Abstract

Salivary proline-rich proteins (PRPs) represent a common mechanism of defense against tannins in mammals. Few reports exist regarding the occurrence or PRPs with similar function in nematodes and none of these proteins or their coding genes have been functionally characterized so far. In Caenorhabditis elegans, two genes (clx-1 and T22D1.2) were strongly induced upon tannin treatment of the nematodes, both of them potentially encoding proline-rich proteins. Therefore, translation of these genes into proteins was confirmed and the expression pattern was investigated in more detail. Particularly T22D1.2 was found to be exclusively up-regulated in worms treated with test substances possessing astringent properties, especially tannins, whereas no expression was observed for any other stressor or in the untreated control group. Similar to mammalian PRPs, repetitive proline-rich sequences were identified in both of the corresponding proteins. A potential role in tannin defense was supported by an increased survival of tannin-treated worms when T22D1.2 was constitutively expressed under the vit-5 promoter. However, no differences were observed in the clx-1 and T22D1.2 knockout mutants in comparison to the wild type, respectively. Within the current study, evidence was provided for the existence of repetitive proline-rich proteins in the free-living nematode C. elegans, of which particularly T22D1.2 may be involved in tannin defense.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tannins comprise a group of secondary metabolites that is widespread across the plant kingdom. Structurally, proanthocyanidins (syn. condensed tannins) and hydrolyzable tannins (HT) form two major subclasses found in terrestrial plants1,2: Proanthocyanidins (PAC) consist of flavan-3-ol units that are mainly linked via C-4 to C-6 or C-8 of another monomeric unit1. Hydrolyzable tannins, on the other hand, are formed by gallic acid and its derivatives esterified with glucose or other polyols2. Despite their structural differences, both, PAC and HT share the property of binding to proteins leading to similar biological effects. While this activity is desired in medicinal applications of extracts from tannin-rich plants3, the intake of tannins by mammalian herbivores can affect nutrient availability due to interfering with digestive enzymes4. At higher doses or in susceptible animal species, it is associated with adverse effects, such as damage to the intestinal mucosa and epithelium as well as kidney or liver failure5,6.

Such detrimental activities can be circumvented either by avoiding tannin-rich plant species as feed or by counteracting their effects. Salivary proteins, and particularly proline-rich proteins (PRP), that bind tannins with high affinity represent one such countermeasure6,7,8. In line with a role as a mechanism of defense, mammals like browsers, feeding on a tannin-rich diet, generally tend to produce higher amounts of proline-rich proteins in the salivary glands compared to species consuming less tannins, e.g., grazers6,9,10. Similarly, PRPs are completely absent in Theropithecus gelada, a graminivorous baboon species, while omnivorous hamadryas baboons possess PRPs11. However, a high content of proline itself is not necessarily indicative of the affinity of a protein to bind tannins10. And likewise, herbivorous species lacking PRPs are found to secrete structurally distinct proteins with high affinity for tannins12. Compared to mammals, the effects of tannins are frequently much less pronounced in non-mammalian herbivores. In several insect species, neither toxic nor feeding deterrent effects were observed, whereas in some, pupal growth and survival of larvae and caterpillars were negatively affected by tannin consumption13,14. Similarly, condensed tannins had a negative impact on the occurrence and density of certain herbivore insects, but not for the majority of species15.

Regardless of their exposure and adaption to tannins, insects possess various protective mechanisms, foremost surfactants that prevent protein-precipitating activities of tannins in the midgut13,16. The secretion of the amino acid glycine into the digestive juice represents another mode of defense against protein denaturing plant secondary metabolites17. Further properties include the maintenance of a high midgut pH to inhibit tannin-protein binding as well as different antioxidative mechanisms. Additionally, the peritrophic envelope acts as a barrier protecting the midgut epithelium and preventing the absorption of tannins13.

Finally, plant pathogenic nematodes represent the third group of herbivores. Surprisingly, only few studies report on the role of tannins in nematode resistance, despite the substantial impact of plant parasitic nematodes in agriculture on the one hand, and the plethora of secondary metabolites produced in response to nematode infestation on the other18. One example is a banana cultivar with high levels of condensed tannins and a distinct tannin composition compared to other cultivars, which conferred resistance against the nematode Radopholus similis18,19. Phenolic compounds, including tannins, have also been associated with plant resistance towards the root lesion nematodes of the genus Pratylenchus20. Interestingly, a study focusing on the identification of effector genes in Pratylenchus penetrans revealed the presence of transcripts encoding proteins extremely rich in proline21,22. Also, glycine was highly abundant in the protein sequences predicted from the gene transcripts localized in the esophageal glands22. Particularly the predicted proline-rich proteins were hypothesized to act as a countermeasure against tannin-like deposits produced by the plant during P. penetrans infection21. Two genes (T22D1.2 and clx-1) also predicted to code for repetitive proline-rich proteins were found to be strongly induced in the free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans upon treatment with a plant extract and a fraction enriched in condensed tannins23. Although still little is known about the ecology of C. elegans, this species is surrounded by decomposing organic materials such as fruits or stems in its natural habitat, providing bacteria as food source24,25,26. Fruits, in turn, are common sources of tannins27,28 and the nematode may be exposed to tannins derived from rotting plant material29 in its surroundings. It is therefore conceivable that the two hypothetical proline-rich proteins represent a protective mechanism against tannins, however, their function remains unclear. Aim of the current study was therefore, to confirm the presence of PRPs in C. elegans and to investigate their potential role in tannin defense.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

If not stated otherwise, chemicals were purchased from AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany). A hydroethanolic extract from the leaves of Combretum mucronatum Schumach. & Thonn. (CM) and its PACs, procyanidin B2 (purity 96%, HPLC-UV) and procyanidin C1 (purity 95%, HPLC-UV), were obtained as described previously30. The acetone-water (7:3) extract from the aerial parts of Phyllanthus urinaria L. (PU) together with its major ellagitannin, geraniin (purity 98%, HPLC-UV), were prepared as described by Jato et al.31.

