Abstract

Previous studies have suggested a potential correlation between obesity and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). This study aimed to elucidate pathogenic pathways connecting obesity and IPF and identify diagnostic biomarkers for obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis. Obesity and IPF datasets were obtained through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Differential expression analysis and weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) were used to identify shared genes for obesity and IPF. Functional enrichment (GO/KEGG), protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, and machine learning algorithms were applied to screen hub genes, validated by ROC curves. High-fat diet (HFD)-induced obese mice with bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis underwent histological assessment and qRT-PCR validation. Molecular docking evaluated flavonoid binding to hub genes. We identified 128 shared genes between obesity and IPF, predominantly enriched in immune and inflammatory pathways. Machine learning prioritized three hub genes (NLRC4, SPI1, and NCF2), validated by ROC analysis (AUC > 0.7). In animal model, these genes exhibited significant upregulation, correlating with exacerbated fibrosis. Molecular docking highlighted strong binding affinities (-6.3 to -9.6 kcal/mol) between dietary flavonoids and hub targets. Immune-inflammatory dysregulation links obesity and IPF via NLRC4, SPI1, and NCF2. These genes serve as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets, with flavonoids showing intervention potential. Our findings advance mechanistic insights into obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic interstitial lung disease (ILD) of unknown etiology, which is characterized by interstitial, distal airway, and alveolar remodeling1,2. The prevalence of IPF ranges from 20 to 80 patients per 100,000 individuals, and the prognosis is poor, with a 5-year survival rate similar to various cancers2,3. Currently, the treatment options for IPF are limited, only nintedanib and pirfenidone have been utilized to slow the progression of the disease4.

Obesity is a major global public health concern, primarily resulting from an imbalance between calorie intake and expenditure5. It is characterized by a chronic inflammatory state, with elevated levels of systemic pro-inflammatory mediators6,7. Obesity has been implicated in the development of pulmonary fibrosis through several potential mechanisms, including chronic low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic dysregulation8. Recent studies have identified a causal association between obesity and IPF9,10, emphasizing the need to consider obesity as a contributing factor in the management of IPF. However, studies addressing the underlying molecular mechanisms of obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis remain limited.

Some studies have attempted to investigate the association between obesity and pulmonary fibrosis. Obesity induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) can lead to elevated levels of important mediators associated with the development of IPF, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β7,11. These inflammatory mediators stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, which then secrete large amounts of extracellular matrix (ECM), leading to excessive ECM deposition and the formation of pulmonary fibrosis12. Furthermore, a study has shown that excessive intake of saturated fatty acids and meat may increase the risk of developing IPF13. Another study suggests that obesity induced by neonatal overfeeding may be a potential risk factor for pulmonary fibrosis14. These results indicate an association between obesity and IPF. However, the potential pathogenic mechanisms by which obesity leads to IPF are complex and not fully understood. Investigating the possible pathogenesis of IPF is crucial for improving management and treatment strategies for IPF. Therefore, more molecular mechanism studies are needed to further elucidate the enigma between obesity and IPF.

With the rapid advancement in life sciences and computer technology, bioinformatics analysis offers a promising approach to deciphering complex disease patterns in large amounts of biological data and exploring the molecular mechanisms of disease pathophysiology. Several studies have used bioinformatics analysis to explore the disease mechanisms of IPF and potential avenues for therapeutic intervention, providing new clues for subsequent research15,16,17. Machine learning, a scientific discipline at the intersection of statistics and computer science, focuses on how computers learn from data18. The application of machine learning in bioinformatics is evolving, allowing researchers to identify the best interpretable features in the data effectively19. This integration enhances understanding of the underlying information and patterns, facilitating deeper insights into the relationships within the data.

In this study, we performed histological analysis in the animal models. Then we identified key genes associated with obesity-related IPF by analyzing obesity and IPF datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the Limma package, and key module genes were selected through weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). Functional enrichment analysis and protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed, followed by machine learning and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to pinpoint hub genes linked to obesity-related IPF. These hub genes were validated via qRT-PCR, and their relationship with immune cell infiltration was explored to better understand the molecular immunological mechanisms underlying obesity-related IPF. By identifying shared gene signatures and pathways, this study aims to deepen our understanding of the pathogenesis of obesity-related IPF and highlight potential therapeutic targets to improve patient outcomes.

Methods

Data collection

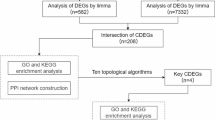

We downloaded gene expression datasets for obesity (GSE151839) and IPF (GSE28042, GSE24206, and GSE53845) from the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). Supplementary Table 1 provides more details about the aforementioned datasets. The research design of this study is clearly displayed in Fig. 1.

Animal models and experimental design

All experimental procedures were in compliance with the guidelines published by the National Institutes of Health (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th edition) and they fulfilled the ARRIVE guidelines. All experimental procedures were performed with the approval of the Animal Care and Utilization Committee of Xiamen Medical College.

