Abstract

Synthetic pesticides pose a risk to the environment and human health by contaminating soil, water, and food chains. Natural plant-based alternatives offer a safer and more sustainable solution by reducing pollution, supporting biodiversity, and minimising pesticide resistance. This study evaluated the antifeedant activity of methanolic leaves extracts from invasive black cherry (Prunus serotina Erhr.) against a storage pest, the granary weevil (Sitophilus granarius L.). Chromatographic analysis of P. serotina leaves methanolic extracts identified 10 main phenolic compounds, with ursolic acid, p-coumaric acid o-coumaric acid, and caffeic acid exceeding 10%. LC-MS/MS analysis detected 12 compounds above the limit of quantification (LOQ), with luteolin-7-O-glucoside, caffeic acid, and chlorogenic acid at the highest concentrations. The antifeedant activity of P. serotina leaves methanolic extract was tested using the wheat wafer method, showing medium antifeedant effects at all extract concentrations (3.5, 5.0, and 12.0 mg/mL). Both males and females fed significantly less extract-treated wafers, with the inhibition of female feeding being stronger at 12.0 mg/ml. The extracts of P. serotina effectively discourage feeding of S. granarius, and the potency increases with concentration. Their flavonoids, phenolic acids, and cyanogenic glycosides suggest a complex mode of action, making them a promising natural alternative to synthetic insecticides. Further research should isolate key active compounds and evaluate their efficacy as botanical pesticides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Synthetic pesticides pose significant environmental and health risks in Europe, despite the introduction of new regulations. These chemicals contaminate soil, water, and food chains, affecting biodiversity and human health1,2. Numerous studies show that pesticides have led to declines in insect biomass, farmland birds, and pollinator populations1. On the other hand, insect pests are significant threat to stored food products, causing substantial losses and compromising food quality and safety3,4. These pests can reduce nutritional value, contaminate food with body fragments, and create unhygienic conditions3. Various control methods are used, including physical, chemical, and biological approaches5. Traditional pest management strategies involve synthetic pesticides, but concerns about pest resistance and environmental hazards have led to the exploration of alternatives such as biopesticides and other non-chemical methods6.

Granary weevil (Sitophilus granarius L.) has been a significant storage pest in Europe since the Neolithic period, with evidence of its early introduction found in Greece and central Europe7. This flightless weevil, along with other pests such as the Indian meal moth, continues to be a major problem in modern grain storage facilities, while mites, psocids, and other beetles are common secondary pests8.

Control of the grain weevil in stored cereals can be achieved through chemical and non-chemical methods. Chemical approaches include essential oils, spinetoram, and malathion (no longer approved for use in Europe), with malathion being the most effective9. The fatty acid composition of wheat kernels influences the development of S. granarius, and certain fatty acids can potentially stimulate or inhibit pest reproduction10. Varietal resistance is another non-chemical approach, as different wheat and corn genotypes exhibit varying levels of susceptibility to weevil attack11. Non-chemical methods for pest control in agriculture and storage have gained attention due to concerns about insecticide resistance, worker safety, and consumer demands for residue-free products12. More specifically, the management of S. granarius in stored grain involves not only conventional chemical compounds but also naturally derived phytochemicals. Susceptibility to infestation is further affected by phenolic and lipophilic compounds present in the grain, with higher levels of total lipids and sterols associated with increased vulnerability13. In search of alternatives to synthetic pesticides, plant extracts from Achillea phrygia, Prangos ferulacea, and Salvia wiedemannii have demonstrated both insecticidal and repellent properties against S. granaries14. In this context, bioactive phytochemicals are being actively investigated as eco-friendly and cost-effective solutions for pest management in stored grain systems15. Additionally, volatile compounds naturally emitted by S. granarius, such as 3-hydroxy-2-butanone and 1-pentadecene, have been found to trigger both electrophysiological and behavioral responses in the insects. These volatiles hold promise for the development of novel monitoring and control strategies, with 3-hydroxy-2-butanone functioning as an attractant at low concentrations and as a repellent at higher concentrations16. In Poland, the following substances are approved for the chemical control of the grain weevil: deltamethrin, pirimiphos-methyl, aluminum phosphide, and pyrethrins (https://www.gov.pl/web/rolnictwo/wyszukiwarka-srodkow-ochrony-roslin---zastosowanie).

