Abstract

Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) is a high-value medicinal crop; its slow soil-based cultivation limits yield and risks root loss or contamination. We evaluated how nitrogen form [nitrate (NO3⁻), ammonium (NH4⁺), and ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3)] affects licorice physiology in four culture systems: aeroponic, nutrient film technique (NFT), substrate hydroponics (cocopeat: perlite 1:1), and soil. Seedlings (21 days old, 10 cm tall) were transferred into each system in a completely randomized design with three replications and fertigated with modified Hoagland solution (10 mM total N) from day 80 to harvest at day 120. We measured root and shoot Fe, Mn, Zn, and Cu by atomic absorption spectroscopy; chlorophyll fluorescence indices (F0, Fm, Fv, Fv/Fm, PIaβs, PItot) using a Pocket PEA fluorimeter; and superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activities spectrophotometrically. Across all systems, NH4NO3-fed plants showed the highest root and shoot micronutrient concentrations, maximal PSII photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm), and performance indices (PIaβs, PItot). Sole NH₄⁺ reduced chlorophyll fluorescence parameters but induced the greatest SOD and CAT activities, indicating oxidative stress. NO₃⁻ alone produced intermediate responses, while differences between NH₄NO₃ and NO3- were modest, suggesting that mixed nutrition stabilizes pH and energy balance during assimilation.

Our findings support the hypothesis that balanced NH₄⁺:NO₃⁻ nutrition enhances photosynthetic efficiency, micronutrient uptake, and antioxidant capacity in licorice irrespective of the cultivation system. Implementing combined N fertilization in soilless and soil systems can accelerate licorice production and improve root quality for pharmaceutical use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many medicinal plants, such as licorice, are root products that typically require three to six years to reach maturity. Harvesting them from the soil involves considerable labor and energy costs, and often leads to the loss of secondary roots, resulting in reduced product yield. Furthermore, these plants are vulnerable to contamination by microorganisms or accidental mixing with the roots of weeds. Soilless cultivation systems, particularly hydroponic systems, address many of these limitations. In such systems, the absence of soil or a growing medium enables easy root access, creating a controlled environment that optimizes key factors like temperature, pH, nutrients, moisture, and oxygen availability. As a result, plant growth and maturation can be accelerated1. Studies on the hydroponic cultivation of saffron have demonstrated significant advantages over traditional field cultivation, including enhanced growth rates, shortened time to maturity, increased yield, improved plant biomass, stable secondary metabolite production, and contamination-free products2. Similarly, hydroponic cultivation of medicinal plants such as ginger, aloe vera, senna, and basil has resulted in increased yields compared to soil-based cultivation3. For example, the chlorogenic acid production in hydroponically-grown aloe vera after six months was equivalent to that of two-year-old plants in soil conditions3. Additionally, licorice plants grown in the Deep Flow Technique (DFT) hydroponic system produced active compounds within the first six months of growth, while under conventional field conditions, active compound production typically occurs in the third and fourth years4. Ritter et al.5 found that potato plants grown in aeroponic conditions performed better than those in hydroponic systems, attributing this to superior aeration and enhanced root activity in aeroponics.

Nitrogen (N) is a critical nutrient for plants, and they absorb it primarily as nitrate (NO₃⁻) and ammonium (NH₄⁺) from the nutrient solution6. Among these, nitrate is generally the preferred form of N, constituting approximately 70% of the nitrogen absorbed by plants. The combined application of nitrate and ammonium has been shown to benefit plant growth and yield, with the optimal effects depending on plant species, growth stage, and the ratio of ammonium to nitrate7. For example, optimal tomato growth occurs at a nitrate-to-ammonium ratio of 3:1, while excessive ammonium concentrations can inhibit growth or even halt it completely8. The simultaneous use of both nitrate and ammonium helps conserve energy, minimizes pH fluctuations, and supports ATP production. Nitrate assimilation is energy-intensive, requiring substantial respiration and phosphorylation, while ammonium, being a reduced form of nitrogen, requires less energy for utilization. In hydroponic systems, the oxidation of ammonium is less frequent compared to soil conditions, and a high ammonium-to-nitrate ratio can lead to acidification of the root environment, resulting in cation efflux and growth inhibition9. High ammonium concentrations can impair the plant’s ability to reduce ammonium, disrupt pH balance, and directly exert toxic effects, affecting mineral uptake and depleting carbohydrates10. Research shows that an ammonium-to-nitrate ratio of 3:1 typically optimizes growth and yield parameters12. Nitrate and ammonium are metabolized differently in plants: nitrate is converted into amino acids in the shoot, while ammonium is converted into amino acids in the root and then transported to the shoot, leading to higher nitrate concentrations in the shoot compared to the root13. Excessive ammonium inhibits growth and reduces the root-to-shoot ratio, with only a few plants able to store ammonium without toxicity15.

Nutritionally, nitrogen also impacts photosynthesis directly. The nitrogen content in leaves is positively correlated with chlorophyll levels, and increased nitrogen leads to enhanced chloroplast activity and higher photosynthetic rates23. Approximately 55% of plant nitrogen is allocated to photosynthetic structures, ensuring consistent photosynthetic activity24. Nitrogen enhances photosynthesis by boosting Rubisco enzyme activity, and it also indirectly increases photosynthesis by improving transpiration and stomatal conductance25. Additionally, nitrogen influences electron transfer indices, quantum efficiency, and photosynthetic efficiency. Studies on tomato plants under saline stress conditions showed improved electron transfer and photosynthetic efficiency with nitrogen application26. The ratio of ammonium to nitrate also affects photosynthesis, with ammonium alone resulting in reduced photosynthetic rates. In contrast, a 25:75 ammonium-to-nitrate ratio enhanced photosynthetic efficiency in strawberry plants27, and similar results were observed for tomato plants19. Studies on Chinese cabbage further confirm that nitrate-to-ammonium ratios influence chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthetic indices, with a mixed application enhancing these indices28.

Nitrogen also plays a role in root growth and nutrient uptake. Higher nitrogen availability promotes root growth, which enhances nutrient absorption. In Arabidopsis, nitrogen increases auxin and cytokinin levels, driving root growth and improving nutrient uptake29, 30. The form of nitrogen supplied whether nitrate, ammonium, or a combination affects nutrient uptake. High ammonium concentrations, for instance, disrupt K⁺ transport channels, alter root pH, and impair nutrient uptake, while high nitrate concentrations may also affect nutrient uptake patterns, such as phosphorus levels31,32.

Ammonium-induced oxidative stress is a key factor in N metabolism. As ammonium is metabolized, reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide ions are produced, leading to oxidative stress in plant cells33. In response, plants activate antioxidant defenses, including enzymes such as catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and peroxidase (POD), to neutralize free radicals and mitigate cellular damage34. The oxidative stress caused by ammonium metabolism can act as a signal to upregulate these antioxidant pathways, which help manage ROS accumulation. This process is linked to redox imbalance and the production of reactive oxygen species, which can affect hormonal pathways, including the cross-talk between abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene, both of which are involved in stress responses and redox regulation34,35. Studies on plants like maize and safflower have shown that high ammonium concentrations lead to increased free radical production, which, in turn, stimulates antioxidant enzyme activity35,36. Similarly, in plants such as spinach, soybean, and chamomile, high ammonium concentrations have been associated with enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity, suggesting that ammonium-induced oxidative stress triggers a protective response in plants37,38.

Given the importance of licorice as a medicinal plant in the pharmaceutical industry and the threat of over-harvesting leading to its extinction, cultivating licorice in diverse systems, both soil and soilless, is crucial for its sustainable production. However, there have been limited studies on the nitrogen nutrition of licorice in different cultivation systems. This study aims to fill this gap by examining how different nitrogen sources, nitrate, ammonium, and their combination, affect the physiological and biochemical characteristics of licorice under soil and soilless conditions.

We hypothesize that the form and ratio of nitrogen supplied, specifically nitrate, ammonium, and their combination, will differentially affect licorice’s physiological responses, including photosynthetic efficiency, antioxidant enzyme activity, and micronutrient uptake. We expect that mixed ammonium-nitrate nutrition will enhance photosynthesis and micronutrient acquisition more than nitrate or ammonium alone, due to improved root-zone pH buffering and reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) stress. We further hypothesize that ammonium-induced ROS stress will activate antioxidant pathways, particularly through upregulation of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, and peroxidase, to mitigate oxidative damage. Additionally, we anticipate that these responses will vary between soil and soilless cultivation systems, given their distinct root environments and nutrient availability.

