Abstract

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) representing 85% of cases. Advances in treatment modalities, including stereotactic radiation therapy, have improved outcomes. However, possible synergistic effects of these therapies remain underexplored at the molecular level. This study investigated high-dose radiation-induced proteomic changes in lung adenocarcinoma cell line HCC-44 grown adherently and cell line A549, grown as adherent cells or spheroids. Our hypothesis was that proteins upregulated by 10 Gy irradiation serve as resistance drivers in cancerous cells and can thus represent potential therapeutic targets. The label-free mass spectrometry revealed distinct proteomic responses to 10 Gy irradiation, varying by cell line and culturing conditions. Differentially expressed proteins elevated in the irradiated samples included ephrin type-A receptor 2 (EPHA2) in adherent cells and insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor, tetraspanin 3 as well as cathepsin D (CTSD) in spheroids. The validation of these targets was carried out via Western blot, immunofluorescence, viability assay and spheroid formation assay which demonstrated that irradiation sensitized adherent NSCLC cells to EPHA2 and CTSD inhibitors. These findings underscore the potential of integrating radiation and targeted therapies in NSCLC treatment, and highlight EPHA2 as a promising candidate for future therapeutic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer remains to be a leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. There are two major types of lung cancers: small-cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the latter comprising about 85% of all the lung cancer types. Historically, metastatic NSCLC (mNSCLC) has had a poor prognosis and 5-year overall survival (OS) has stayed under 10%1. Over time, treatment options have evolved gradually, and combining different treatment modalities may improve survival significantly.

Oligometastatic disease (characterized by the presence of up to 5 metastases in up to 2 different organs) with its improved survival rates is now being distinguished from other metastatic diseases. In 2020, long-term results of the SABR-COMET Phase II randomized trial were made available. In this study, patients with oligometastatic disease were treated with either standard-of-care therapy (SOC) or SOC with radical local therapy using stereotactic radiation therapy; the 5-year OS rate was 17.7% vs. 42.3%, respectively2. Systemic therapy has also evolved over time and new pharmaceuticals have emerged to clinical practice, making treatment more effective while reducing the potential side effects. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent a novel class anti-cancer drugs that bring much value to the treatment of various metastatic cancer sites, such as those in metastatic breast cancer and lung cancer3,4. ADCs consist of three main components: antibody binding to the extracellular part of the target of interest, cytotoxic payload, and the connecting linker. In contrast to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, the expression level of a specific target has less impact on the effectiveness of ADCs, where the cytotoxic payload plays a more significant role. For example, in the phase 3 ASCENT trial, metastatic triple negative breast cancer patients with low TROP2 expression still demonstrated improved progression-free survival with ADC sacituzumab govitecan5.

Increasing number of ADCs in lung cancer treatment are undergoing clinical trials. Already established targets are human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) with trastuzumab deruxtecan, HER3 with patritumab deruxtecan, trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (TROP2) with sacituzumab govitecan, tyrosine kinase receptor c-Met (MET) with telisotuzumab vedotin. Currently in Europe, trastuzumab deruxtecan is the only approved ADC in second line NSCLC with HER2 activating mutations6. There are also several early-phase clinical trials assessing additional targets-of-interest, for example NECTIN4, mesothelin, and ephrin receptor A2 (EPHA2)7,8. While combinations of systemic therapy and local therapy agents have been investigated intensely over time, there is still little clinically relevant information whether stereotactic radiation therapy enhances the effect of ADCs.

Here, we set out to explore the high-dose radiation-induced changes in the proteome of lung adenocarcinoma cell lines grown adherently or as 3D spheroids. The high-dose radiation approach was chosen as it imitates clinically relevant stereotactic radiation therapy. As the in vitro models, we chose two well-characterized lung adenocarcinoma cell lines that we have studied previously: HCC-44, expressing high levels of PD-L1 and featuring KRAS activating mutation G12C as well as TP53 loss-of-function mutations9; and A549, expressing low levels of PD-L1 and featuring KRAS activating mutation G12S and loss-of-function mutations in STK11 and KEAP110. We hypothesized that the proteins upregulated by radiation will represent the survival strategies of cancerous cells, and the identified upregulated proteins could therefore serve as putative drug targets in future studies.

Results

Proteome changes associated with irradiation are dependent on the cell line and the mode of culturing

As the first step of our study, we performed mass-spectrometric profiling of the proteome corresponding to the non-irradiated or 10 Gy-irradiated cells grown adherently (in case of both HCC-44 and A549) or as spheroids (only in case of A549). 10 Gy was chosen based on our previous experience with the same lines to ensure the presence of the surviving population11and based on the similar studies by other groups12,13,14,15. The cells were left to recover for 72 h after irradiation and three independent experiments were carried out for each treatment.

We identified a total of 5188 proteins (present in at least one of the measured samples); in each individual sample, the number of detected proteins exceeded 4000, with minor variation between the treatments and independent experiments (see Supplementary Figure S1). This indicated that the chosen timing was correct, avoiding excessive cell death in the irradiated samples and thus enabling characterization a sufficiently versatile proteome. According to the PCA plot (Fig. 1A), the clusters corresponding to the A549 vs. HCC-44 cell line were separated along the PC1 dimension and the clusters corresponding to the adherent vs. spheroid A549 cells were separated along the PC2 dimension. The difference between the clusters corresponding to the irradiated vs. non-irradiated cells was less pronounced, yet still distinguishable for both cell lines and culturing conditions in case of A549 cells.

Characteristic clustering and differentially expressed proteins according to the mass-spectrometry data. (A) PCA plot of the proteomic data indicating differentiation between the treatments (N = 3 for each treatment). The plot was generated using the complete mass-spectrometry data after imputation. The colour codes for different cell lines, culturing modes and irradiation conditions are shown below the plot; NT corresponds to non-treated cells. (B) Venn diagram of the DEPs in irradiated vs. non-irradiated cells in different cell lines and culturing conditions (FDR < 0.05 in any compared treatments).

Next, we established the proteins which were significantly up- or downregulated by the irradiation (FDR < 0.05). The Volcano plots corresponding to three compared categories (adherent HCC-44 cells, adherent A549 cells and A549 spheroids) are presented in Supplementary Figures S2-S4. The number of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs, see Supplementary Table S1) was highest in the adherent A549 cells (48 DEPs, of which 26 were upregulated and 22 downregulated by irradiation), followed by the A549 spheroids (33 DEPs, of which 12 were upregulated and 21 downregulated by irradiation) and the adherent HCC-44 cells (29 DEPs, of which 22 were upregulated and 7 downregulated by irradiation). According to the Venn diagram (Fig. 1B), the overlap of DEPs was highest in case of A549 adherent cells and A549 spheroids (15 DEPs). Only three DEPs were shared between the adherent A549 cells and HCC-44 cells [ephrin type-A receptor 2 (EPHA2), optineurin (OPTN) and microtubule-associated protein 1B (MAP1B)], and only two DEPs between A549 spheroids and adherent HCC-44 cells [aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A3 (ALDH1A3) and karyopherin subunit alpha 2 (KPNA2)]. No common DEPs were found between all three compared categories.

The further analysis of DEPs focussed separately on the upregulated and downregulated proteins in each compared category. Based on the DEPs, we identified the significantly upregulated or downregulated pathways using the online platform g: Profiler; the results are presented in Supplementary Table S2 and summarized concisely in Table 1. Overall, the pathway analysis confirmed that HCC-44 cell line responded to irradiation differently than A549 cell line, while A549 adherent cells and spheroids shared multiple downregulated but not upregulated pathways. Particularly, in HCC-44, upregulation of G2/M markers and downregulation of multiple metabolic processes occurred upon irradiation. In the adherent A549 cells, the upregulated pathways were rather related to cytoskeleton and cellular adhesion, while downregulated pathways involved DEPs responsible for the DNA damage response. The latter observation was also valid in the context of A549 spheroids, while no significantly upregulated pathways could be identified in this model. The generally known functions related to the DEPs upregulated in irradiated spheroids involved the acyl-coenzyme A signalling [represented by the acyl-CoA dehydrogenase family member 8 (ACAD8) and acyl-CoA thioesterase 8 (ACOT8)], oxidoreductive catalysis [represented by ACAD8, ferredoxin reductase (FDXR) and 5-oxoprolinase (OPLAH)], and vesicle formation and trafficking [represented by cathepsin D (CTSD), DnaJ homolog subfamily C member 13 (DNAJC13), insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor (IGF2R), OPLAH and tetraspanin 3 (TSPAN3)].