Plant-derived insecticides can be a solution to replace chemical agents in pest control. Some invasive plant species (e.g. species of the Solidago or Reynoutria genus) are suspected to be a source of natural pesticides17,18,19,20. Black cherry (Prunus serotina Erhr.) is native to North America and was successfully introduced to Europe in the 17th century21. Issues related to its spread are studied in several countries, including Italy, Hungary, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, France, and Norway22,23,24,25,26,27,28. This alien species thrives in various habitats, demonstrating a strong capacity for both generative reproduction and vegetative sprouting. Its numerous seeds are widely dispersed by birds and mammals, and it establishes a long-lasting, shade-tolerant seedling bank21,29,30. It is suspected that the black cherry effectively competes with co-occurring species by producing and releasing allelochemicals31,32,33. P. serotina possesses strong constitutive chemical defences against herbivores, with key compounds including cyanogenic glycosides34 and phenolic compounds, primarily flavonoids35. Furthermore, amygdalin and prunasin (cyanogenic glycosides present in the leaves of P. serotina) have been shown to impede the feeding activities of the cherry-oat aphid, Rhopalosiphum padi36. The mechanism of the toxicity is the inhibition of cellular respiration by the release of toxic hydrogen cyanide (HCN) from cyanogenic glycosides37. Cyanogenesis is widely recognised as an effective herbivore defence mechanism38,39. Research has shown that within the context of cyanogenic plants, there is a trade-off between defence mechanisms against herbivores and pathogens38. In black cherry populations established in Europe, there has been a change in the concentration of cyanogenic glycosides compared to their native range, resulting in alterations in their resistance to leaf-eating insects40. A significant compound in P. serotina leaves are tannins, that can be categorised into two types: hydrolyzable tannins and non-hydrolyzable (or condensed) tannins. The function of hydrolyzable tannins is primarily to serve as a defence mechanism against herbivores41,42while condensed tannins primarily protect plants from pathogens43as demonstrated in P. serotina44. Consequently, black cherry extracts exhibit high biological activity. However, the insecticidal properties of black cherry leaf extracts have not previously been studied.

The purpose of the study was to determine the chemical composition of the methanolic extract of black cherry leaves and to evaluate its antifeeding activity against grain weevil.

The following research hypotheses have been formulated:

-

Granary weevil feeding will be significantly reduced by methanolic extracts of black cherry leaves.

-

The extent of feeding inhibition will depend on the concentration of the extract used.

-

The effect of P. serotina leaf extracts on granary weevil feeding behaviour will not depend on sex.

Materials and methods

Collection of plant material

Material for the preparation of extracts: fresh black cherry leaves were collected from a fallow field in the city of Wrocław, Poland (51.168479 N, 17.009228 E). The leaves of P. serotina were collected at the beginning of leafing, in April 2024. The collected material was dried in the dark at a maximum temperature of 50 °C. After a constant dry mass, the leaves were powdered, and methanolic extracts were prepared from them.

Extracts of black cherry leaves and preparation of samples for chromatographic analyses

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). All extractions and analyses were performed in triplicate. The black cherry leaves extract method of45 with slight modifications was used. Briefly, 20 ± 0.05 g of dried and powdered black cherry leaves were weighed in a 250 mL volume glass flask and macerated for 24 h (120 rpm) with 200 mL of analytical grade 80% methanol. After the extraction process, the samples were centrifuged (30 min, 5000 rpm), filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The dried extract was weighted with an analytical scale. At this step, the extract was divided for insecticidal tests and further chemical analyses.

The extraction yield (per 100 g of dried material) was calculated according to equation:

For the GC-MS profiling, 10 mg of extract was weighted and suspended with 500 µL of pyridine and 50 µL of BSTFA for derivatization of the analytes was added. The silylation process was carried out for 45 min at 60 °C. Before the analysis, the sample was diluted 10 times with methyl tert-butyl ether. For LC-MS/MS analysis 10 mg of extract was suspended with 10 mL of pure, chromatographical grade methanol. For LC-MS/MS samples, they were diluted 1000 times (for hyperoside and chlorogenic acid analysis) and 100 times (the rest of the analytes).

Total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TPC) of black cherry leaves methanolic extract

TPC and TFC were determined by the colorimetric method based on the46 method. Briefly, for the determination of TPC, 125 mL of black cherry methanolic solution (1 mg/mL) was mixed with 500 mL of distilled water and 125 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and kept for 6 min. Then, 1.25 mL of 7% sodium carbonate was added, and volume was set up for 3 mL in total with distilled water. After incubation for 90 min at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 760 nm. Results were expressed as gallic acid equivalents (g GAE/100 g dw).

For TFC measurement 250 mL of black cherry methanolic solution (1 mg/mL) was mixed with 75 mL of sodium nitrate (5% solution) and kept for 6 min. Then 150 mL of aluminium(III) chloride solution (10% solution) and 500 mL of sodium hydroxide (1 M) were added. The final volume was set up for 2.5 mL with distilled water, the sample was vigorously shaken and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm and the results were expressed as quercetin equivalents (g QCE/100 g dw).

GC-MS profiling of black cherry leaves methanolic extract

The GC-MS profiling of black cherry leaves extracts was carried out with Shimadzu GCMS QP 2020 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with SH-Rxi-5Sil MS (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) column with dimensions 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm phase thickness. 1 µL of the sample was injected at 280 °C with a split of 20. Helium with a linear velocity of 37.5 cm/s and a column flow of 1 mL/min was used as the carrier gas. Used for analytes, the separation program started at 100 °C held for 1 min and then raised to 190 °C at a rate of 2 °C/min, then to 300 at a rate of 5 °C/min and held for 25 min. The interface temperature was 270 °C and ion source temperature was 250 °C. Electron impact (EI) mode was used for analytic ionization at 70 eV. For analysis SCAN mode in the range 40–1000 m/z was used.

