Abstract

The novel protein acylation modifications have played a vital role in protein post-translational modifications. However, the functions and effects of the protein acylation modifications in lung adenocarcinoma are still uncertain. Currently, there is still a lack of global identification of acylation modifications in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Therefore, in this study, we detected 10 currently known acylation modifications in lung adenocarcinoma cells by Western blot. We found that the abundance of lysine lactylation (Kla), crotonylation (Kcr) and succinylation (Ksu) is likely higher. Subsequently, we identified the above three modifications together with phosphorylation by global mass spectrometry-based proteomics in lung adenocarcinoma cells. As a result, we got 3110 Kla sites in 1220 lactylated proteins, 16,653 Kcr sites in 4137 crotonylated proteins, 4475 Ksu sites in 1221 succinylated proteins, and 15,254 phosphorylation sites in 4139 phosphorylated proteins. Recent studies have highlighted the role of lactylation modifications in tumor cell resistance to radiation and chemotherapy by affecting homologous recombination. Our subsequent investigations have shown that key factors in the nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, such as Ku70 and Ku80, undergo lactylation modifications. Inhibition of lactylation impairs the efficiency of nonhomologous end joining. In conclusion, our results provide a proteome-wide database to study Kla, Kcr and Ksu and phosphorylation in lung adenocarcinoma, and new insights into the role of acylation modification in lung adenocarcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Protein post-translational modifications (PTMs) follow the process of protein translation and synthesis, referring to covalent bonding or enzyme modification in the amino acid side chain, C-terminal or N-terminal of the protein. Thus, PTMs are critical mechanisms to increase proteome diversity via regulating protein activity, stability, folding, and interaction with other molecules1.

It’s well-known that phosphorylation modification was first found in 1906, which is an enzymatic reaction involving protein kinases that catalyzes the linkage between amino acid residues of proteins and phosphate groups in adenosine triphosphate (ATP)2. Subsequently, other PTMs have been uncovered, ushering in a new era of PTMs. The novel acylation modifications have been progressively discovered and identified in the past 20 years3but their functions still require further research. In 2004, Ran Rosen and colleagues first discovered the succinylation modification during the catalytic activation of homoserine, which refers that succinyl-CoA undergoes esterification with a lysine residue (Lys), forming succinyl-lysine4. Lately, the crotonylation modification of proteins was identified in 20115. Recently, latest studies have authenticated the protein lactate modification in 2019, which is the formation of an ester bond between lactic acid and lysine on proteins through a specific enzymatic reaction6. Besides, PTMs also dynamically regulate protein biological activity7,8 location9 and molecular interaction10 by introducing methyl, acetyl, sugar, carbonyl and other functional groups.

The effects of the novel acylation modifications on lung adenocarcinoma remain unclear. Currently, more studies have covered that abnormal PTMs including acylation modifications can affect the proliferation11 migration12 and apoptosis13 of tumor cells. For instance, the growth14,15,16,17,18 and therapeutic resistance19,20,21 of tumor cells could be affected by lysine lactylation which could regulate metabolic pathways of tumor cells; abnormal phosphorylation can lead to overactivation of tumor cell proliferation22 and metastasis23; and abnormal crotonylation modification may lead to limited DNA damage repair and increased chromatin instability24,25,26,27 further promoting tumor development. The above researchs suggest that acylation modifications may play a crucial role in tumor cells. However, there is currently a lack of global information on acylation modification sites in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Thus, a global profiling of these sites would facilitate a more in-depth exploration of their regulatory mechanisms.

In this study, we detected 10 currently known protein acylation modifications on lung adenocarcinoma cells by Western blot, and our results suggest that the abundance of Ksu, Kcr and Kla may be higher. Then, we conducted a global identification of these three modifications along with phosphorylation. As a result, we got 3110 Kla sites in 1220 lactylated proteins, 16,653 Kcr sites in 4137 crotonylated proteins, 4475 Ksu sites in 1221 succinylated proteins, and 15,254 phosphorylation sites in 4139 phosphorylated proteins. We also found that many key proteins in the nonhomologous end joining pathway can undergo lactylation. Inhibition of lactylation impairs the efficiency of nonhomologous end joining. Our results provide global information to study Kla, Kcr, Ksu and phosphorylation in lung adenocarcinoma.

