Abstract

Emotional labor has been widely studied in organizational settings, but its impact on job burnout, particularly within educational contexts, remains underexplored. This study examines how emotional labor influences the distinct dimensions of job burnout—exhaustion and disengagement—with empathetic concern as a potential mediator and gender as a moderating factor. In this cross-sectional study conducted in both private and public colleges in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, data was collected from 1,128 college teachers using three validated scales: the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) to assess burnout, the Emotional Labor Questionnaire (ELQ) for emotional labor, and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) to evaluate the empathic concern. A path mediation analysis was employed to investigate the study hypotheses and explore the relationship between emotional labor, empathic concern, and burnout among college educators. Additionally, gender was examined as a moderating variable to assess whether the impact of emotional labor on burnout differed across male and female teachers. Emotional labor significantly predicted both exhaustion (β = 0.414, p < 0.001) and disengagement (β = 0.302, p = 0.003). Empathetic concern significantly mediated the relationship between emotional labor and exhaustion (indirect effect = 0.090, 95% CI = 0.03–0.125) but not between emotional labor and disengagement (indirect effect = 0.020, 95% CI = -0.010–0.060). Gender was found to significantly moderate the relationship between emotional labor and exhaustion (interaction effect = 0.133, 95% CI: 0.035 to 0.225), indicating that this association varies across male and female teachers, while no moderation effect was observed for disengagement. The significant mediation effect observed for exhaustion, but not disengagement, suggests that different strategies may be needed to address these distinct aspects of burnout. Additionally, the moderating role of gender in the emotional labor–exhaustion relationship highlights the importance of considering demographic factors when designing well-being interventions. These findings have important implications for developing targeted support strategies for teachers, particularly within the cultural context of Pakistan. Further research is needed to explore these dynamics over time and across different educational environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emotional and psychological demands placed on educators have become increasingly pronounced in recent decades1,2. Globally, teaching is recognized not only as an intellectually demanding profession but also as an emotionally intensive one, where educators are required to manage complex interpersonal dynamics daily3. In addition to imparting knowledge, teachers are expected to demonstrate empathy, maintain emotional equilibrium, and uphold institutional values within often under-resourced and overburdened educational environments4. These sustained emotional and interpersonal pressures contribute to a growing concern i.e., teacher burnout. Burnout is broadly understood as a work-related syndrome resulting from chronic exposure to emotional and interpersonal stressors5. It manifests in various forms, including physical and emotional exhaustion, depersonalization or cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy6. While the phenomenon has been widely documented, much of the existing scholarship has centered on Western educational systems, where institutional structures, cultural norms, and emotional display rules differ markedly from those in South Asian contexts. This geographic concentration of research leaves critical questions unanswered regarding how diverse socio-cultural conditions shape burnout. In Pakistan, educators navigate a distinct set of pressures that amplify emotional demands7,8. Teachers are not only academic figures but also cultural custodians and moral exemplars, expected to demonstrate compassion, patience, and authority. Cultural expectations rooted in collectivism, hierarchical social relations, and high power distance intensify the demand for emotional self-regulation9. Emotional expression in professional settings is governed by implicit display rules shaped by religious norms, societal expectations, and institutional traditions10,11. Consequently, teachers are required to engage in emotional labor—the process of regulating emotional expressions to meet job-related demands12, on a continual basis. However, despite the centrality of these emotional dynamics, empirical research on emotional labor and its psychological costs within Pakistani education remains sparse.

Moreover, while the relationship between emotional labour and burnout has been explored in several contexts, three critical gaps remain in the existing literature. First, most studies have focused on Western educational systems, with little empirical work on teacher burnout in South Asian contexts—especially using culturally appropriate frameworks such as the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI). Second, while emotional labor has been linked to burnout, the role of empathic concern as a mediating emotional resource remains underexamined in collectivist, emotionally regulated professional cultures. Third, despite growing interest in emotional labor, few studies have explored how cultural norms, institutional hierarchy, and religious display rules shape burnout experiences in education systems like Pakistan’s. This study addresses these interconnected gaps by examining the relationship between emotional labour and the two dimensions of burnout (exhaustion and disengagement) among college teachers in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Rawalpindi was chosen as the focal region for this study due to its diverse and representative educational landscape. As one of Pakistan’s largest urban districts and a major administrative hub within Punjab province, Rawalpindi includes a mix of public and private degree colleges, both co-educational and gender-segregated, operating under standardized national curricula and examination boards. This institutional structure mirrors broader national patterns of higher education across urban Pakistan. Furthermore, Rawalpindi’s teaching workforce reflects the demographic and cultural composition of the country’s college-level educators, allowing the findings to be analytically extended to comparable educational environments in other major urban centers. The study further investigates the mediating role of empathic concern and the moderating role of gender, while embedding the analysis within Pakistan’s socio-cultural framework. In doing so, this research contributes a culturally grounded, theory-driven perspective to understanding emotional strain and well-being in South Asian educational settings.

Literature review

Conceptualizing burnout in the educational context

Burnout is a psychological syndrome arising from prolonged and unmanaged occupational stress, especially prevalent in human service professions such as education, healthcare, and social work13. It has traditionally been conceptualized using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), which identifies three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (or cynicism), and reduced personal accomplishment5,6,14. Emotional exhaustion reflects the depletion of emotional and physical resources; depersonalization involves a cynical, emotionally distant attitude toward clients or students; and reduced personal accomplishment signifies a perceived decline in professional efficacy15. However, recent conceptual and psychometric critiques of the MBI have led to the development of alternative frameworks, particularly the OLBI16, which proposes a two-dimensional model focusing on exhaustion and disengagement. These dimensions are broadly aligned with the emotional and motivational components of burnout. Exhaustion captures the general experience of fatigue and resource depletion, both physical and emotional, while disengagement refers to a psychological distancing from work characterized by a lack of enthusiasm, detachment, and reduced commitment to job-related activities17. The adoption of the OLBI in this study is both theoretically and culturally motivated. Theoretically, OLBI addresses key limitations of the MBI, such as the ambiguity between depersonalization and disengagement and the empirical instability of the personal accomplishment scale17. Conceptually, OLBI allows for both positively and negatively worded items, reducing acquiescence bias and improving cross-cultural applicability18.

From a cultural psychology standpoint, the OLBI model is especially suitable for collectivist and high power-distance cultures, such as Pakistan’s, where personal accomplishment is often experienced collectively rather than individually, and expressions of depersonalization may be culturally suppressed due to social harmony norms19,20. In such settings, emotional suppression and avoidance of confrontation may mask overt signs of depersonalization, making disengagement a more reliable indicator of burnout-related withdrawal21. Additionally, educational environments impose unique emotional demands that elevate both exhaustion and disengagement. Teachers often perform significant emotional labor, suppressing personal emotions while displaying enthusiasm, empathy, and patience. When this emotional regulation is sustained over time without institutional support, it leads to emotional fatigue and detachment from professional purpose22,23. By adopting the exhaustion–disengagement model, the current study is better positioned to investigate the dual emotional and motivational pathways through which burnout unfolds.

