Abstract

This study investigated the causal relationships between cytokines, chemokines, neutrophil-related factors, sleep traits, and CMR-derived cardiovascular phenotypes using two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis. The primary method employed was inverse variance weighted (IVW) analysis, supplemented with MR-Egger and weighted median analyses. We identified 24 significant associations, excluding the SNP rs2001329 related to sleep duration. Notably, CXCL9 showed a strong association with right ventricular peak atrial filling rate (OR = 587.45), while IL-5 was associated with right ventricular stroke volume (OR = 2.45). IL-7 and IL-18 significantly impacted four CMR-derived phenotypes each. Left ventricular ejection fraction was frequently affected by IL-1β, IL-18, CCL2, CXCL9, and NETs. Sensitivity analyses indicated minimal pleiotropy or heterogeneity except for sleep duration. This research highlights crucial cytokines and chemokines that modulate cardiac function through their relationships with cardiovascular phenotypes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are a leading cause of mortality worldwide, affecting approximately 523 million people1 and accounting for nearly 32% of all global deaths annually2. These conditions, including coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke, present a significant public health challenge due to their complex etiologies and substantial burden on healthcare systems3. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) is essential for assessing detailed cardiac phenotypes, including ventricular volumes, function, and tissue characterization, in CVD. It allows for the precise measurement of cardiac parameters, such as left and right ventricular volumes and ejection rates, facilitating early identification of subclinical abnormalities and improving diagnostic accuracy before clinically evident CVD develops4. However, CVD is not only driven by structural heart changes, but also results from a variety of interconnected processes, including metabolic5, genetic6, and environmental factors7, which contribute to the initiation and progression of cardiovascular pathology. Understanding the causal effects of these factors on CMR-derived phenotypes is crucial for identifying how they directly influence cardiac structure and function, which can enhance early diagnosis and guide personalized treatment strategies for CVD.

Inflammatory factors play a critical role in the pathogenesis of CVD by promoting endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, and adverse myocardial remodeling8. Cytokines and chemokines initiate and propagate inflammatory cascades that result in vascular injury and plaque formation, contributing to the development of atherosclerosis and plaque instability9. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which are released during inflammation, have been implicated in vascular thrombosis10 and further aggravate endothelial damage11. These processes can lead to myocardial fibrosis, edema, and ventricular dysfunction, all of which are detectable using CMR12. Sleep disturbances further exacerbate cardiovascular risk by increasing systemic inflammation and autonomic dysregulation. Poor sleep quality has been associated with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress, which can impair myocardial relaxation and contractility, leading to cardiac remodeling and dysfunction13. Given these interactions, investigating the causal relationships between inflammatory factors and sleep traits with CMR-derived cardiac phenotypes is essential to clarify their specific roles in CVD progression and to inform targeted therapeutic strategies.

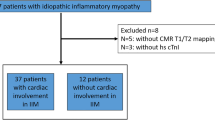

In this study, we aimed to investigate the causal relationships between inflammatory factors, sleep traits, and CMR-derived cardiovascular phenotypes. To achieve this, we employed Mendelian randomization (MR), an analytical method that uses genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to infer causal relationships between exposures and outcomes, thereby minimizing confounding factors and reverse causation14. We utilized large-scale GWAS datasets covering 27 exposures (13 cytokines, 3 chemokines, 4 neutrophil-related factors, 5 sleep traits) from 29 datasets and 17 CMR-derived cardiovascular phenotypes from 19 datasets, with sample sizes ranging from thousands to over 460,000 individuals, providing strong statistical power for detecting associations. By using these extensive data sources, we explored whether genetic predispositions related to inflammatory and sleep-related factors directly impact CMR-derived cardiac phenotypes. Establishing these causal relationships will provide critical insights into how systemic inflammation and sleep disruptions contribute to CVD development by impacting cardiac structure and function, potentially identifying new therapeutic targets and strategies for improving cardiovascular health.

