Abstract

Capillary microfluidic chips (CMCs) enable passive liquid transport via surface tension and wettability gradients, making them central to point-of-care diagnostics and biomedical sensing. However, accurate analysis of capillary-driven flow experiments remains constrained by the labour-intensive, time-consuming, and inconsistent nature of manual fluid path tracking. Here, we present AI-CMCA, an artificial intelligence framework designed for capillary microfluidic chip analysis, which automates fluid path detection and tracking using deep learning-based segmentation. AI-CMCA combines transfer learning-based feature initialization, encoder-decoder-based semantic segmentation to recognize fluid in each frame, and sequential frame analysis to track then quantify fluid progression. Among the five tested architectures, including U-Net, PAN, FPN, PSP-Net, and DeepLabV3+, the U-Net model with MobileNetV2 achieved the highest performance, with a validation IoU of 99.24% and an F1-score of 99.56%. Its lightweight design makes it well suited for smartphone or edge deployment. AI-CMCA demonstrated a strong correlation with manually extracted data while offering superior robustness and consistency in fluid path analysis. AI-CMCA performed fluid path analysis up to 100 times faster and over 10 times more consistently than manual tracking, reducing analysis time from days to minutes while maintaining high precision and reproducibility across diverse CMC architectures. By eliminating the need for manual annotation, AI-CMCA significantly enhances efficiency, precision, and automation in microfluidic research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microfluidics has revolutionized biomedical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and pharmaceutical research by enabling the precise manipulation of fluid volumes ranging from microliters to nanoliters. The integration of microfluidic chips in analytical systems offers key advantages, including reduced reagent consumption, shorter reaction times, and enhanced sensitivity in detecting biomolecular interactions1,2. These features make microfluidics highly suitable for point-of-care (POC) diagnostics, where rapid and accurate detection is critical for timely clinical decision-making3,4.

Capillary microfluidic chips (CMC) have emerged as a promising platform for fluid manipulation in diagnostic and biochemical applications due to their ability to passively transport liquids without the need for external pumps or actuators5. These systems exploit surface tension and wettability gradients to control fluid movement, significantly simplifying device operation while eliminating the need for complex external instrumentation. This passive transport mechanism makes CMCs particularly suitable for POC applications, where portability and minimal user intervention are crucial6. As a result, CMCs have been widely employed in medical diagnostics, biochemical assays, and lab-on-a-chip systems for monitoring biological fluids, including blood, saliva, sweat, and urine assays7,8,9. Despite these advantages, significant challenges remain in optimizing CMC design and fabrication to ensure consistent flow behaviour and reliable analytical performance in every new chip design.

One of the primary challenges in CMC development is the sensitivity of fluid flow to microscale geometric and surface variations. Small deviations in channel geometries10surface roughness11 or material hydrophilicity12 can significantly alter local surface tension and capillary forces, leading to inconsistencies in flow velocity and directionality. Additionally, fabrication techniques such as laser cutting, soft lithography, and 3D printing often introduce structural imperfections that affect flow uniformity13,14. The integration of complex structures, such as self-powered biosensing platforms15 autonomous POC diagnostic devices16,17 and wearable microfluidic patches3 necessitates iterative validation cycles involving adjustments to channel dimensions, material compositions, and bonding techniques.

Accurate fluid path analysis in CMCs is critical for performance evaluation and design optimization. This process typically involves capturing high-resolution video data with 30–100 frames per second at resolutions of 1080p to monitor the fluid path progression, capillary length, and velocity over time. Conventional analysis relies on manual frame-by-frame processing using software tools such as ImageJ18 and its extended distribution Fiji19 which offer functionalities including thresholding, particle tracking, and region-of-interest selection. However, these traditional methods are labor-intensive, prone to inter-operator variability, and computationally inefficient when handling large datasets. For example, manual tracking can take several hours per dataset and is susceptible to inconsistencies due to minor fluctuations in lighting, chip positioning, and variations in fluid opacity, leading to measurement errors and reduced reproducibility20,21. These limitations highlight the need for automated, high-precision image analysis techniques to improve efficiency and analytical accuracy in CMC evaluation.

These traditional fluid path analyses in microfluidics are constrained by manual processing errors and operator variability. As CMC applications expand into high-throughput biochemical screening in multiplexed enzymatic assays22 and continuous physiological monitoring in wearable microfluidic sensors23 there is a growing demand for automated, high-precision image analysis tools capable of handling large datasets while ensuring reproducibility3,5. Recent efforts to automate fluid path and capillary length progression analysis in CMC, have led to the development of software tools designed to reduce manual intervention21. One such approach employs OpenCV’s Channel and Spatial Reliability object tracker24 a correlation-filter-based method that maintains object stability during motion tracking. While this framework provides a computationally lightweight solution for extracting fluid velocity data, it remains highly sensitive to variations in environmental conditions. Its performance can degrade in the presence of rapid fluid motion, variable lighting, or complex channel geometries, necessitating frequent re-initialization.

To address the limitations of traditional fluid path analysis, deep learning-based segmentation techniques have emerged as a more robust alternative, offering improved accuracy in image and video processing, background segmentation, object recognition under dynamic conditions25 various fluidic properties measurement26 and droplet microfluidics27. Unlike traditional thresholding and object-tracking approaches, deep learning models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)28 learn hierarchical representations of spatial and temporal features directly from raw video frames, making them highly adaptable to variations in complex geometries and opacities29,30 that could be a proper solution to address the fluid opacity, lighting, and components geometry. CNNs process images through multiple convolutional layers, extracting low-level edges, mid-level textures, and high-level spatial patterns31 which are essential for fluid path progression analysis. Advanced CNN-based models, such as U-Net and its derivatives, have demonstrated high segmentation accuracy in microfluidic chip applications32 eliminating the need for manual parameter tuning by learning relevant feature representations automatically. To further improve model efficiency, Transfer Learning (TL)33 has been employed to address key challenges such as extensive hyperparameter tuning, overfitting risks, and limited training data. By leveraging pre-trained models on large-scale datasets, TL enables faster convergence and improved generalization.

