Abstract

Energy efficiency has become a central concern amidst shifting global economic conditions, intensifying climate variability, and geopolitical tensions that have fundamentally reshaped energy consumption and production patterns. Improving energy efficiency is vital for addressing these challenges and advancing the United Nations sustainable development goals (SDGs). Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative tool in this context, offering innovative solutions to complex energy-related problems. While prior research has examined the energy impacts of digital technologies broadly, few studies have isolated the specific contributions of AI. Addressing this gap, our study investigates the influence of AI development on energy efficiency and explores the mechanisms by which AI drives this improvement. Using a fixed-effects model based on prefecture-level data in China, we find that AI significantly enhances energy efficiency. This effect is primarily mediated through two channels: (1) promoting green technological innovation and (2) facilitating the rationalization of industrial structures. Moderation analyses reveal that AI’s positive impact is more pronounced in cities with strong informal environmental regulations and less significant in those with weaker oversight. Additionally, AI adoption yields greater efficiency gains in declining and regenerating resource-based cities compared to their growing and mature counterparts. These findings highlight AI’s pivotal role in advancing energy efficiency and provide actionable guidance for policymakers. To fully realize these benefits, decision-makers should strengthen informal environmental governance and prioritize AI deployment in transitioning resource-based cities. Such measures can help address pressing global energy challenges and accelerate progress toward sustainable development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, as globalization has accelerated and environmental challenges have intensified, sustainable development has emerged as a shared global priority1. In 2015, the United Nations launched the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), urging countries to align economic growth with environmental responsibility and aiming for substantial progress by 2030 to ensure a safer and more equitable future2. Among these goals, energy efficiency plays a pivotal role in achieving sustainable development3,4. In the face of rising geopolitical tensions5 intensifying climate change6 and growing uncertainty, the efficient use of energy has become essential for national development.

Extensive research has identified multiple determinants of energy efficiency, including financial development7,8 carbon emission trading9,10,11 fiscal decentralization12 manufacturing agglomeration13,14 and policy uncertainty15. These factors, grounded in diverse theoretical frameworks, influence energy efficiency through different mechanisms. More recently, digital technologies have attracted growing scholarly attention for their transformative impact on energy systems. Technological advancements are reshaping energy production, operations, and transmission processes. Within the broader context of sustainable development, digital innovation is accelerating the transition toward greener, low-carbon practices16. These technologies have been shown to enhance energy efficiency, modernize energy infrastructure, and restructure energy consumption patterns16,17,18. Drawing on the theory of technological innovation, several studies underscore the beneficial effects of digital transformation—highlighting its role in upgrading industrial structures, optimizing energy use, and improving overall efficiency19. However, some scholars caution that the development of digital infrastructure may also entail adverse environmental consequences, potentially undermining sustainability objectives6. Among the emerging technologies, artificial intelligence (AI) has distinguished itself as a transformative driver of future innovation. In 2022, the number of AI-related patents granted annually has surpassed 62,000—more than seven times the figure recorded in 2018. By the end of 2023, AI systems had equaled or exceeded human performance on standardized assessments in domains such as image classification, basic reading comprehension, natural language reasoning, multilingual understanding, and visual reasoning. Only in areas such as visual common-sense reasoning and complex mathematical problem-solving does AI still lag behind human capabilities (Artificial Intelligence Index Report, 2024).

The integration of AI into the energy sector is increasingly recognized for its transformative potential to accelerate the transition to sustainable energy sources and enhance energy efficiency. Through advanced data analytics, predictive modeling, and automation, AI facilitates smarter decision-making, optimizes energy distribution, and promotes the adoption of renewable energy technologies, thereby contributing to a more resilient and sustainable energy system20,21,22. Proponents argue that AI is reshaping the landscape of energy management and sustainability, driving high-quality urban development and generating measurable environmental benefits, including improved energy efficiency and enhanced ecological outcomes23,24. However, despite these advantages, the energy-intensive nature of AI technologies poses potential risks to overall energy efficiency. Training and operating AI models require substantial computational resources25 which can lead to increased carbon dioxide emissions and environmental degradation19,26. Furthermore, the dependence of AI systems on massive datasets indirectly amplifies the carbon footprint of the information technology sector. For example, data centers in the United States alone account for approximately 2% of national energy consumption. Globally, projections suggest that by 2030, the energy consumption of the information and communication technology (ICT) sector could reach 20% of total energy use, underscoring its growing role in the global energy landscape17,27.

Given the rapid advancement of AI and its dual potential to both transform and challenge sustainable energy use, empirical investigation into its effects is critical. This study centers on China, offering valuable insights into the relationship between AI development and energy efficiency. According to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (China), the country’s AI industry exceeded 500 billion RMB by 2023, encompassing over 4,500 enterprises. As the world’s largest energy consumer and a leading developing nation28,29 China’s pursuit of energy efficiency holds significant implications for global sustainability, particularly for other developing economies. The rapid growth of AI in China presents a unique opportunity to assess its impact and to explore pathways for integrating AI into sustainable development strategies.

Previous studies have predominantly relied on metrics such as the number of industrial robots or AI-related patent applications to assess AI development30,31,32 often focusing on production processes and technological innovation. While informative, these metrics tend to emphasize specific technologies and their direct effects on energy consumption, potentially overlooking AI’s broader and more systemic influence across sectors. To address this gap, this study employs a fixed-effects model using prefecture-level data from Chinese cities to evaluate the relationship between AI development and energy efficiency.

This research advances the literature in four key ways: (1) Unlike prior studies that use proxies such as industrial robots or patent counts, we assess the influence of AI enterprises, offering a more robust reflection of the practical and commercial dimensions of AI implementation. (2) Moving beyond simplistic indicators like the energy-to-GDP ratio, we adopt a Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model based on the Charnes–Cooper–Rhodes (CCR) approach, allowing for a nuanced assessment of energy efficiency across multiple inputs and outputs. (3) We investigate the pathways through which AI impacts energy efficiency, providing an in-depth understanding of the mediating mechanisms that drive these effects. (4) By investigate the functional boundaries of AI in influencing energy efficiency, we offer a clearer picture of its potential scope. By addressing these research gaps, the study delivers critical insights into the direct effects of AI on energy efficiency, especially by unpacking the mechanisms that link AI development with sustainable energy outcomes. The findings offer actionable strategies for policymakers and industry stakeholders, fostering evidence-based decision-making in the integration of AI technologies to support global sustainability goals.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a comprehensive review of the literature and introduces the theoretical hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data sources and research methodology. Section 4 reports the results of the empirical analysis. Section 5 provides extended analysis, focusing on the moderating effects. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the key conclusions and discusses the policy implications and limitations of the study.

