Abstract

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing bacteria are associated with life-threatening infections with limited treatment options worldwide. In this review, we assess the circulating ESBL-producing bacterial clones from human, animal, and environmental sources in West Africa, through a One Health approach. A systematic search in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science identified 485 records, with 38 studies analysed. Data were organized thematically and pooled prevalence estimates calculated through a random-effects meta-analysis. Results showed a 16.8% (95% CI [12.1; 22.1]) prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria, with Escherichia coli (64%) being the most frequently detected species. Humans were the most affected (20.4%), followed by animals (12.8%) and the environment (9.3%). Among the 153 identified bacterial clones, ST10, ST410, ST58, ST155, ST4684, ST2178, and ST37, found majorly in E. coli, occurred across multiple sources, suggesting cross-sectoral transmission. The blaCTX-M gene, prevalent with several fluoroquinolone and aminoglycoside resistance genes, was often on conjugative IncF plasmids (50.0%), suggesting high horizontal transmission potential. The emerging ESBL gene, GES (1.2%) was also detected in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The findings reinforce the need for robust antimicrobial resistance monitoring and intervention strategies in West Africa. A regional One Health-based approach is necessary to curtail the spread of resistant bacterial clones and safeguard the efficacy of available treatment options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) are enzymes primarily produced by Enterobacteriaceae, conferring resistance to a wide range of broad spectrum of beta-lactam antibiotics, including penicillins and cephalosporins1. This has intensified concerns about antimicrobial resistance among human and animal populations worldwide2. The growing prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria is now a major public health challenge, making common treatments less effective and facilitating spread beyond healthcare facilities into community settings, with implications for both human and animal health.

ESBLs are primarily plasmid-mediated enzymes that hydrolyse the beta-lactam ring of penicillins and cephalosporins1. Among the plethora of identified ESBL types, blaCTX-M, blaSHV, and blaTEM are the most prevalent. Initially, TEM (Temoniera) and SHV (Sulfhydryl-variable) were predominantly found in hospital-acquired infections, especially in resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. However, CTX-M (Cefotaximase) enzymes have recently become the most widespread globally, appearing in both hospital and community settings, with Escherichia coli now the most commonly associated bacterium3.

The most commonly identified ESBL-producing bacteria are Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae4. Although these organisms are naturally part of the human gut flora, they can cause severe infections when they invade other parts of the body, such as the urinary tract, bloodstream, and lungs1,5. A study focused on the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries reported that the prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria, particularly among Enterobacterales, in clinical samples ranged from 21.6% to 29.3%6. The rates were notably higher in intensive care unit (ICU) patients, with prevalence ranging from 17.3% to 31.3%. Similarly, urinary tract infections had prevalence rates of 25.2%–31.7%6. This clearly demonstrates the important struggle caused by ESBL-producing pathogens in healthcare settings.

In addition to resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, ESBL-producing bacteria frequently exhibit resistance to other classes of antibiotics, including aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones7. This co-resistance complicates treatment options and poses a significant challenge in clinical settings, especially for last-resort carbapenems8.

The prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria varies significantly across regions. Approximately 16.5% of the global population is affected by these resistant bacteria, with particularly alarming rates observed in many developing countries9. For instance, studies have shown that the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli can exceed 50% in certain populations10,11,12. Countries such as India, China, and parts of Africa, including Ethiopia, have reported especially high rates of these resistant strains, indicating a rise in public health crises13,14,15.

Clonal dissemination is a well-known factor in the spread of ESBL-producing bacteria, with specific clones identified across various reservoirs, indicating potential transmission pathways between humans, animals, and the environment16. Despite the global focus on ESBL-producing bacteria, a significant gap remains in our understanding of their clonal interactions, especially in West Africa. Comprehensive studies on the spread of these clones between humans, animals, and the environment in this region are lacking, leaving critical questions about their public health implications unanswered. This knowledge gap raises concerns about the role of animals and the environment as reservoirs and vectors of these resistant strains, which could have serious implications for human health.

This systematic review investigated the distribution and interconnections of ESBL-producing bacterial clones among humans, animals, and the environment in West Africa. We focused on the shared characteristics and possible transmission pathways of these clones in order to lay emphasis on the urgent need for additional research to address this pressing public health challenge.

Methods

Study design and systematic review protocol

This study was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with registration ID: CRD42024608157 and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines17.

Search strategy

We searched several databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, to retrieve relevant articles, applying no restrictions on publication year. The search terms included keywords such as “ESBL, Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamase,” “One Health,” “Human,” “Animal,” “Environment,” and specific countries in West Africa (Supplementary data 1; Table 1). The last database search was conducted on October 28, 2024.

Study selection

The studies identified from individual databases were first exported and compiled in Zotero (Version 6.0.30), where they were merged into a single RIS file. This file was then imported into Rayyan, an online platform designed for systematic review screening, where duplicate studies were manually identified and resolved. Titles and abstracts were screened to determine their relevance based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Three reviewers independently analyzed all the studies from the search terms’ title, abstract, and selected full texts. A fourth reviewer addressed any inconsistencies or disagreements.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

-

1.

Reported both phenotypic and genotypic identification of ESBL-producing bacteria from human, animal, or environmental sources.

-

2.

Conducted antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacterial isolates.

-

3.

Were based on research conducted in West Africa.