Among deep learning architectures, U-Net and its variants have shown exceptional performance in microfluidic chip data interpretation32 and fluid path segmentation by utilizing multi-scale feature extraction and skip connections to preserve fine spatial details34. Beyond segmentation, deep learning-powered image processing has been employed for automated droplet detection35 and classification in microfluidic chips36. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into microfluidic platforms continues to drive advancements in real-time fluid path analysis, flow control, and biomedical applications, significantly reducing human intervention while improving reproducibility and computational efficiency37.

To overcome the limitations of traditional fluid path analysis and the labor-intensive nature of conventional video-based evaluation within CMC, this work introduces an AI-powered framework for CMC Analysis (AI-CMCA). Deep learning-driven image segmentation and automated fluid path progression analysis are used to replace manual tracking, streamline design iteration cycles, and enhance the evaluation and optimization of CMC. Unlike conventional methods that require extensive manual tuning and are highly sensitive to variations in lighting, chip alignment, and fluid opacity, AI-CMCA autonomously extracts fluid path features from raw video frames, facilitating high-precision fluid path analysis. The following sections outline the methodology, experimental setup, and validation of AI-CMCA, demonstrating how it effectively addresses key challenges in passive microfluidic flow analysis, including segmentation accuracy, flow variability, and real-time monitoring.

Results and discussion

The schematic illustrates a representative CMC (Scheme 1A) featuring parallel straight channels, a fundamental design used to evaluate material properties, assess fabrication precision, and establish baseline flow characteristics. These straight-channel structures serve as a controlled test environment, enabling the analysis of surface wettability, capillary-driven flow consistency, and microchannel integrity before integrating more complex geometries.

More complex CMC designs enable precise sample processing in POC diagnostics by leveraging passive fluid transport, though this self-driven mechanism complicates fluid path tracking and analysis. To extract valuable insights from these passive systems with greater precision, we introduce AI-CMCA, a deep-learning-based segmentation framework (Scheme 1B) designed to automate fluid path analysis. AI-CMCA integrates video acquisition, preprocessing, segmentation, and quantitative tracking, which supports high-accuracy evaluation of capillary-driven flow. By eliminating manual tracking and improving scalability, reproducibility, and analytical efficiency, AI-CMCA provides a powerful solution for microfluidic research, advancing the automation of fluid path analysis in POC applications.

Illustrating (A) a representative experimental setup featuring a set of parallel straight channels as a fundamental microfluidic element in a capillary microfluidic chip (CMC) design, (B) AI-CMCA framework and the sequential steps, including (a) video acquisition, (b) preprocessing, (c) AI model implementation, and (d) fluid path analysis, determining the fluid path length variation over time in a capillary-driven fluid flow over CMC.

CMC components and fabrication process

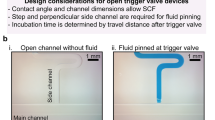

Figure 1A illustrates the fundamental components of a CMC, where most microfluidic networks consist of microchannels, either straight or serpentine, to facilitate fluid delivery, incubation, reaction, or mixing, along with other feature configurations tailored for specific microfluidic applications. The junctions, functioning as merging or splitting points, regulate fluid distribution, enabling controlled interactions within the system38,39,40. These fundamental components collectively define fluid path progression, influencing the efficiency and reproducibility of capillary-driven flow within the microfluidic network.

Schematic of the simple CMC designs and their fabrication process. (A) Design of the capillary channel network and fundamental components of straight and serpentine channels, including merging and splitting. (B) Laser cutting of individual layers. (C) Multi-layer assembly of CMC via pressure-sensitive adhesive sheets. (D) Experimental setup for recording the operation of the assembled CMC.

The CMC used in this study was fabricated using laser-cutting technology to achieve high-precision microchannel dimensions with a need for expensive cleanroom facilities. The network layer, composed of 100 μm-thick PSA, was patterned to create the microchannel network (Fig. 1B) and bonded to the substrate and sealing layers to ensure fluid containment and controlled flow dynamics (Fig. 1C). For experimental validation, a dyed liquid was introduced at the inlet, and its movement was recorded using high-resolution video acquisition for fluid path analysis in AI-CMCA (Fig. 1D).

Generation of AI-CMCA training data

To develop a robust dataset for training and evaluating the AI-CMCA segmentation models, we collected 140 images from CMCs experiments, covering a range of flow conditions, channel geometries, and lighting variations. Each image was carefully selected to ensure model generalization across different microfluidic designs.

As illustrated in Fig. 2A, video recordings were converted into PNG frames, followed by preprocessing and annotation to generate high-quality segmentation masks. Using a custom Python-based UI, an initial HSV-based segmentation was applied, with manual refinements ensuring accurate fluid path labelling. Each image was paired with a corresponding ground-truth mask, forming a structured dataset essential for supervised learning. To enhance the dataset and improve model robustness, we applied data augmentation techniques, including rotation, flipping, and contrast adjustments, ensuring adaptability to real-world experimental variations. Additionally, all images were resized to a standard 512 × 512 resolution to maintain consistency across training inputs. This annotated and preprocessed dataset served as the foundation for training deep-learning segmentation models.

Development of segmentation models

To automate fluid path segmentation in capillary microfluidic chips (CMCs), we evaluated five state-of-the-art deep learning architectures, U-Net, PAN, FPN, PSP-Net, and DeepLabV3+,each coupled with a carefully selected encoder backbone. The encoder options, MobileNetV2, ResNet50, EfficientNetB3, ResNeXt50-32 × 4d, and ResNet101, were chosen based on their established performance in medical image segmentation, their efficiency in feature extraction, and their ability to generalize well with limited annotated data.

Among these, U-Net with MobileNetV2 was selected as the optimal configuration due to its precise spatial localization enabled by skip connections and its lightweight design, which together contributed to the highest segmentation accuracy in our study. PAN with ResNet50 leveraged refined attention mechanisms to preserve edge details, while FPN with EfficientNetB3 provided a lightweight and efficient multi-scale feature representation. PSP-Net, paired with ResNeXt50-32 × 4d, offered robust contextual understanding across varying spatial scales, and DeepLabV3 + with ResNet101 combined deep residual learning with atrous spatial pyramid pooling to effectively segment complex geometries.

