Abstract

Patient-reported symptoms provide valuable insights into patient experiences and can enhance healthcare quality; however, effectively capturing them remains challenging. Although natural language processing (NLP) models have been developed to extract adverse events and symptoms from medical records written by healthcare professionals, limited studies have focused on models designed for patient-generated narratives. This study developed an NLP model to extract patient-reported symptoms from pharmaceutical care records and validated its effectiveness in analyzing diverse patient-generated narratives. The target dataset comprised “Subjective” sections of pharmaceutical care records created by community pharmacists for patients prescribed anticancer drugs. Two annotation guidelines were applied to develop robust ground-truth data, which was used to develop and evaluate a new transformer-based named entity recognition model. Model performance was compared with that of an existing tool for Japanese clinical texts and tested on external patient-generated blog data to evaluate generalizability. The newly developed BERT-CRF model significantly outperformed the existing model, achieving an F1 score > 0.8 on pharmaceutical care records and extracting > 98% of physical symptom entries from patient blogs, with a 20% improvement over the existing tool. These findings highlight the importance of fine-tuning models using patient-specific narrative data to capture nuanced and colloquial symptom expressions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients’ daily remarks concerning their treatment and the reports in their electronic health records (EHRs) after interactions with healthcare providers contain important information that cannot be solely represented using numerical data, such as laboratory test values1. These reports capture the nuances of individual patient experiences and the concerns expressed by patients and their relatives. Collecting and using long-term patient health data through such patient-oriented narratives is critical for enhancing healthcare standards and, ultimately, patient quality of life2,3,4,5,6.

Studies have demonstrated the importance of these data in clinical practice. Moreover, several studies have suggested that physicians may underestimate the frequency, severity, and timing of adverse events (AEs)7,8,9. Forbush et al. highlighted the significance of extracting symptoms from free text in medical documents, reporting that the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes captured only 36% of patient self-reported symptoms from the clinical texts of both inpatients and outpatients. This finding underscores variations in symptom description and the critical need for effective symptom extraction from free-text sources10.

Technological advancements in natural language processing (NLP) have facilitated information extraction from clinical texts based on patients’ subjective data11,12,13,14,15. NLP offers a solution to manual review limitations, which are both labor-intensive and prone to variability. NLP research has progressively expanded beyond EHRs to encompass patient narratives found in blogs, which often contain colloquial expressions not typically used by healthcare professionals16,17,18,19. However, challenges persist, including limited data availability—which makes it difficult to collect sufficient data required to build high-performing models from scratch—the inherent difficulty in constructing robust extraction models due to noise unrelated to symptoms in patient narratives, and the challenge of integrating these narratives with detailed patient medical data for comprehensive analysis15,20.

Consequently, we concentrated on complaints recorded by healthcare professionals during their interactions with patients. These summaries capture patients’ unique perspectives on their symptoms and concerns, combined with the observations of healthcare professionals15. Applying NLP technologies to these summaries facilitates extracting various symptom expressions from patient perspectives. Furthermore, these summaries serve as valuable training data for NLP models, addressing challenges in patient narrative research.

In particular, pharmaceutical care records documented by pharmacists include recommendations to physicians and side effect monitoring to ensure appropriate medication use. Community pharmacists maintain long-term follow-up information for outpatients, often recorded in the SOAP format. The “Subjective (S)” section of these records captures patients’ chief complaints21, providing a valuable source for extracting symptom expressions conveyed in colloquial language.

This study aimed to develop an NLP model optimized for extracting patient-reported symptoms from written subjective records documented by healthcare professionals. To this end, the study was structured as follows:

Initially, the performance of an existing NLP model—originally developed for symptom extraction from clinical documents—was assessed in the context of “Subjective” records. Two annotation strategies were employed: one based on established clinical documentation guidelines reflecting a healthcare provider’s perspective, and another based on a newly developed guideline tailored to capture patient-reported symptoms more effectively. This comparative evaluation highlighted the limitations of conventional models when applied to patient-centered, colloquial expressions. Subsequently, we developed a new BERT-CRF-based model trained on these patient-oriented annotations and benchmarked its performance against the conventional approach. Finally, we examined the model’s adaptability to different narrative sources, including professional documentation and patient-generated blogs. By constructing a domain-specific dataset and patient-oriented annotation guidelines, this study offers a practical approach for integrating patient perspectives into clinical NLP systems, contributing to the scalable development of patient-inclusive digital health tools.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee for research involving human subjects of the Keio University Faculty of Pharmacy (Approval No. 240118-2, 240618-1).

