Abstract

The development of a precise model for predicting pipeline corrosion rates is essential for ensuring the safe operation of pipelines. To address the issues of inadequate stability and prolonged execution time associated with traditional models, the KPCA algorithm is used here to reduce the dimensionality of corrosion rate data for subsea pipelines, and the primary factors that influence the corrosion rate are identified. Based on the data characteristics, four algorithms (BP, LSSVM, SVM, and RF) were compared. Ultimately, the LSSVM algorithm was selected as the final prediction model. Then the LSSVM prediction model is subsequently developed, and the NGO algorithm is utilized to optimize the weights and thresholds of the LSSVM model, thereby increasing the accuracy of the prediction model and effectively reducing prediction instability. A combined KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model is developed to predict the corrosion rates of subsea pipelines and is compared with three other models: KPCA-PSO-LSSVM, PSO-LSSVM, and NGO-LSSVM. The mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), root mean square error (RMSE) and determination coefficient (R2) of the integrated KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model are 1.791%, 0.06105 and 0.9922, respectively, these metrics are significantly lower than those of benchmark models, a finding consistently validated across multiple experimental datasets. This demonstrates the KPCA-NGO-LSSVM framework’s enhanced prediction accuracy and stability. The model demonstrates effective performance in predicting the corrosion rates of subsea pipelines and offers novel methodologies and concepts for future research in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Oil and natural gas occupy a significant position within China’s energy strategy, which is of paramount importance to the country’s national development. Pipeline transportation is one of the most prevalent modes of transportation for oil and gas and has evolved into the fifth largest transportation industry in China. However, when a pipeline is in operation, because of the environment and pipeline medium, pipeline corrosion occurs, which in turn leads to various accidents1. Corrosion is a significant factor contributing to pipeline failure, as evidenced by relevant statistical data. Increased pipeline operation time results in a gradual reduction in strength, ultimately leading to failure. Corrosion has been recognized as the principal cause of pipeline failure incidents. Consequently, the corrosion rate is commonly employed as an evaluation index for pipeline corrosion2,3. There are many factors affect the corrosion rates of pipelines, such as the pipeline medium components, temperature, flow rate, pH, and dissolved oxygen and CO2 contents. These factors interact with each other and are interrelated, forming an intricate corrosion system4. Consequently, the development of a multifactor, high-dimensional model for accurately predicting the corrosion rate of subsea pipelines will be a focal point of future research.

Advances in computer science have led researchers worldwide to conduct extensive studies on predicting pipeline corrosion rates through machine learning5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Jin et al. proposed buffer operator theory to develop an enhanced DGM(1,1) model for forecasting pipeline corrosion rates over time, which significantly outperforms the conventional DGM(1,1) model in terms of predictive accuracy16. Biezma et al. proposed a fuzzy logic method to predict and analyse the corrosion rates of pipelines, considering six influencing factors. This approach improves both the accuracy and stability of the predictions17. Zhang et al. employed a distinctive BP neural network model for predicting pipeline corrosion rates, obtaining results that align more closely with measured values and effectively illustrating the correlation between various factors and the corrosion rate18. Nagoor et al. employed an ANN model to predict the service life of a crude oil pipeline, achieving a prediction accuracy of 99.97%19. Bo et al. predicted the corrosion rates of pipelines via the PSO-MGM(1,1) model, and its prediction accuracy was 16% higher than that of the MGM(1,1) model20. Xiao et al. used the WOA-BP algorithm to predict the corrosion rates of subsea pipelines, and the average absolute percentage error of their predictions was 3.689%, which was much lower than that of the comparison model1. Jia et al. used kernel principal component analysis to determine the corrosion rates of subsea pipelines and related factors and established a KPCA-SVM model21. This method reduces the interference of low-correlation data, improves the prediction accuracy and reduces the prediction difficulty. Nagoor et al.employed a Bayesian regularization-based neural network framework to predict dry airway lifespan with high accuracy, even when handling datasets containing missing parameters22. Xiao et al. predicted the corrosion rates of subsea pipelines via a combined PSO-TSO-BPNN model with an average absolute percent error of 1.8441%4, which represents a significant improvement in both the accuracy and stability of the model. The modelling methods proposed by the above scholars all have unique advantages but are limited by the optimization algorithms and the neural network’s own limitations, which may make them unable to obtain accurate predictions of pipeline corrosion rates for multifactorial and high-dimensional problems.

