Abstract

Messenger RNA (mRNA) from high-risk genotypes of human papillomavirus (hrHPV) is a more specific biomarker for cervical cancer risk than hrHPV DNA due to its ability to differentiate clinically significant infections from transient ones. Detecting mRNA from exfoliated cervical cells, however, is a complex, expensive, and equipment-intensive process, making it infeasible in resource-limited settings. Here we describe a sensitive, specific, and minimally instrumented method to detect HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 mRNA in exfoliated cervical cells. First, reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification (RT-RPA) exo assays were designed to amplify and detect HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 E7 mRNA ≥100 copies per reaction in real time using a portable fluorimeter, which is on par with the only FDA-approved hrHPV mRNA test. Next, an extraction-free sample preparation method using only an enzymatic reaction was developed to lyse cells and degrade cellular DNA in cultured HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45-positive cells. The RT-RPA assays specifically amplified mRNA from this crude lysate across a clinically relevant range of concentrations. Eleven cervicovaginal samples were tested at the point of care using these methods and showed 100% agreement between RT-RPA and RT-qPCR results, including two samples that were positive for HPV16 mRNA. Additionally, nine negative samples spiked with HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45-positive cells successfully detected each respective HPV type. In total, this prototype assay has potential to make sensitive and specific hrHPV mRNA testing more accessible in resource-limited settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer is highly preventable through vaccination, cervical screening and treatment of precancerous lesions before they progress to invasive cancer1. Regular screening is associated with a 67% reduction in early stage cancer and a 95% reduction in advanced stage cancer2. In many low and middle-income countries (LMICs), however, few women are screened for cervical cancer due to limitations including high testing cost, inadequate laboratory infrastructure, and a lack of trained providers and laboratory technicians3. For this reason, patients are often not diagnosed until they present with symptoms due to advanced disease when chances of survival are lower4,5,6. As a result, cervical cancer incidence and mortality are disproportionately high in LMICs, where approximately 90% of global cervical cancer related deaths occur7.

Persistent high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) infection is the cause of virtually all cervical cancer8. Together, HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 are responsible for about 75% of cervical cancer cases globally9. Most hrHPV infections are transient, clearing rapidly without clinical intervention10. When infections with hrHPV types persist, however, it is more likely that precancerous cervical lesions will form and progress to invasive cervical cancer without treatment11. In LMICs, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends hrHPV DNA testing as the primary screening method for countries implementing a screen-and-treat approach, in which all patients who test positive are preemptively treated for cervical precancer12. hrHPV DNA tests are sensitive for identifying patients who may be at risk for cervical cancer, but screen-and-treat programs that rely solely on a positive hrHPV DNA test can lead to overtreatment since many infections clear naturally13,14.

hrHPV mRNA is a more specific biomarker for identifying patients with cervical precancer and is useful as a screening or triage test, especially in areas with limited capacity for diagnostic cervical biopsy and histology15,16,17,18,19. hrHPV mRNA tests detect hrHPV E6 or E7 oncogene expression, a key part of the cervical cancer progression pathway, which is associated with higher risk of cancer20,21,22. While low levels of E6 and E7 mRNA expression are necessary for genomic maintenance, higher levels are due to gene expression dysregulation and are a hallmark of cervical precancer and cancer. A meta-analysis of the performance of hrHPV DNA and mRNA tests shows that mRNA testing has similar sensitivity to DNA testing, but higher specificity to DNA testing for the detection of high-grade precancerous cervical lesions23,24,25. The WHO suggests that hrHPV mRNA tests may be used in cervical cancer screening programs with 5-year screening intervals26. There is also evidence to suggest that hrHPV mRNA-based screening programs may be more cost-effective than DNA-based screening programs, in part due to more efficient allocation of resources to patients most at risk for cervical cancer27.

Despite the apparent benefits, there are major limitations to widespread implementation of hrHPV mRNA testing in cervical cancer screening programs. First, there are very few commercially available tests, only one of which is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)28 That test, Aptima HPV (Hologic), requires expensive equipment and infrastructure, including precise ambient temperature control, a freezer, a refrigerator, a stable electricity supply with back-up power, and trained laboratory personnel to run the test. A cost-reduction program is available for low-income countries, but the per-test cost is still prohibitively expensive in many contexts at 12 USD per test29. Other tests, such as PreTect HPV Proofer (MelMont Medical), NucliSens EasyQ HPV (bioMérieux), QuantiVirus HPV mRNA Test (DiaCarta), and HPV OncoTect E6, E7 mRNA test (IncellDx) have been used in pilot studies but require significant infrastructure, such as fluorescence plate readers, flow cytometers, and trained laboratory technicians30,31,32,33. The limited availability, high cost, significant infrastructure requirements, and need for trained personnel make screening with mRNA infeasible in most resource-limited settings34.

Sample preparation is one of the main limitations to deploying nucleic acid testing in resource-limited settings and is an especially significant challenge for tests that detect RNA, which degrades easily outside of cells and is challenging to isolate from cellular DNA35. Traditional RNA sample preparation methods, such as column-based extraction and magnetic bead-based separation, are time-consuming, expensive, and require many user steps and pieces of equipment (including high-speed centrifuges, specialized magnets, or thermal mixers), making them incompatible for use in resource-limited settings36. For example, one such column-based extraction kit requires eleven separate steps to purify total RNA from cultured cells, including addition of various buffers, centrifuging the sample through multiple purification columns, wash steps, and the addition of an RNA protection agent37. While significant advances have been made to develop extraction-free RNA sample preparation for COVID-19 RNA assays, these methods are not applicable to detect mRNA expression from DNA viruses, like HPV. For HPV, viral DNA must be removed or degraded for accurate RNA detection since the DNA and RNA have identical sequences for the gene of interest (E7)38,39,40,41.

There is currently no available method for amplification of HPV mRNA that could be performed at the point of care and is as sensitive and specific as the Aptima HPV test. An RT-RPA assay for HPV16 and HPV18 mRNA was described previously, but was not as sensitive as Aptima and did not include an HPV45 or a sample adequacy control42. Additionally, a reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay (RT-LAMP) assay was recently described for the detection of HPV16 mRNA only43. Both assays relied on extracted total mRNA and did not demonstrate sample preparation methods that can be performed at the point-of-care. There are also no methods in the literature that describe detection of mRNA expression from an incorporated DNA virus, like HPV, that do not rely on RNA extraction.

