Abstract

Workplace learning is prevalent in corporate environments. However, unreasonable workplace learning can induce stress among employees. Based on the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory, this study aims to explore whether the resulting stress constitutes a hindrance job demand when learning tasks in the workplace are overly burdensome and examinations are excessively difficult and whether this stress compromises employees’ sleep quality and induces shortcut motivation, thereby reducing safety performance. Data from 723 employees was collected, confirm that both sleep quality and shortcut motivation mediate the impact of workplace learning examination stress on safety performance. The study also introduces occupational calling as a personal resource that mitigates the negative effects of workplace learning examination stress. Our research enriches our understanding of the impact of workplace learning and occupational calling on safety performance, with significant implications for employee safety and health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In railway transportation, approximately 75% of accidents are attributed to human errors, with many resulting from employees not strictly adhering to safety protocols. Typical instances of such non-compliance include drivers exceeding speed limits, signalmen issuing clearance signals in dangerous situations, and dispatchers making operational errors1. Compared to analogous industries, railway transportation is characterized by complex operational environments, high speeds, and large number of passengers, making safety a long-term and critical concern2,3. In practice, safety performance is a paramount behavioral indicator for railway employees. Safety performance stems from job performance. A two-dimensional model of safety performance was proposed: safety participation and safety compliance4. Workplace learning is the process through which employees engage in training, education, and developmental courses, as well as experiential learning, aimed at acquiring and enhancing skills needed to fulfill the demands of organization5. Currently, Chinese railway companies commonly employ methods of learning and examination to enhance employees’ mastery of professional knowledge and skills, aiming to reduce human errors and improve safety performance at work.

We draw upon the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory to interpret the relation between workplace learning examination and safety performance. As is indicated by the JD-R theory, job demands refer to the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort and are thus associated with certain physiological and psychological costs. Job resources are defined as factors that help individuals achieve work goals, mitigate the negative effects of job demands, and stimulate personal growth, learning, and development6. Van den Broeck et al. integrated two types of job demands into the JD-R model, the first job demands that trigger negative emotions and hinder employees’ goal achievement and well-being are termed ‘hindrance job demands’. The second job demands are termed ‘challenge job demands’. It’s both energetically draining and exhilarating, eliciting problem-centered coping. It may assist employees in achieving work goals7. Previous studies have primarily focused on the positive effects of workplace learning and examinations on safety performance, viewing them as job resources or challenging job demands8,9.

However, the rapid economic development and continuous technological changes currently compel employees to constantly enhance their professional abilities. Workplace learning and examination may become additional sources of stress beyond the existing workload, and we refer to this pressure as workplace learning examination stress10. Previous study has pointed out that employees need to spend more time on the learning process, which encroaches on extra work time11. This means that excessive workplace learning and examination greatly increases employees’ overall workload and strains their time and resources. Literature indicates that unreasonable workplace learning and examinations have largely failed to positively impact employees’ performance and productivity12. Furthermore, research has confirmed that the greater the workplace learning examination stress, the more overtime and heavier the workload, and consequently, the more negative the impact on employees’ wellbeing and performance10,13,14.

Moreover, most Chinese railway companies adopt a authoritarian management style, emphasizing strict rules and regulations, which can lead to negative emotional experiences among employees, thereby reducing their safety performance4,15. As a significant managerial practice in railway companies, workplace learning examinations might also be excessive and overly strict. Consequently, it is reasonable to infer that the stress generated from excessive learning tasks and overly difficult examinations constitutes a hindrance job demand, negatively affecting safety performance. Workplace learning examination stress, resulting in a lack of time and cognitive resources, may exacerbate the conflict between adhering to rules and completing work quickly, where adhering to safety rules often requires more time and effort, and employees are more inclined to engage in unsafe behaviors16. This stress caused by an excessive number of tasks may also induce negative emotions in employees, leading to intentional rule violations, thus lowering safety performance17,18,19. However, no empirical studies have yet explicitly explored the negative impacts on railway employees’ safety performance from the perspectives of the volume of learning tasks and the difficulty of examination.

