Abstract

Prolyl 4-hydroxylase β-subunit (P4HB) is a class of molecular chaperones that inhibits the misfolding of endoplasmic reticulum proteins, and its role in microinvasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) progresses to invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC) is currently unclear. We mined the single-cell dataset GSE189357 to analyze the role of P4HB in LUAD progression. Subsequently, P4HB was overexpressed in H1299 and A549 cell lines, and Galactose lectin-3 binding protein (LGALS3BP) expression was increased and NF-kB pathway was inhibited by PCR and WB. Meanwhile, we also knock down of P4HB in H1299 and A549 cell lines, and the LGALS3BP was decreased and NF-kB pathway was activated. Afterward, the interaction between P4HB and LGALS3BP were verified by Co-IP assays. Meanwhile, the ferroptosis level and the cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis ability were detected under different P4HB expression. Finally, overexpression and knockdown P4HB stable transplants were constructed and verified in vivo. Overexpression of P4HB promoted LUAD cell proliferation (approximately two-fold) and consequently metastasis (approximately two-fold), while inhibiting ferroptosis development, as evidenced by halved ROS production. Clinically, increased P4HB is accompanied by a poor prognosis. Mechanistically, P4HB promotes LGALS3BP expression, suppressing NF-kB pathway activation and thereby driving LUAD progression. P4HB inhibited the activation of the NF-kB pathway by promoting the expression of LGALS3BP, thus promoting the progression of MIA to IAC. This provides a new target for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of LUAD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the popularity of chest CT, many patients with early lung adenocarcinomas (LUADs) are being diagnosed. Of them, microinvasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC) are characterized as invasive types1,2. The 5-year postoperative survival rate of MIA at 5 years after surgery is about 90–95%3, however, Patients undergoing surgical resection for stage I to IIA IAC exhibit 77–92% 5-year survival probabilities4. Therefore, an in-depth exploration of the initiating mechanism of MIA to IAC progression is important to guide the clinical management and improve the prognosis.

Ferroptosis is a novel form of programmed cell death that is distinct from apoptosis, cellular necrosis, and cellular autophagy5. Its remarkable feature is the iron-dependent accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation6. There are several biological processes that ferroptosis is involved in, including iron metabolism, lipid metabolism and oxidative stress response7. An important characteristic of tumor cells is their resistance to ferroptosis, so as to enhance cancer development. The progression from MIA to IAC is a continuous process, which is malignant progression of LUAD. This change may involve increased ferroptosis resistance which is currently unclear.

Our previous research has confirmed that circP4HB inhibits ferroptosis and promotes malignant progression by regulating SLC7A11 in LUAD8. The elevated expression of circP4HB significantly correlates with heightened P4HB protein activity in tumor tissues, suggesting its potential to drive malignant phenotypes through stabilization of the parental gene-derived product. P4HB is a member of the protein disulfide isomerase family, which acts as an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone and inhibits the aggregation of misfolded proteins9. It has been reported to be upregulated in patients with gastric cancer and correlated with poor prognosis10 and its overexpression has been shown to promote hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth11. Previous studies have shown that the expression of P4HB is increased in lung cancer tissues compared to adjacent tissues12. However, the role and regulatory mechanism of P4HB mediated ferroptosis during MIA-IAC has not been reported.

In this study, we demonstrated that P4HB was highly expressed in LUAD, and functioned as an oncogene to promote LUAD progression. Furthermore, this study identified a novel signaling cascade in the P4HB/LGALS3BP/NF-kB axis that regulates tumor growth, invasion, and suppression of ferroptosis.

Methods

Clinical samples

MIA and IAC were derived from 50 patients with LUAD at The First Affiliated Hospital with Nanjing Medical University. The tissue fragments were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for next use. The present study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital with Nanjing Medical University (No. 2019SFRA-082), and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Single-cell sequencing data analysis

Our analytical strategy leveraged the complementary strengths of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and bulk RNA sequencing to address distinct aspects of LUAD progression. While bulk sequencing provides robust statistical power for population-level correlations, it is susceptible to technical and biological biases such as stromal contamination, sample purity variations, and batch effects that may obscure cell-type-specific signals13. In contrast, scRNA-seq enables resolution of tumor heterogeneity and identification of rare cell populations driving the MIA-to-IAC transition—critical advantages for delineating early malignant progression. To capitalize on these complementary approaches, we integrated both data types in our analytical pipeline.

Single-cell sequencing data were obtained from the bulk dataset GSE189357 of the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Raw data processing and quality control were performed by converting the raw unique molecular identifier count matrix into a Seurat object using the R package Seurat (version 4.0.3). The filtering threshold range was set with the following command: nFeature_RNA > 500&nFeature_RNA < 9000.mt < quantile(percent.mt,0.99)&nCount_RNA < quantile(nCount_RNA,0.99) & nCount RNA > 500. Cells outside the threshold were removed, leaving 74,283 single cells for downstream analyses.

To reduce the dimensionality of the scRNA-Seq dataset, principal component analysis was performed on an integrated data matrix. Using the Elbowplot function of Seurat, the top 30 principal components were used to perform the downstream analysis. The main cell clusters were identified with the FindClusters function of Seurat with default resolution settings (res = 0.1) and visualized with 2D tSNE or UMAP plots. Conventional markers described in a previous study were used to categorize every cell into a known biological cell type14,15,16,17,18,19. Conventional markers are detailed in the supplementary table (Supplementary Table S1). The Seurat Findallmarker function identified preferentially expressed genes in clusters or differentially expressed genes between IAC- and MIA-derived cells. Differentially expressed genes of cell subgroups were recognized by the findmarker function of Seurat. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis was performed on the differentially expressed genes using clusterProfiler (version 3.18.1).