Emotional labor: theoretical foundations and implications for teachers

The concept of emotional labor, first introduced by Hochschild (2002)12, refers to the regulation of emotional expressions in line with organizational or social expectations. This construct has been elaborated through contributions by Morris and Feldman (1996)24 and Grandey (2000)25, who identified three core strategies: surface acting, in which individuals suppress or fake emotional expressions without changing their inner feelings; deep acting, where internal emotional states are adjusted to match outward expressions; and the expression of naturally felt emotions, where internal emotions naturally align with expected behaviors24,25. In teaching, emotional labour is both continuous and complex. Teachers are expected to manage their emotions during interactions with students, often displaying encouragement, composure, and empathy regardless of their emotional state26,27. Numerous studies have demonstrated that surface acting is associated with adverse psychological outcomes, including emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and job dissatisfaction28,29,30. In contrast, deep acting and genuine emotional expression are linked to greater engagement, resilience, and professional efficacy31,32. These dynamics highlight the psychological costs and benefits of emotional regulation in the teaching profession.

While most of the literature on emotional labor in education focuses on school-level or service-based roles, college teaching, particularly in South Asian contexts, presents unique emotional challenges. In Pakistani colleges, instructors operate within hierarchical, exam-driven institutions where pedagogical autonomy may be constrained, and emotional display rules are influenced by cultural and religious expectations. Surface acting may occur when college teachers manage large class sizes, suppress frustration or fatigue, and maintain an authoritative demeanor. Deep acting may be engaged when attempting to genuinely embody moral or ethical roles expected of educators—such as being emotionally available mentors or “moral role models”—despite lacking institutional or emotional support. These pressures are amplified by the absence of structured training in emotional regulation or psychosocial support within higher education institutions. Compared to K-12 settings where more emphasis may be placed on pastoral care or student development, college educators are expected to regulate emotions with little formal preparation or recognition, making the psychological toll of emotional labor particularly acute in this segment.

These dynamics are particularly salient in the Pakistani higher education sector, where institutional support is limited and emotional expectations are shaped by cultural hierarchies and religious norms. For instance, Mushtaq, Saeed, et al. (2022)33 found that emotionally exhausted faculty in Pakistani universities often suppress their true feelings due to institutional and leadership pressures, which adversely impact their job satisfaction and psychological well-being. Similarly, Iqbal et al. (2024)34 highlighted that the absence of emotional support structures and training in emotional regulation contributes to increased stress and emotional detachment among academic staff. In collectivist, high power-distance societies like Pakistan, emotional suppression and conformity to authority are valued over emotional authenticity. Teachers must maintain composure, patience, and moral uprightness as dictated by institutional and socio-religious expectations. Yet, emotional labor studies have overwhelmingly focused on Western contexts, failing to capture the localized emotional ecology of South Asian institutions. This gap underscores the need for culturally situated research on how emotional regulation unfolds in Pakistani colleges.

Recent studies in second-language teaching contexts have emphasized the complexity of emotional labor in culturally loaded environments. For instance, Wu and Zeng (2025)35 validated a framework for teaching creatively under emotional pressure, showing how emotional labor is moderated by institutional support and cultural expectations. Similarly, Wu et al. (2023)36 conducted a bibliometric analysis that highlighted the growing attention to L2 teachers’ emotional regulation and stress management, suggesting that context-sensitive coping strategies are critical for maintaining psychological well-being in teaching professions. Yet, a similar empirical investigation remains sparse in Pakistan, where emotional labor is shaped by deeply embedded display norms, rigid power structures, and limited organizational support. These patterns underscore the need to examine emotional labour among college teachers within a culturally and institutionally grounded framework. By focusing on how Pakistani educators experience surface and deep acting within emotionally regulated and hierarchically structured institutions, the current study seeks to offer a culturally situated understanding of emotional labor. This framework not only contributes to teacher well-being literature but also addresses a significant theoretical and empirical void in burnout research within South Asian academic settings. Therefore, the current study hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1

A positive association exists between emotional labour and burnout among college teachers.

Empathic concern in the teaching profession

Empathic concern is a core component of empathy, representing the emotional capacity to experience compassion, care, and concern for others, especially those perceived to be in distress37. Within educational contexts, empathic concern is widely viewed as a desirable attribute, enabling teachers to build meaningful relationships with students and create emotionally responsive classroom environments31,38,39. However, growing evidence suggests that high empathic concern may also function as a double-edged sword in emotionally demanding professions40,41,42. While empathy promotes prosocial engagement, it may also contribute to emotional overextension, particularly when teachers are unable to act upon empathic impulses due to institutional constraints or lack of support43. In the context of emotional labour, empathic concern plays a complex role. It may buffer the negative effects of surface acting by fostering authentic connections. However, it may simultaneously heighten susceptibility to emotional exhaustion, especially in roles where emotional expression is both expected and heavily regulated31. Despite its critical relevance, empathic concern remains underrepresented in the literature on burnout and emotional labor, particularly within teaching professions in collectivist, resource-constrained societies. This duality can be further operationalized: empathic concern is most beneficial when teachers have supportive environments that allow them to act on compassionate impulses, facilitating engagement and well-being. However, when such support is lacking, empathic concern may become burdensome, leading to emotional fatigue or compassion-related stress, as shown in both education and care professions44,45.

The role of empathic concern as an intermediary between emotional labor and job burnout is underpinned by several theoretical frameworks, including the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model and the Conservation of Resources (COR) model46. The JD-R model posits that job demands, such as the requirement for emotional regulation, can precipitate burnout, especially when resources, such as empathic concern, are inadequate to counterbalance these demands47. The COR theory further postulates that individuals strive to obtain, retain, and protect their emotional resources. When empathic concern depletes these resources due to the emotional demands of the job, burnout can transpire, mainly manifesting as exhaustion48. The mediating role of empathic concern has been examined in various studies. For instance, research has demonstrated that elevated levels of empathic concern can exacerbate the emotional burden of emotional labor, leading to intensified burnout, particularly in high-stress professions like teaching49,50. However, other studies suggest that when managed effectively, empathic concern can also mitigate disengagement by fostering a sense of fulfillment and purpose in the job14,51. In the context of the current research, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2

Empathetic concern mediates the relationship between emotional labour and burnout (exhaustion and disengagement) among college teachers.

Cultural psychology and the emotional realities of teaching in Pakistan

The psychological dynamics of emotional labour and burnout are deeply embedded within the broader cultural context in which teachers operate. Drawing from cultural psychology, particularly Hofstede’s (2001) dimensions of collectivism and power distance20, Pakistani society places a strong emphasis on emotional restraint, deference to authority, and community harmony52. These cultural attributes shape emotional display rules and professional expectations within educational institutions53, where conformity and emotional control are often valued over authenticity54. In this context, teachers are not merely seen as academic facilitators but as moral exemplars and emotional anchors—individuals expected to model patience, composure, and care consistently. These expectations are magnified by hierarchical structures and cultural norms surrounding age and social status, which restrict open emotional expression and reinforce emotional suppression55, key mechanisms of emotional labor. Teachers must frequently suppress frustration, maintain decorum, and respond empathetically, even under institutional and interpersonal strain. This emotional burden is further compounded by structural pressures specific to Pakistan’s educational system, such as exam-driven curricula, overcrowded classrooms, and limited administrative support56. Cultural expectations position teachers as “second parents,” placing moral responsibility not only on their teaching competence but also on their emotional availability57. As a result, teachers may experience heightened empathic concern, driven not only by professional ethics but also by culturally ingrained obligations to nurture and guide students. While this may enhance emotional connection, it also increases vulnerability to exhaustion and disengagement, especially in the absence of support mechanisms58.

