Abstract

Blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) are small fruit crops native to North America but grown commercially in several countries. There has been a steady increase in consumer demand for blueberries, owing to their numerous health benefits attributable to the high content of antioxidant compounds. Despite its importance, limited genomic resources are available, hindering genetic research and improvement in blueberry. In this study, we developed novel transcriptome-derived simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers from two divergent blueberry species. We identified 64,013 SSRs from 208,286 unigenes de novo assembled from 135 million high-quality sequence reads. SSRs with mononucleotide repeat motifs were most abundant, followed by di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotide repeat motifs. The repeat motif AG/CT was most abundant (84%) compared to the other three dinucleotide repeat motifs, AC/TG, AT/TA, and CG/GC. Similarly, AAG/CTT and AAAT/ATTT were the most abundant tri- and tetra-nucleotide repeat motifs, respectively. We designed 33,179 primer pairs from 64,013 SSR motifs. Genomic coordinates of these primers were identified using a chromosome-scale reference genome sequence of diploid blueberry clone W85-20. After discarding those markers mapped with MapQ < 1, genomic positions for 19,310 markers were identified. Thirty-six SSRs differing in nucleotide repeat motifs were randomly selected for PCR optimization, characterization, and amplification in 45 diverse Vaccinium species. Thirty-four primers generated 158 alleles with an average of 4.6 alleles per locus. Genetic structure analyses revealed a high genetic differentiation among the selected species, and divided 45 accessions into two to five clusters. Furthermore, the selected SSR markers showed 88.2–97% cross-species transferability, suggesting the possibility of using these markers for various genetics and comparative genomics applications in blueberry and cranberry species. Thus, the transcriptome-derived SSR markers developed in this study could serve as a valuable resource for further genetic and evolutionary studies in Vaccinium species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blueberries (Vaccinium L. section Cyanococcus spp.) are small fruit crops native to North America but commercially grown in several countries worldwide1. Blueberries have received much attention recently due to their health benefits attributable to the high content of anthocyanins, flavonols, procyanidins, and other types of phenolic compounds, which can protect against cancer, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, and aging2. Antioxidant phenolic compounds are associated with numerous health benefits such as eye strain, prevention of macular degeneration, anticancer activity, and reduced risk of cardiovascular heart disease3,4. Due to these types of benefits, there is a steady increase in demand for blueberries.

In the Vaccinium genus, the section Cyanococcus includes multiple species5 and species hybrids of various ploidy levels6. They are widespread throughout eastern North America, striving in diverse surroundings and widening the genetic divergence among the species. Intraspecific hybridization is widespread in blueberry species and has been widely used in cultivar development since the early twentieth century7 incorporating novel traits from wild germplasm6. Natural and directed hybridization has led to complex genetic relationships among blueberry species8.

Several recent studies have used single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers to elucidate the population structure and genetic divergence among the selected blueberry species6,9,10 providing essential insights into the evolutionary trajectories important for domestication and adaptation11. However, many species did not have precise species boundaries, suggesting that some accessions may have a highly homogenous genetic background. SNPs are generally bi-allelic markers; hence, more loci are needed to obtain sufficient statistical power in population genetic analyses12. SNPs occur in genomes at a much higher frequency than SSRs and can be genotyped in high-throughput systems with a high multiplex ratio. The comparison of SNP and SSR markers for population genetic differentiation and phylogenetic analyses have shown coherent results to each other13,14,15 although some studies implied that SSRs were shown to be more efficient for genetic diversity analysis in comparative studies16. Higher per-locus information content of SSRs makes them the marker of choice for parentage and assignment studies17 and an efficient genetic tool for assessing genetic diversity and subpopulation structure18. Thus, SSRs may help resolve the unspecified boundaries to provide evolutionary insights.

SSRs are codominant, multi-allelic, and reproducible markers19 characterized by high polymorphism and, hence, widely considered very powerful and informative across the plant species. They have wide genome coverage, are transferable to other species in the genus, and are easy to use20. Due to their hypervariable nature, SSRs produce high allelic variations, even among very closely related varieties21. Genic microsatellite markers are derived from the coding regions or the 5’ and 3’ regions of mRNA. They often show a lower genetic variation than the genomic SSRs but provide higher transferability among the related species22. The genic SSRs offer valuable information on functional sequences and may help identify adaptive genetic variations23. For these reasons, genic SSRs have found broad applications in genetic analyses, such as genetic and QTL mapping, phylogenetic and population structure, marker-assisted breeding, molecular characterization of core collections, and management of germplasm collections24. Compared to other species, limited resources are available for genetic research in blueberry25.

Dominant as well as codominant markers, including random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), SSR, and expressed-sequence tag-polymerase chain reaction (EST-PCR) markers have been developed and used for analyzing genetic relationships in Vaccinium species5,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. These studies have demonstrated that multiallelic SSRs facilitate the genetic and evolutionary analyses of blueberry.

Before the availability of reference genomes, SSR markers were developed from the genomic DNA by constructing the genomic library and sequencing the clones, which was time-consuming, costly, and labour-intensive35,36. However, with the rapid development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies and the dramatic reduction of sequencing costs, it has become feasible to use whole genome sequence data for SSR marker development37. The SSR markers developed from genomic databases are categorized as genomic simple sequence repeat (gSSR) markers. In contrast, those derived from the transcriptome databases are termed as expression sequence tag–simple sequence repeat (EST-SSR) markers. Compared to gSSRs, the cost of developing EST-SSRs is lower; therefore, many EST-SSRs can be developed from transcriptome sequencing data.

