Abstract

Trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) has a high incidence in patients with severe trauma. Patients who develop TIC usually have a poor prognosis, characterised by increased organ dysfunction, susceptibility to sepsis, and high mortality. Nonetheless, there are still few studies specifically focusing on postoperative TIC in severely traumatic patients. Therefore, the aim of this study was to construct a machine learning model for early identification of people at high risk of postoperative TIC. This retrospective analysis included data of severe trauma patients undergoing surgical treatment from January 2013 to February 2023 across four hospitals in China. Data of one hospital (n = 1204) was used for the development dataset, while other three hospitals contributed to the external validation dataset (n = 863). The study employed various machine learning algorithms, including random forests, logistic regression, gradient boosting decision trees, support vector machines, backpropagation artificial neural networks, extreme gradient boosting, and naïve Bayes. Model performance was estimated on the basis of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve. In the internal cross-validation dataset, Shapley’s additive interpretation was applied to the model with the largest area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. TIC occurred in 25.4% (306/1204) and 2.9% (25/863) of patients in the developing and external validation set, respectively. Among the models evaluated, the Random Forest model demonstrated the highest performance, achieving an area under the curve of 0.82 for the test cohort and 0.73 for the external validation cohort. The findings suggest that machine learning models can effectively identify severely traumatized patients at a higher risk of postoperative trauma-induced coagulopathy. Utilizing machine learning may enhance clinical decision-making and improve management strategies for postoperative coagulation issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trauma Induce Coagulopathy (TIC), a coagulation disorder that occurs after trauma, is a common complication of trauma. Its pathophysiology involves a complex interplay of endothelial dysfunction, inflammatory responses, and immune system mediators1. Furthermore, external factors such as hemodilution and hypothermia exacerbate its progression2.

The incidence of TIC, although varying depending on the study population and diagnostic criteria, is overall significantly higher with increasing trauma severity3. Increases significantly with increasing trauma severity, to approximately 25% in severely traumatized patients4. Trauma patients with TIC are at increased risk for mortality, transfusion requirements, and adverse outcomes5,6. First, organ dysfunction, sepsis, and mortality are significantly increased in patients with TIC. In addition, this patient population places greater demands on hospital resources, requiring more transfusions and ventilator support, and longer intensive care and hospitalization7,8,9. Specifically, one study found that patients with comorbid TIC had a significantly higher mortality rate, which was four times that of patients without TIC (46.0% vs. 10.9%; P < 0.001)7. Further studies supported this finding, showing that 29% of patients in the TIC group developed multiple organ failure, and that the early in-hospital mortality rate (< 24 h) in patients with TIC was 13%, with an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 28% 10. Similarly, it has been shown that patients with comorbid TIC not only have increased mortality, organ damage, and transfusion requirements, but are also significantly associated with a reduction in ventilator-free days in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and with a predisposition to post-traumatic ventilator-associated pneumonia9.

However, in clinical practice, we may overlook TIC occurring in trauma patients post-surgery. Patients requiring surgery are particularly vulnerable to hypothermia due to extended exposure in the operating theater, increased fluid administration, and general anesthesia. Hypothermia worsens acidosis and contributes to coagulopathy by impairing platelet function11. Existing predictive models for early trauma coagulopathy do not adequately address TIC in patients post-surgery12. Furthermore, these models lack the accuracy needed to reliably guide treatment decisions13.

Machine learning is a branch of artificial intelligence and an important data mining tool. In recent years, with the development of structured electronic medical records and medical big data, machine learning has been increasingly used in the field of trauma, such as radiological image recognition of trauma patients and monitoring of injury changes. Li et al.14 developed a machine-learning prediction model to assess the risk of postoperative transfer to the ICU, complications, and delayed discharge in hip fracture patients, and the results showed that the model demonstrated good results in predicting the accuracy of postoperative transfer to the ICU, complications, and delayed discharge. Kazuya Matsuo et al.15 used a machine-learning constructed model to predict the hospitalization following traumatic brain injury complications and mortality during hospitalization with an AUC of 0.895, which plays a positive role in the management and treatment of traumatic encephalopathy patients during hospitalization.

The aim of this study was to create a TIC risk prediction model for severely traumatic patients after surgical interventions with the aim of identifying those at high risk of developing TIC after surgery.

Methods

Ethics

The study proposal was approved by the ethics committees of Chongqing Emergency Medical Center (No. 202348), Daping Hospital (No.2023261), The PLA Rocket Force Characteristic Medical Center (No. KY2023037), General Hospital of Southern Theater Command of PLA (No. NZLLKZ2024021). Informed consent was waived by each committee. The methods were conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was registered with the China Clinical Trial Centre under the registration number (ChiCTR2300078097).

