Abstract

The solutions obtained from rare earth element (REE) processing are often acidic. The low pH is a challenge in the separation of REE. Hence, this study focuses on separating Ce(III) from acidic solutions by the ion exchange method using Dowex 50W-X8 resin. In the batch system, the maximum of Ce(III) exchange occurred at a resin dosage of 0.16 g, temperature of 35 °C, and sulfuric acid concentration of 0.2 M. The Ce(III) exchange process achieved equilibrium in 6 h with a capacity of 10.34 mg g−1, and the kinetic behavior was best fitted with the pseudo-second-order model (R2 = 0.999). The Langmuir model was followed among the isotherm models, which showed that adsorption occurred in the monolayer. The thermodynamic study revealed that the process was endothermic and spontaneous. In the continuous system, the Ce(III) exchange was carried out for 26 h, and the breakthrough curve obtained was the best fit with the Thomas kinetic model (R2 = 0.963). Resin regeneration was performed by passing a 3 M sulfuric acid solution through a fixed bed column, resulting in 98.81% desorption. Finally, to understand the Ce(III) exchange behavior in a real medium, the process was investigated in a simulated solution containing Th(IV) and Fe(II) ions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rare earth elements (REEs) consist of 15 elements of the lanthanide group from La to Lu, and two elements, Sc and Y1. Cerium (Ce) is the second lanthanide element with a periodicity of 6 and an atomic number of 58. Among the REE, cerium, with a concentration−1 of 66 mg kg−1, is the most abundant in the Earth’s crust2. Cerium metal has a bright silvery white color and is widely used in glass polishing, solar panels, LEDs, petroleum-cracking catalysts, automotive converters, alloys, and permanent magnets3,4,5. Cerium compounds are also used in various industries. The increased requests for cerium compounds have led to more release of this element in the environment6. Cerium is the most plentiful REE in the industrial waste stream7. Cerium has potential toxicity and can disrupt the life of living organisms. In addition, when released into the environment, it not only contaminates water, soil, and air, but it may also enter the food chain, and through inhalation and skin contact, it creates risks to human health6,8. Hence, properly managing cerium waste streams is essential6.

It is also essential to investigate the methods of REE separation from minerals (primary source) and their recovery from manufactured products containing these elements (secondary source)9,10,11,12. Currently, the exploitation of REEs is generally performed using four main techniques: extraction/pre-concentration, purification, separation, and refining. Chemical, physical, electrical, and biological methods can perform these techniques10. Ion exchange (IX) is a purification technique in the category of chemical methods10,13. The ion exchange technique appears to be effective and promising9,14. It offers advantages such as simplicity in application, cost-effectiveness, high separation capacity, and low energy consumption. In addition, it can be used on a large scale9,15,16.

Caiping17 investigated the adsorption and desorption of Ce(III) on D151 resin in the buffer solution prepared from acetic acid and sodium acetate (HAc-NaAc). Adsorption of Ce(III) occurred optimally at pH = 6.5. The maximum adsorption capacity of Ce(III) was 392 mg g−1 at 298 K. In investigating the adsorption isotherm, the Langmuir model was the most consistent, although the equilibrium data were also in good agreement with the Freundlich model. In the continuous system, the adsorption capacity was 321 mg g−1. Cao et al.18 investigated the adsorption of rare elements La(III), Ce(III), and Y(III) from aqueous solution using Poly (6-acryloylamino-hexyl hydroxamic acid) (PAMHA) synthetic resin. The maximum adsorption capacity of Ce(III) on PAMHA was 134.8 mg g−1. Their thermodynamic and isotherm studies showed that the adsorption process followed the Langmuir model and was spontaneous (ΔG° = − 13.924 kJ mol−1) and endothermic (ΔH° = 22.75 kJ mol−1).

Miller et al.19 used Dowex 50W-X8 resin for the reversible ion exchange of Ce2(SO4)3 and Ce (NO3)3 from a solution containing anionic solutes. Experimental findings in continuous flow reactor studies showed that the adsorption capacity for cerium nitrate was 234.81 mg g−1 and for cerium sulfate was 318.95 mg g−1. Ghazala20 used cation exchange resin (Dowex 50W-X8) to study the extraction of REEs from uranium concentrate. The maximum REEs adsorption capacity was 82.47 mg g−1, equivalent to 93.23% of the initial capacity of the studied resin. Recently, Dowex 50W-X8 resin has also been used for the separation of other REE such as Y, La, Nd, Yb, Pr, and Dy21,22,23.

Allahkarami and Rezaei6 reviewed past studies on the removal of Ce(III) from aqueous solutions (studies from 1998 to 2018). They evaluated the performance of different adsorbents under different conditions (including contact time, initial concentration, solution acidity, temperature, and presence of competing ions).

REEs are often associated with radioactive elements such as thorium and uranium in various minerals24,25. Iron is also found in many REE deposits, which reduces the efficiency of the process26. For leaching REEs from various sources (including ore, coal, fly ash, bottom ash, etc.) Sulfuric acid is widely used, and the leaching process is usually done at a low pH27,28,29,30,31. As a result, to extract REEs, leach liquors with high acidity are placed in contact with various organic solvents and adsorbents28,29,30. The existence of interfering elements in leach liquors and low pH of the media can be mentioned as the challenges of processing REEs32.

Conventionally, to achieve optimal conditions, the separation of the desired element from the aqueous solution is studied first. Especially, the separation of REEs from aqueous solutions is crucial for various industries and technologies33. Moreover, the recovery of REEs from aqueous solutions is essential for sustainable resource management and reducing dependence on limited natural deposits34.

In the present study, the ion exchange of Ce(III) from aqueous solutions with high acidity, which has not been addressed in previous studies, was investigated. This study aimed to examine the performance of Dowex 50W-X8 resin in Ce(III) ion exchange from aqueous solutions (with high acidity) in batch and continuous systems for the first time. In this article, the effect of process variables is analyzed separately and simultaneously. The kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics of the process have been investigated. The study of dynamic columns with a simulated solution has also been investigated to obtain a helpful understanding of the ion exchange process of Ce(III) from the real medium.

Materials and methods

Materials

The experiments were performed using Dowex 50W X8 resin with a mesh size of 100–200. Cerium nitrate hexahydrate (Ce(NO3)3.6H2O) was used as the source of Ce(III) ions. Sulfuric acid was used to prepare aqueous solutions with different acidity, and nitric acid was used to prepare the resin preparation solution. Thorium nitrate hexahydrate (Th(NO3)4.6H2O) and Iron(II) chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2.4H2O) were also used to prepare a simulated solution. All materials used were of laboratory-grade purity and were used without further purification. The specifications of the Dowex 50W-X8 resin (mesh size 100–200) and the experimental material are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Experimental instrumentals

In the experiments, a digital scale (Mettler Toledo B204-S) was used to measure the weight of the materials. The experiments were performed in a batch system using a mechanical shaker (Gallencamp). Moreover, an inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (ICP AES, Optima 7300DV) was used to measure the ion concentration in the solutions. In addition, experiments were performed in a fixed bed column with a height of 6 cm and a diameter of 1.2 cm, and a peristaltic pump (Shenchen BT400N) was used to transfer the solution to the fixed bed column.

Resin preparation

To perform all experiments, the resin was first placed in a 0.1 M nitric acid solution. After 24 h, the resin was separated using filter paper. The resin was then washed with distilled water, filtered again, and utilized.