C. elegans strains and culture conditions

Wild-type (WT) C. elegans (N2 Bristol strain), RG3081 clx-1(ve581) IV32 and GE24 pha-1 (e2123) III were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota) and were maintained on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar with Escherichia coli (strain OP50) as food source33,34. C. elegans strains created in our laboratories are listed in Table 1.

All strains were kept at 20 °C, except for pha-1 mutants that were grown at 15 °C or at 25 °C after pha-1 rescue35,36.

Age synchronous cultures were obtained by hypochlorite treatment of adult hermaphrodites. Briefly, worms were rinsed off the agar plates in M9 buffer and after removal of the supernatant, the worm pellet was treated with alkaline hypochlorite solution (1.7 mL water, 0.2 mL sodium hypochlorite (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), 0.1 mL 10 M NaOH) for 7 min with constant agitation. The solution was then centrifuged at 4500 × g for 1 min and after removal of the supernatant, the egg pellet was washed at least three times with M9 buffer37.

Generation of vectors

For the construction of reporter gene plasmids, gene sequences were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA (Gene Jet Genome DNA Purification Kit, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) using Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA). PCR products were cloned into the respective vectors by ligation (T4 DNA ligase (Thermo Fisher Scientific)) or using the In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Clontech, Takara Bio, USA) according to standard protocols. All primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

clx-1p::clx‐1::gfp and clx-1p::gfp constructs

A promoter fragment including 2000 bp of the upstream region and the complete coding sequence of clx-1 was cloned into pPD95.77 kindly provided by A. Fire (Carnegie Institute, Baltimore, MD). Additionally, promoter fragments including approx. 2000 bp, 1500 bp, 1000 bp, 350 bp–250 bp upstream of clx-1 without the sequence of clx-1 were fused to GFP.

T22D1.2p::T22D1.2::gfp and various T22D1.2p::gfp constructs

A promoter fragment containing 2000 bp of the upstream region and the complete coding sequence of T22D1.2 was amplified and cloned into pPD95.77. The start codon for GFP was subsequently removed from the plasmid by site directed mutagenesis as described below.

Strain WWU701 evaEx101 [T22D1.2p::gfp + rol−6(su1006)] was generated as described previously23. In addition, promoter fragments of approx. 1500 bp, 350 bp and 250 bp upstream of T22D1.2, respectively were cloned into pPD95.77.

vit-5p::T22D1.2::gfp

The coding sequence of T22D1.2 was amplified and cloned into pPD49.83 carrying a promoter fragment of 2000 bp upstream of vit-538. The start codon of GFP was subsequently removed from the plasmid by site directed mutagenesis.

Site directed mutagenesis was performed using QuickChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) to remove the start codon of the gfp coding sequence from pPD95.77 or pPD49.86 as described above, as well as to insert sgRNA targeting T22D1.2 into vector pDD162. To generate the clx-1,T22D1.2 double knockout mutant, sgRNA targeting T22D1.2 was introduced into plasmid pRB1017 as described by Arribere et al.39. Guide sequences were designed using the online tool CRISPOR40.

Generation of transgenic C. elegans

Transgenic C. elegans lines were established by microinjection using pBX (temperature selection) as selection marker. Reporter gene plasmids were microinjected into the germline of young adult pha-1 mutants together with selection marker plasmid pBX36. Germline transformation of GE24 pha-1 (e2123) for the generation of T22D1.2 knockout mutants was performed by microinjection of plasmid pDD162 (50 ng/µL) containing the sgRNA targeting T22D1.2, together with pJW1285 (kind gift from Jordan Ward (Addgene plasmid # 61252))35 and a repair template for pha-1 co-conversion35. Germline transformation of RG3081 clx-1(ve581) was performed by co-injection of pDD162, pJA58 (kind gift from Andrew Fire (Addgene plasmid # 59933))38, pRB1017 containing T22D1.2 targeting sgRNA and repair templates to edit the dpy-10 (CACTTGAACTTCAATACGGCAAGATGAGAATGACTGGAAACCGTACCGCATGCGGTGCCTATGGTAGCGGACTTCA CATGGCTTCAGACCAACAGCCTAT39) and T22D1.2 locus, respectively. Inclusion of a restriction site for BamHI facilitated genotyping35 of the roller F1 progeny and of the F2 progeny showing a wild-type phenotype, respectively39. Genotyping PCRs were performed using single-worm lysate as DNA template. Briefly, 3 µL lysis buffer (10 mmol/L TRIS pH 8.0, 50 mmol/L KCl, 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0,45% Tween® 20, 0.05% gelatin, 1 mg/mL proteinase K) containing a single worm were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and lysed at 65 °C for 1 h, followed by proteinase K inactivation at 95 °C for 15 min. PCR amplification was carried out using DreamTaq™ DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific, USA) with 0.5 µL of DNA template. 5 µL of PCR product were used for BamHI digestion (FastDigest restriction enzymes, Thermo Scientific, USA). DNA sequences were additionally determined for PCR products from homozygous F2 progeny (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany). Primer sequences are listed in supplementary Table S1.

Isolation and identification of GFP fusion proteins

CLX-1 and T22D1.2 fused to GFP were isolated from young adult worms of strains WWU202, WWU203 and WWU205. Unlike WWU205, it was necessary to induce protein expression in WWU202 and WWU203 by incubating the animals for 18 h in a solution of CM (200 µg/mL), followed by three washing steps with M9 buffer to remove residual extract solution. Worms were pelleted, frozen in liquid nitrogen and lysed in RIPA buffer (10 mmol/L TRIS buffer pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5 mmol/L EDTA, 1% Triton™ X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% sodium deoxycholate) including 1 µL protease inhibitor cocktail (P8849, Sigma-Adrich, Germany) using a Minilys® homogenizer (Bertin Instruments, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France). 300 µL of dilution buffer (10 mM Tris/Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA) for subsequent use with GFP-Trap® Magnetic Particles M-270 (ChromoTek, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany) were added to the lysate, followed by centrifugation at 4 °C for 20 min at 16,000 × g to remove debris. The protein concentration was determined as described by Bradford41 with bovine serum albumin as standard. The GFP fusion proteins were purified from the lysates using GFP-Trap® Magnetic Particles M-270 according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the SDS-sample buffer for elution. The respective fusion proteins were detected by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blot analysis using a rabbit anti-GFP primary antibody (1:5000; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:10000; Dianova).

