Abstract

Spasticity is defined as the velocity-dependent hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex that develops after a central nervous system injury. Spasticity is caused by plastic neuronal changes following injury. Current treatments that block spastic muscle contractions do not promote recovery from motor dysfunction. We aimed to confirm that Ia fibre activity suppression, comprising the stretch reflex, reduces spasticity-related hyperreflexia and improves pathological neuronal plastic changes and motor dysfunction. In this study, we created a hemi-transected spinal cord injury mouse model and continued Ia fibre suppression for 2 weeks. The effects of Ia fibre suppression were evaluated electrophysiologically and histologically. In electrophysiology, spasticity-related rate-dependent depression of Hoffman’s reflex improved from 0.6 to 0.2 in terms of the rate of amplitude change with reference to 0.1 Hz electrical stimulation. Histologically, the number of synapse buttons of Ia fibres per an α motor neuron reduced from 4.2 to 2.6. However, the α motor neuron activity was still higher than that in the sham mice, possibly due to other residual pathological mechanisms of spasticity. Additionally, motor dysfunction was observed in grid walk and single-reach tasks in vehicle- and drug-administered groups. This study confirmed that continuous Ia fibre suppression partly improved the maladaptive synaptic connections in the spinal cord and relieved spasticity-related hyperreflexia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spasticity is the velocity-dependent hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex of skeletal muscles, Ia fibres, and α motor neurons1,2. Neuronal plastic changes after central nervous system (CNS) injuries, such as stroke or spinal cord injury (SCI), cause spasticity. One main symptom of spasticity is involuntary muscle contraction associated with the hyperreflexia of the spinal stretch reflex, which also inhibits motor function recovery. Approximately 40% of individuals with SCI suffer from spasticity3. Several treatments are available for spasticity, but they have limitations. For example, the active movement inhibition due to the suppression of α motor neuronal activity and the atrophy of the muscles to which botulinum toxin is administered4. Further, the current treatments target symptomatic pain and limit the joint motion range during the chronic phase. During this phase, neuroplastic changes are complete and enhance the abnormal neural networks. Radically recovering motor function during the chronic phase is challenging. Therefore, establishing a new treatment strategy for the acute phase after CNS injury that aims to recover motor function is necessary.

It has long been suggested that abnormal sensory input is associated with spasticity and spinal neural circuits5. In the present study, we focused on Ia fibres, which have monosynaptic connections with α motor neuron in the spinal stretch reflex arch, which is also the definition of spasticity. Ia fibres are proprioceptive sensory neurons. They connect to the muscle spindle and transduce dynamic and static components such as changes in muscle length and stretch velocity. Then, they transmit action potentials to the spinal cord. Regarding the relationship between Ia fibre and spasticity, previous studies reported that axonal Ia fibre sprouting projecting to the α motor neurons increases with spasticity in animal models6,7. Furthermore, presynaptic inhibitory neurons in the spinal cord adjust the gain of Ia fibres. However, this adjustment of Ia fibre axonal endings is masked or reduced by spasticity after SCI8. Excessive excitability input from the Ia fibres to α motor neurons may induce an increase in axonal Ia sprouting. Additionally, spasticity may lead to excessive input to Ia fibre neurons because hyperexcitation of the stretch reflex induces longitudinal changes and stretch velocity in the muscle.

Furthermore, Ia fibres project not only α motor neurons but also propriospinal neurons, which project ascending pathways and α motor neurons9. Notably, the abnormal activity of these propriospinal neurons is associated with spasticity10,11. Moreover, one of the propriospinal neurons receives excitatory input from Ia fibre and is associated with skilled movement12,13. Taken together, it is speculated that the abnormal sensory input confirmed during spasticity is related to spasticity mechanisms and resulting motor dysfunction. Therefore, regulation of abnormal sensory input is essential; however, there are no studies about the suppression of Ia fibre activity for spasticity intervention.

The Ia fibre mechanosensory endings in the muscle spindle has several mechanosensory channels carrying Na+ and Ca2+ currents, such as degenerin/epithelial sodium channels (DEG/ENaC) and acid-sensitive ion channels (ASICs)14. Additionally, synaptic-like vesicles (SLVs) have been discovered in mechanosensory endings and confirmed to be vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (vGluT1), which contains glutamate15. This receptor is known as mGluR, and it is coupled with phospholipase D activation (PLD-mGluR) in the mechanosensory endings. The spindle responsiveness is maintained and increased by a positive gain-control system, whereby these vesicles release glutamate in a Ca2+-dependent manner to activate the PLD-mGluR receptor16,17. We focused on PLD-mGluRs at the Ia fibre mechanosensory ending to suppress their activity16,17,18. This receptor is expressed in the spindle mechanosensory terminals and the lanceolate palisade ends of the hair follicle19. This function of PLD-mGluR, a homomeric GluK2 kainate receptor20, is blocked by the administration of (R,S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), which is a PLD-mGluR antagonist18. DHPG is a very unique drug because it suppresses Ia fibre activity partially by inhibiting to combine with glutamate. Therefore, we hypothesised that the moderation of Ia fibre activity reduces excitatory input from Ia fibres to α motor neurons in the spinal stretch reflex arch and contributes to the reduction of spasticity. In this study, we aimed to confirm that continuous Ia fibre activity suppression using DHPG can induce spinal neural network normalisation and reduce spasticity.

Results

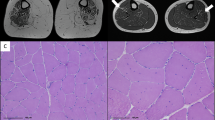

Area and lesion volume in the SCI mouse model

We outlined the lesion area in a photograph of the sample, including the vertebrae and used a microscope to confirm the area and spinal level of the lesion (Fig. 1A–C). The lesion area was detected between the fourth and sixth vertebral arches and did not markedly cross the midline. The lesion volume was measured in a sagittal section series using Kluber–Barrera staining for myelin and Nissl substances. In the sham group, the differences between the white and grey matter were clear, and the cells in the grey matter were arranged orderly (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the white and grey matter were interrupted in SCI mice. Furthermore, the relatively large cells in the sham group were replaced with small cells at the lesion site (Fig. 1C, dotted line). The mean lesion volume was 1.17 ± 0.06 mm3 at 4 weeks post-SCI. The difference in lesion volume was not significant in the SCI vehicles, which were administered with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), or SCI-DHPG (Fig. 1D, vehicle: 1.11 ± 0.06 mm3, DHPG: 1.22 ± 0.12 mm3).