Results

Global proteomic profiling of lung adenocarcinoma cell

We performed Western blotting with ten lysine-acylated antibodies (Anti-L-Lactyl lysine, Kla; Anti-Succinyllysine, Ksuc; Anti-Crotonyllysine, Kcr; Anti-β-Hydroxybutyryllysine, Kbhb; Anti-Malonyllysine, Kma; Anti-2-Hydroxyisobutyryllysine, Khib; Anti-Propionyllysine, Kpr; Anti-Butyryllysine, Kbu; Anti-Benzoyllysine, Kbz and Anti-Glutaryllysine, Kglu) in A549 and H1299 cell lines, and found that the abundance of Kla, Kcr and Ksu was higher in A549 and H1299 cells (Fig. 1A). To validate these findings and investigate potential metabolic differences, we subsequently performed intracellular lactate quantification assays. Consistent with the lactylation levels, H1299 cells demonstrated higher lactate content than A549 cells (Figure S1). And in Western blot results, it can be concluded that the overall abundance of the three above modifications in A549 and H1299 is roughly equivalent. Thus, considering that A549 is a classic lung adenocarcinoma cell line widely used in various studies, we decided to globally identify the above three modifications in A549 cells. At the same time, since phosphorylation modification is a classical type of modification that has been extensively researched, we simultaneously detected phosphorylation modifications. On the one hand, it can serve as a positive control, while on the other hand, it facilitates subsequent cross-analysis. Ultimately, we conducted comprehensive proteomic analysis of acylation enriched in A549 cells by immunoprecipitation (IP) combined with high-precision and high-resolution mass spectrometry, as illustrated in Fig. 1B. Our results indicate that among 1220 lactylated proteins in A549 cells, there are 3110 Kla sites. Among 4137 butyrylated proteins, there are 16,653 Kcr sites. Among 1221 succinylated proteins, there are 4475 Ksu sites. Among 4139 phosphorylated proteins, there are 15,254 phosphorylation sites (Fig. 1C). Information on protein modification sites can be found in the supplementary materials (Table S1−4). The raw data of these proteomics can be obtained via Pride; see data availability. The above results suggest the widespread distribution of acylation modifications in lung adenocarcinoma cells, providing a basis for further research.

Experimental scheme for global proteomic profiling in A549 and H1299 cells. (A) Expression of 10 acylated modified proteins in whole lysate using immunoblots. (B) Workflow for the global proteomic profiling of Kla, Kcr, Ksu and Phosphorylation in A549 cells. Tryptic peptides were enriched using related pan-antibodies antibody agarose beads, and the enriched peptides were injected into a LC − MS/MS. (C) Number of identified modified sites or proteins in A549 cells.

Subcellular distribution and overlap of Kla, Kcr, Ksu and phosphorylation

In the results of our analysis, it is evident that Kla modifications in A549 cells mainly occur in the nucleus (46.97%) and cytoplasm (33.69%) (Fig. 2A); Kcr modifications are predominantly distributed in the cytoplasm (32.57%) and nucleus (29.3%) (Fig. 2B). Ksu modifications mainly occur in the cytoplasm (36.86%) and mitochondria (26.95%) (Fig. 2C); and phosphorylation modifications are predominantly found in the nucleus (52.3%) and cytoplasm (21.32%) (Fig. 2D). The lysine residues of 305 proteins with Kla modifications are simultaneously crotonylated, succinylated, and phosphorylated. The number of proteins with overlapping modifications is shown in Fig. 2E. Furthermore, to understand the biological functions of proteins concurrently modified by these four modifications, we annotated these proteins through KEGG functional enrichment analysis. The results indicate that these protein modifications are primarily enriched in ribosome-related pathways (Fig. 2F). For instance, P62899 (RPL31) has six amino acid residues, and P49207 (RPL34) has eight amino acid residues where these four modifications occur. The modification sites and types are shown in Fig. 2G. It suggests that ribosome-related proteins may require multiple modifications to coordinate their functions. It is of significant importance for understanding the mechanisms of protein synthesis, cellular biological processes, and the onset of related diseases.