This paper presents a hybrid model, KPCA-NGO-LSSVM, for predicting the corrosion rates of subsea pipelines, utilizing kernel principal component analysis (KPCA) and Northern Goshawk optimization (NGO) to increase the performance of the least squares support vector machine (LSSVM). Kernel principal component analysis (KPCA) is employed to downscale the data and determine the principal factors influencing the corrosion rates of subsea pipelines, thus reducing the complexity of processing model data and increasing the efficiency of modelling operations. The penalty parameter γ and the kernel parameter \({\sigma ^2}\) are optimized through the NGO algorithm to increase the precision of the prediction model and address the challenges of inconsistent predictions and insufficient generalization capability. Through experimental validation and a comparison of the error metrics, the KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model is shown to outperform existing methods. Specifically, the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) is reduced to less than 2%, and the root mean square error (RMSE) is significantly lower than those of conventional models. The KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model provides reliable technical support for accurately predicting subsea pipeline corrosion rates. This model provides a scientific basis for optimizing corrosion protection strategies, guiding pipeline maintenance decisions, and ensuring flow safety. Furthermore, the model has significant potential in extending the service life of subsea pipelines and reducing operational and maintenance costs.

Principles of the NGO algorithm and LSSVM modelling

Principles of the NGO algorithm

The Northern Goshawk optimization (NGO) algorithm was introduced in 2022 by Mohammad Dehghani and colleagues. The algorithm replicates the Northern Goshawk’s behaviour during hunting, focusing on prey recognition, attack, pursuit, and evasion. The Northern Goshawk optimization algorithm divides the hunting process into two phases: prey identification and attack (exploration phase) and chasing and escape (exploitation phase)23.

Initialization

The Northern Goshawk algorithm can be represented by the following matrix for the Northern Goshawk population:

.

X is the population matrix of Northern Goshawks; Xi denotes the position of the ith Northern Goshawk; \({x_{i,j}}\) indicates the jth-dimensional position of the ith Northern Goshawk; N is the number of Northern Goshawk populations; and m refers to the number of dimensions in the solution problem.

In the Northern Goshawk optimization algorithm, the objective function of the problem is utilized to compute the objective function value of each Northern Goshawk; the objective function value of the Northern Goshawk population can be represented as a vector of objective function values:

.

where F is the objective function vector of the Northern Goshawk population and Fi is the objective function value of the ith Northern Goshawk population.

Prey identification and attack (Global search)

During the initial phase of hunting, the Northern Goshawk selects a prey item at random and attacks it quickly. This phase improves the NGO algorithm’s exploration capability by randomizing the selection of prey in the search space. In this phase, a global search of the search space is conducted to determine the optimal region. During this phase, the Northern Goshawks exhibit the prey selection and attack behaviours described in Eqs. (3)-(5):

.

Where Pi denotes the location of the ith Northern Goshawk’s prey; \({F_{{P_{\text{i}}}}}\) is the objective function value for the position of the ith Northern Goshawk’s prey; k represents a random integer within a specified range [1,N]; \(X_{{\text{i}}}^{{new,P1}}\) represents the updated location of the ith Northern Goshawk; \(x_{{i,j}}^{{new,P1}}\) represents the updated position in the jth dimension of the ith Northern Goshawk; \(F_{{\text{i}}}^{{{\text{new}},P1}}\) is the value of the objective function pertaining to the ith Northern Goshawk following the update process in phase 1; r is a random number within the interval [0, 1]; and I denotes a randomly selected integer, either 1 or 2.