As shown in Fig. 2B, model performance was evaluated using standard segmentation metrics, including Intersection over Union (IoU), and F1-score, across both training and validation datasets. All models employed transfer learning with pre-trained ImageNet weights to accelerate convergence and enhance generalization. These architecture and encoder pairings were selected not only for segmentation accuracy but also for their robustness in tracking fluid progression across a variety of CMC layouts and designs.

Among the tested models, U-Net with MobileNetV2 demonstrated the highest segmentation accuracy, achieving a training IoU of 99.49% and validation IoU of 99.24%, along with a validation F1-score of 99.56% and Dice loss of 0.013. Its skip-connection-based architecture enabled precise feature localization, making it the most reliable model for AI-CMCA segmentation. The PAN model with ResNet50 followed closely, achieving a validation IoU of 99.00%, with a validation F1-score of 99.50% and Dice loss of 0.006, benefiting from its attention-based feature refinement. Other models, including FPN with EfficientNetB3 (98.60% validation IoU), PSP-Net with resnext50-32 × 4d (97.82% validation IoU), and DeepLabV3 + with ResNet101 (98.95% validation IoU), also exhibited strong segmentation capabilities. While these architectures leveraged multi-scale feature extraction and pyramid pooling strategies, their performance was slightly lower than that of U-Net, reinforcing its suitability for fluid path segmentation in microfluidic applications.

Figure 2C presents performance trends across training epochs, illustrating the convergence of IoU, F1-score, and Dice loss for each model. The graphs confirm that U-Net achieved the most stable and accurate segmentation performance, with minimal overfitting across training and validation sets. Additionally, Fig. 2D showcases representative segmentation results, including original images, ground-truth masks, predicted masks, and predicted heatmaps, visually validating the effectiveness of the AI models in accurately detecting fluid path regions. These results highlight the effectiveness of AI-CMCA, deep learning-based segmentation in automating microfluidic fluid path detection, providing a scalable and precise alternative to traditional manual analysis methods.

Data processing and segmentation model evaluation. (A) Workflow for preparation and processing data from raw video frames. (B) Comparison of segmentation models and encoder architectures with associated performance metrics. (C) Performance trends across training epochs for IoU, F1-score, and Dice loss. (D) Representative inputs, ground-truth masks, predicted outputs, and heatmaps. Scale bar: 1 cm.

Quantitative fluid path tracking

To quantitatively assess fluid path progression in CMC, we implemented an algorithmic approach that tracks the advancing fluid front across sequential frames, enabling precise measurement of fluid displacement over time. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, the analysis pipeline consists of three key stages: preprocessing, segmentation and tracking, and post-processing with feature extraction. In the preprocessing stage, raw video frames are standardized through resolution normalization and frame extraction to ensure consistency (Fig. 3A, a). Once the data is prepared, the trained U-Net model is applied to each frame, generating binary segmentation masks that isolate the fluid region (Fig. 3A, b). A frame differencing algorithm is then employed to detect newly advanced fluid areas by comparing each frame to the preceding one, allowing for the precise identification of dynamic fluid path. Following segmentation, fluid path analysis utilizes a clustering-based tracking algorithm to label and monitor distinct fluid regions (Fig. 3A, c1). By computing the center of mass displacement of each detected fluid region, the system constructs a time-series trajectory that accurately maps the progression of the fluid front. The predicted heatmaps (Fig. 3A, c2) provide a visual representation of the tracked movement, with inset plots depicting fluid displacement over time, offering a clear depiction of flow progression. Figure 3B presents the pseudocode for the fluid front-tracking algorithm, outlining key operations such as clustering, region labelling, and center-point computation for each detected fluid region that enables automated, high-precision fluid path analysis.

Workflow for fluid segmentation and front tracking in CMCs (A) (a) Data pre-processing: a1: applying noise reduction to raw videos, a2: extracting individual frames. (b) Data processing: applying the trained U-Net model to segment fluid regions from the chip background. (c) Data post-processing: c1: frame differencing to isolate newly advanced fluid areas and clustering to remove extraneous pixels, c2: generating a heatmap of detected flow regions and tracking center points (red dots) over time, with an inset plot illustrating fluid progression. (B) Pseudocode illustrating the fluid front tracking algorithm, including clustering, region labelling, and center-point computation for each labelled region.

Experimental validation and comparative analysis

To quantitatively assess the effectiveness of AI-CMCA in tracking fluid path progression, we conducted extensive experimental validation and a comparative study against manual data extraction methods. Our primary objectives were to evaluate fluid displacement accuracy, tracking reliability, and data processing efficiency across multiple CMC architectures, including straight channels, merging/splitting junctions, and serpentine configurations.

A capillary microfluidic chip with six parallel straight channels was used to compare system-generated fluid path estimates with manually annotated ground truth for two representative branches (br0 and br1) (Fig. 4A, a-b). The close alignment between automated and user-tracked results reflects the high accuracy and robustness of AI-CMCA in identifying fluid fronts. This observation was further corroborated in Fig. 4B, where AI-CMCA maintained reliable fluid tracking in more complex designs featuring split–merge junctions, effectively managing multiple branching pathways.