Overview

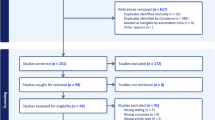

We investigated NLP methods for extracting symptoms and AEs from the clinical texts in the “Subjective” section of pharmaceutical care records documented by community pharmacists. First, we evaluated the performance of an existing general-purpose model designed for Japanese clinical documents using the subjective data. This evaluation was conducted using ground-truth data created based on two annotation guidelines: patient-centric (PCA) and clinician-centric (CCA) annotations (Fig. 1a). Second, we developed a new Named Entity Recognition (NER) model using CCA data and evaluated its performance (Fig. 1b). As an external validation dataset, we assessed the utility of the newly developed model on patient-authored blogs (Fig. 1c).

Flow of NLP model construction/evaluation. (a) CCA used an existing guideline modified for pharmaceutical care records, whereas PCA employed a guideline adjusted to align with patient-centered expressions. The model predicts entities corresponding to patient symptoms in the text and their factuality (either positive or negative). These predictions are then compared with the annotation results. (b) The data created under PCA was divided into training and test sets using 10-fold cross-validation, and the pre-trained BERT and LUKE models were fine-tuned. The average performance on the test data was used to evaluate model performance. (c) The applicability of the newly developed model was evaluated by comparing its predictions of actual symptoms with those of an existing model on patient-authored blogs.

Data collection

Pharmaceutical care records

A total of 2,180,902 pharmaceutical care records of 291,150 patients created at Nakajima Pharmacy, a community pharmacy network primarily based in Hokkaido, Japan, between April 1, 2020, and December 31, 2021, were reviewed. The analysis focused on “Subjective” records, which contain patient statements. To enrich the dataset with records likely to contain AE descriptions, we targeted patients who had been prescribed at least one anticancer drug. Filtering was conducted based on YJ codes, which are standardized drug classification codes used in Japan. Specifically, we extracted records containing drugs with YJ codes beginning with “42,” which correspond to anticancer drugs.

To focus on patient-reported complaints, we extracted only the “Subjective” sections of the records, excluding other sections such as “Objective,” “Assessment,” and “Plan.” Subsequently, to ensure feasibility for manual annotation, we limited the dataset to a recent 3-month period (October to December 2020). Among the 50 pharmacies that dispensed anticancer drugs during this period, we stratified the facilities by size and randomly selected records from 11 pharmacies. In total, 1054 records were randomly selected, corresponding to 314 unique patients. The data extraction flow is summarized in Supplementary Fig. S1 online.

Patient blog articles

Additionally, we evaluated the newly developed model by validating its applicability to patient complaint data from different sources, using blog posts personally written by patients. The data source comprised blog articles collected between March 2008 and November 2014 from the Japanese web community “Life Palette”, a patient support website where users share illness experiences and connect through blogs and community diaries.

Explanation of the existing model and annotation rules

We defined NER as the primary NLP task and manually annotated the dataset using two guidelines. Both annotation approaches focused on the symptom tag indicating symptoms or AEs. This tag was based on the disease tags from MedNER-CR-JA22. MedNER-CR-JA is a pre-trained NER model developed by the Nara Institute of Science and Technology to extract medical entities from Japanese clinical texts. It adopts bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) and was trained on annotated JA case reports23. The model was designed for medical information extraction and supports various tags, including symptoms, drug names, dosages, and anatomical locations, each with detailed attribute types (see Supplemental Table S1). This study specifically focused on disease tags to evaluate model applicability in identifying AE-related expressions in patient complaints. This model can also perform detailed positive or negative classification of symptom expressions.

