Abstract

Data on the efficacy of computer tomography guided brachytherapy (CT-BRT) for limited liver metastases is lacking; to assess CT-BRT’s role in inducedoligoprogression in colorectal cancer (CRC), we performed a retrospective cohort study on CRC patients with metastatic disease, treated with 2–5 lines of systemic therapy, who achieved induced oligoprogression with up to four liver metastases eligible for CTBRT. In 75 patients, median overall survival (mOS) was 17 months, and median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 10 months during a 16-month follow-up. The mOS was not dose-dependent. Complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD) were found in 8, 31, 47, and 15%, respectively. The mOS in patients with CR, PR, SD, and PD was 23, 17, 14, and 11 months, respectively. Disease Control Rate (DCR) with a high dose influenced OS, while PFS was impacted by extrahepatic metastases (especially in abdominal/pelvic lymph nodes), the number of metastases, and DCR with a high dose. Treatment toxicity was very low (Grade 3—1%, > Grade 3–0%). We report the largest cohort demonstrating CT-BRT as an effective local treatment for colorectal liver metastases in induced oligoprogression, with minimal toxicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, with metastases occurring synchronously in 15–30% of cases. Metachronous metastases develop in 20–50% of patients with locally advanced cancer. About half of colorectal cancer metastases are located in the liver. In the case of oligometastatic disease, local treatment, mainly surgery, allows potential cure in up to 20–40% of patients1,2. Non-surgical techniques are also available, including thermal methods such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and laser-induced thermotherapy; transarterial procedures like chemoembolization (TACE) and Y-90 radioembolization (RE); and various radiotherapy modalities, with stereotactic radiotherapy and high-dose-rate (HDR) brachytherapy (BRT) being the most prominent3. Non-surgical methods dominate in the later stages of the disease, such as oligorecurrence, oligoprogression, and oligopersistent disease oligometastatic4. This approach enables the continuation of the current line of systemic therapy or delays the initiation of the subsequent line. While the local treatment recommendations for post-treatment in oligometastatic disease are well-defined, the local treatment for oligoprogression disease is not.

HDR-BRT under continuous fluoroscopic computer tomography (CT-BRT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) presents a compelling non-surgical option for liver metastases, offering precise, high-dose targeting with minimal exposure to surrounding organs due to its rapid dose fall-off. At the same time, CT- and MRI-guided imaging has reduced surgical complications and increased treatment precision. These features make brachytherapy well-suited for treating oligo-recurrent, oligoprogressive, and oligopersistent disease. However, there is a lack of extensive studies evaluating the results of treatment with CT-BRT of patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases at the oligoprogression disease.

Herein, we present the largest reported cohort study of patients with CRC liver metastases treated with HDR CT-guided brachytherapy for induced oligoprogression (iOPD), defined by EORTC/ESTRO recommendations5,6.

Material and methods

We retrospectively reviewed patients treated in the first author’s tertiary brachytherapy department between 2015 and 2022. Liver metastases were confirmed in all patients through abdominal imaging (CT or MRI) and/or histopathology. At the localized disease stage, patients were treated according to the then-current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, including tumor resection with lymph node dissection, possible liver metastasectomy, and, as indicated, preoperative radiochemotherapy or adjuvant chemotherapy. Predictors of systemic treatment included mutation status of the KRAS and BRAF genes, DNA microsatellite instability (MSI), guiding further treatment. In the first line, regimens based on fluoropyrimidine derivatives with oxaliplatin or irinotecan with an EGFR (KRAS mutation wild type) or VEGFR (KRAS gene mutated type) inhibitor were used. A fluoropyrimidine-based regimen with oxaliplatin (if irinotecan was used in line 1) or with irinotecan (if oxaliplatin was used in line 1) with an anti-VEGFR drug was also used in line 2). Trifluridine/typiracil, regorafenib were used in line 3. When microsatellite instability-high MSI-H or mismatch repair deficit (dMMR) was confirmed, patients were eligible for pembrolizumab immunotherapy. Patients received active anticancer treatment both before and after brachytherapy. Treatment aimed to maintain the current line of systemic therapy.