Study population

This is a retrospective study. The data for this study were collected retrospectively from four hospitals in China, involving 9054 trauma patients admitted to hospital from January 2013 to January 2023 for surgical treatment. Inclusion criteria were as follows: patients who underwent surgical treatment after trauma and were ≥ 18 years old. Exclusion criteria: non-traumatic surgery, preoperative TIC, age < 18 years, ISS score < 16, and > 20% missing sample data.

Outcome definition

The main outcome of this study was development of TIC defined as following: activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) > 60 s or prothrombin time (PT) > 18 s or international normalized ratio (INR) > 1.5 16,17.

Data collection

The following variables were captured from the electronic patient record system. Demographic characteristics (sex, weight, age), preoperative comorbidities (hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease [CKD], cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], injury situation (mechanism of injury, location of injury), preoperative situation (injury severity score [ISS], systolic blood pressure, heart rate, diastolic blood pressure, shock, American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA], emergency), preoperative intervention (blood transfusion, haemostatic drugs, tracheal intubation, vasopressor, interventional procedure), intraoperative interventions (type of anaesthesia, sodium bicarbonate, vasopressor [intraoperative], warming equipment, operation time, blood loss, autologous blood, plasma, crystalloid, colloid, urine output, haemostatic drugs[intraoperative], Temperature [postoperative]), preoperative laboratory tests (red cell distribution width [RDW], white blood cell count [WBC], red blood cell count [RBC], hemoglobin [HGB], platelet distribution width [PDW], hematocrit [HCT], platelet [PLT], neutrophils% [Neu%], neutrophil count [Neu], mean platelet volume [MPV], Urea, creatinine [Cr], sodium, potassium, calcium, total protein, albumin, globulin, total bilirubin [TBil], aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], APTT, fibrinogen [Fib], PT, INR), and TIC.

Data preprocessing and variable selection

In this study, for categorical variables, we employed multinomial interpolation, while for continuous variables, mean interpolation was utilized. Variables with missing values exceeding 20% were removed from the analysis. Use MinMaxScaler to normalise the preprocessed data. The Fisher Score evaluation system18 from Python’s Scikit-learn library was employed to calculate and rank scores for each feature, and insignificant features were subsequently eliminated. This systematic approach aids in identifying influential variables crucial for constructing accurate predictive models.

Development of machine learning models

We constructed seven commonly used machine learning models: Backpropagation Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosted Decision Tree (GBDT), and Naive Bayesian (NB). ANN and XGBoost are suitable for high-dimensional complex data, ANN is used for deep learning tasks and XGBoost performs well in integrated learning. SVM is suitable for high dimensional and small sample classification problems. Logistic Regression is simple and intuitive, suitable for binary classification problems, and the model is highly explanatory. Random Forest and GBDT are suitable for complex nonlinear data, especially when the data is noisy, the former enhances the stability by integrating trees, and the latter improves the accuracy by gradient boosting. Naive Bayes is suitable for handling text classification and data with high dimensionality but strong feature independence. Previous studies have demonstrated the stability of these models19.

The study employed a single-center data derivation model. The training and testing sets were split in a 7:3 ratio, and five-fold cross-validation was employed. Each fold involved dividing the clinical dataset into five sections, with one part used as the validation set and the remaining four sections used for training the machine learning models. To address class imbalance between positive and negative categories, the training set was preprocessed using Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) 20. The final model evaluation results represent the average performance across the five folds, providing a robust assessment of model generalization. Evaluation metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, area under the curve (AUC), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated to assess model performance. These metrics were essential for evaluating the models’ suitability for clinical decision-making. Additionally, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted for each model to visualize and compare the AUC values, highlighting differences in performance.

Feature importance and model interpretability analysis

Based on the results of model evaluation, we identified the best-performing machine learning models. Feature importance analysis was conducted on these models to assess the impact of features on predictions. Each feature’s importance was determined using the model’s internal mechanisms. We focused on the top 20 features and ranked them according to their importance. A feature importance map was generated to visualize these rankings effectively. Additionally, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis was employed to interpret the model results further. Through SHAP’s single-sample exPlan analysis, we gained insights into how each feature contributes to predictions for individual samples. This approach provided a detailed understanding of feature contributions in predicting the risk of postoperative traumatic coagulopathy in trauma patients.

External validation

To validate our model, data were collected from three participating hospitals for external validation. We extracted the same features as used in the model and included a total of 863 case samples in the external validation set.

