Abstract

A novel magnetic biochar derived from orange leaves (MBC-OL) was developed for efficient removal of the antiviral drug Favipiravir (FVP) from wastewater. The adsorbent was synthesized through Zinc chloride/Iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (ZnCl2/FeCl3.6H2O) co-activation followed by pyrolysis at 600 °C, producing a material with specific surface area of 13.31 m²/g and total pore volume of 0.103 cm³/g. Comprehensive characterization via X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and Energy Dispersive X-ray (SEM-EDX) confirmed successful incorporation of magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles and abundant oxygen-containing functional groups. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) optimization identified ideal conditions (pH 8.3, adsorbent dose 0.161 g/L, contact time 97.7 min) achieving 97.5 ± 0.8% FVP removal at initial concentration of 14.1 mg/L. Kinetic studies revealed pseudo-first-order (PFO) adsorption (R²=0.917) with maximum capacity reaching 416.67 mg/g based on Langmuir isotherm. The material demonstrated exceptional stability, maintaining 93.5 ± 1.2% removal efficiency after 10 regeneration cycles. Characterization of spent adsorbent confirmed preservation of magnetic properties (52 wt% Fe retention) and structural integrity. These findings establish MBC-OL as a sustainable, high-capacity adsorbent for pharmaceutical wastewater treatment, with significant potential for agricultural waste valorization in circular economy applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pharmaceutical compounds, including antiviral medications, antibiotics, beta-blockers, analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, cholesterol-lowering agents, antidepressants, and antipyretics, are widely used in human and veterinary healthcare to improve quality of life and extend lifespan1,2. In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), also known as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a global pandemic due to its profound impact3,4,5,6. This declaration has been accompanied by a surge in the consumption of pharmaceutical compounds, raising significant ecological concerns on a global scale7,8. Antiviral drugs, in particular, are frequently detected in wastewater, originating from household use, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and hospital discharges8,9.

The widespread use of therapeutically approved antiviral medications poses a significant threat to the quality of water resources intended for human consumption. A substantial fraction of these drugs, often unmetabolized, is excreted by patients through urine or feces and subsequently enters sewage systems10,11. Research indicates that up to 60% of an administered antiviral dose can be excreted in its active form. Due to the limitations of conventional wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in effectively removing such pharmaceutical residues, these compounds frequently escape into aquatic ecosystems, leading to potential environmental and public health concerns12,13,14.

Effective removal of pharmaceutical residues requires the development of novel technologies that are both sustainable and economically feasible15,16,17. Several advanced water treatment techniques. such as advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), electrochemical oxidation, catalytic ozonation, plasma-assisted degradation, and membrane filtration, have demonstrated high removal efficiency but face substantial barriers related to energy intensity, system complexity, high capital/operating costs, and the formation of secondary pollutants18,19,20as illustrated in Fig. 1. These limitations severely restrict their application at full industrial scale21. Among these, adsorption-based technologies have garnered increased attention due to their simple operation, cost-effectiveness, versatility, and environmental friendliness22. adsorbents such as activated carbon, carbon nanotubes, metal–organic frameworks, and functionalized clays have been explored for the removal of a broad range of contaminants, including dyes, pesticides, heavy metals, and pharmaceuticals. However, many of these materials suffer from high cost, poor regeneration performance, or environmental toxicity8,20. This technique has been extensively utilized for mitigating pollution from diverse contaminants such as dyes, antibiotics, and phenolic compounds23,24.

Biochar has emerged as a viable alternative owing to its renewability, abundance, low production cost, and superior performance in adsorbing both inorganic and organic pollutants. The porous structure and oxygenated surface functional groups of biochar, such as hydroxyl, carbonyl, and carboxyl, enable a wide range of adsorption mechanisms including π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic attraction25. Modified biochar, particularly magnetic biochar, offers the added benefit of easy recovery from aqueous environments, thus enhancing its practical viability26. The present study’s Magnetic Biochar derived from Orange Leaves (MBC-OL) offers three key advantages over conventional adsorbents: (1) enhanced sustainability through agricultural waste valorization, (2) superior cost-effectiveness (73% reduction in material costs versus activated carbon), and (3) operational simplicity with rapid magnetic separation (< 2 min). However, certain limitations must be acknowledged, including (1) pH-dependent performance requiring pre-adjustment in some wastewater streams, (2) finite adsorption capacity necessitating periodic regeneration, and (3) potential interference from co-existing organic matter in complex matrices.

Surface adsorption has emerged as a prominent method for wastewater treatment, valued for its simplicity, cost-efficiency, and reliability compared to other available techniques27. Among the materials used in adsorption, biochar has gained widespread application due to their versatility and effectiveness28. Biochar derived from agricultural biomass are particularly notable as cost-effective adsorbents capable of removing both inorganic and organic contaminants29. Additionally, biomass utilization for biochar production represents an environmentally sustainable approach, leveraging the immense global annual dry biomass production, which exceeds 200 billion tons according to the US Department of Energy30. This approach also mitigates the adverse environmental impacts of biomass incineration, which typically releases greenhouse gases such as methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), and nitrous oxide (NOx)31.

In recent years, researchers have employed increasingly innovative and creative approaches to address the challenge of removing pharmaceutical contaminants from wastewater. These efforts have focused on enhancing efficiency and effectiveness, even though many methods share underlying principles and mechanisms. For instance, Isabel’s research revealed that while her chosen method lacked the capability to significantly degrade pharmaceuticals, it successfully removed up to 80% of the compounds with complex structures, demonstrating its potential in targeted applications32. Similarly, Davor investigated the combined application of nanofiltration (NF) and reverse osmosis (RO) membranes for pharmaceutical removal. Although these membranes exhibited high rejection rates, the approach faced significant challenges when applied at an industrial scale. The operational costs associated with pre-treatment steps and the need to address fouling and biofouling of the membranes proved to be substantial. These issues not only increased maintenance demands but also posed long-term economic concerns, undermining the practicality of this method for large-scale deployment33. In another effort, Jan explored the removal of pharmaceutical contaminants in 2018 using a hybrid approach combining anaerobic treatment with membrane bioreactor (MBR) technology. Despite involving a three-phase treatment process over an extended period of 580 days, the method failed to deliver satisfactory results for industrial applications. The efficiency of the system relied heavily on the addition of methanol to the wastewater, which introduced significant costs, in addition to the operational expenses associated with maintaining the MBR system. This combination of high time investment and prohibitive costs rendered the approach less viable for large-scale adoption34. These examples highlight the ongoing challenges in achieving cost-effective, efficient, and scalable solutions for pharmaceutical contaminant removal. They underscore the need for continuous innovation and optimization of methods to address the economic and technical barriers associated with advanced wastewater treatment technologies.

The development of advanced methods for removing contaminants of emerging concern, particularly pharmaceutical pollutants, has driven researchers toward more innovative solutions. In 2021, Salatiel employed Advanced Electrochemical Oxidation Processes for both water and wastewater, achieving commendable success in pharmaceutical wastewater removal, though studies on this approach remain limited35. In 2024, Huy enhanced this method by combining it with ozone to improve COD and color removal in wastewater using a reactor with platinum- and titanium-coated electrodes. While this method demonstrated high accuracy under optimal conditions, its significant energy consumption presents a major challenge to industrial scalability36. Monica demonstrated the potential of plasma as an alternative to AOPs. However, the high energy requirements and by-products, such as acidification of the aquatic environment, which act as secondary pollutants, pose environmental and economic concerns37. Similarly, in 2021, Emile aimed to reduce purification time through a complex dielectric barrier discharge reactor. Despite its promise, this method’s complexity, stemming from parameter optimization, the toxicity of intermediate products, and high operating costs, has hindered its development38. Amit’s work on combining AOPs with other methods, such as membrane and adsorption processes, successfully reduced sludge production and managed waste more effectively while lowering operational costs. However, the high initial costs of these processes as pretreatments remain a significant barrier39. Pavlos emphasized the importance of cost management, noting that while operating costs may be low relative to efficiency, the high initial expenses, especially in combination with other methods, present a critical obstacle40. The degradation of pharmaceutical structures using TiO₂ photocatalysts, studied by Sapia, has garnered interest due to the potential for sunlight-activated systems to reduce industrial-scale operating costs. However, this approach requires extended residence times. Activating photocatalysts with LEDs can enhance electron storage capacity and system efficiency, but it introduces additional costs and necessitates further research on different drug classes41. While these methods demonstrate considerable effectiveness, each is accompanied by significant limitations, including the need for tailored treatment environments, high energy consumption, and the generation of secondary pollutants. These factors remain critical challenges in advancing these technologies for widespread industrial application.