Purified proteins were identified by mass spectrometry (MS) at the Mass spectrometry-based Proteomics Unit Biology of Plants (MSPUB) of the University of Münster according to standard procedures described previously38. Samples were prepared from gel slices after destaining and protease digestion according to established protocols42 as previously described38. For each sample, the most appropriate protease was selected, i.e., elastase was used for CLX-1::GFP, T22D1.2::GFP (from WWU203) was trypsinized, and T22D1.2::GFP (from WWU205) was first digested by LysC and then by pepsin. For protein identification, MS data were matched to the target sequences of the respective fusion proteins using MS Fragger43, SearchGUI44 and MaxQuant45. Peptide sequences obtained for each strain are given as supplementary material.

Treatment of GFP reporter strains with different stressors

Young adult worms (strains WWU701, WWU202 and WWU204) expressing T22D1.2p::gfp or clx-1p::clx‐1::gfp were treated for 6–18 h with different stressors, respectively. Sodium chloride (300 mM), cadmium chloride (8 mM) and juglone (250 µM; Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) were added to NGM agar to achieve the respective concentrations. Heat stress (30 °C) was applied to worms kept on regular NGM plates. Tunicamycin (5 µg/mL; Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), Epicatechin (1 mM; Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), Geraniin (200 µg/mL), Procyanidin C1 (1 mM), Procyanidin B2 (1 mM), as well as the plant extracts PU (200 µg/mL) and CM (2–2000 µg/mL) were solubilized in DMSO and diluted in M9 buffer to the given concentrations. Salts of divalent cations were tested in an 80 mM solution of NaCl at the highest concentration that was tolerated by the worms: 37.5 µM Al2(SO4)3, 1.25 mM NiSO4, 2.75 mM ZnCl2, 3.34 mM CdCl2 and 0.25 mM CuSO4. Worms incubated on regular NGM plates served as negative control. For the assay in liquid medium, a negative control containing 1% DMSO, corresponding to the highest concentration, was included. In addition to young adults, larval stages L1 to L4 of strain WWU203 were treated with CM (200 µg/mL) for 24 h. GFP expression in L4 larvae (WWU203) was additionally monitored after 3 and 6 h. Experiments were performed in triplicate with at least 10 animals for each treatment per biological replicate.

Knockdown of selected transcription factors

RNAi mediated knockdown was performed in T22D1.2p::gfp worms following established protocols46. Age synchronous L1 larvae were grown at 25 °C on NGM agar plates containing 50 µg/mL ampicillin and 2.5 mM iso-propyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) that were supplemented with E. coli HT115, until the nematodes reached young adult stage. The E. coli strain HT115 produced double-stranded RNA of daf-16, skn‐1 and pha‐4, respectively. After incubation on RNAi plates, worms were transferred to M9 buffer containing 0.2 mg/mL CM and treated for 3 h to induce expression of GFP. Experiments were performed in triplicate with at least 10 animals for each treatment per biological replicate.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Fluorescence in GFP reporter strains was determined in the dark by confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM 510, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). An argon laser was use for excitation at 488 nm. The emission (HFT 488) was split by secondary dichroic beamsplitter NFT 545 and was detected using a 505–550 nm bandpass filter. For strains WWU202 and WWU204 treated with CM at 0.2 and 2 mg/mL, the pinhole was set to 1 Airy unit and the detector gain was reduced from 500 to 350. These settings were also applied to assess treated and untreated strains carrying clx-1 and T22D1.2 promoter fragments of varying length. For the clx-1 promoter experiment, images obtained under both acquisition conditions, i.e., setting the gain to 500 or to 350 with reduction of out-of-focus light, respectively, were included as Supplementary Data for comparison. For further analysis, in addition to detection of 505–550 nm (green), the emission above 650 nm (autofluorescence, red) was recorded and subtracted from the GFP signal during image acquisition. Images were taken at a resolution of 2048 × 2048 px and a scan speed of 6. Fluorescence intensities were quantified using ImageJ 1.50i47 and reported in relation to the respective control group. Prior to microscopy, nematodes were transferred to an agarose pad (1% agarose) on a microscope slide and immobilized in levamisole hydrochloride solution (100 mmol/L).

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Levels of clx-1 and T22D1.2 transcripts were quantified by RT-qPCR after treatment of L4 larvae with 0.2 mg/mL CM in M9 buffer for 30 min, 2 h and 24 h, respectively. An additional group of worms was treated for 2 h, washed with M9 buffer to remove residues of the plant extract, and was then allowed to recover on NGM plates for another 24 h. For every treatment, a corresponding negative control receiving 0.1% DMSO, equivalent to the DMSO content in the CM solution, was included. Prior to RNA isolation, all samples were thoroughly washed at least three times with M9 buffer. All following steps were performed as described previously23. The NucleoSpin® RNA, Mini Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) was used for RNA isolation, Y45F10D.4 and pmp-3 were used as housekeeping genes48. All primer sequences are listed in Table S1. Experiments were performed in at least three independent replicates.