Statistic analysis

In descriptive statistics, categorical variables were compared between the development and external groups and between the train and validation sets using chi-square tests or the Fisher’s exact test. Differences in continuous variables were estimated using Student’s t-test or rank sum test. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics (version 27; IBM, Armonk, NY) and PyCharm (version 2022.3.2; JetBrains, Prague, Czech Republic) to ensure that rigorous statistical procedures were followed throughout the study.

Results

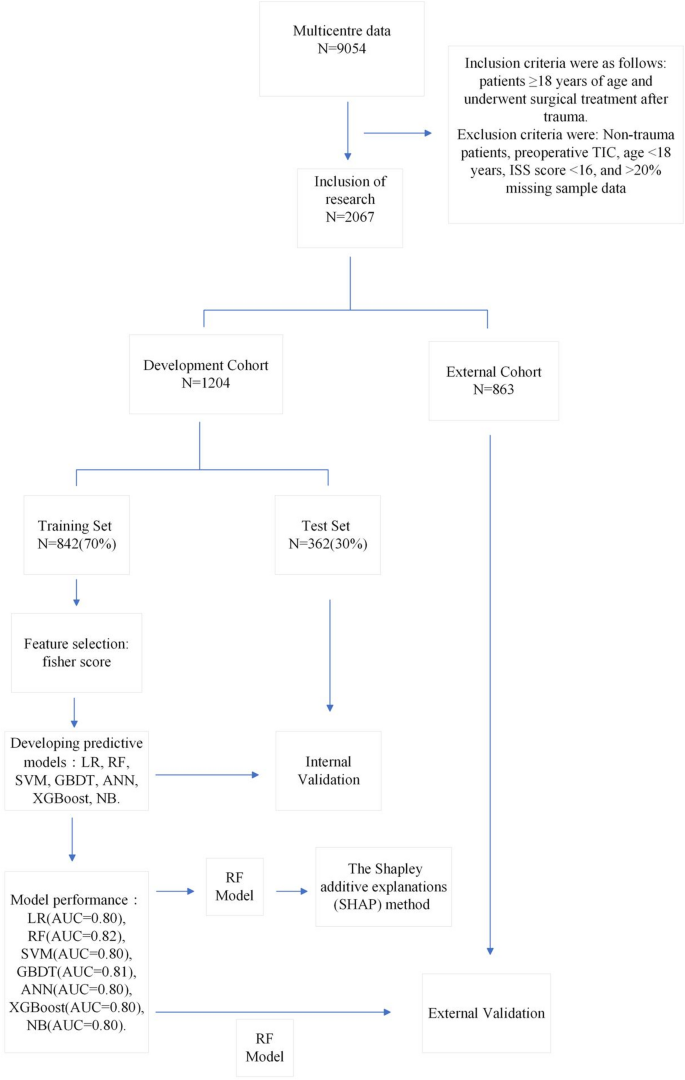

Initially, the study included 9054 cases. After excluding non-trauma patients (N = 8), those with preoperative coagulopathy (n = 35), age < 18 years (n = 5), ISS score < 16 (n = 6850), and cases with > 20% missing sample variables (n = 89), a total of 2067 cases were included in the study, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the development cohort, the median age was 51 (38–61) and 314 were male (26.1%); the overall incidence of TIC was 25.4%. There was no significant difference in demographics and preoperative comorbidities between the two groups (P > 0.05); however, there was significant difference in the mechanism of injury, preoperative conditions (shock, emergency surgery, ISS, ASA, heart rate), preoperative interventions (hemostatic drugs, endotracheal intubation, vasoactive medications), intraoperative interventions (anesthetic modality, bicarbonate, vasoactive medications, hemostatic drugs, operation time, hemorrhage, autologous blood, plasma, crystalloid, colloid, temperature), and preoperative tests (WBC, PLT, Neu, Neu%, RDW, MPV, urea, Cr, calcium, total proteins, albumin, globulin, ALT, APTT, PT, INR, and Fib) (P < 0.05).

Table 2 presents the baseline characteristics of the development cohort and the externally validated data. The incidence of postoperative TIC was 25.4% (306/1204) in the development cohort and 2.9% (25/863) in the external validation data. Variables that showed significant differences (p < 0.05) between the two cohorts included Injury situation (Mechanism of Injury, Location of Injury) preoperative factors (shock, emergency, ASA classification, ISS, heart rate), preoperative interventions (interventional procedure, blood transfusion, hemostatic drugs, tracheal intubation, vasopressors), preoperative laboratory tests (WBC, RBC, HGB, HCT, Neu%, Neu, RDW, PDW, MPV, Cr, sodium, potassium, calcium, albumin, globulin, TBiL, AST, APTT, PT, INR, Fib), intraoperative interventions (type of anesthesia, sodium bicarbonate, intraoperative vasopressors, tourniquet, warming equipment, intraoperative hemostatic drugs, operation time, blood loss, autologous blood, crystalloid, colloid, urine output, intraoperative temperature), TIC. Table 3 shows the one-way analyses of the training and test sets, the results of which show no significant differences in all variables between the two groups (p > 0.05).