Studies were excluded if they were:

1. Abstracts, review articles, letters to editors, case reports, research notes, systematic reviews.

2. Laboratory-based studies focusing only on resistance gene transfer.

3. Studies conducted during outbreaks.

4. Studies focusing solely on the phenotypic or genotypic identification of ESBL-producing bacteria.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted and summarized from the final selected studies: author name and year of publication,study period, study design, country, population, sample size, settings, sample types, ESBL diagnostic method, ESBL bacterial species, ESBL positive isolates, phenotypic resistance to Ciprofloxacin (CIP), Nalidixic acid (NAL), Chloramphenicol (CHL), Imipenem/Meropenem (IPM/MEM), Tobramycin (TOB), Gentamicin (GEN), Tetracycline/Doxycycline (TET/DOX), Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SXT), ESBL and other co-resistance genotypes, ESBL clones (sequence types), and associated ESBL plasmid types. The extracted data were compiled in Microsoft Excel for further analysis.

Quality assessment

A critical appraisal tool developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) was used to assess the risk of bias among the included studies18. There are nine questions in this JBI instrument. Each answer was scored 0 or 1 based on whether the answer was “yes” or “no”. NA was used to indicate that the question was not relevant. Studies with scores of 7–8 indicated a low risk of bias, those with scores of 5–6 indicated a moderate risk of bias, and those with scores less than 5 indicated a high risk of bias (Supplementary data 1; Table 2).

Data analysis

Data were organized in narratives, figures, and tables. The meta-analysis of the prevalence of ESBL-positive isolates in humans, animals, and the environment was conducted using RStudio software version 4.4.2. This analysis included data from 38 studies included in the systematic review. The meta-package was used to estimate pooled prevalence using the DerSimonian-Laird method. To ensure consistency in variances across studies and facilitate pooled prevalence computation, the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation was applied. Furthermore, 95% confidence intervals for individual studies were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method.

The pooled prevalence of ESBL-positive isolates was measured, and subgroup analyses were performed according to country, setting, and population. Studies reporting on ESBL-positive E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates were analyzed separately to determine their prevalence. Subgroup analyses were also conducted on the basis of the settings and sample types. This approach was adopted because E. coli and K. pneumoniae emerged as the most prevalent ESBL-positive bacteria across human, animal and environmental sources.

The random-effects model was used to generate forest plots showing the study-specific effect sizes with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for the pooled prevalence. The I2 statistic was used to measure the heterogeneity among the studies. A value close to 0% indicates no heterogeneity, whereas values close to 25%, 50%, and 75% correspond to low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. The p-values correspond to the heterogeneities between studies from the chi-squared test of the null hypothesis that there is no heterogeneity. The distribution of clones circulating across human, animal, and environmental sources was analysed. Publication bias was measured using funnel plots to test for symmetry and was further complemented using Egger’s regression test.

We also conducted sensitivity and meta-regression analyses to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. Statistical significance was determined using a p-value threshold of < 0.05.

Results

Search and screening results

A total of 485 studies were retrieved after the initial search across three databases, including 183 from PubMed, 243 from Scopus, and 59 from Web of Science. After 335 duplicate studies were detected and resolved, titles and abstracts of 293 articles were screened based on the eligibility criteria. A total of 212 studies which were initially considered eligible and were subjected to full-text evaluation. After full-text examination, 38 articles were eligible for inclusion [humans (n = 21), animals (n = 7), environment (n = 2), Interdisciplinary studies (n = 8)] (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

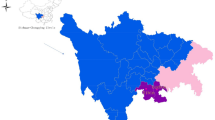

All included studies were published between 2011 and 2024, with most of them (63.2%) having been conducted between 2015 and 2019. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were from only 9 out of 16 countries in West Africa. Nigeria had the highest number of individual studies (n = 17), followed by Ghana (n = 13), Senegal (n = 3), and Burkina Faso (n = 2). The remaining countries, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Niger, Gambia, and Benin, had one study each (Fig. 2) (Supplementary data 1; Table 3).

The number of confirmed ESBL-positive isolates across the studies ranged from 1 to 1937 and comprised 25 different bacterial isolates across the nine West African countries, encompassing various populations, settings, and sample types (Fig. 3) (Supplementary data 2; Table 1).

A majority of the studies were conducted on humans (76.3%, n = 29), followed by animals (34.3%, n = 13) and the environment (15.6%, n = 6) (Supplementary data 1; Table 3). Most studies isolated ESBL-positive bacteria from hospital-based settings (68.2%, n = 24), followed by communities (15.8%, n = 6), farms (10.5%, n = 4), and markets (2.6%, n = 1). Some isolated the bacteria from a combination of sources, such as markets and farms (7.9%, n = 3) and communities and hospitals (5.3%, n = 2). Most studies isolated the bacteria from two major sample types: clinical specimens (39.5%, n = 15) and faeces (31.6%, n = 12) (Supplementary data 1; Table 3).

Among the 25 ESBL-positive isolates, 18 were identified as Enterobacteriaceae and 7 were classified as non-Enterobacteriaceae (Supplementary data 2; Table 1).

The most commonly used ESBL diagnostic methods were EUCAST disk diffusion (18 studies), Double-Disk Synergy Test (DDST) (18 studies), Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) (30 studies), and Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) (34 studies) (Supplementary data 1; Table 3).

ESBL-producing bacterial species across human, animal, and environmental sources in West Africa

E. coli and K. pneumoniae accounted for 64% and 31% of the ESBL-positive isolates, respectively. Other Enterobacteriaceae species collectively comprised 4% of the isolates, whereas non-Enterobacteriaceae constituted 1% of the total isolates (Supplementary data 2; Table 1A).

