Abstract

There has been a continuous increase in the global incidence of obesity. Rosa roxburghii Tratt (RRT), a plant with medicinal and edible uses, contains active components that can alleviate obesity, indicating an anti-obesity potential. This research sought to investigate the anti-obesity effects of RRT fruit extract (RRTE) and elucidate the underlying mechanisms and components responsible for its action. RRTE was obtained by enriching the active ingredient in RRT and used to treat HepG2 cells. RRTE alleviated cellular lipid accumulation, reduced reactive oxygen species production, restored cellular mitochondrial function, and enhanced energy metabolism. Network pharmacology combined with molecular docking was used to determine the targets, components, and mechanisms, which were validated through in vitro experiments. p-Coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate were identified as lipid-lowering active components that may reduce lipid accumulation and alleviate obesity through the PI3K-Akt and PPAR signaling pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a complex, diverse, and chronic disease that substantially affects overall health, quality of life, and mortality. Recently, its prevalence has been increasing worldwide, making it a global epidemic1. The World Health Organization defines obesity as an abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat that may impair health. Abnormal fat accumulation leads to disorders of lipid metabolism, resulting in various illnesses. Obesity is substantially associated with numerous diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and several cancers2,3. Obesity has emerged as a major challenge for public health systems. Surgical treatments and medications are now mainly used in clinical practice for obesity management; however, these usually involve inconvenience and adverse effects4. Consequently, there is considerable interest in the discovery of natural, safe, and side-effect-free food products with antiobesity properties. The development of natural products with anti-obesity effects is critical for scientific research and clinical applications.

Rosa roxburghii Tratt (RRT), a species within the Rosa genus of the Rosaceae family, is a widely distributed medicinal and edible plant found in southwestern China5. It is rich in bioactive components, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, polysaccharides, amino acids, organic acids, and various vitamins6,7. Furthermore, it exhibits many pharmacological activities, including hypolipidemic, hypoglycemic, anti-oxidant, anti-tumor, anti-fibrotic, and anti-aging effects8. Thus, RRT exerts anti-obesity and lipid-lowering effects. RRT fruit vinegar alleviated obesity and its complications in mice fed a high-fat diet by influencing the intestinal microbiota9. RRT polysaccharides decreased gut inflammation and inhibited the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway to reduce obesity and chronic obesity-induced colitis10. Seed oil of RRT also restrained metabolic disease progression by mitigating lipid accumulation, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response via mitochondrial oxidative metabolism mediated through PPARα/PGC-1α11. However, the anti-obesity and lipid-lowering mechanisms, and components for activation of RRT and its extracts require further exploration.

Natural products are consistent with traditional Chinese medicine and contain multiple bioactive components, which show their efficacy in complex diseases, in the “multi-component, multi-target, multi-pathway” model12. Material foundations and functional mechanisms are the two primary issues in comprehending natural products for disease mitigation. Network pharmacology is a novel approach rooted in systems biology principles that can be employed to predict protein targets of active ingredients in plants and targeted disease pathways13,14. It aims to use a “disease-gene-target-compound” network to reveal the regulatory principles of small molecules and analyze compound combinations to elucidate the mechanisms of action15. Network pharmacology combined with high-throughput compositional analysis can swiftly identify various active compounds present in natural products and predict effective mechanisms based on multiple components and targets, providing a dependable foundation for the mechanism of action and active compounds. Therefore, network pharmacology is an effective tool for the preliminary exploration of mechanisms and active ingredients.

Presently, the use of RRT and its extracts to prevent and treat obesity is rarely reported, and their molecular mechanisms and components of action have not been further investigated. Therefore, in the present study, we enriched the active components of RRT to investigate their lipid-lowering effects. In addition, network pharmacology was used to investigate the target, components, and possible mechanisms involved in RRT fruit extract against obesity. Additional in vitro experiments were performed to confirm the possible components and mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and penicillin-streptomycin solution were purchased from Gibco (USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Zeta-Life (USA). Oleic acid (OA) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). The Oil Red O Stain Kit, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit with JC-1, p-coumaric acid, ethyl caffeate, palmitic acid (PA), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and simvastatin were purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) assay kits were obtained from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Cell Total RNA Isolation Kit was obtained from Foregene Biotechnology (Chengdu, China). The Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix was obtained from Vazyme (Nanjing, China). The ABScript Neo RT Master Mix for qPCR with a gDNA remover was obtained from ABclonal (Wuhan, China).

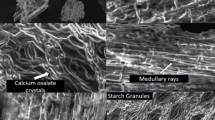

Preparation of RRTE

The method of Li was used to obtain Rosa roxburghii Tratt fruit extract (RRTE)16. In short, RRTE was obtained by alcohol extraction, alkaline solubilization, acid precipitation, and ethyl acetate extraction. Plant materials were obtained from the Rosa Roxburghii Tratt base of Shengjing Street, Panzhou City, Guizhou Province under compliance with local regulations. Since the plant materials (Rosa roxburghii Tratt.) used in this study were commercially sourced from Rosa Roxburghii Tratt base (Shengjing Street, Panzhou City, Guizhou Province, China), no wild collections were made. As per common practice for commercially obtained materials, voucher specimen deposition in a public herbarium was not applicable in this context. To ensure traceability, we have archived photographs of the purchased materials.

Cell culture

Human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2) were obtained from the ATCC (USA). HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The culture dishes were positioned within a cell culture incubator at 37℃ and 5% CO2. The cells were exposed to 0.5 mM free fatty acid (FFA) (OA: PA at a 2:1 ratio) to establish the model.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. HepG2 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well. After confluence, cells were incubated with different concentrations of RRTE and active components in culture medium for 24 h. Subsequently, 20 µL of MTT solution was added to each well and the plates were incubated in the incubator for 2–4 h. DMSO (150 µL) was added after discarding the supernatant. The 96-well plate was placed on a shaker at a constant speed for 10 min, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm17.