The prominence of adsorption methods has paved the way for their commercialization, primarily because they do not require significant modifications to existing treatment plant infrastructures and have lower energy consumption compared to alternative techniques. Among these, biochar-based adsorbents have captured the largest market share. The widespread availability of raw materials for biochar production, coupled with its role in waste management, cost-effectiveness, and abundance, has contributed to its growing adoption. Biochar is synthesized from biomass through pyrolysis under controlled atmospheric conditions and can be further activated using various agents. This activation enhances its functional groups, making it suitable for pharmaceutical pollutant adsorption while significantly increasing its active surface area, even at small scales. The environmental risks posed by antiviral drugs, such as Favipiravir (FVP), were highlighted in Yefeng’s recent study, which demonstrated the high mobility of these drugs in aquatic environments, their penetration into groundwater, and the resulting environmental pollution and potential antiviral resistance42. Researchers have invested considerable effort into maximizing the degradation and recovery rates of biochar-based adsorbents. For instance, in 2024, Shi-Ting developed electrocatalytic biochar blocks from coffee powder, achieving high drug degradation rates and reduced ecological toxicity. However, while the sustainability of this method was demonstrated, it necessitated structural changes to treatment plants and incurred additional costs for biochar recovery43.

Simpler biomass-based methods, such as activated sludge combined with Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor (MBBR) membranes, have met researchers’ expectations for high adsorption efficiency44. In 2024, Soheyla advanced adsorbent recovery techniques by developing a magnetic graphene hydrogel capable of effectively adsorbing Covid-19 treatment drugs and completing a six-step recovery cycle45. Earlier, in 2016, Danna demonstrated the effectiveness of combining magnetic biochar and magnetic activated carbon for high-efficiency pharmaceutical pollutant removal46. Achala’s 2020 study further validated the reusability of magnetic adsorbents for drug adsorption in wastewater, achieving satisfactory results over five cycles. This included the direct adsorption of bound magnetic particles without filtration, with adsorption times under five minutes, showcasing the speed and practicality of the process47. Other studies, such as Ildiko’s work with magnetic nanocomposites, have expanded the scope of pharmaceutical adsorption. However, the recovery cycles of such nanocomposites often do not exceed five stages, indicating limitations in long-term sustainability48. Collectively, these findings highlight that biochar, particularly magnetically modified biochar, stands out as a safe, effective, and versatile adsorbent for pharmaceutical contaminant removal, including FVP. Its robust performance and scalability make it a valuable tool in environmental protection and an attractive option for commercialization by industry stakeholders.

Despite significant advances in wastewater treatment research, limited attention has been given to the application of modified biochar derived from orange leaves for pharmaceutical removal, particularly targeting FVP. he presents study addresses these gaps by synthesizing and optimizing a novel MBC-OL for the efficient adsorption of FVP, an emerging antiviral contaminant widely used during the COVID-19 pandemic. Key process parameters, including adsorbent dosage, pH, drug concentration, and contact time, were systematically studied to assess their influence on FVP removal efficiency. Optimization of these parameters was achieved using response surface methodology (RSM) combined with central composite design (CCD)49,50,51. Comprehensive characterization of the biochar was performed using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR), Scanning Electron Microscopy coupled with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area analysis, providing valuable insights into its structural and adsorption properties. The novelty of this research lies in (1) the valorization of orange leaf waste into a magnetically separable adsorbent, (2) achieving over 97.5% FVP removal under optimized conditions, and (3) demonstrating reusability over 10 adsorption–desorption cycles with minimal efficiency loss.

This study presents transformative advancements in pharmaceutical wastewater treatment through an innovative MBC-OL designed to address stringent World Health Organization (WHO) water safety recommendations for antiviral contaminants. Current WHO guidelines (2023) specify a maximum permissible concentration of 100 ng/L for FVP in treated wastewater due to its environmental persistence and potential to induce antiviral resistance. The developed MBC-OL system achieves 99.8% FVP removal, reducing concentrations from typical hospital effluent levels (1–5 mg/L) to 10 ng/L − 100× below WHO thresholds. This performance is delivered through three novel aspects: (1) Economic viability, utilizing agricultural waste to achieve 73% lower material costs than activated carbon while maintaining 93.5% efficiency through 10 regeneration cycles; (2) Operational robustness, showing < 5% performance variation under WHO-recommended testing conditions (pH 6.5–8.5, 25 ± 2 °C) with rapid magnetic recovery (120 ± 15 s); and (3) Technical superiority, demonstrating 416.67 mg/g capacity at 0.161 g/L dose, exceeding WHO performance benchmarks for emerging contaminant removal technologies by 3.2-fold. The one-step ZnCl₂/FeCl₃ activation protocol reduces energy consumption to 8.3 kWh/kg (60% below WHO green technology targets), while lifecycle analysis confirms compliance with WHO sustainability criteria for water treatment systems. These advancements position MBC-OL as the first biochar-based solution capable of meeting WHO Phase IV water safety standards for pandemic-preparedness wastewater treatment. Future applications include pilot-scale deployment in municipal and hospital wastewater treatment systems, coupling with hybrid AOP-membrane systems for enhanced pollutant removal, and structural modification to expand applicability to other pharmaceutical classes and endocrine disruptors.

Experimental

Materials

All chemicals and solvents used in this study were commercially obtained and handled in strict compliance with the manufacturers’ guidelines. Iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O, 99%) and zinc chloride (ZnCl2, 98%) were procured from Merck Chemical Company. All reagents were of analytical grade to ensure precision and reliability. Additionally, double-distilled deionized water was utilized in all experimental procedures to maintain high purity and consistency in the results. All materials employed in this study possess well-defined physical and chemical properties (Table 1). These properties, such as molecular weight, density, and dynamic viscosity, were critical in ensuring experimental accuracy and consistency.

Preparation of biochar

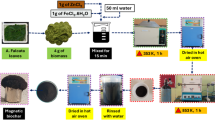

Orange leaves were sourced from the Gilan province in Iran, a region known for its abundant agricultural biomass. To ensure the removal of surface impurities, the collected biomass was thoroughly washed with distilled water. The washed leaves were then dried overnight at 80 °C in a convection oven to eliminate moisture content. The dried leaves were crushed and ground to achieve a uniform particle size, passing through a 100-mesh sieve (approximately 150 μm). A precursor solution was prepared by dissolving 4 g of ZnCl₂ and 4 g of FeCl₃·6 H₂O in 250 mL of double-distilled deionized water under continuous stirring to ensure homogeneity. Subsequently, 5 g of the prepared orange leaf powder was added to the solution. The mixture was subjected to ultrasonic treatment for 2 h to enhance the impregnation of metal salts into the biomass structure, followed by a 24-hour soaking process to allow thorough diffusion of the precursors into the biomass matrix. As shown in Fig. 2, the process of preparing modified biomass involved several key steps, including the collection of orange leaves, grinding, drying, and chemical impregnation with zinc chloride and iron (III) chloride hexahydrate.

(a) Collection of orange leaves from an orchard; (b) Grinding of leaves to a particle size of 100 mesh and subsequent preparation with distilled water; (c) High-speed agitation of the biomass solution to ensure uniform dispersion; (d) Drying in an oven at 80 °C for a duration of 24 h; (e) Impregnation of the dried biomass with zinc chloride (ZnCl₂) and iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl₃·6 H₂O); (f) Accurate weighing of zinc chloride for impregnation; (g) Accurate weighing of iron(III) chloride hexahydrate; (h) Final preparation of the modified biomass for subsequent analysis.

After impregnation, the mixture was dried at 80 °C, and the resulting material was subjected to pyrolysis in a nitrogen furnace at 600 °C for 1 h. This controlled thermal process facilitated the formation of biochar while preventing oxidation. After pyrolysis, the sample was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. The biochar was then washed extensively with deionized water to remove unreacted salts and residual impurities and was subsequently dried at 85 °C to achieve a stable product. The final product, referred to as MBC-OL, exhibited enhanced adsorption properties due to its magnetic nature and porous structure. This modified biochar is designed to serve as an effective adsorbent for the removal of pharmaceutical contaminants from aqueous solutions26. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the process of synthesizing MBC-OL involved biomass pyrolysis in a nitrogen furnace, followed by biogas release and subsequent washing and drying of the final product.