The primary objective of this study is to assess the impact of ammonium and nitrate nitrogen on licorice’s physiological characteristics in both soil and soilless culture systems. This will include examining the effects on photosynthetic efficiency, antioxidant enzyme activity, and micronutrient concentrations, offering insights into how different nitrogen sources influence licorice growth and metabolism.

Materials and methods

Location of the experiment and plant material.

This research was conducted in the greenhouse facilities of the Faculty of Agriculture at Vali-e-Asr University of Rafsanjan, Iran. Licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) seeds were sourced from the Genetic and Biological Resources Center of Iran and originally collected from the Nishabur region in Khorasan province, Iran. To overcome seed dormancy caused by the hard seed coat, seeds were scarified by immersion in 98% sulfuric acid for 10 min. Following acid treatment, seeds were thoroughly rinsed multiple times with distilled water to remove any residual acid (Fig. 1).

Scarified seeds were then sown into seedling trays filled with a sterile growing medium composed of cocopeat and perlite mixed in a 1:1 volumetric ratio. These trays were placed in the greenhouse under natural lighting conditions, where the temperature was maintained at 24 ± 3 °C during the day and 21 ± 3 °C at night. The average relative humidity was held at 54 ± 5%. Seedlings were grown for 21 days until reaching a height of approximately 10 cm, at which point they were considered uniform and suitable for transplanting.

Experimental design and nitrogen treatments.

The experiment followed a completely randomized factorial design with three replications per treatment. The two factors studied were the nitrogen source and cultivation system:

-

Nitrogen sources: Calcium nitrate (Ca(NO₃)₂) and ammonium sulfate ((NH₄)₂SO₄), each supplied at a concentration of 10 mM total nitrogen.

-

Cultivation systems: Aeroponic, nutrient film technique (NFT), substrate-based hydroponics, and soil culture.

Seedlings were transferred into the designated culture systems after 21 days of germination. Nutrient solutions were prepared based on a modified Hoagland formula (Table 1), adjusted to deliver 10 mM total nitrogen at a pH of 6.0 ± 0.1. The plants were fertigated with this nutrient solution continuously or at scheduled intervals depending on the system (described below). Nitrogen treatments began on day 80 after transplanting and continued until harvest on day 120, allowing sufficient time for the plants to respond to the different nitrogen sources under each cultivation method.

Culture systems and operational details.

Aeroponic system

The aeroponic setup consisted of three 100-liter capacity reservoirs constructed from UV-sterilized PVC to prevent microbial contamination. Nutrient solution was pumped from each reservoir using a 0.37 kW (approximately 0.5 hp) centrifugal pump capable of delivering 10 L per minute. The solution was then directed through four brass mist nozzles with 0.5 mm diameter orifices spaced evenly at 30 cm intervals to generate a fine nutrient mist that enveloped the plant roots suspended below.

Plants were supported on polyurethane foam boards featuring square cutouts spaced at 10 × 10 cm to hold individual plants securely above the nutrient mist. The irrigation cycle was controlled by an automated timer set to spray nutrient solution for 15 s every 15 min, operating continuously 24 h per day to ensure optimal root hydration and nutrient availability. Excess nutrient solution was drained by gravity back into the reservoir, where it was continuously recirculated. A UV sterilization lamp installed within the reservoir helped minimize microbial growth and maintain solution quality throughout the experiment (Fig. 2).

Nutrient film technique (NFT) system

The Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) system used for licorice cultivation consisted of three independent units, each comprising two parallel PVC channels. Each channel measured 2 m in length and 75 mm in diameter. The channels were installed with a gentle slope of 1.5% to promote gravity-driven flow of the nutrient solution from the upper end toward the lower end, facilitating continuous circulation.

Along each channel, eight planting holes were spaced evenly at 20 cm intervals. Licorice seedlings were supported in these holes using net cups, which held the plants securely and allowed their roots to be suspended directly in the flowing nutrient film. The net cups were fitted into cutouts on the channel lids, ensuring stability while maximizing root exposure to the nutrient solution.

Each NFT unit was connected to a 50-liter reservoir that stored the nutrient solution. Inside the reservoir, a floating submersible pump was installed, which delivered the nutrient solution through two flexible hoses of 1 cm diameter. These hoses directed the solution to the upper end of each channel, where the solution entered and flowed as a thin film over the roots of the plants. After passing through the length of the channel, the solution was drained by gravity back into the reservoir. The flow rate was carefully maintained at approximately 3 L per minute to ensure continuous nutrient supply and oxygenation of the root zone.

The nutrient solution used was a modified Hoagland solution with a total nitrogen concentration of 10 mM, containing varying nitrogen source ratios (nitrate, ammonium nitrate, and ammonium) depending on treatment (Table 1). The nutrient solution was recirculated continuously in this closed system to maximize resource use efficiency and reduce contamination risk.

Substrate hydroponics and soil culture

Substrate culture was conducted using 4-liter plastic pots filled with a mixture of cocopeat and perlite in equal volume ratios (1:1 v/v). This substrate provided a well-aerated, moisture-retentive medium for root growth. Fertigation was carried out every 48 h by delivering 100 mL of the same modified Hoagland nutrient solution through a drip emitter system to each pot.

For soil culture, 4-liter pots were filled with field-collected loamy soil characterized in Table 2. This soil was treated with nitrogen forms identical to those used in hydroponic systems and irrigated with the same fertigation regime (100 mL per pot every 48 h) to maintain consistency across systems for comparative purposes.

Environmental conditions and growth timeline

All culture systems were placed within the same greenhouse bench to ensure uniform environmental conditions. A 16-hour photoperiod was maintained using a combination of natural daylight and supplemental LED lighting, providing a photosynthetic photon flux density of approximately 250 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ at canopy level. Temperature was controlled to remain within 24 ± 3 °C during the day and 21 ± 3 °C at night. Relative humidity was maintained at 54 ± 5%.

Seedlings were grown under these conditions for a total of 120 days. After initial establishment and growth, nitrogen treatments were initiated on day 80 post-transplant and maintained until the final harvest on day 120. At harvest, plants were sampled to evaluate morphological, physiological, and biochemical traits related to nitrogen nutrition and cultivation methods.

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

These traits include indicators related to chlorophyll fluorescence and quantum yield, as measured and calculated based on Table 3. For the measurement of these parameters, a Pocket PEA chlorophyll fluorimeter (PEA, Hansatech Inc. Co., UK) was used. To conduct the measurements, fully expanded leaves were collected from each plant. Special tags were affixed to the upper leaf blades to ensure consistent positioning and to facilitate a dark adaptation period of 15 min before taking the measurements. Following the dark adaptation, a sensor cup was carefully placed on the leaf surface for the measurement process. Chlorophyll fluorescence transients were induced by exposing the leaves to red light with an intensity of up to 3,500 µmol (photon) m–2 s–1. The fluorescence signals were recorded within a time range of 10 µs to 1 s, with the peak wavelength set at 627 nm. These measurements provide valuable information about the dynamic response of the photosynthetic system to light stimuli and help assess the overall photosynthetic performance of the plants. The fluorescence transients were analyzed according to the equations of the JIP test39.

Enzyme activity

Preparation of extract

0.5 g of leaf and root tissue of the plant was thoroughly ground in an ice-cold environment, in a mortar containing 5 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) with 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and 1 mM EDTA. The resulting mixture was immediately transferred to 2 ml microtubes and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was separated to assess the level of enzymatic changes and stored at -20 °C in a freezer until the experiment was conducted.

Measurement of catalase enzyme (CAT) activity (EC 1.11.1.6)

The activity of the catalase enzyme was assessed by measuring the decrease in hydrogen peroxide concentration at a wavelength of 240 nm. The reaction mixture consisted of a 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7) and 15 mM hydrogen peroxide. The reaction was initiated by adding 100 µL of enzyme extract to a final volume of 3 ml. Changes in absorbance at 240 nm were recorded for 3 min. Then, the enzyme activity was calculated using the molar extinction coefficient of hydrogen peroxide (39.4 mM− 1cm− 1) and the formula A = εbc. The enzyme activity was expressed as units of enzyme per total protein amount (µmol H2O2 min− 1 mg− 1 protein)41.

Measurement of superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme activity.

