Abstract

During their breeding season, male leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) spend hours perfecting their solo performance: singing unique sequences of stereotyped calls underwater to create their ‘song’. These song bouts are made up of discrete call types common across leopard seals within a region, which begs the question – what determines the individually unique patterns of these calls? Information entropy quantifies the amount of randomness in a sequence, providing insight into the statistical patterns governing a sequence. The songs produced by 26 different Eastern Antarctic leopard seals have less predictable temporal structure than humpback whale songs and dolphin whistle sequences. The estimated information entropy of the leopard seal songs is comparable to nursery rhymes but unsurprisingly, lower than contemporary, classical and baroque music. The greater structure of the leopard seal’s song improves the ability of distant listeners to accurately receive signals and identify singers, which is essential for this widely dispersed species. Future studies examining animal mating song would benefit from incorporating entropy analysis to question if information is conveyed through temporal structure alongside other acoustic variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Humans are far from the only animals to employ singing as a method of communication - animals sing for several purposes including territorial signalling, mate attraction or warning of predators1. While many bird species are known to produce complex and elaborate vocalisation bouts (hierarchically constructed of various ‘notes’, ‘elements’, ‘syllables’, ‘phrases’ and ‘motifs’)2 comparatively few mammals have been observed to assemble various vocal units or discrete sounds into more complex sequences. Examples of those that do include the ‘songs’ of rock hyraxes (Procavia capensis)3, free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis)4, gibbons (Hylobates)5,6, mice (Mus musculus)7 and humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae)8,9, the alarm calls of orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus)10, the ‘chuck’ calls of squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus)11, the ‘codas’ of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus)12,13, the whistle sequences of killer whales (Orcinus orca)14,15 and short-finned pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus)16, and ‘bray’ sequences of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus)17,18. We theorise that highly vocal pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) who produce sequential vocalisations may also be ideal candidates for information theory analysis, specifically the vociferous leopard seal.

Leopard seals are vocal during the mating season, with male leopard seals making sequences of loud stereotyped sounds underwater for the purposes of mate attraction and territorial signalling19,20,21,22. Vocal displays have been observed in phocid species when the oestrus females are inaccessible to males, and in the case of leopard seals this is due to the females remaining hauled out with their pups until weaning23. Leopard seal calling behaviour is common during December and January, which coincides with their breeding season24. Both male and female leopard seals in captivity have been shown to cease their calling behaviour with the drop in their reproductive hormones19 suggesting that the calling behaviour is an important component of mating behaviour in the leopard seal19.

Male leopard seals are solitary during spring/summer25,26,27. It is theorised that for male leopard seals, their sparse distribution amongst the pack ice and the shortness of their breeding season increases this calling behaviour, as they call for many hours each day throughout the breeding season to increase their chances of their calls being received28. Additionally, the use of vocal displays to advertise to potential mates or to communicate information about individual identity is much more energetically efficient than travelling wide distances for species with wide dispersal. As leopard seals are often widely and unpredictably dispersed29 long range acoustic displays are necessary. As such, the leopard seals’ communicative ability benefits from the use of a small repertoire of stereotyped sounds which are easily recognisable despite degradation or propagation effects23,28. This consistency of calling behaviour and stereotypy of sound types within a population makes leopard seals an ideal candidate for information theory analysis to examine their song structure.

The male leopard seals will vocalise underwater, producing a sequence of sounds in a distinct pattern before returning to the surface to breathe, creating breaks of silence in their singing cycle19. While there is geographic variation in acoustic behaviour between populations of leopard seals20,30 the alphabet of sounds within a population remains consistent30. In the coastal region of the Davis Sea, Eastern Antarctica, leopards seals produce sequences of sounds, or ‘calling bouts’, made up of an alphabet of 5 distinct stereotyped calls (Fig. 1) which range in frequency from 50 Hz to 6 kHz, and between 0.5 and 8.1 s in duration19,20. The 5 call types are classified as high double trills (H), medium single trills (M), low descending trills (D), low double trills (L) and a hoot with a low single trill (O)20,31.

While the acoustic characteristics of the sounds themselves show very little variation between individuals, the order individual seals produce sounds within a sequence varies31. The lack of stereotypy in sequencing between individual leopard seals motivates the need for probabilistic techniques to understand this variation. To analyse the leopard seal vocalisations, we have recorded sequences produced by individual seals and converted them to a symbolic code (Fig. 2).

Typical behaviour of leopard seal vocalisations - the male will sing a sequence of sounds underwater before returning to the surface to breathe (represented by a ‘Z’) and repeats this cycle for hours at a time. The sequence of sounds is then converted to a symbolic code (Microsoft PowerPoint Version 2505).