Methods

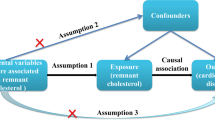

Study design

A two-sample Mendelian Randomization (MR) analysis was employed to investigate the causal relationships between cytokines, chemokines, neutrophil-related factors, sleep characteristics, and CMR-derived phenotypes. IVs were selected based on their strong association with the exposure, their independence from confounding factors affecting the exposure-outcome relationship, and their exclusive effect on the outcome through the exposure14. The study design followed a robust MR framework, including the selection of SNPs as IVs, MR analysis, and sensitivity assessment (Fig. 1). Summary data were obtained from published studies and public databases. No ethics approval was needed.

Exposure data

The genetic instruments for cytokines, chemokines, and neutrophil-related traits were sourced from the GWAS Catalog. These exposures included circulating levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13, IL-18, TNF-α, TNF-β, CCL2, CXCL9, CXCL10, myeloperoxidase, myeloperoxidase-DNA complexes, NETs, and neutrophil count (Table S1). GWAS data for chronotype were sourced from a published study15. Data for other sleep traits, including sleep duration and nap during the day, were obtained from the UK Biobank database or the GWAS Catalog (Table S2). All exposure GWASs were conducted in European-ancestry populations. For traits with multiple GWAS sources in the GWAS Catalog, we selected the dataset with the largest sample size, and when sample sizes were comparable, we prioritized the most recent study.

Outcome data

The CMR-derived phenotypes used as outcomes included left and right ventricular structure and function measurements. These data were sourced from previously published GWAS conducted in European-ancestry individuals16,17 and summarized in Table S3.

IV selection

SNPs were selected as IVs using a structured approach. First, SNPs with a p-value less than 5 × 10−8 were selected. For traits with less than 4 SNPs meeting this threshold, a relaxed criterion of p < 5 × 10−6 was applied18,19. Next, SNPs with a minimum allele frequency (MAF) greater than 0.01 were selected20. SNPs exhibiting linkage disequilibrium (LD) were excluded based on an R2 threshold of less than 0.001 within a 10,000 kb window to eliminate confounding LD effects21. The strength of each SNP as an IV was assessed by calculating the F-statistic to mitigate the potential bias from weak instruments. The F-statistic was calculated using the formula F = R² × (N-2) / (1-R²). R² represents the proportion of variance in the exposure explained by the SNP22. An SNP was considered robust if its F-statistic exceeded 10. For a complementary sensitivity analysis, IV selection was repeated using a relaxed clumping threshold (R² < 0.1, ± 120 kb window) to assess the robustness of the findings to LD pruning parameters.

MR analysis

The causal association between exposure and outcome was primarily evaluated using the inverse variance weighted (IVW) method by calculating odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs)23. MR-Egger, weighted median estimator, and weighted mode were used as supplementary analysis methods24.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were used to detect heterogeneity and pleiotropy in MR studies. Heterogeneity among IVs was assessed using Cochran’s Q test, with significance considered when p < 0.05. The presence of horizontal pleiotropy was detected using the MR-Egger regression method; a non-zero intercept suggests pleiotropy. Outliers (SNPs with p < 0.05) were identified using the MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier test (MR-PRESSO). By excluding these outliers, the causal associations were recalculated to correct for horizontal pleiotropy. Leave-one-out (LOO) analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of the results. Additionally, to assess the robustness of our findings to instrument selection criteria, we performed a second-round sensitivity analysis using a relaxed LD clumping threshold (R² < 0.1, ± 120 kb window).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using R version 4.0.5 and the “TwoSampleMR” package. Causal estimates were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. P-values were additionally adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg (B–H) method. Data were visualized using forest plots, scatter plots, and funnel plots.

Results

IV selection

This study selected a variety of SNPs for different traits, ranging from 5 SNPs for IL-1β, TNF-α, and TNF-β to 1,001 SNPs for chronotype. The mean F-statistics for these traits ranged from 1.270797 for chronotype to 112.1276 for neutrophil count, with most traits exhibiting mean F-statistics above 20, indicating that the selected instruments are generally strong and reliable. Details of the IVs are shown in Table S4.

