Abstract

Grape disease image recognition is an important part of agricultural disease detection. Accurately identifying diseases allows for timely prevention and control at an early stage, which plays a crucial role in reducing yield losses. This study addresses the problems in grape leaf disease recognition under small-sample conditions, such as the difficulty in capturing multi-scale features, the minuteness of features, and the weak adaptability of traditional data augmentation methods. It proposes a solution that combines a multi-scale feature hybrid fusion architecture with data augmentation. The innovation of this study lies in the following four dimensions: (1) Utilize generative models to enhance the cross-category data balancing ability under small-sample conditions and enrich the sample information in the dataset. (2) Innovatively propose the LVT Block, a multi-scale information perception hybrid module based on the Ghost and Transformer structures. This module can effectively acquire and fuse multi-scale information and global information in the feature map. (3) Use the dense connection method to combine the LVT Block and the MARI Block to propose a new architecture, the DLVT Block. By fusing multi-scale information and global information, it improves the richness of feature information. It also uses the MARI to enhance the model’s perception of disease areas and constructs an end-to-end lightweight model, DLVTNet, using the DLVT Block. Experiments show that this method achieves an average recognition rate of 98.48% on the New Plant Diseases Dataset. The number of parameters is reduced to 42.7% of that of MobileNetV4, and it maintains an accuracy of 96.12% in the tomato leaf disease test. This paper embeds pathological features into the generative adversarial process, which can effectively alleviate the problem of insufficient samples in intelligent agricultural detection. It provides a new method system with strong interpretability and excellent generalization performance for disease detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to relevant data, grapes, as an important economic crop, are widely cultivated around the world and have a broad range of applications. However, during the cultivation period, grapes are susceptible to various diseases caused by bacteria, fungi, and pests, which significantly reduce yield and affect daily cultivation practices1. This existing challenge has a severe impact on global grape cultivation. Early identification and management of grape diseases can effectively reduce cultivation losses and improve crop quality2. Nevertheless, the diversity of grape diseases and the complexity of their conditions pose significant difficulties in disease detection3. For a long time, the primary method for grape disease detection has been manual inspection, which is time-consuming and subject to the subjectivity and expertise of the inspector, affecting the accuracy of disease identification. Therefore, developing an effective and rapid method for disease identification holds substantial practical value. This need provides an opportunity for the application of computer-aided diagnostic systems in agriculture. By utilizing image processing, machine learning, and deep learning technologies, various feature extraction methods can meet the practical requirements of disease detection. However, the research prospects for automatic grape disease detection are not optimistic due to limitations in dataset acquisition, the subtlety of disease defects, uneven distribution, significant differences between similar diseases, and subtle distinctions between different diseases, making it a challenging task.

In past research, vision-based detection methods have been introduced into grape disease detection and have achieved numerous results. However, early disease identification methods primarily relied on image processing and machine learning techniques, which often required manual design of parameter feature extractors. In recent years, with the advancement of artificial intelligence technology, deep network models with powerful capabilities have emerged, based on the stacking of multiple layers of artificial neurons. These methods have been applied to agricultural leaf disease detection and have effectively identified tomato diseases. Unlike traditional machine learning methods, deep learning-based network models can autonomously learn the relationships between different samples in the dataset and output appropriate recognition results for input images without manual design. Although these models increase the number of parameters and training time, they offer stronger recognition capabilities and self-iterative abilities compared to machine learning models4. However, the training of deep learning models mainly depends on the input training data, and practical constraints often lead to data imbalance issues due to insufficient sample sizes, as well as significant intra-class variations in disease samples at different stages, severely limiting the recognition performance of deep learning models.

The structure of the text consists of related work, Materials and Methods, Experimental results and analysis, and Conclusions and Discussion. The related work section delves into existing research achievements in the field; the Materials and Methods section provides a detailed description of the research work; the Experimental results and analysis section primarily validates and analyzes the contributions of this paper; finally, the Results and Discussion section concludes the paper and summarizes the limitations of the study.

Related works

The following section reviews relevant research on agricultural leaf disease classification and grape leaf disease classification, which integrates machine learning and deep learning structures. These studies are discussed and analyzed in detail in the subsections.

