Abstract

With the exponential growth of wireless communication systems, the need for compact, high-performance antennas operating at millimeter-wave (mm-Wave) frequencies has become increasingly critical. This paper presents a comprehensive design and performance analysis of a microstrip patch antenna system operating at dual frequencies of 28 GHz and 38 GHz, suitable for 5G and beyond applications. The antenna evolves from a single element to a 2-element array and a 4-port MIMO configuration, achieving high gains of 9 dB and 8.4 dB, respectively. It covers wide bandwidths of 2.55 GHz and 5.77 GHz within the operating ranges of 26.73–29.28 GHz and 34.96–40.73 GHz. Designed on a Rogers RT5880 substrate, the antenna measures 31.26 mm × 31.26 mm (2.92λ0 × 2.92λ0), offering a compact footprint with excellent performance. The system achieves isolation values greater than 35 dB and 29 dB, extremely low Envelope Correlation Coefficients (ECC) of < 0.0001 and Diversity Gain (DG) of > 0.999, and radiation efficiency exceeding 98% and 99%. A machine learning-based performance prediction framework was employed, where five regression models were evaluated using critical metrics, including variance score, R-squared, mean squared error (MSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean square error (RMSE). Among them, the Extra Trees Regression model demonstrated the highest efficacy, achieving the lowest error rates of 14.04% for MAE, 4.42% for MSE, and 21.03% for RMSE, along with an isolation prediction accuracy of approximately 93%. With its outstanding performance, compact design, and intelligent prediction capabilities, the proposed antenna system is a strong contender for future high-capacity mm-Wave wireless communication networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid growth of data-intensive applications, autonomous systems, and smart devices has significantly accelerated the evolution of 5G and beyond wireless technologies, necessitating communication infrastructures that can deliver ultra-high data rates, minimal latency, high efficiency, and support for massive device connectivity in real-time1. Emerging applications such as augmented/virtual reality (AR/VR), real-time industrial automation, telemedicine, smart cities, and connected autonomous vehicles demand a transformative shift in wireless capabilities2. To meet these requirements, researchers and industry stakeholders have increasingly turned to the higher end of the electromagnetic spectrum, particularly the millimeter-wave (mm-Wave) bands, which offer multi-gigahertz bandwidths capable of supporting data rates over several Gbps3. Unlike traditional sub-6 GHz frequency bands, which are overcrowded and spectrum-limited, mm-Wave frequencies enable greater spectral availability and higher throughput, thus becoming instrumental for 5G New Radio (NR) deployments. In this context, the 28 GHz and 38 GHz frequency bands have emerged as promising candidates for early 5G trials and commercial rollouts, especially in dense urban, enterprise, and indoor hotspot scenarios4.

However, the adoption of mm-Wave communication comes with inherent physical challenges. These frequency bands are highly susceptible to severe free-space path loss, atmospheric absorption (particularly oxygen absorption at 60 GHz), and material penetration loss, resulting in limited propagation range and poor diffraction characteristics5. Additionally, their high sensitivity to obstructions—such as buildings, foliage, and even human bodies—makes maintaining reliable links in dynamic environments a non-trivial task6. To address these limitations, advanced antenna technologies capable of high directional gain, adaptive beam steering, and spatial diversity are required. In this regard, Multiple-Input Multiple-Output (MIMO) systems have emerged as a key enabler for robust mm-Wave communication, offering significant improvements in spectral efficiency, link reliability, and channel capacity through spatial multiplexing and diversity techniques7. By simultaneously transmitting multiple independent data streams across different antenna elements, MIMO systems can overcome multipath fading and ensure better signal robustness in non-line-of-sight (NLoS) environments8.

Nevertheless, the successful implementation of MIMO systems at mm-Wave frequencies is heavily dependent on the design and optimization of the individual antenna elements. Unlike in sub-6 GHz systems where half-wavelength element spacing is relatively large, mm-Wave frequencies allow compact antenna arrays due to the short wavelength, enabling denser integration of multiple antennas within a small footprint9. This makes them ideal for portable and embedded platforms such as smartphones, IoT nodes, and wearable devices. However, challenges such as mutual coupling, impedance mismatch, gain variation, polarization mismatch, and low radiation efficiency become increasingly critical at higher frequencies10. As such, the design of antenna elements must ensure high isolation, consistent gain, wide impedance bandwidth, and stable radiation patterns. In recent studies, researchers have proposed several techniques—including parasitic elements, electromagnetic bandgap (EBG) structures, metamaterials, and Defected Ground Structures (DGS)—to mitigate coupling and enhance performance in MIMO arrays11.

Microstrip patch antennas (MPAs) have emerged as suitable candidates for mm-Wave MIMO systems due to their compact size, low profile, conformability, and ease of integration with other circuit components. Nevertheless, conventional MPAs face limitations in bandwidth, gain, and mutual coupling, especially at mm-Wave frequencies. Recent works have attempted to address these issues by introducing novel feeding techniques, DGS, and hybrid geometries. The proposed design, however, holds the potential to overcome these limitations, offering hope for the future of 5G technology12.

In parallel with advancements in antenna hardware, the design process itself has transformed through the integration of machine learning (ML) techniques. ML enhances antenna design by utilizing data-driven models to swiftly predict performance metrics such as gain and bandwidth, thereby minimizing reliance on time-consuming electromagnetic (EM) simulations. Once trained on simulation or measurement data, ML models can instantly evaluate new designs, enabling rapid prototyping and iterative optimization. This is particularly advantageous in fast-paced sectors like telecommunications, aerospace, and the Internet of Things (IoT). ML’s capability to explore vast and complex design spaces with minimal human input further streamlines the development of innovative antennas. Beyond efficiency, ML supports autonomous evaluation and synthesis of antenna structures, helping generate designs that satisfy predefined criteria with reduced manual intervention13.

Additionally, ML systems are more resilient to real-world variabilities—such as fabrication tolerances or environmental changes—compared to conventional EM solvers, which often assume ideal conditions. Importantly, ML also facilitates multi-objective optimization by concurrently addressing multiple design goals like bandwidth, efficiency, and compactness. Altogether, the integration of ML not only accelerates antenna development but also enhances the quality, adaptability, and real-world viability of next-generation wireless systems14.

Motivated by these developments, this paper presents a novel compact dual-band MIMO microstrip patch antenna operating at both 28 GHz and 38 GHz, specifically designed to support 5G mm-Wave communication in urban, indoor, and dense-network environments. Key design features include a multilayer substrate architecture, a defective ground for bandwidth enhancement, and an optimized element spacing strategy to reduce envelope correlation and mutual coupling. Extensive simulation and parametric studies are conducted to evaluate S-parameters, gain, ECC, DG, and CCL, demonstrating the design’s suitability for future high-capacity wireless systems. Compared to existing state-of-the-art designs, the proposed antenna exhibits improved performance in terms of bandwidth, gain, and isolation, with a form factor conducive to integration in next-generation 5G devices.

The key contributions of this research are outlined below:

-

A novel compact dual-band MIMO antenna operating at 28 GHz and 38 GHz is proposed, covering key mm-Wave 5G bands with wide bandwidths of 2.55 GHz and 5.77 GHz.

-

The proposed MIMO antenna achieves high isolation (> 35 dB and > 29 dB).

-

An equivalent RLC circuit model is developed for all antenna stages and validated using ADS and CST tools.

-

Machine learning is integrated for gain prediction, with the Extra Trees Regression model achieving the highest accuracy (R2 ≈ 93%, MAE ≈ 14%).

-

The ML-based prediction enables rapid performance estimation and supports future real-time antenna optimization.

-

The proposed design is highly suitable for 5G and IoT applications, including smart cities, V2X, and high-speed wireless systems.

1. Design methodology and result

To ensure a clear understanding of the proposed antenna’s development, this section details the design evolution from a single element to an array, and finally to a MIMO configuration. Each design stage is optimized and evaluated based on return loss, gain, efficiency, and mutual coupling. The antenna design process begins with a single-element microstrip patch structure optimized for a resonance frequency of 28 GHz. The substrate material used is Rogers RT5880, which is 0.787 mm thick, ensuring low dielectric losses.