Oil Red O staining

HepG2 cells were plated in six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. After confluence, cells were treated with 0.5 mM FFA and different concentrations of RRTE and active components for 24 h. The cells were subsequently treated according to the instructions of the Oil Red O Staining Kit. The images were captured using an inverted microscope. Subsequently, the dye in the cells was dissolved in DMSO and the absorbance was measured at 490 nm.

Detection of biochemical indicators

Cellular intervention was performed as described in Oil Red O Staining Experiment. At the end of the intervention, the cells were collected by treatment with a lysis buffer. TG, TC, ALT, and AST levels were assessed using commercial kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein concentrations of the samples were determined using The BCA protein assay kit. TG, TC, ALT, AST, and protein concentrations were calculated to reflect the actual situation.

Detection of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Cellular intervention was performed as described in Oil Red O Staining Experiment. After the intervention, the culture medium was discarded, and PBS was added for cleaning twice. Cells were digested and collected by EDTA-free trypsin, followed by centrifugation at 4°C for 3 min at 2000 rpm, cleaned once with PBS. Then, 1 mL serum-free medium with 10 µM DCFH-DA was added, incubated in a 37℃ incubator for 30 min, and gently shaken every 10 min. Subsequently, the cells were washed two to three times with serum-free medium to eliminate residual DCFH-DA. After resuspension in PBS, flow cytometry was used to detect fluorescence intensity, while avoiding light throughout the process.

Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

JC-1 dye was used for MMP measurement. Cellular intervention was performed as described in Oil Red O Staining Experiment. After the intervention, the original culture medium was discarded, and PBS was added twice for cleaning. After staining according to the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit with JC-1, observations were conducted under a fluorescence microscope.

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total mRNA was extracted from HepG2 cells using an RNA isolation kit, and cDNA was synthesized using a reverse transcription kit. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green Mix. Cycle conditions: 95℃ for 30 s, one cycle; 95℃ for 10 s, 60℃ for 30 s, 40 cycles; 95℃ for 15 s, 60℃ for 60 s, 95℃ for 15 s, one cycle. Relative mRNA expressions were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method normalized to β-actin, and the primer list is in Supplementary Table S1.

Network Pharmacology analysis

Screening of active compounds in RRTE

In previous study in our laboratory, we obtained the possible components of RRTE using liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry combined with database analysis16. SMILES structures were obtained from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) was used to achieve the GI absorption of Pharmacokinetics and Lipinski of Druglikeness, where only the GI absorption was “high” and Lipinski “Yes; 0 violation” were considered as the active compound.

Target prediction for active compounds and diseases

Selection of the species “Homo sapiens” in the Swiss Target Prediction Database (http://swisstargetprediction.ch/) to obtain potential targets for active compounds. The diseases (obesity) associated targets were collected from the GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/), OMIM (https://omim.org/), and DisGeNET (https://www.disgenet.org/) databases. The active compounds and disease targets were deduplicated separately. The targets were then imported into the VENNY 2.1.0 website (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html) to plot Venn diagrams and identify potential targets for active compounds against obesity.

Protein-Protein interaction (PPI) network construction

A PPI network was constructed using the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/). Cytoscape v3.9.1 software was used to build the PPI network with targets ranked by degree and perform topology analysis.

Enrichment analysis of GO and KEGG

Potential targets for active compounds against obesity were input into Metascape (https://metascape.org/) platform for analysis, in which the species “H. sapiens” was selected, GO and KEGG enrichment analysis was performed on the targets, and the top 20 biological processes and pathways were screened for visualization.

Network construction

A compound-target-pathway-disease network was constructed using Cytoscape v3.9.1 software to visualize the regulatory map of obesity alleviation in RRTE.

Molecular docking

Protein structures were retrieved from the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/) and preprocessed using PyMOL 3.0.3. The structures of the active compounds in RRTE were obtained from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). AutodockVina 1.1.2 was used to calculate the affinity between the active compounds and protein. The results were visualized using PyMOL 3.0.3.

Quantitative analysis of active compounds

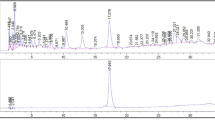

The active compounds content of RRTE was determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. The quantitative process was achieved by comparing with the standard curve (Supplementary Table S2). All samples were prepared with methanol, RRTE was prepared as 8 mg/mL solution.The conditions were set as follows: 0.1% formic acid aqueous was used as solution eluent A, acetonitrile was used as eluent B, the flow rate was 1 mL/min, the in jection volume was 10 µL, and the column temperature was 40 ℃. The following elution were performed: 0 min, 95% (A); 2 min, 70% (A); 5 min, 30% (A); 7 min, 10% (A); 8 min, 10% (A); 10 min, 95% (A).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times and data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data analysis and figures were generated using GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 and Excel. One-way ANOVA was used for difference analysis, and Dunnett’s t-test was used as a post-hoc test (# p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 VS Group Control; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 VS Group Model).

Results

Effect of RRTE on lipid accumulation

To investigate the toxicity of FFA and RRTE on HepG2 cells, an MTT assay was used to measure the viability of HepG2 cells after treatment with various concentrations of FFA and RRTE for 24 h. The results demonstrated a significant decrease in cell viability when the concentrations of FFA and RRTE reached 1 mM/L and 1000 µg/mL, respectively, after the intervention (Fig. 1A and B). Therefore, 0.5 mM/L FFA and 600, 750, and 900 µg/mL of RRTE as low, medium, and high doses, respectively, were selected for subsequent experiments.