Many studies have made comparisons between marine mammal communication and human language structures, suggesting that marine mammal communication can have ‘language-like’ properties32,33. Borrowing concepts from human music theory can also prove to be a useful comparison to marine mammal communication9,12,34,35 as it does not assume any semantic meaning is contained within each individual sound. While a number of musical characteristics such as chord progressions, note duration or rhythmic elements could be compared to leopard seal songs (and analysed with information theory techniques)36 melodic contour (or the sequence of 12 notes that make up the melodic scale in Western music) is the most analogous to the symbolic code representing leopard seal vocal sequences.

Shannon’s ‘information entropy’ measures the uncertainty of a random variable37. In the context of communication, entropy is an upper bound on the amount of information contained within a sequence38 (however entropy is not necessarily a measure of complexity of the sequence or source39). Information theory37 provides insight into the structure of an information source (often referred to as ‘syntax’ or ‘grammar’ in communication) without assuming any knowledge of the meaning (or ‘semantics’) of the source output. A sequence with higher entropy is more random, or less predictable, than a sequence with lower entropy. If the true probability distribution of a vocalizing animal were known, the entropy could be computed directly. However, since these true distributions are not known, both parametric and nonparametric methods can estimate entropy. When comparing two entropy estimators for a source, the estimator whose model would better predict data from that source will result in the lower entropy estimate. Thus, the estimator with the lower entropy estimate is a better match for the structure of the source.

Our first parametric entropy estimator assumes that all calls in the sequence are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.). This model is equivalent to flipping a weighted coin a certain number of times in a row – not all outcomes are equally likely, but each new flip is completely random. Knowing the previous symbol does not improve our ability to predict the next symbol.

The second parametric model is the first-order Markov model, which assumes that the choice of each sound depends only on the sound which comes directly before it. In the field of music, Markov chains have been investigated for their potential for generating compositions, evaluation of musical complexity and composer/period identification40,41,42,43,44,45,46. Although he was far from the first, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was rumoured to have invented a game in which a pair of dice are used to select segments of pre-composed waltz-like music to create a new piece which sounded, to an untrained ear, like a waltz written by Mozart himself47,48. As a 1st order Markov model output assumes dependence on only the single preceding symbol, an nth order Markov model assumes that the output is dependent on the previous n symbols.

i.i.d. and Markov chain models are limited by underlying assumptions and cannot accurately capture the longer term dependencies in hierarchically structured sequences49. Many animal sequences are better represented by other non-Markovian processes49. Hence, we also applied the nonparametric sliding window match length (SWML) entropy estimator50,51,52. The SWML entropy estimator relates the entropy of a given output sequence to the average length of a matching string of units within a window of fixed size. The SWML estimator can highlight the presence of longer patterns in the sequence, i.e. structure that is more complex than relating one unit to its preceding unit.

If the temporal structure of the leopard seal calling bouts could be explained by an i.i.d., then we would expect the 1st order Markov entropy estimates not to be significantly lower than the i.i.d. estimates. Similarly, if the structure of the calling bouts could be explained by a 1st order Markov model, we would expect the SWML estimates not to be significantly lower than the Markov model estimates.

Do the songs of leopard seals have predictable sequence structure? And if so, how does this structure compare with that of other mammals? Here we examine the vocal sequences of 26 leopard seals and compare entropy estimates with those of other mammals including humpback whales, bottlenose dolphins and squirrel monkeys, and with simplistic representations of human music, to understand the similarities between vocal communication structure across taxa.

Results/Discussion

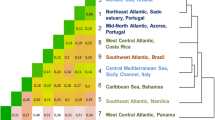

For all leopard seal calls analysed, the entropy estimates were lower than the theoretical maximum entropy for the size of the source alphabet, from which it can be inferred that the choice of sounds in the sequence is not entirely random. For the 26 leopard seals analysed, the i.i.d., 1st order Markov and SWML entropy estimates ranged from 1.59 to 2.38, 0.72–1.43 and 0.63–1.38 bits respectively (Table 1; Fig. 3).

Results of bootstrapping analysis: (a) the first hypothesis test comparing the i.i.d. to the 1st Order Markov model and (b) the second hypothesis test comparing the 1st Order Markov to the SWML entropy estimates. The horizontal bars indicate the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for the bootstrapped sequence entropy estimates. Leopard seals are numbered from 1 to 26 in order of the length of their call sequences, ranging from 151 to 1183 units.

For all leopard seals, all 1st Order Markov estimates of the entropy (\(\:{\widehat{H}}_{1}\)) lie below the one-tailed 0.95 confidence region of bootstrapped i.i.d. sequence entropy (\(\:{\widehat{H}}_{0}\)) for the hypothesis that \(\:{\widehat{H}}_{0}\le\:{\widehat{H}}_{1}\), which supports the conclusion that \(\:{\widehat{H}}_{1}<{\widehat{H}}_{0}\) with a significant of \(\:p<0.05\) (Fig. 3(a)). This implies that the leopard seal songs do have time structure, and that knowing the preceding sound in the sequence reduces uncertainty in predicting the next sound. This indicates that the i.i.d. model does not capture the structure of the leopard seal calling bouts.

