Abstract

The Tatun Volcano Group (TVG), located at the northern tip of Taiwan, is situated near the Taipei metropolitan area. A future eruption of the TVG could have a significant impact not only on Taipei but also on the global economy, as Taiwan produces over 90% of the world’s most advanced semiconductor chips. Although a magma reservoir has been identified beneath the TVG, it remains uncertain whether it contains eruptible magma. Using seismic data recorded by the Formosa Array, we detected strong seismic reflections from the magma reservoir. Both travel-time modeling and polarization of these reflections indicate that the top of the reservoir lies at a depth of approximately 13–15 km—significantly deeper than the ~ 8 km depth previously estimated from seismic tomography. This notable discrepancy supports a conceptual model in which magma reservoirs are divided into eruptible and non-eruptible portions. Our findings suggest that a substantial amount of eruptible magma may exist beneath the TVG. However, a volcanic eruption would only occur if the pressure from accumulating magma exceeds the rock load of the overlying crust.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

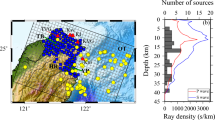

The Tatun Volcano Group (TVG), located along the northern border of the Taipei metropolitan area (Fig. 1), is considered a low-magnitude volcano with the potential for significant global economic impact1. Since Taiwan produces over 90% of the world’s most advanced semiconductor chips2, a volcanic eruption at the TVG could disrupt the supply chain of TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.) manufacturing plants. Although no historical eruptions have been recorded, a magma reservoir beneath the TVG was first identified through S-wave shadowing and P-wave delays3. To better estimate the potential size and depth of this magma reservoir, a dense broadband seismic network, the Formosa Array4, has been deployed in northern Taiwan since 2018 (Fig. 1). More details on the Formosa Array are provided in the Materials and Methods section. Using seismic data collected between 2018 and 2020, tomographic images constructed from tens of thousands of P-wave arrival times—generated by both local and teleseismic earthquakes—have clearly delineated the general geometry of the magma reservoir5. This reservoir appears as a low-velocity zone extending at depths from approximately 8 km to 20 km beneath the TVG. Similar to geophysical observations at other active volcanoes6,7,8,9,10, this low-velocity zone suggests that the magma reservoir contains only a partial melt fraction (< 20%). Although the fraction of molten magma is limited, it may still be classified as eruptible magma, which plays a key role in determining both the likelihood and scale of a potential eruption11,12. In general, a larger volume of molten magma increases both the probability and magnitude of an eruption.

Map of northern Taiwan showing the locations of two extremely shallow earthquakes (blue circles), seismic stations of the Formosa Array (black triangles), the Tatun Volcano Group (red dashed-circle zone), the Shanchiao Fault (green dashed line), the magma reservoir (elliptical red area), and Taipei City (yellow square). The study area is marked by a square in the inset map of Southeast Asia.

Although the average volume of eruptible magma within a reservoir can be roughly estimated from seismic velocity values in low-velocity zones using traditional seismic methods5,6,7,8,9,10, the spatial resolution of seismic images is often insufficient to reveal the detailed distribution of eruptible magma within the reservoir10. In most magma reservoirs beneath volcanic arcs, seismic tomography—despite being based on large datasets of earthquake arrivals—generally lacks the resolution needed to determine the precise distribution of molten magma in the deep crust. This limitation is largely due to an insufficient number of seismic stations and an uneven distribution of seismic ray paths. While seismic reflections could theoretically overcome these challenges, the energy from active seismic sources is often too weak to probe magma reservoirs deep within the crust. As a result, it remains unclear whether eruptible magma is either randomly distributed throughout the reservoir13,14 or primarily concentrated in its upper portion12,15. Distinguishing between these two scenarios is crucial for assessing future eruption potential. If magma is concentrated near the top of the reservoir, it may be more prone to erupt than if it is randomly dispersed16,17. Understanding this distribution is therefore essential for evaluating volcanic hazards.

