Abstract

This study aims to explore the pharmacological mechanism of Brucea javanica (BJ) in treating multiple myeloma (MM) through network pharmacology and validate this mechanism via in vitro experiments. Active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) of BJ and their potential targets were identified, along with MM-related targets. By plotting protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, hub genes responsible for BJ in treating MM were identified and subjected to molecular docking. In MM cell lines H929 and U266, regulatory effects of BJ and luteolin (the major compound of BJ) on the behaviors of MM cells were examined. BJ extract exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity against MM cells, with IC50 values of 5.03 µL/mL (48 h) for H929, and 1.06 µL/mL (48 h) for U266. Network pharmacology identified 14 APIs and 11 hub genes, with molecular docking confirming strong binding affinity between luteolin and TNF (-8.001 kcal/mol). 48-hour luteolin treatment suppressed MM cell proliferation (IC50: 84.73 µM for H929; 46.93 µM for U266), induced apoptosis (up to 53.03% and 9.22% late apoptosis in H929 and U266 at 80 µM), and arrested cell cycle at G0/G1 phase. It downregulated TNF/NF-κB pathway components, reducing mRNA levels of TNF, IL-6, and NFKB1, and protein levels of p105, p50, and p65. TNF-α secretion decreased in luteolin-treated cells to 10.62% in H929 cells and 67.25% in U266 cells. This study demonstrates that BJ inhibits MM progression primarily via suppression of the TNF/NF-κB signaling pathway, with luteolin as a pivotal bioactive compound.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM), a clonal plasma cell neoplasm, is characterized by malignant proliferation of plasma cells within the bone marrow microenvironment, clinically manifesting as anemia, osteolytic lesions, renal impairment, and hypercalcemia1. While contemporary therapeutic strategies—including proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib), immunomodulatory agents (lenalidomide/pomalidomide), anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies (daratumumab), autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies—have significantly improved overall survival rates2,3,4, disease relapse remains a predominant clinical challenge, occurring in > 80% of patients and substantially compromising long-term outcomes5.

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) formulations have gained increasing attention as adjuvants in oncology due to their demonstrated efficacy with favorable safety profiles6,7,8,9. Brucea javanica (BJ) (Chinese:鸦胆子/Ya-Dan-Zi) is the dried mature fruits of the Brucea javanica (L.) Merr, the Simaroubaceae plant, which are classified in Chinese materia medica as having bitter taste, cold property, and mild toxicity. Originally documented in Southeast Asian traditional medicine for parasitic disease management (e.g., malaria and trypanosomiasis) and glycemic regulation10, this botanical agent has been systematically integrated into Chinese clinical practice for treating infectious diarrheal disorders, protozoal infections, and cutaneous lesions11.Brucea javanica, acting on the liver and large intestine meridians, demonstrates heat-clearing and detoxifying properties according to Traditional Chinese Medicine theory12. It exerts anticancer effects by inhibiting cell proliferation, metastasis and angiogenesis, as well as inducing cell apoptosis and autophagy13.Recent studies confirm BJ’s inhibitory effects on multiple myeloma (MM) cancer stem cell growth and migration, as well as tumor angiogenesis14. In China, Brucea Javanica Oil made from BJ has been widely used in chemotherapy for patients with solid tumors. Brucea Javanica Oil contains many pharmaceutically active ingredients, including quassins and fatty acids15. Nevertheless, the mechanism underlying the role of BJ in treating MM remains to be fully elucidated.

Luteolin, an active monomeric compound isolated from Brucea javanica (BJ), exhibits anticancer properties against multiple human malignancies, including lung cancer, breast cancer, glioblastoma, prostate cancer, colon cancer, and pancreatic cancer16. In lung cancer, luteolin could inhibit MAPKs and NF-κB pathways17.Similarly, luteolin could inhibit PI3K-Akt and NF-κB pathways in liver cancer18. However, the anticancer effect of luteolin in MM requires further investigation.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a pleiotropic cytokine, exhibits dual functionality in oncogenesis by both promoting tumor growth, invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis. In MM, TNF-α is implicated in the production of malignant plasma cells19. It also has the potential to induce cancer cell death, through activation of signaling pathways such as NF-κB and JNK20. Hyperactive NF-κB signaling plays a pivotal role in disease progression through transcriptional activation of the secretion of various cytokines like IL-6, RANKL and Dkk1 to promote cancer cell proliferation, osteoblast inactivation, osteoclast hyperactivation and angiogenesis21,22. MM is characterized by an imbalanced cytokine system, with elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines Therefore, inhibiting inflammation is a critical treatment approach for MM23. Recent studies reveal the potential synergies between anti-inflammatory therapies and stem cell preservation strategies in hematologic malignancies24. Numerous frontline medications against MM exert a direct or indirect effect on the NF-κB signaling pathway, for example, bortezomib and corticosteroid dexamethasone. However, it is still not well understood how luteolin mediates its anticancer effects in MM.

In this study, we employed an integrated approach combining network pharmacology and molecular docking to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying BJ therapeutic effects in MM. Our findings were further validated via in vitro experiments. By establishing a comprehensive component-target-pathway network and verifying functional outcomes, this work provides the first comprehensive evidence for BJ’s anti-MM mechanism through TNF/NF-κB signaling. These results establish a theoretical framework for both the clinical application of BJ and the development of luteolin-based targeted therapies.

Materials and methods

Collection of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and potential targets

APIs of BJ and corresponding targets were predicted in the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP, https://old.tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php) and the Encyclopedia of Traditional Chinese Medicine (ETCM, http://www.tcmip.cn/ETCM/) databases. Targets of BJ APIs were screened out according to an oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30% and a drug-likeness (DL) ≥ 0.18.

