Abstract

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is a rare occlusive cerebrovascular disease, and its pathological mechanism remains unclear at present. The abnormal vascular remodeling may be involved in vascular endothelial cells. In this study, RNA seq was performed on the superficial temporal arteries of 10 patients with MMD. Integrated analysis was conducted by combining validation set with training set. Key genes were identified through differential analysis and WGCNA. The functions of potential biomarkers were explored by methods such as correlation analysis, KEGG analysis, PPI network, and tube formation experiments. Integrated analysis of three cohorts (43 MMD vs. 26 controls) identified 19 shared DEGs, including upregulated KRT8/KRT18 and downregulated NT5C2 (P < 0.001). Enrichment revealed dysregulation in circadian rhythm, calcium signaling, and metabolic pathways (P < 0.05). Immune infiltration showed elevated pro-inflammatory cells (neutrophils, M1 macrophages) and reduced Tregs/NK cells (P < 0.05). Machine learning (SVM-RFE, Boruta, LASSO) prioritized KRT8 as diagnostic markers (AUC > 0.96). KRT8 overexpression enhanced angiogenesis in HBMECs (1.5-fold tube formation, P < 0.01). This omics approach delineates MMD’s molecular interplay between inflammation, metabolism, and vascular remodeling. KRT8 may promote vascular remodeling in MMD by regulating the tube-forming ability of endothelial cells. This could be a highlight of therapeutic targets for MMD and shed light on the mechanism research of MMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is a rare cerebrovascular disease characterized by stenosis or occlusion of the internal carotid arteries and pathologic hyperplasia of the intracranial blood vessels to form collateral circulation. The collateral circulation appears as “puff of smoke” blood vessels on DSA1,2. This abnormal vascular remodeling can lead to recurrent ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, common in children and young adults, causing significant neurologic disability and even death3, causing significant neurologic disability and even death. There are no effective pharmacologic treatments for MMD, and the specific etiology of MMD remains unclear. Surgical revascularization techniques (e.g., superficial temporal artery anastomosis or vascular bypass grafting) currently dominate the treatment of MMD4, However, these interventions do not halt disease progression in diffuse vascular disease and carry a high risk of perioperative complications2. Critically, the molecular mechanisms driving MMD pathogenesis remain elusive, and the lack of reliable biomarkers or targeted therapies underscores the urgent need for mechanistic insights.

Recent studies highlight the interplay between genetic predisposition and immune dysregulation in MMD. The whole exome sequencing (WES) has identified susceptibility genes (e.g., RNF213) linked to angiogenesis and inflammatory pathways5,7, yet limitations persist small sample sizes, incomplete functional validation, and a paucity of data on autologous vascular tissues hinder translational progress.

Immune dysregulation is central to MMD8,9, driving pathological vascular remodeling through synergistic interactions between immune cells, cytokines, and molecular pathways. Initially, T-cell dysfunction is a key factor10. Defective regulatory T cells (Treg) are unable to maintain immune tolerance, whereas helper T cells (Th17) can activate vascular endothelial cells (EC)11 and smooth muscle cells (SMC)12 by secretion of IL-17, thereby exacerbating vascular inflammation10,13,14. Concurrently, M2 macrophages exacerbate intimal hyperplasia via TNF-α/IL-6-mediated smooth muscle proliferation and CD163-dependent vascular remodeling15,18. At the molecular level, the abnormal overexpression of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and neovascularization19. This occurs through the activation of downstream signaling pathways and the upregulation of pro-angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)20. However, an imbalance in this regulatory network can trigger numerous harmful effects, including excessive immune cell infiltration, exacerbated oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation. The dysregulation of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signaling induces endothelial damage, while aberrant endothelial proliferation and fragile neovascularization increase the risk of ischemia and hemorrhage. Thus, immune infiltration acts as a key driver in the progression of vasculopathy in MMD, operating through a self-reinforcing positive feedback loop.

keratin 8 (KRT8) is a type II keratin (KRT) that forms intermediate filaments, which are fundamental cytoskeletal components for maintaining cell morphology21,22. It is known that KRT plays a significant role in promoting various diseases by influencing endothelial cells. In addition, Harald et al. discovered a large amount of keratin phosphorylation in atherosclerotic lesions, which might be related to cellular stress responses and apoptosis23. However, they only conducted observational studies and did not explore the pathological mechanism of keratin in blood vessels. This suggests that KRT8 may be closely associated with vascular remodeling in MMD, the specific role of keratin remains unclear.

In this study, we utilized MMD-related transcriptome data from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (GSE189993 and GSE249254) and self-tested vascular tissue samples from 10 cases of MMD. By integrating these datasets with machine learning algorithms, we identified key signature genes and validated their diagnostic performance using additional cohorts (GSE249254 and Teatdata). Our analysis revealed 19 shared differentially expressed genes significantly enriched in pathways. Among these, KRT8, KRT18, and NT5C2 emerged as robust diagnostic markers. To further evaluate the predictive utility of these markers, we constructed a column-line graph model, which exhibited strong predictive performance, as confirmed by calibration curves and ROC analysis. Additionally, we built a protein-protein interaction network using the STRING database and screened for small-molecule drugs associated with the characterized genes using DrugBank and DGIdb. This study provides novel insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying MMD, and highlights promising drug targets through the integration of multi-omics data and machine learning approaches Materials and methods.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition and processing

We searched “moyamoya disease” as the keyword in the GEO24 database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and set the species information as Homo sapiens. We included datasets with sample size > 6 and obtained two microarray datasets (GSE189993 and GSE249254) from the GEO database. The enrolled datasets had the gene expression profiles of 27 MMD patients and 17 healthy controls. The data file of GSE189993 included the expression profile data of 32 participants (21 MMD patients and 11 non-MMD patients), and GSE249254 contained the gene expression data of 12 participants (6 MMD patients and 6 non-MMD patients). Additionally, we included 10 MMD vascular tissue samples and 3 control samples (epilepsy) from our TestData. The gene expression profile data was measured from the samples of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) of the MMD patients and superficial temporal artery (STA) of controls. Batch effects were corrected for using the SVA software package (v1.62.0) with ComBat adjustment for age and gender covariates. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to visualize pre- and post-correction batch effects, retaining components that explained > 80% of the cumulative variance. Protein-coding genes were filtered according to the GENCODE v44 annotation and genes with zero expression in > 80% of the samples were excluded to minimize error.