Tree-shaped capillary microfluidic networks are fundamental design elements in lab-on-chip systems, as their hierarchical branching architecture enables efficient passive fluid distribution while sustaining strong capillary flow across complex channel layouts10. Both theoretical and experimental studies have demonstrated that well-balanced, symmetric trees of microchannels can maintain nearly constant flow and, in some cases, amplify fluid delivery at successive bifurcations41. However, any asymmetry at critical merging points can disrupt this balance, leading to uneven fluid filling, unsynchronized interfaces, and the frequent entrapment of air bubbles—ultimately compromising the performance and reliability of the device. Among the evaluated test cases, one of the most geometrically complex designs was a tree-shaped CMC42which posed significant analytical challenges due to its numerous bifurcation and convergence points. Merging points in particular are crucial, as synchronized arrival of fluid fronts is essential to avoid bubble formation and ensure uninterrupted flow. When incoming fluid streams fail to reach these junctions simultaneously, bubbles often form, disrupting the capillary flow and potentially causing chip failure. This emphasizes the need for high-resolution, frame-by-frame tracking of fluid progression in such structures. As illustrated in Fig. 4C, a, the AI-CMCA framework successfully quantified the fluid path length over time for each individual branch, revealing subtle asynchronies that would be difficult to detect manually. Figure 4C, b shows the corresponding top-view image of the chip, with critical merging points and labeled branches clearly annotated. This case study highlights the robustness of AI-CMCA in handling intricate network topologies and capturing nuanced deviations in flow behavior that are critical for evaluating capillary microfluidic performance.

For fundamental elements of CMCs like straight channels, the total processing time dropped from 5 h to only 3 min with AI-CMCA. In addition to the point-by-point comparisons, Fig. 4E, a-d offers a broader perspective on total analysis time across several CMC designs.

Our team previously developed two complex CMC architectures: a self-powered microfluidic device for quantifying glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)15 (Fig. 4E, e) and an autonomous point-of-care testing chip for detecting SARS-CoV-2 antigens (Fig. 4E, f)16. These designs previously required 60 to 110 h of manual analysis, equivalent to 10 to 20 working days of continuous effort. In contrast, AI-CMCA reduced these tasks to just 36 and 66 min, respectively, significantly improving efficiency. Conducting such a comparative study required analyzing hundreds of CMCs, which took months of manual effort. With real-time analysis, these evaluations could be performed immediately after the experiment, providing critical insights into chip quality, material properties, and the fabrication process. This capability is invaluable for optimizing designs and enhancing mass-production workflows.

Automated flow path analysis and efficiency gains in different CMC designs. (A) Quantitative flow analysis of a CMC with six parallel channels: (a) results for br0 and (b) results for br1, comparing system-generated and user-tracked data. (B) Flow tracking in a CMC with splitting and merging regions, showing system- and user-generated results across four branches. (C) Flow tracking in a tree-shaped CMC featuring ten merging points and fifteen splitting points, representing a real-life CMC with a complex channel network: (a) extracted datapoints and (b) a photograph of the CMC highlighting critical points in red circles and branch numbers in green. (D) Comparison of fluid front tracking accuracy between AI-CMCA-generated and manually selected user-annotated center points for both (a) simple straight-channel CMC and (b) more complex split-merge-serpentine CMC. (E) Total time required for analysis across different CMC designs such as (a) straight channels, (b) split/merge, (c) serpentine channels, (d) split merge serpentine, SARS-Cov-2-POC testing15and GFAP POC testing16highlighting the efficiency gains of the automated system over manually tracking.

These findings highlight the significant improvements in both accuracy and throughput enabled by AI-CMCA. By eliminating labor-intensive manual annotations and reducing human error, AI-CMCA streamlines CMC design and validation workflows, making it a valuable tool for high-throughput experimentation, POC diagnostics, and advanced microfluidic applications. While AI-CMCA demonstrates clear advantages, some limitations remain. The dataset of 150 annotated images, while sufficient for model development, may limit generalization; however, data augmentation improves adaptability. Variability in image quality, including lighting inconsistencies and optical distortions, may impact segmentation accuracy, though preprocessing helps mitigate these effects. Minor inconsistencies from manual annotation are unlikely to affect performance significantly, and future integration of semi-supervised learning could further enhance accuracy. While this study evaluates five deep-learning architectures, exploring transformer-based models may offer additional refinements. AI-CMCA currently tracks single-phase fluid progression, and expanding its capabilities to multi-phase flow differentiation and reaction monitoring would further enhance its applicability.

Furthermore, a notable advantage of AI-CMCA is its applicability as a valuable tool for high-throughput experimentation across various microfluidic designs, including centrifugal microfluidics43gravity-driven microfluidics44 and tow-phase flow microfluidics45. Moreover, the choice of fluid-driving mechanisms, whether passive, such as capillary forces46 and gravity-driven components47or active pumps48greatly influences the performance and reliability of microfluidic platforms. AI-CMCA has notably reduced analysis time from days to minutes while ensuring high precision and reproducibility across a range of microfluidic architectures.

Materials and methods

CMC materials

The CMC was fabricated in a multilayer design to enhance structural integrity and modularity for diverse experimental applications. A variety of biocompatible materials were selected, including thermoplastic elastomer (TPE), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), and standard microscopic glass slides. PMMA (Static Dissipative Rigid Plastic, SciCron Tech, USA) was selected due to its high mechanical strength, chemical resistance, and excellent optical transparency, which are essential for high-resolution visualization and computational analysis of fluid path progression. For applications requiring superior optical clarity or chemical inertness, standard glass microscope slides (Corning™, USA) served as an alternative substrate.

In addition to the substrate, the sealing layer consisted of TPE (9984 Diagnostic Microfluidic Surfactant-Free Medical Hydrophilic Film, 3 M Co., USA), selected for its transparency and hydrophilic properties, which support passive fluid path progression while reducing the reliance on external pumps. The channel layouts were designed using AutoCAD 2024 and transferred to JobControl® Vision software for precision fabrication using a Trotec Speedy 360 FLEXX CO₂ laser cutter (80 W). Laser cutting parameters—including power, speed, focal depth, and number of passes—were experimentally optimized for each material layer to ensure clean cuts and precise feature definition. For PSA layers with a thickness of 100 μm, the optimal settings were 24% power, 37% speed, a focal depth of 65, and two passes. For TPE layers at 80 μm thickness, 22% power, 50% speed, a focal depth of 90, and two passes were used. For PMMA substrates with 1 mm thickness, cutting was performed with 40% power, 20% speed, a focal depth of 80, and four passes. These values were found to be effective for the specific materials and laser system used; however, some variation (particularly up to ± 10% in power and speed) may occur depending on material batch variability, laser lamp aging, and maintenance status. Focal depth and number of passes typically remain consistent under normal operating conditions.