Machine learning methods

Machine learning methods have been widely applied in agricultural visual disease detection. These methods can autonomously extract features from images using designed feature extractors, such as Gabor filters, gray-level co-occurrence matrices, local binary patterns, and wavelet transforms. Additionally, classification algorithms like K-nearest neighbors, decision trees, random forests, and support vector machines (SVM) are used to classify the extracted features. Relevant research in agriculture is summarized below. Zhang et al. proposed a novel genetic algorithm-based SVM (GA-SVM) for the classification of corn diseases. The genetic algorithm automatically optimizes the penalty factor and kernel function, and the extracted features are input into the GA-SVM classification model using the rotation orthogonal method, achieving better performance than traditional SVM models5.

Pan et al. introduced a citrus surface defect recognition method based on KF-2D-Renyi and ABC-SVM. The method uses the dark channel prior (DCP) technique for image defogging, followed by the Kent-based firefly algorithm to optimize the 2D-Renyi threshold segmentation algorithm for citrus surface defect segmentation. The resulting vectors are input into the SVM for classification, achieving high accuracy in identifying eight types of citrus surface defects6. Ustad et al. developed a grapevine disease classification system based on image processing. The K-means clustering algorithm is used to extract disease regions from images, and features such as color and shape are extracted. SVM is then employed for classification, effectively identifying Black rot and Downy mildew7. Phookronghin et al. utilized self-organizing feature maps (SOFM) to extract grape leaf disease regions and implemented a two-level simplified fuzzy ARTMAP (2L-SFAM) for grape leaf disease recognition and classification8. Mohammed et al. established an artificial intelligence technique for grape leaf disease detection and classification. The K-means algorithm is used for segmentation, and texture features are extracted from the segmented grape leaves. Multiple SVMs and Bayesian classifiers are then employed to determine the type of grape leaf disease9. Alishba et al. proposed a grape leaf disease recognition system that combines local contrast haze reduction (LCHR) and LAB color conversion to select the optimal channel. Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) is used to extract disease features, and a multi-class SVM is employed to identify three types of grape diseases10. Pranjali et al. used K-means clustering to extract color and texture features from lesion regions in leaf images and combined them with SVM for disease detection, achieving an accuracy of 88.89%11. Jaisakthi et al. also utilized SVM for grape leaf disease recognition. The authors combined global thresholding and supervised methods for detailed segmentation of disease regions and tested multiple machine learning algorithms, with SVM achieving a recognition accuracy of 93%12.

Although machine learning-based detection methods have played a crucial role in leaf disease detection and yielded numerous research outcomes, these methods still require manual design of feature extraction techniques, such as K-means, global thresholding, and 2D-Renyi, for extracting features like color and shape. This limits their practical application in effectively identifying samples with complex disease characteristics. Consequently, researchers have gradually shifted their focus to deep learning-based detection methods, which enable end-to-end detection systems and significantly enhance the versatility of automatic detection algorithms.

Deep learning methods

With the further development of disease recognition technology, deep learning-based methods have become powerful tools for detecting agricultural leaf diseases. Researchers have attempted to combine models such as AlexNet, VGG, ResNet, and MobileNet with transfer learning techniques to achieve disease recognition, yielding numerous research outcomes.