Based on the mass-spectrometry results, we chose for the further validation three proteins for which the membranous localization has been reported previously16,17,18: EPHA2, which was elevated upon irradiation in both HCC-44 and A549 cell lines grown adherently [binary logarithm of fold change (LFC) values of 1.1 and 0.72, respectively]; and IGF2R and TSPAN3, which were elevated upon irradiation in A549 spheroids (LFC values of 1.1 and 0.89, respectively). Furthermore, we included in our validation set cathepsin D (CTSD), which belongs under the aspartic protease family and for which extracellular, lysosomal, mitochondrial as well as cytosolic localizations have been reported19,20. According to our mass-spectrometry data, CTSD was elevated upon irradiation in A549 cell line independently on the mode of culturing (LFC values of 0.82 and 0.67 in adherent cells and spheroids, respectively; Supplementary Table S1).

Immunostaining confirms radiation-induced increase in EPHA2, IFG2R and TSPAN3 levels

Initially, we set out to confirm whether the radiation-induced increase in EPHA2, IGF2R, TSPAN3 and CTSD levels can be detected by Western blot in lysates of HCC-44 and A549 cells grown adherently, or in lysates of A549 spheroids. The treatment and the subsequent culturing of cells was carried out as in case of the proteomic experiment, with lysis performed at 72 h after irradiation.

Representative examples of immunostaining and pooled data summarizing the loading control- and radiation status-normalized immunostaining intensity are presented in Fig. 2A-D; the images of full membranes are shown in Supplementary Figures S5-S8. According to Western blot, all validated proteins could be detected in both irradiated and non-irradiated cells. While the EPHA2 signal showed the trend towards increase upon irradiation in all compared categories (adherent HCC-44 cells, adherent A549 cells, and A549 spheroids), the increase was not statistically significant due to high variation between the experiments; in case of HCC-44, borderline significance was achieved (P < 0.1). In case of IGF2R, a trend towards increase upon irradiation was evident for adherent HCC-44 cells and A549 spheroids, whereas the latter trend was also statistically significant (P < 0.05). No statistically significant comparisons were found for TSPAN3 and CTSD status in irradiated vs. non-irradiated cells, although the trend towards the radiation-induced increase was observable in all compared categories for TSPAN3, and in adherent cells for CTSD.

Validation of the radiation-induced expression of the targets chosen based on the proteomics data using Western blot. Targets: (A) EPHA2; (B) IGF2R; (C) TSPAN3; (D) CTSD. Top part of each panel: representative examples of staining in Western blot; data from a single experiment with each target is shown. Lane 1 corresponds to non-irradiated HCC-44 cells grown adherently, lane 2 to irradiated HCC-44 cells grown adherently, lane 3 to non-irradiated A549 cells grown adherently, lane 4 to irradiated A549 cells grown adherently, lane 5 to non-irradiated A549 cells grown as spheroids, lane 6 to irradiated A549 cells grown as spheroids. For better visualization, the contrast of images was enhanced and the brightness was reduced. In (A) and (B), TUBA1A was used as the loading control; in (C) and (D), ACTB was used as the loading control. Bottom part of each panel: pooled Western blot staining data normalized first to loading control and then separately to the corresponding non-treated control (NT) in each independent experiment (N = 4). Each column represents average ± standard error of mean; the immunostained protein names are mentioned in the graph header and the cell lines and treatment conditions below the graph. The quantification shown was carried out using non-modified images. Statistical significance of paired comparisons (t-test): * corresponds to P < 0.05; (*) corresponds to P < 0.1; ns, not significant.

Next, we explored the intensity of immunostaining of the same set of proteins in the adherently cultured HCC-44 and A549 cells by comparing the non-irradiated cells and cells fixed at 48–72 h after 10 Gy irradiation. In the 72-h experiment, we also immunostained the pTyr588-autophosphorylated form of EPHA2 (phospho-EPHA), and performed not only epifluorescence microscopy but also total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy to focus specifically onto the plasma membrane by exciting a pool of fluorophores in the direct vicinity to the plate bottom. The representative examples of microscopy images are shown in Fig. 3 (phospho-EPHA staining at 72 h post-irradiation), Supplementary Figures S9-S12 (staining of other proteins at 72 h post-irradiation) and Supplementary Figures S13-S15 (EPHA2, IGF2R, TSPAN3 staining at 48 h post-irradiation). The pooled quantified signal intensity for the whole cell (N = 4 for 48 h, N = 2 for 72 h) is presented in Figure 4.

Representative examples of phospho-EPHA (the phosphorylated Tyr588/Tyr596 forms of human ephrin type-A receptors 2–4) staining in irradiated vs. non-irradiated adherent fixed cells at 72 h post-irradiation. Data from a single independent experiment is shown in panels A, C, E and G (epifluorescence), and data from another independent experiment is shown in panels B, D, F and H (plasma membrane close to the well bottom). Each panel represents a stitched image of 5 × 5 fields of view; the cell lines and treatment conditions are listed on the left (NT stands for non-treated), whereas the objectives are listed on the top (TIRF stands for the total internal reflection fluorescence). The fluorescence intensity is adjusted to be comparable between A and C, between B and D, between E and G, and between F and H. Scale bar (top left): 100 μm.

Based on the epifluorescence microscopy images, all four proteins were detectable in both irradiated and non-irradiated samples. For EPHA2, the membranous and cytoplasmic staining was evident in both HCC-44 and A549 cells, with clear enrichment in the cell-cell contact areas in both cell lines; a very similar staining pattern was also observed for phospho-EPHA. On the other hand, IGF2R and TSPAN3 rather featured perinuclear and nuclear staining, although weak membranous pool of these proteins could also be observed. Finally, CTSD featured strong staining in both cytoplasmic, perinuclear and plasma membrane areas. According to the TIRF images, in non-irradiated cells EPHA2 and CTSD featured more diffuse staining across the plasma membrane that in the irradiated cells where the signal was enriched at the cell edges.

Validation of the radiation-induced expression of the targets chosen based on the proteomics data using immunofluorescence. Signal intensity established from the microscopy images following IF with cell fixation carried out at 48 h (A-C) or 72 h (D-H) post-irradiation. The immunostained protein names are mentioned in the graph header and cell treatment conditions prior to lysis below the graph; NT stands for non-treated. Each point corresponds to one region of interest in one frame; thick black line shows median and whiskers show interquartile range; data from all independent experiments was pooled (N = 4 for 48 h and N = 2 for 72 h experiments). Statistical significance of paired comparisons (Mann-Whitney test): *** corresponds to P < 0.001; * corresponds to P < 0.05; ns, not significant.

During quantification of the staining intensity according to epifluorescence microscopy, we did not distinguish between the various intracellular localization patterns to mimic the proteomic measurements. According to the pooled IF data, increase of EPHA2 expression upon irradiation was statistically significant in HCC-44 (P < 0.05) but not in A549 cells, while IGF2R and TSPAN3 were elevated upon irradiation only in A549 cells (P < 0.001) at 48 h post-irradiation. At 72 h post-irradiation, statistically significant increase in phosphorylated EPHA2 was still evident in irradiated vs. non-irradiated HCC-44 cells (P < 0.001), whereas the radiation-induced increase of IGF2R, TSPAN3 as well as CTSD was achieved in both cell lines (P < 0.001). Overall, the trends observed in both Western blot and IF generally confirmed the mass-spectrometry results, although some cell line-dependent variation was evident.

Radiation sensitizes adherent NSCLC cells to EPHA2 inhibition

Next, we decided to explore whether interfering with activity of the selected target proteins can affect the growth and proliferation rate of irradiated or non-irradiated lung adenocarcinoma cells. From the four validated proteins mentioned above, a selective inhibitor was commercially available for EPHA2 (ALW-II-41-27, additionally inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 at higher doses of the compound)21,22. In addition, EPHA2 is one of the targets of the clinically used compound regorafenib, which additionally inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor receptors, platelet-derived growth factor receptors and other tyrosine kinases23. Furthermore, an enzyme family-selective inhibitor pepstatin A was commercially available for CTSD24.

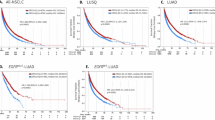

We first assessed the viability/proliferation of the adherent HCC-44 and A549 cells using the resazurin assay at 48 h post-irradiation at 10 Gy; the inhibitors were added onto the cells shortly after irradiation. The results of resazurin assay are summarized in Fig. 5; the normalization of data was carried out separately for the irradiated and non-irradiated cells in each independent experiment to enable better comparison between the putative changes in the dose-response profile. For ALW-II-41-27 and pepstatin A, the dose-response profile followed the biphasic pattern, which is generally indicative of different action mode of compounds at low vs. high dose of inhibitor and can indicate elevated toxicity at higher dose11. For regorafenib, biphasic dose-response was obtained in the irradiated cells, yet in the non-irradiated cells a simple sigmoid function was found to provide a better fit. In case of ALW-II-41-27, the low-dose IC50 value was in the subnanomolar range in both cell lines, while the high-dose IC50 value was in the submicromolar range in HCC-44 cells and in the single-digit micromolar range in A549 cells. In case of regorafenib, the low-dose IC50 value was similarly in the subnanomolar range in both irradiated cell lines, while the high-dose IC50 value was in the single-digit micromolar range in irradiated cells and in the two-digit micromolar range in non-irradiated cells. In case of pepstatin A, the low-dose IC50 value was also in the subnanomolar range in both cell lines, while the high-dose IC50 value was in the submillimolar range.