Effects of RRTE on lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells. (A, B) Effect of FFA and RRTE on HepG2 cells viability (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 VS Group 0). (C) intracellular lipid droplets in HepG2 cells stained with Oil Red O (100×). (D) Quantitative analysis of Oil Red O staining. (E, F) RRTE reduced intracellular triglyceride and triglyceride content. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 VS Group Control; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 VS Group Model.

Oil Red O staining was used to evaluate the effects of RRTE and simvastatin (40 µM)18 on cell lipid accumulation. Absorbance was measured after DMSO decolorization to quantitatively assess the cellular lipid content. The results revealed that FFA treatment caused a notable increase in lipid accumulation, and RRTE reversed the FFA-induced lipid accumulation in a dose-dependent manner. Despite its favorable lipid-lowering effect, RRTE was not superior to simvastatin (Fig. 1C and D).

The intracellular levels of TG and TC were measured to further demonstrate the lipid-lowering effects of RRTE. These results also indicate that FFA induction increases intracellular TG and TC levels. However, RRTE significantly reduced the intracellular TG and TC levels in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1E and F). In summary, these findings suggest that RRTE mitigates FFA-induced lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells.

Effect of RRTE on mitochondrial function and cellular damage

Mitochondria are the key organelles involved in lipid metabolism. Lipid disorders cause excessive ROS production, which, in turn, affects mitochondrial function. In HepG2 cells, lipid overaccumulation caused an excessive increase in ROS levels, and RRTE significantly reduced the ROS levels (Fig. 2A and B). Excessive ROS levels may interfere with the cellular MMP. In the Model group, lipid accumulation led to a decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential, whereas RRTE reversed this phenomenon (Fig. 2C). Additionally, the assessment of mitochondrial biogenesis markers showed that FFA intervention reduced AMPK mRNA expression. Similarly, SIRT1 and PGC-1a mRNA expression was significantly reduced in the Model group. AMPK and SIRT1 mRNA levels were significantly higher after treatment with different doses of RRTE (Fig. 2D and E). In contrast, PGC-1a mRNA expression was significantly elevated after RRTE interventions at low and medium doses, but unaffected at high doses (Fig. 2F).

Protective effects of RRTE on mitochondrial function and cellular damage in HepG2 cells. (A, B) RRTE reduced intracellular ROS levels. (C) Effect of RRTE on the mitochondrial membrane potential (100×). (D, E, F) Relative expression levels of mRNA involved in mitochondrial biogenesis markers. (G, H) RRTE reduced intracellular ALT and AST content. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 VS Group Control; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 VS Group Model.

Lipid disorders can cause cellular damage. Aminotransferase release is a major indicator of hepatocellular carcinoma damage. To assess the effect of the intervention on cell damage, we established a negative control group (RRTE-Y) at the same time to facilitate the assessment of the effects of the inducer and RRTE on cells. Results showed that FFA intervention significantly increased intracellular ALT and AST levels, whereas RRTE intervention significantly decreased intracellular ALT and AST levels (Fig. 2G and H). Furthermore, RRTE intervention alone did not cause cell damage.

These results suggest that RRTE restores cellular mitochondrial function and attenuates cellular damage caused by lipid disorders by reducing intracellular ROS, reversing MMP, and increasing the mRNA expression of mitochondrial biogenesis markers.

Effects of RRTE on lipid metabolism

To further investigate the effects of RRTE on lipid metabolism, we measured the expression levels of genes associated with lipid metabolism using RT-qPCR. The results indicated that RRTE was able to significantly inhibit the expression of C/EBPα and suppress lipogenesis (Fig. 3A). Low and medium doses of RRTE did not reduce the expression levels of the lipid accumulation-related genes, SREBP-1c, FAS, and ACC in FFA-induced cells, whereas high doses of RRTE significantly reduced them (Fig. 3B–D). Low and medium doses of RRTE significantly increased the expression of HSL and ATGL, and promoted lipolysis; however, high doses of RRTE did not appear to have any effect (Fig. 3E and F). These findings implied that RRTE played a significant role in improving lipid metabolism in HepG2 cells. In our previous experiments, we discovered that RRTE effectively diminished intracellular lipid accumulation. However, RT-qPCR results indicated that distinct doses of RRTE exerted lipid-lowering effects through disparate mechanisms, potentially attributable to the varying doses of RRTE comprising disparate quantities of the active component. Consequently, it is imperative to undertake effective screening and validation of lipid-lowering components.

Effects of RRTE on lipid metabolism. (A) Relative expression levels of mRNA involved in adipogenesis. (B, C, D) Relative expression levels of mRNA involved in lipid accumulation. (E, F) Relative expression levels of mRNA involved in lipolysis. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 VS Group Control; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 VS Group Model.

Network Pharmacology analysis

To better understand the potential components and mechanisms underlying RRTE lipid-lowering effects, a network pharmacology study was conducted. In the previous study of Li16, we found that RRTE contained 72 substances. Based on this, we further screened 27 substances for active compounds (Supplementary Table S3). In total, 454 potential targets of the active compounds were identified in the Swiss Target Prediction database. We then collected 1634 obesity targets from three different databases: GeneCards, OMIM, and DisGeNET (Fig. 4A). Among them, 167 overlapping targets of RRTE in obesity were identified (Fig. 4B). These 167 targets were predicted to be important for the action of RRTE in obesity. Overlapping targets were imported into the STRING website to construct the PPI network (Fig. 4C). The PPI network was then imported into Cytoscape to obtain the targets sorted by degree (Fig. 4D). Subsequently, the core targets were initially screened by Degree, Eigenvector, LAC, Betweenness, Closeness, and Network, all being greater than the median, and the core targets were identified according to the degree being greater than the two-fold median19 (Fig. 4E). The results showed that AKT1, PPARG, ESR1, SRC, STAT3, EGFR, HIF1A, BCL2, PTGS2, MMP9, and PPARA may be the core targets of RRTE action in obesity.

