Abstract

Bacterial biofilm development plays a crucial role in causing serious health concerns in the medical sector. The adhesion of germs on living and non-living surfaces can lead to damage as well as diseases in humans, and other animals. To address this problem, researchers focus exclusively on bacteriophage therapy. In the present study, lytic phage with 1010 PFU/mL was isolated from hospital sewage samples by targeting Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922). The morphological study of the isolated phage was examined under high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) by using 2% of uranyl acetate as a negative staining, which revealed that the isolated phage belonged to the Myoviridae family. Bacterial turbidity assay showed reduced optical density (OD) in 0.01 multiplicity of infection (MOI) and no growth in 0.1 and 1.0 MOI phage concentration which was compared with control (without phage-treated E. coli cells). The phage-host interaction was investigated using an HR-TEM after treating the phage for 30 min, which showed the lytic cycle of the phage. Further, the E. coli biofilm was assessed using a microplate reader after 24 and 48 h on 96 titer plates with crystal violet staining to confirm the inhibition efficiency of phage-treated biofilm quantitatively (83%). Then the compound and fluorescence microscopy were used for qualitative measurement of inhibition activity. Further, the biofilm formation of E. coli on a coverslip surface was analysed using scanning electron microscopy, comparing samples treated with 0.1 MOI of phage to untreated controls. About 10% of countable cells only present over the phage-treated surface (90% of biofilm inhibition). The outcome of this study revealed that phage treatment effectively suppressed the E. coli biofilm development, and it can be used as a sustainable and eco-friendly approach for the control of biofilm formation on surfaces specifically in hospital environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Escherichia coli, a gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium, poses significant public health challenges due to its ability to form biofilms1. Biofilm formation enhances resistance to antibiotics and host immune responses, making infections more persistent and difficult to treat2. These biofilms can adhere to internal organs, such as the urinary tract or intestines, leading to chronic and recurring infections3. The presence of these biofilms not only complicates treatment but also contributes to the development of antibiotic resistance within bacterial populations.

A recent analysis of antimicrobial resistance trends in E. coli isolates from midstream urine samples over the period of 2000–2019 revealed increased resistance rates to most antibiotics, except for carbapenems. In contrast, resistance to fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin showed slight decline. Among 30,955 isolates, a study reported the significant rise in extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing and multidrug-resistant strains, particularly in older patients4,5. Additionally, in 2020, one in five clinical E. coli isolates demonstrated reduced susceptibility to commonly used antibiotics such as ampicillin, co-trimoxazole, and fluoroquinolone6,7. This high resistance level, especially to third-generation cephalosporins commonly used as a first-line treatment poses a substantial challenge for healthcare providers8,9. These trends underscore the urgent need for continued surveillance and the development of alternative therapeutic approaches.

In response, researchers are exploring new treatment strategies, including combined antibiotic regimens and natural compounds derived from plant and animals10. Among the most promising alternatives is bacteriophage therapy. Phages are viruses that specifically target and lyse bacteria, offer a targeted approach to combat antibiotics resistance infections without disturbing host microbiota11,12. For example, a study by Lee and Park13 demonstrated that two isolated phages (BECP2 and BECP6) effectively inhibited biofilm formation of E. coli O157:H7 on the surfaces such as glass wool, microtiter well plate and stainless steel. Foodborne outbreak linked to E. coli remain global concern, in 2011 outbreak in Germany was caused by E. coli O104:H4, which affected over 3800 individuals, 90% of whom were adults, with two-thirds being females14.

Clinical observations have shown that some patients experience substantial improvement following phage therapy, further supporting its potential as a viable alternative to antibiotics15,16. In parallel, studies have examined the effects of sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (sub-MICs) of antibiotics. Dong et al.17 found that sub-MICs of ciprofloxacin (CIP) on biofilm development and virulence factors in clinical isolates of E. coli. The findings indicated that the sub-MICs of CIP constituted one-fourth of the MIC. CIP significantly inhibited biofilm formation in both E. coli clinical isolates and the reference strain E. coli ATCC 25922 at these concentrations (p < 0.01). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis revealed significant changes in the biofilm structure after treatment with sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations of ciprofloxacin. The expression of virulence genes (fim, usp, and iron) and biofilm-related genes from the pgaABCD locus was significantly reduced. The findings demonstrated that a 24 h treatment with sub-MICs of CIP effectively inhibited biofilm formation and suppressed the expression of both virulence and biofilm-associated genes in E. coli.

The present study focuses on the isolation and characterization of a bacteriophage specifically targeting the biofilm-forming E. coli strain ATCC 25922. The phage was evaluated for its lytic activity, biofilm disruption efficiency, and structural characteristics. Our findings demonstrate that this bacteriophage is highly effective in reducing E. coli biofilms, supporting its potential as an alternative therapeutic agent. The objective of this study is to explore bacteriophage therapy as a targeted strategy to control biofilm-associated E. coli infections and contribute to the ongoing effort to combat antimicrobial resistance.

Materials and methods

Bacterial culture

The E. coli ATCC 25922 strain was obtained from the Department of Medical Microbiology at SRM Medical Hospital and Research, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur campus. It was propagated and maintained in Luria-Bertani agar and broth. For long-term preservation, 500 µL of sterilized 20% glycerol was mixed with 500 µL of E. coli culture (1.0 OD in 600 nm) and stored at −20 °C. Based on the ATCC accession number, whole genome data were assessed using the RAST Seed Viewer online tool. The genBank accession number of E. coli (ATCC 25922) was taken from a previous study18.