Area and volume of spinal injury (SCI) in the vehicle and (R,S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) groups. (A) Illustration of the injury traces in all mice in spinal cords 4 weeks after spinal cord injury. Dotted lines indicate that C4, C6 and C7 are the 4th, 6th and 7th of the cervical vertebral arches, respectively. (B,C) Luxol fast blue staining in the sagittal section of the spinal cord in the sham (B) and SCI groups (C). Blue represents myelinated fibres and blue-violet represents neural and glial cells. The white dotted line in C indicates the lesion area. (D) Graph of the lesion volume 4 weeks after SCI. Data are shown as box plots. The notches on (under) the box plots indicate the maximum (minimum) values for each group. The centreline of each box represents the median, and the x-mark represents the average. SCI-vehicle, n = 8; SCI-DHPG, n = 8. Shapiro–Wilk test, Student’s t-test. n.s. = not significant.

Electrophysiological spasticity assessment

Herein, the Hoffman’s reflex (H-reflex) was monitored at the right forelimb digiti minimi muscle (Fig. 2A). The H-reflex latency (6–8 ms) was longer than the M-wave latency (2–4 ms) (Fig. 2B,C). Under healthy conditions, we observed a decrease in the H-reflex amplitude (Rate Dependent Depression [RDD]) following high-frequency (5 Hz) stimulation (Fig. 2B,D). The H-reflex RDD did not weaken with spasticity after SCI (Fig. 2C,D). The RDD of the H-reflexes at 1-week post-SCI was significantly weakened relative to that in the sham mice (p < 0.001; 1, 2, and 5 Hz; Fig. 2D).

Confirming spasticity using Hoffman’s reflex(H-reflex) Rate Dependent Depression (RDD). (A) Illustration of methods for Hoffman’s reflex. Recording electrodes were inserted to right forelimb abductor digiti minimi muscle, and recorded electromyogram after stimulation of ulnar nerve. (B,C) Raw data of M wave and H-reflex. Black lines are waves when 0.1 Hz stimulation, and red lines are ones when 5 Hz stimulation. (D) Graph of H-reflex’s change in depression comparing sham and the spinal cord injury (SCI) 1 week after establishing SCI model. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. sham n = 13 SCI n = 18. Shapiro–Wilk test, ANOVA, Tukey–Kramer (***p < 0.001).

Reappearance of H-reflex RDDs due to continuous DHPG administration

Herein, we investigated whether continuous administration of DHPG, a competitive antagonist of PLD-mGluR in Ia fibre mechanosensory endings, for 2 weeks from 1-week post-SCI led to reconfirmation of RDDs of the H-reflex (Fig. 3A). First, we checked the suppression of Ia activation through a one-shot DHPG administration in the muscle using an extracellular electrogram (Supplementary Fig. S1A–D). Next, we confirmed the delivery of the drug solution, including indocyanine green (ICG), which reacts to near-infrared light, from the osmotic pump to the right abductor digiti minimi muscle using a tube and spread it around (Supplementary Fig. S2).

(R,S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) group reappear Hoffman’s reflex (H-reflex) Rate Dependent Depression (RDD). (A) Scheme of experience schedule. Drugs were administered for 2 weeks at 1w post-spinal cord injury (SCI). (B,C) Graph of H-reflex’s change in depression comparing SCI-vehicle (blue) and SCI-DHPG (red). SCI-vehicle n = 9, SCI-DHPG n = 9. (D,E) Graph of H-reflex’s change in depression comparing pre-SCI (D,E, white), SCI-vehicle (D, blue), and SCI-DHPG (E, red). Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. Pre-SCI n = 18, each drug group n = 9. Shapiro–Wilk test, ANOVA, Tukey–Kramer (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

At 2- and 4-week post-SCI, the H-reflex RDD in the SCI-DHPG mice was significantly higher than that in the SCI-vehicle mice (2-week: p < 0.01; 1, 2 Hz, p < 0.001; 5 Hz, 4-week: p < 0.001, 2, 5 Hz; Fig. 3B,C). The H-reflex RDD in the SCI-DHPG mice was extremely attenuated under high-frequency stimulation (5 Hz) at 2 and 4 weeks after SCI; however, it did not return to normal. Compared with pre-SCI, the H-reflex RDDs were substantially weakened in the SCI-vehicle and SCI-DHPG mice each week (Fig. 3D,E). Herein, we did not confirm a substantial negative effect of DHPG administration on the H-reflex of sham mice (sham-DHPG) relative to the sham-vehicle mice (Supplementary Fig. S3).

DHPG administration did not affect motor function recovery after SCI

For the grid walk test, the SCI mice administered each drug demonstrated slow recovery 3 days after SCI (Fig. 4). No marked difference in recovery was observed between the SCI-DHPG and pre-administration mice. The single pellet reach task may have been extremely challenging for the SCI mice, and no dynamic recovery was observed in SCI-vehicle or SCI-DHPG mice. From the qualitative assessment viewpoint, the SCI-vehicle mice exhibited a phased recovery of the hand joint (Data not shown). However, the SCI-DHPG mice did not, and their recovery appeared to plateau or slightly decline. The significantly negative effect of Ia suppression on sham-DHPG mice was not confirmed.