To investigate the possible spatial distribution of eruptible magma beneath the TVG in northern Taiwan, we carefully analyze seismic data from shallow earthquakes occurring above the magma reservoir, as recorded by the Formosa Array (Fig. 1). We take advantage of both the high-quality seismic data provided by the dense station coverage of the Formosa Array and the strong seismic energy generated by two extremely shallow earthquakes (at depths of 3.8 km and 2.9 km) located directly above the magma reservoir. Although these earthquakes have relatively small local magnitudes (ML 3.4 and 3.7), it is surprising to observe not only direct P-waves but also strong late-arriving P-waves recorded by the Formosa Array. Further ray-tracing modeling, comparing observed and calculated travel-time differences, will be employed to examine that these strong late P-waves may be reflections from either the magma reservoir or other major discontinuous boundaries. Finally, the distribution of molten magma is discussed by comparing these findings with previous seismic tomography images of the magma reservoir5.

Results

Strong later P-waves

In addition to the direct P-waves, it is surprising to observe strong late-arriving P-waves generated by two extremely shallow earthquakes at the TVG (Table 1), as well-recorded by the Formosa Array in northern Taiwan (Figs. 2 and 3). These earthquakes, with local magnitudes (ML) of 3.4 and 3.7, are among the largest recorded at the TVG in recent decades, slightly smaller than the most recent major earthquake (ML 4.2)18 that occurred in 2014 when the Formosa Array was not deployed yet. Although these events are relatively small compared to the frequent earthquakes with magnitudes exceeding 5 or 6 in eastern Taiwan, they still generated strong seismic energy that was clearly captured by the Formosa Array (Fig. 1). More details on the Formosa Array and seismogram data can be found in the Materials and Methods section. For both earthquakes, distinct late-arriving phases (Px), with seismic amplitudes comparable to those of the direct P-waves (Pg), were prominently recorded by the Formosa Array (Figs. 2b and 3b). These strong Px phases, arriving approximately 1.5 s after the Pg phases, were consistently detected at a subset of southeastern stations within the Formosa Array (Figs. 2a and 3a). Notably, the delay times between the direct P-waves (Pg) and the later P-waves (Px) slightly decrease with increasing epicentral distance (Figs. 2b and 3b). In addition to the late-arriving P-waves observed on the vertical components, clear later S-waves (Sx) generated by Event 1 were also observed on the horizontal components of some seismic stations within the Formosa Array (Fig. 4).

Seismic observations and ray-tracing calculations for Pg and Px waves generated by Event 1 and recorded at selected Formosa Array stations. (a) Locations of Event 1 (circle), the magma reservoir (red area), the Shanchiao Fault (dashed line), and seismic stations (triangles). (b) Vertical seismograms displaying Pg and Px phases. (c) Travel-time fitting between observed and calculated arrivals. (d) Ray-tracing results for both direct Pg waves and Px waves reflected from the roof of the magma reservoir along the NW–SE profile (the O–X axis on Fig. 2a). The focal mechanism is projected onto the vertical profile. (e) A simplified velocity model of the upper crust.

Seismic observations and ray-tracing calculations for Pg and Px waves generated by Event 2 and recorded by the Formosa Array. (a) Locations of Event 2 (blue circle), the magma reservoir (red area), the Shanchiao Fault (purple dashed line), and seismic stations (triangles). (b) Vertical seismograms showing Pg and Px phases. (c) Travel-time fitting between observed and calculated arrivals. (d) Ray-tracing results for both direct Pg waves and Px waves reflected from the roof of the magma reservoir. (e) A simplified velocity model of the upper crust.

Direct S-waves (Sg) and later S-waves (Sx) generated by Event 1, as observed in both N- and E-components of 11 Formosa Array stations shown in Fig. 2a.

Since both earthquakes occurred at extremely shallow depths (3.8 km and 2.9 km) within the TVG, the late-arriving P-waves (Px) may have been reflected from deeper structures around the mid-crust. This interpretation is based on preliminary estimations of both travel-time delays and particle motions. First, possibility of lateral reflections significantly away the vertical profile along the earthquake and seismic stations can be ruled out, as the polarizations of the later P-waves are almost identical to those of the direct P-waves. A detailed analysis of particle motions for both direct and later P-waves will be presented in the Materials and Methods section. Second, the reflector is likely closer to the earthquake source than to the seismic stations, as Px phases were recorded only at a subset of southeastern stations within the Formosa Array (Figs. 2a and 3a). See some representative examples in the Materials and Methods section for showing all possible reflecting points can be constrained by the delay time between the direct and later P-waves at different stations. Given these observations, one intuitive explanation is that the Conrad discontinuity, a common boundary in continental crust19, could be responsible for generating the Px phases. Alternatively, other possible reflectors include either the top of the magma reservoir5 or other major faults such as the Shanchiao Fault20, as both earthquakes occurred near the western boundary of the magma reservoir, close to the Shanchiao Fault.

