Abstract

Scytonemin, a UV-protective pigment produced by cyanobacteria, is essential for microbial survival under extreme solar radiation. Recent studies suggest its structural analog, scytonemin imine, may serve as a biosynthetic marker for cyanobacteria exposed to intense light. Here, we present a structural revision, revealing scytonemin imine as a cyclic hydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole, rather than the previously proposed primary imine. This reassignment is supported by 1D and 2D NMR, Q-TOF mass spectrometry, confirmatory synthesis, and DFT calculations. Our synthesis demonstrates that scytonemin converts to scytonemin imine under mild conditions–ammonia and acetone exposure–suggesting the imine adduct is likely an artifact of isolation. However, our findings also indicate that this artifact may reveal a previously unrecognized in-vivo state of scytonemin, which is released upon condensation with acetone. This reactivity uncovers a new chromism within the scytonemin scaffold, supporting the idea that biogenic scytonemin analogs may filter visible light to regulate photosynthesis and protect against ROS-mediated photodamage during high light exposure or desiccation. This chromatic transformation highlights scytonemin’s structural adaptability, offering insight into its role as a protective pigment in ancient and modern cyanobacteria and its relevance for understanding microbial adaptation to extreme environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery and characterization of microbial pigments hold significant implications for understanding life’s resilience on Earth and detecting potential biosignatures in extraterrestrial environments1,2. Pigments such as scytonemin, mycosporin-like amino acids (MAAs), and lichen-derived acids, produced by extremophiles, play critical roles in survival mechanisms, providing protection against UV radiation and oxidative stress3,4,5,6. These compounds serve as multifunctional UV protectants and reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavengers, offering insights into microbial resistance and suggesting their potential as biosignatures in astrobiology7,8. As such, pigments can serve as “smoking gun” indicators of life, particularly on planets where conditions resemble early Earth. In astrobiology, the spectral signatures of pigments–detectable by technologies like Raman spectroscopy–make them prime targets for remote sensing and in-situ analysis on planetary missions. However, a nuanced understanding of both biotic and abiotic pigment origins and their reactivity is essential to avoid misinterpreting data, especially in harsh environments like Mars. The evolving adaptability of microbial pigments to environmental stresses, such as UV radiation and oxidative conditions, may offer clues to how life might survive on other worlds. Scytonemin (1) is a microbial pigment that is implicated in UV protection of organisms that existed on early Earth Fig. 19,10. This pigment is almost exclusively localized to the extracellular polysaccharide sheath (EPS) of cyanobacteria and possesses strong broadband UV absorption and antioxidant properties6,11,12,13,14,15,16. The production of this pigment by the organism is highly inducible under UV exposure and is replenished by cyanobacteria after selective extraction of the pigment from extracellular tissue17,18,19. Scytonemin (1) has been established as a key trait for survivability under prolonged exposure to lethal levels of UV light, and its production is shared by many taxa of cyanobacteria. Phylogenetic estimates suggest that it was produced by crown species of cyanobacteria at least 2.1 billion years ago20. This body of evidence has led researchers to suggest that the pigment evolved on early Earth cyanobacteria, and the redox and UVA/B absorption characteristics are likely why it persists in modern cyanobacteria. This has prompted numerous chemical studies to search for related pigments across extremophilic cyanobacteria taxa, which might provide insights into the characteristics of life that can resist intense UV radiation, similar to conditions on early Earth. However, the isolation and characterization of these pigments can be highly challenging due to their low concentrations and complex structures. For example, the structure of gloeocapsin, a red pigment from cyanobacteria, remains only tentatively assigned despite its repeated discovery since 1877, highlighting the difficulties in fully characterizing pigments in these systems21. Since the structural elucidation of scytonemin (1) by Gerwick and Proteau in 1993, only a few structural analogs have been isolated and characterized10,22,23. Their origins have been suggested to arise from environmental stimuli, such as high levels of iron and high incident light. One such structural analog, previously isolated and structurally assigned as scytonemin imine (2a), formally constitutes an acetone imine conjugate of scytonemin (1, Fig. 1). Scytonemin imine was first isolated in 2012 from Scytonema hoffmani grown under high-intensity solar radiation (300–1500 \(\upmu\)mol quanta m\(^{-2}\) s\(^{-1}\)) and was proposed as a biosynthetic marker for cyanobacteria grown under these conditions22. However, it is well established that primary imines, such as the originally proposed structure of scytonemin imine (2a), are highly unstable in aqueous conditions and would rapidly hydrolyze to the corresponding ketone under the extraction and isolation conditions (not observed). Given this consideration, we re-isolated, re-evaluated, and re-assigned the structure of scytonemin imine (2a) as the cyclic imine scytonemin hydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole (2b) based on full characterization of this pigment by 1D and 2D nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic analysis, electrospray quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (ESI-Q-TOF MS), comparison to density functionalized theory (DFT) calculations of \(^{13}\)C and \(^1\)H chemical shift values, and confirmatory total synthesis (Fig. 1). Our synthetic studies show that scytonemin (1) can convert into scytonemin imine (2b) by treatment with ammonia and acetone, indicating a previously un-described chromism property of the scytonemin skeleton. This property may allow adaptation to different solar radiation and regulate photosynthesis. While this conversion might not reflect the exact biogenic structure or origins of scytonemin imine (2b), our findings suggest that the structural adaptability of scytonemin could predict how microbial life on other habitable planets might accommodate rapidly changing environmental conditions, such as variations in light, atmospheric composition, redox, and pH environments; factors that are essential to the resilience of life forms to survive extreme and changing conditions. Our work emphasizes the importance of detailed chemical studies in understanding the ecological roles of pigments and their relevance as biosignatures for astrobiological research. Understanding these mechanisms may shed light on the evolutionary pressures that shaped life on early Earth and provide key insights into how similar life forms could exist on exoplanets.

A picture of a solution of the sample of re-isolated scytonemin imine and its UV-Vis spectrum in acetonitrile. Structures of scytonemin (1), the revised structure of scytonemin imine (2b) and the originally assigned structure (2a). Created in BioRender. Jeffrey, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/40l9rz0.