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed on the above 167 targets, and the top 20 were visualized (Fig. 5A and B). The study showed that the biological processes include response to hormone, cellular response to lipid and so on, the cellular components included receptor complex, dendrite, membrane raft, and the like, the molecular functions involving nuclear receptor activity, phosphotransferase activity and so on. In addition, KEGG analysis showed that PI3K-Akt and PPAR signaling pathway may be potential regulatory pathways.

To attain a more thorough understanding of the intricate relationships among components, targets, pathways, and diseases, an integrated regulatory network diagram was created (Fig. 5C). Naringenin chalcone, ethyl caffeate, caffeic acid, tryptophan, L-tryptophan, L-tyrosine, L-glutamic acid, p-coumaric acid, 3-phenyllactic acid, meglutol, and D-(+)-malic acid may be potential components that exert lipid-lowering effects in RRTE.

These results suggest the potential components of the presence of naringenin chalcone, ethyl caffeate, caffeic acid, tryptophan, L-tryptophan, L-tyrosine, L-glutamic acid, p-coumaric acid, 3-phenyllactic acid, meglutol, and D-(+)-malic acid. The PI3K-Akt and PPAR signaling pathways are potential pathways.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking was performed to identify the potential components and targets of RRTE that exert lipid-lowering effects. KEGG analysis indicated that the PI3K-Akt and PPAR signaling may be potential target pathways. By combining the pathway targets with core targets, AKT1, PPARG, and PPARA were selected as receptors. Eleven components, including five amino acids, three organic acids, two polyphenols, and one flavonoid, were screened in an integrated regulatory network diagram and used as ligands. The receptors and ligands were docked separately, their affinities were calculated (Table 1), and the binding processes of the flavonoid and polyphenol ligands to the receptors were visualized (Fig. 6). An affinity value of less than − 5 kcal/mol indicates that the ligand molecule has a desirable binding affinity19. The findings indicated that all affinity values were less than − 5 kcal/mol, except for D-(+)-malic acid, L-glutamic acid with AKT1, and meglutol with PPARG. This suggests that these 11 components, except D-(+)-malic acid, L-glutamic acid, and meglutol, are likely responsible for the lipid-lowering effect of RRTE.

Molecular docking analysis. (A) Naringenin chalcone and AKT1 (PDB ID: 7NH5). (B) Ethyl caffeate and AKT1. (C) p-Coumaric acid and AKT1. (D) Naringenin chalcone and PPARA (PDB ID: 7E5H). (E) Ethyl caffeate and PPARA. (F) p-Coumaric acid and PPARA. (G) Naringenin chalcone and PPARG (PDB ID: 2P4Y). (H) Ethyl caffeate and PPARG. (I) p-Coumaric acid and PPARG.

Screening of lipid-lowering components in RRTE

By synthesizing the integrated regulation network diagram and molecular docking results, we preliminarily concluded that naringenin chalcone, ethyl caffeate, caffeic acid, tryptophan, L-tryptophan, L-tyrosine, p-coumaric acid, and 3-phenyllactic acid may underlie the lipid-lowering effect of RRTE. We then searched for studies in which the above components were previously associated with lipid-lowering effects and ultimately found that p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate may play an important role in the lipid-lowering effect of RRTE. To explore the reliability of these results, we performed GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate in obesity. The results showed 14 and 31 overlapping targets of p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate, respectively, in obesity (Fig. 7A and B). GO analysis of the overlapping targets showed that the biological processes of both components were predominantly enriched in cellular responses to lipids (Fig. 7C and D). KEGG analysis of ethyl caffeate also revealed enrichment of the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (Fig. 7E and F). These results indicated that these two components exert lipid-lowering effects.

Network pharmacology analysis of p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate. (A, B) Venn diagram analysis of targets of p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate with obesity. (C, D) GO analysis of targets of p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate targeting obesity. (E, F) KEGG analysis of targets of p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate targeting obesity.

Validation of network pharmacology

In vitro experiments showed that RRTE attenuated the cellular damage and dysfunction caused by lipid metabolism disorders and reduced intracellular lipid accumulation. Network pharmacology and molecular docking were used to investigate the possible components and pathways involved in the effects of RRTE. In vitro experiments were conducted to validate these components and pathways.

Lipid-lowering components validation

After screening p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate, their efficacy and content was further validated. Initially, the concentrations of these two compounds in RRTE were quantified via HPLC with the standard curve (Fig. 8). The analysis revealed that RRTE contained p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate at concentrations of 811.96 µg/g and 24.50 µg/g, respectively (Table 2). Subsequently, the cytotoxic effects of both compounds were evaluated. The results showed that p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate did not reduce HepG2 cell viability at concentrations of 1 and 0.4 mM/L, respectively (Fig. 9A and B). This indicates that p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate were not toxic to HepG2 cells. Therefore, 0.5 mM/L p-coumaric and 0.1 mM/L ethyl caffeate were further utilized to investigate their effects on lipid metabolism disorders in HepG2 cells.

Effects of p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate on lipid accumulation. (A, B) Effect of p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate on HepG2 cells viability(* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 VS Group 0). (C) intracellular lipid droplets in HepG2 cells stained with Oil Red O (100×). (D) Quantitative analysis of Oil Red O staining. (E, F) p-Coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate reduced intracellular triglyceride and triglyceride content. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 VS Group Control; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 VS Group Model.

