Abstract

The aim of this study was to analyze the data from a cohort study of community-dwelling older people to clarify the impact of low tongue pressure on the onset of malnutrition. The analysis was divided into a baseline and a longitudinal analysis. The baseline analysis included 765 people (median age: 74 years; 276 men and 489 women), and the longitudinal analysis included 100 people (median age: 72 years; 33 men and 67 women). The baseline analysis showed that tongue pressure and the diagnosis of low tongue pressure using a cut-off of 30 kPa were associated with the risk of malnutrition (tongue pressure: odds ratio [OR] = 0.972, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 0.953–0.992, p = 0.006; the diagnosis of low tongue pressure: OR = 1.555, 95% CI = 1.050–2.302, p = 0.027). In the longitudinal analysis, tongue pressure and the diagnosis of low tongue pressure at baseline were associated with the onset of the risk of malnutrition after 4 years (tongue pressure: OR = 0.952, 95% CI = 0.907–0.998, p = 0.041; the diagnosis of low tongue pressure: OR = 2.698, 95% CI = 1.148–6.341; p = 0.023). In community-dwelling older people, low tongue pressure could increase the risk of future malnutrition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malnutrition in older people is a major international concern due to aging populations in various countries. Estimates suggest that approximately 25% of the global older population (aged ≥ 65 years) is currently malnourished or at risk of malnutrition1. An association between malnutrition and a number of health outcomes, such as frailty, muscle wastage, hypothermia, osteoporosis, mood changes and cognitive impairment, has been demonstrated in older people2. Furthermore, malnutrition has been shown to directly contribute to poor health outcomes, such as increased mortality2. These direct health effects also contribute to increased medical costs, further increasing the burden on society3. The identification of risk factors for malnutrition and subsequent intervention is thus a great medical and social challenge.

Malnutrition is thought to be caused by a combination of complex factors, including not only inappropriate dietary intake but also diseases such as malignant tumors and chronic inflammation, as well as social factors4,5,6,7. The Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) criteria were proposed in 2018 by major clinical nutrition societies around the world as a standard malnutrition diagnosis that encompasses these factors8. Malnutrition diagnosis using the GLIM criteria consists of three steps: initial screening for the risk of malnutrition, diagnosis of malnutrition in cases identified through screening, and assessment of severity. The first step, screening for malnutrition risk, aims to identify individuals at risk of malnutrition from a large number of individuals, and the use of the Mini Nutritional Assessment Tool - Short Form (MNA-SF), Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) and Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS-2002) is recommended for this purpose8. Screening for malnutrition risk is a crucial step in preventing poor prognosis and reducing healthcare costs, particularly among community-dwelling older people.

Research into the association between a decline in oral function and the onset and progression of malnutrition is a hot topic, and there has already been a report on the association between malnutrition and oral hypofunction in a cross-sectional study of community-dwelling older people9 and a prospective cohort study of older people who regularly receive health checks at hospitals10. Among oral functions, tongue pressure is an indicator that can quantitatively and objectively evaluate the function of the tongue, which is closely related to eating and swallowing functions. Tongue pressure has been adopted as one of the diagnostic criteria for oral hypofunction11 and sarcopenic dysphagia in Japan12 and research on the relationship with health outcomes is currently being actively pursued. Previous studies showed that tongue pressure decreases with age13 that a positive correlation is observed between tongue pressure and MNA score14 and that low tongue pressure is associated with malnutrition in elderly individuals14,15,16,17. However, as the above-mentioned studies were cross-sectional in design, no findings have yet been obtained regarding the longitudinal causal relationship between tongue pressure and malnutrition in community-dwelling older people.