Targets of MM were obtained by searching the key words of MM in the GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and DisGeNET (https://disgenet.com/) databases. An intersection set between the targets of BJ and MM was illustrated by a Venn diagram.

Construction of a BJ-API-target network

A BJ-API-Target network was constructed by importing the APIs, their corresponding targets, and targets of MM into the Cytoscape 3.7.2. The node size was determined by the degree of connectivity.

Construction of a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

A PPI network was constructed by importing the targets of both BJ and MM into the STRING platform (https://cn.string-db.org/), and visualized by the Cytoscape 3.7.2. Disconnected nodes were hidden and minimum interaction confidence was set to 0.900 for clarity. By setting a minimum degree of 10, core targets were screened through the degree centrality (DC), closeness centrality (CC) and betweenness centrality (BC). Clusters in highly interconnected regions were identified by the Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) algorithm within Cytoscape 3.7.2.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) was performed using the clusterProfiler in an R package25. Enriched signaling pathways were identified and a compound-target-pathway network was visualized by the Cytoscape 3.7.2.

Survival analysis

Overall survival was calculated and analyzed in the Kaplan-Meier Plotter database (https://kmplot.com/analysis/), where the top 11 genes in the PPI network based on the value of degree were selected. The patient samples have been split into two groups (higher and lower expression levels), and were compared using a Kaplan-Meier survival plot. The hazard ratio with 95% confidence intervals and log- rank p value was calculated.

Molecular docking

MOL format files of chemical compounds from the TCMSP database were processed using the LigPrep to prepare a ligand library, which was then conversed into the maegz file format. The three-dimensional structures of proteins were available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/), and processed using Maestro 12.8. An Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulation (OPLS 2005) force field was employed to perform molecular docking. Glide 2.5, run in the standard-precision mode, was used for docking small molecules into proteins. A docking score was finally graded based on the energy change, and ligand interactions were visualized using PyMOL 2.5 or LigPlot+ version 2.2.

Cell culture and treatment

The MM cell line H929 (SunnCell, China) was cultured in RPMI-1640 (Zhong Qiao Xin Zhou Biotechnology, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, VivaCell Biotechnology, China), 0.05 µM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco, USA). The MM cell line U266 was kindly provided by Dr Lina Zhang (The First Hospital of Nanjing, China) and cultured in RPMI-1640 containing 15% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. The BJ extract serves as the raw material for Brucea javanica Oil Oral Emulsion (National Drug Approval Number: Z21021715), a clinically approved drug provided by Yaoda Leiyunshang Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. (Shengyang, China). According to the manufacturer’s specifications, each 1 mL of emulsion contains 0.1 mL of BJ extract, which was prepared from the dried mature fruits of BJ. For cell treatment, the BJ extract was serially diluted in complete culture medium to obtain the desired concentrations. Luteolin (HY-N0162, MedChemExpress, USA) was prepared as a 500 mM stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and stored at -20 °C until use.

CCK-8 assay

MM cells (3 × 104 cells/well) treated with BJ extract and luteolin at varying concentrations were seeded into 96-well plates, with 6 replicates per group. After 24–48 h, 10 µL CCK-8 solution (C0037, Beyotime, China) was added in each well and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. Optical density (OD) at 450 nm wavelength was recorded by microplate reader (SpectraMax iD5, Molecular Devices, USA) to calculate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) and 75% inhibitory concentration (IC75) at 24 h and 48 h.

Flow cytometry

MM cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates and induced with luteolin at varying concentrations for 24–48 h. After treatment, cells were harvested and stained using the Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (Vazyme, China). Apoptotic cell distribution (early and late apoptosis) was analyzed by a flow cytometry.

For cell cycle analysis, MM cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were similarly treated with luteolin, fixed in 70% ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide (PI) using the Cell Cycle Detection Kit (Beyotime, China).DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCanto™ II, Becton Dickinson, USA), and the percentage of cells in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases was quantified using FlowJo software v10.8.1 (FlowJo LLC, USA).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using FreeZol Reagent (R711, Vazyme, China), and its concentration and purity were measured using a NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Total RNA was then reversely transcribed into cDNA. The reaction mixture was prepared using HiScript II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (R223-01, Vazyme, China). To eliminate genomic DNA contamination, the reaction mixture was incubated at 42 °C for 2 min. Reverse transcription was performed under the following conditions: 50 °C for 15 min, 85 °C for 5 s (heat inactivation of reverse transcriptase), and final hold at 4 °C. The synthesized cDNA was immediately used for qPCR analysis.

The mRNA expression levels of TP53, CASP3, JUN, XIAP, TNF, BCL2C1, BCL2, AKT1, CCND1, IL-6, and NFKB1 were measured on a qRT-PCR platform. The q-PCR reaction system was prepared using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Q311, Vazyme, China). Amplification was performed on a real-time PCR instrument (Master Cycler 5333, Eppendorf, Germany) using the manufacturer-recommended thermal profile. Relative gene expression levels were quantified using the comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) method with normalization to endogenous reference genes (GAPDH and ACTB).

Western blot

Following treatment, cells were centrifuged to collect and washed once with PBS. Then cell pellets were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors on ice for 30 min. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation (12,000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C), and supernatants were collected for protein quantification using a BCA assay kit (P0012; Beyotime Biotechnology, China). Protein concentrations were normalized, mixed with 6× Laemmli loading buffer, and denatured at 95 °C for 10 min.