The lack of a bias correction for the SWML entropy estimates limits the accuracy of these estimates. The SWML estimator is known to contain a positive bias which decreases with increasing window size53and thus we can assume that all SWML entropy estimates (including the 95% CI for the bootstrapped sequences in Fig. 3(b)) would be reduced when corrected for this bias. However, since we cannot account for this analytically, we only present a conservative estimate of significance. For 21 of the 26 leopard seals, \(\:{\widehat{H}}_{SWML}\) lies below the one-tailed 0.95 confidence region for the hypothesis that \(\:{\widehat{H}}_{1}\le\:{\widehat{H}}_{SWML}\), thus for these leopard seals we can reject the null hypothesis and infer that the structure of the calls is not fully described by a 1st order Markov model.

The only mammal species for which a SWML entropy estimate has been reported (alongside i.i.d. and 1 st order Markov estimates) are humpback whales, with entropy estimates of 0.19–0.7954,55. Mean 1st order Markov estimates have been reported for bottlenose dolphins (with both whistles at 1.15 bits17 and ‘bray’ calls at 1.5 bits18) and squirrel monkeys at 1.23 bits11 which we have compared to the leopard seal entropy estimates (Fig. 4). Direct comparison between leopard seal entropy estimates and those of the bottlenose dolphins and squirrel monkeys is made challenging due to sample size limitations and the lack of bias correction11,17,18. The negative bias inherent to both the i.i.d. and Markov models suggests that the true entropy values are higher than the mean values presented.

When we compare leopard seals with their musical human counterparts (compared specifically to the progression of musical notes in the melody), the entropy estimates of leopard seal songs are higher than those of simple nursery rhymes, indicating they have more randomness. For nursery rhymes, the 39 tunes selected from ‘The Golden Song Book’ by Katherine Tyler Wessells were found to have a mean entropy estimate (modelled as an i.i.d.) of 0.82156, within the lower range of the leopard seal estimates (Fig. 4). While the nursery rhymes were not explicitly calculated as the 1st order Markov model entropies, these values are expected to be significantly lower54. In contrast, the leopard seal calling bouts are more structurally constrained and predictable compared to the music by the Beatles43 which ranged from 2.128 to 3.319 bits. They are further constrained still when compared to the best entropy estimates for music by Classical composers (including Hasse, Mozart, Schubert, Hadyn and Mendelssohn) at 3.03 to 4.84 bits42,45 Baroque composers (including Bach, Corelli, Handel and Telemann) at 3.68 to 4.19 bits42 and Romantic composers (including Strauss and Schumann) at 3.050 to 3.397 bits45,55 (Fig. 4).

Comparison of entropy estimates of the Eastern Antarctic male leopard seals with that of the humpback whales (Hawaiian53 and Australian56), bottlenose dolphins17,18 (‘bray’ call estimate indicated by *) and squirrel monkeys11 and entropy estimates of melodic contour of various music styles (songs by the Beatles43 various Classical42,45 Baroque42 and Romantic45,55 composers, and children’s nursery rhymes54). Entropy estimation methods are indicated by colour.

The best entropy estimate values (SWML) are higher in the leopard seal song than those of the humpback whale song (Fig. 4) suggesting there could be more information within the temporal structure of the leopard seal sequences. For the humpback whales, information such as individual identity57 or advertisements of fitness58 could be conveyed through different means such as frequency and temporal characteristics58 or the repetition of motifs57 but the structure of the song is more predictable53,56. Kershenbaum et al. suggest that information can be encoded in sequences through six paradigms: repetition, diversity, combination, ordering, overlapping and timing59. For leopard seals, the entropy estimates suggest that the structure itself is crucial for conveying information, i.e. that ordering is the method by which information is conveyed. This is consistent with the notion that stereotyped calls are better suited for long distance communication amongst a widely dispersed population, as the characteristics are less likely to be lost due to signal degradation, frequency selective fading or Doppler shift23.

Change in entropy can be normalised relative to the alphabet size through an estimation of redundancy. Redundancy estimates were calculated from each of the three estimates of entropy for each leopard seal (Fig. 5). The highest estimates of redundancy, typically resulting from the SWML entropy estimate, ranged between 0.51 and 0.72 per song52,53. This is lower than that of humpback whales, which range from 0.81 to 0.96 per song53,56. This indicates that the leopard seals vocalisations, while strongly constrained, are less structurally constrained than the humpback whales.

