Abstract

Accurately integrating pore geometry analysis into velocity predictions remains a challenge in heterogeneous formations, such as Brazilian Pre-Salt carbonates, where complex pore structures significantly impact petrophysical properties. This study aims to evaluate the petrophysical properties of carbonates from the Santos basin, offshore Brazil. We employed an advanced methodology using machine learning to reconstruct the S-wave velocity (\(V_S\)) log from P-wave velocity (\(V_P\)), density (\(\rho _b\)), and neutron porosity (\(\phi _N\)) logs. Among the models tested, the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) architecture demonstrated the highest accuracy, achieving the lowest error values. Additionally, visual computing was employed to extract geometric characteristics related to porosity from mCT images to apply Kuster-Toksöz (K-T) and Self-Consistent (S-C) theoretical effective models to estimate elastic velocities. Our results showed that the K-T model tends to overestimate velocity values, while the S-C model yields values closer to the experimental ones. A significant relationship was observed between pore aspect ratios and the velocity values, emphasizing the impact of the pore geometry on the velocity predictions. Furthermore, it was noted that analyzing two-dimensional images can introduce variations in these measurements. This integrated approach not only enhances the understanding of reservoir behavior, but also introduces a novel application of computer vision techniques in geophysical studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Characterizing porosity in carbonate rocks is a significant challenge for reservoir management, owing to both their high heterogeneity and the complexity of their pore systems in this type of rock. In Brazilian pre-salt reservoirs, specifically those in the Barra Velha Formation, this complexity is even more pronounced due to their unique diagenetic and depositional processes. Estimating elastic properties, such as compressional (\(V_P\)) and shear (\(V_S\)) wave velocities, is essential for seismic modeling, petrophysical analysis, and reservoir simulation. However, this task is limited by the uncertainty associated with pore geometry and its impact on rock elastic moduli. This study aims to address the need for more effective methods that integrate pore geometry information and its impact on elastic velocity estimation, thereby fulfilling an existing gap in the characterization of pre-salt carbonates.

A technique for quantitative evaluation of fracture and vuggy porosities in carbonate formations1 is based on a generalized resistivity model tailored for formations with double porosity, integrating both a homogeneous porous matrix and ellipsoidal inclusions to represent fractures or vugs. The model characterizes these structures through an anisotropy in electrical properties, with resistivity showing a nonlinear relationship with the porosity and saturation of each pore system. Statistical analysis of core data from over 100 boreholes in Mexico’s South Zone indicated that Archie’s law with a cementation exponent of m=2 effectively describes the matrix formation factor for carbonate formations.

The calibration tool for estimating permeability in carbonate reservoirs using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) well logs has been improved with the introduction of new, more efficient methods in recent studies2. It focuses on characterizing the NMR response to carbonate matrix pore spaces and their connectivity to larger vugs and fractures. The research involved detailed analysis of core samples from various carbonate formations, spanning a wide range of permeability, mean \(T_2\) values, and porosity percentages. One interesting point is that the authors could not find a universal model for reproducing permeability across different carbonate formations due to reservoir-specific phenomena. Instead, the study suggests calibrating permeability estimates with laboratory measurements, relying on formation porosity measured with downhole NMR tools. A modified form of the Kozeny equation was used for the best estimates, requiring calibration from laboratory measurements specific to the reservoir.

An empirical methodology for estimating porosity and permeability in carbonates using sonic logging was developed in a recent paper3. This method, previously successful in sandstones, was tested on oolitic carbonate reservoirs. The methodology centers on estimating porosity from measured S-wave slowness, an approach notably insensitive to fluid effects and thus minimizing the influence of invaded zones on the results. The study showed that S-porosity closely resembles NMR effective porosity, more so than NMR total porosity, indicating that mud and its bound water acoustically behave as part of the matrix. The new deviation log approach also qualitatively describes porosity types and shows a complex relationship with permeability.

With the advancements in the accuracy and efficiency of machine learning techniques, a notable growth in research using ML tools for porosity estimation from image data and well-log data is evident in the literature. This integration of machine learning could represent a major leap forward in our understanding of subsurface properties, opening new frontiers in exploration and resource management. Artificial intelligence (AI) techniques have been applied in an innovative way to determine porosity in carbonate reservoirs, an essential parameter in estimating oil reserves4. The study evaluates AI tools like artificial neural networks (ANNs), support vector machines (SVMs), and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFIS) to predict reservoir porosity from wireline log data. Over 1700 field measurements of porosity, alongside log data, were utilized for training and testing these AI models. The results demonstrated that ANNs and ANFIS are highly effective in estimating reservoir porosity, showing a high correlation coefficient (R) and low average absolute percentage error (AAPE). Results showed accurately predicted reservoir porosity with a correlation coefficient of 0.98 and an AAPE of less than 8%.

In the context of image analysis, tomography techniques have been used to assess the porosity of a wide range of porous media, including reservoir rocks. Benchtop microtomography equipment typically achieves resolutions of up to 1 micrometer, capable of capturing a wide range of porosity4,5,6,7. From the obtained image slices, numerical models are generally employed to extract petrophysical measurements and elastic parameters, including the bulk modulus (\(\kappa\)), shear modulus (\(\mu\)), which are then used to calculate the compressional (P) and shear (S) wave velocities8, as a function of rock density (\(\rho\))9,10,11,12,13,14.

In contrast, the Kuster-Toksöz model takes a more detailed approach by considering pore geometry (characterized by the aspect ratio) in the calculation of effective moduli. This model can provide more accurate predictions for materials in which pore shape significantly influences the overall mechanical properties. In carbonate rocks, for example, pores can have various shapes (such as penny-shaped or needle-shaped), and these geometries can significantly affect the rock’s mechanical behavior15,16,17,18.

In this study, we generated synthetic curves of effective moduli by varying the aspect ratios with models such as Kuster-Toksöz and Self-Consistent effective media. This approach allowed for a more refined estimation of porosity in heterogeneous carbonate formations. Effective moduli derived from these models are also utilized to identify the predominant types of porosity in these complex structures. Furthermore, the findings are validated through the application of micro-computed tomography (mCT) imaging techniques. The methodology presents a novel and efficient approach to characterizing carbonate reservoirs by leveraging the synergy between well-log data analysis, advanced modeling techniques, and imaging methods. This integration has the potential to enable more accurate predictions and support better-informed decision-making in the exploration and exploitation of carbonate reservoirs.

Geological setting

The carbonate formation process is generally complex, as they are sedimentary rocks produced by chemical and biological processes rather than a single or dual mineral. They are mainly composed of calcite, dolomite, or aragonite, with other subordinate minerals such as anhydrite, gypsum, siderite, quartz, clay minerals, pyrite, oxides, and sulfates19,20,21,22. In relation to porosity property, holocene carbonate rocks have porosities ranging from 40 to 70%, with higher values in micritic limestones23. This high porosity is often associated with carbonates formed in deep water, which have inter- and intraparticle porosities23.

