Abstract

Infective endocarditis is an infection of the endocardium, associated with high morbidity and mortality, particularly when the left heart chambers are involved. Timely diagnosis and appropriate intervention can attenuate these outcomes. The objective of this study was to create and validate the EndoPredict-Px score for early in-hospital mortality prediction in patients with left-sided infective endocarditis. This analysis focused on patients admitted to the emergency department with left-sided infective endocarditis defined by the Duke-ISCVID criteria, from January 2011 to January 2020. The main outcome was in-hospital mortality. Among 530 patients with left-sided infective endocarditis, 160 (30.2%) died during hospitalization. The score included age ≥ 60 years, absence of fever, NYHA functional class III or IV heart failure, suspected embolism, hemoglobin level ≤ 10 g/dL, leukocyte level ≥ 12 × 109/L, platelet level ≥ 150 × 109/L, and creatinine level ≥ 1.3 mg/dL. Patients were categorized into three mortality risk groups. The model displayed an AUROC of 0.76 (95% CI 0.71–0.80) and 0.74 in the bootstrap validation. Both the derivation and validation models showed accurate calibration. In conclusion, the EndoPredict-Px score accurately and early predicted in-hospital mortality in patients with left-sided infective endocarditis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infective endocarditis is a severe infection of the endocardium that can affect native or prosthetic heart valves, the endocardial surface, or implanted cardiac devices. It is associated with high morbidity and mortality, particularly when the left heart chambers are involved1,2,3,4,5. The pivotal events that reduced its lethality occurred in the 1940s with the introduction of penicillin, followed by the adoption of surgical valve interventions in the 1960s6. Other notable advancements included diagnostic methods, microbial sensitivity profiling, refined in-hospital care practices, improvements in surgical techniques, expanded antimicrobial options, well-structured guidelines, and the establishment of dedicated endocarditis teams2,7,8.

Despite this remarkable progress, in-hospital mortality rates for infective endocarditis still range from 13 to 26% in high-income countries4,5,9,10 and up to 48% in low- and middle-income countries1,11. Beyond mortality, approximately 40% of individuals with infective endocarditis experience significant complications, such as systemic embolism, heart failure, atrioventricular block, the need for dialysis, and cardiogenic and/or septic shock 3,12,13.

Early clinical or surgical interventions can reduce the likelihood of adverse outcomes11,13. Therefore, identifying individuals who are at a higher risk of mortality can potentially minimize the harm caused by infective endocarditis. Several investigations have focused on identifying the factors that are associated with mortality in patients with infective endocarditis and scoring systems have been created to measure this risk9,14,15,16,17,18. However, all current predictive models depend on blood culture results, cardiac imaging, or the occurrence of in-hospital complications, which limits their immediate adoption. Thus, a simple score using variables easily available in the first hours after admission could be helpful, even in resource-limited settings. The objective of this study was to derive and validate the use of the EndoPredict-Px score for the early prediction of mortality in patients with left-sided infective endocarditis in the emergency department.

Methods

Study design and population

The study was conducted in the emergency department of a tertiary teaching hospital specializing in cardiovascular disease. Patients with left-sided infective endocarditis admitted between January 2011 and January 2020 were selected from a prospectively maintained database. Physicians from the Hospital Infection Control Unit identified and recorded these patients consecutively during weekday visits as part of their surveillance activities.

The inclusion criteria were patients aged 18 years or older classified as having possible or definite left-sided infective endocarditis according to the Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID) for Infective Endocarditis published in 202319. The inclusion of cases classified as “definite” and “possible” was chosen to ensure a broad and representative sample, as both are treated equally in clinical practice. This approach allows for score derivation that reflects the clinical reality, capturing different diagnostic stages of infective endocarditis without compromising the applicability of the results. The study was originally designed to use modified criteria based on the 2015 guidelines7, and it was subsequently adjusted to incorporate the 2023 ISCVID criteria update19. Patients who received intravenous antibiotic therapy in the 72 h prior to inclusion in the study were excluded, as prior antibiotic use could modify the clinical presentation and laboratory results. Patients with right-sided infective endocarditis were purposefully not included in the study due to their different prognosis, which includes a lower incidence of complications such as embolization, hemodynamic impairment, and mortality20,21,22.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality during hospitalization. Participants were followed until discharge or death.