Ray-tracing modeling

To further investigate the possible reflector responsible for generating the Px phases, we assume a two-dimensional vertical profile along the NW–SE direction (O–X axis in Figs. 2a and 3a) to compare observed and calculated travel-time differences between Pg and Px for Events 1 and 2. A simplified 1-D velocity structure (Figs. 2e and 3e) is used as the initial model to compute ray paths and travel times. Additional details on the ray-tracing modeling for Pg and Px fitting are provided in the Materials and Methods section. Although the Conrad discontinuity is a potential candidate for producing the Px phases, it cannot account for the slight variations in delay times between Pg and Px, as such variations cannot be generated by a horizontal reflector like the Conrad discontinuity. Instead, a convex, southeast-dipping reflector provides a better fit for the observed Pg and Px arrivals. Through multiple iterations of forward modeling for Event 1, we obtain an acceptable result by matching the general trend of arrival times for both the direct and reflected waves. This suggests that the reflector corresponds to a gradual southeast-dipping boundary at depths of approximately 14–15 km. Although minor discrepancies less than ~ 0.2 s remain between the observed and calculated travel times, these differences are within an acceptable range, considering uncertainties in arrival time measurements, the use of a simplified velocity model, and the projection along the O–X direction on Fig. 2a.

Similar to Event 1, Event 2 yields nearly identical results (Fig. 3). Consistent late-arriving Px phases with strong seismic amplitudes are observed at 13 seismic stations of the southeastern Formosa Array (Fig. 3b). The same velocity model (Fig. 3e) is used to compute the arrival times of both Pg and Px along the two-dimensional NW–SE profile (O–X axis) on the Fig. 3a. The forward modeling results indicate that a convex, southeast-dipping reflector, with a gradual slope at depths of approximately 13–14 km, provides the best fit for the observed and calculated arrival-time differences (Figs. 3c and 3d). As with Event 1, minor discrepancies of less than ~ 0.2 s remain between the observed and calculated arrival times. However, these differences can likely be attributed to inevitable observational uncertainties and the use of a simplified velocity model along the NW–SE profile again.

Discussion

The strong seismic waves reflected from the southeast-dipping convex ramp in the mid-crust (13–15 km) strongly suggest the presence of a significant physical boundary at the roof of the magma reservoir (Fig. 5), even though several alternative explanations could be considered below. First, the dipping convex ramp beneath the TVG is unlikely to correspond to the Conrad discontinuity, as this boundary is typically sub-horizontal, marking the transition between granite in the upper crust and basaltic rock in the lower crust19. Second, while the Shanchiao Fault also dips to the southeast20,21, its depth extension appears insufficient to account for the observed east-dipping reflector beneath the TVG. In the case of a listric fault21, the convex ramp transitions to a nearly horizontal segment at a depth of 3–4 km. For a planar fault with a dip angle of 50–60 degrees20, the fault plane would extend to approximately 6–8 km beneath the TVG—shallower than the observed reflector. Given these constraints, the southeast-dipping convex ramp responsible for the reflected seismic energy is most likely associated with the magma reservoir beneath the TVG, which has been consistently identified in previous seismic studies3,5,22. Notably, the east-dipping reflector at approximately 13—15 km depth lies within the low-velocity zone extending from 8 to 20 km, further supporting its association with the magma reservoir beneath the TVG5.

Ray-tracing results from two earthquakes (Ev1 and Ev2), outlining the top of the magma reservoir (red area) along the O–X profile. The low-velocity zone at depths of 8–20 km5 is outlined by a dashed line. The inset map shows the locations of the two earthquakes (Ev1 and Ev2), the magma reservoir, and the Shanchiao Fault in northern Taiwan.