The Santos Basin comprises an area of more than 350 thousand square kilometers, with approximately 60% submerged at water ranging from 400 to 1500 meters below sea level. It stretches from Cabo Frio (in the state of Rio de Janeiro) to Florianópolis (in the state of Santa Catarina), occupying the southeastern sector of the Brazilian continental margin. The Santos Basin is the largest Brazilian oil basin productor according to National Oil and Gas Agency (ANP). A significant part of this production comes from very thick carbonate reservoirs (up to 400-500 m) belong to the Barra Velha Formation24,25(see Fig. 1).

Map of the Santos Basin, offshore Brazil, illustrating the distribution of pre-salt oil fields. The yellow polygon indicates the giant Lula/Tupi oil field (formerly Tupi), which encompasses the study area of the Iracema field. The dashed line shows the approximate shortest distance between the Iracema field and the coastline (308.17 km). Field polygons obtained from the National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP) GeoMaps Portal (https://geomaps.anp.gov.br/). Base map imagery provided by Google Maps. Map created using QGIS 3 (https://qgis.org/).

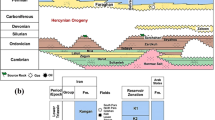

This basin has undergone a tectonostratigraphic evolution characterized by the fragmentation of the supercontinent Gondwana, giving rise to three distinct stratigraphic mega-sequences26,27. In agreement with previous studies,25 it succintly describes the evolutionary stages of these mega-sequences formed during the rift, post-rift, and drift phases, respectively. According to the current tectonostratigraphic development model for the Santos Basin, the first mega-sequence is related to the rift phase and the last to the drift phase, respectively.

As reported28, the rift supersequence comprises continental siliciclastics, talc-stevensite ooids with intercalated lacustrine coquinas and shales from the Piçarras and Itapema formations. The post-rift phase is composed of lacustrine carbonates and shales from the Barra Velha Formation, followed by evaporite deposits of anhydrite, halite, and minor soluble salts such as carnallite, sylvite, and tachyhydrite, comprising the Ariri Formation.

The Barra Velha Formation comprises a carbonate succession characterized by intercalations between ‘in situ’ facies (such as stromatolites, spherulites, mg-mud laminites, and microbial laminites) and their redeposited facies(comprising grainstones, rudstones, and packstones), deposited during the Eoaptian (early Cretaceous) age25. Furthermore, dolostones, marls (clay mudstones), silexite (chert), and shales are commonly interlayered with the main previously cited facies. Recent studies have identified that the facies of the Barra Velha Formation in the Santos Basin, are predominantly composed of three main mineralogical components: calcite spherulites, calcite bushes, and mud, which includes micrite and magnesian muds28. They have highlighted that the carbonates within these formations contain silica bodies, which can be several centimeters thick and exhibit various textures and geometries across different carbonate facies. This observation suggests the involvement of syngenetic, diagenetic, and hydrothermal processes in the formation of these silica bodies. The same authors have also pointed out that mineralogical and textural alterations associated with these processes can directly influence the porosity and permeability characteristics of the carbonate reservoirs within these formations.

The carbonates within the Barra Velha Formation have been categorized based on their porosity characteristics29, which include enlarged intergranular porosity, fenestral porosity, intercrystalline and vugular porosity, alveolar porosity, lamellar-to-vugular porosity resulting from dissolution, moldic porosity, vuggy porosity, and microfractures within chert. This classification aligns with the scheme illustrated in Fig. 230.

The Iracema Oil Field (IOF) is located in the Santos Basin, 250 km off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, northwest of the Tupi oil field (see Fig. 1). As reported31, the Iracema field area is formed by carbonates with shrubby texture, reworked carbonates, and low-energy carbonates featuring vugs and fractures, all belonging to the Barra Velha Formation. The microbial reservoirs of the Barra Velha Formation in this field (Brazilian Pre-salt), have porosities ranging between 9% and 12 % and an average permeability of 100 mD with variations observed between different wells and fields within the Pre-Salt Province32.

Methodology

Figure 3 outlines the integrated workflow used in this study for determining the pore aspect ratio and elastic properties of rock samples. The process begins with input data from well logs and core samples, which were analyzed through laboratory measurements and mCT images. In parallel, laboratory measurements, including density, P-wave, and S-wave velocities, are obtained from the core samples. This information feeds into the estimation of mineral composition and elastic moduli, namely bulk modulus (K) and shear modulus (\(\upmu\)), which are crucial for understanding the mechanical behavior of the rocks. The S-wave velocity is predicted using MLP, a type of neural network, assisting in further analysis steps.

The workflow proceeds with image segmentation techniques applied to the mCT images to estimate pore aspect ratios, a critical characteristic that influences fluid flow and the mechanical properties of the rock. This segmentation may be performed using advanced image analysis or machine learning models, such as the U-Net model for precise delineation of pore spaces. The data obtained from image segmentation is then used alongside models such as the Self-Consistent and Kuster-Toksöz models, which are calibrated with core measurements to estimate the effective elastic moduli and velocities for each sample.

In the final stages, comparative analyses are performed to validate the workflow. The estimated pore aspect ratios derived from image segmentation are compared with those predicted by the effective models to ensure accuracy and consistency. Moreover, the laboratory-measured velocities are compared with those obtained from the effective models to validate predictions.

Samples and data acquisition

A total of 19 core samples, obtained from the National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP), were analyzed. At the Petrophysics and Rock Physics Laboratory – Om Prakash Verma at the Federal University of Pará, Brazil – measurements of porosity, permeability, and compressional and shear velocities (\(V_P\) and \(V_S\)) were carried out33. An example of ultrasonic travel time signatures used to convert to compressional (P) and shear (S) wave velocities is shown in Fig. 4, using a 1 MHz transducer for the P wave and a 500 KHz transducer for the S wave.

Laboratory-measured transit times of P- and S-waves, manually picked to determine compressional and shear wave velocities. (a) travel-time picking for the P-wave (1 MHz) and (b) travel-time picking for the S-wave (500 kHz). An example of manually calculating the arrival times of the P and S waves, in microseconds, in order to calculate the velocities in the samples, which were measured in the laboratory using transducers.

Additionally, at the Petroleum Science and Engineering Lab (LCPetro), Federal University of Pará (UFPA), Salinópolis Campus, Brazil, high-resolution mCT imaging was carried out to analyze the internal structure and properties of the samples34. Petrophysical and elastic logs from three wells supplied by the Iracema field were used for the well logs analysis. We measured the porosity using a \(N_2\) gas porosimeter, and as the samples have a perfect cylindrical shape, we calculated the density simply by the ratio of the mass of the sample to the volume of the cylinder with the dimensions of each sample.

Machine and deep learning techniques: regression estimation

Since most of the methodology depends on machine or deep learning, it is imperative to follow a systematic procedure to ensure an effective analysis. Data acquisition, which involves selecting the input and output characteristics, and pre-processing, including normalization and despiking, constitute the primary stages of this procedure. Feature extraction entails identifying and extracting significant attributes from the data. Model selection entails selecting an appropriate machine learning or deep learning –an MLP model in this instance. Model training, validation, and evaluation assess the trained model’s generalization ability.