Recording lengths of the leopard seal calling bouts ranged from 151 to 1183 units, and we used a linear regression to test whether the length of the calling bout had an impact on the estimate of entropy. Data was normally distributed and there was no evidence of heteroscedasticity. We found that the recording length (sequence length) had no influence entropy estimate (linear regression, p = 0.914, R-squared = 0.000498, Fig. 3). From this result we can infer that the recording length limits we imposed (discarding all recordings < 150 units in length) were sufficient to provide confidence in our estimates of the leopard’s seal vocalisation entropy.

Vocal behaviour varies amongst size classes of male leopard seals during the breeding season. For the smaller and potentially less fit males, the further along in the season they are, the fewer calls their sequences may contain, due most likely to the fatigue associated with this behaviour28. In contrast, the larger males maintain a more consistent call rate that does not vary throughout the breeding season28. Future studies would benefit from examining this relationship with a larger sample size.

Conclusion

Leopard seal song remains an enigmatic behaviour, but by examining the structure of the sequences we can shed light on the means by which information is encoded. From the estimates of entropy, we can infer that the leopard seal calling bouts have more sequential structure than can be fully captured by a 1st order Markov model. While the exact purpose of the leopard seal’s singing behaviour is unknown, there is a significant relationship between the typical vocal behaviour of a phocid seal and the nature of its mating system23,60. Pinniped species that breed at higher densities have more calls in their vocal repertoire than those that breed at low densities23which could mean that structure plays a more significant role in advertisements of fitness or individual identity for leopard seals as their vocal repertoire contains fewer calls. Similarly, song fulfils a variety of biological functions across many mammalian taxa, including humans. Comparing the leopard seal entropy estimates to other mammalian song systems (including human music) allows us to make inferences on the behavioural significance of sequence structure. The entropy estimates of the leopard seals being higher than those of the humpback whale suggests that there is comparatively less predictability within the leopard seal sequences, and as such more information is encoded in the structure of the sequences. From this we can infer that structure is necessary for the leopard seals to convey information over long distances, as it is less susceptible to degradation than other acoustic characteristics. This is consistent with previous observations of signalling identity in leopard seals vocal sequences31.

Using sequence structure to communicate information about the caller’s identity has been observed in other marine mammals - individual identity is coded into some acoustic coda sequences of sperm whales61,62,63. Individual leopard seals were observed to retain their particular sequences over three days31which suggests that the sequences are stable and could encode information about the singer’s identity. The presence of individual identity coding within leopard seal calling sequences should be investigated in future. While the probability laws which govern the pattern of these acoustic sequences are unknowable to us, by modelling the sequence we can gain valuable insight into the acoustic behaviour of leopard seals.

Methods

Study area and data collection

Recordings were made from November to January in 1992 to 1994 and 1997 to 1998, in the Davis Sea, Eastern Antarctica (from \(\:68^\circ\:{25}^{{\prime\:}}\text{S},\:77^\circ\:10{\prime\:}\text{E}\) to \(\:68^\circ\:{35}^{{\prime\:}}\text{S},\:77^\circ\:50{\prime\:}\text{E}\)). The recordings were made between 1600 and 0300 along the edge of the fast ice, to correspond with the period of highest vocal activity21,31. Recordings were made on 45-minute tapes with a Sony WMD6C audio-cassette recorder, a Brüel and Kjær 8103 hydrophone and a custom preamplifier, and this system had a frequency response from 35 to 15 000 Hz \(\:\pm\:\)3 dB. The hydrophone was deployed 6 m below the surface of the water. Individual seals were identified with an oil-based paint in distinctive patterns to maximise the likelihood of recording the same seal. Calls were grouped by month (November, December or January).

Call classification

Recordings were excluded when two animals were observed to be calling simultaneously or when the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was too low. Terminology often varies across taxa, as such in this study we define a ‘call’ to be a single sound unit, a ‘calling bout’ to be an unbroken string of calls delivered underwater between successive returns to the surface, and a ‘song’ to be a session of successive calling bouts. The discrete call types used in this analysis were identified in Rogers et al., 1995. Five distinct call types were identified in these recordings and annotated with the following symbol: high double trills (H), medium single trills (M), low descending trills (D), low double trills (L) and a hoot with a low single trill (O). This classification is consistent with the systems defined in20,31. A break between calling bouts, identified by a period of silence between bouts, was marked with a ‘Z’ in the sequence. Spectrograms of calls were produced using Visualization Software (LLC version 16.0) with a with a 4096 point fast Fourier Transform, 75% overlap, 50 s window, yielding 15.625 Hz frequency resolution. Calls were classified manually by a single observer and then checked by a second blind observer. To avoid pseudo-replication, only one recording of underwater vocalisations by each individual seal was included in the analysis. If the vocalising leopard seal’s identity was unknown (either because the seal had not been marked or because the seal had moved into the water prior to the arrival of the research team), the sequences were compared with those in Rogers and Cato 200231 to eliminate recordings of the same individuals.