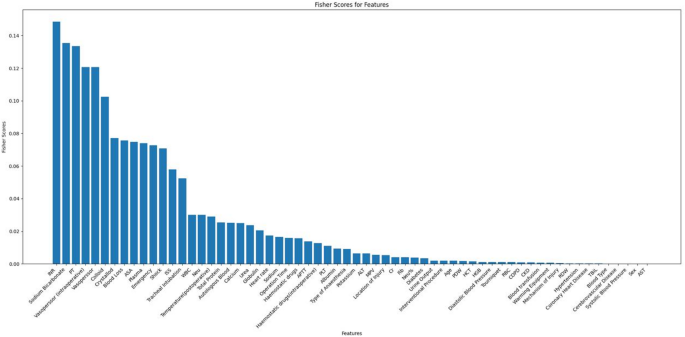

Figure 2 displays the Fisher scores in descending order, aiding in the selection of the optimal subset of features for the seven models. Ultimately, the top 32 variables were chosen for model training.

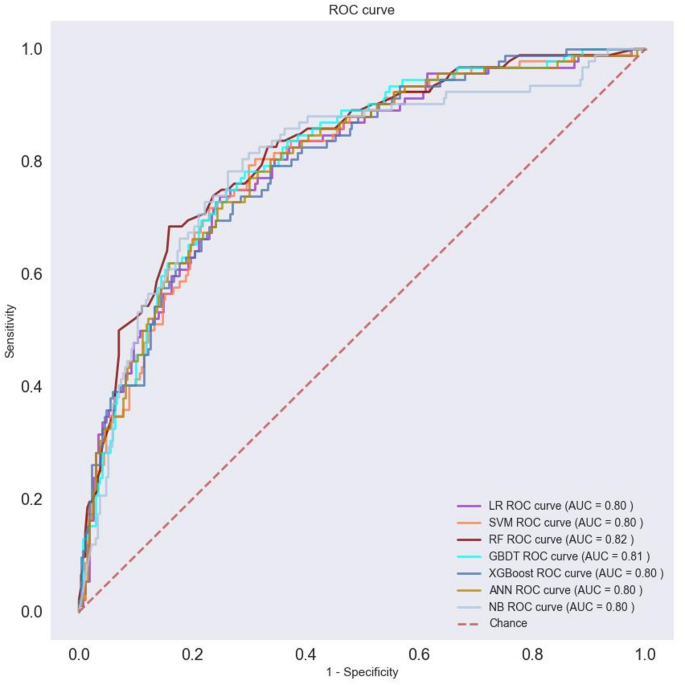

To assess the machine learning model’s performance, we partitioned the data into training and test sections in a 7:3 ratio and conducted five-fold cross-validation. Table 4 summarizes the results of the model evaluation. Additionally, ROC curves for visual comparison are depicted in Fig. 3.