1.1 Design evolution of the single-element antenna and result

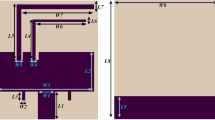

Figure 1 illustrates a two-dimensional single-element microstrip antenna, showcasing a detailed layout with labeled parameters defining its geometry.

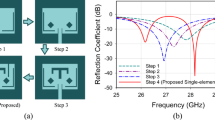

Figure 2 illustrates the step-by-step evolution of the proposed antenna design, starting from a basic rectangular patch and gradually incorporating various structural modifications to enhance performance. The overall structure includes a substrate made of Rogers RT-5880 with dimensions labeled as Lses for its length and Wses for its width, serving as the foundation for the antenna15. In Step 1, a simple rectangular patch with dimensions denoted as Wp (patch width) and Lp (Patch length), with a feedline, is introduced as the baseline structure. As shown in Fig. 3a, for step 1, the configuration exhibits a return loss of − 12.83 dB at 28.31 GHz, indicating basic resonance but limited impedance matching. In Step 2, a central star-shaped slot—defined by parameters d1 and d2—is etched into the patch to perturb the surface current and introduce new resonant paths. This improves performance, reducing the return loss to − 18.02 dB at 27.99 GHz. Step 3 incorporates small cuts at the bottom of the patch, which further adjust the current distribution and result in an improved return loss of − 21.24 dB at 28.48 GHz. In Step 4, symmetrical rectangular slots are added to the structure, introducing multiple current paths that support multi-resonant behavior; as a result, the return loss significantly improves to − 28.31 dB at 29.25 GHz. Step 5 continues this refinement by adding more rectangular slots, increasing structural complexity and electromagnetic coupling. This step yields an even better return loss of − 34.92 dB at 28.58 GHz. Finally, in Step 6 (Proposed), resulting in an optimized design that achieves a remarkably low return loss of − 55.67 dB. The proposed antenna thus operates efficiently over a wide bandwidth ranging from 27.47 to 29.72 GHz, demonstrating excellent impedance matching and minimal signal reflection across the mm-Wave band.

Figure 3b indicates the gain and efficiency performance of the proposed single-element antenna. The gain is the ability of the antenna to direct or concentrate radio frequency energy in one particular direction, including both the directivity and efficiency of the antenna16. Efficiency is a parameter that indicates how efficiently the input power is delivered by the antenna in the form of radiated electromagnetic waves, considering losses such as conductor and dielectric losses. The proposed design achieves a maximum gain of approximately 7.11 dB, with high directional radiation and signal enhancement. The efficiency is also maximized, up to 97.68%, thereby demonstrating that nearly all input power is radiated with minimal loss within.

1.1.1 Effect of varying single-element antenna parameters

The effect of feed width (Wf) on the antenna’s reflection coefficient was investigated by varying it between 0.9 mm and 1.1 mm. As shown in Fig. 4a, the optimal value of Wf = 1 mm (proposed) achieves the lowest return loss, with a return loss below − 56 dB near 28.5 GHz. Decreasing or increasing the feed width (Wf) results in a noticeable shift in the resonant frequency, accompanied by a degradation in the return loss. The return losses are − 47.27 dB and − 37.37 dB at 28.28 GHz and 28.71 GHz for the feed widths of 0.9 mm and 1.1 mm, respectively. It highlights that with an increase in feed width, the reflection coefficient shifts to the right, and with an increase in feed, the curve shifts to the left, together with a degradation of return loss in both cases.

Figure 4b shows the impact of inset length (IL) variation on antenna performance. The analysis considers IL values of 0.9 mm, 1.1 mm, and the proposed 1 mm. The proposed configuration again exhibits the most optimal result. In contrast, deviations from this value result in a shallower reflection, which is − 23.94 dB and − 21.24 dB for the inset lengths of 0.9 mm and 1.1 mm, respectively, indicating suboptimal impedance matching. It shows that a slight change in the value of the inset length causes a significant return loss. However, the resonance frequency does not shift that much.

The effect of the first slot length (L1) on the reflection coefficient is presented in Fig. 4c, where lengths of 0.8 mm, 1.2 mm, and the proposed 1 mm were examined. For L1 = 0.8, the resonance frequency is 28.34 GHz with a return loss of − 19 dB, and for L1 = 1.2 mm, the resonance frequency is 28.16 GHz with a return loss of − 10.22 dB. The results indicate that other values exhibit poorer matching and very high return loss, with a slight shift in resonance to the left, underscoring that subtle variations in L1 can lead to inferior performance.

Figure 4d explores the influence of the first slot width (W1) by testing values of 0.3 mm, 0.5 mm, and the proposed 0.4 mm. For both W1 values of 0.3 mm and 0.5 mm, the return loss is high, which is − 25.29 dB and − 22.36 dB, respectively, at 28.33 GHz and 28.62 GHz.

The variation in third slot length (L3) is illustrated in Fig. 4e, where three lengths (0.9 mm, 1.1 mm, and the proposed 1 mm) were evaluated. The variations slightly affect the resonance frequency, which is 28.58 GHz and 28.4 GHz, resulting in a moderate change in return loss, which is − 34.92 dB and − 31.07 dB, for L3 values of 0.9 mm and 1.1 mm, respectively. The proposed L1 value ensures both high return loss and alignment with the design frequency.

Lastly, Fig. 4f analyzes the role of the third slot width (W3) by comparing values of 0.2 mm, 0.3 mm, and the proposed 0.1 mm. Larger slot widths result in less efficient resonance, as reflected in shallower dips. For a W3 value of 0.2 mm, the return loss is − 27.27 dB at 28.32 GHz, and for a W3 value of 0.3 mm, the return loss is − 21.2 dB at 28.13 GHz. These results indicate that accurate control of slot width is essential for achieving strong resonance and desired operational characteristics at the target frequency.

1.2 Array antenna design and result

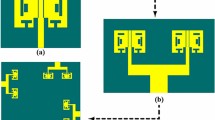

Figure 5 illustrates a two-element array antenna with two identical radiating elements arranged symmetrically. The substrate dimensions labeled Las (length) and Was (width) provide the overall structure for the array. Each radiating element features a patch with a star-shaped slot at the center, similar to the single-element antenna design. The dimensions of the patch and slot contribute to the antenna’s resonance and radiation characteristics. The two elements are separated by a distance dp − p, which represents the inter-element spacing. The feed network is designed to distribute the input signal to both radiating elements. It consists of a central feedline, with width Wf1 and length Lf1, branching into two paths. Each branch includes additional feedline segments, defined by Wf2, Wf3, Lf2, and Lf3, ensuring proper impedance matching and signal distribution to the radiating elements.

This array design enhances parameters such as gain, directivity, and beamforming capabilities, making it suitable for advanced communication systems. The inclusion of two radiating elements allows for broader coverage, increased radiation efficiency, and potentially multi-band operation, depending on the specific application.

During the design process of the array antenna, we discovered that it exhibits two distinct resonance frequencies: one within the 28 GHz frequency band and the other within the 38 GHz band. The antenna tuned to 28 GHz demonstrates an operational bandwidth of approximately 2.54 GHz (26.73–29.27 GHz), allowing for a range of effective communication frequencies while the return loss is − 42.92. In contrast, the antenna that operates at 38 GHz offers a slightly wider bandwidth of about 5.66 GHz (35.12–40.78 GHz). Furthermore, it achieves an impressive return loss of around − 43 dB, indicating its efficiency in minimizing signal reflections and enhancing overall performance, which is shown in Fig. 6a.

Figure 6b presents the performance characteristics of the array antenna, illustrating significant improvements in both gain and efficiency. At resonance frequencies of 28 GHz and 38 GHz, the antenna achieves impressive gain levels of 9.16 dB and 8.18 dB, respectively. Additionally, the efficiency of the antenna reaches an outstanding 98.32% and 98.47%, respectively.

