Abstract

Global population aging highlights the need to understand how the elderly perceive safety in urban public spaces. This study used image semantic segmentation to identify key visual elements from panoramic images. A dataset was created by combining manual scoring with deep learning to explore how pocket park environments impact older adults’ safety perceptions. Analyzing 497 images from 29 pocket parks in Xiamen Island with LightGBM and SHAP tools, researchers identified visual elements that significantly affect seniors’ safety perceptions. The findings indicate: (1) Elderly environmental safety perceptions in the 29 surveyed parks on Xiamen Island were generally positive, yet safety scores varied markedly across parks. (2) Pedestrian area, car, wall, person, billboard, parterre, and vegetation were identified as the seven visual elements most impactful on elderly environmental safety perceptions. (3) Interactions among visual elements were observed, with vegetation exerting a notably regulatory effect on environmental safety perceptions, significantly enhancing the elderly’s perception of security. This study’s empirical analysis elucidates the influence of visual elements in pocket parks on elderly environmental safety perceptions, offering practical guidance for park planners to design more inclusive and secure green spaces for the elderly, with broad application potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the global aging process accelerates, the elderly population in urban areas is steadily rising. As a vulnerable yet critical demographic in urban environments, the elderly’s perception of environmental safety directly influences their willingness to engage in outdoor activities, mental health, and social participation. Creating public spaces that foster a sense of security, particularly blocks and green spaces tailored to the elderly’s unique needs, has emerged as a pressing issue in urban design and public health research.

In recent years, small-scale urban green spaces, including Pocket Parks, have gained increasing attention as effective interventions to enhance community livability. These green spaces, characterized by their compact size and strategic integration into dense urban environments, provide walkable and socially interactive natural spaces. Their accessibility and practicality make them particularly beneficial for elderly individuals with limited mobility. Pocket parks are small urban public spaces that began in the 1960s in New York to address the loss of green areas due to urban growth. The concept of “micro green space” was introduced to address these issues1. Pocket parks, usually under one hectare, can efficiently utilize space with smart design and layout2. Walking is crucial for the elderly’s health and is encouraged by pocket parks, which also foster social interaction. These parks’ impact on seniors’ walking routines is affected by factors such as ease of access, greenery, and safety3. However, whether such parks can truly enhance the elderly’s perception of environmental safety depends not only on their location and functional design but also on their visual spatial structure. Key factors include: Is the pedestrian area easily navigable? Are there obstructions or visual dead zones? Can individuals clearly observe the activities of others? These elements collectively determine whether elderly users perceive these spaces as safe.

Environmental safety perception refers to how safe individuals feel in a particular setting, affecting their likelihood to engage in outdoor activities and their mental health4. Studies have defined environmental safety perception, but it’s often confused with crime fearasafety. The research showed urban green space and plant diversity significantly improve elderly safety perception. A Chinese study found that urban greening is positively linked to residents’ mental health, especially in cities with varied architecture and socio-environmental aspects5. Environmental psychology and behavioral geography suggest that human emotional responses to the environment are rooted in the cognitive processing of visual and spatial cues. Environmental elements such as pedestrian zones, vegetation, buildings, walls, and vehicles influence spatial characteristics like lines of sight, boundaries, occlusion, and openness, which in turn affect the perceived comprehensibility, controllability, and predictability of places, thereby influencing people’s sense of security. For instance, vegetation serves as a key environmental element: moderate greening enhances comfort and privacy, whereas excessive vegetation may impede visibility and induce anxiety. Notably, the configuration of visual elements does not operate independently but interacts to shape perception through their combined effects. Drawing from the aforementioned perspective, this study defines environmental safety perception as the anticipation of negative emotional responses, such as panic and anxiety, that arise in pedestrians due to interactions with the material environment in urban public spaces. This construct extends beyond mere fear of crime and encompasses both the physical safety of the environment itself and the behavioral activities of individuals within that context6,7.

Traditional approaches to assessing environmental perception primarily utilize questionnaire surveys and open-ended interviews8,9. Time and labor constraints make acquiring data challenging, but VR technology has enabled new research into quantifying human perception. However, the use of this approach is limited by a lack of specialized equipment10. Panoramic images offer a 360-degree, high-resolution view of urban areas, enhancing environmental analysis and perception. They provide a broader field of view and detailed insight, surpassing traditional equipment with limited vision11.

Machine learning analyzes large datasets to predict environmental patterns, aiding environmental monitoring and improvement. Stancato’s method combines GIS and image segmentation to evaluate urban greening from street level, focusing on the directionality of green visibility in cities12. Chen et al. used deep learning to combine street view image recognition with walkability assessment for the elderly with different mobility levels. Results show that higher levels of greenery positively affect walking perception in all elderly groups13. Zhang et al. proposed a new framework using machine learning and street view images to assess urban green space exposure14. Machine learning is frequently utilized to assess urban data and the impact of green spaces on mental health. However, the “black box” problem, where ML models lack interpretability, hampers trust and limits their use. The SHAP method, developed by Lundberg et al., uses Shapley values from game theory to explain the contribution of each feature to ML model outputs, thereby increasing transparency and trust15. SHAP method combines global and local interpretability, matching human intuition16.