Here, we demonstrate a novel testing method capable of detecting E7 mRNA from HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 in cervical cells that combines minimally instrumented sample preparation with isothermal RNA amplification and detection. The sample-to-answer workflow is shown in Fig. 1. To develop the assay, reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification (RT-RPA) isothermal nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) were first designed to amplify extracted total RNA in solution. We show that the test has a limit of detection of 100 copies of extracted hrHPV mRNA per reaction, similar to the FDA- approved Aptima HPV test, and is highly specific. It also incorporates a cellular control to ensure validity during clinical sample testing, which is a major contribution to the landscape of point-of-care hrHPV tests. Then, we developed and optimized an extraction-free mRNA sample preparation method in which DNA from crude cell lysate is degraded using only an enzymatic reaction. Next, we demonstrate that crude treated lysate from the extraction-free sample preparation procedure and NAAT are effective at preparing and detecting mRNA from whole cells and patient cervicovaginal samples spiked with HPV-positive cells. Finally, eleven prospectively-collected cervicovaginal samples from patients referred for diagnostic evaluation following a positive screening test were tested using this sample-to-answer method, nine of which were negative for hrHPV mRNA and two of which were positive for HPV16 mRNA. RT-RPA results agreed with gold standard RT-qPCR results, and most of the negative samples had low-grade pathology, when available, while the HPV16 mRNA-positive sample with associated vulvar pathology had high grade precancer. Nine additional HPV mRNA-negative samples were spiked with SiHa (HPV16), HeLa (HPV18), and MS751 (HPV45)-positive cell lines to demonstrate successful detection of all three HPV mRNA types in a cervicovaginal sample matrix.

Sample-to-answer workflow. A cervicovaginal sample is collected into a cell lysis buffer. The sample is then incubated with DNase I. Following incubation, the DNase I is inactivated with a stop solution and the treated lysate is added directly to RT-RPA reactions. The RT-RPA reactions are run on a portable benchtop fluorimeter and real-time results are generated. Created in BioRender.

Results

RT-RPA reaction optimization

Primers and a probe (see Table S1) previously designed for an HPV18 RPA exo reaction were screened with two different reverse transcriptases (RTs), Omniscript and SuperScript IV42,44. Between these, Omniscript RT with a 5-minute pre-reaction incubation resulted in more consistent amplification of HPV18 RNA at 100 copies per reaction. In the conditions without RT (i.e., indicating nonspecific amplification), 1/6 replicates of 10,000 copies HPV18 RNA amplified with a 5-minute pre-reaction incubation and 4/6 replicates amplified with a 10-minute pre-reaction amplification (data not shown), suggesting that a 5-minute incubation results in less nonspecific amplification.

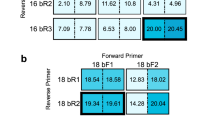

These conditions were then used in the design and optimization of the HPV16, HPV18, HPV45 and β-actin RT-RPA assays, which included evaluating various primer and probe sequences and combinations (workflow shown in Figure S1), the inclusion or omission of different reagents (extra dNTPs, RNase H, and helicase – shown in Figure S2), and the concentration of all reaction components (selected data shown in Figure S3).

RT-RPA assay sensitivity

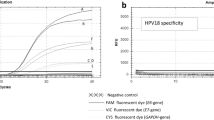

As shown in Fig. 2, the HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 RT-RPA assays consistently detected mRNA at and above 100 copies per reaction. The β-actin RT-RPA assay also detected mRNA at and above 100 copies per reaction (Figure S4). For all three reactions, 0/3 no target and 0/3 no RT control conditions amplified. The raw amplification data for HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 (Figure S5) informed a 15-minute reaction positivity time cutoff for extracted RNA and a 500 relative fluorescence units (RFU)/min amplification curve slope threshold to differentiate true amplification from nonspecific fluorescence. As target concentration increased, time to positivity decreased; a semilogarithmic linear least squares fit was performed for each data set.

HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 limits of detection. Time to positivity (min) for the (A) HPV16, (B) HPV18, and (C) HPV45 assays with samples containing 10, 100, 1,000, and 10,000 copies total RNA purified from SiHa, HeLa, and MS751 cells, respectively (n = 3 for all reactions). The limit of detection was identified as 100 copies per reaction in all three assays.

gBlocks of the E7 gene for 12 off-target high- and low-risk HPV types (6, 11, 31, 33, 35, 39, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68) as well as for HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 were diluted to 100,000 copies per µL (1 million copies per reaction) and tested separately in the RT-RPA reactions for HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45. As shown in Fig. 3, for each reaction, only the target of interest amplified, demonstrating hrHPV-type specificity for all assays.

RT-RPA Specificity. Fluorescence intensity measured in relative fluorescence units (RFU) vs. time for the HPV16 (A) and HPV18 (B), and HPV45 (C) RT-RPA assays performed with samples containing one million copies synthetic E7 gene fragments from 15 common high- and low-risk HPV types and a no-target control (NTC). Specific amplification was observed for all three hrHPV assays.

Development of an extraction-free sample preparation method for mRNA detection from crude cell lysate

An extraction-free sample preparation method was developed to amplify RNA from whole cells using only an enzymatic reaction. Because cells with hrHPV E7 mRNA also contain hrHPV E7 DNA with an identical sequence, it is necessary to remove or degrade the viral DNA prior to amplification to limit detection to mRNA expressed upon viral integration.

Osmotic shock in DEPC-treated water was used to lyse cells. As shown in Figure S6, there was a 95.7% reduction in intact cells following osmotic shock, indicating that almost all the cells were successfully lysed by suspension in DEPC-treated water.

As shown in Figure S7, when a cervicovaginal sample collected directly into DEPC-treated water was added to each of nine distinct DNase reactions labeled A-I, only the samples treated with DNase C did not exhibit amplification in the β-actin RPA assay without reverse transcriptase. This indicates that DNase C successfully degraded all the cellular DNA in the sample.