The compound’s identification was based on the comparison of experimentally obtained mass spectra with those available in NIST 20 (National Institute of Standards and Technology) library and literature47,48supported with pure analytical standards reference.

LC-MS/MS analysis of black cherry leaves methanolic extract

The LC-MS/MS analysis was performed with LCMS-8045 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with AccucoreTM RP-MS column (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with dimensions 2.6u, 100 A, 150 × 3.0 mm. As eluents 0.1% aqueous solution of formic acid (A) and 0.1% ACN solution of formic acid (B) were used. The analysis was performed with gradient program: start with 10% B, then 20% B in 5 min, then 60% B in 10 min, then 10% B in 13 min kept up to 17 min. The column flow was 0.35 mL/min and column oven temperature 45 °C.

The analysis of compounds was performed in MRM mode, which details are given in Table S1 (Supplementary) while the quantification was based on an external standard method, namely 5-points calibration curves. The selection of quantification analytes was based on the earlier research focus on growth in Poland P. serotina49namely, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, hyperoside, kempferol-3-rutinoside, luteolin-7-glucoside, o-coumaric acid, p-coumaric acid, quercetin-3-glucoside, quercetin, rutin and ursolic acid.

Test of antifeedant activity of black cherry leaves methanolic extract

The feeding deterrent activity were carried out using granary weevil (S. granarius) species of stored product pest. S. granarius had been one of the stored pests selected originally by Nawrot et al.50 for its stored product pest status, and is still considered as model organisms for screening the antifeedant activity of chemical compounds51,52,53,54,55. The insects were reared in permanent darkness in climatic chambers at 24 ± 1 °C and relative humidity at 70 ± 5%. Granary weevil was offered wheat grain of cv. Natula as a substrate for food and oviposition. The tests were carried out in the same rearing chambers. The test insects were separated from the culture and food 24 h before the start of the tests. Adult grain weevils (at least 14 days old) were differentiated into males and females using differences in morphological characteristics (sexual dimorphism)56.

The ‘wheat wafer test’ is commonly used to evaluate the feeding deterrent activity against various insect pests57,58,59,60. It was run as described by Nawrot et al.50,51and identically as used more recently by Jackowski et al.55,61. Three concentrations of black cherry leaves methanolic extract were prepared and used for biotests: 3.5 mg/mL, 5.0 mg/mL and 12.0 mg/mL. To prepare individual concentrations, 99.9% ethanol (as a solvent) and a drop of tween 80 (as an emulsifier) were used. The methodology of the ‘wheat wafer test” is described in detail in Supplementary material.

Statistical analysis

The total deterrency coefficient (T) and the loss of mass of wheat wafers (calculated in multiple choice tests - Supplementary) were used as an indicator of the biological activity of the extracts tested. Data sets for individual concentration of extract and sex of tested insects were checked for normality based on the Shapiro–Wilk W test. It turned out that the data did not have a normal distribution, so the nonparametric methods were used. Kruskal–Wallis analysis of the variance (ANOVA) of ranks was used to compare the T values obtained in wafer tests and feeding inhibition for a particular concentration of black cherry leaves methanolic extracts and insects sex. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for pairwise comparisons - wheat wafer mass loss for wheat wafer immersed in an extract of a given concentration versus wheat wafer immersed only in solvent (99.9% ethanol with one drop of tween 80). Significance was evaluated at p ≤ 0.05. The analyses were performed using STATISTICA software v. 13 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA).

Results

Chemical profile of black cherry leaves methanolic extract

The total yield of the methanolic extract of black cherry leaves used in this study was 17.16 ± 0.03 g per 100 g of dried leaves. The TPC in the crude extract was determined to be 2.440 g GAE per 100 g dry weight (dw), while the TFC reached 0.932 g QCE per 100 g dw.

As a first attempt, the main phenolic constituents of black cherry leaves were identified by the GC-MS technique, followed by derivatization of the analytes. This attempt allowed us to find 10 compounds (Table 1), while 9 were successfully identified. Among the compounds found, the derivative ursolic acid (31.34 ± 0.34%), p-coumaric acid derivative (21.18 ± 0.32%), o-coumaric acid derivative (11.34 ± 0.12%) and caffeic acid derivative (13.72 ± 0.09%) were found in amount greater than 10%.

Among analysed by LC-MS/MS method 12 compounds were found with an amount higher than determined LOQ, while one was only with an amount higher than LOD (Table 2). The highest concentration was found for luteolin-7-O-glucoside, caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid, 273.43 ± 3.79, 215.86 ± 6.11 and 214.78 ± 6.62 µg/100 mg of extract, respectively, while the lowest amounts were found for ursolic acid, ferulic acid and o-coumaric acid, 17.14 ± 0.17, 29.69 ± 0.15 and 49.41 ± 1.50, respectively (Table 2).