C. elegans mortality after tannin treatment

The susceptibility towards tannin treatment was assessed in C. elegans strains WWU202, WWU203, WWU205 and WWU207 compared to the wild-type as control. Age synchronous young adult worms were rinsed off NGM agar plates and were washed in M9 buffer. Ten to twenty animals were transferred to a 48-well plate containing CM solutions in a concentration range of 0.02 to 5 mg/mL and 5 µL of E. coli OP50 as food source in a volume of 250 µL per well. To avoid bacterial growth during the assay and interaction with the test samples, overnight cultures were repeatedly frozen in liquid nitrogen, followed by incubation at 70 °C for 10 min. The bacterial suspension was centrifuged at 6500 × g for 1 min, the supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in M9 buffer. A solution of 2% DMSO, corresponding to the highest DMSO concentration used in the assay, served as negative control. After 48 h of incubation at 25 °C, survival was assessed by counting the number of dead versus living worms in each well. Immotile nematodes were considered dead if their bodies were fully straight and they did not respond to touch with an eyelash. Strains that were usually maintained at 20 °C were cultured at 25 °C for at least 14 days prior to the test to avoid additional stress due to the elevated temperature. All assays were performed in three independent experiments with four technical replicates per treatment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed using GraphPad Prism® 10 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Differences among mean values were determined by ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Two genes, clx-1 and T22D1.2 were previously found to be strongly up-regulated in C. elegans in response to condensed tannins and are hypothesized to play a potential role in tannin defense23. Therefore, the first step in characterizing their function was to evaluate their expression pattern in more detail. Due to its unique sequence and strong up-regulation in previous experiments23, our primary focus was on T22D1.2. In the first step, a time and concentration-dependent up-regulation of the gene was observed in C. elegans L4 larvae expressing a GFP fusion protein of T22D1.2. The animals were stressed for up to 24 h with a plant extract from Combretum mucronatum (CM), which had previously been characterized and is known to contain large amounts of condensed tannins30. As shown in Fig. 1a, no fluorescence was observed in the untreated control group, whereas tannin treatment at different concentrations led to expression of the fusion protein in the intestine. In animals receiving the same treatment, the fluorescence intensity increased with the time of exposure to CM (Fig. 1b). In addition, the expression of T22D1.2 in different developmental stages was investigated and fluorescence was detected in the intestine of all treated larvae (Fig. 1c).

Representative images of C. elegans strain WWU203 after incubation with CM in M9 buffer. (a) Concentration dependent expression after 24 h and (b) time dependent expression of T22D1.2::GFP at 0.2 mg/mL CM. (c) Expression of T22D1.2::GFP was observed in all larval stages after treatment with CM at 0.2 mg/mL for 24 h. UC: Untreated control. Scale bar 50 μm. Experiments were performed in triplicate with at least ten animals per replicate.

In the next step, young adult worms were incubated with a selection of common stressors in addition to CM to assess whether the expression of T22D1.2 could be part of a general stress response or is induced more specifically by the treatment with tannins. Strain WWU204 carrying a promoter-GFP fusion showed stronger fluorescence and was therefore used in this experiment instead of WWU203. As shown in Fig. 2, T22D1.2 was not expressed at all in the untreated control (Fig. 2a), but was markedly induced by the treatment with CM (Fig. 2h-j). Regarding the expression in worms incubated on NGM agar plates with non-tannin stressors, weak fluorescence could only be detected in animals treated with the heavy metal cadmium chloride (8 mM; Fig. 2b-g).

C. elegans strain WWU204 expressing GFP under control of the T22D1.2 promoter after treatment with different stressors for 18 h. Representative GFP fluorescence images of the respective animals: (a) Untreated control, (b) heat stress (30 °C), (c) osmotic stress (300 mM NaCl), (d) heavy metal stress (8 mM CdCl2), (e) oxidative stress (250 µM juglone), (f) untreated control in M9 buffer including 1% DMSO, (g) endoplasmic reticulum stress (5 µg/mL tunicamycin), (h-j) C. mucronatum extract at 0.02 mg/mL, 0.2 mg/mL and 2 mg/mL, (k) Geraniin (0.2 mM), (l) P. urinaria extract (0.2 mg/mL). Scale bar 50 μm. Experiments were performed in triplicate with at least ten animals per replicate.

To determine whether astringent but structurally unrelated compounds cause the same induction of GFP expression, a phytochemically characterized extract of Phyllanthus urinaria (PU) together with its major constituent, the ellagitannin geraniin, was studied in the same way. In line with the hypothesis that T22D1.2 expression is induced by astringent compounds, PU as well as geraniin also resulted in significantly fluorescent worms (Fig. 2k, l). To further corroborate the assumption that the expression of T22D1.2 is linked to the astringent properties of the tannins, structurally related flavan-3-ol derivatives of increasing size were tested in the same assay. Fluorescence was again barely detectable in worms treated with epicatechin (Fig. 3a). Epicatechin represents the monomeric unit of PAC found in CM and was expected to have the lowest ability to precipitate proline-rich proteins among the three compounds49. In line with previous findings concerning the interaction with salivary proteins49, GFP expression increased with molecular size, i.e., with an increasing number of flavan-3-ol units and thus with increasing astringency (Fig. 3b and c).

Representative images of C. elegans strain WWU701 expressing pT22D1.2::gfp after treatment with (a) epicatechin, (b) procyanidin B2 and (c) procyanidin C1 for 6 h in M9 buffer. Structures depicting the respective compounds are given on the right. Scale bar 100 μm. Experiments were performed in triplicate with at least ten animals per replicate.

The observation that treatment with CdCl2 also induced weak fluorescence, prompted us to investigate the effect of other multivalent metals in strain WWU204, as metal ions are also generally capable to cause an astringent perception50. Besides cadmium chloride, GFP expression was only detectable in worms treated with copper sulfate (Fig. 4a). This was unexpected, because aluminum and zinc salts have also been reported to cause astringency in humans51,52,53.

Expression of pT22D1.2::gfp in C. elegans strain WWU204. (a) Representative images of worms after 18 h treatment with salts of different multivalent cations (b: 37.5 µM Al2(SO4)3; c: 1.25 mM NiSO4; d: 2.75 mM ZnCl2; e: 3.34 mM CdCl2; f: 0.25 mM CuSO4). a: untreated control. Tested concentrations correspond to the highest concentrations tolerated by the worms. Scale bar 200 µM. (b) GFP expression during RNAi mediated knockdown of transcription factors daf-16, skn-1 and pha-4 in worms treated with 0.2 mg/mL CM. E. coli HT115 containing the empty vector L4440 served as control with its fluorescence intensity set to 1. Boxes represent median values with upper and lower quartile, whereas each data point represents the fluorescence of one animal. Experiments were performed in triplicate with at least ten animals per replicate.