Cell lines

All cell lines were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cell lines used in this study included the LUAD cell lines H1299 and A549 and the human bronchial epithelial cell line 16HBE. All the cell lines used in this study, including A549 and H1299, underwent mycoplasma contamination testing, and it was confirmed that the cells were free of mycoplasma contamination. All the results were negative, ensuring the reliability of the experimental data. Cells were cultured with DMEM medium (Corning, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in humidified air containing 5% CO2.

Transfections

H1299 and A549 cell lines were transfected with lentiviral vectors (Genomeditech, Shanghai, China). P4HB and LGALS3B overexpression plasmids and small interfering ribonucleic acids (siRNAs) for suppressing P4HB and LGALS3BP were purchased from Genomeditech. H1299 or A549 cells were transfected with the P4HB plasmid, LGALS3BP plasmid, control plasmid, P4HB siRNA, LGALS3BP siRNA, and control siRNA in combination or alone using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, for 24 h before use in in vitro experiments.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The primers for P4HB, LGALS3BP, and β-actin were purchased from RiboBio Company (Guangzhou, China). Primers were as follows: P4HB forward 5’-CACTGCAAACAGTTGGCTCC-3’; reverse 5’-CCGTTGTAATCAATGACCGT-3’; LGALS3BP forward 5’-ATCGCACCATTGCCTACGAA-3’; reverse 5’-CCACACCTGAGGAGTTGGTC-3’; β-actin forward 5’-CCAGCTCACCATGGATGATG-3’; reverse 5’-ATGCCGGAGCCGTTGTC-3’.

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from cells using radio-immunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Thermo, Massachusetts, USA) with 1% Halt™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo). Western blots were performed using the standard method with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-P4HB (ab2792, 1:1000), rabbit anti-LGALS3BP (ab217572, 1:1000) and rabbit anti-xCT (ab175168, 1:10000) purchased from Abcam (UK); mouse anti-NF-kB p65 (#6956, 1:1000) and rabbit anti-Phospho-NF-kB p65 (#3033, 1:1000) purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA); and β-actin (#21338, 1:10000) purchased from Signalway Antibody (USA). The HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (#L3012, 1:10000) and goat anti-mouse (#L3032, 1:10000) IgG secondary antibodies were purchased from Signalway Antibody (USA).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed by adding pre-cooled 1× IP lysis/wash buffer (enhanced) according to the Smart Classic IP/Co-IP Kit (Smart-Lifesciences, Changzhou, China) instructions, followed by pretreatment with Smart Control agarose resin. The samples were then rinsed with media using rProtein A/G Beads 4FF. Immunoprecipitation was performed by incubating the samples with the P4HB antibody overnight at 4 °C and then eluted by adding the IP elution buffer. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE, and co-precipitated proteins were detected using a western blot.

Immunofluorescence double staining

Cells were inoculated into 6-well plates. After adhesion, cells were washed, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 min, and blocked with 2% BSA for 1 h. Cells were incubated with mouse anti-P4HB and rabbit anti-LGALS3BP antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by the fluorescent secondary antibody (20000668 and 20000631, 1:3000; Proteintech, Wuhan, China) for 1 h at 25 °C, protected from light. Finally, cells were stained with DAPI, and images were obtained using a Thunder microscope (LEICA, Weztlar, Germany).

Malondialdehyde quantification

A total of 1 × 106 A549 and H1299 cells transfected with lentiviral vectors were harvested and ultrasonicated. Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were measured in the lysates using the Lipid Peroxidation Assay Kit (KGT003-KGT004; KeyGEN BioTECH, Nanjing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was measured at 532 nm.

JC-1 staining

A JC-1 fluorescence probe kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to detect the mitochondrial membrane potential of the cells. Cells were added to the JC-1 solution in the culture medium, incubated for 20 min, and washed with the JC-1 buffer solution. Photographs were taken using a Thunder microscope. The red/green fluorescence intensity ratio, which indicated the degree of mitochondrial damage, was measured using a Thunder microscope (LEICA, Weztlar, Germany).

Glutathione detection

According to the glutathione (GSH) assay kit (Boyan Biotech, Nanjing, China), the cells were collected, centrifuged, and the supernatant was discarded. A total of 5 million bacteria or cells were added to 1 mL of extraction. The cells were broken up using ultrasonication with 300 w power for 3 s (intervals of 7 s) for 3 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was stored on ice for measurement. The reaction between reduced GSH and 5,5’-Dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) formed a complex with a characteristic absorption peak at 412 nm; the absorbance was proportional to the GSH content.

Reactive oxygen species detection

According to the manufacturer’s protocols, ROS was detected in cells using a Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) assay kit (Boyan Biotech). Briefly, the DCFH-DA probe was added to a serum-free medium at a ratio of 1:1000 (final concentration of 10 µM). After removing the culture medium, an appropriate volume of diluted DCFH-DA was added to adequately cover the cells; 1 mL of diluted DCFH-DA was sufficient for one well of a 6-well plate. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min, culture medium aspirated, and washed twice with serum-free DMEM. The fluorescence was measured using a Thunder microscope, and values were proportional to the ROS content. Replicates: 5 biological replicates, each with 3 technical replicates. Statistics: Unpaired t-test (NC + erastin vs. P4HB-OE + erastin).