Limit of RNA detection and DNA degradation with DNase C

To test the preservation of RNA during the sample preparation process, extracted MS751 total RNA was treated with DNase C. After DNase deactivation with the stop solution, the treated RNA was added to both the HPV45 and β-actin RT-RPA assays. As shown in Figure S8A, HPV45 and β-actin mRNA were both detected down to 100 copies per reaction, indicating that there is no loss in sensitivity with this DNase reaction compared to the sensitivity reported in Fig. 2 with extracted RNA. Inconsistent detection occurred at 10 copies per reaction. There was no discernible difference in assay sensitivity between samples that were heat-deactivated following the addition of stop solution and those that were not heat-deactivated, indicating that addition of the stop solution alone was sufficient and that heat deactivation was not needed.

To test the degradation of DNA during the sample preparation process, extracted MS751 DNA was treated with DNase C and added to HPV45 and β-actin RPA reactions without reverse transcriptase. As shown in Figure S8B, all extracted MS751 total DNA between 20 and 0.1 ng/µL was successfully degraded by DNase C; neither the HPV45 nor β-actin RPA assays amplified without reverse transcriptase. This indicates that DNase C successfully degraded both HPV and human DNA across the investigated range of concentrations.

As shown in Figure S9, the HPV45 and β-actin RT-RPA assays successfully amplified from DNase-treated cell lysate between concentrations of 4e4 and 4e6 MS751 cells/mL, indicating that both targets can be detected from whole cell lysate with the DNase C sample preparation method across a clinically-relevant range of concentrations45. Additionally, the HPV45 assay without reverse transcriptase did not amplify between concentrations of 4e3 and 4e6 MS751 cells/mL, indicating that HPV DNA can be fully degraded from whole cell lysate with the DNase C sample preparation method across a clinically-relevant range of concentrations.

To demonstrate the feasibility of the sample prep method in degrading both integrated and episomal viral DNA, SiHa cells, which contain integrated linear HPV16 DNA, were spiked with HPV16 full genome plasmids. Additionally, 0.5% polyvinylsulfonic acid (PVSA) was added to the solution for improved RNA preservation during sample collection. Figure S10 shows the results of the HPV16 and β-actin RT-RPA assays with and without reverse transcriptase with 1e5, 1e6, and 1e7 SiHa cells/mL in 0.5% PVSA spiked with HPV16 full genome plasmid and treated with DNase C. HPV16 and β-actin mRNA both successfully amplified in their respective RT-RPA assays, indicating preservation of both human and viral RNA. Additionally, neither the RPA assays for HPV16 nor β-actin amplified, indicating that both integrated viral, circular viral, and human cellular DNA were successfully degraded.

Efficacy of sample preparation method with clinical samples spiked with fresh HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45-positive cultured cells

As shown in Fig. 4A, HPV16 and β-actin mRNA were successfully detected in three different HPV-negative cervicovaginal samples spiked with SiHa cells. No HPV16 DNA amplified, and only one β-actin DNA sample amplified, which does not change the results of the test. As shown in Fig. 4B, HPV18 and β-actin mRNA were successfully detected in all three HPV-negative cervicovaginal samples spiked with HeLa cells. No HPV18 or β-actin DNA amplified. As shown in Fig. 4C, HPV45 and β-actin mRNA were successfully detected in three different HPV-negative cervicovaginal samples spiked with MS751 cells. No HPV45 or β-actin DNA amplified. Together, these results indicate that the sample preparation method is effective with HPV-positive cells in various patient cervicovaginal sample matrices.

HPV-negative clinical samples spiked with HPV-positive cells. (A) Time to positivity of HPV16 and β-actin RT-RPA assays with (+ RT) and without (-RT) reverse transcriptase for three different HPV-negative cervicovaginal samples spiked with SiHa cells. N = 1. (B) Time to positivity of HPV18 and β-actin RT-RPA assays with (+ RT) and without (-RT) reverse transcriptase for three different HPV-negative cervicovaginal samples spiked with HeLa cells. N = 1. (C) Time to positivity of HPV45 and β-actin RT-RPA assays with (+ RT) and without (-RT) reverse transcriptase for three different HPV-negative cervicovaginal samples spiked with MS751 cells. N = 1.

Pilot testing at the point of care with patient samples

To validate sample-to-answer performance of the assay in clinical samples, 11 cervicovaginal samples were collected from patients referred for colposcopy following a positive cervical cancer screening test or as surveillance following cervical cancer preventative treatment. Cervicovaginal samples were provider-collected into 0.5% PVSA in DEPC water and tested at the clinic using the sample-to-answer mRNA detection methods described previously. As shown in Fig. 5, the eight HPV16/18/45-negative samples were valid with β-actin RT-RPA amplification. Additionally, no assays amplified without reverse transcriptase. All of these samples were confirmed as HPV16, 18, and 45 mRNA negative with RT-qPCR, as shown in Fig. 5.

Two samples, 89 and 104, were positive for HPV16 mRNA by both RT-RPA and RT-qPCR. All assays without reverse transcriptase were negative, highlighting specific mRNA detection. For sample 89, the β-actin RT-RPA reaction did not amplify for this sample, but the test is considered valid due to detection of HPV16 mRNA. The β-actin RT-RPA reaction did amplify for sample 104.

Of note, sample 73 was positive for HPV45 DNA, sample 81 was positive for HPV16 DNA, and sample 88 was positive for HPV16, HPV45, and other hrHPV DNA. None of these samples were mRNA-positive by RT-qPCR, highlighting that these RT-RPA assays are highly mRNA-specific. Figure S11 shows the PCR Cq values for all five HPV DNA-positive results, suggesting efficacy across samples with infections of varying viral loads.

Cervicovaginal samples tested at the point of care and with an RT-qPCR gold standard. Top: Cervicovaginal samples collected directly into 0.5% PVSA and tested onsite with the HPV16, HPV18, HPV45, and β-actin RT-RPA assays with (+ RT) and without (-RT) reverse transcriptase. N = 1. Bottom: Cervicovaginal samples collected into PreservCyt media with RNA extracted and tested on RT-qPCR for HPV16, HPV18, HPV45, and β-actin mRNA.