Chase and escape (Localized search)

After a Northern Goshawk attacks its prey, the prey will attempt to escape capture. Thus, in the concluding phases of hunting, the Northern Goshawk must sustain its chase. The Northern Goshawks’ high pursuit speed enables them to chase and ultimately capture prey in nearly any circumstance. The simulation of this behaviour improves the algorithm’s capacity for local search within the search space. This hunting activity is presumed to be in proximity to an attack position with a radius R. In the subsequent phase, it is described by Eqs. (6)-(8):

.

Where t represents the current iteration number and T denotes the maximum iteration limit; \(\:{X}_{i}^{new,P2}\:\)represents the updated position of the ith Northern Goshawk during the second stage; \(x_{{i,j}}^{{new,P2}}\) represents the updated position of the jth dimension of \(X_{{\text{i}}}^{{new,P2}}\); and \(F_{{\text{i}}}^{{new,P2}}\) is the value of the objective function pertaining to the ith Northern Goshawk following the update process in the second stage.

LSSVM algorithm

Various machine learning algorithms, including backpropagation neural networks (BP), random forests (RF), and support vector machines (SVM), have been widely used to predict corrosion rates in subsea pipelines. While these methods have demonstrated varying degrees of success, they often face challenges in computational efficiency and model generalizability when dealing with small-to-medium scale datasets characterized by high dimensionality and strong nonlinearity. For instance, BP models typically require substantial computational resources and extensive hyperparameter tuning, while SVM and ensemble methods like RF may encounter overfitting risks in limited-data scenarios.

In contrast, Least Squares Support Vector Machines (LSSVM) show clear advantages in this particular application setting. In our preliminary study (see Figs. 2 and 3; Table 4), LSSVM consistently demonstrated superior performance metrics through systematic comparisons with three representative algorithms (BP, RF, and traditional SVM), with much higher prediction accuracy and stability than the other algorithms, and this improved performance stems from the unique mathematical formulation of the LSSVM, which converts the quadratic optimisation problem into a system of linear equations by means of equal constraints, thus ensuring a global optimisation solution while maintaining the simplicity of the model. ensuring a globally optimised solution while maintaining model simplicity. In addition, its structural risk minimisation principle enhances the generalisation capability, which is particularly important for offshore engineering applications where the cost of in situ data collection is high and the size of the dataset is limited.

As an advanced variant of support vector machines (SVM), LSSVM addresses the original algorithm’s computational complexity through innovative problem reformation. Where conventional SVM solves convex quadratic programming problems, LSSVM transforms this into solving linear equations via kernel space mapping and regularization techniques. This fundamental improvement not only accelerates computation but also improves numerical stability, making it particularly suitable for handling the sparse, high-dimensional corrosion datasets typical of subsea pipeline monitoring systems.

The LSSVM is an advanced learning and predictive algorithm derived from the conventional support vector machine (SVM) algorithm. This algorithm streamlines the solution of quadratic optimization problems by converting them into linear Eq. 24.

The steps for using the LSSVM algorithm are as follows:

For a given value from the training dataset \(\left( {{x_i}, {y_i}} \right)\), \({x_i}={\left( {{x_{i1}}, {x_{i2}}, \cdots , {x_{id}}} \right)^T}\) is the d-dimensional input vector, and the output data value is \({y_i}\); N is the total number of training data values.

-

(1)

To transform the input space into the feature space, a nonlinear function is employed, \(\phi \left( {{x_{\text{i}}}} \right)\). The process of estimating the nonlinear function is represented by Eq. (9)25:

Where \(\omega\) is the weight vector, b is the bias term, and \(\left\langle . \right\rangle\) denotes the inner product operation.

-

(2)

The precise values of parameters \(\omega\) and b are determined on the basis of the fundamental principle of risk mitigation:

Where c is the penalty factor and \({\xi _i}\) is the slack variable.

-

(3)

Introducing the Lagrangian operator \(\alpha\) yields the Lagrangian function:

-

(4)

Setting the derivatives of \(\overrightarrow \omega , b, \;{\xi _i}, \alpha\) to zero provides the conditions for finding the optimal solution of the problem.

-

(5)

Eliminating the parameters \(\overrightarrow \omega\) and \({\xi _i}\) in Eq. (11), we convert Eq. (12) into.