The first annotation method used was the CCA, which follows conventional NER guidelines for clinical notes24, adjusting annotations to align with the expected MedNER-CR-JA outputs22. We added a detailed description of the CCA guideline in the Supplemental Information (Sect. 1), including tag definitions and special cases derived from annotator discussions. For example, entities such as “no change in symptoms,” colloquial expressions such as “not sleeping well,” and medication-controlled phrases (e.g., “constipation is fine with Lubiprostone”) are treated according to specific rules. Ambiguity in expressions or the presence of metaphorical phrases is also addressed systematically.

The second method, PCA, focuses on patient expressions relevant to AE monitoring and is designed for subjective records. Consequently, a custom guideline was developed (see Supplemental Information Sect. 2). As with CCA, this PCA guideline includes tag definitions and itemized special instructions based on annotator discussions. It defines symptom-tagging rules for both medical and colloquial expressions and includes logic for assigning attributes (positive, negative, suspicious, etc.) to laboratory values, drug references, and temporal language. Examples are provided for difficult cases, such as vague statements, symptom control, and phrases involving the past tense or metaphor. Furthermore, for detailed error analyses, symptoms tagged with the symptom label were categorized based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) ver.5.0, encompassing categories such as general disorders (e.g, fever, weight gain/loss), psychiatric and neurological disorders and gastrointestinal, hepatic, and renal disorders25 (see Supplemental Table S2).

In both annotation approaches, annotation reliability was assessed using 100 randomly selected texts from the dataset. Three researchers with advanced pharmacological knowledge (S. Y., Y. Y., and K. S.) conducted test annotations and assessed label consistency. Agreement level was measured using the Fleiss κ coefficient, which evaluates the agreement rate among the three annotators26,27. After assessing the agreement, three researchers (S. Y., Y. Y., and K. S.) annotated the entire dataset.

Model development

As shown in Fig. 1b, new NER models were developed using PCA data. These models used pre-trained BERT and language understanding with knowledge-based embedding (LUKE) architectures28. Fine-tuning was conducted using PCA-annotated data to adapt the models to patient complaints, which often contain colloquial and medical terms.

In general, recent large language models, such as BERT and LUKE, are trained in two stages. In the first stage, self-supervised learning is conducted on large corpora, such as Wikipedia, to develop a general language understanding, resulting in a pre-trained model. In the second stage, fine-tuning is performed using a small amount of labeled data to adapt the model to the target task. For this study, we used a pre-trained BERT model from the Inui-Suzuki Laboratory at Tohoku University (cl-tohoku/bert-base-japanese-v3) and the Japanese version of LUKE, developed by Studio Ousia (studio-ousia/luke-japanese-base), which was fine-tuned using data generated through PCA29,30.

For fine-tuning, we added a fully connected layer to the final layer of each model. LUKE only required the addition of a fully connected layer, whereas the output from BERT was fed into the conditional random field (CRF) layer. CRF is a probabilistic model that solves sequence labeling tasks and is widely known to enhance model performance when added to the final layer of BERT in both English and Japanese31,32,33. During preprocessing, the target data were tokenized using each model’s tokenizer and subsequently fed into the pre-trained models with a maximum input length of 512 tokens, which is the model’s input limit. Fine-tuning was conducted using an NVIDIA RTX™ 4500 Ada with the following parameters: cross-entropy loss as the loss function, Softmax as the activation function, a batch size of 32, a learning rate of 10− 4, and 5 epochs.

Performance evaluations and metrics

The models were evaluated as shown in Fig. 2. Model performance was evaluated using two methods: position and exact match. In the position match method, a prediction is considered correct when the tag positions in the text match between the model predictions and the annotated data. Exact match requires both the position and the attribute to match for a prediction to be considered correct. Therefore, in exact matching, evaluation metrics were calculated separately for each attribute. In both methods, performance was assessed in terms of precision, recall, and F1 scores. The calculation methods for these metrics are as follows:

In the MedNER-CR-JA evaluation, the correct tags for named entities created in both CCA and PCA were compared with those predicted by MedNER-CR-JA. For the newly created model, the target data were split into 90% training and 10% test data. Subsequently, the named entity extractor was evaluated using 10-fold cross-validation. The evaluation metrics were the same as those previously described and were calculated using the average cross-validation results to assess model performance and compare it with that of the existing model (MedNER-CR-JA).