C57BL/6 male mice, obtained from Shanghai Slac Laboratory Animal Co., LTD., were used in this study. All mice were housed under standard laboratory conditions with ad libitum access to water and chow diets, and maintained on a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. These mice were randomly divided into three groups: the control (Ctrl) group, the bleomycin (BLM) group, and the obesity + bleomycin (obe + BLM) group. Mice in the Ctrl group and BLM group were fed a normal diet (ND), while those in the obe + BLM group were fed a high-fat diet (HFD), the composition of which is provided in Supplementary Table 2. After 14 weeks, pulmonary fibrosis was induced in the BLM group and the obe + BLM group by intratracheal instillation of BLM (2 U/kg). Twenty-one days post-instillation, all mice were euthanized using cervical dislocation, and lung tissues were harvested for subsequent analysis.

Histological analysis

Mouse lung tissues were obtained and immediately fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution. After fixation, the tissues were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin, and sections of 5 μm thick slices. Subsequently, Masson’s trichrome staining was utilized for collagen detection. Additionally, the degree of fibrosis was assessed using the Collagen volume fraction (CVF, calculated as the collagen-positive area divided by the total tissue area) and the Ashcroft score20.

Identification of DEGs and modular genes

Differential expression analysis was performed using the Limma package to identify DEGs between obesity and control samples in GSE151839, as well as between IPF and control samples in GSE2804221. The analysis was conducted with thresholds of |log2 Fold change (FC)| > 1 and adjusted P value < 0.05. Heatmaps and volcano plots of the DEGs were generated using the pheatmap and ggplot2 packages.

We constructed co-expression networks using the WGCNA package for the GSE151839 and GSE28042 datasets22. First, the “goodSamplesGenes” function was used to eliminate the unqualified genes and samples. Second, we calculated the adjacency using the “soft” threshold power (β) and then converted it into a topological overlap matrix (TOM). Third, we detected modules using hierarchical clustering and a dynamic tree cut function. Through average linkage hierarchical clustering, with a TOM-based dissimilarity metric, we classified genes with similar expression patterns into modules, each containing at least 100 genes. The modules were further merged based on the module eigengenes dissimilarity threshold (MEDissThres) 0.25. Finally, Pearson correlation analysis was used to analyze and establish the correlation between modules and clinical phenotypes, selecting the module with the highest correlation with obesity or IPF as the core module.

Given that the genes from the core module represent a set of similarly expressed genes, they may not fully encompass the DEGs. To avoid missing genes that are crucial for disease in the integration with DEGs, we first identified genes at the intersection of modules exhibiting the strongest positive or negative correlations with obesity and those with IPF. These intersection genes were then combined with DEGs, followed by deduplication, to identify shared genes.

Functional enrichment analysis

To investigate the biological functions and specific mechanisms of the shared genes connecting obesity and IPF, we performed GO and KEGG enrichment analyses using the ClusterProfiler package23. Data visualisation using Rstudio or bioinformatics tools (www.bioinformatics.com.cn). The significance threshold was set at an adjusted P value < 0.05.

Screening candidate hub genes by PPI networks and machine learning

We constructed a PPI network based on the shared genes using the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/)24, selecting “Homo sapiens” as the organism and a medium confidence score threshold of 0.4. We then imported the PPI network into Cytoscape (version 3.10.2) and used the MCC algorithm from the CytoHubba plugin to identify the top 20 scoring genes within the network. Following this, we use multiple machine learning methods for further analysis. We used the GSE28042 dataset as the training dataset, and the GSE24206 and GSE53845 datasets as the external validation datasets. We further refined the top 20 genes identified by the MCC algorithm and defined the model with the highest average area under the curve (AUC) across the training and validation datasets as the optimal model. The genes within this optimal model were designated as candidate hub genes.

Identification of hub genes

We conducted ROC curve analysis using the pROC package to calculate the AUC and the 95% confidence interval, further evaluating the diagnostic performance of the candidate hub genes25. Candidate hub genes with an AUC value greater than 0.7 were considered to have good diagnostic performance, and those with an AUC greater than 0.7 were selected as hub genes for subsequent analysis. Furthermore, the expression levels of the hub genes were assessed in the GSE151839 and GSE28042 datasets.

Immune infiltration analysis

CIBERSORT is a method that uses tissue gene expression profiles to identify different immune cell proportions26. To better understand the immune cell infiltration between the control and the IPF group, we performed an analysis based on the CIBERSORT algorithm. The ggplot2 package was used to visualize the proportion of each immune cell across different samples. Next, we employed the Corrplot package to create a correlation heatmap, visualized the relationships among the 22 immune cell types. Finally, we conducted Spearman correlation analysis to assess the relationship between hub gene expression and the levels of immune cell infiltration.