Results

Re-isolation of scytonemin imine and confirmation of identical spectra

Scytonemin imine was extracted from commercially available Nostoc flagelliforme through continuous extraction of pulverized dry cyanobacteria with acetone. Purification using preparative thin-layer chromatography (prep-TLC on silica gel) led to the isolation of a mahogany-colored compound, which exhibited the identical tandem LC-QTOF mass spectrometry characteristics, FT-IR, and UV-Vis spectra as previously reported (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs. S2 and S8). UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS analysis showed that the re-isolated scytonemin imine exhibited the identical high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) molecular ion [m/z = 602.2074, calcd’ for \({\hbox {C}_{39}\hbox {H}_{28}\hbox {N}_{3}\hbox {O}_{4}}\) [M+H]\(^+\), found 602.2085] major fragment corresponding to the neutral loss of acetone imine [m/z = 545.1496, ([M-H]\(^+\)-\({(\hbox {C}_{3}\hbox {H}_{7}\hbox {N})}\)], indicating that the scytonemin imine originally reported by Grant and Louda had been re-isolated (Suppletmentary Fig. S2). 1D and 2D NMR analysis (900 MHz, DMSO-d\(_6\)) revealed the characteristic diastereotopic methylene doublets (\(\delta\)H 3.71 and 3.24, J = 18.9 Hz, \(\delta\)C 54.0) that were also reported previously and assigned to the \(\alpha\)-position (C-17) of the acetone imine adduct. In addition to these diagnostic signals, the resonances of the aromatic protons, 4-exchangeable protons (singlets, \(\delta\)H 11.94, 10.24, 10.16, and 6.86), and a methyl singlet (\(\delta\)H 1.91, \(\delta\)C 19.9) were all consistent with the previously isolated compound named scytonemin imine. However, the hydrolytic instability of the primary imine functionality of the reported structure of scytonemin imine 2a, reevaluation of the 1D and 2D NMR data, and computational analysis revealed significant inconsistencies with the originally proposed structure of scytonemin imine and prompted the reevaluation of the structure.

Key 1D and 2D NMR re-evaluation leading to the revision of the structure of scytonemin imine

Our structural reassignment first focused on the C-1–C-19 indoline core, which contains the acetone imine motif that distinguishes scytonemin imine. Key (\(^1\)H\(\rightarrow\) \(^{13}\)C) heteronuclear multi-bond coupling (HMBC) between the H-17 diastereotopic proton resonances (\(\delta\)H 3.71 and 3.24, J = 18.9 Hz, \(\delta\)C 54.0 ppm) and the H-19 methyl group (\(\delta\)H 1.91, \(\delta\)C 19.9) to the C-18 imine resonance (\(\delta\)C 173.1) support an acetone imine-derived functionality (Fig. 2). However, further examination of the HMBC correlations and \(^{13}\)C chemical shift values at the C-3a and C-8b positions supported an alternative connectivity of a cyclic imine structure, scytonemin hydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole 2b (Fig. 2). The strongest experimental evidence for this rearranged connectivity was provided by HMBC correlations between the diastereotopic methylene resonances of C-17 and the indoline carbon C-8a (\(\delta\)C 133.6), as well as shared correlations between H-5 of the indoline (\(\delta\)H 6.52, \(\delta\)C 109.9) and C-8b (\(\delta\)C 62.2). Additionally, chemical shift values for C-3a (\(\delta\)C 104.8) are more consistent with an N,N-substituted carbon rather than a quaternary nitrogen carbon as previously assigned (\(\delta\)C 63.5). We have reassigned this \(\delta\)C 62.2 resonance to C-8b based on the revised HMBC couplings. Additional HMBC correlations also allowed us to assign the exchangeable protons and further support the connectivity of the imine. The exchangeable \(^1\)H resonance at 11.9 ppm was assigned to the indole N(1’)-H, supported by HMBC couplings to C-3’a (\(\delta\)C 149.2), C-8’a (\(\delta\)C 126.4), and C-8’b (\(\delta\)C 123.2). The remaining indoline N(1)H proton was assigned to the exchangeable \(^1\)H resonance at 6.86 ppm, which exhibited HMBC couplings to the quaternary bridgehead C-3a (\(\delta\)C 104.8) and C-8b (\(\delta\)C 62.2), as well as to the C-4a indole carbon (\(\delta\)C 149.7). Considering an alternative isomer of scytonemin hydropyrrolo[3,2-b]indole 2c, where the C3a-C8b connectivity is reversed, was found to be inconsistent with the expected chemical shift for a C-8b connection (\(\delta\)C > 70) and the observed HMBC correlations, supporting the connectivity of 2b over 2c. Additionally, the large geminal coupling constant value between C-17 hydrogens (J = 18.9 Hz) is consistent with values the C2 methylene of 1,3-cyclopentadieneone24. A literature search identified one structure with the overall hydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole motif, assigned to alstrobrogaline (3), as well as related cyclic pyrrolidine compounds with diastereotopic methylene resonances for comparison of the 2J geminal \(^1\)H coupling and \(^{13}\)C NMR chemical shift data (Fig. 2, right)25,26,27. The overall consistency of \(^{13}\)C chemical shift values between the alkaloid alstrobrogaline (3) and the large geminal J values of other cyclic pyrrolidine diastereotopic methylenes were consistent with the revised scytonemin imine indoline core of scytonemin hydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole 2b. Further assignment of the structure of 2b based on 1D and 2D NMR analysis was consistent with the remaining structural elements of the scytonemin core (Table 1). The stereochemistry of the styrenyl units was assigned based on NOESY correlations between the indoline NH and the C-11/15 aromatic protons, and the indole NH with C-11’/15’ protons, which supports the configuration of both styrenyl units and reinforces our assignment of the NH protons. Unfortunately, the very small amount of material (200–300 \(\upmu\)g) we were able to isolate limited the signal intensity in the 13C NMR data.

Key 2D NMR data and literature comparisons leading to the structural revision of scytonemin imine. (a) Key HMBC and NOESY couplings that led to the reassignment of scytonemin imine as 2b, including 4/5-bond HMBC couplings that are inconsistent with the originally reported structure 2a and an isomeric cyclic imine. (b) The structure of alstrobrogaline (3) with 13C chemical shift comparisons to 2b. (c) the reassigned structure of scytonemin imine (2b) with full numbering. Created in BioRender. Jeffrey, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/hdfwnqm.