Distribution of Kla, Kcr, Ksu and Phosphorylation proteins in A549 cell. (A) Subcellular distribution of Kla proteins in A549 cell. Subcellular localization of differentially expressed Kla proteins. (B) Subcellular distribution of Kcr proteins in A549 cell. Subcellular localization of differentially expressed Kcr proteins. (C) Subcellular distribution of Ksu proteins in A549 cell. Subcellular localization of differentially expressed Ksu proteins. (D) Subcellular distribution of Phosphorylation proteins in A549 cell. Subcellular localization of differentially expressed Phosphorylation proteins. (E) Overlapping among Kla, Kcr, Ksu and Phosphorylation proteins in the Venn diagram. (F) Enrichment analysis of overlapping proteins in KEGG pathways. (G) Annotation of Kla, Kcr, Ksu and Phosphorylation modified sites in large ribosomal subunit protein eL31 (P62899) and large ribosomal subunit protein eL34 (P49207) in the identified proteins.

Functional analysis of Kla, Kcr, Ksu and phosphorylation site

In order to better understand the biological role of these four modifications, GO enrichment analysis was performed on the proteins of these modifications (Fig. 3). The results of the GO biological process (GOBP) show that proteins involved in mRNA metabolism are more easily modified by lactylation (Fig. 3A), and most lactylated proteins are associated with nuclear luminal components (GOCC). In terms of molecular function (GOMF), RNA binding was significantly enriched in lactylation. In GOBP, crotonylated proteins are associated with RNA processing and mRNA metabolic processes (Fig. 3B). In GOCC, the ribonucleoprotein complex is associated with crotonylation proteins. In the GOMF functional category, RNA-bound structural components may be enriched in crotonylated proteins. Similarly, succinylated proteins are enriched in a variety of biological processes based on GOBP analysis, cotranslational protein targeting to membrane and SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane processes are included (Fig. 3C). Meanwhile, succinylated proteins are mainly related to the structural components of mitochondria and mitochondrial matrix. Moreover, the structural components of ribosomes are mainly enriched in succinylated proteins in GOMF. According to GOBP, phosphorylated proteins are mainly involved in the metabolic process of mRNA (Fig. 3D). Most phosphorylated proteins are related to the nuclear lumen and nuclear plasma component (GOCC) and are mainly involved in enzyme binding (GOMF) and other functions.

Enrichment analysis of identified Kla, Kcr, Ksu and Phosphorylation modified proteins based on GO annotation. (A) Kla, (B) Kcr, (C) Ksu and (D) Phosphorylation proteins identified in A549 were mapped to GO terms. GOBP, gene ontology biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function.

Motif analysis of Kla, Kcr, Ksu and phosphorylation site patterns

To identify potential modification motifs in these modified proteins, amino acid sequence heatmaps were created around Kla, Kcr, Ksu, and Phosphorylation sites (red indicating high frequency, green indicating low frequency) (Fig. 4 A, C, E, G). Additionally, we analyzed the surrounding amino acid sequences using the Motif-X program. According to the results, the conserved sequences around Kla peptides are: xxxxLKGPKxKxxxxxxxxxx, xxxKxxxxxxKxPKxxxxxxx, and xxxxxxxKMPKxxxxxxxxxx (Fig. 4B). The conserved sequences around Kcr peptides are: xxxKxxxPxFKxPxxxxxxPx, KxxxxxxKxPKVxxxxxxxxx, and xxxxxxxxxKxDxDxSxxKx (Fig. 4D); the conserved sequences around Ksu peptides are: xxxKxxxxxxKxPKxxxxxxx, xxxxxxxxxxKxxRxxxxxxx, and xxxxxxxxxKxxxKxxxxxx (Fig. 4F); the conserved sequences around phosphorylation peptides are: xxxxxxSDDDxxx; xxxRxxTPPxxxx, xxxxxxSDDExxx; xxxRPxTPxxxxx, and xxxRxxSPxPxxx; xxxRSxTPxxxxx (Fig. 4H) (where x represents random amino acid residues).