Antifeedant activity of tested extract

The antifeedant activity of the methanolic extracts of the black cherry leaves was determined based on the calculation of three coefficients: relative (R), absolute (A), and total (T) deterrency (Table 3). The activity of three concentrations of the extract (3.5, 5.0 and 12.0 mg/mL) was tested against female and male granary weevil. Each concentration of the extract showed medium deterrent activity (T values between 51 and 100) (Table 3). Statistical analyses did not show significant differences in T coefficients between females and males (Table 3) and individual extract concentrations (Table S2 (Supplementary)).

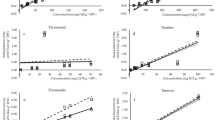

Further statistical analysis was performed based on the wheat wafers mass loss from choice test. For each concentration of the methanolic extract from the leaves of black cherry, the mass loss of the reference wheat wafer was compared with the mass loss of the extract-treated wafers. Regardless of the concentration of the extract used, the female grain weevils fed significantly more on the control wheat wafers than on the wheat wafers treated with black cherry leaf extract (Table S3 (Supplementary), Fig. 1). Furthermore, significant inhibition of feeding (loss of weight of the wheat wafer) was also observed in males (Table S3 (Supplementary), Fig. 1). In more detail, the loss of mass of the wheat wafer was significantly lower compared to the control using all doses of extract (3.5, 5.0 and 12.0 mg/mL) (Table S3 (Supplementary), Fig. 1).

Loss of wheat wafer mass as a result of feeding by Sitophilus granarius females and males under the influence of black cherry leaves methanolic extract of various concentrations (Mean ± SE). Significant differences between pairs (control vs. tested concentration of the Prunus serotina extract) were estimated using the Mann–Whitney U test, marked with *n = 5.

Furthermore, feeding inhibition of S. granarius female was found to be significantly higher when using the P. serotina leaf extract at a concentration of 12.0 mg/mL compared to inhibition under the influence of the extract at a concentration of 3.5 mg/mL (H = 6.86; p = 0.0324) (Fig. 2). Inhibition of feeding of male grain weevils did not differ significantly between the concentrations of the extract of black cherry leaves used (H = 2.06; p = 0.3564) (Fig. 2). Thus, the effects were sex-dependent.

Discussion

Prunus serotina, commonly known as black cherry, exhibits significant biological activity due to its diverse phytochemical composition. Research has identified bioactive compounds such as polyphenols, anthocyanins, and flavonoids, which contribute to their strong antioxidant, antimicrobial, and pharmacological properties49,62. Our research has shown that TPC (total phenolic content) and TFC (total flavonoid content) in the crude extract were 2.440 g GAE (gallic acid equivalent)/100 g dw and 0.932 g QCE (quercetin equivalent)/100 g dw, respectively. In terms of chemical composition, the findings of the present study are consistent with previous studies on black cherry samples collected in Poland. For example49, reported a comparable TPC content of 2.154 g GAE per 100 g dw. However63, identified significantly higher levels of TPC, 3.27–5.11% dw. These variations can be attributed to different environmental factors during black cherry growth, including soil quality, temperature, humidity, and other conditions.

GC-MS analysis identified 9 of 10 phenolic compounds, with ursolic acid, p-coumaric acid, o-coumaric acid, and caffeic acid (13.72%) being the most abundant. LC-MS/MS detected 12 compounds above the LOQ, with luteolin-7-O-glucoside, caffeic acid, and chlorogenic acid at the highest concentrations, while ursolic acid, ferulic acid, and o-coumaric acid had the lowest. As may be observed, there were significant differences between quantitative and qualitative analyses between the results of the GC-MS and LC-MS/MS techniques. The GC-MS technique did not allow identifying flavonoid compounds, which was expected; however, the oleanoic acid and ursolic acid was surprising, which was not observed by LC-MS/MS analysis. The reason for this may be found with the sample preparation procedure (derivatization for GC-MS) and the basic principles of the techniques which were shown also in earlier studies45,64. Regarding the nonvolatile compounds profile, presented in this study results show some differences in comparison to other studies such as35,49or Olszewska and Kwapisz (2011), however, the reasons of that may be found with different techniques of extraction, different plant material, or different plant parts.

Despite extensive studies on its medicinal and antioxidant potential, the insecticidal properties of P. serotina remain largely unexplored. The ethanolic extracts of P. serotina fruit have shown antimicrobial activity against gram-negative bacteria and Staphylococcus aureus65while its bark extract has shown cysticidal effects against Taenia crassiceps (tapeworm), with naringenin identified as a key active compound66. The leaves contain vasorelaxant constituents, such as hyperoside, prunin, and ursolic acid, that induce vascular smooth muscle relaxation67. Comparative studies indicate that P. padus leaves exhibit higher antioxidant and antimicrobial activities than P. serotina49.