DFT calculations further supporting the revised structure of scytonemin imine (2b)

To further evaluate our structural reassignment, we performed DFT calculations of the 13C and 1H chemical shifts of the originally proposed acyclic imine 2a, the revised cyclic imine 2b, and an isomeric cyclic imine 2c. The optimized geometries in DMSO were obtained using the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM). Clear inconsistencies between the calculated and experimental 13C NMR spectra are observed within the imine functionalized indoline core of the originally proposed structure of scytonemin imine 2a (Fig. 3, RMSD = 17.9 ppm and MAE = 9.74 ppm). The calculated 1H and 13C chemical shifts for the revised cyclic scytonemin imine 2b are consistent with the experimental spectra, with only minor discrepancies (Fig. 3, 13C: R2 = 0.9924, RMSD = 3.13 ppm, MAE = 1.97 ppm, 1H: R2 = 0.9941, RMSD = 0.246 ppm, MAE = 0.11 ppm). The \(^1\)H and \(^{13}\)C NMR spectra of isomeric structure 2c, with the cyclic imine unit connected through C-3a/C-8b, was also calculated and compared to experimental data (Fig. 3). The experimental and calculated 1H and 13C NMR chemical shift values for the isomeric cyclic imine 2c are more consistent than those for the originally proposed structure 2a. However, significant differences between the calculated and experimental values are observed for the key C-8b 13C chemical shift (\(\delta \Delta\) = -20.6 ppm) in isomer 2c, along with a lower overall agreement between the calculated and experimental 13C chemical shifts for 2c (Fig. 3, R2 = 0.9856, RMSD = 4.27 ppm, and MAE = 2.24 ppm). These discrepancies further support the assignment of scytonemin imine as 2b. Overall, the strong evidence from HMBC correlations, along with the support from computational modeling, corroborate our revised structure for scytonemin imine as 2b.

DFT calculated NMR chemical shift values support the structural revision of scytonemin imine 2b compared to the originally reported structure 2a and another potential isomer 2c. Correlations between the experimental and calculated NMR chemical shift values for (a) originally proposed structure 2a; (b) isomeric cyclic structure 2c; and (c) reassigned structure 2b. Created in BioRender. Jeffrey, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/u2cwejt.

A confirmatory synthesis of scytonemin and conversion to scytonemin imine

To evaluate the newly proposed structure and the relationship between scytonemin and scytonemin imine, we pursued a concise total synthesis of scytonemin and ultimately scytonemin imine 2b. Tryptophan (4) was efficiently converted to the trifluoro oxazolone 5 using trifluoroacetic anhydride in ether28. Friedel-Crafts cyclization using \({\hbox {AlCl}_3}\) provided the trifluoroacetamide 6, which was efficiently oxidized using copper (II) bromide to the diketone 7 (Fig. 4)29. Selective addition of the Grignard to the C-3 ketone provided a mixture of the tertiary alcohol 9 and desired monomer 8, which the alcohol could be further converted to the alkene under mild conditions. We expect that the selective addition of the benzyl Grignard was supported by enolization of the C-2 ketone by an equivalent of the organometallic reagent. Dimerization of the monomer 8 was completed following similar conditions to the Mårtensson group to form the doubly reduced dimethoxy scytonemin 10, which was deprotected using \({\hbox {BBr}_3}\) and oxidized using 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ) to form scytonemin (1)30. The relationship between scytonemin (1) and scytonemin imine (2a) suggests a reaction of the oxidized form of scytonemin with ammonia and acetone by nucleophilic attack at the C-3b and C-8b positions. Treatment of scytonemin (1) with aqueous ammonia in acetone produced scytonemin imine (2a) that demonstrated identical spectroscopic data to the isolated sample, thereby further confirming our structural reassignment. With the material accessed by synthesis, we were able to assign the additional carbon resonances that were undetectable in the isolated sample. Additionally, our studies revealed a dramatic solvent dependence on both the chemical shift and broadness of the \(^1\)H NMR resonances, specifically related to the H11’/H15’ AB quartet of the para-substituted phenol, which is a newly observed solvatochromic behavior for the scytonemin scaffold (Supplementary Fig. S1).

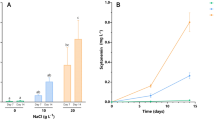

Extraction experiments to evaluate the biogenic origins of scytonemin imine (2a)

Given the facility by which scytonemin (1) is converted to scytonemin imine (2b) we conducted control experiments to evaluate the biogenic origins of scytonemin imine (2b). Ground tissue was subjected to extraction with acetonitrile, acetone, and acetone-\({d_{{\textit{6}}}}\) and analyzed using UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. Acetonitrile extracts did not provide detectable quantities of scytonemin imine (2b) and resulted in the detection of scytonemin (1). Analysis of the acetone and acetone-\({d_{{\textit{6}}}}\) extracts revealed detectable signal for scytonemin imine (2b) and a deuterium enriched analog respectively, suggesting that the origins of hydropyrrolo[2,3-b] moiety to be associated with the acetone extraction solvent (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Discussion