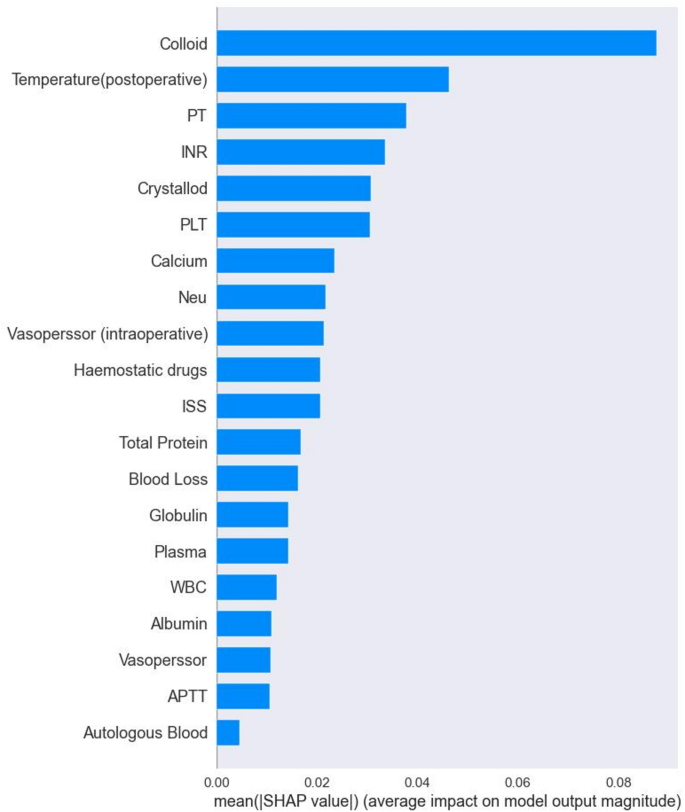

Evaluate model performance by AUC, Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV. The RF machine learning model, selected after evaluation, was utilized to analyze risk factors for postoperative TIC in trauma patients. This analysis was based on the results of built-in feature importance and SHAP analysis, aiming to construct a predictive model for postoperative TIC risk. Figure 4 presents the top 20 features and their importance according to the RF model’s built-in feature analysis. Key risk factors identified include colloid, temperature (postoperative), PT, INR, crystalloid, PLT, calcium, and vasopressor [intraoperative], hemostatic drugs.

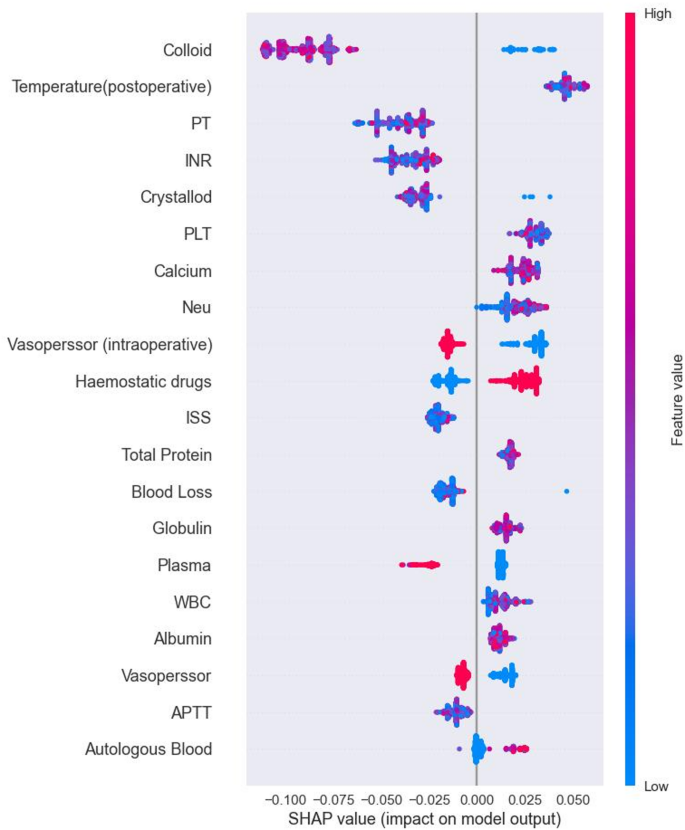

SHAP is a tool used to interpret machine learning model predictions by visualizing the contribution of each feature. It provides insights into both the direction and magnitude of each feature’s impact on model predictions. Figure 5 illustrates a summary plot of SHAP analysis for the RF model, highlighting the positive and negative contributions of features to predicting postoperative TIC in trauma patients. By examining the distribution of SHAP values, we identify features significantly influencing prediction outcomes. For instance, higher SHAP values for Colloid indicate greater impact on predicting TIC risk. The red distribution signifies samples with high feature values, correlating positively with prediction outcomes, suggesting higher risk for TIC. Conversely, the blue distribution indicates samples with low feature values, which negatively impact predictions, indicating lower TIC risk.

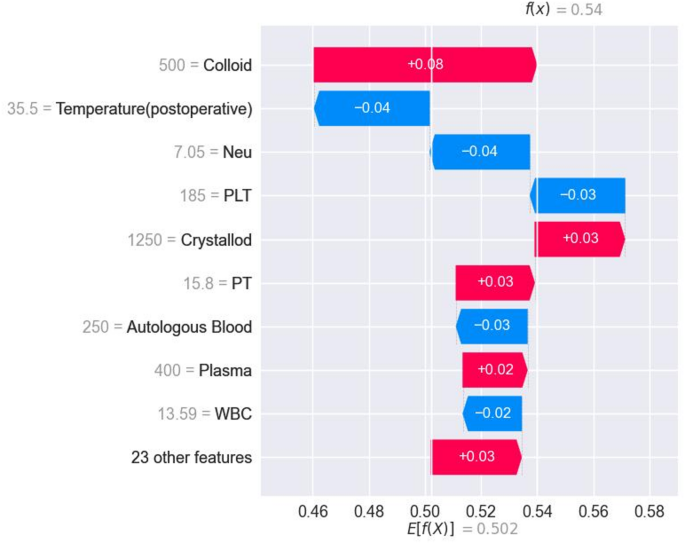

Figure 6 presents SHAP-specific instance plots, detailing how each feature influences TIC prediction in individual samples, along with predicted values. This aids in assessing each patient’s risk for postoperative TIC.