Molecular docking

We selected six representative compounds (Luteolin, Naringenin, Kaempherol, Epicatechin, Daidzein, and Peonidin) from flavonoids as potentially active ingredients, and utilized three hub target proteins as receptors for molecular docking simulations to calculate the binding affinities between the potential active ingredients and hub targets. The 3D crystal structure files of compounds were obtained from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The 3D crystal structures of hub target proteins were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). AutoDock Vina (version 1.1.2) was used for molecular docking and PyMoL (version 2.5.1) was used for the visualization of docking results.

mRNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Applygen Technologies, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was carried out using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the Promega GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Relative mRNA expression levels were quantified using the 2−△△Ct method. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.1) and GraphPad Prism 8. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

HFD-induced obesity aggravates BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis in vivo

To investigate the impact of HFD-induced obesity on BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis, we analyzed lung tissue morphology via Masson staining and quantified fibrosis progression through Collagen Volume Fraction (CVF) and Ashcroft score. HFD-induced obesity exacerbated BLM-induced lung injury in mice, characterized by alveolar structural disruption, thickening of alveolar septa, and collagen deposition (Fig. 2A). Quantitative analysis revealed that the obe + BLM group exhibited significantly higher CVF and Ashcroft scores compared to the BLM group (Fig. 2B, C). These findings demonstrate HFD-induced obesity synergistically amplifies fibrotic severity.

Identification of shared genes for obesity and IPF

We identified 274 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the obesity dataset and 195 DEGs in the IPF dataset using the Limma package. These results were visualized through heatmaps and volcano plots (Fig. 3A-D), with the heatmap highlighting the top 30 most significantly upregulated and downregulated genes. The intersection of DEGs between obesity and IPF yielded a total of 5 overlapping DEGs (Fig. 3E).

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). (A) Heatmap presenting the top 30 obesity DEGs in GSE151839. (B) Volcano plot representing obesity DEGs in GSE151839. (C) Heatmap presenting the top 30 IPF DEGs in GSE28042. (D) Volcano plot representing IPF DEGs in GSE28042. (E) Venn diagram illustrating 5 overlapping DEGs between obesity and IPF.

We then performed WGCNA to identify co-expressed gene profiles in two datasets, GSE151839 and GSE28042. Based on Scale independence and mean connectivity, 7 and 10 were chosen as the optimal soft-threshold power β for obesity and IPF, respectively, to ensure the construction of biologically meaningful scale-free networks (Fig. 4A, B). In the obesity dataset, we identified 27 modules, and in the IPF dataset, we identified 25 modules (Fig. 4C, D). After merging similar modules, 20 modules were identified in the obesity model and 20 modules were identified in the IPF model. (Fig. 4E, F). Subsequently, we calculated the correlations between the modules and the clinical phenotypes. For obesity, the pink module, which includes 784 genes, demonstrated the strongest positive correlation (r = 0.71, p = 4e-04), and the blue module, containing 3420 genes, had the strongest negative correlation with obesity (r = -0.87, p = 8e-07) (Fig. 4E). Meanwhile, the brown module, containing 1976 genes, had the strongest positive correlation with IPF (r = 0.58, p = 1e-09), and the darkturquoise module, containing 142 genes, had the strongest negative correlation with IPF (r = -0.49, p = 8e-07) (Fig. 4F).

As shown in the Venn diagrams (Fig. 4G, H), there were 110 overlapping genes within the positively correlated modules and 13 overlapping genes within the negatively correlated modules. Finally, by merging the overlapping DEGs with the modular genes and removing duplicates, we identified a total of 128 shared genes.

WGCNA analysis for screening key module genes for obesity and IPF. (A) Determination of the optimal soft thresholds for GSE151839. (B) Determination of the optimal soft thresholds for GSE28042. (C) Clustering dendrograms of genes in GSE151839, with different colors representing different modules. (D) Clustering dendrograms of genes in GSE28042, with different colors representing different modules. (E) Heatmap of the correlation between modules and obesity. Red color represents a positive correlation and blue color represents a negative correlation. (F) Heatmap of the correlation between modules and IPF. Red color represents a positive correlation and blue color represents a negative correlation. (G) Venn diagram illustrating 110 overlapping genes within the positively correlated modules. (H) Venn diagram illustrating 13 overlapping genes within the negatively correlated modules.

Shared genes enriched in immune-inflammatory pathways drive obesity-IPF pathogenesis

To uncover the potential biological mechanisms linking obesity and IPF, we performed GO and KEGG functional enrichment analysis on the shared genes. The GO analysis results showed that the shared genes were mainly enriched in the following aspects: (1) biological process, including immune response-activating signaling pathway, positive regulation of response to biotic stimulus, and immune response − regulating cell surface receptor signaling pathway; (2) cellular component, including endocytic vesicle, phagocytic vesicle, and secretory granule lumen; and (3) molecular function, including Toll-like receptor binding, pattern recognition receptor activity, and inhibitory MHC class I receptor activity (Fig. 5A). The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that the shared genes were mainly enriched in signaling pathways, including the B cell receptor signaling pathway and NF-κ B signaling pathway (Fig. 5B, C). The results of the functional enrichment analysis suggest that the potential biological mechanisms connecting obesity and IPF may be primarily related to immunity and inflammation.