Comparative studies in collectivist societies reinforce these patterns. For example, Zeng et al. (2024)59 found that supportive work environments significantly shaped emotional experiences among Chinese L2 teachers. Wu and Zeng (2024)59 similarly observed that workplace support buffered the emotional toll of teaching. Although these studies are situated in East Asian contexts, they echo the broader theoretical principle that emotional labor, empathy, and burnout are culturally mediated—a dynamic highly relevant to the Pakistani setting. Despite these insights, the intersection of emotional labor, empathic concern, and cultural norms remains underexplored, particularly in South Asian teacher populations. Most existing studies are situated in Western frameworks and do not adequately account for cultural identity, social hierarchy, and moral expectations. By embedding these contextual elements into the study’s theoretical model, the present research offers a culturally situated lens to understand how burnout manifests within the emotional ecology of Pakistani education.

The moderating role of gender

While emotional labor and burnout have been extensively studied across various professional settings, increasing attention has been given to how gender shapes these emotional experiences, particularly in education. Theoretical frameworks suggest that gender norms influence how individuals regulate emotions, respond to stress, and perform emotional labor60,61. For example, societal expectations often position women as more emotionally expressive and nurturing, whereas men may be expected to suppress emotions and display resilience62. These gendered expectations can affect how emotional labor is internalized and how its consequences are experienced. Empirical studies have also revealed that female teachers often report higher levels of emotional labour and emotional exhaustion, potentially due to the alignment of professional expectations with gender norms63,64. Conversely, male teachers may be more vulnerable to disengagement or emotional suppression due to misalignment between professional emotional demands and masculine identity norms65,66. Despite these theoretical and empirical observations, few studies explicitly test gender as a moderating variable in the emotional labor–burnout relationship, especially within collectivist educational systems where emotional expression is culturally regulated. Given these dynamics, the current study includes gender as a moderating variable to investigate whether the effects of emotional labour on exhaustion and disengagement differ between male and female teachers. By incorporating gender moderation, the study seeks to offer a more nuanced understanding of how burnout unfolds in educational settings, shaped not only by psychological and emotional variables but also by demographic and sociocultural factors. Consequently, the study hypothesized:

Hypothesis 3

Gender moderates the relationship between emotional labour and exhaustion, with one gender group having a stronger relationship.

Hypothesis 4

Gender moderates the relationship between emotional labour and disengagement, with one gender group having a stronger relationship.

Study gaps and contribution

Taken together, the existing literature underscores the critical role of emotional labour and empathic concern in shaping teacher well-being. However, three key gaps remain. First, there is a limited body of empirical research on burnout among educators in South Asian contexts, where both cultural values and institutional structures differ significantly from Western systems. While some recent studies have examined burnout and emotional engagement among learners in collectivist educational environments35,67,68, there remains a lack of research exploring these emotional processes among teachers within such cultural frameworks. Second, few studies have investigated empathic concern as a mediating mechanism between emotional labour and burnout in teaching professions. Most research in this area has treated empathy as a peripheral or background variable without adequately examining its dual role as both a psychological resource and a potential vulnerability factor. Third, the influence of cultural norms on emotional regulation in educational settings remains largely theoretical and underexplored in empirical terms. Although emerging research highlights how supportive work environments, emotional display expectations, and cultural values affect emotional experiences in teaching35,59,67, such findings have yet to be extended to the Pakistani context, where unique socio-religious and hierarchical expectations govern emotional expression. By integrating emotional and cultural perspectives, this study contributes not only to the literature on teacher burnout and emotional labor but also to a broader understanding of how culture shapes emotional experiences and well-being in professional life. In doing so, it responds to calls for contextually grounded, theory-driven research in educational psychology.

Methods

Data source and study design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted between September and December 2023, targeting college educators across private and public institutions in Rawalpindi City, Pakistan. Given the diversity of the educational institutions and the potential variability in teaching environments, including teachers from both private and public sectors ensured a comprehensive understanding of the research phenomena across different educational settings. A stratified random sampling method was employed to ensure that teachers from both public and private colleges were adequately represented. The colleges were first stratified by type (public and private), and then a random selection of teachers was made within each stratum. This approach was chosen to minimize sampling bias and to ensure that the sample accurately reflected the broader population of college teachers in Rawalpindi. The study initially aimed to reach all college teachers within Rawalpindi City, resulting in a target sample size of 1,128 teachers. The participants included teachers of varying ages, genders, educational backgrounds, and years of teaching experience, providing a diverse cross-section of the teaching population in the city. Participation in the study was voluntary, and all participants provided informed consent before inclusion. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire distributed to the selected college teachers. The questionnaire included validated scales measuring the study variables, including job burnout, emotional labour, and empathetic concern. The questionnaire was administered on paper and online, depending on the participants’ preferences. Data collection took place over two months, ensuring that all targeted participants had the opportunity to respond.

The determination of the sample size for this study was guided by statistical considerations aimed at ensuring the validity and generalizability of the findings. Given the large population of college teachers in Rawalpindi City, the Cochran formula for sample size determination in large populations was employed, which yielded a minimum sample size of 384 participants to achieve the desired confidence level and margin of error. However, the sample size was increased considering the need for a more representative sample due to potential non-responses and the diversity within the population (across different colleges and teaching disciplines). A final sample size of 1,128 teachers was targeted to account for stratified sampling, potential non-response, and increased precision. The study flow chart is presented in Fig. 1.

The eligibility criteria for the participants’ selection were as follows:

Inclusion Criteria: (i) participants currently employed at a public or private college in Rawalpindi City, (ii) Teachers with a minimum of one year of teaching experience to ensure familiarity with the teaching environment, and (iii) willingness to participate in the study and provide informed consent.

Exclusion Criteria: (i) participants on long-term leave or sabbatical during the data collection period, (ii) participants with less than one year of teaching experience, as they may not have fully acclimated to the teaching profession, (iii) participants diagnosed with any mental disability or currently undergoing treatment or counseling sessions for mental health issues (self-reported), and (iv) Incomplete questionnaires were excluded from the final analysis to maintain the integrity of the data.

Measuring tools

Burnout

To assess burnout among our study population, the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI)16,18 was adopted, which is designed to measure burnout through two primary dimensions: Exhaustion (measures the general feelings of being drained of physical, emotional, and cognitive energy) and Disengagement (measures the sense of cynicism, detachment, or lack of involvement in one’s job) (Fig. 2). The OLBI consists of 16 items, each dimension measured by 8 items, with responses measured on a 4-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Elevated scores on the exhaustion dimension indicate heightened levels of fatigue associated with burnout, whereas increased scores on the disengagement dimension reflect a more pronounced sense of alienation from the workplace. Some items are reverse-coded to mitigate response bias. Once reverse-scored items are considered, each dimension’s scores are determined individually by averaging the item scores for each dimension. The OLBI has been validated across multiple cultures and languages, making it a versatile tool for international research69,70,71.