Our hypothesis is that low tongue pressure is a risk factor for malnutrition. If this causal relationship is confirmed, it is expected that approaches such as tongue pressure training will contribute to the prevention of malnutrition in older people. The aim of this study is to analyze the effect of low tongue pressure on the risk of malnutrition assessed using the MNA-SF, using data from the Tarumizu Study, a prospective cohort study of community-dwelling older people.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this study, we adopted a prospective cohort study design, with exposure as tongue pressure and outcome as malnutrition risk. Participants in this study were enrolled from among those who participated in the Tarumizu City health assessment survey (Tarumizu Study) for people aged ≥ 40 years, conducted by Kagoshima University, Tarumizu City Hall and Tarumizu Chuo Hospital between July and December 2018. In the Tarumizu study, the city hall recruited participants by sending public information leaflets to residents’ addresses by post. This study conforms to the STROBE guidelines for prospective cohort studies, and approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee on Epidemiological and its related Studies, Sakuragaoka Campus, Kagoshima University (Approval No. 170351) prior to the start of the study. Participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation. Also, all methods were performed in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki. In this study, after investigating the cross-sectional association between tongue pressure and malnutrition risk in 2018 as a baseline analysis, we investigated the association between tongue pressure in 2018 and malnutrition risk in 2022 as a longitudinal analysis, targeting participants who had normal nutritional status at baseline. The inclusion criteria for the baseline analysis were set at participants aged ≥ 65 years who participated in the 2018 Tarumizu study. The exclusion criteria were set in accordance with past reports, and in order to ensure the reliability of the tongue pressure measurement results and the questionnaire, as follows: (1) participants aged < 65 years; (2) data missing; (3) dementia; (4) cerebrovascular disease18; (5) hemiplegia; and (6) Parkinson’s disease19. The inclusion criteria for the longitudinal analysis were set at participants aged ≥ 65 years who participated in the 2018 and 2022 Tarumizu studies. Exclusion criteria were set as follows: (1) participants aged < 65 years; (2) data missing; (3) dementia; (4) cerebrovascular disease; (5) hemiplegia; (6) Parkinson’s disease; and (7) participants assessed as being at risk of malnutrition as of 2018. Participants in the longitudinal analysis were followed up for four years, and outcomes were assessed in the Tarumizu study, which was conducted between July 2022 and March 2023.

Assessment of tongue pressure

The JMS tongue pressure measuring device (TPM-01; JMS Corporation, Hiroshima, Japan) was used to measure tongue pressure. Subjects placed the balloon probe in their mouth and fixed the plastic pipe by biting lightly on the center of the bilateral central incisors. They then closed their lips, raised their tongue and pressed the probe against the hard palate with maximum force; tongue pressure was recorded by the examiner. Measurements were taken three times, and the maximum value was recorded. This recorded tongue pressure was used in the analysis as a continuous variable. In addition, based on the evaluation criteria for oral hypofunction proposed by the Japanese Society of Gerodontology, low tongue pressure was diagnosed as a tongue pressure of less than 30 kPa11. Using this cutoff, the participants were divided into a normal tongue pressure group and low tongue pressure group.

Assessment of malnutrition

The Mini Nutritional Assessment Short-Form (MNA-SF) was used for nutritional assessment. The MNA-SF is a simple malnutrition screening tool developed for older people20,21. The MNA-SF was developed as a simplified version of the MNA, reducing the number of questions from 18 in the original version to 6, and is widely used as a simple and practical malnutrition screening tool requiring only 5 min per test. The MNA-SF consists of 6 questions from A to F. Each question is rated on a score of 0 to 3 points, and the final total for the 6 items is calculated. The highest total score is 14 and the lowest is 0. The lower the score, the higher the risk of malnutrition. Either lower leg circumference (CC) or body mass index (BMI) is used for item F. In the present study, BMI was used to assess item F. A person was assessed as being at risk of malnutrition if the total score was ≤ 11 points22.

Background data

We sampled the following variables as background data: sex (male/female), age (years), years of schooling (years), living alone (none/alone), sleep duration (hours per day), drinking frequency (frequency per week), smoking (none/having a history/current smoker), energy intake (calculated from brief-type self-administered diet history questionnaire [BDHQ]: kcal per day), diabetes mellitus (none/having a history/under treatment), cancer (none/having a history/under treatment), sarcopenia (diagnosis based on Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia [AWGS 2019]: none/sarcopenia/severe sarcopenia)23.