Proteins were resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (0.22 μm; Millipore, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: NF-κB p65 (10745-1-AP, Proteintech, China), NF-κB p105/p50 (14220-1-AP, Proteintech, China), TNF-α (14220-1-AP, Proteintech, China), GAPDH (10494-1-AP, Proteintech, China), β-actin (66009-1-Ig, Proteintech, China). After washing with TBST, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (ABclone, China) for 2 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (P0018, Beyotime, China) and imaged with a chemiluminescence detection system (Touch Imager, e-BLOT, China). Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ software (v1.53; National Institutes of Health, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

MM cells induced with luteolin at varying concentrations for 24–48 h were implanted into 12-well plates at a density of 6 × 105 cells/mL. Levels of TNF-α in supernatant were measured using commercial kits (Elabscience, China).

Statistical analysis

Data from triplicate experiments were expressed as mean and standard error of the mean (SEM), and analyzed by GraphPad Prism version 8.4.0. Comparisons between groups were performed through the t-test. Differences in the OS between groups were analyzed by the log-rank test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

BJ extract inhibits the proliferation of MM cells in vitro

H929 and U266 cells were treated with BJ extract (2.5 µL/mL, 5 µL/mL, 10 µL/mL, 20 µL/mL, 30 µL/mL, and 40 µL/mL) for 24 h and 48 h. The viability of H929 cells decreased in a concentration-dependent manner, with IC50 values of 6.58 ± 0.25 µL/mL at 24 h and 5.03 ± 0.21 µL/mL at 48 h (Fig. 1A,B). Similarly, U266 cells exhibited a comparable dose-dependent reduction in viability but demonstrated greater sensitivity, with the IC50 at 24 h and 48 h of 2.13 ± 0.45 µL/mL and 1.06 ± 0.29 µL/mL, respectively (Fig. 1C, D).

BJ extract inhibits the proliferation of MM in vitro. (A, B) Cell viability of H929 cells after 24 h (A) and 48 h (B) induction of BJ extract at the concentrations of 2.5 µL/mL, 5 µL/mL, 10 µL/mL, 20 µL/mL, 30 µL/mL, and 40 µL/mL. (C, D) Cell viability of U266 cells after 24 h (C) and 48 h (D) induction of BJ extract at the concentrations of 2.5 µL/mL, 5 µL/mL, 10 µL/mL, 20 µL/mL, 30 µL/mL, and 40 µL/mL. The bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of 6 independent replicate experiments.

Targets of BJ and MM

A total of 14 APIs and their 101 targets with OB ≥ 30% and DL ≥ 0.18 were screened (Table 1). Meanwhile, 5,033 targets of MM were acquired from the GeneCards and DisGeNET databases. By intersecting targets of BJ and MM, 65 overlapped targets were obtained (Table 2) and visualized in Fig. 2A. The BJ-API-Target network highlighted key APIs of BJ that were closely interacted with MM, including luteolin, beta-sitosterol and bruceine C (Fig. 2B).

Overlapped targets between BJ and MM. (A) A Venn diagram visualizing the intersection targets between BJ and MM. (B) A BJ-API-Target network, in which the red node is BJ, yellow nodes are core APIs of BJ, and blue nodes are targets of BJ’s APIs. The edge between nodes represents the connectivity, and the node size denotes the degree of connectivity.

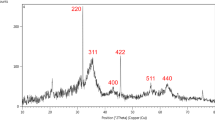

A PPI network

A PPI network containing 29 nodes and 113 edges with a DC greater than 6 was visualized (Fig. 3A). To illustrate hub genes responsible for the therapeutic efficacy of BJ on MM, we further screened 6 nodes and 10 edges meeting the following requirements: DC > 12, BC > 0.0074 and CC > 0.4030. Six targets with the greatest performance were finally identified, namely TNF, IL-6, JUN, BCL2, CASP3 and AKT1, conjured up 55 nodes and 177 edges in the PPI network (Fig. 3B). The top three hub genes were TP53, TNF and CASP3 (Fig. 3C), and the DC values of the top 11 hub genes are shown in Fig. 3D. Moreover, three highly connected subnetworks (cluster 1, 2 and 3) were identified using the MCODE algorithm within Cytoscape 3.7.2 (Fig. 3E).

The PPI topological networks. (A) A PPI network visualizing 29 nodes and 113 edges initially with DC > 6, and further visualizing 6 nodes and 10 edges with DC > 12, BC > 0.0074 and CC > 0.4030. (B) A PPI network involving the 6 hub genes. (C) PPI networks involving the top 3 hub genes. (D) The DC values of the top 11 hub genes. (E) Three highly connected clusters of hub genes.

KEGG pathway analysis

The top 20 signaling pathways (false discovery rate < 0.05) significantly enriched in BJ targets in treating MM are listed in Fig. 4A, including the apoptosis pathway, TNF signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, all of which participated in the regulation of cell apoptosis and immunity. A Sankey diagram of the KEGG pathway visualized how the targets flow through a biological pathway (Fig. 4B). An API-Target-Pathway network was then created, in which, AKT1, NFKB1, MAPK1, RELA, TP53, NFKBIA, BAX, CASP3, CCND1, CDKN1A, CASP9, CDK4, CASP8, RB1, TNF, BCL2, JUN, and IL-6 were enriched in more than 10 pathways (Fig. 4C).

Overall survival of MM associated with the hub genes of BJ

To investigate the prognosis of MM after the treatment of BJ, the overall survival (OS) of MM associated with the 11 hub genes in the PPI network was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier plotter. Notably, TP53, CASP3, IL-6, XIAP, BCL2, BCL2L1, CCND1, NFKB1, and JUN significantly influenced the OS of MM (P < 0.05). The expression levels of TNF and AKT1 did not correlate with the prognosis of MM (P > 0.05, Fig. 5).

