Abstract

In this paper, an enhanced grid-side current and DC-bus voltage regulation method is proposed for a three-level neutral point clamped (NPC) four-leg rectifier (3LNPC-4LR) interfaces DC microgrid. Afractional-order extended state observer (FOESO) incorporated into an active disturbance rejection control (ADRC) is proposed for both the inner current and outer voltage control loops. The proposed FOESO-based ADRC aims to address critical challenges in 3LNPC-4LR by providing a robust control approach that ensures constant and fast dynamic DC-bus voltage, excellent grid-side current quality, and unit power factor, while guaranteeing good steady-state behavior under internal and external disturbances, including system uncertainty, coupling terms, and sudden change of linear and constant power loads,as well as grid voltage variations, which can adversely affect system performance and stability. Instead of proportional-inegral control and ESO-based ADRC methods, the FOESO-based ADRC method offers significant advantages in both control loops, including enhanced design flexibility, improved voltage and current tracking performance, superior disturbance rejection capabilities, reduced noise, high robustness to uncertainties and system variations, and increased system reliability with reduced cost and size. The effectiveness of the proposed method is validated through Hardware‐in‐the loop real-time simulations using OPAL-RT-OP5700 under varying loads, grid voltage conditions, system uncertainties, and constant power load.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DC microgrids have emerged as a promising solution for integrating distributed energy resources such as photovoltaic systems, fuel cells, and energy storage devices to the main power grid. These microgrids typically interface with the AC utility grid via three-phase rectifiers, which convert AC to DC for internal consumption. However, this interface introduces several power quality challenges into the distribution network. Conventional three-phase rectifiers are nonlinear loads that generate current harmonics, which distort the voltage waveform and adversely affect the performance of sensitive equipment1. In addition to harmonic issues, these rectifiers often consume lagging reactive power, thereby degrading the power factor, increasing the apparent power demand, and contributing to overall system losses and inefficiencies2.

To mitigate these adverse effects, various power quality enhancement techniques have been developed for use in AC distribution systems interconnected with DC microgrids. Active power filters are among the most commonly implemented solutions, effectively suppressing a wide range of harmonic components and improving current waveform integrity3. In addition, Distribution Static Compensators offer dynamic reactive power compensation capabilities, significantly enhancing power factor and stabilizing voltage levels under varying load conditions4. For more comprehensive power quality control, the Unified Power Flow Controller, which is a key member of the Flexible AC Transmission Systems family, can simultaneously manage both active and reactive power flows while also mitigating harmonics. These advanced compensation devices are vital for ensuring stable, efficient, and reliable operation of distribution networks interfacing with DC microgrids5.

In response to the need for improved performance and scalability, the three-phase three-level neutral-point-clamped (NPC) rectifier topology has gained widespread adoption across modern industrial and utility-scale applications. These AC/DC converters, often operating as active front-ends, utilize pulse-width modulation to generate DC power from the AC grid, offering several key advantages. These include bi-directional power flow, stable DC-link voltage with minimal ripple, reduced harmonic distortion in grid-side currents, enhanced power factor correction, and decreased voltage stress on switching devices through the neutral-point clamping mechanism6,7,8. For these reasons, NPC rectifiers are widely used in DC microgrids9,10, EV charging infrastructure11, power factor controllers12, and DFIG-based renewable energy systems13,14. Compared to traditional two-level converters, the three-level NPC topology supports higher power ratings and superior power quality, while also enabling compact design, reduced output filter requirements, and lower electromagnetic interference15,16.

The three-phase three-level NPC four-leg converter (3LNPC-4LC) offers significant performance enhancements over its three-leg counterpart by adding a fourth leg connected to the grid neutral, enabling superior common-mode voltage suppression, neutral current control, DC-link voltage balancing, and harmonic reduction17,18. This additional leg improves control flexibility, especially under unbalanced grid conditions, by providing a zero-sequence current path19,20. As a result, the 3LNPC four-leg rectifier (3LNPC-4LR) is well-suited for modern DC microgrids, offering high compatibility with renewable sources, fault ride-through, reactive power support, and adaptability to both resistive and constant power loads (CPLs)21. However, the system faces notable challenges under disturbances such as grid voltage sags/swells, sudden load changes, and CPL dynamics, which can destabilize the DC bus voltage22,23,24. In addition, parameter uncertainties in filter inductance and DC capacitance may degrade control performance and reliability25. These issues highlight the need for robust control strategies to ensure stable and reliable microgrid operation under varying conditions.

The dual cascade control loop structure (DCCLS) in the dqγ reference frame, comprising an inner grid-side current control loop (IGSCCL), an outer DC bus voltage control loop (OVCL), coordinate transformation, and PWM generation, is widely adopted for controlling grid-connected three-level NPC converters26,27. The IGSCCL regulates grid-side currents with fast dynamic response, harmonic compensation, and decoupling of d- and q-axis components, enabling unity power factor and robust performance against grid and filter uncertainties. The OVCL maintains DC bus voltage stability under load changes, CPL dynamics, and grid disturbances, while also compensating for power losses and generating the d-axis current reference for the IGSCCL. This DCCLSproves particularly effective during various disturbance scenarios: The inner loop provides immediate response to grid voltage fluctuations and harmonic distortion, while the OVCL ensures DC bus voltage stability during load transients and power variations, ultimately contributing to the overall system reliability and power quality improvement.

Although proportional-integral (PI) controllers are commonly adopted in both IGSCCL and OVCL for grid-connected converters28,29, they have several limitations, including slow dynamic response speed, lower robustness to parameter uncertainty, and high sensitivity to disturbances. These limitations become particularly apparent when the system experiences sudden connection, disconnection, or variation of CPLs. CPLs demonstrate nonlinear characteristics with inverse voltage-current relationships (\({P}_{CPL}={V}_{dc}{I}_{LCPL}\) constant), naturally introducing negative impedance characteristics that can destabilize the system. PI controllers cannot effectively track CPL disturbances and cannot adequately balance the opposing characteristics of CPLs.

To address the challenges of regulating grid-side currents and DC bus voltage in three-phase two- and three-level converters, researchers have proposed various feedforward compensation techniques. These include current feedforward methods based on load current sensing30, extended Kalman filters31, ESOs32, sliding mode state observers33, extended sliding mode disturbance observers34, super-twisting ESOs27, generalized proportional-integral observers35, and active disturbance rejection control (ADRC) strategies36,37. These methods aim to improve converter performance under disturbances and achieve precise control objectives.

Among these approaches, ADRC, developed by Han Jingqing as an evolution of PID control38, stands out for its ability to handle total disturbances, both internal and external. It does so by estimating disturbances through an ESO and compensating for them using a state error feedback loop (SEFL). Compared to traditional control methods, ADRC offers several advantages for PWM converters: Enhanced robustness to parameter variations and external disturbances, improved transient and steady-state performance, reduced sensitivity to nonlinearities, and ease of implementation. Moreover, it increases system reliability while minimizing complexity, cost, and size39,40.

In41, an ESO-based ADRC strategy was successfully applied to the inner grid-side current control loop (IGSCCL) of grid-tied single-phase inverters, effectively rejecting both internal and external disturbances. However, this work did not address voltage regulation through the OVCL. Subsequent studies extended ESO-based ADRC methods to OVCL applications in photovoltaic three-phase grid-connected inverters42 and single-phase cascaded H-bridge rectifiers43, achieving robust DC bus voltage control. Further implementations demonstrated the feasibility of using ADRC in both IGSCCL and OVCL for controlling grid currents and DC voltage in three-phase rectifiers44 and three-phase isolated matrix rectifiers45, successfully rejecting parameter uncertainties, load disturbances, grid fluctuations, and current coupling effects. Building on these successes, ESO-based ADRC was later adapted for photovoltaic three-phase grid-following LCL inverters46, where it provided accurate tracking of current and voltage references while maintaining effective disturbance rejection under dynamic grid and load conditions.

Although ESO-based ADRC methods have shown strong capabilities in tracking reference signals and rejecting disturbances in power converter systems, their performance can be compromised by measurement noise, particularly in industrial environments. According to observer theory, there is a fundamental trade-off between estimation speed and noise sensitivity in traditional ESOs33,47. To address this, moderate gain values are typically selected to balance rapid disturbance rejection with acceptable noise robustness48.

In34, an ADRC strategy incorporating an extended sliding mode observer was proposed for a 3LNPC-3LR-based DC microgrid to enhance voltage regulation under DC bus capacitor uncertainty and unknown load conditions. Compared to conventional ESO-based ADRC, this approach provides improved robustness, effective real-time disturbance estimation, reduced reliance on precise system models, and fast dynamic response to voltage fluctuations. Despite these advantages, the ESMO-based ADRC approach has significant drawbacks. This method can induce chattering that stresses power-switching devices and demands higher computational resources to resolve the unwanted effects. Moreover, it exhibits greater sensitivity to measurement noise and may increase implementation costs due to its complexity compared to traditional ESOs49,50.