Statistical analysis

Only subjects with complete data were entered into the present analysis; subjects with missing values for the variables of exposure, outcome, or background data were excluded. The missing data were not imputed. Instead, the variables were compared between the groups before and after excluding the missing values to assess whether there were any changes in characteristics between the groups. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data, with the median (IQR: interquartile range) used for continuous variables and the absolute value (%: percentages) for categorical variables. For tests of normality, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used when the number of samples in a group was more than 100, and the Shapiro–Wilk test was used when the number was less than 100. Mann-Whitney U test and Pearson’s chi-square test were used for between-group comparisons in each variable. For risk analysis in the baseline population, we used univariate and multivariate binomial logistic regression analyses to assess the association between the risk of malnutrition and tongue pressure and between the risk of malnutrition and the diagnosis of low tongue pressure in the 2018 data. The variables for multivariate analysis were input using the forced entry method for those that had been reported in the past as confounding factors and for which no multicollinearity could be confirmed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). Variables with VIF < 7 were determined not to be multicollinear. The independent variables entered were sex, age, years of education, living alone, drinking frequency, smoking, sleep duration, energy intake, diabetes mellitus, cancer, sarcopenia, tongue pressure and the diagnosis of low tongue pressure. Propensity score matching was used in the longitudinal analysis to adjust for the same potentially confounding variables as in the baseline analysis. To calculate the estimated propensity score for each participant, we used a binary logistic regression analysis with the diagnosis of low tongue pressure as the dependent variable and sex, age, years of schooling, living alone, drinking frequency, smoking, sleep duration, energy intake, diabetes mellitus, cancer, and sarcopenia as the independent variables. The discriminate power of the propensity scores was quantified by measuring the receiver-operating-characteristic area (c-statics), and it was judged that appropriate discrimination was possible if the c-statics was within the range of 0.6–0.9. Using the estimated propensity score, nearest neighbor matching was performed so that the ratio of subjects in the normal tongue pressure group to the low tongue pressure group was 1:1. The balance before and after matching was evaluated using the standardized mean difference (SMD), and if it was 0.1 or less, it was evaluated as being well balanced. The caliper was set to the standard deviation of the estimated propensity score × 0.2. After adjustment by propensity score matching, the association between tongue pressure in 2018 and risk of malnutrition in 2022, and the association between a diagnosis of low tongue pressure in 2018 and risk of malnutrition in 2022 were assessed using Mann-Whitney U test, Pearson’s chi-square test and univariate logistic regression analysis. To account for the possibility that unknown confounding factors could overturn the significant results of the study, E-values were calculated against odds ratios and confidence intervals for the results of the logistic regression analysis of the baseline and longitudinal analyses24,25. We performed sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of the results: in the baseline analysis, we conducted multivariate logistic regression analysis using directed acyclic graphs to select the minimum number of confounding factors from background data; in the longitudinal analysis, we conducted multivariate logistic regression analysis using directed acyclic graphs, as well as propensity score-adjusted multivariate logistic regression analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using statistical software (SPSS ver29; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA; and R version 4.4.2). Two-sided p-values were calculated for all analyses, with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics and group comparison