Our results provide strong evidence for the structural reassignment of scytonemin imine as the hydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole (2b). This reassignment is supported by spectroscopic analysis and the comparison of calculated NMR and UV-Vis spectra. Additionally, the confirmatory total synthesis of scytonemin imine (2b) via a condensation reaction demonstrates that scytonemin (1) readily converts to the imine in the presence of ammonia and acetone. Furthermore, our control extraction experiments suggest that the extraction solvent is likely the source of the carbon portion of the imine moiety. Acetone is widely recognized as an effective solvent for extracting scytonemin pigments from cyanobacterial tissue. However, our control experiments and synthetic studies suggest that scytonemin imine (2b) may be an artifact of the isolation process9,22. These results demonstrate that ammonia and acetone readily convert scytonemin (1) into scytonemin imine (2b), though the precise mechanism remains unclear. One possibility is that nucleophilic attack on the scytonemin skeleton occurs via an enamine or ketimine intermediate, formed by the condensation of ammonia and acetone during extraction yielding scytonemin hydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole (2b, Fig. 5). The susceptibility of scytonemin (1) to nucleophilic attack in its oxidized form suggests that it may be covalently linked to biomolecules within the exopolysaccharide (EPS) sheath, where it has been established to co-localize with Water Stress Protein A (WSPa) and other biomolecules due to its high lipophilicity11,31,32,33,34. A potential scytonemin imine precursor could be covalently bound to an EPS biomolecule, such as an amino glycoside and/or a peptide/protein, and exchange upon treatment with acetone. Louda and Grant observed that scytonemin imine was only extracted from field-collected and cultured cyanobacteria samples that grew under intense light. This, along with our report, points towards in-vivo formation of the unidentified precursor to scytonemin imine, which subsequently converts to scytonemin imine upon acetone extraction22. Though there is no confirmed evidence of the presence of a scytonemin derivative of this type, Louda and Grant reported a polar HPLC peak that eluted earlier than scytonemin (1) and the imine that demonstrated similar UV-Vis absorption characteristics to scytonemin imine (2a), though its low abundance hindered full characterization. During our own isolation of scytonemin imine (2b), we observed evidence suggesting acetone reacts with a more polar scytonemin derivative. LC-Q-TOF analysis of preparative TLC (SiO2) fractions identified a polydeuterated derivative of 2b after this band was taken up into acetone-d6 for 1H NMR analysis. This derivative exhibited neutral loss of the ketimine, with the highest deuterium distribution within this fragment, supporting its formation during acetone treatment. However, its low abundance precluded full structural characterization by NMR. Regardless of the precise mechanistic origins, the presence of scytonemin imine (2b), whether as a biogenic or a partial isolation artifact, our re-isolation and chemical synthesis indicates a facile mode of reactivity for the oxidized form of scytonemin (1). This reactivity, revealed through the formation of the acetone adduct, also uncovers a novel chromism of scytonemin. This is consistent with Garcia-Pichel’s observation that the UV-Vis spectrum of scytonemin (1) is highly sensitive to various conditions, including solvent, and their hypothesis that scytonemin exists in multiple forms in-vivo depending on redox state and pH; differences in spectral properties could also be linked to specific interactions between the pigment and sheath polymers9,14,16. Louda and Grant also postulated that scytonemin imine (2b) could function as a visible light screen, absorbing key bands of photosynthetically active light at the \(\alpha /\beta\) bands of the cytochromes (531–532 nm and 560–562 nm) and the Soret bands of both the cytochromes and chlorophyl-a (450 nm)22. This chromism could serve as a protective mechanism, slowing photosynthesis by filtering PAR and preventing photodamage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) during periods of high light intensity and desiccation35,36,37. Additionally, our research points to the solvatochromatic properties of syctonemin imine, which could provide additional ecologically relevant chromism for the scytonemin imine and related molecules and their potential biosynthetic precursor(s) in vivo, and demonstrate that the chromaphore is highly sensitive to the environment. Ongoing research is aimed at identifying other scytonemin analogs, understanding their photochemical behaviors, and their ecological relevance to scytonemin-producing cyanobacteria. In conclusion, microbial pigments like scytonemin offer valuable insights into the survival mechanisms of extremophiles and their potential as biosignatures in astrobiological research. These pigments, which function as both UV protectants and reactive oxygen species scavengers, demonstrate the evolutionary adaptations that allowed life to persist under extreme conditions on early Earth. The spectral properties of pigments such as scytonemin, detectable via advanced technologies like Raman spectroscopy, make them ideal candidates for remote sensing in planetary exploration missions. However, the complexity of these pigments–arising from their low concentrations and intricate structures–poses significant challenges for isolation and characterization. The re-isolation and re-characterization of scytonemin imine, along with the revised structural assignment, highlights the chemical adaptability of scytonemin. Our findings suggest that scytonemin’s conversion to scytonemin imine under simple conditions such as exposure to ammonia and acetone points to a previously unrecognized chromism property and reactivity, allowing this pigment to adapt to varying solar spectra. This adaptability might offer important clues about how microbial life on other habitable planets could survive under fluctuating environmental conditions, such as changes in light, atmospheric composition, redox states, and pH levels. By deepening our understanding of the structural and functional properties of these pigments, we not only expand our knowledge of life’s resilience but also enhance the search for biosignatures on exoplanets. The chemical studies of scytonemin and its analogs emphasize the broader ecological roles of microbial pigments and their potential in guiding future astrobiological discoveries.

A scheme showing the biogenic hypothesis for the formation of scytonemin imine (2b) from condensation with a scytonemin amine derivative and/or an in-vivo covalently bound scytonemin analog. Created in BioRender. Jeffrey, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/s93xnl4.

Methods

Extraction and re-isolation of scytonemin imine

The compound was isolated from a dried sample of Nostoc flagelliforme. Biomass purchased was sold as fat choy (Asian Mart, Reno, NV) and was extracted without further treatment. 120 grams dry biomass was ground up using mortar and pestle. Sample was extracted three times overnight with acetone at room temperature with continuous stirring. Extracts were combined and dried in-vacuo. The resulting crude extract (60 mg) was subjected to preparative thin-layer chromatography (silica gel 60, 20 cm \(\times\) 20 cm, 1000 \(\upmu\)m) with a 45:55 acetone:hexane mobile phase. This resulted in a prominent mahogany red band which was recovered from the silica gel stationary phase with acetone. This fraction was subjected to size exclusion chromatography on a Sephadex LH-20 (Supleco) column with acetone mobile phase. Chromatographic parameters: bed volume = 50 mL, column height = 14.5 cm, internal diameter = 2.1 cm, flow rate = 17.3 mL/h, linear flow rate = 5 cm/h. 10 fractions of volumes 12, 14, 13, 8, 14, 14, 16, 17, 16 and 18 mL respectively were collected; of which fractions 6 and 7 yielded 300 \(\upmu\)g of scytonemin imine. These fractions were combined and dried in-vacuo for subsequent analyses.

Control extractions with acetonitrile, acetone, and acetone-d 6

For confirmatory small scale extractions, separate 100 mg samples of ground biomass were extracted in 5 mL of acetonitrile, acetone, and acetone-d6 for 24 hr at room temperature under continuous stirring. Samples were prepared for mass spectrometry analysis by filtering 1 mL of each extracts through a membrane filter (0.45 \(\upmu\)m), drying in-vacuo and redissolving the residue in 10 mL acetonitrile.

