Abstract

The most widespread primary liver cancer around the world is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and its rising incidence and mortality rates are major challenges for public health. This study investigates the role of glucocorticoids in HCC, focusing on their associated phenotypic genes and their impact on patient prognosis. Utilizing comprehensive bioinformatics approaches, a total of 751 differentially expressed genes were identified, with 470 showing increased expression and 281 showing decreased expression in tumor samples. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) indicated that tumor samples showed significant enrichment in spliceosome, ribosome, and DNA replication pathways, while control samples were enriched in complement and coagulation cascades and drug metabolism pathways. Furthermore, based on glucocorticoid-related genes, consensus clustering categorized HCC samples into two subtypes, with subtype 2 exhibiting poorer prognosis. Immune infiltration analysis indicated significant differences in various immune cell types between the two subtypes, suggesting potential immune evasion mechanisms. Drug sensitivity analysis from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database revealed that subtype 2 patients may be more responsive to certain drugs, such as Bortezomib and Dactinomycin. Furthermore, based on the established prognostic model, a total of four genes (KIF2C, CYP2C9, PON1, SPP1) were identified. These genes are both glucocorticoid-related receptors and closely associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, and they have reliable diagnostic and prognostic value. DGIdb drug prediction shows that a variety of drugs and compounds can target these four genes. Finally, immunohistochemistry revealed that in contrast to normal liver tissues, KIF2C and SPP1 were highly expressed in tumor tissues, while CYP2C9 and PON1 were expressed at lower levels in tumor tissues. This study highlights the importance of glucocorticoid-related genes in the development and prognosis of HCC, providing insights for future experimental validation and clinical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HCC represents one of the most prevalent forms of primary liver cancer globally, with both incidence and mortality rates on the rise, posing significant public health challenge1. This malignancy primarily arises in the context of chronic liver diseases, such as hepatitis B or C virus infections and cirrhosis, which are particularly prevalent in developing countries2. The economic burden and devastating effects of HCC on patients underscore the urgency of improving diagnostic and therapeutic strategies3. Current treatments include surgical resection, liver transplantation, ablation, and systemic therapies; however, the asymptomatic nature of early-stage HCC often leads to late diagnoses when treatment options become less effective4,5. Thus, gaining a more profound insight into the biological mechanisms behind HCC and discovering new therapeutic targets are essential for improving patient outcomes.

Glucocorticoids are steroid hormones that regulate many physiological responses, including inflammation and metabolism. Recent findings indicate a strong link between glucocorticoids and the development and advancement of different types of tumors6,7,8. Interestingly, there is a complex relationship between glucocorticoids and hepatocellular carcinoma. On the one hand, the activation of glucocorticoids secreted by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) has a promoting effect on liver inflammation and may even increase the risk of liver cancer. On the other hand, short-term administration of glucocorticoids such as methylprednisolone in the perioperative period of hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma can reduce the degree of early postoperative hepatocyte damage and does not increase the incidence of short-term postoperative complications. This suggests that glucocorticoids may be beneficial in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma under certain circumstances. However, the specific molecular mechanism between glucocorticoids and hepatocellular carcinoma and the role of glucocorticoid-related genes in the occurrence and development of hepatocellular carcinoma have not been studied.

To bridge the existing gaps in understanding the relationship between glucocorticoid-related genes and HCC, this study aims to systematically unravel the mechanistic roles of glucocorticoid-related genes in HCC tumorigenesis, progression, and patient prognosis. We centered on exploring the expression profiles and molecular subtyping of these genes, as well as their associations with clinical outcomes in HCC, to explicitly evaluate their potential value in disease stratification, prognostic prediction, and personalized therapy. Through this investigation, we seek to provide a theoretical foundation and novel research directions for molecular diagnostics, biomarker discovery, and the development of targeted therapeutic strategies in HCC.

Materials and methods

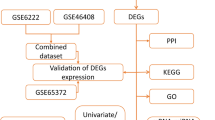

Collection and initial processing of bulk transcriptome data

Publicly available data, mainly from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), was used in this research. Applying version 2.25.0 of the R package ‘TCGAbiolinks‘9. Data on genome-wide expression profiles, clinical information, copy number variations (CNV) in TPM format, and single nucleotide mutation data (SNV) for Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (LIHC) were obtained from the TCGA database and the ‘VarScan2 Variant Aggregation’. The GEO database provides expression profile and clinical information, which are accessed through the R package ‘GEOquery’ (version 2.25.0). The study incorporated TCGA-LIHC and GSE14520, with TCGA-LIHC (n = 424) containing 374 tumor samples and 50 normal controls, and 338 samples with comprehensive prognostic information were analyzed for prognosis. The dataset GSE14520 is derived from the GPL571[HG-U133A_2] Affymetrix Human Genome U133A 2.0 Array and the GPL3921[HT_HG-U133A] Affymetrix HT Human Genome. A total of 488 samples were sequenced by the U133A Array platform, including 242 tumor samples containing complete prognostic information, which were included in this study as an external validation set to test the universality of analysis results. GSE14520 was selected as the sole external validation cohort for this study, leveraging its substantial sample size, comprehensive clinical and prognostic data, and authoritative standing in the field of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) research. This research adheres to the data access rules of each database and mainly utilizes public datasets, so no additional ethical review is required. In Fig. 1, the flow chart for this study is displayed.

Identification of Glucocorticoid-Related Genes

Genes linked to glucocorticoid phenotypes were retrieved from the Molecular Signatures Database (MsigDB) database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb).