To further confirm that the induction of T22D1.2 is not part of a general stress response, GFP expression was monitored in strain WWU204 during RNAi-mediated knockdown of selected transcription factors involved in various stress-related pathways. Neither knockdown of daf-16, skn-1 nor pha-4 resulted in altered expression of the fusion protein in CM treated nematodes (Fig. 4b), corroborating the idea that the up-regulation of this proline-rich protein is linked to the astringent properties of the tannins and not controlled by typical stress related transcription factors.

Similar to T22D1.2, the expression of a CLX-1::GFP fusion protein was investigated in the presence of different stressors. Again, an induction of protein expression was detected exclusively in response to the treatment with tannins (Fig. 5). The results obtained from the reporter fusion experiments were further corroborated by RT-PCR, where the number of transcripts in the untreated control was either very low (clx-1) or even below the threshold of detection (T221D.2) at different timepoints after treatment (Supplementary Fig. S1).

C. elegans strain WWU202 expressing CLX-1::GFP after treatment with different stressors for 18 h. Representative GFP fluorescence images of the respective animals: (a) UC: Untreated control, (b) heat stress (30 °C), (c) osmotic stress (300 mM NaCl), (d) heavy metal stress (8 mM CdCl2), (e) oxidative stress (250 µM juglone), (f) untreated control in M9 buffer including 1% DMSO, (g) endoplasmic reticulum stress (5 µg/mL tunicamycin), (h-j) C. mucronatum extract at 0.02 mg/mL, 0.2 mg/mL and 2 mg/mL, (k) Geraniin (0.2 mM), (l) P. urinaria extract (0.2 mg/mL). Scale bar 50 μm. Experiments were performed in triplicate with at least ten animals per replicate.

In the next step, the corresponding proteins were isolated and their sequence analyzed, in order to verify that T22D1.2 and clx-1 were translated into proline-rich proteins. The respective GFP fusion proteins were obtained via GFP-Trap and their sequences were analyzed by mass spectrometry. Characteristic repetitive proline-rich fragments were detected in both of the isolated proteins (Fig. 6), indicating that the respective genes were indeed translated. Already during the course of plasmid construction for cloning, sequencing of the gene region of T22D1.2 revealed a slight deviation from the anticipated gene sequence obtained from WormBase54. The hypothetical gene is located on chromosome IV (IV:6,921,878.6,922,109), but the respective sequence amplified from genomic DNA included two additional repeats within the highly repetitive region. Further, detection of an additional guanine base at 302 bp resulted in another repeat instead of a predicted intron (Supplementary Table S2).

Protein sequences of (a) T22D1.2::GFP from WWU203 and (b) CLX-1::GFP from WWU202. Peptides detected by MS analysis are highlighted in grey. Sequences of signal peptides predicted by SignalP6.055 are given in italics. Bold: Proline units within the repetitive part of the sequences. Underlined: Sequence of GFP.

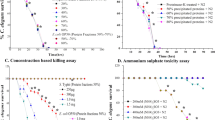

Due to their similarity to human basic salivary proline-rich proteins and their strong induction by tannins, we speculated that CLX-1 and T22D1.2 could represent a mechanism of defense. Therefore, the susceptibility towards CM was assayed in C. elegans overexpressing CLX-1 or T22D1.2 and in mutants that were deficient for the two proteins. Surprisingly, transgenic worms overexpressing either clx-1 (Fig. 7a) or T22D1.2 (Fig. 7b) did not show improved resistance towards treatment with CM. On the other hand, the susceptibility of knockout mutants was not increased, either, compared to the wild-type (Supplementary Fig. S2), not even in the clx-1/T22D1.2 double knockout mutant (Fig. 7c). However, when T22D1.2 was constitutively expressed under the strong vit-5 promoter, resistance in strain WWU205 significantly increased at lower concentrations versus the wild-type strain (Fig. 7d).

Mortality rates of different C. elegans strains after treatment with CM for 48 h at different concentrations compared to the wild-type N2 Bristol strain. No differences were observed for (a) worms overexpressing clx-1 or (b) worms overexpressing T22D1.2 as GFP fusion proteins, respectively. (c) Knockout of both genes, clx-1 as well as T22D1.2 did not lead to an increase in mortality. (d) Expression of T22D1.2 under a stronger promoter (pvit-5) significantly enhanced resistance towards treatment with CM at lower concentrations. Bars represent means ± SEM. *: p < 0.05, determined by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons.

To investigate the regulatory mechanisms of clx-1 and T22D1.2 and identify potential regulatory elements in their promoter regions, promoter fragments of varying lengths were fused to GFP. While no fluorescence was detected at all in the untreated groups, treatment with CM induced the expression of GFP (Fig. 8a, b). With altered microscope settings using a higher detector gain unsuitable for the treated group, also untreated worms with GFP expression under the clx-1 promoter were brightly fluorescent (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Expression of GFP in C. elegans controlled by promoter fragments of different length. (a) Fragments of 2000 bp, 1500 bp, 350 bp and 250 bp upstream of T22D1.2 did not lead to fluorescence in untreated animals (top), but induced GFP expression after treatment with 0.2 mg/mL CM for 18 h (bottom). (b) Fragments of 2000 bp, 1500 bp, 1000 bp, 350 bp and 250 bp upstream of clx-1 did not lead to detectable expression of GFP under the applied acquisition settings in untreated animals (top), but GFP expression was induced by treatment with 0.2 mg/mL CM (bottom). Scale bar 100 μm. Experiments were performed in triplicate with at least ten animals per replicate.