The microfluidic networks, comprising a series of intricate channels, chambers, valves, and wells, were created using a pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSA) (ARcare® 8939, Adhesives Research) sheet. The PSA’s removable liner was retained until final assembly to preserve its adhesive properties. The fabricated layers underwent microscopic inspection using a ZEISS Axioscope 5 microscope (ZEISS, Germany) equipped with 1X, 5X, and 10X optical lenses. Any imperfections, such as wrinkles or surface defects, necessitated immediate layer replacement to maintain dimensional accuracy and consistency across all chips. After quality assessment, each layer was precisely aligned and bonded under controlled pressure to ensure the structural integrity of the assembled device, thereby enabling reproducible fluid path progression.

Imaging setup and video acquisition

To capture high-resolution visual data of fluid path progression within the CMC, video acquisition was performed using either smartphones or DSLR cameras, each supporting at least 4 K resolution with a minimum frame rate of 30 frames per second (fps). The selection of 4 K resolution ensured fine-detail capture of microfluidic structures, while the 30-fps frame rate was sufficient for tracking rapid capillary-driven fluid path progression, specifically during rapid transitions at sharp directional changes or geometric inflections and where variations in flow dynamics could significantly impact fluid distribution.

Video preprocessing and format conversion

Videos were recorded from multiple sources, each with varying frame rates, resolutions, and encoding formats to ensure model generalization across diverse imaging conditions. To standardize input data for fluid path analysis, raw video files were processed using Python and the OpenCV library, which facilitated efficient frame extraction and format conversion. To preserve image quality and maintain essential metadata, extracted frames were stored in PNG format, chosen for its lossless compression properties and ability to retain fine microscale features (e.g., splits, sharp edges, corners) without introducing artifacts. During the conversion process, key video attributes, including frame rate, pixel dimensions, and total frame count, were logged into a structured Python dictionary. This metadata was subsequently used to ensure frame alignment during annotation, maintain consistency across data augmentation steps, and optimize segmentation model training.

Ground-truth annotation and labelling

To generate precise segmentation masks for model training, we developed a custom user interface in Python using OpenCV and Tkinter. This tool facilitated semi-automated annotation of fluid path progression by integrating both automated detection and manual refinement functionalities. Initially, an optimal hue–saturation–value (HSV) range was heuristically selected based on the optical properties of the fluid to approximate the fluid path within each frame. Then we iteratively refine these selections by interactively adding desired fluid path regions or removing falsely highlighted areas using a brush-based segmentation approach. This process ensured the precise delineation of fluid path structures, minimizing the inclusion of background noise or irrelevant regions. The annotated masks were stored as binary segmentation maps alongside their corresponding PNG frames, forming a structured dataset crucial for supervised deep learning-based segmentation. This structured dataset was subsequently used to train deep learning segmentation models, ensuring accurate identification of fluid path progression across varying experimental conditions.

Frame resizing and Spatial normalization

The extracted video frames served as the primary dataset for fluid path analysis, requiring preprocessing steps to ensure uniformity and compatibility with deep learning models. Image preprocessing encompassed both resizing and normalization to maintain consistency across the dataset. Each input image was defined by three main parameters: width (W), height (H), and number of channels (C), represented as W × H × C. Given that the dataset consisted of RGB images, C was set to 3. To standardize input dimensions across the training pipeline, all images were resized to 512 × 512 × 3, a resolution chosen to balance fine-detail preservation with computational efficiency.

Data augmentation strategies

To enhance dataset diversity, improve model generalization, and mitigate overfitting, image augmentation techniques were applied using the Albumentations library within the PyTorch framework. Augmentation strategies were carefully selected to simulate real-world variations in CMC experiments, ensuring robustness against fluid path orientation changes, channel misalignment, and fluid dispersion variability. The applied transformations included image rotation (to account for varying chip orientations) and both vertical and horizontal flipping (to model symmetric fluidic behaviors). These augmentations mitigated positional biases, enhancing the model’s adaptability to diverse experimental conditions and ensuring robust fluid path segmentation. Additionally, for binary segmentation in fluid path analysis, image rescaling was applied by a factor of 1/255, normalizing pixel values to the range [0,1]. This normalization step ensured compatibility with deep learning models by standardizing input intensities, facilitating more stable training and improved model interpretability.

Segmentation models

For fluid path segmentation in CMC, we employed five state-of-the-art deep learning models. The following five architectures were evaluated for their potential in segmenting capillary-driven flow in microfluidic images. U-Net49a widely used convolutional neural network for biomedical image segmentation, features a symmetric encoder–decoder structure with skip connections that preserve spatial details during up-sampling. This architecture enables high-resolution segmentation using limited training data and is well-suited for microfluidic applications where precise localization of fluid boundaries is required, despite low contrast or variable geometry. Pyramid Attention Network (PAN)50 improves segmentation accuracy by integrating global attention mechanisms and multi-scale feature extraction. Its attention modules emphasize salient spatial features and guide prediction refinement, making it valuable for detecting fluid fronts and component edges under variable lighting and background conditions. Feature Pyramid Network (FPN)51 constructs a multi-scale feature pyramid by combining deep semantic features with high-resolution shallow features through lateral connections. This fusion supports accurate segmentation of both fine structures, such as thin channels, and broader regions within microfluidic systems. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network (PSP-Net)52 captures both global and local context using pyramid pooling, which aggregates information from multiple spatial scales. This contextual awareness helps differentiate between visually similar regions, enhancing performance in parsing complex chip layouts or overlapping flow zones. DeepLabV3 +53 combines atrous convolutions with a lightweight decoder and an Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module to extract rich multi-scale context and refine object boundaries. This makes it particularly effective for segmenting fluids and materials in microfluidic images where edge clarity is essential under varying imaging conditions.

