Abstract

Endothelial damage represents an essential pathogenic mechanism of respiratory and multiorgan dysfunction as seen in the post-acute phase of COVID-19. Biological differences between male and female sex, inflammation, and gut integrity may have an integral role in endothelial damage and explain the residual effects of COVID-19 infection in long COVID, yet evidence is limited. Confirmed COVID-19 negative participants were 1:1 propensity-score matched to COVID-19 positive participants. Symptoms occurring at least one-month following COVID-infection and lasting more than three-months was defined as long COVID. Measures of endothelial function included reactive hyperemic index (RHI ≥ 1.67 = normal endothelial function) and augmentation index (higher AIx = worse arterial elasticity). A total of 89 COVID-19 negative participants was matched to 89 COVID-19 positive participants. Among the COVID-19 survivors, the median age was 42.92 years, 46.07% were female sex, and 57 (64%) had long COVID. Higher levels of inflammation (TNF-RI and oxLDL) and gut integrity (zonulin and BDG) was associated (P < 0.05) with a two-fold increase in the odds of long COVID. Female sex, independent of COVID-19 status, was 4x more likely to have worse AIx (P < 0.0001) compared to male sex. Among female sex with long COVID, higher levels of inflammation (IL-6, VCAM, hsCRP) and gut integrity (zonulin) was independently associated (P < 0.05) with higher AIx. Female sex with long COVID symptoms had the worse inflammation, gut integrity, and arterial stiffness among COVID-19 survivors. This reinforces the importance of continued, long-term follow-up care following COVID-19 infection, with special attention needed for female sex who may be at a higher cardiovascular disease risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Long COVID refers to a range of symptoms that persist, emerge, or relapse at least three months after the acute phase of COVID-19 infection, with no alternative explanation. These symptoms, which can last for months and even years, include fatigue, brain fog, cognitive dysfunction, palpitations, and can significantly impact quality of life1,2,3. Despite the global increase in long COVID prevalence, the exact mechanisms underlying this condition remain unclear although several theories have been proposed.

Among the most widely discussed mechanisms, ongoing immune activation and chronic inflammation have been proposed as major contributors to the persistence of symptoms4,5. Changes in the gut microbiome and disruption of the gut barrier function have also been linked to systemic inflammation6,7. Endothelial dysfunction, resulting from endothelial injury and endotheliitis, persists beyond the acute phase of COVID-19 and contributes to the development and persistence of long COVID symptoms8,9. Inflammation and gut integrity are critical in maintaining endothelial health and evidence shows that disruptions in these factors contribute to endothelial dysfunction10,11.

There has been increased focus on sex differences in immune system and inflammation in the manifestations and outcomes of both acute COVID-19 and long COVID. Although male sex generally have higher baseline levels of inflammatory mediators compared to female sex, they exhibit weaker initial immune response to infections but tend to resolve the inflammation more efficiently placing them at higher risk of severe infection and mortality12,13,14. In contrast, while female sex tend to mount a stronger initial immune response, they are more vulnerable to chronic inflammatory diseases and long-term outcomes such as persistent symptoms and long COVID15,16. Emerging research suggests that sex differences extend beyond immune cell function and includes gut microbiome composition and intestinal barrier integrity17,18.

Endothelial damage represents an essential pathogenic mechanism of respiratory and multiorgan dysfunction seen in the post-acute phase of COVID-19 disease. Inflammation and gut integrity may have an integral role in endothelial damage and explain the residual effects of COVID-19 infection, yet evidence is limited. The objective of this research is to investigate temporal changes in inflammation and gut integrity and better understand sex-specific differences in endothelial function among COVID-19 survivors with long COVID.

Methods

Study design and population

The study sample included adults (≥18 years) with no history of coronary artery or cardiovascular disease between January 2020 and January 2021, no history of acute respiratory illness since December 2019, and able to provide informed consent. COVID positive participants were COVID-19 survivors with a prior documented infection. COVID negative participants were SARS-Co-V2 nucleocapsid antibody negative with no history of COVID-19 infection. COVID-19 survivors with two or more COVID-19 related symptoms occurring at least one-month following COVID-19 infection and lasting more than three-months was defined as long COVID.

The analysis data set included demographics (e.g., age, sex), comorbidities (diabetes and hypertension), metabolic markers (e.g., low density lipoprotein cholesterol), inflammatory makers (e.g., interleukin 6), gut integrity markers (e.g., zonulin), measures of endothelial function (reactive hyperemia index, augmentation index), lifestyle factors (e.g., tobacco use), and long COVID symptoms. Symptoms were collected by well-trained healthcare professionals using items from the combined and validated Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information Systems, Global Health 29 (PROMIS-29)19,20. Symptoms included anxiety, depression, brain fog, sleep problems, dizziness, excessive thirst, hair loss, sexual difficulties, shortness of breath, coughing, palpitations, fatigue, post-exertional malaise, weakness, change in smell or taste, body pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, and abnormal movements. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

Biomarkers

Participants were instructed to fast for at least 12 h before blood collection. All blood samples were sent to a CLIA-certified laboratory for metabolic measurements that included triglycerides, total cholesterol, non-high-density lipoprotein (non-HDL), and glycated hemoglobin or hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c). Additional plasma samples were promptly stored at − 80 °C within 2 h and batched for processing without prior thawing to Funderburg’s laboratory, Ohio State University, for the measurement of inflammatory, endothelial activation, and gut integrity biomarkers using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Inflammatory and endothelial biomarkers included high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), interleukin (IL-6), soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and 2 (sTNF-RI and sTNF-RII), monocyte activation markers soluble CD14 and CD163 markers (sCD14 and sCD163), endothelial activation markers intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM), and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM) using R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA); D-dimer using Diagnostica Stago (Parsippany, NJ, USA); oxidized low-density lipoprotein assays (oxLDL) using Uppsala (Mercodia, Sweden). The gut integrity marker Intestinal Fatty Acid Binding Protein (I-FABP, R&D Systems), gut permeability marker zonulin (Immunodiagnostik AG, Germany), the microbial translocation markers Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP, R&D Systems), and β-D-Glucan (BDG, MBS756415, MyBioSource, San Diego, CA) were also measured. Assay kit catalogue codes included: IL6 (HS600B), VCAM (DVCOO), TNFARI (DRT100), TNFARII (DRT200), HSCRP (DCRP00), D-DIMER (NC9884012), OX LDL (NC9664711), ZONULIN (50-311-083), IFAB (DFBP20), LBP (HK315-02), BDG (MBS756415), CD163 (DC1630), CD14 (DC140).

Vascular function

EndoPAT®-2000 device (Itamar Medical) was used as a rapid, non-invasive tool to evaluate the endothelial vasodilator function. As previously outlined21, EndoPAT device generates a Reactive Hyperemic Index (RHI) from changes in baseline pulse-wave amplitude (PWA) to post-occlusion PWA in the occluded arm. A normal RHI is ≥ 1.67. The augmentation index is calculated from pulses recorded during the baseline period and corrected to a standard heart rate of 75 beats per minute (AIx). Lower AIx values indicate better arterial elasticity.

Statistical methods

COVID negative participants were 1:1 propensity-score matched on age, exact sex, race, BMI, lipids, comorbidities, and current smoking status to COVID survivors using greedy nearest neighbor method. Participants were matched if the difference in the logits of the propensity score were ≤ 0.2x the pooled estimate standard deviation. Covariate balance and bias reduction was assessed using the standardized mean difference and the variance ratio of COVID positive to COVID negative participants.

Characteristics of study participants were summarized as median (interquartile range), mean ± standard deviation, or frequency (n) and percentage (%). Differences between COVID positive and COVID negative groups was computed using either Wilcoxon Mann-Whiney U-test or an independent t-test for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. The median value of each inflammation and gut integrity marker was used to determine a cut-off between high and low classification and the distributional tertile of AIx was used to classify low (≤-6.0%) and high (≥ 11.0%) AIx. AIx ≥ 11.0% was considered having worse arterial elasticity.

To assess potential risk factors associated with long COVID and worse AIx, we used cumulative logit models with GLM parameterization. The proportional odds assumption was assessed by the score test. General linear mixed models were used to assess which effects were associated with augmentation index and reactive hyperemia. Logistic regression was used to assess which covariates were associated with female sex. Adjusted models included long COVID status, age, sex, race, BMI, lipids (e.g., non-HDL), current smoking status, and comorbidities (e.g., diabetes and hypertension). Markers of inflammation and gut integrity were modeled independent of each other. P-values less than alpha < 0.05 were considered statistically significant and all analyses were computed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, N.C., USA).

Results

Characteristics of study participants

A total of 89 COVID negative participants were matched to 89 COVID-19 survivors (Table 1). Among the COVID-19 survivors, the median age was 42.92 years (IQR: 32.12, 54.1), and 46.07% (n = 41) were female sex. Approximately 35% (n = 31) were non-white race, 57 had long COVID, 7.87% had pre-existing diabetes, and the median BMI was 27.78 kg/m2 (IQR: 24.6, 33.73). Compared to the COVID-19 survivors, COVID negative participants had a similar (P > 0.05) distribution of age, BMI, lipid profile, and proportion of sex, race, current smokers, and pre-existing co-morbidities.

Risk factors associated with long COVID

VCAM and sCD163 was negatively associated with long COVID. Every unit increase in VCAM was associated with 62% lower odds [uOR: 0.38 (96% CIs: 0.16, 0.88); P = 0.02] of long COVID and every unit increase in sCD163 was associated with 59% lower odds [uOR: 0.41 (95% CIs: 0.21, 0.83); P = 0.01] of long COVID. In contrast, having higher than median AIx (≥ 2.0% ) or TNF-RI (≥ 1117.6 pg/mL) and every unit increase in zonulin nearly doubled the unadjusted odds [uOR: 1.9 (95%CIs: 1.08, 3.33); P = 0.03] of long COVID. In Fig. 1, after adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, smoking status, and lipids, having higher than median levels of OxLDL ≥ 54696.07 U/L, zonulin ≥ 38426.04 ng/mL, and BDG ≥ 372.2 pg/mL was associated with at least a four-fold increase in the odds of long COVID.

Risk factors associated with worse arterial elasticity

Among COVID-19 survivors with long COVID, having a higher number of symptoms was associated (P = 0.007) with having worse arterial elasticity (AIx ≥ 11.0%). Female sex with ≥ 13 reported symptoms was 5x more likely [uOR: 5.32 (95% CIs: 1.03, 27.6); P = 0.04] to have worse arterial elasticity compared to male sex who reported between 4 and 12 reported symptoms. COVID-19 survivors with long COVID were 2x more likely to have worse arterial elasticity compared to COVID-19 survivors without long COVID.

Female sex, independent of COVID-19 status, was 4x more likely [uOR: 4.68 (95% CIs: 2.61, 8.41); P < 0.0001)] to have worse AIx compared to male sex. In Table 2, female sex with long COVID was 5x more likely [uOR: 5.2 (95% CIs: 2.47, 20.33); P = 0.0003] to have worse arterial elasticity compared to COVID-19 survivors of male sex without long COVID. Additionally, older age [uOR: 1.09 (95% CIs: 1.06, 1.11); P < 0.0001] and being a current smoker [uOR: 2.85 (95% CIs: 1.5, 5.4); P = 0.001] increased the likelihood of having worse AIx.

Every unit-increase in IL-6 [uOR: 1.39 (95% CIs: 1.1, 1.92); P = 0.01], D-dimer [uOR: 1.49 (95% CIs: 1.14, 1.95); P = 0.004], zonulin [uOR: 1.57 (95% CIs: 1.08, 2.28); P = 0.02], and I-FABP [uOR: 1.58 (95% CIs: 1.12, 2.24); P = 0.01] increased the unadjusted odds of having worse arterial elasticity. Furthermore, having higher than median TNF-RII [≥ 2565.6 pg/mL; uOR: 1.81 (95% CIs: 1.04, 3.16); P = 0.04], D-dimer [≥ 436.1 ng/mL; uOR: 1.89 (95% CIs: 1.09, 3.26); P = 0.03], or I-FABP [≥ 1919.0 pg/mL; uOR: 1.89 (95% CIs: 1.09, 3.28); P = 0.02] increased the odds of having worse AI nearly two-fold. After adjusting for age, race, BMI, smoking status, comorbidities, and lipids, having zonulin ≥ 38426.04 ng/mL more than doubled [aOR: 2.38 (95% CIs: 1.24, 4.58)] the odds of having worse arterial elasticity.

Risk factors associated with female sex

COVID-19 survivors with long COVID were 3x more likely to be of female sex compared to COVID-19 survivors without long COVID [uOR: 3.53 (95% CIs: 1.42, 8.77); P = 0.01]. After adjusting for long COVID status, demographics, comorbidities, BMI, and lipids, having higher than median AIx [AIx ≥ 2.0; aOR:7.6 (95% CIs: 3.2, 18.01); P < 0.0001], oxLDL [≥ 54696.07 U/L; aOR: 3.45 (95% CIs: 1.38, 8.61); P = 0.01], and zonulin [aOR: 2.07 (95% CIs: 1.26, 3.42); P = 0.004] was more than 2x as likely to be of female sex. Every unit increase in VCAM was 59% [aOR: 0.41 (95% CIs: 0.21, 0.8); P = 0.01] less likely to be of female sex (Fig. 2). There was not enough evidence (P > 0.05) to suggest that age, BMI, being a current smoker, having pre-existing hypertension, or RHI was associated with female sex.

Sex-specific differences in arterial elasticity among COVID survivors

Overall, female sex had 13.73% higher AI when compared to male sex and the estimated AIx among COVID-19 survivors with long COVID was 5.84% higher than COVID-19 survivors without long COVID. COVID-19 survivors of female sex who reported experiencing between 4 and 12 symptoms had higher AIx (14%; P = 0.01) compared to COVID-19 survivors of male sex. COVID-19 survivors of female sex who reported more than 13 symptoms had the highest AIx (19.6%; P = 0.001) when compared to COVID-19 survivors of male sex.

In Table 3, after adjusting for age, race, BMI, smoking status, comorbidities, and lipids, female sex with long COVID [AIx = 17.34 (95% CI: 10.23, 24.44); P < 0.0001] and COVID survivors of female sex without long COVID [AIx = 11.52 (95% CI: 2.19, 20.85); P = 0.02] had higher estimated AIx compared to male COVID survivors without long COVID. Current smokers had higher AIx (7.31%; P = 0.01) compared to non-smokers, every unit increase in hsCRP was associated with 1.84% increase in AIx (P = 0.02), and having zonulin ≥38426.04 ng/mL was associated with 7.94% higher AIx (P = 0.002).

Additionally, IL-6 [AIx = 9.79 (95% CIs: 4.81, 14.77); P = 0.0002], hsCRP [AIx = 1.84 (95% CIs: 0.29, 3.39); P = 0.02], and sCD14 [AIx = 6.76 (95% CIs: 0.9, 12.63); P = 0.02] were associated with between 2 and 19% increase in AIx among female sex with long COVID compared to COVID survivors of male sex without long COVID. Having higher than median IL-6 [≥ 2.8 pg/mL; AIx = 18.54 (95% CIs: 9.12, 27.96); P = 0.0001], VCAM [≥ 2565.6 ng/mL; AIx = 16.93 (95% CIs: 6.95, 26.9); P = 0.001], hsCRP [≥ 3653.8 ng/mL; AIx = 16.94 (95% CIs: 6.33, 27.54); P = 0.002], and zonulin [≥ 3842604 ng/mL; AIx = 16.29 (95% CIs: 8.09, 24.48); P = 0.001] were associated with an increase in AIx among female sex with long COVID compared to COVID survivors of male sex without long COVID.

Discussion

In this study, the interaction between long COVID and sex suggest that female sex with long COVID have higher estimated AIx (worse arterial elasticity) then either long COVID or sex alone and that the effects of inflammation and gut integrity on endothelial function differ across strata of sex among COVID-19 survivors. Furthermore, IL-6, VCAM, hsCRP, sCD14 and zonulin were associated with having worse AIx and female sex with long COVID are at the highest risk of having worse AIx compared to COVID-19 survivors of male sex without long COVID.

We have previously established that the effect of COVID-19 on AIx differs across strata of sex17. Without stratification by sex, the effects of COVID on AIx would underestimate risk in female sex and overestimate risk among male sex. Consequently, without stratifying each risk factor by long COVID and sex, the independent effects of IL-6, VCAM, hsCRP, sCD14 and zonulin on arterial elasticity will undoubtedly underestimate risk and confound disease severity in long COVID.

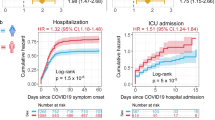

Research has demonstrated that acute COVID-19 infection carried a more severe course in male sex with higher rates of hospitalization and mortality compared to female sex22,23. However, results from the NIH RECOVER-Adult cohort study, the largest cohort study for long COVID, has provided strong support for our findings. Among 12,276 participants, female sex were 1.31 times more likely to develop long COVID compared to male sex. This increased risk was particularly pronounced in female sex aged 40 to 54 years.16 These findings align closely with our results, reinforcing the observed sex-based differences in long COVID, particularly among middle-aged female sex. This paradox is not well understood but could be explained by a complex interplay of differences in genetic, hormonal, immune and sociocultural factors24,25,26,27.

Worsening of the arterial function in COVID-19 survivors described in our study has been demonstrated in previous studies in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)27 that shares the characteristics of long-term inflammation with COVID-1928,29,30. The persistent inflammation and worsening arterial elasticity seen in our study aligns with the results from our previous studies that showed an increase in AI among COVID-19 survivors (with or without long COVID) compared to people who never had COVID-19, and that arterial elasticity was worse among COVID survivors with long COVID compared to those without long COVID symptoms with the worst arterial elasticity noted among the female participants with long COVID symptoms.

Similar to results in our study, Tudoran et al., reported that female sex with post-COVID-19 syndrome had worse arterial stiffness in the presence of metabolic syndrome31. This cohort study assessed arterial stiffness, aortic stiffness, and diastolic dysfunction among female sex with and without COVID-19 disease. Three groups were studied that included COVID survivors with and without metabolic syndrome and participants who never had COVID-19. This study demonstrated that female sex with long COVID, especially in the presence of a metabolic syndrome, had worse arterial stiffness. These results are consistent with the results from our study that female sex with long COVID have worse arterial elasticity. Unlike our study, however, Tudoran et al. included a cohort of only female sex.

Additionally, we have demonstrated that gut integrity biomarkers were elevated in female sex and highly correlated with having worse arterial function. This provides additional supporting evidence that gut integrity and microbial translocation significantly influence immune function and may contribute to long COVID pathogenesis. Atieh et al., had shown in randomized controlled study that vitamin K2 and D3 supplementation improved gut biomarkers and long COVID symptoms32. Our findings, regarding increased biomarkers and compromised arterial function, are consistent with our previous studies and reinforces the link between gut health, systemic inflammation, and vascular outcomes in long COVID.

Our study has multiple strengths. First, is the comprehensive testing of inflammation, gut integrity, and monocyte/macrophage activation markers along with the measurements of the arterial function. Second, having a COVID negative and a COVID positive with and without long COVID comparison groups allowed for a more accurate assessment of the effects of COVID-19 disease on markers of inflammation and gut integrity in long COVID. Third, using a propensity-score matched sample with exact sex-matched population. This reduces selection bias and increases exchangeability33 on factors such as age, sex, race, lipids, smoking status, BMI, and comorbidities between comparison groups.

This study also had several weaknesses. First, we did not have repeated arterial function assessments to capture changes in endothelial function before and after COVID-infection or the ability to assess the effects of COVID-19 disease on endothelial function over time. Second, despite propensity-score matching on age, exact sex, race, BMI, lipids, preexisting comorbidities, and current smoking status, unmeasured confounders and other cardiovascular risk factors may explain some of the variability in our endothelial function results. Lastly, there is a bias-variance trade-off when using a propensity-score matched sample. The smaller sample size may increase variability in our estimates and increase the probability of type II error. However, to reduce sampling variability and increases precision in our estimates, the same covariates included in estimating the conditional probability of having COVID were used in adjusted models.

Our findings show that there are sex-differences in markers of inflammation, gut integrity, and arterial elasticity among COVID survivors with long COVID symptoms. Female sex with long COVID symptoms had the worse inflammation, gut integrity, and arterial stiffness. This reinforces the importance of continued, long-term follow-up care following COVID-19 infection with special attention needed for female sex who may be at a higher cardiovascular disease risk. In this context, future research should investigate interventions that may prevent or improve the sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 on vascular function, inflammation, and gut health.

Data availability

The data that support the are available upon reasonable request. Please contact corresponding authors.

References

Thaweethai, T. et al. Development of a definition of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Jama Jun. 13 (22), 1934–1946. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.8823 (2023).

Hope, A. A. & Evering, T. H. Postacute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Infect Dis. Clin. North. Am Jun. 36 (2), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2022.02.004 (2022).

Pham, A., Smith, J., Card, K. G., Byers, K. A. & Khor, E. Exploring social determinants of health and their impacts on self-reported quality of life in long COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep Dec. 6 (1), 30410. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81275-4 (2024).

Low, R. N., Low, R. J. & Akrami, A. A review of cytokine-based pathophysiology of long COVID symptoms. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 10, 1011936. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1011936 (2023).

Davis, H. E., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J. M. & Topol, E. J. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev. Microbiol Mar. 21 (3), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2 (2023).

Giron, L. B. et al. Plasma markers of disrupted gut permeability in severe COVID-19 patients. Front. Immunol. 12, 686240. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.686240 (2021).

Moreno-Corona, N. C. et al. Dynamics of the microbiota and its relationship with Post-COVID-19 syndrome. Int J. Mol. Sci Oct. 1 (19). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241914822 (2023).

Wu, X. et al. Damage to endothelial barriers and its contribution to long COVID. Angiogenesis Feb. 27 (1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-023-09878-5 (2024).

Zanoli, L. et al. Vascular dysfunction of COVID-19 is partially reverted in the Long-Term. Circ Res Apr. 29 (9), 1276–1285. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.121.320460 (2022).

Maiuolo, J. et al. The contribution of gut microbiota and endothelial dysfunction in the development of arterial hypertension in animal models and in humans. Int J. Mol. Sci Mar. 28 (7)). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23073698 (2022).

Hamidabad, N. M. et al. Compositional changes of gut Microbiome in association with endothelial dysfunction. JACC 83 (13_Supplement), 2295–2295. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(24)04285-2 (2024).

Jin, J. M. et al. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front. Public. Health. 8, 152. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152 (2020).

Twitchell, D. K. et al. Examining male predominance of severe COVID-19 outcomes: A systematic review. Androg Clin. Res. Ther. 3 (1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1089/andro.2022.0006 (2022).

Trigunaite, A., Dimo, J. & Jørgensen, T. N. Suppressive effects of androgens on the immune system. Cellular Immunology. /04/01/ 2015;294(2):87–94. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.02.004

Bai, F. et al. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol. Infect Apr. 28 (4), 611. .e9-611.e16 (2022).

Shah, D. P. et al. Sex differences in long COVID. JAMA Netw. Open Jan. 2 (1), e2455430. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.55430 (2025).

Durieux, J. C. et al. Sex modifies the effect of COVID-19 on arterial elasticity. Viruses Jul. 6 (7). https://doi.org/10.3390/v16071089 (2024).

Petrilli, C. M. et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in new York city: prospective cohort study. BMJ 369, m1966. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1966 (2020).

Hays, R. D., Bjorner, J. B., Revicki, D. A., Spritzer, K. L. & Cella, D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res Sep. 18 (7), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9 (2009).

Hays, R. D., Spritzer, K. L., Schalet, B. D. & Cella, D. PROMIS(®)-29 v2.0 profile physical and mental health summary scores. Qual Life Res Jul. 27 (7), 1885–1891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1842-3 (2018).

Zisis, S. N. et al. Arterial stiffness and oxidized LDL independently associated with Post-Acute sequalae of SARS-CoV-2. Pathog Immun. 8 (2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.20411/pai.v8i2.634 (2023).

Dessie, Z. G. & Zewotir, T. Mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients. BMC Infect. Dis Aug. 21 (1), 855. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06536-3 (2021).

Hamlin, R. E. et al. Sex differences and immune correlates of long Covid development, symptom persistence, and resolution. Sci Transl Med Nov. 13 (773), eadr1032. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.adr1032 (2024).

Wehbe, Z. et al. Molecular and biological mechanisms underlying gender differences in COVID-19 severity and mortality. Front. Immunol. 12, 659339. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.659339 (2021).

Kharroubi, S. A. & Diab-El-Harake, M. Sex-differences in COVID-19 diagnosis, risk factors and disease comorbidities: A large US-based cohort study. Front. Public. Health. 10, 1029190. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1029190 (2022).

Mu, W., Patankar, V., Kitchen, S. & Zhen, A. Examining chronic inflammation, immune metabolism, and T cell dysfunction in HIV infection. Viruses Jan. 31 (2). https://doi.org/10.3390/v16020219 (2024).

Mouchati, C., Durieux, J. C., Zisis, S. N. & McComsey, G. A. HIV and race are independently associated with endothelial dysfunction. AIDS Feb. 1 (2), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003421 (2023).

Atieh, O. et al. The Long-Term effect of COVID-19 infection on body composition. Nutrients Apr. 30 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16091364 (2024).

Tudoran, C. et al. Correspondence between aortic and arterial stiffness, and diastolic dysfunction in apparently healthy female patients with Post-Acute COVID-19 syndrome. Biomedicines Feb. 8 (2). https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11020492 (2023).

Dumas, A., Bernard, L., Poquet, Y., Lugo-Villarino, G. & Neyrolles, O. The role of the lung microbiota and the gut-lung axis in respiratory infectious diseases. Cell Microbiol Dec. 20 (12), e12966. https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.12966 (2018).

Ali, M. F., Driscoll, C. B., Walters, P. R., Limper, A. H. & Carmona, E. M. β-Glucan-Activated human B lymphocytes participate in innate immune responses by releasing Proinflammatory cytokines and stimulating neutrophil chemotaxis. J Immunol Dec. 1 (11), 5318–5326. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1500559 (2015).

Atieh, O. et al. Vitamins K2 and D3 improve long COVID, fungal translocation, and inflammation: randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 17 (2), 304 (2025).

Flanders, W. D. & Eldridge, R. C. Summary of relationships between exchangeability, biasing paths and bias. Eur J. Epidemiol Oct. 30 (10), 1089–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9915-2 (2015).

Funding

This project was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Northern Ohio which is funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health, UM1TR004528. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.D. contributed to study design, computing statistical analyses and write-up, and contributed to writing in each section of manuscript. Z.D. contributed to writing methods and discussion sections. J.D., M.A., and O.A. contributed to writing introduction. J.B. contributed to writing discussion section. C.W. and G.A.M., contributed to study design and manuscript writing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center (UHCMC) reviewed the study protocol and a written informed consent was required prior to participation. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Durieux, J.C., Koberssy, Z., Daher, J. et al. Sex differences in inflammation and markers of gut integrity in long COVID. Sci Rep 15, 27374 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11470-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11470-4