(R,S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) administration didn’t affect motor function recovery. (A) Ratio of success step during grid walk test. The ratio was calculated by success steps in all steps. A success step was defined as the right forelimb step without dropping. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. sham-vehicle n = 3, sham-DHPG n = 3, spinal cord injury (SCI)-vehicle n = 5, SCI-DHPG n = 5. Shapiro–Wilk, Kruskal–Wallis, Steel–Dwass (***p < 0.001: vs SCI-DHPG, ###p < 0.001: vs SCI-vehicle). (B) Success ratio of single pellet reach task. The ratio was calculated using the number of that mice could grasp and eat pellets in 30 times. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. sham-vehicle n = 3, sham-DHPG n = 3, SCI-vehicle n = 5, SCI-DHPG n = 5. Shapiro–Wilk test, Kruskal–Wallis, Steel–Dwass (***p < 0.001: vs SCI-DHPG, ###p < 0.001: vs SCI-vehicle).

Functional assessment of free walking using three-dimensional motion analysis revealed that none of the drugs administered inhibited recovery of functions that supported walking, such as swing speed or clearance, and slow improvement was observed after administration. Substantial recovery was not observed after DHPG administration (Data not shown).

Ia-α synaptic connection returns to normal because of DHPG administration after SCI

Subsequently, we confirmed whether the number of synaptic connections between the Ia fibres and α motor neurons (Ia-α connections) was altered post-SCI after DHPG administration. The Ia-α connections were detected using laser microscope Z-stack imaging, with the positive regions of the vGluT1 considered as the Ia fibre axonal terminals and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) considered as the α motor neuron (Fig. 5A–P). The number of Ia-α synaptic connections in the SCI-DHPG mice was markedly less than those in the SCI-vehicle mice (SCI-vehicle; 4.2 ± 0.1, SCI-DHPG; 2.6 ± 0.1, Fig. 5Q). No difference was observed between the SCI-DHPG and sham mice (sham-vehicle and sham-DHPG). Additionally, no difference was observed between the sham-vehicle and sham-DHPG (sham-vehicle; 2.7 ± 0.1, sham-DHPG; 2.6 ± 0.1, Fig. 5Q).

Ia-α synaptic connections in sham and spinal cord injury (SCI) after vehicle and (R,S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG). (A–P) Immunofluorescence staining for post synapse density (PSD-95) (green), vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (vGluT1) (red) and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) (cyan). White arrows show Ia–α connections. (Q) Number of Ia–α connections comparing vehicle group (white) and DHPG group (black). Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. sham-vehicle n (mice) = 6, sham-DHPG n = 6, SCI-vehicle n = 8, SCI-DHPG n = 7, sham-vehicle N (α motor neurons) = 302, sham-DHPG N = 292, SCI-vehicle N = 384, SCI-DHPG N = 344. Shapiro–Wilk test, ANOVA, Tukey–Kramer (***p < 0.001). (R) Graph of number of Ia (PSD-95 positive)–α connections comparing vehicle group (white) and DHPG group (black). Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. sham-vehicle n (mice) = 3, sham-DHPG n = 3, SCI-vehicle n = 3, SCI-DHPG n = 3. each group N (α motor neurons) = 150. Shapiro–Wilk test, ANOVA, Tukey–Kramer (n.s. = not significant).

Furthermore, to confirm whether the increased synaptic connections are stable, the number of triple merges of vGluT1, ChAT, and the post synapse density-95 (PSD-95), which is a stabile post-synapse maker, were compared between each group. No difference was observed in the number of stabile Ia-α synaptic connections between each group (sham-vehicle; 1.2 ± 0.2, sham-DHPG; 1.3 ± 0.2, SCI-vehicle; 1.1 ± 0.1, SCI-DHPG; 1.1 ± 0.2, Fig. 5R). Therefore, the Ia-α increased connections of SCI-vehicle are considered to be unstable synapses.

No changes were observed in the α motor neuronal activity after DHPG administration

We measured c-Fos, which is an early gene that is dependent on intracellular calcium concentration. We also determined the immunoreactivity in α motor neurons labelled for ChAT, whether the activity of α motor neurons in SCI mice increased, and whether drug administration affected α motor neuronal activity (Fig. 6A–D). The ratios of c-Fos- and ChAT-co-positive cells to all ChAT-positive cells were calculated. The ratio of c-Fos expression in ChAT-labelled α motor neurons was substantially upregulated in both SCI mice relative to the sham mice (Fig. 6E). However, no difference was observed between the vehicle and DHPG groups of the SCI mice. Ia fibre activity suppression did not affect motor neuronal activity.

Activity of α motor neurons by c-Fos expression. (A–D) Immunofluorescence staining for c-Fos (green) and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) (red). White arrows show co-positive cells. Scale bar = 50 μm. (E) Ratio of co-positive cells to all α motor neuron cells, comparing the vehicle group (white) and (R,S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) group (black). Data are represented as means ± S.E.M. sham-vehicle n (mice) = 5, sham-DHPG n = 4, SCI-vehicle; n = 6, SCI-DHPG n = 5. sham-vehicle N (α motor neurons) = 213, sham-DHPG N = 263, SCI-vehicle N = 340, SCI-DHPG N = 294. Shapiro–Wilk test, ANOVA, Tukey–Kramer (*p < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that continuous Ia fibre activity suppression induced the reduction of spasticity-related hyperreflexia and restored the overconnected synaptogenesis to normal. To confirm the decreased effect of spasticity in Ia inhibition in spastic muscle, DHPG was locally administered to the right forelimb around the forelimb abductor digiti minimi muscle as the spastic muscle using an osmotic pump and plastic tubes. It is thought that PLD-mGluR is responsible for dynamic and static muscle stretch because it depends on Ca2+. However, a previous study reported that glutamate release from SLV and its binding with PLD-mGluR mainly affect Ia fibre response to static stretch15. Further, the response to stretch stimulation, principally after muscle stretching, was suppressed by DHPG administration in this study (Supplementary Fig. S1). Ia fibre activity suppression was confirmed to relieve spasticity-related hyperreflexia after SCI by measuring the RDDs in the H-reflex. The continuous Ia activity suppression via DHPG administration was targeted at inducing the normalisation of Ia-α synaptic connections; however, this was not observed in the SCI-vehicle mice. We demonstrated an increase in the number of hyperexcited α motor neurons, which may project to the spastic muscle, in 4-week post-SCI mice relative to the sham mice21. However, no changes were observed in the α motor neuron activity or motor functional recovery following DHPG administration after SCI.