Emotional labour

We employed the Emotional Labour Questionnaire (ELQ) developed by Diefendorff, Croyle, and Gosserand (2005)72 to assess emotional labour among our participants. This instrument is structured around three distinct dimensions: surface acting, deep acting, and naturally felt emotions (Fig. 3). The scale comprises 15 items, with responses recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The scale is scored by calculating each dimension’s mean or sum of the responses. Higher scores on the surface acting dimension indicate a greater tendency to feign emotions, whereas higher scores on the deep acting dimension reflect a more substantial effort to experience the emotions required by the job genuinely. Additionally, higher scores on the naturally felt emotions dimension suggest that the emotions expressed in the workplace are more authentic. The scale has been extensively utilized in the fields of organizational psychology and vocational behavior research to investigate the significance of emotional labor across diverse professional contexts, such as customer service, healthcare, education, and management73,74,75.

Empathetic concern

In the present study, we evaluated the empathic concerns utilizing the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), a measure developed by Davis (1983)37. However, we specifically utilized the Empathic Concern subscale, as it directly quantifies the emotional dimensions of empathy that align most closely with our research objectives. Our emphasis informed this decision on comprehending the compassionate and sympathetic responses exhibited by individuals within our sample, which are fundamentally integral to the construct of empathic concern. This subscale comprises seven items evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale, from “Does not describe me well” to “Describes me very well."These items are intended to elicit emotional responses, including sympathy, compassion, and concern for the well-being of others. Higher scores on empathic concern indicate an increased propensity for empathic feelings and concern for others. This subscale is commonly utilized in psychological and social research to examine empathy across diverse populations, including healthcare professionals, educators, and social workers76,77,78.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 28 and the PROCESS macro for mediation analysis. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was applied to ensure the data’s suitability for factor analysis, while Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity verified that the correlation matrix was appropriate for this analysis. The Common Method Bias (CMB) test assessed measurement bias. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to confirm that the measurement model adhered to established fit criteria. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were examined to explore the relationships between burnout (exhaustion & disengagement), emotional labour, and empathetic concern. A path mediation analysis was utilized to investigate the direct and indirect effects among the study constructs under investigation. Additionally, gender was tested as a moderating variable to assess whether the relationship between emotional labour and each burnout dimension differed across male and female teachers. The bias-corrected bootstrap approach was applied to test the mediation and moderation hypotheses on a sample of 5000.

Results

Common method bias (CMB)

The method utilized for data collection in the present survey was based on self-reported measures. Therefore, recognizing these methodologies can introduce a CMB, which may impact the study findings. In response to this issue, we employed Harman’s single-factor test method to analyze the potential presence of CMB in the dataset. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) score, estimated at 0.814 (at p < 0.001), suggests that the data is appropriate for conducting exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The principal component analysis (PCA) performed on the variable measurement items indicated that the initial principal component explained approximately 31.08% of the overall variation, failing to meet the threshold value of 40%. This implies that the deviation of measurement bias did not substantially influence the study outcomes.

Demographic analysis

The demographic analysis of the study participants exhibited a diverse group of college teachers (Table 1). Most participants were female (61.08%), while males constituted 39.01% of the sample. Age distribution shows that 43.17% of the participants are between 36 and 45 years, 34.31% in the 25–35 years range, and 22.52% aged between 46 and 60. Regarding marital status, most participants were married (61.97%), with 26.06% single and 11.97% divorced or widowed. Regarding educational qualifications, more than half hold a Master’s degree (53.37%), 31.83% have a Bachelor’s degree, and 14.80% possess a PhD. Teaching experience varies, with the largest group having 11–20 years of experience (40.34%), followed by 1–10 years (35.99%) and 21–30 years (23.67%). The current participants rank showed that 35.55% were Lecturers, 31.47% were Assistant Professors, 23.67% were Associate Professors, and 9.31% were Full Professors. Most participants worked full-time (65.96%), 24.11% were part-time, and 9.93% were adjunct faculty members.

Convergent and discriminant validity analysis

The findings in Table 2 indicate that the constructs measured in the present research (exhaustion, disengagement, empathetic concern, and emotional labour) are reliable and valid. The high composite reliability and average variance extracted values suggested that the items used to measure each construct are well-correlated, and the constructs effectively capture the intended latent variables. The high mean scores for empathetic concern and emotional labour suggest that these are particularly salient in our population, while the slightly lower means for exhaustion and disengagement indicate varying levels of burnout-related symptoms among participants.

Model fit analysis

Table 3 demonstrates the results of the model fit analysis for the study constructs — exhaustion, disengagement, empathetic concern, and emotional labour. The outcomes exhibited that all models exhibited good fit indices. The \(\:{\chi\:}^{2}\)/df values were below the commonly accepted threshold of 3, ranging from 1.22 to 1.54. The RMSEA values were all within the acceptable range, falling between 0.04 and 0.05. The SRMR and the CFI values indicated a good model fit, with SRMR values at 0.03 to 0.04 and CFI values ranging from 0.93 to 0.95. The NFI and TLI indices were similarly high, further supporting the adequacy of the model fit across all constructs.

Bivariate correlation analysis

Table 4 presents the bivariate correlation analysis among the study constructs. Exhaustion was strongly correlated with disengagement (r = 0.584, p < 0.001) and moderately with empathetic concern (r = 0.366, p < 0.001) and emotional labour (r = 0.527, p < 0.001). Disengagement was also significantly correlated with empathetic concern (r = 0.19, p < 0.05) and emotional labor (r = 0.386, p < 0.01). Empathetic concern moderately correlated with emotional labour (r = 0.411, p < 0.01).

Path analysis

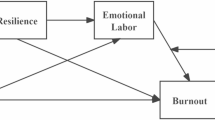

Table 5 presents the results of path mediation (empathetic concern) and moderation (gender) analysis results of the study constructs. The results revealed that emotional labor significantly predicted both exhaustion (effect size = 0.414, p < 0.001) and disengagement (effect size = 0.302, p = 0.003). Emotional labour also significantly predicted empathetic concern (effect size = 0.286, p = 0.010). In terms of the mediator, empathetic concern significantly predicted exhaustion (effect size = 0.313, p < 0.001) but did not significantly predict disengagement (effect size = 0.07, p = 0.081). The indirect effect of emotional labour on exhaustion through empathetic concern was supported (effect size = 0.090, 95% CI = 0.03–0.125), while the indirect effect on disengagement through empathetic concern was not supported (effect size = 0.020, 95% CI = −0.010−0.060) (Fig. 4). Regarding moderation, gender significantly moderates the relationship between emotional labour and exhaustion (interaction effect = 0.133, 95% CI: 0.035 to 0.225), suggesting that the strength of this relationship differs between male and female teachers. In contrast, no significant moderating effect of gender was found for the emotional labor–disengagement pathway (interaction effect = 0.049, 95% CI: −0.013 to 0.127). These results indicate that while both dimensions of burnout are influenced by emotional labor, exhaustion is more sensitive to individual differences in empathic concern and gender, whereas disengagement appears less affected by these moderating and mediating mechanisms.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the role of empathetic concern as a mediator in the relationship between emotional labour (the independent variable) and job burnout (the dependent variable), assessed using its two distinct dimensions: exhaustion and disengagement. By assessing these dimensions separately, the study aimed to better understand how emotional labor impacts burnout. Burnout is not a uniform construct; it manifests differently depending on the emotional and psychological challenges educators face. Our findings indicated that emotional labour significantly predicts both exhaustion and disengagement but with a more pronounced effect on exhaustion. Notably, emotional labour also significantly predicted empathetic concern, which, in turn, significantly mediates the relationship between emotional labour and exhaustion but not disengagement. This nuanced understanding of the mediating effects on each dimension of burnout is crucial for developing targeted interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of emotional labor on educators.