The inclusion criteria for patients undergoing brachytherapy were: metastatic CRC with up to five progressing and/or new liver metastases during systemic treatmentWorld Health Organization (WHO) performance status below 3, tumor diameter under 10 cm, technical feasibility for application (no immediate proximity to large vessels), creatinine level below 2 mg/dl, hemoglobin (HGB) above 8 mg/dl, white blood cell count (WBC) above 2000/mm3, neutrophils (NEU) above 1500/mm3, platelet count (PLT) above 50,000/mm3, international normalized ratio (INR) below 1.5, and alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and total bilirubin (BIL) levels less than 2.5 times the upper limit of normal. The exclusion criteria included tumor location preventing applicator placement, inflammatory conditions within the abdominal cavity, and proximity to critical structures that would hinder achieving the planned dose.

The applicator placement procedure occurred in an operating theatre equipped with a CT sliding gantry and HDR machine. General complex or local anesthesia with sedation was used. Varian (USA) needle applicators of 200 or 320 mm length were used for application. The procedure was performed under continuous fluoroscopic CT imaging guidance after locating the metastasis on diagnostic CT with contrast after fusion with other imaging studies (prior CT, MRI, or Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT)). Once the applicators were in place, CT was performed for treatment planning. The number of applicators depended on the size of the metastasis and its shape. Applicators were placed no more than 2 cm apart and 1 cm from the tumour surface, parallel to each other. During one fraction, 1 metastasis was irradiated most often, less often 2 metastases. This was due to the duration of the procedure and the possibility of administering a limited amount of iodine contrast during one procedure. If it was necessary to irradiate further metastases, the next procedure was performed within 2 weeks. Clinical target volume (CTV) was equal to gross tumor volume (GTV) and represented the tumor visible on CT after fusion with previous imaging studies. Critical organs were the liver and, depending on the location of the lesion, the kidney, stomach, gallbladder, bowel, or heart. Depending on the size of the metastasis, location, and proximity to critical structures, three dose regiments (15, 20, 25 Gy) were used. The dose depended on the size of the tumour and dose constraints from critical organs. The condition of the patient and the condition of the liver after successive lines of systemic treatment were also taken into account. In the first years of the method, lower doses (15–20 Gy) were used due to the lack of available data in the literature on toxicity; in recent years, higher doses (20–25 Gy) have been used. Treatment planning was performed in the Brachyvision ver. 11. treatment planning system (Varian USA). A 24-channel Gammamed remote source loading device (Varian USA) equipped with an Ir192 source with an average activity of 10 Ci and a diameter of 0.6 mm was used for treatment. Our application method was also described in our previous work7,8,9.

Three dose levels of 15, 20, and 25 Gy were used. Treatment was carried out in one fraction. Dose selection depended on proximity and dose to critical structures. The planning goal was to achieve D95% above the planned fractional dose. The main critical organ was the liver (D tolerance = D2/3 < 5 Gy), as well as the stomach (D tolerance = D1cm3 < 15 Gy), gall bladder (D tolerance = D1max < 20 Gy), intestines (D tolerance = D1cm3 < 12 Gy), kidney (V7Gy < 2/3 volume) (Fig. 1).

Isodose distribution on transverse, sagittal, and frontal scans and 3D mapping of abdominal structures with target and organs at risk. Schematic illustration created by the authors using Microsoft Paint ver. 11 (Windows) and Microsoft Word (Office 365). Software information available at: https://www.microsoft.com/pl-pl/windows/paint and https://www.microsoft.com/pl-pl/microsoft-365/word.