Causal effects of chemokines, cytokines, and neutrophil-related factors on CMR-derived cardiac phenotypes

The IVW analysis identified 19 significant associations between cytokines and cardiac phenotypes, 4 for chemokines, and 1 for neutrophil-related factors (Table 1). IL-7 and IL-18 showed the most frequent associations, each linked to 4 different cardiac phenotypes. Notably, CXCL9 was positively associated with both left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and right ventricular peak atrial filling rate (RVPFR), with the latter showing an exceptionally strong association (OR = 587.4485, 95% CI = 1.9601–176057.7565, p = 0.0284, adjusted p = 0.355), suggesting a potential role in cardiac function. In addition, IL-5 exhibited a nominally significant associations with right ventricular function, particularly with right ventricular stroke volume (RVSV; OR = 2.4489, 95% CI = 1.0113–5.9302, p = 0.0472, adjusted p = 0.461). Scatter, forest, and funnel plots further supported the robustness of these associations. LOO analysis suggested that no single SNP disproportionately influenced the observed associations (Fig. S1 and S2). Additionally, NETs showed a minimal positive association with LVEF (OR = 1.0132, 95% CI = 1.002–1.0245, p = 0.0208, adjusted p = 0.302). Although none of the associations survived B–H correction, the findings highlight CXCL9, IL-5, IL-7, and IL-18 as potentially relevant factors in left and right ventricular function.

Causal effects of sleep traits on CMR-derived cardiac phenotypes

For sleep traits, only sleep duration showed a significant association with a reduction in right ventricular end-systolic volume (RVESV; OR = 0.0962, 95% CI = 0.0098–0.9436, p = 0.0444). The complete results of the MR analysis using IVW and supplementary methods are presented in the supplementary materials.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess heterogeneity and pleiotropy in the significant associations identified in IVW analysis, we calculated the Q statistic (IVW) and MR-Egger intercept. Most exposures showed no significant heterogeneity or pleiotropy, indicating robustness in the findings. However, sleep duration showed mild heterogeneity (Q = 86.97, p = 0.0429) in its association with RVESV (Table 2). To detect and correct for outlier effects in the identified causal relationships, we employed the MR-PRESSO method. The results showed that sleep duration maintained significant effects on RVESV after correcting for outliers (global p-value = 0.03) (Table 3). However, further analysis of sleep duration revealed that when the genetic variant rs2001329 was excluded, the heterogeneity in the association with RVESV decreased (Q = 74.838, p = 0.18926 vs. Q = 86.97399, p = 0.042871), suggesting that rs2001329 might contribute to the observed heterogeneity and potentially distorting the association. After its exclusion, the association between sleep duration and RVESV became non-significant (OR = 0.1467, 95% CI = 0.0171–1.2589, p = 0.0801; Table 1), suggesting that rs2001329 may affect the initial association observed between the two traits. In addition, for CXCL10–RVPFR association, the discrepancy between IVW and MR-Egger estimates (Fig. S1C) prompted further scrutiny. However, the MR-Egger intercept was not significant (p > 0.05; Table 2), MR-PRESSO did not detect any significant outliers (Table 3), and LOO analysis confirmed that no single SNP disproportionately influenced the result (Fig. S1D), suggesting minimal bias from pleiotropy or influential variants.

To further assess the robustness of our findings, we performed a second-round sensitivity analysis using relaxed clumping (R² < 0.1, ± 120 kb window) for IV selection. SNP counts ranged from 1 to 5964, and the mean F-statistics ranged from 1.37 (chronotype) to 112.13 (neutrophil count). Exposures with < 3 SNPs (e.g., IL-5, IL-7, CXCL9) were excluded due to limited power. Chronotype and neutrophil count were omitted due to the computational burden associated with their extremely large IV sets (Table S5). Among the IVW-significant associations (bolded in Table S6), sleep duration–RVESV showed both strong heterogeneity (Q = 267.63, p <0.001) and nominal pleiotropy (intercept p = 0.02, adjusted p = 0.18), whereas CXCL10–left ventricular structure showed heterogeneity (Q = 15.58, p = 0.016). MR-PRESSO identified significant horizontal pleiotropy in both the sleep duration–RVESV (global p < 0.0003) and CXCL10–left ventricular structure (global p = 0.0254) associations, each driven by a single outlier (rs10838136 and rs75751338, respectively). However, the distortion tests were non-significant (sleep duration: p = 0.806; CXCL10: p = 0.466), indicating that removal of the outlier did not substantially alter the causal estimates (Table S7). These findings suggest that the observed associations were robust to alternative instrument selection thresholds.