Molecular docking

A heatmap visualized the docking score between the top 11 hub genes and 14 APIs of BJ (Fig. 6). Among them, proteins encoded by TNF, AKT1, BCL2L1, TP53 and BCL2 had a larger negative docking score with the APIs, suggesting their greater involvement in the treatment of MM. Previous evidence has highlighted the association of TNF expression with disease severity and symptom burden of MM26,27,28. Here, we mainly analyzed the molecular docking of TNF with the APIs of BJ, showing the highest binding affinities with yadanzioside J (-8.099 kcal/mol), bruceoside B (-8.027 kcal/mol), and luteolin (-8.001 kcal/mol). The binding mode of TNF with them was analyzed by PyMOL 2.5 and LigPlot+ version 2.2 (Fig. 6). Briefly, hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions were predominantly responsible for the binding of TNF with yadanzioside J, bruceoside B and luteolin. Yadanzioside J bonded with TNF residues Lys 11 (B), Tyr 59 (C), Leu 57 (C), and Ala 14 (C), and bruceoside B bonded with Lys 11 (B), Tyr 59 (C), Leu 57 (A), and Ser 9 (C) residues. Luteolin formed two hydrogen bonds with key residues of TNF Tyr 119 (A) and Val 16 (C).

Luteolin is an effective component of BJ in inhibiting MM cells proliferation

Given the high binding affinity between luteolin and TNF, we further validated its influence on the behaviors of MM cells in vitro. H929 (0 µM, 20 µM, 40 µM, 60 µM, 80 µM, 120 µM, 160 µM, and 320 µM) and U266 cells (0 µM, 20 µM, 40 µM, 60 µM, 80 µM, 160 µM, 320 µM, and 640 µM) were induced with luteolin at varied concentrations for 24–48 h. Luteolin significantly inhibited the viability of H929 cells in a dose-dependent manner, with IC50 at 24 h and 48 h of 107.90 ± 4.58 µM and 84.73 ± 4.88 µM. The corresponding IC75 values were 193.00 ± 12.60 µM (24 h) and 173.90 ± 9.60 µM (48 h) (Fig. 7A,B). Similarly, U266 cells showed more pronounced sensitivity, with the IC50 at 24 h and 48 h of 69.55 ± 3.67 µM and 46.93 ± 2.30 µM, respectively. IC75 values for U266 cells were 175.53 ± 15.27 µM (24 h) and 113.53 ± 9.04 µM (48 h) (Fig. 7C,D).

Luteolin inhibits the proliferation of MM in vitro. (A, B) Cell viability of H929 cells after 24 h (A) and 48 h (B) induction with luteolin at concentrations of 0 µM, 20 µM, 40 µM, 60 µM, 80 µM, 120 µM, 160 µM, and 320 µM. (C, D) Cell viability of U266 cells after 24 h (A) and 48 h (B) induction with luteolin at concentrations of 0 µM, 20 µM, 40 µM, 60 µM, 80 µM, 160 µM, 320 µM, and 640 µM. The bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of 6 independent replicate experiments.

Luteolin promoted apoptosis in MM cells

We used flow cytometry to detect the effect of luteolin on the apoptosis of MM cells. As shown in Fig. 8A, treating with Luteolin for 24–48 h significantly increased apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner in H929 cells (0 µM, 20 µM, 80 µM and 120 µM) and U266 cells (0 µM, 20 µM, 40 µM and 80 µM). In H929 cells, 48 h treatment with 80 µM luteolin induced 4.05 ± 0.08% early apoptosis (Annexin V⁺/PI⁻) and 53.03 ± 1.13% late apoptosis (Annexin V⁺/PI⁺). In contrast, U266 cells treated with 80 µM luteolin for 48 h exhibited 9.61 ± 0.07% early apoptosis and 9.22 ± 0.15% late apoptosis. Notably, luteolin mainly increased the proportion of H929 cells in the late phase of apoptosis (Fig. 8B), whereas it increased both early and late apoptosis in U266 cells (Fig. 8C).

Luteolin induces the apoptosis of MM in vitro. (A) Arrest of luteolin-induced H929 (left) and U266 cells (right) in different stages of apoptosis. (B) Rates of apoptotic H929 cells induced by luteolin at concentrations of 0 µM, 20 µM, 80 µM and 120 µM for 24 h and 48 h. (C) Rates of apoptotic U266 cells induced with luteolin at concentrations of 0 µM, 20 µM, 40 µM and 80 µM for 24 h and 48 h. The bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of three independent replicate experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. 0 µM (early apoptosis). +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 vs. 0 µM (late apoptosis).

Luteolin arrested cell cycle in MM cells

As is shown in Fig. 9, luteolin treatment (0 µM, 20 µM, 80 µM, and 120 µM for H929; 0 µM, 20 µM, 40 µM and 80 µM for U266) dose-dependently altered cell cycle distribution in MM cells. In H929 cells, luteolin reduced the proportion of cells in the G2/M phase and increased accumulation in the G0/G1 phase, with more pronounced effects after 48 h (Fig. 9B). After treatment with 80 µM luteolin for 48 h, the proportion of G2/M phase cells decreased to 4.74 ± 0.39%, compared to 0 µM group (30.57 ± 1.44%). The proportion of G0/G1 phase cells increased to 81.60 ± 1.45%, compared to 0 µM group (40.10 ± 1.73%).