The BED varied according to the dose used and the alpha/beta factor adopted. For alpha/beta 3, characteristic of late radiation reactions, it was at 15, 20 and 25 Gy of 90, 153 and 233 Gy, respectively, while for alpha/beta 10, characteristic of tumour response and early radiation reactions, it was 37.5, 60 and 87.5, respectively. Literature data indicate an alpha beta ratio for colorectal cancer of 5. In this case, the BED for doses of 15, 20 and 25 Gy were 60, 100 and 150 Gy, respectively.

Treatment planning was performed in the Brachyvision ver. 10–12 treatment planning system (Varian USA). The treatment used a 24-channel device for remote charging of Gammamed sources (Varian USA) equipped with an Ir192 source with an average activity of 10 Ci and a diameter of 0.6 mm. No other local treatment modalities such as SBRT or surgical interventions were applied following HDR brachytherapy.

Follow-up consisted of CT and/or MR abdominal scans at 3-month intervals. To avoid pseudoprogression, assessment during the second imaging treatment after brachytherapy was crucial. In case of disease progression relative to the previous examination and the examination on the day of brachytherapy, progression at the first imaging examination was considered. The response was assessed using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 criteria. The study endpoints were overall survival (OS), defined from brachytherapy to death, and progression free survival (PFS), defined as survival free of tumor progression (at any site, including outside the treated area) and local control defined as survival free of tumor progression of treated metastases. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Cox proportional regression analysis was used to analyze prognostic factors for LC, PFS and OS. A p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Statistical analysis was performed using R v 4.2.0 Lucent Technologies USA software. The Bioethics Committee at the Regional Medical Chamber in Lublin approved the study (No. LIL-KB-20/2014). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Specifically, this study followed the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines10.

Results

Of the 270 patients treated with CT-BRT for liver metastases, 75 patients met the inclusion criteria for the study. The complete characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

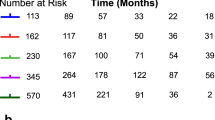

The median follow-up time was 16 months (4–36). The median PFS (mPFS) was 10 months. The 6 m-, 12 m-, and 24 m-PFS were 84%, 45%, and 2%, respectively. The median OS (mOS) was 17 months. The 6 m-, 12 m-, and 24 m-OS were 100%, 69%, and 25%, respectively (Fig. 2).

A-The Overall Survival (OS) and B-The Progression Free Survival (PFS) in the whole patient cohort. Screenshot exported from the Brachytherapy Planning System – Brachyvision version 12 (Varian Medical Systems, USA).Product information available at: https://www.varian.com/products/brachytherapy/treatment-planning/brachyvision.

The median local control of treated metastases was 14 months. The 6 m-, 12 m- and 24 m was 95%, 66% and 9% respectively. The impact of selected clinical and treatment-related parameters on local control, progression-free survival, and overall survival is summarized in Table 2.

There were no statistically significant differences between patients receiving doses of 15, 20 and 25 Gy. The data are shown in the table. However, patients who received higher dose ranges (20, 25 Gy) had longer LC and PFS than patients who received a lower dose (15 Gy) (Table 3).

Extrahepatic metastases had no significant impact on overall survival, though results approached significance. In contrast, significant statistical differences were found regarding PFS between patients with liver-only and non-liver metastases (Table 3).

Additional lung metastases did not affect OS and PFS. The presence of additional metastases to the abdominal or pelvic lymph nodes had a borderline effect on OS. Additional lymph node metastases significantly affected PFS. The data are shown in the Table 3.

The number of liver metastases had a borderline significance on OS and significantly affected PFS. There were no significal difference on LC (Table 3).

As mentioned, treatment was administered during consecutive lines of systemic therapy from 2 to 5. Due to the very few patients treated in lines 2 and 5, patients from lines 2 and 3 were included in the group with up to 3 line. Patients from lines 4 and 5 were included in the group above line 3. There were no significant differences in either OS, PFS or LC. between both groups.