Ion exchange experiments in the batch system

In the batch experiments, the performance of the resin in ion exchange of Ce(III) from aqueous solutions was measured by experimental design. Experiments were designed using the response surface method (RSM) in Design Expert 11 (Stat-Ease, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) software. Central Cubic Design (CCD) is a quadratic application used in RSM that incorporates five levels for each independent variable. This design includes a central point and two factorial points positioned at ± 1 unit from the central point. Additionally, two-star points facilitate the estimation of curvature, located at a distance of ± α from the central point35. The independent variables of acid concentration in aqueous solution (A), temperature (B), and resin dosage (C) were studied using the CCD approach at 5 levels (α = 2), as shown in Table 3.

To perform batch experiments, at first, aqueous solutions with different acidity were prepared, all of which had an initial concentration of 50 mg L−1 Ce(III). In all the batch experiments, the volume of the aqueous solution was equal to 50 mL, and this volume of the aqueous solution with different amounts of resin was transferred to an Erlenmeyer flask (with a volume of 100 mL). The Erlenmeyer was then placed in a shaker with a rotation speed of 150 rpm, a contact time of 24 h, and different temperatures. Finally, the solutions were passed through a filter paper, and the remaining concentration of Ce(III) in the solutions was measured using an ICP AES device. The schematic of the ion exchange batch system is shown in Fig. 1. The percentage of ion exchange and the ion exchange capacity of the resin were calculated using Eqs. (1)36,37 and (2)38,39, respectively.

C0 (mg L−1) represents the initial concentration, and Ce (mg L−1) represents the equilibrium concentration. V (L) is the solution volume, and m (g) is the resin mass.

Ion exchange experiments in the continuous system

To perform continuous experiments, an aqueous solution with an acidity of 0.6 M and an initial concentration of 50 mg L−1 of Ce(III) was prepared. The column was then filled with Dowex 50W-X8 resin (mesh 100–200). The feed solution (influent) was sent to the fixed bed column at a flow rate of 0.96 mL min−1 at ambient temperature (25 °C) by a peristaltic pump. To prevent bed channelization, the influent solution was introduced from the bottom of the fixed bed column. Also, the concentration of Ce(III) in the output solution of the fixed bed column (effluent) was measured by sampling at different time intervals.

In the continuous system, the duration of the effectiveness of the resins and the time of their saturation can be observed by plotting the breakthrough curve. According to the definition, the break time (tb) is the time when the ion concentration in the effluent solution is equal to 5% of its concentration in the influent solution. Also, saturation time (ts) is defined as when the ion concentration in the effluent solution is equal to 95% of its concentration in the influent solution40.

Moreover, the overall efficiency of fixed-bed columns is strongly related to the length of the mass transfer zone (MTZ) that develops during the contact of solid and liquid phases. Because during the ion exchange process, the entire length of the column does not participate in the mass transfer phenomenon at the same time, rather, the ion exchange takes place only in a certain length of the column, which is located between the saturated adsorbent and the virgin adsorbent41,42.

The length of the MTZ, ion exchange capacity, and the percentage of ion exchange are calculated using Eqs. (3)43, (4)44, and (5)45, respectively.

where h (cm) is the length of the bed, tb (min) is break time, ts (min) is saturation time, Q (mL min−1) is the flow rate of the influent solution, C0 (mg L−1), and Ce (mg L−1) are the ion concentration in the influent solution and the ion concentration in the effluent solution, respectively. Also, V (L) is the solution volume, and m (g) is the resin mass.

After conducting the experiments, a 3 M sulfuric acid solution was used to regenerate the resins inside the column. 3 M Sulfuric acid solution was sent to the fixed bed column with a flow rate of 0.96 mL min−1, and samples were taken from the eluate solution in regular time intervals. The regeneration test was performed at ambient temperature (25 °C). The percentage of resin regeneration in the fixed bed column is calculated by Eq. (6)46.

where Ci is the ion concentration in the eluate solution (mg L−1), V is the volume of the acid passed through the fixed bed column (L), and mi is the amount of the adsorbed ion by the resins (mg).

To investigate and understand the ion exchange behavior of Ce(III) in a real medium, a simulated solution with an acidity of 0.6 M and initial concentrations of 50 mg L−1 of Ce(III), 300 mg L−1 of Th(IV), and 1500 mg L−1 Fe(II) was prepared. It should be noted that the concentrations used to make the simulated solution were those of a Choghart (a mine in Yazd province, Iran) ore leach liquor. Examining the ion exchange process of Ce(III) from the simulated solution was done similarly to examining the ion exchange process of Ce(III) from the aqueous solution.

Results and discussion

Investigating of response surface method and statistical analysis

The experimental design was carried out using the CCD approach to investigate the ion exchange process of Ce(III). The experimental design data and results are listed in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that the maximum percentage of ion exchange was achieved with a condition of 0.16 g resin dosage, 35 °C temperature, and sulfuric acid concentration of 0.2 M (Run 1). Of course, the highest value of ion exchange capacity occurred under the conditions of 0.02 g resin dosage, 35 °C temperature, and sulfuric acid concentration of 0.6 M (Run 6). Also, Runs 8 to 13 show that the results obtained from repeating the tests were close and favorable.

All experiments were repeated at least three times, and the standard error (SE) of the experimental data was determined. In general, the SE for all data ranged from 1 to 3%.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the data obtained from the experimental design method. The analysis data are presented in Table 5.

In the analysis of variance, if the P-value is less than 0.05, the independent variable will be statistically significant, and high F-values indicate the significance of the model47,48,49,50,51,52. As observed in Table 5, the P-value is less than 0.0001, and the F-value of the model equals 87.84, which indicates that the model is valid. According to the P-value, which is the criterion that determines the significance of the coefficients of the model, the optimal equation (model) provided by the software is placed in Eq. (7). The statistics of the response surface method (RSM) and the value of the Determination coefficient in Table 6 indicate that the model fits well.

The value of the Determination coefficient shows that the fitting is good and that the model provided by the software is efficient for predicting the ion exchange rate of Ce(III) from the aqueous solution. The correlation between the actual values of Ce(III) exchange (%) and its values predicted by the model is shown in Fig. 2.

It can be observed that the data predicted by the model are in agreement with the actual data, perfectly. Three-dimensional response surface plots drawn by the software show the simultaneous effect of two variables on the response while other variables are held constant35,53. The three-dimensional graphs of the effect of acid concentration and temperature, the effect of acid concentration and resin dosage, as well as the effect of temperature and resin dosage on the percentage of Ce(III) ion exchange, are shown in Figs. 3, 4 and 5, respectively.

As can be observed in Fig. 3, the ion exchange of Ce(III) is strongly dependent on the change in the acid concentration value (acidity of the solution). Due to the endothermic nature of the process, the ion exchange of Ce(III) increased with increasing temperature, and this trend was better observed at higher acid concentrations. In general, temperature changes compared to acid concentration changes have had much less effect on Ce(III) ion exchange. In such a way that with the increase in acid concentration, the amount of Ce(III) ion exchange decreased strongly (with a relatively steep slope). Also, according to the model prediction, Ce(III) ion exchange will be complete at acid concentrations lower than 0.25 M and temperatures higher than 45 °C.