Bacteriophage isolation and enumeration

For phage isolation, a previously established protocol was followed19,20. The bacterial strain was cultured in LB media and incubated for 12 h. Phage isolation was performed using ambient samples and sewage samples obtained from local medical centers (12°49’21.7” North and 80°03’01.0” East). These samples were heavily contaminated with various organic (e.g., fats and carbohydrates), and inorganic substances (e.g., nitrogen from urine, protein), heavy metals, organic solvents from pharmaceuticals and personal care products. These components can promote the proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms, thereby favoring the presence of phages targeting them.

The samples were centrifuged at 8500 rpm at 4 °C and the supernatant was filtered via 0.2 μm syringe filters to exclude bacterial contaminants. Subsequently, 100 µL of host (0.8 OD E. coli) and 300 µL of the filtered sample were used for phage isolation via the double-layer agar plate method (DLA). Briefly, the filtered sample and host were added into a sterile test tube, followed by 5 mL of soft agar (LB with 0.5% agar). The mixture was poured over a pre-prepared hard agar plate (LB with 1.5% agar). Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. A control plate containing only the E. coli strain without the filtered sample was also prepared21.

Phage presence was confirmed by the appearance of plaques. Plaques were collected using sterile tips and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. After incubation, the culture was centrifuged at 8500 rpm at 4 °C, and the supernatant containing isolated phages was used for efficacy of plating (EOP) determination using the DLA method22. Figure 1 shows the protocol used for the measurement of EOP for isolated phage.

Schematic illustration of phage titration protocol for EOP determination; For this, 990 µL of LB broth with 10 µL of isolated phage suspension were mixed to achieve a 10−2 titer (dilution factor); Further serial dilutions were made up to 10−10, and DLA was performed to assess plaque formation across dilution factors.

Chloroform sensitivity test and phage concentration

To reduce the host contamination, phage stability in chloroform was assessed. For this, 1% chloroform was used during the time of phage lyophilization process23. A mixture of 500 µL of phage suspension and 500 µL of chloroform was incubated overnight at 37 °C. The sample was then used to measure EOP using DLA method24. To concentrate the phage, lyophilization was performed. The phage-chloroform mixture was treated with 1% sucrose as a stabilizer. The lyophilized phage was resuspended with SM buffer (10 mM Tris HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl and 68 mM CaCl2) which was used for subsequent characterization and antibiofilm studies25,26.

Phage morphology and host interaction analysis using electron microscope

To examine the morphology, 10 µL phage suspension was applied onto a copper-carbon grid and observed under a High-resolution transmission electron microscope (HR-TEM) at 200 kV (Make: JEOL, Model: JEM-2100 Plus, Japan), following the producer described by Lee et al.24. For the phage-host interaction analysis, the phage was introduced to a host with an optical density (OD) of 0.8 and incubated in a shaking incubator at 37 °C for 30 min1,27. Subsequently, the host cells were treated with a 4% of lutaraldehyde, centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and resuspended again in sterile 1x phosphate buffer saline (PBS). A 10 µL of suspension was then applied to a 250-mesh copper-carbon grid for TEM analysis as described above.

Growth kinetics Inhibition assay

Growth inhibition of E. coli at different multiplicity of infection (MOI) of phage concentration (MOI: 0.01, 0.1, and 1) was assessed in a 96-well microtiter plate28,29. Absorbance at 600 nm was measured at 60 min intervals over a 6 h of period, and at 12, 15, 18, 24, and 48 h using ELISA microplate reader. Well with host but no phage was served as control; SM buffer was used as the negative control. Results were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA.

Spectroscopic measurement of E. coli biofilm

After 30 min of incubation of E. coli in LB media (1:100) in 96 well plates, 100 µL of phage (at previously mentioned MOIs) was added to the wells for initial biofilm inhibition. Triplicate samples were incubated for 24 and 48 h. Absorbance at 570 nm was measured according to Ribeiro et al.30. For mature biofilm eradication, phage was added after 24 and 48 h of incubation. A volume of 100 µL of 105 PFU/mL phage was added to the wells, incubated for 60 min, and then washed with 1x PBS. The crystal violet assay protocol was repeated, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm31. SM buffer served as a negative control. All spectroscopic results were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05).

Microscopic assessment of E. coli biofilm

Qualitative biofilm analysis was conducted using sterile coverslips. A 5 mL mixture of LB broth (100:1) and E. coli (0.8 OD) was added to 6-well plate. 100 µL phage (at specific MOI) was added to the well (excluding control). At 60 min intervals, coverslips were removed from crystal violet staining to assess initial biofilm inhibition over 6 h32. The same procedure was used to assess mature biofilms at 24 and 48 h33,34. Coverslips were also stained with acridine orange for fluorescence microscopy and fixed with 4% glutaraldehyde for surface morphology analysis. Dehydration was done using different graded ethanol (60 to 100%), followed by Hi-Resolution Scanning Electron Microscope (HR-SEM) analysis (make: Thermoscientific. Model: Apreo S)35. After drying at room temperature, the surfaces were analyzed.