Identification of Kla, Kcr, Ksu and Phosphorylation proteins in A549 cells. (A) Motif analysis of lactylated sites. (B) The three types of conserved motif sites around Kla peptides. (C) Motif analysis of crotonylated sites. (D) The three types of conserved motif sites around Kcr peptides. (E) Motif analysis of succinylated sites. (F) The three types of conserved motif sites around Ksu peptides. (G) Motif analysis of Phosphorylated sites. (H) The three types of conserved motif sites around phosphorylation peptides.

The involvement of protein lactylation in nonhomologous end joining pathway

Lactylation modification, a post-translational modification of significant interest, has been associated with the modulation of tumor resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy through its effects on homologous recombination DNA repair proteins20,21. Nevertheless, the incidence and functional implications of lactylation modifications in non-homologous end-joining proteins in lung adenocarcinoma remain unclear. In this study, our investigation within the KEGG non-homologous end-joining signaling pathway revealed several pivotal proteins, including Ku70/XRCC6, Ku80/XRCC5, Mre11, DNAPKcs, Rad27, XRCC4 and XLF, which exhibit potential lactylation modifications (Fig. 5A). The KEGG pathway map was constructed using the KEGG database (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, https://www.genome.jp/kegg/). To elucidate the lactylation sites, we identified K543 putative lactylation sites within Ku80/XRCC5 (Fig. 5B) and conducted mass spectrometry analyses on this site post lactylation modification (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, multiple lactylation modification sites, specifically at positions K287, K237, K461, K539, K570, K591 and K596, were detected in Ku70/XRCC6 (Fig. 5C), with mass spectrometry verification performed on K570 site following lactylation modification (Fig. 5E).

(A) Non-homologous end joining KEGG pathway map in the lactylated modification omics of the A549 cell line. (B) Schematic depicting Ku80/XRCC5 key domains and lysine site which was identified to be possibly lactylated by MS were pointed out. (C) Schematic depicting Ku70/XRCC6 key domains and several lysine sites which were identified to be possibly lactylated by MS were pointed out. (D) Illustration of Ku80/XRCC5 K543 lactylation identified by MS. (E) Illustration of Ku70/XRCC6 K570 lactylation identified by MS.

Validation of lactylation on Ku70 and Ku80, and inhibiting lactylation can suppress NHEJ efficiency

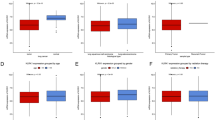

To confirm the presence of lactylation modifications on Ku70 and Ku80, we conducted immunoprecipitation experiments in A549 cells followed by detection using antibodies against Anti-L-Lactyl Lysine. The results demonstrated the detectable occurrence of lactylation modifications on both Ku70 and Ku80 (Fig. 6A). Moreover, upon treatment of A549 cells with the lactylation-inducing agent NALA, an upregulation of lactylation modifications on Ku70 and Ku80 was observed (Fig. 6B). Subsequently, treatment of A549 cells with lactylation inhibitors Oxamate and 2-DG resulted in a reduction in overall lactylation modifications (Fig. 6C). The analysis of lactylation modifications on Ku70 and Ku80 revealed a notable decrease under inhibitor treatment (Fig. 6D), This further verified that Ku70 and Ku80 can be lactylation modificated. Additionally, flow cytometry results indicated a decrease in the efficiency of non-homologous end-joining repair under the influence of these inhibitors, suggesting a regulatory role of lactylation modifications in non-homologous end-joining (Fig. 6E). Through clone formation assays, it was observed that the sensitivity of A549 cells to radiotherapy was enhanced following the inhibition of lactylation modifications with Oxamate and 2-DG (Fig. 6F).