In the preliminary phase of our analysis, a significant direct effect of emotional labour on exhaustion was observed. This association indicates that college educators who frequently engage in emotional labour are more likely to experience elevated levels of emotional fatigue. Similar relationships have been documented across various professional settings, with studies by Yang (2011)79, Kariou et al. (2021)80, Bayram et al. (2012)81, Bodenheimer & Shuster (2020)4, and Yilmaz et al. (2015)82, consistently reporting strong links between emotional labor and burnout, particularly the exhaustion component—within the education sector. In the specific context of Pakistani college educators, these effects may be intensified by cultural expectations that require teachers to maintain respectfulness and emotional restraint in their interactions. These sociocultural imperatives, combined with structural challenges such as large class sizes and limited institutional resources, likely heighten the emotional burden of teaching83,84. As a result, sustained engagement in emotional labour may substantially increase exhaustion in such environments.

Leading from the observed direct relationships, it became essential to explore whether these effects were purely linear or shaped by underlying psychological mechanisms. Accordingly, we examined the role of empathetic concern as a potential mediator between emotional labour and burnout. While often regarded as a beneficial interpersonal trait, empathic concern in emotionally demanding professions like teaching can have both supportive and taxing effects—a dynamic often described as a double-edged sword85,86. Cultivating deep emotional bonds with students may enhance relational outcomes but can also significantly elevate emotional strain40,87. Our findings revealed that empathetic concern significantly mediated the emotional labor–exhaustion relationship, reinforcing the view that emotional engagement, while prosocial, contributes to heightened emotional load and fatigue. This result aligns with prior research on the costs of empathy in helping professions, where emotional overinvestment can lead to burnout88,89. Within the Pakistani educational context, the burden of empathic responsibility may be amplified by socio-cultural expectations that position teachers as moral exemplars and emotional caregivers. As a result, high empathic concern—especially when unsupported by institutional structures—can exacerbate emotional exhaustion. These findings lend support to the notion that empathic strain, not just cognitive demands, can be a salient predictor of burnout when emotional labour is sustained over time.

Building on this, we turned our attention to the second core dimension of burnout: disengagement. While exhaustion captures emotional and physiological depletion, disengagement reflects a motivational and psychological withdrawal from work. Our analysis revealed a positive association between emotional labour and disengagement; however, this relationship was notably weaker than that observed for exhaustion. Interestingly, unlike the exhaustion pathway, empathetic concern did not significantly mediate the link between emotional labour and disengagement. This divergence carries theoretical significance. According to the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) framework16,90, exhaustion and disengagement stem from distinct psychological processes—emotional overextension drives the former, whereas cognitive withdrawal and diminished perceived work value underpin the latter16,91. Although emotional labor appears to deplete psychological resources leading to exhaustion, its effect on disengagement seems more influenced by organizational and structural dynamics22,92,93. Educators who experience limited autonomy, lack recognition, or feel a misalignment with institutional goals may begin to mentally detach, even while remaining emotionally engaged. Such patterns are echoed in previous research by Brotheridge and Grandey (2002)89, Leiter and Maslach (1988)94, and Zapf et al. (2001)95, which indicate that disengagement is often a response to perceived inefficacy and low job satisfaction rather than emotional fatigue alone. In our setting, although empathic concern intensifies the emotional burden contributing to exhaustion, it appears unrelated to disengagement—suggesting that the latter is more closely tied to motivational disillusionment and systemic constraints than to emotional investment. In the Pakistani college context, such detachment may be exacerbated by structural issues such as lack of participation in institutional decision-making, overreliance on lecture-based instruction with limited pedagogical autonomy, and rigid bureaucratic hierarchies that minimize professional agency. Furthermore, limited access to meaningful professional development or recognition systems may contribute to a diminished sense of purpose, thereby reinforcing disengagement even in emotionally invested educators.

The current study further advanced the model by incorporating gender as a moderating variable in the emotional labor–burnout relationship. Results showed that gender significantly moderated the relationship between emotional labour and exhaustion, but not disengagement. Specifically, emotional labour had a stronger effect on exhaustion for male teachers, indicating that they may experience more intense emotional strain under conditions of high emotional labour. This finding is particularly important given that most prior research has focused on female-dominated samples and has often assumed emotional labor burdens to be heavier for women. Our results, however, suggested that male teachers may be less emotionally equipped or socially supported to cope with persistent emotional regulation demands in educational settings. Theoretically, this outcome aligns with gender role socialization theory and the expectations imposed by emotional display rules60,61. In collectivist cultures like Pakistan, where emotional restraint and hierarchical respect are culturally ingrained, male teachers may face dual pressures: to uphold authority and to exhibit patience and empathy. This emotional dissonance, being expected to express warmth and control simultaneously, may be less aligned with traditional masculine roles, resulting in increased emotional fatigue.

Conversely, female teachers may be more socially conditioned to navigate emotional demands, aligning with societal expectations of nurturance and relational labor. This alignment may render emotional labor comparatively less psychologically burdensome for women, particularly regarding exhaustion. The lack of a moderating effect for disengagement, however, implies that motivational detachment from work is likely shaped by broader institutional, organizational, or systemic factors rather than individual or gender-specific emotional dynamics96,97. Disengagement, in this sense, may represent a form of cognitive withdrawal that affects educators more uniformly—especially in contexts marked by rigid curricula, limited professional autonomy, and insufficient recognition98. This reinforces the distinction between exhaustion as an emotional outcome and disengagement as a motivational one, as posited by the OLBI framework99. These findings align with prior research suggesting that emotional labor affects burnout differently across gender lines but also contribute new insights by demonstrating this effect in a non-Western, under-researched context. For instance, studies by Kinman et al. (2011)100 and Chang (2009)101 have documented heightened burnout in female teachers, but few have systematically tested gender moderation using structural models in collectivist societies. Our results thus offer important cross-cultural evidence that challenges assumptions about gender and emotional resilience.

Within the educational landscape of Pakistan, where emotional labour is deeply embedded in teaching practice, the minimal mediating effect of empathetic concern on disengagement may indicate that educators are able to remain emotionally connected to their work without necessarily feeling psychologically detached. This resilience could stem from strong cultural and communal support systems that help sustain teachers’ professional commitment, despite the substantial emotional demands of their roles. These findings highlight the importance of analyzing burnout’s dimensions independently, as different facets of emotional labor and empathic concern appear to influence exhaustion and disengagement in distinct ways.