Prior studies have primarily investigated the macro-level correlations between green spaces and safety, such as statistical relationships between greening rates, lighting levels, and mental health. However, limited research has systematically explored how microscopic visual elements influence the safety perception of elderly individuals at the street scene level. Furthermore, there is a notable absence of quantitative frameworks that integrate semantic segmentation and interpretable machine learning to analyze panoramic images in this context.

To address these gaps, this study focuses on the following central research questions: (1) How do elderly individuals assess the safety of pocket parks based on visual cues? (2) Which environmental elements serve as key variables influencing safety perception? (3) Do these variables exhibit interactive effects?

To answer these questions, this paper proposes a methodological framework that integrates computer vision and interpretable machine learning. First, panoramic images of 29 pocket parks on Xiamen Island were systematically collected. Deep semantic segmentation models (e.g., DeepLabv3+, SegFormer) were employed to detect seven types of key visual elements (e.g., pedestrian areas, vehicles, vegetation) within the images. Second, a dataset of elderly safety perception was constructed using paired contrast scoring. Finally, a predictive model was developed using LightGBM, and the global and local impacts of each visual element on safety perception were analyzed using the SHAP method.

This study achieves high-precision modeling of environmental cognition mechanisms from a methodological perspective and theoretically responds to the behavioral environment theory’s emphasis on the “perception–spatial structure” coupling relationship. More importantly, the findings elucidate how visual elements synergistically enhance or diminish elderly individuals’ safety judgments of urban spaces, providing empirical support and actionable insights for the design of age-friendly environments.

Methods

Study area overview

Xiamen, a coastal city in southeast China. The city’s center, Xiamen Island (Fig. 1), is highly urbanized and densely populated, with Siming District as its core and Huli District having expansion potential. The municipal government focuses on infrastructure and public services to improve residents’ lives and stimulate economic growth. Xiamen Island, with its numerous pocket parks, is a prime location for urban park research, featuring accessible designs for the elderly. The island has 29 pocket parks, 19 in Siming and 10 in Huli District.

Study area (Map modified from Baidu Map Open Platform: https://map.baidu.com/@13151067,2810310,13z).

Data source and preprocessing

Panoramic image data collection

Road data was sourced from OpenStreetMap, checked for topology and geographic alignment, and divided at intersections. From the perspective of visual perception, a distance of approximately 20 m typically falls within the clear visual range of elderly individuals. This spatial proximity enables them to perceive critical environmental elements without requiring excessive head movement or locomotion. Collection points were strategically placed, with exclusions for segments under 5 m, one point midway for 5–10 m segments, and points every 20 m for longer ones. Points were distributed along pedestrian paths to cover the park’s terrain, considering the elderly’s preference for obstacle-free, level paths. Due to the fact that the areas of each pocket park vary, so do the numbers of internal roads. A total of 497 collection points were identified, and corresponding panoramic images were captured using the Insta360 × 4 camera.

Environmental safety perception data of the elderly

This study focuses on the environmental safety perception of elderly individuals in pocket parks across Xiamen Island. Sample collection presented challenges due to the specific nature of the research. Between 2023 and 2024, the research team collected data from 29 pocket parks on the island over a 15-month period, resulting in a total of 497 panoramic images. Subsequently, the Semantic Differential (SD) method was employed, with 88 volunteers (44 males and 44 females, aged 60 and above) invited to subjectively evaluate all images on a 1–10 scale. The sample included both retired elderly residents from local communities and active elderly individuals who frequently use the pocket parks, ensuring representativeness and reliability of the ratings. Prior to scoring, the research team established a unified scoring protocol: volunteers underwent comprehensive training to understand the scoring dimension of “environmental safety perception,” and standard image examples were provided to minimize comprehension-related score variability. The scoring process utilized a pairwise comparison method, presenting two images per round and recording the frequency of images rated as “more secure,” with scores derived indirectly as outlined in Eq. (1) to (3). To ensure consistency, each volunteer was required to evaluate all images, and inter-rater reliability was verified using Cronbach’s Alpha and Kendall’s tau-distance. Data exclusion criteria included incomplete scoring, extreme value ratings (e.g., all 1–10 s), and abnormal scoring times (e.g., less than 1 s per image on average).