EST-SSRs help to identify variation among the transcribed sequences, thereby facilitating the identification of functional candidate genes, and marker-assisted selection38. Many EST-SSRs from conserved genic regions can be amplified in other related species and thus have high cross-species transferability39,40. Such markers also act as anchors to develop high-resolution genetic maps using biparental mapping populations. Therefore, EST-SSRs have become attractive and valuable resources for the genetic breeding of important plant species41. However, few studies have reported the large-scale development of transcriptome-derived SSRs in blueberry. For instance, Wang et al.42 carried out large-scale transcriptome sequencing of 54 blueberry cultivars and developed > 26,974 SSR markers. Similarly, Rowland et al.43 developed 7,705 SSRs from the transcriptome of the commercial highbush blueberry (V. corymbosum) cultivar Bluecrop. Li et al.44 identified 8,796 SSRs from 15,457 unigenes from transcripts involved in various stages of fruit and color development in the blueberry cultivar ‘Sierra’ (V. corymbosum).

In this study, we developed SSR markers from the transcriptome data of two divergent blueberry species, V. corymbosum and V. darrowii45. We de novo assembled the short reads from the RNAseq experiment and designed an extensive collection of SSR markers, which were validated using a set of 45 diverse blueberry accessions.

Results

SSR discovery, frequency, and distribution

RNAseq of V. corymbosum and V. darrowii samples obtained more than 135 million high-quality sequence reads (> 64.9 million from V. corymbosum and > 70.3 million from V. darrowii) using the Illumina NextSeq500 system45. The summary of the RNA sequencing data is given in Table 1. These reads were de novo assembled into 208,286 unigene sequences after clustering. The average contig length ranged from 1,041 bp to 1,139 bp (Table 2). MISA software was used to identify potential microsatellites from all the 208,286 unigene sequences. A total of 95,034 (V. corymbosum) and 104,912 (V. darrowii) sequences were examined to identify SSRs. The summary of the SSRs identified using MISA software is given in Table 2.

A total of 29,634 and 34,379 SSRs were identified in V. corymbosum and V. darrowii, respectively (Table 2). Of these identified SSRs, 5,707 and 6,621 unigene sequences contained more than 1 SSR, and 2,553 and 2,941 SSRs were present in compound form in V. corymbosum and V. darrowii, respectively. Six types of repeat motifs, with significant variation in the number of each type of repeat, were found in these SSRs (Fig. 1A). Among 29,634 SSRs in V. corymbosum, SSRs with mononucleotide repeat motifs were most abundant (13,817; 47%), followed by di- (12,862; 43%), tri- (2,712, 9%), tetra (139; <1%), penta (90; <1%), and hexanucleotide (14; <1%) repeat motifs (Fig. 1A). Similarly, among 34,379 SSRs in V. darrowii, SSRs with mononucleotide repeat motifs were most abundant (16,448; 48%), followed by di- (14,682; 43%), tri- (2,949, 9%), tetra (181; <1%), penta (103; <1%), and hexanucleotide (16; <1%) repeat motifs (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

The frequency distribution of classified SSR motif with distinct tandem repeats is illustrated in Fig. 2. In the mononucleotide repeats in V. corymbosum, the dominant repeat motif was T (7,305, 53%), followed by A (6,402, 46%), C (60, < 1%) and G (50, < 1%). Similarly, in V. darrowii, the dominant repeat motif was T (8,653), followed by A (7,635), C (84, < 1%), and G (76, < 1%) (Fig. 2A). The next most abundant classified repeat motif was dinucleotide, comprising 43% of the total SSRs. The dinucleotide repeat motif AG/CT (10,863 and 12,346) was most abundant (84%) compared to the other three dinucleotide repeat motifs, AC/TG (1,213 and 1,522), AT/TA (734 and 764) and CG/GC (52 and 50) in V. corymbosum and V. darrowii, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Among trinucleotide repeat motifs, AAG/CTT was the most abundant, comprising 35% in V. corymbosum and 36% in V. darrowii. The other two following dominant trinucleotide repeat motifs were AGG/CCT (14% in V. corymbosum and 13% in V. darrowii) and ACC/GGT (13.6% in V. corymbosum and 13.1% in V. darrowii) (Fig. 2C). Similarly, in tetra-nucleotide repeat motifs, AAAT/ATTT was most abundant (30%) in both species (Fig. 2D). In contrast, in pentanucleotide repeat motifs, AAAAG/CTTTT was most abundant (24.3% in V. corymbosum and 29.7% in V. darrowii) compared to the other repeat motifs (Fig. 2E).

Primer design and identification of genomic coordinates

Primers were designed for 15,414 out of 29,634 SSR loci identified in V. corymbosum and 17,765 out of 34,379 SSR loci in V. darrowii using Primer 3 software with selected parameters. These primers were designated as Vc_SSR_1 to Vc_SSR_15414 (Vc, V. corymbosum) and Vd_SSR_1 to Vd_SSR_17765 (Vd, V. darrowii) to distinguish the markers from both the species. Primers could not be designed for the remaining SSR loci, which could be either because they did not fit the criteria considered for the primer design using Primer 3 software or due to the lack of adequate DNA sequences flanking the SSR loci in the 5’ or 3’ unigene ends.