Table 1 compares the results between single-element and array antennae, where the results show that in the array, the bandwidth and gain are much higher than in single-element antennae. Additionally, the array antenna has a dual-band, making it more versatile than the single-element antenna. The single-element antenna resonates at 28 GHz with an operating range of 27.47–29.72 GHz, offering a bandwidth (BW) of 2.25 GHz, a gain of 4.76 dB, and an efficiency of 99.35%. In contrast, the array antenna resonates at both 28 GHz and 38 GHz, covering broader operating ranges of 26.73–29.27 GHz and 35.12–40.78 GHz. It offers a higher bandwidth of 5.66 GHz, with a gain of 9.16 dB and an efficiency of 98.47%. The array antenna shows improved performance, particularly in gain and operating range, compared to the single-element design.

1.2.1 Effect of varying array antenna parameters

The first parameter analyzed is the patch length (pl), which is varied among 2.95 mm, 3.06 mm (proposed), and 3.2 mm. The results indicate that increasing or decreasing the patch length affects the resonance frequencies, shifting the S11 minima, as shown in Fig. 7a. The proposed pl = 3.06 mm achieves the best impedance matching, as evidenced by the deepest S11 dip, ensuring optimal resonance at the target frequency.

Figure 7b shows the effect of patch width (pw), tested with values of 2.1 mm, 4.323 mm (proposed), and 5.4 mm. A variation in patch width alters the impedance-matching characteristics, leading to shifts in both lower and upper resonance frequencies. The proposed pw = 4.323 mm exhibits superior return loss characteristics, maintaining strong resonance and a broader bandwidth. This suggests that an optimal patch width is essential for ensuring efficient impedance matching and stable frequency response.

Lastly, the influence of patch-to-patch distance (dp − p) is analyzed, with values of 2.54 mm, 2.9 mm (proposed), and 3.6 mm in Fig. 7c. This parameter plays a critical role in controlling the mutual coupling between adjacent patches, directly affecting the resonance behavior. A smaller dp − p results in stronger coupling, while a larger dp − p shifts the resonance and alters bandwidth performance. The proposed dp − p of 2.9 mm provides the best trade-off, ensuring optimal isolation and stable resonance characteristics.

1.3 MIMO antenna design and result

Figure 8 represents a 4-port MIMO (Multiple-Input Multiple-Output) antenna system. The design includes four radiating elements positioned at the four sides of the square substrate to ensure spatial diversity and reduce mutual coupling. The overall dimensions of the MIMO system are denoted by Wms, which defines the length and width of the substrate hosting the antenna elements. As seen in the previous design, each radiating element comprises a two-element array. These array elements are strategically placed with a spacing of d3 between adjacent radiators, which helps to minimize interference and optimize isolation between the ports. The exact ground from the array antenna is used in MIMO, making the ground defective in the center and four corners. The use of a connected ground structure across the MIMO configuration plays a critical role in improving isolation and minimizing mutual coupling between antenna elements. The defective ground structure (DGS) strategically placed at the center and corners introduces high-impedance paths that suppress surface wave propagation, thereby improving the isolation and ensuring a low ECC. This shared ground strategy contributes significantly to the antenna’s diversity performance, making it highly suitable for high-capacity 5G systems.

The design ensures that the elements are adequately separated to achieve good performance metrics, such as high isolation and low envelope correlation coefficient (ECC), both crucial for MIMO systems. The parameter d3 represents the distance between two adjacent array elements. Its symmetrical layout, compact size, and optimized inter-element spacing enhance the system’s performance by reducing mutual coupling and improving diversity gain17.

The simulated and measured S-parameters of the proposed antenna are illustrated in Fig. 9a,b. S-parameters or scattering parameters in RF systems and antennas specify the RF signal behavior in a multi-port network. S11, or reflection coefficient, indicates how much power is reflected from the input port; a value below − 10 dB typically means a good impedance match. S12 and S13, or the transmission coefficients, are the amount of signal transmitted or coupled from one port to another, and the lower values indicate better isolation between them.

As observed in Fig. 9a, the simulated S11 demonstrates two prominent resonances below − 10 dB at approximately 28.4 GHz and 38.3 GHz, indicating good impedance matching across these frequencies. The measured S11 follows a similar trend, with resonance dips occurring near the simulated ones, though with slight frequency shifts and higher reflection levels due to fabrication tolerances and measurement errors. The simulated bandwidths of the MIMO antenna are 2.55 GHz (26.73–29.28 GHz) and 5.77 GHz (34.96–40.73 GHz).

In Fig. 9b, both the simulated and measured S12 and S13 transmission coefficients are shown to be below − 35 dB and − 29 dB over the entire frequency range from 28 and 38 GHz, respectively, confirming effective isolation between the ports. The consistency between simulation and measurement validates the antenna’s performance in terms of port isolation and multi-band operation18.

Figure illustrates the measurement setup for the proposed MIMO antenna system. The reflection and transmission coefficients were measured using a Vector Network Analyzer (VNA), as shown in Fig. 10a. The calibration was performed before the measurements to ensure accuracy. The fabricated prototype is shown in Fig. 10b, where the antenna consists of four symmetrical radiating elements, each fed through an SMA connector. Figure 10c displays the antenna placed inside an anechoic chamber for radiation pattern and gain measurements. The antenna under test is mounted on a wooden tripod and connected via low-loss cables to minimize any external interference. The chamber is fully lined with RF absorbers to emulate free-space conditions and suppress unwanted reflections.

Figure 11 presents the simulated and measured gain and efficiency of the proposed antenna across the frequency range of 25–45 GHz. The simulated gain remains relatively stable, with a peak of 9 dB at 28 GHz and 8.4 dB at 38 GHz, respectively. The measured gain closely follows the simulated trend, with slight variations attributed to measurement inaccuracies and fabrication tolerances.

The corresponding efficiency results indicate excellent performance. The simulated efficiency consistently exceeds 97% across the band, reaching up to 99%. The measured efficiency also remains high, which confirms the low-loss behavior and good radiation characteristics of the antenna. These results validate the design’s suitability for mm-Wave applications requiring high efficiency and stable gain.

1.3.1 Diversity performance of the MIMO antenna

Diversity performance is a crucial aspect of MIMO antenna systems, ensuring improved signal quality and reliability in wireless communication. Key parameters such as the envelope correlation coefficient (ECC) and diversity gain (DG) are used to assess the antenna’s ability to maintain uncorrelated radiation patterns and achieve efficient signal transmission. A well-designed MIMO antenna should exhibit a low ECC and a high DG to enhance system performance.

The envelope correlation coefficient (ECC) measures the correlation between radiation patterns of multiple antenna elements. An ideal ECC value is close to zero, typically below 0.05, to ensure minimal interference and high diversity performance. The value of ECC can be figured out by using the expression shown below19.

For the proposed MIMO antenna, the simulated ECC remains below 0.0002, which is significantly lower than the acceptable threshold. Moreover, the measured ECC values align closely with the simulated results, as illustrated in Fig. 12. This exceptionally low ECC indicates excellent isolation between antenna elements, enabling superior MIMO performance with minimal signal distortion.

Diversity gain (DG) quantifies the effectiveness of a MIMO antenna in mitigating signal fading and improving overall system reliability. The ideal DG value is 10 dB, which represents optimal diversity performance. The value of DG can be determined by using the equation provided here20.

The proposed antenna achieves a simulated DG of approximately 9.99, indicating minimal degradation from the ideal case. After fabrication, the measured DG slightly reduces to 9.91, which still meets the standard requirements. As shown in Fig. 13, this high DG confirms that the antenna provides effective signal diversity, making it a strong candidate for modern high-performance wireless applications.

The Total Active Reflection Coefficient (TARC) characterizes the reflection performance of a MIMO antenna when all ports are excited simultaneously with equal amplitude and random phase. It can be calculated using Eq. (3)21:

For optimal performance, the value of TARC should be < 0 dB. As shown in Fig. 14a, the TARC remains well below − 10 dB over the entire operating band, reaching a minimum of approximately − 30 dB around 28 GHz and − 22 dB at 38 GHz.