Implications

The outcomes derived from this research hold substantial relevance for educational establishments, particularly within socio-cultural contexts like Pakistan, where emotional regulation is a normative expectation in professional roles such as teaching. The pronounced influence of emotional labour on both exhaustion and disengagement underscores the urgent need for schools, colleges, and teacher training institutes to acknowledge and address the emotional demands faced by educators formally. Institutional support frameworks should be designed to include emotion regulation training, peer support networks, and routine access to school-based counseling or psychological services. These could be integrated into Continuous Professional Development (CPD) programs led by provincial education departments to ensure system-wide reach. The significant mediatory role of empathetic concern in the emotional labor–exhaustion relationship also points to the necessity of incorporating empathy regulation and emotional intelligence modules into teacher education curricula. Such modules should equip educators with tools to manage the emotional burden of empathic engagement without compromising their well-being. These interventions could be embedded within existing in-service training frameworks, particularly in alignment with policies outlined in the National Education Policy of Pakistan and ongoing school improvement initiatives.

The finding that gender moderates the emotional labour–exhaustion relationship further calls for gender-sensitive intervention strategies. For instance, well-being programs should consider the differing ways male and female educators process emotional strain, possibly offering targeted coaching or support groups that reflect these differences. Additionally, school administrators and policymakers should consider integrating burnout screening tools into teacher performance evaluations or staff well-being audits, particularly for male educators who may be socially discouraged from expressing emotional fatigue.

Furthermore, addressing disengagement requires system-level changes beyond individual emotional training. Policies aimed at enhancing teacher autonomy, strengthening recognition mechanisms, and providing meaningful professional growth pathways are critical to restoring motivational engagement. This includes revisiting evaluation systems to value emotional investment and creating feedback-rich environments where teachers feel heard and supported. Overall, these findings advocate for a holistic, multi-tiered approach to emotional well-being in education, one that combines psychological tools with systemic reform. Future policy development should integrate emotional labor awareness into teacher support systems, acknowledging both the psychological complexity and the gendered realities of the teaching profession.

Limitations

This investigation is constrained by several limitations that warrant recognition. First, the cross-sectional research design impedes the establishment of causal links among study variables, indicating a necessity for longitudinal or mixed-method research designs for capturing the temporal dynamics and deeper contextual insights into emotional labor and burnout in educational settings. Second, the participant sample exhibited a higher representation of female teachers, which may have influenced the findings—particularly given the significant gender-based moderation effect observed for emotional exhaustion. This imbalance could restrict the extrapolation of results to more gender-balanced or male-dominated populations, where emotional labor dynamics may differ. Also, the unequal group sizes may have introduced bias or reduced statistical power in detecting moderation effects, particularly among the underrepresented male subgroup. Future studies should aim to achieve a more balanced gender distribution to enhance the generalizability and robustness of results across demographic subgroups. Moreover, the study’s focus on college educators in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, may limit the applicability of the findings to other regions or educational contexts that operate within distinct cultural, social, or institutional frameworks. Lastly, while this study emphasized emotional labor and empathic concern, it did not account for other key antecedents of burnout—such as job demands, organizational climate, and individual coping mechanisms—all of which may interact with emotional processes in meaningful ways. Future research endeavors should integrate these contextual and psychological variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of burnout in educational settings.

Conclusion

This study advances the understanding of how emotional labour and empathic concern jointly shape burnout outcomes in the context of South Asian higher education. By disentangling the dual dimensions of burnout—exhaustion and disengagement—and examining their distinct associations with emotional labour, the research offers a nuanced perspective on the emotional demands faced by college educators. The identification of empathic concern as a significant mediator in the exhaustion pathway adds conceptual depth to the emotional labor literature, illustrating how prosocial traits can both protect and burden educators in emotionally regulated environments. Furthermore, the observed gender differences in emotional strain highlight the relevance of socio-cultural display norms in shaping burnout responses and underscore the need for context-sensitive, gender-aware strategies in institutional well-being initiatives.

Beyond its empirical contributions, the study offers practical implications for educational policymakers and administrators. Strategies to mitigate emotional labor, such as professional development in emotional regulation, institutional recognition systems, and peer support mechanisms—may be instrumental in sustaining teacher engagement and psychological resilience. In doing so, the research not only informs burnout prevention efforts but also contributes to a culturally grounded model of educator well-being, attuned to the unique socio-emotional demands of teaching in collectivist, resource-constrained academic settings.

Data availability

“The raw data supporting this study’s findings are available upon reasonable request from the author, Muhammad Nasir Khan (dr.ir.mnkhan@gcu.edu.pk).”

References

Crawford, N. et al. Emotional labour demands in enabling education: A qualitative exploration of the unique challenges and protective factors. Student Success. 9 (1), 23–33 (2018).

Tuxford, L. M. & Bradley, G. L. Emotional job demands and emotional exhaustion in teachers. Educ. Psychol.35(8), 1006–1024 (2015).

Wu, H., Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. How burnout, resilience, and engagement interplay among EFL learners: A mixed-methods investigation in the Chinese senior high school context. (2024).

Bodenheimer, G. & Shuster, S. M. Emotional labour, teaching and burnout: investigating complex relationships. Educ. Res. 62 (1), 63–76 (2020).

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E. & Leiter, M. P. Maslach burnout inventory. Scarecrow Education. (1997).

Leiter, M. P. & Maslach, C. Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burn. Res.3(4), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2016.09.001 (2016).

Shaheen, F. & Mahmood, D. R. N. Exploring the level of emotional burnout among public school teachers. Sindh Univ. J. Educ. 44(1), (2015).

Yusoff, R. M. & Khan, F. Stress and burnout in the higher education sector in pakistan: A systematic review of literature. Res. J. Recent. Sci. ISSN. 2277, 2502 (2013).

McInerney, D. M. The motivational roles of cultural differences and cultural identity in self-regulated learning. In Motivation and self-regulated learning 369–400 (Routledge, 2012).

Byrne, C. J., Morton, D. M. & Dahling, J. J. Spirituality, religion, and emotional labor in the workplace. J. Manag Spiritual. Relig. 8 (4), 299–315 (2011).

Morgan, J. & Krone, K. Bending the rules of professional display: Emotional improvisation in caregiver performances. J. Appl. Commun. Res.29(4), 317–340 (2001).

Hochschild, A. Emotional labour. Gend. A Sociol. Read. 192–196 (2002).

Maslach, C. & Leiter, M. P. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 15 (2), 103–111 (2016).

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B. & Leiter, M. P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52 (1), 397–422 (2001).

Demerouti, E. & Bakker, A. B. The Oldenburg burnout inventory: A good alternative to measure burnout and engagement. Handb. Stress Burn. Heal. Care65(7), 1–25 (2008).

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F. & Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol.86(3), 499 (2001).

Reis, D., Xanthopoulou, D. & Tsaousis, I. Measuring job and academic burnout with the Oldenburg burnout inventory (OLBI): factorial invariance across samples and countries. Burn Res. 2 (1), 8–18 (2015).

Halbesleben, J. R. B. & Demerouti, E. The construct validity of an alternative measure of burnout: Investigating the English translation of the Oldenburg burnout inventory. Work Stress19(3), 208–220 (2005).

Singelis, T. M., Triandis, H. C., Bhawuk, D. P. S. & Gelfand, M. J. Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: A theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-cultural Res. 29 (3), 240–275 (1995).

Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Readings Psychol. Cult. 2 (1), 8 (2011).

Mills, L. B. & Huebner, E. S. A prospective study of personality characteristics, occupational stressors, and burnout among school psychology practitioners. J. Sch. Psychol.36(1), 103–120 (1998).