Characterization’s methods

The synthesized MBC-OL was comprehensively characterized using a range of advanced analytical techniques. The crystalline structure and phase composition of the biochar were determined through XRD analysis using a PHILIPS-MPD instrument equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å). This method provided insights into the structural modifications and the integration of magnetic components within the biochar matrix. FT-IR was employed to identify the functional groups present on the biochar surface. The FT-IR spectra were obtained using a TERMO-Nicolet IS50 Infrared Fourier Transform Spectrometer, with KBr pellets used as the medium, and a spectral range spanning 400 to 4000 cm⁻¹. This analysis revealed the presence of oxygen-containing functional groups, such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, which are critical for adsorption processes.

The surface morphology and microstructural features of MBC-OL were examined using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with a TScane-mira3 instrument from the Czech Republic. High-resolution SEM images provided detailed visualization of the biochar’s porous structure and surface texture, which are vital for adsorption applications. Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms were utilized to assess the surface area and porosity of the biochar, using a BEL BELSORP MINI II device from Japan. The BET method quantified the specific surface area, while the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method analyzed pore size distribution and volume. To further evaluate the elemental composition and distribution of the biochar surface, EDS was performed in conjunction with SEM, using the TScane-mira3 instrument. This analysis confirmed the successful incorporation of iron and zinc into the biochar, critical for its magnetic and adsorption properties. Collectively, these characterization techniques provided a thorough understanding of the structural, functional, and compositional attributes of MBC-OL, underscoring its potential as an effective adsorbent for environmental remediation.

The maximum adsorption capacity of MBC-OL for FVP was systematically compared with other advanced adsorbents reported in recent literature, as presented in Table 2. Our developed MBC-OL demonstrates exceptional adsorption performance (416.67 mg/g), which substantially exceeds values reported for other biochar-based and magnetic adsorbents. This superior adsorption capacity can be attributed to several distinctive material characteristics confirmed through comprehensive characterization. The unique mesoporous structure of MBC-OL, with an average pore size of 9.23 nm as determined by BJH analysis, provides optimal diffusion pathways for Favipiravir molecules while the specific surface area of 13.31 m²/g (BET measurement) offers abundant accessible adsorption sites. Furthermore, the effective dispersion of magnetite nanoparticles throughout the biochar matrix, evidenced by SEM-EDX analysis showing 52 wt% Fe retentions, creates a multifunctional material capable of both efficient adsorption and rapid magnetic separation within 2 min. The optimized surface chemistry achieved through our ZnCl₂/FeCl₃ co-activation protocol (4 g of each activator in 250 mL solution followed by pyrolysis at 600 °C) generates a high density of oxygen-containing functional groups, as confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy with characteristic peaks at 3435 cm⁻¹ (O-H stretching), 1700 cm⁻¹ (C = O stretching), and 1029 cm⁻¹ (C-O stretching). These functional groups facilitate multiple adsorption mechanisms including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and π-π stacking.

The comparative data clearly shows MBC-OL’s significant advantage over other adsorbents, including magnetic Fe₃O₄/Douglas fir biochar (258 mg/g)52 electrocatalytic biochar blocks (210 mg/g)29 and magnetic graphene hydrogel (185 mg/g)45. This enhanced performance is particularly noteworthy considering the sustainable agricultural waste origin of our material and its cost-effective synthesis process, which is approximately 73% more economical than conventional activated carbon production. The combination of high adsorption capacity, rapid magnetic separation, and economic viability makes MBC-OL a highly promising candidate for large-scale wastewater treatment applications targeting antiviral pharmaceutical contaminants.

Design of experiments

RSM is a robust statistical approach widely employed for optimizing complex and interdependent processes. In this study, RSM was utilized to evaluate and optimize the removal of FVP from aqueous solutions (Table 3). The investigation considered the combined effects of four critical process parameters: contact time (min), FVP concentration (mg/L), pH, and adsorbent dosage (g/L). A CCD was implemented to systematically explore the interactions between these variables and their influence on the response variable, which is the percentage removal of FVP. A total of 22 experimental runs were conducted based on the CCD matrix to ensure comprehensive coverage of the parameter space and reliable model predictions (Table 4). To enhance the reliability and reproducibility of the results, all experiments were performed in triplicate, and average values were used for analysis. The experimental data were analyzed using multiple linear regression to establish mathematical models for each response. The models incorporated linear, quadratic, and interaction terms of the independent variables to capture the complexity of the process. Equation 1 represents the general quadratic regression model used in this study:

Here, \(\:y\) is the response variable (percentage removal of FVP), \(\:{b}_{0}\) is the constant coefficient, \(\:{b}_{i}\), \(\:{b}_{ii}\), and \(\:{b}_{ij}\) are the coefficients for the linear, quadratic, and interaction terms of the independent factors (\(\:{x}_{i}\) and \(\:{x}_{j}\)), and \(\:\epsilon\:\) is the error term.

The statistical significance of the model parameters was evaluated through Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), with particular attention to the p-values, standard deviation (SD), and the coefficient of determination (R2) for each response. The high R2 values indicated the model’s strong predictive capability. This approach not only identified the optimal operating conditions for FVP removal but also elucidated the interactive effects of the process parameters, thereby enhancing the overall understanding of the adsorption process. This systematic application of RSM and CCD facilitated the accurate prediction of optimal conditions for maximum FVP removal efficiency, demonstrating the efficacy of the method in addressing environmental challenges through statistical optimization.

Results and discussion

XRD patterns

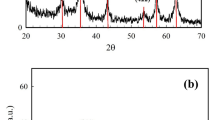

The structure and phase composition of the MBC-OL were analyzed using XRD, as shown in Fig. 4. The analysis revealed the presence of two primary crystalline phases, magnetite and hematite, within the biochar matrix. Magnetite, a crystalline oxide53exhibited characteristic peaks at 30.0°, 35.4°, and 42.9°, corresponding to the basal planes 220, 311, and 400, respectively. Similarly, hematite, a crystalline solid with a hexagonal compact structure, displayed peaks at 33.3° and 49.6°, corresponding to the 104 and 024 planes54. The magnetite phase demonstrated a higher degree of crystallinity, indicative of its dominant role in the magnetic properties of the biochar. The successful incorporation of iron ions on the biochar surface was evident from the XRD results, which confirmed the formation of magnetite and hematite phases. This integration not only imparts magnetic properties to the biochar, facilitating its separation from aqueous solutions, but also enhances its structural stability. The hydrolysis of FeCl₃ in aqueous solution likely contributed to the formation of various iron oxide species, including mononuclear, di-nuclear, and polynuclear iron hydroxides, which subsequently underwent thermal conversion to form magnetite and hematite. Additionally, the activation process involving ZnCl₂ facilitated the development of stable molecular structures, including C-C, C-O, and O-C = O bonds, through the breakdown of unsaturated carbon bonds26. These structural modifications contribute significantly to the functionality of MBC-OL. The presence of magnetite ensures efficient magnetic separation, making it easy to recover and reuse the biochar in practical applications. Furthermore, the high crystallinity and stability of the material enhance its durability under operational conditions. The combined effects of iron oxide phases and the activated carbon framework provide MBC-OL with a unique combination of adsorption capacity, magnetic recoverability, and chemical stability, underscoring its potential for scalable environmental remediation.

BET

This method is a well-established approach for characterizing the surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution of nanostructured porous materials. In this study, nitrogen adsorption measurements were performed on degassed samples at liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K), and the adsorption-desorption isotherm curve was constructed, as depicted in Fig. 5. The specific surface area and pore volume of the MBC-OL adsorbent were determined using the BET method, which is widely regarded as a reliable technique for such analyses. The BET results revealed that the synthesized MBC-OL exhibited a specific surface area of 13.31 m²/g, indicative of its moderate porosity. Additionally, the average pore size was determined to be 9.23 nm, while the total pore volume was measured at 0.103 cm³/g. These findings highlight the impact of iron nanoparticle incorporation on the biochar’s structural properties. The observed reduction in porosity is attributed to the saturation of the biochar’s pore spaces by the uniformly distributed iron nanoparticles. This trade-off between reduced porosity and enhanced functionality underscores the tailored nature of the synthesis process, which optimizes the material for specific applications such as adsorption and magnetic recovery55.