Machine learning prioritizes hub genes linking obesity and IPF

We constructed a PPI network using the shared genes, excluding unconnected nodes, resulting in a network with 80 nodes and 347 edges (Supplementary Fig. 1). We then utilized the MCC algorithm from the CytoHubba plugin to identify the top 20 genes within the network (Fig. 6A). Following this, we use multiple machine learning methods screening these top 20 genes. As shown in Fig. 6B, the optimal machine learning combination, consisting of the glmBoost and Stepglm[both] algorithms, achieved the highest average AUC score. The AUC for the training set (GSE28042) and validation sets (GSE24206 and GSE53845) are both greater than 0.7, reflecting the robustness of the model (Fig. 6C). The optimal combination identified 5 candidate hub genes (NLRC4, SPI1, SYK, NCF2, and TLR1). Furthermore, we evaluated the diagnostic value of the 5 candidate hub genes using ROC curves in the obesity dataset (GSE151839) and IPF dataset (GSE28042), respectively. As shown in Fig. 7A-B, based on the criterion of AUC > 0.7, NLRC4, SPI1, and NCF2 were selected as the hub genes. Compared to the healthy control group, NLRC4, SPI1, and NCF2 were all significantly upregulated in both obese patients and pulmonary fibrosis patients (Fig. 7C, D).

Identification of candidate hub genes by PPI networks and machine learning. (A) The 10 genes were identified according to MCC algorithms from the CytoHubba plugin in Cytoscape. (B) AUC scores of machine learning combinations within the training and validation datasets. The genes within the optimal machine learning combination (first-ranked) were selected as candidate hub genes. (C) ROC curves for the GSE28042, GSE24206, and GSE53843 datasets.

Identification of hub genes. (A) ROC curves of NLRC4, SPI1, SYK, NCF2, and TLR1 in the obesity dataset, respectively. (B) ROC curves of NLRC4, SPI1, SYK, NCF2, and TLR1 in the IPF dataset, respectively. (C) Expression of NLRC4, SPI1, SYK, NCF2, and TLR1 in the obesity dataset, respectively. (D) Expression of NLRC4, SPI1, SYK, NCF2, and TLR1 in the IPF dataset, respectively.

Hub genes are significantly upregulated in HFD-induced obese mice with pulmonary fibrosis

To further validate the accuracy of the aforementioned comprehensive bioinformatics analysis, we verified the expression of the three hub genes in animal models. As shown in Fig. 8, the results of qRT-PCR confirmed that the expression of NLRC4, SPI1 and NCF2 were all significantly upregulated compared to the healthy control group, consistent with the findings from the transcriptomic analysis.

Immune cell infiltration analysis

Based on the results of enrichment analysis, we found that the shared genes were mainly involved in immunity and inflammation. To further investigate this, we applied the CIBERSORT algorithm to perform an immune infiltration analysis. Figure 9A demonstrates the proportions of 22 immune cell types in each sample. Compared to the healthy group, the IPF group exhibited higher levels of T cells follicular helper and monocytes, while T cells CD4 naïve, T cells CD4 memory resting, T cells CD4 memory activated, NK cells resting, and Macrophages M1 were lower (Fig. 9B). The correlation analysis of the 22 immune cell types revealed close positive or negative associations between different immune cell types (Fig. 9C). Furthermore, we further explored the associations between the 3 hub genes and different types of immune cells to identify the commonalities among the hub genes. We found that the 3 hub genes were all associated with monocytes and T cells CD8, NLRC4 and SPI1 were both associated with neutrophils, and SPI1 and NCF2 were both associated with T cells follicular helper (Fig. 9D-F).

Immune cell infiltration analysis. (A) The proportion of 22 immune cell types in each sample. (B) Boxplots showing the pattern of immune cell infiltration in the healthy control group and IPF group. (C) The correlations between immune cells. Red indicates a positive correlation, while blue indicates a negative correlation. (D-F) The correlations between the expression of three hub genes (NLRC4, SPI1, and NCF2) and immune cells. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Dietary flavonoids exhibit high-affinity binding to hub targets

NLRC4, SPI1, and NCF2 are important hubs linking obesity and pulmonary fibrosis, serving as promising hub targets for treating obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis. Therefore, molecular docking simulations were conducted to assess the binding affinities between the potential active ingredients and hub targets. As shown in the heatmap (Fig. 10A), the docking scores ranged from − 6.3 to -9.6 kcal/mol, indicating good binding affinity between the potential active compounds and the hub targets. The visualization between each potential active ingredient and hub targets is shown in Fig. 10B.