Literature review and theoretical hypothesis

Literature review

Key driver of energy efficiency

Efficient and renewable energy systems have been widely recognized as essential contributors to sustainable development by strengthening environmental governance33. Numerous studies have investigated the factors influencing energy efficiency. Among these, environmental considerations have played a pivotal role in shaping financial strategies—particularly through green finance policies, which allocate capital to environmentally sustainable initiatives and lay the groundwork for improved energy performance7,8. Building on this foundation, institutional mechanisms such as carbon trading systems offer market-based incentives to reduce emissions and promote more efficient resource allocation9,10,11. Furthermore, the role of industrial agglomeration has garnered increasing attention. Researchers have found that clustering industries can create economies of scale and generate positive externalities—such as knowledge spillovers—that streamline production processes and enhance energy utilization13,14.

The impact of digital technologies

Recently, , the global shift toward digital transformation—fueled by rapid advancements in digital technologies—has reshaped economic paradigms. Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence and other frontier technologies have emerged as key enablers of innovation and optimization in energy use across diverse sectors19. These advancements not only catalyze economic and social transformation but also foster further technological progress. As a result, growing academic interest is now directed toward understanding how digitalization influences production systems and alters energy consumption patterns.

Within the academic discourse, two divergent perspectives have emerged regarding the impact of digital technologies on energy transition. Proponents of the positive view argue that digital technologies have facilitated high-quality urban development while delivering measurable environmental benefits34. Enhanced innovation capacity35 has improved total factor productivity by optimizing human capital, integrating advanced manufacturing with modern service industries, and implementing cost-reduction strategies36,37, ultimately leading to gains in energy efficiency23,24. However, a contrasting view cautions that technological innovation may also drive-up carbon emissions due to the resource-intensive construction of digital infrastructure, thus exerting adverse effects on the ecological environment19,26.

The impact of AI

Artificial intelligence (AI), as a foundational element of digital technologies, has the potential to profoundly transform energy utilization and enhance efficiency, particularly in the manufacturing sector 21,22,38. Unlike other digital innovations, AI’s core functionalities can be classified into six critical domains: learning, perception, prediction, interaction, adaptation, and reasoning39. For instance, AI’s learning capability allows systems to improve performance over time, thereby increasing operational efficiency and effectiveness. Perception enables the interpretation of complex datasets and dynamic environments, supporting more informed decision-making40. Predictive capabilities facilitate accurate outcome forecasting, which is essential for strategic planning41. Interaction fosters seamless communication between humans and machines, enhancing user engagement and system responsiveness42. Adaptation allows AI systems to respond to novel conditions and tasks, maintaining their relevance and functionality40,43. Finally, reasoning enables AI to draw logical inferences and solve complex problems, effectively augmenting human cognitive capabilities. Empirical studies underscore AI’s impact on energy efficiency. For example, AI-driven ventilation control systems have achieved energy savings of approximately 26% in commercial buildings in the United States44. Unlike conventional digital tools, AI’s ability to autonomously make decisions, recognize patterns, and exhibit “human-like” scientific reasoning enables more nuanced management of production processes, thereby supporting greener manufacturing practices45. Collectively, these capabilities establish AI as a versatile and powerful enabler of innovation and efficiency across diverse industrial and technological domains. Nevertheless, the development and deployment of AI systems are energy-intensive, particularly during manufacturing, model training, and operational phases, potentially resulting in a substantial carbon footprint20.

A growing body of literature explores the complex relationship between AI and energy efficiency, yielding a range of perspectives. Several studies highlight AI’s potential to enhance energy performance, particularly in regions characterized by high levels of green innovation25, and within high-performing organizations where AI integration is more advanced46. However, these benefits are counterbalanced by the substantial energy demands associated with AI model development and training. High-performance computing for algorithm development, training cycles, and data center cooling consumes vast computational resources, contributing to elevated carbon emissions and environmental degradation19,25,26,47. The expansion of digital infrastructure, particularly at scale, exacerbates these challenges, as it entails considerable energy inputs for both construction and maintenance17,28,48,49.

Despite these concerns, AI presents transformative opportunities to address energy-related challenges through predictive analytics, real-time monitoring, and automated control systems. As AI technologies are increasingly adopted across sectors such as manufacturing, transportation, and utilities, they offer sophisticated mechanisms to detect inefficiencies in energy consumption and enable precise, data-driven interventions to enhance operational efficiency50. These applications yield both direct and indirect environmental benefits. For instance, AI can optimize the timely input of production factors to maximize resource utilization51. Furthermore, the integration of intelligent automation within large-scale industrial ecosystems enables production lines to become more flexible, adaptive, self-aware, self-regulating, and capable of autonomous optimization52,53,54. Such advancements significantly reduce resource consumption and promote sustainability, yielding substantial gains in both environmental performance and industrial efficiency.

Literature gap

This literature review synthesizes current scholarship on energy efficiency and offers a comprehensive analysis of its influencing factors. Although considerable research has examined the impact of digital technologies and AI on energy efficiency, several critical gaps remain. Notably, much of the existing literature conflates AI with broader digital technologies, with limited studies isolating AI to examine its distinct effects. Furthermore, prior research often quantifies AI through proxies such as industrial robot density or patent data. In contrast, this paper emphasizes the practical application of AI technologies55,56,57. Additionally, prevailing studies typically assess energy efficiency using a unidimensional framework, such as the ratio of energy input to GDP output. This study adopts a more robust approach by employing the CCR model, which enables a multidimensional assessment of energy efficiency25,56. Most importantly, the underlying mechanisms through which AI influences energy efficiency remain underexplored. These research gaps underscore the need for further empirical investigation—particularly in China, where a nuanced understanding of AI’s role in energy consumption could enhance its applicability in developing economies.

Theoretical background and hypothesis

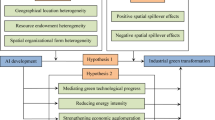

As outlined above, the relationship between AI and energy efficiency is multifaceted, encompassing both opportunities and challenges. When AI technologies transition from patent registration to real-world deployment, their energy usage dynamics evolve. Practical implementation often leads to system optimization and energy consumption reduction. This implies that AI’s capacity to improve energy efficiency is best realized through active application rather than theoretical modeling alone. In this regard, AI offers a unique advantage by integrating energy efficiency with adaptability, interactivity, and creativity22. This phenomenon aligns with the Solow paradox, which posits that the productivity gains from technological innovation are not immediately apparent but emerge gradually over time58. Innovation theory further supports the view that widespread adoption of AI can lead to significant improvements in productivity and operational efficiency. Given AI’s demonstrated potential to reduce energy consumption and disrupt conventional energy use patterns, this study advances the following hypothesis:

H1: AI development can improve energy efficiency.