Where \(K\left( {{x_i},{x_j}} \right)\) is the kernel function, expressed as

A is the parameter of the kernel function. Data prediction can be performed by resolving the unknown data in Eqs. (13)26,27.

KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model

Kernel principal component analysis

High-dimensional feature values can lead to the curse of dimensionality; therefore, to extract the essential features and improve the predictive accuracy while minimizing the model complexity, kernel principal component analysis (KPCA) is applied to reduce the data dimensions28.

Kernel principal component analysis (KPCA) is a nonlinear dimensionality reduction method that transforms raw data into a high-dimensional feature space by utilizing a kernel function, followed by the application of principal component analysis (PCA) within that feature space.

The principles of the KPCA algorithm are as follows:

-

(1)

The sample set of the original running data \({x_k}\) is nonlinearly transformed on the basis of the nonlinear kernel function \(\Phi\), which maps \({x_k}\) to a high-dimensional linear feature space. Then, its covariance matrix is computed for the new sample set; i.e.,

-

(2)

The eigenvalues \(\lambda\) and eigenvectors \(\overrightarrow v\) of matrix C are calculated. The following condition must be satisfied:

-

(3)

A nonlinear function \(\overrightarrow \varphi \left( {{x_i}} \right)\) is introduced on both sides, and the eigenvectors are represented linearly from \(\overrightarrow \nu\) to \(\overrightarrow \varphi \left( {{x_i}} \right)\); i.e.,

-

(4)

The kernel function matrix \(\overrightarrow K \left( {i,j} \right)=\left\langle {\overrightarrow \varphi \left( {{x_i}} \right),\overrightarrow \varphi \left( {{x_j}} \right)} \right\rangle\) is defined and transformed:

where \(\overrightarrow \alpha\) is the eigenvector of K, the eigenvalue is \(mk\), and the subscript i denotes an element in the input dataset.

For any sample, the projection to the principal element \(\overrightarrow \varphi \left( x \right)\) in the feature space F is29:

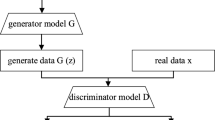

Predictive modelling

Initially, the KPCA algorithm is employed to reduce the dimensionality of the data, and the NGO algorithm is then applied to optimize the penalty parameter γ and the kernel parameter A of the LSSVM algorithm, thereby yielding a composite corrosion rate prediction model for subsea pipelines, referred to as the KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model. The flowchart of this process is shown in Fig. 1. The NGO-LSSVM and NGO-LSSVM models are established for validation against the integrated KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model.

Model evaluation indicators

To thoroughly assess the predictive accuracy of the KPCA-NGO-LSSVM corrosion rate model for subsea oil and gas pipelines, the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), root mean squared error (RMSE) and coefficient of determination (R2) were employed as evaluation metrics:

Where \({x_i}, {y_i}\) are the true and predicted values of the ith sample, respectively, for \(i=1,2, \cdots ,n;\) n is the total number of samples represented; MAPE indicates the model’s overall error; and RMSE denotes the deviation of the predicted values from the actual values. A lower MAPE and RMSE indicate greater prediction accuracy and better predictive performance of the model.

Example analysis

Dataset segmentation

Three distinct types of pipeline corrosion rate data from the literature were selected for algorithmic prediction. Due to space constraints, the predictive research process is detailed only for data 1, while results for data 2 and data 3 are presented in result form.

The data 1 in this paper are 50 subsea pipelines corrosion data from reference 30; some of the data values are shown in Tables 1 and 40 of which are chosen as the training set, and the remaining 10 of which are used as the test set for model prediction and error checking.

The data 2 in this paper are 100 overseas oil and gas pipelines corrosion data from reference31; some of the data values are shown in Tables 2, 80 of which are chosen as the training set, and the remaining 20 of which are used as the test set for model prediction and error checking.

The data 3 in this paper are 28 subsea multiphase flow pipelines corrosion data from reference32; some of the data values are shown in Table 3 and 22 of which are chosen as the training set, and the remaining 6 of which are used as the test set for model prediction and error checking.

