Abstract

Lycoris aurea Herb is a plant renowned for its striking appearance and medicinal properties, particularly the production of alkaloids such as lycorine and galanthamine, which have therapeutic potential in treating diseases. Understanding the interaction between L. aurea and its rhizosphere microbiome is crucial, as the microbiome influences plant health, nutrient availability, and metabolite biosynthesis. This study investigated the interplay between rhizosphere microbiome and alkaloid levels in L. aurea using genetically identical plant samples collected from two ecologically distinct regions. The findings revealed that higher levels of lycorine and galanthamine correlated with specific soil physicochemical properties such as higher acid phosphatase activity and higher sodium and manganese levels. Additionally, quantitative Accu16STM and AccuITSTM sequencing demonstrated distinct bacterial and fungal diversities in the high alkaloids-producing group compared with the low alkaloids-producing group. Our study found that the abundance of four dominant bacterial phyla Acidobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, and Planctomycetota was higher in the low-alkaloid content group, whereas the dominant fungal phylum Ascomycota was more abundant in the high-alkaloid content group. Linear discriminant analysis revealed distinct variations in bacterial and fungal taxa, with the high-alkaloid content group containing ten bacterial indicators, such as Kitasatospora and Acidimicrobiaceae, and ten fungal taxa, including Boletales, Vandijckomycella and Sclerodermataceae. Functional annotations of microbial taxa revealed differences in metabolic functions such as chitinolysis and nitrate reduction in the high alkaloid groups, respectively. Moreover, Spearman correlation analysis underscored the relationships between microbial diversity and soil characteristics, particularly emphasizing the role of soil pH in influencing microbial populations. In conclusion, this research provides valuable insights into the environmental and rhizosphere microbial dynamics of L. aurea, offering implications for alkaloid biosynthesis and pharmacology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genus Lycoris, belonging to the subphylum Angiosperms and the class Monocotyledons, is a perennial, bulbous, and inflorescence-type herbaceous plant1. L. aurea, also known as "Golden Spider Lily," is a representative autumn-leafing, perennial bulbous plant within the genus Lycoris2. It prefers light, tolerates partial shade, is somewhat cold-resistant, and does not have strict soil requirements, making it a highly ornamental species among perennial bulbous flowers1,3. It is predominantly found in open grasslands and forest edges, which offer the dual advantages of soil drainage and sunlight exposure4,5. These ecological niches are crucial as they facilitate the full expression of the plant’s growth and reproductive capabilities2,5. However, the reproduction rate of L. aurea is quite low, and its offsets (bulbs) rarely meet the flowering and medicinal standards within a short period4. Most varieties produce only one to two bulbs per year, and it takes about four years for a bulb to mature and flower2. Additionally, habitat compression and fragmentation have led to the inability of its population to expand1,4. Therefore, studying the wild growth conditions and environment of L. aurea is of great significance.

Lycoris aurea thrives in specific ecological niches, its medicinal properties, particularly the production of bioactive alkaloids, make it an important plant both ecologically and pharmacologically. L. aurea contains alkaloids in its bulbs or stems, including galanthamine, lycorine, lycoramine, haemanthamine, narciclasine, and crinine, all of which have various pharmacological activities4,6,7. These alkaloids exhibit a broad spectrum of therapeutic activities, including immunostimulatory, antimalarial, antitumor, and antiviral properties8,9. Lycorine is particularly noted for its efficacy in inhibiting virus replication and inducing apoptosis in cancer cells, offering potential therapeutic benefits against leukemia by halting cell cycle progression10,11. Its antimalarial action is also significant, as it has shown effectiveness against Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of severe malaria12,13. On the other hand, galanthamine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, is utilized in mainstream medicine, predominantly for the management of Alzheimer’s disease14,15. Enhancing acetylcholine levels in the brain improves cognitive functions and offers symptomatic relief in Alzheimer’s, including managing some neuropsychiatric symptoms16. Current research suggests that the biosynthetic pathway of galanthamine in plants mainly involves multiple steps4. First, tyramine and 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde synthesize norbelladine. Then, under the catalysis of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), norbelladine undergoes a methylation reaction at the oxygen position of the hydroxy group on the catechol ring to produce 4-O-methylnorbelladine. This 4-O-methylnorbelladine is then converted into galanthamine through enzymatic reactions. Additionally, 4-O-methylnorbelladine is a common precursor of galanthamine, crinine, lycorine, and other Amaryllidaceae alkaloids7. As research continues, the underlying biosynthetic mechanisms of L. aurea relatives are progressively being uncovered, but there is still only few studies focusing on the interaction between L. aureus and soil properties and microorganisms. This research gap presents an opportunity to explore how soil properties and microbial communities may modulate alkaloid production in L. aurea, potentially enhancing the yield of bioactive compounds like lycorine and galanthamine.

The rhizosphere microbiome of L. aurea, consisting of a complex community of bacteria, fungi, and protozoa, plays a pivotal role in the plant’s health and growth. These microorganisms engage in symbiotic relationships with the plant, providing essential services such as nutrient absorption, enhancement of plant growth, and protection against pathogens17,18. This symbiosis is critical not only for the plant’s survival and health but also for its ability to produce bioactive compounds with significant medicinal properties. Bacteria in the rhizosphere soil microbiome, for example, can fix nitrogen from the atmosphere, converting it into a form that the plant can readily use, which is crucial for the plant’s growth in the soil where nitrogen might be scarce19,20. Fungi, particularly mycorrhizal fungi, extend their networks into the soil and increase the surface area for water and nutrient absorption21. The interactions between the plant roots and their microbial partners can enhance the production of specific alkaloids, such as lycorine and galanthamine22,23. These microbial interactions might alter the biosynthetic pathways of the plant, either by direct genetic exchange or through signaling compounds that induce specific biosynthetic activities in the plant cells24. Studies have indicated that manipulating these microbial populations could increase the concentrations and diversity of these bioactive compounds25. For example, certain strains of root-associated rhizosphere bacteria have been found to enhance alkaloid production when they colonize the plant roots23, suggesting a potential strategy for biotechnological applications to increase the yield and consistency of these compounds for pharmaceutical use.