Measurement of superoxide dismutase enzyme activity was carried out in a reaction mixture of 3 ml containing the following components: sodium carbonate (0.1 ml) + methionine (0.2 ml) + NBT (0.1 ml) + potassium phosphate buffer (1.5 ml) + distilled water (1 ml) + 50 µL of enzyme extract, and the reaction was initiated by adding 0.1 ml of riboflavin solution to the reaction mixture. The test tubes were then placed under direct light for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by placing the tubes in darkness. The absorbance at 560 nanometers wavelength was measured. The reaction mixture that did not show any color was considered blank. The activity of the superoxide dismutase enzyme was calculated based on enzyme units per ml of protein for all samples. One unit of enzyme activity is equal to the amount of enzyme that causes a 50% reduction in absorbance of the reaction compared to the control (without enzyme)42. The enzyme activity was calculated based on the following formula.

One unit of enzyme activity is equal to 50% of the inhibition of NBT, which is calculated from the following formula:

One unit of enzyme activity (50% inhibition) = X / (1/5).

Micronutrients

0.5 g of dried and ground samples (shoot and roots) were weighed and then placed in an oven at a temperature of 250 ◦C for 30 min, followed by being placed at a temperature of 550 ◦C for 3 h to transform the samples into ash. Then, 5 ml of 2 N hydrochloric acid was added to each sample and finally brought to a volume of 50 ml with distilled water. This extract was used directly for the measurement of Fe, Mn, Zn, and Cu elements using an Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (GBC AVANTA-PM model, made in Australia).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed as a two-factor factorial experiment arranged in a completely randomized design (CRD) with three replications. The two fixed factors were the nitrogen source (nitrate, ammonium nitrate, and ammonium) and cultivation system (aeroponic, NFT, inert substrate, and soil). Before conducting inferential analyses, data were examined for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and for homogeneity of variances via Levene’s test. Where necessary, appropriate transformations (log or square root) were applied to meet ANOVA assumptions. A two-way ANOVA was then performed to assess the main and interactive effects of the N source and cultivation system on each response variable, including micronutrient concentrations, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, and antioxidant enzyme activities. Significance was determined at the 0.05 probability level.

Post hoc comparisons of treatment means were made using Duncan’s multiple range test at p ≤ 0.05. All results are reported as mean ± standard error. In addition to univariate analysis, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to explore relationships among physiological traits, enzyme activities, and micronutrient contents. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on standardized data to visualize multivariate patterns and treatment clustering. All statistical analyses were carried out in R version 4.3.1 using the stats, agricolae, and FactoMineR packages, while graphical illustrations were generated using ggplot2 and GraphPad Prism.

Results

Iron in roots and shoots

The findings indicated that plants fertigated with ammonium nitrate consistently exhibited the highest concentration of Fe in their roots across all cultivation systems. Conversely, when plants were fertigated solely with ammonium or nitrate, the Fe concentration in the roots was found to decrease. The concentration of Fe in the roots of plants fertigated with ammonium source in the aeroponic, NFT, neutral substrate, and soil substrate decreased by approximately 28%, 20%, 20%, and 8% respectively compared to the ammonium nitrate treatment. The results also showed that fertigating plants with nitrate compared to ammonium nitrate in the aeroponic, NFT, neutral substrate, and soil substrate resulted in a 13%, 10%, 13%, and 10% reduction in root Fe concentration, respectively (Table 4). The results regarding the shoots’ Fe concentration also indicated that the highest concentration of Fe in the shoot was observed in plants fertigated with ammonium nitrate. Fertigating licorice plants with only ammonium or nitrate resulted in a decrease in the Fe concentration in the shoots across all cultivation systems. However, the plants exhibited distinct responses to these two nitrogen sources. Fertigating plants with the ammonium source led to a decrease of 24%, 16%, 20%, and 6% in the Fe concentration of the shoots in the aeroponic, NFT, neutral substrate, and soil substrate systems, respectively, compared to fertigating with ammonium nitrate.

Fertigating plants with nitrate also led to a 6%, 7%, and 9% decrease in shoots’ Fe concentration in the aeroponic, NFT, and soil substrate compared to plants treated with ammonium nitrate, while no significant difference in shoots’ Fe concentration was observed in the neutral substrate system (Table 4).

Manganese in roots and shoots

The results showed that the application of ammonium along with nitrate led to an increase of 17%, 22%, 14%, and 13% in Mn concentration in the roots of licorice plants in the aeroponic, NFT, neutral substrate, and soil substrate compared to the application of sole nitrate. The results also indicated that the application of ammonium alone resulted in a decrease of 32%, 24%, and 23% in root Mn concentration compared to ammonium nitrate in the aeroponic, NFT, and neutral substrate, respectively. Furthermore, the application of ammonium alone in the aeroponic, NFT, and neutral substrate respectively caused a reduction of 20%, 8%, and 13% in Mn concentration compared to the use of nitrate. While no significant difference in root Mn concentration was observed between plants treated with ammonium and ammonium nitrate in the soil substrate. The application of ammonium alone led to a 9% increase in root Mn concentration compared to plants treated with nitrate in the soil substrate (Table 4).

The results (Table 4) also showed that the application of ammonium along with nitrate resulted in an increase of 23.6%, 12%, and 10% in Mn concentration in the roots of licorice plants in the aeroponic, NFT, and neutral substrate, respectively. The results also indicated that the application of ammonium led to a decrease of 11%, 15%, and 13% in shoot Mn concentration compared to the application of ammonium nitrate in the aeroponic, NFT, and neutral substrate, respectively. The application of ammonium also resulted in a 6% decrease in shoot Mn concentration in the aeroponic compared to nitrate treatment, while no significant difference was observed between plants treated with ammonium and nitrate sources in terms of shoot Mn concentration in the NFT and neutral substrate systems. The results also showed that the shoot Mn concentration in the soil substrate was not affected by the N source (Table 4).

Th results showed that the simultaneous application of nitrate and ammonium led to an increase of 9%, 9%, and 14% in root Zn concentration compared to the application of nitrate in the aeroponic, NFT, and soil substrate. No significant difference in root Zn concentration was observed between plants treated with ammonium nitrate and nitrate in the neutral substrate system. Additionally, the application of ammonium resulted in a 40%, 34%, and 21% decrease in root Zn concentration compared to the application of ammonium nitrate in the aeroponic, NFT, and neutral substrate, respectively, while no significant difference in root Zn concentration was observed between these two N sources in soil cultivation conditions. The root Zn concentration decreased by approximately 33%, 27%, and 18% in the aeroponic, NFT, and neutral substrate when using ammonium compared to nitrate, while an increase of 12% in root Zn concentration was observed in soil cultivation conditions (Table 4). Shoot Zn concentration also showed no significant difference between plants treated with ammonium nitrate and nitrate, but the application of ammonium resulted in a 27%, 20%, and 11% decrease in shoot Zn concentration in the aeroponic, NFT, and soil cultivation, respectively (Table 4).

Copper in roots and shoot.

The effect of cultivation system, N source, and their interaction on Cu concentration in roots and shoots did not show a statistically significant difference at the 5% probability level.

Chlorophyll fluorescence indices

Chlorophyll fluorescence is a very small portion of the energy wasted from the photosynthetic system39. It has been determined that chlorophyll fluorescence occurs in the spectrum of light between 740 –680 nm and specifically in Photosystem II39. Therefore, chlorophyll fluorescence can provide very useful insights into the structure and function of the highly complex Photosystem II. The Fo index indicates the minimum chlorophyll fluorescence when all reaction centers are open and ready to receive electrons, and under stress conditions, this index increases due to damage to the reaction center. Minimum fluorescence is one of the fundamental indices for measuring chlorophyll fluorescence indices, which can influence all chlorophyll fluorescence indices. As shown in Table 5, the Fo, Fo/Fv, and Vi indices increased with an increase in the amount of ammonium in the nutrient solution, and the increase was greater in plants grown in NFT and aeroponic, but was lower in the soil cultivation system. The results also indicated that there was no significant difference in these indices between plants fed with nitrate and ammonium nitrate (Table 5).

The results also showed that the Fm, Fv/Fm, Fv, and area indices decreased in all cultivation systems when using ammonium. There was no significant difference between plants fed with ammonium nitrate and nitrate in each of the cultivation systems. When using ammonium compared to ammonium nitrate, the Fm index in the leaves of licorice plants decreased by approximately 13%, 17%, 10%, and 10% in aeroponic, NFT, neutral substrate, and soil substrate systems, respectively (Table 5).