Example of evaluation process. CCA and PCA results were compared with the model outputs. In the position match method, attributes were considered correct even if mismatched, whereas in the exact match method, they were marked as incorrect. CCA, Clinician-centric annotation; PCA, Patient-centric annotation.

Applicability check to other patient narratives

We used patient complaint data obtained from blogs on LifePalette to validate the effectiveness of the newly developed model. For the actual evaluation data, we selected 1,138 entries labeled “Physical” from 2,272 entries previously tagged with five different labels related to complaints of patients with breast cancer in a previous study by Watanabe et al.34. Entries labeled “Physical,” examined from patient perspectives in the PCA of this study, were used to extract physical changes that cause distress in patients with breast cancer. Moreover, this concept largely overlaps with general symptom tags for patients with cancer. In this study, we input a dataset of 2,272 entries on complaints from patients with breast cancer into both MedNER-CR-JA and the newly developed models. Thereafter, we cross-referenced clinical texts assigned a positive symptom tag with those labeled “Physical” to evaluate the ability of the model to extract clinically important AEs from diverse data sources.

Results

Summary of collected data

From 2,180,902 pharmaceutical care records, 1,054 subjective descriptions were extracted (Fig. 1a). The average number of words per text in the dataset was 41.8, with a median of 32.0 (range: 2–265). Details of the dataset features are shown in Supplementary Table S3 online.

Characteristics of data annotated by two approaches

Table 1 shows the number of tags by attribute for the MedNER-CR-JA predictions and the two annotation methods (PCA and CCA). PCA yielded a higher frequency of assigned tags across all attributes than both MedNER-CR-JA prediction and CCA. MedNER-CR-JA extracted 1306 symptom tags, majorly with positive or negative attributes, consistent with the annotation data. For ‘suspicious’ attributes, fewer than 10 expressions were observed across all results. Annotator agreement, assessed via the Fleiss κ coefficient, was 0.87 for CCA and 0.78 for PCA, indicating high reliability.

Table 2 shows specific annotation examples. Characteristic expressions in patient complaints included various ways of expressing a single medical term, such as onomatopoeic and metaphorical expressions. The model tended to make extraction errors with such expressions. However, the model accurately extracted medical terms when described in noun form.

In the PCA, 26% of symptom tag entries, such as “no change in condition” or “no side effects”–were categorized as “Unclassified” based on the aggregated results classified according to CTCAE ver. 5.0. This finding probably reflects the nature of pharmaceutical care records, where many entries pertain to pharmacists confirming patient symptoms. Figure 3 presents a breakdown of the results, excluding the unclassified category. Gastrointestinal disorders and pain accounted for > 10% of all AEs, with other frequently occurring AEs, including skin, subcutaneous tissue, and respiratory system disorders. PCA revealed a wide variety of AEs related to both administered drugs and patients’ underlying conditions.

AE aggregation in PCA. In PCA, AE classifications were established based on CTCAE ver.5.0, and theresults were aggregated. Detailed AE classifications are provided in Supplemental Table S3. PCA, Patient-centric annotation; AE, Adverse event.

Existing model performance for pharmaceutical care records

In the MedNER-CR-JA performance evaluation, F1 scores varied by attribute, ranging from 0.00 to > 0.65 (Table 3).

For both CCA and PCA, the F1 scores for positive and negative attributes were approximately 0.40 and 0.60, respectively, indicating higher extraction performance for attributes with more assigned tags. In both evaluation methods, recall was significantly lower in PCA than in CCA, while precision tended to increase. Consequently, the F1 scores decreased for PCA.

Newly developed model performances

Table 4 shows the performance of the newly trained models (BERT-CRF and LUKE) compared with that of MedNER-CR-JA in PCA.

Although exceptions were found, such as LUKE’s F1 score for the suspicious tag being over 0.1 lower than that of MedNER-CR-JA, the newly created models generally demonstrated higher extraction performance. BERT-CRF outperformed LUKE and MedNER-CR-JA, with an overall F1 score exceeding 0.8. BERT-CRF demonstrated better precision and recall than existing models, especially for positive symptom tags. LUKE showed slightly lower performance for certain attributes, such as “suspicious,” but still outperformed MedNER-CR-JA in most categories. Notably, as the new model scores are based on 10-fold cross-validation averages, direct comparison with MedNER-CR-JA, which is evaluated on the full dataset, is challenging.