Oil Red O staining showed that treatment of FFA-induced HepG2 cells with p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate reduced intracellular lipid accumulation (Fig. 9C and D). Simultaneously, p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate treatment significantly decreased the elevation of intracellular TG and TC levels caused by FFA induction (Fig. 9E and F). These results suggested that p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate attenuated lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells.

In addition, compared with FFA-induced HepG2 cells, they showed reduced intracellular ROS levels, while restoring the cellular mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 10A–C). They increased mRNA levels of AMPK, SIRT1, and PGC-1α, which are related to mitochondrial functions (Fig. 10D–F). These results demonstrate that p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate can attenuate ROS damage caused by lipid metabolism disorders and gradually restore mitochondrial function in HepG2 cells.

Protective effects of p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate on mitochondrial function. (A, B) p-Coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate reduced intracellular ROS levels. (C) Effect of p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate on the mitochondrial membrane potential (100×). (D, E, F) Relative expression levels of mRNA involved in mitochondrial biogenesis markers. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 VS Group Control; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 VS Group Model.

Ethyl caffeate and p-coumaric acid are the lipid-lowering components of RRTE.

Pathways validation

Quantitative real-time PCR was used to verify whether p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate affected the PPAR and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways. Results showed that RRTE, p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate increased the expression levels of PPARα, CPT1, and ACOX1 in the PPAR signaling pathway; and PI3K, AKT in the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in FFA-induced HepG2 cells (Fig. 11), suggesting that RRTE and its lipid-lowering components may modulate cellular steatosis via the PI3K-Akt and PPAR signaling pathways in vitro.

Analysis of mRNA expression levels of core genes of PPAR signaling pathway and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. (A, B, C) Relative expression levels of mRNA involved in PPAR signaling pathway by RRTE intervention. (D, E, F) Relative expression levels of mRNA involved in PPAR signaling pathway by p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate intervention. (G, H) Relative expression levels of mRNA involved in PI3K-Akt signaling pathway by RRTE intervention. (I, J) Relative expression levels of mRNA involved in PI3K-Akt signaling pathway by p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate intervention. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 VS Group Control; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 VS Group Model.

Discussion

Obesity is an unsolved problem with multiple complex causes that have reached epidemic proportions worldwide. Current clinical medications for obesity treatment can cause serious side effects, including gastrointestinal flatulence and diarrhea20. Thus, a growing number of individuals are searching for natural, plant-based products with anti-obesity effects. As a natural fruit poised for development, RRT contains a diverse array of active components, is safe with no side effects, and has a long-standing tradition of medicinal use in Southwest, China. In the present study, we prepared RRTE, which effectively concentrated the active components of RRT16, and further explored its possible anti-obesity mechanism and components.

Disorders in lipid metabolism and abnormal lipid accumulation are the primary characteristics of obesity21. The liver, as the body’s largest metabolic organ, plays a pivotal role in lipid metabolism, which can regulate lipid metabolism by modulating lipolysis, lipogenesis and transport22,23. Lipid metabolic dysregulation caused by obesity leads to hepatic steatosis and hepatocellular damage, while hepatic steatosis exacerbates dyslipidemia11,24. Therefore, we used an FFA-treated HepG2 cell model to explore the lipid-lowering effects of RRTE. Lipogenesis and lipolysis are the two critical regulatory mechanisms involved in lipid metabolism. C/EBPα, SREBP-1c, FAS, and ACC play important roles in lipogenesis. C/EBPα, a member of the C/EBP family of transcription factors, is essential for transcriptional regulation in metabolic organs and serves as a key regulator of lipid metabolism25. It has also been implicated in the regulation of lipogenesis genes26. Meanwhile, SREBP-1c is another important transcription factor for Lipogenesis that exacerbating lipid droplet formation, regulating the expression and activity of FAS and ACC, and influencing lipid accumulation27,28. ATGL and HSL are the main rate-determining enzymes associated with lipolysis29. Our findings indicated that RRTE markedly diminished the accumulation of lipids within cells, while concurrently reducing the expression of C/EBPα and inhibiting lipogenesis. Meanwhile, RRTE in the high-dose group decreased the expression of SREBP-1c, FAS, and ACC, while RRTE in the low- and medium-dose groups enhanced the expression of HSL and ATGL, which may be associated with variations in the composition of the substances present in the different dose groups.

Obesity can be viewed as a state of low-grade chronic inflammation. Mechanisms related to inflammation in obesity may lead to increased ROS levels, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction30,31. Mitochondrial function is tightly regulated by mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy, and adapts to cellular energy requirements of the cell32. AMPK, SIRT1, and PGC-1α serve as the primary regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis processes33,34,35. The study shows that PGC-1α participates in the transcriptional control of TFAM, thus regulating mitochondrial biogenesis36. SIRT1, a nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent deacetylase, can promote mitochondrial biogenesis by activating PGC-1α37,38. AMPK, the main energy sensor in cells, promotes SIRT1 and PGC-1α activity34,39. Improvements in mitochondrial biogenesis markers restore mitochondrial function and promote energy metabolism. In this study, RRTE reduced intracellular ROS, reversed MMP, and modulated the levels of mRNA expression for AMPK, SIRT1, and PGC-1α in the cells, restoring mitochondrial function.