Indices of quantum efficiency and energy transfer between Photosystem II and I

The results showed that the Sm index in the leaves of licorice plants increased with an increase in the amount of ammonium in the nutrient solution. The highest value of this index was observed in plants fed with ammonium in such a way that the Sm index in plants fed with ammonium was approximately 12% and 10% higher compared to plants fed with nitrate and ammonium nitrate, respectively (Table 6). The results also showed that Φdo (quantum efficiency of energy dissipation) was higher in plants fed with ammonium in all cultivation systems, although the response of plants to ammonium nutrition varied based on the cultivation system. The Φdo index for plants fed with ammonium in hydroponic, NFT, neutral substrate, and soil substrate systems decreased by approximately 33%, 40%, 25%, and 19%, respectively, while no significant difference was observed in terms of the Φdo index between plants treated with nitrate and ammonium nitrate (Table 6).

As shown in Table 6, the indices φET20 (Quantum yield of electron transport from QA to QB in PSII) and Φre10 (Quantum yield of reduction of end electron acceptors at the PSI acceptor side) decreased by approximately 8% and 50%, respectively, under conditions of ammonium nutrition compared to conditions of ammonium nitrate nutrition, while feeding with only ammonium resulted in decreases of approximately 8% and 56% in φET20 and Φre10 indices compared to nitrate nutrition. According to the results (Table 6), the PIabs index (photosynthetic chemical efficiency index) in the leaves decreased by approximately 24%, 32%, 43%, and 26% under conditions of ammonium application compared to ammonium nitrate nutrition in the aeroponic, NFT, neutral substrate, and soil substrate systems, respectively. The results also indicated that the PIabs index in the leaves of licorice plants grown in neutral and soil substrates with nitrate source decreased by approximately 38% and 30%, respectively, compared to plants fed with nitrate ammonium. The results related to the PItot index (total photosynthetic chemical efficiency index before the reaction center one) also showed decreases of approximately 47%, 64%, 56%, and 42% under conditions of ammonium nutrition compared to ammonium nitrate nutrition in the aeroponic, NFT, neutral substrate, and soil substrate systems, respectively. The PItot index in the leaves of licorice plants grown in neutral and soil substrates with nitrate source decreased by approximately 35% and 32%, respectively, compared to plants fed with ammonium nitrate. The results showed that N sources did not have an effect on the Tr0/rc and Et0/rc indices in the hydroponic and NFT systems, but in the neutral substrate and soil substrate systems, the use of nitrate and ammonium alone resulted in a decrease in the Tr0/rc and Et0/rc indices in leaves compared to the ammonium nitrate treatment (Table 6).

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme activity in roots and leaves.

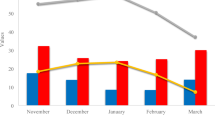

The results showed that the highest SOD enzyme activity in the roots and leaves of licorice plants was observed under conditions of ammonium nutrition in each of the cultivation systems. However, the response of plants to the source of ammonium in terms of SOD enzyme activity in roots and leaves varied across different systems. The SOD enzyme activity in the roots of plants fed with ammonium increased by approximately 76%, 116%, 111%, and 72% compared to plants treated with ammonium nitrate source in the aeroponic, NFT, neutral substrate, and soil substrate cultivation systems, respectively (Fig. 3). Similarly, the SOD enzyme activity in the leaves under conditions of ammonium nutrition in the aeroponic, NFT, neutral substrate, and soil substrate systems increased by approximately 113%, 88%, 86%, and 100% compared to conditions of ammonium nitrate nutrition (Fig. 4). The results also indicate that feeding plants with nitrate source in the NFT cultivation system led to a 19% increase in SOD enzyme activity in roots, while no significant difference in terms of SOD enzyme activity in roots was observed between plants fed with nitrate and ammonium nitrate sources in the hydroponic, neutral substrate, and soil substrate cultivation systems (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 4, no significant difference in SOD enzyme activity of leaf was observed between plants fed with nitrate and nitrate ammonium sources.

The effect of different N sources on the activity of the superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme in the roots of licorice in various cultivation systems. Means sharing a common letter are not significantly different by Duncan’s multiple range test at p ≤ 0.05. Vertical bars indicate ± standard error of the mean (n = 3 independent replicates).

The effect of different N sources on the activity of the superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme in the leaves of licorice in various cultivation systems. Means sharing a common letter are not significantly different by Duncan’s multiple range test at p ≤ 0.05. Vertical bars indicate ± standard error of the mean (n = 3 independent replicates).

Catalase enzyme activity in roots and leaves

The results showed that the catalase enzyme activity in the leaves was higher than in the roots, and plants fed with an ammonium source had higher catalase enzyme activity in roots and leaves compared to plants fed with nitrate and ammonium nitrate sources (Figs. 5 and 6).

Discussion

Micronutrients

Micronutrients play complex roles in the physiology of plants. Although micronutrients are required in very small amounts by plants, they are more involved in enzymatic reactions within the plant and are considered essential components of photosynthetic enzymes that are effective in energy transfer in plant cells and the synthesis of essential compounds43. Manganese and Cu constitute the metallic part of the superoxide dismutase enzymes. Under conditions of Cu and Mn deficiency, the intensity of photosynthesis and the amount of plant carbohydrates decrease44. Additionally, among micronutrients, Zn plays an important role in RNA metabolism and the content of ribosomes in plant cells. Zinc, through stimulating the metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins, and DNA, can play a significant role in many biochemical and physiological processes45.

The results of the present study showed that the application of ammonium along with nitrate increased the concentration of Fe, Mn, and Zn in the roots and shoot of the plant, but applying ammonium and nitrate alone led to a decrease in the concentration of Fe, Mn, and Zn. The decrease in the levels of micronutrients, except for Cu, is likely due to a reduction in root growth. Additionally, the concentration of Fe, Mn, and Zn in soil-grown plants fertigated with nitrate was lower compared to plants fertigated with ammonium, due to the effect of ammonium on soil pH (acidification of soil) and increased solubility and absorption of these elements6. In a study on two Azalea cultivars, the application of ammonium sources resulted in increased levels of Fe, Zn, Mn, and P compared to the use of nitrate, through pH reduction in the root environment46. Furthermore, investigations conducted on lilies in hydroponic conditions showed that the application of different ratios of ammonium to nitrate caused changes in the concentrations of Fe, Zn, and Mn in roots, shoots, and leaves. More specifically, as the ammonium concentration increased, the Fe concentration in the roots initially rose and then declined at higher concentrations. In contrast, the Fe concentration in the leaves and shoots increased consistently with the rising ammonium levels. The application of ammonium also led to an increase in the concentration of Mn and Zn in the leaves, roots, and shoots of Iris germanica47. The increase in Mn, Zn, and Fe concentrations in high ratios of ammonium to nitrate is due to lower rhizosphere pH, increased solubility of these elements in the root environment, and consequently increased uptake of these elements44. Additionally, the current research results indicated that the concentrations of Fe, Zn, and Mn in the roots and shoots of licorice plants grown in hydroponic systems were higher compared to plants grown in soil. This difference may be due to greater availability of nutrients, better nutrient balance, and direct root contact with nutrients44. On the other hand, in hydroponic systems, due to better aeration, root activity is higher, resulting in increased nutrient absorption. However, in ammonium nutrition conditions, due to the high amount of ammonium in the root environment, root tissues are damaged in comparison to soil cultivation, leading to reduced nutrient uptake6. A study on potato plants regarding the impact of the cultivation system on leaf nutrient concentrations of Fe, Zn, and Mn showed that plants grown in aeroponic systems had higher nutrient levels compared to those grown in neutral media due to better aeration and increased root activity48, which is in line with the results of the current study, indicating that the variance in nutrient concentrations in plant tissues under different systems depends on the nutrient content of the surrounding environment, oxygen availability around the roots, and the level of root activity.