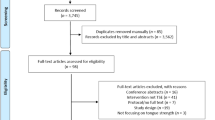

The participant selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Of the 1145 participants in the 2018 Tarumizu Study, a total of 765 eligible subjects were included in the baseline analysis, and then propensity score matching was performed on 202 subjects who were not at risk of malnutrition at baseline and could be followed up until 2022, resulting in 100 subjects who were ultimately included in the longitudinal analysis. Table S1 shows the changes in the characteristics of the subjects before and after excluding the missing data. No variables were significantly different between before and after the exclusion of missing data. The characteristics of the subjects in the baseline analysis are shown in Table 1, and the characteristics of the subjects before and after propensity score matching in the longitudinal analysis are shown in Table 2. The distributions of propensity scores before and after matching are shown in Fig. S1. The baseline analysis included 765 participants. Among them, the number in the low tongue pressure group was 276 (36.1%), and the number in the group at risk of malnutrition was 147 (19.2%). The percentage of people at risk of malnutrition was 15.7% in the normal tongue pressure group and 25.4% in the low tongue pressure group. Based on the background data, participants in the low tongue pressure group were more likely to be female, older, and living alone and more likely to have sarcopenia than those in the normal tongue pressure group. Before matching, the study population consisted of 202 participants. Among them, 60 (29.7%) participants were categorized into the low tongue pressure group, and 70 (34.7%) participants developed malnutrition risk between 2018 and 2022. The percentage of participants who developed malnutrition risk was 30.3% in the normal tongue pressure group and 45.0% in the low tongue pressure group. Comparison of the background data between the normal tongue pressure group and low tongue pressure group showed significant differences in drinking frequency, but no interpretable trend was seen. For the 202 subjects in the pre-matching population, the diagnosis of low tongue pressure was used as the dependent variable, and the estimated propensity score was calculated using sex, age, years of schooling, living alone, drinking frequency, smoking, sleep duration, energy intake, diabetes mellitus, cancer and sarcopenia as the independent variables. The c statistic for the estimated propensity score was 0.727 (Fig. S2), with a standard deviation of 0.1782. The caliper was set to 0.2. Nearest-neighbor matching was performed at a ratio of 1:1 with a caliper value of 0.0356. Matching excluded 102 participants and 100 were finally included in the post-matching population. Among the 100 participants in the post-matching population, 50 (50.0%) were categorized into the low tongue pressure group, and 35 (35.0%) developed malnutrition risk between 2018 and 2022. The participants who developed malnutrition risk made up 24.0% of the normal tongue pressure group and 46.0% of the low tongue pressure group. Although the background data revealed no significant difference in any of the variables between the normal and the low tongue pressure groups, the standardized mean difference (SMD) analysis revealed some items with incomplete balance adjustment, such as living alone, smoking, sleep duration, diabetes mellitus, cancer, sarcopenia (0.1 ≤ SMD < 0.2), and drinking frequency (0.3 ≤ SMD < 0.4).

Association between tongue pressure and risk of malnutrition in a baseline population

The results of the Pearson’s Chi-squared test are shown in Table 1, and the results of the Mann-Whitney U test are shown in Table 3. In the group comparison, the proportion of participants at risk of malnutrition was higher in the low tongue pressure group (p = 0.001), and also tongue pressure was lower in the malnutrition risk group (p < 0.001).

Risk analysis of tongue pressure and risk of malnutrition in baseline population

The results of the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 4. Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that both tongue pressure and the diagnosis of low tongue pressure were associated with the risk of malnutrition (tongue pressure: OR = 0.965, 95% CI = 0.948–0.983, p < 0.001; the diagnosis of low tongue pressure: OR = 1.818, 95% CI = 1.263–2.617, p = 0.001). Similarly, in multivariate logistic regression analysis, tongue pressure and the diagnosis of low tongue pressure were both associated with the risk of malnutrition (tongue pressure: OR = 0.972, 95% CI = 0.953–0.992, p = 0.006, E-value = 1.13, CI = 1.07; the diagnosis of low tongue pressure: OR = 1.555, 95% CI = 1.050–2.302, p = 0.027, E-value = 1.8, CI = 1.18).

Association between tongue pressure and risk of malnutrition in the pre- and post-matching population

The results of the Pearson’s Chi-square test are shown in Table 2, and the results of the Mann-Whitney U test are shown in Table 5. In both the pre- and post-matching populations, the proportion of individuals who would be at risk of malnutrition in 2022 was higher in the low tongue pressure group than the normal tongue pressure group in 2018 (pre-matching population: p = 0.045; post-matching population: p = 0.021), and correspondingly, the participants with malnutrition risk in 2022 had lower tongue pressure in 2018 (pre-matching population: p = 0.014; post-matching population: p = 0.018).

Risk analysis of tongue pressure and risk of malnutrition in the post-matching population

The results of the univariate logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 6. Logistic regression analysis showed that both tongue pressure and the diagnosis of low tongue pressure were associated with the risk of malnutrition. An association was also found between the diagnosis of low tongue pressure in 2018 and risk of malnutrition in 2022 (tongue pressure: OR = 0.952, 95% CI = 0.907–0.998, p = 0.041; E-value = 1.18, CI = 1.03; the diagnosis of low tongue pressure: OR = 2.698, 95% CI = 1.148–6.341, p = 0.023; E-value = 2.67, CI = 1.35).

