Abstract

The rock fragmentation mechanism of polycrystalline diamond compact (PDC) constitutes a fundamental research focus in petroleum and mining engineering. This study presents an experimental investigation into crack propagation failure characteristics during cutter-rock interaction. Through an integrated experimental approach combining mechanical testing with digital image correlation (DIC) monitoring, the complete failure process from microcrack initiation to macroscopic fracture network development was quantitatively characterized. Experimental observations demonstrate significant dependence of crack propagation patterns on PDC cutter geometry, particularly the back rake angle. Initial fracture development (Stage I) exhibits predominant shear failure mechanisms, with tensile crack formation becoming progressively dominant during sustained loading (Stage II). The DIC-derived Displacement Field analysis revealed three distinct crack interaction modes: parallel propagation, bifurcation merging, and hierarchical networking. These findings provide a solid theoretical foundation for further research on PDC rock-breaking mechanisms, contributing to the optimization of drilling operations in engineering applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycrystalline Diamond Compact (PDC) bits have emerged as indispensable tools across a wide range of engineering applications, particularly in oil and gas exploration. Their exceptional cutting efficiency enables rapid penetration through complex geological formations, significantly enhancing drilling speeds, reducing operational cycles, and lowering extraction cost1. In unconventional resource development, such as shale gas extraction, PDC bits demonstrate remarkable adaptability to challenging formations, facilitating efficient resource recovery2. Additionally, their application in geological surveys provides critical insights into deep subsurface structures, aiding resource assessment and exploration3. Beyond hydrocarbon extraction, PDC bits are extensively utilized in water well drilling and mining operations, driving advancements in energy extraction and geological research due to their superior wear resistance and operational efficiency4,5. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of rock fracture mechanisms and failure modes under PDC bit action is crucial for optimizing extraction efficiency, improving engineering design, and ensuring operational safety.

Significant progress has been made in understanding rock fracture under PDC bit action. Research has identified three primary crack modes: tensile, shear, and mixed-mode fractures. In brittle rocks, tensile cracks dominate, rapidly initiating and propagating under high-speed cutter penetration, while shear cracks prevail in ductile rocks6. However, the transition conditions between these crack modes remain poorly understood, particularly in relation to the microstructural heterogeneity of different rock types, highlighting the need for a unified theoretical framework. Crack morphology studies reveal diverse geometric patterns, including linear, curved, and branched forms, with a predominance of small-scale fractures7. Nevertheless, existing models struggle to accurately predict crack patterns and distributions in rocks with complex joint and fault systems, limiting their applicability in challenging geological conditions. Furthermore, while rock mechanical properties, cutter geometry, and loading conditions significantly influence crack propagation8real-time monitoring techniques and simulation algorithms face limitations in capturing the dynamic, multi-factor coupling effects prevalent in actual drilling operations.

In the study of rock failure modes under single-cutter PDC bit action, researchers have identified three primary mechanisms: tensile, shear, and mixed-mode failures. In brittle rocks, tensile cracks initiate and propagate rapidly due to low tensile strength, resulting in relatively smooth fracture surfaces9. In contrast, shear failures dominate in ductile rocks, characterized by irregular fracture surfaces and accompanied by plastic deformation10. Studies have also demonstrated the significant influence of loading rates and cutter geometry on failure mechanisms, with higher loading rates accelerating failure in brittle rocks and optimized cutter designs enhancing rock-breaking efficiency11. Despite these advancements, critical gaps remain. The effects of multi-factor coupling under complex geological conditions—such as high temperature, high pressure, and heterogeneous mineral compositions—are not fully understood, lacking systematic theoretical analysis and model development12. Furthermore, the dynamic evolution of failure modes across different rock types under varying loading conditions remains unclear, limiting the ability to predict mechanical responses during rock breaking. Additionally, the disparity between laboratory simulations and actual drilling conditions poses challenges in translating experimental findings to practical engineering applications13.