Chlorophyll fluorescence

Chlorophyll fluorescence can be considered as the red to far-red light emitted from the photosynthetic tissue during light illumination in the range of 400 to 700 nm. In this light spectrum, blue and red light are more efficient than green light. Although chlorophyll fluorescence represents a small fraction of the absorbed energy (about 0.05–0.1%), the intensity of chlorophyll fluorescence inversely indicates the amount of energy used for photosynthesis49. When the absorbed light energy by the leaf exceeds the photosynthetic capacity, the excess energy is reflected through chlorophyll fluorescence50. Therefore, chlorophyll fluorescence can be used as a phenomenon to control and evaluate the efficiency of Photosystem II50. It can be said that chlorophyll fluorescence is one of the pathways of excitation energy consumption in photosynthesis, widely used in photosynthesis research for determining the physiological status of plants and assessing the damage to the photosynthetic apparatus51. Generally, during the process of light reaction in photosynthesis, light energy is received by chlorophyll molecules and transferred to the reaction center where the water molecule is split in Photosystem II by the transferred energy. After hydrolysis of the water molecule, electrons are transferred to the reaction center I and ferredoxin through receptors and electron carriers, ultimately leading to the production of NADPH52. Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters are used as reliable, non-destructive, powerful, and simple tools for evaluating the electron transport in photosynthesis53. One important parameter of chlorophyll fluorescence is the variable-to-maximum fluorescence ratio (Fv/Fm). The ratio Fv/Fm indicates the maximum quantum yield efficiency of Photosystem II for converting the absorbed light energy into chemical energy54. However, it has been reported that this parameter is non-specific55 and often not sensitive50. Therefore, for a more accurate evaluation of the photosynthetic apparatus, more non-destructive evaluations of the entire photosynthetic apparatus are required50. In this method, after a dark period, chlorophyll fluorescence is recorded alternately (once per second). Changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters provide valuable information about the photosynthetic quantum efficiency, functional characteristics, and electron transport components involved in the photosynthetic electron transfer56. After this dark period, the plastoquinone capacity (as an electron acceptor) increases, showing that all reaction centers are open. The openness of reaction centers indicates readiness for biochemical processes (Fo). The maximum fluorescence (Fm) is also dependent on the plastoquinone capacity, and when fluorescence reaches its maximum, indicating that the plastoquinone capacity is full, the reaction centers are closed57. Therefore, under stress conditions, the disruption of reaction centers or a decrease in the plastoquinone capacity is the main factor in reducing chlorophyll fluorescence parameters57. A rapid increase in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters from the O-J-I-P stages requires a high plastoquinone capacity; otherwise, Fm decreases, and consequently, the area index decreases. Ultimately, other chlorophyll fluorescence parameters are affected57,58. It has been reported that nitrogen affects the light energy absorption and utilization by the leaf. An increase in leaf chlorophyll content in response to N supply leads to increased absorption of light energy by chlorophyll molecules, resulting in a decrease in the accumulation of absorbed light energy. However, if the excess energy absorbed does not effectively decrease, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced, indicating serious damage to the photosynthetic apparatus and causing oxidative damage to chloroplasts. Furthermore, sufficient N in leaf tissue, besides increasing the chlorophyll content by improving the plant’s water relations, helps preserve the photosynthetic pigments involved in light energy absorption, ultimately leading to a decrease in chlorophyll fluorescence54. Additionally, N application, by increasing transpiration, reduces leaf temperature and prevents the destructive effects of high temperatures and damage to the photosynthetic apparatus25. The results of the present study showed that Fo, Fo/Fv, and Vi indices decreased under ammonium nutrition conditions compared to nitrate and ammonium nitrate nutrition conditions. Numerous studies have investigated the impact of nitrogen forms and varying NH4+:NO3− ratios on photosynthesis. NH4+ has been identified as having the ability to disrupt the electron transport chain, a critical component of photosynthesis. This disruption is closely linked to the key photosynthetic parameter, Fv/Fm. The Fv/Fm ratio is a key parameter that indicates the maximum efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) photochemistry, reflecting the optimal functioning of PSII when all PSII centers are open and the QA (primary electron acceptor) is oxidized59. A decline in this ratio serves as a sensitive indicator of photo-inhibitory damage caused by the incident photon flux density, especially under various environmental stresses that plants may encounter60. Ammonium nutrition can impact the Fv/Fm in plants by influencing various physiological and biochemical processes. High levels of ammonium can lead to nitrogen toxicity, which may disrupt the balance of nutrient uptake and affect the efficiency of photosynthesis6. This can result in decreased Fv/Fm values, indicating reduced photosynthetic capacity and potential damage to the photosynthetic machinery. In wheat seedlings, ammonium N sources decreased electron transport efficiency and increased the production of ROS, exacerbating damage to the electron transport chain and leading to a reduced plant photosynthetic capacity61. According to the present study results, there was a positive and significant correlation between chlorophyll concentration and N with the Fv/Fm index. Therefore, the sole application of ammonium leads to a reduction in chlorophyll concentration, resulting in reduced chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. An increase in the Fo index under ammonium nutrition conditions reflects the effect of ammonium on light-receiving proteins, disrupting the transfer of light energy, and leading to less energy consumption for plant biochemical processes. Thus, the application of ammonium through decreased levels of light-receiving proteins reduces the efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus, ultimately increasing Fo54. A study on rice and cucumber plants showed that feeding cucumber plants with an ammonium source led to a reduction in the Fv/Fm index compared to plants fertigated with nitrate, but no significant difference in Fv/Fm was observed between rice plants fertigated with ammonium and nitrate62. An increase in Vj and Vi parameters under ammonium application conditions has also been reported in two algal species, indicating that ammonium changes the chlorophyll amount due to pH alteration in the growth medium and ultimately affects intracellular pH63. Changes in intracellular pH through changes in membrane efficiency and increased pH gradient between different organelles lead to decreased photosynthetic efficiency64. In a study on olive trees by Khaleghi et al.50, it was shown that a linear relationship exists between leaf chlorophyll content and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters.

Quantum efficiency performance indices and energy transfer between photosystem II and I

The results of the present study showed that the application of ammonium alone led to a decrease in quantum efficiency performance indices of the leaf, except for Φdo and Ψo. The application of ammonium as an N source induced stress in licorice plants by reducing N levels and chlorophyll content. Reduction in quantum efficiency performance indices under stress conditions has been reported in sunflower plants65, corn, tomatoes54, barley66, pistachio seedlings67, and lettuce58. They showed that the decrease in quantum efficiency performance indices is due to a reduction in the levels of light-receiving proteins in Photosystem II. Additionally, under stress conditions, a decrease in leaf chlorophyll concentration, along with a decrease in energy transfer and damage to the D1 protein in Photosystem II, results in a decrease in φPo68. The decrease in electron transfer from plastoquinone to plastocyanin is also one of the reasons for the reduction in quantum efficiency performance indices57. Kalaji et al.54 demonstrated that N deficiency leads to a decrease in chlorophyll content and light-receiving proteins, causing a reduction in Photosystem II efficiency and ultimately a decrease in quantum performance. Recent studies have also reported a decreased efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus and quantum performance under N deficiency conditions64. Therefore, based on previous research, it can be concluded that leaf N content plays a crucial role in the efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus and quantum performance by affecting chlorophyll levels. A study on cyanobacteria showed that high concentrations of ammonium led to a decrease in chlorophyll fluorescence indices, Photosystem II efficiency, and quantum performance69. In ammonium nutrition conditions, ammonia accumulates in the intracellular space20. The accumulation of ammonia in the intracellular space, particularly in the lumen, directly disrupts the Mn cluster, impairing Photosystem II efficiency by interfering with the reception of electrons from water molecule splitting. Additionally, once ammonia enters the lumen space, it combines with a proton, leading to an increase in the lumen pH, and disrupting the thylakoid membrane efficiency69. Studies on different ratios of ammonium to nitrate have shown that an increase in the ammonium to nitrate ratio resulted in improved quantum efficiency performance indices of Photosystem II and the amount of energy transferred between Photosystem II and I in sorghum plants. They also demonstrated a positive and significant correlation between N content, chlorophyll, quantum performance, and energy transfer70. Therefore, based on the results of the present study, the reduction in quantum efficiency performance indices under ammonium application conditions can be attributed to decreased N levels and chlorophyll concentration. Consequently, there is a significant positive relationship between N, chlorophyll, and quantum performance and energy transfer indices present. It has been reported that N deficiency leads to a decrease in chlorophyll content, light-receiving proteins, and plastoquinone71. Therefore, given the role of N in quinone synthesis, N deficiency can also affect electron acceptor receptors, thus reducing electron transfer and energy transfer between Photosystem II and I71. Additionally, a significant positive relationship between leaf N content in spinach plants and the content of cytochrome f and electron transfer in the electron transfer chain has been reported72. Thus, the decrease in PIabs and PItot is due to a reduction in electron transfer between Photosystem II and I.