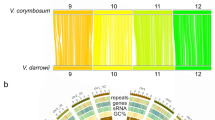

To identify the genomic coordinates, SSRs were aligned against the chromosome-scale reference genome sequence of diploid blueberry clone W85-2046. After discarding those markers mapped with MapQ < 1, genomic positions for 9,211 SSRs from V. corymbosum and 10,099 SSRs from V. darrowii were identified. The highest number of markers were identified for chromosome 2 (2,102), whereas the lowest number of markers were identified for chromosome 5 (1,298) (Fig. 3). The chromosomal distribution of the SSRs from V. darrowii and V. corymbosum is given in Fig. 3. The SSRs from both species showed great coverage across all the chromosomes. Especially at both ends of chromosomes, SSR density was higher (red regions) than the central regions (green regions). These SSRs greatly varied in terms of the number of repeats and SSR length, as shown in Fig. 1B,C. Overall, 6–8 and 10–12 ranged repeats were more abundant. Detailed information of the markers (such as chromosomal position, repeat motif, lengths, product size, and forward and reverse primer sequences) are given in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

PCR validation and assessment of genetic diversity

PCR validation of selected 36 markers was performed using 45 accessions comprising cultivars and wild relatives of blueberry and cranberry from the Vaccinium genus. Of 36 markers, 30 were amplified at 55 annealing temperatures using Promega GoTaq (Promega, USA), providing clear band patterns on agarose gels. Further optimization of the PCR program with Promega HotStart enzyme (Promega, USA) amplified another four markers. Thus, all the blueberry accessions were genotyped using 34 SSR markers, and amplicons were scored for the presence or absence of bands. The markers showed alleles in the range of 3 to 9, with a mean of 4.6 alleles/marker. The marker Vc_SSR_05524 yielded the highest number of alleles (9), and the lowest numbers of alleles (2) were obtained from markers Vd_SSR_00885, Vd_SSR_01750, Vc_SSR_01896, and Vc_SSR_01294. The average PIC values of these markers ranged from 0.15 (Vd_SSR_04972) to 0.36 (Vd_SSR_00885), with a mean of 0.24 (Table 3). The average Shannon’s information index (I*) ranged from a low of 0.33 to a high of 0.69, with a mean value of 0.50. The average Nei’s gene diversity (h2) ranged from a low of 0.18 to a high of 0.49, with a mean value of 0.34 (Table 3).

Genetic relationship and phylogenetic analysis

The allelic information of 158 loci was used for PCA and phylogenetic analysis to reveal genetic relatedness among the selected accessions. The first two principal components (PC) accounted for 24.9% and 13.5% of total variability, respectively (Fig. 4A). The population can be divided into two clusters: the first comprising all the V. macrocarpon accessions and cultivars, and the second containing all the blueberry accessions. To further differentiate the blueberry accessions in the second cluster, we performed focused PCA, which included marker data only for blueberry accessions. The first two components of the PCA accounted for 26.5% (axis X = 14.8%, and axis Y = 11.7%). All the blueberry accessions formed three clusters on the PCA plot (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table S3). Cluster 1 included all 5 V. boreale accessions, whereas Cluster 2 included all the southern highbush and northern highbush cultivars (V. corymbosum), except Pink Lemonade. The plurispecific cluster 3 included V. angustifolium, V. darrowii, V. tenellum, V. myrsinites, V. ovatum, V. reticulatum, and one V. corymbosum cultivar Pink Lemonade.

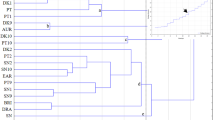

The genetic relationships of the selected 45 blueberry accessions are given in the UPGMA tree Fig. 5. The accessions were largely grouped into five clusters: (1) for V. angustifolium, (2) for V. boreale, (3) for V. darrowii, V. tenellum, V. myrsinites, V. ovatum, and V. reticulatum, (4) for northern and southern highbush cultivars (mainly comprising V. corymbosum), and (5) V. macrocarpon (cranberry accessions). The phylogenetic analysis further indicated that V. darrowii, V. tenellum, V. myrsinites, V. ovatum, and V. reticulatum did not have clear species boundaries. These results were highly consistent with those of PCA (Fig. 4).

AMOVA

Analysis of molecular variation (AMOVA) with 34 SSR markers revealed 25% variation among the populations and 75% variation within the populations (Table 4). The extent of the estimated variance of components was 6.4% among the populations and 19.6% within the populations, making 26% of the variance in all the selected Vaccinium accessions.

Cross-species transferability of the SSRs

To assess the cross-transferability, 36 SSR primers were screened in 45 accessions belonging to eight different Vaccinium species. The SSR markers showed variable extent of cross-transferability in the analyzed species. Of the 34 primer pairs, 27 markers successfully amplified in at least one accession from each selected species of the Vaccinium genus. These markers showed 100% transferability between V. corymbosum and V. darrowii and showed high polymorphism. Further, the percentage of transferability was 88.2, 85.2, and 91.2 for V. ovatum, V. reticulatum, and V. angustifolium, respectively. The markers showed 97% transferability for V. boreale, V. tenellum, and V. myrsinites. For cranberry accessions, 94% transferability was observed. The percentage of cross-transferability in different species is depicted in Fig. 6. Therefore, the transferability of SSR markers was higher in all the selected Vaccinium species.

Discussion

Blueberries have a very recent history (100 years) of domestication compared to many other fruit crops, such as apple, peach, and grape, which have been domesticated for hundreds or thousands of years. The cultivar development since then has been through phenotypic selection for large-sized fruits from wild populations. Since interspecific hybridization is widespread in blueberries, several breeding efforts have been taken to improve the blueberry cultivars through repetitive breeding and selection cycles for desired traits, mainly fruit size and quality. However, genetic improvements of blueberry for horticulturally important characteristics have been lagging due to a lack of genetic and genomic resources. Recent advancements in NGS technologies make it possible to develop transcriptome-derived SSR markers for selection and breeding purposes. Transcriptome-derived SSR markers offer many advantages, including rapid and inexpensive development and high levels of cross-taxon portability, and have the potential to facilitate evolutionary analyses in a wide variety of taxa22. Here, we report on developing large-scale transcriptome-derived nuclear SSR markers in blueberry. This study examined unigene sequences assembled from the short-read Illumina sequence read data from an RNAseq experiment45 for SSR repeat motifs, and developed a large set of transcriptome-derived SSR markers, which were validated using diverse Vaccinium species.