Wang, H. & Burić, I. A diary investigation of teachers’ emotional labor for negative emotions: its associations with perceived student disengagement and emotional exhaustion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 127, 104117 (2023).

Vinahapsari, C. A., Ibrahim, H. I. & Kimpah, J. The role of lecturers’ engagement in higher education institutions: perceived organizational support as moderator. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 16, (2024).

Morris, J. A. & Feldman, D. C. The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Acad. Manag Rev. 21 (4), 986–1010 (1996).

Grandey, A. A. Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 5 (1), 95 (2000).

Constanti, P. & Gibbs, P. Higher education teachers and emotional labour. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 18 (4), 243–249 (2004).

Rehman, S., Addas, A., Rehman, E. & Khan, M. N. The mediating roles of self-compassion and emotion regulation in the relationship between psychological resilience and mental health among college teachers. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S491822 (2024).

Yikilmaz, I., Surucu, L., Maslakci, A., Dalmis, A. B. & Toros, E. Exploring the relationship between surface acting, job stress, and emotional exhaustion in health professionals: the moderating role of LMX. Behav. Sci. (Basel). 14 (8), 637 (2024).

Fritz, J. M. H. & Omdahl, B. L. Reduced job satisfaction, diminished commitment, and workplace cynicism as outcomes of negative work relationships. Probl. Relationships Work. 131–151, (2006).

Jeung, D. Y., Kim, C. & Chang, S. J. Emotional labor and burnout: A review of the literature. Yonsei Med. J. 59 (2), 187–193 (2018).

Wróbel, M. Can empathy lead to emotional exhaustion in teachers? The mediating role of emotional labor. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health26, 581–592 (2013).

Akın, U., Aydın, İ, Erdoğan, Ç. & Demirkasımoğlu, N. Emotional labor and burnout among Turkish primary school teachers. Aust. Educ. Res.41, 155–169 (2014).

Saeed, A., Pervez, R. & Mushtaq, S. Impact of despotic leadership with mediation of emotional exhaustion on life satisfaction and organizational career growth: moderating role of emotional intelligence. J. Manag Sci. 16 (4), 21–45 (2022).

Iqbal, J. et al. The moderating effect of psychological capital on the relationship between leader’s emotional labour strategies and workplace Behaviour-Related outcomes. Migr. Lett. 21, 1068–1095 (2024).

Wu, H. & Zeng, Y. Validating the second Language teaching for creativity scale (L2TCS) and applying it to identify Chinese college L2 teachers’ latent profiles. Think. Ski .Creat. 101781, (2025).

Wu, H., Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. What do we know about L2 teachers’ emotion regulation? A bibliometric analysis of the pertinent literature, in Forum for Linguistic Studies (Transferred), Vol. 5, no. 3, p. 2012. (2023).

Davis, M. H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.44(1), 113 (1983).

Batson, C. D., Eklund, J. H., Chermok, V. L., Hoyt, J. L. & Ortiz, B. G. An additional antecedent of empathic concern: Valuing the welfare of the person in need. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.93(1), 65 (2007).

Toomey, E. C., Rudolph, C. W. & Zacher, H. Age-conditional effects of political skill and empathy on emotional labor: an experience sampling study. Work Aging Retire. 7 (1), 46–60 (2021).

Thomas, J. T. & Otis, M. D. Intrapsychic correlates of professional quality of life: mindfulness, empathy, and emotional separation. J. Soc. Social Work Res. 1 (2), 83–98 (2010).

Cadet, F. & Sainfort, F. Service quality in health care: Empathy as a double-edged sword in the physician–patient relationship. Int. J. Pharm. Healthc. Mark.17(1), 115–131 (2023).

Lai, L. et al. The double-edged-sword effect of empathy: The secondary traumatic stress and vicarious posttraumatic growth of psychological hotline counselors during the outbreak of COVID-19. Acta Psychol. Sin.53(9), 992 (2021).

Kim, H. Empathy in the Early Childhood Classroom: Exploring Teachers’ Perceptions, Understanding and Practices (Indiana University, 2017).

Bakker, A. B. & De Vries, J. D. Job Demands–Resources theory and self-regulation: new explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping. 34 (1), 1–21 (2021).

Garcia, R. M. Understanding Burnout Through the Lens of Teachers During the COVID-19 Pandemic (A Phenomenological Study, 2023).

Bauer, G. F., Hämmig, O., Schaufeli, W. B. & Taris, T. W. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. Bridg Occup. Organ. public. Heal Transdiscipl. approach 43–68 (2014).

Taris, T. W. & Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model. Wiley Blackwell Handb. Psychol. Occup. Saf. Work Heal, pp. 155–180 (2015).

Lin, S. H. J., Poulton, E. C., Tu, M. H. & Xu, M. The consequences of empathic concern for the actors themselves: Understanding empathic concern through conservation of resources and work-home resources perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol.107(10), 1843 (2022).

Brotheridge, C. M. & Lee, R. T. Testing a conservation of resources model of the dynamics of emotional labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol.7(1), 57 (2002).

Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R. & Sutton, R. E. Emotional transmission in the classroom: Exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol.101(3), 705 (2009).

Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O. & Baumert, J. Teachers’ occupational well-being and quality of instruction: The important role of self-regulatory patterns. J. Educ. Psychol.100(3), 702 (2008).

Akhtar, A. S. The politics of common sense: State, society and culture in Pakistan (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Gulzar, S., Din, F. U., Noor, S. & Anwar, M. M. Exploring how cultural backgrounds influence teaching methods, student expectations, and educational success across different societies. Bull. Bus. Econ. 13 (3), 211–218 (2024).

Haidri, A. R. Exploring the challenge of cultivating a peaceful culture in higher education institutions of Pakistan. Magna Cart Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2 (1), 25–33 (2024).

Ullah, H. & Ali, J. Schools and families: Reproduction of class hierarchies through education in Pakistan. Pakistan J. Criminol, 10(3), (2018).

Shaikh, N., Khan, N. & Ahmed, U. Challenges regarding implementation of communicative Language teaching at higher secondary level in pakistan: ELT teachers’ perspectives. Voyag. J. Educ. Stud. 4(2), 255–271 (2024).

Ahmad, S. M. A sociological study of parent-teacher relations in public secondary schools in Pakistan (University of Nottingham, 2010).

Warren, C. A. Conflicts and contradictions: Conceptions of empathy and the work of good-intentioned early career white female teachers. Urban Educ.50(5), 572–600 (2015).

Zeng, Y., Yu, J., Wu, H. & Liu, W. Exploring the impact of a supportive work environment on Chinese L2 teachers’ emotions: A partial least squares-SEM approach. Behav. Sci. (Basel). 14 (5), 370 (2024).

Brody, L. R. & Hall, J. A. Gender and emotion in context. Handb. Emot. 3, 395–408 (2008).

Hochschild, A. R. The sociology of emotion as a way of seeing. In Emotions in social life 31–44 (Routledge, 2002).

Guy, M. E. & Newman, M. A. Women’s jobs, men’s jobs: sex segregation and emotional labor. Public. Adm. Rev. 64 (3), 289–298 (2004).

Kenworthy, J., Fay, C., Frame, M. & Petree, R. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between emotional dissonance and emotional exhaustion. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 44 (2), 94–105 (2014).

Lawless, B. Documenting a labor of love: Emotional labor as academic labor. Rev. Commun.18(2), 85–97 (2018).

Baker, E. P. Disproportionality and Disparities among Adolescent Males in US Public Schools: Moving from Awareness to Change (Alliant International University, 2021).

Moodley, K. G. Exploring Men’s Coping With Psychological Distress Within the Context of Conforming to Masculine Role Norms (University of Waikato, 2013).

Wu, H. & Zeng, Y. A mixed-methods investigation into the interplay between supportive work environment, achievement emotions, and teaching for creativity as perceived by Chinese EFL teachers. Percept. Mot. Skills132(1), 16–39 (2025).

Wu, H., Zeng, Y. & Fan, Z. Unveiling Chinese senior high school EFL students’ burnout and engagement: Profiles and antecedents. Acta Psychol. (Amst)243, 104153 (2024).

Petrović, I. B., Vukelić, M. & Čizmić, S. Work engagement in Serbia: Psychometric properties of the Serbian version of the Utrecht work engagement scale (UWES). Front. Psychol.8, 1799 (2017).

Khan, F., Rasli, A. M., Khan, S., Yasir, M. & Malik, M. F. Job burnout and professional development among universities academicians. Sci. Int. Lahore. 26 (4), 1693–1696 (2014).

Estévez-Mujica, C. P. & Quintane, E. E-mail communication patterns and job burnout. PLoS One. 13 (3), e0193966 (2018).

Diefendorff, J. M., Croyle, M. H. & Gosserand, R. H. The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. J. Vocat. Behav.66(2), 339–357 (2005).

Huang, S., Yin, H. & Tang, L. Emotional labor in knowledge-based service relationships: The roles of self-monitoring and display rule perceptions. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00801 (2019).

Handelsman, J. B. The relationships between individual characteristics, work factors, and emotional labor strategies in the prediction of burnout among mental health service providers. (2012).

Taxer, J. L. & Frenzel, A. C. Facets of teachers’ emotional lives: A quantitative investigation of teachers’ genuine, faked, and hidden emotions. Teach. Teach. Educ. 49, 78–88 (2015).

Moudatsou, M., Stavropoulou, A., Philalithis, A. & Koukouli, S. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010026 (2020).

Cooper, D., Yap, K., O’Brien, M. & Scott, I. Mindfulness and empathy among counseling and psychotherapy professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness (N Y)11(10), 2243–2257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01425-3 (2020).

Yarnell, L. M. & Neff, K. D. Self-compassion, interpersonal conflict resolutions, and well-being. Self Identity. 12 (2), 146–159 (2013).

Yang, Y. K. A study on burnout, emotional labor, and self-efficacy in nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm.17(4), 423–431 (2011).

Kariou, A., Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A. & Lainidi, O. Emotional labor and burnout among teachers: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health.18(23), 12760 (2021).

Bayram, N., Aytac, S. & Dursun, S. Emotional labor and burnout at work: A study from Turkey. Procedia-Social Behav. Sci.65, 300–305 (2012).

Yılmaz, K., Altınkurt, Y. & Güner, M. The relationship between teachers’ emotional labor and burnout level. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 15 (59), 75–90 (2015).

Khalil, A., Khan, M. M., Raza, M. A. & Mujtaba, B. G. Personality traits, burnout, and emotional labor correlation among teachers in Pakistan. J. Serv. Sci. Manag.10(6), 482–496 (2017).

Saleem, Z., Hanif, A. M. & Shenbei, Z. A moderated mediation model of emotion regulation and work-to-family interaction: Examining the role of emotional labor for university teachers in Pakistan. SAGE Open.12(2), 21582440221099520 (2022).

Longmire, N. H. & Harrison, D. A. Seeing their side versus feeling their pain: Differential consequences of perspective-taking and empathy at work. J. Appl. Psychol.103(8), 894 (2018).

Rynes, S. L., Bartunek, J. M., Dutton, J. E. & Margolis, J. D. Care and compassion through an organizational lens: Opening up new possibilities. Academy of Management review. Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor. NY, 37(4), 503–523 (2012).

Figley, C. R. Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. J. Clin. Psychol.58(11), 1433–1441 (2002).

Wagaman, M. A., Geiger, J. M., Shockley, C. & Segal, E. A. The role of empathy in burnout, compassion satisfaction, and secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Soc. Work. 60 (3), 201–209 (2015).

Brotheridge, C. M. & Grandey, A. A. Emotional labor and burnout: comparing two perspectives of ‘people work’. J. Vocat. Behav.60(1), 17–39 (2002).

Demerouti, E. & Nachreiner, F. Zur spezifität von burnout für dienstleistungsberufe: Fakt Oder artefakt. Z. Arbeitswiss. 52, 82–89 (1998).

Schaufeli, W. B., Desart, S. & De Witte, H. Burnout assessment tool (BAT)—development, validity, and reliability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 (24), 9495 (2020).

Mérida-López, S., Sánchez-Gómez, M. & Pacheco, N. E. Leaving the teaching profession: examining the role of social support, engagement and emotional intelligence in teachers’ intentions to quit. (2020).

Van Droogenbroeck, F., Spruyt, B. & Vanroelen, C. Burnout among senior teachers: investigating the role of workload and interpersonal relationships at work. Teach. Teach. Educ. 43, 99–109 (2014).

Leiter, M. P. & Maslach, C. The impact of interpersonal environment on burnout and organizational commitment. J. Organ. Behav. 9 (4), 297–308 (1988).

Zapf, D., Seifert, C., Schmutte, B., Mertini, H. & Holz, M. Emotion work and job stressors and their effects on burnout. Psychol. Health. 16 (5), 527–545 (2001).

Hokka, J. Emotional distance, detachment, compassion and care: The affective milieu of academic management in the neoliberal university. Sociol. Rev.71(6), 1322–1340 (2023).

Smit, B. W. Successfully leaving work at work: The self-regulatory underpinnings of psychological detachment. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol.89(3), 493–514 (2016).

Hochschild, A. R. Disengagement theory: A critique and proposal. Am Sociol. Rev. 553–569 (1975).

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B. & Schaufeli, W. B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol.43(6), 495–513 (2006).

Kinman, G., Wray, S. & Strange, C. Emotional labour, burnout and job satisfaction in UK teachers: The role of workplace social support. Educ. Psychol.31(7), 843–856 (2011).

Chang, M. L. Emotion display rules, emotion regulation, and teacher burnout. Front. Educ. 5, 90 (2020).

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through the project number (PSAU/2024/01/99520).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XZ: Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding. QL: Methodology, Visualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ER: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding. MNK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study proposals were reviewed and approved by the Academic Committee of Government College University Lahore, Pakistan, and study protocols were under the Declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore, preceding the data collection phase, participants were thoroughly informed about the essential details of the study, and written consent was secured from those who agreed to engage in the research before its initiation.

Institutional review board

The ethical approval was provided in May 2023 by the Academic Committee of Government College University Lahore, Pakistan (Approval#R-12/6532).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhai, X., Rehman, S., Addas, A. et al. Emotional labor and empathic concern as predictors of exhaustion and disengagement in college teachers. Sci Rep 15, 26281 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11304-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11304-3