Abstract

This study scrutinizes the mediating role of sleep disturbance in the relationship between problematic smartphone use and dry eye disease and examines the moderating role of physical activity. A total of 2202 high school students from twelve regions of Morocco completed the Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version (SAS-SV), the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and the Dry Eye Questionnaire-5 (DEQ-5). Participants were also asked to rate the number of days per week during which they performed physical activity for at least 60 min. Our findings indicated that 50% of participants were problematic smartphone users, 39.3% suffered from dry eye disease and 38.3% suffered from sleep problems. The results suggested that sleep disorder mediated partially the relationship between problematic smartphone use and dry eye disease. Physical activity (at least 180 min per week) influenced the relationship between problematic smartphone use and dry eye disease. Specifically, it moderated both the direct link between smartphone use and dry eye, and the indirect link mediated by sleep disorders. This moderating effect was significant (index = − 0.0218, 95% CI [− 0.0260, − 0.0173]). These results offer valuable insights for preventing and managing sleep disturbances and dry eye disease linked to problematic smartphone use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The digital era, of which we are a part, requires from us prolonged and frequent use of tools described as intelligent, including smartphones. Therefore, a new concept of behavioral dependence arises: dependance to smartphone or problematic smartphone use (PSU). The symptoms of dependence/addiction approved by DMS-5 are not only psychological: craving, loss of control and salience, but also physical: tolerance and withdrawal1,2. Several research have been carried out to verify the conformity of the symptoms manifested by problematic users of smartphones with those proposed by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Yet, the insufficiency of neurobiological data in this area has prevented its integration into the DSM-5 which is the reference guide for diagnosing a variety of mental illnesses3,4.

Nevertheless, according to existing neurobiological studies, the reward circuit regulates the establishment and maintenance of addictions. Three central elements of the mesolimbic brain circuit are known to play a role in behavioral addictions: the Nucleus Accumbens (NAcc), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and amygdala5. The NACC and amygdala form the impulsive system responsible for automatic and impulsive behavior, and the ACC reflective system inhibits responses to impulses (see Fig. 1). The imbalance between these two neuronal systems is involved in all addictive states6.

Neurophysiological components involved in addiction are similar to those of sleep disturbance7. In fact, chronic sleep disorders lead to the imbalance of impulsivity/inhibition in favor of impulsivity which can gravitate toward risky behaviors8. The association between poor sleep quality and PSU, as a risky behavior, has been supported by several studies9,10. Two principal facets of sleep problems—sleep duration and quality—have been extensively studied10,11,12,13. Carter’s systematic review reported that bedtime media device use increase inadequate sleep quantity and excessive daytime sleepiness by respectively 2.17 and 2.72 times14. A subsequent systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Sohn et al. also states that children and young adults suffering from PSU are 2.6 times exposed to sleep disorders than those who do not suffer from it15. These findings were supported by later longitudinal studies which found a bidirectional relationship between PSU and sleep disruption among adolescents16,17.

Besides, overuse of smartphones is described as a risk factor of ocular complaints such as dry eye disease (DED) and myopia18,19. DED is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface manifested by burning, tingling, photophobia, foreign body sensation, and visual disturbances. These symptoms hinder productivity, performance, and subsequently the quality of life of individuals18,20. Several factors are behind dry eyes, notably older age, female gender, and glandular (e.g. meibomian gland), nervous, and immune dysfunctions. Other environmental factors may contribute to DED including humidity and air pollution, prolonged reading and exposure to light sources21. Stapleton’s review affirmed that the prevalence of DED ranged respectively from 5.5% to 23.1 and 5% to 30% in children and adults and emphasizes its association with time spent on digital devices. Synchronously, Galor’s review highlighted the impact of lifestyle on the increase of DED in contemporary life22. Thus, in the digital age, the adoption of a steadily sedentary lifestyle is remarkable among the general population, especially among adolescents, reducing their physical activity23. At the same time, an extensive body of research has explored the circumstances behind this decrease in physical activity and greater attention has been dedicated to the contribution of PSU24,25,26,27,28,29. Furthermore, Xiao’s meta-analysis of observational studies demonstrated a moderate negative correlation between physical exercise and PSU30.