Green technological innovation refers to enterprise-driven innovations aimed at conserving energy, reducing emissions, mitigating climate-related environmental damage, and enhancing ecological benefits. These innovations also contribute to the modernization of production technologies59. Empirical evidence suggests that AI development positively influences green innovation outcomes9. From the perspective of technological innovation, green innovation can reduce emissions from fossil fuels while promoting the adoption of renewable energy sources11. While green innovation may increase research and development expenditures, it simultaneously enhances productivity and enables effective management of wastewater, exhaust emissions, and solid waste during manufacturing. The implementation of stringent environmental regulations to stimulate technological innovation can significantly reduce environmental pollution without compromising production efficiency60. Accordingly, this study proposes Hypothesis 2:

H2: AI development enhances energy efficiency through fostering green technological innovation.

Prior research has established that energy intensity varies significantly across industrial sectors and that structural transformation can influence aggregate energy efficiency61. Notably, industrial structure is a critical determinant of carbon emissions. The configuration and composition of industries—particularly their dependence on energy-intensive technologies and processes—substantially shape the overall carbon footprint. As such, industrial restructuring has become increasingly central to sustainable development and climate change mitigation strategies62. Upgrading the industrial structure can reduce total carbon emissions by decreasing the share of high-energy-consuming sectors while expanding low-carbon and renewable energy industries. This structural shift not only curtails emissions but also fosters a more resilient and sustainable economic system, aligning with global efforts to combat climate change and advance environmental sustainability63. Artificial intelligence (AI) plays a catalytic role in driving industrial upgrading by optimizing and reshaping industrial configurations. The widespread deployment of AI is expected to revolutionize traditional technologies, thereby enabling a more rational, efficient, and innovation-driven industrial structure. AI and related innovation technologies accelerate industrial adaptation and advancement by promoting industrial clustering and enhancing operational efficiency through the adoption, integration, and diffusion of new technological paradigms64,65,66,67. Technological progress also generates significant capital reallocation and innovation-driven transformation. On one hand, capital—including physical, human, and institutional—tends to flow out of high-energy-intensive sectors and into knowledge-intensive, low-carbon industries. On the other hand, the advancement of emerging industries—characterized by superior energy efficiency and environmental performance—contributes to overall improvements in energy use. Based on this rationale, the present study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: AI development boosts energy efficiency by rationalizing the industrial structure.

In exploring the mechanisms through which AI affects energy efficiency, it is equally important to examine the contextual conditions under which its influence may vary. Drawing on the theory of environmental regulation, prior empirical research indicates that such regulations exert a pronounced influence on both firms’ intentions to innovate and their actual innovation behaviors. This suggests that the effectiveness of AI in enhancing energy efficiency may be contingent upon the regulatory environment and the extent to which firms are incentivized to adopt green technologies. Environmental regulations heighten firms’ awareness of ecological concerns and promote engagement in green innovation activities. For instance, stringent policies can enhance firms’ recognition of the importance of environmental responsibility, thereby increasing their motivation to pursue green innovations68. In developing countries—where formal regulatory frameworks are often weak or inconsistently enforced—informal environmental regulation (IER) emerges as a pivotal mechanism for compelling polluters to take corrective action69. We argue that in such contexts, the impact of AI on energy efficiency is likely to be more substantial in environments characterized by higher levels of IER. Social pressure and public scrutiny, as key drivers of informal regulation, can incentivize firms to adopt AI technologies that reduce emissions and improve operational sustainability. These regulatory dynamics may foster a more conducive environment for AI adoption, thereby amplifying its potential to enhance energy efficiency. On this basis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Informal environmental regulation amplifies the positive impact of AI on energy efficiency.

The developmental stage of a city significantly influences the extent to which AI can enhance energy efficiency. In China, approximately 44% of urban areas are classified as resource-based cities—urban centers whose economies rely heavily on the extraction and processing of natural resources such as minerals, water, and forests70. According to the resource curse theory, the finite nature of these resources implies that sustained extraction will eventually lead to their depletion71. Resource-based cities generally follow four developmental stages: growing, mature, declining, and regenerating. Each stage presents distinct challenges and opportunities for energy use and technological adoption. Growing resource-based cities possess abundant resources and are in the early phases of industrial expansion. These cities are increasingly exploring sustainable practices alongside resource development. Mature cities, having reached peak resource output after years of intensive exploitation, face the challenge of balancing economic growth with environmental preservation. Achieving this balance is vital for long-term sustainability, requiring deliberate efforts to mitigate environmental degradation while maintaining economic performance72. Declining resource-based cities confront the compounded challenges of resource exhaustion and economic instability. These cities must transition from a resource-dependent economy to one that is diversified and sustainable. This transition demands innovative policy measures and strategic interventions. AI can play a critical role in this transformation by identifying inefficiencies, optimizing remaining resources, and facilitating the shift toward sustainable practices. In regenerating cities, resource extraction has largely ceased, and efforts focus on ecological restoration and sustainable urban development. For these cities, AI is essential to supporting smart city initiatives, energy management systems, and environmental monitoring, all of which are key to achieving sustainable urban planning73. Empirical research indicates that the digital economy has a pronounced positive effect on energy efficiency in resource-dependent cities. However, this impact is less significant in cities with more diversified economies. The heightened responsiveness of resource-based cities may be attributed to their centralized industrial structures and initially lower energy efficiency baselines74. Consequently, these cities exhibit both a greater capacity and a more urgent need to leverage AI and other innovative technologies to optimize energy use. As natural resources inevitably dwindle, the priorities of resource-based cities evolve across different stages. In the early stages, the emphasis may be on maximizing extraction efficiency, while in later stages, the focus shifts toward sustainability and ecological recovery. Thus, the demand for AI applications to improve energy efficiency varies across stages, with the need becoming most acute in cities experiencing resource depletion and economic decline. Based on this context, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: The stage of resource development in a resource-based city moderates the impact of AI on energy efficiency.

Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework.

Methods

Data source

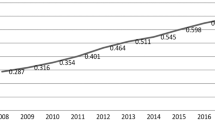

The focus of our study is on the impact of AI on energy efficiency across Chinese cities. To empirically test our hypotheses, we employ a fixed-effects model using data compiled from five major sources. Because city-level energy consumption data are not publicly available, we follow established methodologies and use nighttime light intensity data from NOAA as a proxy for energy consumption75,76. Official energy data, standardized in tons of standard coal, are drawn from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook to facilitate calculation and comparison. Additional control variables—including GDP, industrial structure, income levels, educational attainment, population density, and demographic composition—are extracted from the China City Statistical Yearbook. AI enterprise data are identified using a keyword extraction technique applied to the business scope descriptions listed in the Tianyancha enterprise database. Furthermore, green patent data sourced from CNIPA provide insight into the level of technological innovation. All continuous variables are logarithmically transformed to stabilize variance and normalize distributions. After data collection and preprocessing, the final dataset comprises 4177 observations spanning the years 2006 to 2020.