Absolute quantitative 16S and ITS sequencing combines next-generation sequencing and quantitative PCR to accurately measure the exact abundance of bacterial and fungal species in a sample. This approach provides precise quantitative data, enabling researchers to determine the absolute number of microbial cells or genetic material copies per unit of sample, which is crucial for understanding microbial community dynamics and interactions. In light of the pivotal role that the microbiome plays in enhancing plant growth, health, and the synthesis of bioactive compounds, it becomes imperative to delve deeper into the symbiotic relationship between soil microorganisms and L. aurea. The hypothesis driving this investigation is that by understanding these rhizosphere interactions using Accu16S™ and AccuITS™ sequencing methods, we can optimize the growth and environmental properties of L. aurea. This exploration not only promises to enhance the agricultural productivity and ecological resilience of this plant but also aims to maximize its pharmacological potential.

Materials and methods

Site description

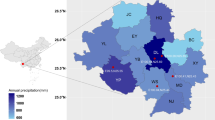

We conducted a study on the distribution of the golden spider lily across 16 cities in nine key provinces in China. Soils For a detailed comparative analysis, we selected Quannan County in Jiangxi Province (114° 35′, 24° 47′, Group H), known for its high alkaloid content, and Zhongfang County in Huaihua City, Hunan Province (110° 10′, 27° 49′, Group L), which is noted for its low alkaloid content. Quannan County in Jiangxi Province has a mid-subtropical humid monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature of 18.6 °C, an average annual rainfall of 1695 mm, and a frost-free period of 287 days (https://www.quannan.gov.cn). The vegetation throughout Quannan County features typical mid-subtropical evergreen broadleaf forests, with the mountains primarily composed of broadleaf forests dominated by Castanopsis and Altingia. Zhongfang County in Huaihua City, Hunan Province, lies in a subtropical monsoon climate zone, characterized by mild summers, moderately cold winters, distinct seasons, and abundant rainfall. The highest annual temperature is 37.1 °C, the lowest is − 1.9 °C, and the annual rainfall is 1563 mm (https://www.zhongfang.gov.cn). The local L. aurea community is covered by deciduous-evergreen broadleaf mixed forests, primarily composed of Fagaceae and Lauraceae. All plant and soil samples were collected during the peak growing season in mid-September 2023, ensuring consistency across sites.

Soil sampling

Rhizosphere soil samples from the two selected sites (H and L, three biological replicates, each with five soil samples mixed together) were gathered using soil augers and trowels after first clearing the surface of litter and fallen branches. To collect rhizosphere soil, we carefully excavated the soil surrounding the roots of the target plant, aiming to sample soil from a depth of approximately 10–15 cm around the root zone24. The collected soil (randomized across replicates) was placed in labeled collection bags, with care taken to avoid cross-contamination by keeping soil from different plants separate. After collection, the soil was sterilized, placed in an ice box, and transported to the lab immediately for analysis. Before subsequent analysis, soils were sieved using a 2 mm mesh to remove large particles, such as stones and debris. A portion of these samples was weighed and dried in an oven at 105 °C to determine dry weight, while another portion was stored in self-sealing bags in a – 80 °C freezer for further analysis.

HPLC analysis

We utilized high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to quantify the concentrations of lycorine and galanthamine following our previous methods with minor modifications2,24. Specifically, plant bulb samples collected from 16 cities (three replicates per city, each comprising four bulbs) were processed. Each sample, weighing 1 g of finely ground material, was mixed with 80 mL of 70% ethanol and homogenized thoroughly to ensure consistent extraction. Subsequently, the homogenized sample was added with 25 mL of distilled water and sonicated for 30 s using a VCX 500 Sonicator (Sonics & Materials, Inc, CT, US). The solution was incubated in a water bath at 30 °C for 30 min and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was adjusted to pH 10 using 0.5 M sodium hydroxide and treated with 10 mL of chloroform to eliminate any pigments and impurities. The chloroform layers were discarded, and the remaining aqueous layer was further extracted with 5 mL of n-butanol. The n-butanol extracts were pooled, filtered through a 0.45 μm filter, and subsequently injected into the HPLC system (Agilent 1100 HPLC System, Agilent Technologies, CA, US) for analysis. The HPLC analysis was conducted using a 250 × 4.6 mm Luna 5 μm C18(2) 100A column from Phenomenex, USA, with a detection wavelength of 232 nm and a column temperature set at 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of a 0.7% (φ) triethylamine aqueous solution mixed with ethanol and methanol at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. A sample volume of 10 μL was injected, and detection began 4 min after the start of the run.