Viability/proliferation assay in irradiated vs. non-irradiated adherent cells in the presence vs. absence of EPHA2 and CTSD inhibitors. (A, B) Dose-response curves. Pooled normalized viability/proliferation is shown (N = 2–3); the cell line is indicated above the graphs and the treatment conditions below the graphs. Each column represents average ± standard error of mean; the data points were fit to the biphasic equation except in case of regorafenib in non-irradiated cells. MAX corresponds to the non-treated cells in case of non-irradiated cell dose-response and to 10 Gy-treated cells in case of the irradiated cell dose response; MIN corresponds to well without cells. (C) Summary of the potent phase fraction statistics obtained based on the curves for ALW-II-41-27 and pepstatin A shown in panels A and B. (D) Summary of the negative logarithm of IC50 value (high-dose pIC50 in case of biphasic curve) obtained based on the curves for regorafenib shown in panels A and B. In C and D, the cell lines are indicated in the bottom part of the graph; each column represents average ± standard deviation. In all panels, not irr corresponds to cells that are not irradiated but are treated with inhibitor of interest. Statistical significance of the paired comparisons (t-test): *** corresponds to P < 0.001; ** corresponds to P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

Importantly, irradiation of A549 cells triggered sensitization to both inhibitors, which was evident from the significantly increased proportion of the low-dose effect in the corresponding dose-response curves (P < 0.01 for ALW-II-41-27 and P < 0.001 for pepstatin A); no such effect was evident for HCC-44 cells (Fig. 5C). However, in case of regorafenib, statistically significant decrease in IC50 value (measured as increase of pIC50 value) was evident in both cell lines (Fig. 5D).

We next explored whether the same inhibitors could interfere with the formation of spheroids in A549 cell line. For that, we seeded onto the ultra-low attachment (ULA) plate either 10 Gy-preirradiated or non-irradiated cells shortly after irradiation and added simultaneously the dilution series of either ALW-II-41-27, regorafenib or pepstatin A onto the cells. After 72 h and 96 h post-seeding, the area of the formed spheroids was assessed by bright-field microscopy; a set of representative images is shown in Fig. 6A-B and the pooled normalized results are summarized in Supplementary Figure S16 (72 h post-seeding) and Fig. 6C-D (96 h post-seeding). In case of spheroid formation assay, the normalization of spheroid area was carried out according to the non-treated control only in each independent experiment to confirm the effect of irradiation on the spheroid size. Additionally, at both time-points, PI staining of spheroids was used to assess the proportion of the dying population of cells in a spheroid; a set of representative images is shown in Fig. 7A-B and the pooled normalized results are summarized in Supplementary Figure S17 (72 h post-seeding) and Fig. 7 (96 h post-seeding).

Spheroid formation assay in irradiated vs. non-irradiated A549 cells in the presence vs. absence of EPHA2 and CTSD inhibitors. (A, B) Representative examples of spheroids formed during 96 h post-seeding. Data from a single experiment is shown; the treatment conditions are listed in the top right corner of each panel. Scale bar (top left): 400 μm. (C, D) Pooled normalized area of spheroids at 96 h post-seeding (N = 2 for regorafenib and N = 5 for other compounds); the treatment conditions are listed below the graphs. In (A) and (C), NT stands for non-treated. Each column represents average ± standard error of mean. Statistical significance of the grouped comparisons (Kruskal-Wallis test): *** corresponds to P < 0.001; ** corresponds to P < 0.01; * corresponds to P < 0.05; ns, not significant; arrows indicate the treatments (non-treated A549 or irradiated A549) to which other treatments are compared. Statistical significance of paired comparisons (Mann-Whitney test without multiple comparison correction): (***) corresponds to P < 0.001; (**) corresponds to P < 0.01; * corresponds to P < 0.05; ns, not significant. Abbreviations: ALW, ALW-II-41-27; pepstatin, pepstatin A.

Propidium iodide staining of spheroids formed from irradiated vs. non-irradiated A549 cells in the presence vs. absence of EPHA2 and CTSD inhibitors. (A, B) Representative examples of PI staining at 96 h post-seeding. Data from a single experiment is shown; the treatment conditions are listed in the top right corner of each panel. Scale bar (top left): 400 μm. For better visualization, the brightness of images was enhanced. (C, D) Pooled averaged PI signal in spheroids at 96 h post-seeding (N = 2); the treatment conditions are listed below the graphs. The quantification shown was carried out using non-modified images. In (A) and (C), NT stands for non-treated. Each column represents average ± standard error of mean. Statistical significance of the grouped comparisons (Kruskal-Wallis test): *** corresponds to P < 0.001; ** corresponds to P < 0.01; * corresponds to P < 0.05; ns, not significant; arrows indicate the treatments (non-treated A549 or irradiated A549) to which other treatments are compared. Statistical significance of paired comparisons (Mann-Whitney test without multiple comparison correction): (***) corresponds to P < 0.001; (**) corresponds to P < 0.01; * corresponds to P < 0.05; ns, not significant. Abbreviations: ALW, ALW-II-41-27; pepstatin, pepstatin A.

The spheroid formation assay confirmed the potency of the EPHA2 inhibitor ALW-II-41-27, which interfered with cell-cell contacts causing disassembly of spheroids at nanomolar concentrations of the compound. In both non-irradiated and irradiated cells, significant increase in spheroid size was evident already at 0.3 nM concentration of the inhibitor (P < 0.001, paired comparisons to the corresponding negative control). Still, in general, non-irradiated spheroids were more sensitive to the compound as also indicated by the PI signal (significantly elevated at 32 nM or higher concentration of ALW-II-41-27 in non-irradiated cells and at 160 nM or higher concentration of ALW-II-41-27 in the irradiated cells). On the other hand, regorafenib caused reduction of spheroid size, whereas the effect was observed in the irradiated spheroids at lower concentration of the inhibitor (statistically significant difference achieved at 800 nM vs. 1.3 nM regorafenib in non-irradiated vs. irradiated cells). Interestingly, the PI staining was significantly elevated only at 4 µM or higher concentration of regorafenib irrespectively of the irradiation status of the cells (P < 0.01). Finally, pepstatin A caused minute yet statistically significant reduction in spheroid size at 6.4 nM or higher concentration in the non-irradiated spheroids but only at the highest concentration of the inhibitor (20 µM) in the irradiated spheroids (P < 0.05); no significant elevation of PI signal intensity was observed.

Discussion

According to the statistics from 2020, lung cancer is diagnosed annually in 2.2 million patients and causes annually 1.8 million deaths, thus representing the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide25. Metastatic NSCLC treatment has significantly improved over time, being shaped by the emergence of novel pharmaceuticals, such as targeted therapy and immunotherapy. During recent years, ADCs have shown impressive therapeutic activity against metastatic NSCLC – with ongoing clinical trials focusing onto expanding the range of targets as well as indications. Combining stereotactic radiation therapy with systemic therapy in the oligometastatic and oligoprogressive settings has also improved overall survival significantly2. Whether combining novel-class pharmaceuticals ADCs with high-dose irradiation would also improve the outcome is yet to be investigated. This work is focused on finding post-irradiation proteomic changes in the hopes of finding new targets for ADCs and investigates whether the combination of ADCs and high dose irradiation has potential in preclinical models.

Depending on the patient gender, adenocarcinoma constitutes 39–57% of all lung cancer cases25being hence the most prevalent lung cancer subtype. For our in vitro study, we chose lung adenocarcinoma cell lines A549 and HCC-44, which have been characterized in detail in previous studies by us11,26,27 and numerous other research groups. Importantly, we have previously demonstrated that A549 cells are less sensitive to radiation as compared to HCC-44 cells: the former featured no reduction in viability at 48 h post-irradiation with 10 Gy and only 23% reduction in viability at 72 h post-irradiation with 8 Gy, while the latter featured correspondingly 21% and 48% reduction at the same conditions11. Therefore, it was of special interest to investigate which molecular targets ensured post-irradiation survival of A549 cell line.