Using the Trinity de novo assembly program, we assembled the short read sequences from V. corymbosum and V. darrowii samples into 162,307 and 189,613 transcripts, which were then clustered into 99,315, and 109,431 unigenes, respectively. The unigenes lengths (1075 bp and 1165 bp in V. corymbosum and V. darrowii, respectively) we observed in this study were higher than the lengths previously reported by Zifkin et al.47, Li et al.44, Qi et al.48 and An et al.49 in blueberry. Moreover, our unigenes lengths were higher than those reported in previous studies on EST-SSR development using transcriptome sequence data in other crop species such as mung bean50 (Vigna radiate L.), Brassica napus51rice bean52 (Vigna umbellata L.), coriander53 (Coriandrum sativum L.). The large unigene lengths provided a higher number of repeat motifs (64,013), which is higher than identified by Rowland et al.43, Li et al.44 and Wang et al.42.

Characteristics of SSRs may vary in different species and may be associated with their adaptation and evolution54. SSRs within genes are subjected to stronger selective pressure than other genomic regions because of their functional importance55. The difference in SSR motif length and frequency and its distribution is the result of selection pressure during the evolutionary process, and hence, understanding the distribution and variability of microsatellite sequences in the genome of a given species might bring different insight into genome evolution56,57. In the present study, AG/CT dinucleotide repeat motif was found to be the predominant motif (84%), which was higher than reported previously by Boches et al.27 (69%), Rowland et al.43 (38%), Bian et al.5 and Liu et al.23 in blueberry. Such predominant nature of AG/CT repeat motif is evident in other plant species such as Triticeae species (87%), pearl millet (81%), Chinese bayberry (57%, Myrica rubra), pineapple (Ananas comosus (L.) Merr.), Citrus (26%), and sweet potato (26%, Ipomoea batatas)58,59,60,61,62.

We designed primers for 52% of the SSR loci identified from the transcriptome data of both the species, V. corymbosum and V. darrowii. Lack of adequate flanking sequences could be the most common reason for not designing primers for the remaining SSR loci. Although the unigene lengths we obtained in this study were higher than some previously reported unigene sizes, the repeat loci at the 5’ or 3’ ends might fall short of flanking sequences on either side. Nevertheless, the number of primers we designed is higher than those reported in previous SSR development studies in blueberry42,43,44. We identified chromosomal locations of 19,310 markers using a chromosome-scale reference genome of diploid blueberry W85-20. The chromosome-wide distribution and frequency of the physically mapped SSRs revealed the highest frequency on chromosome 2, whereas the lowest frequency was observed on chromosome 5. The SSRs are densely distributed across all the genomic regions of all the 12 chromosomes. The detailed information on these markers will be helpful for the selection of suitable genome-wide SSR markers across the 12 chromosomes for various genetic applications.

Genotyping of 45 diverse Vaccinium species, including blueberry and cranberry accessions and cultivars, with 45 SSR primers yielded 185 alleles. The average PIC values (0.15 to 0.36) and the number of alleles (4.6) were low to moderate compared to previous studies in blueberry23,27 in which as high as ten alleles per cultivar were observed. Further, 22 primers amplified four or more alleles (67% of the total) in this study, which is over 4 times higher than reported in Boches et al.27. AMOVA detected significant variation among and within populations, and the proportion of estimated variance was higher than reported by Tailor et al.63. The high variation and allelic polymorphism we observed could be due to the diversity of accessions that differed in sections, species, ploidy level, and type of material. The high levels of polymorphisms detected with the EST-PCR markers in blueberry are anticipated, considering that blueberry is a highly heterozygous, primarily outcrossing, and polyploid crop64. Thus, the Transcriptome-derived SSR markers developed in this study could be valuable for all species within the Cyanococcus section and Oxycoccus, including the cranberry species26,64,65. Using sensitive detection technologies such as gene analyzers or ABI sequencers may increase the number of alleles, as seen in Bian et al.5.

The overall species-wise genetic differentiation among the selected Vaccinium accessions was seen in the UPGMA tree, which is broadly consistent with PCA. In both analyses, V. macrocarpon accessions clustered separately from the blueberry species. Furthermore, the northern and southern highbush cultivars grouped together. The initial phases of blueberry domestication and breeding involved selection-based cultivar development by planting individuals with superior traits, mainly large fruit sizes selected from wild lowbush and highbush blueberry populations8. Later, southern highbush cultivars were developed through the introgression of southern species in northern V. corymbosum cultivars. Thus, V. corymbosum is involved in the selection process of southern highbush and northern highbush blueberry cultivars8 and a significant proportion of V. corymbosum background remains in southern highbush blueberry cultivars. Hence, the mixture of southern and northern highbush blueberry cultivars in the phylogenetic tree and PCA is expected and is consistent with our earlier reports9,10,11. Thus, it is apparent that the shared background in blueberry species is driving high heterozygosity in blueberry species.

Lowbush blueberry (V. angustifolium) is proposed to be an autotetraploid of V. boreale66 or an allotetraploid of V. boreale x V. pallidum or V. boreale x V. myrtilloides67,68. Several recent studies have investigated the genetic heterogeneity and relatedness of V. angustifolium within and among populations6,29,30,34 and documented genetic diversity within confined regions of majorly grown areas. Nevertheless, the founder effect on genetic diversity and selection pressure could cause a decrease in the genetic diversity among the existing lowbush accessions34. It is noted that V. boreale and V. angustifolium cohabitate across Canada’s Allegheny range, which may be the center of diversity11. In our study, V. angustifolium has lower similarity coefficients than V. boreale, which suggests that V. angustifolium had higher genetic variation than V. boreale. Previously, we observed that V. boreale (collected from Nova Scotia, Canada) is a genetically distinct outgroup compared to the other blueberry accessions11. Thus, further research involving more V. angustifolium and V. boreale accessions is needed to understand the genetic differentiation among these two species.