Channel Capacity Loss (CCL) quantifies the degradation in data rate due to correlation and mutual coupling between antenna elements. It can be calculated using Eq. (4)22:

where, \(\rho_{R}\) represent the port correlation matrix at the receiver. As shown in Fig. 14b, the CCL remains below 0.1 bps/Hz throughout the operating frequency range, which meets the acceptable limit of 0.1 bps/Hz for efficient MIMO performance.

Mean Effective Gain (MEG) is a measure of the average power received by each antenna element in a multipath environment. It can be calculated using Eq. (5)23:

As depicted in Fig. 14c, the MEG values for both antenna elements are closely matched and lie within the acceptable range of − 3– − 12 dB.

1.3.2 Surface current distribution

Figure 15 illustrates the surface current distribution (in A/m) on the proposed antenna structures at 28 GHz and 38 GHz for both single-element and array configurations. These distributions were obtained through full-wave electromagnetic simulation.

Figure 15 provides a comparative visualization between a single-element antenna and the array configuration. The top sub-figure displays the current distribution of the single-element antenna at 28 GHz, showing strong and symmetric current flow across the patch, with peak values reaching up to 25 A/m. The bottom row includes two sub-figures showing the array antenna performance at 28 GHz and 38 GHz, respectively. At 28 GHz, the current is well confined and symmetrically distributed across the array elements, with efficient excitation of both patches. However, at 38 GHz, while the excitation remains functional, a noticeable reduction in peak current magnitude is observed, accompanied by more dispersed current flows toward the feedline and surrounding areas, further supporting the increased mutual interaction at higher frequencies.

In Fig. 16, the current distributions are presented for the full 2 × 2 MIMO antenna array at two distinct frequency points: 28 GHz and 38 GHz. It is observed that at 28 GHz, strong surface currents are concentrated around the feedline and the radiating star-shaped patch, confirming effective excitation and radiation at this frequency. Additionally, mutual coupling among elements is relatively well controlled, as evidenced by the limited current spread to adjacent elements. In contrast, at 38 GHz, while the excitation of each element remains efficient, the current intensity decreases, and more current leakage to neighboring elements is visible, indicating increased coupling at higher frequencies. This behavior is also supported by the scale bars, which show a peak current magnitude of approximately 15 A/m at 28 GHz and 8 A/m at 38 GHz.

1.3.3 Radiation pattern of the MIMO antenna

Figures 17 and 18 show the radiation pattern, which depicts the three-dimensional emission and absorption patterns of electromagnetic waves as they travel through an antenna. It demonstrates the variation in radiated power as a function of beam direction24. The letters “XY,” “YZ,” and “ZX” indicate the antenna orientations and the corresponding planes on which the radiation pattern is observed when describing the pattern on different planes. An antenna’s electric field can be seen in its E-field radiation pattern, which plots the field’s direction and strength against the antenna’s azimuthal angle (phi). The patterns of emission from an antenna’s magnetic field (H-field) provide light on why the strength and direction of the field change as a function of the polar angle (theta). The far-field radiation patterns presented in Figs. 17 and 18 reveal critical antenna performance characteristics at millimeter-wave frequencies of 28 GHz and 38 GHz. At 28 GHz, the E-field radiation demonstrates a dominant main lobe with 23.7 dB(V/m) magnitude at 0.0° direction (broadside) in the horizontal plane (Phi = 0°), exhibiting a moderate 3 dB beamwidth of 44.3° and well-controlled side lobes at − 16.6 dB. A secondary lobe appears at 147.0° with a significantly lower magnitude (− 79.1 dB(V/m)). The H-field patterns at this frequency show maximum radiation of 10.7 dB(V/m) at 90.0° elevation with 35.9° beamwidth. At 38 GHz, the radiation patterns exhibit narrower beam characteristics, with the E-field showing 18.3 dB(V/m) gain at 90.0° elevation and a reduced 3 dB beamwidth of 29.6°, though with elevated side lobe levels of 5.5 dB. The H-field radiation at 38 GHz is comparatively weaker, peaking at − 28.6 dB(A/m) with 44.5° beamwidth. These measurements indicate that while the 28 GHz configuration offers superior gain and side lobe suppression for broadside radiation, the 38 GHz operation provides tighter beam focusing at the cost of increased side lobe interference. The radiation pattern that has been measured is quite remarkable since it closely resembles the simulated result. This indicates that the simulation has been successful in replicating the real-world scenario with a high degree of accuracy. The similarity between the measured and simulated radiation patterns is indeed impressive and points towards the effectiveness of the simulation process.

Figure 19 presents the radiation patterns of the antenna at two key millimeter-wave frequencies, 28 GHz and 38 GHz, for both the E-plane and H-plane. The patterns include simulated and measured results for co-polarization and cross-polarization components.

In the E-plane, the antenna demonstrates a focused and directive main lobe at 28 GHz, with the simulated co-polarization closely matching the measured data. The cross-polarization levels remain significantly lower, indicating good polarization purity and minimal unwanted radiation. At 38 GHz, the main lobe broadens slightly, and more fluctuations appear in the side lobes, reflecting the increased sensitivity of the antenna structure to higher frequency effects such as material properties and fabrication imperfections. Despite these variations, the measured co-polarization remains in good agreement with simulations, and cross-polarization levels are still well suppressed, albeit slightly elevated compared to 28 GHz. The H-plane radiation patterns reveal broader beam widths at both frequencies, consistent with the magnetic field orientation. At 28 GHz, the simulated and measured co-polarization patterns align closely, showing minor ripples likely due to the antenna’s aperture and element arrangement25. The cross-polarization components remain low, affirming the antenna’s effectiveness in maintaining polarization purity. At 38 GHz, the co-polarized main lobe becomes broader with more pronounced fluctuations, indicating the influence of higher-frequency resonance and structural sensitivity. Measured results follow the general trend of simulations, with cross-polarization levels slightly increased but still within acceptable limits.

2. RLC equivalent circuit

To understand the electromagnetic behavior of the antenna through circuit-based analysis, an equivalent RLC circuit model is developed26. This section outlines the modeling methodology and compares results with full-wave simulations.

As a conducting element, an antenna exhibits electric characteristics, including resistance, capacitance, and inductance, which can be represented by an electric circuit comprising a resistor, capacitor, and inductor27. It is very important to understand the antenna’s electrical characteristics as the antenna is incorporated into RF circuits. Figure 20 shows that the antenna is divided into several rectangular parts. Some complex parts are ignored, as this circuit represents an approximation and does not thoroughly illustrate the complex current distribution within the antenna. As the full circuit of the antenna is very elaborate, we have represented the circuit as blocks.

The equivalent circuit model is developed using Advanced Design System (ADS), a circuit and system simulation software developed by Keysight Technologies (Version: ADS 2019; URL: https://www.keysight.com/us/en/products/software/pathwave-design-software/pathwave-advanced-design-system.html). Figure 21 shows the equivalent circuit of the single-element antenna. Figure 22a,b illustrate the equivalent block circuit model of the array and MIMO antenna, respectively. Table 2 presents the component values for the resistors, inductors, and capacitors. The comparison between the reflection coefficient values obtained from CST Studio Suite 2019 (developed by Dassault Systèmes; URL: https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/cst-studio-suite/) and ADS simulations reveals some key differences, shown in Fig. 23. The operating range of the antenna is 26.1 to 31 GHz and 35.1 to 40 GHz, with a return loss of − 31 dB and − 32 dB resonating at 27.45 GHz and 37.5 GHz, as per ADS, respectively. The CST simulated bandwidths of the MIMO antenna are 2.55 GHz (26.73–29.28 GHz) and 5.77 GHz (34.96–40.73 GHz). Overall, CST generally predicts stronger resonance with deeper dips in the reflection coefficient, suggesting better impedance matching, while ADS provides slightly less pronounced variations.