Relieving spasticity-related hyperreflexia after SCI via DHPG administration

H-reflex RDD is indicated in the spasticity model for the assessment of symptoms in various spastic models, such as those for SCI, stroke, and cerebral palsy3,6,21,22,23,24. The pathological features of spasticity are described in the spinal stretch reflex circuit. For example, the presynaptic inhibition connecting the Ia fibres is reduced after SCI, and α motor neuron hyperactivity is exacerbated8,21. In the present study, the stimulus frequency-dependent depression in H-reflex amplitude was closer to normal in the SCI mice after DHPG administration than in the vehicle; however, this did not return to normal. This repetitive synapse firing results in a transient decrease in synaptic strength, which decreases presynaptic Ca2+ currents, depletion of vesicles, desensitisation of the postsynaptic receptor, activity-dependent decreases in the neurotransmitter release probability, and failure of action potential conduction in the postsynaptic neuron25,26. In this study, vGlut1 was used as a marker of Ia fibre axonal endings. vGlut1 is also a marker in the corticospinal tract (CST)9. A previous study reported that vGlut1–positive fibres of the CST project to laminae VII and those of the RST project to laminae III and VI9,27,28. The vGlut1-positive fibres of Ia fibres project to laminae VII and IX and connect to α motor neurons directly29,30. Herein, the number of vGlut1 boutons per α motor neuron were calculated as means and were sham-vehicle; 2.7 ± 0.1, 2.6 ± 0.1, 4.2 ± 0.1, 2.6 ± 0.1 for the sham-vehicle, sham-DHPG, SCI-vehicle, and SCI-DHPG groups, respectively. In the SCI-vehicle mice at 4 weeks post-SCI, Ia-α connections were substantially increased relative to those in the SCI-DHPG, sham-vehicle and sham-DHPG mice. In a previous study, the number of vGlut1 boutons per α motor neuron increased to 3.5 ± 0.1 from 7 days after stroke with spasticity6. Thus, Ia activity suppression by DHPG administration may prevent excessive synaptic connections and/or promote the pruning of excessive synaptic connections.

Interestingly, no difference was observed in the number of stable synaptic connections that were double positive for vGluT1 and PSD-95 in α motor neurons between each group. PSD-95 is scaffold protein of excitatory synapses and is expressed in stable synapses. A previous study reported that PSD-95 is required for activity-dependent synapse stabilization after the initial phase of synaptic potentiation, and PSD-95 knockout induces high turnover of synapse31. Therefore, synapses without PSD-95 can be described as unstable synapses; however, they are reported to be functional32. In this study, the number of unstable synapses increased in SCI-vehicle and DHPG was able to decrease these unstable connections. These unstable synaptic connections may increase during neuronal plasticity due to spontaneous responses in the acute phase after injury. In addition, there were no differences in the number of stable Ia-α connections between each group. Therefore, Ia fibre activity suppression by DHPG may downregulate presynaptic Ca2+ currents and induce vesicle depletion by optimising the number of unstable synaptic connections. In contrast, α motor neuronal activity remained high after DHPG administration; therefore, the RDD of the H-reflex did not completely improve. However, the detailed underlying mechanisms and function of these synapses without PSD-95 in relation to the H-reflex RDD remain unclear. Further studies are needed in the future to investigate these mechanisms.

DHPG administration did not cause any changes in α motor neuron activity or recovery after SCI

One of the mechanisms underlying spasticity is increased excitability of the α motor neurons21,22. A previous study using a stroke model revealed an increase in the α motor neuronal activity in spastic mice21; however, studies reporting this in SCI mice are absent. Dendritic spine density and abnormal morphology in the α motor neurons were recently reported to be substantially increased at 4 weeks after SCI33. Dendritic spines are involved in synaptic and neuronal activities. In our study, the expression ratio of c-Fos and ChAT double-positive neurons was markedly increased in the vehicle and DHPG in 4-week post-SCI mice relative to sham-vehicle and sham-DHPG mice. Increased α motor neuron activity is one of the strongest mechanisms underlying spasticity development in SCI. We hypothesised that hyperexcitability of the α motor neurons increases inputs from the Ia fibres in addition to their own increased excitability. However, no change was observed in the hyperexcitation of the α motor neurons in SCI due to Ia activity suppression. The hyperexcitation of α motor neurons underlying the spasticity mechanisms was reported to be caused by factors such as the downregulation of K+-Cl−cotransporter 2 (KCC2) on α motor neurons22 and persistent inward currents34. In other words, motor neurons after SCI are excited. In the present study, Ia activity suppression lowered the input to motor neurons; however, it did not inhibit the motor neuron activity. In addition to the increased activity of the α motor neurons, this could also be due to the increasing activity of the cells of Ia fibres in the dorsal root ganglion or to inhibitory neuronal circuits. In particular, the spinal inhibitory neural circuit has been reported to exhibit the possibility of functional decline after central nerve injury5,11,35.

Additionally, it did not lead to marked recovery from motor dysfunction and did not block motor functional recovery caused by Ia suppression after SCI in this study. The muscle administered DHPG was the little abductor digiti minimi muscle (Supplementary Fig. S2). This muscle was chosen because it is the forelimb muscle for which spasticity symptoms can be measured using the H-reflex RDDs. The lack of motor functional efficacy was possibly due to the limited extent of drug administration, which was limited to finger muscles. Additionally, Ia suppression ameliorated maladaptive neuronal networks, such as Ia-α over connections. A recent study reported that rehabilitation induces the reorganization of CST and spinal neural networks, and this required normal proprioceptive input36,37. A previous study using knockout mice with muscle spindle function reported that motor function recovery after SCI was inhibited by blocking proprioceptive sensory information38. Thus, sensory information in the muscle spindle is important for the recovery from motor dysfunction in SCI. In this study, DHPG administration showed no effect on normal motor function and motor function recovery. DHPG administration may not induce oversuppression of Ia fibre activity. DHPG is a partial inhibitor of Ia fibres in the muscle spindles. Therefore, motor recovery following DHPG administration may not be blocked because Ia fibres can be activated even if DHPG is used. In the future, attempting that combination with rehabilitation after normalization of the spinal neural network by Ia suppression to further restore motor function will be expected.