Since PSU, DED, physical activity, and sleep disorder were interconnected, it was intriguing to explore the relationships between these variables among Moroccan high school students according to the hypothetical model of Fig. 2 by using a cross-sectional design (see Fig. 2). by using a cross-sectional design. This particular demographic was chosen because adolescents, who constitute the high school population, are known from prior research to be especially susceptible to PSU4,15. So, we formulated the following hypotheses:

-

PSU is expected to be negatively associated with healthy sleep (Hypothesis 1a), and physical activity (Hypothesis 1b).

-

PSU is assumed to be positively associated with DED symptoms (Hypothesis 2).

-

Sleep disturbance is expected to mediate the relationship between PSU severity and DED (Hypothesis 3).

-

Physical activity is assumed to moderate the relationship between PSU and sleep disturbance, and PSU and DED severity (Hypothesis 4).

Methods

Study design and procedure

This is a cross-sectional study, conducted from December 2023 to May 2024. A total of 2202 adolescent students were recruited residing in different governorates of Morocco (12 governorates).

Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Data was collected using two methods. First, a snowball sampling technique was employed, using a Google Form questionnaire distributed electronically. Respondents across the 12 governorates acted as initial "seeds," forwarding the questionnaire within their regions. Second, paper copies of the questionnaire were distributed to randomly selected high schools. Researchers briefly explained the study’s objectives and questionnaire instructions, encouraging participants to complete the questionnaire individually and honestly. Participants were given 40–60 min to complete the questionnaire. To minimize response bias, no school personnel or teachers were present in the classrooms during data collection. The questionnaires were distributed after securing permission from school principals and informed consent from the parents’ association. Furthermore, an oral assent was requested from all students who were to participate; only the students who explicitly indicated their desire to take part in the survey stayed in the classroom. No credit was received for participation. Ethical approval for this project was obtained from the hospital-university ethics committee of Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University (N°16/22). Thus, the study protocol met the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study instruments

The first part of the questionnaire gave information on the objectives of the current study and the anonymity of the collected responses. In the electronic approach, each participant had to select the option indicating his/her consent to participate in this study in order to access the questionnaire.

The second part of the questionnaire concerned the socio-demographic data of the participants (age, gender, location type, socio-economic status, parental education level).

The third part consisted of the following scales:

Smartphone addiction scale-short version (SAS-SV)

The SAS-SV is a short version of the original SAS. Constituted of 10 items measured on 6-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), and capturing six addictive symptoms (loss of control, disruption of family or schooling, disregard for consequences, withdrawal, preoccupation, and tolerance)31. This scale is used to evaluate smartphone addiction among teenagers and adults32. The total score ranged from 10 to 60 and higher scores indicated higher smartphone addiction. A cutoff score of 33 for females and 31 for males can be used to recognize excessive smartphone users. This tool was cross-culturally validated in Moroccan context and its Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.8733. In this study, the SAS-SV Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.851.

Dry eye questionnaire-5 (DEQ-5)

It is a short subset of DEQ scale. It contains 5 items that assess the frequency of watery eye, discomfort and dryness within the previous month, and intensity of discomfort and dryness at the end of the day. A 5-point Likert scale was used to respond to the frequency of watery eye, discomfort, and dryness, while a 6-point Likert was used to respond to the intensity of discomfort and dryness. The total score of the DEQ-5 scale was obtained by summing the scores of all the items. Its values vary between 0 and 2234. Internal consistency and reliability of the Arabic version of DEQ-5 were excellent and its Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.8035. In this study, the DEQ-5 Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.832.