Model settings

Drawing on existing research, we employ a two-way fixed effects panel model to control for both individual (city-level) and time-specific effects25. This model offers significant advantages in handling complex panel data by effectively reducing omitted variable bias and enhancing the precision of causal inference. The baseline specification is as follows:

where i denote the city and t the year. The dependent variable, EE, represents energy efficiency, while the key explanatory variable, AI, captures the artificial intelligence development index. Control variables include population density, industrial structure, per capita GDP (pgdp), sulfur dioxide emissions (so2), and energy consumption. City and year fixed effects are denoted by \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{\text{i}}\) and \(\:{{\upgamma\:}}_{\text{t}}\) respectively.

Description of variables

Explained variable

Energy efficiency is a multifaceted concept with no universally accepted metric. Broadly, it refers to achieving the same level of output or service with reduced energy input—for example, using the ratio of energy consumption to GDP output as a proxy25. However, such single-factor indicators provide a limited, one-dimensional view that neglects interactions among multiple inputs and the presence of multiple outputs77,78.

These indicators typically focus solely on the energy–output relationship, overlooking the influence of other production factors such as labor and capital. To address this limitation, we adopt the CCR model within the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) framework, which evaluates relative efficiency using a non-parametric approach. This model incorporates a broader set of inputs—namely energy, labor, and capital—and a single output (GDP) to estimate each decision-making unit’s (DMU’s) position relative to a production frontier74. This methodology provides a holistic view of energy efficiency by comparing the performance of a DMU with peers that optimize input use for a given output or maximize output for a given level of input79. By integrating both technical and scale efficiency under the assumption of constant returns to scale80 the CCR model captures input–output interactions more comprehensively, providing a more accurate and holistic assessment of energy efficiency. Therefore, we construct our measure of energy efficiency using the CCR model rather than relying on single-factor indicators. For robustness checks, we further construct a measure of total factor energy efficiency using the SBM (Slack-Based Measure) model81,82,83.

Explanatory variable

Prior studies have commonly measured the level of AI development using two main approaches. The first relies on industrial robot data from the International Federation of Robotics (IFR)30,31,32,84,85. While widely used, this method offers only a partial view and fails to capture the full spectrum of AI applications. The second approach uses AI-related patent data as a proxy for AI development. As a direct reflection of technological innovation, patent data enables precise identification of AI-specific technologies and has been increasingly employed to assess technological advancement86,87. Nevertheless, the number of AI-related patents is often used as a proxy for the level of R&D activity and the cumulative technological achievements in the AI domain. However, when examining energy consumption, the number of AI enterprises may serve as a more direct and relevant indicator. This is because enterprise count reflects the degree of industrial agglomeration and the extent to which the AI sector has matured in a given city. A growing number of AI enterprises typically signals the translation of R&D efforts into real-world applications and market-driven innovations25,88. Therefore, compared to patent counts, the number of AI enterprises offers a more comprehensive measure of both innovation output and its practical implementation.

Mediating variables

Green technology innovation (GTI). At the city level, green technology innovation is measured by taking the natural logarithm of the number of green patent applications plus one, to account for the potential of zero values and to normalize the data89.

Industrial Structure Rationalization (ISR). Following prior research, this study adopts the Theil index to evaluate the rationalization of industrial structure by assessing both sectoral coordination and resource allocation efficiency62. The Theil index quantifies disparities in output and employment across sectors, capturing the extent of structural imbalance at the city level, as shown in Eq. (2):

In Eq. (2), TL denotes the Theil index, with Y and L representing total industrial output and labor force, respectively. Yi and Li refer to the output and employment of sector i, where i ranges from 1 to n, the total number of sectors. A lower Theil index approaching zero indicates a more rational industrial structure. This study calculates ISR for 284 cities over the period 2006–2020.

Moderating variables

Informal environment regulation (IER). To assess the moderating role of informal environmental regulation, the study employs a composite index constructed from indicators such as per capita income, population density, age structure, and educational attainment. These variables jointly capture the socio-economic conditions that influence public awareness and pressure for environmental protection, thus serving as proxies for informal regulatory mechanisms operating outside formal institutions.

To explore how informal environmental regulation moderates the impact, this research draws on the methodology of selecting a series of indicators such as income level, educational background, population density, and age structure to measure the extent of informal environmental regulation in cities90,91.

Stage of Resource City (SRC). Based on the National Resource-Based City Sustainable Development Plan (2013), resource-based cities are classified into four developmental stages: Growing, Mature, Declining, and Regenerating. In this study, these stages are numerically coded from 1 to 4, respectively, following the classification framework proposed by previous research70.

Control variables

In addition, we control for several variables commonly identified in the literature as influencing energy efficiency: (1) Population Density (density): Areas with higher population density often exhibit greater energy demand26. Population density is calculated based on the year-end total population57,92. (2) Industrial Structure (structure): This is measured by the share of tertiary industry value added in GDP, capturing the economic composition and its implications for energy use patterns. (3) GDP per Capita (pgdp): Reflecting regional economic development, GDP per capita is associated with higher living standards and greater awareness of sustainability concerns93. It is measured as the per capita GDP of urban residents. (4) Total Energy Consumption (energy): This variable captures the absolute scale of energy usage within a city, serving as a key control for evaluating energy efficiency94. (5) Environmental Pollution (so₂): Given that highly polluted regions often allocate more resources to environmental management, sulfur dioxide (so₂) emissions—one of the most prominent industrial pollutants—are used as a proxy for environmental pressure and are included as a control variable94; therefore, this study controls it, considering the environmental pollution status, and measures it by the amount of sulfur dioxide emissions.

Table 1 outlines the definitions and calculation methods of all variables.

Empirical analysis

Benchmark regression analysis

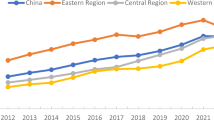

Due to the Hausman test results, with a p-value of 0.000, we choose the fixed effects model to control for unobserved individual heterogeneity. The analysis begins by examining the impact of AI development on energy efficiency (EE), with regression results presented in Table 2. Column (1) reports baseline estimates without control variables, while column (2) introduces controls. Column (3) further refines the model by clustering standard errors at both the city and calendar year levels to mitigate potential intra-group error correlation. The progressive increase in R-squared values across columns (1) through (3) indicates improved model fit with the inclusion of controls and robust error adjustments. In all specifications, the coefficient of AI on EE remains positive (0.049) and statistically significant at the 1% level, providing preliminary evidence that AI development positively influences energy efficiency.

Regarding the control variables, the coefficient on population density is positive and significant at the 1% level, suggesting that higher population density is associated with greater energy efficiency. This may be attributable to the intensified economic activity and more diversified industrial structures typically found in densely populated regions. Additionally, such regions often adopt stricter energy efficiency regulations, incentivizing firms to implement advanced energy-saving technologies. Likewise, the coefficient on per capita GDP is both positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating that higher income levels are linked to enhanced energy efficiency. This relationship likely reflects the increased capacity of wealthier regions to invest in technological innovation and R&D, along with heightened public awareness of environmental sustainability and energy conservation.