The strong seismic reflections observed in Figs. 2 and 3 are also unlikely to be caused by the boundary of low-velocity zones within the magma reservoir (Fig. 5). The comparable seismic amplitudes of both the direct (Pg) and reflected (Px) waves in Figs. 2b and 3b as well as the direct (Sg) and reflected (Sx) waves in Fig. 4 suggest a significant acoustic impedance contrast at the roof of the magma reservoir. Strong seismic reflections may occur when waves travel from a higher-impedance upper crust into a significantly lower-impedance magma reservoir. Since acoustic impedance is the product of rock density and seismic velocity, this dramatic contrast must result from a substantial difference in their parameters. However, the density contrast between the magma reservoir and its surrounding rocks should be minor—otherwise, gravitational buoyancy would cause the reservoir to migrate to a stable depth. Although low-velocity zones have been identified within the magma reservoir5, velocity perturbations in the main body of the reservoir are generally less than 10%. This suggests that the velocity contrast alone is insufficient to produce such strong reflections. Therefore, the large impedance contrast at the reservoir’s roof cannot be explained solely by slight differences in rock density or seismic velocity.

Rather than low-velocity zones alone, a considerable amount of molten magma accumulated at the uppermost portion of the reservoir is required to generate strong reflection amplitudes23. Based on previous seismic observations of S-wave shadows3, the magma reservoir beneath the TVG likely contains some liquid melt. This observation is further confirmed by the presence of strong S-waves (Sx phases) shown in Fig. 4. In other words, the detection of strong late-arriving S-waves strongly suggests the existence of liquid melt at the top of the magma reservoir, as S-waves cannot propagate through liquid material and are instead completely reflected. Even a thin layer of liquid melt at the top of the reservoir would significantly reduce the acoustic impedance within the reservoir while increasing the impedance contrast at its roof. This strong reflection feature is analogous to the “Bright Spot” phenomenon in reflection seismology24, a high-reflectivity seismic attribute anomaly often associated with the presence of gas or soft oil in seismic data. Even although the more quantitative estimation of the melt proportion can’t be obtained due to the absence of the well-constrained focal mechanism, the strong seismic amplitudes reflected from the roof of the magma reservoir provide compelling evidence for the presence of molten magma (> 50%) within its uppermost portion.

Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the estimated depths of seismic reflections from the magma reservoir differ slightly between Events 1 and 2 based on the ray-tracing modeling results (Fig. 5). The reflection depth for Event 1 is approximately 14–15 km, whereas for Event 2, it is around 13–14 km. This depth variation suggests that the reflector on the magma reservoir may gradually become shallower southward, given that Event 1 is located about 3 km north of Event 2 on the map. It is consistent with the fact that younger eruptions are more commonly found around the Mt. Chishin area25,26 than the Mt. Huangdra area.

To explain the seismic observations from both the reflected waves in this study and the previous tomographic images5 together, we propose a conceptual model that incorporates physical, chemical, and thermal boundaries in and around the magma reservoir (Fig. 6). As mentioned above, the estimated depths of the roof of the magma reservoir are approximately 14–15 km for Event 1 and 13–14 km for Event 2. These depths are significantly deeper than the ~ 8 km depth to the top of the low-velocity zones identified through tomographic inversion5, which indicate that these zones extend from roughly 8–20 km in depth. The notable 5–7 km discrepancy is unlikely to result from observational or computational uncertainties in either travel-time modeling of seismic reflections or seismic tomography inversion. Instead, this depth difference may be attributed to distinct physical, chemical, or thermal boundaries in and around the magma reservoir (Fig. 6). Seismic reflections delineate the magma reservoir roof, whereas the low-velocity zones primarily correspond to the thermal boundary. The low-velocity zones observed in tomographic images may not only represent the magma reservoir itself but also its overlying crust, which has been heated by high-temperature magma. Although thermal anomalies are expected in the overlying crust, no sharp seismic boundary is observed at the top of the low-velocity zone due to the gradual increase in the thermal gradient. In contrast, the magma reservoir roof represents a significant chemical and physical boundary capable of efficiently reflecting seismic energy with large amplitudes as seismic waves transition from the heated crust into the molten magma at the uppermost portion of the reservoir.