Molecular docking analysis of flavonoid compounds targeting hub proteins. (A) Heatmap illustrating binding affinities (kcal/mol) between six dietary flavonoids (Luteolin, Naringenin, Kaempferol, Epicatechin, Daidzein, Peonidin) and three hub targets (NLRC4, SPI1, NCF2). (B) Representative 3D structural models of six dietary flavonoids and three hub targets. Hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions are highlighted in dashed lines and surface shading, respectively.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that obesity is closely associated with pulmonary fibrosis. For instance, Wu et al. reported that obesity may significantly increase the risk of developing IPF9. Obesity is associated with various risk factors for IPF, including a decline in lung function, chronic lung inflammation, and a high prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease27. However, the potential factors and molecular mechanisms underlying obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis are not fully understood. In this study, we aimed to elucidate the common molecular mechanisms between obesity and pulmonary fibrosis through comprehensive bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation. Animal experiments confirmed that HFD-induced obesity may exacerbate pulmonary fibrosis by increasing inflammation and collagen production. A total of 128 shared genes for obesity and IPF were identified, with these genes primarily regulate disease onset and progression through immune and inflammatory pathways. Further, through PPI network, machine learning and ROC curve analysis, we identified 3 hub genes (NLRC4, SPI1, and NCF2) that exhibited good diagnostic performance in both obesity and IPF, and qRT-PCR experiments further confirmed that the expression of the three hub genes was up-regulated in lung tissue of animal model. Finally, we also performed molecular docking simulation to investigate the binding between representative compounds in flavonoids and hub targets, which highlighted the potential of flavonoids to intervene in therapeutic targets. These findings provide new insights into the pathophysiological link between obesity and pulmonary fibrosis and may inform future strategies for managing obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis.

Obesity and IPF both involve inflammation and immune dysregulation28,29. The enrichment analysis and immune infiltration analysis in this study indicated that the shared genes between obesity and IPF are primarily associated with inflammatory and immune-related processes, such as the immune response-activating signaling pathway, Toll-like receptor binding, and the NF-κ B signaling pathway. This suggests that inflammatory and immune mechanisms may be essential for the onset and progression of obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis. The NF-κ B signaling pathway is widely recognized as a key participant in inflammation and immune regulation30. In the obese state, adipocytes secrete more pro-inflammatory substances, which can lead to the activation of the NF-κ B signaling pathway31. Numerous studies have indicated that the activation of the NF-κ B signaling pathway is associated with the development of pulmonary fibrosis32,33. Furthermore, obesity may lead to ectopic fat deposition in the lung, which can impair the function of lung lipofibroblasts and contribute to lipotoxicity34. Altered cellular metabolism and disruption of lipid homeostasis can stimulate the development of macrophages into foam cells, which further promotes the development of pulmonary fibrosis35,36. Taken together, these findings suggest that the imbalance in inflammation and immune regulation in the obese states may bridge the gap in obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis.

NLR family CARD domain-containing protein 4 (NLRC4), which contains an N-terminal CARD structural domain, a central NACHT structural domain, and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat structural domain, plays an important role in infections and inflammatory diseases37,38. NLRC4 can activate various forms of programmed cell death, including pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis, which are essential for eliminating pathogens from the host following infection37. However, it is important to note that the overactivation of NLRC4 can lead to abnormal cell death and cytokine release, which is detrimental to the body. For example, Canna et al. reported that a novel missense mutation (c.1009 A > T, p.Thr337Ser, ) in the nucleotide-binding domain of NLRC4 leads to constitutive Caspase-1 cleavage in transduced cells and increased the production of IL-18 in patients and NLRC4 mutant macrophages39. The role of NLRC4 in fibrotic diseases has also been preliminarily investigated. A previous study exploring host-microbe interactions in IPF showed that NLRC4 expression levels were upregulated in the IPF cohort, which was associated with increased lung microbial burden, suggesting that it may be one of the persistent stimuli contributing to repetitive alveolar injury in IPF40. Currently, there are no studies reporting whether obesity promotes pulmonary fibrosis through the upregulation of NLRC4. Our study fills this gap, and our data indicate that NLRC4 is significantly upregulated in animal models of obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis.

The transcription factor Spi-1 proto-oncogene (SPI1, also known as PU.1) is a key regulator of signaling in the immune system and is involved in the development of several different types of immune lineage precursor cells41,42. Research has reported that SPI1 may be a mediator of obesity-induced adipose inflammation and insulin resistance43. Insulin resistance has been demonstrated to mediate high-fat diet-induced pulmonary fibrosis through the TGF-β1 pathway7. Additionally, SPI1 plays a significant role in the reprogramming of fibroblasts. SPI1 can polarize resting fibroblasts and repolarize inflammatory fibroblasts that degrade ECM into a fibrotic phenotype that produces ECM44. Whereas pharmacological and genetic inactivation of SPI1 disrupts the fibrotic network, reprogramming fibrotic fibroblasts back to a resting state, which leads to the regression of fibrosis in multiple organs45. In this study, we found that SPI1 is significantly upregulated in an obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis animal model. Therefore, targeting SPI1 may effectively improve the reprogramming of fibroblasts and interfere with excessive ECM deposition, providing a new therapeutic option for the treatment of IPF.