Pathology results from tissue specimens collected via biopsy, endocervical curettage (ECC), or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) on the same day as cervicovaginal swab collection are shown in Table S4. For four out of five HPV mRNA-negative samples, pathology was benign/normal or CIN1 (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1), indicative of a benign HPV infection that led to a positive screening result and colposcopy referral. One HPV mRNA-negative sample, sample 74, had CIN2, an equivocal diagnosis of high-grade cervical abnormalities; however, this sample was negative for HPV16 and HPV18/45 DNA on the commercially-available GeneXpert assay, but positive for one of the pooled other hrHPV types (data not shown), suggesting that if hrHPV mRNA was present from this high-grade lesion, it would likely be one of the hrHPV types not detected by this test. Sample 89 only had a vulvar biopsy taken that was diagnosed as vulvar precancer i.e., VIN2/3 (vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2/3).

Discussion

The RT-RPA assays integrated with extraction-free sample preparation described here present significant advances toward making hrHPV mRNA testing more accessible in resource-limited settings. We demonstrated novel RT-RPA reactions capable of isothermally amplifying HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 mRNA. These reactions are target-specific and as sensitive as the only FDA-approved hrHPV mRNA test with extracted mRNA. We also integrated these novel assays with a minimally instrumented, extraction-free sample preparation method capable of lysing cells and degrading cellular DNA for RNA-specific amplification and validated its sensitivity and specificity with cultured cervical cells.

There are several key strengths to this assay that make it a promising candidate for future deployment in resource-limited settings. First, the RT-RPA assays are not only highly sensitive and specific, but rapid, producing results for extracted RNA in less than 15 min and from crude clinical samples in less than 20 min. Importantly, the addition of the β-actin assay provides a cellular control that could differentiate true negatives from false negative results due to insufficient cellularity. Because the assays are isothermal, they only require a simple benchtop heater/fluorimeter, which costs much less than conventional fluorescence-reading thermocyclers, take up less bench space, and are substantially easier to service and troubleshoot. Second, the novel extraction-free sample preparation method is a major advance for NAATs designed to detect RNA, given its ability to both lyse cells and degrade cellular DNA using minimal equipment compared to other RNA sample preparation methods, such as column purification or magnetic bead isolation. Notably, the three-hour process used to extract RNA for the assay quantification experiments required nineteen separate steps, ten total reagents, three purification columns, a high-speed centrifuge, a heat block, and precise-volume micropipettes. The extraction-free process described here requires only three sample preparation steps (add sample to DNase reaction mix, incubate at 37 °C, inactivate DNase with stop solution), two total reagents, only a small, battery-powered heat block, and could be done with disposable exact-volume pipettes. This is a significant reduction in the amount of resources, equipment, and time required to produce a sample containing RNA that is compatible with RT-RPA amplification.

There are notable improvements that must be made before the test is deployable in resource-limited settings. First, HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 together account for only about 75% of cervical cancer cases; there are 9 or so other high-risk types that cause most of the remainingcervical cancer but with varying oncogenicity and prevalence in different populations worldwide8,46,47. A more clinically significant hrHPV mRNA test that detects up to 5 additional high-risk types (specifically types 31, 33, 35, 52, and 58 that account for an additional ~ 15% of cervical cancer48. would further improve specificity and sensitivity compared to hrHPV DNA detection. Second, the test was evaluated with mostly liquid reagents, many of which are not thermostable, making transportation, storage, and use in resource-limited settings significantly more challenging. Lyophilizing these reagents for thermostability during transportation and storage would greatly facilitate deployment in resource-limited settings, and has been shown to be feasible in previous work49. Likewise, while this test relies on less costly materials than commercially available mRNA NAATs, the cost of the benchtop fluorimeter and reagents could still be prohibitively expensive for many environments. Cost could be reduced by multiplexing the reactions, using an in-house RPA reaction instead of purchasing premade reactions, reducing reaction volume, and replacing the commercially-available benchtop fluorimeter with an open-source fluorimeter like the one described by Coole and colleagues50. Notably, while the most important metrics in the R² deployment of this test are limit of detection and time to amplification, there are differences in the efficiencies and values of the assays; improvement of these through further assay optimization could make this a semi-quantitative test. Finally, the assay must be evaluated and optimized with a larger number of patient cervical samples, including samples that are positive for all three HPV types described here. The data shown in Fig. 4, however, suggest that the assay will be effective with HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 mRNA-positive patient samples. For these cervical cancer cell-spiked HPV-negative samples, target and control RNA were detected and target and control DNA were degraded in three unique cervicovaginal samples, suggesting that the sample-to-answer assay is effective with biologically diverse sample matrices. Future work will include expanding the test to include additional hrHPV types, further validating the integrated RT-RPA assays with extraction-free sample preparation using clinical samples, multiplexing the reactions from four single reactions to two dual reactions to reduce cost, lyophilizing reagents for thermostable transportation and storage, and further simplifying the sample preparation procedure for improved feasibility in resource-limited settings.

The assay described here makes several key advances to the existing literature in the field of point-of-care hrHPV diagnostic tests. To the knowledge of the authors, it is the first demonstration of an hrHPV mRNA testing method with integrated sample preparation in the literature. Many point-of-care tests have been developed for hrHPV DNA, several of which are capable of detecting additional hrHPV genotypes beyond HPV16, 18, and 45 alone, but none have been described for hrHPV mRNA44,51,52,53,54,55. The integrated extraction-free sample preparation method is also a significant step forward in terms of making hrHPV mRNA testing more feasible in resource-limited settings. Other authors have incorporated extraction-free hrHPV DNA sample preparation in both tube and paper membrane-based formats, but none that are capable of preparing crude cellular samples for hrHPV mRNA-specific amplification49,56. Several authors have described extraction-free RNA sample preparation for RNA virus targets such as influenza, HIV-1, and COVID-19, but none have been validated for their effectiveness in isolating viral RNA from a DNA virus38,39,57,58,59,60,61. The methods described here could be used in a variety of applications where it is necessary to measure gene expression with limited resources.