Schematic representation of idealized chemical, physical, and thermal boundaries in and around the magma reservoir. (a) The low-velocity zone within and surrounding the magma reservoir is divided into eruptible and non-eruptible portions, overlaid by the heated crust. (b) Thermal anomalies represented by a low-velocity seismic zone in and around the magma reservoir.

The molten magma within the upper portion of the magma reservoir may be considered eruptible. The extremely low acoustic impedance suggests a crystal-poor, melt-rich composition, distinguishing it from the non-eruptible materials, such as the rigid, sponge-like regions found in other parts of the reservoir12,27,28. Although the TVG has been a long-dormant active volcano3,5,25,26, a significant amount of molten magma may have gradually accumulated in the upper portion of the reservoir over tens or hundreds of thousands of years. This accumulation likely occurs through the ascent of magma within dikes or sills randomly distributed throughout the reservoir29. In fact, spherical diapirs have been detected within the mantle wedge beneath northern Taiwan30, indicating magma sources generated by subduction processes. The concentration of eruptible magma in the upper reservoir may be more prone to eruption than magma that is randomly distributed, as the buoyancy of accumulated molten material can generate sufficient overpressure16,17. While the presence of melt beneath a volcano has been suggested as a potential warning sign of an imminent eruption11, an eruption at TVG would only occur if the pressure from accumulated magma in the upper reservoir exceeds the rock load of the overlying crust. In other words, the presence of molten magma beneath active volcanoes may be a normal state, particularly when detected using a dense seismic array3,5,22.

Materials and methods

Seismic data

We utilize seismic data collected by the Formosa Array, a network of 146 broadband seismic stations deployed across northern Taiwan since 20184,5,29. The stations are distributed as evenly as possible, with an average spacing of approximately 5 km over an area of ~ 60 km × ~ 40 km (Fig. 1). Each station is equipped with a Nanometrics Meridian Compact PH broadband seismometer, which has an instrument response range of 0.01–50 Hz. To minimize noise, seismometers are installed either in 2-m boreholes or on hard rock surfaces. All seismic data are sampled at 100 Hz and transmitted in real time to the Institute of Earth Sciences, Academia Sinica and the Taiwan Volcano Observatory at Tatun (TVO), Taipei, Taiwan via wireless radio or telephone systems. This setup allows for immediate data retrieval and continuous monitoring to ensure that all stations, instruments, and transmission systems are functioning properly. More detailed information and access to seismic data are available on the project website (https://fmarray.earth.sinica.edu.tw).

Single events

To exclude possibility of the Px (or Sx) waves generated by the another earthquake, we have carefully checked the seismograms recorded at the entire array (Formosa Array). The results show that the later Px or Sx phases are not detected across the entire array. For example, there are only unambiguous Pg and Sg observed at 3-component seismograms recorded in and around the TVG (Fig. 7). As a result, absence of later Px or Sx phases nearby the earthquake clearly show the they were not generated by any other event in and around the TVG.

Polarization of later phases

To estimate the possible reflection source of the later P-waves, we analyze the polarizations of both Pg and Px phases generated by Events 1 and 2. For example, horizontal seismograms from Event 1, recorded at stations KM01 and PN12, show that the particle motions of both Pg and Px are consistently aligned with the earthquake azimuth in the NW–SE direction (Fig. 8). This alignment suggests that the Px phases are not reflections from lateral structures away from the vertical profile between the earthquake and the seismic station. Instead, the reflector is likely located within a narrow zone along this profile. Similar results are observed for Event 2 (Fig. 9), where the polarizations of both Px and Pg phases at stations KM01 and KM04 generally align with the direct ray-path direction. In summary, the polarization analysis of Pg and Px waves from both events suggests that the later Px phases are reflected from subsurface structures located around the vertical profile between the earthquake and seismic station.

Reflector estimated from the delay times

To further assess the potential reflector, we plot the projections of all possible reflection points based on the travel-time delay between the direct (Pg) and later (Px) P-waves at different seismic stations (Fig. 10). Each possible reflection point forms an ellipsoid with two focal points: the hypocenter and the seismic station. By examining data from stations KM01 and KM07, which have well-distinguished azimuths, we find that their common reflectors are roughly located beneath the hypocenter. Similarly, for stations KM01 and KE12, which have significantly different hypocentral distances, the common reflectors again appear near the hypocenter. These results consistently indicate that location of the possible reflectors is not only closer to the earthquake source than the seismic stations but is also likely located directly beneath the hypocenter at mid-crustal depths between 10 and 20 km.