Discussion

This study identified 24 significant associations between cytokines, chemokines, and neutrophil-related factors with CMR-derived cardiac phenotypes. Notably, IL-7 and IL-18 were each linked to 4 distinct cardiac phenotypes, indicating their broad impact on cardiac function. Among chemokines, CXCL9 exhibited significant positive associations with both LVEF and RVPFR, with the latter showing an exceptionally strong association. IL-5 was significantly associated with RVSV, highlighting its role in right ventricular function. Additionally, NETs showed a minimal positive association with LVEF. For sleep traits, sleep duration initially exhibited a significant association with reduced RVESV. However, after excluding the genetic variant rs2001329, this association became non-significant. These findings suggest that utilizing CMR-derived phenotypes provides precise and comprehensive insights into cardiac structure and function, which is crucial for accurately assessing how inflammatory factors influence cardiovascular health.

CXCL9 is a chemokine known for its role in immune activation and T-cell recruitment25 and has been increasingly linked to cardiovascular inflammation and disease progression26. In our study, CXCL9 demonstrated strong positive associations with both RVPFR and LVEF. While these increases might initially suggest improved cardiac function, it is essential to consider the broader context of inflammation’s role in cardiac physiology. Acute inflammatory responses can activate reparative immune pathways, which may account for the observed associations as part of a short-term compensatory mechanism in cardiac function27. However, chronic inflammation is associated with adverse effects such as fibrosis and ventricular remodeling, indicating that sustained CXCL9 activation could lead to long-term detrimental outcomes in cardiac health28. The unusually large effect of CXCL9 on RVPFR may indicate that the right ventricle, which is more susceptible to pressure overload and inflammatory stress29, experiences a heightened response to inflammation. While an increase in RVPFR might reflect an initial adaptive response, prolonged elevation could lead to right ventricular overload, diastolic dysfunction, and eventual heart failure30. Similarly, the positive association with LVEF suggests that CXCL9 could transiently enhance systolic function, but over time, chronic inflammation could impair contractility and promote heart failure through structural remodeling31. Thus, the positive associations between CXCL9 and cardiac function metrics likely reflect a complex interaction, underscoring the dual role of inflammation in cardiac physiology.

In this study, IL-5 demonstrated the second strongest positive association, after CXCL9, with RVSV and RVEF, reflecting a notable increase in RV function. IL-5 is a cytokine primarily involved in immune regulation, particularly through eosinophil activation and B cell differentiation32. IL-5 has been shown to promote cardiac repair post-myocardial infarction by facilitating eosinophil accumulation and macrophage polarization, improving heart function33. This suggests that its beneficial effects on RV function in our study could be linked to its role in promoting tissue repair and modulating inflammation in CAD. Studies have suggested that IL-5 contributes to an atheroprotective effect, reducing plaque formation in atherosclerosis through the stimulation of natural immunoglobulin M antibodies, which target oxidized low-density lipoproteins34. Although the direct impact of IL-5 on RV function is less understood, its ability to reduce inflammatory plaque burden and promote tissue repair may indirectly contribute to improved ventricular performance, potentially explaining the strong association of IL-5 with RV function observed in this study.