This neural network was implemented using the TensorFlow35 framework and the Keras library36. Bayesian optimization of the KerasTuner package37 was used to optimize the MLP parameters. Unlike more traditional optimization methods, such as RandomSearch, Bayesian optimization selects hyperparameters randomly only during initial iterations and subsequently refines the choices based on prior error values. Missing log information, such as the shear wave velocity log (\(V_S\)), can be predicted using machine learning regression techniques38,39,40.

Two of the four wells were analyzed as they provided information on the geological composition, which was essential for the study. However, these wells lacked shear wave transit time data, which was required to generate the \(V_S\) log for the model application. To address this, a file from one of the remaining wells containing the shear wave transit time log was used to train an MLP model. The trained model was then applied to the wells of interest to predict the \(V_S\) log, using \(V_P\), \(\rho\) (density), and \(\phi _N\) (neutronic porosity) as inputs for the Iracema well-logs.

After obtaining the predicted \(V_S\) values for the well logs using the MLP, we compared them to the laboratory measurements of \(V_S\) obtained from the core samples. Furthermore, we compared other petrophysical properties, such as \(V_P\), \(\rho\), and \(\phi\), between the well logs and the core samples to verify the precision of the well logs. Any discrepancies found in the comparison were taken into account during the analysis of the results.

To ensure the feasibility of using a more robust estimator instead of traditional ones, we also applied multiple linear regression (MLR) and subsequently calculated the coefficient of determination (\(R^2\)) and the mean squared error (MSE). These metrics are crucial for assessing the performance of our predictive model. The coefficient of determination \((R^2)\) is given by Eq. (1) and is defined as:

where RSS is the residual sum of squares, TSS is the total sum of squares, \(y_i\) represents the actual values from the well log, \(\hat{y}_i\) represents the predicted values from the regression models, and \(\bar{y}\) is the mean of the actual values. The \(R^2\) value ranges from 0 to 1, where a value closer to 1 indicates a higher degree of correlation between predicted and actual values, signifying that the model explains a large proportion of the variance in the data. In this context, a high \(R^2\) value would indicate that the MLP model provides a reliable prediction of \(V_S\) based on the well logs.

The other metric used was the mean squared error (MSE), which is defined by Eq. (2) as:

where n is the number of observations, \(y_i\) represents the actual values from the core samples, and \(\hat{y}_i\) represents the predicted values from the well logs. The MSE is defined as the average of the squared differences between the actual and predicted values.

A lower MSE indicates that the predicted values are closer to the actual values, which signifies a better-performing model. In our analysis, a low MSE would confirm that the MLP model accurately predicts \(V_S\) with minimal error. By evaluating these metrics, we can quantitatively assess the performance of the MLP predictive model and ensure that it provides accurate and reliable estimates of \(V_S\) and other petrophysical properties.

Figure 5 (a) shows some log inputs that are used for \(V_S\) estimation. The first track represents P-wave velocity measurements (\(V_P\)), providing insight into lithology and fluid content. The second track displays bulk density (RHOB) measurements, aiding in lithology identification and porosity estimation. The third track illustrates neutron porosity (NPHI) measurements, which are crucial for evaluating the reservoir fluid content and porosity distribution. Lastly, the fourth track presents S-wave velocity values (\(V_S\)) derived from a multilinear regression model that incorporates \(V_P\), RHOB, and NPHI. The despiking process on the curves was carried out using a moving average, and if the modulus of the difference between a point on the moving average and a point on the profile is above a certain tolerance, that point is considered a spike and replaced by the value of the corresponding moving average. The data used for the prediction of \(V_S\) was split into 30% for validation and testing, and 70% for training. In addition to Bayesian optimization, we used a callback known as “Early Stopping,” which evaluates the error by following the validation curve. When the validation error stops increasing, the neural network starts overfitting, and training stops automatically, recovering the weights corresponding to the epoch with the least validation error. Another technique to avoid overfitting was dropout, which consists of turning off a certain percentage of different neurons for each epoch during training.

The image illustrates the process of predicting S-wave velocity (\(V_S\)) using well log data from the Iracema Field, based on machine learning and multiple linear regression models. (a) input and output logs are used in the modeling process. The P-wave velocity (\(V_P\)), bulk density (RHOB), and neutron porosity (NPHI) logs were used as inputs after despiking (i.e., the removal of outliers). The \(V_S\) log is shown as the reference output, and (b) compares real \(V_S\) values with those predicted by two methods: Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and Multiple Linear Regression (MLR).

Methodology for mCT scanning and image processing

Micro-computed tomography (mCT) scans of the rock samples were performed using a V|Tomex|S system (GE Measurement & Control Solutions, Wunstorf, Germany). The parameters of the scans varied across the samples to optimize image quality and resolution based on their specific characteristics. The voltage ranged from 130 to 160 kV, selected to ensure sufficient X-ray penetration and optimal imaging for rocks with varying densities. The current settings varied between 80 to 190 \(\mu\)A, adjusted to balance the contrast and noise levels in the images. The exposure time for the scans was set between 200 and 333 milliseconds. The number of images captured per scan ranged from 1,600 to 2,500.

The voxel resolution of the images ranged from 15 to 28 micrometers. After acquisition, 3D reconstructions of the scanned images were processed using Phoenix Data software. Beam hardening correction was applied to mitigate artifacts caused by non-linear X-ray attenuation, which can result in inaccurate density representation. For 3D visualization and further analysis of the rock samples’ internal structures, VG Studio Max v 3.3.2 software was utilized.

A multi-scan mode was employed to analyze several samples, including samples A and B, for which the imaging procedure was segmented for each individual sample. The 3D mCT images of plugs B (vertical) and A (lateral) from wells B4 and D1 are depicted in Fig. 13. Porosity is represented by the color transition from red to white, with denser regions appearing as white. Zones of high-density minerals, such as pyrite or calcite, are represented by blue regions.

2D Image-based estimation of pore aspect ratios

The procedure to estimate the pore aspect ratio was conducted using image processing functions in Python provided by scikit-image41. From a grayscale image \(I\), as input, to remove the border influence, the Gaussian smoothing operation can be represented mathematically as the convolution of the image \(I\) with a Gaussian kernel \(G_{\sigma }\), defined by Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively:

where \(G_{\sigma }\) is the two-dimensional Gaussian kernel with standard deviation \(\sigma\). The Gaussian kernel is defined as:

where \(x\) and \(y\) are the coordinates in the kernel, and \(\sigma\) is the standard deviation controlling the amount of smoothing. The convolution operation \(*\) is applied between the image \(I\) and the Gaussian kernel \(G_{\sigma }\), resulting in the smoothed image.

According to Eq. (5), the gradient of the smoothed image \(I\) with respect to the \(x\) and \(y\) directions can be computed using the Sobel operator,42 given as follows:

The edge image \(\text {edges}\) is then obtained by computing the magnitude of the gradient, is expressed by Eq. (6):

Apply a threshold to the edge image to highlight significant edges. Thresholding is a critical step in image processing to separate important features from background noise. In this step, each pixel value in the edge image \(\text {edges}\) is compared to a predefined threshold value. If the pixel value exceeds the threshold, it is considered part of an edge and assigned a value of 1 in the binary image \(\text {binary}\); otherwise, it is assigned a value of 0. Although there are algorithms that determine the threshold value automatically by applying an adaptive threshold (e.g., Otsu), we determined the threshold manually by visual inspection since automatic determination overestimated or underestimated the pore area. Mathematically, the binary image \(\text {binary}\) is computed as follows in Eq. (7):

where \((i, j)\) represents the coordinates of the pixel in the image.