Insomnia severity index (ISI)

The ISI is one of the most used scales for screening insomnia. It is a seven-item instrument, which integrates both International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) and DSM-5 criteria to assess insomnia. A 5-point Likert scale is used to score each item (0 = no problem, 4 = very serious problem), which gives a total score ranging from 0 to 28. The total score is interpreted as follows: absence of insomnia (0–7), subthreshold insomnia (8–14), moderate insomnia (15–21), and severe insomnia (22–28)36. This scale was cross-culturally validated in Moroccan context, and its Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.8337. In this study, the ISI Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.795.

Furthermore, participants were asked to rate the number of days per week during which they performed physical activity for at least 60 min. for this, 5 cases were considered: no day, one day, two days, 3 days, more than 3 days. According to the global recommendations on physical activity for health, daily physical activity of at least 60 min at least three times a week is necessary for lower rates of non-communicable chronic diseases38. Thus, physical activity durations were dichotomized into two categories: less than 180 min and more or equal to 180 min per week.

Respondents were also asked a binary (yes/no) question in the questionnaire regarding prior eye surgery or an active eye condition.

Statistical analysis

For a study involving a population of 1,050,535 Moroccan high school students39, a sample of 2166 students was deemed necessary. The sample size was determined using the following formula:

n = sample size, z = z-score corresponding to the desired confidence level from the standard normal distribution (for a 99.9% confidence level, z = 3.291), p = estimated proportion of the population that possesses the characteristic (p = 0.5 is used, for the greatest dispersion), e = tolerable margin of error (5%).

Since we used a stratified cluster sampling approach, we adjusted the sample size with a design effect of 2.

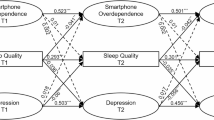

Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS (version 25). Incomplete questionnaires, as well as respondents who reported having active eye disease or having undergone recent eye surgery were excluded from the database. Cronbach’s alpha values were computed for each scale. Scale scores were treated as continuous variables and were normally distributed with their skewness and kurtosis varying between − 1 and + 1. After descriptive analyses, Pearson’s correlation was used to explore correlations between continuous variables, while t tests and chi-square tests were used to compare groups. Before developing the regression analyses, the assumptions were tested. The scatterplot was generated to check the linear relationship between the variables of interest. Absence of multicollinearity was justified by the value of variance inflation factor (VIF) not exceeding 4 for the variables entered as predictors in the model. Homoscedasticity assumption wasn’t met, so the heteroscedasticity-consistent inference HC3 option was used as a robust method to estimate standard errors. The PROCESS v4.0 plugin developed by Hayes, model 8 was used to compute a conditional indirect effect (see Fig. 2) in a moderated mediation analysis, and bootstrapping procedure was employed involving 5000 iterations to create a 95% confidence interval for the samples. Female gender and air pollution were previously reported to be positively related to DED21. That’s why we controlled for gender and location type by including them as covariates in the moderated mediation model. Path “a” denoted the link between PSU and ISI; the relationship between ISI and DEQ-5 was denoted by path “b”; path “c’” (the direct effect) denoted the association between PSU and DEQ-5 after the inclusion of ISI and physical activity in the model (see Fig. 2).

Results

Among the 1550 questionnaires collected during the paper approach of the survey, 1435 questionnaires were fully completed by Moroccan high school students who did not suffer from active eye disease and/or had not undergone eye surgery. The response rate then reached 92.6% for this approach. The fact of simultaneously using online snowball sampling as a second approach did not allow us to evaluate the total response rate to the survey. A sample of 2202 high school students was reached.

Participants’ age varied between 14 and 23 years. Most respondents were female (59%), from an urban area (72.5%), and of intermediate socioeconomic status (74.1%). Regarding parents’ level of education, the percentage of fathers with a university degree was higher (29.3%) than that of mothers (16.5%) (Table 1).