Entropy analysis

This entropy analysis method is derived from the method detailed in Suzuki et al., 2006. The leopard seals can be considered an information source (or process) \(\:\mathcal{X}\) which produces a sequence of outputs dictated by the source’s probability law. If \(\:{X}_{i}\) is a random variable representing the source output at time \(\:i\), where \(\:{X}_{i}^{j}\)denotes\(\:\:\left({X}_{i},{X}_{i+1},\dots\:,{X}_{j}\right),\:i\le\:j,\:\)then a particular sample output (i.e. vocalising bout) of the random variable is denoted by \(\:{x}_{i}^{j}\). The probability distribution \(\:Pr\left\{X=x\right\}\) is denoted by \(\:p\left(x\right)\). The source can be considered to be stationary if all joint probability distributions are time invariant and can be considered ergodic when all outputs possess the same statistical properties. The Shannon entropy of a source can be calculated directly from the probability distribution of the source. However, since the true probability distribution of a vocalising animal is unknown, the entropy can be estimated by assuming a model distribution. The entropy of a sequence is maximised when all outcomes are equally likely. For example, a fair die has higher entropy or ‘randomness’ than a biased die, which is more predictable and thus lower entropy. Assuming that all of the sounds an animal can produce are equally likely creates an estimate of the maximum entropy.

The first model is the independent identically distributed (i.i.d.) model, which assumes that there is no time structure to the source (i.e. each output has no dependence on previous outputs). To calculate the empirical distribution from a sample sequence \(\:{x}_{1}^{l}\) of length \(\:{l}\), the probability of each output is calculated as:

Where the estimated alphabet \(\:\widehat{\mathcal{A}}\) is

The entropy can then be estimated as

The second model estimated is a first order Markov model, which assumes that each output is dependant only on the output that immediately preceded it. The empirical joint and conditional probabilities of each pair of possible outputs are calculated from the observed sample sequence.

The entropy estimate can then be calculated as

This concept can be similarly extended for higher order Markov models, i.e. an nth order Markov model assumes that the output is dependent on the previous n symbols38. As the alphabet of the seals consisted of a maximum of 6 symbols30 there are 36 theoretical transitions that are possible within the sequences. The data must be sufficiently long enough to obtain accurate estimates of the probabilities in Eqs. (4) and (5), and thus a minimum sequence length of 10 × 36 = 360 units would be appropriate to calculate an empirical probability distribution. However, in practise we observe significantly less transitions (e.g., two consecutive “Z” symbols are impossible in the sequence as a “Z” indicates a period of unlimited silence), and as such we set the minimum sequence length to be 150 symbols and discarded any sequences below this length. Higher order Markov estimates were not calculated due to these sample size constraints.

The third entropy estimator used in this study was a model-free non-parametric entropy estimator, the Sliding Window Match Length (SWML) entropy estimation. This entropy estimate is desirable as it is applicable to a broader class of sources and converges rapidly in sequence length \(\:{l}\), meaning that it produces a good estimate of the entropy from a relatively short sequence of data. Wyner and Ziv calculate the SWML entropy estimate for a stationary ergodic source with vanishing memory as:

Where \(\:n\) is equal to the width of the sliding window64. For a window size \(\:n\) and a sequence index \(\:i\), the match length \(\:{L}_{i}\left(n\right)\) is defined as

For a window of size \(\:n\) immediately preceding a symbol \(\:{x}_{i}\) in the observed sequence at index \(\:i\), the match length is the longest string of symbols inside the window which matches the symbols following \(\:{x}_{i}\). The match length is related to the source entropy via the following Eq.

The SWML entropy estimator for a stationary ergodic process is defined as follows, where \(\:n\) is the specified fixed window size and \(\:{n}_{i}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the effective window size (defined as such to remove errors in edge cases when \(\:i<n\)).

where

Even when sequence length requirements are met, both the i.i.d. and Markov models exhibit a negative bias due to Jensen’s Inequality38,51 and so we have bias corrected the entropy estimates using the Eqs. (12) and (13)65.

With \(\:\widehat{\mathcal{A}}\) and \(\:{l}\) as defined in Eq. (1), and where \(\:\widehat{\mathcal{D}}\) is equal to the number of all observed diagram transitions (pairs of symbols). In contrast, the SWML exhibits a positive bias which cannot be analytically accounted for, although it is known to be \(\:\frac{O\left(1\right)}{\text{log}n}\), and thus vanishes with increasing window size \(\:n\)53.