Next, the measure.label function from scikit-image is utilized to label the connected components in the binary image. Each component is analyzed with measure.regionprops, which calculates various geometric properties, including the aspect ratio (\(\phi _{ar}\)) of each detected object, described by Eq. (8) as follows:

where \(a\) and \(b\) represent the lengths of the minor and major axes of the pore space, respectively. Here, \(\epsilon\) is set to \(1e^{-9}\) to avoid division by zero.

The final visualization includes the original image alongside the segmented image with labeled objects. In addition, the code calculates and displays the average aspect ratios of the detected objects, providing a summarized metric of the shapes of objects in the image. The second part of the algorithm provides an interactive interface to adjust the segmentation threshold and visualize the smaller and larger dimensions of the identified pores, marking their orientations with lines on the segmented images. This feature is particularly useful for analyzing porosity and other petrophysical characteristics.

To apply the effective media models to the mCT images, we used segmentation to extract geometric parameters from the pores to feed the models, which include the number of pores, aspect ratios, and areas, according to the methodology proposed by43. In the case of areas, as it is a quantity that relates the area of a pore to the total area of the image, it was not necessary to use a specific unit of measurement, as the volume fraction is dimensionless. With this information, we generated a histogram showing the distribution of the aspect ratio for each image. To relate the size of the pores to how they affect the overall average, we also calculated the weighted average to assess which pores, weighted by area, have the greatest influence on the sample’s aspect ratio. The porosity values obtained from the well data and measured in the laboratory are shown in Table 1.

Porous classification by rock physics model

We employed the Kuster-Toksöz and Self-Consistent models to categorize pore types based on their geometry. Given that the borehole data do not directly provide the necessary effective moduli (\(\mu\) and \(\kappa\)) for implementing these models, we derived estimations using the following equations. Firstly, for the shear modulus (\(\mu\)), we used Eq. (9):

Subsequently, for the bulk modulus (K), the estimation is given by Eq. (10):

These calculated moduli are essential for applying the chosen models in our classification of pore types based on geometric considerations.

We worked with samples from wellB4 and wellD1 and used different approaches to estimate the volume fraction of minerals in each sample. The wellD1 samples were analyzed by XRD; Their values are shown in Table 2, which was used to estimate the input moduli of the effective models for the minerals with their respective elastic moduli shown in Table 3. To estimate the volume fraction of the minerals in the wellB4 samples, we used information from the well survey report, which indicated that the samples were rich in calcite and dolomite. Based on this information, we estimated the density of the mineral in the sample and, based on this density, estimated the volume fraction of these two minerals, as shown in the following Eq. (11):

in which \(\rho _B\) corresponds to the density of the rock, \(\rho _m\) to the density of the matrix, \(\phi _N\) to the neutron porosity, and \(\rho _f\) to the density of the fluid. Considering that the matrix is made up of more than one mineral, we add a variable corresponding to the secondary mineral, where \(\rho _m\) is given from Eq. (12), as follows:

where \(\rho _2\) is the density of the secondary mineral, \(v_2\) the volume fraction of this component, and \(\rho _{1}\) the density of the main mineral. Substituting \(\rho _m\) from Eq. (12) into Eq. (11), we obtain Eq. (13):

Kuster-Toksöz effective theory

Kuster-Toksöz derived expressions for the velocities of P and S waves by using a long-wavelength first-order scattering theory15. A generalization of their expressions for the effective moduli \(K_{\textrm{KT}}^*\) and \(\mu _{\textrm{KT}}^*\) for a variety of inclusion shapes can be written according to Eqs. (14) to (16), proposed by15 and44, expressed as:

and,

where the summation is over the different inclusion types with volume concentration \(x_{i}\) and

The coefficients \(P^{\textrm{mi}}\) and \(Q^{\textrm{mi}}\) describe the effect of the inclusion of material \(\textrm{i}\) in a background medium \(\textrm{m}\). For example, a two-phase material with a single type of inclusion embedded within a background medium has a single term on the right-hand side. Inclusions with varying material properties or shapes require different terms in the summation. Each set of inclusions must be distributed randomly, and thus their effect is isotropic. These formulas are uncoupled and can be made explicit for easy evaluation.

Self-consistent approximation

The Self-Consistent approximation for two phases is given by Eqs. (17) and (18)45:

and,

where \(K_{SC}^{eff}\) is the bulk effective modulus and \(\mu _{SC}^{eff}\) is the shear effective modulus.

These models consider the presence of the matrix (m) and the inclusions (i).

Initially, the model is composed only of the matrix, and as the value of \(x_i\) (volume of inclusion) increases, the effective moduli decrease, since the elastic moduli of the fluid that compose the inclusions are lower than the elastic moduli of the mineral that composes the rock matrix. As in Kuster-Toksöz, the coefficients \(P^{mi}\) and \(Q^{mi}\) are geometric parameters that depend on the aspect ratio (\(\alpha\)), which in turn is related to the shape of the pore in relation to the length of its axes, as shown in Fig. 6.

Representative elementary volume analysis

Considering the heterogeneities and anisotropies in the analyzed samples, we valuate the representative elementary volume (REV) to identify the smallest volume that accurately represents the sample and ensures the macroscopic petrophysical properties remain statistically constant as the volume increases8. We used porosity analysis to determine REV. In the axial images, we generated a circle, and in the radial ones, a rectangle. We enlarged these shapes incrementally, and for each geometric shape size, there is an associated porosity, as shown in Figs. 16 and 17.

Results

Shear wave velocity prediction using MLP

The MLP regression model exhibited superior performance, as shown in Fig. 5 and is evidenced by the metrics: MSEs of 0.010939 and 0.012057, and \(R^2\) values of 0.86 and 0.83 for the MLP and Multiple Regression models, respectively. The best model obtained from Bayesian optimization contains two hidden layers with 32 and 288 neurons, respectively, and a 20% layer dropout. The activation function used for the hidden layers was ReLU, and the optimizer was RMSprop, with a learning rate of 0.01. After training the data, we applied the model to the Iracema wells of interest to predict \(V_S\). The predictions and the measurements obtained from the core samples are shown in Fig. 7. As we can see, the predicted values for \(V_S\) are very close to those measured in the laboratory for the core samples.

Well log data from Wells B4 and D1, highlighting the depth intervals used for estimating elastic properties. Well B4 (top): Logs of density, P-wave velocity (\(V_P\)), S-wave velocity (\(V_S\)), \(V_P/V_S\) ratio, and porosity (PHI). Well D1 (bottom): The same set of logs is shown for well D1. Red markers and green dots highlight selected depth intervals and data points used for calibration and validation of predictive models.