Ray-tracing modeling

To investigate the possible geometry of the subsurface structures responsible for generating the later P-waves (Px) detected by the Formosa Array (Figs. 2b and 3b), we use a two-dimensional ray-tracing method to calculate ray paths and their travel times31. Based on previous findings32, we initially assume a simplified 2D model consisting of an uppermost crust overlying a mid-crustal structure to match the observed Pg and Px arrivals recorded at the seismic stations (Figs. 2b and 3b). The model is simply divided into two layers based on P-wave velocity (e.g., Figs. 2e and 3e). The upper layer has a velocity of 5.0 km/s at the sea level, gradually increasing to 5.6 km/s at a depth of 12 km. The lower layer starts with a velocity of 5.8 km/s at its top and increases to approximately 6.0 km/s at a depth of 20 km. To achieve the best fit for both Pg and Px observations, the geometry of the velocity boundary between these two layers is iteratively adjusted. Instead of a strictly horizontal interface, we explore dipping or even curved boundaries (Figs. 2d and 3d), allowing the calculated travel times to align as closely as possible with the observed data (Figs. 2c and 3c).

To constrain the reliable depth of the reflector, we only select unambiguous arrivals of Px for fitting travel-times (Figs. 2c and 3c). For example, the arrivals of Px have been only picked at the epicentral distances around 25–45 km from Event 1. Although some Px phases might be also roughly visible at longer epicentral distances from 45 km to ~ 65 km (Fig. 11), the arrivals were strongly contaminated by a lot of background noises in the Ilan Plain.

Data availability

Seismic data used in this study have been collected and carefully analyzed by the Taiwan Volcano Observatory at Tatun (TVO) in Taiwan. The seismic records are also provided in a supplementary file (data-SR.zip).

References

Mani, L., Tzachor, A. & Cole, P. Global catastrophic risk from lower magnitude volcanic eruptions. Nat. Commun. 12, 4756 (2021).

Hille, K. TSMC: How a Taiwanese chipmaker became a linchpin of the global economy. Financ. Times (2021).

Lin, C. H. Evidence for a magma reservoir beneath the Taipei metropolis of Taiwan from both S-wave shadows and P-wave delays. Sci. Rep. 6, 39500 (2016).

Lin, C. H., Shih, M. H. & Lai, Y. C. A strong seismic reflector in the mantle wedge above the Ryukyu subduction system beneath northern Taiwan. Seism. Res. Lett. 91(1), 310–316 (2020).

Huang, H. H. et al. Unveiling Tatun volcanic plumbing structure induced by post-collisional extension of Taiwan mountain belt. Sci. Rep. 11, 5286 (2021).

Hill, G. J. et al. Distribution of melt beneath Mount St. Helens and Mount Adams inferred from magnetotelluric data. Nat. Geosci. 2, 785–789 (2009).

Huang, H. H. et al. The Yellowstone magmatic system from the mantle plume to the upper crust. Science 348(6236), 773–776 (2015).

Pritchard, M. E. & Gregg, P. M. Geophysical evidence for silicic crustal melt in the continents: Where, what kind, and how much?. Elements 12, 121–127 (2016).

Magee, C. et al. Magma plumbing systems: A geophysical perspective. J. Petrol. 59, 1217–1251 (2018).

Weber, G., Caricchi, L., Arce, J. L. & Schmitt, A. K. Determining the current size and state of subvolcanic magma reservoirs. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–14 (2020).

Cooper, K. M. & Kent, A. J. R. Rapid remobilization of magmatic crystals kept in cold storage. Nature 506(7489), 480–483 (2014).

Barboni, M. et al. Warm storage for arc magmas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 13959–13964 (2016).

Jaxybulatov, K. et al. A large magmatic sill complex beneath the Toba caldera. Science 346, 617–619 (2014).