Previous research explored how workplace learning positively predicts railway employee safety performance20. However, due to differences in the form, intensity, and content of workplace learning in this study, the mechanisms of influence may differ. Therefore, the key mechanisms through which workplace learning examination stress and safety performance deserve attention. According to JD-R theory, job demands impact job performance through the mediation of the health impairment process21. Previous research has closely linked sleep quality to mental and physical health22, and workplace learning examination stress is a hindrance job demand in this study. Therefore, we contend that one of the most likely mediators of the association between workplace learning examination stress and safety performance is sleep quality. Previous studies have suggested that hindrance job demand (e.g. workload) negatively correlates with sleep quality23. As highlighted earlier, excessive learning tasks and overly difficult examination excessively occupy employees’ time outside of regular work and deprive their energy. Even after leaving the workplace, due to examination stress, employees have to spend time rethinking about or remembering professional knowledge, keeping them in a prolonged state of psychological tension, resulting in trouble sleeping, frequent awakenings, and insufficient sleep time, thus reducing sleep quality. Therefore, we believe that workplace learning examination stress impairs employees’ sleep quality. In addition, as railway operations require prolonged intense concentration to keep high sensitivity, poor sleep quality may cause increased reaction times in timely tasks24,25, which has been indicated by studies that sleep quality is a significant factor influencing railway drivers’ driving behaviors26. Therefore, sleep quality is positively related to safety performance.

According to JD-R theory, job demands also impact job performance through the mediation of the motivation process. Safety motivation refers to an individual’ s willingness to involve in safe behaviors and the value associated within them. Research has shown that safety motivation is not only a determinant factor of safety performance, but also mediates the effect of job demands on safety performance27. Therefore, we infer that some types of safety motivation (i.e., shortcut motivation) would also mediate the correlation between job demands and safety performance. Shortcut behavior refers to completing tasks in less time than typical or standard procedures required, which might increase efficiency but also pose more risks, such as industrial accidents28. Simplifying or omitting operational procedures is a typical shortcut behavior in train driving tasks, such as drivers simplifying train inspection procedures or duty officers not dynamically monitoring track circuits during tests29. Therefore, the shortcut motivation is defined as people’ s motivation towards these simplified behaviors30,31. Previous research has indicated that work stress is an important factor that leads to the emergence of shortcut motivation. For instance, work-related time stress can lead to the convenience effect, where workers, in an effort to meet production deadlines, accelerate their work pace and become reluctant to wear protective gear32,33. Studies have also confirmed that individuals are more motivated to take shortcuts when faced with heavy workloads28. Therefore, we infer that workplace learning examination stress may generate shortcut motivation among railway workers who are confronted with the conflict between meeting the examination requirement and daily safety routine. In addition, previous studis have shown that shortcut motivation has a significant negative impact on workers’ safety performance, and is one of the important factors contributing to accidents18,34. However, no research has focused on the roles of sleep quality and shortcut motivation in the relationship between learning examination stress and safety performance.

Even if objective factors such as workplace learning and examination may explain most variance in safety performance, the individual traits, which could be trained and improved, should not be neglected35,36. In the JD-R theory, personal resources refer to the beliefs individuals hold about their control over themselves and their environment, such as optimism and self-efficacy. The JD-R theory emphasizes that personal resources can buffer the negative impacts of hindrance job demand37,38. In recent years, the motivational roles of employees’ occupational calling have been increasingly studied by researchers and managers39. Occupational calling was defined as a strong sense of meaning and passion experienced by individuals in their fields40. Previous studies have classified occupational calling as a personal resource41.

Previous research exploring occupational calling suggested that individuals with a higher occupational calling are capable of exerting more effort and adopting effective strategies to proactively solve problems42. Thus, they are better able to fulfill organizational learning and examination without excessively occupying their time and energy, ensuring sleep quality and less likely to develop shortcut motivation passively. Additionally, they possess strong self-regulation when facing job demands42. Despite facing significant workplace learning examination stress, they can quickly regulate their emotions, reducing the negative impacts on their mental, physical health and job performance. Several studies have found that train drivers and pilots with a high occupational calling demonstrate better work engagement and safety performance3,43. Therefore, we believe that occupational calling, as a personal resource, could mitigate the negative impacts of workplace learning examination stress, thereby maintaining better safety performance. More importantly, unlike stable and difficult-to-change personal traits, occupational calling is a dynamic personal resource that can be enhanced through training and other interventions40,44. Verifying the moderating effect of this variable holds significant practical implications for organizational management.

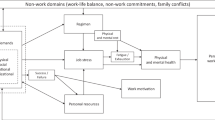

Referring to JD-R theory37, we aim to evaluate how workplace learning examination stress impacts the safety performance of railway employees and its mechanisms (the model path see Fig. 1). We hypothesized that workplace learning examination stress negatively relates to safety performance (H1); sleep quality (H2) and shortcut motivation (H3) mediates the relationship between workplace learning examination stress and safety performance; and occupational calling moderates the direct effects of workplace learning examination stress on sleep quality (H4a) and shortcut motivation (H4b), also moderates the indirect effects of workplace learning examination stress on safety performance through sleep quality (H5a) and shortcut motivation (H5b).