In a study of 2202 high school students, 50% (95% CI 52.08–47.91.1%) were identified as problematic smartphone users, while 39.3% (95% CI 41.34–37.25%) suffered from dry eye disease (DED) and 38.3% (95% CI 40.33–36.26%) experienced sleep problems. Regarding physical activity, the percentage of participants who had a duration of physical activity less than 180 min per week was lower (44%) than that of participants who had a duration of physical activity greater than 180 min per week (56%).

Bivariate analysis

The association between physical activity and PSU, ISI, and DEQ-5 severity was assessed by the t-tests. As shown in Table 2, it was found that participants who had a duration of physical activity less than 180 min per week had a significant higher mean score than their counterpart who had a duration of physical activity greater than 180 min per week for PSU (t = − 22.168, p < 0.001), ISI (t = − 47.283, p < 0.001), and DEQ-5 (t = − 73.968, p < 0.001). However, the chi-square test highlighted a significant association between PSU and a daily duration of smartphone use greater than or equal to 5 h (OR 2.626, p < 0.001), a duration greater than or equal to 1 h per session (OR 2.564, p < 0.001), and smartphone use both in the morning just after waking up and before going to bed (OR 16.00, p < 0.001). In addition, girls were more likely to suffer from PSU than boys (OR 1.315, p = 0.002), while the latter were more engaged in physical activity (OR 1.834, p < 0.001).

As mentioned in Table 3, all continuous variables are normally distributed as measured by skewness and kurtosis indices. According to Pearson correlation analyses, PSU was significantly and positively associated with ISI and DEQ-5. Moreover, ISI was significantly and positively associated with DEQ-5.

Moderated mediation analysis

The moderated mediation analysis showed significant findings (see Table 4). The overall model was significant, F (6,2195) = 2621.8734, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.895. The conditional direct effect (path c’) and the conditional indirect effect of PSU on DEQ-5 were significant (p < 0.001) after controlling for gender and location type. However, as visualized in Figs. 3 and 4 (see Figs. 3 and 4), these effects were stronger for participants with less than 180 min of physical activity per week than for those with more than 180 min per week.

Discussion

The current study investigated the links between PSU, sleep disturbance, and DED in Moroccan high school students. We also examined whether physical activity moderated these relationships. Our findings indicate that sleep disorders partially mediate the relationship between PSU and DED. Moreover, engaging in 180 min or more of physical activity per week moderated both the direct association between PSU and DED and the indirect effect of PSU on DED via sleep disturbance. This supported our fourth hypothesis, as the moderated mediation index was significant (index = − 0.0218, 95% CI [− 0.0260, − 0.0173]).The main findings of the present study will be discussed below.

This study indicated that problematic smartphone users check their smartphones both before going to bed and just after waking up in the morning compared to non-problematic smartphone users. In addition, a long daily duration and per session of smartphone use were significantly linked to PSU. These results were congruent with previous findings4,15,40,41,42. The main reason for the increase in time spent consulting smartphones is the tremendous number of services provided by this tool, which has completely penetrated all aspects of students’ daily lives27.

As prior research suggested18,19, the current study manifested that while controlling for gender and location type, PSU and DED symptoms were positively correlated (confirmation of Hypothesis 2). Mehra et Galor found out that prolonged and continuous daily use of digital screens, such as smartphones, have been associated with dry eye and that a daily duration of exposure to screens greater than or equal to 5 h was a risk factor for developing DE diagnosis and symptoms21. Two main mechanisms were behind the association between excessive exposure to smartphones screens and DED. The first one was frequency and amplitude of blinks reduction during prolonged use of the smartphone, which induces the loss of tear film homeostasis. The second expected contributor to DED was the blue light emitted by smartphone screens. Despite blue light from smartphones being within safety limits, some researchers observed, in vitro, reduced cell viability and increased reactive oxygen species in human corneal and conjunctival cells exposed to it. These cellular responses, potentially linked to ocular surface inflammation, could worsen DED symptoms. Especially since an association between dry eye symptoms and ocular surface inflammation has been observed in screen users. Consequently, concerns remain among certain research groups regarding the long-term effects of repeated blue light exposure from digital screens21,43,44.