Two hypotheses were tested to determine whether the leopard seal vocalisations contained time structure that was captured by the Markov or SWML entropy estimates. The first hypothesis test compared the entropy estimates from the i.i.d. and 1 st Order Markov models against each other, where the null hypothesis was that the source does not have time structure (i.e. knowing the previous symbol does not reduce uncertainty about the current symbol). Thus, the null hypothesis predicts that \(\:{\widehat{H}}_{0}={\widehat{H}}_{1}\) (significance level \(\:\alpha\:=0.05\)). The alternate hypothesis is then \(\:{\widehat{H}}_{0}>{\widehat{H}}_{1}\), and this is a one-sided test as further constraining the system cannot increase the uncertainty. Similarly, we compared the 1 st order Markov model and the SWML estimate such that the second null hypothesis predicts that \(\:{\widehat{H}}_{1}={\widehat{H}}_{SWML}\), i.e. knowing more than one previous sound in a call sequence does not increase our ability to predict the next sound (thus the alternate hypothesis is \(\:{\widehat{H}}_{1}>{\widehat{H}}_{SWML}\)).

For each individual leopard seal, an empirical i.i.d. probability distribution was obtained by observing the occurrence of each sound in the call sequence. To establish bootstrap confidence bounds for the first hypothesis test, we simulated a set of 1000 bootstrap i.i.d. call sequences of equal length to each seal’s original recorded vocalisation, drawn from the empirical i.i.d. probability distribution. Next, we estimated the first order Markov model entropy for each of the synthetic sequences and calculated a 95% one-sided confidence interval for this dataset. If the 1 st order Markov entropy estimates of the leopard seal calling bouts are below this confidence bound, the result is significant, and we can reject the null hypothesis. Similarly, we established the confidence bounds for the second hypothesis test by creating 1000 sequences generated by the empirical first-order Markov model estimated from the sequence after counting all sequential pairs of sounds in each leopard seal calling bout. If the SWML entropy estimate is lower than the confidence bound of the bootstrapped Markov sequences, the first-order Markov model does not capture all of the structure in the sequence. Several studies of animal acoustical communications have compared entropy estimates from different order Markov models11,17,18 though only Suzuki et al. and Miksis-Olds et al. applied the SWML estimator to obtain a nonparametric bound on the entropy53,56.

The redundancy of each observed sequence is calculated from the entropy estimates using the Eq. (14).

The estimates of redundancy were calculated from the entropy estimator with the consistently lowest estimates of entropy.

Data and code availability

The observational data and the analysis code that support the findings of this study are available in Dryad with the identifier: http://datadryad.org/share/bzl1C1ir9UmWPaviBHZV8SUq5XtXYsDZ1HW0j55GVbw. Data will be made publicly available in Dryad upon publication. Annotated leopard seal sequence files are also provided as supplementary information files. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Lucinda Chambers (lucinda.chambers@unsw.edu.au).

References

Bradbury, J. W. & Vehrencamp, S. L. Principles of Animal Communicationvol. 132 (Sinauer Associates, 1998).

Brenowitz, E. A., Margoliash, D. & Nordeen, K. W. An introduction to birdsong and the avian song system. J. Neurobiol. 33 (5), 495–500 (1997).

Demartsev, V. et al. The progression pattern of male hyrax songs and the role of climactic ending. Sci. Rep. 7, 2794 (2017).

Bohn, K. M., Schmidt-French, B., Schwartz, C., Smotherman, M. & Pollak, G. D. Versatility and stereotypy of Free-Tailed Bat songs. PLoS One. 4, e6746 (2009).

Haraway, M. M. & Maples, E. G. Flexibility in the species-typical songs of Gibbons. Primates 39, 1 (1998).

Clarke, E., Reichard, U. H. & Zuberbühler, K. The syntax and meaning of wild Gibbon songs. PLoS One. 1, e73 (2006).

Holy, T. E. & Guo, Z. Ultrasonic songs of male mice. PLoS Biol. 3, e386 (2005).

Allen, J. A., Garland, E. C., Dunlop, R. A. & Noad, M. J. Cultural revolutions reduce complexity in the songs of humpback whales. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 285, 20182088 (2018).

Payne, R. S. & McVay, S. Songs of humpback whales. Sci. (1979). 173, 585–597 (1971).

Lameira, A. R. et al. Predator guild does not influence orangutan alarm call rates and combinations. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 67, 519–528 (2013).

McCowan, B., Doyle, L. R. & Hanser, S. F. Using information theory to assess the diversity, complexity, and development of communicative repertoires. J. Comp. Psychol. 116, 166–172 (2002).

Sharma, P. et al. Contextual and combinatorial structure in sperm Whale vocalisations. Nat. Commun. 15, 3617 (2024).