Considering the challenges of robustness against system parameter uncertainties and external disturbances, finite-time convergence, chattering, and computational burden, an ADRC strategy based on the super-twisting observer (STO) has been proposed for regulating the DC bus voltage of a PV grid-connected LC four-leg inverter23. This method offers strong robustness against uncertainties such as DC capacitor variations, grid voltage fluctuations, irradiance changes, and PV cell temperature variations. A notable advantage of the STO is its ability to eliminate the chattering phenomenon common in conventional sliding mode observers while providing faster convergence and higher estimation accuracy. Additionally, its relatively simple structure enhances computational efficiency and practical implementation. However, the STO has several limitations. Its convergence speed deteriorates when system trajectories deviate significantly from the origin51,52, and its performance is highly sensitive to parameter tuning, particularly in balancing convergence speed against noise amplification27,51. In systems with high-frequency dynamics, the STO may exhibit reduced estimation accuracy52,53. Furthermore, during the reaching phase, STO-generated signals can include undesired high-frequency components, which may require additional filtering in sensitive power applications54.

To address the challenges of maintaining robust performance in the presence of uncertainties, disturbances, and measurement noise, this paper proposes a fractional-order extended state observer (FOESO)-based ADRC (FOADRC) strategy for both the IGSCCL and the OVCL of a 3LNPC-4LR used in DC microgrids. The proposed FOADRC method integrates a FOESO into the ADRC method to enhance the estimation and rejection of exogenous disturbances while improving noise immunity and steady-state accuracy. In the IGSCCL, the FOADRC regulates grid-side currents in the dqγ frame, effectively handling grid impedance variations, L-filter uncertainties, current coupling terms, and grid voltage fluctuations. Meanwhile, the OVCL manages the DC bus voltage by accounting for uncertainties in the output capacitor, sudden changes in load and grid voltage, and the dynamic behavior of CPLs. The core advantage of using FOESO in this context lies in its foundation in fractional calculus, where non-integer order derivatives provide a memory effect and non-local characteristics. This enables a more accurate estimation of system states and unknown disturbances over time.

Unlike traditional integer-order observers that rely solely on instantaneous signal values, fractional-order observers incorporate historical behavior, allowing them to capture long-term system dynamics and estimate slow-varying or complex disturbances more effectively. This richer and more flexible system representation makes FOESOs particularly well-suited for systems with nonlinearities and modeling uncertainties. The fractional-order control also introduces a tunable parameter that allows for fine-tuning of convergence speed, robustness, and noise immunity. Additionally, the inherent low-pass filtering effect of fractional derivatives enhances resistance to high-frequency noise without requiring external filters. Together, these features enable FOESOs to significantly outperform conventional ESOs in disturbance rejection and state estimation, especially in uncertain, noisy, or nonlinear environments, making them a powerful tool within ADRC frameworks for modern power electronic systems55,56,57.

For the modulation stage-based 3LNPC-4LR, the system implements the three-level offset carrier-based sinusoidal pulse width modulation (3L-OCSPWM) technique proposed by58. This offset approach delivers the advantages of the 3L-3DSVPWM technique while maintaining minimal computational complexity59,60,61. The design of this modulation technique is completed with a conventional PI controller in the output DC capacitor voltage balancing loop to provide a good DC-link capacitor voltage balance. Also, the synchronization unit proposed in62 is adopted in our work for its good dynamic responses and high robustness against grid frequency changes than the traditional Phase-locked loop (PLL). The main contributions of the paper can be summarized as follows.

-

A comprehensive dynamic model of the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid is developed, incorporating grid-side impedance, DC bus capacitor uncertainties, load disturbances, grid voltage fluctuations, grid-side current coupling, power losses, and unknown disturbances.

-

Both the OVCL and IGSCCL are designed using the proposed FOADRC strategy. The IGSCCL is implemented in the dqγ frame to decouple and eliminate disturbances caused by grid-side current coupling. Compared to conventional PI and ESO-based ADRC controllers, the proposed FOADRC offers superior tracking accuracy and disturbance rejection while retaining effective noise attenuation capabilities.

-

The robustness and stability of the proposed approach are analyzed in the frequency domain using Bode plots, demonstrating strong performance under a wide range of disturbances and parameter uncertainties.

-

Detailed analysis of stability, parameter tuning, and controller performance is provided, and real-time hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) simulations validate the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed FOADRC method.

-

The results show that the proposed FOADRC method improves the tracking performance of grid-side currents and DC bus voltage while enhancing disturbance estimation and rejection in both control loops, and maintaining the FOESO’s noise suppression capabilities.

Modeling of the three-level NPC converter

The 3LNPC-4LR plays a vital role in DC microgrid systems as power conversion interfaces. Operating as an active front end, this topology delivers regulated DC-bus voltage to the downstream circuits while maintaining sinusoidal grid-side currents at unity power factor. The system architecture, shown in Fig. 1, incorporates a 3LNPC-4LR connected to the grid source via the grid-side impedance(\({L}_{gs}\), \({R}_{gs}\)) that consists of the grid impedance (\({L}_{g}\), \({R}_{g}\)) and the L-R filter (\({L}_{f}\), \({R}_{f}\)) for power quality enhancement and to the DC microgrid via a DC capacitor (\({C}_{dc}\)) for voltage stabilization and ripple reduction. The three-phase grid voltages are denoted as \({v}_{gabc}\). The grid-side currents through the filter inductances are represented as \({i}_{abcn}\), while the DC bus voltage and 3LNPC-4LR output current are denoted as \({V}_{dc}\) and \({I}_{dc}\), respectively. The 3LNPC-4LRinput voltages are represented as \({v}_{rabc}\). The microgrid supports diverse load types, including conventional linear loads (such as resistive loads) and constant power loads (CPLs). CPLs typically comprise power electronic converters feeding linear loads or motor drives, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Grid-side current dynamics

According to Kirchhoff’s voltage law, the grid-side current dynamics of 3LNPC-4LR in Fig. 1 can be expressed mathematically in the three-phase system in terms of grid voltages and 3LNPC-4LR input voltages, as in Eq. (1).

The coordinate transformation between the three-phase system (denoted by superscripts a, b, c) and the synchronous reference frame (indicated by superscripts d, q, γ) enables simplified system analysis and control. This transformation, expressed in Eq. (2), converts three-phase quantities (\(X\)), such as voltages (\(v\)) and currents (\(i\)), into their corresponding dqγ components. The transformation angle \(\theta\), equal to \(\omega t\), represents the instantaneous phase angle of the grid voltages. This critical angle can be accurately extracted using the appropriate robust synchronization unit mentioned in62 for precise synchronization, as described in subsection"Inner FOADRC method for grid side current control design". When transforming the grid-side current dynamics in Eq. (1) to the synchronous reference frame using Eq. (2), the corresponding state-space representation in the dqγ frame is given by Eq. (3).

In Eq. (3), \(\omega\) represents the extracted grid voltage angular frequency, while \({v}_{rdq\gamma }\) serve as control inputs and \({i}_{dq\gamma }\) constitute the output variables for the 3LNPC-4LR grid-side system.

Usually, the feedforward decoupling method is widely adopted in the IGSCCL to eliminate the influence of grid-side current coupling terms (\(\omega {i}_{q}\) and \({\omega i}_{d}\)) in Eq. (3). The typical dqγ ideal control lows (\({v}_{rdq\gamma }^{*}\)) that represent the rectifier input reference voltages are given in Eq. (4), where \({u}_{rdq\gamma }\) are the dqγ feedback control laws that represent the drop voltage across the grid-side impedance in the dqγ frame, \({L}_{0gs}\) is the nominal value of the grid-side impedance, \({\omega }_{0}\) is the nominal value of the grid voltage angular frequency, \({v}_{0gdq\gamma }\) are the ideal dqγ grid voltage components in dqγ frame, and \({\omega }_{0}{L}_{0gs}{i}_{q}\) and \({\omega }_{0}{{L}_{0gs}i}_{q}\) are the feedforward decoupling terms of the inner d and q-axes grid side current control loop, respectively.

With:

Equation (4) reveals potential incomplete decoupling in the IGSCCL due to various unmeasurable grid-side system disturbances, including grid impedance parameter uncertainties, grid voltage fluctuations, and grid voltage angular frequency variations. These disturbances cannot be compensated through feedforward decoupling methods alone. Under closed-loop control, incomplete decoupling leads to current harmonics in the grid-side currents. While traditional PI-based IGSCCL can achieve satisfactory reference tracking, it struggles with disturbance rejection and harmonic elimination, highlighting an inherent trade-off between these performance objectives.