The present study highlighted the indirect effect of PSU on DED via sleep disorder (confirmation of Hypothesis 3). The latter mediated the relationship between PSU and DED, and students suffering from both PSU and sleep disorder experienced severe DED symptoms. According to the findings reported by the Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) Workshop report, an association between DED and sleep disorder was consistently documented22. Among the potential explanations for this association, we cite the disruption of hormones concentration (e.g. androgens, norepinephrine and cortisol) and the circadian rhythm, caused by sleep disorder, which affects tear secretion. It has also been shown that sleep disturbance reduces parasympathetic activity which can dampen tear flow22. The link between PSU and sleep disorder has been explained by the emitting of blue light during nocturnal use of the smartphone. This disrupts the circadian rhythm and the pineal gland activity, affecting the melatonin secretion which is necessary for regulation of biological rhythms such as wake/sleep45,46,47.

As expected, problematic smartphone use was negatively associated with healthy sleep and physical activity duration (confirmation of Hypothesis 1a and 1b respectively). Moreover, the current study displayed that physical activity duration was reversely correlated with DED and sleep disturbance. Yang et al. disclosed that physical activity was a significant protective factor against PSU (β = − 0.266, P < 0.001), especially when it involves an aerobic endurance type physical activity27. So, physical activity has been among the factors explored to develop PSU prevention programs among adolescents. Liu’s meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials has summarized previous evidence and revealed the reducing effect of physical exercise on key symptoms of addiction such as withdrawal as well as on the total PSU score48. Moreover, Navarro-Lopez et al. stated that physical activity promoted the proper functioning of the tear film by increasing tears volume and reducing the concentration of several biomarkers of inflammation (e.g. cytokines) and oxidative stress. These parameters collectively contributed to alleviating DED symptoms49.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations, so all findings should be interpreted with caution. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, it was not attainable to conclude a causal association between the variables. Therefore, our findings should be extended by longitudinal investigations to restore the temporality of the observed moderated mediation effects between the variables of interest. Second, our sample did not include unschooled adolescents. This could bias the results and limit their generalizability to all Moroccan high school students. Third, we assessed data via self-report which might be subject to social desirability. The inclusion of objective measures regarding dry eyes and weekly duration of physical activity as well as daily duration of smartphone use could address this limitation in future studies.

Conclusion

To conclude, the present study reveals that problematic smartphone use could contribute to dry eyes. A weekly physical activity duration of less than 180 min combined with unhealthy sleep could aggravate this association. Thus, a weekly duration of physical activity greater than 180 min may contribute to a reduction of sleep disorder and the problematic use of smartphone and eventually avoiding dry eyes. For this reason, it would be particularly important to implement early intervention school programs encouraging physical activity and adequate use of smartphones to anchor adolescents’ healthy behaviors for their well-being.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Reer, F., Wehden, L. O., Janzik, R. & Quandt, T. Examining the interplay of smartphone use disorder, mental health, and physical symptoms. Front. Public Health 10, 834835 (2022).

Harris, B., Regan, T., Schueler, J. & Fields, S. A. Problematic mobile phone and smartphone use scales: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 11, 672 (2020).

Potenza, M. N. Clinical neuropsychiatric considerations regarding nonsubstance or behavioral addictions. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 19(3), 281–291 (2017).

Bouazza, S., Abbouyi, S., El Kinany, S., El Rhazi, K. & Zarrouq, B. Association between problematic use of smartphones and mental health in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(4), 2891 (2023).

Tymofiyeva, O. et al. Neural correlates of smartphone dependence in adolescents. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 564629 (2020).

Noël, X., Brevers, D. & Bechara, A. A neurocognitive approach to understanding the neurobiology of addiction. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 23(4), 632–638 (2013).

Ek, J., Jacobs, W., Kaylor, B. & McCall, W. V. Addiction and sleep disorders. Med. Biol. 1297, 163–171 (2021).