In summary, we have described significant steps toward a sample-to-answer protype HPV mRNA test that could be more easily deployed in resource-limited settings than existing technologies. We designed and characterized RT-RPA assays capable of amplifying HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 mRNA in less than 15 min with a sensitivity and specificity comparable to the current gold standard test, and a β-actin control assay to confirm cellularity in future clinical sample testing. We also developed a novel, extraction-free sample preparation method capable of lysing whole cells and degrading cellular DNA for exclusive mRNA amplification using only one enzyme and a heat block. The minimal instrumentation requirements and few user steps relative to gold standard methods are important advances in improving the accessibility of more specific early cervical cancer detection.

Methods

Generation of mRNA standards

HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 RNA was purified from approximately 1 million SiHa (ATCC HTB-35), HeLa (ATCC CCL-2), and MS751 (ATCC HTB-34) cells, respectively, using the Monarch Total RNA MiniPrep Kit (New England Biolabs), a column-based RNA extraction kit. Ten µL RNA aliquots were stored at −80 °C for future use. Prior to use, each aliquot was treated with RNase-free DNase I in DNase I reaction buffer (New England Biolabs) at 37 °C for 45 min to remove any residual DNA. After DNase I treatment, the Monarch RNA Cleanup Kit (New England Biolabs) was used to remove enzymatic activity. After final elution into DEPC-treated water, EDTA (New England Biolabs) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. Five µL single-use aliquots of DNase I-treated RNA were stored at −80 °C.

To quantify the E7 mRNA, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was used assuming 100% reverse transcription efficiency. Each 20 µL reaction consisted of 10 µL 2X Power SYBR Green RT-PCR Mix (RNA-to-CT 1-step, Applied Biosystems), 0.16 µL RT Enzyme Mix, 1 µL each 10 µM forward and reverse primers (see Table S1), 2.84 µL DEPC water, and 5 µL RNA template. The RT-qPCR protocol was run on a thermocycler (BioRad) and started with incubation at 48 °C for 30 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturing at 95 °C for 15 s and annealing/extending at 60 °C for 1 min, and ending with a melt curve between 60 °C and 95 °C. RT-qPCR standards were prepared from E7 gene gBlocks (Integrated DNA Technologies) quantified with purchased standards (ATCC VR-3240SD for HPV16 and VR-3241SD for HPV18; NIBSC 19/226 for HPV45). E7 gBlocks were used for E7 mRNA quantification instead of quantitative standards for mRNA quantification as they include only the E7 gene sequence and not the entire full-length genome of the quantitative standards. This process was repeated every two months to avoid RNA degradation during storage. Primers used for quantification of both gBlocks and mRNA standards are listed in Table S1.

RT-RPA exo reaction design and optimization

One-step, singleplex HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 RT-RPA exo reactions (TwistDx) were designed and optimized to reliably and specifically detect E7 mRNA in 50 µL reactions. E7 mRNA was selected for this assay because it is translated into the E7 oncoprotein, a key part of the cervical cancer progression pathway, and because unlike E6, its gene does not contain any introns, so alternate splicing is not a concern40. A sensitivity benchmark of 100 mRNA copies per reaction (10 copies per µL) or fewer was selected based on the sensitivity of the Aptima HPV mRNA test. For ease of use in resource-limited settings, one-pot RT-RPA reactions were designed in which reverse transcriptase (RT) was added to an RPA exo assay and a brief pre-reaction incubation was added to the beginning of the assay to give the RT time to generate cDNA.

Primers and a probe (see Table S1) previously designed for an HPV18 RPA exo reaction were screened with two different RTs: Omniscript (Qiagen) and SuperScript IV (Thermo Fisher)42,44. Each reaction consisted of 29.5 µL rehydration buffer, 2.1 µL each of 10 µM forward and reverse primers, 0.6 µL of 10 µM probe, 0.5 µL of 4 URT, 1.5 µL of 10 mM dNTPs (New England Biolabs), 1.2 µL of DEPC-treated water, 2.5 µL of 280 µM magnesium acetate, and 10 µL of target added to a lyophilized RPA exo reaction pellet. A 2 mm magnetic stainless steel mixing ball (Simply Bearings) previously washed with SDS, nuclease-free water, and ethanol was also added to each reaction. The mixing ball is critical for sensitive amplification due to the high viscosity of the RPA reaction. The reactions were incubated at 39 °C on a T8-ISO instrument (Axxin Pty Ltd.) which was programmed to measure fluorescence in the FAM (fluorescein) channel every 20 s for 30 min with mixing throughout the reaction. One thousand RFU was defined as the positivity threshold, and the time at which fluorescence in the well exceeded 1,000 RFU was defined as the time to positivity. One well of one of the T8s had a consistently high baseline fluorescence value of approximately 500 RFU above the rest of the wells, so for that well, the RFU positivity threshold was adjusted to 1500 instead of 1000.

Reactions with each RT and 100 copies per reaction of HPV18 mRNA were performed including a pre-reaction step in which the reaction tubes were heated at 39 °C without mixing for a duration of 1 to 10 min before fluorescence measurements were recorded.

Next, an HPV16 RT-RPA exo reaction was designed to detect HPV16 E7 mRNA. Primers and probes for the HPV16 RT-RPA reaction are listed in Table S1. This reaction consisted of 29.5 µL rehydration buffer, 0.6 µL each of 50 µM forward and reverse primers, 1 µL of 10 µM probe, 0.5 µL of 4 URT, 2 µL of 10 mM dNTPs, 3.3 µL of DEPC-treated water, 2.5 µL of 280 µM magnesium acetate, and 10 µL of target added to a lyophilized RPA exo reaction pellet. Of note, the primer, probe, and dNTP concentrations are higher than the concentrations used in the HPV18 reaction. A stainless-steel magnetic mixing ball was also added to these reactions.

An HPV45 assay was designed using the same reagent concentrations as used for HPV18. Primers and probes for the HPV45 RT-RPA exo reaction are listed in Table S1.

Optimal reaction conditions were selected based on which reagents, concentrations, and reaction times resulted in consistent amplification of 100 copies of mRNA or fewer and no nonspecific amplification of no-target controls and no-RT controls. Once the reaction conditions were selected and the assays were optimized, the exo reactions for HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 were run with mRNA between 10 and 10,000 copies per reaction in triplicate to determine the limit of detection and assess whether there was a relationship between input copies and time to amplification. For each HPV type, control reactions without RT were also run in triplicate with 10,000 mRNA copies to confirm a lack of nonspecific amplification.