Watkins, W. A. & Schevill, W. E. Sperm Whale Codas. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 62, 1485–1490 (1977).

Riesch, R., Ford, J. K. B. & Thomsen, F. Whistle sequences in wild killer whales (Orcinus orca). J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 124, 1822–1829 (2008).

Selbmann, A., Miller, P. J. O., Wensveen, P. J., Svavarsson, J. & Samarra, F. I. P. Call combination patterns in Icelandic killer whales (Orcinus orca). Sci. Rep. 13, 21771 (2023).

Sayigh, L., Quick, N., Hastie, G. & Tyack, P. Repeated call types in short-finned pilot whales, Globicephala macrorhynchus. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 29, 312–324 (2013).

McCowan, B., Hanser, S. F. & Doyle, L. R. Quantitative tools for comparing animal communication systems: information theory applied to bottlenose Dolphin whistle repertoires. Anim. Behav. 57, 409–419 (1999).

Luís, A. R., Alves, I. S., Sobreira, F. V., Couchinho, M. N. & dos Santos, M. E. Brays and bits: information theory applied to acoustic communication sequences of bottlenose dolphins. Bioacoustics 28, 286–296 (2019).

Rogers, T. L., Cato, D. H. & Bryden, M. M. Behavioral significance of underwater vocalizations of captive Leopard seals, Hydrurga leptonyx. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 12, 414–427 (1996).

Stirling, I. & Siniff, D. Underwater vocalizations of Leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) and crabeater seals (Lobodon carcinophagus) near the South Shetland islands, Antarctica. Can. J. Zool. 57, 1244–1248 (1979).

Thomas, J. A. & DeMaster, D. P. An acoustic technique for determining diurnal activities in Leopard (Hydrurga leptonyx) and crabeater (Lobodon carcinophagus) seal. Can. J. Zool. 60, 2028–2031 (1982).

Rogers, T. L. Source levels of the underwater calls of a male Leopard seal. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 136, 1495–1498 (2014).

Rogers, T. L. Factors influencing the acoustic behaviour of male phocid seals. Aquat. Mamm. 29, 247–260 (2003).

Shabangu, F. W. & Rogers, T. L. Summer circumpolar acoustic occurrence and call rates of ross, Ommatophoca rossii, and leopard, Hydrurga leptonyx, seals in the Southern ocean. Polar Biol. 44, 433–450 (2021).

Borsa, P. Seasonal occurrence of the Leopard seal, Hydrurga leptonyx, in the kerguelen Islands. Can. J. Zool. 68, 405–408 (1990).

Meade, J. et al. Spatial patterns in activity of Leopard seals Hydrurga leptonyx in relation to sea ice. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser. 521, 265–275 (2015).

Rogers, T. & Bryden, M. M. Predation of adélie Penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae) by Leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) in Prydz bay, Antarctica. Can. J. Zool. 73, 1001–1004 (1995).

Rogers, T. L. Calling underwater is a costly signal: size-related differences in the call rates of Antarctic Leopard seals. Curr. Zool. 63, 433–443 (2017).

Rogers, T. L. & Bryden, M. M. Density and haul-out behaviour of Leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) in Prydz bay, Antarctica. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 13, 293–302 (1997).

Rogers, T., Cato, D. H. & Bryden, M. M. Underwater vocal repertoire of the Leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) in Prydz bay, Antarctica. in Sensory Abilities of Aquatic Animals (ed Kastelein, R. A. et al.) 223–236 (DeSpil., Amsterdam, 1995).

Rogers, T. & Cato, D. Individual variation in the acoustic behaviour of the adult male Leopard seal, Hydrurga leptonyx. Behaviour 139, 1267–1286 (2002).

Arnon, I. et al. Whale song shows language-like statistical structure. Sci. (1979). 387, 649–653 (2025).

Youngblood, M. Language-like efficiency in Whale communication. Sci. Adv. 11, eads6014 (2025).

Hersh, T. A., Ravignani, A. & Whitehead, H. Cetaceans are the next frontier for vocal rhythm research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, (2024).

Fitch, W. T. The evolution of music in comparative perspective. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1060, 29–49 (2005).

Rohrmeier, M., Zuidema, W., Wiggins, G. A. & Scharff, C. Principles of structure Building in music, Language and animal song. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 370, 20140097 (2015).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

Cover, T. M. & Thomas, J. A. Elements of Information Theory (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006).

Kershenbaum, A. Entropy rate as a measure of animal vocal complexity. Bioacoustics 23, 195–208 (2014).

Ames, C. The Markov process as a compositional model: A survey and tutorial. MIT Press. 22, 175–187 (1989).

Manzara, L. C., Witten, I. H. & James, M. On the entropy of music: an experiment with Bach chorale melodies. Leonardo Music J. 2, 81 (1992).