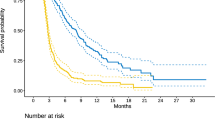

In our cohort, a Complete Response (CR) was found in 6 patients (8%), a Partial Response (PR) in 23 patients (31%), Stable Disease (SD) in 35 patients (47%) and Progressive Disease (PD) in 11 patients (15%). The objective response rate (ORR) was 39% (29pt), while the Disease Control Rate (DCR) was 85% (64 patients). The mOS in the CR, PR, SD, and PD groups was 23, 17, 14, and 11 months, respectively. The 6-m, 12-m, and 24-m OS was 100%, 100%, and 33% in the CR, 100, 70, and 26% in the PR, 100, 54, and 14% in the SD, and 90%, 45% and 0% in the PD group, respectively (Fig. 3).

DCR with a 25 Gy dose significantly affected OS (p = 0.015) and PFS (p < 0.001). Table 4 present median values, while Fig. 4 show survival curves.

According to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 only one patient (1%) had a grade (G) 3 toxicity, bleeding into the peritoneal cavity. The G1/2 toxicities were predominantly pain at the injection site in 12 patients (16%), transient elevation of ALT and/or AST and/or total bilirubin up to 2 weeks after treatment, and limited hematoma under the liver capsule, which did not require any treatment in 6 patients (8%).

Discussion

Oligoprogression is a local progression of one or more metastatic lesions with an overall response to treatment11. In the work of Guckenberger et al.6, the authors identify oligometastatic disease as an intermediate stage between locally advanced and metastatic disease and have distinguished nine clinical situations in of oligometastatic disease. Among these, they distinguished induced oligoprogression, in which isolated progression and limited metastases occur in the case of primary oligometastatic disease. In this study, advanced CRC patients mainly on 3rd and 4th line systemic therapy achieved disease control, though some metastases showed oligoprogression. Systemic advances enable long-term control, while local treatments help sustain therapy and delay progression12. Most of the data regarding the use of radiotherapy are based on the use of stereotactic radiotherapy. Unfortunately, data showing prolonged OS in this patient group is scarce13. The largest study, including different locations of extracranial metastases14,15,16, found a difference in mOS between groups with irradiated dominant lesion, oligoprogression, and oligometastatic disease in favor of patients with oligometastatic disease compared to oligoprogression and dominant lesion, indicating some role of local treatment in OS depending on the stage of metastatic disease. Furthermore, the mOS in these studies is comparable to historical survival data in patients undergoing resection of metastases17,18.

The effect of radiotherapy on local control has been well documented, but again, it is only for stereotactic radiotherapy. In a study by Rusthoven et al.19 of SBRT (3 fractions, 36–60 Gy in 63 metastatic liver lesions), LC rates of 95% at 1 year and 92% at 2 years were reported, with no cases of radiation-induced liver disease (RILD). Van der Pool et al.20 reported 100% control after 1 year and 74% after 2 years using 30–37.5 Gy in three fractions in 20 patients. On the other hand, a study by Lee et al.21 reported 1-year LC in only 71% of 68 metastatic liver lesions. However, a limitation of this study was the large size of the lesions (median volume 75.9 ml; range, 1.2 to 3,090 ml)21. According to the systematic review, the local tumor control rate for SBRT ranges from 47 to 96%, with pooled 1- and 2-year local control estimates of 67 and 59.3%, respectively, while for RFA in the treatment of CRC liver metastasis, the local tumor control rate ranges from 47 to 96%22,23. Direct comparison of these methods is challenging due to differences in the stage of disease at which metastatic lesions were treated and variations in their characteristics, such as location and size.

Data on the use of brachytherapy in treating liver metastases are relatively abundant3. However, most studies involve metastatic patients with mixed histology24. Few studies concern liver metastases of colorectal cancer only25,26. In these papers, the authors highlighted the high local efficacy similar to radiofrequency ablation and the strong dose dependence of local control and tumor size. Similar dose-related data were shown in the current study. Studies comparing different RT techniques, including brachytherapy, show a benefit of brachytherapy in terms of dosimetric analysis7. Of course, the disadvantage remains the procedure’s invasiveness, but the complication rate in the current study is low.