Finally, a cellular control RT-RPA assay was designed to detect β-actin mRNA using primers and a probe designed by Li and colleagues (Table S1)62. The cellular control is essential to confirm that a negative result genuinely indicates the absence of hrHPV mRNA, and not that insufficient cellular material is present.

Reaction components, concentrations, and volumes for all four RT-RPA assays used in this manuscript are listed in Table S2.

Assay specificity analysis using off-target HPV types

gBlocks of the E7 gene (Integrated DNA Technologies) for 12 off-target high- and low-risk HPV types (6, 11, 31, 33, 35, 39, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68) were reconstituted in 1X TE buffer to a final concentration of 10 ng/µL, and then quantified by using a NanoDrop UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) to calculate the copy number per µL. Each gBlock, including gBlocks for HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45, was then diluted in nuclease-free water to 100,000 copies per µL (1 million copies per reaction) and tested separately in the RT-RPA reactions for HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45.

Osmotic shock lysis validation

1 mL of SiHa cells were freshly harvested in 1X PBS. Three separate 10 µL aliquots of these cells were counted. Then, the cells were centrifuged at 5000 x g for 10 min. The PBS supernatant was removed and the cell pellet was resuspended in 970 µL DEPC-treated water to induce osmotic shock and lyse the cells. After a 10-minute incubation at room temperature, three 10 µL aliquots were again counted. The difference in means between the cell counts before and after osmotic shock lysis were compared to determine the lysis efficacy of this method.

Screen of DNases for efficacy of degrading cellular DNA from a cervicovaginal swab

A provider-collected cervicovaginal swab was collected directly into DEPC-treated water. 10 µL of this sample was added to nine separate reactions with different DNases. The nine DNases and their reaction conditions are listed in Table S3. Following treatment with each of the DNases, 10 µL of the crude DNase-treated sample was added to two replicates of a β-actin RPA reaction without reverse transcriptase to test whether all the DNA had been degraded.

DNase C limit of RNA detection and efficacy of DNA degradation with nucleic acid in solution

Extracted HPV45 total RNA was diluted to 1,000, 100, 10, and 1 copy per µL in DEPC-treated water. Each RNA dilution was treated with the DNase C conditions as listed in Table S3. After the addition of the stop solution, each RNA dilution was split in half, with one aliquot heat deactivated and the other aliquot placed directly on ice with no heat deactivation. Each RNA dilution, with and without heat deactivation, was added to the HPV45 RT-RPA assay.

Extracted HPV45 total RNA was diluted to 10, 10, 1, and 0.1 ng/µL and each dilution was treated with the DNase C conditions described in Table S3, but without heat deactivation. Following DNase C treatment, each dilution was added to an HPV45 RPA assay (without reverse transcriptase).

DNase C limit of mRNA detection and efficacy of DNA degradation in whole cell lysate

MS751 cells were freshly harvested into DEPC-treated water and diluted to 4 million cells/mL, 400,000 cells/mL, 40,000 cells/mL, and 4,000 cells/mL and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were treated with DNase C with stop solution and no heat deactivation and added to HPV45 and β-actin RT-RPA reactions with and without reverse transcriptase.

DNase C limit of mRNA detection and efficacy of DNA degradation in whole cell lysate spiked with plasmid DNA to demonstrate maintained efficacy with different types of DNA

SiHa cells were freshly harvested and resuspended in DEPC water with 0.5% PVSA added for improved RNA stability at concentrations of 10,000,000, 1,000,000, and 100,000 cells/mL63. HPV16 full genome plasmids were added to each cell lysate at the same concentration of copies/mL as cells/mL, for a 1:1 ratio of linear : circular viral DNA. The samples were then treated with DNase C as described previously. Following DNase C treatment, each sample was added to RT-RPA reactions for HPV16 and β-actin with and without reverse transcriptase.

Efficacy of sample preparation method with HPV-negative samples spiked with fresh HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45-positive cultured cells

Three aliquots each of 10 million SiHa, HeLa, and MS751 cells/mL were harvested and resuspended in 1 mL 0.5% PVSA in DEPC-treated water for immediate lysis. 10 µL of each cell lysate was added to 90 µL of a confirmed hrHPV DNA and mRNA-negative cervicovaginal samples for a concentration of approximately 1 million HPV-positive cells/mL. Each cell type was added to three samples from three different patients. Each of the nine samples was treated with DNase C treated with stop solution only following incubation. After the addition of stop solution, each sample was added to RT-RPA reactions with and without reverse transcriptase of the HPV-type associated with the cell line added and β-actin with and without reverse transcriptase.

Pilot testing of patient cervicovaginal samples at the point of care

Cervicovaginal samples were collected from patients referred for colposcopy at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Women were eligible to participate if they (1) had a cervix, (2) were 21 years of age or older, (3) were scheduled to undergo hrHPV testing according to national or institutional guidelines at time of enrollment and/or were scheduled to undergo biopsy, loop electrosurgical excision procedures (LEEPs), and/or or endocervical curettage (ECC), (4) were willing and able to provide written informed consent, (5) were able to perform protocol-required activities, and (6) were able to speak and read English or Spanish. Participants provided written informed consent, and the protocol was reviewed and approved by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Rice University IRB. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations.

RT-RPA reaction mixes for HPV16, HPV18, HPV45, and β-actin with and without reverse transcriptase and the DNase C reaction mix without stop solution were prepared in the lab the morning before testing and added to a small cooler with ice packs. The RT-RPA reactions were prepared separately from the RPA exo enzyme pellets and magnesium acetate. All equipment and reagents necessary for testing were transported to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center colposcopy clinic. Patients who consented to the study had a cervicovaginal sample provider-collected directly into 350 µL 0.5% PVSA in DEPC-treated water, which was immediately added to the prepared DNase C reaction. Following incubation, stop solution was added to the reaction and the treated sample lysate was added directly to the eight pre-prepared reaction mixes mixed with the RPA exo enzyme pellets. Magnesium acetate was added to the caps of the tube strips, the caps were placed on the tubes, the tubes were briefly centrifuged on a miniature centrifuge and placed on the Axxin T8.