EST-SSR markers originate from the transcribed regions of DNA, which are the most conserved regions in the plant genomes69. They are evolutionarily conserved and have higher transferability in closely related species than the genomic SSRs70. The percentage of cross-transferability may vary depending on the number and type of accessions, and it decreases with the inclusion of more diverse accessions in the set. We found a 100% transfer rate of SSR amplification between V. darrowii and V. corymbosum, which indicates a very high rate of cross-transference, consistent with the previous reports of Boches et al.27 and Rowland et al.43. Furthermore, more than 80% of the SSRs were amplified in at least one plant accession in each species, including V. ovatum and V. reticulatum, which had only one genotype in the selected 45 accessions. The cross-transferability rate we observed in this study was higher than some of the previous reports in Vaccinium species and other plants. For instance, Boches et al.27 reported 83% cross-transferability, whereas Liu et al.23 reported 68.5–88.90% cross-transferability in 8 Vaccinium species. Therefore, the SSRs developed in this study may have potential applications in comparative genomics and evolutionary studies, such as population genetic analyses22. Since these markers originate from the heat-responsive genes, they may help identify genetic variations associated with a plant’s ability to tolerate high temperatures and potentially lead to the development of heat-resistant cultivars.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed 19,310 transcriptome-derived SSR markers from the RNA-seq data of two divergent blueberry species. The genomic positions of these markers were identified using a chromosome-scale genome sequence of blueberry clone W85-20. Thirty-four out of 36 primers showed amplification and revealed 158 alleles with a mean of 4.6 alleles per locus in 45 diverse Vaccinium species, indicating high levels of polymorphism. These alleles effectively uncovered the genetic differentiation among the selected Vaccinium species through PCA and phylogenetic analysis. Furthermore, the markers demonstrated high cross-species transferability, which suggested that the developed SSRs may have applications in related species, thereby facilitating genetic diversity and genetic relationship studies across different Vaccinium species. Thus, the novel transcriptome-derived SSR markers developed in this study are a rich, publicly available genomic resource that will aid genetic research in blueberry and related species.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

A total of 45 accessions belonging to the Vaccinium species (Table 5) were used to analyze the polymorphism of SSR markers in this study. These individuals represented the following species: V. angustifolium Ait (N = 3), V. boreale (N = 5), V. darrowii (N = 4), V. tenellum (N = 4), V. myrsinites (N = 4), V. ovatum (N = 1), V. reticulatum (N = 1), and V. corymbosum (N = 12). V. myrsinites and V. corymbosum accessions are tetraploid (2n = 4x = 48), and V. angustifolium, V. boreale, V. darrowii, V. tenellum, V. ovatum, and V. reticulatum accessions are diploid (2n = 2x = 24). The set also included 11 cranberry (V. macrocarpon) species differing in ploidy levels (2X to 6X). All the plants comprising the wild relatives of the selected species were collected across North America in the 1980s and 1990s, propagated, and maintained under greenhouse conditions at Philip E. Marucci Center for Blueberry & Cranberry Research and Extension managed by Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. We confirm that the IUCN Policy Statement includes all methods as per the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Since these are perennial plants, all the above accessions remain at Philip E. Marucci Center for Blueberry & Cranberry Research and Extension. For genomic DNA extractions, young leaves (~ 1–2 g) were collected in 15mL Nunc™ conical sterile polypropylene centrifuge tubes, transferred to the Delaware State University in dry ice, and stored at − 80 °C. The northern and southern highbush cultivars (predominantly comprising V. corymbosum species) were procured from various plant nurseries and maintained in the greenhouse at the Delaware State University.

Sample preparation and DNA extraction

Leaf tissue ranging from 100 to 120 mg was placed in a 2.0 mL Eppendorf safe-lock tube (US Scientific, USA) containing a metallic bead. The tissue samples were homogenized to fine powder using TissueLyzer-II (Qiagen, USA), and tubes were stored at − 80 °C. Genomic DNA was extracted using a modified cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) protocol. The DNA quality and concentration were checked using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The quality of each DNA sample was also verified on 1% agarose gels, stained with the SYBR™ Green I Nucleic Acid Gel Stain and visualized under UV light. Samples were stored at − 20 °C. The working concentration of DNA was adjusted to 50 ng/ml for use in marker evaluations.

SSR marker identification and primer design

Unigenes identified from the transcriptome data obtained from the RNAseq experiment involving V. darrowii and V. corymbosum plants subjected to heat stress at 45 °C were used45. The experiment details, including RNA extraction, library preparation, and RNAseq by Illumina sequencing and de novo transcriptome assembly were given in Callwood et al.45. The assembled unigenes were used to predict simple sequence repeats using the MIcroSAtellite (MISA) search engine (https://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/71). The minimum number of repeats used for selecting the EST-SSRs was ten for mononucleotide-based loci, six for dinucleotide loci, five for tri-nucleotide loci, and three for all the larger repeat types (tetra- to hexanucleotide motifs). The maximum length of sequence between two SSRs was set for 100 bp to register as a compound SSR. The primer pairs for SSR markers were designed based on sequences flanking the selected microsatellite loci using the Primer3 software72.