Network pharmacology is an ideal tool for studying the pathways and active components of natural compounds for the treatment of diseases. In this study, two components of RRTE that may exert lipid-lowering effects were identified: p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate. As is widely recognized, ethyl caffeate and p-coumaric acid both belong to polyphenol, having lipid-lowering potential. Current literature suggests that dietary polyphenols can inhibit adipocyte differentiation, lipid accumulation, and reduce oxidative stress; simultaneously, they can also promote lipolysis and fatty acid β-oxidation40. Additionally, Huang et al. found that fermented quinoa polyphenols demonstrated an efficient anti-obesity effect through the AMPK/PPARα/CPT1 pathway41. Xue et al. found that p-coumaric acid regulates thermogenesis and lipid metabolism via mTORC142. Seo et al. found that peanut sprouts enriched with p-coumaric acid attenuated obesity induced by a high-fat diet and inhibited inflammation by activating mitochondrial function to promote browning43. Xie et al. also demonstrated that p-coumaric acid regulates liver fat metabolism by upregulating CPT1 expression44. This suggests that p-coumaric acid and polyphenols have excellent anti-obesity effects. The results of our study are consistent with these results. In the present study, we found that p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate reduced lipid accumulation in cells, decreased ROS levels, increased MMP and the expression of mitochondrial biogenesis markers, and restored mitochondrial function, consistent with the effects of RRTE. This further confirmed that p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate were lipid-lowering components of RRTE.

The regulation of obesity and lipid metabolism involves multiple complex pathways45,46. Our study revealed that RRTE and its active components are related to the PI3K-Akt and PPAR signaling pathways. These two signaling pathways are strongly associated with lipid metabolism. The PI3K-Akt signaling pathway exhibits two distinct mechanisms in the modulation of lipid metabolism. Inhibition of the PI3K-Akt pathway regulates the expression of G6PC and FOXO1 in hepatocytes, thereby promoting glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, which in turn affects lipid metabolism47,48. Meanwhile, the PI3K-Akt pathway regulates lipogenesis by inhibiting SREBP-1c and enhancing hepatic LDLR protein expression49. Additionally, activation of the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway is linked to lipid metabolism50. Elevation of PI3K-Akt pathway-related proteins regulates PPARγ levels to modulate the WAT browning process51. When the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway is activated, it can promote adipocyte browning and increase the expression of UCP-1, PGC-1α, and PRDM1652,53. This suggests that the pathway activation is closely linked to energy expenditure. As a major organelle involved in energy metabolism, mitochondria are inextricably linked to the activated PI3K- Akt pathway54. It also regulates mitochondrial function by decreasing oxidation stress55. Our experiments revealed that RRTE and its lipid-lowering components, p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate, activated the PI3K-Akt pathway, restored mitochondrial function, and lowered lipid levels.

PPARα, PPARγ and PPARδ are three isoforms in the family of PPARs in the PPAR signaling pathway56,57. Among the PPAR isoforms, PPARα and PPARγ frequently regarded as closely related to lipid metabolism58. Of the two, PPARα predominantly stimulates mitochondrial function and involves in fatty acid β-oxidation in liver, whereas PPARγ is associated with the fat synthesis and storage59,60. In our experiments, we found that RRTE had little effect on fat synthesis. Thus, we analyzed its effect on PPARα. Results showed RRTE, p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate both restored PPARα expression in cells. This suggests that its lipid-lowering function is inextricably linked to fatty acid β-oxidation. CPTI and ACOX1 play important roles in fatty acid β-oxidation as downstream of PPARα. By catalyzing the conversion of fatty acyl-CoA into fatty acylcarnitine in mitochondria, CPT1 governs the β-oxidation of fatty acids61. ACOX1 serves as the first enzyme in the fatty acid β-oxidation pathway and facilitates the desaturation of acyl-CoA into a 2-trans-enyl group62. We also found that RRTE, p-coumaric acid, and ethyl caffeate increased CPT1 and ACOX1 expression to promote fatty acid oxidation.

In conclusion, this study confirms that RRTE has a lipid-lowering effect on FFA-induced HepG2 cells, possesses anti-obesity potential, and that ethyl caffeate and p-coumaric acid are the active components in its action. Different doses of RRTE can reduce intracellular Lipid accumulation by inhibiting lipogenesis or promoting lipolysis. It also reduces lipotoxicity caused by lipid accumulation, reduces ROS production, restores cellular mitochondrial function, and enhances energy metabolism. However, network pharmacology analysis, showed that the lipid-lowering and anti-obesity effects of RRTE were closely related to the PI3K-Akt and PPAR signaling pathways. RRTE activated the expression of PI3K and AKT, which increased the expression of AMPK and further restored mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, while activated AMPK promoted the expression of PPARα and further enhanced fatty acid β-oxidation (Fig. 12). The current study is still limited in scope, having only explored the lipid-lowering effect of RRTE at the cellular level, with a lack of supporting data from animal experiments. In future studies, we intend to conduct further supplementary research.

Conclusion

Obesity remains an unsolved problem, and the development of food-derived components and products for weight reduction is of great significance. We explored the lipid-lowering effects of RRTE and the active components. Our research shows that RRTE can lower lipid levels in HepG2 cells, and p-coumaric acid and ethyl caffeate may be crucial to this effect. It controls the expression of genes associated with lipid metabolism and restores mitochondrial function in HepG2 cells, which may involve the PI3K/AKT/AMPK/PPAR signaling pathway. Our study enhances the understanding of the anti-obesity mechanism of RRTE and can serve as a basis for further research.

Data availability

Data are contained within the article.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- ACOX1:

-

acyl-CoA oxidase 1

- AKT:

-

protein kinase B

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- AMPK:

-

Adenosine 5′-monophosphate activated protein kinase

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- ATGL:

-

adipose triglyceride lipase

- C/EBPα:

-

CCAAT enhancer binding proteinα

- CPT1:

-

carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1

- FAS:

-

fatty acid synthase

- FFA:

-

free fatty acid

- HSL:

-

hormone-sensitive lipase

- PGC-1α:

-

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha

- PI3K:

-

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PPARα:

-

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorα

- SIRT1:

-

silent information regulator sirtuin 1

- SREBP-1c:

-

sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c

- TC:

-

total cholesterol

- TG:

-

triglyceride

References

Lingvay, I. et al. Obesity in adults. Lancet404(10456), 972–987 (2024).