For gold standard results, RNA was extracted from a 50 µL aliquot of each sample using the Monarch kit as described previously, and each sample was tested for amplification with the RT-qPCR assays for HPV16, HPV18, HPV45, and β-actin. A no-RT control, no-target control and HPV-type specific RNA positive control were included for all the HPV assays. A no-RT control and HPV18 RNA positive control were included for the β-actin assay.

Results of the RT-RPA assay were compared to the gold standard of RT-qPCR with extracted RNA. RT-RPA results were also compared to pathology results from biopsy, endocervical curettage (ECC), and/or loop electrosurgical excision (LEEP) specimens collected at the time of study enrollment, when available.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Files).

References

Hu, Z. & Ma, D. The precision prevention and therapy of HPV-related cervical cancer: new concepts and clinical implications. Cancer Med. 7, 5217–5236 (2018).

Landy, R., Pesola, F., Castañón, A. & Sasieni, P. Impact of cervical screening on cervical cancer mortality: Estimation using stage-specific results from a nested case–control study. Br. J. Cancer. 115, 1140–1146 (2016).

Petersen, Z. et al. Barriers to uptake of cervical cancer screening services in low-and-middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Womens Health. 22, 486 (2022).

De Vuyst, H. et al. The burden of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa. Vaccine 31, F32–F46 (2013).

Unger-Saldaña, K., Alvarez-Meneses, A. & Isla-Ortiz, D. Symptomatic presentation, diagnostic delays and advanced stage among cervical cancer patients in Mexico. J. Glob Oncol. 4, 221s–221s (2018).

Cervical cancer - Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cervical-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20352501

Hull, R. et al. Cervical cancer in low and middle-income countries. Oncol. Lett. 20, 2058–2074 (2020).

HPV and Cancer - NCI. (2019). https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer

Li, N., Franceschi, S., Howell-Jones, R., Snijders, P. J. F. & Clifford, G. M. Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30,848 invasive cervical cancers worldwide: variation by geographical region, histological type and year of publication. Int. J. Cancer. 128, 927–935 (2011).

Moscicki, A. B. et al. Regression of low-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesions in young women. Lancet 364, 1678–1683 (2004).

Campos, N. G. et al. An updated natural history model of cervical cancer: derivation of model parameters. Am. J. Epidemiol. 180, 545–555 (2014).

WHO guideline for screening. and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention, second edition. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240040434

Catarino, R., Petignat, P., Dongui, G. & Vassilakos, P. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries at a crossroad: emerging technologies and policy choices. World J. Clin. Oncol. 6, 281–290 (2015).

Ronco, G. et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 11, 249–257 (2010).

Derbie, A., Mekonnen, D., Woldeamanuel, Y., Van Ostade, X. & Abebe, T. HPV E6/E7 mRNA test for the detection of high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2+): a systematic review. Infect. Agent Cancer. 15, 9 (2020).

Pal, A. & Kundu, R. Human papillomavirus E6 and E7: the cervical cancer hallmarks and targets for therapy. Front Microbiol 10, 3116 (2020).

Gradíssimo, A. & Burk, R. D. Molecular tests potentially improving HPV screening and genotyping for cervical cancer prevention. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 17, 379–391 (2017).

Arbyn, M. et al. The APTIMA HPV assay versus the hybrid capture 2 test in triage of women with ASC-US or LSIL cervical cytology: a meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy. Int. J. Cancer. 132, 101–108 (2013).

Castle, P. E. et al. A Cross-sectional study of a prototype carcinogenic human papillomavirus E6/E7 messenger RNA assay for detection of cervical precancer and cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 2599–2605 (2007).

Cuschieri, K. S., Beattie, G., Hassan, S., Robertson, K. & Cubie, H. Assessment of human papillomavirus mRNA detection over time in cervical specimens collected in liquid based cytology medium. J. Virol. Methods. 124, 211–215 (2005).

Graham, S. Human papillomavirus: gene expression, regulation and prospects for novel diagnostic methods and antiviral therapies. Future Microbiol. 5, 1493–1506 (2010).

Al-Shibli, K. et al. Impact of HPV mRNA types 16, 18, 45 detection on the risk of CIN3 + in young women with normal cervical cytology. PLOS ONE. 17, e0275858 (2022).

Arbyn, M. et al. Accuracy and effectiveness of HPV mRNA testing in cervical cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 23, 950–960 (2022).

Haedicke, J. & Iftner, T. A review of the clinical performance of the Aptima HPV assay. J. Clin. Virol. 76, S40–S48 (2016).

Castle, P. E. et al. Detection of human papillomavirus 16, 18, and 45 in women with ASC-US cytology and the risk of cervical precancer: results from the CLEAR HPV study. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 143, 160–167 (2015).

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) to screen for cervical Pre-Cancer lesions and prevent cervical cancer: policy brief. World Health Organization (2022). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045248

Ting, J., Smith, J. S. & Myers, E. R. Cost-Effectiveness of High-Risk human papillomavirus testing with messenger RNA versus DNA under united States guidelines for cervical cancer screening. J. Low Genit. Tract. Dis. 19, 333 (2015).

Cayon, A. & PAHO/WHO | HPV Tests For Cervical Cancer Screening. Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization (2016). https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=11925:hpv-tests-for-cervical-cancer-screening&Itemid=41948&showall=1&lang=en

MISC-06024-001 Rev. 001 FAQ: All-Inclusive Testing Price Agreement for Hologic Panther® System. (2019).

PreTect HPV-Proofer. PreTect AS (2023) https://www.pretect.no/pretecthpvprooferorg

Ratnam, S. et al. Clinical performance of the pretect HPV-Proofer E6/E7 mRNA assay in comparison with that of the hybrid capture 2 test for identification of women at risk of cervical cancer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 2779–2785 (2010).

QuantiVirus™ & HPV E6/E7 mRNA. Test for Cervical Cancer | DiaCarta, Inc. https://www.diacarta.com/products/hpv-cervical-cancer

Macedo, A. C. L. et al. Accuracy of mRNA HPV Tests for Triage of Precursor Lesions and Cervical Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Oncol. 6935030 (2019). (2019).

Kundrod, K. A. et al. Advances in technologies for cervical cancer detection in low-resource settings. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 19, 695–714 (2019).