The analysis of internal crack morphology in rocks under single-cutter PDC bit action provides valuable insights into failure mechanisms14. Linear cracks perpendicular to the cutter force typically indicate tensile failure in brittle rocks, characterized by smooth fracture surfaces15. Conversely, curved or irregular cracks with pronounced branching are associated with shear failure in ductile rocks, often accompanied by plastic deformation16. Mixed-mode failures exhibit characteristics of both tensile and shear cracks17,18. This study aims to elucidate rock failure modes by examining internal crack morphology under single-cutter PDC bit action.

In rock mechanics research, Digital Image Correlation (DIC) has become an essential tool for investigating displacement and strain fields associated with internal crack propagation19. The non-contact measurement capabilities of DIC enable precise tracking of crack initiation and propagation, capturing even minute displacement changes during loading20. In brittle rocks, DIC has provided detailed observations of crack evolution, offering reliable data for understanding fracture mechanisms21. For ductile rocks, DIC has revealed complex strain distributions around crack tips, enhancing our understanding of deformation characteristics under various loading conditions22. The displacement and strain data obtained through DIC have facilitated the development of more accurate constitutive models that incorporate fracture mechanics, significantly improving the predictability of rock mechanical behavior and advancing theoretical frameworks in rock mechanics23,24.

By investigating internal crack morphology, utilizing DIC for strain field analysis, and examining failure modes under PDC bit action, this research provides fundamental insights into the mechanical behavior and failure mechanisms of rocks. These findings not only enhance the efficiency and quality of rock extraction but also offer theoretical foundations for engineering design and construction. Future research should focus on deepening our understanding of internal crack propagation mechanisms and developing more effective experimental methods and theoretical models to address the challenges in this field.

Materials and methodology

Experimental setups

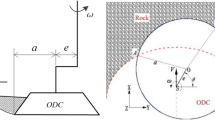

To investigate the crack extension pattern inside the rock under the action of PDC, a series of rock linear cutting tests were conducted on a custom-designed experimental platform (as shown in Fig. 1). As illustrated in the accompanying figure, the rock specimen is securely fixed in the clamping device of the testing apparatus. The drill bit holding mechanism is capable of precise vertical movement, enabling accurate control of the cutting depth within a range of 0–15 mm, with a resolution of 0.01 mm. Additionally, the platform facilitates horizontal movement to achieve linear cutting of the rock specimen.

The PDC cutter is mounted on the drill bit holding device, which is equipped with an angle adjustment mechanism to set the back rake angle of the cutter. The back rake angle can be adjusted within a range of 0–60°, with predefined settings at 0°, 15°, 30°, 45°, and 60°. Real-time monitoring of the cutting forces is achieved through a spoke-type tension load cell installed between the rock specimen clamping device and the force arm. The cutting experiments can be conducted in two control modes: force control, where the drill bit advances at a specified cutting force, and displacement control, where the drill bit operates based on predefined displacement targets and rates. This study primarily employs the displacement control mode to obtain the cutting force versus displacement curves during linear cutting, capturing real-time cutting forces.

The cutting process and crack propagation are recorded using Digital Image Correlation (DIC) technology, which provides detailed visualization of the cutting phenomena and crack distribution. This enables comprehensive analysis of the cutting process and crack evolution, as well as the strain development throughout the experiment. By analyzing the acquired data and images, the study aims to provide a clearer understanding of rock failure behavior and mechanisms under varying loading conditions, thereby enhancing the predictive accuracy of the proposed model.

A typical pick was used for tests, which consisted of pick body and a tip embedded in pick body. The pick body and embedded tip are made of cast iron and cemented carbide, respectively. The shape and size of pick are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

The steps of this linear cutting tests were illustrated as below:

(1) Sample fixation: place the sample on the sample clamping device and fix it to ensure that the sample is firmly fixed to avoid displacement or shaking during the subsequent experiments.

(2) Installation of PDC drill bit: according to the required cutting angle, install the PDC drill bit in the corresponding position of the cutting teeth holder to fix it.