In contrast, the coefficients for so₂ emissions and total energy consumption are negative, implying that greater pollutant emissions and energy usage are detrimental to energy efficiency. These findings are consistent with empirical patterns observed in real-world contexts.

Robustness checks

Robustness test

To verify the robustness of these results, the study undertakes three validation approaches. First, it replaces the CCR model-derived measure of energy efficiency with a single-factor energy efficiency (EE) measure81. This shift allows us to assess energy efficiency through a more straightforward metric, calculated as the ratio of energy input to economic output10. Although this approach oversimplifies the multidimensional nature of energy performance, it aligns the analysis with conventional metrics frequently used in existing literature, enabling comparability across studies. As shown in column (1) of Table 3, the positive and significant relationship between AI development and EE persists, lending further credibility to the baseline findings.

Second, a subsample analysis is conducted to account for regional heterogeneity. The cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen—China’s leading megacities—exhibit advanced economic development, robust infrastructure, and strong capabilities in AI innovation, placing them well ahead of cities in central and western China, which face structural and infrastructural limitations. To mitigate potential bias introduced by these outliers, a regression is performed after excluding the four first-tier cities. The results, presented in Column (2) of Table 3, are consistent with those of the full sample, further reinforcing the robustness and generalizability of the core conclusions.

Third, the effects of AI development on energy efficiency may exhibit a time lag due to delays in policy interpretation and implementation. To account for this, we introduce one- and two-period lags of AI development as robustness checks, as shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 3, respectively. The results remain consistent with our baseline findings and provide further empirical support for Hypothesis 1, reaffirming that AI development is positively associated with improvements in urban energy efficiency.

Endogenous processing

To address potential endogeneity, we adopt an instrumental variable (IV) approach. Drawing on established methodologies in the literature, we construct two instruments: (1) a one-period lag of AI development, and (2) a Bartik shift-share instrument. The latter is derived by interacting the lagged first-order AI index with its first-order difference, thereby generating a theoretically grounded IV25,95,96. Table 4 presents the results of the IV regressions, which include the same set of control variables used in the baseline model to mitigate confounding effects. The results demonstrate that AI remains positively and significantly associated with energy efficiency under both IV strategies. Specifically, columns (1) and (3) report the first-stage regression outcomes, confirming a strong correlation between the instruments (IV1 and IV2) and AI. Columns (2) and (4) show the second-stage estimates, where the coefficients on AI are 0.051 and 0.049, respectively, both significant at the 1% level. These findings confirm the robustness and consistency of the main regression results.

Mechanism test

Green technology innovation

Table 5 reports the mediating role of green technological innovation (GTI) in the AI–energy efficiency relationship. Column (1) presents the total effect of AI on energy efficiency, while column (2) shows that AI significantly promotes GTI at the 1% level. This suggests that AI development exerts a substantial and positive influence on the advancement of green technologies, underscoring its capacity to catalyze sustainable innovation. In column (3), when both AI and GTI are regressed on energy efficiency, the coefficient for GTI remains positive and statistically significant at the 5% level. This indicates that GTI contributes to enhancing energy efficiency and functions as a partial mediator. The clustering of AI enterprises appears to foster green innovation, which in turn drives improvements in energy efficiency. These results support Hypothesis 2 regarding the mediating role of GTI.

Rationalization of industrial structure

Table 6 presents the mediating mechanism analysis involving the rationalization of the industrial structure (ISR). Column (1) shows the total effect of AI on energy efficiency, while column (2) reveals that AI significantly promotes ISR at the 1% level, suggesting that AI contributes to industrial upgrading and structural optimization. In column (3), when AI and ISR are jointly regressed on energy efficiency, both variables show positive and statistically significant coefficients at the 1% level. These findings indicate that ISR serves as a significant mediating pathway through which AI enhances energy efficiency. Thus, the results provide empirical support for Hypothesis 3, confirming that AI facilitates energy efficiency improvements by driving the rationalization of the industrial structure.

Further analysis

After establishing the fundamental connection between artificial intelligence (AI) development and energy efficiency, this study proceeds to examine the nuanced dynamics of this relationship under varying boundary conditions97. Specifically, we investigate how environmental regulations and the developmental stage of resource-based cities moderate the impact of AI on energy efficiency. This focus is grounded in the recognition that environmental regulation significantly shapes the technological and operational landscape of cities57. Previous research suggests that technological innovation tends to be more effective in regions with stringent environmental oversight60. Likewise, the economic trajectory of resource-based cities—categorized as growing, mature, declining, or regenerative—is closely tied to the energy sector, and each stage exhibits distinct characteristics56. These structural differences create divergent incentives and capacities for integrating AI to enhance energy efficiency. By exploring these moderating factors, we aim to refine our understanding of the contextual conditions under which AI contributes most effectively to energy efficiency.

Moderate role of informal environment regulation

We begin by analyzing the role of informal environmental regulation (IER). Table 7, column (1), presents the moderating effects of IER on the relationship between AI development and energy efficiency. The interaction term between IER and AI development is both positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that AI’s impact on energy efficiency is more pronounced in areas with strong informal regulatory mechanisms. These findings support Hypothesis 4.

Moderate role of the stage of resource development

Next, we consider how the developmental stage of resource-based cities influences the effectiveness of AI in improving energy efficiency. Our analysis reveals that AI exerts a stronger positive effect in declining and regenerative cities compared to growing and mature ones, likely due to their heightened need for transformation and greater potential for system optimization. In Table 7, column (2), the moderation analysis indicates that mature cities are less energy efficient than growing cities, with declining and regenerative cities performing even worse. However, the interaction term between AI and mature cities is not statistically significant, suggesting no meaningful difference in AI’s impact on energy efficiency between mature and growing cities. In contrast, the significantly positive interaction terms for declining and regenerative cities indicate a more substantial effect of AI in these contexts. This may reflect the targeted application of AI technologies to enhance efficiency amid resource depletion in declining cities, and to optimize energy management in regenerative cities transitioning from historical resource dependency. These results empirically validate our assumption that AI’s contribution to energy efficiency varies across different stages of resource-based urban development.