Spectroscopic analyses

UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS Analysis

Extracts were injected (10.00 \(\upmu\)L) on an Agilent 1290 Infinity II UPLC equipped with a binary pump, temperature controlled multisampler (4 \(^{\circ }\)C), temperature controlled column compartment (40 \(^{\circ }\)C) and diode array UV/Vis detector (\(\lambda\) = 190-800 nm), coupled to an Agilent 6560 Ion Mobility Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (IM-QTOF) mass spectrometer via a Jet Stream electrospray ionization source (ESI-TOF; gas temperature: 300 \(^{\circ }\)C, flow: 11 L/m; nebulizer pressure: 35 psig; sheath gas temp: 300 \(^{\circ }\)C; sheath gas flow: 12 L/m; VCap: 3500 V; nozzle voltage: 500V; fragmentor: 350 V; skimmer: 65 V; octopole: 750 V). For LC-MS/MS, data were collected in positive data-dependent MS/MS mode with collision energies set to 20 and 40 eV per duty-cycle and for LC-TOF, samples were re-run in 4-bit multiplexed IM-TOF mode at 1 frame/s. Multiplexed ion mobility spectra were demultiplexed using the PNNL ion mobility pre-processor,38 and spectra were calibrated to reference mass standards for collisional-cross-section (\(\Omega\), Å2) determinations. All organic solvents and mobile phase modifiers were Fisher Optima grade. Mobile phase solvents consisted of 18 M\(\Omega\) water (solvent A) and 99% acetonitrile (aq, solvent B), both modified by adding 0.1% formic acid. Reverse-phase (RP) chromatography was conducted using an Agilent Poroshell EC-C18 column (2.1\(\times\) 50 mm, 1.9 \(\upmu\)m). The RP gradient for both solvent compositions (0.4 mL/min) began with initial conditions of 20% B, ramp to 100%B (0-15 min), ramp to 20% B (15-16 min), recondition column at 20% B (16 min–18 min). Scytonemin (\({\hbox {C}_{36}\hbox {H}_{20}\hbox {N}_2\hbox {O}_4}\), 8.86 min; \(\Omega\) = 245.3 Å2; m/z = 545.1486 Da [M+H]+, -1.8 ppm) and scytonemin imine (\({\hbox {C}_{39}\hbox {H}_{28}\hbox {N}_3\hbox {O}_4}\), 6.10 min; \(\Omega\) = 257.1 Å2; m/z = 602.2085 Da [M+H]+, +1.8 ppm) were both observed in cyanobacterial extracts.

1D and 2D NMR analysis

For the re-isolated scytonemin imine (2b), 1H and 13C NMR data were acquired on a Bruker Advance III HD 900 MHz NMR equipped with a CNH TXO CryoProbe. 1H and 13C NMR data for synthetic samples and intermediates were acquired using a Agilent PremiumCompact+ 500 MHz with a Varian SW/PFG broadband probe at 300K, and calibrated to residual proton solvent signals. Chemical shift values are in \(\hbox {CDCl}_{3}\) are reported relative to \({\hbox {SiMe}_4}\) (\(\delta\)H 0 ppm) as an internal standard for 1H, and referenced to the residual solvent signal for 13C (\(\delta\)C 77.16). Chemical shifts in acetone-\({d_{{\textit{6}}}}\) and DMSO-d6 were referenced to the residual protonated solvent signal for 1H NMR [\(\delta\)H = 2.05 ppm (acetone-\({d_{{\textit{6}}}}\)) and \(\delta\)H = 2.50 ppm(DMSO-d6] and 13C NMR [\(\delta\)C = 29.84 ppm (acetone-d6) and \(\delta\)C = 39.52 ppm (DMSO-d6)]. 1D and 2D NMR experiments are reported in the supporting information along with copies of the NMR spectra. Optical Spectroscopy The UV visible spectra were recorded on a Lambda 25 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer) in a 1 cm quartz cell. The FTIR spectrum was recorded on a Nicolet 6700 (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a MCT-A detector and KBr beam splitter at \(25 ^{\circ }\hbox {C}\). All spectra were collected over 650-4000 cm-1 at a resolution of 2 cm-1 and 144 scans.

DFT calculations

The equilibrium geometries of 2a, 2b, and 2c were obtained using the unrestricted B3LYP functional and the def2-SVP basis set. All three geometries were optimized in gas phase as well as in acetone, acetonitrile, and DMSO. To simulate the solvent environments, the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) was used. The optimized geometries were confirmed to correspond to minima on the potential energy surfaces by performing the vibrational analysis. The 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts were calculated in acetone and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) using the revTPSS functional in combination with the pcSseg-2 basis set.39,40 The UV-Vis and CD spectra were calculated in acetonitrile using the B3LYP functional and def2-TZVP basis set. All electronic structure calculations were performed with the ORCA 5.0 electronic structure package.41

Methods for the synthesis of scytonemin imine 2b

4-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)-5(4H)oxazolone (5)28

Tryptophan (10.2 g, 50 mmol) was added to trifluoroacetic anhydride (16.6 mL, 120 mmol) in ether (100 mL) at 0 \(\circ\)C during which an exothermic reaction was initiate. The reaction was allowed to re-cool upon which time it was removed from the ice bath and stirred at room temperature at which point the solid had gone into solution. The reaction flask was then placed in the freezer overnight to initiate precipitation. The precipitate was filtered, and re-precipitated by adding hexanes to the mother liquor and evaporated under reduced pressure until additional precipitate was observed and the reaction solution was filtered again. Iterative precipitation yielded 5 as a pale yellow solid (12.2 g, 86%) which was used in the next step without further purification. HRESIMS (calc’d for 282.0616 \(\hbox {C}_{13} \hbox {H}_9 \hbox {F}_3 \hbox {N}_{2}\hbox {O}_{2}\) [M+H]\(^{+}\), found 282.2790).

(S)-2,2,2-Trifluoro-N-(1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-3-oxocyclopenta[b]indol-2-yl)acetamide (6)29

The oxazolone 5 (6.2 g, 22 mmol) was added all at once to a stirred mixture of aluminum chloride (5.8 g, 44 mmol) in degassed dichloroethane (161 mL), and stirring was continued at room temperature under nitrogen for 2h. Reaction was quenched with sodium potassium tartrate and ethyl acetate was added until solution separated into two layers after mixing. Liquid-liquid extraction using ethyl acetate (3\(\times\) 50 mL), the organic layer dried with \({\hbox {MgSO}_4}\) and concentrated under vacuum. The resulting solid was dissolved in a minimal amount of ethyl acetate and then hexanes was added until a cloudy white precipitate formed, and the solution was put in the freezer. The solid was filtered yielding 6 as a colorless solid (4.03 g, 65%) and used without further purification. \(^1\)H NMR (500 MHz, d\(_6\)-DMSO) \(\delta\) 11.86 (s, 1H), 9.98 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.52–7.44 (m, 1H), 7.39 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.0, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (ddd, J = 8.0, 6.9, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (ddd, J = 8.3, 6.9, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (dd, J = 16.3, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.97 (dd, J = 16.2, 3.4 Hz, 1H). \(^{13}\)C NMR (126 MHz, d\(_6\)-DMSO) \(\delta\) 189.42, 156.95, 156.66, 144.14, 142.02, 136.86, 127.65, 123.17, 121.98, 120.77, 114.15, 58.69, 27.82. HRESIMS (calculated 283.0616 m/z \({\hbox {C}_{13}\hbox {H}_{9}\hbox {F}_{3}\hbox {N}_{2}\hbox {O}_2}\), found 283.0695 m/z)