Discussion

Two genes, clx-1 and T22D1.2 that had previously been shown to be strongly induced in C. elegans exposed to condensed tannins23 were further characterized in this study. Both were found to be translated into proteins consisting of a signal peptide, a highly repetitive proline-rich region and a short non-repetitive sequence before the proline-rich repeats and the C-terminus of the protein. Such a sequence is strongly reminiscent of proline-rich proteins in different mammalian species56,57, although the amino acid composition of the repeats varied considerably in the worm. Further, both proteins are predicted to be orthologs of basic salivary proline-rich proteins in humans (T22D1.2: PRB4 and CLX-1: PRB1)58. Similar to the expression pattern observed in our study, PRPs are not constitutively expressed in rats or mice, but induced after administration of tannin-rich feeds8,59. GFP fusions of both proteins were detected in the worms’ intestine, suggesting they could confer a mechanism of defense against tannins ingested during food uptake from C. elegans’ natural surroundings. The observation that strain WWU205 (vit-5p::T22D1.2::gfp) was more resistant to the treatment with tannins supports this hypothesis. On the other hand, a knockout of both genes was expected to increase susceptibility of strain WWU207 compared to the wild type, but no difference was observed. Even if we assume that these PRPs possess a protective role, they may not represent the only mechanism of defense against tannins. Moreover, the parameter assessed was the mortality at concentrations that are typical for tannin-containing fruits60,61. However, tannins certainly exert detrimental effects in nematodes also at sublethal concentrations62. An induction of PRPs may therefore still confer protection which was not captured by the mortality assay. Despite their similarities in response to various stressors, there are certain differences between T22D1.2 and clx-1. Regarding the protein sequence, CLX-1 also shares structural similarities with collagens, especially the glycine-proline-proline (GPP) motif63,64. However, in contrast to CLX-1, the GPP sequence is frequently found within non-repetitive regions of collagens64, and the tandem repeats occurring in CLX-1 are not characteristic for collagens, either. Still, they do not resemble those of salivary PRPs as strongly as the tandem repeats found in T22D1.2 with blocks of up to five proline residues57.

Concerning the regulation of the two genes, we did not identify a transcription factor or a motif within the promoter region that induces their transcription. In the transcriptional clx-1 reporters with varying promoter fragments, GFP expression was generally detectable, whereas for T22D1.2, it was only induced upon tannin stress. In humans, macaques and several rodent species, salivary-specific cAMP-responsive elements (CRE) have been associated with the regulation of PRPs56,65,66. Although C. elegans is known to possess CREs67, we did not identify a respective characteristic motif in the promoter region. Previously, clx-1 was found to be activated by the removal of germ line stem cells, but not by skn-168. On the other hand, down-regulation of clx-1 was observed during knockdown of skn-169. Moreover, together with several other genes coding for cuticle collagens, clx-1 was among the most strongly down-regulated genes following treatment of C. elegans with copper sulfate70, which is in contrast to our findings for T22D1.2. An up-regulation was reported in a dpy-7 mutant showing disruptions of the furrows and, different to the current study, at high levels of sodium chloride, but only after 24 h of exposure69. Even if CLX-1 is not a collagen and was detected in the intestine, its co-expression with cuticle collagens and the impact of cuticle disruptions on its expression suggest that CLX-1 might not represent a direct mechanism of defense against tannins. Rather, it could be related to the destructive effects of tannins that bind to the nematode cuticle as their primary target71,72, although no alterations in the expression of cuticle collagens were observed in C. elegans after short-term treatment with condensed tannins23.

Regarding the microscopic images obtained in this study, it should be noted that fluorescence intensities generally varied extremely across the different samples, in line with the transcription of clx-1 and T22D1.2 observed in the qPCR experiments. While in some samples, GFP expression was not observed at all, treatment with tannins led to a strong increase in fluorescence. Following general recommendations to avoid saturation73,74,75, it was therefore impossible to acquire all images under the same conditions. On the other hand, differences in the treated versus the control group were not always depicted accurately this way. We tried to account for this problem by including the microscopic data for both groups.

The current results further suggest that the expression of the two proline-rich proteins may be linked to the astringent properties of the test substances. In humans, the perception of astringency is a tactile sensation that seems to be mainly mediated by an interaction of tannins or other astringent molecules with salivary proteins such as PRPs, and a subsequent loss of lubrication of the oral mucosa50,76. If the sensation of astringency leads to an up-regulation of T22D1.2, we would also expect a stronger response to the exposure to metal ions. However, it could be that the tolerated concentrations of the respective salts, especially of aluminum sulfate, were too low to induce the expected effects. Additionally, susceptibility to and perception of astringency may vary between distantly related organisms, such as humans and nematodes. Elucidating the trigger for the induction of clx-1 and T22D1.2 in C. elegans as well as identification of the connecting elements between the collagenous, tannin binding cuticle and their up-regulation will be topics of further research.

In summary, our findings provide evidence that T22D1.2 is translated into a PRP-like protein that seems to act in a similar way like salivary PRPs in mammals. Besides a set of yet functionally uncharacterized proline-rich effectors in the plant parasitic nematode Pratylenchus penetrans21, this is the first report of PRPs that putatively act as a mechanism of defense against tannins in invertebrates.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Khanbabaee, K., van Ree, T. & Tannins Classification and definition. Nat. Prod. Rep. 18, 641–649 (2001).

Quideau, S., Deffieux, D., Douat-Casassus, C. & Pouységu, L. Plant polyphenols: chemical properties, biological activities, and synthesis. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 586–621 (2011).

Haslam, E. Natural polyphenols (vegetable tannins) as drugs: possible modes of action. J. Nat. Prod. 59, 205–215 (1996).

Melzig, M. F. Plant polyphenols as inhibitors of hydrolases are regulators of digestion. Complement. Med. Res. 30, 453–459 (2023).

Eppe, J. et al. Oak acorn poisoning in cattle during autumn 2022: A case series and review of the current knowledge. Animals 13 (2023).

Shimada, T. Salivary proteins as a defense against dietary tannins. J. Chem. Ecol. 32, 1149–1163 (2006).

Hagerman, A. E. & Butler, L. G. The specificity of proanthocyanidin-protein interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 4494–4497 (1981).