Research methodology

The study focuses on three main points: (1) Identifying key variables in environmental security perception and creating an analytical framework; (2) Capturing images of pocket parks in test areas, analyzing visual aspects, and comparing safety perceptions; (3) Using the SHAP method to explore the model, identifying important visual elements affecting safety perception, and evaluating environmental safety. The results and discussion summarize the main findings and provide specific recommendations based on these insights. The study’s structure is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Selection of variables for elderly environmental safety perception model

Dependent variable: elderly environmental safety perception

This study uses environmental safety perception scores for analysis, which combine human evaluations with machine learning algorithms to analyze large datasets. It assigns two metrics to each Street View image: high safety perception probability (P) and low safety perception probability (N).

Where: P(i, higher) is the probability of image i being chosen as more secure; P(i, lower) is the probability of image i being chosen as less secure; N(i, selected) is the number of times image i is selected; N(i, not selected) is the number of times image i is not selected; N(i, equal) is the number of times image i is considered equal to the compared image. The safety perception score for Street View image i is calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2).

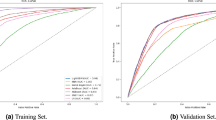

We constructed a dataset based on manual evaluation results, comprising 10,000 sets of street view image comparison data, with 80% allocated for training and 20% reserved for testing. A ConvNeXt model, leveraging a Transformer-based architecture, was employed to train the scoring model. The training parameters were configured as follows: a learning rate of 0.001, the Adam optimizer, a batch size of 20, 120 training epochs, and the CrossEntropyLoss function as the loss metric. After training completion, the model underwent performance evaluation on the test set, yielding a classification accuracy of 89.2%, an R² value of 0.781, a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.43, and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.59. These results demonstrate the model’s strong predictive capability and robustness. Finally, the trained model was utilized to automatically assess the safety perception of all panoramic images of Pocket Park, with safety perception scores calculated for each image using Eq. (3) (Fig. 3).

Explanatory variable: elderly environmental safety perception

The study focuses on image semantic segmentation, a crucial aspect of computer vision that entails pixel-level classification (Fig. 4). This study employs a two-stage segmentation strategy to enhance the accuracy of spatial perception evaluation. Initially, the MIT ADE20K network model, with ConvNeXt as the backbone, was utilized to segment street view images. The model was pretrained on the ConvNeXt dataset, which comprises 25,574 street view images (20,000 training images and 5,574 validation images annotated with 150 feature categories), using Baidu PaddleHub. However, its segmentation performance was moderate, achieving a mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) of 42.3% and a pixel accuracy of 80.1%. To further improve segmentation quality, a model trained on the Mapillary Vistas dataset (25,000 high-resolution street view images with 66 labels, including 37 instance labels) using SegFormer as the backbone was implemented. The SegFormer model was trained on a high-performance computing environment (Ubuntu system with dual RTX4090 GPUs), achieving an mIoU of 54.7% and a pixel accuracy of 84.6% on the validation set. Compared to classic semantic segmentation models such as PSPNet (mIoU 43.3%, pixel accuracy 79.8%), SegFormer demonstrates superior segmentation performance and enhanced spatial detail capture capabilities. The “pedestrian areas” mentioned in this study refers to the hard-surfaced areas where the elderly can walk normally, including roads and sidewalks, etc., but excluding motor vehicle lanes. Training was conducted on an Ubuntu server equipped with two NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs17,18. The model is capable of fulfilling the requirements of this study.

In order to reduce category redundancy and improve model efficiency, this study classified and merged 66 categories from the Mapillary Vistas dataset based on the SegFormer model, mapping them into seven key visual feature categories: pedestrian area, car, wall, person, billboard, parterre, and vegetation. The category mapping standard is based on the following three points: ① semantic similarity (such as merging sidewalks and crosswalks into pedestrian areas); ② Functional role consistency (such as merging vehicle. * into car class); ③ Correlation with environmental safety perception (excluding non impact items such as traffic light). The merging mapping relationship is detailed in Table 1.

Model development and interpretive analysis

Construct an elderly environmental safety perception model utilizing LightGBM

This study employed the LightGBM (Light Gradient Boosting Machine) algorithm to investigate the correlation between environmental safety perception and visual elements19. LightGBM, an enhanced GBDT, accelerates training by focusing on significant gradient changes using GOSS, reducing dataset size while maintaining accuracy. It employs a leaf-wise growth strategy to minimize model error and improve accuracy, with tree depth regulation to avoid overfitting and ensure stability. This method offers rapid training, reduced memory usage, and superior accuracy, establishing it as a leading optimization technique.

This study employed LightGBM to construct an elderly environmental safety perception model. LightGBM is a Gradient Boosting Tree (GBDT)-based algorithm known for its efficiency, characterized by fast training and high accuracy. The model was configured with the following hyperparameters: a learning rate of 0.05, maximum tree depth of 7, number of leaves set to 31, L1 regularization coefficient of 0.1, L2 regularization coefficient of 0.2, minimum data per leaf of 20, feature fraction and bagging fraction both set to 0.8, and bagging frequency of 5. To mitigate overfitting, 5-fold cross-validation was employed, and hyperparameters were optimized on the training set using grid search to identify the optimal configuration.