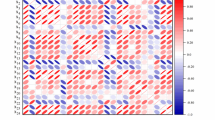

Data preprocessing

In kernel principal component analysis, the kernel function can be used to map the original data to a high-dimensional space, perform nonlinear dimensionality reduction, and mine the nonlinear information in the data.21 Therefore, nine influencing factors in subsea pipeline corrosion rate for data 1 were downscaled using KPCA. The magnitudes of the variance contributions of the nine principal components were obtained in MATLAB 2020a, as shown in Table 4.

The magnitudes of the eigenvalues and the cumulative contributions reflect the magnitudes of the influence of the principal components, as shown in Table 4. In this work, the first six principal components F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, and F6, with cumulative contributions greater than 85% were extracted.

The eigenvectors of the first six principal components selected in this paper are shown in Table 5. The eigenvector of each principal component indicates each factor’s explanatory ability, and the closer the absolute value is to one, the stronger its explanatory ability is, implying that the factor has a greater influence on subsea pipeline corrosion. As shown in Table 5, F1 has a greater correlation with system pressure, F2 with a medium flow rate, F3 with pH, F4 with water content, F5 with temperature, and F6 with CO2 partial pressure.

Finally, the system pressure, water content, medium flow rate, pH, temperature, and CO2 partial pressure all have greater impacts on subsea pipeline corrosion rates for data 1 than the other factors. The above subsea pipeline corrosion factors are substituted into the combined model for the next prediction.

Analysis of the forecast results

Based on the characteristics of small sample size and high-dimensional features in the dataset, we initially selected four machine learning algorithms—BP, LSSVM, SVM and RF—for comparative analysis. The results (Figs. 2 and 3; Tables 6and 7) demonstrate that the LSSVM model outperforms the RF, BP and SVM models in terms of prediction accuracy and stability. Therefore, we adopted the LSSVM algorithm as the predictive model for estimating the corrosion rate of submarine pipelines.

Four optimized portfolio models based on the LSSVM algorithm were subsequently developed and compared. The results indicate that the predictive outcomes of the integrated KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model and three other combined models after training are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, and Table 8. Figure 4 shows that the KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model yields superior predictions and stability, followed by the NGO-LSSVM model, whereas the KPCA-PSO-LSSVM model and PSO-LSSVM model yield the worst predictions and least stability.

As shown in Figs. 4 and 5, and Table 8, the stability of the predicted values of the KPCA-PSO-LSSVM and PSO-LSSVM models is low overall, with maximum relative errors of 5.42% and 5.81% and average relative errors of 3.59% and 4.27%, respectively. The predicted values of the NGO-LSSVM model exhibit good stability, with a maximum relative error of 5.10% and an average relative error of 2.49%. The KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model exhibits superior performance, demonstrating optimal stability in terms of the predicted values, with a maximum relative error of 4.80% and an average relative error of 1.80%, both of which are lower than those of the other models, indicating the most effective predictions.

Similarly, prediction studies were also performed for Data 2 and Data 3 using these four algorithms. The comparative indicators of their prediction results are presented in Tables 10 and 11.

From Tables 9 and 10, and 11, along with the prediction results across multiple datasets, the KPCA-NGO-LSSVM algorithm exhibits optimal stability in predicted values and significantly outperforms the NGO-LSSVM, KPCA-PSO-LSSVM, and PSO-LSSVM algorithms in prediction accuracy.

Conclusion

This paper presents the fundamental principles of the KPCA, NGO, and LSSVM algorithms and establishes a composite model for predicting the corrosion rates of subsea pipelines utilizing the KPCA-NGO-LSSVM approach. The following conclusions are derived from the validation and error analysis of the corrosion rate data pertaining to subsea pipelines:

-

(1)

The KPCA algorithm was utilized for data dimensionality reduction to obtain the six factors that have the greatest influence on the corrosion rates of subsea pipelines, i.e., system pressure, water content, pH, temperature, and CO2 partial pressure. The multiple correlations between the influencing factors were eliminated, the complexity of the data was reduced, and the efficiency of the modelling operation was improved.