López-Muciño, L. A. et al. Sleep loss and addiction. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 141, 104832 (2022).

Li, Y., Li, G., Liu, L. & Wu, H. Correlations between mobile phone addiction and anxiety, depression, impulsivity, and poor sleep quality among college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Behav. Addict. 9(3), 551–571 (2020).

Kim, S. Y. et al. The relationship between smartphone overuse and sleep in younger children: A prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 16(7), 1133–1139 (2020).

Huang, Q. et al. Smartphone use and sleep quality in Chinese college students: A preliminary study. Front. Psychiatry 11, 352 (2020).

Kaya, F., Bostanci Daştan, N. & Durar, E. Smart phone usage, sleep quality and depression in university students. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 67(5), 407–414 (2021).

Mei, S. et al. Health risks of mobile phone addiction among college students in China. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 21(4), 2650–2665 (2023).

Carter, B., Rees, P., Hale, L., Bhattacharjee, D. & Paradkar, M. S. Association between portable screen-based media device access or use and sleep outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. Pediatr. 170(12), 1202–1208 (2016).

Sohn, S. Y., Rees, P., Wildridge, B., Kalk, N. J. & Carter, B. Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: A systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 19(1), 356 (2019).

Chen, J. K. & Wu, W. C. Reciprocal relationships between sleep problems and problematic smartphone use in Taiwan: Cross-lagged panel study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(14), 7438 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Longitudinal association between problematic smartphone use and sleep disorder among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict. Behav. 144, 107715 (2023).

Al-Mohtaseb, Z., Schachter, S., Shen Lee, B., Garlich, J. & Trattler, W. The Relationship between dry eye disease and digital screen use. Clin. Ophthalmol. Auckl NZ. 15, 3811–3820 (2021).

Mccrann, S., Loughman, J., Butler, J. S., Paudel, N. & Flitcroft, D. I. Smartphone use as a possible risk factor for myopia. Clin. Exp. Optom. 104(1), 35–41 (2021).

Stapleton, F., Velez, F. G., Lau, C. & Wolffsohn, J. S. Dry eye disease in the young: a narrative review. Ocul. Surf. 31, 11–20 (2024).

Mehra, D. & Galor, A. Digital screen use and dry eye: A review. Asia-Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 9(6), 491–497 (2020).

Galor, A. et al. TFOS lifestyle: Impact of lifestyle challenges on the ocular surface. Ocul. Surf. 28, 262–303 (2023).

Toth, L. et al. Time trends in physical activity using wearable devices: Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in children, adolescents, and adults 1995–2017. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 54(2), 288 (2021).

Huang, P. C. et al. Temporal associations between physical activity and three types of problematic use of the internet: A 6-month longitudinal study. J. Behav. Addict. 11(4), 1055–1067 (2022).

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., Sanders, G. J., Rebold, M. & Gates, P. The relationship between cell phone use, physical and sedentary activity, and cardiorespiratory fitness in a sample of U.S. college students. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 10(1), 79 (2013).

Saffari, M. et al. Effects of weight-related self-stigma and smartphone addiction on female university students’ physical activity levels. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19(5), 2631 (2022).

Yang, G. et al. Physical activity influences the mobile phone addiction among Chinese undergraduates: The moderating effect of exercise type. J. Behav. Addict. 10(3), 799–810 (2021).

Zhu, L. et al. Physical activity, problematic smartphone use, and burnout among Chinese college students. PeerJ 11, e16270 (2023).

Pereira, F. S., Bevilacqua, G. G., Coimbra, D. R. & Andrade, A. Impact of problematic smartphone use on mental health of adolescent students: Association with mood, symptoms of depression, and physical activity. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 23(9), 619–626 (2020).

Xiao, W. et al. The relationship between physical activity and mobile phone addiction among adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. JMIR. Public Health Surveill. 8(12), e41606 (2022).