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of the results, a logistic regression was conducted using a directed acyclic graph as a sensitivity analysis at baseline (Table S2). In the longitudinal study, we conducted two sensitivity analyses: a multivariate logistic regression analysis with a directed acyclic graph (Table S3), and a propensity score-adjusted multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table S4). The results of the sensitivity analysis for both the baseline and longitudinal studies were similar to the results of the main analysis.

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that low tongue pressure may be a risk factor for the onset of malnutrition in community-dwelling older people. In this study, we followed the community-dwelling elderly who participated in a health examination in Japan and analyzed the effect of tongue pressure at baseline on the risk of later malnutrition. Previously, our research group investigated the association between oral function decline and geriatric syndromes such as frailty, sarcopenia, mild cognitive impairment, and low protein intake in community-dwelling older people26,27,28. Although there have been many reports on the association between oral function and geriatric syndromes, the longitudinal causal relationship between tongue pressure and malnutrition has been unclear. This study showed that a decrease in tongue pressure and a diagnosis of low tongue pressure were significantly associated with later onset of malnutrition, and the results of the sensitivity analysis were similar to the main analysis. Thus our hypothesis that low tongue pressure is a risk factor for malnutrition is likely to be correct, and our results were valid.

In general, tongue pressure is defined as the maximum pressure when the tongue is pressed against the palate. This measured pressure is thought to be generated by the coordinated action of intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles, and is positioned as one of the diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic dysphagia as a measure of muscle strength in swallowing-related muscles12. Epidemiologically, tongue pressure decreases with age13. As to a possible gender difference, the findings are mixed: a meta-analysis found no gender difference in tongue pressure in individuals ≥ 60 years old, but a significantly lower tongue pressure in women among individuals < 60 years old29. Anatomically, atrophy of the tongue30 and geniohyoid muscles31 have been reported in older people compared to younger controls. Histologically, atrophy of the lingual muscles is frequently seen in older rats compared to younger controls32 and the muscle fiber size of the intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles of rats has been reported to decrease with age33 while in humans, amyloid deposition in the tongue has been reported to increase with age in those aged ≥ 60 years34. In the baseline population in the present study, the low tongue pressure group had more women and was older. In older people who are relatively healthy, such as those living in a community, it is possible that a gender difference in tongue pressure, reflecting the difference in muscle strength between men and women, persists even past ≥ 60 years of age. Regarding age, the characteristics of the baseline population in this study were consistent with previous reports showing an association between aging and low tongue pressure. Although the mechanism by which low tongue pressure leads to malnutrition is still unknown, we speculate that it may be a three-step process involving dysphagia. First, low tongue pressure causes problems with food-bolus formation and transport to the pharynx during the oral preparation phase of swallowing. Second, dysphagia prolongs the mealtime, causing the dysphagic eater to become exhausted before they have eaten enough. Alternatively, dysphagia causes repeated aspiration pneumonia. Third, the risk of malnutrition increases due to the inability to secure sufficient food over a long period of time, or due to the exhaustion caused by aspiration pneumonia. In fact, a low tongue pressure has been correlated with dysphagia in many clinical settings, including healthy older people35,36 stroke patients37,38,39 and older people admitted to hospital without neurological disorders40. Other studies have found that the relationship between dysphagia and malnutrition is interdependent41,42. Finally, low tongue pressure has been associated with prolonged mealtimes and an increased incidence of pneumonia43,44,45. Collectively, these results suggest that low tongue pressure affects the nutritional status of older people via dysphagia.

Two minor findings of this study also bear mention. First, in the baseline multivariate analysis, there was an association between living alone and the risk of malnutrition. In this study, we included years of education and living alone as measurable items, based on previous reports of an association between these social factors and malnutrition4. According to the report, living alone is associated with malnutrition/malnutrition risk at an odds ratio of around 1.8, and the results of this study were similar. Although social factors are not included in the nutrition screening tools and GLIM criteria currently used internationally, for analyses limited to community-dwelling older people, including living alone as a diagnostic item may improve the ability to predict malnutrition. On the other hand, there was no association between education years and malnutrition risk. In Japan, compulsory education guarantees a certain level of education, and this could have kept education years from being reflected in the results.

Secondly, we found that sarcopenia and tongue pressure were independently associated with malnutrition risk. It is already widely known that sarcopenia and malnutrition are mutually associated46 and as mentioned above, there are multiple reports of an association between tongue pressure and malnutrition. However, many of the previous reports have suggested that sarcopenic dysphagia, a condition that shares low tongue pressure and sarcopenia, is associated with malnutrition, so our finding that tongue pressure was directly associated with malnutrition independently of sarcopenia is of value. However, the relationship between the three variables of sarcopenia, tongue pressure and nutritional status, which were seen as independent factors, could not be verified in this study. Future investigations using structural equation modelling will be needed to examine the causal relationship among these three variables.

This study had three main limitations. First, the observation period was limited to four years. Because the number of years required for malnutrition to develop in older community-living individuals has not been clearly determined, we cannot rule out that our observation period was too short. Second, there was a bias in the selection of subjects. Our subjects were selected at a health examination with a recruitment format, which could have biased the selection toward healthy volunteers. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic forced a significant reduction in the scale of the Tarumizu study from 2019 onwards, resulting in 65.5% of cases being lost to follow-up. This would have considerably affected our results. Third, there was a limitation with respect to the adjustments for confounding. This study is a single cohort study in a single region of Japan, and the analysis uses complete data with no missing values. Furthermore, even after propensity score matching, the balance adjustment was not sufficient for some variables. Due to these limitations, the generalizability of the results may be limited. However, in terms of the observation period, the incidence of malnutrition risk over the four-year period of this study was 34.7%, which is broadly similar to the 32% prevalence of malnutrition risk in community-dwelling older people in the previous study22 so it is considered to be a sufficient research period. In addition, although we did not perform imputation for missing data, there was no significant difference in the distribution of variables between the complete data and the data before missing data were excluded. Furthermore, in the matching, the results of the sensitivity analysis conducted on the pre-matching group were similar to the results of the main analysis, and it is thought that the impact of excluding missing data and matching on the characteristics of the analysis population was not significant.

This study suggests that low tongue pressure may be a risk factor for malnutrition in older people living in the community, and that detecting a decrease in tongue pressure may enable malnutrition to be detected at an earlier stage. In other words, tongue pressure screening tests could uncover malnutrition risk in older community-living people at an earlier stage, and thereby improve the health of the population. Preventing malnutrition also has significant socioeconomic benefits, as it can lead to reduced medical costs and a reduced burden on medical institutions. In addition, continuous screening would help to maintain good nutritional status and promote health education in the community, leading to long-term health improvement. Based on the above, the tongue pressure test is an extremely useful tool for preventing malnutrition risk and managing nutritional status in community-dwelling groups of older individuals, and it is hoped that it will be actively used from the perspective of the population strategy.

Conclusions

In community-dwelling older individuals (age ≥ 65 years), tongue pressure at baseline was associated with malnutrition risk four years later.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Leij-Halfwerk, S. et al. Prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition risk in European older adults in community, residential and hospital settings, according to 22 malnutrition screening tools validated for use in adults >/=65 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 126, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.05.006 (2019).

Dent, E., Wright, O. R. L., Woo, J. & Hoogendijk, E. O. Malnutrition in older adults. Lancet 401, 951–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02612-5 (2023).

Wei, K., Nyunt, M. S. Z., Gao, Q., Wee, S. L. & Ng, T. P. Long-term changes in nutritional status are associated with functional and mortality outcomes among community-living older adults. Nutrition 66, 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2019.05.006 (2019).

Besora-Moreno, M., Llauradó, E., Tarro, L. & Solà, R. Social and economic factors and malnutrition or the risk of malnutrition in the elderly: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of observational studies. Nutrients 12, 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030737 (2020).

Cederholm, T. et al. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 36, 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.09.004 (2017).

Jensen, G. L. et al. Adult starvation and disease-related malnutrition: a proposal for etiology-based diagnosis in the clinical practice setting from the international consensus guideline committee. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 34, 156–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607110361910 (2010).

Soeters, P. B. et al. A rational approach to nutritional assessment. Clin. Nutr. 27, 706–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2008.07.009 (2008).

Cederholm, T. et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition - A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin. Nutr. 38, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.08.002 (2019).

Iwasaki, M. et al. Oral hypofunction and malnutrition among community-dwelling older adults: evidence from the Otassha study. Gerodontology 39, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12580 (2022).

Sawada, N., Takeuchi, N., Ekuni, D. & Morita, M. Effect of oral health status and oral function on malnutrition in community-dwelling older adult dental patients: A two-year prospective cohort study. Gerodontology 41, 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12718 (2024).

Minakuchi, S. et al. Oral hypofunction in the older population: position paper of the Japanese society of gerodontology in 2016. Gerodontology 35, 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12347 (2018).

Fujishima, I. et al. Sarcopenia and dysphagia: position paper by four professional organizations. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 19, 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13591 (2019).

Buehring, B. et al. Tongue strength is associated with jumping mechanography performance and handgrip strength but not with classic functional tests in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 61, 418–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12124 (2013).

Chang, K. V. et al. Suboptimal tongue pressure is associated with risk of malnutrition in Community-Dwelling older individuals. Nutrients 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061821 (2021).

Sakai, K. et al. Tongue strength is associated with grip strength and nutritional status in older adult inpatients of a rehabilitation hospital. Dysphagia 32, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-016-9751-5 (2017).

Okuno, K. et al. Relationships between the nutrition status and oral measurements for sarcopenia in older Japanese adults. J. Clin. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11247382 (2022).

Izumi, M. et al. Impact of tongue pressure and peak expiratory flow rate on nutritional status of older residents of nursing homes in japan: A Cross-Sectional study. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 24, 512–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1347-y (2020).

Hori, K., Ono, T., Iwata, H., Nokubi, T. & Kumakura, I. Tongue pressure against hard palate during swallowing in post-stroke patients. Gerodontology 22, 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-2358.2005.00089.x (2005).

Plaza, E. & Busanello-Stella, A. R. Tongue strength and clinical correlations in parkinson’s disease. J. Oral Rehabil. 50, 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13417 (2023).

Rubenstein, L. Z., Harker, J. O., Salvà, A., Guigoz, Y. & Vellas, B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the Short-Form Mini-Nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). Journals Gerontology: Ser. A. 56, M366–M372. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.6.M366 (2001).

Elia, M. & Stratton, R. J. An analytic appraisal of nutrition screening tools supported by original data with particular reference to age. Nutrition 28, 477–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2011.11.009 (2012).

Isautier, J. M. J. et al. Validity of Nutritional Screening Tools for Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 20(1351 e1313-1351 e1325), 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.06.024 (2019).

Chen, L. K. et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 300–307 e302 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012

Mathur, M. B., Ding, P., Riddell, C. A. & VanderWeele, T. J. Web site and R package for computing E-values. Epidemiology 29, e45–e47. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000864 (2018).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Ding, P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-Value. Ann. Intern. Med. 167, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2607 (2017).

Nakamura, M. et al. Association of Oral Hypofunction with Frailty, Sarcopenia, and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Cross-Sectional Study of Community-Dwelling Japanese Older Adults. J. Clin. Med. 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10081626 (2021).

Nishi, K. et al. Relationship between Oral Hypofunction, and Protein Intake: A Cross-Sectional Study in Local Community-Dwelling Adults. Nutrients 13, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124377 (2021).

Mishima, Y. et al. Association between cognitive impairment and poor oral function in Community-Dwelling older people: A Cross-Sectional study. Healthcare 13, 589 (2025).

Arakawa, I. et al. Variability in tongue pressure among elderly and young healthy cohorts: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 48, 430–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13076 (2021).

Tamura, F., Kikutani, T., Tohara, T., Yoshida, M. & Yaegaki, K. Tongue thickness relates to nutritional status in the elderly. Dysphagia 27, 556–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-012-9407-z (2012).

Feng, X. et al. Aging-Related geniohyoid muscle atrophy is related to aspiration status in healthy older adults. Journals Gerontology: Ser. A. 68, 853–860. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gls225 (2012).

Cullins, M. J. & Connor, N. P. Alterations of intrinsic tongue muscle properties with aging. Muscle Nerve. 56, E119–e125. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25605 (2017).