The proteomic changes at 72 h post-irradiation with 10 Gy were explored using the label-free proteomics strategy in lysates of both cell lines, analogously to our previous study with chemotherapeutic drug cisplatin where we had shown the presence of markers characteristic to either surviving or dying populations of cells26. In the current study, the short-listing of DEPs (Supplementary Table S1) showed that in adherent cells, a higher number of upregulated proteins could be identified after irradiation as compared to the spheroids, which showed in turn a higher number of downregulated proteins upon irradiation (although this observation was limited by the fact that the spheroids could only be obtained for A549 cell line). Based on the pathway analysis of the DEP lists (Table 1), it was evident that the adherent HCC-44 cells responded to irradiation by the cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase (e.g., upregulation of kinesin-like protein KIF2328 or karyopherin KPNA229). This was indicative of the DNA damage, thus being in line with the higher radiation sensitivity30. Still, a population of HCC-44 cells also featured increase of adhesion marker EPHA2, which has been shown to contribute to cancer resistance mechanisms in NSCLC after irradiation31. In turn, the adherent A549 responded to irradiation by the decreased damage response markers – e.g., condensing complex component SMC432, or minichromosome maintenance proteins MCM2-MCM6 which form the catalytic core of the replicative helicase complex in eukaryotes, being one of the central targets in the regulation of the genomic DNA replication in both normal as well as stress conditions33. On the other hand, irradiation caused elevation in markers of cell adhesion – e.g., EPHA234, non-muscle myosin MYH935, or myoneurin PALLD36. While the decrease in MCM2-MCM6 cannot be unequivocally interpreted as the sign of resistance to therapy as both overexpression and decrease in MCM protein levels has been shown to contribute to cancer37, the absence of clear cell cycle arrest markers and the increase of the cell-cell contact-ensuring proteins point to the cell adhesion-mediated radioresistance38. Interestingly, several DEPs associated with radiation effect in this study were identical to the markers identified in our previous study where the same cell lines were grown adherently and treated with 1 µM cisplatin for 48 h26: e.g., upregulation of KIF23, KPNA2 and EPHA2 in HCC-44, upregulation of ferredoxin reductase FDXR in A549, and downregulation of MCM2 in A549 was observed in both studies.

The pathways downregulated by irradiation were similar in the adherently cultured A549 cells and spheroids, thus confirming the intrinsic tendency towards increased radioresistance of this cell line. However, A549 spheroids did not show a certain pattern of upregulated pathways in the current study (Table 1), likely mirroring the presence of several cell populations in spheroids consistent with the more physiological-like status but also complexity of the 3D- versus 2D-cultures. A set of DEPs (ACOT8, FDXR, etc.) found to be induced by radiation in spheroids is responsible for catalytic processes in mitochondria and peroxisomes, which are known to promote survival-ensuring metabolic changes in response to environmental stress39,40,41; in the context of 3D culturing, elevation of these enzymes might arise from the combination of ionizing radiation and limited availability of oxygen. Another set of radiation-induced DEPs (CTSD, IGF2R, TSPAN3, etc.) is linked to extracellular and intracellular vesicle trafficking42,43,44,45 processes that are both shaped by and contribute to the unique microenvironment of spheroids, where dense cellular architecture enables dynamic intercellular signaling and feedback regulation. These DEPs likely participate in the survival mechanisms that rely on the close cell-cell interactions characteristic of 3D cultures. Indeed, it has been demonstrated in literature that overexpression of IGF2R and CTSD can lead to radioresistance46,47, and the cancer-associated functions of these two proteins might be linked on the level of lysosomal activity and autophagy dysfunction48,49,50. Less evidence is available for TSPAN3, although it has been reported to sustain survival of NSCLC cells by promoting recycling and upregulation of integrin b1, thus facilitating interaction of cancer cells with the extracellular matrix51.

For validation, we chose EPHA2, IGF2R, TSPAN3, and CTSD as the three former proteins have been shown to localize on the cell plasma membrane16,17,18 and could thus serve as putative targets for the antibody-drug conjugates in combination with irradiation as a future therapeutic strategy. Additionally, we decided to explore CTSD, which has been characterized as a secreted protein52being thus also putatively accessible to the antibody-based strategies. In our work, slight yet statistically significant elevation of IGF2R and TSPAN3 levels upon irradiation was evident in adherent A549 by IF (P < 0.001 for both targets) after 48 h, whereas after 72 h, the increase was evident in both cell lines and also in case of CTSD (P < 0.001 for all targets). Less significant finding were founds by Western blot: only minor increase of IGF2R in the irradiated A549 spheroids could be established (P < 0.05; Fig. 2), although the trends towards the radiation-induced increase were also observable in case of TSPAN3 for all comparisons (here, the statistical significance was likely impacted by the low expression level of the target that was also confirmed in IF) and for CTSD in adherent cells. The differences between IF and Western blot results can be at least partially explained by the fact that only lysate supernatants were utilized for the latter, as the membranous fraction of lysates had too high viscosity for carrying out the SDS-PAGE; in this way, a part of the signal from the membranous pool of proteins of interest might have been lost.

The good agreement of proteomics results with functional assays was further confirmed during validation of EPHA2 as the radiation-induced target. Ephrin receptors constitute the largest family of the receptor tyrosine kinases and are directly affected by the cell-cell contacts as the activating ligands (ephrins) are themselves tethered to the membranes of the cells53. The enriched staining of EPHA2 and autophosphorylated form of EPHA2 at the cell-cell interfaces was also found in our IF experiments (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figure S11), indicating the activated state of the kinase at the tight cellular contact sites54. In normal conditions, EPHA2 is almost exclusively expressed in proliferating epithelial cells55yet in the pathological context, it is abundant in different cancer sites, including lung cancer. Indeed, EPHA2 overexpression has been correlated to poor prognosis56 and resistance to irradiation31,57and several studies report overcoming radioresistance by inhibiting EPHA2 kinase activity or reducing EPHA2 expression21,58,59. Interestingly, the radioresistance-related roles of EPHA2 have been correlated to the non-canonical activity of the kinase via the radiation-induced rapid phosphorylation of EPHA2 at serine 897 by the ribosomal S6 kinase; phospho-Ser897 EPHA2 translocates to the nucleus, where it forms complex with DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit, thus promoting the non-homologous end joining pathway of DNA repair31,57. While we plan to investigate differential roles of the canonical and non-canonical signaling of EPHA2 in the context of ionizing radiation impact within the frame of our future studies, EPHA2 has been explored as a target in various novel anti-cancer therapies, including antibody-drug conjugates8and preliminary success of EPHA2-targeting small molecular-weight compounds as well as nanoparticles has been demonstrated in animal models22,60.

According to our assays, reliance of irradiated NSCLC cells on the EPHA2-mediated pathways was confirmed in the context of all tested systems, also providing insight into the characteristic differences between the cell culturing modes. While proteomics data indicated significant increase in EPHA2 levels upon irradiation of adherent cells (FDR < 0.05), a trend towards higher levels in irradiated vs. non-irradiated A549 spheroids was also observed (LFC value of 0.356), although the statistical significance was not achieved. According to the Western blot (Fig. 2) and IF data (Fig. 4), radiation-induced increase of the EPHA2 levels was more pronounced in HCC-44 cells, whereas TIRF images showed that irradiation of both cell lines triggered enrichment of the phosphorylated form of EPHA2 on the plasma membrane which was not observable for the total kinase staining (Fig. 3 vs. Supplementary Figure S9). The functional assays indicated complex relationship between the EPHA2 status and EPHA2 inhibitor sensitivity. Namely, in viability assay (Fig. 5), increase of sensitivity towards the EPHA2-selective inhibitor ALW-II-41-27 occurred in A549 rather than HCC-44 cells, whereas the increase of sensitivity towards the multi-target inhibitor regorafenib occurred in both cell lines. On the other hand, in the spheroid formation assay (Fig. 6), significant impact of low-dose ALW-II-41-27 on spheroid morphology was more pronounced in the non-irradiated A549 cells, while the impact of regorafenib was morphologically different (spheroid area decrease instead of increase) and more pronounced in the irradiated cells. Notably, the low nanomolar activity of ALW-II-41-27 was somewhat unexpected as it has been used at a remarkably higher (1 µM) concentration in studies of cervical cancer or NSCLC cell lines21,22. The previous reports, however, did not explore either high-dose radiation of 3D cell culture context, which was addressed in detail in the current study.