To evaluate the effectiveness of LightGBM, its performance was compared with Random Forest and XGBoost models under identical training/testing set partitions. LightGBM achieved R² = 0.823, MAE = 0.417, and RMSE = 0.545 on the testing set, outperforming Random Forest (R² = 0.765, MAE = 0.502) and XGBoost (R² = 0.796, MAE = 0.455). These results indicate that LightGBM demonstrates superior predictive accuracy and generalization capability in this research task, making it suitable for elucidating the mechanisms underlying elderly individuals’ perception of environmental safety.

Assessment of visual elements’ influence on elderly environmental safety perception

Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) is a method based on cooperative game theory, which uses Shapley values to measure the impact of each feature on the predictive outcome of models20. SHAP evaluates how features affect predictions, indicating positive or negative impacts. It integrates both global and local model explanations. The study applied SHAP to analyze visual elements’ effect on perceived environmental safety and assigned SHAP values to clarify their roles.

Where, \(\:\text{g}\left(\stackrel{\prime}{\text{Z}}\right)\) represents the predicted value of environmental safety perception of visual element \(\:\stackrel{\prime}{\text{Z}}\); \(\:{{\varnothing}}_{0}\) represents the average value of environmental safety perception; \(\:\text{M}\) represents the number of elements in the perceptual model; \(\:{{\varnothing}}_{\text{i}}\) indicates the SHAP value of the I-th visual element, and \(\:{\stackrel{\prime}{\text{Z}}}_{\text{i}}\)∈1. Mindicates whether the i-th visual element participates in the model prediction. The SHAP value is calculated as follows:

Where: \(\:{\varnothing\:}_{i}\) represents the SHAP value of the i-th visual element; \(\:\left|\stackrel{\prime}{z}\right|\) represents the set of visual elements involved in the prediction; \(\:M\) represents a set of all visual elements; \(\:\left|\stackrel{\prime}{z}\right|!\left(M-\left|\stackrel{\prime}{z}\right|-1\right)!\) represents all possible permutations of the factor set multiplied by the permutations of the factor set after removing the factor set \(\:\stackrel{\prime}{z}\) and i, that is, all factor sequences including factor i, \(\:{f}_{x}\left(\stackrel{\prime}{z}\right)-{f}_{x}\left(\stackrel{\prime}{z}\backslash\:i\right)\) represents changes in the perceived value of environmental security after adding factor i. The SHAP value represents the total difference in safety perception scores among different scenes, considering the combined impact of various visual elements’ proportions.

Result

Spatial distribution and evaluation of elderly environmental safety perception

Elderly safety perceptions of 29 pocket parks on Xiamen Island were ranked (Fig. 5), indicating central and southwest areas have better ratings. Siming District’s elderly scored lower than Huli District’s, potentially due to older infrastructure and higher population density. Huli District, developed later with a modern urban design, has higher elderly environmental satisfaction. Some pocket parks face environmental safety issues, possibly linked to their location, surroundings, and visitor numbers. To assess the impact of these factors on safety perception, we analyzed safety scores from 497 photos in these parks.

Box plots show seniors’ safety perception scores for pocket parks vary from 4 to 8 (Fig. 6). Parks 11 and 20 score above 7, while Parks 8 and 6 score below 5. Park 11 features benches and greenery, but Park 8’s proximity to traffic and lack of safety measures concern seniors. The median score indicates seniors generally perceive pocket park safety positively, though there are differences in scores. Outliers in Parks 2, 6, and 24 suggest varying safety perceptions. Park 16, despite a high score, has a low rating for its view due to safety issues. Parks with small interquartile ranges have consistent safety evaluations, while Parks 13, 16, 19, and 29, with larger ranges, show more variability. Park 29, with the largest fluctuation, is an open space near motorways lacking safety boundaries, which may affect seniors’ sense of security.

Analysis of influencing factors of elderly environmental safety perception

To ensure the absence of multicollinearity among independent variables, the study performed preliminary independent variable screening prior to model construction. First, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated for each visual variable, and all results were found to be below 5, indicating no significant multicollinearity. Subsequently, a correlation matrix analysis was conducted on the extraction proportions of the seven visual elements, with results presented in Fig. 7. While moderate correlations exist between certain variables, the overall correlation structure is acceptable and does not compromise the stability or interpretability of the subsequent LightGBM model. Thus, the seven merged visual variables were selected as the final explanatory variables for model input, ensuring appropriate variable dimensionality and clarity of explanation. Figure 7 shows a SHAP heat map that displays the impact of visual elements on SHAP values. The x-axis lists panoramic images, and the y-axis ranks elements by importance. Each cell indicates a SHAP value for a specific factor pair, with colors showing positive (red) or negative (blue) effects; intensity reflects the impact size, and white means little effect. The map indicates that pedestrian areas, cars, and walls are significant elements with strong effects. Pedestrian areas and cars consistently have a major impact, while billboards, vegetation, and motorcycles have varying effects, suggesting their influence changes with context.