Participants and sample Preparation

In this study, all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The RNA seq study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China (I-24PJ1573). The experiment was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all the enrolled participants. Since this was an observational study, the patients underwent the diagnostic procedures and continued treatment at Peking Union Medical College Hospital. We anonymized the data to protect the personal identities of the participants.

After detailed consultation and physical examination, a total of 10 Chinese and Han individuals underwent digital subtraction angiography (DSA) to check for MMD25 at the Department of Neurosurgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital from November 1, 2023, to January 1, 2025. Detailed consultations and physical examinations were performed on patients to ensure that they did not have any underlying diseases, such as hyperthyroidism, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, which could affect the results of the study. We performed RNA-seq of 10 MCA specimens resected during bypass surgery of 10 MMD patients and 3 STA specimens obtained during the craniotomy of 3 non-MMD patients. Here, the samples obtained from surgery was transferred to store at 80℃ and performed with RNA extraction. (Fig. 1)

A total of 37 MMD and 20 HC participants were included in this study and divided into three groups: Training set (21 MMD, 11 HC), Validation set (6 MMD, 6 HC), and Self-test data (10 MMD, 3 HC). The gene data from vascular samples of the participants were analyzed for differential expression, immune infiltration, WGCNA, etc. Through machine learning, KRT8 was selected as a candidate gene for in vitro experiments. Tube formation assay was conducted using a KRT8 overexpression MMD cell model. The results suggest that overexpression of KRT8 in MMD promotes the migration and angiogenic function of endothelial cells, thereby driving the pathological development of MMD.

Participants and sample data process

We processed GSE189993 data using the R package ArrayExpress26(Version 1.62.0, http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/2.9/bioc/html/limma.html) for background correction and normalization of the expression matrix followed by gene annotation. We downloaded the count data and normalized the raw expression data to log(x + 1) for GSE249254 and TestData. We extracted the ‘protein coding’ genes and removed the genes that had a zero expression in more than 80% of the samples.

Differential expression analysis

We performed differential expression analysis on GSE189993, GSE249254 and TestData. Classical Bayesian and linear regression methods were used to analyze gene expression differences between MMD and control samples using the R package limma27. The threshold for significant differential expression was set at |log2FC| > 0.263 and p < 0.0528. We identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and visualized the results using volcano plots and heat maps.

Venn analysis—identification of common DEGs

We used the R package ggvenn(Version 0.1.10, https://mirrors.pku.edu.cn/CRAN/web/packages/ggvenn/index.html) to identify shared differential genes by taking the intersection of differential up and down-regulated genes in GSE189993, GSE249254, and TestData. The p-values for the differences of shared differential genes between disease and control samples were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test in each of the three datasets, and the results were presented by plotting box-and-line plots using the R package ggplot2(Version 3.5.0, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html.

Enrichment analysis

We performed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)29 using TestData. Genes were ranked based on Log2FC values, and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomic Pathways)30 enrichment analysis was conducted using the R package clusterProfiler31 with the MSigDB32 database (c2.cp.kegg.v2023.1.Hs.symbols.gmt) as the background. The threshold for significant enrichment was set as an adjusted P-value < 0.05. Additionally, we performed GO (Gene Ontology) and KEGG enrichment analyses on the common DEGs to identify their potential biological functions and pathways.

Immune infiltration analysis

To explore the immune infiltration landscape in MMD, we used the R package GSVA33 to perform ssGSEA enrichment analysis on 28 immune cell types. We calculated the immune cell infiltration proportions for each sample in GSE189993, GSE249254, and TestData. We then used Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to compare the differences in immune cell infiltration between disease and control samples and visualized the results using heatmaps and boxplots. Additionally, we calculated the Spearman correlation between immune cells and common DEGs, with a significance threshold of P < 0.05.

Machine learning for candidate feature gene selection

Feature selection

Based on the GSE189993 expression matrix (with a large sample size), three methods, SVM-RFE34, Boruta35, and Lasso regression36, were used for feature selection of the above shared differential genes: the e1071 package was utilized for SVM-RFE feature selection. Next, the Boruta algorithm was used to utilize the R package Boruta algorithm provided to filter out the most useful features for model prediction. Finally, the R package glmnet was utilized to set family = “binomial” for lasso regression, and 10-fold cross-validation was used for screening. The genes screened by the three machine learning algorithms were taken as intersections and the intersected genes were used as candidate feature genes.

Validation and performance evaluation

We further validated the expression levels of the candidate feature genes in GSE189993, GSE249254, and the TestData using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. We visualized the results using violin plots. Genes that showed consistent differential expression across all three datasets were selected as final feature genes. We then used the R package pROC37 to plot ROC curves and evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of these feature genes.

To explore the predictive potential of the feature genes, we constructed a nomogram using the R package rms based on the training set (GSE189993). We also plotted decision curve analysis (DCA) and calibration curves to evaluate the accuracy of the nomogram. Finally, we validated the nomogram using ROC curves in the training set (GSE189993), validation set (GSE249254), and the TestData.