Estimation of elastic moduli and velocities

We generated the upper and lower limits of Hashin-Shtrikman and Voigt-Reuss, given by Eqs. (19) to (22), based on the volumetric fractions provided by the XRD analysis.We verified that the sample corresponding to a depth of 5072 m best fitted the well data for the depth interval corresponding to the part of the reservoir from which the cores were collected, as can be seen in the figures generated from the implementation of the models.

Based on the ratios of the volume fractions given by the XRD analysis in wellD1 and those calculated from the density for wellB4, we used these values as input for the Kuster-Toksöz (Eqs. 14 and 15) and self-consistent (Eqs. 17 and 18) effective media models. The curves were generated for different aspect ratio values and plotted together with the elastic moduli of the well data (obtained from \(V_P\) and \(V_S\) velocities), as well as the velocities obtained by applying the models to the mCT images, which are shown in Figs. 8, 9, 10 and 11. Figs. 8 to 11 show the Kuster-Toksöz and Self-Consistent porous media models applied to wells B4 and D1, focusing on the relationship between elastic properties (bulk and shear moduli) and seismic velocities (\(V_P\) and \(V_S\)) as a function of porosity.

Application of the Kuster-Toksöz model to well B4, showing the relationship between porosity and elastic properties. (a) Bulk modulus (left) and shear modulus (right) plotted against porosity. Theoretical bounds (Hashin-Shtrikman upper and lower) and effective medium curves for various pore aspect ratios are shown for comparison, and (b) compressional wave velocity (\(V_P\), left) and shear wave velocity (\(V_S\), right) as functions of porosity. Theoretical curves are again plotted for different aspect ratios. The distribution of the data illustrates the sensitivity of elastic velocities to porosity and pore geometry.

Application of the Kuster-Toksöz model to well D1, representing the relationship between porosity and elastic and seismic properties of the formation, based on well data and theoretical models. (a) The graphs, on the y-axis, show the bulk modulus (K) and shear modulus (\(\mu\)) as a function of porosity (v/v) and (b) the relationship between compressional wave velocities (\(V_P\)) and shear wave velocities (\(V_S\)) is also plotted as a function of porosity.

Application of the Self-Consistent model to well B4, demonstrating the relationship between porosity and elastic and seismic rock properties, from well data and theoretical simulations. (a) The graphs show the bulk modulus (K) on the left and the shear modulus (\(\mu\)) on the right as a function of porosity (v/v) and (b) the graphs on the left and right show, respectively, the compressional wave velocities (\(V_P\)) and shear wave velocities (\(V_S\)) as a function of porosity.

Application of the Self-Consistent model to well D1, demonstrating the relationship between porosity and elastic and seismic rock properties, from well data and theoretical simulations. (a) The graphs show the bulk modulus (K) on the left and the shear modulus (\(\mu\)) on the right as a function of porosity (v/v) and (b) the graphs on the left and right show, respectively, the compressional wave velocities (\(V_P\)) and shear wave velocities (\(V_S\)) as a function of porosity.

Both models incorporate different pore aspect ratios (from 0.01 to 0.5), representing extremely flattened pores (cracks) to more spheroidal pores. In both models, the Hashin-Shtrikman limits - upper (dotted blue line) and lower (dashed red line) - delimit the theoretical extremes of the elastic properties and the experimental data from most samples and logs lie between these limits. In terms of aspect ratios, the values obtained by applying the models directly to the geometric parameters provided by the segmentation showed higher values than those obtained by the models applied to the well data. Based on the velocity values shown in the Table 4, we can see that the velocities tend to increase as the frequency scale used for the wave measurements decreases. The results obtained by the models applied to the well images provide values and velocities well above those provided by smaller scales of observation.

The velocities calculated from the elastic moduli, derived from the effective models applied to the images, are considerably higher than the velocities measured in the laboratory and the velocities obtained from the well data, as can be seen in Fig. 12 (and Table 4).

Aspect ratio analysis from mCT image processing for samples from wells B4 and D1. Each row shows the original grayscale image (left), its corresponding binarized and segmented version (center), and the histogram of aspect ratio distribution (right). For B4, both axial and radial sections display similar distributions, with average aspect ratios around 0.48-0.56 and a standard deviation of 0.18. In D1, two axial subregions (middle and top) exhibit slightly lower averages (0.45-0.49) and standard deviations around 0.19-0.20. These results suggest that B4 has more elongated pore structures compared to D1. Dashed lines in the histograms represent mean values (magenta) and one standard deviation (green) from the mean.

Schematic representation of core sample extraction and orientation for mCT analysis. (a) Vertical plug-B extracted parallel to the vertical drilling direction, (b) core drilling and sampling process from a vertical well intersecting reservoir bedding, illustrating both vertical and lateral plug orientations, and (c) lateral plug-D extracted perpendicular to the vertical direction, with your respective spatial resolution. The X, Y, and Z coordinate axes indicate the spatial orientation of each plug in relation to bedding and well direction. Adapted from46.

The histograms shown in Figs. 14 and 15 originated from the aspect ratios derived from the synthetic curves applied to the well data. In this case, it can be seen that the aspect ratios calculated for the entire layer tend to have lower values than those obtained from the mCT images corresponding to specific depths. Additionally, it is also observed that the distributions may be bimodal in some cases, indicating that there is more than one type of predominant porous shape.

Aspect ratio distributions estimated from the self-consistent model for elastic moduli (K, \(\mu\)) and seismic velocities (\(V_P\), \(V_S\)) for wells B4 (top) and D1 (bottom). Histograms represent the relative frequency of aspect ratios that best fit the observed data for each property, while the red curves correspond to synthetic curves generated by the Kuster-Toksöz model. Note that well B4 exhibits a relatively symmetric distribution centered between 0.06 and 0.15 for most properties. In contrast, well D1 presents more asymmetric and peaked distributions, particularly for K and \(\mu\), suggesting a predominance of more oblate inclusions in this interval.

Aspect ratio distributions derived from the Self-Consistent model for wells B4 (top) and D1 (bottom), considering the elastic moduli (K, \(\mu\)) and seismic velocities (\(V_P\), \(V_S\)). Each histogram shows the density distribution of aspect ratios that best fit the rock physics modeling results for a given property, with the red lines representing synthetic curves generated by the Self-Consistent model. Well B4 exhibits narrower distributions skewed toward lower aspect ratios (0.05 to 0.2), indicating more oblate inclusions. In contrast, well D1 shows broader and more symmetric distributions, centered at higher aspect ratios (0.2 to 0.4), suggesting more equant pore geometries. These differences reflect distinct pore structure characteristics between the two wells.

The REV analysis, shown in Figs. 16 and 17, indicates that the direction of the slice taken from the three-dimensional image is predominant for estimating the porosity value, since the axial images show a better approximation of the porosity measured in the laboratory than the radial images. In the case of wellB4, we did not have access to the axial slices, which can directly affect the estimation of the models.