In our study, IL-7 levels were associated with reduced left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), left ventricular end-diastolic mass (LVEDM), RVEDV, and RVSV, indicating a broad impact on both LV and RV function. Previous research has shown that IL-7 exacerbates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by promoting cardiomyocyte apoptosis and macrophage polarization35, which aligns with the reductions in ventricular volumes observed in our study, suggesting that IL-7 may contribute to adverse cardiac remodeling and impaired ventricular function. Moreover, our findings that RVSV was affected by IL-5, INF-γ, and IL-7 are supported by previous studies on patients undergoing LV assist device implantation, which showed that lower circulating levels of these cytokines were associated with improved cardiac function36. This highlights the potential role of these cytokines in modulating RV performance, and their interplay may influence both local cardiac remodeling and systemic inflammatory responses, ultimately affecting overall heart function.

Our results showed that LVEF was the most frequently affected outcome by various cytokines and chemokines. This is supported by evidence demonstrating that LVEF assessed through CMR is a key predictor of adverse cardiac events in CAD37. The positive associations of IL-1β, IL-18, CXCL9, and NETs with LVEF suggest that they may have a compensatory or protective role in maintaining LV function, despite their established roles in promoting inflammation. For example, IL-1β is typically associated with inflammation and fibrosis, which usually impair LVEF38. However, its association with preserved LVEF in our study indicates it may also contribute to reparative processes under certain conditions. IL-18, another cytokine commonly linked to promoting inflammation, fibrosis, and cardiac damage39, demonstrated a positive association with LVEF and negative associations with multiple cardiac outcomes, including left ventricular end-diastolic mass-to-end-diastolic volume ratio (LVEDM/LVEDV), left ventricular peak ejection rate (LVPER), and RVPFR. These results suggest that IL-18 may also play a dual role40, contributing to both inflammatory damage and compensatory mechanisms that maintain or enhance ventricular function in specific scenarios. In addition, NETs, traditionally implicated in promoting inflammation and cardiac damage41, were positively associated with LVEF in our study. This protective effect may arise from their ability to modulate inflammation by degrading excessive pro-inflammatory cytokines through their serine proteases, such as neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase. These enzymes can cleave cytokines and chemokines, limiting the amplification of inflammatory signals42. Furthermore, NETs may trap and neutralize circulating pathogens and damage-associated molecular patterns, reducing their ability to perpetuate inflammation. This containment mechanism could prevent further recruitment of immune cells to the injured myocardium, helping to resolve inflammation and limit tissue damage, ultimately preserving cardiac function43.

Our findings raise the possibility of a “sleep–inflammation–cardiac” axis, wherein sleep traits may influence cardiac phenotypes through inflammatory mediators. Although our study did not find a direct, robust causal link between sleep traits and cardiac phenotypes after accounting for pleiotropy, existing literature strongly supports a link between poor sleep and elevated systemic inflammation44. Our MR results demonstrate causal associations between specific inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-1β, IL-18) and cardiac outcomes such as LVEF, which raises the hypothesis that inflammation may mediate the effects of sleep on cardiac function. For example, IL-1β, which is known to be modulated by sleep quality45, has been implicated in cardiac fibrosis and remodeling38. This suggests that improving sleep phenotypes may potentially suppress inflammatory cytokine expression, which in turn could confer cardiac benefits, particularly in preserving systolic function. Although a formal mediation MR analysis was beyond the scope of this study, our findings offer key insights into this pathway and motivate future work to explore this mechanism. Understanding this triad could have substantial clinical implications, identifying sleep as a modifiable upstream target to attenuate inflammation and reduce cardiovascular risk.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations. First, MR estimates reflect the effects of lifelong genetic predisposition, which may not capture the impact of short-term or reversible exposures, such as acute inflammation. Second, MR assumes a linear exposure–outcome relationship, whereas the true biological effects may be nonlinear or context-dependent. Third, developmental compensation for genetic variations may attenuate observable associations. Fourth, the use of blood-derived QTL datasets may not fully capture gene regulation in tissues more directly involved in sleep or cardiac function. Fifth, although MR helps reduce confounding and reverse causation, it cannot establish mechanistic pathways. Experimental validation in animal models, cell systems, and real-world cohorts is essential to verify these associations and elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Additionally, our analysis focused on the unidirectional effects from inflammatory and sleep traits on cardiac phenotypes. Future studies incorporating bidirectional MR are warranted to determine whether cardiac structural or functional changes might influence systemic inflammation or sleep physiology.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate the substantial influence of inflammatory mediators on CMR-derived cardiac parameters, which are critical for precise quantification of cardiac performance. CMR-derived parameters provide detailed insights that are essential for the early detection of cardiac dysfunction and remodeling. By understanding how cytokines, chemokines, and sleep disorders affect these metrics, clinicians can tailor interventions to prevent cardiac deterioration, improve outcomes, and monitor treatment efficacy in at-risk populations.