Lopez-Fernandez, O. Short version of the smartphone addiction scale adapted to Spanish and French: Towards a cross-cultural research in problematic mobile phone use. Addict. Behav. 64, 275–280 (2017).

Kwon, M., Kim, D. J., Cho, H. & Yang, S. The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS ONE 8(12), e83558 (2013).

Sfendla, A. et al. Reliability of the Arabic smartphone Addiction scale and smartphone addiction scale-short version in two different Moroccan samples. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 21(5), 325–332 (2018).

Chalmers, R. L., Begley, C. G. & Caffery, B. Validation of the 5-item dry eye questionnaire (DEQ-5): Discrimination across self-assessed severity and aqueous tear deficient dry eye diagnoses. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 33(2), 55–60 (2010).

Bouazza, S. et al. Cross-cultural validation of the Arabic version of the dry eye questionnaire-5 (DEQ-5) scale. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 95(6), e2024171–e2024171 (2024).

Manzar, M. D., Jahrami, H. A. & Bahammam, A. S. Structural validity of the insomnia severity index: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 60, 101531 (2021).

Oneib, B., El Filali, A. & Abda, N. The Moroccan dialect version of the insomnia severity index. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry. 29(1), 11 (2022).

Organization WH. Recommandations mondiales sur l’activité physique pour la santé. Organisation mondiale de la Santé (2010). https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44436. Accessed 17 Nov 2023.

Bilan MENPS 22-23-FR-VF.pdf. https://www.men.gov.ma/Ar/Documents/Bilan%20MENPS%2022-23-%20FR%20-%20VF.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2024.

Tangmunkongvorakul, A. et al. Factors associated with smartphone addiction: A comparative study between Japanese and Thai high school students. PLoS ONE 15(9), e0238459 (2020).

Susmitha, T. S., Rao, S. J. & Doshi, D. Influence of smartphone addiction on sleep and mental wellbeing among dental students. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 25, 101447 (2024).

Kliesener, T., Meigen, C., Kiess, W. & Poulain, T. Associations between problematic smartphone use and behavioural difficulties, quality of life, and school performance among children and adolescents. BMC Psychiatry 22, 195 (2022).

Wong, N. A. & Bahmani, H. A review of the current state of research on artificial blue light safety as it applies to digital devices. Heliyon 8(8), e10282 (2022).

Cougnard-Gregoire, A. et al. Blue light exposure: Ocular hazards and prevention—a narrative review. Ophthalmol. Ther. 12(2), 755–788 (2023).

Akbari, M., Seydavi, M., Sheikhi, S. & Spada, M. M. Problematic smartphone use and sleep disturbance: The roles of metacognitions, desire thinking, and emotion regulation. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1137533 (2023).

Jniene, A. et al. Perception of sleep disturbances due to bedtime use of blue light-emitting devices and its impact on habits and sleep quality among young medical students. BioMed. Res. Int. 2019, 7012350 (2019).

Schurhoff, N. & Toborek, M. Circadian rhythms in the blood–brain barrier: Impact on neurological disorders and stress responses. Mol. Brain. 16, 5 (2023).

Liu, S., Xiao, T., Yang, L. & Loprinzi, P. D. Exercise as an alternative approach for treating smartphone addiction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of random controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(20), 3912 (2019).

Navarro-Lopez, S., Moya-Ramón, M., Gallar, J., Carracedo, G. & Aracil-Marco, A. Effects of physical activity/exercise on tear film characteristics and dry eye associated symptoms: A literature review. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 46(4), 101854 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B has been involved in the conception and design of the study, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript drafting; S.A has contributed to the conception and design of the study, and acquisition of data; B.Z has contributed to the conception and design of the study, and the acquisition of data, has been involved in revising the manuscript critically, and has given the final approval for the paper to be published. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bouazza, S., Abbouyi, S. & Zarrouq, B. Moderated mediation model of the association between problematic smartphone use and dry eye disease within Moroccan adolescents. Sci Rep 15, 25334 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11060-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11060-4