In the subsequent analysis, the effects of the dqγ grid voltage components fluctuations (\({v}_{gdq\gamma }\)), uncertainty in grid voltage angular frequency, cross-coupling (\(\omega {i}_{q}\) and \(\omega {i}_{d}\)), and grid-side parametric uncertainties are treated as external disturbances. Substituting Eq. (4) into Eq. (3), Eq. (5) can be written.

Consequently, when consider the fluctuations in dqγgrid voltage components and the uncertainty in grid voltage angular frequency, the model in Eq. (5) becomes:

\({\Delta v}_{gdq\gamma }={v}_{gdq\gamma }-{v}_{0gdq\gamma }\) are the dqγ grid voltage component fluctuations and \(\Delta {L}_{gs}\omega {i}_{dq}={L}_{gs}\omega {i}_{dq}-{L}_{0gs}{\omega }_{0}{i}_{dq}\) are the feedforward decoupling terms errors. In further modeling the grid-side system, the parameter

\(\frac{{R}_{gs}}{{L}_{gs}}\) and \(\frac{1}{{L}_{gs}}\) are considered withuncertainties, expressing they as \(\frac{{R}_{gs}}{{L}_{gs}}=\frac{{R}_{0gs}}{{L}_{0gs}}+\Delta \frac{{R}_{gs}}{{L}_{gs}}\) and \(\frac{1}{{L}_{gs}}=\frac{1}{{L}_{0gs}}+\Delta \frac{1}{{L}_{gs}}\) where \({R}_{0gs}\) represents the nominal value of \({R}_{gs}\) and \(\Delta\) accounts for parametric uncertainties. When these considerations are incorporated into Eq. (6), the 3LNPC-4LR AC-side system can be further represented by Eq. (7).

with: \({a}^{i}=-\frac{{R}_{gs}}{{L}_{gs}},{a}_{0}^{i}=-\frac{{R}_{0gs}}{{L}_{0gs}}\), \(\Delta {a}^{i}=\Delta \frac{{R}_{gs}}{{L}_{gs}}\), \({b}^{i}=\frac{1}{{L}_{gs}}\),\({b}_{0}^{i}=\frac{1}{{L}_{0gs}}\), and \(\Delta {b}^{i}=\Delta \frac{1}{{L}_{gs}}\).Thus, \(\Delta {a}^{i}={a}^{i}-{a}_{0}^{i}\) and \(\Delta {b}^{i}={b}^{i}-{b}_{0}^{i}\) are the grid-side parameter uncertainties. In this, the effect due to the grid voltage fluctuations, coupling terms, and gride-side parametric uncertainties are completely considered a disturbance in the gride-side system model. So, all disturbances in the grid-side system are combined as a single lumped disturbance (\({f}_{dq\gamma }^{i}\)) and treated in the proposed FOADRC method-based IGSCCL. This combined disturbance is estimated using the proposed FOESO and subsequently compensated through the control input in the SEFL. To facilitate this approach, the perturbed grid-side system model in Eq. (7) is transformed into an integral chain structure, as shown in Eqs. (8) to (10).

where \({f}_{dq\gamma }^{i}\) denote as dqγ total disturbances of the grid-side system that includes the grid voltage fluctuations (\({\Delta v}_{gdq\gamma }\) and \(\Delta \omega\)), errors in coupling terms (\(\Delta \omega {i}_{dq\gamma }^{i}\)), and gride-side parametric uncertainties (\({\varphi }_{Ldq0}=\Delta b{u}_{rdq\gamma }+{a}_{0}{i}_{dq\gamma }^{i}+\Delta a{i}_{dq\gamma }^{i}\)).

In Eq. (5), the parameter \({b}_{0}^{i}={L}_{0gs}^{-1}\) represents the gain of the control inputs \({u}_{rdq\gamma }\). The AC side system disturbances \({x}_{2dq\gamma }^{i}={f}_{1dq\gamma }^{i}\) are not directly measurable during operation and require real-time estimation. As discussed in subsection"Inner FOADRC method for grid side current control design", the proposed FOADRC-based IGSCCL employs an FOESO to generate the estimated disturbances \({\widehat{x}}_{2dq\gamma }^{i}\), which are used to counteract the effects of \({f}_{dq\gamma }^{i}\) on the AC side system. The FOESO structure utilizes \({u}_{rdq\gamma }\) and \({y}_{1dq\gamma }^{i}={x}_{1dq\gamma }^{i}\) as inputs and outputs respectively, based on two key assumptions: the extended states \({x}_{2dq\gamma }^{i}={f}_{1dq\gamma }^{i}\) are differentiable, and the function \({\dot{x}}_{2dq\gamma }^{i}={\dot{f}}_{dq\gamma }^{i}={h}_{dq\gamma }^{i}\) remains bounded. This formulation leads to the state-space representation shown in Eq. (11), which forms the foundation for the detailed proposed FOADRC design used in the IGSCCL presented in subsection"Inner FOADRC method for grid side current control design".

where, \({X}_{dq0}^{i}={\left[{x}_{1dq\gamma }^{i},{x}_{2dq\gamma }^{i}\right]}^{\text{T}}\) and \({Y}_{dq\gamma }^{i}\) are the internal states and output of the AC side system in the dqγ frame. A, B, C and D represent the grid-side system parameters matrix, the control inputs gain matrix, output matrix, and total disturbance matrix, respectively, which can be defined as follows:

DC bus voltage dynamic

At first, to model the 3LNPC-4LR DC-side system, the 3LNPC-4LR switching, and input inductance filter power losses are modeled by a resistance \({R}_{loss}\). Thus, according to Fig. 1, the DC bus voltage dynamics can be expressed through the current variation in the dc-bus as follows:

where, \({i}_{C}\) indicates the current in the DC capacitor, \({I}_{dc}\) indicates the injected DC current of the 3LNPC-4LR system from ac-side to dc-side, \(\frac{{V}_{dc}}{{R}_{loss}}\) indicates the total switching losses of the 3LNPC-4LR system, and \({I}_{L}\) is the consumed current by the load connected to the dc-side, which consists of both the resistive load and CPL currents.

where, \({I}_{LR}\) and \({I}_{LCPL}\) indicate the resistive load current and the CPL current, respectively.

Consequently, the DC bus voltage dynamics in Eq. (12) becomes:

In the dc-side system, the modeling approach also incorporates parameter uncertainty in the DC capacitor \({C}_{dc}\), expressing it as \({C}_{dc}={C}_{dc0}+\Delta {C}_{dc}\), where \({C}_{dc0}\) represents the nominal DC capacitor value and \(\Delta {C}_{dc}\) accounts for parametric uncertainties. When these considerations are incorporated into Eq. (4), the 3LNPC-4LR AC-side system can be further represented by Eq. (15).

where, \({\varphi }_{C}\) represents the DC-side system parameter uncertainties due to variations in the DC capacitor.

Under steady-state conditions, assuming that the proposed controller compensates for the 3LNPC-4LR losses, the AC input power \(\left({P}_{ac}\right)\) becomes approximately equal to the DC output power \(\left({P}_{dc}\right)\). Consequently, and according to the concept of instantaneous power theory in63, the relationship between the AC side and the DC side of the 3LNPC-4LR can be expressed as in Eq. (16).

According to the Voltage Oriented Control concept in the dqγframe when the d-axis grid voltage is aligned with the grid voltage vector which results in the d component of grid voltage (\({v}_{gd}\)) equaling the magnitude of the grid voltage vector (\({V}_{gmax}\)) while the q component (\({v}_{gq}\)) becomes zero25. Thus, the Eq. (16) becomes:

From this equation, the output DC current can be expressed as in Eq. (18)

where the ration (\(\frac{{v}_{gd}}{{V}_{dc}}\)) can guarantee the power balance between both sides of the 3LNPC-4LR system.

Taking into consideration the impact of grid-side current (\({i}_{d}\)) on the DC-side current (\({I}_{dc}\)), DC bus voltage dynamics in Eq. (15) can be rewriting as in Eq. (19).

Now, Eq. (19) can be simplified to Eq. (20) to establish the DC bus voltage dynamics that form the basis for designing the proposed FOADRCin the OVCL.

where, \({b}_{0}^{v}={C}_{dc0}^{-1}\frac{{v}_{gd}}{{V}_{dc}}\) is the control gain of the control input \({i}_{d}^{*}\) and \({f}^{v}=-{C}_{dc0}^{-1}\left(\frac{{V}_{dc}^{2}}{{R}_{loss}}+{I}_{LR}+{I}_{LCPL}\right)+{\varphi }_{C}\) represent unmodeled disturbances due to system losses, DC microgrid loads, DC capacitor parameter variations, and grid uncertainty. All disturbances in the DC-side system are combined also as a single lumped disturbance (\({f}^{v}\)) and treated in the proposed FOADRCmethod-based OVCL. This combined disturbance is also estimated using the proposed FOESO and subsequently compensated through the control input in the SEFL. To facilitate this approach, the dc-side system model with uncertainties in Eq. (21) is transformed into an integral chain structure, as shown in Eqs. (6) and (15).