Antioxidant enzymes activity

In optimal plant growth conditions, there is a balance between the production of reactive oxygen species and their consumption. Under normal conditions, the activities of oxidative enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, polyphenol oxidase, peroxidase, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, and the synthesis of antioxidant compounds such as carotenoids and phenolic compounds, along with secondary metabolites, maintain this balance73,85. In plants under stress, this balance is disrupted, leading to increased production of free radicals and oxidative stress74. When a plant is in non-optimal conditions, electrons resulting from water splitting (the Hill reaction) that are transferred from Photosystem II to Photosystem I are diverted from their specific metabolic pathway and, upon reacting with oxygen molecules, generate free radicals. Free radicals such as superoxide (O2-) and hydroxyl radicals (OH.) are the result of such reactions75. When the inhibition of free radicals in plants becomes impossible, lipid and membrane fatty acids peroxidation increases, leading to certain physiological changes in cellular processes and the production of compounds such as malondialdehyde, etc76. Hydrogen peroxide is a toxic product produced in plants under stress conditions, acting as a strong oxidant. The most stable free radical under stress conditions is hydrogen peroxide, capable of quickly penetrating the cell membrane77. Drought stress leads to the production of hydrogen peroxide in cellular structures through lipid peroxidation and damage to protein structures, accelerating leaf aging in plants78.

Plants can withstand damage caused by stress if they enhance their defense capacity. This system includes enzymatic and non-enzymatic detoxification mechanisms79 that reduce or repair damages caused by radicals due to changes in the activity levels of plant defense enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, polyphenol oxidase, peroxidase, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, and other compounds like phenols and secondary metabolites80. Studies suggest that the activity of antioxidant enzymes may reflect oxidative stress in plants, and it is generally hypothesized that antioxidant enzyme activity increases under environmental stress conditions as part of the plant’s protective response81. Superoxide dismutase is the primary scavenger enzyme for free radicals, converting superoxide radicals into hydrogen peroxide, which is a non-radical molecule. The hydrogen peroxide produced is then converted to water and oxygen by the enzyme catalase or ascorbate peroxidase34. Peroxidase enzyme plays a crucial role in scavenging hydrogen peroxide, with the help of ascorbic acid acting as an electron donor to convert hydrogen peroxide to water. During this reaction, ascorbic acid is transformed into monodehydroascorbate. Glutathione peroxidases (POX) are glycoproteins that consume phenols as hydrogen donors and participate in processes such as growth, lignin synthesis, ethylene biosynthesis, defense, and wound healing82,83. The current research results indicate that the activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase increased under ammonium nutrition conditions. Still, there was no significant difference in the activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase between plants fertigated with ammonium nitrate and nitrate. It has been reported that the accumulation of glutamine acts as a signal for the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, and catalase82. Therefore, under ammonium nutrition conditions, the accumulation of glutamine acts as a signal for the activity of these enzymes82. Huang et al.82 demonstrated that excessive ammonium can induce oxidative stress in plant tissues by reducing N levels, potentially leading to increased ROS accumulation. This may, in turn, be associated with the observed rise in antioxidant enzyme activity, suggesting that ROS signaling could be involved in modulating these responses. Additionally, the results of this research show that a decrease in N content in plant tissues leads to increased hydrogen peroxide radical levels and subsequently increased activity of antioxidant enzymes84. Previous studies have indicated that ammonium nutrition may reduce photosynthetic activity, potentially leading to an increase in reactive oxygen species and a corresponding enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activity as a possible defense mechanism against membrane damage. In the present study, since no significant differences were observed in quantum efficiency performance and energy transfer indices between plants fertigated with ammonium nitrate and nitrate, it is hypothesized that changes in these parameters, possibly driven by increased free radicals, could act as signaling factors contributing to the observed increase in antioxidant enzyme activity.

In the present study, since no significant differences were observed in quantum efficiency performance and energy transfer indices between plants fertigated with ammonium nitrate and nitrate, it is hypothesized that changes in these parameters, possibly driven by increased free radicals, could act as signaling factors contributing to the observed increase in antioxidant enzyme activity.

Ammonium assimilation in plant cells can lead to a transient redox imbalance, primarily due to disrupted pH homeostasis in chloroplasts and mitochondria, which promotes electron leakage to O₂ at the Photosystem I acceptor side and generates ROS such as superoxide and hydrogen peroxide33. These ROS are not merely toxic by-products but also function as key secondary messengers in stress signaling. In several plant species including licorice, maize, and cucumber, NH₄⁺-induced ROS accumulation has been shown to activate antioxidant defenses through redox-sensitive transcription factors and MAPK cascades. Elevated glutamine levels under NH₄⁺ nutrition have also been implicated as early metabolic signals that enhance the expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and CAT6,35.

Moreover, ROS signaling under ammonium stress often intersects with phytohormonal pathways to fine-tune the antioxidant response. Increased NH₄⁺ availability stimulates ethylene biosynthesis, which in turn can enhance SOD and CAT gene expression via the EIN3/EIL transcriptional pathway. Concurrently, NH₄⁺ stress frequently elevates abscisic acid (ABA) levels, and ABA regulates antioxidant enzyme expression through ABF/AREB transcription factors. This coordinated ROS, ethylene, and ABA cross-talk play a crucial role in maintaining redox homeostasis and mitigating cellular damage under ammonium-induced oxidative stress17,37,85,86,87.

In the present study, the absence of significant differences in photosystem quantum efficiency and energy transfer indices between plants fertigated with ammonium nitrate and nitrate suggests that ROS signaling, possibly triggered by subtle changes in redox state, might initiate the observed increase in antioxidant enzyme activities.

Conclusion

The results of the present study have shown that physiological indices of licorice plants are influenced by different ratios of ammonium and nitrate, as well as cultivation systems. Application of ammonium and nitrate lonely, decreased leaf micronutrient concentration, chlorophyll fluorescence indices, and quantum yield of PSII photochemistry compared to ammonium nitrate form in all culture systems. The results indicate that the activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase enzymes increased under stress conditions of sole ammonium nutrition. Still, there was no significant difference in the activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase between plants fertigated with ammonium nitrate and nitrate. Therefore, the simultaneous application of ammonium and nitrate can be considered as a suitable N source for licorice plants.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not public.

References

Mirza, N. R. & Stolerman, I. P. Nicotine enhances sustained attention in the rat under specific task conditions. Psychopharmacol. (Berl). 138, 266–274 (1998).

Pagliarulo, C. L., Hayden, A. L. & Giacomelli, G. A. Potential for greenhouse aeroponic cultivation of urtica dioica. Acta Hortic. 659, 61–66 (2004).

Hayden, A. L. Aeroponic and hydroponic systems for medicinal herb, rhizome, and root crops. HortScience 41, 536–538 (2006).

Afreen, F., Zobayed, S. M. A. & Kozai, T. Spectral quality and UV-B stress stimulate glycyrrhizin concentration of Glycyrrhiza uralensis in hydroponic and pot system. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 43, 1074–1081 (2005).

C, E. R. B. A. P. R. Comparison of hydroponic and aeroponic cultivation systems for the production of potato minitubers. Potato Res. 44, 127–135 (2001).

Tavakoli, F., Hajiboland, R. & Nikolic, M. Multiple mechanisms are involved in the alleviation of ammonium toxicity by nitrate in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L). Plant. Soil. 503 (1), 451–473 (2024).

Xiao, C., Fang, Y., Wang, S. & He, K. The alleviation of ammonium toxicity in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 65 (6), 1362–1368 (2023).

Sanchez, E. et al. Phenolic compounds and oxidative metabolism in green bean plants under nitrogen toxicity. Aust J. Plant. Physiol. 27, 973–978 (2000).

Sánchez, E., Rivero, R. M., Ruiz, J. M. & Romero, L. Changes in biomass, enzymatic activity and protein concentration in roots and leaves of green bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L. Cv. Strike) under high NH4NO3 application rates. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 99, 237–248 (2004).

Walch-Liu, P., Neumann, G., Bangerth, F. & Engels, C. Rapid effects of nitrogen form on leaf morphogenesis in tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 51, 227–237 (2000).

Kaya, C. & Shabala, S. Sodium hydrosulfide-mediated upregulation of nitrogen metabolism improves drought stress tolerance in pepper plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 209, 105305 (2023).