ESBL genes and clones

A total of 171 ESBL genes were identified, with blaCTX-M being the most predominant gene (70.8%) across humans, animals, and the environment. The most frequent variant, blaCTX-M-15 (31.6%), was detected in all three sources, with greater occurrence in humans (21.1%) than in animals (7.6%) or the environment (2.9%) (Fig. 4) (Supplementary data 2; Table 2–10).

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed on 7 of 25 isolates, identifying 153 unique sequence types (STs) (Supplementary data 2; Table 14). Among these, Nigeria accounted for 133 clones from 5 isolates, with ST10, ST131, and ST410 being the most frequently observed. Ghana contributed 139 clones from 3 isolates, predominantly featuring ST131 and ST617, whereas 64 clones were identified from 4 isolates in other countries (Supplementary data 2; Table 11–13).

In terms of species-specific observations, E. coli exhibited considerable differences in sequence types among the different sources. In humans, ST131, ST10, ST410, and ST617 were prominent, whereas animals predominantly exhibited ST48, ST10, and ST38. Environmental samples were marked by the prevalence of ST10, ST58, and ST155. For K. pneumoniae, the predominant human STs were ST17, ST36, ST530, ST15, and ST14. In animals, ST307 was observed, and ST152 was most frequently observed in the environment. Non-Enterobacteriaceae displayed notable source-specific trends, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST1469 and ST235 linked to human samples and Acinetobacter baumannii ST109, ST1, ST78, ST132, and ST1136 linked to environmental samples (Supplementary data 2; Table 11–13).

Clonal distribution analysis showed that 71 clones were unique to humans, 27 to animals, and 14 to the environment. The number of shared clones between humans and animals was 25, between humans and the environment was 4, and between animals and the environment was 5. Notably, seven clones including ST10, ST410, ST58, ST155, ST4684, ST2178, and ST37 were detected predominantly in E.coli across all three sources. ST37 was also observed in K. pneumoniae (Fig. 5) (Supplementary data 2; Tables 11–14; Fig. 1).

Potential transmission routes of ESBL clones

Data from 7 of 38 studies (18.4%) were analysed for possible transmission routes of ESBL clones across human, animal and environmental sources. These studies used a combination of sources to detect the prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria in hospitals, markets, and farms (Supplementary data 1; Table 3). These studies included Humans-Animals, Humans-Environment, and Humans-Animals-Environment studies (Table 1). Although the studies did not clearly state the transmission routes, they acknowledged that because of the common ESBL clones detected, the transmission routes were possible.

Antimicrobial resistance patterns

An analysis of 24 studies covering 1215/1937 ESBL-producing bacterial isolates revealed significant resistance patterns against non-beta-lactam antibiotics (Supplementary data 1; Table 4) (Supplementary data 2; Table 15–15A). The results show that bacteria from humans are much more resistant than those from animals and the environment. Phenotypically, the bacteria were particularly resistant to commonly prescribed antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin (71%), gentamicin (58%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (53%). Resistance to tobramycin (39%) and tetracycline/doxycycline (28%) was moderate, whereas nalidixic acid (17%), imipenem/meropenem (16.7%), and chloramphenicol (14.1%) showed lower resistance (Fig. 6).

Co-resistance genes

The ESBL-producing bacterial isolates also exhibited the genotypic presence of co-resistance genes. Aminoglycoside and fluoroquinolone/quinolone resistance genes were the most frequently reported, each appearing in 15 studies, with aac(6′)-Ib-cr identified as the predominant resistance gene. Folate pathway antagonists’ resistance genes were reported in 12 studies, where dfrA14 was the most common resistance gene. This was followed by sulfonamides (11 studies), where sul2 was the most common gene, and tetracyclines (10 studies), with tet(A) as the predominant resistance gene. Phenicols were reported in 9 studies, with catA1 being the most prevalent gene. Finally, carbapenem resistance genes were documented in 8 studies, with blaNDM, blaOXA-48, and blaOXA-181 identified as the predominant resistance genes. Additionally, five studies reported mutations within the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) of gyrA, parC, parE, and parcE (Table 2). (Other reported co-resistance genes are present in the supplementary data 2; Table 16).

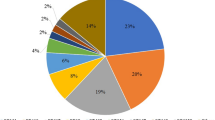

Mobile genetic elements

A total of 22 studies performed mobilome analyses to identify the plasmid types carrying ESBL and other co-resistance genes. IncF plasmids emerged as the most prevalent, found across human, animal, and environmental sources, with an overall prevalence of 50.0%. Col plasmids were the second most common, accounting for 16.4%. Other plasmid types, including IncH, IncQ, and IncI, were detected at lower frequencies, with prevalence rates ranging from ~ 4.0% to ~ 7.0%. (Fig. 7) (Supplementary data 2; Table 17–17A).

Meta-analysis

Prevalence of ESBL

The overall pooled prevalence of ESBL in West Africa was 16.8% (95% CI [12.1; 22.1]. Nigeria and Ghana reported the highest prevalence at 18.3% and 17.3%, respectively, while Burkina Faso and Senegal had low prevalences at 6.0% and 1.2%, respectively (Fig. 8).

Humans had the highest prevalence at 20.4%, followed by animals at 12.8% and the environment at 9.3% (Fig. 9). Among settings, market-based environments recorded the highest prevalence at 23.6%, followed by hospitals at 21.8% and community-based settings at 7.5% (Supplementary data 1; Fig. 1).

Prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae

The study explored ESBL-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae in 34 of 38 and 20 of 38 studies, respectively, across humans, animals, and the environment (Supplementary data 2; Tables 18-23). The prevalence of ESBL E. coli was 15.9% (95% CI: [9.8; 23.1], 26 studies) in humans, 15.0% (95% CI: [6.5; 26.0], 11 studies) in animals, and 6.1% (95% CI: [1.8; 12.4], 5 studies) in the environment (Table 3). The prevalence of ESBL K. pneumoniae was 8.2% (95% CI: [3.9; 13.8], 16 studies) in humans, 2.0% (95% CI: [0.4; 4.3], 4 studies) in animals, and 6.6% (95% CI: [4.4; 9.2], 2 studies) in the environment (Table 4).

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis of pooled prevalence estimates for ESBL-positive E. coli and K. pneumoniae across humans, animals, and the environment revealed distinct patterns based on settings and sample types.

For E. coli, human studies showed the highest prevalence in hospital-based settings (17.6%) and faecal samples (23.2%). Among animals, faecal samples have the highest prevalence (27.0%), and farm-based settings (21.7%) were particularly affected. In environmental studies, the abattoir environment has the highest rate (22.4%), whereas hospital-based environments have much lower rates (1.7%) (Table 3).

Clinical specimens: urine, ear swab, sputum, blood culture, eye swab, wound swab, urethral swab, endocervical swab, stool, high vaginal swab, nasal swab, gastric lavage, pus, tracheal aspirates, semen, axilla, groin, perianal region, cerebrospinal fluid, lower respiratory tracts, urinary tract infections (UTIs), ascitic fluid.

Patient environment: swabs of high- and low-touch areas, beds, taps, and drip stand.

NICU environment: swabs of incubator doors, cots, nurse trolley handle, weighing scales, tables, and desks.

For K. pneumoniae, human studies revealed a dominance of hospital-based settings (10.4%) and clinical specimens (9.5%) prevalence, with wound swabs reporting the highest prevalence in individual samples (57.1%). In animals (4 studies, 2.0%), community-based settings (2.5%), and rectal swabs (10.3%) showed higher prevalence rates. Environmental studies for K. pneumoniae (6.6% prevalence) indicated that patient environments (7.4%) had a slightly higher prevalence than NICU environments (5.8%) (Table 4).

Heterogeneity was significant in human studies on both isolates (I² ~99%), indicating variability across settings and sample types, whereas environmental studies on K. pneumoniae showed minimal variability (I² = 0%). This subgroup analysis indicated significant differences in the prevalence of ESBL E. coli and K. pneumoniae depending on the host/source, settings, and sample type.

Heterogeneity and publication bias

The funnel plot illustrates a publication bias, which was confirmed by Egger’s regression test (p = < 0.0001) (Supplementary data 1; Fig. 2). Estimated prevalences were significantly heterogeneous across countries, populations, and settings (H > 1 and I2 ≥ 75%). The overall prevalence also showed significant heterogeneity (H = 8.98 [8.51; 9.49] and I = 98.8% [98.6%; 98.9%]).

Sensitivity analysis and meta-regression

The impact of each study on the pooled prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria was assessed using a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. The sensitivity analysis revealed that excluding individual studies had a minimal impact on the pooled prevalence of 16.8%, with most exclusions resulting in prevalence values ranging from 16.0 to 17.4%. Only one study reported a slightly lower prevalence of 15.8%. These findings indicate that the pooled prevalence was stable and not overly influenced by any single study, demonstrating the robustness of the meta-analysis results (Supplementary data 1; Table 5).

A random effects meta-regression analysis was used to assess the effect of the three study characteristics on the observed wide variations in effect sizes in this study. Country, population, and settings were used as covariates. Gambia had a minimally significant negative association with heterogeneity. The remaining covariates did not significantly affect heterogeneity (Table 5).

Discussion

ESBL prevalence in West Africa is a growing concern, emphasising the need for a better understanding of its transmission across different populations and environments. While global and regional studies have documented the prevalence of ESBL, there is still a lack of detailed analyses of the movements of ESBL-producing clones between humans, animals, and the environment. This systematic review and meta-analysis filled this gap by synthesising findings from West African studies to provide essential evidence for addressing these clones and their genetic elements.

The overall prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria in West Africa was 16.8%, which is notably lower than that reported in other countries, particularly in subregions of Africa where extreme pooled prevalences have been observed. For instance, countries such as Egypt, Ethiopia, and China have reported ESBL-producing bacterial prevalence rates exceeding 50%12,15,19. Additionally, other subregions in Africa, specifically East, Central, and Southern Africa, have recorded pooled prevalence rates greater than 30%20.

The predominant species observed in this review associated with ESBL were from the Enterobacteriaceae family, particularly E. coli and K. pneumoniae. These species have emerged as some of the most problematic Enterobacteriaceae species globally, associated with various infections that result in prolonged hospital stays, costly treatments, and increased mortality rates. This aligns with the findings of an epidemiological study by Quan et al., who noted a global increase in ESBL prevalence in E. coli and K. pneumoniae11. Non-Enterobacteriaceae species such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii were also identified as contributors to ESBL prevalence, albeit at a very low prevalence (1%). This result is in contrast with the findings of Rameshkumar et al., who reported that P. aeruginosa accounted for 38% of ESBL-related cases, surpassing that of E. coli at 16.6%21. An epidemiological study in Egypt confirmed the ESBL-producing nature of A. baumannii in clinical settings22.