The dc-side system disturbances \({x}_{2}^{v}={f}^{v}\) are also not directly measurable during operation and require real-time estimation. As discussed in subsection"Outer FOESO-based ADRC method for DC bus voltage control design", the ADRC-based OVCL employs an FOESO to generate the estimated disturbances \({\widehat{x}}_{2}^{v}\), which is used to counteract the effects of \({f}^{v}\) on the dc-side system. The proposed FOESO structure-based OVCL utilizes \({i}_{d}^{*}\) and \({y}^{v}={x}_{1}^{v}\) as input and output respectively. This formulation leads to the state-space representation shown in Eq. (12), which forms the foundation for the detailed proposed FOADRC design used in the OVCL presented in Section III-B.

where, \({\dot{X}}^{v}={\left[{x}_{1}^{v},{x}_{2}^{v}\right]}^{\text{T}}\) and \({Y}^{v}\) is the internal state and output of the dc-side system. \({A}_{v}\), \({B}_{v}\), \({C}_{v}\) and \({D}_{v}\) represent the dc-side system parameters matrix, the control input gain matrix, output matrix, and total disturbance matrix, respectively, which can be defined as follows:

Proposed control methodology

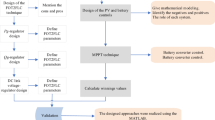

Instead of traditional methods that use either PI controllers or conventional ESO-based ADRC methods in both the IGSCCL and OVCL, this paper proposes a FOADRC method for both IGSCCL and OVCL of a 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid system. Figure 2 illustrates the overall control structure with the FOADRC method, which is implemented according to the following methodology.

-

Step 1: Measure the DC-bus voltage (\({V}_{dc}\)) using a voltage sensor. Apply the proposed FOADRC method in the OVCL to regulate it toward its reference (\({V}_{dc}^{*}\)), ensuring robustness against disturbances from load variations, grid voltage fluctuations, and capacitor parameter changes. This step also generates the d-axis reference current (\({i}_{d}^{*}\)) for the grid side.

-

Step 2: Measure the grid-side currents (\({i}_{abcn}\)) via current sensors and apply the Park transformation (Eq. (2)) to extract the \({i}_{d}\), \({i}_{q}\) and \({i}_{0}\) components, which serve as control variables in the IGSCCL. The grid voltage phase angle \(\theta\) is obtained using the robust synchronization unit mentioned in63 for precise synchronization as described in Section"3LNPC-4LR synchronization unit".

-

Step 3: Implement the FOADRC method in the IGSCCL to regulate grid-side currents and reject disturbances due to AC-side parameter uncertainties, coupling effects, and grid fluctuations. The OVCL provides \({i}_{d}^{*}\) for accurate regulation of \({i}_{d}\), while \({i}_{q}^{*}\) and \({i}_{0}^{*}\) are set to zero for unity power factor and no zero-sequence current injection. The FOADRC design assumes: (1) grid impedance and L-filter variations are treated as external disturbances, (2) all AC-side disturbances are uniformly bounded64, and (3) load demands remain within bounds to avoid violating current constraints65.

-

Step 4: Generate the three-phase voltage references (\({v}_{rabc}^{*}\)) by applying the inverse Park transformation to the dqγ voltage references (\({v}_{rdq0}^{*}\)) obtained from the IGSCCL. These serve as modulation signals for the 3L-OCSPWM technique.

-

Step 5: Apply the 3L-OCSPWM to generate switching pulses for the 3LNPC-4LR, where the inputs to the three-level OCSPWM approach are the initial three-phase input voltage references (\({v}_{rdq0}^{*}\)) with its offset voltage (\({v}_{of}\)) and the NP voltage stabilization term provided from the regulation of the DC capacitor voltages. The regulation of the DC capacitor voltages is used to stabilize the voltages of the two DC capacitors, which is performed using a simple PI regulator7.

Inner FOADRC method for grid side current control design

This subsection details the design of the proposed FOADRC method for the IGSCCL, based on the state-space model of the second-order perturbed AC-side system given in Eq. (11). The FOADRC is employed to estimate the internal state variables (\({x}_{1dq\gamma }^{i}\)) from the measured grid-side currents (\({i}_{dq\gamma }\)). The extended state variable \({x}_{2dq\gamma }^{i}\) represents the total disturbance \({f}_{dq\gamma }^{i}\) affecting the system. The control objective is to regulate \({i}_{dq0}\) via the control input \({v}_{rdq0}\), where the input gain \({b}_{0}^{i}={L}_{0gs}^{-1}\) is derived from the grid filter inductance. The estimation error \({\varepsilon }_{1dq\gamma }^{i}={x}_{1dq\gamma }^{i}-{\widehat{x}}_{1dq\gamma }^{i}\) is minimized in steady-state, indicating accurate tracking performance of the IGSCCL. As the observer states estimated states \({\widehat{x}}_{1dq\gamma }^{i}\) converge to the actual states \({x}_{1dq\gamma }^{i}\) and \({\widehat{x}}_{2dq\gamma }^{i}\) converges to the total disturbance \({f}_{dq\gamma }^{i}\), the FOADRC effectively compensates for uncertainties in the dqγ frame. This framework enables a robust FOADRC design using the observed external disturbance based on the proposed FOESO, as expressed in Eq. (23).

In this equation, the Caputo fractional-order derivative operator, denoted as \({D}_{t}^{{\alpha }_{\text{1,2}}^{i}}\), operates with orders \({\alpha }_{1}^{i}\) and \({\alpha }_{2}^{i}\) confined to the interval [−1, 1], as detailed in65. The system incorporates gain coefficients of fractional-order components \({k}_{1}^{i}\) and \({k}_{2}^{i}\), while \({\beta }_{1}^{i}\) and \({\beta }_{2}^{i}\) represent traditional ESO gains.

In this, the total disturbances (\({f}_{dq\upgamma }^{i}\)) can be employed as feed-forward compensation terms for the grid-side system control input (\({v}_{rdq\upgamma }^{*})\)44. Consequently, it is possible to redefine the final control law of the ADRC-based IGSCCL, as given in Eq. (24).

where, \({u}_{0dq0}^{i}\) are the initial dqγ control laws of the SEFL-based ADRC for the IGSCCL that represent the initial values of the grid-side system dqγ control inputs, which are given by.

where \({x}_{1dq\upgamma }^{i*}={i}_{dq\upgamma }^{*}\) are dqγ grid side current references obtained from the OVCL and \({k}_{sef}^{i}\) is the SEFL proportional controller gain of the ADRC method–based IGSCCL, which is selected as a trade-off between transient and steady state performance.

The 3LNPC-4LR input voltage references (\({v}_{rdq\gamma }^{*}\)) that represent the initial voltage modulations in the dqγ frame are given by:

The schematic of the proposed FOADRC-based IGSCCL is shown in Fig. 3. From this figure and Eq. (23), it can be seen that the proposed FOESO will regress into the form of traditional ESO when \({k}_{1}^{i}={k}_{2}^{i}=0\).

Outer FOESO-based ADRC method for DC bus voltage control design

In this subsection, a FOADRC is designed in the OVCL for the ds-side of the 3LNPC-4LR based on the state-space representation in Eq. (22). Based on \({V}_{dc}\), the first state variable (\({x}_{1}^{v}\)) of the second-order perturbed system in Eq. (22) is further evaluated using FOESO. The second state variable \({x}_{2}^{v}\) corresponds to the dc-side total disturbance \({f}^{v}\). The objective here is to control \({V}_{dc}\) through the dc-side system control input \({i}_{d}^{*}\), where \({b}_{0}^{v}\) is the input gain based on theDC capacitornominal value. Consider \({\varepsilon }_{1}^{v}={x}_{1}^{v}-{\widehat{x}}_{1}^{v}\) as a small steady-state error while tracking the estimated state variable \({\widehat{x}}_{1}^{v}\) with the actual state variable \({x}_{1}^{v}\) of the dc-side system. This enables the design of the proposed FOADRC method for the OVCL, as expressed in Eq. (27).

In this, the total disturbances (\({x}_{2}^{v}={f}^{v}\)) can be used as feed-forward compensation terms for the dc-side system control input (\({i}_{d}^{*})\). Consequently, the final control law (\({{u}^{v}=i}_{d}^{*}\)) of the FOADRC-based OVCL is to achieve the compensation of the total disturbances (\({x}_{2}^{v}={f}^{v}\)) and stabilize the dc-side closed-loop system, as given in Eq. (28).