The insecticidal potential of other Prunus species has been partially explored. For example, methanolic extracts of Prunus armeniaca (apricot) kernels exhibit significant toxicity against Tribolium confusum68while P. persica extracts show limited insecticidal activity69. This study demonstrates that P. serotina methanolic extracts effectively reduce the feeding activity of male and female S. granarius. The antifeedant effect increases with the concentration of the extract, ranging from 3.5 to 12.0 mg/ml. For comparison, the concentration of deltamethrin used to protect the grain against S. granarius is 25 mg/mL in solution (Plan protection procucts in Poland). The repellent activity was also more distinct for the females compared to the males of S. granarius. According to other studies, various plant extracts, including those from Achillea wilhelmsii, Capsicum annuum, and Melaleuca alternifolia, have also shown promising insecticidal effects against S. granarius70. Lichen extracts of Lecanora muralis, Letharia vulpina, and Peltigera rufescens also demonstrated high mortality rates against adult S. granarius, with increased effectiveness at higher concentrations and longer exposure times71. Furthermore, Achillea phrygia, Prangos ferulacea, and Salvia wiedemannii exhibited both insecticidal and repellent properties against S. granarius14. It was also found that the feeding and oviposition behaviour of S. granarius is influenced by various wheat extracts and environmental factors, and the olfactory sensilla plays a crucial role in detecting these stimuli (Levinson and Kanaujia, 1982).

LC-MS/MS analysis identified several bioactive compounds extracted from the leaves of P. serotina, including luteolin-7-O-glucoside, caffeic acid, and chlorogenic acid. Chlorogenic acid showed high toxicity against agricultural pests such as Bemisia tabaci and Spodoptera frugiperda20,72. Flavonoids such as quercetin and kaempferol, detected in small amounts, are known for their insecticidal and deterrent properties73,74. Cyanogenic glycosides, present in P. serotina, serve as chemical defences, releasing toxic hydrogen cyanide upon tissue damage75. Other studies indicate that both natural and synthetic cyanohydrins effectively act as fumigants against stored-product insects76. It is important to note, that the interactions between compounds in mixtures can lead to complex effects that differ from those of individual substances, not explored in this research77. Furthermore, the presence of minor constituents such as flavonoids and cyanogenic glycosides can modulate the action of primary compounds, contributing to the broader ecological role of plants as natural pest control agents78.

Conclusions

The methanolic extracts of P. serotina effectively discourage the feeding of S. granarius, the potency increasing alongside the concentration of the extract. The presence of flavonoids, phenolic acids, and cyanogenic glycosides suggests a multifaceted mode of action, potentially making P. serotina extracts a viable and environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic insecticides. Future studies should focus on isolating specific compounds responsible for the insecticidal effect and comparing their efficacy against other plant-based pesticides.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ali, S., Ullah, M. I., Sajjad, A., Shakeel, Q. & Hussain, A. Environmental and health effects of pesticide residues. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 48 Vol. 48 (eds Inamuddin, Ahamed, M. I. & Lichtfouse, E.) 311–336 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Schleiffer, M. & Speiser, B. Presence of pesticides in the environment, transition into organic food, and implications for quality assurance along the European organic food chain – A review. Environ. Pollut. 313, 120116 (2022).

Singh, P., Santosh, S. & Satya, N. N. Grain storage insect-pest infestation- issues related to food quality and safety. Agricultural Food Sciences (2013).

Sarwar, M. H. Development and boosting of integrated insect pests management in stored grains. Res. Reviews: J. Agric. Allied Sci. 2, 16–20 (2017).

Bell, C. H. Pest control of stored food products: insects and mites. in Hygiene in Food Processing 494–538Elsevier, (2014). https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857098634.3.494

Eze, S. & Echezona, B. Agricultural pest control programmes, food security and safety. AJFAND 12, 6582–6592 (2012).

Panagiotakopulu, E. & Buckland, P. C. Early invaders: farmers, the granary weevil and other uninvited guests in the neolithic. Biol. Invasions. 20, 219–233 (2018).

Niedermayer, S. & Steidle, J. L. Lagerbedingungen und Vorratsschädlinge in Getreidelagern Im ökologischen Landbau in Baden-Württemberg. Mitteilungen Der Deutschen Gesellschaft Allgemeine Und Angewandte Entomologie 15, (2006).

Askar, S. I., Al-Assal, M. S. & Nassar, A. M. K. Efficiency of some essential oils and insecticides in the control of some Sitophilus insects (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Egypt. J. Plant. Prot. Res. 4, 39–55 (2016).

Nietupski, M., Ludwiczak, E., Cabaj, R., Purwin, C. & Kordan, B. Fatty acids present in wheat kernels influence the development of the grain weevil (Sitophilus granarius L). Insects 12, 806 (2021).

Dinuţă, A., Bunescu, H., Dan, G. T. & Bodis, I. Researches Concerning the Behaviour of Some Different Wheat and Corn Genotypes to Granary Weevil (Sitophilus granarius L.) Attack. UASVMCN-AGR 67, (2010).