Chen et al. proposed a tomato leaf disease recognition framework based on ABCK-BWTR and B-ARNet. The framework uses binary wavelet transform combined with Retinex denoising to enhance images, optimizes KSW to separate leaves from the background, and employs a dual-channel residual attention network for recognition13. Goncharov et al. improved the deep Siamese network and single-layer perceptron classifier, expanding the database to include five groups of grape, corn, and wheat images, effectively increasing plant disease detection accuracy to 96%14. Bao et al. designed a lightweight SimpleNet model for wheat head disease detection in natural scene images. The model connects the downsampled feature maps output from inverted residual blocks with the average pooled feature maps of the input inverted residual blocks, achieving fusion of features at different depths and reducing the loss of detailed disease features during downsampling, achieving an accuracy of 96.71%15. Atila et al. investigated the use of the EfficientNet architecture for plant leaf disease classification on the PlantVillage dataset, achieving high classification accuracy on both the original and augmented datasets using transfer learning16. Atila et al. studied the use of the EfficientNet architecture for the classification of plant leaf diseases on the PlantVillage dataset, and achieved high classification accuracy on both the original and enhanced datasets through transfer learning methods17. Fang et al. proposed a new network architecture, HCA-MFFNet, which utilizes hard coordinated attention (HCA) allocated at different spatial scales and multi-feature fusion techniques to effectively identify corn leaf diseases in complex backgrounds, achieving a recognition accuracy of 97.75% 18. Zhang et al. introduced the asymptotic non-local means algorithm (ANLM) to reduce image noise interference and proposed a multi-channel auto-guided recursive attention network (M-AORANet) to address tomato leaf disease recognition issues to some extent19. Sharma et al. proposed a deeper lightweight multi-class model, DLMC-Net, for plant leaf disease detection. The model introduces collective blocks and channel layers to avoid gradient vanishing issues and outperforms other network models in detecting various plant leaf diseases20. In deep learning-based network models, improving attention mechanisms can effectively enhance model recognition performance. Zhao et al. integrated the SE-Net attention mechanism into the ResNet-50 model to help extract effective channel information and combined it with a multi-scale feature extraction module for tomato disease recognition21. Zhao et al. embedded the CBAM attention mechanism into the Inception network model to identify corn, potato, and tomato diseases22. Zeng et al. proposed a self-attention convolutional neural network (SACNN) and added it to a basic network for crop disease recognition, achieving good recognition results on the MK-D2 dataset23. Chen et al. proposed an attention module (LSAM) for MobileNet V2, forming the Mobile-Atten model, which achieved an average recognition accuracy of 98.48% for rice diseases in complex backgrounds 24. Miaomiao et al. proposed a joint convolutional neural network architecture, United-Model, based on ensemble methods, achieving grape disease recognition with an average accuracy of 99.17% on the validation set25. Suo et al. combined Gaussian filtering, Sobel smoothing, Laplacian operators, and the CoAtNet network to propose the coordinated attention shuffle mechanism-asymmetric multi-scale fusion module network model (CASM-AMFMNet), achieving effective recognition of grape leaf diseases26. Liu proposed a CNN model combining Inception structure and dense connection strategy, which outperformed GoogLeNet and ResNet-34 in grape disease recognition27. Cai et al. used binary wavelet transform combined with variable threshold methods and NL-means improved MSR algorithm (VN-BWT) to enhance grape leaf images and proposed a novel Siamese network (Siamese DWOAM-DRNet) with dual-branch residual modules (DRM) and dual-factor weight optimization attention mechanism (DWOAM), enhancing the ability to classify grape leaf diseases in complex backgrounds28. Alsubai et al. developed a hybrid deep learning model for grape disease classification based on improved Salp Swarm optimization. The model first employs median filtering for preprocessing, then introduces dilated residual networks and clipped neural network gated recurrent units, enabling effective classification of four types of grape diseases29. Alishba Adeel et al. proposed a grape disease detection method combining deep learning models with machine learning techniques. Specifically, they utilized pre-trained AlexNet and ResNet101 models for feature extraction through transfer learning, followed by classification using least squares support vector machines (LS-SVM)30. Ren et al. integrated Adown and CGBlock structures to enhance the model’s ability to extract global information while significantly reducing computational resource consumption. The model achieves an accuracy of 94.7% while maintaining lightweight performance31.

Transformer methods

In recent years, Transformers have been increasingly applied in various fields, demonstrating their powerful ability to capture long-range dependencies and effectively focus on disease locations in different regions of images32. Researchers have applied Transformers in agricultural and grape leaf visual detection, achieving certain results.

Vallabhajosyula et al. combined Transformers with the ResNet-9 model for leaf disease classification and detection, showing superior performance to mainstream CNN models33. Wei Li integrated the CBAM attention mechanism and Transformer framework into ResNet-50, achieving high-precision tomato recognition and effective classification on the PlantDoc dataset34. Chen et al. addressed the challenge of tomato leaf disease recognition by first using CyTrGan to generate a certain number of sample images to enrich the dataset. They then employed a densely connected CNN network with Transformer structure, experimentally verifying effective tomato disease recognition35. Han et al. used a dual-channel Swin Transformer for image detection, with one channel receiving the initial image input and the other receiving edge information input, demonstrating effective recognition of lignified leaf diseases36. Hu et al. proposed a hybrid framework, FOTCA, to address the poor performance of Transformers on small and medium-sized datasets. The framework uses adaptive Fourier neural operators and Transformer architecture to effectively extract global features, achieving effective disease recognition37. Li et al. improved the MobileViT model with residual structures to obtain the PMVT model and integrated the CBAM attention mechanism into the ViT encoder. The model was tested on datasets including wheat, coffee, and rice, achieving excellent recognition accuracy38.