Selection of KRT8 and plasmid construction and transfection

Combining the above results we chose KRT8 as the target gene for the following reasons KRT8 expression was significantly up-regulated in GSE189993, GSE249254 and TestData (log2FC > 1.5, P < 0.001), and the difference was the most significant among the 19 shared differentially differentiated genes. It was classified as a key diagnostic marker in both the LASSO regression (λ = 0.02 with the highest retained weight was the highest) and SVM-RFE (the number of features was 3 at the lowest 10-fold cross-validation error) both classified it as a key diagnostic; it has been demonstrated that KRT family members are involved in vascular remodeling by regulating cytoskeletal and inflammatory pathways, and combining with the above rationale we used KRT8 as a target gene. To verify the effects of hub genes in vitro, we using the pcDNA3.1(+) vector constructed KRT8 overexpression plasmid. Specific primers containing BmtI and KpnI restriction sites were designed to amplify the KRT8 coding sequence (CDS). PCR products were purified, and the vector was linearized by double digestion (Bmt I/Kpn I). The insert and vector were ligated using T4 DNA ligase (16 °C, overnight). Positive clones were selected via colony PCR and validated by sequencing. Plasmid DNA was extracted using a commercial kit. Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) were cultured in ECM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. At 80% confluency, cells were transfected with 2 µg of oe-KRT8 or empty vector (oe-vector) using a lipid-based transfection reagent. Transfected cells serve as controls. Transfection efficiency was confirmed by qPCR 48 h post-transfection, with GAPDH as the internal reference.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted 48 h after cell transfection. Cells were first harvested by trypsinization and collected by centrifugation. After discarding the supernatant, 0.5 mL of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) was added to each sample, followed by repeated pipetting to ensure complete lysis. The lysates were transferred to 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and allowed to stand at room temperature for 5 min. Then, 0.1 mL of chloroform (one-fifth the volume of TRIzol) was added, and the tubes were shaken vigorously for 15 s and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The aqueous phase was carefully collected without disturbing the interphase and mixed with an equal volume of isopropanol (approximately 200 µL) by vigorous shaking. The mixture was incubated at −20 °C for 30 min to precipitate RNA, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the RNA pellet was washed with 1 mL of 75% ethanol prepared in DEPC-treated water. After centrifugation at 7,500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was air-dried for 5–10 min at room temperature. Finally, the RNA was dissolved in 10 µL of DEPC-treated water and thoroughly mixed. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Reverse transcription was performed using the iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 2 µL of total RNA was used as the template in a 20 µL reaction system containing 5× iScript reaction mix, iScript reverse transcriptase, and nuclease-free water. The reaction was carried out in a thermal cycler with the following program: 25 °C for 5 min, 46 °C for 20 min, and 95 °C for 1 min. The resulting cDNA was stored at −70 °C for later use.

qPCR was performed using TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ (Tli RNaseH Plus; Takara, Japan) in a total reaction volume of 20 µL. Each reaction contained 2 µL of cDNA template, forward and reverse primers (0.4 µL each), 0.4 µL of 50× ROX reference dye, and nuclease-free water, with the remaining volume made up by the 2× TB Green Premix. All reactions were prepared on ice and loaded into PCR tubes, sealed, and placed in the real-time PCR instrument. Amplification was performed according to the manufacturer’s cycling conditions. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2^−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as the internal reference gene.

The primer sequences used in this study were as follows:

KRT8 forward: 5’-CAGAAGTCCTACAAGGTGTCCA-3’, reverse: 5’-CTCTGGTTGACCGTAACTGCG-3’;

GAPDH forward: 5’-GCAGGAGTACGATGAGTCCG-3’, reverse: 5’-ACGCAGCTCAGTAACAGTCC-3’.

Tube formation assay

The angiogenic capacity of HBMECs was assessed using a Matrigel-based tube formation assay. Matrigel matrix (Beyotime, China) was thawed overnight at 4 °C. Each well of a 96-well plate was coated with 50 µL Matrigel and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h to allow polymerization. Transfected HBMECs (1.5 × 10^4 cells/well) were seeded onto the pre-coated Matrigel and cultured for 12 h at 37 °C under 5% CO₂. Tube formation was monitored every 2 h using an inverted microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE Ts2, Japan).

After 6 h, three non-overlapping fields per well were randomly selected and images were captured at 100× magnification. All images were analyzed using the Angiogenesis Analyzer plugin for ImageJ (NIH, USA). Prior to analysis, images were converted to 8-bit grayscale and subjected to threshold adjustment using a consistent setting across all samples to distinguish tubular structures from background. Tube branches were defined as nodes connected to three or more tubular elements, and total tube length was calculated as the sum of the lengths of all interconnected tubes per field (measured in µm). Experiments were conducted in triplicate with three independent biological replicates. Data were analyzed and graphed using Graphpad Prism 9 (Version 9.4.0) and collated using Adobe Illustrator (Version 26.3.1). All data were expressed as mean ± SD, and statistical differences between groups were tested by one-way ANOVA, with P values less than 0.05 considered significant.

Transwell migration assay

The migratory capacity of KRT8-overexpressing HBMEC cells was assessed using a Transwell chamber system (8-µm pore, Corning). HBMEC cells (Shanghai Zhong Qiao Xin Zhou Biotechnology) were cultured in ECM medium containing 5% FBS, 1% ECGS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO₂). Upon reaching 90% confluence, cells were trypsinized, centrifuged (150 ×g, 5 min), and resuspended in serum-free medium. Three experimental groups were established: (1) Control (untransfected cells), (2) oe-Vector (transfected with empty pcDNA3.1 plasmid), and (3) oe-KRT8 (transfected with KRT8 overexpression plasmid). Cells (2.5 × 10⁵ cells/mL) were seeded into the upper chamber, while the lower chamber contained DMEM with 10% FBS as a chemoattractant. After 24 h incubation, non-migratory cells were removed, and migrated cells were fixed with 4% methanol, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and imaged under an inverted microscope (Nikon ECLIPSETs2) at 200× magnification. The data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 9 software (version 9.4.0) for one-way ANOVA, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). The significance difference criterion was * P < 0.05, and the data visualization was completed using Adobe Illustrator 2022 (version 26.3.0). All experiments were repeated three times to verify reproducibility.

Protein-Protein interaction (PPI) network construction

We used the STRING database to construct a PPI network for the 19 common DEGs. The confidence level for the interactions was set at 0.15.

Small molecule drug prediction

We used the Drugbank38 and DGIdb39 databases to identify small molecule drugs associated with the feature genes. We then used Cytoscape40 to visualize the gene-drug interaction network.

Construction of a multi-factor regulatory network

Gene expression is regulated at the level of transcription factors. Therefore, the combination of the transcription factor database (hTFtarget)41 to analyze the transcription factors regulating the characterized genes. At the same time, miRNAs regulating the characterized genes were predicted by the database of starBase42 database, and miRNAs with “TDMDScore” > 1 were screened. then Cystoscape software was used to construct the TF-mRNA-miRNA network.