Identification of genomic coordinates

To identify the genomic positions, the SSR primer sequences from V. corymbosum and V. darrowii were aligned versus the chromosome-scale genome sequence of diploid blueberry clone W85-2046 using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA, http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/bwa.shtml) considering first the ALN and then the SAMSE options for each set, independently. The resulting SAM file was then filtered using SAMTOOLS73 for the mapping quality of > = one, and the unique mapping SSR sequences were retained. The mapping result for each set was used for the downstream analysis.

PCR optimization and validation of SSR markers

From the designed markers, 36 SSRs (three markers per chromosome) were selected for primer synthesis and validation using 45 accessions from the Vaccinium genus. Based on the physical position of the markers, three markers for each chromosome were chosen in the following way: One marker near the end of the short arm, one marker in the center, and one marker at the end of the long arm. The marker names, forward and reverse primer sequences, repeat motifs, and expected amplicon size for all the selected SSR markers are given in Supplementary Table S4.

PCR amplification was performed in 10 µl volume reactions containing 0.5 µM of Forward and Reverse primer, 1X GoTaq® Green Master Mix, which contains optimal concentrations of GoTaq® DNA Polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl2 and reaction buffer (Promega, USA), and 50 ng of genomic DNA. For some of the primers, a temperature gradient PCR using GoTaq® Hot Start Master Mixes (containing GoTaq® Hot Start Polymerase, magnesium, dNTPs, and buffer) was performed. The PCR was performed in DNA thermocycler (Eppendorf, Germany). The PCR program was: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, 34 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 45 s. This was followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 3 min. The PCR products were stored at 4 °C before loading. The PCR samples were loaded on 3% agarose gels run in TBE buffer. The SYBR™ Green I Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to stain the amplified DNA products, and images were taken using the Gel documentation system (iBlot, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The gel images were used to score the allele patterns of the SSRs for selected primers. The amplicon sizes were estimated based on a 100 bp GeneRuler as a DNA ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Polymorphism estimation and data analysis

The genotype profiles produced by the SSR markers were scored manually. Each allele was scored as present (1) or absent (0) of each of the SSR loci. Principal component analysis (PCA) and analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) were performed using GenAlEx 6.574. For AMOVA, the blueberry genotypes were divided into seven groups, of which five groups comprised wild clones (V. angustifolium, V. boreale, V. darrowii, V. tenellum, V. myrsinites). The southern highbush and northern highbush V. corymbosum cultivars were placed in the sixth and seventh groups, respectively, whereas cranberry accessions were categorized into the eighth group.

Clustering analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using Jaccard’s similarity coefficient through NTSYS-pc software Version 2.1175. The similarity matrix was used in cluster analysis using the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) and sequential, agglomerative, hierarchical, and nested (SAHN) clustering algorithm to obtain dendrogram. Nei’s76 genetic diversity (h2) and Shannon index (I*)77 were calculated with POPGENE Ver. 1.3278. Additional genetic diversity parameters such as polymorphic information content (PIC) and average number of alleles (NA) were calculated using the PowerMarker version 3.2579.

Data availability

The RNAseq datasets from our previous study were used to extract SSR information. The datasets, in the form of raw paired-end Illumina RNA sequencing reads, are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) at NCBI under the Bio project accession nos. PRJNA691351 and PRJNA691352. The SSR marker data is available in the article’s supplementary information files.

References

Chen, W. et al. Differential sensitivity of four highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) cultivars to heat stress. Pak. J. Bot. 44, 853–860 (2012).

Yang, B. & Kortesniemi, M. Clinical evidence on potential health benefits of berries. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2015.01.002 (2015).

Kalt, W. et al. Recent research on the health benefits of blueberries and their anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 11, 224–236 (2020).

Kalt, W., Howell, A. B., MacKinnon, S. L. & Goldman, I. L. Selected bioactivities of Vaccinium berries and other fruit crops in relation to their phenolic contents. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 87, 2279–2285. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.2985 (2007).

Bian, Y. et al. Patterns of simple sequence repeats in cultivated blueberries (Vaccinium section Cyanococcus spp.) and their use in revealing genetic diversity and population structure. Mol. Breeding. 34, 675–689 (2014).

Campa, A. & Ferreira, J. J. Genetic diversity assessed by genotyping by sequencing (GBS) and for phenological traits in blueberry cultivars. PLoS One. 13, e0206361 (2018).

Coville, F. V. Improving the wild blueberry (1937).

Zong, Y. et al. Phylogenetic relationship and genetic background of blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) based on retrotransposon-based SSAP molecular markers. Sci. Hort. 247, 116–122 (2019).

Kulkarni, K. P. et al. Admixture analysis using genotyping-by-sequencing reveals genetic relatedness and parental lineage distribution in highbush blueberry genotypes and cross derivatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 163 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Genetic and epigenetic signatures for improved breeding of cultivated blueberry. Hortic. Res. 11, uhae138 (2024).

Manzanero, B. R. et al. Genomic and evolutionary relationships among wild and cultivated blueberry species. BMC Plant Biol. 23, 126 (2023).

Hamblin, M. T., Warburton, M. L. & Buckler, E. S. Empirical comparison of simple sequence repeats and single nucleotide polymorphisms in assessment of maize diversity and relatedness. PloS One. 2, e1367 (2007).

Emanuelli, F. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure assessed by SSR and SNP markers in a large germplasm collection of grape. BMC Plant Biol. 13, 1–17 (2013).

Chen, W., Hou, L., Zhang, Z., Pang, X. & Li, Y. Genetic diversity, population structure, and linkage disequilibrium of a core collection of Ziziphus jujuba assessed with genome-wide SNPs developed by genotyping-by-sequencing and SSR markers. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 575 (2017).

Ramirez-Ramirez, A. R. et al. Comparing the performances of SSR and SNP markers for population analysis in Theobroma cacao L., as alternative approach to validate a new DdRADseq protocol for cacao genotyping. Plos One. 19, e0304753 (2024).