Jabran, K. & Chauhan, B. S. Non-Chemical Weed Control doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/C2016-0-00092-X. (2018).

Kordan, B. et al. Phenolic and lipophilic compounds of wheat grain as factors affecting susceptibility to infestation by granary weevil (Sitophilus granarius L). J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 64–72. https://doi.org/10.5073/JABFQ.2019.092.009 (2019).

Kanik, F. & Karakoç, Ö. C. Bazı Bitki Ektraktlarının Sitophilus granarius (Linnaeus, 1758) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) ve Tribolium castaneum (Herbst, 1797) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) Üzerindeki insektisidal ve Davranışsal etkileri. Bitki Koruma Bülteni. 60, 31–40 (2020).

Saha, A., Roy Choudhury, S. & Bhadra, K. A review on insecticidal efficacy of phytochemicals on stored grain insect pests. Not Sci. Biol. 16, 11939 (2024).

Cai, L., Macfadyen, S., Hua, B., Xu, W. & Ren, Y. The correlation between volatile compounds emitted from Sitophilus granarius (L.) and its electrophysiological and behavioral responses. Insects 13, 478 (2022).

Pavela, R., Vrchotová, N. & Šerá2, B. Growth inhibitory effect of extracts from Reynoutria sp. plants against Spodoptera littoralis larvae. Agrociencia 42, 573–584 (2008).

Benelli, G. et al. Evaluation of two invasive plant invaders in Europe (Solidago Canadensis and Solidago gigantea) as possible sources of botanical insecticides. J. Pest Sci. 92, 805–821 (2019).

Margaritopoulou, T. et al. Reynoutria sachalinensis extract elicits SA-dependent defense responses in courgette genotypes against powdery mildew caused by podosphaera xanthii. Sci. Rep. 10, 3354 (2020).

Herrera-Mayorga, V. et al. Insecticidal activity of organic extracts of Solidago graminifolia and its main metabolites (Quercetin and chlorogenic Acid) against Spodoptera frugiperda: an in vitro and in Silico approach. Molecules 27, 3325 (2022).

Starfinger, U. Introduction and naturalization of Prunus serotina in central Europe. In Plant Invasions: Studies from North America and Europe 161–171 (Backhuys, 1997).

Deckers, B., Verheyen, K., Hermy, M. & Muys, B. Effects of landscape structure on the invasive spread of black Cherry Prunus serotina in an agricultural landscape in Flanders. Belgium Ecography. 28, 99–109 (2005).

Godefroid, S., Phartyal, S. S., Weyembergh, G. & Koedam, N. Ecological factors controlling the abundance of non-native invasive black Cherry (Prunus serotina) in deciduous forest understory in Belgium. For. Ecol. Manag. 210, 91–105 (2005).

Csiszár, Á. et al. Allelopathic potential of some invasive plant species occurring in Hungary. Allelopathy J. 31, 309–318 (2013).

Poyet, M. et al. Invasive host for invasive pest: when the A siatic Cherry fly (Drosophila suzukii) Meets the A Merican black Cherry (Prunus serotina) in Europe. Agri For. Entomol. 16, 251–259 (2014).

Gentili, R. et al. Comparing Negative Impacts of Prunus serotina, Quercus rubra and Robinia pseudoacacia on Native Forest Ecosystems. Forests 10, 842 (2019).

Nestby, R. D. J. The status of Prunus padus L. (Bird Cherry) in forest communities throughout Europe and Asia. Forests 11, 497 (2020).

Desie, E. et al. Litter share and clay content determine soil restoration effects of rich litter tree species in forests on acidified sandy soils. For. Ecol. Manag. 474, 118377 (2020).

Pairon, M., Chabrerie, O., Casado, C. M. & Jacquemart, A. L. Sexual regeneration traits linked to black Cherry (Prunus Serotina Ehrh.) invasiveness. Acta Oecol. 30, 238–247 (2006).

Closset-Kopp, D., Chabrerie, O., Valentin, B., Delachapelle, H. & Decocq, G. When Oskar Meets alice: does a lack of trade-off in r/K-strategies make Prunus serotina a successful invader of European forests? For. Ecol. Manag. 247, 120–130 (2007).

Bączek, P. & Halarewicz, A. Effect of black Cherry (Prunus serotina) litter extracts on germination and growth of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) seedlings. Pol. J. Ecol. 67, 137 (2019).

Halarewicz, A., Szumny, A. & Bączek, P. Effect of Prunus serotina ehrh. Volatile compounds on germination and seedling growth of Pinus sylvestris L. Forests 12, 846 (2021).

Bączek, P. & Halarewicz, A. Allelopathic effect of black Cherry (Prunus Serotina Ehrh.) on early growth of white mustard (Sinapis Alba L.) and common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench): Is the Invader a Threat to Restoration of Fallow Lands? Agronomy 12, 2103 (2022).

Santamour, F. S. Amygdalin in Prunus leaves. Phytochemistry 47, 1537–1538 (1998).