-

(2)

Based on the data characteristics, four algorithms—BP, SVM, LSSVM, and RF—were selected and compared. The LSSVM model has a MAPE of 7.1398%, an RMSE of 0.1939 and an R2 of 0.8047, which indicated that the LSSVM algorithm demonstrated significantly better predictive performance and stability than the other algorithms. Therefore, LSSVM was adopted as the predictive model for estimating the corrosion rate of subsea pipelines.

-

(3)

Based on prediction results from three distinct datasets, the combined KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model demonstrates significantly superior prediction accuracy and stability compared to the other three models. These results demonstrate that the combined KPCA-NGO-LSSVM model achieves higher prediction accuracy and superior stability for subsea pipeline corrosion rate prediction. This model provides robust technical support for accurately predicting corrosion rates, offering significant potential for extending the service life of subsea pipelines and reducing operational and maintenance costs.

-

(4)

The predictive accuracy and stability of the algorithmic model improve with larger data samples. Consequently, a comprehensive pipeline corrosion database could be developed to derive a corrosion rate prediction model with broader applicability and enhanced efficacy.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper (Data 1 from paper 30: https://doi.org/10.27393/d.cnki.gxazu.2020.000585), (Data 2 from paper 31: https://doi.org/10.27643/d.cnki.gsybu.2023.000192), (Data 3 from paper 32: https://doi.org/10.26995/d.cnki.gdqsc.2020.000788).

References

1. Xiao,R;Jin,S. Corrosion rate prediction of submarine pipelines based on WOA-BP algorithm. J. Marine Science,46(06):116–123(2022).

2. MAHMOODIAN M,LI CQ. Structural integrity of corrosion-affected cast iron water pipes using a reliability-based stochastic analysis method. J. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering,12(10):1356–1363(2016).

3. Cui,M. Research on corrosion and residual strength within CO2 of multi-phase flow sea pipe. D. China University of Petroleum(East China),2014.

4. Xiao,R;Liu,G;Liu,B;et al. Research on corrosion rate prediction in submarine pipelines based on PCA-TSO-BPNN model. J/OL. Thermal Processing Technology,1–7(2024).

5. Lu,P;Wang,X;Yang,W;et al. Improved reptile search algorithm to optimize ENN model to predict pipeline corrosion rate. J. Science Technology and Engineering, 23(30):12942–12950(2023).

6. Xiao,S;Du,C;Wang,C. Improved sparrow search algorithm to optimize BP neural network pipeline corrosion rate prediction model. J. Oil and Gas Storage and Transportation, 43(7):760–768, 795(2024).

7. Ma,M;Zhao,Z. Corrosion rate prediction of process pipelines based on KPCA-CSO-RVM model. J. Safety and Environmental Engineering, 28(04):1–7 + 20(2021).

8. Lv,L;Wang,J;Qi,Q;et al. Corrosion rate prediction model for oil and gas mixed transport pipelines based on KPCA-IGOA-ELM. J. Oil and Gas Storage and Transportation, 42(7):785–792(2023).

9. Xiao,B;Zhang,H;Liu,H. Application of improved PSO-BPNN algorithm in pipeline corrosion prediction. J. Journal of Zhengzhou University (Engineering Edition), 43(01):27–33(2022).

10. Jin,L;Zeng,D;Meng,K;et al. Research on corrosion prediction model of submarine pipeline based on GWO-LSSVM algorithm. J. Oil and Gas Chemical Industry, 51(02):70–76(2022).

11. Li,S;Du,H;Cui,Q;Liu,P;Ma,X;Wang,H. Pipeline Corrosion Prediction Using the Grey Model and Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm. J. Axioms ,11,289(2022).

12. Zhou,Y; Peng,X;Geng,Y;et al. Internal corrosion rate prediction of shale gas gathering pipeline based on KPCA-GA-BP model. J. Corrosion and Protection, 45(04):63–68(2024).

13. Huang,G;Zhou,Y;Yan S;et al. Prediction of external corrosion rate of buried pipelines based on KPCA-CS-SVM. J. Thermal Processing Technology,51(16):38–43(2022).