Figure 8(a) shows how visual elements affect elderly safety perception in pocket parks. Shows a global feature importance ranking map, with a detailed explanation of the factor contribution results included. The graph on the left ranks factors by importance, with SHAP values indicating their impact. Wider, denser areas represent greater influence. Pedestrian areas and cars significantly affect elderly safety perception, with positive pedestrian areas enhancing safety and cars reducing it. Secondary factors like walls and vegetation also positively influence safety perception. Lower impact factors, such as fences and the sky, still contribute positively. Most pocket parks have walls, rich vegetation, but limited sky views. Grass and trees positively affect safety perception, while too many motorcycles, bicycles, and buildings can decrease it. The study identifies seven key visual elements for analysis through literature review, field research, and SHAP analysis.

Figures (b) to (h) in Fig. 8 illustrate the effect of visual element pairs on SHAP values. The X-axis indicates the visual element proportion in an image, while the Y-axis shows the SHAP value, reflecting the impact on elderly perception of environmental safety. Scatter plot colors represent the second visual element’s value, with blue for low and red for high, and point colors denote the interaction between elements.

Figure 8(b) indicates that when pedestrian areas are less than 10% of the image, negative SHAP values suggest a negative impact on elderly safety perception. As pedestrian areas increase to 10-25%, SHAP values turn positive, indicating improved safety perception. Beyond 30%, SHAP values stabilize, showing a saturation point for safety contribution. Higher vegetation correlates with higher SHAP values, enhancing the positive effect of pedestrian areas on safety perception, while low vegetation areas with negative SHAP values show a reduced safety perception effect. The enlargement of pedestrian areas signifies an enhancement in the walkability of pocket parks, with well-maintained and diverse walking facilities contributing to improved walkability in the area21. Narrow sidewalks negatively impact pedestrian perception, while wider sidewalks improve it22.

Figure 8(c) indicates that most pocket parks have low vehicular density, as shown by the concentration of car images within the 0–5% range. However, samples with over 5% car images reveal a strong negative effect on elderly environmental safety perception due to high vehicle density. Furthermore, low vehicle density and high vegetation coverage result in lower SHAP values, suggesting that vegetation does not significantly mitigate the negative impact of vehicle density on safety perception. Variability may arise from elderly concerns about traffic accidents and safety due to car flow near pocket parks23. Vehicle noise and emissions may harm the elderly’s health, reducing their comfort and security24,25. Parked vehicles can invade pedestrian areas, limiting the movement of the elderly and potentially causing accidents, reducing their environmental safety26.

Figure 8(d) shows that more pedestrians typically worsen seniors’ safety perception. A pedestrian density of 1-5% seems to improve safety perception, but beyond that, it declines. Vegetation generally enhances safety perception, especially at moderate pedestrian levels. However, at very high pedestrian densities, the benefit of vegetation is reduced, suggesting that pedestrian density has a stronger impact on safety perception. The regression is due to the lack of natural surveillance in the park when there’s little foot traffic, which may allow criminals to hide and make the elderly feel uneasy27. A large group of people can overwhelm the elderly, making it difficult for them to understand their surroundings and potentially affecting their sense of safety28. High crowd density may lead to anxiety and restlessness in the elderly, adversely impacting their perception29.

Figure 8(e) shows that a wall image ratio under 5% results in dense data points and a shift to positive SHAP values, indicating that a low wall proportion may negatively affect environmental security perception due to less enclosure or privacy. When the ratio surpasses 10%, data points become sparse, SHAP values are mostly positive and volatile, suggesting increased safety perception but potential discomfort from spatial constraints. Low vegetation correlates with low wall ratios and negative SHAP values, indicating walls have a more negative impact on environmental security perception in areas with sparse vegetation. Conversely, high vegetation areas display a more uniform distribution of positive SHAP values, suggesting that walls enhance enclosure and safety in such environments. As the proportion of wall images increases, SHAP values transition towards positivity, suggesting that a moderate presence of walls can enhance the environmental security for the elderly, potentially due to the sense of boundary and protection that walls provide30.

Figure 8(f) indicates that billboards with image ratios below 2% can negatively affect elderly safety perception, as shown by negative SHAP values. Ratios between 2 and 4% lead to positive SHAP values, implying better safety. Above 4%, SHAP values are positive but varied, suggesting that higher ratios may improve perceived security. In areas with low vegetation and billboard ratios, billboards are linked to lower safety perception, as SHAP values are low and data points are dense. As vegetation increases, SHAP values tend to rise, especially when billboard ratios exceed 4%, and the scattered distribution suggests greater variability in billboard influence. This suggests a potentially controversial role for billboards26.