Thatcher, S. A. DNA/RNA Preparation for molecular detection. Clin. Chem. 61, 89–99 (2015).

Afolabi, O. I. Ribonucleic acid extraction: A mini-review of standard methods. Afr. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 25, 1–5 (2024).

Monarch Total, R. N. A. & Miniprep Kit (NEB #T2010) | NEB. https://www.neb.com/en-us/products/t2010-monarch-total-rna-miniprep-kit

Kundrod, K. A. et al. Sample-to-answer, extraction-free, real-time RT-LAMP test for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal, nasal, and saliva samples: implications and use for surveillance testing. PLOS ONE. 17, e0264130 (2022).

Deng, H. et al. An ultra-portable, self-contained point-of-care nucleic acid amplification test for diagnosis of active COVID-19 infection. Sci. Rep. 11, 15176 (2021).

Van Doorslaer, K. et al. The papillomavirus episteme: a major update to the papillomavirus sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D499–D506 (2017).

Kundrod, K. A. Point-of-Care Tests To Amplify and Detect High-Risk HPV DNA and mRNA. ProQuest (Rice University, 2020).

Izadi, N., Strmiskova, J., Anton, M., Hausnerova, J. & Bartosik, M. LAMP-based electrochemical platform for monitoring HPV genome integration at the mRNA level associated with higher risk of cervical cancer progression. J. Med. Virol. 96, e70008 (2024).

Kundrod, K. A. et al. An integrated isothermal nucleic acid amplification test to detect HPV16 and HPV18 DNA in resource-limited settings. Sci. Transl Med. 15, eabn4768 (2023).

Aranda Flores, C. E., Gutierrez, G., Ortiz Leon, G., Cruz Rodriguez, J. M., Sørbye, S. W. & D. & Self-collected versus clinician-collected cervical samples for the detection of HPV infections by 14-type DNA and 7-type mRNA tests. BMC Infect. Dis. 21, 504 (2021).

Pinkbook | HPV | Epidemiology of Vaccine Preventable Diseases | CDC. (2022). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/hpv.html

Bruni, L. et al. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: Meta-Analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J. Infect. Dis. 202, 1789–1799 (2010).

Johnson, L. G. et al. Selecting human papillomavirus genotypes to optimize the performance of screening tests among South African women. Cancer Med. 9, 6813–6824 (2020).

Smith, C. A. et al. A low-cost, paper-based hybrid capture assay to detect high-risk HPV DNA for cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings. Lab. Chip. 23, 451–465 (2023).

Coole, J. et al. Open-Source miniature fluorimeter to monitor Real-Time isothermal nucleic acid amplification reactions in Resource-Limited settings. JoVE J. Vis. Exp. e62148 https://doi.org/10.3791/62148 (2021).

Zamani, M. et al. Electrochemical strategy for low-cost viral detection. ACS Cent. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.1c00186 (2021).

Seely, S. et al. Point-of-Care molecular test for the detection of 14 High-Risk genotypes of human papillomavirus in a single tube. Anal. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.3c01723 (2023).

Chang, M. M. et al. A novel tailed primer nucleic acid test for detection of HPV 16, 18 and 45 DNA at the point of care. Sci. Rep. 13, 20397 (2023).

Kreutz, E. Self-digitization chip for quantitative detection of human papillomavirus gene using digital LAMP. Lab. Chip. 19, 1035–1040 (2019).

Barra, M. et al. Single-tube four-target lateral flow assay detects human papillomavirus types associated with majority of cervical cancers. Anal. Biochem. 688, 115480 (2024).

Rodriguez, N. M., Wong, W. S., Liu, L., Dewar, R. & Klapperich, C. M. A fully integrated paperfluidic molecular diagnostic chip for the extraction, amplification, and detection of nucleic acids from clinical samples. Lab. Chip. 16, 753–763 (2016).

Rodriguez, N. M. et al. Paper-Based RNA extraction, in situ isothermal amplification, and lateral flow detection for Low-Cost, rapid diagnosis of influenza A (H1N1) from clinical specimens. Anal. Chem. 87, 7872–7879 (2015).

Burgard, M. et al. Performance of HIV-1 DNA or HIV-1 RNA tests for early diagnosis of perinatal HIV-1 infection during Anti-Retroviral prophylaxis. J. Pediatr. 160, 60–66e1 (2012).

Drain, P. K. et al. Point-of-Care HIV viral load testing: an essential tool for a sustainable global HIV/AIDS response. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32 https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00097 (2019).

Deraney, R. N. et al. Vortex- and Centrifugation-Free extraction of HIV-1 RNA. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 23, 419–427 (2019).

Phillips, A. Microfluidic rapid and autonomous analytical device (microRAAD) to detect HIV from whole blood samples. Lab. Chip. 19, 3375–3386 (2019).

Li, R. et al. Centrifugal microfluidic-based multiplex recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. iScience 26, 106245 (2023).

Earl, C. C., Smith, M. T., Lease, R. A. & Bundy, B. C. Polyvinylsulfonic acid: A Low-cost RNase inhibitor for enhanced RNA preservation and cell-free protein translation. Bioengineered 9, 90–97 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: E.N.N., K.A.K., J.R.M., M.E.S., P.E.C., R.R.K,. Methodology: E.N.N., A.M., K.A.K., M.M.C., C.J.H. Validation: E.N.N., A.M. Formal analysis: E.N.N. Investigation: E.N.N, A.M., C.J.H. Resources: R.R.K., M.G., M.P.S., K.S. Writing – Original Draft: E.N.N., R.R.K. Writing - Review & Editing: E.N.N., A.M., K.A.K., M.M.C., C.J.H., J.R.M., M.E.S., M.P.S., K.S., P.E.C., R.R.K. Visualization: E.N.N., R.R.K. Supervision: R.R.K. Funding acquisition: R.R.K., K.A.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Castle has received HPV tests and assays for research at a reduced or no cost from Roche, Becton Dickinson, Cepheid, Arbor Vita Corporation, and Atila Biosystems. Other authors do not have competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Novak, E.N., Ma, A., Kundrod, K.A. et al. Extraction-free RT-RPA assay for detection of HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45 mRNA expression. Sci Rep 15, 30450 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13583-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13583-2