Singh, N. et al. Comparison of SSR and SNP markers in Estimation of genetic diversity and population structure of Indian rice varieties. PloS One. 8, e84136 (2013).

García, C., Guichoux, E. & Hampe, A. A comparative analysis between SNPs and SSRs to investigate genetic variation in a Juniper species (Juniperus Phoenicea ssp. turbinata). Tree. Genet. Genomes. 14, 87 (2018).

Saxena, P., Malik, L., Pattanaik, S. & Gudipalli, P. Genetic diversity analysis of a germplasm collection of red Sanders (Pterocarpus Santalinus Lf) using cross-species SSR, ISSR and RAPD markers. South. Afr. J. Bot. 174, 856–869 (2024).

Chapman, M. A. et al. Development, polymorphism, and cross-taxon utility of EST–SSR markers from safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L). Theor. Appl. Genet. 120, 85–91 (2009).

Pandey, M. K. et al. Highly informative genic and genomic SSR markers to facilitate molecular breeding in cultivated groundnut (Arachis hypogaea). Plant. Breed. 131, 139–147 (2012).

Park, Y. J., Lee, J. K. & Kim, N. S. Simple sequence repeat polymorphisms (SSRPs) for evaluation of molecular diversity and germplasm classification of minor crops. Molecules 14, 4546–4569 (2009).

Ellis, J. & Burke, J. EST-SSRs as a resource for population genetic analyses. Heredity 99, 125–132 (2007).

Liu, Y. et al. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of EST-SSR markers in blueberry (Vaccinium) and their cross-species transferability in Vaccinium spp. Sci. Hort. 176, 319–329 (2014).

Aiello, D. et al. Evaluation of cross-species transferability of SSR markers in Foeniculum vulgare. Plants 9, 175 (2020).

Nishiyama, S. et al. Genomic insight into the developmental history of Southern highbush blueberry populations. Heredity 126, 194–205 (2021).

Bell, D. J., Rowland, L. J., Polashock, J. J. & Drummond, F. A. Suitability of EST-PCR markers developed in highbush blueberry for genetic fingerprinting and relationship studies in lowbush blueberry and related species. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 133, 701–707 (2008).

Boches, P., Bassil, N. V. & Rowland, L. Genetic diversity in the highbush blueberry evaluated with microsatellite markers. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 131, 674–686 (2006).

Bassil, N. et al. Assessing genetic diversity of wild southeastern North American Vaccinium species using microsatellite markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 65, 939–950 (2018).

Burgher, K. L., Jamieson, A. R. & Lu, X. Genetic relationships among lowbush blueberry genotypes as determined by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 127, 98–103 (2002).

Debnath, S. C. Development of ISSR markers for genetic diversity studies in Vaccinium angustifolium. Nord. J. Bot. 27, 141–148 (2009).

Levi, A. & Rowland, L. Identifying blueberry cultivars and evaluating their genetic relationships using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and simple sequence repeat-(SSR-) anchored primers (1997).

Rowland, L. J., Dhanaraj, A. L., Polashock, J. J. & Arora, R. Utility of blueberry-derived EST-PCR primers in related Ericaceae species. HortScience 38, 1428–1432 (2003).

Rowland, L. J., Ogden, E. L. & Ehlenfeldt, M. K. EST-PCR markers developed for highbush blueberry are also useful for genetic fingerprinting and relationship studies in Rabbiteye blueberry. Sci. Hort. 125, 779–784 (2010).

Beers, L., Rowland, L. J. & Drummond, F. Genetic diversity of lowbush blueberry throughout the united States in managed and non-managed populations. Agriculture 9, 113 (2019).

Santana, Q. C. et al. Microsatellite discovery by deep sequencing of enriched genomic libraries. Biotechniques 46, 217–223 (2009).

Sorkheh, K. et al. In Silico search, characterization and validation of new EST-SSR markers in the genus Prunus. BMC Res. Notes. 9, 1–11 (2016).

Gao, G. et al. A long reads-based de-novo assembly of the genome of the Arlee homozygous line reveals chromosomal rearrangements in rainbow trout. G3 11, jkab052 (2021).

Varshney, R. K., Graner, A. & Sorrells, M. E. Genic microsatellite markers in plants: features and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 23, 48–55 (2005).

Bosamia, T. C., Mishra, G. P., Thankappan, R. & Dobaria, J. R. Novel and stress relevant EST derived SSR markers developed and validated in peanut. PloS One. 10, e0129127 (2015).

Zhou, Q. et al. Development and cross-species transferability of EST-SSR markers in Siberian Wildrye (Elymus sibiricus L.) using illumina sequencing. Sci. Rep. 6, 20549 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Development of EST-SSR markers and association mapping with floral traits in Syringa oblata. BMC Plant Biol. 20, 1–13 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Transcriptome analysis and annotation: SNPs identified from single copy annotated unigenes of three polyploid blueberry crops. PLoS One. 14, e0216299 (2019).

Rowland, L. J. et al. Generation and analysis of blueberry transcriptome sequences from leaves, developing fruit, and flower buds from cold acclimation through deacclimation. BMC Plant Biol. 12, 1–18 (2012a).

Li, L. et al. Comparative transcriptome sequencing and de Novo analysis of Vaccinium corymbosum during fruit and color development. BMC Plant Biol. 16, 1–9 (2016).

Callwood, J. et al. Differential morpho-physiological and transcriptomic responses to heat stress in two blueberry species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 2481 (2021).

Mengist, M. F. et al. Dissecting the genetic basis of bioactive metabolites and fruit quality traits in blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L). Front. Plant Sci. 13, 964656 (2022).