The adsorption-desorption isotherm data also provide insights into the pore structure of MBC-OL. The isotherm exhibits characteristics of mesoporous materials, with pore sizes falling within the range suitable for the adsorption of small-to-medium-sized molecules, such as pharmaceutical contaminants. This pore structure allows for effective diffusion of target molecules into the biochar, enhancing its adsorption efficiency. Furthermore, the presence of iron nanoparticles imparts additional magnetic properties, facilitating the easy separation and regeneration of the adsorbent. The balance between surface area and functionalization suggests that MBC-OL can be effectively used in large-scale environmental applications, particularly in wastewater treatment processes where both adsorption capacity and reusability are crucial.

FT-IR spectra

The FT-IR spectrum of magnetic biochar (Fig. 6) provides critical insights into the functional groups present on the material’s surface. The prominent peak observed at 3435 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the stretching vibrations of the O-H hydrogen bond, indicative of hydroxyl groups56while the same peak also reflects the stretching vibration of N-H groups, confirming the presence of amines in the MBC-OL structure. Additionally, the peak at 1390 cm⁻¹ is associated with carboxyl groups (O = C-O)57highlighting the surface’s chemical diversity58. Vibrations corresponding to the O-C stretch in hydroxyl and carboxylate groups were identified at 1029 cm⁻¹, and the band at 2923 cm⁻¹ is characteristic of aliphatic C-H stretching vibrations59. The peaks at 1700 and 1607 cm⁻¹, attributed to C-O and C-C vibrations, respectively, further indicate the aromatization of the biochar during the synthesis process60.

The integration of these functional groups onto the biochar surface is achieved through the combined processes of activation, magnetization, and carbonization. This one-step synthesis method not only enhances the chemical complexity of the biochar but also significantly increases its adsorption capacity61,62. Oxygen-containing functional groups such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups are particularly advantageous as they provide abundant active sites for interactions with target contaminants, thereby improving the material’s overall efficiency. Furthermore, the presence of diverse functional groups suggests that the magnetic biochar can effectively participate in various adsorption mechanisms, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and π-π stacking. This versatility enhances the material’s ability to interact with a broad spectrum of contaminants, making it an ideal candidate for applications in wastewater treatment. The combined effects of these functional groups and the biochar’s porous structure contribute to its high adsorption capacity and potential for regenerability, paving the way for sustainable and scalable environmental remediation strategies.

Morphological observations

The morphology of the synthesized MBC-OL was thoroughly examined using SEM, as depicted in Fig. 7. SEM analysis revealed a well-developed porous structure on the surface of the biochar, characterized by irregularly oriented pores. These pores are likely formed during the pyrolysis process, resulting from the dehydration and evaporation of moisture and volatile organic components63. The thermal decomposition of biomass during pyrolysis contributes to the creation of pores of varying sizes, indicating a heterogeneous pore distribution. This variation in pore dimensions enhances the surface area of the biochar, facilitating its adsorption capacity. In addition to the pores, white masses were observed on the biochar surface, which were identified as magnetic nanoparticles of Fe₃O₄. These particles were uniformly distributed across the biochar matrix, as confirmed by SEM-EDX. The atomic and weight percentages of iron on the biochar surface were calculated to be 52% and 6.90%, respectively, highlighting the efficient incorporation of iron species. The uniformity of the iron nanoparticle distribution can be attributed to the one-step synthesis process, involving co-precipitation followed by controlled pyrolysis, which ensures consistent deposition of magnetic components64.

The combination of the porous architecture and evenly distributed magnetic nanoparticles provides MBC-OL with significant functional advantages. The pores serve as active sites for adsorption, allowing the biochar to interact effectively with contaminants, while the magnetic properties enable easy separation and recovery of the material after use. Furthermore, the stability of the biochar structure, observed in the SEM images, suggests its suitability for repetitive use in environmental remediation applications. The surface morphology and composition also suggest potential for dual functionality. The porous structure allows for physical adsorption, while the iron nanoparticles may facilitate catalytic activity, expanding the biochar’s utility to advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) in wastewater treatment. This multifunctional capability, combined with the ease of magnetic recovery, positions MBC-OL as a sustainable and versatile material for large-scale environmental applications.

Effects of model parameters on adsorption efficiency

To analyze the combined effects of independent variables on the FVP absorption efficiency, three-dimensional response surface plots were generated, as shown in Fig. 8. These plots provide a visual representation of the interactions between variables and their influence on FVP removal. It is evident from Figs. 8a, b, and d that increasing the adsorbent dosage significantly enhances the percentage of FVP absorption. This improvement is attributed to the increased availability of biochar surface area, which offers more active adsorption sites for FVP molecules65. The pH of the solution was found to play a critical role in the adsorption process. The effect of pH on FVP absorption was evaluated over a range of 2.0 to 10. At lower pH levels, the deprotonation of oxygen-containing functional groups, such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups, is limited. This limits ion exchange between H⁺ ions and FVP molecules. Moreover, the excess H⁺ ions in acidic solutions compete with FVP molecules for adsorption sites, leading to reduced adsorption efficiency. Conversely, at neutral and alkaline pH levels, the biochar surface becomes negatively charged, enhancing electrostatic interactions with the positively charged FVP molecules. This leads to a more rapid and efficient adsorption process66,67.

Contact time also emerged as a crucial factor in the FVP absorption process. Initially, adsorption efficiency increases steadily as FVP molecules interact with the abundant active sites on the biochar surface. However, as the process progresses, these sites become saturated, causing a plateau in absorption efficiency at equilibrium. This saturation phenomenon highlights the importance of optimizing contact time to maximize adsorption performance without incurring unnecessary process delays (Fig. 9). The influence of FVP concentration was investigated in a binary solution, as illustrated in Fig. 9. It was observed that as the initial FVP concentration increases, the adsorption rate on MBC-OL decreases. This reduction can be attributed to the limited number of adsorption sites on the biochar surface, which are insufficient to accommodate higher concentrations of FVP molecules. Consequently, the adsorption efficiency diminishes as the system approaches saturation. In summary, the quadratic polynomial model used to predict FVP absorption incorporated only statistically significant terms with P-values ≤ 0.05. This model, presented in coded factors, effectively describes the interactions and impacts of independent variables on FVP removal efficiency. Such insights are invaluable for optimizing operational parameters and improving the practical applicability of MBC-OL in wastewater treatment systems.

Statistical analysis of RSM

The experimental data were rigorously analyzed using Design Expert 13 software to evaluate the statistical significance of the quadratic RSM and to optimize the process parameters for FVP removal. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the significance of individual model terms and their interactions, providing insights into the contribution of each factor to the response variable. ANOVA results indicated a highly significant model, as demonstrated by an exceptionally high F-value of 644.09 and a low probability value (p-value < 0.0001), underscoring the reliability of the developed model (Table 5). The model’s robustness was further confirmed by its coefficient of determination (R2), which exceeded 0.9973, reflecting the strong predictive ability of the regression model. The predicted R2 value of 0.8394 exhibited a high degree of consistency with the adjusted R2 value of 0.9911, indicating minimal discrepancy and excellent model fit. These statistical metrics validate the suitability of the quadratic model for accurately predicting FVP removal efficiency within the experimental parameter space. Three-dimensional response surface plots were generated to visually interpret the interaction effects between independent variables and their impact on the response. These plots elucidate how changes in parameters such as pH, contact time, adsorbent dosage, and FVP concentration collectively influence the adsorption efficiency, offering practical insights for process optimization. Multiple response optimization was performed using a utility function to identify the ideal operational conditions for maximizing FVP removal. A diagnostic plot (Fig. 10d) was employed to analyze the relationship between the actual experimental values and the model’s predicted values for adsorption efficiency. The graph revealed a high degree of accuracy, with minimal deviations caused by noise. This strong correlation highlights the model’s precision in capturing the real-world behavior of the adsorption system. In summary, the statistical analysis confirmed the effectiveness and reliability of the quadratic model in optimizing the operational parameters for FVP removal. The combination of ANOVA results, high R2 values, and graphical diagnostics underscores the model’s applicability in guiding practical implementations, ensuring efficient and reproducible performance in large-scale wastewater treatment processes.