In U266 cells, luteolin exhibited stronger cell cycle inhibitory effects (Fig. 9C). Even low-dose luteolin (80 µM, 24 h) significantly disrupted cell cycle progression. After treatment with 80 µM luteolin for 48 h, the proportion of G2/M phase cells decreased to 6.77 ± 0.15%, compared to 0 µM group (17.13 ± 1.16%). The proportion of G0/G1 phase cells increased to 67.60 ± 1.45%, compared to 0 µM group (66.50 ± 0.29%).

Luteolin arrests cell cycle progression in MM in vitro. (A) Distribution of luteolin-induced H929 (left) and U266 cells (right) in each phase of cell cycle. (B) Proportions of H929 cells in the G2/M, S and G0/G1 phases after luteolin treatment at concentrations of 0 µM, 20 µM, 80 µM and 120 µM for 24 h and 48 h. (C) Proportions of U266 cells in the G2/M, S and G0/G1 phases after luteolin treatment at concentrations of 0 µM, 20 µM, 40 µM and 80 µM for 24 h and 48 h. The bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of three independent replicate experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. 0 µM (G0/G1). +P < 0.05 ,++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 vs. 0 µM (S), #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. 0 µM (G2/M).

Luteolin mediates inflammation, apoptosis and immune response in MM in vitro

We examined mRNA levels of 11 hub genes in MM cells treated with luteolin at the corresponding IC50 concentrations for 24–48 h. As expected, luteolin significantly upregulated mRNA levels of TP53, CASP3 and JUN at 24 h and 48 h, but downregulated those of TNF and IL-6 at 24 h and 48 h, and NFKB1 at 24 h in H929 cells (Fig. 10A). Similarly, luteolin significantly upregulated mRNA levels of TP53 and JUN at 24 h, CAPS3 at 24 h and 48 h, but downregulated TNF at 24 h and 48 h, and CCND1, IL-6 and NFKB1 at 48 h in U266 cells (Fig. 10B). These findings collectively demonstrate that luteolin exerts therapeutic effects on MM through modulation of inflammation, apoptosis, and cell cycle pathways.

Luteolin mediates mRNA levels of markers associated with inflammation and apoptosis in MM cells. (A, B). The mRNA levels of TP53, CAPS3, JUN, XIAP, TNF, BCL2C1, BCL2, AKT1, CCND1, IL-6 and NFKB1 in luteolin-induced H929 cells (A) and U266 cells (B) at 24 h and 48 h. The bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of three independent replicate experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Con group.

Luteolin inhibited the expression levels of inflammation-related proteins in MM cells

After 24–48 h treatment of luteolin in IC50 values, protein levels of molecules associated with inflammation and immune response (p105, p50, p65 and TNF-α) were detected. In both H929 and U266 cells, p105, p50 and p65 were significantly downregulated by luteolin. Luteolin also downregulated the protein level of TNF-α, though not significantly. (Fig. 11A,B)

Luteolin mediates protein levels of markers associated with inflammation and immune response in MM cells. (A, B) Protein levels of p105, p50, p65 and TNF-α in luteolin-induced H929 (A) and U266 cells (B) at 24 h and 48 h (left) and semi-quantitative analyses (right). The bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM of three independent replicate experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Con group. Original blot are presented in Supplementary material 1.

Luteolin inhibits the secretion of TNF-α in MM cells in vitro

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) revealed that luteolin dose- and time-dependently inhibited TNF-α secretion in both cell lines (Fig. 12A,B). In H929 cells, 48 h treatment with IC50 and IC75 concentrations reduced TNF-α levels to 10.62 ± 0.49% and 5.51 ± 0.37% of control (0 group), respectively. U266 cells exhibited a reduction to 67.25 ± 1.40% at IC₅₀, with further suppression to 8.07 ± 0.47% under IC₇₅ treatment.

Discussion

Network pharmacology has emerged as a promising approach for cancer drug discovery, addressing the limitations of single-target interventions29. Also, it aligns well with traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) principles, offering insights into TCM mechanisms and herb combinations. Drug-target prediction technologies play a crucial role in efficiently identifying interactions between numerous compounds and target proteins30. Modern analytical tools have unveiled major constituents and pharmacological actions of BJ. Here, we clarified that luteolin, the API of BJ, may play an anti-MM role by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway and reducing the production of TNF-α to alleviate inflammation, by integrating network pharmacology and molecular docking, and validated this mechanism using in vitro experiments.

First, we demonstrated that the BJ extract inhibits MM proliferation. Then, using the network pharmacology, we identified 14 APIs of BJ, including beta-sitosterol, luteolin, bruceosides, brusatol, yadanziosides, yadanziolide, and bruceine. By predicting the targets of MM and plotting PPI networks, 11 hub genes were finally identified to correlate with the OS of MM, including TNF, TP53, CASP3, IL-6, AKT1, XIAP, BCL2, BCL2L1, CCND1, NFKB1, and JUN. Molecular docking showed that the 14 APIs of BJ exhibited high binding affinities with TNF, TP53 and BCL2 (<-5 kcal/mol). Notably, TNF is more prone to binding with APIs of BJ (yadanzioside J, bruceoside B and luteolin). As a messenger produced by the immune system, TNF is well known for the regulatory role in inflammatory diseases and is a cytokine necessary for the expansion and maintenance of MM cells31. Preclinical studies demonstrated that TNF-α-neutralizing antibodies and infliximab can suppress MM cell proliferation and increase sensitivity to chemotherapy agents like melphalan32. Consistent with the established link between MM and inflammation33,34, our analysis confirmed TNF-mediated inflammatory modulation as a therapeutic mechanism of BJ. Among the three APIs with the highest binding affinity to TNF, yadanzioside J and bruceoside B lack robust anticancer characterization, whereas luteolin demonstrates broad antitumor activity via apoptosis induction, proliferation/metastasis suppression, and angiogenesis inhibition35, targeting pathways such as PI3K/Akt, NF-κB, p53, and apoptosis36.