Data availability

The analyzed datasets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Nedkoff, L., Briffa, T., Zemedikun, D., Herrington, S. & Wright, F. L. Global trends in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Clinical Therapeutics (2023).

Townsend, N. et al. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in Europe. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 19, 133–143 (2022).

Roth, G. A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 2982–3021 (2020).

Mavrogeni, S. I. et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of patients with cardiovascular disease: an overview of current indications, limitations, and procedures. Hellenic J. Cardiol. 70, 53–64 (2023).

Silveira Rossi, J. L. et al. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases: going beyond traditional risk factors. Diab./Metab. Res. Rev. 38, e3502 (2022).

Shukla, H., Mason, J. L. & Sabyah, A. Identifying genetic markers associated with susceptibility to cardiovascular diseases. Adv. Med. Biochem. Genom. Physiol. Pathol. 177–200 (2021).

Münzel, T. et al. Environmental risk factors and cardiovascular diseases: a comprehensive expert review. Cardiovascular. Res. 118, 2880–2902 (2022).

Alfaddagh, A. et al. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 4, 100130 (2020).

Kong, P. et al. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 7, 131 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Xu, Z. & Liu, Z. Impact of neutrophil extracellular traps on thrombosis formation: new findings and future perspective. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 910908 (2022).

Yu, S., Liu, J. & Yan, N. Endothelial dysfunction induced by extracellular neutrophil traps plays important role in the occurrence and treatment of extracellular neutrophil traps-related disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 5626 (2022).

Beijnink, C. W. et al. Cardiac MRI to visualize myocardial damage after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a review of its histologic validation. Radiology 301, 4–18 (2021).

Orrù, G. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, oxidative stress, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction an overview of predictive laboratory biomarkers. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 24, 6939–6948 (2020).

Sanderson, E. et al. Mendelian randomization. Nat. Reviews Methods Primers. 2, 6 (2022).

Jones, S. E. et al. Genome-wide association analyses of chronotype in 697,828 individuals provides insights into circadian rhythms. Nat. Commun. 10, 343 (2019).

Meyer, H. V. et al. Genetic and functional insights into the fractal structure of the heart. Nature 584, 589–594 (2020).

Aung, N. et al. Genome-wide analysis of left ventricular image-derived phenotypes identifies fourteen loci associated with cardiac morphogenesis and heart failure development. Circulation 140, 1318–1330 (2019).

Dauber, A. et al. A genome-wide Pharmacogenetic study of growth hormone responsiveness. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 105, 3203–3214 (2020).

Chen, Z., Boehnke, M., Wen, X. & Mukherjee, B. Revisiting the genome-wide significance threshold for common variant GWAS. G3 11, jkaa056 (2021).

Watanabe, K. et al. A global overview of Pleiotropy and genetic architecture in complex traits. Nat. Genet. 51, 1339–1348 (2019).

Burgess, S., Small, D. S. & Thompson, S. G. A review of instrumental variable estimators for Mendelian randomization. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 26, 2333–2355 (2017).

Burgess, S., Thompson, S. G. & Collaboration, C. C. G. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 755–764 (2011).

Burgess, S. & Bowden, J. Integrating summarized data from multiple genetic variants in Mendelian randomization: bias and coverage properties of inverse-variance weighted methods. arXiv preprint arXiv:151204486 (2015).

Hartwig, F. P., Davey Smith, G. & Bowden, J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal Pleiotropy assumption. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1985–1998 (2017).

House, I. G. et al. Macrophage-derived CXCL9 and CXCL10 are required for antitumor immune responses following immune checkpoint Blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 487–504 (2020).