(3) Depth of cutting adjustment: by operating the depth of cutting adjustment device, the drill bit fixing device can move up and down precisely to control the cutting depth, with an adjustment range of 0–15 mm (with an accuracy of 0.01 mm).

(4) DIC device debugging and calibration: As shown in Figs. 4 and 5,adjust the position and focal length of the camera of the DIC device, according to the requirements of the experiment, adjusted in real time through the image feedback, until the image obtained by the camera is clear and complete, and then carry out the sample calibration to ensure that it meets the experimental data collection requirements.

(5) Starting the experiment: As shown in Figs. 6 and 7, set the cutting rate and cutting endpoint and other parameters in the control system, after confirming that there is no error, start the experiment. The rock specimen moves horizontally to the PDC drill bit at the set cutting speed along with the test bench.

Rock specimen Preparation and experimental design

For the cutting experiments, a Φ19 × 13 mm PDC cutter, commonly used in petroleum drilling applications, was employed. Three types of rocks—limestone, marble, and sandstone—were selected based on their homogeneity, isotropy, and absence of visible pre-existing fractures. These rock specimens were meticulously machined into blocks measuring 100 × 95 × 5 mm (Fig. 8). To ensure experimental consistency, the surfaces of the blocks were polished to a high finish, and strict tolerances were maintained for the parallelism of opposing faces. This preparation process guarantees the reliability and repeatability of the experimental results, providing a robust foundation for analyzing the cutting mechanics and fracture behavior under PDC cutter action.

The experimental design focuses on investigating the influence of rock type and cutter geometry on cutting forces, crack propagation, and failure mechanisms. The selection of limestone, marble, and sandstone allows for a comparative analysis of rock behavior across a range of mechanical properties, including hardness, brittleness, and grain structure. The polished surfaces facilitate accurate strain measurement and crack observation using DIC technology, while the precise dimensional control ensures uniform loading conditions during the cutting tests. This systematic approach enables a comprehensive understanding of the interaction between PDC cutters and different rock types, contributing to the optimization of drilling operations in various geological settings.

The physical and mechanical properties of these rocks are shown in Table 1:

In this experiment, parameters such as cutting depth, rake angle, and rock type were changed, and repeated tests were conducted. The parameter design of the experiment is shown in Table 2.

Fundamentals of DIC (Digital image Correlation) technology

DIC integrates conventional digital photography with civil engineering measurement techniques to accurately quantify structural surface deformations. By capturing precisely aligned and localized images, DIC enables the comparison of measurements and identification of displacement variations, as illustrated in the accompanying figure. The technique employs high-speed cameras to track the deformation of a region centered at point A (x₀, y₀), denoted as f₀, to its deformed state centered at point B (x₁, y₁), denoted as f₁ (Fig. 9). Within the region f₀, a point C (x, y) undergoes displacement to point C′ (x′, y′) in the deformed region f₁. The relationship between these points is described by the following transformation equations:

This formulation allows for precise quantification of strain fields and deformation patterns, providing critical insights into the mechanical behavior of materials under load. The high-resolution imaging and advanced correlation algorithms employed in DIC ensure accurate measurement of both small- and large-scale deformations, making it an indispensable tool for experimental mechanics and structural analysis.

By leveraging DIC, this study captures the full-field displacement and strain evolution during rock cutting, enabling a detailed analysis of crack initiation, propagation, and failure mechanisms. The technique’s non-contact nature and high spatial resolution make it particularly suitable for studying brittle and heterogeneous materials, such as rocks, under dynamic loading conditions. The resulting data provide a deeper understanding of the complex interactions between PDC cutters and rock formations.

Crack propagation and failure modes

Crack type identification and classification

To investigate the characteristics of internal cracks in rocks under PDC cutter action, a systematic analysis was conducted by selecting multiple pairs of symmetric points, H₁ and H₀, on either side of the crack. The displacements of these points were transformed from the original u-ν coordinate system to a local u′-ν′ coordinate system, as illustrated in Fig. 10. Based on the u′ and ν′ displacement components of points H₁ and H₀, the cracks were classified into three distinct types, as depicted in Fig. 11:

-

1.