Conclusion and implication

Conclusion

Amid growing global emphasis on sustainable development, the role of AI in advancing energy efficiency has garnered considerable attention from both policymakers and researchers. This study assesses the extent to which AI development facilitates sustainable practices in China, particularly in the energy domain. Three key findings emerge from our analysis. First, AI development positively influences energy efficiency. Second, this effect operates primarily through two channels: green innovation and industrial structure rationalization. Specifically, AI promotes the development and deployment of green technologies while also enabling a more balanced and efficient allocation of industrial resources. Third, the moderating analysis reveals that AI’s impact on energy efficiency is significantly amplified in cities with strong informal environmental regulations, and is comparatively muted in cities with looser regulatory environments. Additionally, AI has proven particularly effective in enhancing energy efficiency in resource-based cities that are either in decline or undergoing regeneration, relative to their growing or mature counterparts. Our study’s results align with existing research, emphasizing the significant impact of AI on energy efficiency. By comparing our findings with other studies, we have identified the mechanisms through which AI affects energy efficiency and the conditions under which these effects are most pronounced. This comparison not only validates our results but also highlights the unique contributions of our study.

These findings contribute significantly to the scientific understanding of AI’s role in sustainable development by offering empirical evidence of its impact on energy efficiency. By elucidating the mechanisms linking AI to energy efficiency, our research provides critical insights for policymakers and industry stakeholders, underscoring the importance of incorporating AI into strategic frameworks to advance sustainable development. The practical implications are particularly salient for China, given its energy scarcity and uneven resource distribution. In light of China’s ambitious targets to peak CO₂ emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, harnessing AI to enhance energy efficiency and drive industrial transformation in resource-based cities is imperative. This strategy not only facilitates the attainment of domestic sustainability goals but also strengthens China’s position as a global leader in sustainable development.

Policy implication

Based on the above findings, several key policy implications emerge for promoting sustainable development through AI adoption. First, the positive impact of AI on energy efficiency is significantly amplified in cities with robust informal environmental regulations. Policymakers should therefore prioritize the reinforcement of environmental governance by implementing formal regulations, enhancing public awareness, supporting environmental NGOs, and cultivating a culture of sustainability at the community level. Second, AI exerts a stronger influence on energy efficiency in declining and regenerating resource-dependent cities. Targeted investments in AI infrastructure and applications during these critical transition stages can support industrial restructuring. Simultaneously, efforts should be made to cultivate conducive environments for AI adoption in growing and mature cities. Early integration of AI technologies in these areas can yield long-term benefits by embedding sustainable practices and mitigating future transition risks. Third, AI enhances energy efficiency primarily through green technological innovation and industrial structure optimization. Policymakers and industry leaders should leverage AI to drive innovation and streamline industrial operations, thereby promoting sustainability and unlocking the full potential of AI-driven transformation.

Limitations and future research

Our analysis is based on data from China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or developed countries. Future research should incorporate cross-national datasets to validate and expand upon our conclusions, enabling a broader understanding of AI’s role in global energy efficiency improvements. Furthermore, this study does not delve into the differential impacts of various AI subtypes. For instance, generative AI may present unique implications worth exploring in greater depth in subsequent research.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Caglar, A. E., Gönenç, S. & Destek, M. A. Toward a sustainable environment within the framework of carbon neutrality scenarios: evidence from the novel Fourier-NARD approach. Sustain. Dev. 32, 6643–6655 (2024).

Caglar, A. E., Daştan, M., Ahmed, Z., Mert, M. & Avci, S. B. The synergy of renewable energy consumption, green technology, and environmental quality: designing < scp > sustainable development goals policies. Nat. Resour. Forum. (2024).

Wang, C. H. & Juo, W. An environmental policy of green intellectual capital: green innovation strategy for performance sustainability. Bus. Strat Env. 30, 3241–3254 (2021).

D’Adamo, I., Di Carlo, C., Gastaldi, M., Rossi, E. N. & Uricchio, A. F. Economic performance, environmental protection and social progress: A cluster analysis comparison towards sustainable development. Sustain. (Switz). 16, 5049–5049 (2024).

Ali, I., Rahaman, A., Ali, M. J. & Rahman, F. The growth–environment nexus amid geopolitical risks: cointegration and machine learning algorithm approaches. Discov. Sustain. 6, (2025).

Caglar, A. E., Daştan, M., Ahmed, Z., Mert, M. & Avci, S. B. A novel panel of European economies pursuing carbon neutrality: do current climate technology and renewable energy practices really pass through the Prism of sustainable development? Gondwana. Res. (2025).

Rasoulinezhad, E. & Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Role of green finance in improving energy efficiency and renewable energy development. Energy Effic. 15, (2022).

Lee, C. C. & Lee, C. C. How does green finance affect green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 107, 105863 (2022).

Wang, J. & Hao, S. The Spatial impact of carbon trading on harmonious economic and environmental development: evidence from China. Environ. Geochem. Health. 45, 6495–6515 (2023).

Hong, Q., Cui, L. & Hong, P. The impact of carbon emissions trading on energy efficiency: evidence from quasi-experiment in china’s carbon emissions trading pilot. Energy Econ. 110, 106025–106025 (2022).

Chen, Z., Song, P. & Wang, B. Carbon emissions trading scheme, energy efficiency and rebound effect – Evidence from china’s provincial data. Energy Policy. 157, 112507–112507 (2021).

Song, M., Du, J. & Tan, K. H. Impact of fiscal decentralization on green total factor productivity. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 205, 359–367 (2018).

Liu, J., Cheng, Z. & Zhang, H. Does industrial agglomeration promote the increase of energy efficiency in china?? J. Clean. Prod. 164, 30–37 (2017).

Yuan, H., Feng, Y., Lee, C. C. & Cen, Y. How does manufacturing agglomeration affect green economic efficiency? Energy Econ. 92, 104944 (2020).

Ali, I., Islam, M. & Ceh, B. Assessing the impact of three emission (3E) parameters on environmental quality in canada: A provincial data analysis using the quantiles via moments approach. Int. J. Green. Energy. 1–19. (2024).

Jianda, W., Kangyin, D., Xiucheng, D. & Farhad, T. H. Assessing the digital economy and its carbon-mitigation effects: the case of China. Energy Econ. 113, (2022).

Rinku, N., Singh, N. G., Artificial intelligence in sustainable energy industry: status quo, challenges, and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 289, 234–237 (2023).

Viskovic, A., Franki, V. & Jevtic, D. Artificial Intelligence as a facilitator of the energy transition. In international convention on information and communication technology. Electron. Microelectron. 494–499. (2022).

Xue, Y., Tang, C., Wu, H., Liu, J. & Hao, Y. The emerging driving force of energy consumption in china: does digital economy development matter? Energy Policy. 165, 112997 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Artificial intelligence powered large-scale renewable integrations in multi-energy systems for carbon neutrality transition: challenges and future perspectives. Energy AI. 10, 100195–100195 (2022).

Hussain, M., Yang, S., Maqsood, U. S. & Zahid, R. M. A. Tapping into the green potential: the power of artificial intelligence adoption in corporate green innovation drive. Bus. Strat Env. 33, 4375–4396 (2024).

Farzaneh, H. et al. Artificial intelligence evolution in smart buildings for energy efficiency. Appl. Sci. 11, 763 (2021).