Methods

Procedure and sample

Data were gathered from a railway organization based in Chengdu, China. The research procedure and data collection method complies with the American Psychological Association ethical standards and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards, and were approved by the research ethics committee in the Liaoning Normal University (LL2024091). Also, all methods were carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations. Prior to the data collection process, all staff members were notified that participating in the survey was entirely optional and that their answers would remain confidential. In total, 1,237 employees took part in the survey. Data from participants who failed attention check questions or had missing values were excluded. The final sample analyzed consisted of 723 employees (pass rate: 58.45%). Of these, 81.9% were male and 18.1% were female. The mean age of the participants was 38.13 years (SD = 11.53), with over 66.5% of the employees having an education level of high school or above.

Measures

Workplace learning examination stress

The Perception of Academic Stress Scale45, which measures individual cognitive and academic stress, consists of four dimensions. The overall reliability of the scale is 0.7 (good reliability). This scale has been widely used in Chinese populations46. For this study, the ‘Perceptions of workload and examinations’ dimension was used, comprising four items with a reliability of 0.6. This dimension addresses stress related to excessive workload, lengthy assignments, and concerns about failing examinations. Examples include “The examination questions are usually difficult”. Responses were scored using a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where higher scores indicate greater workplace learning examination stress. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.804, indicating high reliability.

Sleep quality

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)47, a standardized and reliable tool to assess subjective sleep quality. This scale has been widely used in Chinese adult populations48,49. Scores range from 0 (best possible sleep) to 21 (worst possible sleep), with scores above 5 indicating sleep disturbances. For ease of understanding of the relationships between variables, scores were inverted for data analysis, following the recommended practices of Chang et al.50. As such, ranges were from 0 (worst possible sleep) to 21 (best possible sleep), with scores below 16 indicating sleep disturbances. By reversing the PSQI scores, we have preserved the scientific integrity of the scale while optimizing the presentation of the data to align with human cognitive habits and enhancing comparability with other studies. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the current study was 0.92, indicating very high reliability.

Shortcut motivation

The Unsafe Motivation Scale34 was designed for Chinese workers to measure their unsafe motivation and has seven dimensions. This study focused on the dimension of shortcut motivation. Examples include “When not supervised, I could save effort by reducing some procedures”. A Likert scale from 1 to 5 was used, where higher scores indicate greater shortcut motivation. Cronbach’s alpha for this dimension was 0.713, indicating good reliability.

Occupational calling

The Calling and Vocation Questionnaire (CVQ)51 was employed. The scale consists of 12 items divided into three subscales: transcendent summons, purposeful work, and prosocial orientation. This scale has been widely used in Chinese adult populations52. Examples of items include “I believe that I have been called to my current line of work”. Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale, where higher scores indicate a stronger occupational calling. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.858, indicating high reliability.

Safety performance

The 6-item Safety Performance Scale53,54 divides safety performance into compliance and participation dimensions, each with three items. This scale has been widely used in Chinese adult populations3. Examples include “I use the correct safety procedures to complete my work”. The scale was scored using a 5-point Likert scale, where higher scores indicate better safety performance. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.832, indicating high reliability.

Control variables

The study controlled for gender, age, station segment affiliation, and educational level. As previous research has shown, these variables impact employee safety performance55,56. Age was measured in years. Gender was measured as a dichotomous variable coded as 1 for male, and 2 for female. Railway Station Sections were coded as 1 for locomotive depot, 2 for rolling stock depot, 3 for traffic department, 4 for engineering department, 5 for power supply department, and 6 for electrical engineering department. Education level was coded 1 for junior high school, 2 for secondary vocational school, 3 for high school, 4 for junior college, and 5 for university.

Statistical analyses

SPSS 26.0 and PROCESS 3.4.1 macro were used. Initially, descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and linear regression analyses of the principal variables were conducted. Subsequently, the mediating role of sleep quality and shortcut motivation between workplace learning examination stress and safety performance was examined using models 4 of the PROCESS 3.4.1 macro, with 5,000 bootstrapped samples. Additionally, simple moderation tests and moderated mediation tests57 were conducted using models 1 and 7 of the PROCESS 3.4.1 macro, with 5,000 bootstrapped samples. As mentioned earlier, the scoring method for the scales used in this study differs; therefore, this study employs standardized coefficients (Z-score) of the scale scores for the calculations mentioned above.