14. Chang.E. Research on the prediction of external corrosion rate of marine oil and gas pipelines based on GM(1,1) and ELM. D. Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology,2022.

15. Ling,X;Xu,L;Gao,J;et al. Prediction of external corrosion rate of long-distance pipeline based on IFA-BPNN. J. Surface Technology,50(04):285–293(2021).

16. Jin,W;Yao,S;,Jin,Y;et al. Improved DGM(1,1) modeling and validation of pipeline corrosion rate over time. J. Journal of Safety and Environment,22(01):77–83(2022).

17. Biezma M V, Agudo D, Barron G.A fuzzy logic method: Predicting pipeline external corrosion rate. J .International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping,163:55–62(2018).

18. Zhang,Y;Yang,J;. Prediction of pipeline corrosion rate based on BP neural network. J. Total Corrosion Control,27(9):67–71(2013).

19. Shaik, N.B., Pedapati, S.R., Othman, A.R. et al. An intelligent model to predict the life condition of crude oil pipelines using artificial neural networks. Neural Comput & Applic 33, 14771–14792 (2021).

20. Bo,T;Yu,H;Song,W;. Construction of pipeline corrosion prediction model with improved MGM(1,1). J. Mechanical Design and Manufacturing Engineering,51(04):69–73(2022).

21. Jia,H;Hu,L;Li,X;et al. Corrosion risk prediction in submarine pipelines based on kernel principal component analysis algorithm. J. Corrosion and Protection,44(03):82–87(2023).

22. Shaik, N.B., Jongkittinarukorn, K., Benjapolakul, W. et al. A novel neural network-based framework to estimate oil and gas pipelines life with missing input parameters. Sci Rep 14, 4511 (2024).

23. Fu,X;Zhu,L;Huang,J;et al. Multi-threshold image segmentation based on improved northern hawk optimization algorithm. J. Computer Engineering,49(07):232–241(2023).

24. Zhang,Jia;Li,L;Wang,H;et al. Research on the prediction of pipeline corrosion residual strength based on IWOA-LSSVM. J. Mechanical Strength,46(02):468–475(2024).

25. XUE X H,XIAO M. Deformation evaluation on surrounding rocks of underground caverns based on PSO-LSSVM. J .Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology,69:171–181(2017).

26. SHAYEGHIH,GHASEMI A,MORADZADEH M, et al. Day-ahead electricity price forecasting using WPT,GMI and modified LSSVM-based S-OLABC algorithm. J .Soft Computing-A Fusion of Foundations Methodologies and Appications,21(2):525–541(2017).

27. YARVEICY H,MOGHADDAM A K,GHIASI M, Practical use of statistical learning theory for modeling freezing point depression of electrolyte solutions: LSSVM model. J .Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering,20:414–421(2014).

28. Song,C;Zhang,X. A fast PCA-based algorithm for solving large systems of hyperdeterministic linear equations and applications. J. Intelligent Computer and Applications,9(4):91–95(2019).

29. GORJAEI R G,SONGOLZDEH R,TORKAMAN M, et al. A novel PSO-LSSVM model for predicting liquid rate of two phase flow through wellhead choke. J .Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering,24:228–237(2015).

30. Ying,S. Research on corrosion rate prediction in in-service submarine oil and gas pipelines. D. Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology,2020.

31. Ya.Z. Research on corrosion rate prediction model of overseas oil and gas pipelines .D. China University of Petroleum (Beijing), 2023.

32. Bin.L. Research on corrosion rate prediction of a submarine multiphase flow pipeline based on artificial intelligence .D. Northeast Petroleum University, 2020.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2023-JC-YB-421) and the Xi’an Shiyou University Graduate Innovation Fund Program (YCX2413059) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S: Reviewed and edited the manuscript, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. H.C: Wrote the main manuscript, Analysis and investigate data, Supervision. Z.H: Did experiment data, Projected administration, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, S., Huang, C. & Zhao, H. Prediction of the corrosion rates of subsea pipelines via KPCA. Sci Rep 15, 24498 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09685-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09685-6