Figure 4 shows that the ion exchange of Ce(III) increases with a decrease in acid concentration and an increase in resin dosage. Because with increasing resin dosage, the number of active sites (ion exchange functional groups) increases. Also, with the reduction of acid concentration, the competition between Ce3+ and H+ cations in the solution to create a chemical bond with the functional groups of the resin decreases. Of course, acid concentration changes have a greater effect on Ce(III) ion exchange than do resin dosage changes. According to the model prediction, Ce(III) ion exchange does not occur in acid concentrations higher than 0.85 M and resin dosages less than 0.09 g.

It can also be observed in Fig. 5 that Ce(III) ion exchange increases with increasing temperature and increasing resin dosage. Due to the endothermic nature of the process, the ion exchange of Ce(III) has increased with increasing temperature, and this trend is better seen in higher dosages of resin. In general, changes in resin dosage have a greater effect on Ce(III) ion exchange than temperature changes.

Analysis of variance showed that the prediction of the model corresponded well with the data within the defined range. However, it is necessary to check the model’s validity using new experimental conditions. For this purpose, the acid concentration, temperature, and resin dosage were randomly selected, and the test was performed according to the conditions listed in Table 7. Then, the actual results obtained were compared with the results predicted by the model. The error percentage was calculated using Eq. (8)45. In this study, the model validation results were as follows: the predicted were close to the experimental data, but smaller than those in both cases. A more detailed examination of this issue requires further experiments.

Xexp and Xpred are the experimental and predicted data by the model, respectively.

Kinetic study of ion exchange

The study of kinetic models in the adsorption processes is crucial for understanding adsorption behaviors, evaluating the adsorbent performance, and investigating the mass transfer mechanisms54. Kinetic models indicate the time required for the adsorption process to reach equilibrium, allowing for better planning in industrial applications where time efficiency is critical55.

The effect of contact time on Ce(III) ion exchange was studied by performing the process at different contact times of 5 to 360 min. The diagram of this review is presented in Fig. 6. As can be observed, with the increase in contact time, the percentage of Ce(III) ion exchange has also increased; then, the functional groups of the resins were saturated, and the ion exchange process reached equilibrium and remained constant.

In this study, the equilibrium capacity (qe) was equal to 10.34 mg g−1. After the experiments, kinetic models were used to fit the experimental data. The results are presented in Table 8. The pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and intraparticle diffusion kinetic models are expressed by Eqs. (9)56,57, (10)57,58, and (11)59, respectively.

where qe (mg g−1) is the equilibrium adsorption capacity, and qt (mg g−1) is the adsorption capacity at time t. k1 (min−1) is the pseudo-first-order rate constant, and k2 (g mg−1 min−1) is the pseudo-second-order rate constant. Also, the kid (mg g−1 min−0.5) is the rate constant of intraparticle diffusion. Moreover, the thickness of the boundary layer can be obtained from the value of c.

The pseudo-second-order model fits the experimental data very well. According to the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, it is assumed that chemical sorption may be the rate-limiting step through sharing or exchange between the adsorbed ions and adsorbent58. The diagram of the pseudo-second-order kinetic model can be observed in Fig. 7.

Cao et al.18 studied the effect of contact time on the adsorption of Ce(III) by PAMHA resin under conditions of pH = 3, temperature 45 °C, and initial concentration 1401.16 mg L−1. The results showed that Ce(III) adsorption reached equilibrium in 6 h, and the pseudo-second-order model had the best fit among the kinetic models (R2 = 0.9902).

Study of isotherm models

The study of Isotherm models plays an important role in understanding and predicting the adsorption processes for pollutant removal. The isotherm models describe the interaction mechanisms between the adsorbents and adsorbates at equilibrium, providing insights into the adsorption capacity and characteristics of the adsorbents60.

The ion exchange process was performed using various initial concentrations of Ce(III) in the range of 10 mg L−1 to 500 mg L−1. The results of the experiments conducted to study the effect of the initial concentration of Ce(III) on ion exchange are presented in Fig. 8. From this study, it can be concluded that with an increase in the initial concentration, the ion exchange of Ce(III) decreased, but the amount of ion exchange capacity increased. With an increase in the initial concentration, the functional groups of the resins become saturated over time and are no longer able to exchange Ce3+ cations with the solution. For this reason, the ion exchange of Ce(III) decreased.

After the experiments, the experimental data were modeled using Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm models expressed by Eqs. (12)61,62, (13)63,64, and (14)65, respectively.

where qe (mg g−1−1) and qm (mg g−1) are the equilibrium adsorption capacity and maximum capacity of monolayer adsorption, respectively. KL (L mg−1) is the Langmuir isotherm constant. KF ((mg g−1) (L mg−1)1/n) represents Freundlich’s constant, and n represents the intensity of adsorption. Also, KT (L g−1) and bT are the constants of Tamkin’s isotherm, which express the maximum bond energy and heat of adsorption, respectively. B (J mol−1) is the heat of adsorption constant. R is the global gas constant equal to 8.314 J mol−1 K−1 and T (K) is Kelvin’s absolute temperature.

The obtained results are presented in Table 9. The Langmuir model had the best fit with the equilibrium data. The Langmuir model represents homogeneous and monolayered adsorption. Thus, if an adsorbed molecule enters a site, no further adsorption occurs66. On the other hand, the Freundlich model also had a favorable fit. Moreover, \(1>1/n\) it indicates favorable and normal adsorption65. The probable reason for this is the Non-uniform nature of the surface sites that participate in the uptake of ions17,67. The diagram of Langmuir’s isotherm model can be observed in Fig. 9.

These tests were performed with 0.6 M sulfuric acid solution and actually at pH = 0. In the past, studies at higher pH values have been performed. For example, Felipe et al.68 investigated the adsorption isotherms of REEs from acidic mine drainage waters at pHs 1.4, 2.4, and 3.4 and temperature 25 °C with different resins. Dowex 50W-X8 resin was also used in the adsorption isotherm study, and the highest Ce(III) adsorption capacity at pH = 1.4 was 23.67 mg g−1.

Study of thermodynamic parameters

Investigating the thermodynamics of the adsorption process is crucial for understanding the energy changes and stability of adsorbate-adsorbent interactions69. The thermodynamic parameters of Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG°), enthalpy changes (ΔH°), and entropy changes (ΔS°) are essential for understanding ion exchange behavior, which can be calculated using Eqs. (15)70,71, (16)72, and (17)73.

where KC is the equilibrium constant, R is the universal gas constant equal to 8.314 J mol−1 K−1 and T (K) is Kelvin’s absolute temperature.

The equilibrium constant (KC) can be obtained from the Langmuir isotherm constant (KL). However, it should be noted that the KL is a parameter with the unit L mg−1, while KC is a dimensionless parameter and has no unit. Therefore, KL must be made unitless, which can be done with Eq. (18)74.

where MW (g mol−1) is the molecular weight (which is equal to 18 for H2O), and the factor 55.5 is the number of moles of pure water per liter. Ignoring minor discrepancies, the numbers 55.5 and 18 can be used in thermodynamic calculations of aqueous solutions.

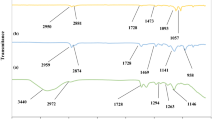

Ce(III) ion exchange process was carried out at 288, 308, and 328 K temperatures. For this purpose, using the conditions mentioned in Section "Study of isotherm models" (Study of isotherm models), the adsorption isotherms at the temperatures of 288 and 328 K were also studied. The KL values at these temperatures were equal to 0.00425 L mg−1 and 0.00827 L mg−1, respectively. To investigate the thermodynamics of Ce(III) ion exchange, the diagram of Ln KC changes was drawn in terms of the inverse of the absolute temperature (1/T), which can be observed in Fig. 10. Also, the data obtained from this study are presented in Table 10.