Porosity distribution and representative elementary volume (REV) analysis for sample B4 in both radial and axial orientations. The left images show binary segmented images with red and green contours indicating the regions of interest. The right image displays porosity as a function of sampling radius (in pixels). The red vertical line marks the selected REV threshold, while the green line indicates the maximum analysis radius. In the radial section, porosity increases gradually with radius, stabilizing near the REV. In the axial section, porosity shows a rapid initial rise followed by stabilization, suggesting a more homogeneous structure.

Porosity distribution and representative elementary volume (REV) analysis for sample D1 in radial sections (top and middle). The left, binary segmented images highlight pores in black, with red and green circles denoting the regions of interest for REV analysis. The right porosity plotted against radial distance (in pixels). The red vertical line represents the chosen REV threshold, and the green line marks the maximum analysis radius. The top section shows higher porosity variations before stabilization, while the middle section exhibits a more gradual porosity increase, suggesting textural heterogeneity along the core length.

Bearing in mind that during the transit time measurement carried out in the laboratory for the \(V_P\) and \(V_S\) measurements, we have to consider the wave’s resolution (i.e., that only pores that are at least 1/4 of the wavelength would theoretically affect wave propagation), we calculated what the minimum dimensions to determine which would be the macro and micro pores, as shown in Table 5. Although micropores are quantitatively more predominant than macropores, when we sum all areas related to each subgroup, we see that macropores have a larger area in all radial images, as can be seen in Table 6.

Discussion

In this section, we discuss the results of our study, focusing on the prediction of velocities based on a qualitative analysis of pore types, as well as a comparison of experimental velocities and velocities estimated from the effective medium models theories described in the Methodology section. Considering that we are working with two-dimensional mCT images, there is a limitation in classifying pores as oblate or prolate, since this concept is related to three-dimensional space. On this basis, the analysis of the models and the interpretations of the results obtained from the mCT images are contained within the domain of oblate pores, and this classification is made between approximately penny-shaped and perfectly spherical.

Interpretation of MLP performance and its implications

Prediction of the shear wave velocity (\(V_S\)) is a crucial aspect of our study. Due to the absence of shear wave transit time data in the well data used in our study, we had to reconstruct this log using other well data from the same field. To do this, we used machine learning to build the prediction model from this log. We present the findings related to the prediction of \(V_S\), analyzing data obtained from various samples and experimental setups. This involves a detailed examination of the accuracy and reliability of the predictions, as well as any notable trends or anomalies observed during the analysis. We specifically compare the results obtained from machine learning-based regression estimation using the MLP network. It is important to note that although other regression methods were tested, the MLP regression model demonstrated the best performance.

Frequency effects ans model applicability

The Kuster-Toksöz model shows better adherence to the experimental data from the wells, especially in the intermediate porosity ranges, indicating that this model handles isolated pores and heterogeneous shape distributions well. The Self-Consistent model, on the other hand, is more appropriate for geometries with high connectivity and homogeneity, and tends to underestimate the experimental values, especially for lower aspect ratios. The Kuster-Toksöz model demonstrated greater sensitivity to aspect ratio variation, capturing nuances of the petrophysical behavior observed in the data. In contrast, the Self-Consistent model tended to cluster predictions towards lower values of moduli and velocities, particularly at higher porosities, suggesting limitations in contexts of heterogeneous and non-interconnected porosity.

Bearing in mind that the frequency used for laboratory measurements is extremely high, this means that the wave suffers greater effects from the occurrence of vugs, fractures, and fissures compared to the well data measurements. It is important to note that the effective media models are fundamentally theoretical based on low frequency and do not take into account phenomena related to wave propagation in heterogeneous and anisotropic media, such as dispersion and attenuation. Therefore, because the high frequency used to measure the transit time in the laboratory is related to low-wavelength waves, the transit time tends to be longer because the wave is subject to attenuation phenomena caused by the diagenetic complexity of the samples.

The results reveal significant frequency-dependent effects on elastic property measurements in heterogeneous carbonate rocks, with ultrasonic laboratory measurements (1 MHz for P-waves and 500 kHz for S-waves) exhibiting consistently lower velocities compared to low-frequency field data, and this aligns with theoretical models (e.g.,47). These findings have important implications for the application of effective medium models in reservoir characterization. The Self-Consistent (S-C) model (Fig. 11) demonstrates superior performance in matching laboratory measurements because its formulation inherently accounts for pore-to-pore interactions that dominate at ultrasonic frequencies. In contrast, the Kuster-Toksöz (K-T) model, which assumes isolated pores, systematically overestimates velocities (Fig. 9) when applied to high-frequency laboratory data. This discrepancy highlights the critical importance of frequency considerations when interpreting elastic properties across different measurement scales.

Experimental limitations and data interpetation

An additional challenge encountered was the difficulty in obtaining S-wave transit time measurements in the laboratory because, depending on the sample being measured, the wave arrival time can be difficult to obtain if there are many cracks or vugs, which tend to greatly attenuate the displacement of the shear wave. In addition, the length of the samples also becomes a challenge for measuring transit time, especially for the wellD1 samples, which vary between 2.6 and 3.6 cm, while the wellB4 samples vary between 4.3 and 6.92 cm.

In some cases, when we calculated the velocities using Eqs. 9 and 10 from the elastic moduli calculated by the models (as can be seen in all the velocity figures), the velocities were overestimated. This may be because to calculate the velocities, it is also necessary to estimate the density of the sample based only on the XRD analysis and a single slice, which can be seen as one of the limitations of 2D analysis. This also points out that the curves plotted with the well data were generated with respect to the values of a single sample, which does not necessarily represent the entire depth interval. When we compare the results obtained by the Kuster-Toksöz and Self-Consistent models, we see that the former tends to provide higher moduli and, consequently, higher speeds. When the models are plotted with the well data, because they have higher moduli, the aspect ratio curves tend to rise, which means that the data’s aspect ratios are underestimated. For the case of wellD1, it is noticeable that the Kuster-Toksöz model provides high values for the moduli, so that when calculated using the mCT images, they fall outside the Hashin-Shtrikman bounds, as can be seen in Fig. 9.

Aspect ratio influence and modeling implications

Previous work has shown that porosity and aspect ratio are determining factors when it comes to quantifying wave attenuation; it was found that an increasing aspect ratio directly implies increasing porosity, causing the wave attenuation coefficient to increase47. In this study, we found that increasing the aspect ratio while keeping the volume of all pores fixed implies an increase in velocity, as seen in Fig. 18. This analysis allows us to infer that the aspect ratios calculated in two-dimensional images may be underestimated, since the velocity values associated with lower aspect ratios show velocities closer to those measured in the well and in the laboratory.

Results of the simulations for compressional (\(V_p\)) and shear (\(V_s\)) wave velocities as a function of pore aspect ratio for different samples and image orientations using two effective medium models, proposed by Kuster-Toksöz (top) and Self-Consistent (bottom), respectively. Each subplot shows the variation of wave velocities with aspect ratio for B4 radial (B4 rad), B4 axial (B4 ax), D1 radial middle (D1 rad middle), and D1 radial top (D1 rad top). Both models reflect increasing velocities with higher aspect ratios, highlighting differences in poroelastic response between samples and orientations.