The acquisition of ESBL genes by non-Enterobacteriaceae may be attributed to their conjugative abilities, with horizontal gene transfer playing a crucial role in the dissemination of these genes. Notably, A. baumannii was observed in one of the environmental sources, suggesting a potential pathway for acquiring ESBL genes.

The emergence of ESBL-producing strains has created a crisis that renders traditional treatments ineffective against common infections. Initially, common beta-lactam antibiotics such as amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ampicillin, cefotaxime, cefepime, and ceftazidime were employed; however, they have been proven ineffective due to the ability of ESBL enzymes to hydrolyse the beta-lactam rings of penicillins and cephalosporins.

Natural resistance is a plausible explanation for this phenomenon23. This refers to the intrinsic ability of certain bacteria to resist specific antibiotics, allowing them to proliferate even at high concentrations that the human body can tolerate. Acquired resistance also plays a role, particularly in non-Enterobacteriaceae that circulate among humans, animals, and the environment. Resistance can arise through chromosomal mutations, often due to antibiotic overuse or acquired resistant plasmids or insertion sequences23.

Beta-lactam antibiotics have been used to confirm the presence of ESBL-producing bacteria as part of the identification of alternative treatment options. Our findings indicate that commonly used antibiotics for this purpose include those previously mentioned24. However, alternative treatment options employed against these bacteria include ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, chloramphenicol, imipenem/meropenem, tobramycin, gentamicin, tetracycline/doxycycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Unfortunately, due to co-resistance, these bacteria can acquire additional genes through horizontal gene transfer, enabling them to resist and neutralise these antibacterial agents.

In this study, the widespread presence of co-resistance genes in ESBL-producing bacteria across various sources was confirmed, with the findings being consistent with that of previous studies.For instance, Tacao et al. reported high levels of co-resistance to non-beta-lactam antibiotics in aquatic environments25, while Athanasakopoulou et al. observed similar patterns in animal isolates26. Moreover, Yang et al. identified co-resistance genes in clinical samples27. A common feature found across these studies was the detection of fluoroquinolone/quinolone resistance genes, indicating their high prevalence in ESBL-producing bacteria. Similarly, inthis analysis, fluoroquinolone/quinolone and aminoglycoside resistance genes were the most frequently encountered, with “aac(6′)-Ib-cr” emerging as a dominant genetic determinant. Notably, five studies reported mutations in genes encoding the quinolone resistance determining regions (QRDR) gyrA, parC, and parE, which are key contributors to fluoroquinolone/quinolone resistance28.

Furthermore, the genes associated with ESBL-producing bacteria were predominantly blaCTX-M gene (70.8%), with its most troublesome variant being blaCTX-M-15 (31.6%). This finding aligns with a study conducted in China on the epidemiological characteristics of antimicrobial resistance in ESBL-producing bacteria, in which blaCTX-M was identified as the most prevalent ESBL gene15. Counter to our findings, their study identified another variant, blaCTX-M-14, as the most common but acknowledged the potential rise of blaCTX-M-15. Other genes, such as blaSHV, blaTEM, blaOXA, and blaVEB, although present at lower proportions in this study, have been recognised in other studies as highly prevalent under certain conditions29,30. For instance, a systematic review by Ghaderi et al. identified high prevalence rates of blaSHV (37%) and blaTEM (51%) in clinical isolates in Iran31.

Interestingly, a study in the early 2000’s reported a novel ESBL-associated gene called Guiana-Extended-Spectrum (GES), which was isolated from nine countries, including French Guiana, Brazil, Portugal, Argentina, South Africa, Japan, Korea, Greece, and France. This gene consisted of nine variants identified at that time: GES-1 through GES-9. These genes were found in common enterobacteria, such as E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Enterobacter cloacae, as well as non-enterobacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which were associated with GES-1, GES-2, GES-8, and GES-932. Our findings indicate that this emerging family of ESBLs has been isolated in Senegal and Nigeria, with GES-1 and GES-9 being the major variants discovered in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Although the emergence rate in West Africa is low at 1.2%, it raises concerns about the future prominence of ESBL-associated genes, potentially surpassing that of blaCTX-M-15.

Studies have shown that ESBL-producing bacteria are highly susceptible to imipenem/meropenem; thus, these antibiotics are recommended as a last line of defence against such infections33,34. Despite our findings indicating a relatively low rate of resistance developing across West Africa (16.7%), concerns remain regarding the growing threat posed by these bacteria’s ability to neutralise these antibiotics. A systematic review by Khademi et al. reported a pooled prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria resistant to imipenem and meropenem of 16.6% and 16.2%, respectively, indicating that resistance to these drugs is gradually developing24.

Market-based settings were observed to have a higher prevalence of ESBL (23.6%) compared with hospital-based settings (21.8%). Hospitals are reservoirs for various resistant bacterial strains because of antibiotic overuse; however, market-based environments have emerged as significant reservoirs for ESBL bacteria across West Africa because of the poor hygiene conditions prevalent in many markets. In a study conducted in Mumbai which assessed the prevalence of ESBL E. coli in fresh seafood from retail markets and found it to be as high as 71.58%, researchers indicated a clear link between poor hygiene practices and elevated prevalence rates35. Another contributing factor could be improper antimicrobial agent disposal practices leading to resistance acquisition across various interfaces within the market.