The adsorption process is endothermic, as indicated by the positive value of enthalpy changes70. Also, the positive value of entropy changes indicates the presence of disorder at the interface between the adsorbent and the solution, which indicates an increase in the adsorption of ions in a random manner72,73,75. In addition, the adsorption process is spontaneous, as indicated by the negative values of Gibbs free energy changes70,75.

Caiping17 investigated the thermodynamics of Ce(III) adsorption process at pH = 6.5 and temperatures of 288, 308, and 328 K using 15 mg of D151 resin. The values of ΔH° and ΔS° were 7.07 kJ mol−1 and 91.34 J mol−1 K−1, respectively, and negative values of ΔG° (− 19.24, − 20.15, and − 21.06 kJ mol−1) indicated spontaneous and endothermic adsorption.

The used solution had a pH of zero, whereas the pH in Caiping’s study was 6.5. The pH of the medium significantly influences the deprotonation of a resin’s functional groups76. As pH decreases, the deprotonation ability of the resins diminishes, which in turn reduces their ion exchange capability. At pH = 0, Dowex 50W-X8 resin is fully protonated. For the adsorption of Ce3+ this resin releases more protons from its surface, leading to an increase in entropy for the forward reaction. This accounts for the larger ΔS value observed in our work. In contrast, D151 resin is only partially protonated at pH = 6.5. Naturally, deprotonation for this resin resulted in less disorder in that system, yielding a smaller ΔS value. Given that a decrease in pH increases ΔS, an increase in temperature leads to a greater ΔG value (Eq. 16). Hence, the ΔG values in our study were higher than those in Caiping’s study, indicating the superior performance of Dowex 50W-X8 resin.

Study of ion exchange in a fixed bed column

The ion exchange process of Ce(III) from an aqueous solution was performed in a fixed-bed column. The breakthrough curve diagram of this process can be observed in Fig. 11, and the results are presented in Table 11.

Figure 11 shows that the breakthrough curve has a gentle slope, and the Ce(III) ion exchange process has reached equilibrium in a long time, indicating the resin’s desirable performance in the ion exchange of Ce(III) in a continuous system. This is due to the low initial concentration of Ce(III) in the influent solution and the high resin dosage (5.25 g). The initial concentration of Ce(III) and the acidity of the influent solution for the ion exchange process in the continuous system were selected using the batch system, and only the amount of resin was increased. However, the results show that the percentage of ion exchange in the continuous system (73.93%) was higher than that in the batch system (66.2%). On the other hand, the ion exchange capacity of the continuous system (9.32 mg g−1) has decreased compared to the batch system (10.34 mg g−1).

Monazam et al.77 investigated the removal of rare earth elements Ce3+, Yb3+, and Sm3+ from aqueous solution using a continuous flow reactor. They used two types of Dowex 50W-X8 resin, H+ form and NH4+ form. The amount of resin was 0.10 g, the length of the reactor was 0.2 cm, the flow rate was equal to 8 mL min−1, and the initial concentration was 100 mg L−1 for each of the elements in separate solutions (solution was RO water, pH = 6 ~ 6.5). Their investigation showed that the adsorption capacity of Ce(III) on H+ form resin was equal to 191 mg g−1 and on NH4+ form resin was equal to 197 mg g−1.

By comparing the thermodynamic results of our paper with those of Monazam’s paper, we can see that the pH of the solution used by us is zero, while the pH of the comparative paper is 6 ~ 6.5. Also, in our paper, the flow rate and initial concentration are lower; on the other hand, the amount of resin in the bed is higher. Hence, the equilibrium capacity value of our work is lower.

Kinetic study of ion exchange in the Continuous System

In the study of dynamic columns, the breakthrough curve of the ion exchange process can be analyzed using different kinetic models. The most famous are the Thomas, Bohart-Adams, and Yoon-Nelson models, which are expressed by Eqs. (19)78, (20)79, and (21)80, respectively. The Bohart-Adams model hypothesizes that the adsorption rate is controlled by the external mass transfer79. For the breakthrough curves relative concentration region up to 50%, Bohart-Adams and Yoon-Nelson models are trustworthy (\({C}_{t}/{C}_{0}<0.5\))79,80. The Thomas model is the most common in the study of column dynamics, and it follows the pseudo-second-order kinetic model and the Langmuir isothermal model78,79,80,81.

where q0 (mg g−1) is adsorbent capacity, x (g) is resin mass, KTh (L mg−1 min−1) is Thomas rate constant, υ (mL min−1) is flow rate, Z (cm) is height of bed, KAB (L mg−1 min−1) is Bohart-Adams rate constant, N0 (mg L−1) is adsorption capacity per unit of adsorbent volume, U0 (cm min−1) is linear flow rate, KYN (min−1) is Yoon-Nelson constant and τ (min) is The time required to reach 50% is progress.

The breakthrough curve diagram was fitted using Thomas, Bohart-Adams, and Yoon-Nelson kinetic models. Also, the data obtained from this study are reported in Table 11. The results show that the kinetic model of Thomas has the highest value of determination coefficient (R2) and the ion exchange data calculated by this model are very close to the experimental data. The Thomas model diagram is shown in Fig. 12.

Caiping17 investigated the adsorption process of Ce(III) in a continuous system with a flow rate of 0.27 mL min−1 under conditions of pH = 6.5, amount of resin 150 mg, and initial concentration of Ce(III) 0.20 mg mL−1. The maximum adsorption capacity in the fixed bed column was equal to 321 mg g−1, the breakthrough curve diagram fit well with the Thomas model (R2 = 0.976), and the adsorption capacity in the Thomas model was equal to 315 mg g−1.

By comparing the kinetic results of our paper with those of Caiping’s paper, we can see that the pH of the solution used by us is zero, while the pH of the comparative paper is 6.5. Also, the amount of resin in the bed is higher. Hence, the equilibrium capacity value of our work is lower.

Study of resin regeneration in a fixed bed column

Resin regeneration is the process of removing metal ions from loaded ion exchange resins. This step is essential for recovering valuable metals and regenerating resin for further use. The efficiency of resin regeneration directly affects the overall effectiveness of the metal recovery process82. Various acids, including HCl, H2SO4, and HNO3, are effective for resin regeneration83.

The loaded Dowex 50W-X8 resins were regenerated using a 3 M sulfuric acid solution. 3 M sulfuric acid solution was introduced into the column at a flow rate of 0.96 mL min−1, and elution solution was sampled at regular intervals. The test was performed at ambient temperature (25 °C). The results of this investigation are presented in Fig. 13. The bed regeneration process was performed for 30 min, which resulted in 98.81% desorption of Ce(III). As can be observed in Fig. 13, the maximum amount of desorption occurred in 10 min, and the maximum concentration of Ce(III) in the eluate solution was equal to 2773 mg L−1.

Caiping17 performed the process of desorption of Ce(III) with 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 M solutions of hydrochloric acid. The 0.5 M solution caused 100% desorption of Ce(III).