Mehansho, H. et al. Modulation of proline-rich protein biosynthesis in rat Parotid glands by sorghums with high tannin levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 80, 3948–3952 (1983).

Austin, P. J., Suchar, L. A., Robbins, C. T. & Hagerman, A. E. Tannin-binding proteins in saliva of deer and their absence in saliva of sheep and cattle. J. Chem. Ecol. 15, 1335–1347 (1989).

Mole, S., Butler, L. G. & Iason, G. Defense against dietary tannin in herbivores: A survey for proline rich salivary protein in mammals. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 18, 287–293 (1990).

Mau, M., Südekum, K. H., Johann, A., Sliwa, A. & Kaiser, T. M. Saliva of the graminivorous Theropithecus gelada lacks proline-rich proteins and tannin-binding capacity. Am. J. Primatol. 71, 663–669 (2009).

Schmitt, M. H., Shrader, A. M. & Ward, D. Megaherbivore browsers vs. tannins: is being big enough? Oecologia 194, 383–390 (2020).

Barbehenn, R. V. Peter constabel, C. Tannins in plant-herbivore interactions. Phytochemistry 72, 1551–1565 (2011).

Karowe, D. N. Differential effect of Tannic acid on two tree-feeding lepidoptera: implications for theories of plant anti-herbivore chemistry. Oecologia 80, 507–512 (1989).

Forkner, R. E., Marquis, R. J. & Lill, J. T. Feeny revisited: condensed tannins as anti-herbivore defences in leaf‐chewing herbivore communities of Quercus. Ecol. Entomol. 29, 174–187 (2004).

Martin, J. S., Martin, M. M. & Bernays, E. A. Failure of Tannic acid to inhibit digestion or reduce digestibility of plant protein in gut fluids of insect herbivores: implications for theories of plant defense. J. Chem. Ecol. 13, 605–621 (1987).

Konno, K., Hirayama, C. & Shinbo, H. Glycine in digestive juice: A strategy of herbivorous insects against chemical defense in host plants. J. Insect Physiol. 43, 217–224 (1997).

Desmedt, W., Mangelinckx, S., Kyndt, T. & Vanholme, B. A phytochemical perspective on plant defense against nematodes. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 602079 (2020).

Collingborn, F. M., Gowen, S. R. & Mueller-Harvey, I. Investigations into the biochemical basis for nematode resistance in roots of three musa cultivars in response to Radopholus similis infection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48, 5297–5301 (2000).

Castillo, P. & Vovlas, N. Pratylenchus (Nematoda: Pratylenchidae): Diagnosis, Biology, Pathogenicity and Management 361 (Brill, 2007).

Vieira, P. et al. Identification of candidate effector genes of Pratylenchus penetrans. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 19, 1887–1907 (2018).

Vieira, P. et al. A new esophageal gland transcriptome reveals signatures of large scale de Novo effector birth in the root lesion nematode Pratylenchus penetrans. BMC Genom. 21, 738 (2020).

Spiegler, V., Hensel, A., Seggewiss, J., Lubisch, M. & Liebau, E. Transcriptome analysis reveals molecular anthelmintic effects of procyanidins in C. elegans. PLOS ONE 12 (2017).

Félix, M. A. & Braendle, C. The natural history of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 20, R965–R969 (2010).

Kiontke, K. & Sudhaus, W. Ecology of Caenorhabditis species. WormBook (eds. The C. elegans Research Community). https://doi.org/10.1895/wormbook.1.37.1 (2006).

Schulenburg, H. & Félix, M. A. The natural biotic environment of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 206, 55–86 (2017).

Smeriglio, A., Barreca, D., Bellocco, E. & Trombetta, D. Proanthocyanidins and hydrolysable tannins: occurrence, dietary intake and Pharmacological effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174, 1244–1262 (2017).

Santos-Buelga, C. & Scalbert, A. Proanthocyanidins and tannin-like compounds - nature, occurrence, dietary intake and effects on nutrition and health. J. Sci. Food Agric. 80, 1094–1117 (2000).

Wadhwa, M., Bakshi, M. P. S. & Makkar, H. P. S. Wastes to worth: value added products from fruit and vegetable wastes. CABI Rev. 1–25 (2016).

Spiegler, V., Sendker, J., Petereit, F., Liebau, E. & Hensel, A. Bioassay-Guided fractionation of a leaf extract from Combretum mucronatum with anthelmintic activity: oligomeric procyanidins as the active principle. Molecules 20, 14810–14832 (2015).

Jato, J. et al. Anthelmintic activities of extract and ellagitannins from Phyllanthus urinaria against Caenorhabditis elegans and zoonotic or animal parasitic nematodes. Planta Med. 89, 1215–1228 (2023).

Au, V. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 methodology for the generation of knockout deletions in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 9, 135–144 (2019).

Brenner, S. Genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 (1974).

Stiernagle, T. Maintenance of C. elegans in WormBook (eds. The C. elegans Research Community). https://doi.org/10.1895/wormbook.1.101.1 (2006).

Ward, J. D. Rapid and precise engineering of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome with lethal mutation co-conversion and inactivation of NHEJ repair. Genetics 199, 363–377 (2015).

Granato, M., Schnabel, H. & Schnabel, R. pha-1, a selectable marker for gene transfer in C. elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 1762–1763 (1994).

Lewis, J. A. & Fleming, J. T. Basic culture methods in Methods in Cell Biology (eds Epstein, H. F. & Shakes, D. C.) 13 (Elsevier, 1995).

Lubisch, M. et al. Using Caenorhabditis elegans to produce functional secretory proteins of parasitic nematodes. Acta Trop. 225, 106176 (2022).

Arribere, J. A. et al. Efficient marker-free recovery of custom genetic modifications with CRISPR/Cas9 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 198, 837–846 (2014).

Concordet, J. P. & Haeussler, M. CRISPOR: intuitive guide selection for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing experiments and screens. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W242–W245 (2018).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Shevchenko, A., Tomas, H., Havlis, J., Olsen, J. V. & Mann, M. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2856–2860 (2006).