1,4-Dihydrocyclopent[b]indole-2,3-dione (7)29

Copper(II) bromide (6.18 g, 27.7 mmol) was added in one batch to a refluxing solution of ketoamide (3.25 g, 11.5 mmol) in ethyl acetate (237 mL, 0.048 M) for 2 h. The mixture was cooled, and the organic layer was washed with a dilute NaCl solution, then brine, dried over \({\hbox {MgSO}_4}\), and filtered. The solvents were evaporated in-vacuo to give a solid. The solid was dissolved in minimal methanol, ether was added and the mixture was placed in the freezer overnight to stimulate precipitation. The solid was filtered through plug silica gel using 2:1 hexanes:ethyl acetate yielding the pure diketone 7 (3.57 g, 70%) \(^1\)H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d\(_6\)) \(\delta\) 12.28 (s, 1H), 7.80 (dd, J = 8.1, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.53–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.21 (ddd, J = 8.0, 4.5, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 3.63 (s, 2H). \(^{13}\)C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d\(_6\)) \(\delta\) 200.87, 175.24, 163.34, 142.62, 141.08, 140.53, 130.18, 123.34, 123.27, 121.67, 114.28, 32.92. (+/-)-HRESIMS (calculated 186.0510 m/z \({\hbox {C}_{11}\hbox {H}_{7}\hbox {NO}_2}\), found 186.0553 m/z).

3,4-Dihydro-3-[(4-methoxyphenyl)methylene]cyclopent[b]indol-2(1H)-one (8)

A solution of the diketone 7 (1.11 g, 6 mmol) in THF (111 mL) was added to a solution of 4-methoxybenzyl magnesium chloride (48 mL, 12 mmol, 0.25M) at \(-78 ^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) and let warm to room temperature and stirred and additional 4 hours. After which the reaction was quenched at room temperature with aq. HCl (3M) and extracted with EtOAc (3\(\times\)50 mL) and the combined organic layers were washed with brine and dried with \({\hbox {NaSO}_4}\). The alkene was purified using flash chromatography eluting around 3:1 hexanes:ethyl acetate, yielding the monomer 8 as yellow solid (525 mg, 30%) \(^1\)H NMR (400 MHz, \({\hbox {CDCl}_{3}}\)) \(\delta\) 7.61–7.57 (m, 1H), 7.56–7.51 (m, 1H), 7.37–7.31 (m, 1H), 7.27–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.16 (s, 1H), 7.15–7.12 (m, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (s, 2H), 3.54 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, \({\hbox {CDCl}_3}\)) 204.55, 160.32, 140.16, 138.83, 129.56, 128.74, 127.82, 124.32, 124.26, 124.24, 120.92, 120.32, 119.78, 114.77, 111.82, 55.45, 36.47. (+/-)-HRESIMS (calculated 290.1136 m/z /ceC19H15NO2, found 290.11811 m/z).

Tetrahydroscytonemin dimethyl ether (10)

The monomer 8 (86.8 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1 equiv) in THF (7.5 mL) was added dropwise to a solution lithium diisopropyl amide in THF (0.375 mL, 2.0M, 2.5 eq.) at \(-78 ^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) and a change in color from yellow to deep red was observed. The solution was stirred for 10 min after addition of the LDA and a solution of \({\hbox {FeCl}_3}\) (107.05 mg, 0.66 mmol, 2.2 equiv) in DMF (3.7 mL) was added dropwise. The resulting mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for an additional 24 h before being quenched with aqueous HCl (1 M, 1x reaction volume). The quenched reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3x reaction volume) and the combined extracts were washed with 10 % aqueous LiCl (5x volume of DMF) and brine (1x reaction volume), dried over \({\hbox {MgSO}_4}\), filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to a brown solid. Purified using flash column chromatography eluting at 1:1 Hex: EtOAc. Yielding 33 mg (18%) 1H NMR (500 MHz, \({\hbox {CDCl}_3}\)) \(\delta\) 7.99 (s, 2H), 7.49–7.43 (m, 4H), 7.36 (s, 2H), 7.30 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 7.13 – 7.07 (m, 2H), 7.06–7.01 (m, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H), 6.89 (ddd, J = 8.1, 7.0, 1.1 Hz, 2H), 4.55 (s, 2H), 3.87 (s, 6H). \(^{13}\)C NMR (126 MHz, \({\hbox {CDCl}_3}\)) \(\delta\) 206.93, 160.34, 140.70, 138.75, 132.95, 129.63, 129.60, 128.74, 127.52, 125.04, 124.07, 123.92, 121.53, 120.97, 120.92, 120.68, 114.75, 114.62, 113.87, 111.40, 55.44, 50.25. HRESIMS (calcd’ for \({\hbox {C}_{38}\hbox {H}_{28}\hbox {N}_2\hbox {O}_4}\) [M+H]\(^+\) 577.2126 , found [M+H]\(^+\) 577.2125 m/z)

Tetrahydroscytonemin (11)

A solution of 10 (28.8 mg, 0.05 mmol) in dichloromethane (1.4 mL) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of \({\hbox {BBr}_3}\) (30 \(\upmu\)L, 0.30 mmol 6 eq.) in dichloromethane (1.2 ml) at \(-78 ^{\circ }\hbox {C}\). The resulting purple mixture was warmed to \(0 ^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) and stirred for 1 hour at that temperature. The reaction was quenched with water (10 mL), diluted with acetone (25 mL) and the resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3\(\times\)25 mL). The extracts were combined, washed with brine (15 mL), dried over \({\hbox {Na}_2\hbox {SO}_4}\), filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to a yield a black solid (25 mg, 98%), which was used in the next reaction without further purification.