Figure 8(g) shows that when parterre images are less than 5% of the environment, SHAP values are negative, indicating they may restrict movement and harm the elderly’s sense of security. With 10% flower bed imagery, SHAP values become positive, indicating improved safety perception. Beyond 15%, positive SHAP values suggest that more flower beds enhance elderly safety. Sparse flower beds have a limited positive impact, but increasing them significantly improves safety perception. The scatter plot indicates the strongest negative impact at lower values. This implies that the effect of parterre on perceived security depends on its amount or quality, and both too much and too little can have a negative effect31,32.

Figure 8(h) shows that vegetation coverage below 20% negatively impacts elderly safety perception, while coverage between 20 and 50% has a neutral effect. Coverage of 50-60% maximizes safety perception, but above 60%, the effect lessens due to dense vegetation possibly blocking visibility. In areas with few pedestrians, vegetation has minimal effect, but in high pedestrian areas, moderate coverage (40-60%) positively affects safety perception. Research shows that more greenery improves older adults’ environmental safety perception33,34,35. Pedestrians find walking paths with trees more attractive and safer, highlighting the importance of quality infrastructure in perceived safety36. Pocket parks provide temporary benefits for seniors, but dense plants can obscure views and increase fall risks due to hidden hazards2.

SHAP feature dependency diagram. (a: The overall impact of visual elements on the perception of environmental safety in the elderly, b-h: The effect of pedestrian area-vegetation/ car-vegetation/ person-vegetation/ wall-vegetation/ billboard-vegetation/ parterre-pedestrian area/ vegetation-pedestrian area on SHAP values )

Discussion

Methodology effectiveness and research framework summary

This study integrates multiple methods, including panoramic imagery, semantic segmentation, and interpretable machine learning, to establish a built environment assessment framework for quantifying elderly individuals’ perception of environmental safety. This integration demonstrates both innovative methodology and practical applicability. Unlike traditional subjective quantification methods reliant on questionnaires or field observations, we extract seven key visual elements from images using semantic segmentation and combine LightGBM and SHAP to quantify and interpret the nonlinear influence mechanisms of complex environmental elements. LightGBM excels in handling high-dimensional data and feature interactions, while SHAP provides granular interpretation of global and local feature influences. This integrated process of “perception modeling interpretation” enables systematic modeling from visual input to cognitive output.

The research framework is structured into four stages:

-

1.

Panoramic image acquisition and segmentation;

-

2.

Visual variable simplification and classification;

-

3.

Construction of a perception rating dataset;

-

4.

Explanatory machine learning modeling and interaction effects analysis (Fig. 2).

This framework is highly scalable and adaptable to diverse populations (e.g., children, women), scenarios (e.g., schools, park boundaries), or target variables (e.g., pleasure, anxiety). By adjusting perception measurement dimensions or training data, the framework can be rapidly adapted to new applications.

Correlation between vegetation regulation mechanisms and environmental behavior theory

This study identifies vegetation as a critical regulatory factor influencing elderly individuals’ perception of environmental safety, exhibiting significant nonlinear and interactive characteristics. These findings align with Environmental Behavior Theory. According to the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model, vegetation acts as an environmental stimulus that triggers cognitive processing of spatial safety and comfort through mechanisms such as visual occlusion, boundary creation, and natural association, ultimately influencing perceived safety levels. Moderate vegetation enhances accessibility, buffers noise, creates privacy, and improves security, while excessive vegetation may obstruct vision, reduce environmental predictability, and heighten uncertainty and anxiety.

Additionally, vegetation demonstrates buffering or enhancing effects in multi-factor interactions. For instance, increased greenery in high pedestrian density areas alleviates congestion, while appropriate green barriers in densely populated urban areas mitigate traffic disturbances. This regulatory mechanism underscores that environmental factors do not act in isolation but collectively influence perception.

Scalability and cross-city application recommendations

While the current model demonstrates strong adaptability based on empirical evidence from Xiamen Island, its expansion to other cities requires strategic adjustments:

-

(1)

Localized Weight Adjustment: Visual structure, social culture, and safety experiences vary significantly across cities. For example, residents in first-tier cities may have higher security thresholds for “people” compared to those in smaller cities. We recommend updating visual element importance weights using SHAP retraining or transfer learning when transferring the model.

-

(2)

Incorporation of Macro Urban Characteristics: Introduce macro variables such as urban density, road hierarchy, and green coverage rates as external adjustment parameters to enhance adaptability to spatial heterogeneity.