Soil physical and chemical properties and plant enzymatic activities

The rhizosphere soil (three replicates) of L. aurea was used to measure 17 physiochemical properties, including water content (WC), pH, total nitrogen (TN), organic matter (OM), total phosphorus (TP), total potassium (TK), total sulfur (TS), available nitrogen (AN), selenium (Se), silicon (Si), sodium (Na), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), boron (B), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and manganese (Mn). The soil processing methods and detecting procedures were performed as described previously26. Briefly, fresh soil sample was accurately weighed and baked for 12 h in an oven preheated to 105 °C. Subsequently, the treated soil sample was moved into a dryer to cool to room temperature (30 min) and weighed immediately. The formula for soil WC was the same as that for the previous method26. For pH detection, 10 g soil sample was passed through a 1 mm sieve and then added with 25 mL distilled water. The above solution was allowed to stand for 30 min, and the suspension was measured for pH with a PH meter (PHS-2F). Soil nutrients, including TN, TP, TK, TS, TS, and OM were measured using the same methods as described in our previous work24,27. Trace elements, including Se, Si, Na, Ca, Mg, B, Zn, Cu, and Mn, were measured directly using a Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometer (ICPE-9000, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) following nitric acid digestion26. The measurement of soil enzyme activities, including polyphenol oxidase, peroxidase, sucrase, urease, acid phosphatase, catalase, alkaline phosphatase, neutral phosphatase, and protease, were measured following the protocols of Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis written by Bao28.

We analyzed three enzymatic activities, including tyrosine decarboxylase, caffeic acid-O-methyltransferase, and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, in the bulbs of L. aurea collected from two ecologically distinct populations to investigate how environmental and microbial differences, rather than genetic variation, influence the activity of key alkaloid-synthesizing enzymes. These enzymes were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits following the manufacturer’s protocol (ELISA, purchased from Shanghai Jianglai Biological Co. LTD, Shanghai, China).

DNA extraction and Accu16S™ and AccuITS™ sequencing

Microbial DNA was extracted from each set of soil samples (0.5 g, triplicates) using the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. To verify the DNA’s purity and quality, the DNA underwent PCR amplification followed by a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Primers specific to soil bacteria and fungi were used, targeting the bacterial 16S rDNA 515F (GTGCCAGCMGCCGCG GTAA)/907R (CCGTCAATTCCTTTGAGTTT) and amplifying fungal ITS sequences with primers ITS5-1737F (GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG)/ITS22043R (GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC)21,29. For PCR amplification, 10 ng/μL of sample DNA and spike-in internal reference DNA were utilized as templates in a PCR system (94 °C (1 min), 35 cycles of 94 °C (30 s), 52 °C (30 s), 68 °C (30 s), and 6 °C (10 min)). NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to verify the quality of the amplified fragments. PCR products were pooled in equal density ratios and purified with GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, US). The purified PCR amplicon products were sequenced on the Illumina 2 × 250 bp paired-end sequencing platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, United States) at the TinyGene Bio-Tech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Sequence processing and data analysis

Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) serve as artificially designated taxonomic units in phylogenetic and population genetic studies and are utilized in further analyses. For the analysis of bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences, the Greengenes database (https://greengenes.secondgenome.com/) was utilized, while fungal ITS sequences were analyzed using the UNITE database (https://unite.ut.ee/). Alpha diversity indexes, including the Chao1 index and Shannon index, were employed to evaluate species abundance and diversity of bacterial communities. The alpha diversity indexes were calculated using QIIME2 (version 2023.9). Differences in alpha diversity were graphically represented, employing Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons following the Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s post hoc test to ascertain the statistical significance of these differences. A distance matrix (Bray–Curtis Dissimilarity) for differential ASV tables was computed using QIIME2, followed by Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) analysis. The significance of differences among groups was tested using the Anosim (Analysis of Similarities) algorithm. Distance matrices were analyzed and visualized using R packages “Vegan” and “ggplot2”. Co-occurrence network analysis for bacterial and fungal communities was performed, applying multiple test corrections with the Benjamini–Hochberg method, setting a correlation coefficient threshold above 0.8 and an adjusted p-value below 0.01. This network was constructed using the “igraph” and “Hmisc” packages and interpreted using network topology metrics, including modularity and eigenvector centrality. The visualization of the co-occurrence network was performed using Gephi software (https://gephi.org/) with the Fruchterman Reingold layout. Functional predictions for 16S rRNA and ITS sequences were performed using FAPROTAX (v.1.2.11, https://pages.uoregon.edu/slouca/LoucaLab/archive/FAPROTAX) and FUNGuild (v.Guilds_v1.1.py, http://www.funguild.org/), respectively. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was performed to determine the significant difference of soil microbial composition in pairwise comparisons (LDA > 2.5, p < 0.05) using the R package “lefser”30. Spearman rank correlation analysis was employed to explore associations between microbial communities and soil characteristics. Furthermore, we utilized structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate the interactions among soil and plant properties, microbial attributes (including abundance, diversity, and network complexity), and soil alkaloid biosynthesis at two different sites. To assess the model’s fit, we considered several parameters: the chi-square (χ2) test with a p-value greater than 0.05, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) between 0 and 0.05, and a goodness-of-fit index (GFI) higher than 0.90. This analysis was conducted using Amos version 25.0. Significance levels in the study were denoted as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Graphics were processed using Adobe Illustrator CC.

Results

Analysis of alkaloid content in L. aurea across 16 regions in China

We explored the distribution of the golden lily community across 16 cities in nine provinces in China. The highest alkaloid content was identified in Quannan County in Jiangxi Province, whereas the lowest alkaloid content was found in Zhongfang County in Huaihua City, Hunan Province. In the Jiangxi group (H group), the concentrations of lycorine and galanthamine were 1901.21 µg/g and 1008.87 µg/g, respectively. In contrast, in the Hunan group (L group), the concentrations were 286.43 µg/g and 154.10 µg/g respectively (Table 1).

Soil physicochemical properties and enzymatic activity in L. aurea communities from two distinct locations

To study the differences in the physicochemical properties of rhizosphere soil in different communities of L. aurea between two representative locations, we collected soil samples from both sites and measured various soil physicochemical parameters (Fig. 1, Figures s1–s2). The results indicated that the soil physicochemical properties, particularly soil pH, were significantly higher in the L group (7.42 ± 0.45) compared to the H group (6.04 ± 0.13). Additionally, acid phosphatase, sodium, and manganese were higher in the H group than in the L group (p < 0.05), while urease, alkaline phosphatase, and protease were significantly lower in the H group (p < 0.05). Other physicochemical indicators, such as soil OM, TP, TK, and AN, did not show significant differences between the two groups.