Scytonemin (1)-oxidized form

The phenol 11 (24.1 mg 0.04 mmol) was dissolved in THF (1.98 mL) and a solution of DDQ (39.9 mg, 0.18 mmol 4 eq.) in THF (0.5 mL) was added. The reaction solution was stirred for 45 min, after which the reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to yield a black solid. The solid was purified using medium pressure reverse-phase chromatography [7g ODS (C18) Yamazen] and eluting with a gradient of \({\hbox {H}_2\hbox {O}}\) and \({\hbox {CH}_3\hbox {CN}}\) (10-100 %) to yield scytonemin (1) as a dark brown solid (20 mg, 83%). \(^1\)H NMR (500 MHz, acetone-d\(_6\)) \(\delta\) 8.78 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H), 7.68–7.63 (m, 5H), 7.60 (td, J = 7.6, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (td, J = 7.5, 1.1 Hz, 2H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H). \(^13\)C NMR (126 MHz, acetone-d\(_6\)) \(\delta\) 193.20, 173.53, 163.22, 138.33, 136.02, 134.70, 129.05, 126.35, 126.31, 124.82, 121.57, 115.88. (+/-)-HRESIMS (calcd’ for \({\hbox {C}_{36}\hbox {H}_{20} \hbox {N}_{2}\hbox {O}_4}\) [M+H]\(^+\) = 545.1449 , found 545.1502)

Scytonemin imine (2b)

To a solution of scytonemin (1) (6.0 mg, 0.011 mmol, 1 equiv) in acetone (2.0 mL) was added aqueous ammonia (0.149 mL, 2.204 mmol, 200 equiv). The resulting mahogany solution was stirred at room temperature and monitored by thin layer chromatography (1:1 hexanes:acetone) showed consumption of starting material ( 4 hours). Scytonemin imine (2b) was purified using reverse-phase preparatory HPLC using a gradient (\({\hbox {H}_2\hbox {O}}\):\({\hbox {CH}_{3}\hbox {CN}}\)) providing scytonemin imine (2b) as a black solid (1.5 mg, 0.002 mmol, 22.6%). \(^1\)H NMR (500 MHz, acetone-d\(_6\)) \(\delta\) 8.43 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J=7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (s, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (t, J =7.3 Hz 1H), 7.18 (ddd, J = 8.2, 7.1, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (dd, J = 8.1, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 6.20 (s, 1H), 3.80 (d, J = 19.0 Hz, 1H), 3.41 (d, J = 19.0 Hz, 1H), 2.05 (s, 3H). \(^{13}\)C NMR (126 MHz, acetone-d\(_6\)) \(\delta\) 196.44, 192.92, 175.06, 159.76, 159.31, 149.66, 137.37, 135.68, 135.06, 134.02, 130.94, 128.33, 128.31, 127.38, 126.55, 126.20, 126.12, 124.89, 124.10, 123.46, 121.22, 118.68, 116.39, 115.68, 112.62, 109.97, 109.91, 105.38, 62.89, 54.48, 18.91. HRESIMS (calculated for \({\hbox {C}_{39}\hbox {H}_{27}\hbox {N}_{3}\hbox {O}_{4}}\) [M+H]\(^+\) 602.2029, found 602.2077).

Data availability

The NMR data for the following compounds has been deposited in the Natural Products Magnetic Resonance Database (NP-MRD; www.np-mrd.org) and can be found at NP0350963 (scytonemin imine-2b) and NP0022910 (scytonemin-1)

References

Wynn-Williams, D. D., Edwards, H. G. M., Newton, E. M. & Holder, J. M. Pigmentation as a survival strategy for ancient and modern photosynthetic microbes under high ultraviolet stress on planetary surfaces. Int. J. Astrobiol. 1, 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1473550402001039 (2002).

Garcia-Pichel, F. Solar Ultraviolet and the Evolutionary History of Cyanobacteria. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 28, 321–347. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006545303412 (1998).

Gao, Q. & Garcia-Pichel, F. Microbial ultraviolet sunscreens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 791–802. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2649 (2011).

Nimse, S. B. & Pal, D. Free radicals, natural antioxidants, and their reaction mechanisms. RSC Adv. 5, 27986–28006. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ra13315c (2015).

Wada, N., Sakamoto, T. & Matsugo, S. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids and Their Derivatives as Natural Antioxidants. Antioxidants 4, 603–646. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox4030603 (2015).

Wada, N., Sakamoto, T. & Matsugo, S. Multiple Roles of Photosynthetic and Sunscreen Pigments in Cyanobacteria Focusing on the Oxidative Stress. Metabolites 3, 463–483. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo3020463 (2013).

Noetzel, R. d. l. T. & Sancho, L. G. Lichens as Astrobiological Models: Experiments to Fathom the Limits of Life in Extraterrestrial Environments. In Extremophiles as Astrobiological Models, 197–220 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2020).

Rodriguez, L. E., Weber, J. M. & Barge, L. M. Evaluating Pigments as a Biosignature: Abiotic/Prebiotic Synthesis of Pigments and Pigment Mimics in Planetary Environments. Astrobiology 24, 767–782. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2023.0006 (2024).

Garcia-Pichel, F. & Castenholz, R. W. Characterization and Biological Implications of Scytonemin, a Cyanobacterial Sheath Pigment. J. Phycol. 27, 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3646.1991.00395.x (1991).

Proteau, P. J., Gerwick, W. H., Garcia-Pichel, F. & Castenholz, R. The structure of scytonemin, an ultraviolet sunscreen pigment from the sheaths of cyanobacteria. Experientia 49, 825–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01923559 (1993).

Gao, X. Scytonemin Plays a Potential Role in Stabilizing the Exopolysaccharidic Matrix in Terrestrial Cyanobacteria. Microb. Ecol. 73, 255–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-016-0851-4 (2017).

Pathak, J. et al. Cyanobacterial Extracellular Polysaccharide Sheath Pigment, Scytonemin: A Novel Multipurpose Pharmacophore. In Marine Glycobiology (CRC Press, 2016). Num Pages: 16.

Pathak, J. et al. Cyanobacterial Secondary Metabolite Scytonemin: A Potential Photoprotective and Pharmaceutical Compound. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 90, 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40011-019-01134-5 (2020).

Irankhahi, P. et al. The role of the protective shield against UV-C radiation and its molecular interactions in Nostoc species (Cyanobacteria). Sci. Rep. 14, 19258. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70002-8 (2024).

Takamatsu, S. et al. Marine Natural Products as Novel Antioxidant Prototypes. J. Nat. Prod. 66, 605–608. https://doi.org/10.1021/np0204038 (2003).

Matsui, K. et al. The cyanobacterial UV-absorbing pigment scytonemin displays radical-scavenging activity. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 58, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.2323/jgam.58.137 (2012).

Ehling-Schulz, M., Bilger, W. & Scherer, S. UV-B-induced synthesis of photoprotective pigments and extracellular polysaccharides in the terrestrial cyanobacterium Nostoc commune. J. Bacteriol. 179, 1940–1945. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.179.6.1940-1945.1997 (1997).