CCK-8 assay

The cell viability was measured using the CCK-8 assay (KeyGEN BioTECH). A549 and H1299 cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were cultured in 96-well plates and cultured for 24, 48, and 72 h. Subsequently, cells were incubated with 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent for 4 h at 37 °C. The cell optical density was then detected by a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, California, USA) with absorbance at 450 nm. CCK-8 assays were performed with three independent biological replicates, each containing six technical replicates per condition. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Transwell assay

Cell migration was assessed using a transwell chamber with an 8 μm membrane (BD Biosciences, New Jersey, USA). Briefly, 1 × 105 cells were suspended in 500 µL serum-free DMEM and loaded into the upper chamber. The lower chamber was filled with 1 mL growth medium. After incubation for 24 h, the non-migrating cells on the upper surface of the membrane were removed by scraping. The cells that had migrated to the lower surface of the membrane were fixed with 70% methanol, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and counted using an Olympus IX71 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). To assess cell invasion, cells were serum-starved overnight and loaded into the upper chamber pre-coated with Matrigel (Corning, New York, USA) (1 × 105 cells/chamber). After incubation for 24 h, the cells that had migrated to the lower surface of the membrane were fixed, stained, and counted as above. Cells in five randomly selected fields of view for each membrane were counted. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate.

Colony formation assays

Cells in the logarithmic growth phase were digested with trypsin, resuspended in a complete medium (basal medium + 10% fetal bovine serum), and counted. After the cloning, the cells were photographed using an Olympus IX71 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), washed once with PBS, and incubated in 1 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde per well for 30–60 min. After fixation, 1 mL of crystal violet staining solution was added to each well, and the cells were stained for 10–20 min. The cells were washed several times with PBS before drying and photographing. Colony formation assays were conducted in three independent biological replicates. Colonies (> 50 cells) were counted manually, and data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Wound healing

Approximately 5 × 105 cells were added to a 6-well plate. The cell layer was scratched with a 20 µL tip the next day, washed three times with sterile PBS, and incubated in fresh serum-free medium at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The cells were then removed after 0, 6, 12, and 24 h, and the width of the scratch was measured and photographed (the exact timing depended on the need of the experiment).

Immunohistochemical assay

Tissue samples from mice were fixed in formalin, paraffin-embedded, and cut into tissue sections. Subsequently, the tissues were treated with anti-P4HB (11245-1-AP, 1:200; Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-LGALS3BP (60066-1-lg, 1:200; Proteintech, Wuhan, China), anti-GPX4 (DF-6701, 1: 160; Affbiotech, Liyang, China), and anti-PTGS2 antibodies (AF7003, 1:150; Affinity, New Jersey, USA). Tissue sections were independently evaluated by three pathologists blinded to the experimental groups. Prior to scoring, all observers were trained using standardized reference images to align interpretation criteria for staining intensity (0: no staining; 1+: weak; 2+: moderate; 3+: strong) and positive cell percentage. Inter-observer variability was assessed by calculating the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) using a two-way random-effects model. The mean ICC value for all markers was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78–0.91), indicating excellent agreement. Final scores were derived from the average of the three independent ratings.

Animal studies

Six-week-old male thymic BALB/c nude mice (15–20 g) were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University (Nanjing, China) and placed in a temperature-controlled room with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. In the subcutaneous tumorigenesis model, mice were divided into four groups (LV, LV-NC, SH, and SH-NC), with 10 animals per group. Mice were randomly assigned to groups using a computer-generated random number sequence to ensure equivalent distribution of baseline characteristics (e.g., weight and age). P4HB LV, LV-NC, SH, and SH-NC stable transgenic LUAD cell lines were prepared as cell suspensions under aseptic conditions, and 0.1 mL (approximately 5 × 106 cells) was administered under the axillary skin of the mice. The diameter of the transplanted tumor, measured with vernier calipers, and body weight were recorded every four days for a maximum of 28 days. In addition, the mortality rate was recorded continuously. All the mice were anesthetized using isoflurane. All tumor diameter measurements and endpoint assessments (e.g., IHC scoring) were performed by investigators blinded to the group assignments to prevent observational bias. The mice were euthanized in the laboratory by intraperitoneal injection of high-dose pentobarbital (200 mg/kg), and the tissues were isolated for further experiments. GSH and ROS levels in mice were determined using the Reduced GSH Content Assay Kit (Biosharp, Hefei, China) and ROS Assay Kit (Bestbio, Shanghai, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Animal care and euthanasia were approved by the Nanjing Medical University (Nanjing, China) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with national or institutional animal care and use guidelines (No. IACUC:2009054).

Statistical analysis

The data are representative of the mean ± Standard Deviation. Student’s unpaired t-test and ANOVA were used for analysis, and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0.0.0 software.