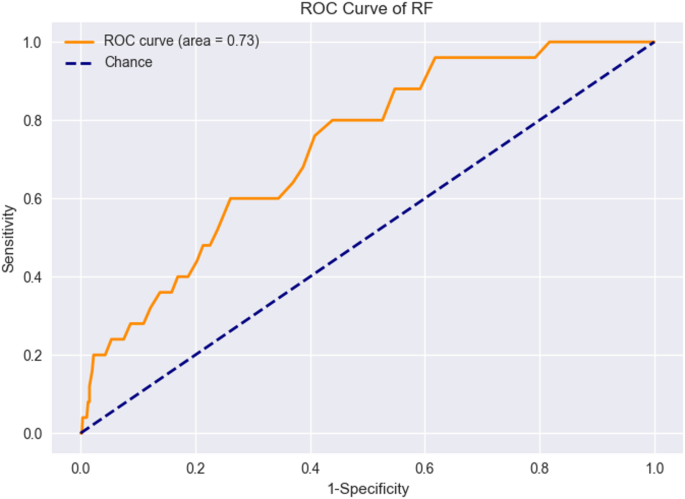

For external validation, we collected 4594 samples from three additional centers. After applying exclusion criteria, 863 patient samples formed the external validation set. The RF model trained earlier was applied to this set, resulting in an AUC value of 0.73. Figure 7 displays the ROC curve for external validation. Table 5 show the performance of RF model in the external validation.

Discussion

In this study, seven machine learning models were successfully constructed, of which the RF model outperformed the others in terms of performance, showing good performance in predicting and categorizing this data. Through feature importance analysis and SHAP interpretability analysis, the selected features were ranked according to the importance and frequency of occurrence of each feature in the RF model, which led to the identification of a number of factors that have a significant impact on the risk of postoperative TIC in severely traumatized patients.

For instance, fluid resuscitation using crystalloid and colloid fluids has been linked to dilutional coagulopathy and poorer post-trauma outcomes21. Hewson previously investigated 68 patients who underwent massive transfusions, noting that coagulation disorders were prevalent following crystalloid administration, with prolonged APTT correlating with the volume of crystalloids administered22. Furthermore, a retrospective single-center trial in the United States demonstrated a higher mortality rate among trauma patients who received more than 1.5 L of crystalloids in the emergency department23. Another study highlighted that patients receiving ≥ 5 L of crystalloids within 24 h of injury faced increased risks of mortality due to trauma-induced multiorgan dysfunction and persistent coagulation disorders24.

Body temperature and calcium levels are crucial factors influencing coagulation, as evidenced by findings from this study. Postoperative body temperature was identified as a significant risk factor for TIC in trauma patients. Previous research indicates that hypothermia adversely affects platelet function and coagulation factor activity, thereby contributing to coagulation dysfunction11. Additionally, studies have shown that hypocalcemia can lead to endotheliopathy, increased blood transfusions, heightened use of vasoactive drugs, and independently increase the risk of TIC25.

The results of this study have important implications for perioperative management of trauma patients. The results of this model may provide valuable guidance for perioperative resuscitation and postoperative coagulation management. Several models have been previously developed to recognize patients at risk of TIC. For example, Cosgriff et al. created a simple Score using criteria such as systolic blood pressure < 70 mmHg, temperature < 34 °C, ISS > 25 and pH < 7.1 (22). The inherent limitation of this score is its dependence on the ISS, which may not always be readily available due to diagnostic uncertainty. Recently, two predictive scoring systems have been developed to predict TIC risk using prehospital information. Mitra et al. proposed a score that combines early available predictors, including systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg or < 90 mmHg, temperature < 35 °C, injury to abdominal or pelvic contents, and chest decompression26. Meanwhile, Peltan et al. developed the Trauma Acute Coagulopathy Score using six predictors including prehospital shock index ≥ 1, age, mechanism of injury (excluding motor vehicle, motorbike, or bicycle collisions), GCS score below 15, prehospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and prehospital tracheal intubation27. These models are highly regarded for their simplicity and ease of use, but due to limitations in predictor selection and continuous variable dichotomisation, they may not fully reflect the complexity of the underlying pathophysiological processes. Subsequently, Perkins et al. used artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques to advance Bayesian network models to predict TIC. The model extracts predictors from prospective studies, minimising the risk of overfitting, and therefore excels in accuracy and adaptability to missing data28. However, although these scoring systems are designed to predict TIC, they may not encompass intraoperative factors that are critical for trauma patients undergoing surgical intervention. Such patients may be affected not only by initial trauma but also by perioperative fluid resuscitation, and therefore the above models may not be sufficient to predict them fully.