We analyzed the levels of key enzymes involved in secondary metabolism and alkaloid synthesis in the bulbs of L. aurea, including tyrosine decarboxylase, caffeic acid O-methyltransferase, and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase. Our findings showed that the activities of all three enzymes remained unchanged across the two representative plant communities (Fig. 2). Statistical analysis of enzyme activity levels revealed no significant differences between the two communities, indicating that enzyme levels were stable under the conditions tested.

Analysis of bacterial and fungal community structures

The rarefaction curves for bacterial and fungal communities in various rhizosphere soil samples leveled off (Fig. S3), demonstrating that the sequencing data accurately captured the compositions of these communities. The analysis identified these communities as belonging to 41 phyla and 338 genera. At the phylum level, Acidobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, and Planctomycetota were the predominant bacterial phyla across different forest soils, collectively comprising about 75% of the total abundance (Fig. 3A). The abundance of these four bacterial phyla was lower in group H compared to group L. At the genus level, Gaiella, Nitrospira, and RB41 were the leading bacterial genera in the soil, with group L exhibiting a higher absolute abundance of these genera (Fig. 3B). For fungi, the annotated fungal ASVs encompassed 17 phyla and 671 genera. The main fungal phyla were Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Mortierellomycota, and Rozellomycota, which together accounted for approximately 90% of the total fungal abundance (Fig. 3C). The Ascomycota phylum was more abundant in group H, while Basidiomycota was notably more prevalent in group L. At the genus level, the most abundant fungal genera were Entoloma, Penicillium, Fusarium, and Archaeorhizomyces (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, Entoloma was more abundant in group L, whereas Penicillium had a higher presence in group H.

Analysis of bacterial and fungal community diversity

Interestingly, no significant differences were observed in the α-diversity indices across soil samples from different groups. The indices for both bacterial and fungal communities (observed species, Chao1, and Shannon) indicated similar levels in groups L and H, with no statistical significance (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4A,B ). However, NMDS analysis revealed that soil samples from different groups formed distinct clusters within the ordination space (Fig. 5A,B). Analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) showed that the effects of the region variations on bacterial beta diversity (R = 0.91, p < 0.01) were higher than its effects on fungal beta diversity (R = 0.84, p < 0.01).

Co-occurrence network and microbial biomarkers analysis

This research used network analysis to explore the co-occurrence patterns among bacterial and fungal communities in the rhizosphere soil. The bacterial network comprised 301 nodes and 1938 edges, with a modularity index of 0.65 and a network density of 0.098 (Fig. S4). Notably, the four most central taxa, Anaeromyxobacter, Acidothermus, Candidatus_Solibacter, and Gemmatimonas, were identified as crucial hub biomarkers due to their high eigenvector centrality scores. For the fungal community, the network included 276 crucial nodes featuring a modularity index of 0.65 and a network density of 0.045 (Fig. S5). The prominent fungi Penicillium, Mortierella, Entoloma, and Fusarium stood out as hub biomarkers, recognized for their high eigenvector centrality scores. LDA analysis further revealed distinct variations in bacterial and fungal taxa between the two groups. Specifically, the H group contained ten bacterial taxa, such as Kitasatospora, Acidimicrobiaceae, and Hyphomicrobiaceae (Fig. 6A), and ten fungal taxa, including Boletales, Vandijckomycella and Sclerodermataceae (Fig. 6B). Conversely, the L group had nine bacterial taxa, including AKAU4049, JdFR-76, and Planctomycetes (Fig. 5A), along with ten fungal taxa, such as Fusarium variasi, Lecythophora, and GS06 (Fig. 5B). Additionally, functional annotation was conducted to explore potential functional differences at the various sites (Fig. 6C). The findings pointed to significant changes in primary functional annotations, particularly in processes like sulfate respiration and cellulolysis, which showed higher expression levels in the L group, chitinolysis and nitrate reduction, which showed notably high expression levels in the H group. For fungal functions, improvements in dung saprotroph were noted in the L group, whereas activities related to ectomycorrhizal-fungal parasite-plant pathogen were elevated in the H group (Fig. 6D, Fig. S6).

Variations in bacterial and fungal community compositions across different groups. (A,B) Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) highlighting significant differences in bacterial and fungal taxa between groups. (C) Functional analysis of the bacterial community, using the FAPROTAX database to annotate bacterial activities. (D) Identification of four fungal genera with notable distinctions between groups, analyzed using the FUNGuild database. DS dung saprotroph, ECM/FP/PP ectomycorrhizal-fungal parasite-plant pathogen. (*/**) denote significant differences (p < 0.05/0.01) between the Jiangxi (H) and Hunan (L) groups.

Relationships of microbial communities with soil properties

Spearman correlation analysis assessed the relationships between rhizosphere soil and plant properties and microbial alpha and beta diversities (Table 2). The study revealed distinct relationships between plant and soil characteristics and microbial diversity. Among the soil properties, AN and sodium were the most significant factors influencing bacterial and fungal alpha and beta diversities. Soil pH, selenium, polyphenol oxidase, and alkaline phosphatase positively correlated with bacterial beta diversity. Regarding fungi, boron was negatively correlated with the Chao1 index, while soil pH, selenium, alkaline phosphatase, and neutral phosphatase demonstrated positive correlations with fungal beta diversity.