Shamsi, A. et al. CXCL9 and its receptor CXCR3, an important link between inflammation and cardiovascular risks in RA patients. Inflammation 46, 2374–2385 (2023).

Castillo, E. C., Vazquez-Garza, E., Yee-Trejo, D., Garcia-Rivas, G. & Torre-Amione, G. What is the role of the inflammation in the pathogenesis of heart failure?? Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 22, 139 (2020).

Li, R. & Frangogiannis, N. G. Chemokines in cardiac fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 19, 80–91 (2021).

Sydykov, A. et al. Inflammatory mediators drive adverse right ventricular remodeling and dysfunction and serve as potential biomarkers. Front. Physiol. 9, 609 (2018).

Jung, Y-H., Ren, X., Suffredini, G., Dodd-o, J. M. & Gao, W. D. Right ventricular diastolic dysfunction and failure: a review. Heart Fail. Rev. 27, 1077–1090 (2022).

Golla, M. S. G. & Shams, P. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF). StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Pirbhat Shams declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies (2024).

Kandikattu, H. K., Venkateshaiah, S. U. & Mishra, A. Synergy of Interleukin (IL)-5 and IL-18 in eosinophil mediated pathogenesis of allergic diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 47, 83–98 (2019).

Xu, J. Y. et al. Interleukin-5-induced eosinophil population improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Cardiovascular. Res. 118, 2165–2178 (2022).

Knutsson, A. et al. Associations of interleukin-5 with plaque development and cardiovascular events. JACC: Basic. Translational Sci. 4, 891–902 (2019).

Yan, M. et al. Interleukin-7 aggravates myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury by regulating macrophage infiltration and polarization. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25, 9939–9952 (2021).

Diakos, N. A. et al. Circulating and myocardial cytokines predict cardiac structural and functional improvement in patients with heart failure undergoing mechanical circulatory support. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e020238 (2021).

Buckert, D. et al. Left ventricular ejection fraction and presence of myocardial necrosis assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging correctly risk stratify patients with stable coronary artery disease: a multi-center all-comers trial. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 106, 219–229 (2017).

Paulus, W. J. & Zile, M. R. From systemic inflammation to myocardial fibrosis: the heart failure with preserved ejection fraction paradigm revisited. Circul. Res. 128, 1451–1467 (2021).

Zhao, G. et al. Interleukin-18 accelerates cardiac inflammation and dysfunction during ischemia/reperfusion injury by transcriptional activation of CXCL16. Cell. Signal. 87, 110141 (2021).

Ihim, S. A. et al. Interleukin-18 cytokine in immunity, inflammation, and autoimmunity: biological role in induction, regulation, and treatment. Front. Immunol. 13, 919973 (2022).

Dumont, B. L. et al. Low density neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are new inflammatory players in heart failure. Can. J. Cardiol. (2024).

Hahn, J. et al. Aggregated neutrophil extracellular traps resolve inflammation by proteolysis of cytokines and chemokines and protection from antiproteases. FASEB J. 33, 1401 (2019).

Puhl, S-L. & Steffens, S. Neutrophils in post-myocardial infarction inflammation: damage vs. resolution? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 6, 25 (2019).

Petrov, K. K., Hayley, A., Catchlove, S., Savage, K. & Stough, C. Is poor self-rated sleep quality associated with elevated systemic inflammation in healthy older adults? Mech. Ageing Dev. 192, 111388 (2020).

Ballestar-Tarín, M. L., Ibáñez-del Valle, V., Mafla-España, M. A., Cauli, O. & Navarro-Martínez, R. Increased salivary IL-1 beta level is associated with poor sleep quality in university students. Diseases 11, 136 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shuhui Cao, Shangyi Yu and Zhiyun Xu carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. Shuhui cao and Hongjie Xu performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. Yangfeng Tang helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, S., Xu, H., Tang, Y. et al. Causal relationships between inflammatory mediators, sleep traits, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging-derived cardiac phenotypes. Sci Rep 15, 25118 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10929-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10929-8