Result and discussion

Bacterial strain

The collected ATCC E. coli strain was used as the host for phage isolation. Crystal violet assay revealed that E. coli strain formed strong biofilms. Spectroscopic analysis showed OD values of 0.5 and 0.8 at 24 and 48 h, respectively. Additionally, whole genome data of E. coli ATCC 25922 were retrieved from a previous report18. For coding sequence analysis, the NCBI accession number CP009072 was used with the RAST Seed Viewer online tool36,37,38. The overall genome size of E. coli was 5,130,767 bp with a GC content of 50.4%. The genome of ATCC 25922 E. coli contains 5 prophage specific genes responsible for the phage capsid protein synthesis and co-activator genes (IbrA and IbrB) that encode immunoglobulin binding protein (Fig. 2). Numerous other genes associated with metabolism, growth and reproduction were also identified. Notably, a cluster of 26 coding sequences was related to toxin production and antibiotic resistance. In the biofilm-related pathways, 14 gene clusters were associated with motility and chemotaxis, while 5 genes were linked to adhesion.

Whole genomic analysis of E. coli strain ATCC 25922: Genes for prophage, antibiotics and toxin resistance are highlighted in the blue color; Prophage genes include phage capsid protein and IbrA/B; Additionally, genes confer resistance to heavy metal like mercury, zinc, copper, cobalt, and cadmium highlighted in blue color; Five adhesion genes pgaABCD operon responsible for the EPS polysaccharide production are also present. Virulence genes such as fim gene (for adhesion) usp (universal stress protein involves various cellular functions) were also detected. [RAST seed viewer online: https://rast.nmpdr.org/seedviewer.cgi].

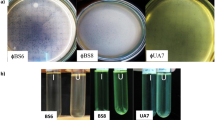

Isolation, enumeration, and morphological characterization of phage

A lytic phage was isolated from a sewage sample collected from hospital effluent. The plaques were small (1.5 mm in diameter) with clear halo. Plaque assay indicates a phage titer of approximately 107 PFU/mL. The phage resistance to chloroform and was concentrated using freeze-drying (lyophilization). After lyophilization, the phage titer increased to 1010 PFU/mL as shown in Fig. 3a – c. Spot assay shown in Fig. 3d indicates a 10 µL of phage suspension formed a 13 mm lytic zone.

HR-TEM observations (Fig. 3e and f) confirmed the phage belonged to the Caudovirales order and Myoviridae family according to International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses standards39with an icosahedron head (76 ± 5 nm) and a non-contractile tail (128 ± 5 nm). Smaller virus-like particles (VLP) of 35 ± 5 nm were also observed40.

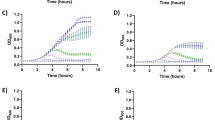

Growth kinetics Inhibition assay

The growth kinetics were observed for the phage-infected E. coli, as illustrated in Fig. 4. These continuous observations exhibited significant lysis activity of the phage against E. coli strain. An initial small drop in optical density (OD) was observed in cells infected with phages. After 3 h, bacterial dominance was observed, with a significant logarithmic phase of bacterial cells. After 15 h, the phage-treated culture exhibited a rapid decline phase, whereas the control E. coli culture entered to the stationary phase. A slight decrease in OD values was observed in the E. coli culture after 48 h, which indicating the decline phase of growth kinetics. The bacteriophage’s ability to limit bacterial growth resulted in a significant reduction. All the phage concentrations used in the growth kinetics assay showed lower OD values compared with the control culture. Based on the initial growth reduction, the latent period of the phage was measured as 30 min.

The one-way ANOVA statistical analysis was performed for different treatment groups using OriginPro software (Version 10.2.0.196). The buffer control was compared with the E. coli control using one-way ANOVA. The p-value (0.39483) is much greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between the groups. The low F-value (0.75071) suggests that variation between groups is minimal compared to within-group variation. Additionally, the Model Sum of Squares (0.14806) is much lower than the Error Sum of Squares (4.73327), further indicating a negligible treatment effect. Similarly, for the 0.01 MOI phage-treated group were compared with control, the p-value (0.00362) is much smaller than 0.05, indicating a statistically significant difference between the groups. The F-value (10.40) suggests a moderate to strong effect, meaning the variation between groups is substantially greater than the variation within groups. Additionally, the Model Sum of Squares (1.6693) is relatively high compared to the Error Sum of Squares (3.85308), indicating that the treatment contributes significantly to the overall variance. For the 0.1 and 1.0 MOI phage-treated groups, the results indicate a very strong statistically significant difference compared to the control. The p-value for the 0.1 MOI treatment (1.66 × 10⁻⁶) is extremely small, with a high F-value (39.61), suggesting that the variation between groups is much greater than the variation within groups. Also, Model Sum of Squares (5.4255) is substantially higher than the Error Sum of Squares (3.28731), indicating a dominant treatment effect. Similarly, for the 1.0 MOI treatment, the p-value (1.26 × 10⁻⁶) is also extremely small, with an higher F-value (41.07), further reinforcing the strong statistical significance. The Model Sum of Squares (5.62929) is considerably larger than the Error Sum of Squares (3.28969), confirming that the treatment effect is highly dominant.

In the previous report of Necel et al.41 variable levels of bacterial lysis have been noticed. Based on the concentrations (MOI) of phage used, the lytic efficiency of different phages isolated against the same host showed the complete and incomplete lytic effect in the growth kinetics inhibition assay. In the bacterial growth kinetics inhibition assay, two phages (vB_Eco4M-7 and ECML-117) shows effective killing efficiency against E. coli O157:H7 and the colony formation unit (CFU) also reduced rapidly in presence of both phages alone.

