Abstract

Since the practical constraints of unknown pedestrian goal information, research on inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) applied to social robots has focused on trajectory planning based on current motion direction, other pedestrians, and obstacles. However, social robots typically have clear navigation goals, and the practicality of the aforementioned methods is debatable. Moreover, trajectory prediction at longer distances also poses significant challenges for such trajectory planning methods. Therefore, this paper proposes a goal-oriented autonomous decision-making (GO-ADM) method, which addresses the social compatibility navigation problem of robots through sequential actions at each discrete time steps, eliminating the need to predict pedestrian trajectories. Specifically, this paper defines and collects goal-oriented expert demonstration and propose a collaborative interactive IRL framework for social robots. By exploring both explicit and implicit norms of pedestrian motion in the expert demonstration, goal-oriented reward function was ultimately integrated into GO-ADM to achieve goal-oriented autonomous decision-making for social robots. Additionally, GO-ADM incorporates a penalty function for social safety distance to further ensure the safety of human-robot interaction. Considering the longitudinal dominant navigation task of pedestrians in real-world scenarios, this study constructs a realistic training environment to validate the longitudinal and lateral dominant navigation tasks of the GO-ADM. The results demonstrate that, under both longitudinal and lateral dominant navigation tasks, the robot is capable of making rational autonomous decisions, with the final average deviation from the destination being less than 0.13 m and 0.23 m, respectively, and average deviation rates are less than 0.18% and 1.1%. Furthermore, reduplicate experiments demonstrate that GO-ADM achieves higher success rate with other social navigation and decision-making algorithms. Under severe interference conditions, with maximum noise 0.5 m, the success rate of GO-ADM exceeding 75%, demonstrating strong robustness against unknown interferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the advancement of artificial intelligence technology, robots are increasingly integrated into society, sharing social space with humans and providing convenient services1. Safety is a primary principle for social robots. Learning the explicit and implicit norms of human movement can enhance the predictability of robot behavior, thereby providing a safeguard for the safety of human-robot interaction2. Concurrently, their goal completion rate is also critical, reflecting the robots’ ability to serve efficiently and accurately in human society. Therefore, safety and goal-oriented are crucial safeguards for social robots to further integrate into human society3.

Reinforcement Learning (RL), with its unique iterative trial-and-error and feedback mechanisms, significantly drives the development of self-learning4. It has shown great advantages and potential in dealing with complex tasks in continuous spaces, especially in the fields of robot intelligence and autonomous driving5. Nowadays, it has been widely applied to tackle various challenges faced by social robots in dynamic environments, providing robust support for efficient and intelligent interaction and decision-making6. The effectiveness of RL task depends on the sufficient definition of the reward function7. However, empirical rewards are complex and challenging, especially for humanoid movements due to their sensitivity of cultural differences, individual preferences, and other factors8,9.

Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) has been proven to explore implicit mapping relationships from expert demonstrations, which is widely used to solve the challenge of defining rewards for complex RL tasks10. It has become a major trend in the research of artificial intelligence, especially in the field of social robots11,12. Early research was mostly based on discrete state and action spaces, and its application was limited by the accuracy of grid-based method in describing the motion states of robots13,14. Meanwhile, the curse of dimensionality brought about by more refined discrete spaces also leads to an exponential increase in computational costs, typically requiring longer training times. In subsequent research, the IRL framework with continuous state and action spaces has been implemented by employing the maximum entropy theory15. These studies approximate pedestrian motion in expert demonstrations as cooperation among multi-robot systems to achieve trajectory planning for social robots with human-like behavior16,17. Due to the real constraints of unknown pedestrian goals, robots approximated by pedestrians have no clear objectives. They make predictions based on historical information and achieve trajectory planning in a cooperative manner. Although the direction of historical motion can reflect goal information to some extent, its applicability in goal-oriented social robots is still open to discussion. Meanwhile, as the target distance increases, the randomness of pedestrian motion makes trajectory prediction difficult18. N-step lookahead rolling optimization is a good solution to this problem, but it usually comes with the difficulty of real-time solution seeking19. Compared with this, autonomous decision-making achieves navigation tasks through independent strategies for each step, without the need for historical information and trajectory prediction, which is more suitable for goal-oriented social robots20.

This paper presents a goal-driven autonomous decision-making framework for social robots navigating uncertain pedestrian environments while maintaining appropriate social distances in Fig. 1. While existing inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) approaches demonstrate strong performance in generating human-like motion for social navigation by learning from expert demonstrations to optimize policies and reward functions21, they face fundamental limitations in real-world deployment. Their reliance on training data makes them vulnerable in rare scenarios due to pedestrian behavior’s long-tail distribution, where limited samples hinder comprehensive social situation coverage. Our proposed framework addresses the aforementioned challenges by constructing goal-oriented expert demonstrations and developing an interactive training environment. The contributions in this paper are as follows:

Social robots serve in dense social environments, where both safety and navigation completion are paramount. A reasonable social distance helps enhance pedestrians’ trust in robots and promotes robots further integration into society. Goal-oriented autonomous decision-making method effectively guides social robots to achieve their navigation goal by employing independent strategies to respond to various scenarios at each discrete time step.

-

Assuming that the final position of pedestrians within a finite space-time is the goal, and by converting longitudinal and lateral speed into a continuous probability distribution as the actions, a goal-oriented expert demonstration is defined.

-

A collaborative interactive IRL framework is proposed, enabling agents to interact with random pedestrian environments to obtain prior policy networks, and then interact with expert demonstration to update goal-oriented reward functions.

-

A goal-oriented autonomous decision-making method is proposed by employing the goal-oriented reward function, and further constructing a penalty function considering safety constraints, which can effectively guide robots to move to the goal through autonomous decision-making and ensuring comfortable pedestrian social distance.

The organization of the rest of this document is as follows. Section Related work presents the related work. A detailed discussion of the method proposed in this paper is presented in Section Methodology. Sections Experimental results describe the experiment results. Finally, conclusions are given in Sections Conclusion.

Related work

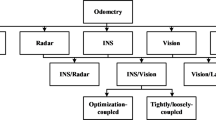

For social robots, understanding and imitating human behavior is crucial for enhancing the acceptability of their actions. Current research methodologies for social robot navigation can be broadly categorized into three classes: (1) rule-based multi-agent collaborative obstacle avoidance approaches, such as the social force model22 and Optimal Reciprocal Collision Avoidance methods23; (2) probabilistic optimization-based social navigation methods, including Bayesian inference24 and Monte Carlo methods25; and (3) data-driven learning approaches, like deep learning and reinforcement learning techniques. Notably, while the first two categories prioritize safety in structured scenarios or dynamically uncertain environments, enabling the generation of socially compliant and predictable navigation behaviors that establish a reliable foundation for robot integration into human-populated environments, they universally face challenges in balancing computational efficiency with real-time performance within densely dynamic scenarios. Moreover, their robustness to irrational behaviors and complex interaction patterns still requires further improvement.

With the advancement of deep learning and reinforcement learning, new avenues for social robots to mimic human behavior have emerged. Everett M. et al. have been promoting research on multi-robot motion planning deployed in known pedestrian environments26,27. Subsequent research has gradually solved the challenges of partially known states or the end-to-end problem of unknown states based on this foundation28,29. However, the empirical reward functions defined by these works are difficult to accurately describe pedestrian movement norms, and social robots cannot achieve pedestrian movement imitation.

The core advantage of IRL is its ability to explore potential experiences, enabling robots to learn human decision-making processes and action strategies. This capability allows them to exhibit more natural and adaptive behavior in human-robot interaction17. Konar et al. proposed a deterministic sampling-based approach with a deep network representation of strategies and reward functions for high-quality pedestrian trajectory prediction18. This approach provides accurate information about the dynamic environment for subsequent navigation and path planning. Gonon et al. utilized an inverse reinforcement learning approach to develop a novel cost feature that accurately interprets and anticipates the movement of other pedestrians30. They integrated this feature into the robot’s existing controller to enhance robot navigation. Fang et al. predicted pedestrian movement trajectories through a hazardous area using an algorithm and employed IRL to learn human-human interaction behaviors for human-computer navigation, without taking into account interactions with static obstacles31. These methods do not consider the goals, but predict future trajectories based on historical states and actions.

Methodology

This section introduces the development of a Goal-Oriented Autonomous Decision-Making (GO-ADM) algorithm. First, we parameterize trajectories through sequential control actions to define and collect Goal-Oriented Expert Demonstrations (GOED), while establishing a Training Environment (TE) that replicates dataset scenarios. Next, we propose a Collaborative Interactive Inverse Reinforcement Learning (CIIRL) framework that leverages GOED and TE to learn pedestrian motion patterns, deriving a Goal-Oriented Reward Function (GORF). Finally, GORF is integrated into GO-ADM with social distance penalty terms to enhance robotic safety constraints.

Problem description

Research on social robots focuses on exploring human behavior norms from pedestrian demonstration, using IRL as a basis for trajectory planning. The state in pedestrian demonstration typically includes information about obstacle, other pedestrian, location and environment, etc., to infer subsequent actions based on these state. Due to the unknown destination of pedestrians in real-life scenarios, the goal information is not considered in pedestrian demonstrations. However, social robots commonly have clear navigation goals, and it needs to be discussed whether the direction of subsequent actions inferred by such methods aligns with the goal direction. Therefore, this paper analyzes the positions of two random selected pedestrians within 9 discrete time steps from the dataset for analysis, with each time step being 1s.

Figure 2 demonstrates the divergence between pedestrian movement directions (colored trajectories) and their inferred goals (blue dashed lines) across temporal phases. Green, brown, and red lines respectively represent 2s, 5s, and 9s motion trajectories, with the 9th-second position assumed as the target goal. Statistical analysis reveals two critical observations: (1) Significant directional deviations persist between actual trajectories and goal-oriented at all time steps, and (2) No consistent correlation pattern emerges between movement directions and temporal progression. These findings substantiate the inherent limitations of goal-agnostic trajectory planning methods in achieving reliable robot navigation decision-making.

Besides, path planning requires predicting pedestrian trajectories and further solving for the shortest path based on dynamic environmental information. However, increasing goal distance correlates with greater directional misalignment between intended targets and actual movement vectors, causing exponentially growing prediction complexity. While traditional Model Predictive Control (MPC) uses receding-horizon optimization, its computational demands escalate combinatorially with prediction steps, creating impractical delays. Our real-time framework bypasses trajectory forecasting entirely by processing immediate environmental data directly, achieving superior performance in dynamic settings through prediction-independent decision-making for social robots.

Goal-oriented expert demonstration

GOED is derived from the seq-eth dataset from ETH, which can provides positional information of all pedestrians within each frame of the scene. To emulate human behavioral norms and enhance the acceptability of autonomous decision-making for social robots, the state space should not only incorporate the own positional information of agent but also encompass comprehensive details of goal, dynamic obstacles (pedestrians), and static obstacles (walls). Accordingly, this section conducts preprocessing on the seq-eth dataset from ETH to extract GOED.

For each frame within the scene, all pedestrians are sequentially designated as the agent to compute its environmental state in the current frame. By integrating the agent’s actions within the same frame, this process constructs the expert demonstration dataset named GOED. Figure 3 demonstrates the visualization of state information for a pedestrian defined as an agent in a specific frame of the seq-eth dataset. In this figure, the orange solid line corresponds to the movement trajectory of the agent within the scene, the gray circle marks the agent’s position in the current frame, while the white and green circles denote the agent’s starting point and goal, respectively. The difference between the goal and the agent’s position (X, Y) in the current frame represents the relative longitudinal and lateral distances to the goal (\(\Delta X_{\text {goal}}\), \(\Delta Y_{\text {goal}}\)). The red solid line in the figure denotes the scene boundary, modeled using a linear function. A vertical line drawn from the agent’s x-coordinate in the current frame intersects the boundary, the relative distance between the agent and the upper and lower boundaries (\(\Delta X_{\text {up}}\), \(\Delta X_{\text {down}}\)) are calculated as the difference between this intersection’s y-coordinate and the agent’s y-coordinate. Similarly, a horizontal line from the agent’s y-coordinate intersects the boundary, \(\Delta Y_{\text {left}}\) and \(\Delta Y_{\text {right}}\) determined by the difference between this intersection’s x-coordinate and the agent’s x-coordinate. Subsequently, Euclidean distances between the agent and other pedestrians in the current frame are computed. The four nearest pedestrians (numbered 1-4, marked by blue circles in the figure) are identified based on minimal distance criteria. Relative longitudinal and lateral distances (\(\Delta X_i\), \(\Delta Y_i\)) to these four pedestrians are derived through coordinate differences (i.e., subtracting their coordinates from the agent’s). Finally, the velocities of both the agent (\(V_x\), \(V_y\)) and pedestrians (\(V_{xi}\), \(V_{yi}\)) are calculated. Take pedestrians as an example, their velocity can be calculated as,

where, \(X_{ti}\) and \(Y_{ti}\) represent the longitudinal and lateral positions of the i-th pedestrian in the current frame, respectively, \(X_{(t-1)i}\) and \(Y_{(t-1)i}\) represent the longitudinal and lateral positions of the i-th pedestrian in the last frame, respectively, and \(\Delta t\) is the time interval between adjacent frames. In summary, the state space of GOED representation of each frame is,

Furthermore, the longitudinal and lateral speed (\(V_x\) and \(V_y\)) of the pedestrian are converted into a continuous probability distribution as strategy of expert demonstrations. Firstly, the softmax operator is employed to normalize the actions.

Then, a parameterized normal distribution \(P_{\theta }\) can be used to approximate the original expert strategy Q. The problem of solving the parameter \(\theta\) is transformed into KL divergence optimization, which is expressed as follows,

Collaborative interactive IRL approach

Training environment

This part establishes a training environment for replicating dataset scene, which is deployed in the CIIRL for training policy and value networks. The boundary of the scene is approximately a series of multiple linear equations, and the scene is developed based on Webots software.

The TE includes 15 dynamic pedestrians to maintain a high-density social environment. These pedestrians are randomly generated at any position in the environment and start moving with randomly initial longitudinal and lateral speeds within specified ranges \(( v_{x_i},v_{y_i})\in [-1,1]\). The simulation time step is 0.05s, and each step will randomly generate increments in pedestrian speeds both longitudinally and laterally \((\triangle v_{x_i},\triangle v_{y_i})\in [-0.02,0.02]\). This approach maintains the approximate direction of movement while adding the randomness. Pedestrians touching the environmental boundary mean that they have reached the destination, after which a new position and initial speed are randomly initialized.

Algorithm description

In the process of using IRL to learn reward functions from expert trajectories, there may be issues with the ambiguity of reward interpretation. To mitigate these ambiguities in the reward function, we apply the principle of maximum entropy to guide the exploration of the reward. This approach not only fosters increased randomness but also circumvents overfitting to the demonstration data. The Maximum Entropy Deep Inverse Reinforcement Learning (MEDIRL) algorithm reformulates the constrained optimization problem as a maximum entropy model32.

The GOED comprises several pedestrian trajectories \(D_{GO} = \{\zeta _1, \zeta _2,...,\zeta _n\}\), which consist of a series of discrete state-action (\(s-a\)) pairs.

Assuming that GORF \(r_{GO}\) is an unbiased neural network, then the maximum entropy theory is used to solve its parameter problem. It can be converted into an optimization problem with the following form,

where the variable \(\omega\) represents the weights assigned to the respective rewards. Acknowledging the complexity of the environment, this paper takes into account the stochastic nature of state transitions. Consequently, the likelihood function of \(D_{GO}\), which incorporates the state transition probability is formulated as follows:

where \(f_{i}(s,a)\) denotes the feature function associated with each reward, and the partition function denoted by \(z(\omega )\) serves as a normalization constant, ensuring the sum of probabilities equals one. The partition function \(z(\omega )\) is:

The weights of the reward function are derived through the likelihood function. The optimisation problem at this point is:

To update parameters using the gradient rise method, first calculate the gradient of the parameters:

Therefore, the final gradient of the objective function \(\mathcal {L}\) with respect to the parameter \(\theta\) is,

The advantage actor-critic (A2C) algorithm interacts with the training environment to learn prior \(p_{\theta }\). The A2C algorithm is based on the Actor-Critic framework, where the Actor network learns the policy function \(\pi (a|s,\phi )\) and the Critic network learns the value function \(V(s,\psi )\), with the objective function as follows,

where \(\tau\) is the movement trajectory of social robot, \(\gamma\) is the discount factor, \(r(s_t,a_t)\) is the reward function, \(\alpha\) is the weight coefficient of entropy, and \(Q^{\pi _\phi }(s_t,a_t)\) is the value function of the state-action pair.

Considering the unbiased reward function \(r_{GO}\) established by IRL applied to reinforcement learning systems interacting with the environment to explore prior policy, Eq. (14) can be further expressed as,

where \(H(\pi _\phi (\cdot |s_t))\) is the entropy of the policy in state \(s_t\).

Overall structure

The collaborative interactive inverse reinforcement learning framework involves synergistic optimization across two interactive phases. Prior Policy Exploration Phase: Reinforcement learning guides the agent to interact with a stochastic pedestrian training environment (TE) based on the current reward function. Through the Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C) algorithm, the prior policy network \(\pi\) is learned, aiming to cover fundamental behavioral patterns in dynamic environments. Reward Function Optimization Phase: Leveraging state-action pairs from GOED and the prior policy \(\pi\) explored via reinforcement learning, the parameters \(\theta\) of the goal- Oriented reward function \(r_{GO}\) are updated using MEDIRL. This process employs a KL divergence constraint to align the distributions of the prior policy \(\pi\) and the expert policy \(\pi _E\). Through alternating optimization of the policy network and the reward function, this process achieves collaborative learning.

Overall, the CIIRL and its structure are shown in Fig. 4. The agent explores prior policy \(\pi\) by employing GORF to interact with the TE. It was used to interact with the expert policy in GOED \(\pi _D\) to adjust parameter \(\theta\). The ultimate goal is to find a reward function r for the policy \(\pi\) that performs similarly to the goal-oriented expert demonstration \(\pi _E\). The difference between prior policy and expert demonstration is described using the sum of squared probability errors, that is \((\pi _E - \pi ) ^ 2\).

In order to improve the training efficiency of the CIIRL, the GORF will interact with GOED multiple times after each policy update to update its coefficients. During the reward update process, the state is randomly selected from expert demonstrations, and the action is randomly generated using a normal distribution probability model constructed with the corresponding mean and variance. This approach further approximates the probability distribution of the policy \(\pi\) and expert strategy \(\pi _E\), rather than simply considering the mean approximation. The reward function consists of a DNN with four hidden layers, each has 128, 128, 64, and 32 neurons, respectively. 1000 sets of states based on expert demonstration are extracted on each episode and 10 sets of actions are randomly generated by normal distribution probability.

To demonstrate the ability of GOED to guide robots in exploring human interaction criteria, this paper compares it with typical expert examples (TED) that only ignore pedestrian goals. That is, the state of TED can be represented as,

As each round of training is completed, an evaluator interacts with the training environment via the policy \(\pi\), which is trained with the current episode’s reward function. The distance to destination (D2D) of evaluate episode can describe the guidance of the goal-oriented reward function for robot strategy learning more intuitively. After 480 episodes of training, the reward loss that interacting with GOED decreased from 1 to about 0.05, as shown in Fig. 5a. Figure 5b shows the D2D for each episode, and it can be seen that the robot is gradually approaching the destination as training progresses. While the reward loss interacted with TED is diminishing over time, convergence to a minuscule and tolerable threshold remains elusive. Concurrently, TED’s propensity to overlook objectives is mirrored in the D2D trajectory, underscoring its challenges in directing robotic exploration towards desired targets. Figure 6 shows the loss of Policy and Value Network of CIIRL interacted with GOED. The pseudocode of GO-ADM is shown in Table 1.

Goal-oriented autonomous decision-making strategy

Social security constraints

Considering the presence of group interactions within pedestrian datasets, where individuals adhere to a more intimate social range. Such intimate interactions should not be deployed in social robots, as it would increase the risk of accidents. According to Kniereg’s research, pedestrian norms are fundamentally a form of spatial management interaction, with the concept of personal space being pivotal33. Thus, a social safety constraint is integrated into the A2C algorithm, ensuring that the robot maintains a safe and comfortable social distance from both static obstacles and dynamic pedestrians. Firstly, according to Eq. (14), the policy gradient update for A2C is:

where \(\textrm{log}\pi _{\theta }(a_t|s_t)\) the logarithm of the probability density of taking action \(a_t\) in state \(s_t\), \(r_t\) is the reward obtained at time step t. Then, a penalty term is introduced that returns a non-zero value when the state violates the constraint (i.e., when it is less than a certain fixed constant c). The penalty function f(s) is expressed as:

Introducing the penalty term into Eq. (19), the policy gradient update formula considering constraints can be expressed as,

where, \(\vartheta\) is the weight factor of the penalty term. When state \(s_t\) violates the constraint (i.e. \(s_t < c\)), the penalty term will generate a positive value, thereby reducing the probability of the policy taking action in that state. This method allows the A2C algorithm to learn effective policy while satisfying constraints.

Framework and training details

Given that most pedestrians in the original scene have a significantly higher longitudinal speed than lateral, it is debatable whether the expert demonstration derived from these datasets an effectively guide intelligent agents in completing navigation tasks focused on lateral movement. Hence, a scenario with mixed pedestrian flow in a real-world environment was adopted to simultaneously validate both longitudinal and lateral dominant navigation tasks. Similar to the training environment, the validation environment is also developed based on webots. The strategy of autonomous decision-making can interact with the webots environment through its ’supervisor’ node, and other pedestrians in the environment can do the same. The other details in the validation environment are similar to those in the training environment, except that there are 10 pedestrians due to its smaller area.

The goal-oriented autonomous decision-making framework is shown in Fig. 7. The \(r_{GO}\) in the figure is the goal-oriented reward function, and A2C only interacts with the training environment to explore autonomous decision-making strategy \(\pi _{\theta }\).

The policy and value networks consist of a three-layer DNN, each with 128 neurons in the hidden layers. ReLU activation functions are used across all networks, and the optimizer is Adam with a weight decay of \(10^{-4}\). The learning rates are \(5*10^{-5}\) for the reward network and \(10^{-4}\) for A2C, with the discount rate of 0.99.

Experimental results

This section validated GO-ADM in both training and validation environments. The training environment only tested longitudinal dominant navigation tasks, while the validation environment added lateral dominant navigation tasks.

Training environment testing

The position and speed of robot are as shown in Fig. 8, the black dots denote the initial point, and the red dots indicate the destination. It entails the robot to move to the destination through autonomous decision-making while ensuring pedestrian norms.

The orange line and blue line in Fig. 8a represent the trajectory of robot’s to the destination and pedestrians, respectively. The robot’s trajectory approximates the optimal path (i.e., the straight line between two points), which is similar to the motion norms in human. Although there is some overlap between the pedestrian trajectory and the robot trajectory in Fig. 8a, it does not mean that they have collided. Add a timeline as shown in Fig. 9, the robot trajectory does not conflict with pedestrians.

Figure 10 shows distance to the boundaries and pedestrians. At about 11s, the lateral speed of the robot significantly decreases to avoid boundaries and ensure person comfort. Compared to robots that stop waiting, changing speed to avoid dynamic pedestrians is more in line with human habits. The blue and red dashed line in Fig. 10b represents the comfortable and minimum social distance of human norms, respectively. It also proves that GO-ADM can ensure that the minimum social distance of pedestrians and mostly guarantee their comfortable social distance.

Validation environment testing

This part redeploys GO-ADM to the Validation Environment (VE) to evaluate its generalization ability. Figure 11 shows the autonomous decision-making ability of the robot to complete navigation tasks that focus on the longitudinal direction in the non-source environment. Similar to the previous, the black and red dots in the figure represent the starting points and destination of the robot, respectively. The entire testing process of the social robot moved longitudinally by about 11m and laterally by about 8m. This is clearly still a longitudinal dominant navigation task, but lateral movement is more significant compared to training environment testing.

Figure 11b illustrates the lateral and longitudinal speed of the social robot. Consistent with Fig. 8b, the robot initially exhibits higher longitudinal speed, which then gradually decreases while increasing lateral speed. This is attributed to the scenes depicted in the goal-oriented expert demonstration being predominantly longitudinal, with pedestrians primarily moving in the longitudinal direction. It is evident that although the GO-ADM is applied to scenes different from those of the expert demonstrations, it still demonstrates good decision-making effectiveness, and the robot’s movement trajectory is close to the optimal path.

Figure 12 shows the three-dimensional diagram of the robot’s position and time under this navigation task. The safety between robot and pedestrians has also been guaranteed. Combining Figs. 11b and 13a, the robot avoids the right boundary and travels to the destination by reducing longitudinal speed and increasing lateral speed in about 6–12s. Figure 13b shows the distance to the pedestrian, indicating that the robot can maintain an appropriate distance to interact with humans. These are all manifestations of robots mastering human movement norms.

The final test is aimed at the lateral-dominant navigation task of the validation environment, with its path and related information presented in Fig. 14. This navigation task requires the robot to move laterally by nearly 10 m and longitudinally by less than 3 m, which is a navigation task that dominated by lateral movement.

Compared to the trajectories shown in Figs. 8a and 11a, the path depicted in Fig. 14a demonstrates that the GO-ADM’s autonomous decision-making performance is relatively poor in lateral-dominant navigation tasks. However, when comparing Figs. 11b and 14b, it is observed that the robot reduces its longitudinal speed and increases its lateral speed at an earlier stage. This approach is clearly correct and in line with human cognition.

During the interaction with humans, the GO-ADM is still able to maintain a high level of safety, as demonstrated in Figs. 15 and 16. Figure 17 shows the completion in 50 navigation trials, with better completion of longitudinal navigation tasks due to the training dataset being more biased towards longitudinal navigation tasks. The average actual deviation in lateral navigation tasks is less than 0.23 m, with the average deviation rate of 1.1%. In most of the presented cases, personal comfort is guaranteed, and this performance is considered acceptable. The experiments also demonstrate the generalization ability of GO-ADM in different environments and lateral dominant navigation tasks.

Furthermore, experimental results demonstrate that GO-ADM exhibits generalization capabilities in lateral dominant navigation tasks. However, compared to longitudinal dominant navigation tasks, GO-ADM shows larger navigation accuracy deviations, which can be attributed to the predominant longitudinal movement patterns observed in the ETH dataset. For future research, we will augmenting the training dataset with synthetic lateral motion data to systematically enhance the navigation precision in lateral-dominated navigation tasks.

Reduplicate experiments

To further validate the decision-making intelligence of the GO-ADM autonomous navigation system, we conducted replicated experimental comparisons with multiple baseline approaches within Zara dataset environments. The comparative methodologies included det-MEDIRL18, LM-SARL34, GAIfO35, and SAIfO36. Although some methods (e.g., GA3C-CARDL27) exhibit outstanding autonomous navigation performance as collision avoidance methods with low collision rates and high goal navigation efficiency, they were excluded from the baseline comparison methods. This exclusion originates from two main considerations: (1) GA3C-CARDL is essentially a multi-agent collaborative interaction method in which individual agents are independently controllable, ignores the randomness of pedestrian motion; (2) This method fails to consider static environmental obstacles such as boundaries. These limitations result in significant differentiation between GA3C-CARDL and GO-ADM, making them unsuitable for unified metric standards. This study collect navigation success rates of all algorithms, defined as reaching the goal without collisions. Furthermore, as a widely adopted metric in socially-aware navigation systems, the disturbance score (the ratio of cumulative social distance violation duration per round to the total time) based on proxemics37 was employed to conduct quantitative assessments of robotic encroachment upon pedestrians’ personal space. In alignment with preceding experimental configurations, the minimal and comfortable social distance were defined at 0.5 and 1.2 m respectively.

The replicated experiments were conducted with 100 navigation trials per iteration across 10 consecutive rounds. Table 2 presents the comparative results of all approaches within the Zara dataset. It is clear that the proposed GO-ADM demonstrated superior navigation success rates while achieving reduced disturbance score. This is attributed to the fact that GO-ADM’s reward function, derived from expert demonstrations, outperforms the empirically designed reward functions of LM-SARL, GAIfO, and SAIfO in comprehensively evaluating pedestrian motion patterns. Although det-MEDIRL also relies on expert demonstrations (as an IRL method), its non-cooperative interaction prevents the reward function from being iteratively optimized through reasonable prior strategies, leading to relatively lower success rates in RL applications. These phenomena fully demonstrate that Collaborative Interactive IRL Approach can fully explore the intrinsic mechanism of pedestrian motion. It is used as a reward function of RL, which can effectively guide intelligent agents to complete goal-oriented navigation tasks while ensuring pedestrian social space, thereby promoting the integration of robots into complex social environments.

Furthermore, this study focuses on imitating pedestrian motion norms in complex social environments, it omits investigations into perception systems and motion tracking control modules. Consequently, the practical deployment of GO-ADM still faces substantial challenges. Considering that Sim2Real transitions of autonomous decision-making primarily encounter difficulties from scene generalization capabilities and unknown interference in perception modules, particularly under challenging scenarios involving dynamic obstacles and lighting variations. It is noteworthy that scene generalization has been validated through multi-environment simulations encompassing training/validation environment, and the Zara dataset. Therefore, this paper conducts corresponding reduplicate experiments within the Zara dataset. By introducing randomized noises to states, we simulate various interference conditions encountered by perception modules, thereby indirectly evaluating GO-ADM’s robustness in real-world implementations. Undoubtedly, this compromise validation methodology presents limitations: it neglects the discrepancies between simulated (robot models, pedestrian kinematics, environments) and real-world implementations. These critical gaps will be systematically addressed in future research.

Given the positional interference of conventional robotic distance sensors (radar or camera) in dynamic environments typically ranges between 1 and 50 cm, this paper conducts systematic experiments under five maximum noise thresholds: 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 m. The experimental protocol maintained identical parameters: 10 consecutive rounds, each comprising 100 navigation trials. Table 3 presents the reduplicate experiments results of random noises within the Zara dataset. These experimental results demonstrate that GO-ADM maintains navigation success rates exceeding 75% even under severe 0.5 m interference conditions. Notably, completion times show positive correlation with progressive increases in interference noise. This phenomenon arises from the robot initially missing the goal due to positional noise, followed by adaptive decision-making adjustments to approach the goal. These findings collectively substantiate GO-ADM’s robustness in counteracting unknown interferences.

Conclusion

In this paper, an innovative GO-ADM framework is proposed to achieve autonomous decision-making for robots in complex social environments. Unlike common pedestrian demonstrations, goal-oriented expert demonstrations incorporate the goal information in addition to regular environmental and positional considerations, based on reasonable assumptions. Furthermore, a collaborative interactive IRL framework is constructed to explore the explicit and implicit behavioral norms by expert demonstrations. These norms, deployed as rewards within the GO-ADM framework, guide the robot in making autonomous decisions through environmental states. Meanwhile, a security constraint is integrated into GO-ADM, which further ensures the social distance of pedestrians through the employment penalty function.

The GO-ADM was validated in both training and validation environments. It demonstrates better performance in longitudinal dominant navigation tasks due to the pedestrian dataset focusing on longitudinal movement. In lateral dominant navigation tasks under validation environment, GO-ADM performs relatively poorly, with the average destination deviation close to 0.23 m. However, compared to the total distance of the navigation task, its average deviation rate remains at a relatively small value of about 1.1%. That is, the framework still allows robots to efficiently complete established navigation tasks, both longitudinal and lateral, while ensuring pedestrian norms. Furthermore, reduplicate experiments demonstrate that GO-ADM achieves higher success rate with other social navigation and decision-making algorithms. Under severe interference conditions (with maximum noise 0.5 m), the success rate of GO-ADM exceeding 75%, demonstrating strong robustness against unknown interferences. Overall, the GO-ADM simplifies the decision-making process, eliminating the need for complex trajectory prediction, and can effectively guide social robots to accomplish their goal-oriented navigation tasks.

Due to inherent limitations in the GOED, GO-ADM demonstrates significantly superior navigation performance in longitudinal motion compared to lateral motion scenarios. This is correlates with the controlled nature of the experimental environment. Although incorporating stochastic elements, the kinematic and dynamic mismatches of pedestrians and robotic between simulation and real-world may substantially degrade navigation success rates under real-world deployment. The absence of developed perception and motion tracking control modules has confined GO-ADM to simulation environments. Additionally, while the study simulates sensor uncertainty through randomized noises, critical methodological limitations—such as insufficient discussion regarding ambiguous pedestrian behaviors and overfitting to training environments—are not adequately addressed. These unresolved issues further exacerbate the challenges associated with real-world deployment of the proposed framework. Future research will prioritize performance optimization for varied scenarios and practical deployment. This will involve systematic integration of pedestrian and robotic kinematics/dynamics, research on perception module, and overcoming algorithmic bottlenecks in varied scenario generalization and real-world deployment.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Raj, R. & Kos, A. Intelligent mobile robot navigation in unknown and complex environment using reinforcement learning technique. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 22852 (2024).

Kamezaki, M. et al. Reactive, proactive, and inducible proximal crowd robot navigation method based on inducible social force mode. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 7(2), 3922–3929 (2022).

Rondoni, C. et al. Navigation benchmarking for autonomous mobile robots in hospital environment. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 18334 (2024).

Mnih, V. et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 518(7540), 529–533 (2015).

Semnani, S. et al. Multi-agent motion planning for dense and dynamic environments via deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5(2), 3221–3226 (2020).

Dong, L. et al. Multi-robot social-aware cooperative planning in pedestrian environments using attention-based actor-critic. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57(4), 108 (2024).

Zhu, K. & Zhang, T. Deep reinforcement learning based mobile robot navigation: A review. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 26(5), 674–691 (2021).

Truong, X. & Ngo, T. Toward socially aware robot navigation in dynamic and crowded environments: A proactive social motion model. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 14(4), 1743–1760 (2017).

Wang, B., Liu, Z., Li, Q. & Prorok, A. Mobile robot path planning in dynamic environments through globally guided reinforcement learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5(4), 6932–6939 (2020).

Ng, A. & Russell, S. Algorithms for inverse reinforcement learning. Icml 1(2), 2 (2000).

Samsani, S. & Muhammad, M. Socially compliant robot navigation in crowded environment by human behavior resemblance using deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 6(3), 5223–5230 (2021).

Adams, S., Cody, T. & Beling, P. A survey of inverse reinforcement learning. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55(6), 4307–4346 (2022).

Kim, B. & Pineau, J. Socially adaptive path planning in human environments using inverse reinforcement learning. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 8(1), 51–66 (2016).

Alsaleh, R. & Sayed, T. Modeling pedestrian-cyclist interactions in shared space using inverse reinforcement learning. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol Behav. 70, 37–57 (2020).

Ziebart, B. et al. Maximum entropy inverse reinforcement learning. Aaai 8, 1433–1438 (2008).

Kretzschmar, H. et al. Socially compliant mobile robot navigation via inverse reinforcement learning. Int. J. Robot. Res. 35(11), 1289–1307 (2016).

Che, Y. et al. Efficient and trustworthy social navigation via explicit and implicit robot–human communication. IEEE Trans. Robot. 36(3), 692–707 (2020).

Konar, A., Baghi, B. & Dudek, G. Learning goal conditioned socially compliant navigation from demonstration using risk-based features. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 6(2), 651–658 (2021).

Yang, C. et al. A stochastic predictive energy management strategy for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles based on fast rolling optimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 67(11), 9659–9670 (2019).

Kowalczuk, Z. & Czubenko, M. Cognitive motivations and foundations for building intelligent decision-making systems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56(4), 3445–3472 (2023).

Pfeiffer, M., Schwesinger, U., Sommer, H., et al.: Predicting actions to act predictably: Cooperative partial motion planning with maximum entropy models. In IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2096–2101 (2016).

Helbing, D. et al. Social force model for pedestrian dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 51(5), 4282 (1995).

Alonso-Mora, J., Breitenmoser, A., Rufli, M., et al. Optimal reciprocal collision avoidance for multiple non-holonomic robots. In Distributed autonomous robotic systems: The 10th international symposium, 203–216 (2013).

Fooladi Mahani, M., Jiang, L. & Wang, Y. A Bayesian trust inference model for human-multi-robot teams. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 13(8), 1951–1965 (2021).

Oh, J., Heo, J., Lee, J., et al. Scan: Socially-aware navigation using Monte Carlo tree search. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 7576–7582 (2023).

Everett, M., Chen, Y., & How, J. Motion planning among dynamic, decision-making agents with deep reinforcement learning. In 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 3052–3059 (2018).

Everett, M., Chen, Y. & How, J. Collision avoidance in pedestrian-rich environments with deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Access 9, 10357–10377 (2021).

Fan, T. et al. Distributed multi-robot collision avoidance via deep reinforcement learning for navigation in complex scenarios. Int. J. Robot. Res. 39(7), 856–892 (2020).

Matsuzaki, S., & Hasegawa, Y. Learning crowd-aware robot navigation from challenging environments via distributed deep reinforcement learning. In: 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 4730–4736 (2022).

Gonon, D. & Billard, A. Inverse reinforcement learning of pedestrian–robot coordination. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 8(8), 4815–4822 (2023).

Fang, L. Danger-zone and maximum entropy deep inverse reinforcement learning for human-robot navigation. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 2580, No 1 (2023).

Wulfmeier, M., Ondruska, P., & Posner, I. Maximum entropy deep inverse reinforcement learning, arXiv preprint, (2015).

Krueger, J. Extended cognition and the space of social interaction. Conscious. Cognit. 20(3), 643–657 (2011).

Chen, C., Liu, Y., Kreiss, S., et al. Crowd–Robot interaction: Crowd-aware robot navigation with attention-based deep reinforcement learning. In IEEE ICRA, Montreal, Canada, 6015–6022 (2019).

Torabi, F., Warnell, G., & Stone, P. Generative adversarial imitation from observation. In International Conference on Machine Learning Workshop on Imitation, Intent, and Interaction (2019).

Hudson, E., Warnell, G., & Stone, P. Rail: A modular framework for reinforcement-learning-based adversarial imitation learning, arXiv:2105.03756 (2021).

Mcgrath, L. A. & Lee, G. A. Proxemics models for human-aware navigation in robotics: Grounding interaction and personal space models in experimental data from psychology. Proc. Iros Workshop Assist. Serv. Robot. A Hum. Environ. 59(1), 47–63 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the project of Science & Technology Department of Jilin Province (20220204090YY).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mingyue Luo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Software, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft; Wanbo Luo: Formal Analysis, Resources, Supervision, Project Administration; Hui Li: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing; Hewi Li: Investigation; Jianan Li: Data Curation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, M., Li, H., Luo, W. et al. Goal-oriented autonomous decision-making for social robots via collaborative interactive inverse reinforcement learning approach. Sci Rep 15, 27724 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11412-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11412-0