Coskun, D., Britto, D. T. & Kronzucker, H. J. Nutrient constraints on terrestrial carbon fixation: the role of nitrogen. J. Plant. Physiol. 203, 95–109 (2016).

Torgny Näsholm, K. & Kielland Ulrika ganeteg. Uptake of organic nitrogen by plants. New. Phytol. 182, 31–48 (2009).

MILLARD P. The accumulation and storage of nitrogen by herbaceous plants. Plant. Cell. Environ. 11, 1–8 (1988).

Shilpha, J., Song, J. & Jeong, B. R. Ammonium phytotoxicity and tolerance: an insight into ammonium nutrition to improve crop productivity. Agronomy 13 (6), 1487 (2023).

Roosta, H. R. & Schjoerring, J. K. Effects of nitrate and potassium on ammonium toxicity in cucumber plants. J. Plant. Nutr. 31, 1270–1283 (2008).

Barker, A. V. & Corey, K. A. Interrelations of ammonium toxicity and ethylene action in tomato. HortScience 26, 177–180 (2019).

Wang, Z., Miao, Y. & Li, S. fang, Effect of ammonium and nitrate nitrogen fertilizers on wheat yield in relation to accumulated nitrate at different depths of soil in drylands of China. F. Crop. Res. 183,211–24. (2015).

Liu, G., Du, Q. & Li, J. Interactive effects of nitrate-ammonium ratios and temperatures on growth, photosynthesis, and nitrogen metabolism of tomato seedlings. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 214, 41–50 (2017).

Esteban, R., Ariz, I., Cruz, C., Moran, J. F. & Review Mechanisms of ammonium toxicity and the quest for tolerance. Plant. Sci. 248, 92–101 (2016).

Bittsánszky, A., Pilinszky, K., Gyulai, G. & Komives, T. Overcoming ammonium toxicity. Plant. Sci. 231, 184–190 (2015).

Bowsher, C., Steer, M. & Tobin, A. Plant biochemistry. Plant. Biochem. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203833483 (2008).

Hendrik, P., Ülo, N., Lourens, P., Ian, J. W. & Rafael, V. Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): a meta-analysis. New. Phytol. 182, 565–588 (2009).

Li, D. et al. Effects of low nitrogen supply on relationships between photosynthesis and nitrogen status at different leaf position in wheat seedlings. Plant. Growth Regul. 70, 257–263 (2013).

Moghaddam, M., Estaji, A. & Farhadi, N. Effect of organic and inorganic fertilizers on morphological and physiological characteristics, essential oil content and constituents of Agastache (Agastache foeniculum). J. Essent. Oil-Bearing Plants. 18, 1372–1381 (2015).

Singh, M., Singh, V. P. & Prasad, S. M. Responses of photosynthesis, nitrogen and proline metabolism to salinity stress in Solanum lycopersicum under different levels of nitrogen supplementation. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 109, 72–83 (2016).

Tabatabaei, S., Fatemi, L. & Fallahi, E. Effect of ammonium: nitrate ratio on yield, calcium concentration, and photosynthesis rate in strawberry. J. Plant. Nutr. 29, 1273–1285 (2006).

Hu, L., Liao, W., Dawuda, M. M., Yu, J. & Lv, J. Appropriate NH4+: NO3- ratio improves low light tolerance of mini Chinese cabbage seedlings. BMC Plant. Biol. 17. (2017).

Kiba, T., Kudo, T., Kojima, M. & Sakakibara, H. Hormonal control of nitrogen acquisition: roles of auxin, abscisic acid, and cytokinin. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 1399–1409 (2011).

Mohd-Radzman, N. H., Ismail, W. I. W., Adam, Z., Jaapar, S. S. & Adam, A. Potential roles of stevia rebaudiana bertoni in abrogating insulin resistance and diabetes: A review. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. (2013).

Hu, M., Yan, R., Ni, R. & Wu, H. Coastal degradation regulates the availability and diffusion kinetics of phosphorus at the sediment-water interface: mechanisms and environmental implications. Water Res. 250, 121086 (2024).

Serna, M. D., Borras, R., Legaz, F. & Primo-Millo, E. The influence of nitrogen concentration and ammonium/nitrate ratio on N-uptake, mineral composition and yield of citrus. Plant. Soil. 147, 13–23 (1992).

Sharma, P., Jha, A. B., Dubey, R. S. & Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 1–26 (2012).

Shams, M., Pokora, W., Khadivi, A. & Aksmann, A. Superoxide dismutase in Arabidopsis and chlamydomonas: diversity, localization, regulation, and role. Plant. Soil. 503 (1), 751–771 (2024).

Erdal, S. & Turk, H. Cysteine-induced upregulation of nitrogen metabolism-related genes and enzyme activities enhance tolerance of maize seedlings to cadmium stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 132, 92–99 (2016).

Guillén-Román, C. J., Guevara-González, R. G., Rocha-Guzmán, N. E., Mercado-Luna, A. & Pérez-Pérez, M. C. I. Effect of nitrogen privation on the phenolics contents, antioxidant and antibacterial activities in Moringa oleifera leaves. Ind. Crops Prod. 114, 45–51 (2018).

Domínguez-Valdivia, M. D. et al. Nitrogen nutrition and antioxidant metabolism in ammonium-tolerant and -sensitive plants. Physiol. Plant. 132, 359–369 (2008).

Kováčik, J. & Hedbavny, J. Ammonium ions affect metal toxicity in chamomile plants. South. Afr. J. Bot. 94, 204–209 (2014).

Strasser, R. J., Srivastava, A. & Tsimilli-Michael, M. The fluorescence transient as a tool to characterize and screen photosynthetic samples. Probing Photosynth Mech. Regul. Adapt. 443–480. (2000).

Brestic, M. & Zivcak, M. PSII fluorescence techniques for measurement of drought and high temperature stress signal in crop plants: protocols and applications. Mol. Stress Physiol. Plants 87–131. (2013).

Dazy, M., Jung, V., Férard, J. F. & Masfaraud, J. F. Ecological recovery of vegetation on a coke-factory soil: role of plant antioxidant enzymes and possible implications in site restoration. Chemosphere 74, 57–63 (2008).

Yagci, S., Yildirim, E., Yildirim, N., Shams, M. & Agar, G. Nitric oxide alleviates the effects of copper-induced DNA methylation, genomic instability, LTR retrotransposon polymorphism and enzyme activity in lettuce. Plant. Physiol. Rep. 24, 289–295 (2019).

Kucher, L. et al. Effects of complex of microelements and ecological factors on winter wheat productivity. J. Ecol. Eng. 26 (9), 341–353 (2025).

Marschner, H. Marschner’s mineral nutrition of higher plants. Marschner’s Min. Nutr. High. Plants. https://doi.org/10.1016/c2009-0-02402-7 (2002).

Ayad, H. S., Reda, F. & Abdalla, M. S. A. Effect of Putrescine and zinc on vegetative growth, photosynthetic pigments, lipid peroxidation and essential oil content of geranium (Pelargonium graveolens L). World J. Agric. Sci. 6, 601–608 (2010).

Clark, M. B., Mills, H. A., Robacker, C. D. & Latimer, J. G. Influence of nitrate: ammonium ratios on growth and elemental concentration in two azalea cultivars. J. Plant. Nutr. 26, 2503–2520 (2003).

Zhao, X., Bi, G., Harkess, R. L. & Blythe, E. K. Effects of different NH4: NO3 ratios on growth and nutrition uptake in Iris germanica ‘immortality.’ hortscience. 511045–1049. (2016).

Roosta, H. R., Rashidi, M., Karimi, H. R., Alaei, H. & Tadayyonnejhad, M. Comparison of vegetative growth and minituber yield in three potato cultivars in aeroponics and classic hydroponics with three different nutrient solutions. Journal-of-Soil-and-Plant-Interactions. 473–80. (2013).

Kalaji, H. M. et al. Frequently asked questions about chlorophyll fluorescence, the sequel. Photosynth Res. 132, 13–66 (2017).

Tyystjärvi, A. P. C. E. et al. Linking chlorophyll a fluorescence to photosynthesis for remote sensing applications: mechanisms and challenges. J. Exp. Bot. 1, 4065–4095 (2014).

Bityutskii, N., Pavlovic, J., Yakkonen, K., Maksimović, V. & Nikolic, M. Contrasting effect of silicon on iron, zinc and manganese status and accumulation of metal-mobilizing compounds in micronutrient-deficient cucumber. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 74, 205–211 (2014).