Results

Common method bias

Given the self-report nature of the data collected in this study, potential common method bias was a concern. To address this issue, anonymity and confidentiality were emphasized during the survey administration to minimize sources of bias. Additionally, Harman’s single-factor test58 was conducted to assess common method bias. The results indicated that 12 factors with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted without rotation, with the first factor explaining 21.41% of the variance (< 40%). Therefore, common method bias does not appear to significantly affect the results of this study.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

The CFA results demonstrated that the fit of the hypothesized five-factor model was acceptable (χ2(df = 451) = 1348.205, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.917, TLI = 0.909, RMSEA = 0.052, SRMR = 0.064). We compared the five-factor model against a four-factor model (sleep quality and workplace learning examination stress were combined, χ2(df = 455) = 2143.990, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.843, TLI = 0.829, RMSEA = 0.072, SRMR = 0.079), a three-factor model (shortcut motivation, sleep quality and workplace learning examination stress were combined,χ2(df = 458) = 2576.986, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.804, TLI = 0.787, RMSEA = 0.080, SRMR = 0.089), a two-factor model (shortcut motivation, occupational calling and safety performance were combined, sleep quality and workplace learning examination stress were combined,χ2(df = 459) = 3636.371, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.706, TLI = 0.682, RMSEA = 0.098, SRMR = 0.105), and a one-factor model (all five variables were merged into a single factor,χ2(df = 460) = 5286.966, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.553, TLI = 0.518, RMSEA = 0.121, SRMR = 0.135). The model comparison demonstrated that the five-factor model provided the best fit for the data. These findings suggested that the five key variables (i.e., workplace learning examination stress, sleep quality, shortcut motivation, occupational calling, and safety performance) could be distinguished from each other.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of the variables. As shown, workplace learning examination stress was negatively correlated with safety performance(r = − 0.13, p < 0.001), providing preliminary support for H1. Workplace learning examination stress was positively correlated with both sleep quality(r = − 0.37, p < 0.001) and shortcut motivation(r = 0.35, p < 0.001). Sleep quality was positively correlated with safety performance (r = 0.15, p < 0.001), and shortcut motivation was negatively correlated with safety performance (r = − 0.28, p < 0.001).

Hypothesis testing

Linear regression analysis was performed, with safety performance as the dependent variable. Model 1 included gender, age, station segment, and educational level as control variables, and Model 2 added workplace learning examination stress as an independent variable. Results (see Table 2) indicated that workplace learning examination stress significantly predicted safety performance in Model 2(β = − 0.128, p < 0.01), supporting H1.

A mediation model was conducted to examine whether sleep quality and shortcut motivation could mediate the association between workplace learning examination stress and safety performance. The results (Table 3) indicated that the direct effect of workplace learning examination stress on safety performance was not significant (β = − 0.001, 95% CI[− 0.081, 0.078]). Sleep quality (β = − 0.032, 95% CI[− 0.067, − 0.003]) and shortcut motivation (β = − 0.094, 95% CI[− 0.130, − 0.062]) fully mediate the predictive relationship of workplace learning examination stress on safety performance, supporting H2 and H3.

We tested H4a and H4b using PROCESS macro model 1. The results revealed that the interaction between workplace learning examination stress and occupational calling significantly predicted the shortcut motivation (β = − 0.083, p < 0.01). Simple slope analysis (Fig. 2: simple slopes plotted at ± 1 SD of occupational calling) showed that the positive impact of workplace learning examination stress on shortcut motivation was stronger for employees with lower levels of occupational calling (Low: β = 0.387, 95% CI [0.296, 0.478], p < 0.001; Mean: β = 0.304, 95% CI [0.236, 0.373], p < 0.001) than for those with higher levels (High: β = 0.221, 95% CI [0.128, 0.315], p < 0.001). As such, H4b was validated. However, the interaction did not significantly predict sleep quality (β = 0.04, p = 0.196). Thus, H4a was not validated.

To validate H5a and H5b, we conducted tests of moderated mediation effects using PROCESS macro model 7 along with bootstrapping (N = 5000). The results (see Fig. 3) indicated that occupational calling attenuated the indirect effect of workplace learning examination stress on safety performance through shortcut motivation, with a moderated mediation index = 0.022, 95%CI[0.004, 0.044]. Specifically, when occupational calling was high, the indirect effect of workplace learning examination stress on safety performance through shortcut motivation was significant and lower, β= − 0.060 (95%CI[− 0.094, − 0.031]). In contrast, when occupational calling was average or low, the effect was significant and stronger (Mean: β= − 0.082, 95% CI[− 0.114, − 0.054]; Low: β= − 0.105 (95% CI[− 0.148, − 0.067]), thereby validating H5b. Occupational calling did not significantly reduce the indirect effect of workplace learning examination stress on safety performance through sleep quality, with a moderated mediation index = 0.004, 95% CI[− 0.003, 0.012]. Therefore, H5a was not validated.

Discussion

In this study, we applied the JD-R theory to understand the process by which workplace learning examination stress negatively relates employee safety performance. Our findings demonstrate that workplace learning examination stress impacts safety performance through sleep quality and shortcut motivation, and the latter’s mediation effect varies depending on the level of occupational calling. Importantly, this study extends the JD-R theory and the existing literature by validating that workplace learning examination stress is a hindrance job demand and reveals how the demand and the occupational calling as a personal resource predict railway employees’ health detriment, motivation process, and safety performance.