Tensile Cracks (Mode I): When the u′ components of the symmetric points exhibit opposite signs (one positive and one negative), it indicates that the points on either side of the crack are moving away from each other in a direction perpendicular to the crack. This behavior is characteristic of tensile cracks (Mode I).

-

2.

Shear Cracks (Mode II): If the difference in the ν′ components of points H₁ and H₀ exceeds a threshold value of 0.01, it signifies that the points on either side of the crack are undergoing relative motion in opposite directions parallel to the crack. This behavior is indicative of shear cracks (Mode II).

-

3.

Mixed-Mode Cracks (Mode I-II): When the u′ components of the symmetric points show opposite signs and the difference in the ν′ components exceeds 0.01, the crack is classified as a mixed-mode crack (Mode I-II), exhibiting both tensile and shear characteristics.

By analyzing the displacement patterns of symmetric points, this methodology enables precise classification of crack types, providing critical insights into the mechanisms of crack propagation within rocks. This approach not only enhances the understanding of rock fracture behavior under PDC cutter action but also serves as a robust foundation for developing predictive models and optimizing drilling operations in various geological settings. The results of this analysis offering a quantitative framework for characterizing complex fracture patterns and their evolution under mechanical loading.

Crack propagation processes and morphological evolution

Figure 12 illustrates the crack propagation patterns observed during the cutting process with a back rake angle (α) of 45°. Given the relatively small scale of the cracks, four pairs of symmetric points were selected on either side of each crack for detailed analysis. This approach ensures a comprehensive evaluation of the displacement and strain fields associated with crack initiation and growth. The symmetric point analysis provides critical insights into the local deformation behavior, enabling the classification of crack types (Mode I, Mode II, or mixed-mode) and the quantification of crack opening and sliding displacements. By examining the displacement trends of these symmetric points, the study elucidates the influence of cutter geometry on crack propagation mechanisms, contributing to a deeper understanding of rock fracture dynamics under PDC cutter action.

Figure 13 presents a systematic observation of crack evolution mechanisms during rock cutting, utilizing displacement field analysis based on Digital Image Correlation (DIC) technology (what is shown in Fig. 13 is not complete specimen, but a selected analysis region for Digital Image Correlation (DIC) analysis).

Digital Image Correlation (DIC) cloud maps in rock cutting process reflect the evolution of displacement field. At the initial stage of cutting, the rock material in front of the cutter undergoes shear deformation. The DIC cloud map shows a significant shear displacement concentration zone, and cracks are initiated due to shear displacement. As the cutting progresses, with the expansion of cracks, a small amount of tensile displacement appears at the crack tip and surrounding areas. However, throughout the process, shear displacement is dominant, which can be seen from the large - scale distribution of shear - related displacement patterns in the cloud maps.

From the perspective of stress, the initial shear displacement is caused by shear stress. When the shear stress exceeds the rock’s shear strength, cracks start to form. In the subsequent development, although tensile stress is generated due to the change of displacement field (resulting in tensile displacement), the overall stress state is still dominated by shear stress. The distribution and evolution of displacement in the DIC cloud maps also verify that the shear stress plays a leading role in driving crack generation and development, and the tensile stress only has a secondary and local influence.

In general, the DIC cloud maps clearly show that in rock cutting, crack generation and development are mainly under the action of shear - dominated displacement and stress, with tensile - related factors playing a supplementary role.

As depicted in Fig. 14, the DIC system precisely monitors the normal (N) and tangential (T) displacements of symmetric points on either side of internal cracks within the rock mass under the action of a single PDC cutter. The crack evolution can be divided into two distinct phases based on the displacement characteristics:

-

4.