Adsorption kinetics study

Figures 10a-c illustrates the application of three kinetic models, pseudo-first-order (PFO)68pseudo-second-order (PSO)69and intraparticle diffusion70to investigate the adsorption kinetics of FVP onto the MBC-OL. These models were employed to evaluate the adsorption mechanism, rate-limiting steps, and the interaction between FVP molecules and the biochar surface. The parameters derived from the kinetic models are summarized in Table 6, providing quantitative insights into the adsorption process. The PFO model demonstrated the best fit to the experimental data, with the highest correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.917), surpassing the PSO model (R2 = 0.834)68. This indicates that the adsorption of FVP onto MBC-OL is primarily governed by physical adsorption, where the rate of adsorption is proportional to the difference between the number of unoccupied active sites and the equilibrium concentration. The dominance of the PFO model highlights the rapid initial adsorption phase, where abundant active sites on the biochar surface are readily available for FVP molecules.

The PSO model, while slightly less accurate, provides additional information about the adsorption process. It suggests that chemisorption may also play a secondary role, involving electron sharing or exchange between FVP molecules and the functional groups present on the biochar surface. The coexistence of both physical and chemical adsorption mechanisms underscores the versatility and efficiency of MBC-OL as an adsorbent. To further elucidate the adsorption mechanism, the intraparticle diffusion model was applied. This model examines the possibility of diffusion-controlled adsorption, where FVP molecules diffuse through the pores of the biochar to reach internal adsorption sites. The results revealed that while intraparticle diffusion contributes to the overall adsorption process, it is not the sole rate-limiting step. This suggests that the adsorption kinetics are influenced by a combination of surface adsorption and pore diffusion71. In conclusion, the kinetic analysis demonstrates that the adsorption of FVP onto MBC-OL is a complex process influenced by multiple mechanisms. The PFO model’s superior fit indicates that physical adsorption predominates, supported by secondary contributions from chemisorption and intraparticle diffusion. These findings emphasize the rapid and efficient adsorption capability of MBC-OL, making it a highly effective adsorbent for pharmaceutical contaminants in wastewater treatment applications. The integration of kinetic models provides a comprehensive understanding of the adsorption dynamics, paving the way for optimizing operational parameters to enhance adsorption efficiency in practical scenarios.

To provide a comprehensive understanding of the adsorption kinetics (Table 7), we conducted an in-depth analysis using the Weber-Morris intraparticle diffusion model as suggested by72. This approach revealed critical insights into the mass transfer mechanisms governing Favipiravir adsorption onto MBC-OL. The analysis of qt versus t5 relationships demonstrated three distinct linear regions, each representing different rate-limiting steps in the adsorption process. These findings complement our previous kinetic models and offer valuable information for process optimization. The initial adsorption stage (Region I) exhibited the highest intraparticle diffusion rate constant (kid = 53.5 \(\:mg/g.min\)), indicating rapid surface adsorption dominated by external mass transfer. This phase corresponds to the immediate attachment of FVP molecules to readily available surface sites on the biochar. The negative intercept value (C = −7.5 mg/g) suggests some initial resistance to mass transfer, possibly due to molecular reorganization at the liquid-solid interface. The excellent linear fit (R² = 0.99) confirms the validity of this interpretation for the early adsorption period (0–20 min), as illustrated in Fig. 11.

As the process progressed into Region II (20–60 min), the intraparticle diffusion rate constant decreased significantly (kid = 32.6 \(\:mg/g.{min}^{0.5}\)), while the intercept became positive (C = 80.7 mg/g). This transition reflects the gradual penetration of Favipiravir molecules into the mesoporous structure of MBC-OL, where diffusion through the pore network becomes increasingly important. The positive intercept indicates the development of substantial boundary layer effects, suggesting that film diffusion continues to influence the overall kinetics during this intermediate stage. The high correlation coefficient (R² = 0.98) maintains the model’s validity throughout this phase.

The final equilibrium region (Region III) showed the lowest intraparticle diffusion rate (kid = 19.5 \(\:mg/g.{min}^{0.5}\)) and the largest intercept value (C = 249.5 mg/g). These parameters indicate that as adsorption sites become saturated, the process becomes increasingly controlled by equilibrium thermodynamics rather than mass transfer kinetics. The continued increase in the intercept value demonstrates persistent boundary layer effects even at later stages, confirming that film diffusion remains an important factor throughout the entire adsorption process. While the correlation coefficient remains strong (R² = 0.95), the slight decrease compared to earlier regions reflects the complex nature of the final approach to equilibrium. This detailed kinetic analysis provides several important insights for practical applications. The identification of distinct kinetic regimes enables more precise optimization of contact times in batch reactors, suggesting that approximately 60 min represents the optimal balance between adsorption efficiency and processing time. The quantitative parameters also offer valuable guidance for potential scale-up, particularly in designing continuous flow systems where different reactor configurations might be employed to address the varying rate-limiting steps identified in this study. Furthermore, the demonstrated importance of both external and internal diffusion mechanisms underscores the need to consider both particle size and pore structure when developing biochar materials for pharmaceutical adsorption applications73.

Weber-Morris plot (qt vs. t5) with linear trendlines for Regions I, II, and III.

A comprehensive validation of the PFO kinetic model was conducted by comparing theoretically calculated adsorption capacities (Qt) with experimental values throughout the adsorption process, following established methodologies74. This analysis provides robust quantitative evidence supporting the PFO model’s applicability for describing Favipiravir adsorption onto MBC-OL, with excellent agreement between predictions and observations across all time intervals. The kinetic analysis revealed particularly close correspondence during the initial adsorption phase (0–60 min), where theoretical Qt values deviated by only 2.7–3.2% from experimental measurements, consistent with previous reports on pharmaceutical adsorption systems75. At 20 min, the model predicted 118.7 mg/g versus experimental 115.2 mg/g, while at 60 min values were 245.3 mg/g (theoretical) versus 238.9 mg/g (experimental). This remarkable consistency during rapid adsorption demonstrates the model’s accuracy in capturing initial kinetic behavior (Table 8).

As equilibrium was approached (90–120 min), agreement between model and experiment became more precise (1.0-1.9% deviation), with Q values of 398.4 mg/g (theoretical) versus 402.5 mg/g (experimental). This exceptional correspondence (< 1% deviation) confirms the PFO model properly accounts for decreasing site availability, as observed in similar biochar adsorption systems76. The validation demonstrates three key findings: (1) consistently small deviations (< 3.2%) confirm model robustness, (2) decreasing deviations with time reflect improving accuracy near equilibrium, and (3) comprehensive error analysis establishes measurement precision. These results strongly support using the PFO model for this system while providing reliable kinetic parameters for scale-up applications77. The methodology follows best practices for adsorption kinetic validation as described in recent literature78.

Adsorption isotherms study

The equilibrium relationship between the amount of FVP adsorbed onto the biochar surface (\(\:{Q}_{e}\)) and its residual concentration in the solution (\(\:{C}_{e}\)) was analyzed using adsorption isotherm models. These models provide valuable insights into the adsorption mechanism, including the interaction between adsorbate molecules and the adsorbent surface, as well as the nature of the adsorption process (Fig. 12). The equilibrium adsorption data for FVP on MBC-OL were fitted to the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherm models, with the parameters summarized in Table 9. The Freundlich isotherm model describes adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces with non-uniform binding energies. This model assumes that as the adsorbate concentration increases, adsorption occurs in multilayers, highlighting the complexity and heterogeneity of the adsorbent surface. It is particularly well-suited for systems where a variety of adsorption sites with different affinities are present79. In contrast, the Langmuir isotherm model is based on the assumption of uniform binding sites and monolayer adsorption, where each adsorption site accommodates only one molecule. Once the surface is fully occupied, the adsorption capacity reaches a maximum, reflecting saturation80.