Evaluation of the new model’s applicability

In the usability evaluation of patient blog data, the newly constructed BERT-CRF model assigned a positive tag to 2,055 of the 2,272 entries in the evaluation dataset. Among the 1,138 entries labeled “Physical,” 1,117 received a positive tag, resulting in over 98% extraction (Fig. 4). Contrarily, MedNER-CR-JA assigned a positive tag to 899 of the 1,138 entries, with approximately 20% lower coverage compared with that of the new model.

Venn diagram of texts with “Physical” concern labels and texts with positive tags assigned. The “Physical” label was assigned by researchers with medical knowledge to all blog posts where patients with breast cancer expressed physical pain. This Venn diagram shows the proportion of posts among the 1,138 labeled “Physical” of the 2,272 posts where the NLP models assigned a positive symptom tag.

Discussion

Principal findings

This study addressed the challenge of extracting patient-reported symptoms from subjective records in pharmaceutical care records documented by community pharmacists. By employing two annotation methods, we demonstrated that these records contained rich information on patient-reported symptoms and AEs. A transformer-based model fine-tuned on these annotations outperformed MedNER-CR-JA, a general-purpose NER model for Japanese medical texts, in extracting numerous symptom entities from complaints of outpatients with cancer. The results highlight the importance of fine-tuning models for domain-specific data to improve extraction performance. In addition, the usability evaluation on blog posts by patients with breast cancer confirmed that this model could be generalized to other patient-generated narrative texts, highlighting its broader applicability.

This study is the first to focus on patient concerns expressed in daily life contexts outside hospital settings and to evaluate the potential of NLP technologies for extracting clinically important information. These results emphasize the importance of tailoring models to the linguistic characteristics of patient-centered data, which often include informal, ambiguous, or metaphorical language not well captured by conventional tools. Additionally, the model’s performance on patient-authored blog posts confirmed its ability to generalize to other types of patient-generated narratives, highlighting its robustness across diverse real-world language sources.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to develop a domain-specific NER model for patient-reported symptoms described in Japanese pharmaceutical care records and to evaluate its generalizability to non-clinical, patient-generated narratives.

These findings suggest that NLP models trained on patient narratives from community pharmacy settings can effectively extract meaningful expressions and may serve as a foundation for models that incorporate patient perspectives, with significant implications for enhancing patient-centered care systems.

Annotated data analysis

The subjective records used in this study captured the patient-reported symptoms from individual prescribed anticancer drugs. Given the high AE incidence associated with anticancer drugs, healthcare professionals play an essential role in carefully documenting patient complaints. The PCA annotations, which accounted for 84.7% of the records, captured a wider range of symptom-related expressions than the 61.5% extraction rate of MedNER-CR-JA. In PCA, these records often included symptoms described in casual or colloquial language, such as “frequent trips to the bathroom,” “can’t go shopping,” and “get tired after work,” indicating that community pharmacists documented patient-reported symptoms from patient perspectives, significantly enriching the dataset. PCA revealed chronic symptoms and daily life challenges often overlooked in clinical settings, underscoring the potential of subjective records to capture nuanced patient narratives critical to patient-centered care.

MedNER-CR-JA performance

During the performance evaluation of pharmaceutical care records using MedNER-CR-JA, we used two evaluation methods: exact and position match. For the NER model in extracting all symptom tags, the F1 scores were 0.62 for CCA and 0.44 for PCA in exact match, while in position match, they were 0.71 and 0.52, respectively, showing a difference of approximately 0.1 between CCA and PCA. Exact match tended to yield lower scores owing to stricter criteria. PCA showed lower recall and F1 scores compared with CCA, with similar precision. The lower recall in PCA may be due to the double number of tags compared with CCA. Specifically, 60–70% of the negative attributes tagged in PCA included expressions such as “no change in symptoms,” which were not tagged in CCA, likely contributing to the significant recall drop in PCA. Detailed error analysis results for other patient-reported symptoms tagged in CCA but not in the NER model predictions are shown in Supplemental Table S4 online.