Pure Shear Phase (Initial Stage): During the initial phase, the tangential displacement difference increases rapidly, indicating significant relative sliding between the rock masses on either side of the crack due to the shear force exerted by the cutter. In contrast, the normal displacement difference remains minimal, suggesting that the crack propagation is predominantly governed by shear stress, exhibiting a pure shear mode.

-

5.

Tensile-Shear Coupling Phase (Progressive Stage): As the cutter continues to act on the rock, the crack transitions into a tensile-shear coupling phase. Here, the normal displacement difference begins to increase significantly, reflecting the growing influence of tensile stress and the tendency for the crack surfaces to separate. Simultaneously, the tangential displacement difference remains substantial and continues to evolve, indicating that shear stress still plays a critical role. As shown in Fig. 14 d, shear failure remains dominant during this phase, but the crack morphology becomes more complex, combining both tensile and shear characteristics.

By comparing the normal and tangential displacement data of symmetric points at the same moment, the dynamic variation trend of the displacement difference between the two types can be clearly deduced. The analysis of displacement differences leads to the following conclusions: By monitoring the normal and tangential displacement differences using DIC, the transition from pure shear to tensile-shear coupling can be clearly captured. Under the action of a single PDC cutter, rock cracks initially propagate in a pure shear mode before transitioning to a tensile-shear coupling phase. This evolution from a simple shear-dominated morphology to a complex mixed-mode morphology provides critical insights into the rock-breaking mechanism. These findings enhance our understanding of the fracture dynamics in rocks under PDC.

Internal crack morphology variations

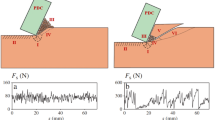

As illustrated in Fig. 15(a), when the back rake angle (α) of the PDC cutter is set to 30°, both tangential and normal displacement differences are observed at the crack initiation point. According to fracture mechanics principles, the tangential displacement difference indicates the presence of shear stress, while the normal displacement difference signifies tensile stress. This suggests that, at a back rake angle of 30°, crack initiation is driven by a combination of shear and tensile stresses.

In contrast, as shown in Fig. 15(b) and 15(c), for back rake angles of 45° and 60°, only tangential displacement differences are detected at the crack initiation point, implying that crack formation is primarily induced by shear stress. This observation highlights a significant shift in the stress state and failure mechanism as the back rake angle increases. Specifically, the rock failure mode transitions from a mixed stress state (shear and tensile) to a shear-dominated failure mechanism.

These findings demonstrate that the back rake angle plays a critical role in determining the stress distribution and failure behavior of rocks under PDC cutter action. At lower back rake angles, the interaction between shear and tensile stresses leads to complex crack initiation and propagation, while higher back rake angles promote shear-dominated failure.

Figure 16 presents the normal and tangential displacements of symmetric points at the crack tip under three different back rake angles (α). A clear trend emerges from the comparative analysis of the data in Fig. 16(a), 16(b), and 16(c): as the back rake angle increases, the ratio of tangential to normal displacement differences at the crack tip also increases. This trend indicates that the influence of shear stress becomes progressively more dominant relative to tensile stress during crack initiation and propagation at the crack tip.

The increasing ratio of tangential to normal displacement differences aligns closely with the observations in Fig. 15, further validating that shear stress plays a more critical role in rock failure as the back rake angle increases. These results highlight the significant impact of cutter geometry on the stress state and failure mechanisms in rocks. Specifically, higher back rake angles promote shear-dominated failure, while lower angles result in a more balanced contribution of shear and tensile stresses.

This study provides critical insights into the relationship between back rake angle, stress distribution, and crack propagation behavior. The findings underscore the importance of optimizing cutter geometry to control fracture patterns and enhance drilling efficiency in various geological conditions.