This review shows significant public health concerns regarding the prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria in humans (20.4%), animals (12.8%), and environmental sources (9.3%). Humans are primary reservoirs, especially in healthcare settings, while farm animals such as poultry and cattle, also serve as carriers for resistant strains due to antibiotic misuse in agriculture. Environmental reservoirs, particularly healthcare-associated water systems, and inadequately disposed waste further facilitate bacterial spread. One study focused on the interconnectedness between strains found among patients and within neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) environments and indicated that neonates are at heightened risk due to their vulnerability during early life stages36; this is likely exacerbated by poor sanitation practices and excessive antibiotic use within healthcare facilities. Another study emphasised market/farm-based interactions involving humans, animals, and environmental factors where faecal-oral transmission routes are probable pathways for spreading these bacteria37.

Current findings confirm the ongoing circulation patterns for ESBL-associated clones across human, animal, and environmental sources within West Africa; specifically identifying ST131, ST410, ST10, and ST617 as predominant strains in E. coli isolated from humans and animals, consistent with findings from multiple studies confirming their presence across various reservoirs38,39. E. coli clones ST10 and ST410 were also observed in the environmental samples. These clones can be transferred from one source to another enabling their presence across the three interfaces.

At the molecular level, the spread of these ESBL clones is plausibly driven by mobile genetic elements (MGEs). These elements include integrons, transposons, and insertion sequences, which facilitate the transfer of genetic material between bacteria through mechanisms such as horizontal gene transfer, including conjugation, transformation, and transduction40. MGEs are often carried on extrachromosomal DNA, such as plasmids, which harbor foreign genes that can be integrated into the genomes of other bacteria in the environment. These acquired genes frequently encode traits that enhance bacterial survival, most notably antibiotic resistance.

Evidently, this review reported on the presence of notable plasmids harbouring ESBL genes as well as co-resistance genes in ESBL-producing bacteria. The most prevalent plasmids discovered across all sources were IncF and Col conjugative plasmids, with IncF predominating across all sources. Tacao et al. confirms the successful mobilization of ESBL-producers containing ESBL genotypes as well as other co-resistance genes by the IncF plasmid types25. These findings were also confirmed by other studies indicating the presence of these conjugative plasmids in ESBL-producing bacteria29,41.

At a broader level, the dissemination of ESBL-producing clones can be significantly influenced by cross-border livestock trade. This form of trade, while economically beneficial by ensuring a steady supply of livestock to meet demand, also facilitates the translocation of antimicrobial-resistant organisms. Countries with a higher prevalence of ESBL-producing strains can inadvertently introduce these clones into regions with lower prevalence through the importation of colonized or infected animals. A study conducted in Gabon documented cross-border trade involving poultry products imported from industrialized countries, rather than live animals. The study revealed a 23% prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in these imported poultry products42. This suggests that, in addition to cross-border livestock trade serving as a potential transmission route, animal products themselves can also harbor ESBL-producing bacteria.

Within livestock systems, particularly in intensive farming operations where antibiotics are frequently used for growth promotion and disease prevention43, ESBL-producing bacteria can thrive and spread rapidly. The interconnectedness of humans, animals, and the environment further amplifies this risk. Humans can acquire resistant bacteria through direct contact with animals, the handling or consumption of contaminated animal products, or through environmental exposure43.

Animal faeces, often rich in resistant bacteria, can contaminate soil and water systems when used as manure or through uncontrolled runoff44,45. Contaminated water bodies not only affect aquatic life but also pose risks to public health, especially when such water is used for irrigation or as a source of drinking water. Agricultural products irrigated or washed with these waters can act as secondary vehicles for human exposure.

Throughout West Africa, widely circulating clones such as ST10, ST410, ST155, ST58, ST4684, ST2178, and ST37 identified majorly in E. coli, indicate the pressing need for multisectoral, genomic-based strategic interventions utilising One Health approaches. This is particularly important given that approximately 16.7% of the identified ESBL isolates demonstrated resistance to imipenem/meropenem. This finding starkly contrasts with earlier reports that indicated full susceptibility among all isolates, as noted in a previous systematic review conducted in Tanzania by Seni et al.33. It is unfortunate yet necessary to acknowledge current realities regarding rising resistance trends among these pathogens; however, rates remain comparatively lower than those observed for other antibiotic classes, suggesting potential avenues still exist for implementing strategic interventions aimed at curbing further proliferation among existing populations harbouring resistant strains.

We acknowledge some limitations in this review. The final analysis included only a limited number of animal and environmental studies, primarily because of the scarcity of relevant articles. As a result, our examination of the transmission dynamics of circulating genotypes was limited to human-associated studies. Another limitation of this review is that, due to the inclusion criterion requiring both phenotypic and genotypic detection of ESBLs, only 9 out of 16 West African countries were represented in the final analysis. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader region. Furthermore, the present antimicrobial resistance patterns do not encompass the full range of studies. Some studies have focused solely on testing the total number of isolates without specifically addressing ESBL-positive isolates. Moreover, some studies employed graphical representations to convey their results, lacking numerical indicators that would clarify the presence of resistant ESBL isolates.

Conclusion

This review confirms that West Africa is experiencing a growing antimicrobial resistance crisis, with ESBL-producing bacteria showing a prevalence of 16.8% across human, animal, and environmental sources. Genetic analysis indicates a concerning convergence of resistance traits, with ESBLs, particularly the blaCTX-M-15 gene, frequently co-occurring with fluoroquinolone/quinolone and aminoglycoside resistance genes. These resistance determinants are frequently disseminated through mobile IncF plasmids and widespread ESBL clonal lineages such as E. coli ST10, ST410, ST155, ST58, ST4684, ST2178, and ST37 across human, animal and environmental sources.