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

All statistical analyses were conducted using R language (version 4.2.2), and p < 0.05 was statistically significant. The comparison between two groups was performed with Wilcox test and the comparison among three and more groups was performed using Kruskal test. Data from the tube formation and Transwell migration assays were analyzed and visualized using GraphPad Prism 9 (Version 9.4.0, GraphPad Software, USA). Figures were assembled using Adobe Illustrator 2022 (Version 26.3.0, Adobe Systems, USA). All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Differential expression analysis and shared differential gene screening

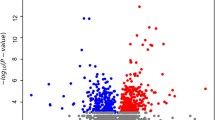

We identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between MMD patients and healthy controls by integrating transcriptomic data from GSE189993 (27 MMD cases vs. 17 controls), GSE249254 (6 MMD cases vs. 6 controls), and an internal validation cohort (10 MMD cases vs. 3 controls). The threshold for difference analysis was set at |log2FC|>0.263 and P < 0.05. 2,449, 1,819, and 6,195 DEGs were identified in the three data sets. The volcano plot (Fig. 2A) showed the distribution of differential genes (blue for down-regulation, red for up-regulation, black horizontal line for P = 0.05 and vertical line for log2FC = 0.263). The heat map (Fig. 2B) further showed the clustering pattern of gene expression.

(A) Differential gene volcano plot. Blue represents down-regulated genes, red represents up-regulated genes, black horizontal line indicates p Value = 0.05, vertical line indicates |log2FC|=0.263. (B) Differential gene heat map. The red group represents MMD group, and the blue group represents the control group. Red indicates up-regulation, and blue indicates down-regulation. The deeper the color, the more significant the difference. (C) Venn analysis-identification of shared differential genes. Left: blue represents the up-regulated genes in the self-test set, red represents the up-regulated genes in GSE249524, and purple represents the up-regulated genes in GSE189993. Right: blue represents the down-regulated genes in the self-test set, red represents the down-regulated genes in GSE249524, and purple represents the down-regulated genes in GSE189993. (D) Shared differential gene box plots. The blue represents the control group and the red represents the MMD group. The horizontal axis shows the differentially expressed genes and the vertical axis shows the gene expression levels. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

A total of 19 common DEGs (5 up-regulated and 14 down-regulated) were identified as candidate genes by Venn analysis (Fig. 2C). Among them, KRT8, KRT18 (up-regulated) and NT5C2 (down-regulated) showed consistent expression trends and the most significant differences in the three datasets (P < 0.001). The median expression level of KRT8 was significantly higher in the MMD group than in the control group (GSE189993: 8.5 vs. 6.2; GSE249254: 8.2 vs. 6.0; internal cohort: 8.8 vs. 6.5) (Fig. 2D, box plot marked ***P < 0.001).

Functional enrichment analysis

GO function and KEGG pathway analysis was performed for the above 19 shared differential genes using the R package clusterProfiler, with 31 significant results (Fig. 3A) for GO_BP enrichment at p < 0.05, and significant enrichment for pathways such as “regulation of circadian rhythm”, “hepatocyte apoptotic process” and “epithelial cell apoptotic process” pathways. There were 20 significant results for GO_CC enrichment, with significant enrichment for the pathways “nuclear matrix”, “nuclear periphery”, “Parkin-FBXW7- Cul1 ubiquitin ligase complex”. GO_MF enrichment returned 63 significant results, significantly enriched for “exoribonuclease II activity”, “gastrin receptor activity”, “cholecystokinin receptor binding”. KEGG enrichment had 8 significant results, with significant enrichment for the pathways “Phenylalanine metabolism”, “Histidine metabolism”, and “Calcium signaling pathway”. Phenylalanine metabolism”, ‘Histidine metabolism’, ‘Calcium signaling pathway’ and other pathways. These results reveal the potential roles of shared differential genes in cellular localization, metabolic regulation, and signal transduction, providing a functional-level explanation for the molecular mechanisms of MMD. For example, enrichment of the calcium signaling pathway suggests that abnormal contraction of vascular smooth muscle cells may be associated with stenosis in MMD, and dysregulation of circadian rhythm genes may affect endothelial cell metabolic homeostasis and exacerbate vascular remodeling.

(A) GO and KEGG analysis results. The vertical axis represents the enriched items. The horizontal axis represents the degree of enrichment. The size of the circle indicates the number of genes. The color of the circle indicates the p-value. Red indicates a smaller p-value, and blue indicates a larger p-value. (B) Results of GSEA analysis. The top is line of enrichment score (ES) trajectory. Peak position is maximum ES. The Middle is vertical ticks of marking gene set members in ranked gene list. The Bottom is rank distribution of all genes.

The study first assessed the global pathway enrichment trend of differential genes in the self-assessment data by GSEA. This was done by sorting all genes based on the Log2FC values of differential analysis, and screening for significant pathways with corrected P < 0.05 against the KEGG subset of MSigDB. The results (Fig. 3B) showed 49 pathways were significantly enriched, with the top five up-regulated (ALLOGRAFT_REJECTION, ASCORBATE_AND_ALDARATE_METABOLISM etc.) and top five down-regulated (SYSTEMIC_LUPUS_ERYTHEMATOSUS, KEGG_STEROID_BIOSYNTHESIS etc.) pathways highlighted, suggesting that MMD may involve activation or inhibition of these pathways.

Immune infiltration analysis

The level of immune cell infiltration was assessed by ssGSEA, which revealed that the proportion of pro-inflammatory cells (neutrophils, M1 macrophages) was significantly higher in the MMD group (P < 0.05), while the proportion of regulatory T-cells (Treg) and resting NK-cells decreased (Fig. 4A, box line plot labeled *P < 0.05). Figure 4B further revealed the correlation between characterized genes and immune cells: in Testdata, KRT8 and KRT18 were associated with neutrophils (positive correlation, r > 0.4, P < 0.01) and M1 macrophages (r > 0.3, P < 0. 05), which may be related to the fact that inflammatory factors promote the recruitment of immune cells by regulating the release or expression of endothelial adhesion molecules; On the other hand, NT5C2 was associated with B cells (negative correlation, r<−0.35, P < 0.05) and dendritic cells (negative correlation, P < 0.01), which may affect purine metabolism and antigen-presenting function.

A: Immunocyte Infiltration Score Grouping Box Line Chart. The vertical axis represents cell abundance. The horizontal axis represents immune cells. Blue indicates the control group. Red indicates the MMD group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. B: Heatmap of immune cell correlation with characterized genes. The vertical axis represents differentially expressed genes. The horizontal axis represents immune cells. Red indicates positive correlation. Blue indicates negative correlation. The deeper the.

Machine learning screening for diagnostic markers and model building

LASSO regression, SVM-RFE and Boruta were used to screen the feature genes, and the final intersection obtained KRT8, KRT18 and NT5C2 (Fig. 5A–-D). In further validation, Figure 5E showed that the expression of KRT8, KRT18 and NT5C2 in Testdata differed significantly between the disease group and the control group, and the trend of expression was consistent (e.g. KRT8/KRT18 were up-regulated and NT5C2 were down-regulated), which were finally selected as characterized genes.

(A) Path diagram of Lasso regression coefficients. (B) Cross-validation curves for Lasso regression. The X-axis is the logarithm of the penalty coefficient log(λ), and the Y-axis is the likelihood deviation, with a smaller Y-axis indicating a better fit to the equation. The top number then shows the number of variables left in the equation for different λ. The two dashed lines on the graph, represent two particular values of lambda(λ). The dashed line on the left is λ min, meaning the λ with the smallest deviation, representing the highest model fit for that value of lambda. The dashed line on the right is λ-se, meaning 1 standard error to the right of the minimum λ. (C) SVM-RFE feature number determination. The horizontal coordinate represents the number of feature genes, and the vertical coordinate represents the generalization error under 10-fold cross-validation. The trend of the folded graph line represents the relationship between the number of feature genes and the generalization error, with the lowest error and highest correctness obtained when the number of feature genes. (D) Boruta feature number determination. The vertical axis represents the importance scores of each gene. The horizontal axis represents genes name. The importance of genes represented by green, yellow, red, and blue decreases successively. (E) Candidate characterization gene expression level violin line plot. The vertical axis represents the expression level of the gene. The horizontal axis indicates the groups. Blue represents the control group, and red represents the MMD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure S3A-C (ROC curves) verified the diagnostic performance of the method, and the AUC values of the test dataset were all greater than 0.75, indicating that these genes have a strong discriminatory effect on MMD. The column-line graph model (Figure S3D) constructed based on the three genes showed high prediction accuracy in both the training and validation sets, the calibration curve (Figure S3E) showed that the prediction was highly consistent with the actual risk, and the decision curve (Figure S3F) demonstrated that the model had a significant net gain in the range of 10-80% threshold. The method was evaluated in GSE249524 and the test model, and the AUC values were all greater than 0.75 (Figure S3.G, H).

Overexpression of KRT8 enhances angiogenic potential of HBMECs by promoting tubulogenesis and migration

We first validated the transfection efficiency of the KRT8-overexpressing plasmid (oe-KRT8) via qPCR. Compared to the control and empty vector-transfected (oe-vector) groups, oe-KRT8-transfected HBMECs exhibited a 4.2-fold increase in KRT8 mRNA levels (P < 0.01), confirming successful plasmid construction and transfection. Subsequently, a Matrigel-based tubule formation assay demonstrated that oe-KRT8 significantly augmented the angiogenic capacity of HBMECs (Fig. 6A). After 12 h of incubation, the total branch length of capillary-like structures in the oe-KRT8 group (352.7 ± 18.5 μm) was 63.8% and 54.3% higher than that in the control (215.3 ± 15.2 μm) and oe-vector groups (228.6 ± 16.8 μm), respectively (P < 0.05). No significant difference was observed between the control and oe-vector groups (P > 0.05), excluding nonspecific effects of vector transfection. (Fig. 6B, C, D)

Overexpression of KRT8 promotes tubule formation and enhances migratory capacity in HBMECs. (A) The tubule formation assay of HBMEC cells (Bar = 200 μm). (B) Validation of transfection efficiency by qPCR. The expression level of KRT8 in the oe-vector group was significantly higher than that in the control group. The expression level of KRT8 in the oe-KRT8 group was significantly higher than that in both the control group and the oe-vector group. White represents the control group. Blue represents the oe-vector group. Red represents the oe-KRT8 group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (C) Number of tubule branches. The number of tubule branches in the oe-KRT8 group was significantly higher than that in the oe-vector group. White represents the control group. Blue represents the oe-vector group. Red represents the oe-KRT8 group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (D) Total tubule length. The total tubule length in the oe-KRT8 group was significantly longer than that in the oe-vector group. White represents the control group. Blue represents the oe-vector group. Red represents the oe-KRT8 group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. E: The number of migrating cells corresponding to different groups. The number of migrating cells in the oe-KRT8 group was significantly higher than that in the oe-vector group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. F: Stained images of migrating cells in different groups under a microscope *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (Bar = 100 μm).

To further assess the impact of KRT8 on endothelial cell motility, a Transwell migration assay revealed that oe-KRT8-transfected HBMECs displayed a 2.45-fold increase in migrated cell numbers (128.3 ± 9.7 cells/field) compared to the control (52.4 ± 6.2 cells/field) and oe-vector groups (58.1 ± 7.5 cells/field) (P < 0.01). Consistent with tubulogenesis results, no statistical difference existed between control and oe-vector groups (P > 0.05), underscoring the specificity of KRT8 in driving migratory behavior. (Fig. 6E, F)

PPI network

We constructed a PPI with 19 shared differential genes based on the STRING database (confidence threshold = 0.15). Key hub genes in the network such as KRT8 and KRT18 (members of the keratin family) suggest a central role in the maintenance of the cytoskeleton or signaling by extensively connecting to other nodes, while the high connectivity of FBXW7 (a member of the ubiquitin ligase complex) may be involved in the regulation of protein degradation. Node colors distinguish gene expression trends (e.g., red for up-regulation, blue for down-regulation), e.g., up-regulation of KRT8/KRT18 may be associated with abnormal vascular proliferation, whereas down-regulation of NT5C2 may affect purine metabolism. The confidence level of the edges is low (0.15), but some of the interactions (e.g., KRT8-KRT18) may be based on experimental support, and other associations (e.g., CIPC-KCNA4) require further validation. The network shows a modular distribution: perinuclear-related genes (e.g., nuclear matrix genes) may form structural maintenance-associated clusters, while metabolic genes (e.g., NT5C2, KCNA4) are associated with calcium signaling or amino acid metabolism pathways; isolated nodes (e.g., POU6F2) are suggestive of independent functions or uncaptured interactions. Despite the presence of false positives that may be introduced by low confidence, the network revealed the synergistic roles of shared genes in metabolism and immune regulation (in agreement with the results of enrichment analysis), especially the pivotal position of KRT8/KRT18, which provides important clues for subsequent mechanistic studies and target screening, but experimental validation is needed to complement the data limitations.(Figure S1B).

Integration and resolution of small molecule drug prediction and multifactorial regulatory networks

Next, we integrated the regulatory networks of transcription factors (TFs), miRNAs and characterized genes to reveal the molecular interaction framework of disease progression (Figure S2A). STAT3 directly binds to the KRT8 promoter after activation through the IL-6/JAK pathway, driving its high expression and promoting endothelial cell migration and proliferation; NF-κB forms a negative feedback loop of “inflammation-metabolism” by inhibiting NT5C2. miR-21-5p exacerbates oxidative stress injury by targeting the 3’U of NT5C2 mRNA at the miRNA level. Inflammation-metabolism” negative feedback loop through the inhibition of NT5C2, which exacerbates oxidative stress injury. miRNA level, miR-21-5p inhibits the translation of NT5C2 mRNA by targeting its 3’UTR, which leads to purine metabolism disruption and activation of inflammatory vesicles, whereas dual inhibition of miR-155-5p (KRT18 and NT5C2) may amplify the signaling of vascular remodeling. These pathways collectively constitute the “inflammatory pathway”. Together, these pathways constitute an “inflammation-metabolism” synergistic axis, which may serve as an interplay between chronic inflammation and structural remodeling of the vasculature in MMD. For example, the interaction of the STAT3-KRT8 axis with the miR-21-5p-NT5C2 axis may accelerate disease progression through positive feedback, whereas cross-functional regulation of NF-κB (proinflammatory versus metabolic inhibition) highlights the need for multi-targeted interventions.

We integrated the DrugBank and DGIdb databases based on the above methodology and constructed the interaction network between the previously screened MMD signature genes (KRT8, KRT18, and NT5C2) and small-molecule drugs (Figure S2B), which revealed the potential immunotherapeutic targets and drug localization strategies. NT5C2, a core gene of the purine metabolic pathway43, was significantly associated with seven drugs, including nucleoside analogs (e.g., ribavirin, mercaptopurine) and immunomodulators (e.g., polyethylene glycol interferon α−2a).

The association of KRT8 with copper ions suggests its involvement in metal ion-mediated pathological processes. Copper ions, as LOX enzyme cofactors, may promote collagen cross-linking and exacerbate vascular fibrosis, which may be inhibited by copper chelating agents (e.g., penicillamine), but their direct effects on KRT8 need to be experimentally verified. Small molecule inhibitors targeting KRT8 (e.g., keratin polymerization blockers) may inhibit aberrant proliferation by stabilizing the endothelial cytoskeleton, but optimization of blood-brain barrier penetration efficiency is required. The association of KRT18 with mitomycin (DNA cross-linking agents) and IL-6 reflects its dual roles, with mitomycin potentially inhibiting vascular proliferation by inducing apoptosis in endothelial cells, but its cellular toxicity may exacerbate tissue damage; co-regulation of IL-6 with KRT18 or amplification of inflammatory signals through the STAT3 pathway.

Small molecule drug networks and regulatory networks form a closed-loop logic of “target-mechanism-intervention”. For example, ribavirin targeting NT5C2 can simultaneously regulate purine metabolism and miR-21-5p-mediated epigenetic effects; STAT3 inhibitors (e.g., small-molecule JAK inhibitors) may inhibit angiogenesis by blocking KRT8 expression, while copper chelators may indirectly alleviate KRT8-mediated fibrosis. In addition, co-targeting strategies (e.g., STAT3 inhibitors + purine metabolism modulators) are expected to enhance efficacy through multipath way synergy.

Discussion

MMD is a rare cerebrovascular disease characterized by progressive stenosis and abnormal angiogenesis of intracranial arteries. In this study, we conducted RNA seq on the STA of patients with MMD and explored potential biomarkers in MMD with machine learning. Among the six key genes (KRT8, KRT18, NT5C2, CIPC, FBXW7, KCNA4), KRT8 may promote vascular remodeling in MMD by regulating the tube-forming ability of endothelial cells.

Current studies have found that genetic factors play an important role in its pathogenesis, and in particular, mutations in the RNF213 gene are widely recognized as a major genetic risk factor for MMD in East Asian populations5,44,45. In addition, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and family lineage analysis suggest that other genes, such as BRCC346,47 and GUCY1A348,49, may also be involved in the pathologic process of MMD. In recent years, with the advancement of gene editing technologies (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9), researchers have been able to mimic the effects of the RNF213 mutation on vascular development in an in vitro model, revealing that knockdown of this gene amplifies the VEGF-mediated effect of abnormal angiogenesis50. However, the molecular network of MMD is complex with significant genetic heterogeneity, and most studies are still limited to single genes or small sample cohorts, which have not yet resulted in a systematic explanation.