Subsequently, we performed SEM analysis to illustrate that soil and plant properties and bacterial and fungal characteristics were the primary factors influencing alkaloid content at the two sites, particularly for the H group (Fig. 7). Bacterial and fungal diversities directly and positively affected soil multifunctionality, with standardized path coefficients of 0.66 and 0.69 (p < 0.01), respectively. Interestingly, plant activities had minor impacts on microbial attributes, showing a significant direct negative impact on bacterial abundance, with a coefficient of 0.65 (p < 0.01).

Structural equation model assessing the impacts of soil properties, plant activities, and bacterial and fungal communities on alkaloid biosynthesis at two sites (H and L). The width of the arrows signifies the magnitude of significant standardized path coefficients (p < 0.05), with red arrows indicating positive correlations and blue arrows indicating negative correlations. Gray lines represent pathways with non-significant coefficients. Significance levels are indicated as follows: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Discussion

The investigation into the ecological and microbial dynamics of L. aurea provides essential insights into its adaptive strategies and medicinal potential, a pursuit that holds implications for environmental research and pharmacological innovation. This study, situated in contrasting geographical locales with varied alkaloid profiles, seeks to address a significant gap in understanding how ecological factors influence secondary metabolite synthesis in plants. The regional variation in alkaloid content across 16 L. aurea populations highlights the considerable diversity in lycorine and galanthamine production at a broader geographic scale. While our detailed multi-omics investigation focused on two representative populations, the underlying trends observed in soil properties, microbial communities, and gene expression may have broader applicability. For instance, populations from Baise (Guangxi) and Wulong (Chongqing) also exhibited elevated lycorine levels, suggesting that similar environmental or edaphic conditions might be influencing alkaloid biosynthesis in those areas. Conversely, regions like Huzhou (Zhejiang) and Guilin (Guangxi), which reported low alkaloid concentrations, may share inhibitory soil or climatic characteristics similar to our L group. Therefore, the results of this study potentially provide a framework for understanding the biochemical and ecological determinants of alkaloid accumulation in L. aurea across its distribution range. However, further site-specific investigations are necessary to confirm whether the mechanisms identified in our focal regions (e.g., elevated acid phosphatase and sodium levels, upregulation of N4OMT) are consistent across other populations.

The comparative analysis of L. aurea across two distinct regions in China, notably between Quannan County in Jiangxi Province and Zhongfang County in Huaihua City, Hunan Province, has yielded critical insights into the environmental influence on alkaloid biosynthesis in this species. The marked disparity in the alkaloid content, with Jiangxi (H group) presenting significantly higher concentrations of lycorine and galanthamine compared to Hunan (L group), underscores the impact of regional environmental conditions on the metabolic profiles of plants. This difference is particularly significant because it suggests that soil properties, beyond just genetics, play a pivotal role in alkaloid production. This difference is particularly striking given that both locations are within the native range of L. aurea, suggesting that rhizosphere soil properties might play a significant role in influencing these metabolic variations5,31. The higher soil pH in the L group correlated with lower alkaloid concentrations, suggesting a possible inhibitory effect of less acidic soil on the biosynthesis of certain alkaloids. This is complemented by higher levels of acid phosphatase, sodium, and manganese in the H group, which are known to influence plant metabolic processes, including alkaloid synthesis32. The enhanced levels of acid phosphatase, sodium, and manganese in the H group provide critical insights into the factors that may boost alkaloid synthesis in L. aurea. Acid phosphatase aids in phosphate mobilization, which is crucial for energy transfer and metabolic processes essential for alkaloid biosynthesis33. Sodium, although not a primary nutrient for most plants, can influence osmotic balance and nutrient uptake, potentially enhancing the transport of precursors needed for alkaloid synthesis34. These soil components in Jiangxi contribute to a more conducive environment for synthesizing key alkaloids like lycorine and galanthamine than the soils of Hunan. The variations in these soil parameters could alter the plant’s physiological responses, affecting its secondary metabolite production. Additionally, weather and geographic variation likely contribute to the observed differences in secondary metabolite production. For example, Quannan County (Group H) has a more stable and humid monsoon climate with higher annual rainfall and milder seasonal shifts compared to Zhongfang County (Group L), which may create a more favorable microenvironment for sustained metabolic activity and alkaloid accumulation. However, it is essential to acknowledge that the differences in alkaloid content observed between the two regions may not solely be attributed to environmental factors. To ensure that the L. aurea populations from both regions are genetically the same species, we have conducted genetic analyses, confirming their species identity through DNA sequence alignment24. Nevertheless, the possibility that the genetic differences between the two L. aurea populations studied could contribute to these variations cannot be overlooked. Our recent study has shown that the genetic diversity inherent in these populations might play a significant role in determining their alkaloid biosynthetic capabilities35. Furthermore, it is also plausible that the distinct alkaloid profiles of these plant populations influence the composition of the microbial communities in the soil rather than the other way around21. Hence, this complex interplay between genetics, environmental factors (e.g., weather, light density, and artificial cultivation methods), and microbial interactions underscores the need for a more detailed understanding of how these variables collectively influence alkaloid biosynthesis in L. aurea.