3. Machine learning (ML) based optimization

Machine learning (ML) surpasses electromagnetic (EM) software, transforming antenna design. A key advantage is the significantly reduced computational time. Conventional EM solvers such as FEM and FDTD require numerous hours or even days to run. Once trained, ML models can predict antenna performance instantly, allowing for quick design changes28. This speed is crucial for rapid prototyping in sectors like telecommunications, aerospace, and IoT. The advantages of using ML compared to conventional EM software are as follows:

-

(1)

Another advantage is the efficiency in navigating extensive design spaces. Traditional approaches involve manual adjustments and repetitive simulations, which can be time-consuming and may not lead to optimal designs.

-

(2)

ML enables engineers to assess antenna performance up front, with the model autonomously generating a design that meets specified criteria. In traditional EM solvers, users typically have to make iterative adjustments and analyze results.

-

(3)

ML models demonstrate greater resilience to variations in the real world. Traditional EM solvers operate under ideal conditions, whereas real-world manufacturing considers material properties, fabrication tolerances, and environmental influences.

-

(4)

Ultimately, ML facilitates multi-objective optimization, allowing for a balance among design criteria, unlike traditional EM solvers, which optimize one or two parameters at a time and require multiple simulation cycles.

3.1 Antenna optimization through heat map

Antenna optimization relies heavily on heat maps, which graphically depict critical performance indicators such as radiation patterns, surface current density, and electromagnetic field dispersion. Engineers can improve efficiency, gain, and bandwidth by examining these heat maps to find high-intensity areas and then adjusting feed placements, antenna dimensions, and optimization29. The graphic presents a correlation heat map that examines the relationships between various factors. In this map, dark blue represents strong positive correlations (close to 1), while lighter shades or negative values indicate weaker or inverse associations. The intensity of the colors reflects both the strength and direction of the correlations. Each variable is perfectly correlated with itself, which is why the diagonal values are all 1. Notably, while “gain” and “L4” exhibit a negative correlation (− 0.31), there are also significant positive correlations, such as between “gain” and “sl3” (0.29) and “gain” and “pw” (0.2), suggesting modestly positive relationships as illustrated in Fig. 24.

3.2 Preparing data sets

The CST simulator creates a model and generates a dataset for the antenna design30. This dataset is produced by varying the gap between patches, 50-Ω feed width, Patch length, Patch width, and Slot 3 length of the MIMO antenna. The output generated includes the gain parameter for one or multiple frequencies, as depicted in Table 3. The image is a flow diagram that illustrates how a machine learning model forecasts Gain based on various input factors. The inputs include the gap between patches, 50-Ω feed width, patch length, patch width, and slot three length. The primary machine learning model processes these parameters to determine Gain, which is shown as an output in a purple descending triangle, as illustrated in Fig. 25. This organized flow highlights the influence of antenna design parameters on the resultant Gain, likely within the fields of RF engineering or antenna optimization through machine learning.

3.3 Methodology of ML in antenna

Stage 1: Machine learning models require sufficient data to identify relationships and patterns. By utilizing 80% of the dataset for training, the sample size increases, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to generalize.

Stage 2: The purpose of allocating 20% of the dataset for testing is to evaluate the machine learning model’s ability to generalize to unfamiliar data. This approach ensures that the model performs well not just on the training data but also on new antenna configurations that it has not encountered before.

Stage 3: The model undergoes accuracy testing with a 20% test dataset following the training phase. Performance metrics such as Mean Squared Error (MSE), R2 Score, and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) are utilized to evaluate the results. Our trained model is assessed against predefined accuracy thresholds. If the model meets or surpasses these expectations, it is deemed suitable for deployment. However, if the accuracy falls short, the process revisits Stage 2 to explore various machine learning algorithms or tuning methods to enhance performance.

Stage 4: Several machine learning (ML) methods, including Extra Tree, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting, Decision Tree, and Random Forest, are utilized to train on the dataset to predict antenna performance, as depicted in Fig. 26. The trained models are later evaluated for accuracy to determine the most effective algorithm. After the assessment, the most effective ML algorithm is selected for final predictions. This workflow outlines a systematic strategy for employing machine learning in antenna optimization, ensuring that parameter modifications are effectively integrated and leveraged to enhance antenna performance31. The thorough evaluation process guarantees the use of the most accurate and reliable model for future predictions, further improving antenna design through data-driven insights.

3.4 Selection of algorithm

While traditional antenna design typically relies on regression analysis, we enhance both accuracy and efficiency by incorporating five valuable machine learning (ML) regression models into our methodology. This approach allows us to capture both linear and nonlinear relationships between antenna parameters and performance metrics such as gain, bandwidth, efficiency, and return loss. By leveraging a comprehensive evaluation enabled by this multi-model strategy, we ensure the selection of the most suitable ML model for antenna design.

3.4.1 Random forest regression

Random Forest Regression is an ensemble learning technique that combines multiple decision trees to improve prediction accuracy and robustness32. It is widely used in optimizing antenna designs to predict performance indicators such as gain, bandwidth, radiation efficiency, and return loss.

3.4.2 Decision tree regression

Decision Tree Regression systematically partitions data to capture the relationships between input features and a continuous target variable33. By identifying trends in design parameters, it aids in predicting optimization metrics for antenna designs, such as gain, bandwidth, and efficiency. The tree structure makes it straightforward to interpret how various antenna parameters influence performance. Although Decision Tree Regression can be prone to overfitting, techniques like pruning or employing ensemble methods such as Random Forest Regression can improve its generalization and accuracy.

3.4.3 Extreme gradient boosting

XGBoost is an advanced gradient-boosting technique widely utilized in machine-learning competitions and various real-world applications34. It enhances traditional Gradient boosting by incorporating L1 and L2 regularization to mitigate overfitting. With features such as parallel processing, tree pruning, and effective handling of missing values, XGBoost offers improved speed and robustness compared to other boosting algorithms. Its accuracy and scalability make it a popular choice for applications like fraud detection, recommendation systems, and financial modeling.

3.4.4 Extra tree regression

Extra Trees is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees using random splits rather than relying on information gain or Gini impurity. This additional level of randomization minimizes variability and enhances accuracy, positioning it as a viable alternative to Random Forests. Extra Trees are noted for their computational efficiency and proficiency in handling high-dimensional datasets, particularly those with significant noise. Consequently, they are frequently employed in robust and rapid feature selection tasks35.

3.4.5 Gradient boosting

Gradient Boosting builds models sequentially, addressing errors made by each preceding model. By iteratively optimizing a loss function to decrease bias, it differs from bagging, which focuses on reducing variance. This method combines weak learners, typically decision trees, to create a powerful predictive model. While gradient boosting is highly accurate, it may overfit if not tuned appropriately. It finds extensive applications in ranking systems, anomaly detection, and structured data predictions36.

3.5 Performance evaluation criteria for regression models

In antenna design, regression models are evaluated for their predictive accuracy in determining key performance metrics such as gain, radiation efficiency, bandwidth, and return loss. Common performance assessment measures include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), which gauge prediction discrepancies to ensure minimal inaccuracies in design approximations. R-squared and Variance Scores are used to assess the model’s effectiveness in explaining variations in antenna performance. At the same time, Mean Squared Error (MSE) calculates the average of the squared differences between predicted and actual values37. Given the nonlinear characteristics of antennas, it is essential to validate models through cross-validation procedures to confirm their generalizability across various design configurations. To evaluate the algorithms, we used the following statistical markers and compared the results:

-

Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

-

Mean Squared Error (MSE)

-

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

-

(R-squared) and

-

The variance score

Table 4 provides a summary of these measures along with the mathematical equations that apply to them. Every metric evaluates the effectiveness of a regression model by quantifying the difference between the values that were predicted and those that were observed in a variety of different ways.

3.6 Analysis of ML-based prediction results

This study evaluated multiple machine learning algorithms for their efficacy in forecasting antenna performance, with a particular emphasis on Gain factors. Table 5 summarizes and compares the forecasting ability of five regression models concerning the gain-given input parameters.