This study has several limitations. First, it is restricted to the in vitro settings, whereas only two lung adenocarcinoma cell lines were used, with one yielding self-assembling spheroids. Further, validation of a limited number of targets was carried out using a single antibody or inhibitor per target, without application of knockout or knockdown techniques. Additionally, minor or borderline significance was achieved in several assays used for validation. Despite these constraints, our findings confirm EPHA2 as a promising target for combating the surviving cancer cell population following irradiation. Also, because we chose more aggressive type on NSCLC cell line A549 with its low PD-L1 expression level, KRAS-activating mutation and loss-of-function mutations in STK11 and KEAP1, our results bring valuable information and new potential treatment options for future studies – especially with treatment-resistant NSCLC. Overall, this study emphasizes the need for further exploration of EPHA2 in animal models to validate possible synergy between tumor irradiation and EPHA2 inhibition in a physiological context. Moreover, EPHA2 as well as the other proteins of interest highlighted in this study should be assessed in patient biopsy specimens to provide valuable insights into their clinical relevance and role in cancer recurrence.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, cell lines and equipment

The list of materials used was mostly analogous to our previous studies11,26,61. Human non-small cell lung carcinoma (adenocarcinoma) cell line HCC-44 and human lung carcinoma (adenocarcinoma) cell line A549 were from the Leibniz Institute DSMZ (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH). The solutions and growth medium components for the cell culture were obtained from the following sources: phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), foetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) – Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany); a mixture of penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin B – Capricorn (Ebsdorfergrund, Germany). For treatment of cells, ALW II-41-27, regorafenib and pepstatin A (all from Selleckchem; Munich, Germany) were used.

The cells were grown at 37 °C in 5% CO2 humidified incubator (Sanyo; Osaka, Japan). The number of seeded or collected cells was counted using TC-10 cell counter (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA). During the sample treatment prior to proteomics or Western blot, the cells were grown either as adherent culture on the Falcon 75 cm² canted neck tissue culture-treated flasks with vented caps (Corning; Durham, North Carolina, USA) or as scaffold-free spheroids on Elplasia 12 K flasks (Corning; Oneonta, New York, USA). For irradiation, the flasks were positioned between the 2 slabs of solid water phantom (30 cm × 30 cm × 5 cm below, 30 cm × 30 cm × 1 cm above the plates) and irradiated with dose 10 Gy (Gantry angle 0°, collimator angle 0°, field size 25 cm × 25 cm, source to surface distance 100 cm, dose rate 0.6 Gy/min). During the radiation studies, the cells were exposed to 6 MV X-rays (Varian Truebeam 2.5). For microscopy studies, the cells were seeded onto 24-well tissue culture-treated Ibidi black µ-plates (ibidi GmbH, Gräfelfing, Germany). In case of the viability assay, the cells were seeded onto transparent 96-well clear flat bottom cell culture plates BioLite 130,188 (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Rochester, NY, USA). For transfer of the cells to irradiation facility, gas-permeable adhesive moisture seals were used (Brooks Life Sciences, Wotton, Surrey, UK). In case of spheroid formation assay, 96-well black ULA spheroid microplates with clear round bottom were utilized (Corning 4515; Kennebunk, ME, USA).

For proteomics, dithiothreitol (DTT) was purchased from VWR Life Science (Radnor, PA, USA), chloroacetamide (CAA), ammonium bicarbonate (ABC), methylamine, guanidine hydrochloride (Gu-HCl), urea and thiourea from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA). All chemicals were of proteomics grade or ≥ 99% purity. Lys-C and dimethylated trypsin used for protein digestion were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA) and Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA), respectively. All organic solvents used for proteomics were of LC/MS grade from Honeywell (Charlotte, NC, USA).

The liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) apparatus consisted of a Dionex (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano chromatography system coupled to a Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer. The nano-LC setup consisted of a Dionex cartridge pre-column (ID 0.3 mm × L 5 mm, 5 μm C18) and a MS Wil (Aarle-Rixtel, the Netherlands) emitter-column (ID 75 μm × L 50 cm) packed with 3 μm C18 particles (Dr Maisch, Ammerbuch, Germany).

For lysis of cells prior to Western blot, HEPES and NaCl from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany), Triton X from Ferak (Berlin, Germany), EDTA-containing cOmplete™ protease inhibitor cocktail from Roche (Basel, Switzerland) and PMSF from AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany) were used. The total protein content of lysates was established using Pierce™ Coomassie Plus (Bradford) Assay Reagent (Thermo Fischer Scientific; Rockford, IL, USA) and the absorbance was measured at 590 nm using PHERAstar multi-mode reader (BMG Labtech; Ortenberg, Germany). For preparation of SDS-PAGE samples, 4× NuPAGE™ LDS Sample Buffer (Thermo Fischer Scientific; Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 50 mM DTT (Darmstadt, Germany) was used. Protein transfer was performed onto the PVDF membrane (Roche; Mannheim, Germany) in NuPAGE™ transfer buffer (Thermo Fischer Scientific; Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with methanol (Honeywell, Riedel-de Haën™, Seelze, Germany). For the preparation of blocking solution used in Western blot and immunofluorescence (IF) experiments, BSA was obtained from Capricorn Scientific (Ebsdorfergrund, Germany) and PBS (supplemented with Ca2+, Mg2+) from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). The targets of interest were immunostained using the following primary antibodies: the rabbit monoclonal antibody against human Ephrin Type-A Receptor 2 (anti-EPHA2, clone D4A2) from Cell Signaling Technology (catalogue number #6997; Danvers, Massachusetts, USA); the rabbit monoclonal antibody against human Insulin-Like Growth Factor 2 Receptor (anti-IGF2R) from Sigma-Aldrich (catalogue number HPA011332; Saint Louis, Missouri, USA); the rabbit polyclonal antibody against human Tetraspanin 3 (anti-TSPAN3) from Sigma-Aldrich (catalogue number HPA015996; Saint Louis, Missouri, USA); and the rabbit monoclonal antibody against human Cathepsin D (anti-CTSD) from Invitrogen (catalogue number MA5-32127; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). For immunostaining of the loading controls, the mouse monoclonal antibody against Tubulin Alpha 1a (anti-TUBA1A, clone DM1A) from Novus Biologicals (catalogue number NB100-690; Centennial, Colorado, USA) and the mouse monoclonal antibody against human beta-Actin (anti-ACTB, clone AC-15) from Sigma-Aldrich (catalogue number A1978; Saint Louis, Missouri, USA) were used. As the secondary antibodies, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies from Thermo Fischer Scientific (goat anti-rabbit T2191 or goat anti-mouse T2192; Bedford, MA, USA) were used in case of Western blot.

In case of IF, the same primary antibodies were used as in case of Western blot; additionally, the rabbit polyclonal antibody against the phosphorylated Tyr588/Tyr596 forms of human Ephrin Type-A Receptor 2–4 (anti-phospho-EPHA) was purchased from Invitrogen (catalogue number PA5-37811; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The secondary antibodies used in IF [goat cross-adsorbed antibody against rabbit IgG (H + L), conjugated with Alexa Fluor 568; goat cross-adsorbed antibody against mouse IgG (H + L), conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647] and the nuclear stain 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were from Invitrogen (Eugene, Oregon, USA).

Resazurin and PBS for viability assay (supplemented with Ca2+, Mg2+) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). The propidium iodide for staining of spheroids was obtained from Acros Organics (Switzerland). Imaging of spheroids was carried out with Cytation 5 multi-mode reader using bright-field microscopy with 4× air objective (1.613 μm/pixel) and automated focussing regime.

Cell treatment prior to mass-spectrometry

In case of adherent culturing, HCC-44 or A549 cells (passage number below 15) were seeded in growth medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS) onto the 75 cm² flasks (at 1/6 dilution from a confluent flask) and grown for 48 h as in culture. Next, irradiation of some of the flasks was carried out at 10 Gy. After 72 h post-irradiation, the spent culture media were collected into centrifuge tubes; the cells were rinsed with PBS, detached from the plates using 0.25% trypsin, resuspended in the culture medium, and then combined with the corresponding spent media aliquots to collect both detached dying cells and the surviving population. 30 µL aliquots of the obtained cell suspension (total volume of 9 mL per flask) were taken for counting of non-disintegrated cells (the results are shown in Supplementary Figure S18).

In case of 3D culturing, A549 cells (passage number below 15) were seeded in growth medium onto the Elplasia 12 K flasks (at 1/5 dilution from a confluent flask) and grown for 48 h as in culture. Next, irradiation of some of the flasks was carried out at 10 Gy; an equal amount of flasks was left untreated and served as negative control (NT). After 72 h post-irradiation, the spent culture media were collected into centrifuge tubes. The flasks were rinsed with the growth media and PBS and all solutions were combined with the corresponding spent media aliquots. HCC-44 cells were not used in these experiments as we could not establish a protocol for obtaining compact spheroids from this cell line.