It has been reported that mutations in KRT can cause changes in the oxygen content of tissues51. In this study, it was observed that the expression level of KRT8 was significantly upregulated in Moyamoya disease. This suggests that KRT8 may be related to the formation of hypoxic environment in Moyamoya disease. Upregulated KRT17 promotes angiogenesis in colon cancer through the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway52. Previous studies suggested that the histology of patients with Moyamoya disease showed hyperplasia of the vascular intima, and immunofluorescence indicated the migration of smooth muscle cells to the middle membrane. It has been also shown that serum from MMD patients promotes endothelial cell proliferation, cytotubule formation, and cytoskeletal expansion53. And in the tube formation assay, we found that upregulated KRT8 could enhance the tube formation ability of endothelial cells. Yang et al. suggested that when KRT8 expression is elevated, it affects the adhesion and permeability of tight junctions and regulates cell-matrix adhesion via integrins54,55, leading to cytoskeletal proliferation and the formation of hyper adhesion56. This suggests that KRT8 may promote vascular remodeling by regulating endothelial cells in MMD. Moon et al. reported that damaged blood vessels would simultaneously express KRT8 and KRT18, and that the activation of the cytoskeleton and growth factor receptors was required57. Similarly, in our previous research, it was found that FLAN and ZXY in Moyamoya disease would participate in the pathogenesis of Moyamoya disease by regulating the cytoskeleton53. This study was a proteomic analysis of peripheral blood in patients with MMD. However, peripheral blood is difficult to accurately reflect the specific pathological changes of the pathological vessels in MMD In this study, we conducted RNA seq on the superficial temporal arteries of patients with MMD and found that KRT8 and KRT18 were simultaneously upregulated in Moyamoya disease. This suggests that the upregulation of KRT8 and KRT18 may be related to vascular damage in Moyamoya disease, and the cytoskeleton may be an important intermediate link. In this study, transcriptomic data suggested that its expression was significantly associated with neutrophil, M1 macrophage infiltration. Recent studies have shown that KRT8 may promote endothelial cell secretion of chemokines such as IL-8 through activation of the NF-κB pathway55, or influence immune cell adhesion by altering cytoskeletal tension51. These mechanisms may collectively mediate the vascular inflammatory microenvironment in MMD, and future studies are needed to further resolve KRT8-mediated endothelial-immune cell interactions through co-culture models.Our study reveals the role of Keratin family members KRT8 in the pathogenesis of MMD. Through transcriptome analysis of public datasets (GSE189993, GSE249254) and our own collected vascular tissues, we confirmed the significant upregulation of KRT8 and KRT18 in patients with MMD and found in an in vitro assay that overexpression of KRT8 promotes cellular tubule formation and cell migration in HBMECs compared with controls. This study provides experimental evidence that the pro-angiogenic effect of KRT8 in HBMECs is mediated by its dual regulatory role in orchestrating cell migration and lumen formation. These findings not only elucidate a previously unrecognized mechanism underlying KRT8-driven cerebrovascular remodeling but also lay a foundational framework for investigating its pathophysiological contributions to MMD, a cerebrovascular disorder characterized by aberrant angiogenesis. Importantly, our data position KRT8 as a promising molecular candidate for therapeutic targeting, offering novel strategies to modulate pathological angiogenesis in MMD and related neurovascular pathologies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, through machine learning algorithms, we identified KRT8, KRT18, and NT5C2 as robust diagnostic markers for MMD, with KRT8 showing significant upregulation in MMD patients. In vitro experiments demonstrated that overexpression of KRT8 enhances the angiogenic capacity of HBMECs, indicating its contribution to the pathological vascular thickening observed in MMD. Additionally, the protein-protein interaction network highlighted the central role of KRT8 and KRT18 in cytoskeletal maintenance and signaling, further supporting their involvement in disease progression. The identification of small-molecule drugs targeting these genes, such as ribavirin and copper chelators, offers promising therapeutic avenues. These findings underscore the importance of KRT8 in endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling, providing a foundation for future mechanistic studies of MMD.

Limitation

In this study, the sample size of moyamoya disease (MMD) patients in our transcriptomic analysis was relatively limited. In addition, the number of patients in the validation dataset may have limited the interpretation of the results. Second, while our in vitro experiments demonstrated KRT8’s pro-angiogenic effects in HBMECs, these models cannot fully replicate the complex vascular microenvironment in MMD, such as hemodynamic forces or immune cell interactions.

Data availability

The data presented in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Scott, R. M. & Smith, E. R. Moyamoya disease and Moyamoya syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 360 (12), 1226–1237 (2009).

He, S. et al. Advances in Moyamoya disease: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapeutic interventions. MedComm 2025 (6(2)), pe70054 (2020).

Sato, Y. et al. Characteristics of Moyamoya disease based on National registry data in Japan. Stroke, 50(8). (2019).

Un, L. S. et al. Surgical treatment of adult Moyamoya disease. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 20 (7), 22 (2018).

Liu, W. et al. Identification of RNF213 as a susceptibility gene for Moyamoya disease and its possible role in vascular development. Plos One. 6 (7), e22542 (2011).

Hitomi, T. et al. Downregulation of Securin by the Variant RNF213 R4810K (rs112735431, G > A) Reduces Angiogenic Activity of Induced Pluripotent Stem cell-derived Vascular Endothelial Cells from Moyamoya Patients (Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2013).

Kobayashi, H. et al. Biochemical and functional characterization of RNF213 (Mysterin) R4810K, a susceptibility mutation of Moyamoya disease, in angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J. Am. Heart Association, 4(7). (2015).

Ihara, M. et al. Moyamoya disease: diagnosis and interventions. Lancet Neurol. 21 (8), 747–758 (2022).

Asselman, C. et al. Moyamoya disease emerging as an immune-related angiopathy. Trends Mol. Med. 28 (11), 939–950 (2022).

Weng, L. et al. Association of increased Treg and Th17 with pathogenesis of Moyamoya disease. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 3071 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. Th17/IL-17 induces endothelial cell senescence via activation of NF-κB/p53/Rb signaling pathway. Lab. Invest. 101 (11), 1418–1426 (2021).

Kumar, P. & Subramaniyam, G. Molecular underpinnings of Th17 immune-regulation and their implications in autoimmune diabetes. Cytokine 71 (2), 366–376 (2015).

Kanoke, A. et al. Temporal profile of magnetic resonance angiography and decreased ratio of regulatory T cells after immunological adjuvant administration to mice lacking RNF213, a susceptibility gene for Moyamoya disease. Brain Res. 1642, 1–9 (2016).

Lužnik, Z. et al. Regulatory T cells in angiogenesis. J. Immunol. 205 (10), 2557–2565 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Proteomic profiling of exosomes from hemorrhagic Moyamoya disease and dysfunction of mitochondria in endothelial cells. Stroke 52 (10), 3351–3361 (2021).

Fujimura, M. et al. Increased serum production of soluble CD163 and CXCL5 in patients with Moyamoya disease: involvement of intrinsic immune reaction in its pathogenesis. Brain Res. 1679, 39–44 (2018).

Guo, L. et al. CD163 + macrophages promote angiogenesis and vascular permeability accompanied by inflammation in atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 128 (3), 1106–1124 (2018).

Peng, W. et al. Targeted delivery of CD163(+) macrophage-derived small extracellular vesicles via RGD peptides promote vascular regeneration and stabilization after spinal cord injury. J. Control Release. 361, 750–765 (2023).