The construction of the scoring system followed the “Guide for presenting clinical prediction models for use in clinical settings”23, and its reporting was based on the “Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis” (TRIPOD) statement24.

Data collection

The data were collected by cardiologists and infectious disease specialists through the evaluation of hospital infection control units and medical records. Patients with uncertain data were discussed by a multidisciplinary team. The included patients were input into the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic system25. Details regarding the data collection are available in Supplementary Table S1 online.

Fever was documented based on the patient’s report or confirmed measurement at the time of suspected infective endocarditis. Suspected embolism was determined by any new neurological deficit, including sudden changes in motor function, sensation, cognition, speech, or vision, or signs of unilateral limb ischemia, such as absence of pulse, pallor, cyanosis, pain, or decreased temperature.

Statistical analysis

In accordance with contemporary best practices, a sample size of 558 cases was required to achieve a margin of error of at most 0.05 around the overall outcome estimate proportion. This ensured a small mean absolute error of less than 10% in predicted probabilities when the model was applied to other individuals and effectively addresses overfitting concerns, considering an outcome proportion of 0.3, 14 parameters, and a Cox-Snell R2 of 0.20.

We stratified the descriptive statistics based on in-hospital mortality and presented them as the means and standard deviations or medians and 25th/75th percentiles for continuous variables, as appropriate for their distribution, and the statistics were presented as counts and percentages for categorical variables. The analysis involved the use of t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables, as appropriate, and the chi-square test for categorical variables.

To facilitate the creation of a clinically applicable score, continuous variables of interest were converted into categorical variables. The cutoff values were based on their nonlinear distribution using restricted cubic splines with 4 knots and established thresholds.

Predictor variables were selected after a thorough review of the literature on infective endocarditis predictors9,10,15,16,17 and in consultation with a team comprising cardiologists, infectious disease specialists, and an intensivist. For multivariable analysis, the selected variables included age ≥ 60 years, hypertension, diabetes, absence of fever, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV heart failure, suspected embolism involving a central nervous system (CNS) deficit and/or limb ischemia, hemoglobin level ≤ 10 g/dL, leukocyte level ≥ 12 × 109/L, creatinine level ≥ 1.3 mg/dL, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level ≥ 100 mg/L. Both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted.

These variables were integrated into an initial model, and a multivariable logistic regression was performed, with a purposeful backward selection of variables to create the final model. Subsequently, we developed a scoring system, assigning points based on the logistic regression beta coefficients for each variable. Finally, to assess the prognostic utility of the model, patients were categorized into three distinct risk levels for developing infective endocarditis by analyzing the numerical and graphical distributions of the risk of this outcome and testing the optimal cutoff point for group differentiation. We present a Kaplan‒Meier survival curve, censored at 30 days, illustrating the survival probabilities across the three risk groups (low, intermediate, and high risk) as defined by the EndoPredict-Px score.

Apparent validation was conducted by analyzing the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC). We additionally evaluated the impact of incorporating echocardiographic variables on the model’s performance. Calibration was assessed using a calibration belt. Bootstrap internal validation was performed with 500 bootstrap resamples for AUROC, calibration-in-the-large, and calibration slope.

We compared the prognostic performance of the EndoPredict-Px score with that of another model, the ACEF score16. We compared AUROCs using DeLong’s method.

Given the low proportion of missing data for the variables selected for model development, we performed a complete case analysis. All tests were 2-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. No adjustment for multiplicity was performed. The analysis was performed using StataSE® software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), version 16.0.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Heart Institute of the University of Sao Paulo Medical School. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, Ethics and Research Committee of the Heart Institute of the University of Sao Paulo Medical School waived the need of obtaining informed consent. No funding was received for this study.