The following treatment was performed according to the procedures established previously26. The cells or spheroids were pelleted from the collected suspensions by centrifugation (5 min at 800 rcf) and the pellets were washed twice with PBS. Finally, PBS was removed, and dry pellets were frozen and stored at −90 °C until all independent experiments (N = 3) were finished. The cell pellets were suspended in 10 volumes of lysis buffer (6 M Gu-HCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 50 mM DTT), heated at 95 °C for 5 min, and sonicated in a Bioruptor sonicator (Diagenode, Belgium) for 15 min at 4 °C (10 cycles at “high” setting, 30 s on and 60 s off). Lysates were further homogenised in FastPrep24 bead beater (MP Biomedicals, USA), using 2 × 40 s, 6 m/s pulses with 1 volume of 0.5 mm Zirconia/Silica beads (BioSpec Products, USA). Homogenized lysates were removed from the beads by puncturing the sample tube with a heated needle, placing the punctured tube into fresh 2 mL tube, and centrifuging at 2000 rpm for 2 min. Final lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 17,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. For the following protease treatment, 10 µg of protein was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid/deoxycholate Protocol, and the precipitated proteins were suspended in 20 µL of digestion buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 100 mM ABC, 2 mM methylamine solution). Disulphide reduction and cysteine alkylation was carried out by treatment with 10 mM DTT (30 min at 30 °C) and 30 mM CAA (30 min at room temperature), respectively, in the dark. Samples were pre-digested for 2 h with 1:100 enzyme to protein ratio of Lys-C (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan), diluted 5-fold with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, and proteolyzed overnight with trypsin (1:50 enzyme to protein ratio; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 25 °C. Digested samples were desalted with in-house made C18 StageTips prepared in-house62 and reconstituted in 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid for the following mass spectrometry analysis.

Label-free proteomics

The methodology used was analogous to our previous study26. Briefly, 2 µg of tryptic peptides was injected onto Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano liquid chromatography system (Dionex, California, USA). The chromatography setup consisted of a 0.3 × 5 mm trap-column (5 μm C18 particles; Dionex, USA), followed by the analytical 50 cm × 75 μm emitter-column (MS Wil; Aarle-Rixtel, Netherlands) prepared in-house with 3 μm C18 particles (Dr Maisch, Germany). The columns were operated at 45 °C. Analytical columns was run at 300 nL/min and developed with 120 min 8–40% buffer A to B gradient (buffer A: 0.1% formic acid in water; buffer B: 80% acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid in water). Eluted peptides were injected in real time into a Q Exactive HF (Thermo Fisher Scientific) tandem mass spectrometer, using a nano-electrospray source with a spray voltage set at 2.5 kV (liquid junction connection). One 350–1400 m/z mass-spectrometry (MS) scan (resolution of 60 000 at 200 m/z) was followed by MS/MS analysis (resolution of 30 000 at 200 m/z) of the 12 most intense ions using high-energy collisional dissociation fragmentation (normalized collision energy of 26). The ion target number and injection time for MS and MS/MS were set at 3 × 106 ions and 50 ms, and 1 × 105 ions and 41 ms, respectively. The dynamic exclusion time was set at 50 s and only charge states from + 2 to + 5 were selected for the MS/MS analysis.

Bioinformatic analysis of proteomic data

The analysis pipeline was analogous to our previous study26. MS raw data were processed with the MaxQuant software (version 2.2.0.0)63searching for the protein and peptide matches from the UniProt human reference proteome database (downloaded 09.21.2023)64. Methionine oxidation, and protein N-terminal acetylation were set as variable modifications, while cysteine carbamidomethylation was defined as a fixed modification. Tryptic digestion rule (cleavages after lysine and arginine without proline restriction) was used for in silico digestion of the database. Only identifications with at least 1 peptide ≥ 7 amino acids long (with up to 2 missed cleavages) were accepted and transfer of identifications between runs based on accurate mass and retention time (‘match between runs’) was enabled. Label-free normalization with MaxQuant LFQ algorithm was also applied. Protein and LFQ ratio count (i.e., number of quantified peptides for reporting a protein intensity) was set to 1. Peptide-spectrum match and protein false discovery rate was kept below 1% using a target-decoy approach. All other parameters were default.

Statistical software R v4.2.3 and package DEP65 were used for downstream analysis of the quantified proteins. During preprocessing, proteins that were identified in less than two out of three replicates in at least one condition were filtered out. Next, the proteome data was background corrected and normalized by variance stabilizing transformation. To account for missing values, the k-nearest neighbour imputation method was applied. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed and plotted using the plot_pca function from the DEP package to visualize sample variance and clustering between conditions. Prior to differential analysis in irradiated versus non-treated cells (NT), counts were logarithm-transformed. R package limma66 was used for analysis of differential expression (irradiated versus non-irradiated cells in different cell lines and culturing conditions) based on the moderated t-statistics, computed via empirical Bayes moderation to stabilize variance estimates. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Proteins were considered significantly different at FDR < 0.05. The final DEP lists (Supplementary Table S1) were generated by eliminating proteins for which the razor + unique peptide count in two out of three replicates considered for the differential analysis was less than 2. Volcano plots were generated using the plot_volcano function from the DEP package to visualize the protein fold changes (x-axis) and adjusted p-values (y-axis) between the compared conditions. The final DEP lists were analysed using the g: Profiler online platform (version e111_eg58_p18_f463989d, database updated on 25/01/202467) to identify the significantly altered pathways associated with the radiation treatment; the results are presented in Supplementary Tables S2 (up- and down-regulated proteins analysed separately) and S3 (up- and down-regulated proteins pooled for the same cell line and culturing method).

Western blot

The treatment of the cells (2D-cultured HCC-44, 2D-cultured A549, A549 spheroids) and collection and storage of the cell pellets was carried out in the same way as described for the mass-spectrometry studies. The lysis of cells was carried out as previously described68. For preparation of SDS-PAGE samples, the total protein concentrations in lysate supernatants were established using Bradford assay and the concentrations of samples were adjusted according to the most dilute sample. The SDS-PAGE samples were denatured under reducing conditions by 15 min incubation at 75 °C; prior to SDS-PAGE, the samples were stored at −20 °C. The subsequent procedures were carried out according to the previously published protocol68 with exception of the transfer time (25 min at 20 V was used in this study). The primary and secondary antibodies were used at the maximal dilutions suggested by the manufacturers.

Immunostaining and fluorescence microscopy

The cells were seeded onto the 24-well plates with the working volume of 0.5 mL and density of 4000 or 8000 cells per well (for HCC-44 and A549, respectively) and grown overnight. Next, irradiation of cells at 10 Gy was carried out as described above; the non-treated cells (NT) were kept on a separate plate. In the initial experiments (N = 4), to prevent achieving overly high density of the cells on the non-irradiated plate, the cells were subsequently placed to the incubator and grown on the plate only for 48 h post-irradiation; in the subsequent experiments (N = 2), the cells were grown for 72 h, mirroring the time-line of the proteomics experiment. After the incubation, the medium was removed, the cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed directly on the plate with cold methanol (15 min at −20 °C). Afterwards, methanol was removed, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and blocking with 1% BSA in PBS (weight/volume) was performed for 1 h at rt, followed by the staining and wash procedures analogously to the previously reported protocol69 with the solution volumes adjusted for a 24-well plate. The following dilutions were used for the primary antibodies: in case of anti-EPHA2, 1:500; in case of anti-IGF2R, 1:400; in case of anti-TSPAN3, 1:200; in case of anti-CTSD, 1:500; in case of anti-phospho-EPHA, 1:200; and in case of anti-TUBA1A, 1:2000. The secondary antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilution; for the staining of nuclei, 300 nM DAPI in PBS was applied.

Fluorescence microscopy with immunostained cells was initially carried out with Cytation 5 multi-mode reader using 20× air objective (0.3225 μm/pixel). For DAPI, 365 nm LED and DAPI filter block were used; for Alexa Fluor 568, 523 nm LED and RFP filter block were used; for Alexa Fluor 647, 628 nm LED and CY5 filter block were used. The imaging parameters (LED intensity, signal integration time, and camera gain) were first optimized in the manual imaging mode for each antibody, and the same parameters were then used for this antibody for all plates in all independent experiments (N = 4). The imaging was performed in the automated mode; 25 images per well were taken and the DAPI channel was used for autofocusing.