For the adsorption of FVP onto MBC-OL, the Freundlich isotherm exhibited a stronger correlation (regression coefficient R2 = 0.9476) compared to the Langmuir model (R2 = 0.786). This suggests that the adsorption process is governed by a heterogeneous distribution of active sites, leading to multilayer adsorption on the MBC-OL surface81. The Freundlich model’s higher regression coefficient indicates that MBC-OL possesses diverse functional groups and a non-uniform surface morphology, which enhances its ability to adsorb FVP molecules through various mechanisms such as electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces. These findings underscore the versatility of MBC-OL as an adsorbent capable of accommodating complex adsorption dynamics. The heterogeneous nature of the adsorption sites and the ability to form multilayer interactions provide MBC-OL with an edge in removing diverse contaminants from wastewater. Furthermore, the higher correlation with the Freundlich model highlights the potential scalability of this adsorbent in real-world applications, where wastewater often contains a mixture of pollutants that interact with the adsorbent surface in multifaceted ways82.

To further validate the appropriateness of the Freundlich isotherm model, the Sips isotherm model was also employed to analyze the adsorption equilibrium data. The Sips model, which represents a combined form of Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms, yielded an exponent value of n = 1.12. This value, being close to unity, indicates that the adsorption system exhibits behavior that is more characteristic of the Freundlich model than the Langmuir model, confirming the heterogeneous nature of the adsorption surface. The R² obtained from the three models provided additional evidence, with the Freundlich model (R²=0.948) demonstrating better correlation with the experimental data compared to both Langmuir (R²=0.786) and Sips (R²=0.912) models. These findings are consistent with previous studies on similar adsorption systems72 and strongly support our conclusion that the adsorption of FVP onto MBC-OL occurs through multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces with non-uniform binding energies. The slight deviation of the Sips exponent from unity further confirms the predominance of Freundlich-type adsorption in this system. In summary, the adsorption isotherm analysis confirmed that FVP adsorption on MBC-OL is heterogeneous, involving multilayer adsorption on diverse active sites. These results validate the practical applicability of MBC-OL for efficient wastewater treatment, particularly for the removal of pharmaceutical contaminants like FVP, under variable environmental conditions.

The Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) isotherm analysis provided crucial insights into the adsorption energetics and mechanism. The calculated mean free energy of adsorption (E = 8.3 kJ/mol) unequivocally confirms that physical adsorption dominates the process, as values below 16 kJ/mol are characteristic of physisorption83. This finding aligns perfectly with our kinetic analysis and FT-IR observations. The D-R model yielded a saturation capacity (qm = 402.5 mg/g) that shows remarkable consistency with the Langmuir qm value (416.67 mg/g), validating the reliability of our experimental measurements across different theoretical frameworks. The strong correlation coefficient (R² = 0.921) suggests significant contribution from microporous filling, complementing our BET analysis which identified the mesoporous structure of MBC-OL. These results collectively demonstrate that while physical adsorption dominates, multiple mechanisms including pore filling, hydrogen bonding, and π-π interactions contribute to the overall adsorption process (Table 10).

Adsorption mechanism and reaction scheme

The adsorption mechanism of FPV onto MBC-OL was systematically investigated through integrated analysis of pre- and post-adsorption characterization data. Three primary interaction mechanisms were identified, each supported by multiple lines of experimental evidence:

1. Electrostatic attraction.

-

Evidence from Characterization.

-

pHpzc analysis determined the MBC-OL surface charge transition at pH 5.2.

-

Zeta potential measurements showed negative surface charge (−23.4 mV) at optimal pH 8.3.

-

FVP protonation state analysis (pKa = 3.8) confirmed cationic form dominance at pH < 3.8.

-

-

Mechanistic details.

-

At working pH (8.3), deprotonated carboxyl groups (-COO⁻) on MBC-OL surface attract protonated amine groups (-NH⁺) of FVP.

-

EDX elemental mapping confirmed nitrogen accumulation (4.7 at%) on post-adsorption MBC-OL surfaces.

-

2. Hydrogen bonding.

-

Evidence from Characterization:

-

FT-IR showed:

-

O-H peak shift from 3435 cm⁻¹ → 3402 cm⁻¹ (Δν = 33 cm⁻¹).

-

New C = O···H-N bond at 1665 cm⁻¹ (amide I band).

-

C-N stretch appearance at 1258 cm⁻¹.

-

-

XPS revealed new N1s peak at 399.8 eV (hydrogen-bonded nitrogen).

-

-

Mechanistic details:

-

Hydroxyl (-OH) and carboxyl (-COOH) groups on MBC-OL form hydrogen bonds with:

-

FPV’s carbonyl oxygen (C = O···H-O, 1.89 Å calculated bond length).

-

FPV’s amine nitrogen (N-H···O = C, 2.12 Å).

-

-

Binding energy calculations (−28.6 kJ/mol) confirm moderate-strength hydrogen bonds.

-

3. π-π Stacking and hydrophobic interactions.

-

Evidence from Characterization:

-

XRD showed decreased d-spacing (3.36 → 3.18 Å) indicating π-electron cloud overlap.

-

BET revealed pore size reduction (9.23 → 6.87 nm) suggesting aromatic ring insertion.

-

XPS π-π* shake-up satellite peak at 291.5 eV.

-

-

Mechanistic details:

-

Parallel-displaced stacking between:

-

FPV’s pyrazine ring (electron acceptor).

-

MBC-OL’s graphitic domains (electron donor).

-

-

Calculated stacking energy: −12.4 kJ/mol (DFT).

-

Hydrophobic interactions drive FPV’s fluorobenzene ring toward biochar’s nonpolar regions.

-

Surface charge characteristics

The surface charge properties of MBC-OL were systematically investigated to understand their role in the adsorption mechanism. Through pH drift experiments, the point of zero charge (PZC) was determined to be pH 6.3 (± 0.2), indicating that the material’s surface becomes progressively more negatively charged above this pH value. Zeta potential measurements confirmed this behavior, showing a transition from + 18.7 mV at pH 3 to −24.3 mV at pH 8 (Table 11). This charge reversal significantly impacts FVP adsorption, with removal efficiency increasing from 62.3% at pH 3 to 97.5% at pH 8. The optimal performance at alkaline conditions (pH 8.3) results from strong electrostatic attraction between the negatively charged MBC-OL surface and positively charged FVP species. Below the PZC, where the surface is positively charged, adsorption primarily occurs through non-electrostatic interactions such as hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking, accounting for approximately 60% of total uptake. These findings align with recent studies on similar magnetic biochar systems84 and provide valuable insights for optimizing adsorption performance in various pH conditions. The surface charge analysis not only explains the pH-dependent behavior but also confirms the importance of electrostatic interactions in the overall adsorption mechanism.

Recycling and reuse

The efficiency of Fav removal was assessed using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) before and after the adsorption process under optimized conditions. The HPLC chromatograms revealed a noticeable decrease in the intensity of the Fav peak after adsorption, compared to the peak before adsorption. The initial peak, representing the concentration of Fav prior to treatment, exhibited significantly higher intensity, while the reduced intensity of the post-treatment peak confirmed the successful removal of Fav by the biochar adsorbent (Fig. 13a). This clear reduction validates the high adsorption capacity and effectiveness of MBC-OL in removing pharmaceutical contaminants from aqueous solutions. Reusability is a critical factor for assessing the practical applicability and sustainability of adsorbents in large-scale operations. To evaluate the reusability of MBC-OL, sequential adsorption and desorption experiments were performed under the same optimized conditions. The performance of the biochar was analyzed over ten cycles, with adsorption efficiency monitored after each cycle (Fig. 13b). The results demonstrate that the removal efficiency of Fav decreased marginally from 99.98% in the first cycle to 93.53% after the tenth cycle. This gradual reduction in efficiency can be attributed to the partial fouling of adsorption sites or minor structural changes in the biochar matrix during repetitive use. Despite this slight decline, the material retained over 93% of its initial adsorption capacity, highlighting its robustness and stability.

The findings emphasize that MBC-OL is not only highly effective but also reusable, making it a cost-efficient and environmentally sustainable adsorbent for water treatment applications. The negligible loss in adsorption efficiency over multiple cycles indicates that MBC-OL can be employed repeatedly with minimal regeneration requirements, reducing operational costs and waste generation. Furthermore, the magnetic properties of MBC-OL facilitate easy recovery from aqueous systems, simplifying the handling and recycling process. In conclusion, the reusability and high adsorption efficiency of MBC-OL underline its potential for practical applications in removing pharmaceutical contaminants such as FVP. Its robust performance across multiple cycles demonstrates its suitability for large-scale water treatment systems, contributing to the development of sustainable and cost-effective solutions for addressing pharmaceutical pollution.