Karthik et al. proposed a novel dual-track feature fusion network, GrapeLeafNet, which uses InceptionResNet and CBAM for local feature extraction and Shuffle-Transformer for global feature extraction, achieving high recognition capability for grape leaf disease detection39. Li et al. proposed an improved YOLOV5s-based apple leaf detection method, incorporating Transformers and the CBAM attention mechanism to reduce interference from invalid background information and enhance the expression of disease features. The experimental results achieved an average recognition accuracy of 84.3% and demonstrated strong robustness40. Liu et al. proposed an optimized Efficient Swin Transformer model, introducing a token generator and feature fusion aggregation mechanism to reduce the number of tokens processed. The method exhibits strong recognition performance, with recognition accuracy improving by 4.29% compared to the original Swin Transformer41. Zhang et al. proposed a feature extraction mechanism combining Transformers and Diffusion for jujube tree disease detection in desert areas, achieving lightweight model design and excellent recognition capability with a recognition accuracy of 93%42. Li et al. proposed a Transformer-based multimodal detection method, integrating RGB images, hyperspectral images, and environmental sensor readings to build a multimodal dataset, achieving a recognition accuracy of 94%43. Lu et al. embedded the Transformer framework into the GhostNet network to enhance CNN model recognition performance in complex background leaf images and proposed the GeT network model, which achieved a recognition accuracy of 98.14%44. Karthik et al. proposed a dual-path network combining Swin Transformer and Group Shuffle Residual DeformNet. This network effectively extracts local and global features from image samples, and achieves a recognition accuracy of 98.6% through cross-dimensional interaction45.

In agricultural visual inspection, existing methods have gradually evolved from traditional machine learning methods to those combining deep learning and the Transformer architecture. As visual inspection technology advances, the details of leaf disease detection are being increasingly explored. There has been a shift from manually-designed feature extraction algorithms to automatically-designed ones, and from considering disease recognition of the entire image to taking into account the relationships between distributed disease features within the image, aiming for more accurate leaf disease recognition over time.

This paper summarizes the existing research foundation and aims to address the issues in current agricultural visual inspection algorithms, including data imbalance, large inter-class differences, small differences between different classes, uneven disease features, tiny feature defects, and large model sizes. Based on these problems, this study fills several research gaps. First, a data augmentation method using deep learning technology is proposed to solve the problems of data imbalance and small sample size. Generative adversarial networks can be used to generate new image samples, enriching the dataset with diverse disease images. Second, a lightweight neural network model called DLVTNet is introduced. This model combines Ghost modules and the Transformer, which can capture multi-scale and global information from sample images. While achieving model lightweight, it enhances the model’s ability to detect complex and subtle defects. Then, in the DLVT Block, the obtained multi-scale and global information is concatenated in the channel dimension through dense connections to enhance the richness of information. Subsequently, the MARI Block embedded with the MELA attention mechanism is used to process the feature maps, thereby improving the accuracy of the model in disease classification. The main contributions of this study lie in using a generative network model to process small-sample datasets to enrich the sample information of the dataset, and introducing multi-scale information and a lightweight Transformer structure to enhance the model’s ability to locate disease defects.

Materials and methods

Image datasets and preprocessing

The grape leaf disease dataset used in this study comes from the publicly available plant disease classification dataset New Plant Diseases Dataset on Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/vipoooool/new-plant-diseases-dataset). Grape leaf images from this dataset were selected as the image dataset for this study. The dataset includes images of three types of grape leaf diseases as well as healthy leaves, totaling 7222 images, divided into four categories. The images have been resized to 256 × 256 pixels and processed using oversampling. Sample images from the dataset are shown in Fig. 1.

Image preprocessing

In this section, the research mainly focuses on the problems of dataset imbalance, large inter-class differences, and small differences between different classes in leaf disease images. Affected by real-world conditions, it is difficult to collect sufficient samples for all categories during dataset acquisition, which makes it challenging for the model to learn comprehensively. Moreover, in existing methods for leaf visual inspection, although various data augmentation methods such as image processing, mixup, and generative adversarial networks are used, they mainly focus on the issue of differences in the number of categories. However, they do not address the problem that leaf diseases have different feature distribution patterns due to the influence of the onset time. We use the generative adversarial network model to enrich the dataset information based on the existing dataset samples. This is to compensate for the representations of diseases at different onset stages and make the sample distribution of the dataset more reasonable.