We leveraged domain knowledge in machine learning to develop a robust risk prediction model for postoperative TIC in trauma patients. During external validation, the model was directly tested using data from various centers. It is important to note that the model’s performance may vary when applied to different hospitals due to variations in surgical types and case characteristics. As can be seen from Table 1, there are many variables with statistically significant differences between the development cohort and the external cohort which suggests that the homogeneity and balance between the two cohorts are poor. This may affect the generalizability and stability of the predictive model constructed in the development cohort when undergoing external validation. However, our study demonstrated that the RF model maintained consistently high predictive performance, achieving an externally validated AUC of 0.73. This indicates the model’s robustness and validity across multiple centers. Although the predictive performance of the model has decreased, it is hypothesized that it may be possible that the external data may reflect a different clinical setting, patient background, or medical practice, resulting in a decrease in the predictive ability of the model on the external data. In the external validation we had a lower ppv value, because there are only 25 positive samples out of 863 external validation data. This may have led to a model bias towards predicting more negative samples, resulting in a higher npv of 0.979 and a lower ppv of 0.061. Machine learning models excel in capturing complex relationships and revealing nonlinear interactions among variables. Shap’s algorithm, a method for machine learning interpretation, calculates the contribution of each feature to predictions based on the Shapley values from game theory. This approach allows us to elucidate the impact of each feature on the model’s predictions, providing deeper insights into model behavior and enhancing interpretability.

This study represents the first attempt to develop a risk prediction model for postoperative TIC in trauma patients. However, several limitations need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the model was developed using retrospective data, which may introduce biases into the results. Future validation of the predictive model will be essential using prospective multicenter datasets to enhance its robustness and generalizability. Secondly, our current model relies on a substantial number of features to predict postoperative TIC, potentially limiting its practical utility. Future efforts should focus on developing a streamlined prediction model that maintains performance while reducing the number of required features. Thirdly, the study only incorporated certain clinical variables and laboratory tests. For instance, variables such as lactate levels in intraoperative blood gas analysis and base deficit, which reflect metabolism and perfusion responses, were not included. Incorporating these variables in future iterations of the model could further optimize its predictive accuracy. Finally, although a “black box” analytical interpretation of machine learning was used in this study, it is still unclear how the model predicts the outcomes. Relative importance and cross-validation revealed the features on which the model mainly relies, but we still have some uncertainty.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study established and validated seven commonly used machine learning algorithms, demonstrating that the RF algorithm outperformed others in predicting postoperative TIC in trauma patients. The RF algorithm exhibited robust predictive performance in both internal and external validation sets. These findings highlight its potential utility in screening patients at high risk of postoperative TIC, aiding clinicians in making informed clinical decisions and implementing timely interventions.

Data availability

Data can be obtained from the corresponding author by reasonable grounds.

References

Gruen, D. S. et al. Prehospital plasma is associated with distinct biomarker expression following injury. JCI Insight 5, 1–17 (2020).

Spahn, D. R. et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fifth edition. Crit. Care. 23, 98 (2019).

Moore, E. E. et al. Trauma-induced coagulopathy. Nat Rev. Dis. Primers 7, 1–23 (2021).

Buzzard, L. & Schreiber, M. Trauma-induced coagulopathy: what you need to know. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 96, 179–185 (2024).

Moore, E. E. et al. Trauma-induced coagulopathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7, 30 (2021).

Floccard, B. et al. Early coagulopathy in trauma patients: an on-scene and hospital admission study. Injury 43, 26–32 (2012).

Brohi, K., Singh, J., Heron, M. & Coats, T. Acute traumatic coagulopathy. J. Trauma-Injury Infect. Crit. Care. 54, 1127–1130 (2003).

MacLeod, J. B., Winkler, A. M., McCoy, C. C., Hillyer, C. D. & Shaz, B. H. Early trauma induced coagulopathy (ETIC): prevalence across the injury spectrum. Injury 45, 910–915 (2014).

Cohen, M. J. et al. Critical role of activated protein C in early coagulopathy and later organ failure, infection and death in trauma patients. Ann. Surg. 255, 379–385 (2012).

MacLeod, J. B., Lynn, M., McKenney, M. G., Cohn, S. M. & Murtha, M. Early coagulopathy predicts mortality in trauma. J. Trauma. 55, 39–44 (2003).