Conclusions

This study employs Digital Image Correlation (DIC) technology to investigate the rock failure process. Through detailed analysis of rock surface images, a novel diagnostic methodology for fracture mode identification is developed through kinematic analysis of symmetric point displacement vectors. Experimental data analysis reveals that coexisting tensile (Mode I) and shear (Mode II) fracture trajectories, confirming a mixed-mode I/II fracture mechanism during liner cutting. Quantitative stress field reconstruction demonstrates progressive transformation of rock’s internal stress state: initial triaxial tension-shear coupling evolves into shear-dominant stress configuration with increased cutter penetration depth. Mechanistic analysis establishes shear stress dominance in crack nucleation processes under liner cutting. The critical phase of crack initiation exhibits localized shear stress intensification, triggering rapid fracture nucleation within cutter-proximal zones. While tensile stress components facilitate crack opening during propagation phase, shear stress redistribution governs three essential aspects of fracture dynamics. These findings provide a comprehensive understanding of rock failure mechanisms under PDC cutter, offering valuable insights for optimizing cutter design and drilling operations.

Data availability

Data Availability StatementThe datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.Sincerely! Boxin Du23204228102@stu.xust.edu.cn.

References

Smith, J. The influence of rock properties on the crack propagation in PDC cutting[J]. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 165, 12–20 (2018).

Pessier, R. & Damschen, M. Hybrid Bits Offer Distinct Advantages in Selected roller-cone and PDC-bit applications[J]2696–103 (SPE Drilling & Completion, 2011). 01.

Kerr, C. J. PDC drill bit design and field application evolution[J]. J. Petrol. Technol. 40 (03), 327–332 (1988).

Sun, Y. et al. Research and application of PDC coring bit in marine drilling[C]//Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, 2901(1): 012038. (2024).

Wang, B., Li, J., Zou, D. & Design & Application of a PDC Hybrid Drill Bit with Impregnated—Diamond Cutter (IDC) for the Hard and Strong Abrasive Formations[C]//ARMA US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium. ARMA, : ARMA-2020-1606. (2020).

Xi, Y. et al. Numerical investigations on rock breaking mechanism and parameter influence of torsional percussive drilling with a single PDC cutter[J]. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 210, 110077 (2022).

Shao, F. et al. Analysis of failure modes and impact resistance factors of PDC cutters[J]. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 244, 213462 (2025).

Akbari, B. et al. Dynamic single PDC cutter rock drilling modeling and simulations focusing on rate of penetration using distinct element method[C]//ARMA US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium. ARMA, 2011: ARMA-11-379.

Li, W., Ling, X. & Pu, H. Development of a Cutting Force Model for a Single PDC Cutter Based on the Rock Stress state[J]53185–200 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2020). 1.

Yang, Y. et al. Study on rock-breaking mechanism of the vertical wheel PDC bits[J]. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 244, 213428 (2025).

Yang, L. et al. Numerical investigation of rock-breaking mechanisms and influencing factors of different PDC cutters during rotary percussion drilling[J]. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 241, 213144 (2024).

Sun, Z. et al. Cracking Behaviors of Rocks Subjected To the Dynamic Percussion of a Single PDC Cutter: A Finite-Discrete Element Study[J]1–33 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2024).

Rostamsowlat, I., Evans, B. & Kwon, H. J. A review of the frictional contact in rock cutting with a PDC bit[J]. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109665 (2022).

Nunez, Y. J. et al. Analysis, Comparison, and Results of the Effectiveness of a PDC Bit Containing Fracturing and Shearing Elements When Drilling Challenging Heterogeneous Section Containing Massive Cherts[C]//Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference. SPE, : D042S203R003. (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Kinematic and bottom-hole pattern analysis of a composite drill bit of cross-scraping[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, 231(17): 3104–3117. (2017).

Crane, D. et al. Innovative PDC cutter with elongated ridge combines shear and crush action to improve PDC bit performance[C]//SPE middle east oil and gas show and conference. SPE, 2017: D031S014R004.

Liu, L. et al. Underlying Mechanisms of Crack Initiation for Granitic Rocks Containing a Single pre-existing Flaw: Insights from Digital Image Correlation (DIC) analysis[J]54857–873 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2021).

Ju, M. et al. Rate effect on crack propagation measurement results with crack propagation gauge, digital image correlation, and visual methods[J]. Eng. Fract. Mech. 219, 106537 (2019).