Each model was specifically selected for its ability to perform pixel-level classification, a fundamental requirement for delineating fluid paths with high precision. These models employ multi-scale feature extraction and hierarchical representations to accurately segment fluid paths at varying spatial resolutions, ensuring precise delineation across diverse chip designs54. The applied segmentation models utilized feature extraction to identify spatial patterns within CMC images, enabling accurate classification of fluid path regions55.

Model training and configurations

To further enhance segmentation performance, each model was paired with a carefully selected encoder backbone, responsible for extracting rich feature representations from input images. These encoder backbones differ in complexity, efficiency, and depth, offering unique advantages for microfluidic image analysis under varying computational and data constraints. MobileNetV256 is a lightweight architecture optimized for efficiency through the use of depthwise separable convolutions. It enables rapid segmentation with a low parameter count, making it particularly suitable for applications with limited training data or computational resources. ResNet-50 and its deeper variant, ResNet-10157, leverage residual connections to capture complex hierarchical features, supporting accurate segmentation of intricate structures. EfficientNetB358 utilizes compound scaling to balance depth, width, and resolution, achieving high segmentation accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency. ResNeXt50-32 × 4d57 enhances model capacity through grouped convolutions, which improve feature diversity and facilitate segmentation of subtle textures and fine microfluidic structures.

These encoders were chosen for their efficient feature extraction capabilities, parameter optimization, and strong generalization performance across diverse image datasets. Transfer learning enabled the models to leverage pre-trained feature representations, significantly reducing computational costs while enhancing segmentation accuracy. The sigmoid activation function was utilized, mapping pixel-wise probability distributions for binary segmentation tasks, ensuring precise classification of fluid path regions. This activation function maps pixel intensities to a probability range of [0,1], facilitating precise delineation of fluid path regions. The dataset, consisting of 150 labeled CMC images29was split into 90% training and 10% validation to ensure a balanced model evaluation strategy.

Model training and evaluation

During the training and evaluation phases of the CMC segmentation models, we implemented an iterative training approach with a batch size of 8, chosen to balance computational efficiency and convergence stability. To monitor segmentation performance and prevent overfitting, we tracked Intersection over Union (IoU)59 and Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) metrics against loss values per epoch. IoU measures the degree of overlap between the predicted segmentation mask and the ground truth, calculated as the ratio of the intersection to the union of the two regions. It is useful for evaluating the spatial accuracy of segmentation boundaries. DSC, also known as the F1-score in binary segmentation, quantifies the harmonic mean of precision and recall and is especially sensitive to false positives and false negatives. In this project, both metrics were critical for evaluating how precisely the models captured the fluid path in capillary microfluidic chips, where even small segmentation errors can significantly affect downstream quantification of fluid displacement.

Our model investigation was conducted using PyTorch60which allowed for efficient model training and evaluation. The dataset, consisting of 150 RGB images (total size: 43 MB), was uploaded to GitHub for accessibility. Training was performed on Kaggle, leveraging an NVIDIA Tesla P100 GPU, which provided free computational resources while ensuring rapid model iterations. Each segmentation model was trained for 60 epochs, with total computational time amounting to 2 h across all models.

To further improve segmentation performance, we fine-tuned hyperparameters by experimenting with different learning rates and optimizers. The Adam optimizer61 with a learning rate of 0.0001 was found to achieve optimal results due to its adaptive learning rate mechanism, which stabilizes training while avoiding sharp gradient updates.

Transfer learning with a pre-trained ImageNet model62 was implemented to expedite convergence, leverage hierarchical feature extraction, and improve generalization across varying CMC states of filling. Although we initially trained for 60 epochs, performance metrics plateaued around the 57th epoch, prompting a reduction in the number of epochs to save computational resources without compromising segmentation accuracy. Future optimizations could incorporate early stopping to dynamically adjust training duration based on validation performance.

Post-processing and output refinement

To enhance the accuracy of fluid path progression analysis, a custom post-processing algorithm was developed in Python using OpenCV. This algorithm was designed to refine segmentation outputs by filtering irrelevant regions and improving visualization clarity. The post-processing pipeline applied an area-based clustering algorithm to consolidate spatially coherent pixel clusters, refining segmentation outputs for improved fluid path analysis. This approach allowed for the removal of small, irrelevant segments while retaining only significant fluid regions, ensuring a more robust and interpretable representation of capillary-driven flow. By incorporating this clustering-based refinement step, the fluid path progression output was significantly improved by reducing background interference, enhancing segmentation reliability, and improving interpretability in fluid path progression analysis. The refined output was then used for quantitative fluid path assessment, facilitating accurate evaluation of fluid dynamics within the CMC.

Conclusion and future work

This study introduced AI-CMCA, an automated deep-learning framework for fluid path analysis in capillary microfluidic chips (CMCs). By integrating segmentation models and quantitative flow analysis, AI-CMCA significantly improved accuracy, reproducibility, and efficiency in tracking capillary-driven fluid movement. Experimental validation demonstrated that AI-CMCA outperformed manual tracking, reducing processing time from hours to minutes while maintaining high segmentation accuracy. The framework effectively handled a range of microfluidic architectures with different complexities, including straight channels, merging/splitting junctions, serpentine networks, and two previously established POC testing devices, highlighting its scalability for diverse applications.

Future development of AI-CMCA will focus on enhancing its adaptability and scalability to meet the diverse challenges of real-world microfluidic environments. A key priority is extending the framework to capture complex fluidic phenomena such as multi-phase flows, stagnation zones, and concentration-gradient dipoles, critical in applications like immunoprecipitation assays and programmable mixing. Achieving this will require algorithmic advancements, including temporal smoothing, adaptive clustering, and the integration of physics-informed priors to improve segmentation near sharp corners and during burst-like front propagation.

To increase robustness and generalizability, future datasets will incorporate a wider range of environmental variables, including lighting conditions, fluid transparency, imaging angles, and chip alignment. This will allow the model to perform reliably in non-ideal, field-deployable, or portable systems, beyond the confines of controlled laboratory settings.