Lier, H., Krep, H., Schroeder, S. & Stuber, F. Preconditions of hemostasis in trauma: a review. The influence of acidosis, hypocalcemia, anemia, and hypothermia on functional hemostasis in trauma. J. Trauma. 65, 951–960 (2008).

Thorn, S., Güting, H., Maegele, M., Gruen, R. L. & Mitra, B. Early identification of acute traumatic coagulopathy using clinical prediction tools: A systematic review. Medicina (Kaunas) 55, 1–17 (2019).

Brohi, K. Prediction of acute traumatic coagulopathy and massive transfusion - Is this the best we can do?. Resuscitation 82, 1128–1129 (2011).

Li, Y. Y. et al. Implementation of a machine learning application in preoperative risk assessment for hip repair surgery. BMC Anesthesiol. 22, 116 (2022).

Matsuo, K. et al. Machine learning to predict In-Hospital morbidity and mortality after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 37, 202–210 (2020).

Brohi, K., Cohen, M. J. & Davenport, R. A. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: mechanism, identification and effect. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 13, 680–685 (2007).

Peltan, I. D., Vande Vusse, L. K., Maier, R. V. & Watkins, T. R. An international normalized Ratio-Based definition of acute traumatic coagulopathy is associated with mortality, venous thromboembolism, and multiple organ failure after injury. Crit. Care Med. 43, 1429–1438 (2015).

Ge, C., Luo, L., Zhang, J., Meng, X. & Chen, Y. FRL: An Integrative Feature Selection Algorithm Based on the Fisher Score, Recursive Feature Elimination, and Logistic Regression to Identify Potential Genomic Biomarkers. Biomed Res Int 4312850 (2021). (2021).

Frondelius, T., Atkova, I., Miettunen, J., Rello, J. & Jansson, M. M. Diagnostic and prognostic prediction models in ventilator-associated pneumonia: systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction modelling studies. J. Crit. Care. 67, 44–56 (2022).

Dablain, D., Krawczyk, B. & Chawla, N. V. DeepSMOTE: fusing deep learning and SMOTE for imbalanced data. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 34, 6390–6404 (2023).

Cosgriff, N. et al. Predicting life-threatening coagulopathy in the massively transfused trauma patient: hypothermia and acidoses revisited. J. Trauma. 42, 857–861 (1997). discussion 861 – 852.

Hewson, J. R. et al. Coagulopathy related to Dilution and hypotension during massive transfusion. Crit. Care Med. 13, 387–391 (1985).

Ley, E. J. et al. Emergency department crystalloid resuscitation of 1.5 L or more is associated with increased mortality in elderly and nonelderly trauma patients. J. Trauma. 70, 398–400 (2011).

Jones, D. G. et al. Crystalloid resuscitation in trauma patients: deleterious effect of 5L or more in the first 24h. BMC Surg. 18, 93 (2018).

DeBot, M., Sauaia, A., Schaid, T. & Moore, E. E. Trauma-induced hypocalcemia. Transfusion 62 (Suppl 1), S274–s280 (2022).

Mitra, B. et al. Early prediction of acute traumatic coagulopathy. Resuscitation 82, 1208–1213 (2011).

Peltan, I. D. et al. Development and validation of a prehospital prediction model for acute traumatic coagulopathy. Crit Care 20, 1–10 (2016).

Perkins, Z. B. et al. Early identification of Trauma-induced coagulopathy: development and validation of a multivariable risk prediction model. Ann. Surg. 274, e1119–e1128 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jie Peng, Yishu Wang, Yue Ma, Xiaojuan Xiong, Yunqin Ren, Xian Chen, Mi Zhou, Weihai Zhou, Lei Wang, Yu Zhang, Qiling Jiang, Jinke Li, Xiongli Wang for their help during data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by Chongqing Municipal Studios for Young and Middle-aged Top Medical Talents (ZQNYXGDRCGZS2019006) and Chongqing Talent Program: Innovative leading talents (CSTC2024YCJH-BGZX M0011). None of these funding sources had any role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei Wang, Bo Xu, Yi Guo, Shuai Feng participated in the conception, data organisation, methodology. Jiang zheng, Xiaohui Du visualised and wrote the manuscript. Qingxiang Mao, Hong Fu contributed to the conception and supervision. Victor W. Xia, Hong Fu contributed to the intellectual revision of the manuscript.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, X., Wang, W., Xu, B. et al. Predicting postoperative trauma-induced coagulopathy in patients with severe injuries by machine learning. Sci Rep 15, 27072 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13283-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13283-x