We compared MedNER-CR-JA performance with that of previous studies using similar concepts. Examples of large-scale NLP system applications on similar text types include studies by Ohno et al. and Mashima et al., which focused on hospital medication records and analysis of progress notes of gastroenterology inpatients at a university hospital, respectively35,36. Both studies used MedNER-J, the predecessor of the model used in this study, for symptom extraction tasks37. Ohno et al. applied the NER system and confirmed an F1 score of 0.46 for symptom extraction from subjective records, similar to the F1 score for the PCA symptom tag in this study. The F1 score was lower in subjective records, where patient-reported symptoms were described, compared with assessment and objective records containing pharmacist evaluations and objective information, indicating that further system training is needed to accurately capture patient language35. Mashima et al. conducted a similar study using MedNER-J, with gastroenterology specialists from the Japanese Society of Gastroenterology (YM) setting the gold standard36. The study achieved κ coefficients in the 0.6 range for symptom extraction accuracy in progress notes written by physicians or nurses. Although direct comparison with our study is challenging, the F1 score of 0.6–0.7 in CCA data, created by experts, aligns well with these previous results. These findings suggest that MedNER-CR-JA can extract patient-reported symptoms to some extent; however, further training is required to accurately capture patient language nuances.

Performance of the newly trained NER models

We used the average scores from the ten-fold cross-validation to evaluate the newly trained model. Therefore, a direct comparison with MedNER-CR-JA performance across all 1,054 entries is challenging. However, the newly trained BERT-CRF and LUKE models performed better than MedNER-CR-JA in extracting patient-reported symptoms from pharmaceutical records. Notably, BERT-CRF outperformed LUKE, achieving an F1 score of > 0.8 for the symptom tag. This improvement in precision for positive and negative tags likely stems from the model’s ability to extract patient-reported symptoms, such as pain and fatigue, and pharmaceutical care record-specific phrases, such as “no symptoms.” The difference in the pretraining data may explain why BERT outperformed LUKE, as LUKE was pre-trained solely on Wikipedia data, while BERT used both Wikipedia and the CC-100 datasets. Additionally, LUKE pretraining included an entity-related task, which may have led to overfitting of the fine-tuning data. Although 10-fold cross-validation was used to evaluate generalizability, the small dataset size (approximately 1,000 records) may have contributed to overfitting.

Applicability of the newly trained NER models to real patient narratives

The new BERT-CRF model was applied to patient-generated data to further evaluate model applicability, particularly a dataset of blogs written by patients with breast cancer. The results were impressive: the model extracted > 98% (1,117 of 1,138) of entries labeled “Physical,” significantly surpassing the 79% extraction rate of MedNER-CR-JA. This 20% improvement underscores the importance of fine-tuning with specific patient narrative data to capture a broader range of physical AEs as personally perceived and described by patients. The 21 texts missed by BERT-CRF contained expressions where “Physical” was difficult to assess without additional context or annotations from multiple annotators. Despite these limitations, this external validation demonstrated that the model has a strong generalizability to unstructured patient-generated narratives, highlighting its potential applicability across diverse healthcare settings.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, the subjective records included transcriptions of patient-reported symptoms by pharmacists, potentially introducing selection bias or supplementary information not originally reported by patients, which may have affected model performance. Second, the study focused on pharmacies within a single chain, which may limit generalizability to other settings. Third, the absence of detailed medical information, such as treatment details or diagnoses from external healthcare providers, limits the contextual understanding of patient-reported symptoms.

Future directions

Future studies should explore NLP model application to a broader range of patient narratives across diverse healthcare settings. Larger datasets and additional fine-tuning with more diverse patient-generated complaints, such as hospital and homecare records, are necessary to further enhance model generalizability. Ultimately, integrating such models into patient-centered systems that record and share patient perspectives with healthcare providers could improve AE monitoring, appropriate medication use, and overall quality of care.