Possible adverse effects of DHPG

Interestingly, DHPG affects not only PLD-mGluR as an antagonist but also mGluR group I (mGluR1 and mGluR5), which is a subtype of metabotropic glutamate receptors, as an agonist16,18,39. These receptors differ in their localisation. PLD-mGluR is expressed in the hippocampus, amygdala, and hair follicles in addition to the skeletal muscle spindle19,40,41,42,43,44. However, mGluR group I is widely expressed throughout the CNS45,46,47,48,49. In a previous study targeting mGluR group I, the ventricular administration of DHPG caused epileptic seizure and neuronal damage50. In this study, DHPG was intramuscularly administered to the right abductor digiti minimi muscle locally; however, these adverse effects did not occur. As a preliminary experiment, a high dose of DHPG was also administered intraperitoneally to wildtype mice, and there were no visually adverse effects in any experiments. Therefore, if DHPG is administered intraperitoneally or intramuscularly and enters the blood, it might not penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB). However, there are no reports on whether DHPG can cross the BBB or on its haemodynamics.

These results imply that continuous Ia fibre activity suppression using DHPG partly changes spinal neural network recovery and reduces spasticity. This approach is expected to become a new treatment option along with rehabilitation in the future. This study also focused on the acute phase after SCI. To date, spasticity interventions have been mostly initiated in the chronic phase. In recent years, interventions in the acute phase to manage spasticity symptoms, prevent secondary disability caused by spasticity, and achieve independence in activities of daily living have been attempted51. In the acute phase, the neural plasticity is high. Furthermore, in this study, we confirmed that suppression of Ia fibre activity from the acute phase after SCI causes spasticity symptom reduction and synaptic connection changes. This finding, together with the inhibition of Ia fibre activity, is an important point that can be expanded into clinical practice.

Limitations

This study had certain limitations that may affect the generalisability of the research. Only female mice were used in this study. DHPG is administered locally; however, it has not been confirmed whether it circulates systemically. Furthermore, only the SCI model was used in this study. It remains unclear whether suppression of Ia fibre activity is effective in all cases of spasticity because the mechanism of spasticity differs from that in other central nerve system injuries, such as stroke and cerebral palsy.

Conclusion

This research confirmed that the continuous suppression of Ia fibre by DHPG administration induced spasticity reduction and prevented overexpression of Ia-α synaptic connections in the spinal cord. However, this Ia fibre suppression did not affect recovery and/or restriction of motor function. Furthermore, the activity of α motor neurons was still high. There are two possibilities for the future of this research. First is confirming the effect of concurrent treatments for Ia fibre suppression and rehabilitation, which aim to enhance normal neuronal networks. Second is investigating the relationship between Ia fibres and the mechanism of spasticity (For example, changes in the activity of Ia fibres in the dorsal root ganglion and sensitivity at the mechanosensory endings).

Methods

Animals

All methods and procedures were approved by the Nagoya University Animal Experiment Committee (Approval No. D230013-002, D230012-003) and conducted accordance with the regulations of Nagoya University for Handling Experimental Animals. Adult female C57BL/6J mice (n = 50, 8–10 weeks old, 18–24 g; SLC, Shizuoka, Japan) were housed in standard cages with food and water and maintained under a 12-h light/dark cycle. Female mice were chosen to simplify post-SCI care, such as urinary drainage and infection. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

SCI model

The SCI model was constructed as follows: The mice were deeply anaesthetised (sedation, analgesia, and muscle relaxation) with a solution containing medetomidine hydrochloride (0.3 mg/kg, Nippon Zenyaku Kogyo Co., Fukushima, Japan), midazolam (4 mg/kg, Sand Co., Yamagata, Japan), and porphyrin tartrate (5 mg/kg, Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Tokyo, Japan). The fifth vertebral arch was removed, and the right sixth cervical cord was hemi-transected. Specifically, the right sixth cervical cord was completely damaged to the extent of 1 mm2. In this SCI model, spasticity onset occurred in the right forelimb. A Sham group was also established in which only the vertebral arch was removed. Mice in each group were randomly selected.

Electrophysiological recordings

Electrophysiological recordings were conducted as described in previous studies6,21. Briefly, the mice were anaesthetised with ketamine (200 mg/kg, CS Pharmacology Co., Aichi, Japan). A pair of stainless needle electrodes (EKA2-1508, Bioresearch Centre Corporation, Aichi, Japan) fixed with a micromanipulator (SM-15, Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted into the nerve bundles, including the ulnar nerve, and stimulated using a stimulator (1–3 mA in 0.1-mA increments, single pulse, SEN–7103, Nihon Kohden, Aichi, Japan). For recording, a pair of stainless needle electrodes fixed with a manipulator (YOU-2, Narishige) was transcutaneously placed into the forelimb abductor digiti minimi muscle and the recordings were obtained using an amplifier (high pass: 0.1, SS-201J, Nihon Kohden) and an A/D converter (low pass: 1 kHz, PowerLab, ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia) (Fig. 2A). After determining the intensity necessary to obtain the maximal H-reflex, the mice were stimulated with 23 trains at 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 Hz (with 2-min intervals between each train) to measure the RDD. H-reflexes were recorded at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after spinal cord injury and expressed as percentages relative to the mean response at 0.1 Hz in the same measurement series.