Regarding the estimation of the pore aspect ratio, a previous work48, also studying pre-salt carbonates, estimated the aspect ratio intervals using the DEM combined with well data measurements, obtaining similar intervals to the present work. However, in that analysis, the models were created using purely synthetic mineral composition estimates, considering calcite and dolomite proportions that were not necessarily obtained from the physical properties of the samples. In this study, in addition to estimating aspect ratios using effective Kuster-Toksöz and Self-Consistent models in conjunction with well data, we also used another approach that obtains aspect ratios directly from mCT images.

Conclusions

This study successfully integrated rock physics modeling, machine learning, and computer vision techniques to analyze the elastic properties and pore geometry of Brazilian pre-salt carbonates from the Iracema field. The multilayer perceptron (MLP) neural network demonstrated superior performance in reconstructing shear wave velocity \((V_S)\) logs from P-wave velocity \((V_P)\), density \((\rho )\), and neutron porosity \((\phi _N)\) data, achieving high accuracy with low mean squared error (MSE) and strong correlation coefficients \((R^2)\). This approach addresses the common challenge of missing \((V_S)\) logs in well data, providing a reliable alternative for reservoir characterization.

The application of the Kuster-Toksöz (K-T) and Self-Consistent (S-C) effective medium models revealed significant insights into the influence of pore aspect ratios on elastic moduli and seismic velocities. The K-T model tended to overestimate velocities, while the S-C model provided closer approximations to experimental measurements, particularly in heterogeneous carbonate formations. These findings highlight the importance of pore geometry in velocity predictions, with lower aspect ratios (flattened pores) correlating with reduced elastic moduli and higher aspect ratios (spheroidal pores) leading to increased velocities.

Micro-computed tomography (mCT) imaging and computer vision techniques enabled the extraction of pore geometric parameters, facilitating the application of theoretical models to real-world samples. However, limitations arose from 2D image analysis, which may underestimate true 3D pore structures. The representative elementary volume (REV) analysis confirmed that axial slices provided more accurate porosity estimates than radial slices, emphasizing the need for 3D imaging in future studies to improve geometric characterization.

The study also demonstrated the impact of measurement scale on velocity estimations, with laboratory ultrasonic frequencies (1 MHz for \(V_P\) and 500 kHz for \(V_S\)) being more sensitive to microstructural heterogeneities compared to well-log data. This discrepancy underscores the necessity of integrating multi-scale measurements to account for frequency-dependent dispersion and attenuation effects in carbonate reservoirs.

The findings have direct implications for reservoir characterization, particularly in pre-salt carbonates where complex pore systems dominate. The combination of machine learning for log reconstruction and rock physics models for pore classification offers a robust workflow for improving seismic interpretation and petrophysical analysis. Future work should explore advanced 3D segmentation techniques and broader datasets to enhance model generalization across different carbonate facies.

This research advances the understanding of elastic property estimation in heterogeneous carbonates by bridging well-log analysis, laboratory measurements, and digital rock physics. The methodologies developed here provide a foundation for more accurate reservoir simulations and informed decision-making in hydrocarbon exploration and production. Further refinements in pore-scale modeling and machine learning applications will continue to enhance predictive capabilities in geophysical studies.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files in https://github.com/patrickquadros/article_iracema_field.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available on https://github.com/patrickquadros/article_iracema_field.

References

Kazatchenko, E. & Mousatov, A. Primary and secondary porosity estimation of carbonate formations using total porosity and the formation factor. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition?, SPE–77787 (SPE, 2002).

Mason, H. E., Smith, M. M. & Carroll, S. A. Calibration of nmr porosity to estimate permeability in carbonate reservoirs. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 87, 19–26 (2019).

Silva, F., Beneduzi, C. F., Nassau, G. F. & Rossi, T. Using sonic log to estimate porosity and permeability in carbonates. In 16th International Congress of the Brazilian Geophysical Society held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 19–22 (2019).

Elkatatny, S., Tariq, Z., Mahmoud, M. & Abdulraheem, A. New insights into porosity determination using artificial intelligence techniques for carbonate reservoirs. Petroleum 4, 408–418 (2018).

Vanorio, T. & Mavko, G. Laboratory measurements of the acoustic and transport properties of carbonate rocks and their link with the amount of microcrystalline matrix. Geophysics 76, E105–E115 (2011).

Lin, Q., Al-Khulaifi, Y., Blunt, M. J. & Bijeljic, B. Quantification of sub-resolution porosity in carbonate rocks by applying high-salinity contrast brine using x-ray microtomography differential imaging. Adv. Water Resour. 96, 306–322 (2016).

Stadtműller, M. & Jarzyna, J. A. Estimation of petrophysical parameters of carbonates based on well logs and laboratory measurements, a review. Energies 16, 4215 (2023).

Mavko, G., Mukerji, T. & Dvorkin, J 2020 The rock physics handbook (Cambridge university press, 2020).

Liu, H., Ma, C. & Zhu, C. X-ray micro ct based characterization of pore-throat network for marine carbonates from south china sea. Appl. Sci. 12, 2611 (2022).

Fusi, N. & Martinez-Martinez, J. Mercury porosimetry as a tool for improving quality of micro-ct images in low porosity carbonate rocks. Eng. Geol. 166, 272–282 (2013).

Esteves Ferreira, M. et al. Full scale, microscopically resolved tomographies of sandstone and carbonate rocks augmented by experimental porosity and permeability values. Sci. Data 10, 368 (2023).

Alqahtani, N., Mostaghimi, P. & Armstrong, R. A multi-resolution complex carbonates micro-ct dataset (mrccm). Retrieved March 13, 2021, from (2021).

Soares, J. A. & de Andrade, P. R. L. A model for permeablility of carbonate rocks based on pore connectivity and pore size. In 15th International Congress of the Brazilian Geophysical Society & EXPOGEF, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 31 July-3 August 2017, 977–981 (Brazilian Geophysical Society, 2017).

Menke, H. P., Gao, Y., Linden, S. & Andrew, M. G. Using nano-xrm and high-contrast imaging to inform micro-porosity permeability during stokes-brinkman single and two-phase flow simulations on micro-ct images. Front. Water. 4, 935035 (2022).

Kuster, G. T. & Toksöz, M. N. Velocity and attenuation of seismic waves in two-phase media: Part i. theoretical formulations. Geophysics 39, 587–606 (1974).

de Ceia, M. A., Misságia, R. M., Neto, I. L. & Archilha, N. Relationship between the consolidation parameter, porosity and aspect ratio in microporous carbonate rocks. J. Appl. Geophy. 122, 111–121 (2015).

Vorobiev, S. & Vorobyev, V. Petrophysical applications of the elastic moduli modeling: Secondary porosity, saturation and permeability evaluation in complex carbonates through the rock-physics techniques. In SPWLA Annual Logging Symposium, SPWLA–2015 (SPWLA, 2015).

Candikia, Y. N., Rosid, M. S. & Haidar, M. W. Comparative study between kuster-toksoz and differential effective medium method for determining pore type in carbonate reservoir. In AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 1862 (AIP Publishing, 2017).