Study of ion exchange in a simulated medium

Most of the wastewater solutions, pregnant leach solutions (PLS), and leach liquors in industries are acidic and contain various impurities (interfering elements in processing)84,85. Therefore, it is important to study simulated solutions for the optimization of ion exchange processes. The ion exchange process of Ce(III) from the simulated solution was investigated in a continuous system. Ion exchange during loading is initiated due to the affinity between the resin and the ions. This process is influenced by the charge and ionic radius of the ions and the chemical structure of the resin86. The diagram of the breakthrough curves for the ions Ce(III), Th(IV), and Fe(II) are shown in Fig. 14. The data obtained from this study are presented in Table 12.

Diagram of breakthrough curve of Ce(III), Th(IV) and Fe(II) in fixed-bed column from simulated solution. (Flow rate 0.96 mL min−1, height of column 6 cm, H2SO4 concentration 0.6 M, temperature 25 °C, initial Fe(II) concentration 1500 mg L−1, initial Th(IV) concentration 300 mg L−1, initial Ce(III) concentration 50 mg L−1).

As can be observed in Fig. 14, the breakthrough curve diagram for the Fe(II) has been completed in a short period, which is due to the high initial concentration of this ion in the influent solution. The breakthrough curve of Th(IV) also has a relatively steep slope. In general, it can be concluded that under the same operating conditions, with an increase in the initial concentration in the influent solution, the breakthrough curve will reach the saturation point faster87,88. Because increasing the initial concentration increases the length of the mass transfer zone89. However, by observing the results in Table 12 and the breakthrough curves, it can be concluded that the IX(%) of Ce(III) changed very little in the presence of competing ions (67.66%) compared to when competing ions were not present (73.93%). This indicates that the Dowex 50W-X8 resin has a higher selectivity for Ce(III). The reason for this is that Dowex 50W-X8 resin is a resin with a sulfonic acid functional group. Resins with a sulfonic acid functional group have a greater tendency to affinity metal cations with higher charges90,91. On the other hand, Th(IV) forms a ThSO42+ complex in sulfuric acid90,92. Because ThSO42+ ions have a lower charge than Ce(III), the resin has a higher affinity for Ce(III) than for ThSO42+. However, Fe(II) retains its form in sulfuric acid and at pH = 093. It is worth noting that, for cations with the same charge, the affinity of strong acidic cationic resins toward the cation with a larger atomic radius is higher. Hence, the selectivity of cations by the resin and their IX(%) are as follows: Fe2+ < ThSO42+ < Ce3+. Thus, the adsorption of Ce(III) by resin is conducted to an acceptable extent even in the presence of Th(IV) and Fe(II) ions.

However, due to the competition between Ce(III) ions with Th(IV) and Fe(II) ions, also because of the higher initial concentration of Fe(II) and Th(IV) ions than Ce(III) ions, the active functional groups of resins with larger amounts of Fe(II) and Th(IV) ions saturated. This point can be observed by comparing the ion exchange capacity of Ce(III), Th(IV), and Fe(II) ions in Table 12. In general, the presence of competing ions such as Th(IV) and Fe(II) reduces the ion exchange capacity of Ce(III). This point is evident, as expected, when comparing the diagram of the ion exchange breakthrough curves of Ce(III) in Figs. 11 and 14.

Conclusions

In this research, firstly, the effect of the process parameters was investigated in a batch system. The experimental design by the surface response method showed; that reducing the acid concentration, and increasing the resin dosage and temperature will increase the ion exchange of Ce(III). The Ce(III) ion exchange process reached equilibrium within 6 h which equilibrium capacity (qe) was equal to 10.34 mg g−1. The kinetics of the process were most consistent with the pseudo-second-order model. Also, the process of Ce(III) ion exchange was carried out at initial concentrations of 10 mg L−1 to 500 mg L−1. The equilibrium data had the best fit with the Langmuir isotherm model. Investigation of thermodynamics at 288, 308, and 328 K temperatures revealed that the Ce(III) ion exchange process was spontaneous and endothermic. In the continuous system, ion exchange of Ce(III) from an aqueous solution in a fixed bed column of height 6 cm for up to 26 h. The breakthrough curve diagram was completed in 23 h, and the equilibrium capacity (qe) was equal to 9.32 mg g−1. The experimental data had the best fit with the kinetic model of Thomas. The low initial concentration of Ce(III) and high resin dosage were the causes of the prolonged process in the continuous system. The regeneration process of Dowex 50W-X8 resin was carried out in the fixed bed column with a 3 M sulfuric acid solution, which resulted in the desorption of 98.81% of Ce(III). Also, the performance of the resin in the ion exchange of Ce(III) from a simulated solution was investigated. The results showed that Dowex 50W-X8 resin exhibits acceptable performance even in the presence of competing ions Th(IV) and Fe(II), and the ion exchange rate of Ce(III) was 66.67%.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(B\) :

-

Heat of adsorption constant (J mol−1)

- \({b}_{T}\) :

-

Temkin isotherm constant is related to the heat of adsorption

- \(c\) :

-

Thickness of the boundary layer in the intra-particle kinetic model

- \({C}_{0}\) :

-

Initial concentration of adsorbate (mg L−1)

- \({C}_{i}\) :

-

Ion concentration in the eluate solution (mg L−1)

- \({C}_{e}\) :

-

Equilibrium concentration of adsorbate (mg L−1)

- \({C}_{t}\) :

-

Concentration of adsorbate at time t (mg L−1)

- \(h\) :

-

Height of bed (cm)

- \(IX\) :

-

Ion exchange

- \({K}_{AB}\) :

-

Constant of Bohart-Adams kinetic model (L mg−1 min−1)

- \({K}_{C}\) :

-

Equilibrium constant

- \({K}_{F}\) :

-

Freundlich isotherm constant ((mg g−1) (L mg−1)1/n)

- \({K}_{L}\) :

-

Langmuir isotherm constant (L mg−1)

- \({K}_{T}\) :

-

Temkin isotherm constant (L g−1)

- \({K}_{Th}\) :

-

Constant of Thomas kinetic model (L mg−1 min−1)

- \({K}_{YN}\) :

-

Constant of Yoon-Nelson kinetic model (min−1)

- \({k}_{1}\) :

-

Rate constant of pseudo-first-order kinetic model (min−1)

- \({k}_{2}\) :

-

Rate constant of pseudo-second-order kinetic model (g mg−1 min−1)

- \({k}_{id}\) :

-

Rate constant of intra-particle diffusion kinetic model (mg g−1 min−0.5)

- \(MTZ\) :

-

Mass transfer zone (cm)

- \({M}_{W}\) :

-

Molecular weight (g mol−1)

- \(m\) :

-

Mass of resin (g)

- \({m}_{i}\) :

-

Amount of the adsorbed ion by the resins (mg)

- \(N\) :

-

Adsorption capacity per unit of adsorbent volume (mg L−1)

- \({N}_{0}\) :

-

Adsorption capacity per unit of adsorbent volume in Bohart-Adams model (mg L−1)

- \(n\) :

-

Freundlich intensity constant

- \(Q\) :

-

Flow rate (mL min−1)

- \({q}_{b}\) :

-

Adsorption capacity at break time (mg g−1)

- \({q}_{e}\) :

-

Adsorption capacity at equilibrium (mg g−1)

- \({q}_{m}\) :

-

Maximum adsorption capacity in Langmuir isotherm model (mg g−1)

- \({q}_{s}\) :

-

Adsorption capacity at saturation time (mg g−1)

- \({q}_{t}\) :