Our study highlights distinct microbial dynamics across two geographical locations, with marked differences in the predominant bacterial and fungal phyla. At the phylum level, Acidobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, and Planctomycetota were identified as the predominant bacterial phyla. These phyla are known for their roles in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and soil structure maintenance, underlining their ecological importance27,36. Their collective dominance, forming about 75% of the total bacterial abundance, highlights a significant microbial foundation shared across diverse forest soils. However, it’s notable that these phyla were less abundant in Group H compared to Group L. This variation could be indicative of different soil conditions, such as pH levels, moisture content, and organic matter, which are known to influence microbial distributions24. At the genus level, the higher absolute abundances of Gaiella, Nitrospira, and RB41 in Group L suggest a microbial environment that may be more effective in processes such as nitrogen cycling (especially with Nitrospira, which is involved in nitrification)37,38. These differences at the microbial community level could have profound implications for nutrient availability and soil fertility, potentially affecting plant health and growth39. Fungal community analysis also demonstrated significant diversity, with the phyla Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Mortierellomycota, and Rozellomycota accounting for approximately 90% of the fungal abundance. The variation in the abundance of these phyla between groups—with Ascomycota being more prevalent in Group H and Basidiomycota in Group L—may reflect adaptations to local environmental conditions, as these fungi play critical roles in organic matter breakdown and nutrient cycling40,41. At the genus level among fungi, the disparity in abundance of genera such as Entoloma and Penicillium between the two groups underscores ecological or microenvironmental preferences. For instance, Entoloma being more prevalent in Group L might suggest conditions favorable for this genus, such as specific soil pH or moisture content, while Penicillium’s predominance in Group H might relate to the organic content or other soil characteristics favorable to this genus. Despite these compositional differences at more specific taxonomic levels, the α-diversity indices (observed species, Chao1, and Shannon) showed no significant differences between the groups, indicating that overall microbial diversity remains consistent across different environments. This suggests that while the types of microbial species vary, the overall complexity of the microbial communities is balanced.

The co-occurrence network analyses of bacteria and fungi in this study offer profound insights into the complex interactions within microbial communities and their potential impact on ecosystem functions. The centrality of bacteria such as Anaeromyxobacter, Acidothermus, Candidatus_Solibacter, and Gemmatimonas in the network analysis underscores their roles as keystone species. Anaeromyxobacter is known for its versatile metabolic capabilities, including iron reduction and participation in the nitrogen cycle, which can significantly affect soil chemistry and fertility42. Acidothermus contributes to cellulose degradation, a critical function in carbon cycling43, while Candidatus_Solibacter is renowned for its extensive metabolic repertoire that enables it to thrive under nutrient-limited conditions, thus promoting soil stability and plant growth44. Gemmatimonas, on the other hand, plays a role in phosphorus solubilization, an essential process that makes this nutrient more available to plants, thereby enhancing growth and survival45. Similarly, fungi such as Penicillium, Mortierella, Entoloma, and Fusarium serve pivotal roles in the fungal network. Penicillium is a genus widely recognized for its ability to break down organic matter and contribute to the decomposition process, while Mortierella is significant for nutrient cycling, particularly in nitrogen and phosphorus transformations46,47. These key microbial taxa, through their functional roles in nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon cycling, may influence plant metabolic pathways, potentially affecting alkaloid biosynthesis in L. aurea. For example, nitrogen cycling microbes such as Nitrospira may impact the availability of nitrogen precursors necessary for alkaloid production. The robust expression of functions such as cellulolysis, and nitrate reduction across both groups illustrates a dynamic capability for supporting key ecosystem services. Cellulolysis, the breakdown of cellulose, directly impacts carbon cycling, providing a critical link in converting organic matter into forms usable by plants39. Nitrate reduction not only impacts nitrogen availability, a limiting nutrient in many ecosystems, but also plays a significant role in mitigating nitrogen losses through denitrification, a process critical for maintaining ecosystem balance48,49. These alterations underscore the microbial community’s capacity to support biodiversity, promote soil health, and enhance agricultural productivity. Understanding these microbial interactions and functional capacities offers insights into managing soil ecosystems for sustainability and resilience against environmental changes.

The Spearman correlation analysis conducted in this study provides insightful connections between soil and plant properties and the diversity of microbial communities, shedding light on the complex interactions that sustain ecosystem functions. Group L, characterized by higher soil pH levels, exhibited unique physiological alterations that seemed to foster distinct microbial communities compared to Group H. Soil pH is a fundamental environmental factor that profoundly affects microbial life because it influences the solubility of minerals, availability of nutrients, and chemical forms of toxins, all of which can drastically affect microbial growth and function50,51. The positive correlation between soil pH and both bacterial and fungal beta diversity observed in this study suggests that higher pH levels may support a more diverse microbial community. This highlights the importance of pH management in agricultural practices, as optimal pH levels could enhance soil microbial diversity and improve plant health by creating a more favorable environment for beneficial microbes, which are essential for nutrient cycling and disease suppression. This correlation might be due to the reduced solubility of toxic metal ions at higher pH or the increased availability of certain nutrients that are more soluble under alkaline conditions, which can support a wider variety of microbial life52,53. For bacteria, the elevated pH levels in Group L could facilitate the growth of alkaliphilic or neutrophilic species that thrive in milder acidic to neutral or basic conditions, enhancing bacterial beta diversity. This is supported by the positive correlations (also present in the SEM model) with soil properties like selenium, polyphenol oxidase, and alkaline phosphatase, which are integral to microbial metabolic processes such as antioxidant protection, organic matter decomposition, and phosphorus cycling. Fungi are generally sensitive to changes in soil pH, with different groups adapted to specific pH ranges54. The positive correlation between higher soil pH and fungal beta diversity in Group L suggests that these conditions may favor fungi that decompose complex organic compounds, often abundant in neutral to alkaline soils. This is further supported by the positive correlation with enzymes like alkaline phosphatase and neutral phosphatase, which play roles in mineralizing organic phosphorus compounds into inorganic forms that plants can absorb.