In order to track the desired DC-bus voltage reference (\({x}_{1}^{v*}={V}_{dc}^{*}\)) under any disturbance, an appropriate initial control law (\({u}_{0}^{v}\)) that represent the initial value of the dc side system control input is implemented in the SEFL-based ADRC of the OVCL as given in Eq. (29).

where \({k}_{sef}^{v}\) is the SEFL proportional controller gain of the ADRC method–based OVCL.

Substituting Eqs. (29) and (28) into Eq. (19), Eq. (30) can be written.

According to Eq. (30), the final control law (\({i}_{d}^{*}\)) of the proposed FOADRC-based OVCL mentioned in Eq. (28) can stabilize the dc-side system when \({k}_{sef}^{v}>0\) is satisfied. Finally, the schematic of FOLADRC method-based OVCL is presented in Fig. 4.

In this work, instead of applying low-pass filters to the grid-side current and DC voltage sensor outputs before feeding them into the fractional-order observer, the proposed FOADRC-based OVCL architecture in both control loops regulates the estimated internal states rather than the directly measured sensor signals. This approach not only enhances the steady-state performance of both control loops but also helps mitigate the impact of measurement noise, without significantly affecting the dynamic estimation quality. The same regulation principle is employed in both inner and outer loops of the overall control scheme for the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid, as illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4.

3LNPC-4LR synchronization unit

In this section, as shown in Fig. 5, a robust synchronization unit proposed in62 is adopted for system synchronization. This unit aims to rapidly track the frequency of three-phase grid voltages with high robustness against voltage frequency variations. Compared to the traditional PLL technique, the method offers superior dynamic response under grid voltage and grid-side impedance changes. The synchronization method’s mathematical structure is fundamentally frequency-dependent, with dynamics controlled by both the phase angle \(\theta\) and scaled frequency disturbance \(\Delta \omega\). This characteristic enables good dynamic responses and high robustness against frequency changes. The dynamics of both phase angle and frequency disturbance of this method are characterized by the following equation62:

where \({l}_{1}\) and \({l}_{2}\) are positive gains.

PWM switching singles generator

While the two control loops and their associated strategies are critical for achieving the desired control performance and dynamic response in the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid, the modulation stage, specifically the PWM switching signal generator, also plays a vital role. It significantly affects input voltage quality, neutral-point (NP) voltage balance, stress on DC bus capacitors and switching devices, and overall DC bus voltage utilization. Due to its impact, modulation has received considerable attention in the literature66,67,68.

In this paper, as illustrated in Fig. 6, a 3L-OCSPWM technique, as proposed in55, is adopted for generating PWM signals. This method shares the key characteristics of the 3L-3DSVPWM in the αβ0 reference frame55,56,57,58, but offers superior DC bus capacitor voltage stabilization with significantly reduced complexity, making it easier to implement. The algorithm for this PWM method is defined as follows:

According to55, the offset voltage term used in the multilevel four-leg converters is given by:

With:

The MOD function enables the consolidation of multiple carriers into a unified carrier, allowing for direct comparison with modulation voltages. This is particularly useful in multilevel inverter applications where you might otherwise need to handle multiple carriers separately. By using the MOD function, the modulation process becomes more streamlined and computationally efficient.

The modulation voltages of the 3L OCSPWM technique (\({v}_{oabc}^{*}\)) are expressed as a function of the inverter output voltage references (\({v}_{rabc}^{*}\)) provided from the regulation of the output currents and the offset voltage (\({v}_{of}\)) as follows:

where \(v\) is an introduced voltage balancing term provided from the regulation of the DC capacitor voltages of the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid to maintain their balance, which is given by:

Parameter tuning and performance analysis of the proposed FOLADRC

Proper tuning of the proposed fractional-order active disturbance rejection control (FOADRC) system is essential for effective control of the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid. Correct parameter settings enhance system performance by improving voltage and current quality, ensuring system stability, and providing strong disturbance rejection. This section outlines a systematic method for tuning the FOADRC parameters in both inner and outer control loops to meet desired performance criteria such as fast response, robustness, and steady-state accuracy. Since both control loops use the same FOESO structure, we focus here on tuning the FOESO-based OVCL. Initially, the parameters of the traditional ADRC based on an integer-order ESO are identified using Eqs. (37) and (38). These settings impact key metrics such as observation accuracy, disturbance estimation, and system stability.

According to the state-space representation of the ESO-based ADRC method of the OVCL in Eq. (31) (\({k}_{1}^{v}={k}_{2}^{v}=0\)), the closed-loop transfer function between the extended state (\({f}^{v}\)) and the corresponding observed disturbance (\({\widehat{f}}^{v}\)) is expressed by:

where \({\beta }_{1}^{v}\) and \({\beta }_{2}^{v}\) can be chosen as follows22,46:

where, \({\omega }_{eso}^{v}\) is the bandwidth of the ESO-based ADRC of the OVCL.

The SEFL gain \({k}_{sef}^{v}\) is selected as a trade-off between steady state performance and dynamic responses according to46 as:

where, \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{v}\) is the bandwidth of the SEFL-based ADRC of the OVCL.

Similar to the ADRC of the OVCL, the parameters (\({\beta }_{\text{1,2}}^{i}\) and \({k}_{sef}^{i}\)) of the ADRC-based IGSCCL are given by:

where, \({\omega }_{eso}^{i}\) and \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{i}\) are respectively the bandwidth of the ESO and ESF uses in the ADRC-based IGSCCL. Both ESOs can be used here to ease the process of tuning parameters of the proposed FOESO.

In DCCLS used in the control of power converters, the bandwidth of the SEFL-based IGSCCL \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{i}\) is typically set between one-fifth and one-tenth of the converter’s switching frequency \({\omega }_{sw}=2\pi {f}_{sw}\)69,70, while the bandwidth of SEFL-based OVCL (\({\omega }_{c,sef}^{v}\)) should be lower than \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{i}\), typically \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{v}\approx 1/5\text{ to }1/10\) of \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{i}\). This ensures that the IGSCCL responds faster than the OVCL, avoiding unwanted interactions between the two control loops71,72,73,74.

Additionally, for each loop, the bandwidth of the ESO, \({\omega }_{eso}^{v,i}\), should be about 3 to 5 times higher than the SEFL bandwidth \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{v,i}\), so that the ESO can estimate disturbances quickly and accurately46,72. However, setting the ESO bandwidth too high can increase sensitivity to noise and degrade overall controller performance47,48. Therefore, ESO bandwidths must be carefully selected to balance estimation speed and noise sensitivity. So, the ESO bandwidths \({\omega }_{eso}^{v}\) and \({\omega }_{eso}^{i}\) must be adjusted to achieve acceptable transient behavior of both ESOs in terms of both the load disturbance rejection ability and estimation error dynamics.

To do this, a range of ESO bandwidths are tested. For each case, the behavior of both the 3LNPC-4LR system and the ESO is evaluated to choose the best-performing settings. Figure 7 shows the Bode plots of the estimation error transfer function as \({\omega }_{eso}^{i}\) is varied between 1/5 to 1/10 of the \({\omega }_{sw}\) with an incremental frequency value of 716 rad/s. The results show that increasing \({\omega }_{eso}^{i}\) beyond a certain point does not significantly improve ESO performance. Thereby, in this work, \({\omega }_{eso}^{i}\) is set to 8792 rad/s and \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{i}\) is set to 2930 rad/s. According to thus and to avoid interaction between both control loops, \({\omega }_{eso}^{v}\) is set to \(0.1{\omega }_{eso}^{i}=293\) rad/s and \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{v}\) is set to 60 rad/s.

On the condition that \({\omega }_{eso}^{v,i}\) and \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{v,i}\) keep constant (\({\omega }_{eso}^{i}\)= 8792 rad/s and \({\omega }_{c,sef}^{i}\)=2930 rad/s), the fractional orders (\({\alpha }_{v1}\) and \({\alpha }_{v2}\)) and gain values (\({k}_{1}^{v}\) and \({k}_{2}^{v}\)) of the proposed FOADRC method are determined by the assessment of the extended state estimation error using its transfer function \({G}_{\varepsilon 2}^{v}\left(s\right)\) in Eq. (41) (see Supplementary material):

The extended state estimation error transfer function from Eq. (41) shows how the disturbance \({f}^{v}\) affects the estimation error \({\varepsilon }_{2}^{v}\). This transfer function includes both integer-order terms (\({s}^{2}+{\beta }_{1}^{v}s\)) and fractional-order terms (\({k}_{1}^{v}{\beta }_{1}^{v}{s}^{{(\alpha }_{v1}+1)}+{k}_{2}^{v}{\beta }_{2}^{v}{s}^{{\alpha }_{v2}}\)), classifying it as a fractional-order system. A key advantage of the proposed FOESO over the traditional ESO is its use of these tunable fractional-order terms. They allow more flexible placement of the transfer function poles, enabling better control performance. This flexibility comes from adjusting four key parameters: \({k}_{1}^{v}\), \({k}_{2}^{v}\), \({\alpha }_{v1}\), and \({\alpha }_{v2}\). Despite this new structure, the FOESO remains compatible with the traditional ESO architecture but offers a much wider design space.

