate cortex. J. Neurochem. 141, 486–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.14001 (2017).

Meisner, J. G., Marsh, A. D. & Marsh, D. R. Loss of GABAergic interneurons in laminae I-III of the spinal cord dorsal horn contributes to reduced GABAergic tone and neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 27, 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2009.1166 (2010).

Gwak, Y. S., Crown, E. D., Unabia, G. C. & Hulsebosch, C. E. Propentofylline attenuates allodynia, glial activation and modulates GABAergic tone after spinal cord injury in the rat. Pain 138, 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.021 (2008).

Krenz, N. R. & Weaver, L. C. Sprouting of primary afferent fibers after spinal cord transection in the rat. Neuroscience 85, 443–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00622-2 (1998).

Goldberger, M., Murray, M. & Tessler, A. in Neuroregeneration 241–264 (Raven Press New York, 1993).

Carlton, S. M. et al. Peripheral and central sensitization in remote spinal cord regions contribute to central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Pain 147, 265–276 (2009).

Mendell, L. M. Physiological properties of unmyelinated fiber projection to the spinal cord. Exp. Neurol. 16, 316–332 (1966).

Woolf, C. J. & King, A. E. Physiology and morphology of multireceptive neurons with C-afferent fiber inputs in the deep dorsal horn of the rat lumbar spinal cord. J. Neurophysiol. 58, 460–479 (1987).

Guan, Y., Borzan, J., Meyer, R. A. & Raja, S. N. Windup in dorsal horn neurons is modulated by endogenous spinal μ-opioid mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 26, 4298–4307 (2006).

Yang, F. et al. Electrical stimulation of dorsal root entry zone attenuates wide-dynamic-range neuronal activity in rats. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 18, 33–40 (2015).

Maixner, W., Dubner, R., Bushnell, M. C., Kenshalo, D. R. Jr. & Oliveras, J.-L. Wide-dynamic-range dorsal horn neurons participate in the encoding process by which monkeys perceive the intensity of noxious heat stimuli. Brain Res. 374, 385–388 (1986).

Rosner, J. et al. Central neuropathic pain. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 9, 73. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-023-00484-9 (2023).

Fernandes, E. C. et al. Diverse firing properties and Aβ-, Aδ-, and C-afferent inputs of small local circuit neurons in spinal lamina I. Pain 157, 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000394 (2016).

Daniele, C. A. & MacDermott, A. B. Low-threshold primary afferent drive onto GABAergic interneurons in the superficial dorsal horn of the mouse. J. Neurosci. 29, 686–695 (2009).

Guo, D. & Hu, J. Spinal presynaptic inhibition in pain control. Neuroscience 283, 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.032 (2014).

Meunier, S., Russmann, H., Simonetta-Moreau, M. & Hallett, M. Changes in spinal excitability after PAS. J. Neurophysiol 97, 3131–3135 (2007).

Knikou, M., Angeli, C. A., Ferreira, C. K. & Harkema, S. J. Soleus H-reflex gain, threshold, and amplitude as function of body posture and load in spinal cord intact and injured subjects. Int J Neurosci 119, 2056–2073 (2009).

Thompson, A. K., Chen, X. Y. & Wolpaw, J. R. Soleus H-reflex operant conditioning changes the H-reflex recruitment curve. Muscle Nerve 47, 539–544. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.23620 (2013).

Komiyama, T., Kawai, K. & Fumoto, M. The excitability of a motoneuron pool assessed by the H-reflex method is correlated with the susceptibility of Ia terminals to repetitive discharges in humans. Brain Res 826, 317–320 (1999).

Rice, D. et al. Exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free and chronic pain populations: state of the art and future directions. J Pain 20, 1249–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.03.005 (2019).

Willer, J. C. Comparative study of perceived pain and nociceptive flexion reflex in man. Pain 3, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(77)90036-7 (1977).

Linde, L. D. et al. The nociceptive flexion reflex: A scoping review and proposed standardized methodology for acquisition in those affected by chronic pain. Br J Pain 15, 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463720913289 (2021).