Zifkin, M. et al. Gene expression and metabolite profiling of developing highbush blueberry fruit indicates transcriptional regulation of flavonoid metabolism and activation of abscisic acid metabolism. Plant Physiol. 158, 200–224 (2012).

Qi, X. et al. Transcriptome analysis identifies genes related to the waxy coating on blueberry fruit in two northern-adapted Rabbiteye breeding populations. BMC Plant Biol. 19, 1–15 (2019).

An, H., Zhang, J., Xu, F., Jiang, S. & Zhang, X. Transcriptomic profiling and discovery of key genes involved in adventitious root formation from green cuttings of highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L). BMC Plant Biol. 20, 1–14 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Transcriptome sequencing of mung bean (Vigna radiate L.) genes and the identification of EST-SSR markers. PloS One. 10, e0120273 (2015).

Wang, D. et al. Comparative transcriptome analyses of drought-resistant and-susceptible Brassica napus L. and development of EST-SSR markers by RNA-Seq. J. Plant. Biology. 58, 259–269 (2015).

Chen, H. et al. Development of gene-based SSR markers in rice bean (Vigna umbellata L.) based on transcriptome data. PloS One. 11, e0151040 (2016).

Tulsani, N. J. et al. Transcriptome landscaping for gene mining and SSR marker development in coriander (Coriandrum sativum L). Genomics 112, 1545–1553 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Characterization of genome-wide microsatellites of Saccharina Japonica based on a preliminary assembly of illumina sequencing reads. J. Ocean. Univ. China. 15, 523–532 (2016).

Li, Y. C., Korol, A. B., Fahima, T. & Nevo, E. Microsatellites within genes: structure, function, and evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 991–1007 (2004).

Cho, Y. G. et al. Diversity of microsatellites derived from genomic libraries and GenBank sequences in rice (Oryza sativa L). Theor. Appl. Genet. 100, 713–722 (2000).

Zhao, M., Shu, G., Hu, Y., Cao, G. & Wang, Y. Pattern and variation in simple sequence repeat (SSR) at different genomic regions and its implications to maize evolution and breeding. BMC Genom. 24, 136 (2023).

Deng, P. et al. Genome-wide characterization of microsatellites in triticeae species: abundance, distribution and evolution. Sci. Rep. 6, 32224 (2016).

Jiao, Y. et al. Development of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers from a genome survey of Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra). BMC Genom. 13, 1–16 (2012).

Nashima, K. et al. SSR markers developed using next-generation sequencing technology in pineapple, Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. Breed. Sci. 70, 415–421 (2020).

Liu, S. R., Li, W. Y., Long, D., Hu, C. G. & Zhang, J. Z. Development and characterization of genomic and expressed SSRs in citrus by genome-wide analysis. PloS One. 8, e75149 (2013).

Senthilvel, S. et al. Development and mapping of simple sequence repeat markers for Pearl millet from data mining of expressed sequence tags. BMC Plant Biol. 8, 1–9 (2008).

Tailor, S., Bykova, N. V., Igamberdiev, A. U. & Debnath, S. C. Structural pattern and genetic diversity in blueberry (Vaccinium) clones and cultivars using EST-PCR and microsatellite markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 64, 2071–2082 (2017).

Rowland, L. J. et al. Generating genomic tools for blueberry improvement. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 12, 276–287 (2012b).

Bassil, N., Bunch, T., Nyberg, A., Hummer, K. & Zee, F. in International Symposium on Molecular Markers in Horticulture 859. 81–88.

Camp, W. The North American blueberries with notes on other groups of Vacciniaceae (1945).

Vander Kloet, S. The taxonomic status of Vaccinium boreale. Can. J. Bot. 55, 281–288 (1977).

Vander Kloet, S. The taxonomic status of Vaccinium pallidum, the hillside blueberries including Vaccinium vacillans. Can. J. Bot. 56, 1559–1574 (1978).

Li, L. et al. Development of SSR markers from ESTs of gramineous species and their chromosome location on wheat. Prog. Nat. Sci. 18, 1485–1490 (2008).

Gupta, P. K. et al. Transferable EST-SSR markers for the study of polymorphism and genetic diversity in bread wheat. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 270, 315–323 (2003).

Beier, S., Thiel, T., Münch, T., Scholz, U. & Mascher, M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 33, 2583–2585 (2017).

Untergasser, A. et al. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e115–e115 (2012).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and samtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Peakall, R. & Smouse, P. E. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research–an update. Bioinformatics 28, 2537–2539. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460 (2012).

Rohlf, F. J. & NTSYSpc Numerical Taxonomy System, ver. 2.1. Applied Biostatistics (2018).

Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70, 3321–3323 (1973).

Lewontin, R. The Apportionment of Human Diversity, Chapter Evolutionary Biology (1972).

Yeh, F. C. et al. POPGENE, version 1.32: the user friendly software for population genetic analysis. Molecular Biology and Biotechnology Centre, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada (1999).

Liu, K. & Muse, S. V. PowerMarker: an integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics 21, 2128–2129 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA-NIFA) through the award numbers 2018-38821-27744 and 2022-38821-37298.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.P.K, performed and conceived the experiments, analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript; RKA, helped in genotyping; JJC, NV, provided the plant material for the research; UKR, provided SSR repeat information; SE reviewed the manuscript; HB, and MI, provided genomic coordinates for the markers; KM, supervised the project. All authors reviewed and approved this submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kulkarni, K.P., Appiah, R.K., Johnson-Cicalese, J. et al. Generation and characterization of novel transcriptome-derived SSR markers for genetic applications in blueberry. Sci Rep 15, 25050 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10317-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10317-2