The use of brachytherapy in oligometastatic disease in various tumors was evaluated in a study by Walter et al.27. In this study, individual groups of patients with different types of oligoprogression were not separated, and the group of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer totaled 54 patients. This study showed significantly worse local control results for CRC than other histological types.

Analysis of prognostic factors showed that patients with high doses and good disease control at 6 months after brachytherapy had the greatest benefit. Patients with metastatic disease outside the liver, primarily the abdomen or pelvis, had a worse prognosis than those with disease confined to the liver. The prognosis also worsened with the number of metastases. Patients who received a dose higher than 20 Gy had a better prognosis in terms of local control and progression-free time, and patients who received 25 Gy and additionally achieved at least disease stabilisation as the best response to treatment also had a better prognosis in terms of overall survival. These analyses confirm previous data on the use of brachytherapy3. The effect of dose was also confirmed in previous publications27.

No randomized trials are demonstrating the role of brachytherapy in oligometastatic disease for CRC metastases to the liver. Most patients in the group analyzed were treated with 3rd- or 4th-line therapy for metastatic CRC. The drugs used were regorafenib, cetuximab, panitumumab in lines 3, and typiracil trifluridine in lines 3 and 4. Data from the 3rd line treatment in a retrospective analysis of a real-world study28 show a median OS for chemotherapy and anti-EGFR therapy of 12–14.5 months, depending on the treatment used, and a median PFS of 3–4.9 months, depending on the regimen used. Data from the use of typiracil trifluridine in fourth-line treatment from the RECOURCE trial29 show a median OS of 7.1 months and a median PFS of 2 months. Other regimens yielded PFS of 1.9 to 5.6 m and OS of 6.4 to 10.8m30. The use of brachytherapy in the analyzed group of patients, despite the significant predominance of patients on line 3 treatment, allowed a mOS of 17 months and a mPFS of 10 months. These data do not allow a direct comparison but indicate a possible benefit of local brachytherapy treatment. Also, the DCR in the analyzed group of patients was higher than with 3rd-line systemic treatment, at 85% compared to 57.1–61.3% with systemic treatment alone. However, we must highlight the study’s limitations, such as the lack of randomization, the retrospective evaluation, and the relatively small number of patients.

Treatment toxicity in the analysed group of patients was relatively low. The cited studies indicate a slightly higher complication rate25,26,27. This was due to the strict selection of patients with regard to the location of the metastases, especially the location of large blood vessels. The reason for the lower rate of haemorrhagic complications may also have been the slightly different application technique using thin applicators, as opposed to the use of angiostatic sheets.

Thermal ablation is less effective for hepatic tumors adjacent to large vessels (e.g., portal vein, hepatic veins) or bile ducts due to the heat-sink effect and risk of thermal injury31,32. In contrast, ablative radiotherapy can treat such tumors more safely, but requires caution when lesions are near radiosensitive structures like the stomach, duodenum, small bowel, or in patients with impaired liver function31,32.

The publication has a number of limitations. These are the retrospective nature of the analysis from single oncologic centre and the impact of systemic treatment on the prognosis in this group of patients. A limitation of this study is the relatively short median follow-up time of 16 months, which may affect the accuracy of long-term survival estimates and limits the ability to fully assess late local or distant recurrences.

Conclusions

This study, the largest CT-BRT cohort with a homogeneous group of CRC patients with therapy-induced oligoprogression, highlights CT-BRT as an effective local treatment for CRC liver metastases during systemic therapy, with potential to extend PFS and OS. The current work complements our previous publications on colorectal liver metastases and other cohorts defined by ESTRO/EORTC oligometastatic criteria33,34. Prospective randomized trials are needed to confirm these findings. Key factors affecting outcomes include extrahepatic metastases (particularly in abdominal or pelvic lymph nodes), metastasis count, and RECIST response type, with low treatment toxicity.