Scalability to high-throughput and real-time applications is another major objective. Although the current implementation operates on pre-recorded videos, its frame-wise architecture is well-suited for integration with live video streams. Future work will include real-time video processing combined with motion stabilization and dynamic preprocessing to mitigate issues from vibration, variable lighting, and camera orientation. Validation across diverse microfluidic modalities will assess the generalizability of AI-CMCA, with early tests already demonstrating encouraging results. To reduce manual annotation and accelerate model refinement, we will integrate active learning strategies and evaluate foundation models such as Meta AI’s Segment Anything Model (SAM).

By advancing both algorithmic sophistication and system-level integration, AI-CMCA aims to establish a new class of intelligent microfluidic analysis tools. Through expanded datasets, real-time adaptability, and multi-platform validation, AI-CMCA is positioned to transform the automation of fluidic experimentation. Beyond improving throughput and precision in laboratory workflows, this platform holds promise for accelerating discovery and deployment in biomedical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and the broader field of microfluidic system engineering.

Data availability

The dataset supporting this study, comprising 150 images and corresponding ground truth masks, is publicly accessible at https://github.com/Mkh23/Fluid-Paths-Detection. The code utilized for deep learning model training, encompassing data preprocessing, model architecture, training routines, and evaluation metrics, is available at https://github.com/EsmaeilShakeri/Chips-Path-Analysis. These resources enable the replication of the study’s findings and facilitate further research in capillary microfluidic chip analysis.

References

Pattanayak, P. et al. Microfluidic chips: recent advances, critical strategies in design, applications and future perspectives. Microfluid Nanofluidics. 25, 1–28 (2021).

Whitesides, G. M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature 442, 368–373 (2006).

Shajari, S. et al. MicroSweat: A wearable microfluidic patch for noninvasive and reliable sweat collection enables human stress monitoring. Adv Sci 10, 2204171 (2023).

Salahandish, R. et al. A compact, low-cost, and binary sensing (BiSense) platform for noise-free and self-validated impedimetric detection of COVID-19 infected patients. Biosens. Bioelectron. 213, 114459 (2022).

Songok, J. & Toivakka, M. Controlling capillary-driven surface flow on a paper-based microfluidic channel. Microfluid Nanofluidics. 20, 1–9 (2016).

Chin, C. D., Linder, V. & Sia, S. K. Commercialization of microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic devices. Lab. Chip. 12, 2118–2134 (2012).

Oldach, B., Fortmann, R., Pleie, T., Timm, P. & Kockmann, N. Design and rapid prototyping of 3D-Printed microfluidic systems for multiphase flow. Chemistry 6, 1458–1476 (2024).

Squires, T. M., Quake, S. R. & Microfluidics Fluid physics at the nanoliter scale. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 977–1026 (2005).

Rizzuto, V. et al. Combining microfluidics with machine learning algorithms for RBC classification in rare hereditary hemolytic anemia. Sci. Rep. 11, 13553 (2021).

Khanjani, E. et al. Capillary microfluidics for diagnostic applications: fundamentals, mechanisms, and capillarics. Front. Lab. Chip Technol. 4, 1502127 (2025).

Kriel, F. H., Sedev, R. & Priest, C. Capillary filling of nanoscale channels and surface structure. Isr. J. Chem. 54, 1519–1532 (2014).

Saha, A. A., Mitra, S. K., Tweedie, M., Roy, S. & McLaughlin, J. Experimental and numerical investigation of capillary flow in SU8 and PDMS microchannels with integrated pillars. Microfluid Nanofluidics. 7, 451–465 (2009).

Saha, D. et al. Two-step fabrication of clear view SLA millifluidic device for long-term in-vitro cultures. Rapid Prototyp. J. 31, 316–326 (2025).

Yang, S. M., Lv, S., Zhang, W. & Cui, Y. Microfluidic Point-of-Care (POC) devices in early diagnosis: A review of opportunities and challenges. Sensors 22, 1620 (2022).

Haghayegh, F., Salahandish, R., Zare, A., Khalghollah, M. & Sanati-Nezhad, A. Immuno-biosensor on a chip: a self-powered microfluidic-based electrochemical biosensing platform for point-of-care quantification of proteins. Lab. Chip. 22, 108–120 (2022).

Salahandish, R., Hassani, M., Zare, A., Haghayegh, F. & Sanati-Nezhad, A. Autonomous electrochemical biosensing of glial fibrillary acidic protein for point-of-care detection of central nervous system injuries. Lab. Chip. 22, 1542–1555 (2022).

Zare, A. et al. CapSense-MIP: Self-operating molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) biosensor for point-of-care diagnostics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 286, 117599 (2025).

Rueden, C. T. et al. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinform. 18, 529 (2017).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 676–682 (2012).

Sarıyer, R. M. et al. Time-and distance-resolved robotic imaging of fluid flow in vertical microfluidic strips: a new technique for quantitative, multiparameter measurement of global haemostasis. Sens. Diagnostics. 2, 1623–1637 (2023).

Marchant-Ludlow, R. et al. Automated Flow Tracking Software for Capillary Microfluidic Devices. in. 39th International Conference on Image and Vision Computing New Zealand (IVCNZ) 1–6 (IEEE, 2024). (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/IVCNZ64857.2024.10794446

Xue, Q., Wainright, A., Gangakhedkar, S. & Gibbons, I. Multiplexed enzyme assays in capillary electrophoretic single-use microfluidic devices. Electrophoresis 22, 4000–4007 (2001).

Vinoth, R., Nakagawa, T., Mathiyarasu, J. & Mohan, A. M. V. Fully printed wearable microfluidic devices for high-throughput sweat sampling and multiplexed electrochemical analysis. ACS Sens. 6, 1174–1186 (2021).

Lukezic, A., Vojir, T., ˇCehovin Zajc, L., Matas, J. & Kristan, M. Discriminative correlation filter with channel and spatial reliability. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 6309–6318 (2017).

Gao, M. et al. Deep learning for video object segmentation: a review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 457–531 (2023).

Hadikhani, P., Borhani, N., Hashemi, H., Psaltis, D. & S. M. & Learning from droplet flows in microfluidic channels using deep neural networks. Sci. Rep. 9, 8114 (2019).