The error measures (MAE, MSE, RMSE) for several machine learning regression models—including Decision Tree, XGB, Extra Trees, Gradient Boosting, and Random Forest—are displayed in the bar chart. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is represented in red, Mean Squared Error (MSE) is in orange, and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is in green, which all indicate the performance of each model. The Extra Trees Regression model demonstrates the lowest errors, with a Mean Absolute Error of 14.04%, a Mean Squared Error of 4.42%, and a Root Mean Squared Error of 21.03%. This suggests that it performs better than the other models analyzed. In contrast, XGB Regression has the highest RMSE at 36.57%, indicating less accurate forecasts, as depicted in Fig. 27. While the Extra Trees Regression appears to be the best choice for minimizing prediction errors, the Random Forest Regressor and Gradient Boosting Regressor also show competitive performance.

The accuracy measures, specifically the R-squared and Variance Score, for various regression models—including Decision Tree, XGB, Extra Trees, Gradient Boosting, and Random Forest—are illustrated in the bar chart. The predictive performance of these models is evaluated using the R-squared score (depicted in blue) and the Variance Score (represented in red). Among them, Extra Trees Regression stands out with an R-squared of 92.99% and a Variance Score of 93.03%, showcasing its superior accuracy and ability to explain data variance effectively, as illustrated in Fig. 28. Gradient Boosting and Random Forest regressors also demonstrate commendable performance, with accuracy ratings ranging from 87.73 to 87.90%. In contrast, the XGB Regression model performs the least successfully, achieving an R-squared of 78.84% and a Variance Score of 79.39%. Overall, Extra Trees Regression proves to be the most consistent and reliable model for predicted accuracy.

The scatter plot illustrates the results of the Extra Regression Analysis, contrasting actual gains (x-axis) with projected gains (y-axis). The blue dots represent the training data, showcasing the model’s capacity to generalize across various data points. The red line indicates the regression line for the testing data, reflecting the relationship between actual and expected values. A strong alignment along the diagonal suggests a well-fitted model with high accuracy. However, some deviations, particularly at lower gain values, reveal slight inaccuracies or discrepancies in the forecasts, as shown in Fig. 29. This visualization is valuable for evaluating the model’s predictive performance and identifying potential areas for improvement.

During testing, we determined that the gain should ideally fall within the range of approximately 6.7 to 9 dB. Based on the data presented in Table 6, the simulated gain obtained through Extra Tree Regression closely aligns with the expected gain, showing minimal deviation between the predicted and target values. This graph provides a thorough comparison between the simulated gain (solid blue line) and the predicted gain (dashed red line) over several data points. The gain levels exhibit notable variation, oscillating between approximately 6.5 dB and 9 dB, which highlights the inconsistency in predictions. The close alignment of the two curves suggests that the predictive model accurately captures the fundamental patterns within the data, as illustrated in Fig. 30. However, slight deviations between the lines at specific points indicate minor inaccuracies or discrepancies in the projections. While the model demonstrates high effectiveness, further refinement may be necessary to improve its accuracy in areas experiencing significant fluctuations.

4. Analysis and comparative evaluation of performance

The proposed antenna design is analyzed in terms of key performance parameters, including return loss, gain, radiation pattern, and efficiency. Simulation and optimization techniques are employed to ensure the antenna meets the stringent requirements of modern mm-Wave communication systems. The results demonstrate the potential of the proposed design for future wireless applications, including 5G networks, IoT, and high-speed data transmission. The integration of MIMO technology in dual-band antennas operating at 28 and 38 GHz has drawn significant attention for 5G communication due to its ability to enhance data throughput, improve link reliability, and mitigate multipath fading. Numerous designs have been proposed using different substrate materials, configurations, and performance optimization strategies. The following literature review presents a critical assessment of existing works, identifying both their contributions and limitations and concluding with the advantages of the proposed design. The study in38 employs Rogers RT5880 substrate in a 4-port dual-band antenna resonating at 28 and 38 GHz, with respective bandwidths of 1 GHz and 1.2 GHz. With a board size of 2.24λ0 × 2.1λ0, it achieves 7.1 dB and 7.9 dB gain, isolation greater than 27 dB, and a very low ECC of < 0.001, alongside efficiency above 85%. However, the gain could still be improved for long-distance communication, and the absence of ML or RLC limits performance optimization. In39, a 4-port antenna using Duroid 5880 substrate demonstrates better bandwidths of 1.39 GHz and 3.33 GHz but a relatively large size of 3.87λ0 × 0.93λ0. The design achieves 5.59 and 5.7 dB gain and isolation over 25 dB, with low ECC (< 0.001) and high DG (> 9.96). While the ECC and diversity gain are strong, the gain remains moderate, limiting its coverage performance. Hasan et al.40 presents a 2-port antenna with a compact 1.3λ0 × 2.42λ0 footprint on Duroid 5880 substrate. Despite its relatively good bandwidths of 2.55 GHz and 2.1 GHz, the gain is very low (1.27 and 1.83 dB). Though it offers strong isolation (> 20 dB), excellent ECC (< 0.001), and high DG (> 9.99), the low gain and efficiency values (78% and 76%) are significant drawbacks for practical deployment. The design in41 uses Rogers 5880 substrate in a 4-port configuration with moderate bandwidths of 1.06 GHz and 1.43 GHz. It provides 7.95 dB and 8.27 dB gain, isolation over 26 dB, and ECC < 0.001, with an efficiency of 88.25%. However, the very large board size (5.13λ0 × 10.2λ0) makes it unsuitable for compact devices despite its relatively high gain. The antenna in42 uses Rogers RO3003TM and is compact (0.7λ0 × 0.82λ0) in a 2-port setup. It operates with bandwidths of 1.23 GHz and 1.06 GHz and achieves 6.6 dB and 5.86 dB gain, with strong isolation (> 28 dB). Although ECC (< 0.005) and DG (< 9) are within acceptable limits, the performance is average due to lower gain and moderate efficiency (80%, 85%). In43, a 4-port antenna on RT5880 achieves respectable bandwidths of 2.4 GHz and 2 GHz, with gains of 8.4 dB and 6.02 dB and good isolation (> 25 dB). The design has a balanced size (1.23λ₀ × 1.23λ₀) and high efficiencies (91.7%, 88.6%), along with solid ECC (0.005) and DG ≈10. However, no ML or RLC methods were applied, which could have further improved bandwidth tuning and isolation control. The work in44 uses FR4 substrate, covering wider frequency spans (24–28 GHz and 37–40 GHz) with bandwidths of 4 GHz and 3 GHz. While gain at 28 GHz is 7.8 dB, it drops to 4.4 dB at 38 GHz, and efficiency is low (65% and 49%). The ECC of 0.01 and high DG (9.99) suggest reasonable MIMO potential, but the use of FR4 results in high dielectric loss, negatively affecting efficiency and gain. The study in45 uses RT5880 substrate in a 2-port antenna with impressive bandwidths of 4.8 GHz and 4.2 GHz, excellent isolation (> 30 dB and > 28 dB), and compact size (0.82λ0 × 1.6λ0). The design offers 7.8 dB and 6 dB gain, ECC of 0.0001, and DG > 9.99. While the antenna delivers solid performance, the efficiency is not reported, and no ML or RLC-based optimization is used. The study in46 utilizes a Rogers RO3003 substrate for a 4-port MIMO antenna operating at 28 and 38 GHz, with dual-band bandwidths of 0.6 GHz and 0.6 GHz. Despite having modest bandwidths, the design delivers decent gains of 7.37 dB and 8.13 dB. However, it suffers from poor isolation (< 30 dB), extremely high ECC values (up to 5.999), and moderate efficiencies (88% and 88.6%). The design does not incorporate machine learning or RLC optimization and lacks strong isolation or ECC control, limiting its MIMO performance. In47, the authors also target the 28 and 38 GHz bands with a 4-port MIMO antenna based on Rogers 3003 substrate. The bandwidths are improved slightly to 0.72 GHz and 0.5 GHz, while gains of 4.15 dB and 7.73 dB are achieved. The antenna shows better isolation (> 20 dB) and significantly lower ECC (< 0.03), but the overall efficiency remains moderate (80.13% and 85.44%). It also lacks ML or circuit-based performance tuning and presents limited bandwidth and gain. In48, the authors introduced an antenna operating at 28 GHz using a Rogers RT5880 substrate. The design offers a bandwidth of 0.658 GHz, which is limited considering the high-frequency operation. The antenna achieves a gain of 7.63 dB and a reasonable efficiency of 89.66%. The integration of machine learning contributed to performance optimization and design refinement. In49, a two-port MIMO antenna was developed on Rogers RT5880, resonating at 27.75 GHz with an operating range from 27.5 to 28.35 GHz. The achieved bandwidth is 0.85 GHz, which is notably low for MIMO systems targeting high data throughput. Although the antenna provides a high gain of 10 dB, the isolation between the two ports is just over 19 dB, indicating poor mutual decoupling. Machine learning techniques were applied to aid the design process. The study in50 proposed a dual-band MIMO antenna operating at 28 GHz and 34 GHz, fabricated on Duroid 5880 substrate. The antenna covers narrow bandwidths of 0.88 GHz and 0.66 GHz at the respective bands, which limits spectral flexibility. It delivers gains of 8.75 dB and 5.5 dB, where the second band shows relatively poor gain performance. However, the antenna demonstrates excellent isolation characteristics, exceeding 30 dB and 23 dB, along with very low ECC and near-ideal DG values. Machine learning was utilized effectively to enhance overall design outcomes. The proposed antenna, detailed in Table 7, presents a 4-port MIMO configuration operating at 28 and 38 GHz, with wide bandwidths of 2.55 GHz and 5.77 GHz across the ranges 26.73–29.28 GHz and 34.96–40.73 GHz, respectively. Fabricated on Rogers RT5880, it achieves high gain values of 9 dB and 8.4 dB, with excellent isolation (> 35 dB at 28 GHz and > 29 dB at 38 GHz). The antenna maintains low ECC (< 0.001) and high DG (> 9.99), indicating superior MIMO performance. Additionally, it exhibits outstanding efficiency above 98% and 99% in both bands. By combining compact geometry (2.92λ0 × 2.92λ0) with advanced optimization methods, the proposed antenna effectively overcomes the drawbacks of earlier designs, such as low gain, limited isolation, or lack of adaptability, making it a strong candidate for high-efficiency, wideband 5G dual-band MIMO applications. Unlike previous designs, this antenna incorporates both machine learning (ML) and RLC circuit modeling, enabling fine-tuning of performance parameters such as bandwidth, isolation, and gain.