Ahr, W. M. Geology of carbonate reservoirs: the identification, description and characterization of hydrocarbon reservoirs in carbonate rocks (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

Rubo, R. A., de Carvalho Carneiro, C., Michelon, M. F. & dos Santos Gioria, R. Digital petrography: Mineralogy and porosity identification using machine learning algorithms in petrographic thin section images. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 183, 106382 (2019).

Conti, I. M., de Castro, D. L., Bezerra, F. H. & Cazarin, C. L. Porosity estimation and geometric characterization of fractured and karstified carbonate rocks using gpr data in the salitre formation, brazil. Pure Appl. Geophys. 176, 1673–1689 (2019).

Stadtműller, M. Well logging interpretation methodology for carbonate formation fracture system properties determination. Acta Geophysica 67, 1933–1943 (2019).

Schlanger, S. O. & Douglas, R. G. The pelagic ooze-chalk-limestone transition and its implications for marine stratigraphy. Pelagic Sediments: on Land and under the Sea 117–148 (1975).

Bruhn, C. H. et al. Campos and santos basins: 40 years of reservoir characterization and management of shallow-to ultra-deep water, post-and pre-salt reservoirs-historical overview and future challenges. In Offshore Technology Conference Brasil, D011S006R001 (OTC, 2017).

Moreira, J. L. P. et al. bacia de santos. Boletim de Geociencias da PETROBRAS 15, 531–549 (2007).

Pereira, M. J. & Macedo, J. M. A bacia de santos: perspectivas de uma nova província petrolífera na plataforma continental sudeste brasileira. Boletim de Geociencias da PETROBRAS 4, 3–11 (1990).

Pereira, M. J. & Feijo, F. J. Santos basin; bacia de santos (1994).

Gomes, J., Bunevich, R., Tedeschi, L., Tucker, M. & Whitaker, F. Facies classification and patterns of lacustrine carbonate deposition of the barra velha formation, santos basin, brazilian pre-salt. Mar. Pet. Geol. 113, 104176 (2020).

De Carvalho, M. D. & Fernandes, F. L. Pre-salt depositional system: Sedimentology, diagenesis, and reservoir quality of the barra velha formation, as a result of the santos basin tectono-stratigraphic development. 121–154 (2021).

Choquette, P. W. & Pray, L. C. Geologic nomenclature and classification of porosity in sedimentary carbonates. AAPG bulletin 54, 207–250 (1970).

Rosa, M. B., Cavalcante, J. S. d. A., Miyakawa, T. M. & Freitas, L. C. S. d. The giant lula field: World’s largest oil production in ultra-deep water under a fast-track development. In Offshore technology conference, D011S012R001 (OTC, 2018).

Penna, R., Camargo, G., Johann, P. R. & Dias, R. Challenges in seismic imaging and reservoir characterization of presalt oilfields in offshore brazil. In Offshore Technology Conference, OTC–24173 (OTC, 2013).

de Figueiredo, J. J. S. et al. On the application of the eshelby-cheng effective model in a porous cracked medium with background anisotropy: An experimental approach. Geophysics 83, C209–C220 (2018).

dos Santos Lucas, C. R. et al. Carbonate acidizing - a review on influencing parameters of wormholes formation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 220, 111168 (2023).

Abadi, M. et al. TensorFlow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous systems. Software available from tensorflow.org. (2015).

Chollet, F. et al. Keras. https://keras.io (2015).

O’Malley, T. et al. Keras Tuner. https://github.com/keras-team/keras-tuner (2019).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, C., Ma, Q., Zhang, X. & Zhou, H. Automatic prediction of shear wave velocity using convolutional neural networks for different reservoirs in ordos basin. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 208, 109252 (2022).

Bagheripour, P., Gholami, A., Asoodeh, M. & Vaezzadeh-Asadi, M. Support vector regression based determination of shear wave velocity. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 125, 95–99 (2015).

Elkatatny, S., Tariq, Z., Mahmoud, M., Mohamed, I. & Abdulraheem, A. Development of new mathematical model for compressional and shear sonic times from wireline log data using artificial intelligence neural networks (white box). Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 43, 6375–6389 (2018).

Van der Walt, S. et al. scikit-image: image processing in python. PeerJ 2, e453 (2014).

Farber, R. (ed.). Chapter 12 - Application Focus on Live Streaming Video, 277–301 (Morgan Kaufmann, 2011).

da Rocha, H. O. et al. Unraveling key factors that influence and shape fluid flow dynamics in brazilian salt lagoon stromatolites: a case study in pre-salt analogues. Petroleum Sci. 22, 1080–1097 (2025).

Berryman, J. G. Dispersion of extensional waves in fluid-saturated porous cylinders at ultrasonic frequencies. J.Acoust. Soc. Am. 74, 1805–1812 (1983).

Berryman, J. Mixture theories for rock properties. https://doi.org/10.1029/RF003p0205 (1995).

Sun, H., Vega, S. & Tao, G. Analysis of heterogeneity and permeability anisotropy in carbonate rock samples using digital rock physics. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. (2018).

Wang, Z., Wang, R., Li, T., Qiu, H. & Wang, F. Pore-scale modeling of pore structure effects on p-wave scattering attenuation in dry rocks. PloS one 10, e0126941 (2015).

Fournier, F. et al. The equivalent pore aspect ratio as a tool for pore type prediction in carbonate reservoirs. AAPG Bulletin 102, 1343–1377. https://doi.org/10.1306/10181717058 (2018).

Hashin, Z. & Shtrikman, S. A variational approach to the theory of the effective magnetic permeability of multiphase materials. J. Appl. Phys. 33, 3125–3131 (1962).

Wu, T. T. The effect of inclusion shape on the elastic moduli of a two-phase material. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2, 1–8 (1966).

Berryman, J. G. Long-wavelength propagation in composite elastic media. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 68, 1809–1831 (1980).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and the Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) of Brazil. We also extend our gratitude to Petrec Company and the National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas, and Biofuels of Brazil (ANP) for providing the data used in this study. Additionally, we thank the Ohm Verma Laboratory (UFPA-Belém) and the Laboratory of Petroleum Science and Engineering (LCPETRO/UFPA-Campus Salinópolis) for conducting the core sample measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Patrick S. M. Quadros conceived the experiment, developed the methodology, conducted the investigation, wrote the original draft, and performed the validation. Patrick S. M. Quadros, Jose J. S. de Figueiredo, Vitor F. H. Serra, Luciana Brelaz, Cláudio R. dos S. Lucas, Pedro Tupã P. Aum, and Herson O. da Rocha contributed to the writing, review, and editing. Jose J. S. de Figueiredo supervised the project and conceived the exaperiments Luciana Brelaz, Cláudio R. dos S. Lucas, and Pedro Tupã P. Aum contributed to the investigation, validation, and methodology. Herson O. da Rocha contributed to the original draft and performed the validation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Quadros, P.S.M., Figueiredo, J.J.S.d., Serra, V.F.H. et al. Integrative rock physics and computer vision analysis of elastic properties and pore aspect ratios in Brazilian pre-salt carbonates. Sci Rep 15, 33467 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11646-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11646-y