Garcia-Pichel, F., Sherry, N. D. & Castenholz, R. W. Evidence for an Ultraviolet Sunscreen Role of the Extracellular Pigment Scytonemin in the Terrestrial Cyanobacterium Chiorogloeopsis sp. Photochem. Photobiol. 56, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb09596.x (1992).

Gao, X., Yuan, X., Zheng, T. & Ji, B. Promoting efficient production of scytonemin in cell culture of Nostoc flagelliforme by periodic short-term solar irradiation. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 21, 101352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biteb.2023.101352 (2023).

Garcia-Pichel, F. et al. Timing the evolutionary advent of cyanobacteria and the later great oxidation event using gene phylogenies of a sunscreen. mBio10, 1. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00561-19 (2019).

Lara, Y. J. et al. Characterization of the Halochromic Gloeocapsin Pigment, a Cyanobacterial Biosignature for Paleobiology and Astrobiology. Astrobiology 22, 735–754. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2021.0061 (2022).

Grant, C. S. & Louda, J. W. Scytonemin-imine, a mahogany-colored UV/Vis sunscreen of cyanobacteria exposed to intense solar radiation. Org. Geochem. 65, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2013.09.014 (2013).

Bultel-Poncé, V., Felix-Theodose, F., Sarthou, C., Ponge, J.-F. & Bodo, B. New Pigments from the Terrestrial Cyanobacterium Scytonema sp. Collected on the Mitaraka Inselberg, French Guyana. J. Nat. Prod.67, 678–681. https://doi.org/10.1021/np034031u (2004).

Gutowsky, H. S., Karplus, M. & Grant, D. M. Angular Dependence of Electron-Coupled Proton Interactions in CH2 Groups. J. Chem. Phys. 31, 1278–1289. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1730585 (1959).

Krishnan, P., Mai, C.-W., Yong, K.-T., Low, Y.-Y. & Lim, K.-H. Alstobrogaline, an unusual pentacyclic monoterpenoid indole alkaloid with aldimine and aldimine-N-oxide moieties from Alstonia scholaris. Tetrahedron Lett. 60, 789–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.02.018 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Pan, L., Xu, X. & Liu, Q. An efficient pyrroline annulation of glycine imine with enones. RSC Adv. 2, 5138–5140. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2RA20697H (2012).

Gerry, C. J. et al. Real-Time Biological Annotation of Synthetic Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 8920–8927. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b04614 (2016).

Bergman, J. & Lidgren, G. Reaction of tryptophan with trifluoroacetic anhydride. Tetrahedron Lett. 30, 4597–4600. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(01)80754-1 (1989).

Condie, G. C. & Bergman, J. Reactivity of \(\beta\)-Carbolines and Cyclopenta[b]indolones Prepared from the Intramolecular Cyclization of 5(4H)-Oxazolones Derived from L-Tryptophan. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 1286–1297. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.200300673 (2004).

Ekebergh, A. et al. Oxidative Coupling as a Biomimetic Approach to the Synthesis of Scytonemin. Org. Lett. 13, 4458–4461. https://doi.org/10.1021/ol201812n (2011).

Wright, D. J. et al. UV Irradiation and Desiccation Modulate the Three-dimensional Extracellular Matrix of Nostoc commune (Cyanobacteria). J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40271–40281. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M505961200 (2005).

Gao, X. et al. Characterization of two beta-galactosidases LacZ and WspA1 from Nostoc flagelliforme with focus on the latter’s central active region. Sci. Rep. 11, 18448. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97929-6 (2021).

Hill, D. R., Peat, A. & Potts, M. Biochemistry and structure of the glycan secreted by desiccation-tolerant Nostoc commune (cyanobacterium). Protoplasma 182, 126. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01403474 (1994).

Varnali, T., Edwards, H. & Hargreaves, M. D. Scytonemin: molecular structural studies of a key extremophilic biomarker for astrobiology. Int. J. Astrobiol. 8, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1473550409004455 (2009).

Ivanov, A. G., Miskiewicz, E., Clarke, A. K., Greenberg, B. M. & Huner, N. P. A. Protection of Photosystem II Against UV-A and UV-B Radiation in the Cyanobacterium Plectonema boryanum: The Role of Growth Temperature and Growth Irradiance. Photochem. Photobiol. 72, 772–779. https://doi.org/10.1562/0031-8655(2000)0720772POPIAU2.0.CO2 (2000).

Pathak, J. et al. Ultraviolet radiation and salinity-induced physiological changes and scytonemin induction in cyanobacteria isolated from diverse habitats. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem.12, 3590–3606. https://doi.org/10.33263/briac123.35903606 (2022).

Rajneesh, A. et al. Impacts of ultraviolet radiation on certain physiological and biochemical processes in cyanobacteria inhabiting diverse habitats. Environ. Exp. Bot. 161, 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.10.037 (2019).

Bilbao, A. et al. A Preprocessing Tool for Enhanced Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry-Based Omics Workflows. J. Proteome Res. 21, 798–807. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.1c00425 (2022).

De Oliveira, M. T., Alves, J., Braga, A., Wilson, D. & Barboza, C. A. Do Double-Hybrid Exchange-Correlation Functionals Provide Accurate Chemical Shifts? A Benchmark Assessment for Proton NMR. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 17, 6876–6885. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00604 (2021).

Jensen, F. Segmented Contracted Basis Sets Optimized for Nuclear Magnetic Shielding. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct5009526 (2015).

Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2, 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.81 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The published results are based upon work supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration under Grant #: 80NSSC22K1633 issued through the NASA Science Mission Directorate. T.M. was supported by a Hitchcock Center for Chemical Ecology Graduate Fellowship. This study made use of the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, which is supported by NIH grant R24GM141526. The UPLC was provided through a generous donation through the Agilent Global Academic Research Support Program (2020277). The authors thank Dr. Maksym M. Fizer for valuable comments and discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S.J., S.A.V., M.J.T. conceived the experiment(s), G.E.L., T.M., I.D.D., Y.F., C.S.P., and C.R.O. conducted the experiment(s), I.D.D. and S.A.V. conducted computational analyses, C.S.J. produced the first draft, and all authors analyzed the results, reviewed the manuscript, and contributed to the writing of this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Larson, G.E., Mahmud, T., Dergachev, I.D. et al. Structure revision of scytonemin imine and its relationship to scytonemin chromism and cyanobacterial adaptability. Sci Rep 15, 25630 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10419-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10419-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Bioprospecting cyanobacteria for UV-protectant compound scytonemin and strategies for enhanced production: A review

Journal of Applied Phycology (2026)