This study theoretically and empirically contributes to the understanding of the ‘double-edged sword’ effect of workplace learning. We offered new insights into how workplace learning affects safety performance. Previous research identified the positive impact of workplace learning on employee performance59,60. Researches based on the JD-R theory predominantly analyzes it as a job resource9. However, whether job characteristics are seen as job resources, challenge demands, or hindrance demands depends on the context27. The differing effects might relate to the volume of learning tasks and the difficulty of examination. As our findings showed, excessively scheduled professional learning tasks and overly difficult examination can cause a conflict between learning tasks and daily work requirements, negatively impacting safety performance. This is also a manifestation of the negative impact of authoritarian management in railway organizations4,15. Consequently, our study provides empirical support for the notion that workplace learning examination stress is a hindrance job demand and has a negative impact on safety performance.

Additionally, the present research highlights a key mechanism linking workplace learning examination stress and safety performance. Workplace learning examination stress, as a hindrance job demand, leads to conflicts between exam preparation and daily work in terms of time and energy. Employees cope with this conflict in two ways: either by exerting extra effort to complete learning tasks or by reducing the time and energy invested in work. These coping strategies manifest as deteriorated sleep quality and increased shortcut motivation, thereby reducing safety performance. We validated the mediating roles of health detriment process (sleep quality) and motivation process (shortcut motivation) between hindrance demand (workplace learning examination stress) and job outcomes (safety performance), which is consistent with the JD-R theory and further enrich it37.

Our findings also suggest that occupational calling can mitigate the triggering effect of workplace learning examination stress on shortcut motivation. For employees with a high occupational calling, despite the presence of workplace learning examination stress, their strong identification with personal value and the significance of their work provides them with increased motivation to cope with job demands39. They are more likely to complete work tasks according to standards and are less likely to adopt shortcuts or violate safety procedures. In contrast, employees with a low occupational calling lack the capability to handle work demands and strict self-discipline3,42, thus more easily developing shortcut motivation when facing workplace learning examination stress. However, in this study, occupational calling did not significantly moderate the negative correlation between workplace learning examination stress and sleep quality, contradicting previous findings61. This discrepancy might be due to the ‘double-edged sword’ effect of occupational calling, which, while increasing positive employee emotions, also increases workaholic tendencies62. Compared to employees with a moderate level of occupational calling, those with excessively high levels expend more resources to meet work demands, leading to higher levels of fatigue63. In our study, employees with excessively high occupational calling are more inclined to spend considerable personal time studying professional knowledge, thus encroaching on their sleep time and reducing sleep quality; employees with excessively low occupational calling cannot effectively regulate workplace learning examination stress, similarly harming sleep quality, thereby weakening the positive regulatory role of occupational calling as a personal resource. Our research validates the JD-R theory’s view of personal resources, that personal resources can reduce the adverse role of job demands37, and adds to the complexity of this effect.

Lastly, our findings offer a detailed comprehension of how occupational calling can influence the mechanisms driving the effects of workplace learning examination stress. Our results showed that the extent to which shortcut motivation can explain the mediation mechanism of the impact of workplace learning examination stress on safety performance depends on employees’ occupational calling. Our empirical evidence indicated that as employees’ occupational calling becomes higher, workplace learning examination stress is less likely to reduce safety performance through enhancing their shortcut motivation.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. First, as the cross-sectional design was used, caution is warranted in our causal interpretations of the relationships between variables. Prospective studies could use a longitudinal design to validate our findings. Second, we collected data using self-report measures, and although tests displayed that common method bias did not significantly impact our results, there remains a risk of lack of objectivity. Prospective studies could use multiple data sources, such as objective records, as a source of data for safety performance. Third, as this study focuses on the railway industry, the majority of participants are male. Future research could validate the findings of this study using a participant group with a more balanced gender ratio. Additionally, our participants were from a railway company in China, so the findings of our study may not necessarily be suitable for organizations in different countries or fields. China is known for a high power-distance culture64, and railway organizations adopt a authoritarian management style15 In such a culture, demanding workplace learning and examination may easily cause stress in employees. Future research could validate our findings in organizations across different cultures and sectors.

Practical implications

Despite the aforementioned limitations, our study holds valuable practical implications for railway company management. Combining previous research with our findings, workplace learning can have either positive or negative effects on job performance. Managers should leverage the positive aspects of workplace learning and avoid its negative impacts. Firstly, companies should adopt reasonable learning methods, such as mentoring20, and arrange appropriate amounts of learning tasks and examination standards. Experienced employees can be involved in designing learning tasks and establishing examination criteria, ensuring that the learning content is practically relevant. While enhancing employee safety awareness and professional knowledge, try not to occupy too much rest time and avoid conflicts with daily work. Moreover, managers could motivate employees to view professional knowledge learning and examination as job resources or challenging demands, rather than hindrance demands, creating a positive on-the-job learning atmosphere.