Conclusion

This study successfully presents the design and optimization of a high-performance dual-band MIMO antenna, which operates at 28 GHz and 38 GHz, targeting the demands of next-generation wireless communication systems beyond 5G. By evolving from a single-element design to more advanced array and MIMO configurations, the study addresses key challenges faced by mm-Wave systems, such as high path loss, limited coverage, and multipath fading. Through the implementation of innovative techniques, including a star-shaped slot, geometric parameter optimization, and advanced isolation methods like DGS and EBG structures, the antenna’s gain, efficiency, and isolation characteristics were significantly improved. The proposed four-port MIMO system achieved remarkable performance metrics, including isolation over 30 dB, an ECC value below 0.0002, and a diversity gain close to the ideal 10 dB. Furthermore, the use of five machine-learning algorithms to predict antenna gain demonstrated that Extra Trees Regression holds the most promise for accurate prediction, further enhancing the design process. The next phase of research will focus on validating simulated results with real-world data through antenna fabrication. Additionally, the integration of metamaterials is a promising direction to enhance further the antenna’s efficiency, gain, and bandwidth. The results from this study are pivotal for advancing communication technologies and demonstrate the antenna’s potential for applications in 5G, IoT systems, and future terahertz-based communication networks. This work not only highlights the antenna’s suitability for high data rate and low latency applications but also lays the groundwork for future improvements that could reshape the landscape of smart communication infrastructures.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Imam-Fulani, Y. O. et al. 5G frequency standardization, technologies, channel models, and network deployment: Advances, challenges, and future directions. Sustainability 15(6), 5173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065173 (2023).

Cuneray, K., Akcam, N., Okan, T. & Arican, G. O. 28/38 GHz dual-band MIMO antenna with wideband and high gain properties for 5G applications. AEU-Int. J. Electron. C. 162, 154553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeue.2023.154553 (2023).

Al-Atyar, R. A., Farahat, A. E., Hussein, K. F. A., Shaalan, A. A. & Ahmed, M. F. Dual-band (28/38 GHz)–loaded patch antenna for millimeter-wave communication. J. Infrared Milli. Terahz. Waves 46(3), 22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10762-025-01036-w (2025).

Gustavsson, U., Johansson, M., Athley, F. & Zaidi, A. Challenges of millimeter-wave active antenna systems in 5G. In: 12th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP 2018), London, UK: Institution of Engineering and Technology, 2018, 581 (5 pp.)-581 (5 pp.). https://doi.org/10.1049/cp.2018.0940.

Upadhyaya, T. et al. Quad-port MIMO antenna with high isolation characteristics for sub 6-GHz 5G NR communication. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 19088. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46413-4 (2023).

Rai, J. K. et al. High-gain triple-band t-shaped dielectric resonator based hybrid two-element MIMO antenna for 5G new radio, Wi-Fi 6, V2X, and C-band applications with a machine learning approach. Int. J. Commun. 38(5), e6038. https://doi.org/10.1002/dac.6038 (2025).

Nahin, K. H. et al. Performance prediction and optimization of a high-efficiency tessellated diamond fractal MIMO antenna for terahertz 6G communication using machine learning approaches. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 4215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88174-2 (2025).

Ghewari, P. & Patil, V. Advancements in microstrip patch antenna design using nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization algorithms: A systematic review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-025-10254-3 (2025).

Patel, U. & Upadhyaya, T. Four-port dual-band multiple-input multiple-output dielectric resonator antenna for sub-6 GHz 5G communication applications. Micromachines 13(11), 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi13112022 (2022).

Girjashankar, P. R., Upadhyaya, T. & Desai, A. Multiband hybrid MIMO DRA for Sub-6 GHz 5G and WiFi-6 applications. Int. J. RF Microw. Comput. Aided Eng. 32(12), e23479. https://doi.org/10.1002/mmce.23479 (2022).

Ding, X.-H., Ji, C., Yang, J.-Y., Yang, W.-W. & Chen, J.-X. A compact dual-polarized endfire dielectric resonator antenna for 5G millimeter-wave terminal. Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 24(5), 1288–1292. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2025.3534655 (2025).

Gaid, A. S. A., Ali, M. A. M., Saif, A. & Mohammed, W. A. A. Design and analysis of a low profile, high gain rectangular microstrip patch antenna for 28 GHz applications. Cogent Eng. 11(1), 2322827. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2024.2322827 (2024).

Wu, Q., Chen, W., Yu, C., Wang, H. & Hong, W. Machine-learning-assisted optimization for antenna geometry design. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat. 72(3), 2083–2095. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2023.3346493 (2024).

Koziel, S., Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. & Leifsson, L. Antenna optimization using machine learning with reduced-dimensionality surrogates. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 21567. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72478-w (2024).

Al-Bawri, S. S. et al. Machine learning technique based highly efficient slotted 4-port MIMO antenna using decoupling structure for sub-THz and THz 6G band applications. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(10), 1611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-024-07249-y (2024).

Haque, M. A. et al. Multiband THz MIMO antenna with regression machine learning techniques for isolation prediction in IoT applications. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 7701. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89962-6 (2025).

Rahman, M. A., Al-Bawri, S. S., Abdulkawi, W. M. & Islam, M. T. Miniaturized tri-band integrated microwave and millimeter-wave MIMO antenna loaded with metamaterial for 5G IoT applications. Results Eng. 24, 103130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103130 (2024).

Kumar, P. et al. A compact quad-port UWB MIMO antenna with improved isolation using a novel mesh-like decoupling structure and unique DGS. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 70(3), 949–953. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2022.3220542 (2023).