Results

From January 2011 to January 2020, a total of 555 patients with left-sided infective endocarditis involving the left heart chambers were identified. After excluding 25 patients who received intravenous antibiotic therapy for 72 h before inclusion, a total of 530 patients were included in the study. Of these, 436 (82.3%) were categorized as definite infective endocarditis according to the Duke-ISCVID criteria, while 94 (17.7%) were classified as possible cases.

Participant characteristics

The median age of the participants was 56 years (interquartile range 39–73), and 46.6% were 60 years or older. There was a male predominance of 63.6%. Predisposing conditions for infective endocarditis were present in 82.1% of the patients. The most prevalent heart valve disease etiology was rheumatic (35.1%), followed by degenerative (20.6%) and mitral valve prolapse (10.4%). Common comorbidities included hypertension and diabetes mellitus in 52.5% and 18.7%, respectively. Causative infective endocarditis microorganisms were identified in 79.6% of the patients. Mixed infections involving multiple microorganisms were observed in 4.3% of the patients. The baseline clinical characteristics of the participants are described in Table 1, and the admission laboratory test, microorganism, and echocardiographic characteristics are described in Table 2, which also presents missing data.

Outcomes

By the end of hospitalization, 24.5% of participants presented embolic events. The sites of embolism were as follows: central nervous system, 61.5%; spleen, 33.8%; limbs, 19.2%; kidney, 10%; liver, 6.2%; and spine, 2.3%. Cardiac surgery was recommended for 65.3% of patients, for a total surgical rate of 55.7%. The reasons for not undergoing surgery were poor clinical status (94.1%) and patient refusal (5.9%). Among the 90 patients classified as high-risk who underwent surgery, early intervention (within the first 7 days) was not associated with a significant reduction in mortality compared to later surgery (OR 1.2; 95% CI 0.45–3.21; p = 0.72).

The overall in-hospital mortality rate was 30.2%. Mortality was attributed to septic shock in 67.5%, heart failure in 48.7%, surgical complications in 13.1%, embolism-related complications in 8.7%, nosocomial infection in 2.5%, or other causes in 9.4%.

Score derivation and apparent validity

The variables and their respective scores are detailed in Table 3. Logistic regression data for both univariate and multivariate analyses can be found in Supplementary Table S2 online. The probability of all-cause in-hospital death according to the EndoPredict-Px score is illustrated in Supplementary Figure S1 online, with a corresponding histogram in Supplementary Figure S2 online.

Risk groups for in-hospital death were established as follows: low-risk (0–2 points), intermediate-risk (3–6 points), and high-risk (≥ 7 points) based on the calculated EndoPredict-Px score, as shown in Table 4. The observed incidences of in-hospital death were 9.4%, 20.6%, and 52.2% for the three risk groups, respectively.

The EndoPredict-Px score achieved an AUROC of 0.76 (95% CI 0.71–0.80). Adding echocardiographic data indicative of poor prognosis—such as abscess, significant valvular dysfunction, perforation, vegetation larger than 1 cm, fistula, or prosthetic valve dehiscence—did not enhance the model’s performance, as the AUROC remained unchanged at 0.76 (95% CI 0.71–0.80). Model calibration, reflecting the alignment between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes, was appropriate and is illustrated by the calibration belt (Fig. 1). The relationships between the risk groups and survival are depicted in Fig. 2.

Internal validation

Internal validation of the samples was performed by bootstrap resampling with 500 replicates. Discriminative power was assessed using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, which revealed an AUROC of 0.74. Calibration was assessed through a calibration increment of 0.017 and a slope of 0.916.

Comparison with the ACEF score

Applying the ACEF score in our database resulted in an AUROC of 0.64 (95% CI 0.58–0.69). The AUROC of the EndoPredict-Px was more discriminative than ACEF (p < 0.001)—Fig. 3. The calibration belt p value was 0.130, with a narrow range of prediction probabilities and large uncertainty in higher expected probabilities (Supplementary Figure S3 online). Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed no differences between the low- and intermediate-risk groups (Supplementary Figure S4 online).