To understand how these parameters affect performance, we analyzed the frequency response of the FOESO using Bode plots under the following different settings:

-

Case 1: Set \({\alpha }_{v1}\)=\({\alpha }_{v2}\)= − 0.5, \({k}_{1}^{v}\)=1000, and varied \({k}_{2}^{v}\) across 1, 10, 100, and 1000. The corresponding Bode plots arepresented in Fig. 8(a)

-

Case 2: Set \({\alpha }_{v1}\)=\({\alpha }_{v2}\)= − 0.5, \({k}_{2}^{v}\)=1000, and varied \({k}_{1}^{v}\) across 1, 10, 100, and 1000. The corresponding Bode plots arepresented in Fig. 8(b)

-

Case 3: Fixed \({k}_{1}^{v}\)=\({k}_{2}^{v}\)=100, \({\alpha }_{v2}\)= − 0.5, and varied \({\alpha }_{v1}\) through the values − 0.1, − 0.2, − 0.4, − 0.6, and − 0.8 (Fig. 8c).

-

Case 4: Fixed \({k}_{1}^{v}={k}_{2}^{v}=\) 100, \({\alpha }_{v1}\)= − 0.5, and varied \({\alpha }_{v2}\) from − 0.1 to − 0.8 (Fig. 8d).

These tests helped identify how changes in the fractional orders and gains influence the observer’s behavior and frequency response.

The analysis of the FOESO settings shown in Fig. 8 indicates that the best performance is achieved when the fractional orders \({\alpha }_{v1}\) and \({\alpha }_{v2}\) are between –0.4 and –0.6, and the gain values \({k}_{1}^{v}\) and \({k}_{2}^{v}\) are between 10 and 1000. It can be seen that the fractional orders can significantly influence the system’s response characteristics and the gain values also involve a trade-off between stability, disturbance observation and rejection, and noise reduction, in which:

-

More negative values (–0.6 to –0.8) lead to faster responses, but they also make the system more sensitive to noise and can cause oscillations.

-

Less negative values (–0.1 to –0.4) give smoother responses, but they are slower and less effective at rejecting disturbances.

-

High gains (greater than 100) improve disturbance rejection and reduce mid-frequency noise, but they can increase sensitivity to high-frequency noise and may reduce stability.

-

Moderate gains (10 to 100) offer the best balance between stability, accurate disturbance observation, and overall system performance.

Based on this analysis, the optimal configuration (\({\alpha }_{v1}\), \({\alpha }_{v2}\) ≈ −0.4 to – 0.6, \({k}_{1}^{v}\),\({k}_{2}^{v}\) ≈ 10 to 100) ensures robust operation across all frequency ranges by providing the best compromise between response speed, stability, noise sensitivity, and disturbance rejection capabilities.

These settings provide a good balance of speed disturbance observation, stability, and noise resistance. Therefore, in this study, we chose \({\alpha }_{v1}\)=\({\alpha }_{v2}\)=−0.52, \({k}_{1}^{v}=80\) and \({k}_{2}^{v}\)=84.

It’s important to note that the same parameters used in the traditional ESO-based ADRC are also applied in the proposed FOESO-based ADRC for each control loop. While this simplifies implementation, it might limit the flexibility of tuning for different system dynamics.

HIL real-time simulation results

In this section, the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed FOADRC method for the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid system, shown in Fig. 2, was validated using HIL real-time simulations on an OPAL-RT 5700 simulator, as shown in the HIL real-time simulation setup in Fig. 9. The performance of the proposed FOADRC method was compared against cascade PI control method and ESO-based ADRC method presented in46 to evaluate the proposed control method in terms of dynamic response optimizations, DC bus voltage regulation, grid-side current quality, robustness to parameter uncertainties, and disturbance rejection capabilities. The system was tested against various external disturbances, including sudden changes in both DC linear resistive and constant power loads, system parameter variations, and grid voltage variations. All system and controller parameters are detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

Transients and steady state behaviours under linear resistive load changes

To examine the performance of the three control methods, PI controller, traditional ESO-based ADRC, and the proposed FOADRC, in terms of dynamic response, disturbance rejection, and power quality, HIL real-time simulations were carried out. The system initially operated with a 450 Ω linear resistive load connected to the DC bus, no CPL, and a fixed grid voltage of 211 V. At 0.2 s, a second 450 Ω resistor was connected in parallel to the first, and then disconnected at 0.3 s. This sudden load change scenario allowed a comparative analysis of how each control method handles disturbances. The HIL test results, shown in Figs. 10a to 10c, including DC bus voltage, grid-side three-phase and natural currents, and dqγ frame currents. The grid-side current’s THD values during the load decrease period are presented in Figs. 11a to 11c.

HIL real time simulation results under linear resistive load variations: (a) PI controllers, (b) traditional ESO-based ADRC method in46, (c) proposed FOADRC.

Spectrum harmonic of first phase grid side current when the grid voltage frequency is set to 49.5 Hz: (a) PI controllers, (b) traditional ESO-based ADRC method in46, (c) proposed FOADRC.

Figures 10a illustrates the HIL test results of the PI controller method. As illustrated in these results, when the second linear resistive load is connected at t = 0.2 s and disconnection at t = 0.3 s, the DC bus voltage drops and swells by 12 V corresponding to these changes with a 30 ms convergence time during connection and disconnection of the second linear resistive load, with an overshot and undershot of 6 V (Fig. 10a). These are accompanied by an increase in grid-side current magnitude to about 3 A to maintain power delivery to the DC loads and ensure power balance between both sides of the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid during increased linear resistive load power demand caused by connection of the second linear resistive load, and decrease to its initial value of 1.5 A corresponding to the nominal load to maintain power balance between both sides of the 3LNPC-4LR during decreased linear resistive load power demand caused by disconnection of the second linear resistive load, requiring 22 ms convergence time to increase or decrease and with an overshot of 8 A in both cases, as evidenced by the three-phase grid-side current waveforms (iabc) in Fig. 10b and its d-axis component (id) in Fig. 9a. Moreover, this cascade PI control method leads to degraded DC bus voltage and grid-side current waveform quality before and after the linear resistive load change. The DC bus voltage has a very well ripple, which is about 0.04 V, and the grid-side currents exhibit increased ripples and harmonic content, resulting in a high THD value of 3.98%, as shown in Fig. 11a.

Figure 10b illustrates the HIL results of the traditional ESO-based ADRC method presented in46. It can be seen from these results that the ESO-based ADRC method can provide improved dynamic response and disturbance rejection capabilities during sudden changes of linear resistive load, overshot, and undershot, along with improved DC bus voltage and grid-side current quality during steady-state operation then the PI controller method. As illustrated in Figs. 10b, when the second linear resistive load is connected and disconnected, the ESO-based ADRC method presented in46 can reduce the DC bus voltage drops and swells to about 5 V with an18 ms convergence time during connection and disconnection of the second linear resistive load, and without any overshot or undershot (Fig. 10b), while the grid-side current convergence time is reduced to 8.3msin both increase or decrease magnitude without any overshot or undershot. Furthermore, this control method yields improved DC bus voltage and grid-side current waveform quality before and after the linear resistive load change. The ESO-based ADRC method presented in46 demonstrates reduced DC bus voltage and grid-side current ripples compared to the traditional PI controller, as evidenced in Figs 10a and Fig10b. The DC bus voltage ripple using this control method reduces to about 0.02 V, as shown in Fig. 10b, and the THD of grid currents reduces to 1.94%, as shown in Fig. 11b.

In contrast, as shown in Fig. 10c, the proposed FOADRC method can further reduce DC bus voltage deviations (drops and swell) and minimize convergence times of both OVCL and IGSCCL during sudden linear resistive load changes, as well as decrease DC bus voltage ripples and grid-side current harmonics during steady-state operation. The dynamic response and disturbance rejection capabilities of both OVCL and IGSCCL, along with DC bus voltage and grid-side current quality are significantly enhanced obviously. As illustrated in Fig. 10c, when the second linear resistive load is connected and disconnected, both the DC bus voltage drops and swells decreases to about 2 V with a very short convergence time of 8ms, while the grid-side current magnitude requires a convergence time of only 4 ms to increase to its new magnitude of 3 A during the sudden increase of linear resistive load power demand and decrease to its initial magnitude of 1.5 A during the sudden decrease of linear resistive load power demand. The proposed FOADRC method also reduced both the DC bus voltage ripple to approximately 0.012 V, as evidenced in Fig. 10c, and the THD of grid side currents to 0.79%, as shown in Fig. 11c.