Addressing this issue requires a One Health approach, beginning with the establishment of regional genomic surveillance networks to detect resistance hotspots and track transmission routes across sectors and borders. Integrating ESBL monitoring into national health systems through standardized protocols for hospitals, farms, and food supply chains could help identify hidden reservoirs and guide targeted interventions. Central to this effort is antimicrobial stewardship, particularly in the farming sector, where stricter enforcement of antibiotic regulations and investment in alternatives like vaccines or probiotics could reduce selective pressure.

At the same time, future research should focus on uncovering the transmission pathways of ESBL-producing bacteria between humans, livestock, and the environment, while economic studies are needed to evaluate the often-overlooked costs of these infections on healthcare systems and the livestock sector, particularly in West Africa.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials 1, 2, and 3. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- bla:

-

Beta-lactamase

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CMY:

-

Cephamycinase

- Col:

-

Colicinogenic

- CTX-M:

-

Cefotaximase

- DDST:

-

Double-disk synergy test

- ESBL:

-

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase

- EUCAST:

-

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- GCC:

-

Gulf Cooperation Council

- GES:

-

Guiana extended-spectrum

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- IncF/H/I/K/N/Q/R/X/Y:

-

Incompatibility group F/H/I/K/N/Q/R/X/Y

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- MLST:

-

Multilocus sequence typing

- NICU:

-

Neonatal intensive care unit

- OXA:

-

Oxacillinase

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- QRDR:

-

Quinolone resistance determining region

- RIS:

-

Research information systems

- SHV:

-

Sulfhydryl-variable

- ST:

-

Sequence type

- TEM:

-

Temoneira

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

- VEB:

-

Vietnamese extended-spectrum beta-lactamase

- WGS:

-

Whole genome sequencing

References

El Aila, N. A., Laham, A., Ayesh, B. M. & N. A. & Prevalence of extended spectrum beta lactamase and molecular detection of blatem, BlaSHV and blaCTX-M genotypes among gram negative bacilli isolates from pediatric patient population in Gaza strip. BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 99 (2023).

Ramatla, T. et al. One health perspective on prevalence of co-existing extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 22, 88 (2023).

Negeri, A. A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiling and molecular epidemiological analysis of extended spectrum β-Lactamases produced by extraintestinal invasive Escherichia coli isolates from ethiopia: the presence of international High-Risk clones ST131 and ST410 revealed. Front. Microbiol. 12, (2021).

Kuralayanapalya, S. P. et al. Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing bacteria from animal origin: A systematic review and meta-analysis report from India. PLOS ONE. 14, e0221771 (2019).

Rock, C. & Donnenberg, M. S. Human pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae. In Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.00136-7 (Elsevier, 2014).

Hadi, H. A. et al. Prevalence and genetic characterization of clinically relevant extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing enterobacterales in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Front. Antibiot. 2, (2023).

Yousefipour, M. et al. Bacteria producing extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in hospitalized patients: prevalence, antimicrobial resistance pattern and its main determinants. Iran. J. Pathol. 14, 61–67 (2019).

Tan, K. et al. Prevalence of the carbapenem-heteroresistant phenotype among ESBL-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 1506–1512 (2020).

Bezabih, Y. M. et al. The global prevalence and trend of human intestinal carriage of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in the community. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 76, 22–29 (2021).

Coque, T. M., Baquero, F. & Cantón, R. Increasing prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Eurosurveillance 13, 19044 (2008).

Quan, J. et al. High prevalence of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in community-onset bloodstream infections in China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 273–280 (2017).

Teklu, D. S. et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production and multi-drug resistance among Enterobacteriaceae isolated in addis ababa, Ethiopia. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 8, 39 (2019).

Andrews, B., Joshi, S., Swaminathan, R., Sonawane, J. & Shetty, K. Prevalence of extended spectrum Β-Lactamase (ESBL) producing Bacteria among the clinical samples in and around a tertiary care centre in nerul, navi mumbai, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 7, 3402–3409 (2018).

Beyene, D., Bitew, A., Fantew, S., Mihret, A. & Evans, M. Multidrug-resistant profile and prevalence of extended spectrum β-lactamase and carbapenemase production in fermentative Gram-negative bacilli recovered from patients and specimens referred to National reference laboratory, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLOS ONE. 14, e0222911 (2019).

Xiao, Y. H. et al. Epidemiology and characteristics of antimicrobial resistance in China. Drug Resist. Updat. 14, 236–250 (2011).

Schaufler, K. et al. Clonal spread and interspecies transmission of clinically relevant ESBL-producing Escherichia coli of ST410—another successful pandemic clone? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 92, fiv155 (2016).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 10, 89 (2021).

Moola, Z., Munn, S., Lisy, K., Riitano, D. & Tufanaru, C. Chapter 5: Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-06 (2020).

Azzam, A., Khaled, H., Samer, D. & Nageeb, W. M. Prevalence and molecular characterization of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in egypt: a systematic review and meta-analysis of hospital and community-acquired infections. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 13, 1–14 (2024).

Onduru, O. G., Mkakosya, R. S., Aboud, S. & Rumisha, S. F. Genetic determinants of resistance among ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in community and hospital settings in East, Central, and Southern Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 5153237 (2021).

Rameshkumar, G. et al. Prevalence and antibacterial resistance patterns of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Gram-negative bacteria isolated from ocular infections. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 64, 303 (2016).