-

Adsorption capacity at time t (mg g−1)

- \({q}_{0}\) :

-

Adsorption capacity in Thomas kinetic model (mg g−1)

- \(R\) :

-

Global gas constant equal to (J mol−1 K−1)

- \({R}^{2}\) :

-

Determination coefficient

- \(T\) :

-

Temperature (K)

- \(t\) :

-

Time (min)

- \({t}_{b}\) :

-

Time of break (min)

- \({t}_{s}\) :

-

Time of saturation (min)

- \(V\) :

-

Volume of solution (L)

- \({U}_{0}\) :

-

Linear flow rate (mL cm−1)

- \(x\) :

-

Mass of adsorbent (g)

- \(Z\) :

-

Depth of bed (cm)

- \(\upsilon\) :

-

Flow rate (mL min−1)

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

Relative error

- \(\tau\) :

-

Time required for 50% adsorbate breakthrough (min)

- \(\Delta G^\circ\) :

-

Gibbs free energy changes (kJ mol−1)

- \(\Delta H^\circ\) :

-

Enthalpy changes (kJ mol−1)

- \(\Delta S^\circ\) :

-

Entropy changes (J mol−1 K−1)

References

Fu, B. et al. A review of rare earth elements and yttrium in coal ash: Content, modes of occurrences, combustion behavior, and extraction methods. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 88, 100954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2021.100954 (2022).

Kajjumba, G. W. & Marti, E. J. A review of the application of cerium and lanthanum in phosphorus removal during wastewater treatment: Characteristics, mechanism, and recovery. Chemosphere 309, 136462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136462 (2022).

Zhang, J., Zhao, B. & Schreiner, B. Separation hydrometallurgy of rare earth elements Vol. 449 (Springer, 2016).

Milani, S. & Zahakifar, F. Stoichiometry and thermodynamics of cerium (IV) solvent extraction from sulfuric acid solutions by CYANEX 301. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 39, 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43153-022-00242-6 (2022).

Milani, S., Zahakifar, F. & Faryadi, M. Reaction stoichiometry and mechanism of tetravalent cerium liquid-liquid extraction in the Ce (IV)-H2SO4-Cyanex 302-kerosene system. Bulgarian Chem. Commun. https://doi.org/10.34049/bcc.54.4.5431 (2022).

Allahkarami, E. & Rezai, B. Removal of cerium from different aqueous solutions using different adsorbents: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 124, 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2019.03.002 (2019).

Ghaly, M., Youssef, M. & Borai, E. Efficient separation of cerium from rare earth elements and major impurities using low cost manganese ferrites from highly acidic solutions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 114588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114588 (2024).

Li, Z., Zhu, Y. & Yao, J. A comprehensive review on treatment and recovery of rare earth elements from wastewater: Current knowledge and future perspectives. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12(6), 114348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114348 (2024).

El Ouardi, Y. et al. The recent progress of ion exchange for the separation of rare earths from secondary resources–A review. Hydrometallurgy 218, 106047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2023.106047 (2023).

Opare, E. O., Struhs, E. & Mirkouei, A. A comparative state-of-technology review and future directions for rare earth element separation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 143, 110917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.110917 (2021).

Hermassi, M., Granados, M., Valderrama, C., Ayora, C. & Cortina, J. L. Recovery of rare earth elements from acidic mine waters by integration of a selective chelating ion-exchanger and a solvent impregnated resin. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2021.105906 (2021).

Kaim, V., Rintala, J. & He, C. Selective recovery of rare earth elements from e-waste via ionic liquid extraction: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 306, 122699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2022.122699 (2023).

Roa, A., López, J. & Cortina, J. L. Recovery of rare earth elements from acidic mine waters: A circular treatment scheme utilizing selective precipitation and ion exchange. Sep. Purif. Technol. 338, 126525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.126525 (2024).

Luqman, M. Ion exchange technology I: Theory and materials Vol. 1 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Sharifian, S. & Wang, N.-H.L. Resin-based approaches for selective extraction and purification of rare earth elements: A comprehensive review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12(2), 112402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.112402 (2024).

Bringas, A., Bringas, E., Ibañez, R. & San-Román, M.-F. Fixed-bed columns mathematical modeling for selective nickel and copper recovery from industrial spent acids by chelating resins. Sep. Purif. Technol. 313, 123457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2023.123457 (2023).

Caiping, Y. Adsorption and desorption properties of D151 resin for Ce (III). J. Rare Earths 28, 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0721(10)60324-9 (2010).

Cao, X., Zhou, C., Wang, S. & Man, R. Adsorption properties for La (III), Ce (III), and Y (III) with Poly (6-acryloylamino-hexyl hydroxamic acid) resin. Polymers 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13010003 (2020).

Miller, D. D., Siriwardane, R. & Mcintyre, D. Anion structural effects on interaction of rare earth element ions with Dowex 50W X8 cation exchange resin. J. Rare Earths 36, 879–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jre.2018.03.006 (2018).

Ghazala, R. Recovery of rare earth elements from uranium concentrate by using cation exchange resin. Isotope Radiat. Res. 47, 219–230 (2015).

Chan, M., Doan, H. & Dang-Vu, T. An investigation of lanthanum recovery from an aqueous solution by adsorption (ion exchange). Inorganics 12, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics12090255 (2024).

Masry, B., Abu Elgoud, E. & Rizk, S. Modeling and equilibrium studies on the recovery of praseodymium (III), dysprosium (III) and yttrium (III) using acidic cation exchange resin. BMC Chem. 16, 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-022-00830-0 (2022).

Silva de Moura, P. A. & Grande, C. Purification of Ytterbium Using a Cationic Resin. Available at SSRN 5066452, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5066452.

García, A. C., Latifi, M., Amini, A. & Chaouki, J. Separation of radioactive elements from rare earth element-bearing minerals. Metals 10, 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/met10111524 (2020).

Patel, K. S. et al. Occurrence of uranium, thorium and rare earth elements in the environment: A review. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1058053. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.1058053 (2023).

Cheremisina, O., Sergeev, V., Fedorov, A., Alferova, D. & Lukyantseva, E. Study of iron stripping from DEHPA solutions during the process of rare earth metals extraction from phosphoric acid. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 8, 1591–1595 (2019).

Yu, S., Ao, X., Liang, L., Mao, X. & Guo, Y. Recovery of rare earth elements from sedimentary rare earth ore via sulfuric acid roasting and water leaching. J. Rare Earths https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jre.2024.06.006 (2024).

Battsengel, A. et al. Recovery of light and heavy rare earth elements from apatite ore using sulphuric acid leaching, solvent extraction and precipitation. Hydrometallurgy 179, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2018.05.024 (2018).

Thomas, B. S. et al. Extraction and separation of rare earth elements from coal and coal fly ash: A review on fundamental understanding and on-going engineering advancements. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12(3), 112769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.112769 (2024).

Mokoena, K., Mokhahlane, L. & Clarke, S. Effects of acid concentration on the recovery of rare earth elements from coal fly ash. Int. J. Coal Geol. 259, 104037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2022.104037 (2022).

Gras, M., Papaiconomou, N., Chainet, E., Tedjar, F. & Billard, I. Separation of cerium (III) from lanthanum (III), neodymium (III) and praseodymium (III) by oxidation and liquid-liquid extraction using ionic liquids. Sep. Purif. Technol. 178, 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2017.01.035 (2017).