Savic, G. et al. Perceptual threshold to cutaneous electrical stimulation in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 44, 560–566. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101921 (2006).

Makihara, Y., Segal, R. L., Wolpaw, J. R. & Thompson, A. K. H-reflex modulation in the human medial and lateral gastrocnemii during standing and walking. Muscle Nerve 45, 116–125 (2012).

Makihara, Y., Segal, R. L., Wolpaw, J. R. & Thompson, A. K. Operant conditioning of the soleus H-reflex does not induce long-term changes in the gastrocnemius H-reflexes and does not disturb normal locomotion in humans. J. Neurophysiol. 112, 1439–1446 (2014).

Damewood, B. A. P., Sinkjær, T. & Thompson, A. K. Generation and modification of human locomotor EMG activity when walking faster and carrying additional weight. Exp. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1113/ep092063 (2025).

Seif, G., Phipps, A. M., Donnelly, J. M., Dellenbach, B. H. S. & Thompson, A. K. Neurophysiological effects of latent trigger point dry needling on spinal reflexes. J. Neurophysiol. 133, 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00366.2024 (2025).

Kido, A., Tanaka, N. & Stein, R. B. Spinal excitation and inhibition decrease as humans age. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 82, 238–248 (2004).

Mücke, M. et al. Quantitative sensory testing (QST) English version. Schmerz 35, 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00482-015-0093-2 (2021).

Baken, B. C. M., Dietz, V. & Duysens, J. Phase-dependent modulation of short latency cutaneous reflexes during walking in man. Brain Res. 1031, 268–275 (2005).

Zehr, E. P., Hesketh, K. L. & Chua, R. Differential regulation of cutaneous and H-reflexes during leg cycling in humans. J. Neurophysiol. 85, 1178–1184 (2001).

Madsen, L. P., Kitano, K., Koceja, D. M., Zehr, E. P. & Docherty, C. L. Modulation of cutaneous reflexes during sidestepping in adult humans. Exp. Brain Res. 238, 2229–2243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-020-05877-w (2020).

Heckman, C. J., Johnson, M., Mottram, C. & Schuster, J. Persistent inward currents in spinal motoneurons and their influence on human motoneuron firing patterns. Neuroscientist 14(264–275), 1073858408314986 (2008).

Heckmann, C. J., Gorassini, M. A. & Bennett, D. J. Persistent inward currents in motoneuron dendrites: Implications for motor output. Muscle Nerve 31, 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.20261 (2005).

Li, Y., Li, X., Harvey, P. J. & Bennett, D. J. Effects of baclofen on spinal reflexes and persistent inward currents in motoneurons of chronic spinal rats with spasticity. J. Neurophysiol 92, 2694–2703 (2004).

Li, Y. & Bennett, D. J. Persistent sodium and calcium currents cause plateau potentials in motoneurons of chronic spinal rats. J. Neurophysiol 90, 857–869 (2003).

Lee, R. H. & Heckman, C. J. Enhancement of bistability in spinal motoneurons in vivo by the noradrenergic alpha1 agonist methoxamine. J. Neurophysiol 81, 2164–2174. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2164 (1999).

Duysens, J., Tax, A. A., Trippel, M. & Dietz, V. Phase-dependent reversal of reflexly induced movements during human gait. Exp. Brain Res. 90, 404–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00227255 (1992).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Blair H.S. Dellenbach (MSOT) for assisting in participant recruitment and screening and Dr. Krista Fjeld and Mr. Roland Cote for their assistance during data collection.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs endorsed by the Department of Defense through the Spinal Cord Injury Research Program (W81XWH-22–1-1099), the Doscher Neurorehabilitation Program (Thompson), NIH NINDS R01NS114279 (Thompson).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.P. and A.K.T. conceived and designed the study, performed experiments, analyzed data, and interpreted results. A.M.P. prepared figures and drafted manuscript. A.M.P. and A.K.T. edited and finalized the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions