Abstract

Osteoporosis (OP) is a systemic bone disease characterized by reduced bone density and quality, leading to increased bone fragility and a higher risk of fractures. The relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and OP or osteopenia remains controversial, as does the impact of weight change on these conditions. Moreover, few studies have investigated whether body mass index (BMI) serves as a mediator in the association between SUA and OP or osteopenia. This study aimed to elucidate the complex interactions between SUA, OP or osteopenia, and BMI. A cross-sectional study from the REACTION study was conducted to examine the association between SUA and OP or osteopenia. Various logistic regression and restricted cubic spline models were employed to analyze the pairwise correlations among these variables, and interaction analysis was performed to assess differences between subgroups. Mediation models were utilized to determine the mediating role of BMI. A cross-sectional study from the REACTION study was conducted to examine the association between SUA and OP or osteopenia. Various logistic regression and restricted cubic spline models were employed to analyze the pairwise correlations among these variables, and interaction analysis was performed to assess differences between subgroups. Mediation models were utilized to determine the mediating role of BMI. In female-dominated populations, SUA appears to have a protective effect against OP or osteopenia, with BMI potentially serving as a partial mediator. Thereby, maintaining SUA and BMI within an optimal range may help reduce the risk of OP or osteopenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a systemic bone disease characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of bone microarchitecture, leading to increased fragility and a higher risk of fractures1,2,3. Op and osteopenia affect approximately 19.7% and 40.4% of the general population, respectively. In postmenopausal women, the prevalence is even higher, reaching 27.4% for OP and 42.1% for osteopenia4. Due to their high prevalence, significant economic burden, and elevated disability rates, OP and osteopenia have become serious public health concerns.

Serum uric acid (SUA) is the end product of purine nucleotide degradation in the organism and a well-established risk factor for gout5. Elevated SUA levels, or hyperuricemia, can lead to various diseases, including chronic kidney disease (CKD), cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome6,7,8. Recent studies have also suggested that increased SUA levels may be associated with a reduced prevalence of osteoporosis9. Research has shown that SUA acts as a natural endogenous antioxidant, capable of scavenging free radicals and exhibiting anti-oxidative stress effects10,11,12. Consequently, SUA may exert a protective effect against OP through direct actions on bone metabolism-related cells.

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a key indicator of the body’s nutritional status. Most studies suggest that higher body weight increases the physical load on bones, thereby stimulating bone formation and enhancing bone density. Additionally, elevated body weight and BMI have long been shown to protect against the decline in bone mineral density (BMD)13. Conversely, being underweight is an independent risk factor for osteoporosis14. A meta-analysis found that low BMI is significantly associated with a higher risk of fractures15. Furthermore, research indicates that BMI is positively correlated with SUA levels16,17.

Given the close associations among these factors and the significant physiological and environmental differences between men and women, it is essential to further assess their intrinsic relationships across different gender groups. This study investigated the complex associations between SUA, BMI, and OP or osteopenia in men over 40 years of age and postmenopausal women using cross-sectional methods. It also closely examined the mediating role of BMI in the relationship between SUA and OP or osteopenia. The findings aim to support the development of more effective and targeted preventive strategies.

Materials and methods

Study population

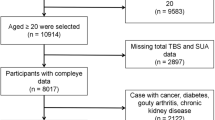

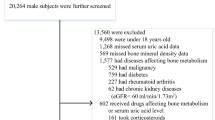

In this study, 10,207 community residents aged over 40 from Dalian who participated in the REACTION study, a project investigating the risk of malignancies in T2DM patients in China from August to December 2011, were initially considered. Among them, male and postmenopausal female participants who completed bone mineral density examination were selected, a total of 1724 cases. We excluded 82 patients due to the presence of bone diseases, malignant tumors, severe cardiac, hepatic, or renal dysfunction, or chronic use of glucocorticoids that could impact bone metabolism. After removing an additional 86 individuals with incomplete data on BMI and SUA, 1,556 participants were ultimately included in the study. The detailed exclusion process is depicted in Fig. 1. Ethical approval was granted by the REACTION Research Ethics Committee (Approval No. 2011 Linlun Review No. 14), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Measures

Definitions of OP and Osteopenia

The diagnosis of osteoporosis primarily depends on bone mineral density (BMD) measurements, which are obtained using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). The T-score is employed to evaluate the deviation of an individual’s BMD from that of a standard reference population of young healthy adults. The diagnostic criteria, based on the World Health Organization (WHO) definitions18are as follows: osteopenia is defined by a T-score between − 1.0 and − 2.5, while osteoporosis is characterized by a T-score of less than − 2.5. In our study, BMD was measured using the LUNAR PRODIGY dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) system, manufactured by GE in the United States. Specifically, the T-score for the lumbar spine (L1-L4) BMD was assessed. Following the diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis, and patients are categorized into normal, OP or osteopenia groups based on their BMD measurements.

Assessment of SUA

The exposure variable of this study was SUA, which has been measured using an automatic biochemical detector (ADVIA 2400 automatic Biochemical detector). Meanwhile, for statistical analysis, quartiles of SUA levels were divided into four groups: tquartile1 (Q1): ≤25th percentile, quartile2 (Q2): >25–50 percentile, quartile3 (Q3): >50–75 percentile, quartile4 (Q4): >75th percentile.

Assessment of BMI

We measured height and weight, allowing for the computation of BMI as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Meanwhile, quartiles of BMI levels were divided into four groups: tquartile1 (Q1): ≤25th percentile, quartile2 (Q2): >25–50 percentile, quartile3 (Q3): >50–75 percentile, quartile4 (Q4): >75th percentile.

Covariates

Age, sex, educational level, the history of diabetes (DM), stroke, coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension, hyperlipidemia and fatty liver and smoking status, alcohol consumption were self-reported by participants. Upon admission, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured. Laboratory measurements included high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), glucose (Glu), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and creatinine (Cr). Blood samples were collected in the morning after a minimum 8-hour fasting period .

Statistical analysis

Normality tests were conducted for all data. For data following a normal distribution, a t-test was performed, while the Mann–Whitney U-test was applied to data that did not follow a normal distribution. Data are presented as median values with interquartile ranges (Q25, Q75). Categorical variables are represented by N (%) and analyzed by chi-square test. Samples with missing covariate data were excluded. Various logistic regression approaches were used to explore the association between SUA, BMI and OP, osteopenia. In the absence of predefined cut-off points of SUA and BMI, the interquartile method was used for analysis. Three analytical models were developed: Model 1 (unadjusted), Model 2 (adjusted for age and sex), and Model 3 (adjusted for multiple variables including age, sex, DBP, HDL, LDL, ALT, HOMA-IR, Cr, educational level, DM, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver, smoking status and alcohol consumption). Trend tests for ordered categorical variables were performed using the Cochran-Armitage trend test. The nonlinear association between UA, BMI, OP or osteopenia was further investigated by using 3-knot restricted cubic splines (RCS). Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential modifications by covariates such as age, sex, BMI, hypertension, Stroke, CHD, DM, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver might modify the OP or osteopenia on the relationship between UA and OP or osteopenia, considering interactions significant at P < 0.05. Finally, the mediating effect of BMI between UA and OP or osteopenia was investigated by mediating analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using EmpowerStats (version 4.2) and R software (version 4.3.2), with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the 1,556 study participants, with a mean age of 60.4 years, comprising 21.5% men and 78.5% women. The prevalence of OP or osteopenia among these participants was 47.8% (744/1556). Both BMI and SUA levels were significantly lower in the OP or osteopenia group compared to those in normal subjects. Baseline data indicated significant associations of OP or osteopenia with sex, age, DBP, HDL, LDL, TC, ALT, HOMA-IR, Cr, educational level, DM, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver, smoking, and alcohol consumption.

Association between SUA and OP or osteopenia

As detailed in Table 2, after adjusting for all covariates, the correlation between SUA and OP or osteopenia in Model 3 remained significant (OR = 0.997, 95% CI 0.996–0.999, P = 0.002). SUA levels were categorized into quartiles to explore their associations with OP or osteopenia. After subsequent adjustments for potential confounders in the multiple logistic regression models, compared with Q1, the results showed that, except for Q2 and Q3, higher SUA concentrations were significantly associated with a lower incidence of OP or osteopenia in Q4 (OR = 0.651, 95% CI 0.464–0.913). Using 3-knot RCS models, we analyzed the dose-response relationship between SUA and the risk of OP or osteopenia (Fig. 2). The risk of OP or osteopenia decreased linearly with increasing SUA levels (P for linear trend = 0.009), and no significant non-linearity was observed (P for non-linearity = 0.919). Specifically, the curve showed that as SUA increased from lower levels, the risk of OP or osteopenia progressively declined, and the downward trend remained consistent across the SUA range without any obvious inflection point.

The dose–response relationship between SUA and OP or osteopenia. Graphs show OR for OP or osteopenia adjusted for age, sex, DBP, HDL, LDL, ALT, HOMA-IR, Cr, educational level, DM, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver, smoking status and alcohol consumption. Data were fitted by multivariate logistic regression models. Solid lines indicate OR, and shadow shapes indicate 95% CIs.

Association between BMI and OP or osteopenia

In Table 3, the relationship between BMI and OP or osteopenia is presented. After adjusting for all covariates, the correlation remained significant in Model 3 (OR = 0.881, 95% CI 0.849–0.914, P < 0.001). BMI was categorized into quartiles, and multiple logistic regression was used for analysis. After adjusting for confounding factors in Model 3, the ORs were as follows: for Q2, the OR was 0.547 (95% CI 0.396–0.754); for Q3, the OR was 0.425 (95% CI 0.305–0.594); and for Q4, the OR was 0.292 (95% CI 0.204–0.417), compared to Q1. Additionally, using 3-knot RCS models, we evaluated the dose-response relationship between BMI and the risk of OP or osteopenia (Fig. 3). A significant non-linear association was observed. The risk of OP or osteopenia decreased sharply with increasing BMI at lower BMI ranges, particularly below 23.979 kg/m². After reaching a BMI of around 23.979 kg/m², the risk reduction slowed and the curve plateaued, suggesting that further increases in BMI above this threshold did not substantially lower the risk.

The dose–response relationship between BMI and OP or osteopenia. Graphs show OR for OP or osteopenia adjusted for age, sex, DBP, HDL, LDL, ALT, HOMA-IR, Cr, educational level, DM, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver, smoking status and alcohol consumption. Data were fitted by multivariate logistic regression models. Solid lines indicate OR, and shadow shapes indicate 95% CIs.

Association between SUA and BM

The correlation between SUA and BMI was assessed using multiple regression analysis, with the results presented in Table 4. In the unadjusted model, SUA was positively associated with BMI (β = 4.744 95% CI 3.795–5.693 P < 0.001). After adjusting for covariates, the correlation remained significant in Model 2 (β = 4.711, 95% CI 3.804–5.618, P < 0.001) and Model 3 (β = 3.451, 95% CI 2.494–4.408, P < 0.001). When BMI was categorized into quartiles, the association between BMI and SUA continued to be statistically significant at higher BMI levels. Specifically, subjects in the highest BMI quartile experienced an 34.558 µmol/L increase in SUA compared to those in the lowest quartile (Model 3 β = 34.558, 95% CI 24.581–44.534, P < 0.001). Table 4 displays the results of the multiple regression analysis between SUA and BMI. Figure 4 illustrates the smooth curve fitting of the relationship between SUA and BMI.

Association between SUA and BMI. (a) Each black dot represents a sample. (b) The solid line indicates a smooth curve fit between the variables. The blue band indicates the 95% confidence interval of the fit. Adjusted for age, sex, DBP, HDL, LDL, ALT, HOMA-IR, Cr, educational level, DM, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver, smoking status and alcohol consumption.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses by sex, age, BMI, hypertension, stroke, CHD, DM, hyperlipidemia, and fatty liver (reported in Fig. 5) revealed no notable differences in the relationships between SUA and OP or osteopenia across the subgroups.

Subgroup analysis for the association of SUA and OP or osteopenia. Subgroup analysis of the association between SUA and OP or osteopenia, stratified by age, sex, BMI, hypertension, stroke, CHD, DM, hyperlipidemia, and fatty liver. Each square in the forest plot represents an estimated Odds Ratio (OR) for a specific subgroup. The size of the square is usually proportional to the statistical weight or sample size of that estimate. “P for interaction” tests whether there is any interaction between the subgroups.

Mediating role of BMI

In the mediation analysis, we explored the role of BMI as a mediator in the association between SUA and OP or osteopenia (Fig. 6). The results indicated that BMI weakly, yet significantly, mediated this association after adjusting for all covariates. Specifically, 13.6% of the total effect of SUA on OP or osteopenia was mediated by BMI, which was statistically significant (p = 0.032).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between SUA, OP or osteopenia, and BMI. Our findings indicate that among men aged over 40 years and postmenopausal women, higher SUA levels are associated with a decreased risk of OP or osteopenia, demonstrating an inverse correlation. Notably, within the group characterized by higher SUA levels, the risk of OP or osteopenia continues to decline as SUA concentrations further increase, suggesting a dose-dependent protective effect. Additionally, we observed a nonlinear inverse association between BMI and the risk of OP or osteopenia. Specifically, the rate of risk reduction decelerated, and the dose-response curve plateaued after a BMI threshold of approximately 23.979 kg/m² was reached. These findings indicate that maintaining a BMI above 24 kg/m² may afford protective effects against low bone mass; however, incremental increases in BMI beyond this threshold provide progressively diminishing benefits for bone health. Notably, SUA exhibited a positive correlation with BMI, and mediation analysis revealed that BMI accounts for 13.6% of the total effect of SUA on OP or osteopenia, underscoring its role as a partial mediator in this relationship.

OP and osteopenia represent significant public health challenges. Previously viewed as an unavoidable consequence of aging, they are now recognized as serious, treatable diseases due to advances in medical treatments. Identifying additional risk factors and screening for high-risk individuals are crucial for the early prevention and management of these conditions, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing economic burdens.

Numerous epidemiological studies have investigated the relationship between SUA and BMD; however, the findings have been inconsistent. A meta-analysis indicated that elevated SUA levels might play a protective role in bone metabolism disorders19. Further, several studies have established a significant association between SUA and BMD, suggesting a protective effect on bone metabolism in diverse groups, including healthy adults20elderly populations21patients with type 2 diabetes22osteoporosis patients23and postmenopausal women24. Additionally, one of the Rotterdam cohort studies found that higher SUA levels are correlated with increased BMD (at the expense of thicker cortices and narrower bone diameters)25. Our results show that higher SUA is associated with the risk of OP and osteopenia, consistent with these results. However, other studies have found no association between SUA and BMD in American adult men26 and postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes27. These discrepancies in findings may be attributed to multiple interrelated factors: first, ethnic and genetic heterogeneity plays a role as genetic variations in uric acid transporters (e.g., URAT1) and bone metabolism genes (e.g., RUNX2) differ across populations; second, age and hormonal status are critical as the lack of estrogen impedes the production of IL-1 and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)28. Notably, IL-6 and TNF-alpha, stimulated by IL-1 and TNF, respectively, incite an inflammatory response that encourages osteoclast formation and their bone-resorbing activities29. This cascade results in osteolysis, bone loss, and elevated blood calcium, contributing to BMD decline; third, comorbidities common in older populations (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome) are associated with elevated SUA, which may confound the relationship; additionally, thiazide diuretics used in hypertension further elevate SUA while impairing renal calcium reabsorption; finally, methodological disparities including differences in study design impact causal inference by failing to capture temporal associations.

In addition, in the stratified analysis, the association between SUA quartiles and OP/osteopenia exhibited distinct patterns across models. In the fully adjusted Model 3, only the highest SUA quartile (Q4) remained significantly associated with a reduced risk of OP/osteopenia (OR = 0.651, 95% CI: 0.464–0.913), while Q2 and Q3 lost statistical significance (Q2: P = 0.602; Q3: P = 0.066). Notably, the trend test remained significant (P = 0.006), indicating a consistent linear gradient in risk across SUA quartiles. OP risk decreases monotonically with increasing SUA quartiles (Q1 to Q4 ORs: 1.000→0.921→0.744→0.651). However, Q2 and Q3 exhibited weaker effects (OR closer to 1) that fell below the statistical significance threshold, possibly because their SUA concentrations were insufficient to trigger meaningful biological changes. The protective impact of SUA strengthens with higher exposure levels, becoming statistically detectable only at the upper quartile (Q4). Additionally, quartile stratification divides the sample into four subgroups, reducing the number of participants in each category. The modest reduction in risk for Q2 and Q3, combined with relatively wide confidence intervals due to smaller sample sizes, may have contributed to the lack of statistical significance.

The action mechanism of SUA on OP or osteopenia remains unclear; however, its potential protective mechanism could be delineated as follows: SUA acts as a significant endogenous antioxidant, particularly under oxidative stress11,30which facilitates the removal of free radicals from the blood. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can suppress the differentiation of osteoblasts while promoting the differentiation and activation of osteoclasts, ultimately leading to osteopenia31,32. By scavenging free radicals and ROS, SUA may reduce bone loss. Moreover, a previous study investigated the interaction between uric acid and bone mineral density, demonstrating that uric acid regulates osteoblast differentiation via the Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2)/core-binding factor subunit alpha-1 (CBF-α-1) and Wingless-related integration site (Wnt)-3a/β-catenin signaling pathways, as well as 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 133. This regulation guides bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells(hBMSCs). to differentiate into osteoblasts. As is well known, RUNX2/ CBF-α-1, a member of the Runt domain gene family, serves as a specific transcription factor for osteoblast differentiation34. In an in vitro cellular model, we investigated the effects of different concentrations of SUA on the expression of RUNX2/ CBF-α-1 during the osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs. The results showed that SUA could promote the differentiation of hBMSCs into osteoblasts by upregulating the expression of Cbfa1/Runx235. In bone cells, the Wnt protein initiates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway36which plays a crucial role in bone formation. A study reported that in β-catenin knockout mice, both cortical and cancellous bone mass decreased significantly during mesenchymal precursor cell differentiation into chondrocytes, while osteoclastogenesis was promoted, potentially leading to osteoporosis. Analyses of Wnt-3a and β-catenin mRNA revealed that their expression levels increased with escalating uric acid concentrations in a dose-dependent manner35. Furthermore, higher SUA levels correlate with diminished kidney function, leading to decreased production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. This reduction in turn stimulates PTH production and increases serum calcium levels37thus increasing bone density. Additionally, another study demonstrated that uric acid enhances osteogenic differentiation and inhibits adipogenic differentiation of human bone mesenchymal stem cells35.

The results of the mediation analysis indicated that part of the effect of SUA on OP or osteopenia might be mediated, in part, through BMI. Previous studies have consistently confirmed a positive association between BMI and SUA16,17. Simultaneously, research has shown that BMI is positively correlated with BMD13,38. Notably, obese women exhibit a lower prevalence of osteopenia and OP compared to their normal-weight and overweight counterparts39. High BMI, acting as a mechanical load, enhances the stimulation of bone and muscle, thereby promoting bone reconstruction and reducing the incidence of OP29. On the other hand, by modulating the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) pathway, osteoclast differentiation is inhibited, and bone resorption is consequently reduced40. It is essential that we identify how, compared to leaner individuals, obese persons typically exhibit higher serum levels of estrogen and PTH, lower levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), and possibly reduced levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3)41,42,43Each of these factors exerts specific actions on bone health. These findings constitute a supporting factor for the results of our mediation analysis. Notably, the mediating effect of BMI on the association between SUA and OP/osteopenia was modest, accounting for 13.6% of the total effect. This proportion indicates that BMI explains a small fraction of the total effect, with the remaining 86.4% potentially attributable to direct pathways or other mediating/moderating factors. Several mechanisms may underlie this observation: Firstly, direct metabolic effects of SUA: SUA could influence bone metabolism independently of BMI, such as through oxidative stress-induced osteoblast inhibition32. Secondly, shared genetic or environmental confounders: Unmeasured factors (e.g., inflammation, insulin resistance) may concurrently affect SUA, BMI, and bone density, creating spurious mediation. For instance, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) directly promote osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption44while insulin resistance is inversely associated with cortical bone volume and strength45,46. Moreover, sex hormones, including estrogen47represent another category of plausible mediators, as they regulate both adiposity and bone remodeling processes, potentially influencing bone health. Consequently, the mediating role of BMI should be interpreted with caution, and future studies are recommended to employ multi-mediator models to disentangle these complex relationships.

This study redefines our comprehension of the complex relationship among SUA, OP or osteopenia, and BMI, emphasizing BMI’s potential role as a mediator. This analysis has several limitations. Firstly, a notable limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which precludes the verification of temporal relationships among SUA, BMI, and osteoporosis. All variables were measured at a single time point, as they were assessed concurrently. Consequently, the inferred mediating pathway should be interpreted with caution, as it relies on theoretical assumptions rather than empirical temporal evidence. Future longitudinal studies with repeated measurements are essential to establish the causal sequence and validate the mediating effects proposed here. Secondly, the analysis did not include data on physical activity levels, dietary patterns, urate-lowering therapy, vitamin D, and PTH, which are known to influence SUA, BMI, and BMD simultaneously. These unmeasured covariates could have influenced the strength or direction of the relationships reported here. Future studies should incorporate comprehensive assessments of lifestyle factors and biochemical markers to better isolate the independent effects of SUA and BMI on bone health. Thirdly, in this study, females comprised 78.5% of the sample, potentially limiting the results’ applicability to males. Physiological disparities in uric acid and bone metabolism exist between genders, with estrogen protecting female bone density and regulating uric acid excretion, while testosterone plays a distinct role in males. Lifestyle factors and comorbidities also vary between genders, contributing to heterogeneity in the hyperuricemia-OP or osteopenia association. Thus, the generalizability of our findings to males warrants caution, and our study is explicitly stated as applicable only to female-dominated populations. Finally, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution regarding their generalizability. The sample was recruited from a single community in Dalian, China, and predominantly included Han Chinese individuals. This demographic characteristic may limit the external validity when extending the conclusions to other ethnic groups or regions with distinct socioeconomic backgrounds. Therefore, the results are primarily applicable to Han Chinese populations in similar urban communities with comparable lifestyles and environmental exposures. Future studies involving multi-center sampling and diverse ethnic groups are warranted to validate these findings across broader populations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study sought to examine the complex relationships among BMI, SUA, and OP or osteopenia in men over 40 years of age and postmenopausal women. In female-dominated populations, it identified a linear negative correlation between SUA and OP or osteopenia. Furthermore, BMI was found to play only a minor mediating role in the risk of OP or osteopenia associated with SUA. These findings offer new insights for the prevention and treatment of these conditions.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Klara, J. & Lewandowska-Łańcucka, J. How efficient are Alendronate-Nano/Biomaterial combinations for Anti-Osteoporosis therapy?? An Evidence-Based review of the literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 17, 6065–6094 (2022).

Ensrud, K., Crandall, C. & Osteoporosis Ann. Intern. Med. 167, ITC17–ITC32 (2017).

Reid, I. R. & Billington, E. O. Drug therapy for osteoporosis in older adults. Lancet 399, 1080–1092 (2022).

Xiao, P. et al. Global, regional prevalence, and risk factors of osteoporosis according to the world health organization diagnostic criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 33, 2137–2153 (2022).

Dalbeth, N., Gosling, A., Gaffo, A. & Abhishek, A. Gout Lancet 397, 1843–1855 (2021).

Srivastava, A., Kaze, A., McMullan, C., Isakova, T. & Waikar, S. Uric acid and the risks of kidney failure and death in individuals with CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 71, 362–370 (2018).

Saito, Y., Tanaka, A., Node, K. & Kobayashi, Y. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease: A clinical review. J. Cardiol. 78, 51–57 (2021).

Oda, E., Kawai, R., Sukumaran, V. & Watanabe, K. Uric acid is positively associated with metabolic syndrome but negatively associated with diabetes in Japanese men. Intern. Med. 48, 1785–1791 (2009).

Yan, D. et al. Association of serum uric acid levels with osteoporosis and bone turnover markers in a Chinese population. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 39, 626–632 (2018).

Cao, G. & Prior, R. L. Comparison of different analytical methods for assessing total antioxidant capacity of human serum. Clin. Chem. 44, 1309–1315 (1998).

Ames, B. N., Cathcart, R., Schwiers, E. & Hochstein, P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 78, 6858–6862 (1981).

Reid, I. R., Ames, R. W., Evans, M. C., Sharpe, S. J. & Gamble, G. D. Determinants of the rate of bone loss in normal postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 79, 950–954 (1994).

Felson, D. T., Zhang, Y., Hannan, M. T. & Anderson, J. J. Effects of weight and body mass index on bone mineral density in men and women: the Framingham study. J. Bone Min. Res. 8, 567–573 (1993).

Chiu, C. et al. The association between body mass index and osteoporosis in a Taiwanese population: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Sci. Rep. 14, 8509 (2024).

De Laet, C. et al. Body mass index as a predictor of fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 16, 1330–1338 (2005).

Liu, D., Jiang, L., Gan, L., Su, Y. & Li, F. Association between serum uric acid level and body mass index in sex and age-specific groups in Southwestern China. Endocr. Pract. 25, 438–445 (2019).

Rathmann, W., Haastert, B., Icks, A., Giani, G. & Roseman, J. Ten-year change in serum uric acid and its relation to changes in other metabolic risk factors in young black and white adults: the CARDIA study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 22, 439–445 (2007).

Kanis, J. A. Diagnosis of osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 7 (Suppl 3), S108–116 (1997).

Veronese, N. et al. Hyperuricemia protects against low bone mineral density, osteoporosis and fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 46, 920–930 (2016).

Ibrahim, W., Younes, N., Shi, Z. & Abu-Madi, M. Serum uric acid level is positively associated with higher bone mineral density at multiple skeletal sites among healthy Qataris. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 653685 (2021).

Yao, X., Chen, L., Xu, H. & Zhu, Z. The Association between Serum Uric Acid and Bone Mineral Density in Older Adults. Int J Endocrinol. 3082318 (2020). (2020).

Xu, M. et al. Positive association between serum uric acid and bone mineral density in Chinese type 2 diabetes mellitus stratified by gender and BMI. J. Bone Min. Metab. 36, 609–619 (2018).

Xu, M. et al. Association between serum uric acid levels and bone mineral density in patients with osteoporosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.. 24, 306 (2023).

Bonaccorsi, G. et al. Changes in adipose tissue distribution and association between uric acid and bone health during menopause transition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 6321 (2019).

Muka, T. et al. The influence of serum uric acid on bone mineral density, hip geometry, and fracture risk: the Rotterdam study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101, 1113–1122 (2016).

Li, X., Li, L., Yang, L., Yang, J. & Lu, H. No association between serum uric acid and lumbar spine bone mineral density in US adult males: a cross sectional study. Sci. Rep. 11, 15588 (2021).

Zhao, X., Yu, X. & Zhang, X. Association between Uric Acid and Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in China: A Cross-Sectional Inpatient Study. J. Diabetes Res. 3982831 (2020). (2020).

Feng, X. & McDonald, J. M. Disorders of bone remodeling. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 6, 121–145 (2011).

Gkastaris, K., Goulis, D., Potoupnis, M., Anastasilakis, A. & Kapetanos, G. Obesity, osteoporosis and bone metabolism. J. Musculoskel. Neuronal Interact. 20, 372 (2020).

Glantzounis, G. K., Tsimoyiannis, E. C., Kappas, A. M. & Galaris, D. A. Uric acid and oxidative stress. Curr. Pharm. Des. 11, 4145–4151 (2005).

Lee, H. S. & Hwang, J. S. Impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus and antidiabetic medications on bone metabolism. Curr. Diab Rep. 20, 78 (2020).

Ahn, S. et al. Higher serum uric acid is associated with higher bone mass, lower bone turnover, and lower prevalence of vertebral fracture in healthy postmenopausal women. Osteoporosis International: J. Established as Result Cooperation between Eur. Foundation Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Foundation USA 24, (2013).

Kaushal, N., Vohora, D., Jalali, R. & Jha, S. Review of the literature examining the association of serum uric acid with osteoporosis and mechanistic insights into its effect on bone metabolism. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord Drug Targets. 19, 259–273 (2019).

Dalle Carbonare, L., Innamorati, G. & Valenti, M. T. Transcription factor Runx2 and its application to bone tissue engineering. Stem Cell. Rev. Rep. 8, 891–897 (2012).

Li, H. Z. et al. Uric acid promotes osteogenic differentiation and inhibits adipogenic differentiation of human bone mesenchymal stem cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 29, 382–387 (2015).

Hu, L., Chen, W., Qian, A. & Li, Y. P. Wnt/β-catenin signaling components and mechanisms in bone formation, homeostasis, and disease. Bone Res. 12, 39 (2024).

Gómez-de-Tejada-Romero, M. et al. Influence of serum uric acid on bone and fracture risk in postmenopausal women. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 36, 156 (2024).

Pirro, M. et al. Uric acid and bone mineral density in postmenopausal osteoporotic women: the link Lies within the fat. Osteoporos. Int. 28, 973–981 (2017).

Mazocco, L. & Chagas, P. Association between body mass index and osteoporosis in women from Northwestern Rio Grande do Sul. Rev. Bras. Reumatol Engl. Ed. 57, 299–305 (2017).

Balasubramanian, A. et al. Risk of subsequent fracture after prior fracture among older women. Osteoporos. Int. 30, 79–92 (2019).

Konradsen, S., Ag, H., Lindberg, F., Hexeberg, S. & Jorde, R. Serum 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D is inversely associated with body mass index. Eur. J. Nutr. 47, 87–91 (2008).

Prince, R. L. et al. Prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. A comparative study of exercise, calcium supplementation, and hormone-replacement therapy. N Engl. J. Med. 325, 1189–1195 (1991).

Zhao, L. et al. Correlation of obesity and osteoporosis: effect of fat mass on the determination of osteoporosis. J. Bone Min. Res. 23, 17–29 (2008).

Zhu, L. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is a sensitive marker of osteoporosis in haemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional observational study. BMC Nephrol. 22, 183 (2021).

Yang, J., Hong, N., Shim, J. S., Rhee, Y. & Kim, H. C. Association of insulin resistance with lower bone volume and strength index of the proximal femur in nondiabetic postmenopausal women. J. Bone Metab. 25, 123–132 (2018).

Fu, Y. H., Liu, W. J., Lee, C. L. & Wang, J. S. Associations of insulin resistance and insulin secretion with bone mineral density and osteoporosis in a general population. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 971960 (2022).

Jarrell, L. Osteoporosis management in primary care. Nurse Pract. 48, 11–20 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.X wrote the main manuscript text, L.L researched ideas are formulated and Z.G reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiu, Z., Gao, Z. & Luo, L. The triangular relationship of serum uric acid, osteoporosis or osteopenia, and body mass index for men and postmenopausal women. Sci Rep 15, 24859 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10191-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10191-y