Olszewska, M. Flavonoids from Prunus serotina Ehrh. Acta Pol. Pharmaceutica-Drug Res. 62, 127–133 (2005).

Halarewicz, A. & Gabryś, B. Probing behavior of bird Cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiphum Padi (L.) on native bird Cherry Prunus padus L. and alien Invasive black Cherry Prunus serotina erhr. In Europe and the role of cyanogenic glycosides. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 6, 497–505 (2012).

Sánchez-Pérez, R. et al. Prunasin hydrolases during fruit development in sweet and bitter almonds. Plant Physiol. 158, 1916–1932 (2012).

Ballhorn, D. J., Pietrowski, A. & Lieberei, R. Direct trade-off between cyanogenesis and resistance to a fungal pathogen in lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L). J. Ecol. 98, 226–236 (2010).

Gleadow, R. M. & Møller, B. L. Cyanogenic glycosides: synthesis, physiology, and phenotypic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 65, 155–185 (2014).

Schilthuizen, M. et al. Incorporation of an invasive plant into a native insect herbivore food web. PeerJ 4, e1954 (2016).

Lewis, N. G. & Yamamoto, E. Tannins — Their place in plant metabolism. In Chemistry and Significance of Condensed Tannins (eds Hemingway, R. W. et al.) 23–46 (Springer US, 1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-7511-1_2.

Schultz, J. C. Tannin-Insect interactions. In Chemistry and Significance of Condensed Tannins (eds Hemingway, R. W. et al.) 417–433 (Springer US, 1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-7511-1_26.

Hammerschmidt, R. Phenols and plant–pathogen interactions: the saga continues. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 66, 77–78 (2005).

Halarewicz, A., Pląskowska, E., Sokół-Łętowska, A. & Kucharska, A. The effect of Monilinia seaveri (Rehm) honey infection on the condensed tannins content in the leaves of Prunus serotina Ehrh. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Hortorum Cultus. 12, 95–106 (2013).

Pachura, N. et al. Chemical investigation on Salvia officinalis L. Affected by multiple drying techniques – The comprehensive analytical approach (HS-SPME, GC–MS, LC-MS/MS, GC-O and NMR). Food Chem. 397, 133802 (2022).

Hamrouni-Sellami, I. et al. Total phenolics, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity of Sage (Salvia officinalis L.) plants as affected by different drying methods. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 6, 806–817 (2013).

Jaroszyńska, J. & Ligor, T. The identification of phenolic compounds by a gas chromatographic method on three capillary columns with the same non-polar stationary phase. Anal. Chim. Acta. 539, 11–15 (2005).

Wang, G. et al. Optimization and validation of a method for analysis of Non-Volatile organic acids in Baijiu by derivatization and its application in three Flavor-Types of Baijiu. Food Anal. Methods. 15, 1606–1618 (2022).

Telichowska, A. et al. Polyphenol content and antioxidant activities of Prunus padus L. and Prunus serotina L. leaves: electrochemical and spectrophotometric approach and their antimicrobial properties. Open. Chem. 18, 1125–1135 (2020).

Nawrot, J., Harmatha, J. & Novotny, L. Insect feeding deterrent activity of bisabolangelone and of some sesquiterpenes of eremophilane type. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 12, 99–101 (1984).

Nawrot, J., Bloszyk, E., Harmatha, J., Novotny, L. & Drozdz, B. Action of antifeedants of plant origin on beetles infesting stored products. Acta Entomologica Bohemslovaca. 83, 327–335 (1986).

Nawrot, J., Harmatha, J., Kostova, I. & Ognyanov, I. Antifeeding activity of rotenone and some derivatives towards selected insect storage pests. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 17, 55–57 (1989).

Harmatha, J. & Nawrot, J. Insect feeding deterrent activity of lignans and related phenylpropanoids with a Methylenedioxyphenyl (piperonyl) structure moiety. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 104, 51–60 (2002).

Nawrot, J., Dams, I. & Wawrzeńczyk, C. Feeding deterrent activity of terpenoid lactones with a p-menthane system against stored-product pests. J. Stored Prod. Res. 45, 221–225 (2009).

Jackowski, J. et al. Antifeedant activity of Xanthohumol and supercritical carbon dioxide extract of spent hops against stored product pests. Bull. Entomol. Res. 105, 456–461 (2015).

Dinuţă, A., Bunescu, H. & Bodiş, I. Contributions to the knowledge of morphology of the granary weevil (Sitophilus granarius L.), major pest of the stored cereals. UASVMCN-AGR 66, 59–66 (2009).

Aznar-Fernández, T., Cimmino, A., Masi, M., Rubiales, D. & Evidente, A. Antifeedant activity of long-chain alcohols, and fungal and plant metabolites against pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) as potential biocontrol strategy. Nat. Prod. Res. 33, 2471–2479 (2019).

Zhang, W. et al. Two new coumarins from Zanthoxylum dimorphophyllum spinifolium and their feeding deterrent activities against Tribolium castaneum. Ind. Crops Prod. 143, 111889 (2020).