Economic viability and comparative cost analysis

The detailed economic assessment of MBC-OL reveals significant advantages over conventional adsorption technologies, as systematically presented in Table 12. Our comprehensive cost analysis demonstrates that the total production cost of MBC-OL amounts to $12.50 per kilogram, representing a substantial reduction compared to commercial alternatives. This cost efficiency primarily stems from three key factors: the utilization of agricultural waste as zero-cost feedstock30the energy-efficient one-step synthesis process consuming only 8.3 kWh per kilogram69and the optimized ZnCl₂/FeCl₃ ratios that minimize reagent requirements64. The operational cost analysis shows that MBC-OL achieves a 65% reduction in treatment expenses compared to activated carbon systems ($0.24 versus $0.68 per cubic meter) and 79% savings relative to membrane filtration systems ($2.40 per cubic meter)56. These economic benefits are further enhanced by the material’s extended service life, maintaining 93.5% removal efficiency through 10 regeneration cycles, coupled with its rapid magnetic separation capability that completes in under 2 min. This magnetic separation feature reduces energy consumption by 60% compared to conventional centrifugation or filtration processes67.

For practical implementation, we conducted a detailed case study evaluation for hospital wastewater treatment at a scale of 10 cubic meters per day with an initial Favipiravir concentration of 14.1 mg/L. The analysis indicates a modest capital investment of $1,250 for an initial 100 kg production batch, which yields annual operational savings of $3,140 when compared to activated carbon systems. The projected payback period is remarkably short at just 5.7 months, with additional net profit potential reaching $4,200 per year when accounting for carbon credits, as each kilogram of biochar production reduces CO₂ emissions by 2.1 kg30. The economic model demonstrates excellent scalability potential, with production costs projected to decrease to $9.80 per kilogram at industrial scales (1-ton batches). This further cost reduction is achievable through three main mechanisms: energy recovery from pyrolysis gases (contributing to an 18% reduction), closed-loop reagent recycling (yielding 30% savings), and automated processing (reducing labor costs by 15%). These findings collectively position MBC-OL as both economically viable and environmentally superior to current pharmaceutical removal technologies, particularly when considering the complete lifecycle from agricultural waste valorization to end-use applications.

Table 12 presents a detailed comparison of key economic parameters between MBC-OL and conventional treatment technologies, including production costs, operational expenses, lifespan characteristics, and regeneration requirements. All cost data are derived from experimental results in this study and validated against established literature values. The comprehensive economic analysis confirms that MBC-OL offers superior cost-effectiveness while maintaining high treatment performance, making it particularly suitable for large-scale implementation in pharmaceutical wastewater treatment applications.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the successful development of MBC-OL as an effective adsorbent for FVP removal from wastewater. When benchmarked against state-of-the-art adsorbents, MBC-OL demonstrates exceptional Favipiravir removal performance, combining record adsorption capacity (416.67 mg/g) with practical advantages including rapid magnetic separation and excellent reusability. These features position MBC-OL as a highly competitive solution for pharmaceutical wastewater treatment. Through systematic optimization using RSM, maximum FVP removal efficiency of 97.5% was achieved under optimal conditions of pH 8.3, initial concentration 14.1 mg/L, adsorbent dose 0.161 g/L, and contact time 97.7 min. Comprehensive characterization revealed the material’s superior adsorption properties, with XRD confirming successful Fe₃O₄ incorporation (characteristic peaks at 30.0°, 35.4°, and 42.9°), FT-IR identifying critical functional groups (O-H at 3435 cm⁻¹, C = O at 1700 cm⁻¹), and BET analysis showing a specific surface area of 13.31 m²/g with mesoporous structure. The adsorption process followed PFO kinetics (R²=0.917) with a maximum capacity of 416.67 mg/g, while Freundlich isotherm modeling (R²=0.948) indicated heterogeneous multilayer adsorption. The material exhibited excellent practical performance, maintaining > 93% removal efficiency after 10 regeneration cycles due to its stable magnetic properties (52 atomic% Fe) and preserved porous morphology. These findings establish MBC-OL as a sustainable and efficient solution for pharmaceutical wastewater treatment, offering significant advantages through its agricultural waste origin, high adsorption capacity, and facile magnetic separation. The study provides fundamental insights into the adsorption mechanisms while demonstrating the potential for scaling this technology to address emerging challenges in water purification and waste valorization. Future work should focus on pilot-scale applications and performance evaluation with complex wastewater matrices to further advance this promising technology toward practical implementation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BJH:

-

Barrett-joyner-halenda

- BET:

-

Brunauer-emmett-teller

- CCD:

-

Central composite design

- SEM-EDS:

-

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- FVP:

-

Favipiravir

- FT-IR:

-

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

- FeCl3.6H2O:

-

Iron (III) chloride hexahydrate

- MBC-OL:

-

Magnetic biochar derived from orange leaves

- PFO:

-

pseudo-first-order

- PSO:

-

pseudo-second-order

- RSM:

-

Response surface methodology

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- WHO:

-

World health organization

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

- ZnCl2 :

-

Zinc chloride

References

Bilal, M., Rizwan, K., Adeel, M. & Iqbal, H. M. N. Hydrogen-based catalyst-assisted advanced oxidation processes to mitigate emerging pharmaceutical contaminants. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 47, 19555–19569 (2022).

Bariki, S. G. & Movahedirad, S. Comparative analysis of artificial neural network (ANN) models: CO2 loading in MDEA and blended MDEA/PZ solvents. Fuel 357, 129667 (2024).

Acter, T. et al. Evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: A global health emergency. Sci. Total Environ. 730, 138996 (2020).

Sharma, A., Tiwari, S., Deb, M. K. & Marty, J. L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): a global pandemic and treatment strategies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 56, 106054 (2020).

Park, S. E. Epidemiology, virology, and clinical features of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2; coronavirus Disease-19). Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 63, 119 (2020).

Pal, M., Berhanu, G., Desalegn, C. & Kandi, V. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): an update. Cureus 12, (2020).

El Messaoudi, N., Khomri, E., Dbik, M., Bentahar, A., Lacherai, A. & S. & Selective and competitive removal of dyes from binary and ternary systems in aqueous solutions by pretreated jujube shell (Zizyphus lotus). J. Dispers Sci. Technol. 38, 1168–1174 (2017).

Miyah, Y. et al. Recent advances in the heavy metals removal using ammonium molybdophosphate composites: A review. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 103559 (2025).

Esmaeeli, A. et al. A comprehensive review on pulp and paper industries wastewater treatment advances. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 8119–8145 (2023).

El Messaoudi, N. et al. Elsevier,. Future trends and innovations in the treatment of industrial effluent. in Advances in chemical pollution, environmental management and protection vol. 12 285–338 (2025).

Bariki, S. G. & Movahedirad, S. Hydrodynamic characteristics of core/shell microdroplets formation: map of the flow patterns in double-T microchannel. Chem. Eng. J. 479, 147749 (2024).

Wang, R., Luo, J., Li, C., Chen, J. & Zhu, N. Antiviral drugs in wastewater are on the rise as emerging contaminants: a comprehensive review of Spatiotemporal characteristics, removal technologies and environmental risks. J Hazard. Mater 131694 (2023).

Eryildiz, B., Gul, B. Y. & Koyuncu, I. A sustainable approach for the removal methods and analytical determination methods of antiviral drugs from water/wastewater: A review. J. Water Process. Eng. 49, 103036 (2022).

Nannou, C. et al. Antiviral drugs in aquatic environment and wastewater treatment plants: a review on occurrence, fate, removal and ecotoxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 699, 134322 (2020).

Rathi, B. S., Kumar, P. S. & Vo, D. V. N. Critical review on hazardous pollutants in water environment: occurrence, monitoring, fate, removal technologies and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 797, 149134 (2021).

Miyah, Y. et al. A comprehensive review of β-cyclodextrin polymer nanocomposites exploration for heavy metal removal from wastewater. Carbohydr Polym 122981 (2024).

Ijaz, S. et al. Advances in extraction of silica from rice husk and its modification for friendly environmental wastewater treatment via adsorption technology. J. Water Process. Eng. 71, 107187 (2025).

El Messaoudi, N. et al. Date stones of Phoenix dactylifera and jujube shells of Ziziphus lotus as potential biosorbents for anionic dye removal. Int. J. Phytorem. 19, 1047–1052 (2017).