Margulis, E. H. & Beatty, A. P. Musical style, psychoaesthetics, and prospects for entropy as an analytic tool. Comput. Music J. 32, 64–78 (2008).

Gündüz, G. Entropy, energy, and instability in music. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 609, 128365 (2023).

Moore, J. M., Corrêa, D. C. & Small, M. Is bach’s brain a Markov chain? Recurrence quantification to assess Markov order for short, symbolic, musical compositions. Chaos: Interdisc. J. Nonlinear Sci. 28, 085715 (2018).

Knopoff, L. & Hutchinson, W. Entropy as a measure of style: the influence of sample length. J. Music Ther. 27, 75–97 (1983).

Pollastri, E. & Simoncelli, G. Classification of melodies by composer with hidden Markov models. in Proceedings First International Conference on WEB Delivering of Music. WEDELMUSIC 88–95 (IEEE Comput. Soc, 2001). 88–95 (IEEE Comput. Soc, 2001). (2001). https://doi.org/10.1109/WDM.2001.990162

Hedges, S. A. Dice music in the eighteenth century. Music Lett. 59, 180–187 (1978).

Collins, T., Laney, R., Willis, A., Garthwaite, P. H. & Chopin Mazurkas Markov Significance 8, 154–159 (2011).

Kershenbaum, A. et al. Animal vocal sequences: not the Markov chains we thought they were. Proc. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 281, 20141370 (2014).

Wyner, A. D. & Ziv, J. The sliding-window Lempel-Ziv algorithm is asymptotically optimal. Proc. IEEE. 82, 872–877 (1994).

Wyner, A. D., Ziv, J. & Wyner, A. J. On the role of pattern matching in information theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 44, 2045–2056 (1998).

Ziv, J. & Lempel, A. A universal algorithm for sequential data compression. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 23, 337–343 (1977).

Suzuki, R., Buck, J. R. & Tyack, P. L. Information entropy of humpback Whale songs. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 119, 1849–1866 (2006).

Pinkerton, R. Information theory and melody. Sci. Am. 194, 77–87 (1956).

Youngblood, J. E. Style as information. J. Music Theory. 2, 24 (1958).

Miksis-Olds, J. L., Buck, J. R., Noad, M. J. & Cato, D. H. Dale stokes, M. Information theory analysis of Australian humpback Whale song. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 124, 2385–2393 (2008).

Lamoni, L. et al. Variability in humpback Whale songs reveals how individuals can be distinctive when sharing a complex vocal display. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 153, 2238–2250 (2023).

Parsons, E. C. M., Wright, A. J. & Gore, M. A. The nature of humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) song. J. Mar. Anim. Ecol. 1, 22–31 (2008).

Kershenbaum, A. et al. Acoustic sequences in non-human animals: a tutorial review and prospectus. Biol. Rev. 91, 13–52 (2016).

Stirling, I. & Thomas, J. A. Relationships between underwater vocalizations and mating systems in phocid seals. Aquat. Mamm. 29, 227–246 (2003).

Oliveira, C. et al. Sperm Whale Codas May encode individuality as well as clan identity. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 139, 2860–2869 (2016).

Antunes, R. et al. Individually distinctive acoustic features in sperm Whale Codas. Anim. Behav. 81, 723–730 (2011).

Gero, S., Whitehead, H. & Rendell, L. Individual, unit and vocal clan level identity cues in sperm Whale Codas. R Soc. Open. Sci. 3, 150372 (2016).

Wyner, A. D. & Ziv, J. Some asymptotic properties of the entropy of a stationary ergodic data source with applications to data compression. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 35, 1250–1258 (1989).

Basharin, G. P. On a statistical estimate for the entropy of a sequence of independent random variables. Theory Probab. Its Appl. 4, 333–336 (1959).

Payne, K., Tyack, P. & Payne, R. Progressive changes in the songs of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae): A detailed analysis of two seasons in Hawaii. in Communication and Behavior of Whales, AAAS Selected Symposium 76 (ed. Payne, R.) 9–58Westview, Boulder, CO, (1983).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Michaela Ciaglia, who acted as the second observer on the call counting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.R. recorded the leopard seal vocalisations and annotated the call recordings. J.B. created the analysis methodology. L.C. conducted the entropy analysis, prepared all figures and wrote the main manuscript text. All authors were involved in project conception, manuscript production and revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

No authors are in present or anticipated employment by any organization that may gain or lose financially through this publication. No authors have any financial interests that could directly undermine, or be perceived to undermine the objectivity, integrity and value of this publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chambers, L.E.H., Buck, J.R. & Rogers, T.L. Leopard seal song patterns have similar predictability to nursery rhymes. Sci Rep 15, 26099 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11008-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11008-8