(A) Detecting lactylation of Ku70, Ku80 by Western blots using co-immunoprecipitation (coIP) sample as indicated. (B) Detecting lactylation of Ku70, Ku80 in cells treated with NALA as indicated by Western blot using co-immunoprecipitation (coIP) sample as indicated. (C) Detecting lactylation of Ku70, Ku80 in cells treated with Oxamate or 2-DG as indicated by Western blot. (D) Detecting lactylation of Ku70, Ku80 in cells treated with Oxamate as indicated by Western blot using co-immunoprecipitation (coIP) sample as indicated. (E) Treated with Oxamate or 2-DG significantly affected NHEJ. (F) After treatment with Oxamate or 2-DG, clone formation experiments were conducted to assess the survival rate of A549 cells following different doses of radiotherapy.

Discussion

The novel acylation modification, as a new type of PTMs, has been globally identified in different species and tissues in recent studies28,29,30. Based on current researches, the quantity of identified sites for acylation modifications remains limited. For instance, in normal human lung tissues, only slightly over 600 lactylation sites have been identified31. In another study on Kupffer cells, only slightly over 200 lactylation sites were identified32. In contrast, we have identified over 3000 lactylation sites in lung adenocarcinoma cells. These differences may arise from variations in the precision of omics instrumentation and enrichment techniques, but they could also be due to the presence of the Warburg effect in tumor cells, where lactate accumulation leads to a higher abundance of lactylation modifications in tumor cells. Similarly, another study identified over 2000 lactylation sites in liver cancer cells, suggesting that tumor cells may exhibit a higher abundance of lactylation modifications33. Previous studies have shown that succinylation modification is closely associated with mitochondrial function and metabolism34. Consistent with that, the succinylated proteins we identified are primarily localized in mitochondria (Fig. 2C). While previous literature has investigated succinylation sites in lung adenocarcinoma, encompassing slightly over 2000 sites35our omics identification revealed over 4000 succinylation sites, offering additional information for further investigation. The number of crotonylation sites we identified in lung adenocarcinoma cells is almost equivalent to phosphorylation, which suggests that crotonylation may be an important modification involved in a wide range of biological processes.

The Warburg effect in tumor cells is known to accumulate lactic acid. Therefore, it is speculated that lactylation modifications may play an important role in tumor cells. It has been reported that lactylation modifications can promote homologous recombination of tumor cells20,21. However, the function of lactylation modifications in non-homologous end-joining in lung adenocarcinoma tumor cells remains unclear. Thus, in this study, non-homologous end-joining key proteins Ku80/XRCC5 and Ku70/XRCC6 in A549 cells were listed, and their lactylation modifications sites were identified by mass spectrometry. We found that K543 in Ku80/XRCC5 (Fig. 5B) and K287, K2367, K461, K539, K570, K591, and K596 in Ku70/XRCC6 can be lactylated (Fig. 5C). Then, we verified the existence of lactylation modifications of Ku70 and Ku80 by coIP experiment (Fig. 6A-D). Subsequently, after treatment with Oxamate lactate inhibitors, we found that the repair efficiency of non-homologous end-joining of A549 cells was reduced and the radiotherapy sensitivity of the cells was enhanced, indicating that lactylation modifications promoted non-homologous end-joining in lung adenocarcinoma cells.