This comprehensive study explored the ecological, biochemical, and microbial dynamics of L. aurea across different regions, significantly advancing our understanding of how environmental factors like soil pH and other physicochemical properties influence plant alkaloid content and microbial diversity. However, the study’s practical implications are somewhat limited by the confined geographical scope, as it only covers two regions, which may not fully capture the broader ecological variability where L. aurea is found. Future studies could benefit from a longitudinal design to capture temporal variations and employ experimental manipulations to better ascertain these relationships. Expanding the geographic scope and incorporating diverse environmental conditions would not only strengthen the generalizability of the findings but also provide more actionable insights for agricultural practices aimed at enhancing alkaloid production in L. aurea.

Conclusion

This study has provided a comprehensive analysis of the distribution, ecological interactions, and biochemical dynamics of L. aurea, uncovering significant insights into how environmental factors such as soil properties and microbial diversity influence the chemical profile of this medicinally valuable plant. By conducting detailed comparative analyses across different ecological settings, we elucidated the profound impact of rhizosphere soil pH, nutrient availability, and microbial community structures on the production of key alkaloids like lycorine and galanthamine, which have important therapeutic applications. The findings emphasize the necessity of considering ecological and microbial contexts in the conservation and agricultural practices involving L. aurea.

Data availability

The sequencing data were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with BioProject accession number PRJNA1100637. Other data used to support the findings are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Chang, Y.-C., Shii, C.-T. & Chung, M.-C. Variations in ribosomal RNA gene loci in spider lily (Lycoris spp.). J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 134(5), 567–573 (2009).

Quan, M. et al. Photosynthetic characteristics of Lycoris aurea and monthly dynamics of alkaloid contents in its bulbs. Afr. J. Biotech. 11(15), 3686–3691 (2012).

Salachna, P. & Piechocki, R. Comparison of nutrient content in bulbs of Japanese red spider lily (Lycoris radiata) and golden spider lily (Lycoris aurea), ornamental and medicinal plants. World News Nat. Sci. 26, 72–79 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. Analysis of bioactive Amaryllidaceae alkaloid profiles in Lycoris species by GC-MS. Nat. Prod. Commun. 9(8), 1934578X1400900806 (2014).

Quan, M. & Liang, J. The influences of four types of soil on the growth, physiological and biochemical characteristics of Lycoris aurea (L’Her.) Herb. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 43284 (2017).

Cahlíková, L., Breiterová, K. & Opletal, L. Chemistry and biological activity of alkaloids from the genus Lycoris (Amaryllidaceae). Molecules 25(20), 4797 (2020).

Tian, Y., Zhang, C. & Guo, M. Comparative analysis of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids from three Lycoris species. Molecules 20(12), 21854–21869 (2015).

Jahn, S. et al. Metabolic studies of the Amaryllidaceous alkaloids galantamine and lycorine based on electrochemical simulation in addition to in vivo and in vitro models. Anal. Chim. Acta 756, 60–72 (2012).

Ghane, S. G., Attar, U. A., Yadav, P. B. & Lekhak, M. M. Antioxidant, anti-diabetic, acetylcholinesterase inhibitory potential and estimation of alkaloids (lycorine and galanthamine) from Crinum species: An important source of anticancer and anti-Alzheimer drug. Ind. Crops Prod. 125, 168–177 (2018).

Cao, Z., Yang, P. & Zhou, Q. Multiple biological functions and pharmacological effects of lycorine. Sci. China Chem. 56, 1382–1391 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. Lycorine reduces mortality of human enterovirus 71-infected mice by inhibiting virus replication. Virol. J. 8, 1–9 (2011).

Cedrón, J. C., Gutiérrez, D., Flores, N., Ravelo, Á. G. & Estévez-Braun, A. Synthesis and antiplasmodial activity of lycorine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18(13), 4694–4701 (2010).

Nair, J. J. & van Staden, J. Antiplasmodial lycorane alkaloid principles of the plant family Amaryllidaceae. Planta Med. 85(08), 637–647 (2019).

Rainer, M. Galanthamine in Alzheimer’s disease: A new alternative to tacrine?. CNS Drugs 7(2), 89–97 (1997).

Heinrich, M. & Teoh, H. L. Galanthamine from snowdrop—The development of a modern drug against Alzheimer’s disease from local Caucasian knowledge. J. Ethnopharmacol. 92(2–3), 147–162 (2004).

Santos, G. S. et al. Use of galantamine in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and strategies to optimize its biosynthesis using the in vitro culture technique. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. PCTOC. 143, 13–29 (2020).

Chaparro, J. M., Sheflin, A. M., Manter, D. K. & Vivanco, J. M. Manipulating the soil microbiome to increase soil health and plant fertility. Biol. Fertil. Soils 48, 489–499 (2012).

Fierer, N. Embracing the unknown: disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15(10), 579–590 (2017).

Ryu, M.-H. et al. Control of nitrogen fixation in bacteria that associate with cereals. Nat. Microbiol. 5(2), 314–330 (2020).

Sepp, S.-K. et al. Global diversity and distribution of nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the soil. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1100235 (2023).

Jiao, S., Peng, Z., Qi, J., Gao, J. & Wei, G. Linking bacterial-fungal relationships to microbial diversity and soil nutrient cycling. Msystems. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.01052-01020 (2021).

Liu, Z., Zhou, J., Li, Y., Wen, J. & Wang, R. Bacterial endophytes from Lycoris radiata promote the accumulation of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. Microbiol. Res. 239, 126501 (2020).

Zhou, J. et al. Fungal endophytes promote the accumulation of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids in Lycoris radiata. Environ. Microbiol. 22(4), 1421–1434 (2020).

Zuo, Y. W. et al. Multi‐omics analysis reveals molecular responses of alkaloid content variations in Lycoris aurea across different locations. Plant Cell Environ. (2024).

Castronovo, L. M. et al. Medicinal plants and their bacterial microbiota: a review on antimicrobial compounds production for plant and human health. Pathogens 10(2), 106 (2021).