Results

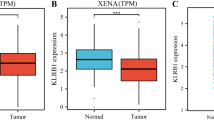

P4HB promoted the progression of lung adenocarcinoma

Gene expression analysis from mining the single-cell sequencing data of the Gene Expression Omnibus database GSE189357 showed that P4HB is one of the cluster-specific expression genes for MIA and IAC (Fig. 1A, Supplementary table S2), meanwhile, as compared with MIA, P4HB expression was increased in IAC (Fig. 1B). Since it has been reported that P4HB expression is upregulated in a variety of tumors and correlates with cancer progression20,21,22. qRT-PCR assays revealed that P4HB mRNA levels in IAC tissues (n = 30) were 2.8-fold higher than in MIA tissues (n = 20) (P < 0.01, Fig. 1C). Analysis using the Kaplan-Meier plotter database (https://kmplot.com/analysis/) showed that high expression of P4HB was accompanied by poor clinical prognosis (Fig. S1A). Here, to investigate the role of P4HB on LUAD development, we performed CCK-8 and cell cloning assays. CCK-8 assays revealed that P4HB overexpression increased proliferation by 2.1-fold in H1299 and 1.9-fold in A549 cells (P < 0.01, n = 3 biological replicates). Similarly, colony formation increased by 2.3-fold (H1299) and 2.0-fold (A549) (P < 0.01, n = 3) (Fig. 1D,E). In addition, the transwell assay and cell scratching suggested that high P4HB expression promoted cell invasion and migration (Fig. 1F,G). Collectively, P4HB might act as an oncogene, which might play an important role in LUAD progression.

P4HB promoted lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) progression. (A, B) Analysis of the GSE189357 dataset identifying that P4HB is differentially expressed between microinvasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC). (C) P4HB expression levels in IAC and MIA samples were detected by RT-qPCR assays. (D) CCK-8, (E) transwell, (F) wound healing, and (G) clone formation assays were used to detect the proliferation, invasion, and migration ability of P4HB on LUAD. Data are mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Overexpression of P4HB could inhibit cell ferroptosis

The single-cell sequencing results suggested that IAC had significantly reduced ferroptosis compared to MIA (Fig. 2A). Our previous study had identified that circP4HB was implicated in regulating ferroptosis8. Thus, we speculated that abnormal expression of P4HB participated in LUAD ferroptosis. Firstly, ROS detection showed that erastin treatment increased ROS by 220% in control cells (NC group). In P4HB-overexpressing cells, this induction was significantly attenuated, with only a 70% increase in ROS(P < 0.01), representing a 68% reduction compared to erastin-treated controls (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, three ferroptosis factors (JC-1, MDA, and GSH) were detected. JC-1 red/green fluorescence ratio increased from 1.0 ± 0.1 (NC) to 2.3 ± 0.2 (P4HB-OE) (P < 0.01). MDA levels decreased by 48% (from 5200 ± 400 µmol/mg to 2700 ± 300 µmol/mg) (P < 0.01). GSH content increased by 1.8-fold (from 12.3 ± 1.2 µmol/ml to 22.1 ± 2.1 µmol/ ml) (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2C–E). All the data revealed that upregulation of P4HB could inhibit ferroptosis.

P4HB inhibited ferroptosis in LUAD cells. (A) Analysis of the GSE189357 dataset to find differences in ferroptosis levels in MIA and IAC. Detection of the effect of P4HB on (B) ROS and (C) JC-1 levels in LUAD cells after treatment with the ferroptosis inducer erastin. (D, E) Detection of ferroptosis markers MDA and GSH in cell lines transfected with P4HB plasmid and empty plasmid. P4HB, transfected with P4HB plasmid; NC, transfected with empty plasmid. All data represent mean ± SD of four independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

P4HB could upregulate LGALS3BP expression

We performed correlation analysis by mining the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE189357) and GEPIA databases (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index) and observed that LGALS3BP expression and P4HB content in LUAD showed a positive correlation trend. Correlation analysis using the GSE189357 single-cell dataset (GEO) revealed a significant positive correlation between P4HB and LGALS3BP expression (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.23, P < 2.2e-16). Validation in bulk RNA-seq data from TCGA-LUAD (via GEPIA2) confirmed this association (r = 0.34, P < 2.2e-16) (Fig. 3A). This correlation was verified in H1299 and A549 LUAD cell lines using qPCR; overexpression of P4HB in LUAD cells increased the mRNA expression level of LGALS3BP (Fig. 3B), and similarly, the expression of LGALS3BP decreased after knocking down P4HB (Fig. 3C). Based on their relevance to tumorigenesis, we investigated co-immunoprecipitation and co-localization analyses. Protein immunoprecipitation revealed an interaction between LGALS3BP and P4HB (Fig. 3D), and immunofluorescence staining showed co-localization (Fig. 3E). Western blot revealed that increased P4HB protein expression in LUAD cells resulted in increased LGALS3BP, and decreased P4HB protein levels similarly down-regulated LGALS3BP expression (Fig. 3F,G).

P4HB promoted LGALS3BP expression in LUAD cell lines. (A) Correlation analysis: Left: GSE189357 scRNA-seq (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.23, P < 2.2e-16). Right: TCGA-LUAD bulk RNA-seq (r = 0.34, P < 2.2e-16). (B, C) H1299 and A549 cells were transfected with a P4HB vector, Control vector, P4HB siRNA, and Control siRNA alone for 24 h before qPCR analysis of P4HB and LGALS3BP mRNA expression levels. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation assay was used to identify interaction between P4HB and LGALS3BP. (E) Immunofluorescence staining was used to investigate co-localization of P4HB and LGALS3BP. Western blotting was used to detect protein levels of P4HB and LGALS3BP in (F) H1299 and (G) A549 cells (original blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