Secondly, our research can help managers understand how workplace learning examination stress reduces employees’ safety performance. Managers must be aware that reduced sleep quality and increased shortcut motivation could be a potential signal of decreased safety performance when they perceive excessive workplace learning examination stress. Additionally, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores were below 16, indicating that employees in railway companies have poor sleep quality, which may indicate the presence of sleep disorders. This could be due to the shift work adopted by most job types in railway companies24. Managers and future research should focus on employees’ sleep condition and shortcut motivation, optimizing management systems or actively taking intervention measures.

Furthermore, our findings show that people with a strong occupational calling are less probable to be impacted by workplace learning examination stress. Thus, enhancing employees’ occupational calling is an effective approaches to reduce the negative effects of workplace learning examination stress. Previous research suggested that the level of occupational calling can be enhanced by interventions40,44. Companies should strengthen the cultivation of employees’ occupational calling in regular safety management and cultural development activities to ensure the safe operation of trains. Additionally, when selecting railway employees, companies can use occupational calling as one of the selection criteria. Managers could incorporate questions regarding occupational calling in the tests and employ professional evaluation methods to determine whether applicants have the occupational calling3.

Conclusion

The present research confirms that workplace learning examination stress, as a hindrance job demand, has a negative impact on safety performance. It further confirmed that learning examination stress impairs employees’ sleep quality and triggers their shortcut motivation, thereby reducing the safety performance of railway employees. Our findings also suggest that occupational calling serves as a personal resource, which can mitigate the negative effects of learning examination stress. This study explored the negative aspects of workplace learning and how employees can effectively manage such stress. These insights provide new avenues for railway companies to enhance employee safety performance and reduce the occurrence of safety accidents.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request (majinfei@lnnu.edu.cn).

References

Kyriakidis, M., Pak, K. T. & Majumdar, A. Railway accidents caused by human error: historic analysis of UK railways, 1945 to 2012. Transp. Res. Rec J. Transp. Res. Board. 2476, 126–136 (2015).

Kyriakidis, M., Simanjuntak, S., Singh, S. & Majumdar, A. The indirect costs assessment of railway incidents and their relationship to human error-the case of signals passed at danger. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 9, 34–45 (2019).

Liu, Y., Ye, L. & Guo, M. The influence of occupational calling on safety performance among train drivers: the role of work engagement and perceived organizational support. Saf. Sci. 120, 374–382 (2019).

Liu, Y., Zhang, F., Liu, P., Liu, Y. & Liu, S. I’m energized to & i’m able to: A dual-path model of the influence of workplace spirituality on high-speed railway drivers’ safety performance. Saf. Sci. 159, 106033 (2023).

Manuti, A., Pastore, S., Scardigno, A. F., Giancaspro, M. L. & Morciano, D. Formal and informal learning in the workplace: a research review. Int. J. Train. Dev. 19, 1–17 (2015).

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F. & Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499 (2001).

Van Den Broeck, A., De Cuyper, N., De Witte, H. & Vansteenkiste, M. Not all job demands are equal: differentiating job hindrances and job challenges in the job Demands–Resources model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 19, 735–759 (2010).

Hutchinson, D., Luria, G., Pindek, S. & Spector, P. The effects of industry risk level on safety training outcomes: A meta-analysis of intervention studies. Saf. Sci. 152, 105594 (2022).

Ertan, Ş. S. & Şeşen, H. Positive organizational scholarship in healthcare: the impact of employee training on performance, turnover, and stress. J. Manag Organ. 28, 1301–1320 (2022).

Paulsson, K., Ivergård, T. & Hunt, B. Learning at work: competence development or competence-stress. Appl. Ergon. 36, 135–144 (2005).

Paulsson, K. & Sundin, L. Learning at work - a combination of experience based learning and theoretical education. Behav. Inf. Technol. 19, 181–188 (2000).

Laing, I. F. The Impact of Training and Development on Worker Performance and Productivity in Public Sector Organizations: A Case Study of Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority (Citeseer, 2009).

Pamungkas, R. A., Ruga, F. B. P. & Kusumapradja, R. Impact of physical workload and mental workload on nurse performance: A path analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Health Serv. IJNHS. 5, 219–225 (2022).

Okta, I. F. & Perdana, M. A. The effect of overtime and workload towards employee productivity with burnout as mediating Variable:(A Research at PT. RAPP). J. Manaj Dan. Ekon. Kreat. 2, 282–296 (2024).