Lauby-Secretan, B. et al. Body fatness and cancer–Viewpoint of the IARC working group. N. Engl. J. Med.375(8), 794–798 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Trends and disparities in diabetes and prediabetes among adults in the United States, 1999–2018. Public Health214, 163–170 (2023).

Perdomo, C. M. et al. Contemporary medical, device, and surgical therapies for obesity in adults. Lancet401(10382), 1116–1130 (2023).

Li, B. et al. Assessment of quality differences between wild and cultivated fruits of Rosa roxburghii Tratt. LWT202, 116300 (2024).

Liu, W. et al. Structure and antitumor activity of a polysaccharide from Rosa roxburghii. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 273, 132807 (2024).

Li, B. et al. Effects of probiotics on antioxidant activity, flavor compounds and sensory evaluation of Rosa roxburghii Tratt. LWT179, 114664 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Effect of Rosa roxburghii fruit on blood lipid levels: A systematic review based on human and animal studies. Int. J. Food Prop.25(1), 549–559 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Effect and correlation of Rosa roxburghii Tratt fruit vinegar on obesity, dyslipidemia and intestinal microbiota disorder in high-fat diet mice. Foods 11(24), 4108 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. A polysaccharide from Rosa roxburghii Tratt fruit attenuates high-fat diet-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction and inflammation in mice by modulating the gut microbiota. Food Funct.13(2), 530–547 (2022).

Ni, H.-Y. et al. Seed oil of Rosa roxburghii Tratt against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in vivo and in vitro through PPARα/PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Phytomedicine98, 153919 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Network Pharmacology approaches for research of traditional Chinese medicines. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 21 (5), 323–332 (2023).

Shawky, E. Prediction of potential cancer-related molecular targets of North African plants constituents using network pharmacology-based analysis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 238, 111826 (2019).

He, Y. et al. Exploration of the underlying mechanism of Astragaloside III in attenuating immunosuppression via network pharmacology and vitro/vivo pharmacological validation. J. Ethnopharmacol.330, 118235 (2024).

Noor, F. et al. Machine learning for synergistic network pharmacology: a comprehensive overview. Brief. Bioinform. 24(3), bbad120 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Rosa roxburghii Tratt fruit extract prevents DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice by modulating the gut microbiota and the IL-17 signaling pathway. Nutrient 15(21), 4560 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. The flavonoids extract from Okra flowers protects against DSS-induced colitis via regulating NF-κB signaling pathway and gut microbiota. J. Funct. Foods. 99, 105335 (2022).

Huang, H. et al. Untargeted metabolomics reveals the regulatory effect of Geniposidic acid on lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells and Caenorhabditis elegans and validation in hyperlipidemic hamsters. Phytomedicine125, 155295 (2024).

Kang, Y. H. et al. Effects of Rosa roxburghii Tratt on ulcerative colitis: an integrated analysis of network Pharmacology and experimental validation. Am. J. Chin. Med. 51 (6), 1477–1499 (2023).

Rajamanikandan, V. P. V. & Perumal, S. Morin inhibits the activity of pancreatic lipase and adipogenesis. Eur. J. Pharmacol.977, 176705 (2024).

Sousa, D. et al. Adipose tissue-liver cross-talk: A route to hepatic dysfunction in pregnant women with obesity. Biosci. Rep.44(8), BSR20231679 (2024).

Lundbom, J. Adipose tissue and liver. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 124 (1), 162–167 (2018).

Hodson, L. & Gunn, P. J. The regulation of hepatic fatty acid synthesis and partitioning: The effect of nutritional state. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol.15(12), 689–700 (2019).

Cui, W. et al. Effects of grape peel phenolics on lipid accumulation in sodium palmitate-treated HepG2 cells. J. Funct. Foods112, 105923 (2024).

Schrem, H., Klempnauer, J. & Borlak, J. Liver-enriched transcription factors in liver function and development. Part II: the c/ebps and D site-binding protein in cell cycle control, carcinogenesis, circadian gene regulation, liver regeneration, apoptosis, and liver-specific gene regulation. Pharmacol. Rev. 56 (2), 291–330 (2004).

Bauer, R. C. et al. Tribbles-1 regulates hepatic lipogenesis through posttranscriptional regulation of C/EBPα. J. Clin. Invest.125(10), 3809–3818 (2015).

Shimano, H. & Sato, R. SREBP-regulated lipid metabolism: Convergent physiology - divergent pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol.13(12), 710–730 (2017).

Han, L. Q. et al. Overexpression of SREBF chaperone (SCAP) enhances nuclear SREBP1 translocation to upregulate fatty acid synthase (FASN) gene expression in bovine mammary epithelial cells. J. Dairy. Sci. 101 (7), 6523–6531 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Creatine ameliorates high-fat diet-induced obesity by regulation of lipolysis and lipophagy in brown adipose tissue and liver. Biochimie.209, 85–94 (2023).

Bondia-Pons, I., Ryan, L. & Martinez, J. A. Oxidative stress and inflammation interactions in human obesity. J. Physiol. Biochem.68(4), 701–711 (2012).

de Mello, A. H. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity. Life Sci. 192, 26–32 (2018).

Liu, L. et al. Crosstalk between mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis. J. Biomed. Sci.30(1), 86 (2023).

Scarpulla, R. C. Nuclear activators and coactivators in mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta.1576(1–2), 1–14 (2002).