Sesen, M. & Whyte, G. Image-based single cell sorting automation in droplet microfluidics. Sci. Rep. 10, 8736 (2020).

Gu, J. et al. Recent advances in convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognit. 77, 354–377 (2018).

Khalghollah, M., Shakeri, E., Zare, A. & Far, H. B. & Sanati-Nezhad, A. Fluid Path Detection Model for Lab on a Chip Images Using Deep Learning-Based Segmentation Approach. Int. FLAIRS Conf. Proc. 37, (2024).

Ma, X. et al. Advances in integration, wearable applications, and artificial intelligence of biomedical microfluidics systems. Micromachines 14, 972 (2023).

Lecun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

DuPlissis, A. et al. Machine learning-based analysis of microfluidic device immobilized C. elegans for automated developmental toxicity testing. Sci. Rep. 15, 15 (2025).

Zhuang, F. et al. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proc. IEEE. 109, 43–76 (2020).

Fan, H. et al. A miniaturized microfluidic nanoplasmonic sensor with cavity reflection enhancement for ultrasensitive molecular interaction analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 499, 155896 (2024).

Kumar, K. S. & Juliet, A. V. Microfluidic droplet detection for bio medical application using YOLO with COA based segmentation. Evol. Syst. 16, 21 (2025).

Asama, R. et al. Droplet-based microfluidic platform for detecting agonistic peptides that are self-secreted by yeast expressing a G-protein-coupled receptor. Microb. Cell. Fact. 23, 104 (2024).

Shah, P. A., Shrivastav, P. S., Ghate, M. & Chavda, V. The fusion of microfluidics and artificial intelligence: a novel alliance for medical advancements. Bioanalysis 16, 927–930 (2024).

Narayanamurthy, V. et al. Advances in passively driven microfluidics and lab-on-chip devices: A comprehensive literature review and patent analysis. RSC Adv. 10, 11652–11680 (2020).

Gharib, G. et al. Biomedical applications of microfluidic devices: a review. Biosensors 12, 1023 (2022).

Oh, K. W., Lee, K., Ahn, B. & Furlani, E. P. Design of pressure-driven microfluidic networks using electric circuit analogy. Lab. Chip. 12, 515–545 (2012).

Lee, J. J., Berthier, J., Kearney, K. E., Berthier, E. & Theberge, A. B. Open-Channel capillary trees and capillary pumping. Langmuir 36, 12795–12803 (2020).

Zhang, X. & Lorente, S. The growth of capillary networks by branching for maximum fluid access. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–10 (2023).

O’Connell, K. C. & Landers, J. P. Integrated membranes within centrifugal microfluidic devices: A review. Lab. Chip. 23, 3130–3159 (2023).

Zai, Y. et al. Gravity-driven flow control in a fully integrated microfluidic cartridge for molecular point‐of‐care testing. Electrophoresis 45, 1142–1154 (2024).

Salahandish, R., Haghayegh, F., Khetani, S., Hassani, M. & Nezhad, A. S. Immuno-affinity potent strip with pre-embedded intermixed PEDOT: PSS conductive polymers and graphene nanosheets for bio-ready electrochemical biosensing of central nervous system injury biomarkers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 14, 28651–28662 (2022).

Xiang, J. et al. Directional fluid spreading on microfluidic chip structured with microwedge array. Phys Fluids 35, 062005 (2023).

Yuan, H. et al. Programmable gravity Self-Driven microfluidic chip for Point‐of‐Care multiplied immunoassays. Small 20, 2310206 (2024).

Kashaninejad, N. & Nguyen, N. T. Microfluidic solutions for biofluids handling in on-skin wearable systems. Lab. Chip. 23, 913–937 (2023).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. in Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5–9, proceedings, part III 18 234–241 (Springer, 2015). (2015).

Li, H., Xiong, P., An, J. & Wang, L. Pyramid attention network for semantic segmentation. arXiv Preprint arXiv1805.10180 (2018).

Lin, T. Y. et al. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 2117–2125 (2017).

Zhao, H., Shi, J., Qi, X., Wang, X. & Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 2881–2890 (2017).

Wang, Y., Wang, C., Wu, H. & Chen, P. An improved Deeplabv3 + semantic segmentation algorithm with multiple loss constraints. PLoS One. 17, e0261582 (2022).

Chowdhary, C. L. & Acharjya, D. P. Segmentation and feature extraction in medical imaging: a systematic review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 167, 26–36 (2020).

Li, X. et al. A comprehensive review of computer-aided whole-slide image analysis: from datasets to feature extraction, segmentation, classification and detection approaches. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55, 4809–4878 (2022).

Sandler, M., Howard, A., Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A. & Chen, L. C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 4510–4520 (2018).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 770–778 (2016).

Tan, M., Le, Q. & Efficientnet Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. in International conference on machine learning 6105–6114PMLR, (2019).

Rezatofighi, H. et al. Generalized intersection over union: A metric and a loss for bounding box regression. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 658–666 (2019).

Paszke, A. et al. PyTorch: an imperative style, High-Performance deep learning library. Adv Neural Inf. Process. Syst 32, arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.01703 (2019).

Kingma, D. P., Ba, J. & Adam A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv Preprint arXiv1412.6980 (2014).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM. 60, 84–90 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), NSERC CREATE Wearable Technology Research and Collaboration (We-TRAC) Training Program (Project No. CREATE/511166-2018), Alberta Innovates, University of Calgary.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: M.K., A.Z., A.SN.; experimentation & data acquisition: M.K., A.Z.; data analysis and/or interpretation: M.K., A.Z., E.S., B.H., A.SN.; Software and coding: M.K., E.S.; drafting and revising the manuscript: M.K., A.Z., E.S., B.H., A.SN.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalghollah, M., Zare, A., Shakeri, E. et al. AI-CMCA: a deep learning-based segmentation framework for capillary microfluidic chip analysis. Sci Rep 15, 26415 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11508-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11508-7