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of protein lactylation, crotonylation, succinylation, and phosphorylation in lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. We observed relatively high abundance of Kla, Kcr, and Ksu in A549 cells through Western blot experiments (Fig. 1A), the limitations of pan-antibody detection suggest that lower abundance of these modifications does not necessarily imply their absence. Therefore, through proteomic analysis, we discovered 1220 lactylated proteins in A549 cells with 3110 identified Kla sites; 4137 crotonylated proteins with 16,653 Kcr sites; 1221 succinylated proteins containing 4475 Ksu sites; and 4139 phosphorylated proteins with 15,254 phosphorylation sites (Fig. 1C). In terms of subcellular localization, we found for the first time that Kla in A549 cells predominantly occurs in the nucleus (46.97%) (Fig. 2A), implying that Kla modifications may primarily be involved in transcriptional regulation and histone modification. On the other hand, Ksu modifications are more enriched in the cytoplasm (36.86%) and mitochondria (26.95%) (Fig. 2C), indicating their potential involvement in energy metabolism processes. These findings indicate the extensive presence of acylation modifications in lung adenocarcinoma cells, laying a basis for future investigations.

In conclusion, our study on Kla, Kcr, Ksu, and Phosphorylation modifications in the lung adenocarcinoma A549 cell line provides a proteome-wide perspective to supplement future research on lung adenocarcinoma.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and sample preparation

Human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cell and H1299 cell line were purchased from ATCC and cultured in DMEM/F12 or RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The cells were harvested at 90% confluence by scraping. The cells were washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Cell pellets were immediately stored at −80 °C.

Western blot

Cells pellets were lysed in a RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, China) with Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Cell lysates were denatured at 100 °C for 10 min. 10% and 12% SDS-PAGE gel were used to separate proteins. Proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking membranes in 5% milk at room temperature for 1 h. Primary antibodies against Anti-L-Lactyl Lysine, Anti-Succinyllysine, Anti-Crotonyllysine, Anti-β-Hydroxybutyryllysine, Anti-Malonyllysine, Anti-2-Hydroxyisobutyryllysine, Anti-Propionyllysine, Anti-Butyryllysine, Anti-Benzoyllysine and Anti-Glutaryllysine (1 : 1000, PTM bio) were incubated with membranes at 4 °C overnight. Membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies) at room temperature for 1 h. Proteins were finally visualized by ECL system (Beyotime) and then captured by ChemiDoc Imaging System (BIO-RAD).

LC-MS/MS analysis

The enrichment of modified peptides and subsequent mass spectrometry (MS) analysis were performed by PTM Bio (Hangzhou). Briefly, the tryptic peptides were dissolved in solvent A (0.1% formic acid, 2% acetonitrile in water), directly loaded onto a home-made reversed-phase analytical column (25-cm length, 75/100 µm i.d.). Peptides were separated with a gradient from 6 to 24% in solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) over 70 min, 24–35% in 14 min and climbing to 80% in 3 min then holding at 80% for the last 3 min, all at a constant flow rate of 450 nL/min on a nanoElute UHPLC system (Bruker Daltonics). The peptides were subjected to capillary source followed by the timsTOF Pro (Bruker Daltonics) mass spectrometry. The electrospray voltage applied was 1.60 kV. Precursors and fragments were analyzed at the TOF detector, with a MS/MS scan range from 100 to 1700 m/z. The timsTOF Pro was operated in parallel accumulation serial fragmentation (PASEF) mode. Precursors with charge states 0 to 5 were selected for fragmentation, and 10 PASEF-MS/MS scans were acquired per cycle. The dynamic exclusion was set to 30s.

GO annotation

GO annotation is to annotate and analyze the identified proteins with eggnog-mapper software (v2.0). The software is based on the EggNOG database. The latest version is the 5th edition, covering 5,090 organisms and 2502 virus genome-wide coding protein sequences. Extracting the GO ID from the results of each protein note, and then classified the protein according to Cellular Component, Molecular Function and Biological Process.

Subcellular localization

The proteins in the cells of eukaryotic tissues are located on various elements in the cell based on the difference of the membrane structure that they bind to. The main subcellular locations of eukaryotic cells include: extracellular, cytoplasm, nucleus, mitochondrion, Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum, peroxisome, vacuole, cytoskeleton, nucleoplasm, nuclear matrix and ribosome. Thus, we annotated the subcellular structure of the protein using WoLF PSORT software.