This study developed and evaluated transformer-based NER models for extracting patient-reported symptoms from subjective records in pharmaceutical care settings, outperforming MedNER-CR-JA, a general-purpose model for Japanese medical texts. By fine-tuning the models with patient-specific data, we successfully captured a wider range of patient-reported expressions, including casual and colloquial language, which existing models often miss. These findings highlight the potential of NLP technologies to support patient-centered care by accurately extracting clinically relevant information from patient narratives. The evaluation of patient blogs further demonstrated the adaptability of the model to real-world patient-generated data.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. The fine-tuned BERT-CRF model (named Patient-centered NER-PhR-JA) is available at our repository: https://github.com/keioDI/Patient-centered-NER-PhR-JA.

References

Murphy, J. W., Choi, J. M. & Cadeiras, M. The role of clinical records in narrative medicine: A discourse of message. Pers. Med. J. 20, 103–108 (2017).

Clark, P. G. Narrative in interprofessional education and practice: implications for professional identity, provider-patient communication and teamwork. J. Interprof Care. 28, 34–39 (2014).

Ancker, J. S. et al. Use of an electronic patient portal among disadvantaged populations. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 26, 1117–1123 (2011).

Basch, E. et al. Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 101, 1624–1632 (2009).

Grob, R. et al. What words convey: the potential for patient narratives to inform quality improvement. Milbank Q. 97, 176–227 (2019).

Getchell, L. E. et al. Storytelling for impact: the creation of a storytelling program for patient partners in research. Res. Involv. Engagem. 9, 57 (2023).

Liu, L. et al. Clinicians versus patients subjective adverse events assessment: based on patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). Qual. Life Res. 29, 3009–3015 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Clinical information extraction applications: A literature review. J. Biomed. Inf. 77, 34–49 (2018).

Fromme, E. K., Eilers, K. M., Mori, M., Hsieh, Y. C. & Beer, T. M. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life questionnaire C30. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 3485–3490 (2004).

Forbush, T. B. et al. ‘Sitting on pins and needles’: Characterization of symptom descriptions in clinical notes. AMIA Jt Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. (Transl. Summits, A. Jt.). 2013, 67–71 (2013).

Dreisbach, C., Koleck, T. A., Bourne, P. E. & Bakken, S. A systematic review of natural Language processing and text mining of symptoms from electronic patient-authored text data. Int. J. Med. Inf. 125, 37–46 (2019).

Chan, L. et al. Natural language processing of electronic health records is superior to billing codes to identify symptom burden in Hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 97, 383–392 (2020).

Guevara, M. et al. Large Language models to identify social determinants of health in electronic health records. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 6 (2024).

Koleck, T. A., Dreisbach, C., Bourne, P. E. & Bakken, S. Natural language processing of symptoms documented in free-text narratives of electronic health records: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 26, 364–379 (2019).

Sezgin, E., Hussain, S. A., Rust, S. & Huang, Y. Extracting medical information from free-text and unstructured patient-generated health data using natural language processing methods: feasibility study with real-world data. JMIR Form. Res. 7, e43014 (2023).

Hua, Y. et al. Streamlining social media information retrieval for public health research with deep learning. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 31, 1569–1577 (2024).

Sarker, A. et al. Self-reported COVID-19 symptoms on twitter: an analysis and a research resource. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 27, 1310–1315 (2020).

Watabe, S. et al. Exploring a method for extracting concerns of multiple breast cancer patients in the domain of patient narratives using BERT and its optimization by domain adaptation using masked Language modeling. PLoS One. 19, e0305496 (2024).

Li, C., Weng, Y., Zhang, Y. & Wang, B. A systematic review of application progress on machine learning-based natural Language processing in breast cancer over the past 5 years. Diagnostics (Basel Switzerland). 13, 537 (2023).

Nishioka, S. et al. Adverse event signal detection using patients’ concerns in pharmaceutical care records: evaluation of deep learning models. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e55794 (2024).

Podder, V., Lew, V., Ghassemzadeh, S. & Notes, S. O. A. P. (2024).

Nishiyama, T. et al. NAISTSOC at the NTCIR-16 real-MedNLP task. 20, 330–333 (2022).

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K. & Google, K. T. & language, A.I. BERT: Pretraining of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Naacl-Hlt 2019, 4171–4186 (2019).