Drug administration

Drug administration was blinded from administration to the end of statistical analysis by a third party. The pumps were incubated in sterile saline at 37 °C for 48 h. Before implanting, the pumps were filled with 10 mM DHPG (0342/1, Tocris Bioscience Co., Bristol, UK) or PBS (a solvent of DHPG). After confirming spasticity in 1 week, an osmotic pimp (ALZET, Cupertino, CA, USA) was implanted in the backs of the mice under deep anaesthesia. Pumps were connected to 2 polyethylene tube types (SP55; I.D. 0.8 mm, O.D. 1.2 mm, SP 31; I.D. 0.5 mm, O.D. 0.8 mm, Natsume Seisakusho Co., Tokyo, Japan) and a cannula tube (I.D. 0.1 mm, O.D. 0.25 mm, ReCath Co., Allison Park, PA, USA), and each drug was flowed (0.11 μl/h) to the right paw under the skin. Drug administration was continued for 2 weeks, starting 1 week after SCI or sham injury. Mice were randomly selected, and the groups were named SCI-DHPG, SCI-vehicle, sham-DHPG, or sham-vehicle. When conducting the extracellular electrogram of Ia activity, DHPG was administered intramuscularly directly to the right digiti minimi muscle by one shot. Furthermore, in a simplified check of the effects of DHPG on wildtype mice, DHPG was administered by intraperitoneal injection.

Motor function analysis

All analyses were performed before SCI and 3 days and 1–4 weeks after SCI to confirm the changes in motor function.

Grid walk test

The grid walk test assessed coordinated movement52,53. The mice were allowed to freely walk on a grid and recorded for 2 min using a high-speed camera (EX-FH100, CASIO, Tokyo, Japan). The speed of all videos was changed to × 0.25 and the forelimb success steps on the affected side were counted. The successful step was defined as the right forelimb stepping without dropping the forelimb between the grids. For the quantification assessment, the success of all steps was calculated for 2 min.

Single pellet reach task

A single pellet reach task can be used to assess skilled movement. The diet of mice was restricted to 80–90% of the free diet before initiating training54. The mice were placed in a plastic chamber (20 cm × 8.5 cm × 15 cm) and trained to perform the reach task. The mice attempted the pellet grasping trials (F05684, Bio-Serv, Flemington, NJ, USA) 30 times or for a maximum of 20 min during each training session. The training was continued once a day for 10 days until the injury was administered. From the SCI model creation to 4 weeks after SCI, training was continued three times per week. During each test, reaching was recorded using a high-speed camera, and the ratio of successful reaches to all reaches was calculated. Training and analyses were blinded.

Histochemical analysis

After 4 weeks of SCI or sham, mice were deeply anaesthetised with sodium pentobarbital (Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) and transcranially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) dissolved in 0.1 M PBS. The region of the spinal cord from the fourth cervical to the second thoracic was removed and incubated in 4% PFA at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, they were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose. The tissues were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek, SAKURA Finetek, Tokyo, Japan) and stored at − 80 °C.

Analysis of the injury area

A cryostat was used to prepare the sagittal sections of the fourth to sixth vertebral arches (20 μm thick). The tissues were washed in water and 70% ethanol and subsequently incubated in Luxol fast blue stain solution at 57 °C for 2 h. After incubating, the tissues were washed in 70% ethanol and incubated in Cresyl violet solution at 37 °C for 10 min.

Immunostaining

A cryostat was used to prepare the coronal sections of the seventh cervical cord to the second thoracic cord (20 μm thick). vGlut1-ChAT and c-fos-ChAT were stained while semi-floating on glass slides and free-floating, respectively. Briefly, proteolytics-induced epitope retrieval (PIER) was performed to stain vGlut1 and PSD-95. For vGlut1, PIER included incubating the tissue in 0.01% trypsin for 5 min at 37 °C after washing in PBS6. For PSD-95, PIER included incubating the tissue in 4 mg/ml pepsin in HCl (pH = 1.12) for 10 min at 37 °C. After PIER, they tissues were pre-incubated in blocking buffer (5% normal donkey serum and 0.1% for vGlut1-ChAT staining section or 0.5% for c-Fos-ChAT staining section, Triton X-100 in PBS) for 2 h at room temperature. This was followed by incubation with each antibody, anti-vGluT1 antibody (1:500, 135304, Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany), anti-ChAT antibody (1:200 or 500, AB144P, Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), anti-PSD-95 antibody (1:200, AB2723, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and anti-c-Fos antibody (1:1000, ab190289, Abcam) in blocking buffer at room temperature or 4 °C overnight. After washing in PBS-T, the tissue was incubated for 2 h at room temperature in a solution containing secondary antibodies, which included donkey anti-goat IgG, donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000, A11055, A21206, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and donkey anti-guinea pig IgG (1:1000, 706-585-148, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA). All sections were examined using confocal laser scanning microscopy (magnification, × 60; A1Rsi, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and/or fluorescence microscopy (magnification, × 60 BZ-X810, KETENCE, Osaka, Japan). Each section was double-stained for vGlut1-ChAT and c-fos-ChAT. The region of interest was set on the ventral and lateral horns, on which the motor neurons for the forelimb abductor digiti minimi muscles are located, based on previous studies6,23. vGluT1 positive boutons were defined as those with diameters of > 1 mm, and ChAT-positive neural cells were defined as those with diameters of approximately 50 μm. For quantification assessment, c-Fos-positive motoneurons stained with ChAT were counted in 10 cross-sections. Each section contained more than 5 motor neurons. The motor neurons were differentiated by x and y coordinates.

Statistical analyses

Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to confirm the normality of the data. Student’s t-test or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey–Kramer post-hoc test or the Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted. This was followed by the Steel–Dwass test. The α level was set at 5%. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Data availability

Additional information required to reanalyse the data reported in this paper is available from the corresponding author [S. L.-H.] upon request.

References

Lance, J. W. The control of muscle tone, reflexes, and movement: Robert Wartenberg Lecture. Neurology 30(12), 1303–1313 (1980).

Lance, J. W. Disordered muscle tone and movement. Clin. Exp. Neurol. 18, 27–35 (1981).