Shahbaz, M., Wang, J., Dong, K. & Zhao, J. The impact of digital economy on energy transition across the globe: the mediating role of government governance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 166, 112620–112620 (2022).

Yi, M., Liu, Y., Sheng, M. S. & Wen, L. Effects of digital economy on carbon emission reduction: new evidence from China. Energy Policy. 171, 113271 (2022).

Li, X., Li, S., Cao, J. & Spulbar, A. C. Does artificial intelligence improve energy efficiency? Evidence from provincial data in China. Energy Econ. 108149–108149. (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Digital economy, energy efficiency, and carbon emissions: evidence from provincial panel data in China. Sci. Total Environ. 852, 158403–158403 (2022).

Cioffi, R., Travaglioni, M., Piscitelli, G., Petrillo, A. & De Felice, F. Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications in smart production: progress, trends, and directions. Sustain. (Switz). 12, 492 (2020).

Wei, W. et al. Embodied greenhouse gas emissions from Building china’s large-scale power transmission infrastructure. Nat. Sustain. 4, 739–747 (2021).

Dong, K., Sun, R., Hochman, G. & Li, H. Energy intensity and energy conservation potential in china: A regional comparison perspective. Energy 155, 782–795 (2018).

Du, L. & Lin, W. Does the application of industrial robots overcome the Solow paradox? Evidence from China. Technol. Soc. 68, 101932 (2022).

Cheng, H., Jia, R., Li, D. & Li, H. The rise of robots in China. J. Econ. Perspect. 33, 71–88 (2019).

Tao, W., Weng, S., Chen, X., ALHussan, F. B. & Song, M. Artificial intelligence-driven transformations in low-carbon energy structure: evidence from China. Energy Econ. 136, 107719 (2024).

Caglar, A. E., Avci, S. B., Gökçe, N. & Destek, M. A. A sustainable study of competitive industrial performance amidst environmental quality: new insight from novel fourier perspective. J. Environ. Manage. 366, 121843 (2024).

Lu, J. & Li, H. Can digital technology innovation promote total factor energy efficiency? Firm-level evidence from China. Energy 293, 130682–130682 (2024).

Luo, S. et al. Digitalization and sustainable development: how could digital economy development improve green innovation in china?? Bus. Strat Environ. 32, 1847–1871 (2023).

Pan, W., Xie, T., Wang, Z. & Ma, L. Digital economy: an innovation driver for total factor productivity. J. Bus. Res. 139, 303–311 (2022).

Lyu, Y., Wang, W., Wu, Y. & Zhang, J. How does digital economy affect green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 857, 159428 (2023).

Hanafizadeh, P. & Nik, M. R. H. Configuration of data monetization: A review of literature with thematic analysis. Glob J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 21, 17–34 (2019).

Jackson, I., Ivanov, D., Dolgui, A. & Namdar, J. Generative artificial intelligence in supply chain and operations management: a capability-based framework for analysis and implementation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 62, 6120–6145 (2024).

Mitra, R., Saha, P. & Kumar Tiwari, M. Sales forecasting of a food and beverage company using deep clustering frameworks. Int. J. Prod. Res. 62, 3320–3332 (2023).

Wu, J., Zhang, Z. & Zhou, S. X. Credit rating prediction through supply chains: A machine learning approach. Prod. Oper. Manag. 31, 1613–1629 (2022).

Chien, C. F., Lin, Y. S. & Lin, S. K. Deep reinforcement learning for selecting demand forecast models to empower industry 3.5 and an empirical study for a semiconductor component distributor. Int. J. Prod. Res. 58, 2784–2804 (2020).

Brooks, R. A. Intelligence without representation. Artif. Intell. 47, 139–159 (1991).

Raees, N. The effect of ventilation and economizer on energy consumptions for air source heat pumps in schools. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 7, 58–65 (2014).

Zhu, S. et al. Intelligent computing: the latest advances, challenges, and future. Intell. Comput. 2, (2023).

Liu, J., Qian, Y., Yang, Y. & Yang, Z. Can artificial intelligence improve the energy efficiency of manufacturing companies? Evidence from China. IJERPH 19 (2022).

Li, P., Yang, J., Islam, M. A., Ren, S. Making AI less ‘Thirsty’: Uncovering and addressing the secret water footprint of AI models. arXiv 2304.03271 (2023).

Zhou, X., Zhou, D., Wang, Q. & Su, B. How information and communication technology drives carbon emissions: A sector-level analysis for China. Energy Econ. 81, 380–392 (2019).

Li, Z. & Wang, J. The dynamic impact of digital economy on carbon emission reduction: evidence City-level empirical data in China. J. Clean. Prod. 351, 131570–131570 (2022).

Diamantoulakis, P. D., Kapinas, V. M. & Karagiannidis, G. K. Big data analytics for dynamic energy management in smart grids. Big Data Res. 2, 94–101 (2015).

Pawanr, S. & Gupta, K. A. Review on recent advances in the energy efficiency of machining processes for sustainability. Energies 17, 3659–3659 (2024).

Balakrishnan, D., Sharma, P., Bora, B. J. & Dizge, N. Harnessing biomass energy: advancements through machine learning and AI applications for sustainability and efficiency. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 191, 193–205 (2024).

Mahmood, S. et al. Integrating machine and deep learning technologies in green buildings for enhanced energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. Sci. Rep. 14, (2024).

Villarreal, J. A. S., Mendoza, V. S., Acosta, J. A. N. & Ruiz, E. R. Energy consumption outlier detection with AI models in modern cities: a case study from north-eastern Mexico. Algorithms 17, 322–322 (2024).

Wang, E. Z., Lee, C. C. & Li, Y. Assessing the impact of industrial robots on manufacturing energy intensity in 38 countries. Energy Econ. 105, 105748 (2022).

Lin, B. & Xu, C. The effects of industrial robots on firm energy intensity: from the perspective of technological innovation and electrification. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 203, 123373–123373 (2024).

Wang, Y., Zhao, W. & Ma, X. The Spatial spillover impact of artificial intelligence on energy efficiency: empirical evidence from 278 Chinese cities. Energy 312, 133497 (2024).

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D., Dorn, D., Hanson, G. H. & Price, B. Return of the Solow paradox?? IT, productivity, and employment in US manufacturing. am. Econ. Rev. 104, 394–399 (2014).

Barbieri, N., Marzucchi, A. & Rizzo, U. Knowledge sources and impacts on subsequent inventions: do green technologies differ from non-green ones? Res. Policy. 49, 103901–103901 (2019).

Ouyang, X., Li, Q. & Du, K. How does environmental regulation promote technological innovations in the industrial sector? Evidence from Chinese provincial panel data. Energy Policy. 139, 111310–111310 (2020).

Jenne, C. A. & Cattell, R. K. Structural change and energy efficiency in industry. Energy Econ. 5, 114–123 (1983).