Discussion

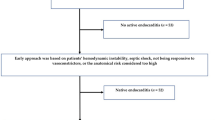

This study presents the EndoPredict-Px score, a newly developed tool for predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with left-sided infective endocarditis, applicable to both surgical and non-surgical cases. While numerous tools have been developed to assess mortality risk, many require blood culture and echocardiography results, as well as time-dependent factors such as persistent bacteremia and nosocomial pneumonia, which are impractical in emergency settings. The novelty of this scoring system lies in its immediate applicability and its exclusive utilization of early clinical and laboratory parameters. Initially, echocardiographic variables were not included to keep the model simple and accessible. When these variables—some requiring transesophageal echocardiography—were later incorporated, they did not improve model performance. This highlights the score’s effectiveness for early risk assessment, even in resource-limited emergency settings. Nonetheless, clinical decisions—particularly regarding referral and treatment—must always consider patients’ comorbidities and surgical eligibility. The potential application of the score is illustrated in Fig. 4.

The EndoPredict-Px variables were selected with a focus on ensuring that the prognostic criteria could mirror the emergency department reality and be universally applied. In this regard, we chose serum creatinine over creatinine clearance for its straightforward application in swift clinical judgments and its ease of standardization. In addressing potential embolisms, we acknowledged concerns about the standardization of this variable but adhered to well-defined criteria (see Methods—Data Collection) that demonstrated a strong association with mortality. We prioritized clinical indicators over imaging to maintain a scoring system that is rapidly deployable and accessible.

In the same line, we also considered both patient reports and hospital measurements as indicators of fever. The absence of fever was significantly correlated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality (Odds Ratio 2.24, p < 0.001). Although the absence of fever has been described as a risk factor for death in other clinical contexts26, to our knowledge, no other study has investigated this specific correlation. The inability to develop fever during infection may indicate immunological frailty in patients with lower physiological reserves. Additionally, other authors have observed that the quality of treatment offered to patients with fever is often superior to that offered to those who do not present with this symptom27,28.

Despite its simplicity, the EndoPredict-Px score has a similar performance compared to other existing models9,16,18,26,31. It achieved an AUROC of 0.76 (95% CI 0.71–0.80) in derivation and 0.74 in validation. For instance, the ICE score was designed to predict the 6-month mortality risk. This score was derived from a cohort of 4049 participants and validated with 1197 participants. Key variables included age, history of dialysis, nosocomial endocarditis, prosthetic valve, symptom onset more than one month after admission (a protective factor), Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus viridans (a protective factor), aortic and mitral vegetation, NYHA class III or IV heart failure, stroke, paravalvular complications, persistent bacteremia, and surgical treatment (a protective factor). The AUROC was 0.715 in the derivation cohort and 0.682 in the validation cohort9. Another example is the SHARPEN score, which includes systolic blood pressure, heart failure, age, renal function, pneumonia, elevated peak CRP, and non-intravenous drug abusers, aimed at estimating in-hospital mortality risk18. The SHARPEN score showed an AUROC of 0.86 (95% CI 0.80–0.91) in the derivation cohort and 0.76 (95% CI 0.67–0.85) in a Brazilian validation cohort18,30. Similarly, the ENDOVAL score31 incorporates variables such as age, prosthetic valve endocarditis, comorbidities, heart failure, renal failure, septic shock, Staphylococcus aureus or fungal infection, periannular complications, ventricular dysfunction, and vegetation. This score demonstrated strong performance in both the derivation (AUROC of 0.823, 95% CI 0.774–0.873) and the validation cohort (AUROC of 0.753, 95% CI 0.659–0.847).

A recently published model, the ASSESS-IE score32, was also developed to predict in-hospital mortality in patients with infective endocarditis and demonstrated good discrimination in both derivation and validation cohorts (AUROC 0.781 and 0.779, respectively). It incorporates six early variables: NYHA functional class III-IV, prosthetic valve, aortic valve involvement, hemoglobin < 90 g/L, direct bilirubin > 0.4 mg/dL, and acute clinical course (< 1 month). Although promising in its simplicity and performance, one limitation to its immediate applicability lies in the identification of aortic valve involvement, which may require transesophageal echocardiography—a diagnostic modality not universally available in emergency settings. Even when performed, the exam may fail to detect valve involvement despite confirmed endocarditis, as observed in our own series.