Wieters, F. et al. Introduction to spasticity and related mouse models. Exp. Neurol. 335, 113491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113491 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Chemical denervation using botulinum toxin increases Akt expression and reduces submaximal insulin-stimulated glucose transport in mouse muscle. Cell Signal. 53, 224–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.10.014 (2019).

Mukherjee, A. & Chakravarty, A. Spasticity mechanisms—For the clinician. Front. Neurol. 1, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2010.00149 (2010).

Toda, T., Ishida, K., Kiyama, H., Yamashita, T. & Lee, S. Down-regulation of KCC2 expression and phosphorylation in motoneurons, and increases the number of in primary afferent projections to motoneurons in mice with post-stroke spasticity. PLoS ONE 9(12), e114328. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0114328 (2014).

Tan, A. M., Chakrabarty, S., Kimura, H. & Martin, J. H. Selective corticospinal tract injury in the rat induces primary afferent fiber sprouting in the spinal cord and hyperreflexia. J. Neurosci. 32(37), 12896–12908. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6451-11.2012 (2012).

Bellardita, C. et al. Spatiotemporal correlation of spinal network dynamics underlying spasms in chronic spinalized mice. eLife 6, e23011. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.23011 (2017).

Ueno, M. et al. Corticospinal circuits from the sensory and motor cortices differentially regulate skilled movements through distinct spinal interneurons. Cell Rep. 23(5), 1286–1300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.137 (2018).

Hori, K. & Hoshino, M. GABAergic neuron specification in the spinal cord, the cerebellum, and the cochlear nucleus. Neural Plast. 2012, 921732. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/921732 (2012).

Betley, J. N. et al. Stringent specificity in the construction of a GABAergic presynaptic inhibitory circuit. Cell 139(1), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.027 (2009).

Laliberte, A. M., Farah, C., Steiner, K. R., Tariq, O. & Bui, T. V. Changes in sensorimotor connectivity to dI3 interneurons in relation to the postnatal maturation of grasping. Front. Neural Circuits 15, 768235. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncir.2021.768235 (2021).

Bui, T. V. et al. Circuits for grasping: Spinal dI3 interneurons mediate cutaneous control of motor behavior. Neuron 78(1), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.007 (2013).

Simon, A., Shenton, F., Hunter, I., Banks, R. W. & Bewick, G. S. Amiloride-sensitive channels are a major contributor to mechanotransduction in mammalian muscle spindles. J. Physiol. 588(Pt 1), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2009.182683 (2010).

Than, K. et al. Vesicle-released glutamate is necessary to maintain muscle spindle afferent excitability but not dynamic sensitivity in adult mice. J. Physiol. 599(11), 2953–2967. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP281182 (2021).

Bewick, G. S. & Banks, R. W. Mechanotransduction in the muscle spindle. Pflugers Arch. 467(1), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-014-1536-9 (2015).

Watson, S. Modulating mechanosensory afferent excitability by an atypical mGluR. J. Anat. 227(2), 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.12319 (2015).

Bewick, G. S., Reid, B., Richardson, C. & Banks, R. W. Autogenic modulation of mechanoreceptor excitability by glutamate release from synaptic-like vesicles: Evidence from the rat muscle spindle primary sensory ending. J. Physiol. 562(Pt 2), 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2004.074799 (2005).

Banks, R. W. et al. Glutamatergic modulation of synaptic-like vesicle recycling in mechanosensory lanceolate nerve terminals of mammalian hair follicles. J. Physiol. 591(10), 2523–2540. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2012.243659 (2013).

Thompson, K. J. et al. The atypical “hippocampal” glutamate receptor coupled to phospholipase D that controls stretch-sensitivity in primary mechanosensory nerve endings is homomeric purely metabotropic GluK2. Exp. Physiol. 109(1), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1113/EP090761 (2024).

Lee, S., Toda, T., Kiyama, H. & Yamashita, T. Weakened rate-dependent depression of Hoffmann’s reflex and increased motoneuron hyperactivity after motor cortical infarction in mice. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1007. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2013.544 (2014).

Boulenguez, P. et al. Down-regulation of the potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2 contributes to spasticity after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 16(3), 302–307. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2107 (2010).

Lee, H. J. et al. Better functional outcome of compression spinal cord injury in mice is associated with enhanced H-reflex responses. Exp. Neurol. 216(2), 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.12.009 (2009).

Synowiec, S. et al. Spinal hyper-excitability and altered muscle structure contribute to muscle hypertonia in newborns after antenatal hypoxia-ischemia in a rabbit cerebral palsy model. Front. Neurol. 9, 1183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.01183 (2018).

Kavalali, E. T. Multiple vesicle recycling pathways in central synapses and their impact on neurotransmission. J. Physiol. 585(Pt 3), 669–679. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137745 (2007).

Hultborn, H. et al. On the mechanism of the post-activation depression of the H-reflex in human subjects. Exp. Brain Res. 108(3), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00227268 (1996).

Du Beau, A. et al. Neurotransmitter phenotypes of descending systems in the rat lumbar spinal cord. Neuroscience 227, 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.037 (2012).

Todd, A. J. et al. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 in neurochemically defined axonal populations in the rat spinal cord with emphasis on the dorsal horn. Eur. J. Neurosci. 17(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02406.x (2003).

Alvarez, F. J. et al. Permanent central synaptic disconnection of proprioceptors after nerve injury and regeneration. I. Loss of VGLUT1/IA synapses on motoneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 106(5), 2450–2470. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.01095.2010 (2011).

Alvarez, F. J., Bullinger, K. L., Titus, H. E., Nardelli, P. & Cope, T. C. Permanent reorganization of Ia afferent synapses on motoneurons after peripheral nerve injuries. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1198, 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05459.x (2010).

Ehrlich, I., Klein, M., Rumpel, S. & Malinow, R. PSD-95 is required for activity-driven synapse stabilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104(10), 4176–4181. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0609307104 (2007).

Migaud, M. et al. Enhanced long-term potentiation and impaired learning in mice with mutant postsynaptic density-95 protein. Nature 396(6710), 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1038/24790 (1998).