-

(3)

Bayesian Optimization for Local Tuning: Retrain the model with local samples and use Bayesian optimization to adjust parameter combinations, improving convergence efficiency and generalization in new scenarios.

-

(4)

Expansion to Multisensory Dimensions: Future work could integrate non-visual perception features (e.g., soundscapes, lighting environments) to enhance the comprehensiveness and adaptability of elderly perception models.

Limitations and future directions

While this study advances methodological integration and mechanism interpretation, limitations persist. First, the sample is restricted to Xiamen Island, and image acquisition methods are constrained by geographical and policy factors, limiting representativeness. Second, safety perception data rely on subjective ratings, which, despite consistency checks, remain influenced by individual experience. Third, the model lacks dynamic flow or behavior data, hindering comprehensive modeling of behavior-cognition feedback paths.

Future research should expand sampling to include diverse parks or urban areas, incorporate multimodal data (e.g., crowd tracking, semantic voice feedback), and conduct cross-cultural comparative experiments to analyze cultural influences on perceptual preferences. These steps will enhance the multi-contextual transferability of urban perception models.

Conclusion

This study uses LightGBM and SHAP frameworks to explore environmental security perceptions among the elderly and park police in Xiamen Island’s 29 pocket parks. Key findings are summarized:

-

(1)

Elderly residents on Xiamen Island rate the environmental safety of pocket parks positively, with Huli District leading in perceived security due to its modernization. Siming District, with its older infrastructure and denser population, has lower ratings. Park11 has the highest average score, and Park29 has the most varied scores. Parks 1, 2, 8, 17, 22, 24, 27, and 28 have the least variance, with Park8 scoring the lowest.

-

(2)

Pedestrian area and car density are the most influential factors in Elderly Environmental Safety Perception, with pedestrian area enhancing and car density diminishing the sense of security. Moderately influential factors such as wall, person, billboard, parterre, and vegetation also contribute to safety perceptions, albeit to a lesser extent.

-

(3)

The interaction among the seven visual elements suggests that a well-planned layout can optimize spatial functionality and enhance elderly environmental safety perception in pocket parks. Vegetation’s moderating effect is most pronounced when combined with pedestrian areas, as both excessive and insufficient vegetation levels reduce this effect. While vegetation can mitigate the impact of negative factors like vehicle density and crowding, it cannot completely neutralize them. The optimal range for specific elements includes a moderate proportion of pedestrian area (10-30%), vegetation (20-60%), and billboard (2-4%). Achieving a multi-factor dynamic balance is complex and requires a comprehensive consideration of the proportion and layout of various elements in planning for the best outcomes.

This study offers a framework to understand how visual element interactions affect environmental safety perceptions, offering actionable insights for urban planners and policymakers to design inclusive and safe urban green spaces for older adults.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.Data supporting the results of this study can be released upon application to the Science and Technology Ethics Committee of Jimei University, who can be contacted at Email: 404822992@qq.com. The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, H. & Han, M. Pocket parks in English and Chinese literature: a review. Urban For. Urban Green. 61, 127080 (2021).

Kerishnan, P. B. & Maruthaveeran, S. Factors contributing to the usage of pocket parks―a review of the evidence. Urban For. Urban Green. 58, 126985 (2021).

Zhu, D. et al. Understanding complex interactions between neighborhood environment and personal perception in affecting walking behavior of older adults: A random forest approach combined with human-machine adversarial framework. Cities 146, 104737 (2024).

Arellana, J. et al. Urban walkability considering pedestrians’ perceptions of the built environment: a 10-year review and a case study in a medium-sized City in Latin America. Transp. Reviews. 40 (2), 183–203 (2020).

Wei, Z., Jiejing, W. & Bo, Q. The relationship between urban greenness and mental health: A national-level study of China. Landsc. Urban Plann. 238, 104830 (2023).

Zeng, E. et al. Perceived safety in the neighborhood: exploring the role of built environment, social factors, physical activity and multiple pathways of influence. Buildings 13 (1), 2 (2023).

Gao, M., Zhu, X. & Cheng, X. Safety–Premise for play: exploring how characteristics of outdoor play spaces in urban residential areas influence children’s perceived safety. Cities 152, 105236 (2024).

Grahn, P. & Stigsdotter, U. K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Lands. Urban Plan. 94(3–4), 264–75 (2010).

Kabisch, N., Qureshi, S. & Haase, D. Human–environment interactions in urban green spaces—A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 50, 25–34 (2015).

Baran, P. K. et al. An Exploratory Study of Perceived Safety in a Neighborhood Park Using Immersive Virtual Environments3572–81 (Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2018).

Gao, S. et al. Review on panoramic imaging and its applications in scene Understanding. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–34 (2022).

Stancato, G. The visual greenery field: representing the urban green visual continuum with street view image analysis. Sustainability 16 (21), 9512 (2024).