Hu, L., Yuan, W., Jiang, J., Ma, T. & Zhu, S. Asymmetric effects of industrial structure rationalization on carbon emissions: evidence from Thirty Chinese provinces. J. Clean. Prod. 428, 139347–139347 (2023).

Xue, L. et al. Impacts of industrial structure adjustment, upgrade and coordination on energy efficiency: empirical research based on the extended STIRPAT model. Energy Strategy Rev. 43, 100911 (2022).

Li, B., Jiang, F., Xia, H. & Pan, J. Under the background of AI application, research on the impact of science and technology innovation and industrial structure upgrading on the sustainable and High-Quality development of regional economies. Sustain. (Switz). 14, 11331 (2022).

Su, Y. & Fan, Q. Renewable energy technology innovation, industrial structure upgrading and green development from the perspective of china’s provinces. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 180, 121727–121727 (2022).

Du, K., Cheng, Y. & Yao, X. Environmental regulation, green technology innovation, and industrial structure upgrading: the road to the green transformation of Chinese cities. Energy Econ. 98, 105247–105247 (2021).

Yu, H. et al. How does green technology innovation influence industrial structure? Evidence of heterogeneous environmental regulation effects. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26, 17875–17903 (2023).

Peng, H., Shen, N., Ying, H. & Wang, Q. Can environmental regulation directly promote green innovation behavior?—— based on situation of industrial agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 314, 128044 (2021).

Chen, L., Li, W., Yuan, K. & Zhang, X. Can informal environmental regulation promote industrial structure upgrading? Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. 54, 2161–2180 (2021).

Huang, S. & Ge, J. Are there heterogeneities in environmental risks among different types of resource-based cities in china?? Assessment based on environmental risk field approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 104810–104810. (2024).

Wang, K., Chen, X. & Wang, C. The impact of sustainable development planning in resource-based cities on corporate ESG–Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 127, 107087 (2023).

Jiang, Z., Yuan, C. & Xu, J. The impact of digital government on energy sustainability: empirical evidence from prefecture-level cities in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 209, 123776–123776 (2024).

Lu, S., Zhang, W., Yu, J. & Li, J. The identification of spatial evolution stage of resource-based cities and its development characteristics. Acta Geogr. Sin. 75 2180–2191 (2020).

Wang, L. & Shao, J. Digital economy, entrepreneurship and energy efficiency. Energy 269, 126801–126801 (2023).

Wu, Y., Shi, K., Chen, Z., Liu, S. & Chang, Z. Developing improved Time-Series DMSP-OLS-Like data (1992–2019) in China by integrating DMSP-OLS and SNPP-VIIRS. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–14 (2021).

Lin, Y. & Cheung, A. Climate policy uncertainty and energy transition: evidence from prefecture-level cities in China. Energy Econ. 107938–107938 (2024).

Renshaw, E. F. Energy efficiency and the slump in labour productivity in the USA. Energy Econ. 3, 36–42 (1981).

Wilson, B., Trieu, L. H. & Bowen, B. Energy efficiency trends in Australia. Energy Policy. 22, 287–295 (1994).

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W. & Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2, 429–444 (1978).

Li, M. J. & Tao, W. Q. Review of methodologies and Polices for evaluation of energy efficiency in high energy-consuming industry. Appl. Energy. 187, 203–215 (2017).

Muhammad, S., Pan, Y., Agha, M. H., Umar, M. & Chen, S. Industrial structure, energy intensity and environmental efficiency across developed and developing economies: the intermediary role of primary, secondary and tertiary industry. Energy 247, 123576–123576 (2022).

Tone, K. A strange case of the cost and allocative efficiencies in DEA. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 53, 1225–1231 (2002).

Tone, K. A slacks-based measure of super-efficiency in data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 143, 32–41 (2002).

Acemoglu, D. & Restrepo, P. Robots and jobs: evidence from US labor markets. J. Political Econ. 128, 2188–2244 (2020).

Beaudry, P., Doms, M. & Lewis, E. Should the personal computer be considered a technological revolution?? Evidence from U.S. Metropolitan areas. J. Polit. Econ. 118, 988–1036 (2010).

Mann, K. & Püttmann, L. Benign effects of automation: new evidence from patent texts. Rev. Econ. Stat. 105, 562–579 (2021).

Autor, D., Chin, C., Salomons, A. & Seegmiller, B. New frontiers: the origins and content of new work, 1940–2018. Q. J. Econ. 139, 1399–1465 (2024).

Henderson, J. V. Marshall’s scale economies. J. Urban Econ. 53, 1–28 (2003).

Xiong, M., Li, W., Xian, B. T. S. & Yang, A. Digital inclusive finance and enterprise innovation—Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies. J. Innov. Knowl. 8, 100321 (2023).

Kathuria, V. Informal regulation of pollution in a developing country: evidence from India. Ecol. Econ. 63, 403–417 (2007).

Pargal, S. & Wheeler, D. Informal regulation of industrial pollution in developing countries: evidence from Indonesia. J. Political Econ. 104, 1314–1327 (1996).

Jia, R., Shao, S. & Yang, L. High-speed rail and CO2 emissions in urban china: A Spatial difference-in-differences approach. Energy Econ. 99, 105271–105271 (2021).

Luan, F., Yang, X., Chen, Y. & Regis, P. J. Industrial robots and air environment: A moderated mediation model of population density and energy consumption. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 30, 870–888 (2022).

Shi, D. & Li, S. Emissions trading system and energy use efficiency: Measurements and empirical evidence for cities at and above the prefecture level. China Industrial Economics 5–23 (2020).

Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., Sorkin, I. & Swift, H. Bartik instruments: what, when, why, and how. am. Econ. Rev. 110, 2586–2624 (2020).

Borusyak, K., Hull, P. & Jaravel, X. Quasi-experimental shift-share research designs. Rev. Econ. Stud. 89, 181–213 (2021).

Lee, C. C., Fang, Y., Quan, S. & Li, X. Leveraging the power of artificial intelligence toward the energy transition: the key role of the digital economy. Energy Econ. 135, 107654 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [NO. 71972137]; the Projects of Philosophy and Social Sciences Research of Chinese Ministry of Education [NO. 23YJA790075]; the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province Project [NO. 2023JDR0296]; Chengdu Philosophy and Social Science Research Projects [NO.2024BZ168]; the Sichuan Key Industries Development Series Research Project [NO. 2025XL15].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jun Zeng and Tian Wang designed the study, drafted the article, acquired the data, completed the analysis, critical revision for important intellectual content together.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, J., Wang, T. The impact of China’s artificial intelligence development on urban energy efficiency. Sci Rep 15, 24129 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09319-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09319-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Unpacking the mechanisms and consequences of artificial intelligence in enabling green value co-creation for SMEs

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The pathway to enhancing energy efficiency: Is artificial intelligence important?

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2025)