Phage-host interaction: an electron microscopy study

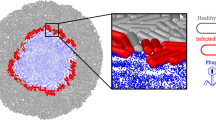

Phage initial adsorption, reproduction, cell membrane lysis, and complete collapse of E. coli cells were observed in Fig. 5. The initial adsorption of bacteriophage onto the E. coli surface was shown in Fig. 5a, which revealed the initial adsorption and injection of phage genetic material into the host bacterial cell. Figure 5b illustrates the adsorption of phages during cell division. Figure 5c indicates the initial cell damage and the presence of the phage inside the bacterial cells. Figure 5d-f revealed the complete cell collapse of E. coli with phages, and finally newly formed phages started infecting other bacteria (Fig. 5f).

HR-TEM observation of E. coli with phage: (a) and (b) Myoviridae phage was attaching themselves into E. coli host cell membrane, in this step phage insert their genetic material into the host for the production of prophage protein and DNA; (c) Once the prophage proteins responsible for head, tail and shed produced inside the host cell, endolysin a lytic enzyme involved into the cell wall lysis in E. coli cell for releasing prophage; (d)-(f) Complete host cell lysis of bacteriophage because of the endolysin activity.

The ultra-thin sectioning image of two different phages in the bacterial cell was examined using a transmission electron microscope. Phages were arranged inside the host cell; the phage tail seemed to be longer in ultra-thin sectioning image compared to the TEM image of the phage alone without bacteria42. Many qualitative and quantitative phage adsorption studies are available; among them the electron microscopic analysis provides in-depth results of phage interaction with host and their lytic cycle. An electron microscope can be used for the finding of phage-host interaction, phage adsorption and rejection in resistance type, and phage life cycle inside bacterial host. Instead of TEM or cryo-electron microscope analysis, helium ion microscopy (HIM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) are also used for identifying the phage adaptation in host cell. Both SEM and HIM can avoid the artifacts caused by the TEM image43.

Spectroscopic and microscopic analysis of biofilm

The minimal biofilm inhibition occurred at a concentration of 0.1 MOI (OD < 0.5). However, the highest biofilm inhibition was observed at 1.0 MOI in the initial treatment method. A significant reduction in OD at 0.01 MOI compared to the control was seen in Fig. 6. Disruption of E. coli biofilm by phages was assessed using spectroscopic analysis via the crystal violet assay. Significant biofilm reduction was observed in phage-treated E. coli on a polystyrene well plate compared to the untreated control (E. coli)44. An abiotic control (without bacteria and phage) was used to account for background staining, and its OD value was subtracted from both biotic control (E. coli alone) and phage treated well. SM buffer-treated biofilm showed no significant changes compared to the control E. coli biofilm.

Maximum biofilm formation occurred within 48 h of incubation. Matured biofilm eradication by phage was evaluated, as shown in Fig. 6. This study revealed that a 60 ± 5 min phage treatment at 1.0 MOI produced the most effective results for 24 and 48 h mature biofilm removal, compared to 0.01 and 0.1 MOI treatments. Similar to the initial biofilm, SM buffer showed more biofilm-like control. Based on the initial phage treatment and mature biofilm inhibition, the SM buffer behaved like the untreated control. Based on both initial treatment and mature biofilm eradication assays, SM buffer did not contribute to biofilm disruption.

In statistical analysis, the one-way ANOVA was used to compare OD values of the biotic control at different time intervals with other groups (buffer control and phage treatments at 0.01, 0.1 and 1.0 MOI). The buffer control was compared to the untreated control, yielding a p-value of 0.39403. Since this value is greater than 0.05, there is no statistically significant difference between the groups. The F-value for this comparison is 0.84269, which is relatively low, indicating that the variation between groups is not significantly larger than the variation within groups. This suggests that the buffer alone does not affect E. coli biofilm formation, even though the same buffer was used for phage resuspension. For the 0.01 MOI phage-treated E. coli biofilm, the p-value is 0.0000385, which is very less than 0.05, indicating a highly significant difference between the groups. The F-value for this treatment is 33.42, which is even higher than in the previous comparison, suggesting there is a variation between groups. These results indicate that the 0.01 MOI phage treatment has very low biofilm disruption activity.

In contrast, the 0.1 MOI phage treatment produced a p-value of 0.0001402, again significantly lower than 0.05, indicating a statistically significant difference. The high F-value (73.14) shows that between groups variation was much greater than within groups variation, pointing to a strong treatment effect. Similarly, the 1.0 MOI phage treatment produced a p-value of 0.0000356, which is also much smaller than 0.05, confirming the statistical significance. The F-value for this treatment is 118.52, further indicating a substantial difference between groups. These results suggest that both 0.1 MOI and 1.0 MOI phage treatments exhibit strong biofilm disruption activity in E. coli.

Phages reduce initial E. coli biofilm formation by lysing bacteria in their planktonic form before attachment and transition to the sessile stage. However, disrupting mature biofilms requires degradation of the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix to allow phage to penetrate and host cell lysis. To achieve this, phages produce depolymerase enzymes that degrade the EPS, facilitating biofilm disruption45. For instance, the crystal violet assay demonstrated in a previous study, isolated phage vB_EcoP-EG1 significantly reduced biofilm formation in both E. coli MG1655 and the clinical strain 390G7. Compared to untreated controls, biofilm biomass decreased by approximately 60% for E. coli MG1655 and 50% for 390G7 after 24 h of phage treatment. These findings suggest that phage isolated against lab strains effectively inhibits biofilm formation in both laboratory and clinical strains of E. coli46.