We therefore focused on luteolin’s anti-inflammatory potential in MM. In vitro, luteolin dose-dependently inhibited proliferation, induced apoptosis, and arrested cell cycle progression in H929 and U266 cells. Notably, luteolin triggered apoptosis in both cell lines, yet with distinct patterns: U266 exhibited a comparable proportion of early and late apoptosis (9.61% of early apoptosis and 9.22% of late apoptosis at 80 µM, 48 h) compared to H929 (4.05% of early apoptosis and 53.03% of late apoptosis at 80 µM, 48 h). This disparity might reflect differences in baseline apoptotic thresholds or the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g., BCL2, XIAP), though BCL2 and XIAP mRNA levels remained unchanged in U266. Similar disparities were reported: after herbal drug Habb-e-asgandh treatment, U266 cells showed a higher proportion of early apoptosis37, and after TAK-733 (a MEK allosteric site inhibitor) treatment, U266 cells showed a closer proportion of early and late apoptosis, compared with H929 cells38. We speculate that the mechanism of action of luteolin on U266 may not depend on the apoptosis pathway, but rather through senescence, autophagy-dependent cell death, or pyroptosis39.

We further mined the molecular mechanism of luteolin and BJ in treating MM. The expression levels of 11 hub genes in luteolin treated MM cells were examined. Interestingly, TP53, CASP3 and JUN were significantly upregulated, while TNF, IL-6 and NFKB1 were significantly downregulated. It suggested that luteolin may exert its anti-MM activity by reducing the inflammation of MM cells.

Among the downstream pathway of TNF, researches mainly focus on NF-κB, JNK, p38MAPK, and caspase cascades. Research shows mutations in NF-κB pathway components are present in at least 17% of primary MM tumors and 42% of MM cell lines40. Therefore, we examined the expression of major proteins in the NF-κB pathway in MM cells after luteolin treatment. It showed that protein levels of p105, p50 and p65, were significantly downregulated by luteolin treatment, indicating that luteolin can inhibit the NF-κB pathway. Molecular docking confirmed strong binding between luteolin and TNF (-8.001 kcal/mol), with hydrogen bonded at Tyr119 and Val16, residued critical for TNF’s receptor-binding interface. This interaction may disrupt TNF-TNFR1 complex formation, thereby attenuating downstream NF-κB activation. Notably, the lack of AKT1 survival correlation and the unchanged mRNA level of AKT1 suggested that luteolin’s anti-MM effects are predominantly TNF/NF-κB-driven, contrasting with its PI3K/AKT inhibition reported in other cancers. Similarly, in breast cancer studies, luteolin was found to affect cell survival signaling by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway41. It was also found in studies of gliobalstoma and liver cancer that luteolin leads to inhibit angiogenesis, cell survival signaling, and metastasis by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway42.

Active NF-κB signaling plays a pivotal role in disease progression through transcriptional activation of the secretion of various cytokines like IL-6, TNF-α, RANKL and Dkk1 to promote cancer cell proliferation21. TNF-α is produced in MM cells which causes MM cell proliferation by inducing MM cells into the cell cycle and promoting long-term malignant plasma cell line growth43. TNF-α is released by MM cells into the bone marrow microenvironment, triggering an NF-κB-mediated increase in the expression of adhesion molecules on both MM cells and bone marrow stromal cells, leading to stronger adhesion. This enhanced binding confers resistance to apoptosis and initiates the NF-κB-driven release of IL-6, which subsequently promotes the proliferation of MM cells44. Consistently, in our study, mRNA level of both IL-6 and NFKB1 were significantly downregulated by luteolin. In our model, luteolin reduced TNF-α secretion to 10.62% (H929) and 67.25% (U266). Despite unchanged intracellular TNF-α protein levels, it may be explained by the fact that TNF-α is quickly secreted into cell supernatant, with less than 10% remaining attached to the cells over a 48 h incubation period45. Similarly, it has been reported that inhibiting the ERK pathway with MEK inhibitors can restore the sensitivity of TNF receptor associated factor 2 (TRAF2) KO cells to IMiD46, supporting TNF targeting to overcome MM drug resistance.

Study limitations include the lack of in vivo validation and exclusive use of pharmaceutical-grade BJ extract. The potential effect of BJ in overcoming immune dysfunction in MM patients and the underlying mechanism require further investigation. Future studies could compare the effects of crude extracts with purified components to further elucidate their individual contributions. It would also be valuable to examine potential synergies between luteolin and first-line MM therapeutics (e.g., bortezomib and lenalidomide), and to investigate whether luteolin can reverse drug resistance in MM cells by modulating NF-κB inhibition or activating apoptotic pathways. Ultimately, large-scale, multicenter clinical trials will be necessary to establish the efficacy and safety profile of BJ for MM treatment.