Data availability

The data and analyses supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Requests for access will be considered in light of institutional policies and ethical guidelines to ensure appropriate use of the data.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- BIL:

-

Bilirubin

- BRT:

-

Brachytherapy

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTCAE:

-

Common terminology criteria for adverse events

- CTV:

-

Clinical target volume

- CR:

-

Complete response

- DCR:

-

Disease control rate

- dCRT:

-

Definitive chemoradiotherapy

- dMMR:

-

Mismatch repair deficiency

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EORTC:

-

European organisation for research and treatment of cancer

- ESTRO:

-

European society for radiotherapy and oncology

- G:

-

Grade

- Gy:

-

Gray (radiation dose unit)

- GTV:

-

Gross tumor volume

- HDR:

-

High-dose-rate

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- iOPD:

-

Induced oligoprogressive disease

- KRAS:

-

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- LC:

-

Local control

- LVSI:

-

Lymphovascular space invasion

- mOS:

-

Median overall survival

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- mPFS:

-

Median progression-free survival

- MSI:

-

Microsatellite instability

- NCCN:

-

National comprehensive cancer network

- NEU:

-

Neutrophils

- ORR:

-

Objective response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PET-CT:

-

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- PLT:

-

Platelet count

- PR:

-

Partial response

- PFT:

-

Pulmonary function test

- RFA:

-

Radiofrequency ablation

- RECIST:

-

Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- RILD:

-

Radiation-induced liver disease

- SBRT:

-

Stereotactic body radiation therapy

- ST:

-

Systemic therapy

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology

- T:

-

Tumor (in staging context)

- TACE:

-

Transarterial chemoembolization

- VEGFR:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

- WBC:

-

White blood cell count

References

Wong, S. L. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2009 clinical evidence review on radiofrequency ablation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 28, 493–508 (2010).

de Baère, T. et al. Radiofrequency ablation is a valid treatment option for lung metastases: experience in 566 patients with 1037 metastases. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 26, 987–991 (2015).

Karagiannis, E. et al. Narrative review of high-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy in primary or secondary liver tumors. Front. Oncol. 12, 800920 (2022).

Yokoi, R. et al. Optimizing treatment strategy for oligometastases/oligo-recurrence of colorectal cancer. Cancers 16, 142 (2024).

Nevens, D. et al. Completeness of reporting oligometastatic disease characteristics in the literature and influence on oligometastatic disease classification using the ESTRO/EORTC nomenclature. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 114, 587–595 (2022).

Guckenberger, M. et al. Characterisation and classification of oligometastatic disease: a European society for radiotherapy and oncology and European organisation for research and treatment of cancer consensus recommendation. Lancet Oncol. 21, e18–e28 (2020).

Bilski, M. et al. HDR brachytherapy versus robotic-based and linac-based stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy in the treatment of liver metastases - A dosimetric comparison study of three radioablative techniques. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 48, 100815 (2024).

Cisek, P. et al. Biochemical liver function markers after CT-guided brachytherapy for liver metastases. Age 12, 75 (2017).

Bilski, M. E. et al. Radiotherapy as a metastasis directed therapy (MDT) for liver oligometastases -comparative analysis between CT-guided interstitial HDR brachytherapy and two SBRT modalities performed on double-layer and single layer LINACs. Front. Oncol. 14, 1478872 (2024).

von Elm, E. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335, 806 (2007).

Cheung, P. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for oligoprogressive cancer. Br. J. Radiol. 89, 20160251 (2016).

Cha, Y. J. et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver oligo-recurrence and oligo-progression from various tumors. Radiat. Oncol. J. 35, 172–179 (2017).

Westover, K. D. et al. SABR for aggressive local therapy of metastatic cancer: A new paradigm for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Amst. Neth. 89, 87–93 (2015).

Reyes, D. K. & Pienta, K. J. The biology and treatment of oligometastatic cancer. Oncotarget 6, 8491–8524 (2015).