Spectroscopic analysis of phage-treated E. coli biofilm at 24 and 48 h: Control and SM buffer-treated E. coli biofilm cells in the CV assay show the highest OD in 570 nm, which indicates the SM buffer doesn’t involve any biofilm reduction mechanism; Then the different MOI concentration of phage treated E. coli biofilm shows the least OD compared with control, indicating the biofilm formation inhibition property (initial biofilm treatment) and biofilm eradication property (mature biofilm treatment) of isolated phage. The p-value obtained from one-way ANOVA of control compared with other groups showed the buffer control has no significant variation with control biofilm but all other phage treatments have high and extremely significant with E. coli control biofilm; Note. ns - not significant and **** - highly or extreme significant.

Microscopic examination of E. coli cells adhesion to the coverslip surface in both control and phage treated samples is shown in Fig. 7. In the control, cell attachment increased over time, correlating with the duration of incubation (Fig. 7a1 to a6). In contrast, phage-treated E. coli samples exhibited significantly reduced adhesion over the same period (Fig. 7b1 to b6), these results reveals that the isolated phage effectively inhibits the initial stage of E. coli biofilm formation.

Figures 8a and b show substantial biofilm development in E. coli after 24 and 48 h of incubation, respectively. However, phage-treated samples (Fig. 8c and d) demonstrated significantly fewer cells adhered to the surface, likely due to phage penetration and proliferation. These findings are further supported by the HR-TEM image (Fig. 5).

Phage treatment was found to disrupt the bacterial cell wall in Klebsiella pneumoniae, which may account for the reduced intensity of crystal violet staining observed, as previous report by Verma et al.47. To further assess phage interaction during biofilm formation, K. pneumonia biofilms were treated with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-labeled phage and examined under fluorescence microscope. Cells stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate revealed phage adsorption within the biofilm matrix. Notably, significant biofilm reduction was observed at 24 and 48 h post-treatment, exceeding that seen with shorter, hourly treatments, based on microscopic analysis (Fig. 8). Both spectroscopic (crystal violet assay) and microscopic (light microscopy) methods confirmed this reduction at 0.1 MOI. The CV assay showed decreased OD values (Fig. 6), while microscopy revealed reduced cell density in phage treated E. coli biofilm (Fig. 8).

Biofilm of E. coli with and without phage treatment after 24 and 48 h in the light microscope: (a) and (b) 24 and 48 h incubated E. coli biofilm without phage treatment shows more cell attachment on coverslip surface; (c) and (d) Reduction of E. coli cell in the phage treated surface at same time interval; scale bar is 100 μm.

Biofilm formation was evaluated using acridine orange (AO) staining, as shown in Fig. 9. Upon excitation with blue light, AO-stained biofilm cells emitted green fluorescence, indicating the presence of sessile E. coli cells. Control samples (Fig. 9a and b) exhibited stronger green fluorescence than phage treated sample (Fig. 9c and d), suggesting effective inhibition of biofilm development. AO, a nucleic acid intercalating dye, binds to bacterial DNA or RNA48and the fluorescence microscopy results aligned closely with those from the crystal violet assay, as seen in compound microscopy.

Acridine orange staining of E. coli biofilm at fluorescence microscope at 24 and 48 h; AO is nucleic acid labelling-based method, this will ensure the attachment of E. coli cells on the surface in the presence of phage; (a) and (b) Control E. coli biofilm at 24 and 48 h on coverslip surface with acridine orange treatment; (c) and (d) Phage treated E. coli biofilm after 24 and 48 h on the coverslip surface with AO staining; scale bar of fluorescence images is 100 μm.

Further analysis of biofilm morphology was conducted using HR-SEM, as illustrated in Fig. 10. HR-SEM provides label-free visualization of biofilm structure without altering cell morphology. The untreated surface (control) showed dense cell adhesion after 24, and 48 h (Fig. 10a and b) along with EPS matrix, particularly after 48 h (Fig. 10b). EPS, composed of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and eDNA, is crucial component of biofilm structure that protects bacterial cells from environmental stress49,50. In contrast, electron micrograph of phage treated surface (Fig. 10c and d) revealed significantly fewer attached cells and absence of visible EPS matrix. These electron microscopic findings strongly support fluorescence and compound microscopy observations, confirming the antibiofilm potential of isolated phage.

High-resolution scanning electron microscopy observation of E. coli biofilm at 24 and 48 h incubation with and without phage treatment on coverslip surface: (a) and (b) Control biofilm of the host cell at 24 and 48 h, respectively; (c) and (d) Phage infected host cell biofilm at 24 and 48 h at coverslip surface, respectively. Biofilm was fixed with 5% glutaraldehyde and dehydrated with different concentrations of ethanol.