Kletzien, H., Hare, A. J., Leverson, G. & Connor, N. P. Age-related effect of cell death on fiber morphology and number in tongue muscle. Muscle Nerve. 57, E29–E37. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25671 (2018).

Yamaguchi, A., Nasu, M., Esaki, Y., Shimada, H. & Yoshiki, S. Amyloid deposits in the aged tongue: a postmortem study of 107 individuals over 60 years of age. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 11, 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.1982.tb00161.x (1982).

Yoshida, M. et al. Decreased Tongue Pressure Reflects Symptom of Dysphagia. Dysphagia 21, 61–65 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-005-9011-6

Liu, H. Y. et al. Decreased Tongue Pressure Associated with Aging, Chewing and Swallowing Difficulties of Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Taiwan. J. Pers. Med. 11, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11070653 (2021).

Lee, J. H. et al. The relationship between tongue pressure and oral dysphagia in stroke patients. Ann. Rehabil Med. 40, 620–628. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2016.40.4.620 (2016).

Konaka, K. et al. Relationship between tongue pressure and dysphagia in stroke patients. Eur. Neurol. 64, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1159/000315140 (2010).

Hirota, N. et al. Reduced tongue pressure against the hard palate on the paralyzed side during swallowing predicts dysphagia in patients with acute stroke. Stroke 41, 2982–2984. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.594960 (2010).

Maeda, K. & Akagi, J. Decreased tongue pressure is associated with sarcopenia and sarcopenic dysphagia in the elderly. Dysphagia 30, 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9577-y (2015).

Ueshima, J. et al. Nutritional management in adult patients with dysphagia: position paper from Japanese working group on integrated nutrition for dysphagic people. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 23, 1676–1682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2022.07.009 (2022).

Hudson, H. M., Daubert, C. R. & Mills, R. H. The interdependency of Protein-Energy malnutrition, aging, and dysphagia. Dysphagia 15, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004559910007 (2000).

Steele, C. M. & Cichero, J. A. Y. Physiological factors related to aspiration risk: A systematic review. Dysphagia 29, 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9516-y (2014).

Nakamori, M. et al. Prediction of pneumonia in acute stroke patients using tongue pressure measurements. PLoS One. 11, e0165837. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165837 (2016).

Sakamoto, Y. et al. Effect of decreased tongue pressure on dysphagia and survival rate in elderly people requiring long-term care. J. Dent. Sci. 17, 856–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2021.09.031 (2022).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 48, 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to specially thank all the participating staff members and study participants in the Tarumizu Study, as well as the Collaborative Group.

Funding

This research was funded by a JSPS KAKENHI (no. JP25K20379).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: R.T. and T.O.; methodology: R.T., K.N., H.M. and Y.M.(Yuhei Matsuda); software: R.T. and Y.M.(Yuhei Matsuda); validation, K.N., M.N., Y.M.(Yuhei Matsuda) and T.O.; formal analysis: R.T., Y.M.(Yuhei Matsuda), and T.K.(Takahiro Kanno); investigation: R.T., K.N., M.N., H.Y., Y.N., Y.H., Y.S., Y.M.(Yumiko Mishima), M.I., Y.Y., K.Y., K.K and T.O.; resources: H.M., T.K.(Takuro Kubozono), M.O. and T.O.; data curation: R.T., K.N., M.N. and T.O.; writing—original draft preparation: R.T. and T.O.; writing—review and editing: R.T., K.N., Y.M.(Yuhei Matsuda), H.M., T.K.(Takuro Kubozono), T.T., M.O. and T.O.; visualization: R.T., K.N. and T.O.; supervision: H.M., M.O., T.K.(Takahiro Kanno) and T.O.; project administration: T.K.(Takuro Kubozono), T.T. and M.O.; and funding acquisition: N.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declaration

This study was approved by Kagoshima University Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Review Committee (approval no. 170351).

Consent to participate

/publish: Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before participation in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takaoka, R., Nishi, K., Nakamura, M. et al. Association between malnutrition and low tongue pressure in community-dwelling older people: a population-based cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 25420 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11229-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11229-x