For more detailed exploration of intracellular localization, the next round of imaging (widefield epifluorescence and TIRF) was conducted usingan inverted microscope built around a Till iMIC body (Till Photonics/FEI, Germany), equipped with UPlanFLN 10× air (numerical aperture 0.30) and TIRF APON 60 × oil (NA 1.49) objective lenses (Olympus Corp., Japan). The samples were sequentially excited with 405 nm (150 mW, for DAPI staining) PhoxX laser diode or AOTF-controlled 561 nM (106 mW, for secondary antibody staining) Cobolt Jive DPSS laser (Cobolt AB, Solna, Sweden) combined in the SOLE-6 light engine (Omicron-Laserage, Germany). Excitation light was launched into Yanus scan head, which along with a Polytrope galvanometric mirror (Till Photonics/FEI, Germany) was used to position the laser for widefield epifluorescence or azimuthal 360° TIRF (approx. 100 nm depth) illumination. Excitation and emission light were spectrally separated using imaging filter cube containing a flat 2 mm beamsplitter zt 405/488/561/640rpc (Chroma Technology Co.) and a TIRF emission filter ZET 405/488/561/640 (Chroma Technology Co.). The electron-multiplying charge-coupled device Ultra 897 camera (Andor Technology, UK) was mounted to a microscope through a TuCam adapter with 2× magnification (Andor Technology, UK). The camera was cooled down to −100 °C with the assistance of a liquid recirculating chiller Oasis 160 (Solid State Cooling Systems, USA). The imaging parameters (laser intensity, signal integration time, and camera gain) were first optimized in the manual imaging mode for each antibody, and the same parameters were then used for this antibody for all plates in all independent experiments (N = 2). The imaging was performed in the widefield epifluorescence (with 10x objective) or TIRF (with 60x objective) illumination mode; 25 images (5 × 5 in tile scan mode) per well were taken. Tiles were used for stitching with Fiji plugin70.

Viability assay

The approach used was analogous to our previous studies27,61. HCC-44 or A549 cells (passage number below 15) were seeded in growth medium onto the 96-well plate with the density of 2000 or 3500 cells per well, respectively (within the linear range of the method, optimized in previous studies11). The cells were left to attach for 24 h at 37 °C under the usual culturing conditions. Next, irradiation of some plates at 10 Gy was carried out. 2 h post-irradiation, the growth medium was exchanged, and 5-fold dilution series of biologically active compounds in growth medium were added onto the cells. Henceforth, two separate annotations were used to distinguish the non-treated cells (NT) or the cells treated with inhibitors but not radiation (not irr). Based on the solubility of compounds in the water, the maximal final total concentrations of compounds were 10 µM. An identical volume of growth medium was added to the negative control (100% viability). The final volume per well was 150 µL, and the concentration of DMSO in the treated wells was ≤ 0.1% by volume; on each plate, each concentration of each compound was represented in duplicate or triplicate. To prevent achieving overly high density of the cells on the non-irradiated plate, the cells were subsequently placed to the incubator and grown on the plate only for 48 h post-irradiation (three additional experiments where viability was measured at 72 h post-irradiation were also carried out; the results are shown in Supplementary Figure S19). Next, viability assay was carried out according to the previously published protocol11.

Spheroid formation assay

The optimization of spheroid formation conditions (by varying cell lines, growth medium, number of cells seeded, timing of irradiation, and imaging conditions) was carried out in four pilot experiments (representative images shown in Supplementary Figures S20-S23); the approach used was analogous to our previous study61. A549 cells (passage number below 15) were grown on the two 75 cm² flasks to 80% confluency. Next, irradiation of one flask at 10 Gy was carried out. 2 h post-irradiation, the cells were detached from the plates using 0.25% trypsin, resuspended in the culture medium and then seeded in growth medium onto the 96-well ultra-low attachment plate with the density of 4000 (experiment 1) or 2000 (experiments 2–3) cells per well. At the same time, 5-fold dilution series of compounds in the growth medium were added to the wells. The final total volume in the well was 200 µL and the maximal final total concentrations of compounds were 20 µM (as in general, higher concentrations of compounds are required in 3D cell culture as compared to 2D to achieve the same extent of biological effect). The plates were placed into the incubator and imaged at 72 h and 96 h post-seeding.

To assess the extent of cellular death in the formed spheroids at different time-points, additional experiments were carried out where the spheroids were formed from the pre-irradiated or non-irradiated cells as described above in the presence or absence of ALW II-41-27 or regorafenib. Following the 71-h (N = 2) or 95-h (N = 2) incubation, solution of PI in PBS was added to all wells (final total concentration of 2 µg/mL) and the plates were incubated for 1 h. Finally, imaging was carried out using bright-field (settings – LED intensity 4, integration time 100, detector gain 3) and RFP channel (settings – LED intensity 4, integration time 350, detector gain 15).

Other statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were carried out analogously to the previously reported procedures11,26,61. In all statistical tests, the significance of comparisons is indicated as follows: *** indicates P ≤ 0.001, ** indicates P ≤ 0.01, * indicates P ≤ 0.05.

In case of Western blot, the band intensities corresponding to the EPHA2 (110–130 kDa), IGF2R (270 kDa), TSPAN3 (45 kDa) or cleaved CTSD (sum of 28 kDa and 16 kDa) were normalized to the band intensity of the loading control (TUBA1A, 50 kDa; or ACTB, 42 kDa) in each independent experiment (N = 4). Subsequently, additional normalization to the non-treated samples was then carried out separately for adherent HCC-44, adherent A549, or A549 spheroids (normalized ratio set to 100%). The normalized data for the identically treated cells was then pooled. The pairwise comparisons (staining intensity in irradiated versus non-treated cells) were carried out using the unpaired two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction; due to the small number of pre-planned comparisons (a total of three for each antibody), no additional multiple comparison correction was applied.

In case of IF, three-five frames without any visible artefacts (e.g., dust particles or antibody aggregates) were randomly chosen within a set of 25 frames per well. The mean signal intensity in RFP channel (corresponding to the antibody of interest) was quantified in three representative regions of interest per frame (each region of interest involving 1–3 individual cells) using raw images with non-modified brightness or contrast. The data for the identically treated cells was then pooled for all independent experiments (N = 4 for cells fixed at 48 h post-irradiation and N = 2 for cells fixed at 72 h post-irradiation). Non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used for the paired comparisons (staining intensity in irradiated versus non-treated cells) as the analysed data did not follow the normal distribution according to the D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test. Due to the small number of pre-planned comparisons (a total of two for each antibody), no additional multiple comparison correction was applied.

In case of viability assay, in each independent experiment, the fluorescence intensity measured for the replicate treatments was pooled and the data obtained for the negative control (cells not treated with inhibitor) was plotted against incubation time with resazurin. One time-point within duration of data acquisition was chosen where the signal of the negative control remained in the linear range, and only data measured at this time-point was used for the further analysis. For normalization, data obtained for wells treated with PBS (blank control) was considered as 100% viability; data acquired for the 50 µM resazurin solution (in the absence of cells) was considered as 0% viability. Next, the ratio of absorbance at 570 nm and 600 nm was calculated for each well. The ratios were analysed analogously to the fluorescence intensity data, and the normalized viability values calculated from the fluorescence intensity and the absorbance measurements were pooled. Finally, data from all independent experiments (N = 2 for regorafenib and N = 5 for other compounds in each cell line with 2–3 technical replicates per experiment) was pooled for each individual compound concentration. The pooled normalized viability was plotted against the concentration of compound in the dilution series and fitted to the biphasic equation with the Hill slope values fixed at −1 and the fraction of the curve derived from the more potent phase fixed between 0 and 1. The pairwise comparisons (potent phase fraction or high-dose pIC50 in irradiated versus non-treated cells) were carried out using the unpaired two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction. Due to the small number of pre-planned comparisons (a total of two for each inhibitor), no additional multiple comparison correction was applied.

In spheroid formation assay, the spheroid contour was denoted manually using the freehand selections tool and the area of the spheroid was quantified; in case of disintegrated spheroids with poorly defined borders, the selection involved all dark area covered with cells. The spheroid area was quantified separately for the different time-points in each independent experiment (N = 3 for each treatment with 2 technical replicates per experiment) and normalized by the negative control (cell not treated with inhibitor or radiation) in each independent experiment (area set to 100%). The normalized data for the identically treated cells was then pooled. For the RFP channel images, the average signal intensity of propidium iodide per unit of area was established using the automated image analysis software SpheraSense version 1.271 installed as a MATLAB application version R2024b (Natick, Massachusetts, United States). The data for the identically treated cells within the same cell line was then pooled for all independent experiments (N = 2 for each treatment and each time-point). The grouped comparisons (spheroids treated with inhibitors versus zero inhibitor control) were carried out using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. For the inhibitor-treated cells that did not yield statistically significant differences according to the Kruskal-Wallis test, additional pairwise comparison was carried out for each concentration of inhibitor (against the zero inhibitor control). Due to the relatively small number of pre-planned comparisons (up to eight for each inhibitor), no additional multiple comparison correction was applied; still, the corresponding statistical significance assessment is shown in brackets to alert the readers regarding the absence of the multiple comparison correction in case of the pairwise comparisons.