Zhang, N., Liu, S., Pan, B. & Guo, M. Paternalistic leadership and safety participation of high-speed railway drivers in china: the mediating role of leader–member exchange. Front. Psychol. 12, 591670 (2021).

Ye, G. et al. Safety stressors and construction workers’ safety performance: the mediating role of ego depletion and self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 12, 818955 (2022).

Huang, J., Wang, Y. & You, X. The job Demands-Resources model and job burnout: the mediating role of personal resources. Curr. Psychol. 35, 562–569 (2016).

Phan, V., Nishioka, M., Beck, J. W. & Scholer, A. A. Goal progress velocity as a determinant of shortcut behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 108, 553 (2023).

Ouyang, D. et al. Effect of music intervention strategies on mitigating drivers’ negative emotion in post-congestion driving. in. IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV) 1–6 (IEEE, 2023). (2023).

Liu, Y., Ye, L. & Guo, M. Does formal mentoring impact safety performance? A study on Chinese high-speed rail operators. J. Saf. Res. 77, 46–55 (2021).

Jing, T. et al. Examining medical staff well-being through the application and extension of the job demands–resources model: a cross-sectional study. Behav. Sci. 13, 979 (2023).

Schleupner, R. & Kühnel, J. Fueling work engagement: the role of sleep, health, and overtime. Front. Public. Health. 9, 592850 (2021).

Gillet, N., Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T., Réveillère, C., Colombat, P. & Fouquereau, E. The effects of job demands on nurses’ burnout and presenteeism through sleep quality and relaxation. J. Clin. Nurs. 29, 583–592 (2020).

Mabry, J. E. et al. Unravelling the complexity of irregular shiftwork, fatigue and sleep health for commercial drivers and the associated implications for roadway safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 14780 (2022).

Shams, Z., Naderi, H. & Nassiri, H. Assessing the effect of inattention-related error and anger in driving on road accidents among Iranian heavy vehicle drivers. IATSS Res. 45, 210–217 (2021).

Fan, C. et al. Types, Risk Factors, Consequences, and Detection Methods of Train Driver Fatigue and Distraction. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 1–10 (2022). (2022).

Xia, N., Xie, Q., Hu, X., Wang, X. & Meng, H. A dual perspective on risk perception and its effect on safety behavior: A moderated mediation model of safety motivation, and supervisor’s and coworkers’ safety climate. Accid. Anal. Prev. 134, 105350 (2020).

Beck, J. W., Scholer, A. A. & Schmidt, A. M. Workload, risks, and goal framing as antecedents of shortcut behaviors. J. Bus. Psychol. 32, 421–440 (2017).

Zhou, J. L. & Lei, Y. A slim integrated with empirical study and network analysis for human error assessment in the railway driving process. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 204, 107148 (2020).

Cao, L., Liu, Y. & Chen, Y. An analysis of the current situation and development of unsafe psychology research. Saf. Secur. 41 (07), 51–57 (2020).

Tian, S. & Zhang, J. The Influence and Classification of Unsafe Psychology on the Safety Behavior of Miners. in 2nd International Conference on Humanities, Wisdom Education and Service Management (HWESM) 94–102 (Atlantis Press, 2023).) 94–102 (Atlantis Press, 2023). (2023).

Xu, S., Zhang, M., Xia, B. & Liu, J. Exploring construction workers’ attitudinal ambivalence: a system dynamics approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 30, 671–696 (2023).

Wong, T. K. M., Man, S. S. & Chan, A. H. S. Critical factors for the use or non-use of personal protective equipment amongst construction workers. Saf. Sci. 126, 104663 (2020).

Cao, L. & Liu, Y. Research on unsafe mentality and behavior scales of workers in confined space. China Saf. Sci. J. 30 (11), 37 (2020).

Van Wingerden, J., Derks, D. & Bakker, A. B. The impact of personal resources and job crafting interventions on work engagement and performance. Hum. Resour. Manage. 56, 51–67 (2017).

Bakker, A. B. & Van Wingerden, J. Do personal resources and strengths use increase work engagement? The effects of a training intervention. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 26, 20 (2021).

Bakker, A. B. & Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 273 (2017).

Rhee, S. Y., Hur, W. M. & Kim, M. The relationship of coworker incivility to job performance and the moderating role of Self-Efficacy and compassion at work: the job Demands-Resources (JD-R) approach. J. Bus. Psychol. 32, 711–726 (2017).

Niu, L., Li, X., Li, X. & Liu, J. The effects of job demands and job resources on miners’ unsafe Behavior—The mediating and moderating role of a sense of calling. Sustainability 14, 14294 (2022).

Zhou, J. How does COVID-19 pandemic strength influence work fatigue? The mediating role of occupational calling. Curr. Psychol. 43, 8358–8370 (2024).