Neutrophil Cytosolic Factor 2 (NCF2/p67phox) is a subunit of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, an enzyme that produces superoxide in the phagosomes of neutrophils and other phagocytic leukocytes and is used to neutralize foreign microbes and cellular debris46. The literature on NCF2 mainly focused on immune infiltration, oxidative stress, and inflammation-related diseases47. NCF2 is a cytosolic subunit of the NADPH oxidase complex that generates ROS, and alterations in NCF2 lead to alterations in ROS production, thereby impacting disease processes48,49. It has been shown that vitamin D (VitD) can regulate ROS production by downregulating NCF2 expression50. Interestingly, chronic vitamin D deficiency caused by obesity is associated with pulmonary fibrosis, and supplementation with vitamin D can alleviate obesity-induced pulmonary fibrosis51. This suggests that NCF2 may play an important role in the interplay between VitD and obesity-induced pulmonary fibrosis. NCF2 has been found to be associated with fibrosis in several organs52,53. Our study found that the mRNA expression level of NCF2 is significantly elevated in obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis, thereby addressing the gap between NCF2 and pulmonary fibrosis to some extent. Overall, NCF2 may be a promising therapeutic target for pulmonary fibrosis.

Flavonoids exhibit anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and metabolic regulatory effects with low toxicity, and hold significant potential in the treatment of obesity and pulmonary fibrosis54,55,56,57. Our molecular docking analysis provides novel mechanistic insights into their multi-target regulatory potential. The high-affinity binding (-6.3 to -9.6 kcal/mol) observed between six representative flavonoids and the disease hub targets NLRC4, SPI1, and NCF2 suggests these compounds may directly modulate the obesity-fibrosis axis through inflammasome regulation (NLRC4), transcriptional reprogramming (SPI1), and oxidative stress pathways (NCF2). Given their established safety profile and bioavailability enhancement through dietary formulations, these promising and economically viable natural dietary bioactive compounds will likely serve as effective modulators for obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis.

Our immune cell infiltration analysis revealed that all three hub genes (NLRC4, SPI1, NCF2) were associated with monocytes and T cells CD8. This suggests that the association of the hub genes with monocytes and T cells CD8 may contribute to our understanding of the association of the hub genes with obesity-related pulmonary fibrosis. Peripheral blood monocytes, part of the innate immune system, serve as precursors to tissue macrophages58. It has been shown that obesity leads to a shift in the monocyte compartment towards pro-inflammatory and immunosuppressive phenotypes, contributing to the development of low-grade inflammation in obesity59. This suggests that obesity leads to dysregulation of monocyte subsets, which may be a significant factor exacerbating pulmonary fibrosis. The association of hub genes with monocytes may suggest their potential role in the inflammatory process. However, comprehensive evidence is currently lacking to confirm whether obesity upregulates hub genes via inducing monocyte subset dysregulation to promote pulmonary fibrosis, which warrants validation in future studies. Currently, most studies have suggested that CD8⁺ T cells play a pro-fibrotic role in pulmonary fibrosis60,61. Differently, there are also studies that come to a different point of view. One study showed that CD8⁺ T cells diffusely infiltrate the parenchyma of fibrotic tissues in IPF and can differentiate into cells producing IFN-γ but not IL-4, thereby attenuating fibrosis62. Another study has shown that CD8⁺ T cells produced by tolerogenic APC can limit the development of pulmonary interstitial fibrosis63. The differences in these findings may be due to the heterogeneity of CD8⁺ T cells, where different subsets or activation states lead to distinct functions. The intrinsic properties of these cells and the crosstalk between various immune cell types remain poorly understood in the context of obesity-associated pulmonary fibrosis. Deeper analysis at single-cell resolution is needed in the future to better understand the cellular characteristics of the characteristic immune cells in fibrosis.

It is important to note that our study has some limitations. First, although the present study provides a preliminary validation of the conclusions through animal experiments, species differences still require attention, further observations and studies in patients with both diseases are necessary to better elucidate the potential connections between obesity and pulmonary fibrosis. Second, possible dataset bias must be considered. GEO data come from different research teams around the world, and samples from different datasets may have ethnographic heterogeneity, differences in collection standards, and errors due to different testing platforms, and different testing technologies. Third, the detailed molecular mechanisms were preliminarily explored in this study, but further experimental and clinical studies are needed for more in-depth validation and exploration.

In summary, this study is the first to integrate multiple bioinformatics approaches to analyze the potential pathogenic mechanisms underlying the connection between obesity and IPF. We found that immune and inflammatory responses may serve as common pathological mechanisms underlying these two diseases. Additionally, we identified the hub genes NLRC4, SPI1, and NCF2, which may serve as potential therapeutic targets for obesity-related IPF, contributing to the development of new treatment strategies. In the future, additional clinical disease samples are needed to further confirm the clinical value of these hub genes, and more comprehensive studies will be required to investigate the mechanisms in more detail.

Data availability

All of the datasets used in this study came from publicly accessible resources found at Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

References

Moss, B. J., Ryter, S. W. & Rosas, I. O. Pathogenic mechanisms underlying idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 17, 515–546 (2022).

Bonella, F., Spagnolo, P. & Ryerson, C. Current and future treatment landscape for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Drugs 83, 1581–1593 (2023).