Han, K. N., Kellar, J. J., Cross, W. M. & Safarzadeh, S. Opportunities and challenges for treating rare-earth elements. Geosyst. Eng. 17, 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/12269328.2014.958618 (2014).

Asadollahzadeh, M., Torkaman, R. & Torab-Mostaedi, M. Extraction and separation of rare earth elements by adsorption approaches: Current status and future trends. Sep. Purif. Rev. 50, 417–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/15422119.2020.1792930 (2021).

Jyothi, R. K. et al. Review of rare earth elements recovery from secondary resources for clean energy technologies: Grand opportunities to create wealth from waste. J. Clean. Prod. 267, 122048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122048 (2020).

Yarahmadi, A., Khani, M. H., Nasiri Zarandi, M., Amini, Y. & Yadollahi, A. Ce (III) and La (III) ions adsorption using Amberlite XAD-7 resin impregnated with DEHPA extractant: Response surface methodology, isotherm and kinetic study. Sci. Rep. 13, 9959. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37136-7 (2023).

Pap, S. et al. Lanthanum and cerium functionalised forestry waste biochar for phosphate removal: Mechanisms and real-world applications. Chem. Eng. J. 494, 152848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.152848 (2024).

Taheri, M., Khajenoori, M., Shiri-Yekta, Z. & Zahakifar, F. Investigation of effective parameters in the removal of heavy metal from aqueous solution by biosorption method. Mater. Chem. Mech. 1, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.22034/mcm.2023.2.5 (2023).

Elgoud, E. A., Ismail, Z., El-Nadi, Y., Abdelwahab, S. & Aly, H. Column dynamic studies for lanthanum (III) and neodymium (III) sorption from concentrated phosphoric acid by strongly acidic cation exchange resin (SQS-6). Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2021.2016727 (2022).

Kubra, K. T. et al. Sustainable detection and capturing of cerium (III) using ligand embedded solid-state conjugate adsorbent. J. Mol. Liq. 338, 116667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116667 (2021).

Hu, Q., Xie, Y. & Zhang, Z. Modification of breakthrough models in a continuous-flow fixed-bed column: Mathematical characteristics of breakthrough curves and rate profiles. Sep. Purif. Technol. 238, 116399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2019.116399 (2020).

Patel, H. Fixed-bed column adsorption study: A comprehensive review. Appl. Water Sci. 9, 45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-019-0927-7 (2019).

Apiratikul, R. Application of analytical solution of advection-dispersion-reaction model to predict the breakthrough curve and mass transfer zone for the biosorption of heavy metal ion in a fixed bed column. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 137, 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2020.02.018 (2020).

Samanth, A., Vinayagam, R., Varadavenkatesan, T. & Selvaraj, R. Fixed bed column adsorption systems to remove 2, 4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid herbicide from aqueous solutions using magnetic activated carbon. Environ. Res. 261, 119696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.119696 (2024).

Ting, C. et al. Response surface methodology for optimizing adsorption performance of gel-type weak acid resin for Eu (III). Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China 25, 4207–4215. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1003-6326(15)64071-7 (2015).

Chen, C. et al. Dynamic adsorption models and artificial neural network prediction of mercury adsorption by a dendrimer-grafted polyacrylonitrile fiber in fixed-bed column. J. Clean. Prod. 310, 127511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127511 (2021).

Virtanen, E. J. et al. Recovery of rare earth elements from mining wastewater with aminomethylphosphonic acid functionalized 3D-printed filters. Sep. Purif. Technol. 353, 128599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.128599 (2025).

Jung, K.-W., Hwang, M.-J., Park, D.-S. & Ahn, K.-H. Comprehensive reuse of drinking water treatment residuals in coagulation and adsorption processes. J. Environ. Manage. 181, 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.06.041 (2016).

Altaş, Y. et al. An experimental design approach for the separation of thorium from rare earth elements. Hydrometallurgy 178, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2018.04.009 (2018).

Ji, B. & Zhang, W. Rare earth elements (REEs) recovery and porous silica preparation from kaolinite. Powder Technol. 391, 522–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2021.06.028 (2021).

Zahakifar, F., Keshtkar, A., Souderjani, E. Z. & Moosavian, M. Use of response surface methodology for optimization of thorium (IV) removal from aqueous solutions by electrodeionization (EDI). Prog. Nucl. Energy 124, 103335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2020.103335 (2020).

Taheri, M., Khajenoori, M., Shiri-Yekta, Z. & Zahakifar, F. Application of plantain leaves as a bio-adsorbent for biosorption of U (VI) ions from wastewater. Radiochim. Acta 111, 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1515/ract-2022-0109 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Preparation and optimization of the adsorbent for phosphorus removal using the response surface method. Magnetochemistry 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry10010005 (2024).

Chaudhary, H., Kohli, K. & Kumar, V. Nano-transfersomes as a novel carrier for transdermal delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 454, 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.07.031 (2013).

Wang, J. & Guo, X. Adsorption kinetic models: Physical meanings, applications, and solving methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 390, 122156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122156 (2020).

Patil, P., Jeppu, G., Girish, C. R. & Mohan, B. Development of a comprehensive analytical solution for modeling adsorption kinetics and equilibrium. Sep. Sci. Technol. 59, 373–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496395.2024.2319146 (2024).

Alamdarlo, F. V., Solookinejad, G., Zahakifar, F., Jalal, M. R. & Jabbari, M. Study of kinetic, thermodynamic, and isotherm of Sr adsorption from aqueous solutions on graphene oxide (GO) and (aminomethyl) phosphonic acid–graphene oxide (AMPA–GO). J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 329, 1033–1043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-021-07845-2 (2021).

Zahakifar, F. & Khanramaki, F. Continuous removal of thorium from aqueous solution using functionalized graphene oxide: Study of adsorption kinetics in batch system and fixed bed column. Sci. Rep. 14, 14888. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65709-7 (2024).

El-Aryan, Y. Kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamic modeling of light lanthanides (III): La (III) and Gd (III) using Mn–Ni nanoparticles. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 38, 255–267. https://doi.org/10.4314/bcse.v38i1.19 (2024).

Feng, L. et al. A study of rare earth elements enriched carbonisation material prepared from Dicranopteris pedata biomass grown in mining area. Sci. Rep. 15, 6486. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86067-y (2025).

Al-Ghouti, M. A. & Da’ana, D. A. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of adsorption isotherm models: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 393, 122383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122383 (2020).

Napol’skikh, J., Shoppert, A., Loginova, I., Kirillov, S. & Valeev, D. Selective recovery of scandium (Sc) from sulfate solution of bauxite residue leaching using Puromet MTS9580 ion-exchange sorption. Metals 14(2), 234. https://doi.org/10.14738/aivp.122.16738 (2024).

Zhao, G., Wu, X., Tan, X. & Wang, X. Sorption of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions: A review. Open Colloid Sci. J. 4, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.2174/1876530001104010019 (2010).

Bbumba, S., Karume, I., Nsamba, H. K., Kigozi, M. & Kato, M. An insight into isotherm models in physical characterization of adsorption studies. Eur. J. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.14738/aivp.122.16738 (2024).

Doram, A., Outokesh, M., Ahmadi, S. J. & Zahakifar, F. Synthesis of “(aminomethyl) phosphonic acid-functionalized graphene oxide”, and comparison of its adsorption properties for thorium (IV) ion, with plain graphene oxide. Radiochim. Acta 110, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1515/ract-2021-1090 (2022).