Differential expression analysis (DEA)

To systematically screen for core regulatory targets governing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) progression, this study employed the ‘limma’ R package (version 3.50.0) to perform DEA on control and experimental (tumor) samples from TCGA-LIHC10. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using stringent criteria: |log2FoldChange (log2FC)| > 1.5 and BH-corrected p value < 0.05. Tumor subtypes are obtained by typing based on the expression profiles of glucocorticoid-related genes in TCGA-LIHC tumor samples through the unsupervised Consensus Clustering method. DEA across distinct tumor subtypes in TCGA-LIHC was conducted using identical criteria, leveraging the same ‘limma’ pipeline. Intersectional DEGs from both analyses were inferred to play critical roles in HCC tumorigenesis by activating glucocorticoid-related signaling pathways, highlighting their potential as pivotal regulators in disease progression. The volcano map and heatmap used to depict DEGs were done using ‘ggplot2’ (version 3.4.4) and ‘ComplexHeatmap’ (version 2.11.1), respectively.

Enrichment analysis of Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways and Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

The Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) algorithm was leveraged to assess whether predefined gene sets exhibit statistically significant enrichment between two biological states11. In this study, GSEA was performed using the ‘clusterProfiler’ R package (version 4.2.2), wherein all genes were ranked by their log2FC values, with each analysis incorporating 1,000 gene sets. Reference gene sets were curated from the “c2.cp.kegg.7.5.1. symbols” collection within the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB), where: “c2” denotes manually curated gene sets; “cp” signifies canonical pathways; “kegg” refers to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; “7.5.1” designates the MSigDB version; “symbols” specifies standard gene symbol formatting12,13. Gene sets with a BH-corrected p value < 0.05 were classified as significantly enriched. GO enrichment analysis examines the shared traits of genes in Biological Process (BP), Molecular Function (MF), and Cellular Component (CC)14. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) is an extensive bioinformatics resource that combines genomic, chemical, and system function data to comprehend the complex functions and applications of biological systems like cells, organisms, and ecosystems. Employed to discover metabolic pathways with significant alterations enriched in the gene list15. The official license from the Kanehisa Laboratory has been obtained. Version 4.2.2 of the R package ‘clusterProfiler’ was employed to perform GO and KEGG enrichment analysis on differential genes between subtype1 and subtype2 (p < 0.05)16.

Consensus cluster analysis

This algorithm, known as Consensus Clustering, employs resampling to identify each member and its subgroup, confirm the clustering’s soundness. The multiple iterations of consistent clustering on the subsamples of the dataset provide indicators of clustering stability and parameter decision by inducing sampling variability through subsampling. For details, please refer to the Supplementary material.

Immunoinfiltration analysis

The Single Sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) approach modifies GSEA to evaluate enrichment scores on a per-sample and per-gene set basis17. The ssGSEA enrichment score indicates how much the genes in a specific gene set are collectively up-regulated or down-regulated in the sample. Data on 28 immune cells were obtained from the interaction between tumor and immune system database (TISIDB) (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/index.php)18. For details, please refer to the Supplementary material.

Somatic mutation analysis (TMB)

Mutation data and copy number variation data based on TCGA-LIHC describe the genomic mutation landscape. Version 2.10.05 of the R package ‘maftools’ is employed to illustrate somatic differences among different subtypes19. Frequently mutated genes (FMG) with the top 20 mutation rates are generally seen as the key contributors to malignancy20.

Drug sensitivity analysis

This study leveraged the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC, https://www.cancerrxgene.org/) database to acquire drug inhibitory concentration (IC50) data and associated gene expression profiles, followed by performing drug sensitivity prediction for hepatocellular carcinoma using the ‘oncoPredict’ R package (version 1.2)21,22. For details, please refer to the Supplementary material.

Immune checkpoint

Immune checkpoints are made up of various molecules found on immune cells that control immune activation levels. They play a crucial role in preventing overactive immune responses. The two groups were compared based on the expression levels of some common immune checkpoint genes (ICGs).

Immunotherapy response (TIDE)

To assess response to immunotherapy, this study conducted a TIDE (Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion, http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) analysis23.

Establishment and validation a model for prognosis

To assess the prognostic value of glucocorticoid-related differentially expressed genes in hepatocellular carcinoma and determine the connection of each gene with overall survival (OS) in the tumor cohort, we used univariate Cox regression analysis. Genes with a P value of 0.05 or less were deemed significantly linked to overall survival and were included in further analysis. For details, please refer to the Supplementary material.

Operating characteristic curve (ROC)

ROC is a useful method for assessing the effectiveness of diagnostic tests. ROC curves are categorized into prognostic and diagnostic types, differing in application and data derivation: Prognostic ROC curves validate survival-based predictive models by gauging their discriminative ability for patient outcomes (e.g., 1/3/5-year survival). They leverage time-to-event data and compute AUC values at specific time points to assess model efficacy in stratifying survival trajectories. Diagnostic ROC curves, conversely, evaluate a gene’s utility in distinguishing tumor from normal tissues. The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve serves as a quintessential methodology for evaluating diagnostic test efficacy. The area under the curve (AUC) stands as the most pivotal evaluative metric, typically ranging between 0.5 and 1—with values approaching 1 denoting superior diagnostic or predictive model performance. To validate the constructed prognostic model, this study employed the ‘pROC’ R package to generate ROC curves and compute AUC values across the training set, validation set, and an external validation cohort (GSE14520), systematically assessing the model’s predictive capacity for survival outcomes in HCC patients24. Concurrently, samples in each dataset were stratified into high- and low-risk groups based on risk scores, with ROC curve analysis further employed to validate the model’s generalizability and clinical utility.

Establishment and validation of the nomogram

The nomogram was constructed based on a multivariate Cox regression model, yielding a continuous risk score as its output. We employed time-dependent ROC curves to evaluate the predictive ability of this continuous risk score for survival at the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year time points, without dichotomizing the risk score. Clinical data, including age, sex, and tumor stage, were derived from the TCGA cohort. The nomogram’s evaluation involved a calibration curve and a time-dependent ROC curve. For details, please refer to the Supplementary material.

DGIdb drug prediction

The Drug-Gene Interactions Database (DGIdb, https://dgidb.org) is an open-access tool that compiles data on genes, gene products, drugs, and drug-gene interactions to aid clinicians and researchers in generating hypotheses and making discoveries25. For details, please refer to the Supplementary material.

Validation by IHC in clinical sample

Human tissue samples utilized in this study were all derived from surgical resection specimens of hepatocellular carcinoma patients, comprising 10 cases each of hepatic cancer tissues and their paired adjacent normal liver tissues. Tissues from humans were preserved using 4% paraformaldehyde and then embedded in paraffin. The samples underwent dewaxing, antigen retrieval, and blocking before being incubated with KIF2C polyclonal antibody (1:300, 28372-1-AP, Proteintech, China), CYP2C9 polyclonal antibody (1:300, 16355-1-AP, Proteintech, China), PON1 polyclonal antibody (1:300, 18155-1-AP, Proteintech, China) and Osteopontin polyclonal antibody (1:300, 22952-1-AP, Proteintech, China) at 4 °C overnight, followed by a biotinylated secondary antibody incubation. Afterward, staining was conducted with DAB and hematoxylin, and images were obtained via an optical microscope. All IHC analyses were performed at least three times.

Three pathologists independently assessed the immunostaining intensity (I) and the percentage of stained cells (S). The percentage scores spanned from 0 to 100%, and the intensity scores ranged from 0 to 3, with 0 meaning no staining, 1 weak, 2 moderate, and 3 strong. Every field of view was examined using a microscope. The IS score was determined by multiplying the stained cell percentage (S) by the intensity (I), which can be from 0 to 3.

The protocol for this study received approval from the institutional ethical committee at the Affiliated Hospital of Panzhihua University. All procedures were carried out following the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Before the study began, written informed consent was secured from every patient.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in the R computing environment. Survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan–Meier method with log-rank test, while appropriate statistical tests were employed to assess intergroup differences. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Detailed analytical workflows and code are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Results

Tumor and control group differential expression analysis and GSEA enrichment analysis

Through comparing tumor and control groups, 751 DEGs were identified, showing a statistically significant difference between the two groups (|(log2FC)| >1.5, P value < 0.05 after FDR correction). In the tumor samples, 470 genes were up-regulated and 281 genes were down-regulated (Supp. Table S2). All DEGs are visualized using volcanic maps (Fig. 2A). In addition, the heat map showed the top 5 up-regulated genes (PLVAP, DIPK2B, CD34, TOMM40L, SLC26A6) and the top 5 down-regulated genes (CLEC4M, CLEC1B, STAB2, BMP10, BMPER) in P value ranking (Fig. 2B).

Analysis of differences between umor and control groups and GSEA enrichment. A The differences in gene distribution between tumor and control samples are represented by volcanic maps. Gene expression levels are shown by red, blue, and gray dots, indicating up-regulation, down-regulation, and no significant change, respectively. B Five up-regulated and five down-regulated genes, each with high P values, are represented in the heat map. GSEA analysis showed that SPLICEOSOME (C), RIBOSOME (D), DNA_REPLICATION (E) were significantly enriched in tumor group. The control group had a significant enrichment of Complem_and_coagulation_cascades (F), DRUG_METABOLISM_CYTOCHROME_P450 (G), RETINOL_METABOLISM (H).

To further examine the pathway of the most significant alterations between the tumor and control groups and to identify the main source of different patient risks, we conducted GSEA enrichment analysis between these groups. Utilizing the path data from the MsigDB database, we determined the most significant path based on the normalized enrichment score (NES), which is presented in Supp. Table S3. GSEA results showed SPLICEOSOME(NES = 1.5831, adjusted P = 0, FDR = 0, Fig. 2C), RIBOSOME(NES = 1.5764, adjusted P = 0, FDR = 0, Fig. 2D), DNA_REPLICATION (NES = 1.4975, adjusted P = 2E−04, FDR = 1e−04, Fig. 2E) was significantly enriched in tumor group. Complem_and_coagulation_cascades (NES = − 2.1966, adjusted P = 0, FDR = 0, Fig. 2F), DRUG_METABOLISM_CYTOCHROME_P450 (NES = − 2.2388, adjusted P = 0, FDR = 0, Fig. 2G), RETINOL_METABOLISM (NES = − 2.2478, adjusted P = 0, FDR = 0, Fig. 2H) were significantly enriched in the control group.

Based on glucocorticoid-related genotyping, differential expression analysis and enrichment analysis

Genes linked to glucocorticoid phenotypes were retrieved from the MSigDB database, containing a total of 363 genes (Supp. Table S1). Based on glucocorticoid-related genes, tumor samples in TCGA-LIHC were first categorized by consistent clustering method, and the classification results were shown in Fig. 3A. k = 2 was selected for clustering classification, pearson_pam was selected for algorithm, and the tumor samples were divided into two subtypes, subtype1 and subtype2 respectively. There was a significant difference in the expression patterns of glucocorticoid-related genes between these two groups.

Based on glucocorticoid-related genotyping, differential expression analysis and enrichment analysis. A Consensus cluster maps based on sample typing of glucocorticoid-associated genes. B Volcano maps describing the distribution of differential genes between subtype2 and subtype1 samples. Red, blue, and gray dots indicate gene expression levels associated with up-regulated, down-regulated, and no significant expression, respectively. C Five genes with increased expression and five with decreased expression, both having high P values, were represented in heat maps. D KM survival curve between subtypes. E Differential gene GO enrichment analysis among various subtypes. F Differential gene KEGG enrichment analysis among various subtypes.

When subtype2 was compared to subtype1, 869 DEGs were identified, showing statistically significant differences between the two groups (|(log2FC)| >1, P value < 0.05 after FDR correction). In the subtype2 samples, 440 genes showed increased expression while 429 genes showed decreased expression (Supp. Table S4). All DEGs are visualized by volcano maps (Fig. 3B). In addition, the heat map showed the top 5 up-regulated genes (IKBKE, PPP1R14BP3, PAFAH1B3, PPP1R14B, SNRPB) and the top 5 down-regulated genes (CYP8B1, TTC36, GLYAT, MTHFD1). SEC14L2) (Fig. 3C).

Moreover, we investigated the prognostic differences between subtypes. We compared subtype1 and subtype2 by drawing the KM survival curve, which revealed significant differences between the subtypes, with subtype2 having a notably poorer prognosis than subtype1 (Fig. 3D).

In parallel, to investigate the biological functions of genes that differ between subtypes, we carried out enrichment analysis of GO entries (Supp. Table S5) and KEGG pathways (Supp. Table S6). GO results show, these genes are found in small molecule catabolic process, carboxylic acid catabolic process, organic acid catabolic process(biological process, BP), blood microparticle, endoplasmic reticulum lumen, peroxisomal matrix (cellular component, CC), iron ion binding, arachidonic acid monooxygenase activity, oxidoreductase activity, acting on paired donors, with incorporation or reduction of molecular oxygen, reduced flavin or flavoprotein as one donor, and incorporation of one atom of oxygen (molecular function, MF) enrichment (Fig. 3E).

Enriched KEGG pathways include Cell cycle, Peroxisome (Cellular Processes), Chemical carcinogenes-DNA adducts, Chemical carcinogenes-receptor activation, Central carbon metabolism in DNA cancer(Human Diseases), Drug metabolism - cytochrome P450, Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450, Retinol metabolism (Metabolism), Bile secretion, PPAR signaling pathway, Complement and coagulation cascades (Organismal Systems) (Fig. 3F).

Analysis of immunoinfiltration between subtypes

Using the ssGSEA method, we further explored the infiltration levels of 28 immune cell types between the two subtypes. Histograms were used to show the relative proportions of 28 immune cell subsets (Fig. 4A, Supp. Table S7). Significant differences were observed in the Immature dendritic cell, Eosinophil, Myeloid derived suppressor cell, Activated dendritic, Activated B cell, Natural killer cell, CD56 bright natural killer cell, Type 1 T helper cell, Type 2 T helper cell, Gamma delta T cell, Activated CD4 T cell, Effector memeory CD8 T cell, and Monocyte between the subtype1 and subtype2 groups when analyzing various immune cell subtypes (P < 0.05, Fig. 4B).

TMB between subtypes and drug sensitivity

To evaluate specific gene mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma, we conducted a TMB analysis comparing subtype1 and subtype2 groups and displayed the top 20 genes with the most frequent mutations. TP53 showed the most frequent mutations in both groups, with CTTNB1 coming next (Fig. 5A, B). TMB is an essential factor for the effectiveness of immunotherapy.

Analysis of TMB and drug sensitivity among subtypes. A In the subtype1 group, the top 20 genes exhibit the highest mutation rates and B in the subtype2 group, the top 20 genes exhibit the highest mutation rates. Bortezomib_1191 (C), Dactinomycin_1911 (D), IDaporinad_1248 (E), Docetaxel_1007 (F), Paclitaxel_1080 (G), Se between subtype1 and subtype2 groups Drug sensitivity differences of pantronium bromide_1941 (H), Staurosporine_1034 (I), Vinblastine_1004 (J) and Vinorelbine_2048 (K).

We also performed drug sensitivity analysis between subtypes. The results indicate that, compared to Subtype 1, patients classified as Subtype 2 exhibited greater chemosensitivity to the following agents: Bortezomib_1191 (Fig. 5C), Dactinomycin_1911 (Fig. 5D), Idaporinad_1248 (Fig. 5E), Docetaxel_1007 (Fig. 5F), Paclitaxel_1080 (Fig. 5G), Sepantronium bromide_1941 (Fig. 5H), Staurosporine_1034 (Fig. 5I), Vinblastine_1004 (Fig. 5J), and Vinorelbine_2048 (Fig. 5K). This was evidenced by lower predicted IC50 values, indicating that Subtype 2 patients may demonstrate a superior therapeutic response to the aforementioned drugs. On the contrary, in this analysis, no significantly higher sensitivity of subtype1 to any drug was found.

Intersubtype immunotherapy response (TIDE) and immune checkpoint analysis

TIDE was utilized to assess the possible clinical effectiveness of immunotherapy in the subtype1 and subtype2 groups (Supp. Table S8). Patients with higher TIDE prediction scores are less likely to benefit from ICI treatment due to an increased likelihood of immune evasion. Our study results indicated that the TIDE score and Exclusion for the subtype2 group were greater than those for the subtype1 group (Fig. 6A). Moreover, the subtype1 group exhibited the majority of immunotherapy responses (Fig. 6B).

Intersubtype immunotherapy response (TIDE) and immune checkpoint analysis. A The TIDE prediction algorithm assessed differences in immunotherapy response between subtypes. B TIDE prediction algorithm to evaluate immunotherapy response between subtypes. C The expression of immune checkpoints among subtypes is depicted using box plots.

Moreover, we investigated the disparity in immune checkpoint expression levels between the subtype1 and subtype2 groups, with Fig. 6C showing the expression distribution. The two groups showed significant differences in immune checkpoint expression, implying that immunotherapy targeting these checkpoints might be beneficial for hepatocellular carcinoma patients by altering glucocorticoid levels.

Construction and validation of prognostic models and ROC curves of prognostic genes

In TCGA-LIHC samples, the differential gene between control group and experimental group (|(log2FC)| >1.5 and P value < 0.05 after BH correction) and the differential gene between subtypes (|(log2FC)|) were compared The intersection of > 1.5 and P value < 0.05 after BH correction was obtained, and 131 intersection genes were obtained (Fig. 7A, Supp. Table S9).

In TCGA-LIHC, Cox and LASSO regression analysis was conducted for the creation and validation of a prognostic model. A Venn diagram of intersecting genes. B LASSO regresses the change trajectory of the independent variable. The logarithm of the independent variable lambda is plotted on the abscissa, and the coefficient that is independently available is represented on the vertical axis. C Each lambda in LASSO regression has a confirmation interval. D Risk triptych for the training cohort. E Risk triplets for validation of the cohort. F Risk triplets for external validation queues. The high-risk group is indicated by red, while the low-risk group is indicated by blue.

We then construct a prognostic model using the intersection genes, which were identified through univariate Cox regression analysis with a significance level of p < 0.05. Finally, we identified 35 genes related to the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (Supp. Table S10). By random sampling, 7/10 hepatocellular carcinoma samples (n = 245) and 3/10 were selected as validation sets (n = 93). The training set underwent LASSO regression analysis to discard superfluous genes, with a random number seed of 13. As shown in Fig. 7B, C, four genes related to the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients were identified, with details provided in Supp. Table S11. To assess the model’s robustness built with four gene features, the surv_cutpoint function was employed to identify the optimal cut-off for the risk score, dividing the training samples into low and high risk group. Risk triplets of different groups of patients in the training cohort (Fig. 7D), validation cohort (Fig. 7E), and external validation set (GSE14520, Fig. 7F) were constructed. The effectiveness of the model in forecasting patient outcomes was assessed using ROC curves (Fig. 8A–C). In the training cohort, the survival AUC values for 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.778, 0.655, and 0.614, respectively, as depicted in Fig. 8A. In the validation cohort, the survival AUC values for 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.669, 0.653, and 0.686, respectively, as depicted in Fig. 8B. In the external validation cohort, the survival AUC values for 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.669, 0.671, and 0.653, respectively, as depicted in Fig. 8C. These results indicate that the good diagnostic efficacy and prognostic value of the four prognostic genes and prognostic models we obtained for HCC patients. The KM survival curves of different groups of patients in the training cohort (Fig. 8D) and verification cohort (Fig. 8E) were constructed, and the external verification set (GSE14520, Fig. 8F). The findings indicated that in the KM survival analyses conducted on the training cohort, validation cohort, and external validation set, we report the respective log-rank test P values comparing the high-risk group versus the low-risk group: training cohort P = 4.01 × 10−7, validation cohort P = 0.03, external validation set P = 0.0007. Collectively, these results demonstrate significantly inferior overall survival in high-risk group patients compared to the low-risk group, further validating the robustness and broad applicability of the constructed prognostic model.

Survival curve and ROC curve of prognostic model and ROC curve of prognostic gene. A Training cohort’s ROC curve. B Verify the queue’s ROC curve. C External validation queue’s ROC curve. D Training cohort’s Kaplan–Meier survival curve. E Validation set’s K–M survival curve. F External validation set’s Kaplan–Meier survival graph. G KIF2C’s ROC curve. H CYP2C9’s ROC curve. I PON1’s ROC curve. J SPP1’s ROC curve.

To delve deeper into the diagnostic significance of prognostic genes, ROC curves were utilized to verify the diagnostic performance of each gene. The findings indicated that the AUC values for the four prognostic genes exceeded 0.7, suggesting that these genes have a strong differential capability as potential biomarkers for diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma glucocorticoids (Fig. 8G, J).

Single-factor COX and multi-factor COX analysis and verification

To determine if risk scores could serve as independent prognostic indicators, univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were conducted on patients’ clinical features, including age, sex, and tumor stage. According to the results, the risk score served as an independent prognostic risk factor for patients, no matter which Cox regression analysis was utilized (Fig. 9A, B, Supp. Table S12). Given that the only available prognostic factor is the risk score, we deconstructed it into four prognostic genes for the subsequent construction of a nomogram. Using multivariate Cox regression analysis, a nomogram was developed, revealing that prognostic genes have a significant ability to predict clinical outcomes (Fig. 9C). The effectiveness of the nomogram in predicting patient outcomes is evaluated using ROC curves. The nomogram model’s stability and accuracy at 1, 3, and 5 years are well-supported by the correction curve (Fig. 9D). Meanwhile, the AUC for survival at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years were 0.761, 0.654, and 0.625, respectively (Fig. 9E).

Univariate COX and multivariate COX results and validation. A Combining clinical information with risk scores in forest maps through univariate Cox analysis. B Combining clinical information with risk scores in a multivariate Cox analysis of forest maps. C A nomogram of the forecast model. Clinical factors’ impact on the outcome event is shown by the line segments, each variable value’s individual scores are summed to form the total score, and each value point’s 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival prognosis is depicted by the bottom three lines. D Calibration curves for the nomogram model at 1, 3, and 5 years. E ROC curves for the nomogram model at 1, 3, and 5 years.

DGIdb drug prediction of prognostic genes

We further leveraged the DGIdb database to predict potential drugs or small-molecule compounds targeting these genes, aiming to explore their clinical translational prospects as druggable targets. We performed drug sensitivity analysis on 4 prognostic genes in DGldb, and found that 3 prognostic genes (SPP1, PON1, CYP2C9) were detected to be correlated with drugs. As shown in the drug-gene interaction network (Fig. 10A, Supp. Table S13), the top 28 drugs or molecular compounds are shown here due to the excessive number of drugs, and these drugs or molecular compounds have varying degrees of regulatory effects on prognostic genes. Check the top three two-dimensional structures through pubchem (Fig. 10B, D). These drugs are considered to have a strong binding potential with the prognostic genes and may exert their therapeutic effects in LIHC by modulating these genes.

Prognostic gene expression in clinical samples was confirmed by IHC

In order to confirm the analytic findings mentioned earlier, we furtherdetected the expression of KIF2C, CYP2C9, PON1, and SPP1 in HCC by immunohistochemistry. By immunohistochemical staining, KIF2C, CYP2C9, PON1, and SPP1 were primarily located in the cytoplasm. In HCC, KIF2C and SPP1 were expressed at high levels, significantly differing from normal tissues (P < 0.001, P < 0.001) (Fig. 11A, B, E). In HCC, CYP2C9 and PON1 were expressed at low levels, significantly differing from normal tissues (P < 0.001, P < 0.001) (Fig. 11C–E).

Validation of prognostic genes expression in clinical sample by IHC. A Visual representation of KIF2C expression through IHC in HCC and normal tissues. B Visual representation of SPP1 expression through immunostaining in HCC and normal tissues. C Visual representation of CYP2C9 expression through immunostaining in HCC and normal tissues. D Visual representation of PON1 expression through immunostaining in HCC and normal tissues. E The levels of KIF2C and SPP1 proteins were upregulated in HCC; the levels of CYP2C9 and PON1 proteins were lower in HCC; N = 10 per group (All the P values were less than 0.001).

Discussion

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is recognized as one of the most prevalent primary liver cancers globally, with its incidence and mortality rates on the rise, thereby posing significant challenges to public health. The disease is particularly burdensome in developing countries, where its occurrence is closely associated with chronic hepatitis virus infections and liver cirrhosis. HCC’s insidious nature often leads to late-stage diagnosis due to a lack of early symptoms, resulting in limited treatment efficacy and poor patient outcomes26. Current therapeutic options, such as surgical resection, liver transplantation, local ablation, and systemic therapies, fall short in effectiveness and tolerability, highlighting the urgent need for a deeper understanding of HCC’s biological mechanisms and the identification of novel therapeutic targets.

This study focuses on the role of glucocorticoids in HCC, specifically examining their associated phenotypic genes and the implications for patient prognosis. Prior research has suggested that relationship between glucocorticoids and hepatocellular carcinoma has a dual nature, which may both promote the development of liver cancer and may be beneficial to liver cancer patients in specific circumstances27,28. Our investigation employs a comprehensive bioinformatics approach, utilizing transcriptomic data analysis to identify DEGs related to glucocorticoids in HCC. The findings will be discussed in terms of their potential to unveil underlying molecular pathways involved in HCC and their relevance in developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

The analysis of DEGs in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has provided valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying this malignancy. In our study, we identified 751 DEGs, with a notable predominance of upregulated genes in tumor samples (470 genes) compared to downregulated genes (281 genes), which highlights the complex regulatory networks involved in HCC progression. Furthermore, pathway analysis using GSEA revealed significant enrichment of pathways such as SPLICEOSOME, RIBOSOME, and DNA_REPLICATION in tumor samples. These findings suggest that alterations in splicing mechanisms and ribosomal biogenesis may play pivotal roles in HCC development. The understanding of these pathways may provide new avenues for targeted therapies, particularly in patients exhibiting specific molecular signatures29,30,31. Moreover, pinpointing potential drug targets within these pathways could aid in creating new treatment strategies to combat resistance and enhance clinical results for HCC patients32.

Consensus clustering has revealed distinct molecular subtypes of HCC, adding complexity to the disease’s characterization. Based on glucocorticoid-related genes, our study delineated two subtypes, with subtype 2 associated with a significantly worse prognosis. Meanwhile, we identified 869 DEGs, with a slight advantage of upregulated genes in subtype 2 (440 genes) compared to downregulated genes (429 genes), which the complexity of glucocorticoid-related genes in the development of HCC. By analyzing DEGs using GO and KEGG, we discovered that genes related to glucocorticoids are involved in biological processes like carboxylic acid catabolic processes, oxidoreductase activity, and PPAR signaling pathway, which in turn facilitate the onset and progression of HCC33,34,35.

Moreover, the analysis of immune cell infiltration revealed significant differences between the identified subtypes, underscoring the potential role of the tumor microenvironment in HCC progression. The presence of effector memory CD8 T cells and Gamma delta T cell in subtype 1 suggests a more favorable immune landscape compared to subtype 2. Some scholars have proposed that the treatment outlook for advanced HCC can be significantly changed by using atezolizumab and bevacizumab together, as they draw peripheral CXCR3 CD8 effector-memory T cells into the tumor36. Meanwhile, recent studies have revealed that γδ T cells have the ability to directly recognize and target HCC cells, making them a compelling choice for immunotherapy37. These findings provide a theoretical basis for individualized immunotherapy.

Next, TMB analysis showed that TP53 had the highest mutation frequency in both groups, followed by CTTNB1, which provides a key criterion for the next step in immunotherapy. Recently, Li C et al. have demonstrated that the removal of onecut2 reduces cell proliferation and enhances apoptosis by means of SKP2-mediated p53 acetylation in HCC38. Classical literature reports a higher mutation rate of CTNNB1 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). β-Catenin inhibitors may have applicability as second-line therapeutic agents for preventing hepatic fibrosis and treating HCC39. At the same time, the assessment of drug sensitivity based on molecular subtypes indicates that subtype 2 patients may exhibit heightened sensitivity to certain chemotherapeutic agents, such as Bortezomib and Dactinomycin. Liao Y et al. found that the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway is involved in bortezomib’s inhibition of HCC40. Hossen et al. demonstrated that dactinomycin, vincristine, and sirolimus exhibit significant therapeutic efficacy in treating HCC41.

Then, by intersecting the DEGs in the TCGA-LIHC samples with those among the subtypes, we obtained 131 intersection genes. Based on these intersection genes, we constructed a prognostic model and ultimately identified 4 genes (KIF2C, CYP2C9, PON1, SPP1) related to the prognosis of patients with HCC, which possess good diagnostic and prognostic value in the progression stage of HCC. Findings suggest that the inhibition of KIF2C heightens the sensitivity of HCC cells to cisplatin by affecting the PI3K/AKT/MAPK signaling pathway42. Moreover, spatial transcriptomics reveals a key mechanism facilitating the interaction between HCC cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts is the SPP1-CD44 signaling axis. Focusing on this pathway could help reduce liver fibrosis and provides new treatment options for managing HCC43. For these four genes, we performed drug sensitivity analysis in DGldb, and found that three prognostic genes (SPP1, PON1, CYP2C9) were detected to be associated with drugs, for example lesinurad and tenoxicam can be used as CYP2C9 targeting drugs, and calcitonin or chondroitin sulfates can specifically target SPP1. There are reports that esinurad esinurad decreases EMT-induced metastasis and resistance to gemcitabine, thereby extending survival in mouse models of pancreatic cancer44.

Finally, We confirmed the expression of the four genes mentioned above using clinical samples, and the findings matched our bioinformatics analysis results, that is, compared with normal liver tissues, KIF2C and SPP1 were highly expressed in tumor tissues, while CYP2C9 and PON1 were low expressed. Moreover, the lower the level of tumor differentiation, the more significant the expression pattern was. Thus, the accuracy of our study is confirmed. The results of this study establish a basis for future investigations into the detailed molecular framework of HCC, which will help in developing effective and tailored therapeutic approaches.

In recent years, significant progress has been made in prognostic model research for HCC. Illustrative examples include the model constructed by Wang et al. based on PANoptosis-related genes and the model developed by Zhu et al. utilising cytotoxic T lymphocyte-evasion genes45,46. These models have enhanced prognostic prediction accuracy to a certain extent. However, certain limitations persist in some models, including single-dataset dependency, inadequate batch effect correction, and limited external validation. In contrast, this study employed integrative analysis of multiple GEO cohorts, implemented rigorous batch effect correction, and adopted an ensemble algorithmic approach. The resultant model demonstrated robust performance (AUC > 0.8) across both internal validation datasets and external validation datasets. Furthermore, differential expression of key genes was experimentally validated, strengthening the model’s translational potential for clinical application.

This study has several inherent limitations. Firstly, although the expression of four glucocorticoid-related genes in HCC was validated through immunohistochemistry, their biological functions and underlying mechanisms in HCC pathogenesis and progression have not been further explored. Furthermore, external validation was confined to the GSE14520 cohort, primarily attributable to the current scarcity of publicly available, high-quality external HCC validation cohorts, which consequently constrains a systematic assessment of the model’s generalizability. In future research, as more high-quality, multicentre HCC clinical cohorts from diverse databases become publicly accessible, we will actively expand the scope of external validation to further enhance the model’s robustness and applicability. Additionally, the limited sample size and absence of comprehensive clinical correlation analyses may potentially impact the interpretation and extrapolation of the findings. Subsequent investigations should prioritise enlarging sample sizes, incorporating validation across multiple cohorts and clinical datasets, and conducting in-depth explorations into the functional mechanisms of key genes to strengthen the scientific validity and clinical utility of this study’s conclusions.

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis that identifies significant glucocorticoid-related genes and their potential implications in hepatocellular carcinoma. By elucidating differentially expressed genes, enriched pathways, and distinct tumor subtypes, we contribute valuable insights into the molecular landscape of HCC. These findings not only pave the way for innovative biomarkers and therapeutic targets but also emphasize the importance of personalized treatment strategies in improving patient outcomes. Upcoming studies need to emphasize experimental validation and the incorporation of clinical data to transform these promising insights into practical strategies for managing HCC.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 12–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21820 (2024).

Gujarathi, R., Klein, J. A., Liao, C. Y. & Pillai, A. The changing demographics and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Liver Dis. 29, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2024.08.001 (2025).

Vogel, A., Meyer, T., Sapisochin, G., Salem, R. & Saborowski, A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 400, 1345–1362. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)01200-4 (2022).

Singal, A. G., Kanwal, F. & Llovet, J. M. Global trends in hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology: implications for screening, prevention and therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 864–884. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00825-3 (2023).

Vutien, P., Kim, N. J. & Nguyen, M. H. The diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review of current practices. Clin. Liver Dis. 29, 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2024.08.007 (2025).

Clarke, S. A. et al. Current challenges and future directions in the assessment of glucocorticoid status. Endocr. Rev. 45, 795–817. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnae016 (2024).

Mitre-Aguilar, I. B. et al. The role of glucocorticoids in breast cancer therapy. Curr. Oncol. 30, 298–314. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30010024 (2022).

Pufall, M. A. Glucocorticoids and cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 872, 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2895-8_14 (2015).

Colaprico, A. et al. TCGAbiolinks: an r/bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e71. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1507 (2016).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102, 15545–15550. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0506580102 (2005).

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell. Syst. 1, 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004 (2015).

Liberzon, A. et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics 27, 1739–1740. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260 (2011).

Gene Ontology Consortium. Going forward. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D1049–1056. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1179 (2015).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics 16, 284–287. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0118 (2012).

Wu, S. et al. Integrated machine learning and Single-Sample gene set enrichment analysis identifies a TGF-Beta signaling pathway derived score in headneck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oncol. 2022 (3140263). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3140263 (2022).

Ru, B. et al. TISIDB: an integrated repository portal for tumor-immune system interactions. Bioinformatics 35, 4200–4202. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz210 (2019).

Mayakonda, A., Lin, D. C., Assenov, Y., Plass, C. & Koeffler, H. P. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28, 1747–1756. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.239244.118 (2018).

Liu, Z. et al. TTN/OBSCN ‘Double-Hit’ predicts favourable prognosis, ‘immune-hot’ subtype and potentially better immunotherapeutic efficacy in colorectal cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25, 3239–3251. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.16393 (2021).

Maeser, D., Gruener, R. F. & Huang, R. S. OncoPredict: an R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief. Bioinform. 22 https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab260 (2021).

Yang, W. et al. Genomics of drug sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D955–961. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1111 (2013).

Brinkman, E. K., Chen, T., Amendola, M. & van Steensel, B. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e168. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku936 (2014).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 (2011).

Cannon, M. et al. DGIdb 5.0: rebuilding the drug-gene interaction database for precision medicine and drug discovery platforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D1227–d1235. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad1040 (2024).

Wang, Y. & Deng, B. Hepatocellular carcinoma: molecular mechanism, targeted therapy, and biomarkers. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 42, 629–652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-023-10084-4 (2023).

Orci, L. A., Toso, C., Mentha, G., Morel, P. & Majno, P. E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of perioperative steroids on ischaemia-reperfusion injury and surgical stress response in patients undergoing liver resection. Br. J. Surg. 100, 600–609. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9035 (2013).

Papadakos, S. P. et al. Exploring the role of GITR/GITRL signaling: from liver disease to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16142609 (2024).

Li, B. et al. SNRPB2 in the pan-cancer landscape: A bioinformatics exploration and validation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. Signal 124, 111445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2024.111445 (2024).

Liu, G. et al. Elucidating the prognostic and therapeutic significance of TOP2A in various malignancies. Cancer Genet. 288–289, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cancergen.2024.10.005 (2024).

Su, Q. et al. Ribosomal proteins in hepatocellular carcinoma: mysterious but promising. Cell. Biosci. 14, 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-024-01316-3 (2024).

Akram, F. et al. The journey of antibody-drug conjugates for revolutionizing cancer therapy: a review. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 117, 118010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2024.118010 (2025).

Böhmová, A. et al. Untargeted metabolomics of blood plasma samples of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 248, 116263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2024.116263 (2024).

Hsiao, Y. F. et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence, independent of folate and glutathione-related antioxidant enzymes: a follow-up study. Nutr. Res. 128, 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2024.06.010 (2024).

Mai, Y., Ji, Z., Tan, Y., Feng, L. & Qin, J. BIRC5 knockdown ameliorates hepatocellular carcinoma progression via regulating PPARγ pathway and Cuproptosis. Discov Oncol. 15, 706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-024-01592-y (2024).

Cappuyns, S. et al. PD-1(-) CD45RA(+) effector-memory CD8 T cells and CXCL10(+) macrophages are associated with response to Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 14, 7825. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43381-1 (2023).

Papadakos, S. P. et al. γδ T cells: A game changer in the future of hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25031381 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Knockout of onecut2 inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of tumor cells through SKP2-mediated p53 acetylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 81, 469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-024-05518-3 (2024).

Katoh, M. Multi-layered prevention and treatment of chronic inflammation, organ fibrosis and cancer associated with canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling activation (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 42, 713–725. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2018.3689 (2018).

Liao, Y. et al. Bortezomib inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma via the Hippo-Yes-associated protein signalling pathway. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 132, 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.13832 (2023).

Hossen, M. A. et al. Identification of most representative hub-genes for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapies of hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 13, 32. https://doi.org/10.21037/cco-23-151 (2024).

Wei, S. et al. Silencing of KIF2C enhances the sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to cisplatin through regulating the PI3K/AKT/MAPK signaling pathway. Anticancer Drugs. 35, 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1097/cad.0000000000001563 (2024).

Tong, W. et al. Spatial transcriptomics reveals tumor-derived SPP1 induces fibroblast chemotaxis and activation in the hepatocellular carcinoma microenvironment. J. Transl Med. 22, 840. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05613-w (2024).

Nayak, D. et al. EMT alterations in the solute carrier landscape uncover SLC22A10/A15 imposed vulnerabilities in pancreatic cancer. iScience 25, 104193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.104193 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. PANoptosis-related genes in the prognosis and immune landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunol. Res. 73 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-025-09603-y (2025).

Zhu, Q. et al. Development of a novel prognostic signature based on cytotoxic T lymphocyte-evasion genes for hepatocellular carcinoma patient management. Discov. Oncol. 16, 144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-025-01909-5 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AW and JFF planned the study, XY and SJL collected the literatures, YRF and TJ collected and analyzed the data, AW and JFF composed the manuscript, and all the other co-authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, A., Yin, X., Li, S. et al. The role of glucocorticoids in hepatocellular carcinoma through integrated bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation. Sci Rep 15, 27094 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12839-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12839-1