Immunoprecipitation

For immunoprecipitation analysis, cells were plated in 100-mm plates and then lysed in Western blot and immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (Beyotime). Whole-cell lysates were incubated with Protein A/G magnetic beads (GE) conjugated with anti-Ku70 (Proteintech) or Ku80 (Proteintech) at 4 °C overnight. Following extensive washing in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), bound proteins were recovered by boiling the beads in 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample loading buffer.

NHEJ reporter assays

Briefly, we used EJ5-GFP (Addgene: 44026) for total NHEJ. I-SceI (Addgene: 26477) was applied to induce DSBs at I-SceI sites in the plasmid construct. Oxamate or 2-DG treatment was performed on 12 h in advance. The plasmids were transfected into cells by Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by incubation in 37 °C preheated 10% fetal bovine serum medium for 48 h. After finished incubation, cells were collected for GFP detection by flow cytometry.

Clonogenic assay

Single-cell suspensions were inoculated into 6-well plates (500–1000 cells per well) and treated with IR (0, 2, 4, 6, 8 Gy) until cell adherence. After colony formation (~ 7–10 days), the plates were rinsed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet. Colonies containing more than 50 cells were counted.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Walsh, C. T., Garneau-Tsodikova, S. & Gatto, G. J. Jr. Protein posttranslational modifications: the chemistry of proteome diversifications. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 44 (45), 7342–7372 (2005).

Tarrant, M. K. & Cole, P. A. The chemical biology of protein phosphorylation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 797–825 (2009).

Shang, S., Liu, J. & Hua, F. Protein acylation: mechanisms, biological functions and therapeutic targets. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7 (1), 396 (2022).

Rosen, R. et al. Probing the active site of Homoserine trans-succinylase. FEBS Lett. 577 (3), 386–392 (2004).

Tan, M. et al. Identification of 67 histone marks and histone lysine crotonylation as a new type of histone modification. Cell 146 (6), 1016–1028 (2011).

Zhang, D. et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 574 (7779), 575–580 (2019).

Lee, J. M., Hammaren, H. M., Savitski, M. M. & Baek, S. H. Control of protein stability by post-translational modifications. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 201 (2023).

Yu, F., Wu, Y. & Xie, Q. Precise protein post-translational modifications modulate ABI5 activity. Trends Plant. Sci. 20 (9), 569–575 (2015).

Tang, J. et al. Cancer cells escape p53’s tumor suppression through ablation of ZDHHC1-mediated p53 palmitoylation. Oncogene 40 (35), 5416–5426 (2021).

Wang, S., Osgood, A. O. & Chatterjee, A. Uncovering post-translational modification-associated protein-protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 74, 102352 (2022).

Huang, H. et al. The roles of post-translational modifications and coactivators of STAT6 signaling in tumor growth and progression. Future Med. Chem. 12 (21), 1945–1960 (2020).

Wattanathamsan, O. & Pongrakhananon, V. Post-translational modifications of tubulin: their role in cancers and the regulation of signaling molecules. Cancer Gene Ther. 30 (4), 521–528 (2023).

Leon, L., Jeannin, J. F. & Bettaieb, A. Post-translational modifications induced by nitric oxide (NO): implication in cancer cells apoptosis. Nitric Oxide. 19 (2), 77–83 (2008).

Ju, J. et al. The alanyl-tRNA synthetase AARS1 moonlights as a lactyltransferase to promote YAP signaling in gastric cancer. J Clin. Invest 134 (10):e174587. (2024).

Xie, B. et al. KAT8-catalyzed lactylation promotes eEF1A2-mediated protein synthesis and colorectal carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 121(8), e2314128121 (2024).

Sun, L. et al. Lactylation of METTL16 promotes Cuproptosis via m(6)A-modification on FDX1 mRNA in gastric cancer. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 6523 (2023).

Jin, J. et al. SIRT3-dependent delactylation of Cyclin E2 prevents hepatocellular carcinoma growth. EMBO Rep. 24 (5), e56052 (2023).