LGALS3BP inhibited activation of the NF-kB pathway to promote the progression

To investigate the role of LGALS3BP in the progression of LUAD, we overexpressed and knocked down LGALS3BP in H1299 and A549 cell line. The results revealed that ROS levels were reduced when LGALS3BP expression increased after treatment with the ferroptosis inducer erastin (Figs. 4A, S1B). Similarly, we found that JC-1 and GSH levels increased and MDA levels decreased in LGALS3BP overexpressing group (Figs. 4B–D, S1C–E). These results suggested that LGALS3BP has a ferroptosis-resistance effect. Furthermore, we performed cell scratch and transwell assays, suggesting that Overexpression of LGALS3BP increased migration by 2.6-fold in H1299 (P < 0.001) and 2.7-fold in A549 (P < 0.001, Figs. 4E, S1F). Similarly, transwell assays showed invasion acceleration by 60% (H1299) and 50% (A549) compared to controls (P < 0.01, Figs. 4F, S1G). In addition, CCK-8 and clonal formation assay suggested that LGALS3BP could promote tumor proliferation (Figs. 4G,H, S1H–I). These results reveal that the LGALS3BP plays a key role in promoting LUAD progression.

LGALS3BP inhibited activation of the NF-kB pathway to promote the LUAD progression. (A) Detection of the effect of LGALS3BP on ROS levels in LUAD cells. (B) Immunostaining was used to detect the effect of LGALS3BP on the level of JC-1 in LUAD cells. Detection of ferroptosis markers (C) GSH and (D) MDA. (E) wound healing, (F) transwell, (G) CCK-8 and (H) clone formation were used to detect the effect of LGALS3BP on the proliferation, invasion, and migration ability of LUAD cells. Western blotting was used to detect the effect of LGALS3BP on the NF-kB pathway in (I) H1299 and (J) A549 cells (original blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Since LGALS3BP negatively regulates NF-kB signaling in inflammatory fields23 to explore the relationship between the two factors in the LUAD, we analyzed this pathway using western blotting in A549 and H1299 cells after LGALS3BP overexpression and knockdown. The phosphorylation of NF-kB p65 at Ser536 has significantly decreased in LGALS3BP overexpressing tumor cells compared to LGALS3BP knockdown cells (Fig. 4I,J). In summary, LGALS3BP inhibited activation of the NF-kB pathway to promote the progression.

P4HB suppressed the NF-kB pathway by regulating LGALS3BP expression to promote LUAD progression

Based on the above results, we observed that overexpression of LGALS3BP inhibited the activation of the NF-kB pathway, and the sequencing results revealed that the decrease of P4HB had an important role in the activation of the NF-kB pathway24,25 (Fig. S2A). Therefore, we speculated whether P4HB could affect tumor progression by regulating the NF-kB pathway through LGALS3BP expression. In cell lines overexpressing P4HB, knockdown of LGALS3BP expression resulted in activation of the NF-kB pathway compared to that in the control group, despite the high expression of P4HB (Fig. 5A,B). Similarly, overexpression of LGALS3BP in the P4HB knockdown cell line significantly inhibited the NF-kB pathway (Fig. 5C,D). Functional assays revealed that LGALS3BP knockdown in cells overexpressing P4HB reduced proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of tumors, decreased GSH production, and increased ROS levels, mitochondrial damage, and peroxylated lipid degradation products. In contrast, LGALS3BP overexpression in P4HB knockdown cell lines resulted in increased tumor proliferation, invasion, and migration, increased GSH production, and decreased ROS levels, mitochondrial damage, and production of peroxylated lipid degradation products (Fig. 5E–L, S2B–C, S3A–H, S4). In conclusion, P4HB promoted LUAD progression by promoting LGALS3BP expression to inhibit the NF-kB pathway.

P4HB regulated the NF-kB pathway through inhibition of LGALS3BP to promote LUAD progression. Overexpression and knockdown of P4HB in LUAD cell lines, followed by (A, B) knockdown and (C, D) overexpression of LGALS3BP to detect changes in the NF-kB pathway (original blots/gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6). Detection of (E) ROS and (F) JC-1 levels in H1299 cells. Detection of ferroptosis markers (G) GSH and (H) MDA levels. (I) wound healing, (J) transwell, (K) CCK-8 and (L) clone formation assays were used to detect the proliferation, invasion, and migration ability of H1299 cells. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

P4HB upregulated LGALS3BP to promote tumor proliferation and inhibit ferroptosis in vivo

To characterize the role of P4HB in cancer progression, P4HB overexpression and knockdown cells were administered subcutaneously to mice. Mice administered with P4HB-overexpressing cell lines had a larger mean tumor volume and weight (Fig. 6A–C). In addition, immunohistochemical staining showed that LGALS3BP content and P4HB expression were positively correlated in mice, and GPX4 and PTGS2 content decreased with high P4HB expression, suggesting that ferroptosis was inhibited (Fig. 6D). ROS and GSH assays on mouse tumor tissues showed that ROS levels were significantly lower and GSH levels were higher in P4HB-overexpressed tumor tissues compared to P4HB- knockdown tumor tissues (Fig. 6E,F).

P4HB promoted LUAD growth and inhibited ferroptosis in vivo. Measurement of (A) tumor size, (B) volume, and (C) weight in mice. (D) Immunohistochemical staining was used for detecting P4HB, LGALS3BP, GPX4, and PTGS2 expression levels. Detection of (E) ROS and (F) GSH in tissues. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Discussion

MIA and IAC are considered as invasive lung adenocarcinoma, while IAC is a medium-grade or advanced cancer26. In this study, we identified a novel class of molecular mechanisms by which P4HB regulates the behavior of LUAD. P4HB promotes LUAD progression by promoting LGALS3BP expression to inhibit the NF-kB pathway (Fig. 7). Our results suggest that the high expression of P4HB not only promotes the proliferation, invasion and metastasis of tumor cells, but also enhances the resistance of tumor cells to ferroptosis.

P4HB is a class of molecular chaperones that is closely related to endoplasmic reticulum stress and the redox status of cells27. High concentrations of P4HB in tumor cells can help proteins fold correctly and reduce cellular damage from oxidative stress, increasing the viability of tumor cells28. The expression of P4HB was increased in LUAD tissues compared to adjacent tissues, and unexpectedly, its expression in IAC, likewise, was higher than in MIA, indicated that abnormal P4HB contributes into MIA-IAC malignant process. Meanwhile, the experimental evidence that P4HB promoted tumor invasion, growth and metastasis and inhibited ferroptosis. Furthermore, We found that LGALS3BP is a new target of P4HB, which is closely related to tumor invasion and metastasis. When P4HB expression was increased, LGALS3BP was also increased. Similarly, when P4HB was knocked down in LUAD cell lines, the expression of LGALS3BP was decreased. Finally, Mice injected with P4HB-overexpressing cells had larger tumors in weights and volumes. The immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays showed that the LGALS3BP levels were higher in the experimental overexpressing P4HB groups than the relative negative control groups.

Galactose lectin-3 binding protein (LGALS3BP) is a multifunctional secreted glycoprotein involved in immunity, inflammation, and cancer29. Since its discovery, the list of prominent cancer types associated with LGALS3BP expression has grown, including breast, prostate, pancreatic, melanoma30 and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma31. We found that when the expression of LGALS3BP was increased, the growth, invasion and metastasis ability of LUAD cells were also increased, while the level of ferroptosis was significantly decreased. LGALS3BP is a secreted glycoprotein, and we postulate a testable hypothesis: Secreted LGALS3BP may suppress NF-kB in tumor-associated immune cells (e.g., macrophages), creating an immunosuppressive niche. This model remains speculative, future studies must:1. Detect LGALS3BP in tumor interstitial fluid; 2. Validate receptor binding via surface plasmon resonance;3. Assess immune cell reprogramming in co-cultures. LGALS3BP inhibits the nuclear factor-kB(NF-kB) inflammatory signaling pathway in macrophages and mouse embryonic fibroblasts32. NF-kB is a key regulator of inflammation33 cancer, and immunity and plays an important role in various cancers34. Although inhibition of NF-kB pathway by LGALS3BP has been reported in the field of inflammation, its role in LUAD remains unclear. We observed that when LGALS3BP is overexpressed, the NF-kB signaling pathway is inhibited, and the proliferation, invasion and migration of LUAD cells are enhanced. In contrast, when LGALS3BP expression is decreased, NF-kB is activated and inhibits the progression of LUAD. Our results suggest that LGALS3BP could promote the progression of LUAD by inhibiting NF-kB activation.

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent and reactive oxygen species dependent cell death characterized primarily by cytological changes, including mitochondrial ridge reduction or loss, mitochondrial outer membrane rupture, and mitochondrial membrane concentration35. It plays a key role in inhibiting tumorigenesis by removing cells from the environment that lack key nutrients or are damaged by infection or ambient stress36. It is the first time that we have discovered that the process of MIA-IAC was accompanied by increased P4HB expression and decreased levels of ferroptosis. Overexpression of P4HB in LUAD cell lines significantly inhibited the occurrence of ferroptosis, suggesting that P4HB may contribute to the progression of LUAD by inhibiting ferroptosis. Notably, a recent pan-cancer genetic analysis of disulfidptosis-related genes revealed that dysregulation of disulfide metabolism is a conserved feature across malignancies, suggesting potential crosstalk between ferroptosis and disulfidptosis in tumor progression37. These parallel highlights the complexity of redox homeostasis in cancer and underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting P4HB-mediated disulfide bond regulation. Mining the database as well as experimental validation revealed a positive correlation between the expression of LGALS3BP and P4HB, and LGALS3BP was a regulator of NF-kB pathway. Previous studies have suggested that NF-kB is a signaling pathway that affects ferroptosis. In addition, we found that the NF-kB signaling pathway was inhibited and the level of ferroptosis was reduced after overexpression of LGALS3BP. Finally, rescue experiments demonstrated that P4HB could affect the activation of the NF-kB pathway and thus regulate the level of ferroptosis in LUAD by modulating LGALS3BP. While LGALS3BP-mediated NF-kB inhibition is well-documented in inflammation, its pro-tumorigenic role in LUAD appears paradoxical since NF-kB typically promotes cancer progression. We propose a context-dependent mechanistic hypothesis: (I)Chronic suppression of NF-kB creates an immunosuppressive microenvironment: By inhibiting NF-kB-driven cytokine production (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), LGALS3BP reduces anti-tumor immune surveillance, facilitating immune evasion. (II)NF-kB inhibition prevents ferroptosis induction: NF-kB activation can upregulate pro-ferroptosis genes (e.g., ACSL4, NOX1). Sustained LGALS3BP/NF-kB suppression thus confers ferroptosis resistance. (III)Differential subunit regulation: LGALS3BP may selectively inhibit p65 phosphorylation while preserving pro-survival NF-kB subunits, balancing anti-inflammatory and pro-tumor effects. This paradigm aligns with observed LGALS3BP-driven tumor growth and metastasis (Fig. 4E-H), providing a mechanistic bridge between inflammatory regulation and cancer progression.

This work attempts to reveal the role of P4HB in the progression of lung adenocarcinoma. Notably, we demonstrated the following: (I) P4HB inhibits ferroptosis and promotes the progression of LUAD; (II) The regulatory effect of P4HB on LGALS3BP was found for the first time; (III) The activation and inhibition of LGALS3BP on the NF-kB pathway was verified in LUAD; (IV) The molecular regulatory mechanism of P4HB/LGALS3BP/NF-kB in lung adenocarcinoma was revealed. In light of these findings, there are still some limitations to this study. First, the effect of P4HB on the prognosis of patients is not shown. Second, the deeper mechanism of the P4HB/LGALS3BP/NF-kB axis in regulating ferroptosis needs to be further investigated.

Our findings intersect with emerging immunotherapy paradigms. Tumor ferroptosis directly enhances anti-PD-1 response by releasing immunogenic DAMPs38 while NF-κB suppression in TAMs promotes immunosuppression39. Crucially, circulating biomarkers (e.g., LGALS3BP) may predict LUAD immunotherapy resistance, mirroring findings in melanoma40.

Given the pivotal role of the P4HB/LGALS3BP interaction in tumor progression, we propose this axis as a promising therapeutic target. To validate this potential, subsequent research will focus on developing targeted interventions. This will include utilizing organoid models to screen for P4HB/LGALS3BP inhibitors and evaluating their synergistic effects with immune checkpoint inhibitors, among other strategies. Concurrently, drawing inspiration from the identification of the voltage-gated sodium channel β3 subunit (SCN3B) as a glioma biomarker through multi-omics validation41 we propose that the P4HB/LGALS3BP axis warrants similar investigation in liquid biopsies. Such studies could establish circulating LGALS3BP as a non-invasive predictor for LUAD progression, mirroring the established clinical utility of SCN3B in neuro-oncology.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that P4HB is a key molecule affecting the biological behavior of LUAD, and revealed a novel signaling cascade in the P4HB/LGALS3BP/NF-kB axis that regulates tumor growth, invasion, and suppression of ferroptosis, which provided new targets and research ideas for the prognosis, diagnosis, and treatment of LUAD. Future studies should integrate multi-omics approaches to validate the clinical relevance of this axis, akin to the identification of centromere protein A (CENPA) as a pan-cancer biomarker through combined single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing42. Such strategies could uncover stage-specific expression patterns of P4HB/LGALS3BP across LUAD progression trajectories, refining patient stratification for targeted therapies.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Feng, B. et al. Differentiating minimally invasive and invasive adenocarcinomas in patients with solitary Sub-Solid pulmonary nodules with a radiomics nomogram. Clin. Radiol. 74, 570–571 (2019).

Travis, W. D., Brambilla, E., Burke, A. P., Marx, A. & Nicholson, A. G. Introduction to the 2015 world health organization classification of tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus, and heart. J. Thorac. Oncol. 10, 1240–1242 (2015).

Yotsukura, M. et al. Long-Term prognosis of patients with resected adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma of the lung. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 1312–1320 (2021).

Kameda, K. et al. Implications of the eighth edition of the Tnm proposal: invasive versus total tumor size for the T descriptor in pathologic stage I-Iia lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 13, 1919–1929 (2018).

Jiang, X., Stockwell, B. R., Conrad, M. & Ferroptosis Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 266–282 (2021).

Yu, H., Guo, P., Xie, X., Wang, Y. & Chen, G. Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death, and its relationships with tumourous diseases. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 21, 648–657 (2017).

Latunde-Dada, G. O. & Ferroptosis Role of lipid peroxidation, Iron and ferritinophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Gen Subj. 1861, 1893–1900 (2017).

Pan, C. F. et al. Circp4Hb regulates ferroptosis via Slc7a11-Mediated glutathione synthesis in lung adenocarcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 11, 366–380 (2022).

Gao, X. et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from oesophageal Cancer containing P4Hb promote muscle wasting via regulating Phgdh/Bcl-2/Caspase-3 pathway. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 10, e12060 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Prognostic value of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 alpha and Prolyl 4-Hydroxylase Beta polypeptide overexpression in gastric Cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 24, 2381–2391 (2018).

Xia, W. et al. P4Hb promotes Hcc tumorigenesis through downregulation of Grp78 and subsequent upregulation of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget 8, 8512–8521 (2017).

Xu, S., Sankar, S. & Neamati, N. Protein disulfide isomerase: A promising target for Cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 19, 222–240 (2014).

Liu, H., Li, Y., Karsidag, M., Tu, T. & Wang, P. Technical and biological biases in bulk transcriptomic data mining for Cancer research. J. Cancer. 16, 34–43 (2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Deciphering cell lineage specification of human lung adenocarcinoma with single-cell Rna sequencing. Nat. Commun. 12 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. The Voltage-Gated sodium channel Beta3 subunit modulates C6 glioma cell motility independently of channel activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol Basis Dis. 1871, 167844 (2025).