Yada, S. et al. Medical/clinical text annotation guidelines, (2021). https://sociocom.naist.jp/real-mednlp/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2021/08/PRISM_Annotation_Guidelines-v8-English.pdf.

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0.

Artstein, R. & Poesio, M. Inter-coder annotation agreement for computational linguistics.pdf. Comput. Linguist. 34, 555–596 (2008).

Fleiss, J. L. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 76, 378–382 (1971).

Yamada, I. LUKE: Deep contextualized entity representations with in EMNLP 2020. Conf. Empir. Methods Nat. Lang. Process. Proc., 6442–6454 (2020).

cl-Tohoku/Bert-Base-Japanese-v3. https://huggingface.co/tohoku-nlp/bert-base-japanese-v3.

studio-ousia/luke. https://github.com/studio-ousia/luke.

Souza, F., Nogueira, R. & Lotufo, R. Portuguese Named Entity Recognition Using BERT-CRF (2019).

Si, Y., Wang, J., Xu, H. & Roberts, K. Enhancing clinical concept extraction with contextual embeddings. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 26, 1297–1304 (2019).

Goino, T., Yokohama, H. & Bert, T. Named Entity Recognition from Medical Documents by Fine-Tuning (2021).

Watanabe, T. et al. Extracting multiple worries from breast cancer patient blogs using multilabel classification with the natural Language processing model bidirectional encoder representations from transformers: infodemiology study of blogs. JMIR Cancer. 8, e37840 (2022).

Ohno, Y. et al. Using the natural Language processing system medical named entity recognition-Japanese to analyze pharmaceutical care records: natural Language processing analysis. JMIR Form. Res. 8, e55798 (2024).

Mashima, Y., Tanigawa, M. & Yokoi, H. Information heterogeneity between progress notes by physicians and nurses for inpatients with digestive system diseases. Sci. Rep. 14, 7656 (2024).

Ujiie, S. & Yada, S. MedNER-J. https://github.com/sociocom/MedNER-J.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 21H03170 and JST, CREST Grant Number JPMJCR22N1, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W. and S.H. designed this study. S.W. retrieved the subjective records of patients with cancer from a data source for the application of natural language processing (NLP) models and conducted all NLP experiments. Y.Y., K.S., and S.Y. conducted annotation and provided advice on data handling. M.S. and R.T. provided pharmaceutical records at their community pharmacies along with advice on how to use and interpret them. S.Y. and E.A. supervised the NLP research as specialists. S.H. supervised the study. S.W. drafted and finalized the manuscript. Y.Y. assisted in writing parts of the manuscript. All the authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Mitsuhiro Someya, and Ryoo Taniguchi are employees of Nakajima Pharmacy and provided the pharmaceutical care records used in this study. Mitsuhiro Someya and Ryoo Taniguchi are employees of Nakajima Pharmacy and provided the pharmaceutical care records used in this study. Satoshi Watabe, Yuki Yanagisawa, Kyoko Sayama, Sakura Yokoyama, Shuntaro Yada, Eiji Aramaki, Hayato Kizaki, Masami Tsuchiya, Shungo Imai, and Satoko Hori declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee for research involving human subjects of the Keio University Faculty of Pharmacy (approval No. 240118-2, 240618-1). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects issued by the Japanese government and the Declaration of Helsinki. The data used in this study consisted solely of anonymized, existing information from medication records collected at Nakajima Pharmacy and did not include any human-derived specimens. Informed consent specific to this study was waived by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects of the Keio University Faculty of Pharmacy, due to the retrospective and non-interventional nature of the study. However, to respect individual autonomy, notices about the study were posted in each participating Nakajima Pharmacy branch and on its official website, allowing patients to opt out of the use of their anonymized data. A similar opportunity to opt out was also provided to the pharmacists involved.

Informed consent

The requirement for informed consent for study participation and publication was waived by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects of the Keio University Faculty of Pharmacy, due to the retrospective and non-interventional nature of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Watabe, S., Yanagisawa, Y., Sayama, K. et al. A patient-centered approach to developing and validating a natural language processing model for extracting patient-reported symptoms. Sci Rep 15, 27652 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12845-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12845-3