Conclusion

Through a study integrating network pharmacology, molecular docking and in vitro experiments, BJ proved to inhibited the progression of MM mainly through its API luteolin. By inhibiting the TNF/NF-κB signaling pathway, luteolin reduced the production of TNF-α by nearly 90% to alleviate inflammation, leading to an inhibitory effect on MM.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BJ:

-

Brucea javanica (L.) Merr

- MM:

-

Multiple myeloma

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- NF-\(\kappa\)B:

-

Nuclear factor kappa B

- APIs:

-

Active pharmaceutical ingredients

- PPI:

-

Protein-protein interaction

- OB:

-

Oral bioavailability

- DL:

-

Drug-likeness

- TCMSP:

-

Traditional Chinese medicine systems pharmacology

- ETCM:

-

Encyclopedia of traditional Chinese medicine

- CC:

-

Connective correlation

- BC:

-

Betweenness centrality

- DC:

-

Degree centrality

- MCODE:

-

Molecular complex detection

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PIs:

-

Proteasome inhibitors

- IMiDs:

-

Immunomodulatory drugs

- mAb:

-

Monoclonal antibodies

- ASCT:

-

Autologous stem cell transplantation

- CAR-T:

-

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy

- TCM:

-

Traditional Chinese medicine

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- WFO:

-

World flora online

- ECL:

-

Enhanced chemiluminescence

- PVDF:

-

Polyvinylidene fluoride

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

References

Heider, M., Nickel, K., Hogner, M. & Bassermann, F. Multiple myeloma: molecular pathogenesis and disease evolution. Oncol. Res. Treat. 44, 672–681. https://doi.org/10.1159/000520312 (2021).

van de Donk, N., Usmani, S. Z. & Yong, K. CAR T-cell therapy for multiple myeloma: state of the Art and prospects. Lancet Haematol. 8, e446–e461. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00057-0 (2021).

Goel, U., Usmani, S. & Kumar, S. Current approaches to management of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Am. J. Hematol. 97 (Suppl 1). https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26512 (2022).

Terpos, E. et al. Management of patients with multiple myeloma beyond the clinical-trial setting: Understanding the balance between efficacy, safety and tolerability, and quality of life. Blood Cancer J. 11, 40. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-021-00432-4 (2021).

Bai, Y. & Su, X. Updates to the drug-resistant mechanism of proteasome inhibitors in multiple myeloma. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 17, 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.13459 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Maintenance chemotherapy with Chinese herb medicine formulas vs. with placebo in patients with advanced Non-small cell lung Cancer after First-Line chemotherapy: A multicenter, randomized, Double-Blind trial. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 1233. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01233 (2018).

Mao, D. et al. Meta-analysis of Xihuang pill efficacy when combined with chemotherapy for treatment of breast cancer. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2019 (3502460). https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3502460 (2019).

Fang, S. et al. HERB: a high-throughput experiment- and reference-guided database of traditional Chinese medicine. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D1197–D1206. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1063 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of Gutong patch compared with NSAIDs for knee osteoarthritis: A real-world multicenter, prospective cohort study in China. Pharmacol. Res. 197, 106954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2023.106954 (2023).

Bawm, S. et al. Evaluation of Myanmar medicinal plant extracts for antitrypanosomal and cytotoxic activities. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 72, 525–528. https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.09-0508 (2010).

Huang, Y. F. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Brucea Javanica oil emulsion by suppressing NF-kappaB activation on dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 198, 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2017.01.042 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. Major constituents from Brucea Javanica and their Pharmacological actions. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 853119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.853119 (2022).

Li, K. W. et al. Brucea javanica: A review on anticancer of its Pharmacological properties and clinical researches. Phytomedicine 86, 153560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153560 (2021).

Issa, M. E., Berndt, S., Carpentier, G., Pezzuto, J. M. & Cuendet, M. Bruceantin inhibits multiple myeloma cancer stem cell proliferation. Cancer Biol. Ther. 17, 966–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384047.2016.1210737 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Enhanced gastric therapeutic effects of Brucea Javanica oil and its gastroretentive drug delivery system compared to commercial products in pharmacokinetics study. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 12, 535–544. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S155244 (2018).

Imran, M. et al. Luteolin, a flavonoid, as an anticancer agent: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 112, 108612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108612 (2019).

Ma, L. et al. Luteolin exerts an anticancer effect on NCI-H460 human non-small cell lung cancer cells through the induction of Sirt1-mediated apoptosis. Mol. Med. Rep. 12, 4196–4202. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2015.3956 (2015).

Niu, J. X., Guo, H. P., Gan, H. M., Bao, L. D. & Ren, J. J. Effect of Luteolin on gene expression in mouse H22 hepatoma cells. Genet. Mol. Res. 14, 14448–14456. https://doi.org/10.4238/2015.November.18.7 (2015).

Neben, K. et al. Polymorphisms of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene promoter predict for outcome after thalidomide therapy in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 100, 2263–2265 (2002).

Manohar, S. M. At the crossroads of TNF alpha signaling and Cancer. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 17, e060923220758. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874467217666230908111754 (2024).

Yu, H., Lin, L., Zhang, Z., Zhang, H. & Hu, H. Targeting NF-kappaB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 5, 209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00312-6 (2020).

Hu, M. et al. IL-1beta-induced NF-kappaB activation down-regulates miR-506 expression to promotes osteosarcoma cell growth through JAG1. Biomed. Pharmacother. 95, 1147–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.120 (2017).

Musolino, C. et al. Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory equilibrium, proliferative and antiproliferative balance: the role of cytokines in multiple myeloma. Mediators Inflamm. 2017 (1852517). https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1852517 (2017).

Zhou, C. et al. Nynrin preserves hematopoietic stem cell function by inhibiting the mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening. Cell. Stem Cell. 31, 1359–1375e1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2024.06.007 (2024).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Kawano, Y. et al. Targeting the bone marrow microenvironment in multiple myeloma. Immunol. Rev. 263, 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12233 (2015).

Jurisic, V. & Colovic, M. Correlation of Sera TNF-alpha with percentage of bone marrow plasma cells, LDH, beta2-microglobulin, and clinical stage in multiple myeloma. Med. Oncol. 19, 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1385/MO:19:3 (2002).

Wang, X. S. et al. Longitudinal analysis of patient-reported symptoms post-autologous stem cell transplant and their relationship to inflammation in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk. Lymphoma. 56, 1335–1341. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2014.956313 (2015).