Nojima, Y., Yao, R. & Suzuki, T. Single-Cell Rna sequencing and machine learning provide candidate drugs against Drug-Tolerant persister cells in colorectal Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol Basis Dis. 1871, 167693 (2025).

Liu, H., Dong, A., Rasteh, A. M., Wang, P. & Weng, J. Identification of the novel exhausted T cell Cd8 + Markers in breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 14, 19142 (2024).

Liu, H. & Li, Y. Potential roles of Cornichon family Ampa receptor auxiliary protein 4 (Cnih4) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 35, 439–450 (2022).

Li, Y. & Liu, H. Clinical powers of aminoacyl Trna synthetase complex interacting multifunctional protein 1 (Aimp1) for Head-Neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 34, 359–374 (2022).

Crescitelli, R., Lasser, C. & Lotvall, J. Isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicle subpopulations from tissues. Nat. Protoc. 16, 1548–1580 (2021).

Flick, D. A., Gonzalez-Rothi, R. J., Harris, J. O. & Gifford, G. E. Rat lung macrophage tumor cytotoxin production: impairment by chronic in vivo cigarette smoke exposure. Cancer Res. 45, 5225–5229 (1985).

Qian, B. Z. & Pollard, J. W. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell 141, 39–51 (2010).

Hong, C. et al. Gal-3Bp negatively regulates Nf-Κb signaling by inhibiting the activation of Tak1. Front. Immunol. 10 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. Kegg as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462 (2016).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S. & Kegg Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Zhu, J. et al. Delineating the dynamic evolution from preneoplasia to invasive lung adenocarcinoma by integrating Single-Cell Rna sequencing and Spatial transcriptomics. Exp. Mol. Med. 54, 2060–2076 (2022).

Kim, Y. M. et al. Redox regulation of mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 by protein disulfide isomerase limits endothelial senescence. Cell. Rep. 23, 3565–3578 (2018).

Turano, C., Coppari, S., Altieri, F. & Ferraro, A. Proteins of the Pdi family: unpredicted Non-Er locations and functions. J. Cell. Physiol. 193, 154–163 (2002).

Koths, K., Taylor, E., Halenbeck, R., Casipit, C. & Wang, A. Cloning and characterization of a human Mac-2-Binding protein, a new member of the superfamily defined by the macrophage scavenger receptor Cysteine-Rich domain. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 14245–14249 (1993).

Zhang, D. S. et al. [Predictive significance of serum 90K/Mac-2Bp on chemotherapy response in Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma]. Ai Zheng. 22, 870–873 (2003).

Koopmann, J. et al. Mac-2-Binding protein is a diagnostic marker for biliary tract carcinoma. Cancer 101, 1609–1615 (2004).

Srirajaskanthan, R. et al. Identification of Mac-2-Binding protein as a putative marker of neuroendocrine tumors from the analysis of cell line secretomes. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 9, 656–666 (2010).

Ben-Neriah, Y. & Karin, M. Inflammation Meets cancer, with Nf-Kappab as the matchmaker. Nat. Immunol. 12, 715–723 (2011).

Taniguchi, K., Karin, M. & Nf-Kappab Inflammation, immunity and cancer: coming of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 309–324 (2018).

Xie, Y. et al. Ferroptosis: process and function. Cell. Death Differ. 23, 369–379 (2016).

Chen, X., Li, J., Kang, R., Klionsky, D. J. & Tang, D. Ferroptosis: machinery and regulation. Autophagy 17, 2054–2081 (2021).

Liu, H. & Tang, T. Pan-Cancer genetic analysis of Disulfidptosis-Related gene set. Cancer Genet. 278–279, 91–103 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Cd8(+) T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during Cancer immunotherapy. Nature 569, 270–274 (2019).

DePeaux, K. & Delgoffe, G. M. Metabolic barriers to Cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 785–797 (2021).

Splendiani, E. et al. Immunotherapy in melanoma: can we predict response to treatment with Circulating biomarkers?? Pharmacol. Ther. 256, 108613 (2024).

Liu, H., Weng, J., Huang, C. L. & Jackson, A. P. Is the Voltage-Gated sodium channel Beta3 subunit (Scn3B) a biomarker for glioma?? Funct. Integr. Genomics. 24, 162 (2024).

Liu, H., Karsidag, M., Chhatwal, K., Wang, P. & Tang, T. Single-Cell and bulk Rna sequencing analysis reveals Cenpa as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in cancers. Plos One. 20, e0314745 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82373441, No. 82372639 and No.82203577), the Jiangsu Province Natural Science Foundation (No. BK20201492), the Key Medical Research Project of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission (No. K2019002), the Clinical Capacity Improvement Project of Jiangsu Province People’s Hospital (No. JSPH-MA-2021-8).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guang Mu performed the conceptualization and methodology; Wenhao Zhang performed the formal analysis; Yan Gu and Jingjing Huang performed the validation; Hongchang Wang and Chengyu Bian performed the resources; Ke Wei and Yang Xia performed the project administration; Jun Wang performed the supervision; Guang Mu generated the figures and wrote the manuscript; All authors read the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments, https://arriveguidelines.org). Animal care and euthanasia were approved by the Nanjing Medical University (Nanjing, China) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with national or institutional animal care and use guidelines (No. IACUC:2009054).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mu, G., Zhang, W., Gu, Y. et al. The P4HB/LGALS3BP/NF-kB axis promotes the progression of MIA to IAC in lung adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 26672 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12661-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12661-9