Lin, C. H. et al. Seismic detection of a magma reservoir beneath Turtle Island of Taiwan by S-wave shadows and reflections. Sci. Rep. 8, 16401 (2018).

Lamoureux, G., Ildefonse, B. & Mainprice, D. Modelling the seismic properties of fast-spreading ridge crustal low-velocity zones: Insight from Oman gabbro textures. Tectonophysics 312, 283–301 (1999).

Jellinek, A. M. & DePaolo, D. J. A model for the origin of large silicic magma chambers: Precursors of caldera-forming eruptions. Bull. Volcanol. 65, 363–381 (2003).

Malfait, W. J. et al. Supervolcano eruptions driven by melt buoyancy in large silicic magma chambers. Nat. Geosci. 7, 122–125 (2014).

Pu, H. C. et al. Geological implications of the 0212 earthquake in 2014 at the Tatun Volcano Group of Taiwan: Synergistic effect of volcanic and faulting activities. J. Asian Earth Sci. 149, 93–102 (2017).

Kearey, P., Klepeis, K. A. & Vine, F. J. Global Tectonics 3rd edn, 19–21 (Wiley, 2009).

Lin, C.-W. et al. An introduction to the active faults of Taiwan, 2nd ed., explanatory text of the active fault map of Taiwan. Spec. Publ. Cent. Geol. Surv. 13, 1–122 (2000).

Chen, Z. T. et al. Elucidating the geometry of the active Shanchiao fault in the Taipei metropolis, northern Taiwan, and the reactivation relationship with preexisting orogen structures. Tectonics 33, 2400–2418 (2014).

Lin, Y. P. et al. Unveiling attenuation structures in the northern Taiwan volcanic zone. Sci. Rep. 14, 4716 (2024).

Detrick, R. S. et al. Multi-channel seismic imaging of a crustal magma chamber along the east pacific rise. Nature 326, 35–41 (1987).

Onajite, E. Seismic Data Analysis Techniques in Hydrocarbon Exploration 213–228 (Elsevier Inc., 2014).

Belousov, A., Belousova, M., Chen, C. H. & Zellmer, G. F. Deposits character and timing of recent eruptions and gravitational collapses in Tatun volcanic group, northern Taiwan: Hazard-related issues. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 191, 205–221 (2010).

Zellmer, G. F., Kenneth, H. R., Miller, C. A., Shellnutt, J. G. & Belousov, A. Resolving discordant U-Th-Ra ages: Constraints on petrogenetic processes of recent effusive eruptions at Tatun Volcano Group, northern Taiwan. In Physical and Temporal Evolution of Magmatic systems (eds Caricchi, J. & Blundy, J. D.) 422 (Geological Society, Special Publication, 2015).

Miller, C. F. Eruptible magma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113(49), 13941–13943 (2016).

Lacovino, K. et al. Quantifying gas emissions from the “Millennium Eruption” of Paektu volcano, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea/China. Sci. Adv. 2(11), e1600913 (2016).

Cashman, K. V., Sparks, R. S. J. & Blundy, J. D. Vertically extensive and unstable magmatic systems: A unified view of igneous processes. Science 355, eaag3055 (2017).

Lin, C. H., Shih, M. H. & Lai, Y. C. Mantle wedge diapirs detected by a dense seismic array in northern Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 11, 1561 (2021).

Luetgert, J. H. MacRay-interactive two-dimensional seismic raytracing for the Macintosh. US Geological Survey Open File Report, 92–356 (1992).

Shin, et al. A preliminary report on the 1999 Chi-Chi (Taiwan) earthquake. Seismol. Res. Lett. 71, 24–30 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank our colleagues at the Institute of Earth Sciences, Academia Sinica, and the Taiwan Volcano Observatory at Tatun, as well as the National Center for Research on Earthquake Engineering in Taipei, Taiwan, for their dedication in deploying and maintaining the seismic arrays since 2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. and Y.C. collected the data, ploted some figures and joined the discussions; C. H. analyzed the data and wrote the main manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, CH., Lai, YC. & Shih, MH. Strong seismic reflections indicating possible eruptible magma beneath the Tatun Volcano Group in Taiwan. Sci Rep 15, 24333 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09558-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09558-y