For instance, Salmonella enteritidis isolated from chicken samples was evaluated for phage treatment for antibiofilm activity. HR-SEM analysis of mature and initial biofilm on stainless steel surface with a cocktail of phage shows exceptional outcomes compared with control. For additional confirmation, a similar surface was evaluated for CLSM analysis with live and death staining, which reveals more death cells in phage cocktail treatment51. Another study described biofilm eradication and depolymerase activity of a cocktail of phage (vB_KpnS_FZ10, vB_KpnP_FZ12 and vB_KpnM_FZ14) against mature biofilm of K. pneumoniae. The outcome of this study reveals the phage cocktail disrupt the K. pneumoniae biofilm effectively and was evaluated by optical and scanning electron microscopic analysis52.

Biofilm Inhibition mechanism of phage

In contrast to antibiotics, phages possess many mechanisms to lyse bacteria inside biofilms (Fig. 11). The use of phage depolymerase (holin) is a well-established and effective technique for the destruction of biofilms by phages53,54. The size of the phage influences its penetration into the biofilm matrix compared to other bactericidal agents52. For instance, Park et al.55 characterized a novel 98 kDa phage depolymerase, Dpo10 that targeting E. coli O157 lipopolysaccharides. Dpo10 showed specific O-polysaccharide degradation, remained active below 55 °C, and enhanced serum lysis without affecting growth. It inhibited biofilm formation by 8-fold on polystyrene and stainless steel 2.56 log CFU/coupon, suggesting strong anti-biofilm potential. Endolysin is a phage enzyme synthesized inside the bacterial cell to lyse the bacterial cell membrane, facilitating the release of prophage into the external environment. It also contributes to the process of biofilm eradication when phages infect biofilm-associated bacteria. A study by Abdurahman et al.56 cloned and expressed the 66 kDa endolysin LysSA52 from S. aureus phage 52. The 1446-bp lysSA52 gene was inserted into E. coli, showing high homology with other phage endolysins. LysSA52 lysed 8 of 10 Gram-positive strains and reduced S. aureus and S. epidermidis biofilms by ~ 60% in 12 h. This EPS depolymerase decreases the structural integrity of biofilms, facilitating phage penetration and subsequent killing of their host bacteria. Phages may modify bacterial metabolic pathways, disrupting biofilms57,58,59.

Mechanism of phage in biofilm disturbance using depolymerase, quorum sensing inhibition and tail-specific protein binding on biofilm bacteria; phage tail protein is like a lock and key model, which specifically binds to its host organism for infection and production of prophage; Depolymerase (holin) is a specific enzyme produced by phage for initiation of host infection and insertion of genetic material inside the host cell; The size of the phage is nanoscale, it was easy to penetrate the biofilm of bacteria to kill their host present inside the biofilm.

Conclusions

In this study, E. coli specific phage was isolated and morphologically identified as a member of the Myoviridae family using HR-TEM with negative staining (2% uranyl acetate). The phage exhibits strong lytic activity, with a titer of approximately 1010 PFU/mL determined by the DLA method. The latent period was 30 min, as determined by growth kinetic inhibition assay. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the growth kinetics of E. coli control with other experimental groups. The buffer control showed no significant difference from the untreated control, while phage-treatment at 0.01, 0.1, and 1.0 MOI significantly inhibited bacterial growth. HR-TEM micrographs qualitatively confirmed effective bacterial lysis. Spectroscopic (CV assay at 570 nm) and microscopic (light, fluorescence, and HR-SEM microscopy) analyses demonstrated substantial reductions in biofilm formation at 24 and 48 h, particularly MOIs of 0.1 and 1.0. Microscopic examination of phage-treated coverslip surfaces, combined with various staining techniques and HR-SEM imaging, revealed a significant decrease in biofilm matrix and bacterial cell density. These findings indicate that a phage concentration of 0.1 MOI is sufficient to achieve effective E. coli cell lysis and biofilm disruption. This study highlights the potential of this phage, either alone or as part of cocktail with other bioactive agents, as a promising strategy to combat antimicrobial resistance and biofilm-associated infections in both medical and food sectors, particularly those involving uropathogenic E. coli.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

No new codes were generated or used in this study.

References

Ansari, M. A., Khan, H. M., Khan, A. A., Cameotra, S. S. & Pal, R. Antibiofilm efficacy of silver nanoparticles against biofilm of extended spectrum β-lactamase isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Appl. Nanosci. 4, 859–868 (2014).

Sharma, D., Misba, L. & Khan, A. U. Antibiotics versus biofilm: an emerging battleground in microbial communities. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 8, 76 (2019).

Vestby, L. K., Grønseth, T., Simm, R. & Nesse, L. L. Bacterial biofilm and its role in the pathogenesis of disease. Antibiotics 9, 59 (2020).

Milano, A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance trends of Escherichia coli isolates from outpatient and inpatient urinary infections over a 20-Year period. Microb. Drug Resist. 28, 63–72 (2022).

Easwaran, M., Madasamy, S. & Venkidasamy, B. Theranostic potential of bacteriophages against oral squamous cell carcinoma. Curr. Gene Ther. 25, 89–91 (2025).

Iqbal, Z., Mumtaz, M. Z. & Malik, A. Extensive drug-resistance in strains of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from paediatric urinary tract infections. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 16, 565–574 (2021).

Rajimon, K. J., Sarojini, B. K., Thangaiyan, P. & Thomas, R. A sustainable approach to fluorescent chalcone synthesis targeting E. coli ribonuclease P and bacteriophage G4: combined experimental and theoretical investigation of photophysical and biological properties. J. Mol. Struct. 1330, 141533 (2025).