Jäger, S. et al. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 104 (29), 12017–12022 (2007).

Moore, M. P. et al. Compromised hepatic mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and reduced markers of mitochondrial turnover in human NAFLD. Hepatology76(5), 1452–1465 (2022).

Santos, J. M. et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis and the development of diabetic retinopathy. Free Radic Biol. Med. 51 (10), 1849–1860 (2011).

Pillarisetti, S. A review of Sirt1 and Sirt1 modulators in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Recent. Pat. Cardiovasc. Drug Discov. 3 (3), 156–164 (2008).

Koh, J. H. & Kim, J. Y. Role of PGC-1α in the mitochondrial NAD(+) pool in metabolic diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(9), 4558 (2021).

Cantó, C. et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD + metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature458(7241), 1056–1060 (2009).

Cao, Y. et al. Targeting mTOR signaling by dietary polyphenols in obesity prevention. Nutrients14(23), 5171 (2022).

Huang, K. et al. Benefits of Monascus anka solid-state fermentation for quinoa polyphenol bioaccessibility and the anti-obesity effect linked with gut microbiota. Food Funct.15(4), 2208–2220 (2024).

Han, X. et al. p-Coumaric acid prevents obesity via activating thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue mediated by mTORC1-RPS6. FASEB J.34(6), 7810–7824 (2020).

Seo, S. H. et al. Peanut sprout rich in p-coumaric acid ameliorates obesity and lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and the inhibition of browning in adipocytes via mitochondrial activation. Food Funct.12(12), 5361–5374 (2021).

Xie, W. et al. Ananas comosus L. Leaf Phenols and p-Coumaric Acid Regulate Liver Fat Metabolism by Upregulating CPT-1 Expression. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014, 903258 (2014).

Ameer, F. et al. De novo lipogenesis in health and disease. Metabolism63(7), 895–902 (2014).

Sanders, F. W. & Griffin, J. L. De novo lipogenesis in the liver in health and disease: More than just a shunting yard for glucose. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc.91(2), 452–468 (2016).

Li, S. et al. Olanzapine Induces Adipogenesis and Glucose Uptake by Activating Glycolysis and Synergizing with the PI3K-AKT Pathway. Curr Neuropharmacol. 23(4), 412-425 (2024).

Pitaloka, D. M. I. et al. Glutamine administration promotes hepatic glucose homeostasis through regulating the PI3K/Akt pathway in high-fat diet-induced obese mice with limb ischemia. Nutr. Res.68, 45–53 (2019).

Li, X. et al. SREBP-1c overexpression induces triglycerides accumulation through increasing lipid synthesis and decreasing lipid oxidation and VLDL assembly in bovine hepatocytes. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 143, 174–182 (2014).

Wu, X. et al. Parboiled rice extracts ameliorate oleic acid-induced steatosis of HepG2 cell and its molecular mechanism [J]. J. Funct. Foods. 110, 105853 (2023).

Lu, Y. et al. Downregulation of osteopontin inhibits Browning of white adipose tissues through PI3K-AKT pathway in C57BL / 6 mice [J]. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 866, 172822 (2020).

Chen, F. et al. Leaf extract of Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt promotes adipocyte browning via the p38 MAPK pathway and PI3K-AKT pathway. Nutrients15(6), 1487 (2023).

Zhong, X. J. et al. Osteopontin-induced brown adipogenesis from white preadipocytes through a PI3K-AKT dependent signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 459 (3), 553–559 (2015).

Paliwal, S. et al. Mitochondrial transfer restores impaired liver functions by AMPK/ mTOR/PI3K-AKT pathways in metabolic syndrome. Life Sci. 332, 122116 (2023).

Abu Bakar, M. H. & Tan, J. S. Improvement of mitochondrial function by Celastrol in palmitate-treated C2C12 myotubes via activation of PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 93, 903–912 (2017).

Andrééva-Gatéva, P. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptors ppars: their role in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Ann. Biol. Clin. (Paris). 61 (3), 295–303 (2003).

Evans, R. M., Barish, G. D. & Wang, Y. X. PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nat. Med.10(4), 355–361 (2004).

Li, Y. et al. Quinoa peptides alleviate obesity in mice induced by a High-Fat diet via regulating of the PPAR-α/γ signaling pathway and gut microbiota [J]. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 67 (22), e2300258 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. PPARs as metabolic regulators in the liver: Lessons from liver-specific PPAR-null mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(6), 2061 (2020).

Varga, T., Czimmerer, Z. & Nagy, L. PPARs are a unique set of fatty acid regulated transcription factors controlling both lipid metabolism and inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta.1812(8), 1007–1022 (2011).

Wang, M. et al. Effect of Quercetin on lipids metabolism through modulating the gut microbial and AMPK/PPAR signaling pathway in broilers. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.9, 616219 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Effects of early florfenicol exposure on glutathione signaling pathway and PPAR signaling pathway in chick liver. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 237, 113529 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We Sincerely thank the Public Health and Preventive Medicine Experiment Platform of West China School of Public Health, Sichuan University, and Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding

The work was supported by no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yihan Ling: conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, and writing-original draft; Wenxi Wang: investigation, methodology and writing-review and editing; Xingjie Li: investigation and methodology; Xiaomeng Wang, investigation and visualization; Shuwen Zhang, methodology; Shaolin Huang, investigation; Heting Zhou, methodology; Lijun Peng, supervision; Wenya Yin, conceptualization, and supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ling, Y., Wang, W., Li, X. et al. Rosa roxburghii Tratt fruit extract ameliorate free fatty acid induced steatosis in HepG2 cells through activating PI3K-Akt and PPAR pathways. Sci Rep 15, 26169 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12126-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12126-z