Shidan, B. Soil Agrochemical Analysis, vol. 42, 76–79 (China Agricultural Publishing House, 2000).

Zuo, Y. et al. Distinctive patterns of soil microbial community during forest ecosystem restoration in southwestern China. Land Degrad. Dev. 34(14), 4181–4194 (2023).

Shidan, B. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis (Chinese Agriculture Publishing House, 2000).

Jiao, S. et al. Soil microbiomes with distinct assemblies through vertical soil profiles drive the cycling of multiple nutrients in reforested ecosystems. Microbiome 6, 1–13 (2018).

Chen, L.-j, Tan, F.-h & Li, Z.-z. Contrasting responses of cuticular bacteria of Pardosa pseudoannulata under cadmium stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 255, 114832 (2023).

Jiang, X., Chen, H., Wei, X. & Cai, J. Proteomic analysis provides an insight into the molecular mechanism of development and flowering in Lycoris radiata. Acta Physiol. Plant. 43, 1–13 (2021).

Poutaraud, A. & Girardin, P. Influence of chemical characteristics of soil on mineral and alkaloid seed contents of Colchicum autumnale. Environ. Exp. Bot. 54(2), 101–108 (2005).

Han, D. et al. Effects of endophytic fungi on the secondary metabolites of Hordeum bogdanii under alkaline stress. AMB Express 12(1), 73 (2022).

Subbarao, G., Ito, O., Berry, W. & Wheeler, R. Sodium—a functional plant nutrient. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 22(5), 391–416 (2003).

Quan, M. et al. Reciprocal natural hybridization between Lycoris aurea and Lycoris radiata (Amaryllidaceae) identified by morphological, karyotypic and chloroplast genomic data. BMC Plant Biol. 24(1), 14 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Soil profile rather than reclamation time drives the mudflat soil microbial community in the wheat-maize rotation system of Nantong, China. J. Soils Sediments 21, 1672–1687 (2021).

Daims, H. et al. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 528(7583), 504–509 (2015).

Mehrani, M.-J., Sobotka, D., Kowal, P., Ciesielski, S. & Makinia, J. The occurrence and role of Nitrospira in nitrogen removal systems. Biores. Technol. 303, 122936 (2020).

Soares, F. L., Melo, I. S., Dias, A. C. F. & Andreote, F. D. Cellulolytic bacteria from soils in harsh environments. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 28, 2195–2203 (2012).

Colpaert, J. V. & van Tichelen, K. K. Decomposition, nitrogen and phosphorus mineralization from beech leaf litter colonized by ectomycorrhizal or litter-decomposing basidiomycetes. New Phytol. 134(1), 123–132 (1996).

Suberkropp, K. Microorganisms and organic matter decomposition. In River Ecology and Management: Lessons from the Pacific Coastal Ecoregion, 120–143 (1998).

Itoh, H., et al. Anaeromyxobacter oryzae sp. nov., Anaeromyxobacter diazotrophicus sp. nov. and Anaeromyxobacter paludicola sp. nov., isolated from paddy soils. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 72(10), 005546 (2022).

Hengge, N. N. et al. Characterization of the biomass degrading enzyme GuxA from acidothermus cellulolyticus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(11), 6070 (2022).

De Mandal, S., Chatterjee, R. & Kumar, N. S. Dominant bacterial phyla in caves and their predicted functional roles in C and N cycle. BMC Microbiol. 17, 1–9 (2017).

Li, X. et al. Biochar fertilization effects on soil bacterial community and soil phosphorus forms depends on the application rate. Sci. Total Environ. 843, 157022 (2022).

Sidrim, J. et al. Fungal microbiota dynamics as a postmortem investigation tool: focus on Aspergillus, Penicillium and Candida species. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108(5), 1751–1756 (2010).

Tamayo-Vélez, Á., Osorio, N. W. Soil fertility improvement by litter decomposition and inoculation with the fungus Mortierella sp. in avocado plantations of Colombia. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 49(2), 139–147 (2018).

Deng, D. et al. Denitrification dominates dissimilatory nitrate reduction across global natural ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 30(3), e17256 (2024).

Mahmud, K., Panday, D., Mergoum, A. & Missaoui, A. Nitrogen losses and potential mitigation strategies for a sustainable agroecosystem. Sustainability 13(4), 2400 (2021).

Neina, D. The role of soil pH in plant nutrition and soil remediation. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2019, 1–9 (2019).

Yan, F., Schubert, S. & Mengel, K. Soil pH changes during legume growth and application of plant material. Biol. Fertil. Soils 23, 236–242 (1996).

Dick, W. A., Cheng, L. & Wang, P. Soil acid and alkaline phosphatase activity as pH adjustment indicators. Soil Biol. Biochem. 32(13), 1915–1919 (2000).

Shen, C. et al. Soil pH dominates elevational diversity pattern for bacteria in high elevation alkaline soils on the Tibetan Plateau. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 95(2), fiz003 (2019).

Rousk, J. & Brookes, P. C. Bååth E: Contrasting soil pH effects on fungal and bacterial growth suggest functional redundancy in carbon mineralization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75(6), 1589–1596 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32070367; 31470403) and General Program of the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (2024NSCQ-MSX2167).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z., G.L. and M.Q. conceived and designed the study. L.Y., J.L. helped with the experiment design. Y.Z., G.L., and J.L. collected the samples. Y.Z., G.L. and L.Y. analyzed the data and prepared the figures and table. H.D., M.Q. helped with the improvement of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Gh., Li, J., Yan, LX. et al. Impact of rhizosphere quantitative microbiome and soil properties on alkaloid levels in Lycoris aurea herb. Sci Rep 15, 25806 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09631-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09631-6