Poornima, P., Kumar, J. D., Zhao, Q., Blunder, M. & Efferth, T. Network Pharmacology of cancer: from Understanding of complex interactomes to the design of multi-target specific therapeutics from nature. Pharmacol. Res. 111, 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.06.018 (2016).

Li, L. et al. Network pharmacology: a bright guiding light on the way to explore the personalized precise medication of traditional Chinese medicine. Chin. Med. 18, 146. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13020-023-00853-2 (2023).

Jang, D. I. et al. The role of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) in autoimmune disease and current TNF-alpha inhibitors in therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052719 (2021).

Tsubaki, M. et al. Inhibition of the tumour necrosis factor-alpha autocrine loop enhances the sensitivity of multiple myeloma cells to anticancer drugs. Eur. J. Cancer. 49, 3708–3717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2013.07.010 (2013).

de Jong, M. M. E. et al. The multiple myeloma microenvironment is defined by an inflammatory stromal cell landscape. Nat. Immunol. 22, 769–780. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-021-00931-3 (2021).

Wang, Q., Shi, Q., Lu, J., Wang, Z. & Hou, J. Causal relationships between inflammatory factors and multiple myeloma: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Cancer. 151, 1750–1759. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34214 (2022).

Cetinkaya, M. & Baran, Y. Therapeutic potential of luteolin on cancer. Vaccines (Basel) 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030554 (2023).

Rauf, A. et al. Revisiting luteolin: an updated review on its anticancer potential. Heliyon 10, e26701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26701 (2024).

Kapoor, S., Gupta, N. & Sharma, A. A. Polyherbal Ashwagandha formulation exhibits adjunctive antitumor efficacy against U266 myeloma cells by Multi-Strategic cytotoxic effects: an experimental approach. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 24, 3705–3714. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2023.24.11.3705 (2023).

de la Puente, P. et al. MEK inhibitor, TAK-733 reduces proliferation, affects cell cycle and apoptosis, and synergizes with other targeted therapies in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 6, e399. https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2016.7 (2016).

Wang, X., Hua, P., He, C. & Chen, M. Non-apoptotic cell death-based cancer therapy: molecular mechanism, Pharmacological modulators, and nanomedicine. Acta Pharm. Sin B. 12, 3567–3593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.03.020 (2022).

Vrabel, D., Pour, L. & Sevcikova, S. The impact of NF-kappaB signaling on pathogenesis and current treatment strategies in multiple myeloma. Blood Rev. 34, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2018.11.003 (2019).

Jeon, Y. W., Ahn, Y. E., Chung, W. S., Choi, H. J. & Suh, Y. J. Synergistic effect between celecoxib and Luteolin is dependent on Estrogen receptor in human breast cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 36, 6349–6359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-015-3322-5 (2015).

Zhou, Q. et al. Luteolin inhibits invasion of prostate cancer PC3 cells through E-cadherin. Mol. Cancer Ther. 8, 1684–1691. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0191 (2009).

Jourdan, M. et al. Tumor necrosis factor is a survival and proliferation factor for human myeloma cells. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 10, 65–70 (1999).

Mitsiades, C. S. et al. Activation of NF-kappaB and upregulation of intracellular anti-apoptotic proteins via the IGF-1/Akt signaling in human multiple myeloma cells: therapeutic implications. Oncogene 21, 5673–5683. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1205664 (2002).

Lonnemann, G. et al. Differences in the synthesis and kinetics of release of Interleukin 1 alpha, Interleukin 1 beta and tumor necrosis factor from human mononuclear cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 19, 1531–1536. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.1830190903 (1989).

Liu, J. et al. ERK signaling mediates resistance to Immunomodulatory drugs in the bone marrow microenvironment. Sci. Adv. 7 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abg2697 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by Nanjing Second Hospital Talent Promotion Project (No. RCMS232013); Geriatric Health Research Project of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission (No. LKM2022037); Key Project of Research Project of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission (No. K2023018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuan Wang: Conceptualized and designed the study, performed network pharmacology analysis and molecular docking experiments, analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript and graphical abstract. Aijia Zhang: Co-designed the study, performed Western blot and qRT-PCR experiments, validated TNF/NF-κB pathway protein and mRNA expression, contributed to data interpretation, and co-wrote the manuscript. Yang Chen: Conducted bioinformatics analyses (PPI network construction, KEGG pathway enrichment), conducted in vitro cell proliferation and apoptosis assays (CCK-8, flow cytometry), and contributed to manuscript drafting. Daoda Qi: Assisted in data collection for network pharmacology, curated MM-related targets from GeneCards and DisGeNET databases, and supported statistical analysis. Chengyi Peng: Managed cell culture and treatment protocols, optimized luteolin dosing for apoptosis and cell cycle experiments, and assisted in flow cytometry data acquisition. Zihao Liang: Conducted ELISA assays, prepared figures for the manuscript. Jingjing Guo: assisted in literature review, and formatted references.Yan Gu (Corresponding Author): Supervised the overall research direction, secured funding, interpreted results, and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Hao Li (Corresponding Author): Provided conceptual guidance, validated experimental designs, coordinated collaborations, and finalized the manuscript for submission.All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanjing Second Hospital (No. 2023-LY-ky-015).

Plant name information

Brucea javanica has been checked with WFO (2024): Brucea javanica (L.) Merr. Published on the Internet;http://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000572705. Accessed on: 28 Dec 2024’.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhang, A., Chen, Y. et al. Mechanism of Brucea javanica against multiple myeloma via TNF-NF-κB signaling. Sci Rep 15, 24311 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10271-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10271-z