Other software

For general data analysis, GraphPad Prism 6 (San Diego, CA, USA) and Excel 2016 (Microsoft Office 365; Redmond, WA, USA) were used. To create the Venn diagram, we utilized the interactive tool Venny72. In case of Western blot, IF and spheroid formation assay, ImageJ software (Fiji package73) was used for the image analysis.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository 53 with the dataset identifier PXD057576. Other datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Simeone, J. C., Nordstrom, B. L., Patel, K. & Klein, A. B. Treatment patterns and overall survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer in a real-world, US setting. Future Oncol. 15, 3491–3502 (2019).

Palma, D. A. et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of oligometastatic cancers: Long-Term results of the SABR-COMET phase II randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 2830–2838 (2020).

Bian, D. J. H., Cohen, S. F., Lazaratos, A. M., Bouganim, N. & Dankner, M. Antibody–Drug conjugates for the treatment of Non-Small cell lung Cancer with central nervous system metastases. Curr. Oncol. 31, 6314–6342 (2024).

Koster, K. L., Huober, J. & Joerger, M. New antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) in breast cancer-an overview of ADCs recently approved and in later stages of development. Explor. Target. Antitumor Ther. 3, 27–36 (2022).

Bardia, A. et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan in metastatic Triple-Negative breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1529–1541 (2021).

Wass, R. E., Lang, D., Horner, A. & Lamprecht, B. Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) in lung cancer treatment. memo 17, 198–203 (2024).

Coleman, N., Yap, T. A., Heymach, J. V., Meric-Bernstam, F. & Le, X. Antibody-drug conjugates in lung cancer: dawn of a new era? Npj Precis Onc. 7, 1–12 (2023).

Xiao, T. et al. Targeting EphA2 in cancer. Journal Hematology Oncology. 13, 114 (2020).

Ma’ayan Laboratory of Computational Systems Biology. Gene Set - HCC-44. COSMIC Cell. Line Gene Mutat. Profiles https://maayanlab.cloud/Harmonizome/gene_set/HCC-44/COSMIC+Cell+Line+Gene+Mutation+Profiles

Ma’ayan Laboratory of Computational Systems Biology. Gene Set - A549. COSMIC Cell. Line Gene Mutat. Profiles https://maayanlab.cloud/Harmonizome/gene_set/A549/COSMIC+Cell+Line+Gene+Mutation+Profiles

Lavogina, D. et al. Revisiting the Resazurin-Based sensing of cellular viability: widening the application horizon. Biosens. (Basel). 12, 196 (2022).

Tsutsumi, K. et al. Contribution of Neuropilin-1 in Radiation-Survived subclones of NSCLC cell line H1299. Curr. Issues. Mol. Biol. 43, 1203–1211 (2021).

Adjemian, S. et al. Ionizing radiation results in a mixture of cellular outcomes including mitotic catastrophe, senescence, methuosis, and iron-dependent cell death. Cell. Death Dis. 11, 1–15 (2020).

Zhao, H. et al. Effects of different doses of X–ray irradiation on cell apoptosis, cell cycle, DNA damage repair and Glycolysis in HeLa cells. Oncol. Lett. 17, 42–54 (2019).

Sato, K. et al. A single high-dose irradiation changes accumulation of methotrexate and gene expression levels of SLC and ABC transporters in cancer cells. Front. Pharmacol. 13 (2023).

Chavent, M., Seiradake, E., Jones, E. Y. & Sansom, M. S. P. Structures of the EphA2 receptor at the membrane: role of lipid interactions. Structure 24, 337–347 (2016).

Rezgui, D. et al. Structure and function of the human Gly1619Arg polymorphism of M6P/IGF2R domain 11 implicated in IGF2 dependent growth. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 42, 341–356 (2009).

Thiede-Stan, N. K. et al. Tetraspanin-3 is an organizer of the multi-subunit Nogo-A signaling complex. J. Cell. Sci. 128, 3583–3596 (2015).

Di, Y. Q. et al. Autophagy triggers CTSD (cathepsin D) maturation and localization inside cells to promote apoptosis. Autophagy 17, 1170–1192 (2021).

Ikari, N. & Arakawa, H. Identification of a mitochondrial targeting sequence in cathepsin D and its localization in mitochondria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 655, 25–34 (2023).

Li, X., Li, D. & Ma, R. ALW-II-41-27, an EphA2 inhibitor, inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells via Inhibition of the rhoa/rock pathway. Oncol. Lett. 23, 129 (2022).

Amato, K. R. et al. Genetic and Pharmacologic Inhibition of EPHA2 promotes apoptosis in NSCLC. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 2037–2049 (2014).

Ettrich, T. J., Seufferlein, T. & Regorafenib Recent. Results Cancer Res. 211, 45–56 (2018).

Kozak, A. et al. A new cathepsin D targeting drug delivery system based on immunoliposomes functionalized with lipidated Pepstatin A. Pharmaceutics 15, 2464 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Global variations in lung cancer incidence by histological subtype in 2020: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 24, 1206–1218 (2023).

Saar, M. et al. Exploring the molecular players behind the potentiation of chemotherapy effects by durvalumab in lung adenocarcinoma cell lines. Pharmaceutics 15, 1485 (2023).

Saar, M., Lavogina, D., Lust, H., Tamm, H. & Jaal, J. Immune checkpoint inhibitors modulate the cytotoxic effect of chemotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Oncol. Lett. 25, 152 (2023).

Fischer, M. et al. p53 and cell cycle dependent transcription of Kinesin family member 23 (KIF23) is controlled via a CHR promoter element bound by DREAM and MMB complexes. PLoS One. 8, e63187 (2013).

Yang, X. et al. Novel roles of Karyopherin subunit alpha 2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomedicine Pharmacotherapy. 163, 114792 (2023).

Lonati, L., Barbieri, S., Guardamagna, I., Ottolenghi, A. & Baiocco, G. Radiation-induced cell cycle perturbations: a computational tool validated with flow-cytometry data. Sci. Rep. 11, 925 (2021).

Kaminskyy, V. O. et al. EPHA2 interacts with DNA-PKcs in cell nucleus and controls ionizing radiation responses in Non-Small cell lung Cancer cells. Cancers 13, 1010 (2021).

Wu, N. & Yu, H. The Smc complexes in DNA damage response. Cell. Biosci. 2, 5 (2012).

Bailis, J. M. & Forsburg, S. L. MCM proteins: DNA damage, mutagenesis and repair. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14, 17–21 (2004).

Finney, A. C. et al. EphA2 signaling within integrin adhesions regulates fibrillar adhesion elongation and fibronectin deposition. Matrix Biol. 103–104, 1–21 (2021).

Pecci, A., Ma, X., Savoia, A. & Adelstein, R. S. MYH9: structure, functions and role of non-muscle myosin IIA in human disease. Gene 664, 152–167 (2018).

Li, G. et al. The role of PALLD-STAT3 interaction in megakaryocyte differentiation and thrombocytopenia treatment. Haematologica 109, 3693–3704 (2024).

Simon, N. E. & Schwacha, A. The Mcm2-7 Replicative helicase: a promising chemotherapeutic target. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 549719 (2014).

Babel, L., Grunewald, M., Lehn, R., Langhans, M. & Meckel, T. Direct evidence for cell adhesion-mediated radioresistance (CAM-RR) on the level of individual integrin β1 clusters. Sci. Rep. 7, 3393 (2017).

Li, B. et al. Acyl-CoA thioesterase 8 induces gemcitabine resistance via regulation of lipid metabolism and antiferroptotic activity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Acta Pharmacol. Sin https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-025-01477-y (2025).

He, A., Dean, J. M. & Lodhi, I. J. Peroxisomes as cellular adaptors to metabolic and environmental stress. Trends Cell Biol. 31, 656–670 (2021).

Yan, C. et al. FDXR drives primary and endocrine-resistant tumor cell growth in ER + breast cancer via CPT1A-mediated fatty acid oxidation. Front Oncol 13 (2023).

Zhang, C., Zhang, M. & Song, S. Cathepsin D enhances breast cancer invasion and metastasis through promoting hepsin ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. Cancer Lett. 438, 105–115 (2018).

Niu, L., Zhou, X., Li, D., Zheng, Y. & Li, H. Glycosylation triggers cathepsin D maturation and secretion to promote gastric Cancer development. Am. J. Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2025.02.009 (2025).

Zhang, H. et al. Tspan protein family: focusing on the occurrence, progression, and treatment of cancer. Cell. Death Discov. 10, 1–14 (2024).

Detchokul, S., Williams, E. D., Parker, M. W. & Frauman, A. G. Tetraspanins as regulators of the tumour microenvironment: implications for metastasis and therapeutic strategies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 5462–5490 (2014).

Liu, L. et al. The miR-4306/IGF2R axis modulates the lung adenocarcinoma response to irradiation in vitro and in vivo. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 10, 4494–4510 (2021).