Praskova, A., Creed, P. A. & Hood, M. Career identity and the complex mediating relationships between career preparatory actions and career progress markers. J. Vocat. Behav. 87, 145–153 (2015).

Jin, T., Zhou, Y. & Zhang, L. Job stressors and burnout among clinical nurses: a moderated mediation model of need for recovery and career calling. BMC Nurs. 22, 388 (2023).

Xu, Q. et al. The relationship between sense of calling and safety behavior among airline pilots: the role of harmonious safety passion and safety climate. Saf. Sci. 150, 105718 (2022).

Dobrow, S. R. Dynamics of calling: A longitudinal study of musicians. J. Organ. Behav. 34, 431–452 (2013).

Bedewy, D. & Gabriel, A. Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: the perception of academic stress scale. Health Psychol. Open. 2, 2055102915596714 (2015).

Cheng, X. & Lin, H. Mechanisms from academic stress to subjective Well-Being of Chinese adolescents: the roles of academic burnout and internet addiction. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 4183–4196 (2023).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, I. I. I., Monk, C. F., Berman, T. H., Kupfer, D. J. & S. R. & The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213 (1989).

Yang, Y. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of poor sleep quality among Chinese returning workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep. Med. 73, 47–52 (2020).

Zhang, H. S. et al. Sleep quality and health service utilization in Chinese general population: a cross-sectional study in dongguan, China. Sleep. Med. 27, 9–14 (2016).

Chang, Y., Lee, D., Lee, Y. & Chiu, M. Nurses’ perceived health and occupational burnout: A focus on sleep quality, workplace violence, and organizational culture. Int. Nurs. Rev. 71, 912–923 (2024).

Dik, B. J., Eldridge, B. M., Steger, M. F. & Duffy, R. D. Development and validation of the calling and vocation questionnaire (CVQ) and brief calling scale (BCS). J. Career Assess. 20, 242–263 (2012).

Chang, P. C., Rui, H. & Wu, T. Job autonomy and career commitment: A moderated mediation model of job crafting and sense of calling. Sage Open. 11, 21582440211004167 (2021).

Neal, A., Griffin, M. A. & Hart, P. M. The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behavior. Saf. Sci. 34, 99–109 (2000).

Neal, A. & Griffin, M. A. A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. J. Appl. Psychol. 91, 946 (2006).

Chau, N. et al. Contributions of occupational hazards and human factors in occupational injuries and their associations with job, age and type of injuries in railway workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 80, 517–525 (2007).

He, C., Hu, Z., Shen, Y. & Wu, C. Effects of demographic characteristics on safety climate and construction worker safety behavior. Sustainability 15, 10985 (2023).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction To Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Guilford, 2017).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879 (2003).

Mohammed, H. S., Mohammad, Z. A. E., Azer, S. Z. & Khallaf, S. M. Impact of in-service training program on nurses’ performance for minimizing chemotherapy extravasation. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP. 24, 3537 (2023).

Hosen, S. et al. Training & development, career development, and organizational commitment as the predictor of work performance. Heliyon 10, (2024).

Wu, G., Hu, Z. & Zheng, J. Role stress, job burnout, and job performance in construction project managers: the moderating role of career calling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16, 2394 (2019).

Hirschi, A., Keller, A. C. & Spurk, D. Calling as a double-edged sword for work-nonwork enrichment and conflict among older workers. J. Vocat. Behav. 114, 100–111 (2019).

Zhou, J., Zhang, J. W. & Xuan, X. Y. The curvilinear relationship between career calling and work fatigue: A moderated mediating model. Front. Psychol. 11, 583604 (2020).

Kirkman, B. L., Chen, G., Farh, J. L., Chen, Z. X. & Lowe, K. B. Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: A Cross-Level, Cross-Cultural examination. Acad. Manage. J. 52, 744–764 (2009).

Funding

This research was funded by the Special Fund for Basic Scientific Research of Liaoning Provincial Universities, grant number 20240056, project title: Prediction and Cognitive Enhancement Technology for Driver Risk Assessment Deviation at Unsignalized Intersections.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiahui Sun: Methodology, Formal analysis and investigation, Writing-original draft preparation, Writing-review and editing. Jinfei Ma: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-review and editing, Supervision. Lu Yang: Writing-review and editing, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Shuwen Yang: Methodology, Formal analysis and investigation. Zhuo Shen: Writing-original draft preparation. Zhiheng Zhou: Investigation, Resources. Lei Shi: Formal analysis and investigation, Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethics statement

The research procedure and data collection method were approved by the research ethics committee in the Liaoning Normal University (LL2024091).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, J., Ma, J., Yang, L. et al. Relationship between learning examination stress and safety performance among employees in Chinese railway workplace: the moderating role of occupational calling. Sci Rep 15, 26348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11235-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11235-z