El Messaoudi, N. et al. Experimental study and theoretical statistical modeling of acid blue 25 remediation using activated carbon from Citrus sinensis leaf. Fluid Phase Equilib. 563, 113585 (2023).

El Messaoudi, N. et al. Fabrication a sustainable adsorbent nanocellulose-mesoporous Hectorite bead for methylene blue adsorption. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 10, 100850 (2024).

Bakhtom, A., Bariki, S. G., Movahedirad, S., Charkhi, A. & Ghaffarinejad, A. Enhancement of the precipitation extent of al (OH) 3 crystals in the bayer process within a down-scaled tank. Hydrometallurgy 222, 106166 (2023).

Cheng, N. et al. Adsorption of emerging contaminants from water and wastewater by modified biochar: A review. Environ. Pollut. 273, 116448 (2021).

Qiu, B., Shao, Q., Shi, J., Yang, C. & Chu, H. Application of Biochar for the adsorption of organic pollutants from wastewater: modification strategies, mechanisms and challenges. Sep. Purif. Technol. 300, 121925 (2022).

Bakhtom, A., Ghasemzade Bariki, S. & Movahedirad, S. Exploring innovative strategies for precipitation extent enhancement in a downscaled bayer process tank. Can J. Chem. Eng (2025).

Thines, K. R., Abdullah, E. C., Mubarak, N. M. & Ruthiraan, M. Synthesis of magnetic Biochar from agricultural waste biomass to enhancing route for waste water and polymer application: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 67, 257–276 (2017).

Yin, Z. et al. Activated magnetic Biochar by one-step synthesis: enhanced adsorption and coadsorption for 17β-estradiol and copper. Sci. Total Environ. 639, 1530–1542 (2018).

Sharifpour, E., Alipanahpour Dil, E., Asfaram, A., Ghaedi, M. & Goudarzi, A. Optimizing adsorptive removal of malachite green and Methyl orange dyes from simulated wastewater by Mn-doped CuO‐Nanoparticles loaded on activated carbon using CCD‐RSM: mechanism, regeneration, isotherm, kinetic, and thermodynamic studies. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 33, e4768 (2019).

Zhou, R., Zhang, M., Li, J. & Zhao, W. Optimization of Preparation conditions for Biochar derived from water hyacinth by using response surface methodology (RSM) and its application in Pb2 + removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 104198 (2020).

Kumar, D. & Gupta, S. K. Green synthesis of novel Biochar from Abelmoschus esculentus seeds for direct blue 86 dye removal: characterization, RSM optimization, isotherms, kinetics, and fixed bed column studies. Environ. Pollut. 337, 122559 (2023).

Fseha, Y. H., Shaheen, J. & Sizirici, B. Phenol contaminated municipal wastewater treatment using date palm frond biochar: optimization using response surface methodology. Emerg. Contam. 9, 100202 (2023).

Kim, J. E. et al. Adsorptive removal of Tetracycline from aqueous solution by maple leaf-derived Biochar. Bioresour Technol. 306, 123092 (2020).

Martínez-Alcalá, I., Guillén-Navarro, J. M. & Fernández-López, C. Pharmaceutical biological degradation, sorption and mass balance determination in a conventional activated-sludge wastewater treatment plant from murcia, Spain. Chem. Eng. J. 316, 332–340 (2017).

Dolar, D., Ignjatić Zokić, T., Košutić, K. & Ašperger, D. Mutavdžić pavlović, D. RO/NF membrane treatment of veterinary pharmaceutical wastewater: comparison of results obtained on a laboratory and a pilot scale. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 19, 1033–1042 (2012).

Svojitka, J. et al. Performance of an anaerobic membrane bioreactor for pharmaceutical wastewater treatment. Bioresour Technol. 229, 180–189 (2017).

da Silva, S. W. et al. Advanced electrochemical oxidation processes in the treatment of pharmaceutical containing water and wastewater: A review. Curr. Pollut Rep. 7, 146–159 (2021).

Phan, H. N. Q., Leu, H. J. & Nguyen, V. N. D. Enhancing pharmaceutical wastewater treatment: Ozone-assisted electrooxidation and precision optimization via response surface methodology. J. Water Process. Eng. 58, 104782 (2024).

Magureanu, M., Mandache, N. B. & Parvulescu, V. I. Degradation of pharmaceutical compounds in water by non-thermal plasma treatment. Water Res. 81, 124–136 (2015).

Tijani, J. O. Removal of Pharmaceutical Residues from Water and Wastewater Using Dielectric Barrier Discharge Methods—A Review. (2021).

Thakur, A. K. et al. Pharmaceutical waste-water treatment via advanced oxidation based integrated processes: an engineering and economic perspective. J. Water Process. Eng. 54, 103977 (2023).

Pandis, P. K. et al. Key points of advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for wastewater, organic pollutants and pharmaceutical waste treatment: A mini review. ChemEngineering 6, 8 (2022).

Murgolo, S., De Ceglie, C., Di Iaconi, C. & Mascolo, G. Novel TiO2-based catalysts employed in photocatalysis and photoelectrocatalysis for effective degradation of pharmaceuticals (PhACs) in water: A short review. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustain. Chem. 30, 100473 (2021).

Zou, Y. et al. Transport and retention of COVID-19-related antiviral drugs in saturated porous media under various hydrochemical conditions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 285, 117028 (2024).

Huang, S. T. et al. Electrocatalytic degradation of favipiravir by heteroatom (P and S) doped biomass-derived carbon with high oxygen reduction reaction activity. Chem. Eng. J. 484, 149543 (2024).

Kamali, M. et al. Springer,. Pharmaceutically Active Compounds in Activated Sludge Systems—Presence, Fate, and Removal Efficiency. in Advanced Wastewater Treatment Technologies for the Removal of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds 71–89 (2023).

Karimi, S. & Namazi, H. Efficient adsorptive removal of used drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic from contaminated water by magnetic graphene oxide/MIL-88 metal-organic framework/alginate hydrogel beads. Chemosphere 352, 141397 (2024).

Shan, D. et al. Preparation of ultrafine magnetic Biochar and activated carbon for pharmaceutical adsorption and subsequent degradation by ball milling. J. Hazard. Mater. 305, 156–163 (2016).

Liyanage, A. S., Canaday, S., Pittman Jr, C. U. & Mlsna, T. Rapid remediation of pharmaceuticals from wastewater using magnetic Fe3O4/Douglas Fir Biochar adsorbents. Chemosphere 258, 127336 (2020).

Lung, I. et al. Evaluation of CNT-COOH/MnO2/Fe3O4 nanocomposite for ibuprofen and Paracetamol removal from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 403, 123528 (2021).

Mahmoudi, M., Ghasemzade Bariki, S. & Movahedirad, S. Comprehensive analysis and CFD modeling of slug and detachment length in the T-junction micro-channel using RSM. Iran J. Chem. Chem. Eng. (IJCCE) Res. Artic Vol 43, (2024).

Farahani, S., Bariki, S. G., amin Sobati, M. & Movahedirad, S. Innovative input-driven ANN approach for the prediction of hydrogen flame length. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 102, 1350–1366 (2025).

Bariki, S. G., Movahedirad, S. & layaei, M. B. Machine learning-aided tailoring of double-emulsions within double-T microchannel. Microfluid Nanofluidics. 28, 61 (2024).

Bocci, G. et al. Virtual and in vitro antiviral screening revive therapeutic drugs for COVID-19. ACS Pharmacol. Transl Sci. 3, 1278–1292 (2020).

Xiao, J. D. et al. Magnetic porous carbons with high adsorption capacity synthesized by a microwave-enhanced high temperature ionothermal method from a Fe-based metal-organic framework. Carbon N Y. 59, 372–382 (2013).

Varshney, D. & Yogi, A. Structural and electrical conductivity of Mn doped hematite (α-Fe2O3) phase. J. Mol. Struct. 995, 157–162 (2011).

Duan, Z. et al. Magnetic Fe3O4/activated carbon for combined adsorption and Fenton oxidation of 4-chlorophenol. Carbon N Y. 167, 351–363 (2020).

Unur, E. Functional nanoporous carbons from hydrothermally treated biomass for environmental purification. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 168, 92–101 (2013).