Zong, Z. et al. Alanyl-tRNA synthetase, AARS1, is a lactate sensor and lactyltransferase that lactylates p53 and contributes to tumorigenesis. Cell 187(10), 2375-2392.e33 (2024).

Li, G. et al. Glycometabolic reprogramming-induced XRCC1 lactylation confers therapeutic resistance in ALDH1A3-overexpressing glioblastoma. Cell. Metab. 36(8), 1696-1710.e10 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. NBS1 lactylation is required for efficient DNA repair and chemotherapy resistance. Nature 631 (8021), 663–669 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Metabolic regulation of homologous recombination repair by MRE11 lactylation. Cell 187 (2), 294–311 (2024). e21.

Guo, X. et al. Site-specific proteasome phosphorylation controls cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Nat. Cell. Biol. 18 (2), 202–212 (2016).

Cai, Z. et al. Phosphorylation of PDHA by AMPK drives TCA cycle to promote Cancer metastasis. Mol. Cell. 80 (2), 263–278 (2020). e7.

Yu, H. et al. Global Crotonylome reveals CDYL-regulated RPA1 crotonylation in homologous recombination-mediated DNA repair. Sci. Adv. 6 (11), eaay4697 (2020).

Abu-Zhayia, E. R. et al. CDYL1-dependent decrease in lysine crotonylation at DNA double-strand break sites functionally uncouples transcriptional Silencing and repair. Mol. Cell. 82(10), 1940-1955.e7 (2022).

Hao, S. et al. Dynamic switching of crotonylation to ubiquitination of H2A at lysine 119 attenuates transcription-replication conflicts caused by replication stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 50 (17), 9873–9892 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Lysine crotonylation: an emerging player in DNA damage response. Biomolecules 12 (10) (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Global involvement of lysine crotonylation in protein modification and transcription regulation in rice. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 17 (10), 1922–1936 (2018).

Meng, X. et al. Comprehensive analysis of the lysine succinylome and protein Co-modifications in developing rice seeds. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 18 (12), 2359–2372 (2019).

Zhu, J., Guo, W. & Lan, Y. Global analysis of lysine lactylation of germinated seeds in wheat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 22 (2023).

Yang, Y. H., Wang, Q. C., Kong, J., Yang, J. T. & Liu, J. F. Global profiling of lysine lactylation in human lungs. Proteomics 23(15), e2200437 (2023).

Sung, E. et al. Global profiling of lysine acetylation and lactylation in Kupffer cells. J. Proteome Res. 22 (12), 3683–3691 (2023).

Hong, H. et al. Global profiling of protein lysine lactylation and potential target modified protein analysis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Proteomics 23(9), e2200432 (2023).

Yang, Y. & Gibson, G. E. Succinylation links metabolism to protein functions. Neurochem Res. 44 (10), 2346–2359 (2019).

Wu, J. et al. Proteomic quantification of lysine acetylation and succinylation profile alterations in lung adenocarcinomas of Non-Smoking females. Yonago Acta Med. 65 (2), 132–147 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members of the Radiation Oncology Center who participated in this article.

Funding

We acknowledge the funding support from the Chongqing Science and Health Joint Medical Research Project (2023GGXM002, 2023GDRC005), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing City (cstc2021jcyj-msxmX0022, NSTB2022NSCQMSX0272), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32100591, 82172374) and Chongqing Talent Plan (CQYC20210203119).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H. and T.L. co-wrote the manuscript, J.H., T.L., Z.Z., H.Y., Z.L., L.Z., N.L., Y.H., S.Z., E.M., Y.T., M.W. and Y.Z. conducted the experiments and/or analysed the data. W.Z. and Y.W. conceived this project.All authors have approved this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have approved the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, J., Lai, T., Zhou, Z. et al. Multiomics profiling reveals the involvement of protein lactylation in nonhomologous end joining pathway conferring radioresistance in lung adenocarcinoma cell. Sci Rep 15, 24651 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09937-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09937-5