Larson, N. R., O’Neal, S. T., Bernier, U. R., Bloomquist, J. R. & Anderson, T. D. Terpenoid-Induced feeding deterrence and antennal response of honey bees. Insects 11, 83 (2020).

Kerebba, N., Oyedeji, A. O., Byamukama, R., Kuria, S. K. & Oyedeji, O. O. Evaluation for feeding deterrents against Sitophilus zeamais (Motsch.) from Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) A. Gray. J. Biologically Act. Prod. Nat. 12, 77–93 (2022).

Jackowski, J. et al. Deterrent activity of hops flavonoids and their derivatives against stored product pests. Bull. Entomol. Res. 107, 592–597 (2017).

Brozdowski, J. et al. Phenolic composition of leaf and flower extracts of black Cherry (Prunus Serotina Ehrh). Ann. For. Sci. 78, 66 (2021).

Olszewska, M. A. & Kwapisz, A. Metabolite profiling and antioxidant activity of Prunus padus L. flowers and leaves. Nat. Prod. Res. 25, 1115–1131 (2011).

Kivilompolo, M., Obůrka, V. & Hyötyläinen, T. Comparison of GC–MS and LC–MS methods for the analysis of antioxidant phenolic acids in herbs. Anal. Bioanal Chem. 388, 881–887 (2007).

Guerra-Ramìrez, D., Hernández Rodríguez, G., Espinosa- Solares, T. & Perez-Lopez, A. Salgado-Escobar, I. Antioxidant capacity of Capulin (Prunus Serotina subsp. Capuli (Cav). McVaugh) fruit at different stages of ripening. Ecosist Recur Agropec. 6, 35–44 (2019).

Palomares-Alonso, F. et al. In vitro and in vivo cysticidal activity of extracts and isolated Flavanone from the bark of Prunus serotina: A bio-guided study. Acta Trop. 170, 1–7 (2017).

Ibarra-Alvarado, C. et al. Vasorelaxant constituents of the leaves of Prunus serotina capulín. Revista Latinoam. De Química. 37, 164–173 (2009).

Abdulhay, H. S. Insecticidal activity of aqueous and methanol extracts of apricot Prunus armeniaca L. Kernels in the control of Tribolium confusum. Al-Mustansiriyah J. Sci. 26, 7–18 (2012).

Aziz, S. Habib-ur-Rahman. Biological activities of Prunus persica L. batch. J. Med. Plants Res. 7, 947–951 (2013).

Erdoğan, P. Insecticidal Effect of Different Plants Extracts Against Wheat Weevil, Sitophilus granarius (L., 1985) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). AJE (2023). https://doi.org/10.11648/j.aje.20230703.12

Emsen, B., Yildirim, E. & Aslan, A. Insecticidal activities of extracts of three lichen species on Sitophilus granarius (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Plant. Prot. Sci. 51, 155–161 (2015).

Wang, R. et al. Toxicity, baseline of susceptibility, detoxifying mechanism and sublethal effects of chlorogenic acid, a potential botanical insecticide, on Bemisia tabaci. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1150853 (2023).

Upasani, S. M., Kotkar, H. M., Mendki, P. S. & Maheshwari, V. L. Partial characterization and insecticidal properties of Ricinus communis L foliage flavonoids. Pest Manag. Sci. 59, 1349–1354 (2003).

Zhang, X. Y., Shen, J., Zhou, Y., Wei, Z. P. & Gao, J. M. Insecticidal constituents from Buddlej Aalbiflora Hemsl. Nat. Prod. Res. 31, 1446–1449 (2017).

Zagrobelny, M. et al. Cyanogenic glucosides and plant–insect interactions. Phytochemistry 65, 293–306 (2004).

Park, D., Peterson, C., Zhao, S. & Coats, J. R. Fumigation toxicity of volatile natural and synthetic cyanohydrins to stored-product pests and activity as soil fumigants. Pest Manag. Sci. 60, 833–838 (2004).

Kijevčanin, M. L. et al. Modeling of volumetric properties of organic mixtures based on molecular interactions. in Molecular Interactions (InTech, doi:https://doi.org/10.5772/36110. (2012).

Hikal, W. M. & Baeshen, R. S. Said-Al ahl, H. A. H. Botanical insecticide as simple extractives for pest control. Cogent Biology. 3, 1404274 (2017).

Funding

The APC/BPC was funded by the Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences. This work was supported by the Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences (Poland) as part of the research project no N0N00000/0241/24/2024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PB developed the concept and design of the study. PB, JŁ, IG and JT developed a detailed methodology. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by PB, JŁ, KT and MI. The first draft of the manuscript was written by PB, JŁ, IG, JT and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

No licences or permits were required for these experiments.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bączek, P., Łyczko, J., Twardowska, K. et al. Antifeedant activity of invasive Prunus serotina leaves methanolic extract against Sitophilus granarius, a pest of stored products. Sci Rep 15, 25469 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10326-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10326-1