Rahman, M. A. et al. 3D highly isolated 6-port tri-band MIMO antenna system with 360° coverage for 5G IoT applications based machine learning verification. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 204. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84010-1 (2025).

Haque, Md. A. et al. Machine learning-based technique for gain prediction of mm-wave miniaturized 5G MIMO slotted antenna array with high isolation characteristics. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 276. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84182-w (2025).

Prabhu, P. An integrated independent antenna system for multiradio wireless communication applications. Wirel. Netw. 31(4), 3205–3222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11276-025-03938-y (2025).

Dhananjeyan, R., Ramesh, S., Kumar, D. R. & Kumar, O. P. Compact octagonal MIMO antenna system for broadband applications with enhanced isolation and wideband performance. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 18921. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03494-7 (2025).

Kang, M.-J., Park, J., Heo, H., Qu, L. & Jung, K.-Y. CMA-based design of a novel structure for isolation enhancement and radiation pattern correction in MIMO antennas. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84793-3 (2025).

Rahman, M. A., Al-Bawri, S. S., Abdulkawi, W. M., Aljaloud, K. & Islam, M. T. A unique SWB multi-slotted four-port highly isolated MIMO antenna loaded with metasurface for IOT applications-based machine learning verification. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 50, 101616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2024.101616 (2024).

Kumar, A., Pattanayak, P., Verma, R. K., Sabat, D. & Prasad, G. Two-element MIMO antenna system for multiband millimeter-wave, 5G mobile communication, Ka-band, and future 6G applications with SAR analysis. AEU-Int. J. Electron. C. 171, 154876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeue.2023.154876 (2023).

Roula, S. et al. A dual-band quad-element MIMO antenna covering wide bandwidth in 5G new radio and mm-wave bands with equivalent circuit analysis. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-025-10037-9 (2025).

Yadav, P., Yadav, V., Ansari, J. A., Singh, V. & Mishra, B. An equivalent circuit and analysis of reconfigurable antenna for penta-band wireless applications. Phys. Scr. 100(6), 065509. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/add216 (2025).

Sarker, N., Podder, P., Mondal, M. R. H., Shafin, S. S. & Kamruzzaman, J. Applications of machine learning and deep learning in antenna design, optimization, and selection: A review. IEEE Access 11, 103890–103915. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3317371 (2023).

Semov, P., Koleva, P., Dandanov, N., Poulkov, V. & Asenov, O. Performance optimization in heterogeneous wireless access networks based on user heat maps. In: 2018 41st International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Athens: IEEE, 2018, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2018.8441319.

Kumar Rai, J. et al. Dual-band miniaturized composite right left handed transmission line ZOR antenna for microwave communication with machine learning approach. AEU Int. J. Electron. Commun. 176, 155120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeue.2024.155120 (2024).

Haque, Md. A. et al. Machine learning based compact MIMO antenna array for 38 GHz millimeter wave application with robust isolation and high efficiency performance. Results Eng. 25, 104006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104006 (2025).

Borup, D., Christensen, B. J., Mühlbach, N. S. & Nielsen, M. S. Targeting predictors in random forest regression. Int. J. Forecast. 39(2), 841–868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2022.02.010 (2023).

Shi, M. et al. Ensemble regression based on polynomial regression-based decision tree and its application in the in-situ data of tunnel boring machine. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 188, 110022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2022.110022 (2023).

Alam, S. M. K., Li, P., Rahman, M., Fida, M. & Elumalai, V. Key factors affecting groundwater nitrate levels in the Yinchuan Region, Northwest China: Research using the eXtreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) model with the SHapley additive exPlanations (SHAP) method. Environ. Pollut. 364, 125336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.125336 (2025).

Sudhamathi, T. & Perumal, K. Ensemble regression based Extra Tree Regressor for hybrid crop yield prediction system. Meas. Sens. 35, 101277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measen.2024.101277 (2024).

Boldini, D., Grisoni, F., Kuhn, D., Friedrich, L. & Sieber, S. A. Practical guidelines for the use of gradient boosting for molecular property prediction. J. Cheminform. 15(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-023-00743-7 (2023).

Haque, M. A. et al. Machine learning-based novel-shaped THz MIMO antenna with a slotted ground plane for future 6G applications. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 32162. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79332-z (2024).

Raheel, K. et al. E-shaped H-slotted dual band mmWave antenna for 5G technology. Electronics 10(9), 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10091019 (2021).

Rafique, U., Agarwal, S., Nauman, N., Khalil, H. & Ullah, K. Inset-fed planar antenna array for dual-band 5G MIMO applications. PIER C 112, 83–98. https://doi.org/10.2528/PIERC21021302 (2021).

Hasan, M. N., Bashir, S. & Chu, S. Dual band omnidirectional millimeter wave antenna for 5G communications. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 33(12), 1581–1590. https://doi.org/10.1080/09205071.2019.1617790 (2019).

Marzouk, H. M., Ahmed, M. I. & Shaalan, A.-E.H. Novel dual-band 28/38 GHZ MIMO antennas for 5G mobile applications. PIER C 93, 103–117. https://doi.org/10.2528/PIERC19032303 (2019).

Farahat, A. E. & Hussein, K. F. A. Dual-band (28/38 GHz) wideband MIMO antenna for 5G mobile applications. IEEE Access 10, 32213–32223. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3160724 (2022).

Tadesse, A. D., Acharya, O. P. & Sahu, S. A compact planar four-port MIMO antenna for 28/38 GHz millimeter-wave 5G applications. AEM 11(3), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.7716/aem.v11i3.1947 (2022).

Kumar, A., Mahto, S. K., Sinha, R. & Choubey, A. Dual circular slot ring triple-band MIMO antenna for 5G applications. Frequenz 75(3–4), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1515/freq-2020-0138 (2021).

Khan, D., Ahmad, A. & Choi, D.-Y. Dual-band 5G MIMO antenna with enhanced coupling reduction using metamaterials. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50446-0 (2024).

Elsharkawy, R. R., Hussein, K. F. A. & Farahat, A. E. Dual-band (28/38 GHz) compact MIMO antenna system for millimeter-wave applications. J. Infrared Milli. Terahz. Waves 44(11–12), 1016–1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10762-023-00943-0 (2023).

Tiwari, R. N., Sharma, D., Singh, P. & Kumar, P. A flexible dual-band 4 × 4 MIMO antenna for 5G mm-wave 28/38 GHz wearable applications. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 14324. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65023-2 (2024).

Rana, M., Rabiul Islam, S. M. & Sarker, S. Machine learning based on patch antenna design and optimization for 5G applications at 28GHz. Results Eng. 24, 103366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103366 (2024).

Rai, J. K. et al. Machine learning-enabled two-port wideband MIMO hybrid rectangular dielectric resonator antenna for n261 5G NR millimeter wave. Int. J. Commun. 37(16), e5898. https://doi.org/10.1002/dac.5898 (2024).

Dwivedi, A. K. et al. A taguchi neural network–based optimization of a dual-port, dual-band MIMO antenna encompassing the 28/34 GHz millimeter wave regime. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 6026. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90103-2 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R749), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The author would also like to acknowledge by King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Saudi Arabia

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A.A: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, M.A. H: Supervision, Project Administration, Writing - Original Draft, G.A: Funding Acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing, M.S. A: Software, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft, M.K. A: Simulation, Data Collection N.S.S.S: Methodology, Review, M.A. R Literature Review, H. S: Review of Results. A: Statistical Analysis, A.A. A: Critical Review, Theoretical Framework, Final Approval of Manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ananta, R.A., Haque, M.A., Alyami, G. et al. Regression machine learning-based highly efficient dual band MIMO antenna design for mm-Wave 5G application and gain prediction. Sci Rep 15, 28730 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13514-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13514-1

This article is cited by

-

A Novel Isolation-Enhanced Four-Element High-Gain Hexa-Band MIMO Antenna for 5G mmWave Systems

Wireless Personal Communications (2026)

-

Predictive modelling and high-performance enhancement smart thz antennas for 6 g applications using regression machine learning approaches

Scientific Reports (2025)