Ruers, T. et al. Local treatment of unresectable colorectal liver metastases: Results of a randomized phase II trial. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 109, djx015 (2017).

Franzese, C. et al. Predictive factors for survival of oligometastatic colorectal cancer treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy. Radiother. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 133, 220–226 (2019).

Akgül, Ö. et al. Role of surgery in colorectal cancer liver metastases. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 6113–6122 (2014).

Kim, H. K. et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy for colorectal cancer: how many nodules, how many times?. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 6133–6145 (2014).

Rusthoven, K. E. et al. Multi-institutional phase I/II trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver metastases. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 27, 1572–1578 (2009).

van der Pool, A. E. M. et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for colorectal liver metastases. Br. J. Surg. 97, 377–382 (2010).

Lee, M. T. et al. Phase I study of individualized stereotactic body radiotherapy of liver metastases. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 1585–1591 (2009).

Petrelli, F. et al. SBRT for CRC liver metastases. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for colorectal cancer liver metastases: A systematic review. Radiother. Oncol. 129, 427–434 (2018).

Tomita, K. et al. Evidence on percutaneous radiofrequency and microwave ablation for liver metastases over the last decade. Jpn. J. Radiol. 40, 1035–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-022-01335-5 (2022).

Kieszko, D. et al. Treatment of hepatic metastases with computed tomography-guided interstitial brachytherapy. Oncol. Lett. 15, 8717–8722 (2018).

Ricke, J. et al. Local response and impact on survival after local ablation of liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma by computed tomography-guided high-dose-rate brachytherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 78, 479–485 (2010).

Collettini, F. et al. Unresectable colorectal liver metastases: percutaneous ablation using CT-guided high-dose-rate brachytherapy (CT-HDBRT). ROFO Fortschr. Geb. Rontgenstr. Nuklearmed. 186, 606–612 (2014).

Walter, F. et al. Interstitial high-dose-rate brachytherapy of liver metastases in oligometastatic patients. Cancers 13, 6250 (2021).

Deng, T. et al. Third-line treatment patterns and clinical outcomes for metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective real-world study. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 14, 20406223231197310 (2023).

Mayer, R. J. et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 1909–1919 (2015).

Tarpgaard, L. S., Winther, S. B. & Pfeiffer, P. Treatment options in late-line colorectal cancer: Lessons learned from recent randomized studies. Cancers 16, 126 (2023).

Rim, C. H., Lee, J. S., Kim, S. Y. & Seong, J. Comparison of radiofrequency ablation and ablative external radiotherapy for the treatment of intrahepatic malignancies: A hybrid meta-analysis. JHEP Rep. 5(1), 100594 (2022).

Crocetti, L., Scalise, P., Bozzi, E., Candita, G. & Cioni, R. Thermal ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 67(8), 817–831 (2023).

Cisek, P. et al. EORTC/ESTRO defined induced oligopersistence of liver metastases from colorectal cancer - outcomes and toxicity profile of computer tomography guided high-dose-rate brachytherapy. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 42(3), 29 (2025).

Bilski, M. et al. Comprehensive cohort study: computer tomography-guided high-dose rate brachytherapy as metastasis-directed therapy for liver metastases from colorectal cancer in repeat oligoprogression. Radiol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11547-025-01988-y (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: P.C., M.B., Ł.K. Methodology: P.C., M.B. Data Collection: I.K-C., E.W., M.B., P.C. Formal Analysis: P.C., S.S. Investigation: P.C., M.B, M.O. Resources: Ł.K., M.B., S.S. Data Curation: P.C., I.K-C., M.O. Writing—Original Draft Preparation: P.C., M.B., Ł.K. Writing—Review & Editing: Ł.K., B.A.J-F., J.F. Visualization: P.C. Supervision: M.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cisek, P., Kuncman, Ł., Jereczek-Fossa, B.A. et al. Computed tomography guided high dose rate brachytherapy for induced oligoprogression of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Sci Rep 15, 22735 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09227-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09227-0