Rochaix, J. D. Assembly of the photosynthetic apparatus. Plant. Physiol. 155, 1493–1500 (2011).

Kalaji, H. M., Goltsev, V., Bosa, K., Allakhverdiev, S. I. & Strasser, R. J. Govindjee. Experimental in vivo measurements of light emission in plants: A perspective dedicated to David walker. Photosynth Res. 114, 69–96 (2012).

Kalaji, H. M. et al. Identification of nutrient deficiency in maize and tomato plants by invivo chlorophyll a fluorescence measurements. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 81, 16–25 (2014).

Baker, N. R. Chlorophyll fluorescence: A probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 59, 89–113 (2008).

Stirbet, A. & Govindjee On the relation between the Kautsky effect (chlorophyll a fluorescence induction) and photosystem II: basics and applications of the OJIP fluorescence transient. J. Photochem. Photobiol B Biol. 104, 236–257 (2011).

Strasser, R. J., Tsimilli-Michael, M., Qiang, S. & Goltsev, V. Simultaneous in vivo recording of prompt and delayed fluorescence and 820-nm reflection changes during drying and after rehydration of the resurrection plant Haberlea rhodopensis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 1797, 1313–1326 (2010).

Roosta, H. R., Estaji, A. & Niknam, F. Effect of iron, zinc and manganese shortage-induced change on photosynthetic pigments, some osmoregulators and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in lettuce. Photosynthetica 56, 606–615 (2018).

Harbinson, J., Croce, R., van Grondelle, R., van Amerongen, H. & van Stokkum, I. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a tool for describing the operation and regulation of photosynthesis in vivo. In Light Harvesting in Photosynthesis (539–571). CRC. (2018).

Aragão, R. M., Silva, E. N., Vieira, C. F. & Silveira, J. A. G. High supply of NO3 – mitigates salinity effects through an enhancement in the efficiency of photosystem II and CO2 assimilation in Jatropha curcas plants. Acta Physiol. Plant. 34, 2135–2143 (2012).

Feng Wang, J., Gao, S., Shi, X. & He, T. D. Impaired electron transfer accounts for the photosynthesis Inhibition in wheat seedlings (Triticum aestivum L.) subjected to ammonium stress. Physiol. Plant. 167, 159–172 (2019).

Zhou, Y. H. et al. Effects of nitrogen form on growth, CO2 assimilation, chlorophyll fluorescence, and photosynthetic electron allocation in cucumber and rice plants. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 12, 126–134 (2011).

Markou, G., Depraetere, O. & Muylaert, K. Effect of ammonia on the photosynthetic activity of Arthrospira and chlorella: A study on chlorophyll fluorescence and electron transport. Algal Res. 16, 449–457 (2016).

Boussadia, O., Steppe, K., Van Labeke, M. C., Lemeur, R. & Braham, M. Effects of nitrogen deficiency on leaf chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in two Olive tree cultivars ‘meski’ and ‘koroneiki’. J. Plant. Nutr. 38, 2230–2246 (2015).

Wani, B. A. et al. ul& Nitrogen deficiency in plants. In: Advances in Plant Nitrogen Metabolism (28–37). (CRC Press, 2022).

Li, Q., Li, B. H., Kronzucker, H. J. & Shi, W. M. Root growth Inhibition by NH4 + in Arabidopsis is mediated by the root tip and is linked to NH4 + efflux and GMPase activity. Plant. Cell. Environ. 33, 1529–1542 (2010).

Shamshiri, M. H. & Fattahi, M. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on photosystem II activity of three pistachio rootstocks under salt stress as probed by the OJIP-test. Russ J. Plant. Physiol. 63, 101–110 (2016).

Qu, C. et al. Effects of manganese deficiency and added cerium on photochemical efficiency of maize chloroplasts. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 146, 94–100 (2012).

Drath, M. et al. Ammonia triggers photodamage of photosystem II in the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Plant. Physiol. 147, 206–215 (2008).

Miranda, R., de Mesquita, S., Freitas, R. O., Prisco, N. S. & Gomes-Filho, J. T. Nitrate: ammonium nutrition alleviates detrimental effects of salinity by enhancing photosystem II efficiency in sorghum plants. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola E Ambient. 18 suppl, 8–12 (2014).

Baszyński, T., Pańczyk, B., Król, M. & Krupa, Z. The effect of nitrogen deficiency on some aspects of photosynthesis in maize leaves. Z. Für Pflanzenphysiologie. 74, 200–207 (1975).

Evans, J. & Terashima, I. Effects of nitrogen nutrition on Electron transport components and photosynthesis in spinach. Funct. Plant. Biol. 14, 59 (1987).

Khanna-Chopra, R. & Selote, D. S. Acclimation to drought stress generates oxidative stress tolerance in drought-resistant than -susceptible wheat cultivar under field conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 60, 276–283 (2007).

Dadasoglu, E. et al. Nitric oxide enhances salt tolerance through regulating antioxidant enzyme activity and nutrient uptake in pea. (2021).

Shams, M. & Khadivi, A. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance and their possible application in the breeding of vegetables. BMC Plant Biol. 23 (1), 139 (2023).

Mayne, S. T. Oxidative stress, dietary antioxidant supplements, and health: is the glass half full or half empty? Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 22, 2145–2147 (2013).

Corpas, F. J., Río, D., Palma, J. M. & L. A., & Impact of nitric oxide (NO) on the ROS metabolism of peroxisomes. Plants 8 (2), 37 (2019).

Upadhyaya, H., Khan, M. & Panda, S. Hydrogen peroxide induces oxidative stress in detached leaves of Oryza sativa L. Gen. Appl. Plant. Physiol. 33, 83–95 (2007).

Ekinci, M., Shams, M., Turan, M., Ucar, S., Yaprak, E., Yuksel, E. A., … Yildirim,E. (2024). Chitosan mitigated the adverse effect of Cd by regulating antioxidant activities,hormones, and organic acids contents in pepper (Capsicum annum L.). Heliyon, 10(17).

Araz, O. et al. Low-temperature modified DNA methylation level, genome template stability, enzyme activity, and proline content in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes. Sci. Hort. 294, 110761 (2022).

Chinnusamy, V., Jagendorf, A. & Zhu, J. K. Understanding and improving salt tolerance in plants. Crop Sci. 45, 437–448 (2005).

Kataria, S., Baghel, L., Jain, M. & Guruprasad, K. N. Magnetopriming regulates antioxidant defense system in soybean against salt stress. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 18, 101090 (2019).

Michalak, A. Phenolic compounds and their antioxidant activity in plants growing under heavy metal stress. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 15, 523–530 (2006).

Lin, Y. L., Chao, Y. Y., Huang, W. D. & Kao, C. H. Effect of nitrogen deficiency on antioxidant status and cd toxicity in rice seedlings. Plant. Growth Regul. 64, 263–273 (2011).

Shams, M. et al. Biosynthesis of capsaicinoids in pungent peppers under salinity stress. Physiol. Plant., 175(2), e13889. (2023).

Hong, Y., Boiti, A., Vallone, D. & Foulkes, N. S. Reactive oxygen species signaling and oxidative stress: transcriptional regulation and evolution. Antioxidants 13 (3), 312 (2024).

Hachiya, T. et al. Excessive ammonium assimilation by plastidic glutamine synthetase causes ammonium toxicity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 4944 (2021).

Funding

The authors are grateful to the Vali-e-Asr University for funding this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HRR and AE: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - Original Draft, Visualization. HRR, AK, and MKS: Writing - Review & Editing, and preparation of final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement of compliance

The authors confirm that permissions or licenses to collect Glycyrrhiza globra L. plants were obtained from the Ministry of Agriculture-Jahad of I.R. Iran. In all experiments on plants/plant parts in the present study, the use of plants complies with international, national, and/or institutional guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roosta, H.R., Estaji, A., Khadivi, A. et al. Balanced ammonium–nitrate nutrition enhances photosynthetic efficiency, micronutrient homeostasis, and antioxidant networks via ROS signaling in Glycyrrhiza glabra across soil and soilless systems. Sci Rep 15, 25404 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11181-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11181-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Response of licorice to different sources of nitrogen in soil and soilless culture systems

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A Systematic Review of Plant Responses to Drought Stress

Applied Fruit Science (2025)