Dada, A. O., Olalekan, A. P., Olatunya, A. M. & Dada, O. J. I. J. C. Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin and Dubinin-Radushkevich isotherms studies of equilibrium sorption of Zn2+ unto phosphoric acid modified rice husk. IOSR J. Appl. Chem. 3(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.9790/5736-0313845 (2012).

Rajahmundry, G. K., Garlapati, C., Kumar, P. S., Alwi, R. S. & Vo, D.-V.N. Statistical analysis of adsorption isotherm models and its appropriate selection. Chemosphere 276, 130176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130176 (2021).

Tan, I., Ahmad, A. & Hameed, B. Enhancement of basic dye adsorption uptake from aqueous solutions using chemically modified oil palm shell activated carbon. Colloids Surf., A 318, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2007.12.018 (2008).

Felipe, E., Batista, K. & Ladeira, A. Recovery of rare earth elements from acid mine drainage by ion exchange. Environ. Technol. 42, 2721–2732. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593330.2020.1713219 (2021).

Saleh, T. A. Interface science and technology Vol. 34, 65–97 (Elsevier, 2022).

da Costa, T. B., da Silva, M. G. C. & Vieira, M. G. A. Recovery of rare-earth metals from aqueous solutions by bio/adsorption using non-conventional materials: A review with recent studies and promising approaches in column applications. J. Rare Earths 38, 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jre.2019.06.001 (2020).

Hamadneh, I., Al-Jundub, N. W., Al-Bshaish, A. A. & Al-Dujiali, A. H. Adsorption of lanthanum (III), samarium (III), europium (III) and gadolinium (III) on raw and modified diatomaceous earth: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic study. Desalin. Water Treat. 215, 119–135. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2021.26762 (2021).

Lima, E. C., Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A., Moreno-Piraján, J. C. & Anastopoulos, I. A critical review of the estimation of the thermodynamic parameters on adsorption equilibria. Wrong use of equilibrium constant in the Van’t Hoof equation for calculation of thermodynamic parameters of adsorption. J. Mol. Liquids 273, 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2018.10.048 (2019).

Botelho Junior, A. B., Pinheiro, E. F., Espinosa, D. C. R., Tenorio, J. A. S. & Baltazar, M. D. P. G. Adsorption of lanthanum and cerium on chelating ion exchange resins: Kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Separat. Sci. Technol. 57(1), 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496395.2021.1884720 (2022).

Tran, H. N., You, S.-J., Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. & Chao, H.-P. Mistakes and inconsistencies regarding adsorption of contaminants from aqueous solutions: A critical review. Water Res. 120, 88–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2017.04.014 (2017).

Zhou, X., Yu, X., Maimaitiniyazi, R., Zhang, X. & Qu, Q. Discussion on the thermodynamic calculation and adsorption spontaneity re Ofudje et al. (2023). Heliyon 10, (2024).

Jasim, A. Q. & Ajjam, S. K. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater using ion exchange resin in a batch process with kinetic isotherm. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 49, 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajce.2024.04.002 (2024).

Monazam, E., Siriwardane, R., Miller, D. & McIntyre, D. Rate analysis of sorption of Ce3+, Sm3+, and Yb3+ ions from aqueous solution using Dowex 50W–X8 as a sorbent in a continuous flow reactor. J. Rare Earths 36, 648–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jre.2017.10.010 (2018).

Basu, A., Ali, S. S., Hossain, S. S. & Asif, M. A review of the dynamic mathematical modeling of heavy metal removal with the biosorption process. Processes 10, 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10061154 (2022).

Juela, D. M. Comments on “dynamic adsorption of sulfamethoxazole from aqueous solution by lignite activated coke”. Materials 14, 848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14040848 (2021).

Chu, K. H. Breakthrough curve analysis by simplistic models of fixed bed adsorption: In defense of the century-old Bohart-Adams model. Chem. Eng. J. 380, 122513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.122513 (2020).

Han, R., Wang, Y., Zou, W., Wang, Y. & Shi, J. Comparison of linear and nonlinear analysis in estimating the Thomas model parameters for methylene blue adsorption onto natural zeolite in fixed-bed column. J. Hazard. Mater. 145, 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.12.027 (2007).

Silva, R. A., Hawboldt, K. & Zhang, Y. Application of resins with functional groups in the separation of metal ions/species–a review. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 39, 395–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/08827508.2018.1459619 (2018).

Al-Asheh, S. & Aidan, A. A comprehensive method of ion exchange resins regeneration and its optimization for water treatment. Promising Techniques Wastewater Treatment Water Quality Assessment, 163–176, https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.93429 (2020).

Izatt, R. M., Izatt, S. R., Bruening, R. L., Izatt, N. E. & Moyer, B. A. Challenges to achievement of metal sustainability in our high-tech society. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 2451–2475. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CS60440C (2014).

Judge, W. D. & Azimi, G. Recent progress in impurity removal during rare earth element processing: A review. Hydrometallurgy 196, 105435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2020.105435 (2020).

José, L. B. & Ladeira, A. C. Q. Recovery and separation of rare earth elements from an acid mine drainage-like solution using a strong acid resin. J. Water Process Eng. 41, 102052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2021.102052 (2021).

Verduzco-Navarro, I. P., Rios-Donato, N., Jasso-Gastinel, C. F., Martinez-Gomez, A. D. J. & Mendizábal, E. Removal of Cu (II) by fixed-bed columns using Alg-Ch and Alg-ChS hydrogel beads: effect of operating conditions on the mass transfer zone. Polymers 12, 2345. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12102345 (2020).

Fila, D. & Kołodyńska, D. Fixed-bed column adsorption studies: Comparison of alginate-based adsorbents for La (III) ions recovery. Materials 16, 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16031058 (2023).

Zaki, A. & Ahmad, M. Batch and chromatographic removal of Nd3+ and Dy3+ ions from waste solutions using humic acid. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 4, 4310–4322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2016.09.033 (2016).

Ang, K. L., Li, D. & Nikoloski, A. N. The effectiveness of ion exchange resins in separating uranium and thorium from rare earth elements in acidic aqueous sulfate media. Part 1. Anionic and cationic resins. Hydrometallurgy 174, 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2017.10.011 (2017).

Kołodyńska, D. & Hubicki, Z. Investigation of sorption and separation of lanthanides on the ion exchangers of various types. Ion Exchange Technol. 6, 101–154. https://doi.org/10.5772/50857 (2012).

Kim, E. & Osseo-Asare, K. Aqueous stability of thorium and rare earth metals in monazite hydrometallurgy: Eh–pH diagrams for the systems Th–, Ce–, La–, Nd–(PO4)–(SO4)–H2O at 25 C. Hydrometallurgy 113, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2011.12.007 (2012).

Alguacil, F. J. The removal of toxic metals from liquid effluents by ion exchange resins. Part XV: iron (II)/H+/Lewatit TP208. Rev. Metal. 57(1), e190–e190. https://doi.org/10.3989/revmetalm.190 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. I. wrote the main manuscript. M. Kh., F. Z., and A. Gh. edited and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ildarabadi, A., Khajenoori, M., Zahakifar, F. et al. The study of cerium separation from aqueous solutions using Dowex 50WX8 resin via ion exchange in batch and continuous mode. Sci Rep 15, 26586 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11640-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11640-4