Chen, Y., Huang, X. & White, M. A study on street walkability for older adults with different mobility abilities combining street view image recognition and deep learning-The case of Chengxianjie Community in Nanjing (China). Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 112, 102151 (2024).

Zhang, T. et al. Measuring urban green space exposure based on street view images and machine learning. Forests 15 (4), 655 (2024).

Lundberg, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. ArXiv Preprint arXiv:170507874, (2017).

Pan, C. et al. Data science basis and influencing factors for the evaluation of environmental safety perception in Macau parishes. Adv. Continuous Discrete Models. 2024 (1), 44 (2024).

Shafiq, M. & GU, Z. Deep residual learning for image recognition: A survey. Appl. Sci. 12 (18), 8972 (2022).

Huang, J., Guixiong, L. & He, B. Fast semantic segmentation method for machine vision inspection based on a fewer-parameters atrous Convolution neural network. PloS One. 16 (2), e0246093 (2021).

Hajihosseinlou, M., Maghsoudi, A. & Ghezelbash, R. A novel scheme for mapping of MVT-type Pb–Zn prospectivity: lightgbm, a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree machine learning algorithm. Nat. Resour. Res. 32 (6), 2417–2438 (2023).

Nohara, Y. et al. Explanation of machine learning models using Shapley additive explanation and application for real data in hospital. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 214, 106584 (2022).

Fonseca, F. et al. Built environment attributes and their influence on walkability. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 16 (7), 660–679 (2022).

Kim, Y. et al. Enhancing pedestrian perceived safety through walking environment modification considering traffic and walking infrastructure. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1326468 (2024).

Williams, T. G. et al. Parks and safety: A comparative study of green space access and inequity in five US cities. Landsc. Urban Plann. 201, 103841 (2020).

Ferguson, L. A. et al. Understanding park visitors’ soundscape perception using subjective and objective measurement. PeerJ 12, e16592 (2024).

Ren, X. et al. The effects of audio-visual perceptual characteristics on environmental health of pedestrian streets with traffic noise: A case study in dalian, China. Front. Psychol. 14, 1122639 (2023).

Park, Y. & Garcia, M. Pedestrian safety perception and urban street settings. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 14 (11), 860–871 (2020).

de Silva, B. et al. Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED): A brief review. De Silva, KBN, Dharmasiri, KS, Buddhadasa, MPAA, Ranaweera, KGNU Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED): A brief review Academia. Letters. 2021, 2337 (2021).

Cho, Y-J. et al. A empirical study on the effectiveness of CPTED facilities and techniques in a low-rise residential area. J. Archit. Inst. Korea. 37 (10), 23–34 (2021).

Kim, Y-A. & Kim, J. Examining the effects of physical environment and structural characteristics on the spatial patterns of crime in Daegu, South Korea. Crime Delinquency 70, 2166–2194 (2024).

Ren, W. et al. Research on landscape perception of urban parks based on User-Generated data. Buildings 14 (9), 2776 (2024).

Ariffin, N. D. M. et al. Manicured Versus Naturalistic Landscape Style: Public Preference of Urban Park’s Landscape in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Lis, A., Pardela, Ł. & Iwankowski, P. Impact of vegetation on perceived safety and preference in City parks. Sustainability 11 (22), 6324 (2019).

Kim, D. The transportation safety of elderly pedestrians: modeling contributing factors to elderly pedestrian collisions. Accid. Anal. Prev. 131, 268–274 (2019).

Veitch, J. et al. Designing parks for older adults: a qualitative study using walk-along interviews. Urban For. Urban Green. 54, 126768 (2020).

Kimic, K. & Polko, P. The use of urban parks by older adults in the context of perceived security. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 (7), 4184 (2022).

Basu, N. et al. The influence of the built environment on pedestrians’ perceptions of attractiveness, safety and security. Transp. Res. Part. F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 87, 203–218 (2022).

Funding

2024 Fujian Provincial education System Philosophy and Social Science Research Project (JAS24049) -AI technology empowers innovative practices in interior design education Research Project of Higher Education Science Research Laboratory of Fujian Higher Education Association in 2024 (24FJSYZD038) - Research on Interactive teaching mode of AI technology in Interior design education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shengzhen Wu and Sichao Wu wrote the main manuscript text.Jingru Chen is responsible for the Data Curation.Chen Pan is responsible for the visualization of experimental results.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study passed Science and Technology Ethics Committee of Jimei University reviews and was approved to report human experimental research. It is hereby declared that: - All methods are performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. - All experimental protocols have been approved by the designated authority and Science and Technology Ethics Committee of Jimei University. - Informed consent has been obtained from the legal guardian of all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, S., Wu, S., Chen, J. et al. Predicting geriatric environmental safety perception assessment using LightGBM and SHAP framework. Sci Rep 15, 27444 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12541-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12541-2