Thattil, S. J. & Ajith, T. A. Emergence of third generation cephalosporin resistant Escherichia coli in infants: retrospective study from a tertiary care hospital in South India. Antiinfect Agents. 19, 215–219 (2021).

Kasanga, M. et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Escherichia coli isolated from clinical and environmental samples: findings and implications. JAC Antimicrob. Resist 6, dlae061 (2024).

Abd El-Aziz, E., Sheikh, E., Galal, S., Refky, Y. & A. & Possible alternative strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance. Zagazig Vet. J. 52, 1–24 (2024).

Ragupathi, N. K. D. et al. Phage-based therapy against biofilm producers in gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 178, 106064 (2023).

Sivaperumal, P. & Kamala, K. Bacteriophages as novel tumor targeting therapy for oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cancer. Oral Oncol. 133, 106020 (2022).

Lee, Y. D. & Park, J. H. Characterization and application of phages isolated from sewage for reduction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in biofilm. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 60, 571–577 (2015).

Fründt, T. et al. Low incidence of colonic complications after severe Shiga toxin-producing E. coli O104:H4 infection. Z. Gastroenterol. 60, 1104–1110 (2022).

Ikpe, F., Williams, T., Orok, E. & Ikpe, A. Antimicrobial resistance: use of phage therapy in the management of resistant infections. Mol. Biol. Rep. 51, 925 (2024).

Hitchcock, N. M. et al. Current clinical landscape and global potential of bacteriophage therapy. Viruses 15, 1020 (2023).

Dong, G. et al. Effects of sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations of Ciprofloxacin on biofilm formation and virulence factors of Escherichia coli. Brazilian J. Infect. Dis. 23, 15–21 (2019).

Minogue, T. D. et al. Complete genome assembly of Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, a serotype O6 reference strain. Genome Announc 2, e00969–14 (2014).

Jokar, J. et al. Enhancement of bactericidal effects of bacteriophage and gentamicin combination regimen against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains in a mice diabetic wound model. Virus Genes. 60, 80–96 (2024).

Santamaría-Corral, G., Pagán, I., Aguilera-Correa, J. J. & Esteban, J. García-Quintanilla, M. A novel bacteriophage infecting Multi-Drug- and Extended-Drug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Antibiotics 13, 523 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Isolation and identification of a novel phage targeting clinical multidrug-resistant Corynebacterium striatum isolates. Front Cell. Infect. Microbiol 14, 1361045 (2024).

Yaşa, İ. et al. Partial characterization of three bacteriophages isolated from aquaculture hatchery water and their potential in the biocontrol of Vibrio spp. Microorganisms 12, 895 (2024).

Ateba, C. N. & Akindolire, M. A. Isolation and Characterisation of Bacteriophages with Lytic Activity Against Virulent Escherichia coli O157:H7: Potential Bio-Control Agents. Preprint at (2019). https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints201901.0132.v1

Lee, C., Choi, I. Y., Park, D. H. & Park, M. K. Isolation and characterization of a novel Escherichia coli O157:H7-specific phage as a biocontrol agent. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 18, 189–199 (2020).

Manohar, P. & Ramesh, N. Improved lyophilization conditions for long-term storage of bacteriophages. Sci. Rep. 9, 15242 (2019).

Merabishvili, M. et al. Stability of Staphylococcus aureus phage ISP after Freeze-Drying (Lyophilization). PLoS One. 8, e68797 (2013).

Mallick, B., Mondal, P. & Dutta, M. Morphological, biological, and genomic characterization of a newly isolated lytic phage Sfk20 infecting Shigella flexneri, Shigella sonnei, and Shigella dysenteriae1. Sci. Rep. 11, 19313 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. Characterization of the Escherichia coli Virulent Myophage ST32. Viruses 10, 616 (2018).

Sivakumar, L. et al. Formulations of chitosan/TiO2/ZnO ternary nanocomposites-based alkyd nanopaint for marine anti-biofouling application. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation. 204, 106136 (2025).

Ribeiro, K. V. G. et al. Bacteriophage isolated from sewage eliminates and prevents the establishment of Escherichia Coli biofilm. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 8, 85–95 (2018).

Shen, Y., Köller, T., Kreikemeyer, B. & Nelson, D. C. Rapid degradation of Streptococcus pyogenes biofilms by plyc, a bacteriophage-encoded endolysin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 1818–1824 (2013).

Jiang, H. et al. Antibacterial, Antibiofilm, and Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides Obtained from Fresh Sarcotesta of Ginkgo biloba: Bioactive Polysaccharide that Can Be Exploited as a Novel Biocontrol Agent. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 1–10 (2021). (2021).

Danikowski, K. M. & Cheng, T. Alkaline phosphatase activity of Staphylococcus aureus grown in biofilm and suspension cultures. Curr. Microbiol. 75, 1226–1230 (2018).

Kannan, S., Solomon, A., Krishnamoorthy, G. & Marudhamuthu, M. Liposome encapsulated surfactant abetted copper nanoparticles alleviates biofilm mediated virulence in pathogenic Pseudomonas aeruginosa and MRSA. Sci. Rep. 11, 1102 (2021).

González-Gómez, J. P. et al. Efficacy of novel bacteriophages against Escherichia coli biofilms on stainless steel. Antibiotics 10, 1150 (2021).

Aziz, R. K. et al. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 9, 75 (2008).