El-Baky, R. M. A., Farhan, S. M., Ibrahim, R. A., Mahran, K. M. & Hetta, H. F. Antimicrobial resistance pattern and molecular epidemiology of ESBL and MBL producing Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from hospitals in minia, Egypt. Alex J. Med. 56, 4–13 (2020).

Harris, M., Fasolino, T., Ivankovic, D., Davis, N. J. & Brownlee, N. Genetic factors that contribute to antibiotic resistance through intrinsic and acquired bacterial genes in urinary tract infections. Microorganisms 11, 1407 (2023).

Khademi, F., Vaez, H., Neyestani, Z. & Sahebkar, A. Prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacter species resistant to carbapenems in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Microbiol. 2022, 8367365 (2022).

Tacão, M., Moura, A., Correia, A. & Henriques, I. Co-resistance to different classes of antibiotics among ESBL-producers from aquatic systems. Water Res. 48, 100–107 (2014).

Athanasakopoulou, Z. et al. Antimicrobial resistance genes in ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolates from animals in Greece. Antibiotics 10, 389 (2021).

Yang, H., Chen, H., Yang, Q., Chen, M. & Wang, H. High prevalence of Plasmid-Mediated quinolone resistance genes Qnr and Aac (6 ′)- Ib-cr in clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from nine teaching hospitals in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 847–847 (2009).

Kibwana, U. O. et al. Fluoroquinolone resistance among fecal extended spectrum βeta lactamases positive enterobacterales isolates from children in Dar Es salaam, Tanzania. BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 135 (2023).

Carattoli, A. Resistance plasmid families in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01707-08 (2009).

Legese, M. et al. Molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and AmpC producing Enterobacteriaceae among sepsis patients in ethiopia: A prospective multicenter study. Antibiotics 11, 131 (2022).

Ghaderi, R. S., Yaghoubi, A., Amirfakhrian, R., Hashemy, S. I. & Ghazvini, K. The prevalence of genes encoding ESBL among clinical isolates of Escherichia coli in iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gene Rep. 18, 100562 (2020).

Weldhagen, G. F. GES: an emerging family of extended spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 28, 145–149 (2006).

Seni, J. et al. Preliminary insights into the occurrence of similar clones of extended-spectrum beta‐lactamase‐producing bacteria in humans, animals and the environment in tanzania: A systematic review and meta‐analysis between 2005 and 2016. Zoonoses Public. Health. 65, 1–10 (2018).

Gharavi, M. J. et al. Comprehensive study of antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) prevalence in bacteria isolated from urine samples. Sci. Rep. 11, 578 (2021).

Singh, A. S., Nayak, B. B. & Kumar, S. H. High prevalence of multiple antibiotic-resistant, extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli in fresh seafood sold in retail markets of Mumbai, India. Vet. Sci. 7, 46 (2020).

Labi, A. K. et al. High carriage rates of multidrug-resistant gram- negative bacteria in neonatal intensive care units from Ghana. Open Forum Infect. Dis 7, (2020).

Aworh, M. K. et al. Extended-spectrum ß-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli among humans, chickens and poultry environments in abuja, Nigeria. One Health Outlook. 2, 8 (2020).

Hayer, J. et al. Multiple clonal transmissions of clinically relevant extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli among livestock, dogs, and wildlife in Chile. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 34, 247–252 (2023).

Pietsch, M. et al. Molecular characterisation of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from hospital and ambulatory patients in Germany. Vet. Microbiol. 200, 130–137 (2017).

Partridge, S. R., Kwong, S. M., Firth, N. & Jensen, S. O. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31 https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00088-17 (2018).

Johnson, T. J. et al. Separate F-type plasmids have shaped the evolution of the H30 subclone of Escherichia coli sequence type 131. mSphere 1, e00121-16 (2016).

Schaumburg, F. et al. The risk to import ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae and Staphylococcus aureus through chicken meat trade in Gabon. BMC Microbiol. 14, 286 (2014).

Founou, L. L., Founou, R. C. & Essack, S. Y. Antibiotic resistance in the food chain: A developing country-perspective. Front. Microbiol. 7, (2016).

Venglovsky, J., Sasakova, N. & Placha, I. Pathogens and antibiotic residues in animal manures and hygienic and ecological risks related to subsequent land application. Bioresour Technol. 100, 5386–5391 (2009).

Alegbeleye, O. O. & Sant’Ana, A. S. Manure-borne pathogens as an important source of water contamination: an update on the dynamics of pathogen survival/transport as well as practical risk mitigation strategies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 227, 113524 (2020).

Funding

This review paper was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health through the Research and Capacity Building in Antimicrobial Resistance in West Africa (RECABAW) Training Programme hosted at the Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Ghana Medical School (Award Number: D43TW012487). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.D. and S.N.-A.Y.; methodology, S.N.-A.Y., F.K, and A.A.A.; formal analysis, S.N.-A.Y., F.K, and A.A.A; data curation, S.N.-A.Y., F.K., and A.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N.-A.Y., F.K., and A.A.A.; writing—review and editing of final manuscript, S.N.-A.Y. and E.S.D.; visualization, S.N.-A.Y., F.K, and A.A.A; supervision, E.S.D.; project administration, E.S.D.; funding acquisition, E.S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yartey, S.NA., Kungu, F., Asantewaa, A.A. et al. Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Bacterial Clones in West Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis from a One Health Perspective. Sci Rep 15, 29625 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10695-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10695-7