Wu, M. Y. & Hill, C. S. Tgf-beta superfamily signaling in embryonic development and homeostasis. Dev. Cell. 16 (3), 329–343 (2009).

Chen, Y. et al. TGFβ1 as a predictive biomarker for collateral formation within ischemic Moyamoya disease. Front. Neurol. 13, 899470 (2022).

Makino, T. et al. Cytokeratins 18 and 8 are poor prognostic markers in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. Br. J. Cancer. 101 (8), 1298–1306 (2009).

Hesse, M., Magin, T. M. & Weber, K. Genes for Intermediate Filament Proteins and the Draft Sequence of the Human Genome: Novel Keratin Genes and a Surprisingly High Number of Pseudogenes Related To Keratin Genes 8 and 18114p. 2569–2575 (JOURNAL OF CELL SCIENCE, 2001).

Harald et al. Phosphorylation of Cytokeratin 8 and 18 in Human Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells of Atherosclerotic Lesions and Umbilical Cord Vessels96 (Basic research in cardiology, 2001).

Barrett, T. et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets—update. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 (Database issue), 1005–1010 (2013).

Fukui, M. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis (‘moyamoya’ disease). Research committee on spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis (Moyamoya Disease) of the ministry of health and welfare, Japan. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 99 (Suppl 2), S238–S240 (1997).

Audrey, K. et al. Importing arrayexpress datasets into r/bioconductor. Bioinformatics 25 (16), 2092–2094 (2009).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (7), e47 (2015).

Mao, Y. et al. Integrative analysis of CeRNA network reveals functional LncRNAs associated with independent recurrent prognosis in colon adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. Int. 21 (1), 352 (2021).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102 (43), 15545–15550 (2005).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–D677 (2025).

Yu, G. et al. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics 16 (5), 284–287 (2012).

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell. Syst. 1 (6), 417–425 (2015).

Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14, 7 (2013).

Sanz, H. et al. SVM-RFE: selection and visualization of the most relevant features through non-linear kernels. BMC Bioinform. 19 (1), 432 (2018).

Hamidi, F. et al. Identifying potential Circulating MiRNA biomarkers for the diagnosis and prediction of ovarian cancer using machine-learning approach: application of Boruta. Front. Digit. Health. 5, 1187578 (2023).

Ali, H. et al. Application and impact of Lasso regression in gastroenterology: A systematic review. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 42 (6), 780–790 (2023).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77 (2011).

Wishart, D. S. et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the drugbank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (D1), D1074–d1082 (2018).

Wagner, A. H. et al. DGIdb 2.0: mining clinically relevant drug-gene interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (D1), D1036–D1044 (2016).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13 (11), 2498–2504 (2003).

Zhang, Q. et al. hTFtarget: A comprehensive database for regulations of human transcription factors and their targets. Genomics Proteom. Bioinf. 18 (2), 120–128 (2020).

Li, J. H. et al. StarBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (Database issue), D92–D97 (2014).

Pesi, R. et al. Cytosolic 5’-Nucleotidase II Is a Sensor of Energy Charge and Oxidative Stress: A Possible Function as Metabolic Regulator. Cells, 10(1). (2021).

Kamada, F. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies RNF213 as the first Moyamoya disease gene. J. Hum. Genet. 56 (1), 34–40 (2011).

Zhang, Q. et al. RNF213 as the major susceptibility gene for Chinese patients with Moyamoya disease and its clinical relevance. J. Neurosurg. 126 (4), 1106–1113 (2017).

Miskinyte, S. et al. Loss of BRCC3 deubiquitinating enzyme leads to abnormal angiogenesis and is associated with syndromic Moyamoya. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88 (6), 718–728 (2011).

Dai, D. et al. Serum MiRNA signature in Moyamoya disease. PLoS One. 9 (8), e102382 (2014).

Wallace, S. et al. Disrupted nitric oxide signaling due to GUCY1A3 mutations increases risk for Moyamoya disease, achalasia and hypertension. Clin. Genet. 90 (4), 351–360 (2016).

Luo, M. et al. The Guanylate Cyclase Soluble Subunit Alpha-1 Deficiency Impairs Angiogenesis in Zebrafishes and Mice: in Vivo and in Vitro Studies (Mol Neurobiol, 2025).

Roy, V. et al. RNF213 Loss-of-Function promotes angiogenesis of cerebral microvascular endothelial cells in a cellular state dependent manner. Cells, 12(1). (2022).

Kröger, C. et al. Placental vasculogenesis is regulated by Keratin-Mediated hyperoxia in murine decidual tissues. Am. J. Pathol. 178 (4), 1578–1590 (2011).

Ji, R. et al. Keratin 17 upregulation promotes cell metastasis and angiogenesis in colon adenocarcinoma. Bioengineered 12 (2), 12598–12611 (2021).

He, S. et al. Upregulated cytoskeletal proteins promote pathological angiogenesis in Moyamoya disease. Stroke 54 (12), 3153–3164 (2023).

Salhia, B. et al. Integrated genomic and epigenomic analysis of breast cancer brain metastasis. PLoS One. 9 (1), e85448 (2014).

Fang, J. et al. High KRT8 expression promotes tumor progression and metastasis of gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 108 (2), 178–186 (2017).

Yang, S. et al. Crip2 affects vascular development by fine-tuning endothelial cell aggregation and proliferation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 82 (1), 110 (2025).

Moon, M. C. et al. Injury-induced expression of cytokeratins 8 and 18 by vascular smooth muscle cells requires concurrent activation of cytoskeletal and growth factor receptors. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 86 (5), 223–231 (2008).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all participants for their support and cooperation.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (82471337) and National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2023-PUMCH-E-011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SHH, YLZ, ZGH conceived and designed the study. SHH, ZGH, JLY, ZYZ, CXL, YTL performed bioinformatic analysis. SHH, JLY, ZYZ performed in vitro experiments. YLZ, XY and SHH contributed reagents, materials, and analytical tools. All the authors participated in the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China (I-24PJ1573). All participants signed informed consent forms.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Z., Yuan, J., Zhou, Z. et al. Machine learning identifies KRT8 dysregulation and endothelial remodeling in Moyamoya disease. Sci Rep 15, 24171 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10003-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10003-3