In comparison to both the cascade PI control method and the traditional ESO-based ADRC method presented in46, the proposed FOADRC method demonstrates superior performance under varying linear resistive load conditions. It can reduce the DC bus voltage deviations by 83.33% then cascade PI control method and by 60% then the traditional ESO-based ADRC method, also it can reduce the DC bus voltage convergence time by 73.33% than the PI controller and by a 55.55% than the traditional ESO-based ADRC method, while the grid-side current convergence time is reduced by 81.81% than the PI controller and by 53.75% than the traditional ESO-based ADRC method. Additionally, the decrease of grid-side current THD is 80% of the cascade PI control method and 60% of the traditional ESO-based ADRC method.

The proposed FOADRC method implemented in both OVCL and IGSCCL achieves superior performance in dynamic response and disturbance rejection during sudden linear resistive load changes, as well as DC bus voltage ripple and grid-side current harmonic suppression during steady-state operation. These improvements stem from the FOESO’s inherent characteristics, including rapid disturbance estimation and rejection capabilities, swift convergence time, and enhanced steady-state performance, making it the most effective solution for handling disturbance caused by the sudden change of linear resistive load in the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid system.

The numerical outcomes of this evaluation are presented in Table 3, which summarizes the settling time, overshoot, undershoot, and Integral Time Absolute Error (ITAE) for both the DC bus voltage and the grid-side current. It also includes the THD of the grid-side current under the application of the three different control strategies. The ITAE values for the voltage and current control loops were determined using Eq. (42). As seen in Table 3, the proposed control strategy consistently achieves better performance across all evaluated metrics for both control loops when compared to the other control methods.

Transients and steady state behaviours during sudden integration of CPL.

In this scenario, evaluate the proposed control method’s capability in terms of dynamic response optimization, disturbance rejection capabilities, and quality of DC bus voltage and grid-side current during CPL integration. The system was initially configured with a 450 Ω linear resistive load connected to the DC bus at a constant grid voltage magnitude of 211 V. A 450 W CPL was then connected in parallel to the initial linear resistive load at 0.2 s and disconnected at 0.3 s. The HIL results for this scenario are presented in Fig 12a, Fig 12b and Fig 12c.

HIL real time simulation results under connection and disconnection of 450 W CPL: (a) PI controllers, (b) traditional ESO-based ADRC method in46, (c) proposed FOADRC.

The HIL test results of this test show that the traditional PI controller exhibited the poorest performance in terms of disturbance rejection ability and convergence times during both connection and disconnection of the CPL, as shown in Fig. 12a. Additionally, after the disconnection of the CPL at t = 0.3 s, the DC bus voltage becomes unstable, creating larger oscillation in the gride side currents. This is due to the inherent trade-off between stability margin and dynamic performance. In contrast, the proposed FOADRC method demonstrated superior performance by effectively compensating for DC-bus voltage fluctuations with faster convergence times, showing high robustness and stability against CPL connection and disconnection of CPL, as shown in Fig. 12c. Furthermore, the proposed FOADRC approach significantly enhanced both the dynamic responses and steady-state performance of the grid-side currents. This improvement enabled the IGSCCL to respond rapidly to disturbances caused by CPL connection and disconnection, effectively adjusting the magnitude of grid-side currents to meet CPL demands while maintaining the unity power factor and reducing neutral current oscillations. During CPL connection and disconnection events, the DC bus voltage responded immediately and accurately tracked the reference value with a convergence time of less than 10.5 ms. These results confirm the capability of the proposed control method-based both control loops in controlling the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid with very good stability, disturbance rejection ability, and convergence times, as well as steady-state performance during connection and disconnection of the CPL.

These improvements stem from the FOESO’s inherent characteristics in handling disturbances caused by the connection or disconnection of CPLs. The proposed FOADRC method effectively manages the contrasting behavior of CPLs, which demonstrate nonlinear characteristics with inverse voltage-current relationships (\({P}_{CPL}={V}_{dc}{I}_{LCPL}\) constant). The FOESO’s capability to estimate and compensate for nonlinear load behavior is crucial, as it handles the inverse relationship where current increases as voltage decreases during CPL connection or disconnection events. The FOESO structure provides better tracking of CPL disturbances while effectively balancing the opposing characteristics of CPLs, which naturally introduce negative impedance characteristics that can destabilize the system. This balance is achieved through better estimation of CPL disturbances, more precise compensation for destabilizing effects, and improved dynamic response to sudden CPL connection or disconnection. This makes it an effective solution for handling disturbances in the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid system caused by the connection or disconnection of CPLs.

Transients and steady state behaviours under sudden changes of both linear resistive load and CPL

To verify the performance of the proposed control method under simultaneous changes in linear resistive load and CPL, real-time simulation tests of the three control methods were conducted. In this scenario, the system was initially configured with a 450 Ω linear resistive load connected to the DC bus at a constant grid voltage magnitude of 211 V. At 0.2 s, a 450 W CPL was connected in parallel to the initial linear resistive load. Subsequently, the CPL power increased from 450 to 900 W at 0.3 s and to 1350 at 0.3 s, and at 0.4 s, the linear resistive load decreased from 450 Ω to 225 Ω. The HIL test results for this scenario are presented in Figs.13and14.

From these results, the analysis of both DC bus voltage and grid current responses demonstrates significant performance differences among the three control methods. As shown in Figs. 13 and 14c, the PI controller exhibits the poorest performance in terms of dynamic responses, disturbance rejection capabilities, and quality of DC bus voltage and grid-side currents, showing slow DC voltage convergence times with substantial voltage drops reaching 25 V, 45, and 85 V at 0.2 s, 0.3 s, and 0.4 s respectively, followed by severe oscillations after the change of the CPL power from 1350 to 1800 W at 0.4 s. This poor performance is further reflected in its grid-side current response, where the three-phase grid-side currents show significant distortions after 0.3 s, with noticeable oscillations in the dqγ-axes grid-side after 0.4 s. The traditional ESO-based ADRC method demonstrates improved performance over the PI controller, with acceptable both voltage convergence times and disturbance rejection, though it still shows noticeable voltage drops during transients and some oscillations after 0.4 s. Its grid current control also shows enhancement, maintaining acceptable sinusoidal waveforms and improved dqγ-axes grid-side current regulations with minimal oscillations than the PI controller. In contrast, the proposed FOADRC method showcases superior performance across all parameters under simultaneous changes in linear resistive load and CPL, maintaining excellent DC bus voltage regulation and stability with minimal voltage drops and the fastest convergence time from disturbances, while simultaneously exhibiting the most balanced and sinusoidal three-phase grid-side currents, the cleanest d-axis current step responses with minimal overshoot and oscillations, and excellent q0-axes current regulations with negligible oscillations (Fig. 14 c).

Grid-side currents under variations of both linear resistive load and CPL: (a) PI controllers, (b) traditional ESO-based ADRC method in46, (c) proposed FOADRC.

The excellent performance of the proposed FOADRC method in this scenario can be attributed to its advanced handling of the fundamentally different characteristics of these two types of loads resulting from the inherent characteristics of FOESO. The proposed FOADRC method effectively manages the contrasting behaviors between linear resistive loads, which exhibit linear voltage-current relationships (\({V}_{dc}=R{I}_{LR}\)), and CPLs which demonstrate nonlinear characteristics with inverse voltage-current relationships. The FOESO’s capability to estimate and compensate for both linear and nonlinear load behaviors simultaneously is crucial, as it handles both the direct proportional changes in current for linear load variations and the inverse relationship where current increases as voltage decreases for CPL changes. The FOESO technique structure provides better tracking of these mixed-nature disturbances, while effectively balancing the opposing characteristics of CPLs, which naturally introduce negative impedance characteristics that can destabilize the system, and linear loads, which provide damping effects. This balance is achieved through better estimation of the combined load effects, more precise compensation for destabilizing effects, and improved dynamic response to sudden load variations. Furthermore, the method demonstrates superior transient response through faster recognition of load type changes, more accurate prediction of required control actions, and better handling of the transition between different load dominance. This comprehensive handling of both load types’ unique characteristics enables the FOADRC technique to maintain stability and performance even during sudden mixed-load variations, making it the most effective solution for handling disturbance caused by mixed-load nature in the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid system.