Overbeek, R. et al. The SEED and the rapid annotation of microbial genomes using subsystems technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D206–D214 (2014).

Brettin, T. et al. RASTtk: A modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for Building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci. Rep. 5, 8365 (2015).

Beutin, L. et al. Spread of a distinct Stx2-Encoding phage prototype among Escherichia coli O104:H4 strains from outbreaks in germany, norway, and Georgia. J. Virol. 86, 10444–10455 (2012).

Dika, C., Duval, J. F. L., Ly-Chatain, H. M., Merlin, C. & Gantzer, C. Impact of internal RNA on aggregation and electrokinetics of viruses: comparison between MS2 phage and corresponding Virus-Like particles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 4939–4948 (2011).

Necel, A. et al. Characterization of a bacteriophage, vB_Eco4M-7, that effectively infects many Escherichia coli O157 strains. Sci. Rep. 10, 3743 (2020).

Mirzaei, M. K. et al. Proteomic, morphological, and phylogenetic analyses of vB_EcoP_SU10, a Podoviridae phage with C3 morphology. PLoS One. 9, e116294 (2014).

You, X. et al. Phage co-transport with hyphal-riding bacteria fuels bacterial invasion in a water-unsaturated microbial model system. ISME J. 16, 1275–1283 (2022).

Latka, A. & Drulis-Kawa, Z. Advantages and limitations of microtiter biofilm assays in the model of antibiofilm activity of Klebsiella phage KP34 and its depolymerase. Sci. Rep. 10, 20338 (2020).

Brás, A. et al. Effect of bacteriophages against biofilms of Escherichia coli on food processing surfaces. Microorganisms 12, 366 (2024).

Gu, Y. et al. Identification of novel bacteriophage vB_EcoP-EG1 with lytic activity against planktonic and biofilm forms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 315–326 (2019).

Verma, V., Harjai, K. & Chhibber, S. Structural changes induced by a lytic bacteriophage make Ciprofloxacin effective against older biofilm of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Biofouling 26, 729–737 (2010).

Al-Ansari, M. et al. Facile and Cost-Effective ag nanoparticles fabricated by Lilium lancifolium leaf extract: antibacterial and antibiofilm potential. J. Clust Sci. 30, 1081–1089 (2019).

Vandana, Priyadarshanee, M. & Das, S. Bacterial extracellular polymeric substances: biosynthesis and interaction with environmental pollutants. Chemosphere 332, 138876 (2023).

Khan, M. S. A., Altaf, M. M. & Ahmad, I. Chemical Nature of Biofilm Matrix and Its Significance. in Biofilms in Plant and Soil Health 151–177Wiley, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119246329.ch9

Ning, Z. et al. Biofilm removal mediated by Salmonella phages from chicken-related sources. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 12, 1799–1808 (2023).

Zurabov, F., Glazunov, E., Kochetova, T., Uskevich, V. & Popova, V. Bacteriophages with depolymerase activity in the control of antibiotic resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilms. Sci. Rep. 13, 15188 (2023).

Shivaram, K. B., Bhatt, P., Applegate, B. & Simsek, H. Bacteriophage-based biocontrol technology to enhance the efficiency of wastewater treatment and reduce targeted bacterial biofilms. Sci. Total Environ. 862, 160723 (2023).

Guo, Z. et al. Identification and characterization of Dpo42, a novel depolymerase derived from the Escherichia coli phage vB_EcoM_ECOO78. Front Microbiol 8, 1460 (2017).

Park, D. W. & Park, J. H. Characterization of a novel phage depolymerase specific to Escherichia coli O157:H7 and biofilm control on abiotic surfaces. J. Microbiol. 59, 1002–1009 (2021).

Abdurahman, M. A. et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophage 52 endolysin exhibits Anti-Biofilm and broad antibacterial activity against Gram-Positive Bacteria. Protein J. 42, 596–606 (2023).

Topka-Bielecka, G. et al. Bacteriophage-Derived depolymerases against bacterial biofilm. Antibiotics 10, 175 (2021).

Guo, Z., Liu, M. & Zhang, D. Potential of phage depolymerase for the treatment of bacterial biofilms. Virulence 14, 2273567 (2023).

Liu, S., Lu, H., Zhang, S., Shi, Y. & Chen, Q. Phages against pathogenic bacterial biofilms and Biofilm-Based infections: A review. Pharmaceutics 14, 427 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are happy to acknowledge the Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Science and Humanities, SRM Institute of Science and Technology for their support. We acknowledge SRM Central Instrumentation Facility (SCIF) and SRM - DBT Platform for Advanced Life Science Technologies, SRMIST for providing the instrumentation facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M., P.P. and L.S. Formulation, Conceptualization and Designed the Experiments. J.V.J.D.K., S.M. and M.P.K.U. Performed the Experiments. S.K.A., S.R., S.S., N.J., L.K.V. and K.A. Analyzed the Data. P.P. and L.S. Wrote the Paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sivakumar, L., John Durai Kumar, J., Madhavan, S. et al. Isolation and identification of bacteriophage against Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and their biofilm Inhibition studies. Sci Rep 15, 26964 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12366-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12366-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of an experimental therapy based on bovine mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) secretome for the treatment of endometritis in dairy cows

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Harnessing bacteriophage therapy as a sustainable solution for pathogen control in aquaculture

Aquaculture International (2025)