In response to the need for a mortality risk assessment, the ACEF (Age, Creatinine, Ejection Fraction) score was developed16. It is calculated using the following formula: age/left ventricular ejection fraction (%) + 1 point for creatinine > 2 mg/dL. The ACEF score categorizes mortality risk as low for scores < 0.6 (4.2% mortality), intermediate for 0.6–0.8 (5% mortality), and high for > 0.8 (14.4% mortality), with an AUROC of 0.706 (95% CI 0.651–0.763). In our cohort, the application of the ACEF score had an AUROC of 0.64 (95% CI 0.58–0.69). Although both scores are based on early admission variables, EndoPredict-Px demonstrated higher discriminative ability in our population (p < 0.001). The nomogram displayed a limited range of prediction probabilities and failed to effectively discriminate between the low- and intermediate-risk groups, as evidenced by Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Supplementary Figure S4 online). In an exploratory analysis, no significant mortality benefit was observed with early surgery among high-risk patients, although this finding should be interpreted with caution due to the unadjusted analysis and limited sample size.

We acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, its observational nature implies potential information bias. Additionally, the single-center approach of the present study, which was conducted at a tertiary cardiac hospital serving as a referral center for severe and complex cases, suggested a greater prevalence of heart failure and death. Another possible limitation is the inclusion of 17.7% of possible cases, however, this reflects real-world clinical practice. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution, and there is a need for external validation in hospitals with different clinical and microbiological profiles to confirm its generalizability and broader applicability. Future studies may also explore its role in long-term outcome prediction.

Conclusion

Clinical and laboratory findings at admission accurately predicted in-hospital mortality in patients with left-sided infective endocarditis. The EndoPredict-Px score represents a significant advancement in the early assessment of mortality risk in these patients. The system has the potential to simplify and make decision making more accessible.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Njuguna, B., Gardner, A., Karwa, R. & Delahaye, F. Infective endocarditis in low- and middle-income countries. Cardiol. Clin. 35, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2016.08.011 (2017).

Delgado, V. et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 44, 3948–4042. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad193 (2023).

Mir, T. et al. Predictors of complications secondary to infective endocarditis and their associated outcomes: A large cohort study from the national emergency database (2016–2018). Infect. Dis. Ther. 11, 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00563-y (2022).

Becher, P. M. et al. Temporal trends in incidence, patient characteristics, microbiology and in-hospital mortality in patients with infective endocarditis: A contemporary analysis of 86,469 cases between 2007 and 2019. Clin. Res. Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-022-02100-4 (2022).

Habib, G. et al. Clinical presentation, aetiology and outcome of infective endocarditis. Results of the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European infective endocarditis) registry: A prospective cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 40, 3222–3232. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz620 (2019).

Grinberg, M. & Solimene, M. C. Historical aspects of infective endocarditis. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras 1992(57), 228–233. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-42302011000200023 (2011).

Habib, G. et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The task force for the management of infective endocarditis of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS), the European association of nuclear medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 36, 3075–3128. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319 (2015).

McDonald, E. G. et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of infective endocarditis in adults: A WikiGuidelines group consensus statement. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2326366. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.26366 (2023).

Park, L. P. et al. Validated risk score for predicting 6-month mortality in infective endocarditis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5, e003016. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.003016 (2016).

Delahaye, F. et al. In-hospital mortality of infective endocarditis: Prognostic factors and evolution over an 8-year period. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 39, 849–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365540701393088 (2007).

Damasco, P. V. et al. Epidemiological and clinical profile of infective endocarditis at a Brazilian tertiary care center: An eight-year prospective study. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 52, e2018375. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0375-2018 (2019).

Mostaghim, A. S., Lo, H. Y. A. & Khardori, N. A retrospective epidemiologic study to define risk factors, microbiology, and clinical outcomes of infective endocarditis in a large tertiary-care teaching hospital. SAGE Open Med. 5, 2050312117741772. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312117741772 (2017).