Transients and steady state behaviours under sudden changes of CPL

Since a pure CPL represents the most challenging case for DC microgrid stability and performance, this test scenario was conducted to show the proposed FOADRC method’s effectiveness under variation of pure CPL compared with other control methods. The system was initially configured with a 450 W CPL connected to the DC bus at a constant grid voltage magnitude of 211 V, without any linear resistive load. The CPL power was then increased sequentially: From 450 to 900 W at 0.2 s, and from 900 to 1350 W at 0.3 s. The HIL real-time simulation results of the three control methods for this scenario are presented in Fig. 15. As illustrated in this figure, the DC bus voltage response reveals distinct performance characteristics among the three control methods under pure CPL variations. The proposed FOADRC method demonstrates superior performance with the fastest convergence times, minimal voltage drops, excellent disturbance rejection, and enhanced stability margin during both CPL power step changes. It maintains stable operation throughout the transitions with no oscillations, effectively regulating and stabilizing the DC bus voltage at 450 V. In contrast, the traditional ADRC method shows moderate performance with larger voltage drops and longer convergence times, though it maintains acceptable stability with only minor oscillations during steady-state periods. The PI controller exhibits the poorest performance overall, characterized by significant voltage drops (~ 50 V at 0.2 s), the slowest convergence time, and severe stability issues, particularly after the change of the pure CPL power from 450 to 900 W at 0.3 s where it develops large sustained oscillations. These high-frequency oscillations with large amplitude variations indicate marginal stability and poor disturbance rejection capability under increased pure CPL conditions. The performance degradation is especially pronounced during the second pure CPL power step change, highlighting the PI controller’s limitations in handling higher-power CPL loads. The PI controller faces an inherent trade-off between stability margin and dynamic performance. These results validate the superiority of the FOADRC method in terms of stability, dynamic response, disturbance rejection, and steady-state performance.

Capability and performance of the proposed control method against grid voltage fluctuations

Capability against grid voltage magnitude fluctuations

In this scenario, a HIL real-time simulation test was conducted to evaluate the proposed FOADRC approach’s performance in controlling a 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid under grid voltage variations. The test specifically examines the control of DC bus voltage and grid-side currents when subjected to a 20% voltage sag at t = 2 s, followed by voltage recovery to nominal levels at t = 3 s, as illustrated in Fig. 16. The assessment focuses on the controller’s effectiveness in rejecting disturbances in both control loops caused by these grid voltage variations. The test is conducted with the system feeding a constant power load of 450 W and a linear resistive load of 450 Ω. The simulation results for different control methods are shown in Fig 17a, Fig 17b and Fig 17c

HIL real time simulation results under grid voltage magnitude variations: (a) PI controllers, (b) traditional ESO-based ADRC method in46, (c) proposed FOADRC.

Figure 17a demonstrates that under grid voltage magnitude variations, the PI controller exhibits significant limitations, showing large DC bus voltage deviations of 12 V during voltage sag and recovery, with notable overshoots and undershoots of 4 V during these transients followed by notable convergence time in both transients and larger ripple during steady-state operation. The three-phase grid currents show increased ripple distortion during steady-state, while the d-axis current exhibits considerable overshoot during grid voltage sag and undershoot during recovery events with notable convergence time in both transients, indicating poor dynamic response and steady-state performance of the PI controller.

The traditional ESO-based ADRC method results in Fig. 17b show marked improvement over the PI controller, featuring reduced DC bus voltage deviations during disturbances and faster convergence times. It maintains acceptable sinusoidal waveforms in the three-phase grid-side currents during transitions with less distortion during steady-state, improved d-axis current tracking with reduced overshoots and acceptable reference tracking in the q0-axes currents.

In contrast, as shown in Fig. 17c, the proposed FOADRC method demonstrates superior performance across all metrics, exhibiting minimal DC bus voltage deviation during both voltage sag and recovery, with no overshoot or undershoot, and the fastest convergence times among all control methods. It maintains nearly perfect sinusoidal waveforms in the three-phase grid-side currents during both transitions and steady-state operation, demonstrates precise d-axis grid-side current tracking with no overshoot or undershoot and with fastest convergence times, and shows stable q0-axes current tracking throughout the operation.

Capability against grid frequency fluctuations

As grid voltage frequency fluctuations significantly impact the quality of grid-side current, loading deteriorates the steady-state DC bus voltage quality. This test scenario examines the capability of the proposed FOADRC method against grid frequency fluctuations. Simulation tests were performed when the grid voltage frequency was set at 49.5 and 50.5 Hz, and the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid system was configured with a 400 Ω linear resistive load. The spectrum harmonics of grid-side currents under the three control methods at these frequencies are shown in Figs. 18 and 19, respectively. Figure 20 presents a comparison of grid-side currents THD using the three control methods at different frequencies. The results reveal that all three methods exhibit relatively low sensitivity to grid voltage frequency fluctuations. Using the PI controller, the maximum THD variation under grid voltage frequency fluctuations (± 0.5 Hz) was 0.33%, with consistently high THD levels. When implementing the ESO-based ADRC method, the maximum THD variation increased slightly to 0.38% at 49.5 Hz. In contrast, the proposed FOADRC method demonstrated the most impressive performance, with a maximum THD variation of only 0.23%. This approach outperformed both the PI and ESO-based ADRC methods in terms of grid-side current harmonic eliminations under grid voltage frequency fluctuations.

Spectrum harmonic of first phase grid side current when the grid voltage frequency is set to 49.5 Hz: (a) PI controllers, (b) Traditional ESO-based ADRC method in46, (c) proposed FOADRC.

Spectrum harmonic of first phase grid side current when the grid voltage frequency is set to 50.5 Hz: (a) PI controllers, (b) Traditional ESO-based ADRC method in46, (c) proposed FOADRC.

Robustness to system parameter uncertainties

Finally, to verify the robustness of the proposed FOADRC method adopted in both the OVCL and IGSCCL for controlling a 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid under parameter uncertainties, comparative simulations were conducted with ± 50% variations in both grid-side inductance and 3LNPC-4LR output capacitance. The analysis focused on two key aspects: (1) the impact of output capacitance variations on DC bus voltage stability, evaluated through the magnitude of DC bus voltage drops caused by the change of linear resistive load from 450 to 225 Ω under different capacitance values, and (2) the effect of grid-side inductance variations on current quality, assessed through THD values of grid-side currents under different grid-side inductance values. The tests were performed with the 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid connected to a 400 Ω linear resistive load at a constant grid voltage magnitude of 211 V. The comparative results are presented in the figures, showing the magnitude of DC bus voltage drops under different capacitance values (550, 1100, and 1650 μF) and the grid-side current THD values comparison across varying grid-side inductance values (3, 6, and 9 mH) for the three control methods.

The results clearly show that the three methods respond differently to parameter variations. When using the PI controller, the DC bus voltage drop magnitude ranges from 8 to 18 V across different capacitance values, as shown in Fig. 21, while the grid-side current THD varies from 3.01% to 4.75% across different inductance values, as shown in Fin. 22. When adopting the traditional ESO-based ADRC method, both the DC bus voltage drop magnitude and grid-side current THD show improvement compared to the PI controller, with voltage drops ranging from 4 to 8 V and THD values ranging from 1.51% to 2.84%, with maximum DC bus voltage droop magnitude variation reaches 3 V at 550 μF (Fig. 21), and maximum grid-side current THD variation reaches 0.9% at 3% (Fig. 22). For the proposed FOADRC method, the performance is notably superior, with DC bus voltage drops ranging from 1.2 V to 2.7 V and grid-side current THD varying from 0.71% to 0.92%, with maximum DC bus voltage droop magnitude variation of only 0.8 V (Fig. 21), and maximum grid-side current THD variation of 0.13% (Fig. 22), thus demonstrating that the proposed method outperforms both PI controller and ESO-based ADRC method in terms of DC bus voltage stability and grid-side current quality under 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid system parameter variations. These results demonstrate that the proposed FOADRC method has high robustness against system parameter variations, maintaining satisfactory DC bus voltage stability and grid-side current quality under system parameter variations.

Table 4 presents a comprehensive comparison of the proposed FOADRC approach with conventional PI and standard ESO-ADRC control methods. This evaluation is conducted under identical system and control conditions, including input filter properties, DC bus voltage reference, DC load, capacitor size, and switching frequency, to ensure a fair assessment. The results highlight the advantages of the FOADRC technique, demonstrating its superior ability to reject disturbances, quicker dynamic response, notably shorter settling time, enhanced steady-state accuracy, improved grid-side current quality, lower noise levels, greater resilience to system uncertainties, and higher overall efficiency and reliability in 3LNPC-4LR-based DC microgrid applications.

To assess computational complexity, the total number of mathematical operations such as multiplications, additions, trigonometric functions, integrations, and differentiations, required to generate the control output from given inputs is considered, serving as a metric for computational burden25. Although the FOADRC strategy involves a slightly higher computational load compared to traditional controllers, it remains well within the processing capabilities of commonly used microcontrollers in power electronics. Moreover, with the advancement of embedded processing units like the ARM Cortex-M7 and TI C2000 series including TMS320F28377D and TMS320F28379D, real-time implementation of fractional-order control is achievable using efficient approximation methods such as the Grünwald–Letnikov scheme or Oustaloup’s recursive filter with reduced-order realizations.

Conclusions