King, T. E. et al. A phase 3 trial of Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl. J. Med. 370, 2083–2092 (2014).

Karampitsakos, T., Juan-Guardela, B. M., Tzouvelekis, A. & Herazo-Maya, J. D. Precision medicine advances in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. EBioMedicine 95, 104766 (2023).

Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 288–298 (2019).

Li, T. et al. Exploring the common gene signatures and pathogeneses of obesity with alzheimer’s disease via transcriptome data. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 1072955 (2022).

Park, Y. H. et al. Insulin resistance mediates high-fat diet-induced pulmonary fibrosis and airway hyperresponsiveness through the TGF-β1 pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 51, 1–12 (2019).

Wang, X., Yi, X. & Tang, D. Aerobic exercise improves pulmonary fibrosis by improving insulin resistance and inflammation in obese mice. Front. Physiol. 12, 785117 (2021).

Wu, W. et al. Genetic association of telomere length, obesity and Tobacoo smoking with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis risk. BMC Public. Health. 23, 868 (2023).

Yoon, H-Y., Kim, H., Bae, Y. & Song, J. W. Body mass index is associated with clinical outcomes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 14, 11921 (2024).

Guo, X., Sunil, C. & Qian, G. Obesity and the development of lung fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 812166 (2021).

Inui, N., Sakai, S. & Kitagawa, M. Molecular pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis, with focus on pathways related to TGF-β and the Ubiquitin-Proteasome pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6107 (2021).

Miyake, Y. et al. Dietary fat and meat intake and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a case-control study in Japan. Int. J. Tuberc Lung Dis. 10, 333–339 (2006).

Ye, Z. et al. Obesity induced by neonatal overfeeding worsens airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation. PLoS One. 7, e47013 (2012).

Li, N. et al. Bioinformatic analysis of differentially expressed genes and pathways in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann. Transl Med. 9, 1459–1459 (2021).

Dasgupta, S. Identification and molecular modelling of potential drugs targeting the genes involved in the progression of lung cancer in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Gene Rep. 37, 102067 (2024).

Wu, Z. et al. Identifying potential biomarkers of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis through machine learning analysis. Sci. Rep. 13, 16559 (2023).

Rc, D. Machine Learning in Medicine. Circulation [Internet]. 132. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26572668/ [cited 2024 Oct 16] (2015).

Auslander, N., Gussow, A. B. & Koonin, E. V. Incorporating machine learning into established bioinformatics frameworks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 2903 (2021).

Ashcroft, T., Simpson, J. M. & Timbrell, V. Simple method of estimating severity of pulmonary fibrosis on a numerical scale. J. Clin. Pathol. 41, 467–470 (1988).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 9, 559 (2008).

Yu, G., Wang, L-G., Han, Y. & He, Q-Y. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287 (2012).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D447–452 (2015).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77 (2011).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods. 12, 453–457 (2015).

Lei, W. et al. The causal relationship between physical activity, sedentary time and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis risk: a Mendelian randomization study. Respir Res. 24, 291 (2023).

de Heredia, F. P., Gómez-Martínez, S. & Marcos, A. Obesity, inflammation and the immune system. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 71, 332–338 (2012).

Heukels, P., Moor, C. C., von der Thüsen, J. H., Wijsenbeek, M. S. & Kool, M. Inflammation and immunity in IPF pathogenesis and treatment. Respir Med. 147, 79–91 (2019).

Guo, Q. et al. NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy: new insights and translational implications. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 53 (2024).

Wang, C. Obesity, inflammation, and lung injury (OILI): the good. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 978463 (2014).

Tian, Y. et al. Loss of PTEN induces lung fibrosis via alveolar epithelial cell senescence depending on NF-κB activation. Aging Cell. 18, e12858 (2019).

Jaffar, J., Glaspole, I., Symons, K. & Westall, G. Inhibition of NF-κB by ACT001 reduces fibroblast activity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 138, 111471 (2021).

Cheng, X., Jiang, S., Pan, B., Xie, W. & Meng, J. Ectopic and visceral fat deposition in aging, obesity, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an interconnected role. Lipids Health Dis. 22, 201 (2023).

Venosa, A. et al. Regulation of macrophage foam cell formation during nitrogen mustard (NM)-Induced pulmonary fibrosis by lung lipids. Toxicol. Sci. 172, 344–358 (2019).

Romero, F. et al. A pneumocyte-macrophage paracrine lipid axis drives the lung toward fibrosis. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 53, 74–86 (2015).

Sundaram, B. & Kanneganti, T-D. Advances in Understanding activation and function of the NLRC4 inflammasome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1048 (2021).

Paudel, S. et al. NLRC4 suppresses IL-17A-mediated neutrophil-dependent host defense through upregulation of IL-18 and induction of necroptosis during Gram-positive pneumonia. Mucosal Immunol. 12, 247–257 (2019).

Canna, S. W. et al. An activating NLRC4 inflammasome mutation causes autoinflammation with recurrent macrophage activation syndrome. Nat. Genet. 46, 1140–1146 (2014).