Kong, A. T., Leprevost, F. V., Avtonomov, D. M., Mellacheruvu, D. & Nesvizhskii A. I. MSFragger: ultrafast and comprehensive peptide identification in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat. Methods. 14, 513–520 (2017).

Barsnes, H., Vaudel, M. & SearchGUI A highly adaptable common interface for proteomics search and de Novo engines. J. Proteome Res. 17, 2552–2555 (2018).

Cox, J. & Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 (2008).

Ahringer, J. Reverse Genetics in WormBook (eds. The C. elegans Research Community). https://doi.org/10.1895/wormbook.1.47.1 (2006).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH image to imageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 671–675 (2012).

Hoogewijs, D., Houthoofd, K., Matthijssens, F., Vandesompele, J. & Vanfleteren, J. R. Selection and validation of a set of reliable reference genes for quantitative sod gene expression analysis in C. elegans. BMC Mol. Biol. 9, 9 (2008).

de Freitas, V. & Mateus, N. Structural features of Procyanidin interactions with salivary proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 940–945 (2001).

Bajec, M. R., Pickering, G. J. & Astringency Mechanisms and perception. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 48, 858–875 (2008).

Brossaud, F., Cheynier, V. & Noble, A. C. Bitterness and astringency of grape and wine polyphenols. Aust J. Grape Wine Res. 7, 33–39 (2001).

Keast, R. The effect of zinc on human taste perception. J. Food Sci. 68, 1871–1877 (2003).

Lim, J. & Lawless, H. T. Oral sensations from iron and copper sulfate. Physiol. Behav. 85, 308–313 (2005).

WormBase web site. http://www.wormbase.org, release WS255, Accessed 10 Oct 2016.

Teufel, F. et al. SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein Language models. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1023–1025 (2022).

Carlson, D. M. Salivary Proline-rich proteins: biochemistry, molecular biology, and regulation of expression. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 4, 495–502 (1993).

Mehansho, H., Butler, L. G. & Carlson, D. M. Dietary tannins and salivary proline-rich proteins: interactions, induction, and defense mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 7, 423–440 (1987).

Kim, W., Underwood, R. S., Greenwald, I. & Shaye, D. D. OrthoList 2: A new comparative genomic analysis of human and Caenorhabditis elegans genes. Genetics 210, 445–461 (2018).

Mehansho, H., Clements, S., Sheares, B. T., Smith, S. & Carlson, D. M. Induction of proline-rich glycoprotein synthesis in mouse salivary glands by isoproterenol and by tannins. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 4418–4423 (1985).

Jolicoeur, C. The New Cider Maker’s Handbook. A Comprehensive Guide for Craft Producers (Chelsea Green Publ, 2013).

Prommajak, T., Leksawasdi, N. & Rattanapanone, N. Tannins in fruit juices and their removal. CMUJ Nat. Sci. 19, 76–90 (2020).

Spiegler, V., Liebau, E. & Hensel, A. Medicinal plant extracts and plant-derived polyphenols with anthelmintic activity against intestinal nematodes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 34, 627–643 (2017).

Williamson, M. P. The structure and function of proline-rich regions in proteins. Biochem. J. 297, 249–260 (1994).

Johnstone, I. L. The cuticle of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: A complex collagen structure. BioEssays 16, 171–178 (1994).

Ann, D. K., Lin, H. H. & Kousvelari, E. Regulation of Salivary-Gland-Specific gene expression. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 8, 244–252 (1997).

Lin, H. H., Kousvelari, E. E. & Ann, D. K. Sequence and expression of the MnP4 gene encoding basic proline-rich protein in macaque salivary glands. Gene 104, 219–226 (1991).

Smith, B. et al. Evolution of motif variants and positional bias of the cyclic-AMP response element. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 1–9 (2007).

Steinbaugh, M. J. et al. Lipid-mediated regulation of SKN-1/Nrf in response to germ cell absence. eLife 4 (2015).

Dodd, W. et al. A damage sensor associated with the cuticle coordinates three core environmental stress responses in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 208, 1467–1482 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Integrating transcriptomics and behavior tests reveals how the C. elegans responds to copper induced aging. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 222, 112494 (2021).

Greiffer, L., Liebau, E., Herrmann, F. C. & Spiegler, V. Condensed tannins act as anthelmintics by increasing the rigidity of the nematode cuticle. Sci. Rep. 12, 18850 (2022).

Herrmann, F. C. & Spiegler, V. Caenorhabditis elegans revisited by atomic force microscopy - Ultra-structural changes of the cuticle, but not in the intestine after treatment with Combretum mucronatum extract. J. Struct. Biol. 208, 174–181 (2019).

Brown, C. M. Fluorescence microscopy – avoiding the pitfalls. J. Cell. Sci. 120, 3488 (2007).

Ogama, T. A beginner’s guide to improving image acquisition in fluorescence microscopy. Biochem. (Lond). 42, 22–27 (2020).

Cromey, D. W. Avoiding twisted pixels: ethical guidelines for the appropriate use and manipulation of scientific digital images. Sci. Eng. Ethics. 16, 639–667 (2010).

Gibbins, H. L. & Carpenter, G. H. Alternative mechanisms of astringency – What is the role of saliva? J. Texture Stud. 44, 364–375 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Martin Scholz and Susan Hawat, Mass spectrometry‐based Proteomics Unit Biology of Plants at the University of Münster for mass spectrometric measurements of protein samples.The project was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project 423277515 (HE1642/12-1 and LI 793/16-1). In addition, we acknowledge support from the Institute of Pharmaceutical Biology and Phytochemistry, University of Münster.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.G., L.R., C.S.K. and V.S. performed the experiments and analysed the data. C.S.K., E.L. and V.S. supervised the experiments. V.S. drafted the article, E.L., C.S.K. and L.G. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. E.L. and V.S. designed the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Greiffer, L., Ressmann, L., Kaiser, C.S. et al. Induction of proline-rich proteins in response to tannin treatment in Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci Rep 15, 29399 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11651-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11651-1