Benson, C. A. et al. Conditional RAC1 knockout in motor neurons restores H-reflex rate-dependent depression after spinal cord injury. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 7838. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87476-5 (2021).

Murray, K. C. et al. Recovery of motoneuron and locomotor function after spinal cord injury depends on constitutive activity in 5-HT2C receptors. Nat. Med. 16(6), 694–700. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2160 (2010).

Jankowska, E. & Puczynska, A. Interneuronal activity in reflex pathways from group II muscle afferents is monitored by dorsal spinocerebellar tract neurons in the cat. J. Neurosci. 28(14), 3615–3622. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0466-08.2008 (2008).

Punjani, N., Deska-Gauthier, D., Hachem, L. D., Abramian, M. & Fehlings, M. G. Neuroplasticity and regeneration after spinal cord injury. N. Am. Spine Soc. J. 15, 100235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xnsj.2023.100235 (2023).

Asboth, L. et al. Cortico-reticulo-spinal circuit reorganization enables functional recovery after severe spinal cord contusion. Nat. Neurosci. 21(4), 576–588. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0093-5 (2018).

Takeoka, A., Vollenweider, I., Courtine, G. & Arber, S. Muscle spindle feedback directs locomotor recovery and circuit reorganization after spinal cord injury. Cell 159(7), 1626–1639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.019 (2014).

Ito, I. et al. 3,5-Dihydroxyphenyl-glycine: A potent agonist of metabotropic glutamate receptors. NeuroReport 3(11), 1013–1016 (1992).

Krishnan, B. et al. Dopamine-induced plasticity, phospholipase D (PLD) activity and cocaine-cue behavior depend on PLD-linked metabotropic glutamate receptors in amygdala. PLoS ONE 6(9), e25639. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025639 (2011).

Boss, V., Nutt, K. M. & Conn, P. J. L-cysteine sulfinic acid as an endogenous agonist of a novel metabotropic receptor coupled to stimulation of phospholipase D activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 45(6), 1177–1182 (1994).

Albani-Torregrossa, S. et al. Antagonist pharmacology of metabotropic glutamate receptors coupled to phospholipase D activation in adult rat hippocampus: Focus on (2R,1’S,2’R,3’S)-2-(2’-carboxy-3’-phenylcyclopropyl)glycine versus 3, 5-dihydroxyphenylglycine. Mol. Pharmacol. 55(4), 699–707 (1999).

Pellegrini-Giampietro, D. E., Torregrossa, S. A. & Moroni, F. Pharmacological characterization of metabotropic glutamate receptors coupled to phospholipase D in the rat hippocampus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 118(4), 1035–1043. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15503.x (1996).

Krishnan, B. et al. Fear potentiated startle increases phospholipase D (PLD) expression/activity and PLD-linked metabotropic glutamate receptor mediated post-tetanic potentiation in rat amygdala. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 128, 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2015.12.009 (2016).

Lujan, R., Nusser, Z., Roberts, J. D., Shigemoto, R. & Somogyi, P. Perisynaptic location of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1 and mGluR5 on dendrites and dendritic spines in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 8(7), 1488–1500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01611.x (1996).

Kano, M. et al. Persistent multiple climbing fiber innervation of cerebellar Purkinje cells in mice lacking mGluR1. Neuron 18(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80047-7 (1997).

Reid, S. N., Romano, C., Hughes, T. & Daw, N. W. Immunohistochemical study of two phosphoinositide-linked metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1 alpha and mGluR5) in the cat visual cortex before, during, and after the peak of the critical period for eye-specific connections. J. Comp. Neurol. 355(3), 470–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.903550311 (1995).

Cozzoli, D. K. et al. Binge alcohol drinking by mice requires intact group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling within the central nucleus of the amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology 39(2), 435–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.214 (2014).

Bäckström, P. & Hyytiä, P. Involvement of AMPA/kainate, NMDA, and mGlu5 receptors in the nucleus accumbens core in cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology 192(4), 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-007-0753-8 (2007).

Camón, L., Vives, P., de Vera, N. & Martínez, E. Seizures and neuronal damage induced in the rat by activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors with their selective agonist 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine. J. Neurosci. Res. 51(3), 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980201)51:3%3c339::AID-JNR7%3e3.0.CO;2-H (1998).

Holtz, K. A., Lipson, R., Noonan, V. K., Kwon, B. K. & Mills, P. B. Prevalence and effect of problematic spasticity after traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 98(6), 1132–1138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.09.124 (2017).

Singh, A. et al. Forelimb locomotor rating scale for behavioral assessment of recovery after unilateral cervical spinal cord injury in rats. J. Neurosci. Methods 226, 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.01.001 (2014).

Shi, X. et al. Behavioral assessment of sensory, motor, emotion, and cognition in rodent models of intracerebral hemorrhage. Front. Neurol. 12, 667511. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.667511 (2021).

Chen, C. C., Gilmore, A. & Zuo, Y. Study motor skill learning by single-pellet reaching tasks in mice. J. Vis. Exp. 85, 38. https://doi.org/10.3791/51238 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The author (T. H.) would like to take this opportunity to thank the ‘Interdisciplinary Frontier Next-Generation Researcher Program of the Tokai Higher Education and Research System’. The authors wish to acknowledge Division for Medical Research Engineering, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, for technical support of Division for Medical Research Engineering and so on.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI JP 18K10706, 21K11260, the 46th Foundation of Daiwa Shoukenn Health provided to S. L.-H., and JST SPRING, Grant Number JPMJSP2125 provided to T.H.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L.-H. conceived and designed the experiments; T.H., K.H. performed development of methodology and provided acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and statistical analysis; Y.S. assisted with the experiments. S.L.-H., T.H. wrote and review and revision of the paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanasaki, T., Hanaki, K., Sako, Y. et al. Effect of continuous Ia fibre activity suppression on hyperreflexia-related spasticity and maladaptive synaptic connections in the spinal cord after injury. Sci Rep 15, 23764 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09397-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09397-x