Molyneaux, P. L. et al. Host-Microbial interactions in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 195, 1640–1650 (2017).

Huang, J., Chen, W., Jie, Z. & Jiang, M. Comprehensive analysis of immune implications and prognostic value of SPI1 in gastric Cancer. Front. Oncol. 12, 820568 (2022).

Maghsoudloo, M., Azimzadeh Jamalkandi, S., Najafi, A. & Masoudi-Nejad, A. Identification of biomarkers in common chronic lung diseases by co-expression networks and drug-target interactions analysis. Mol. Med. 26, 9 (2020).

Lin, L. et al. Adipocyte expression of PU.1 transcription factor causes insulin resistance through upregulation of inflammatory cytokine gene expression and ROS production. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 302, E1550–1559 (2012).

Henderson, N. C., Rieder, F. & Wynn, T. A. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature 587, 555–566 (2020).

Wohlfahrt, T. et al. PU.1 controls fibroblast polarization and tissue fibrosis. Nature 566, 344–349 (2019).

Bakutenko, I. Y. et al. Neutrophil cytosolic factor 2 (NCF2) gene polymorphism is associated with juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus, but probably not with other autoimmune rheumatic diseases in children. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 10, e1859 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. A combination analysis based on bioinformatics tools reveals new signature genes related to maternal obesity and fetal programming. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 11, 1434105 (2024).

Jacob, C. O. et al. Lupus-associated causal mutation in neutrophil cytosolic factor 2 (NCF2) brings unique insights to the structure and function of NADPH oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 109, E59–67 (2012).

Chen, Y. et al. NCF1/2/4 are prognostic biomarkers related to the immune infiltration of kidney renal clear cell carcinoma. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 5954036 (2021).

Jaroslawska, J., Ghosh Dastidar, R. & Carlberg, C. In vivo vitamin D target genes interconnect key signaling pathways of innate immunity. PLoS One. 19, e0306426 (2024).

Han, H. et al. Obesity-induced vitamin D deficiency contributes to lung fibrosis and airway hyperresponsiveness. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 64, 357–367 (2021).

Kong, M. et al. Serum response factor (SRF) promotes ROS generation and hepatic stellate cell activation by epigenetically stimulating NCF1/2 transcription. Redox Biol. 26, 101302 (2019).

Clancy, R. M. et al. Cardiac fibroblast transcriptome analyses support a role for interferogenic, profibrotic, and inflammatory genes in anti-SSA/Ro-associated congenital heart block. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 313, H631–H640 (2017).

Martín, M. Á. & Ramos, S. Dietary flavonoids and insulin signaling in diabetes and obesity. Cells 10, 1474 (2021).

Geng, Q. et al. Therapeutic effects of flavonoids on pulmonary fibrosis: A preclinical meta-analysis. Phytomedicine 132, 155807 (2024).

Rufino, A. T., Costa, V. M., Carvalho, F. & Fernandes, E. Flavonoids as antiobesity agents: A review. Med. Res. Rev. 41, 556–585 (2021).

Ngamsamer, C., Sirivarasai, J. & Sutjarit, N. The benefits of anthocyanins against Obesity-Induced inflammation. Biomolecules 12, 852 (2022).

Radushev, V. et al. Dysregulated cytokine and oxidative response in hyper-glycolytic monocytes in obesity. Front. Immunol. 15, 1416543 (2024).

Friedrich, K. et al. Perturbation of the monocyte compartment in human obesity. Front. Immunol. 10, 1874 (2019).

Malaviya, R., Kipen, H. M., Businaro, R., Laskin, J. D. & Laskin, D. L. Pulmonary toxicants and fibrosis: innate and adaptive immune mechanisms. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 409, 115272 (2020).

Sun, X. et al. CD4 + T and CD8 + T cells profile in lung inflammation and fibrosis: targets and potential therapeutic drugs. Front. Immunol. 16, 1562892 (2025).

Deng, L., Huang, T. & Zhang, L. T cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: crucial but controversial. Cell. Death Discov. 9, 62 (2023).

Zhang-Hoover, J. & Stein-Streilein, J. Tolerogenic APC generate CD8 + T regulatory cells that modulate pulmonary interstitial fibrosis. J. Immunol. 172, 178–185 (2004).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (2022J05318); Natural Science Foundation of Xiamen, China (3502Z20227079); the Education Scientific Research Project of Young Teachers of Fujian Province (JAT210475); Doctoral Start-up Foundation of Xiamen Medical College (K2021-12); the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for Undergraduates of Xiamen Medical College (202512631006, 202512631042).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LJC: data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing; HJC, ZNC, KYZ, HSZ, JHX: analysis and interpretation; TSC: conceptualization and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, funding acquisition and final approval of manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data used in this paper are publicly available, ethically approved.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Chen, H., Chen, Z. et al. Shared pathogenic mechanisms linking obesity and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis revealed by bioinformatics and in vivo validation. Sci Rep 15, 25896 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12046-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12046-y