Mansur, A. J. et al. Determinants of prognosis in 300 episodes of infective endocarditis. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 44, 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-1011974 (1996).

Rizzo, V. et al. Infective endocarditis: Do we have an effective risk score model? A systematic review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1093363. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1093363 (2023).

Varela Barca, L. et al. Prognostic assessment of valvular surgery in active infective endocarditis: Multicentric nationwide validation of a new score developed from a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 57, 724–731. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezz328 (2020).

Wei, X. B. et al. Age, creatinine and ejection fraction (ACEF) score: A simple risk-stratified method for infective endocarditis. QJM 112, 900–906. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcz191 (2019).

Olmos, C. et al. The evolving nature of infective endocarditis in Spain: A population-based study (2003 to 2014). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 70, 2795–2804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.005 (2017).

Chee, Q. Z. et al. The SHARPEN clinical risk score predicts mortality in patients with infective endocarditis: An 11-year study. Int. J. Cardiol. 191, 273–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.236 (2015).

Fowler, V. G. et al. The 2023 duke-international society for cardiovascular infectious diseases criteria for infective endocarditis: Updating the modified duke criteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 77, 518–526. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad271 (2023).

Shmueli, H. et al. Right-sided infective endocarditis 2020: Challenges and updates in diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e017293. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.017293 (2020).

Akinosoglou, K., Apostolakis, E., Koutsogiannis, N., Leivaditis, V. & Gogos, C. A. Right-sided infective endocarditis: Surgical management. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 42, 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezs084 (2012).

Kamaledeen, A., Young, C. & Attia, R. Q. What are the differences in outcomes between right-sided active infective endocarditis with and without left-sided infection?. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 14, 205–208. https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivr012 (2012).

Riley, R. D. et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ 368, m441. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m441 (2020).

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G. & Moons, K. G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement. BMJ 350, g7594. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7594 (2015).

Harris, P. A. et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 95, 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 (2019).

Young, P. J. et al. Early peak temperature and mortality in critically ill patients with or without infection. Intensive Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2478-3 (2012).

Henning, D. J. et al. The absence of fever is associated with higher mortality and decreased antibiotic and IV fluid administration in emergency department patients with suspected septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 45, e575–e582. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002311 (2017).

Sundén-Cullberg, J. et al. Fever in the emergency department predicts survival of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock admitted to the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 45, 591–599. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002249 (2017).

Gatti, G. et al. Using surgical risk scores in nonsurgically treated infective endocarditis patients. Hellenic. J. Cardiol. 61, 246–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjc.2019.01.008 (2020).

Alves, S. G., Pivatto Júnior, F., Filippini, F. B., Dannenhauer, G. P. & Miglioranza, M. H. SHARPEN score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality in infective endocarditis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 92, 124–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2021.05.036 (2021).

García-Granja, E. P. et al. Predictive model of in-hospital mortality in left-sided infective endocarditis. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition) 73, 902–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2019.11.003 (2020).

Wei, X. et al. ASSESS-IE: A novel risk score for patients with infective endocarditis. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 17(3), 695–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12265-023-10456-9 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.M., G.L.R., and F.B.; Data curation: G.L.R., G.B., and R.A.; Formal analysis: M.M., G.L.R., J.R., and D.M.; Docking studies: D.M. ; Funding acquisition: F.B.; Investigation: M.M., D.M.; Methodology: M.M., G.L.R., G.B., J.R.; Project administration S.P., L.P., and F.B.; Resources: F.B.; Supervision: S.P., and F.B.; Validation: L.P., S.P. and F.B.; Writing – original draft, M.M. and G.L.R.; Writing – review & editing: L.P., S.P., and F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paixão, M.R., Besen, B.A.M.P., Felicio, M.F. et al. Prediction of hospital mortality in patients with left-sided infective endocarditis using a score in the first hours of admission. Sci Rep 15, 28566 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13592-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13592-1