Miao, S. et al. A New DIC-based Method To Identify the Crack Mechanism and Applications in Fracture Analysis of Red Sandstone Containing a Single flaw[J]543847–3871 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2021).

Yue, Z. et al. Applications of Digital Image Correlation (DIC) and the Strain Gage Method for Measuring Dynamic Mode I Fracture Parameters of the White Marble specimen[J]524203–4216 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2019).

Zhou, T. et al. Failure and Mechanical Behaviors of Sandstone Containing a pre-existing Flaw Under compressive–shear Loads: Insight from a Digital Image Correlation (DIC) analysis[J]554237–4256 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2022). 7.

PENG, S. et al. Experimental study on loading rate effects of sandstone deformation localization based on 3D-DIC technology[J]. Rock. Soil. Mech. 41 (11), 4 (2021).

Gerbaud, L., Menand, S. & Sellami, H. PDC bits: All comes from the cutter/rock interaction[C]//SPE/IADC Drilling Conference and Exhibition. SPE, : SPE-98988-MS. (2006).

Yang, Y. et al. Research on the working mechanism of the PDC drill bit in compound drilling[J]. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 185, 106647 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yu Liang: Focused on the data analysis and interpretation. Using advanced statistical and analytical methods, Yu Liang processed the large - scale data obtained from the mechanical tests and DIC - derived strain fields. They identified and classified the three distinct crack interaction modes (parallel propagation, bifurcation merging, and hierarchical networking) through in - depth data mining and analysis. Yu Liang also developed mathematical models to quantitatively describe the relationships between various factors, such as the back rake angle of PDC cutters and the crack propagation characteristics. Their work provided a solid theoretical basis for understanding the PDC rock - breaking process, and their interpretations of the results were crucial for linking the experimental findings with practical engineering applications.BOxin Du: Primarily responsible for the experimental implementation. BOxin Du meticulously conducted all mechanical tests, accurately controlling experimental parameters such as the applied force and loading rate to simulate real - world cutter - rock interaction scenarios. They were also in charge of operating the DIC monitoring system, ensuring the high - quality acquisition of digital images throughout the experiment. Their proficiency in experimental techniques guaranteed the integrity and accuracy of the data collected during the observation of the complete failure process of the rock sample, from microcrack initiation to macroscopic fracture network development. BOxin Du also assisted in the initial data processing, organizing the experimental data in an orderly manner for further analysis.Jianxi Ren: Took the lead in manuscript writing and revision. Jianxi Ren synthesized the research findings, experimental data, and analysis results into a coherent and well - structured manuscript. They ensured that the content was presented in a clear and concise manner, adhering to the academic writing style and submission requirements of Scientific Reports. Jianxi Ren also coordinated with the other authors to incorporate their suggestions and feedback during the manuscript revision process, making sure that all significant aspects of the research were properly emphasized. Their excellent writing skills and attention to detail helped to effectively communicate the research significance, methodology, and results to the scientific community, enhancing the manuscript’s readability and impact.Shangxin Feng: Conceived and designed the overall research framework. With profound expertise in petroleum and mining engineering, Shangxin Feng identified the critical research question regarding the rock fragmentation mechanism of polycrystalline diamond compact (PDC) and formulated the hypothesis for the study. They played a pivotal role in the experimental design, determining the combination of mechanical testing and digital image correlation (DIC) monitoring to comprehensively investigate the cutter - rock interaction. Additionally, Shangxin Feng supervised the entire research process, ensuring the experimental procedures were carried out accurately and the data collection was reliable. They also participated in the data analysis, providing valuable insights based on their long - term research experience, and contributed significantly to the interpretation of the results related to the influence of PDC cutter geometry on crack propagation patterns.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, Y., Du, B., Ren, J. et al. Research on the type and expansion mechanism of internal cracks in rocks under the action of PDC. Sci Rep 15, 25136 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09827-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09827-w