In the field of agricultural disease detection, the recognition performance of deep learning (DL) models relies on high-quality and diverse training data, which helps models better learn data distributions and reduce overfitting. In practical applications, datasets with rich and diverse data enable models to perform more stably when processing input information. However, traditional image enhancement methods, such as rotation, mirroring, and contrast adjustment, can only make simple adjustments to the spatial layout or contrast features of images, making it difficult to effectively simulate the changes in characteristic diseases at different time stages. In the case of grape leaf disease detection, the significant differences in disease manifestation caused by varying onset times make the effect of traditional data augmentation methods limited in enriching disease dataset information. Additionally, the influence of real-world environmental factors leads to significant differences in the number of images of different diseases in the dataset, causing the model to overlearn categories with more samples during training and misclassify categories with fewer samples, thereby affecting the models generalization ability and practical application performance.

With the continuous development of generative models, they have been widely applied in processing small-sample datasets. Generative network models can generate new sample information based on existing data, effectively alleviating the problem of data insufficiency. Among various generative models, FastGAN stands out due to its advantages of fast training, low computational resource requirements, and excellent generation effects, making it particularly advantageous in data augmentation46. Therefore, this study employs the FastGAN adversarial generative network to enhance the existing dataset, increasing the diversity and balancing the class distribution of image data.

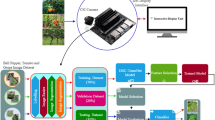

The different processing methods applied to the dataset are illustrated in Fig. 2. During the experiment, the augmented dataset was divided into training and testing sets in an 8:2 ratio, as shown in Table 1. Table 1 details the number of samples in the grape leaf disease dataset used in this study, where “Original Dataset” represents grape leaf images of different categories from the publicly available New Plant Diseases Dataset; “Image Processing” represents the dataset expanded using image processing methods; and “FastGAN” represents the dataset generated using the FastGAN adversarial generative network with different sample counts.

To visually observe the distribution of dataset samples, this study employs the T-SNE algorithm for visualization analysis, with results shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3a–c respectively display the sample distributions of the original dataset, the image processing dataset, and the adversarial generation network dataset. As observed in the figures, the original dataset exhibits disordered sample distributions, with healthy leaf samples (represented in green) primarily located in the right and upper-left regions, indicating significant inter-class differences. Other studies (represented in red, blue, and orange) show similarly disordered distributions for different disease samples.

In Fig. 3b, although image processing techniques were used to enhance the dataset, the sample distributions remain disordered. Healthy leaf samples are distributed in the upper and central regions, suggesting that even after image processing, the dataset still suffers from large intra-class differences and small inter-class differences. This indicates that traditional image enhancement methods have limited effectiveness in improving dataset distributions and are unable to adequately address the issue of data diversity in agricultural disease detection.

However, in Fig. 3c, the dataset processed by the FastGAN generative adversarial network model shows an obvious clustering phenomenon of different samples in their respective regions, and the distribution is more reasonable. This phenomenon confirms our conjecture. Compared with traditional image processing methods, using a generative model to compensate for the missing information in the dataset can optimize the sample distribution of the dataset and highlight the boundaries between different categories in the high-dimensional space.

In addition, this method can also effectively enrich the disease representations at different stages. As shown in the “Black Rot” in Fig. 2c, images of the early and late stages of the disease are generated. We believe that by processing the dataset in this way, the full-time-period expression of diseases can be enriched, which helps the model fully learn disease defects.

DLVTNet model body framework

In this section, we summarize the agricultural visual inspection methods and conduct research based on the existing problems of uneven distribution of disease features and tiny disease features. A neural network model named DLVTNet is proposed. This model combines Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformers, and it is mainly composed of a DLVT Block (Dense-connected Light-weight Vision Transformer Block) and a Down Sample (downsampling module).

This model is capable of recognizing and detecting diseases on grape leaves. As shown in Fig. 4, the DLVT Block uses dense connections to connect the LVT Block (Lightweight Vision Transformer Block) and the MAIR Block (Multi-scale Attention Inverted Residual Block) to increase the reuse of input image information47. Additionally, within the LVT Block, the Ghost Module is used to extract multi-scale information from images, and the LVT FFN enhances the model’s nonlinear capabilities. Furthermore, self-attention mechanisms are used only in the final LVT Block to reduce the computational resources required by the model. Within the DLVTNet model structure, the DLVT Block is primarily used to extract features from images, followed by downsampling operations performed by the DS Block structure. In this model, the first layer of the downsampling module uses a 4 × 4 convolutional layer to acquire spatial features from a larger receptive field. To avoid losing detailed features of the input image due to the use of large convolutional kernels, the second and third layers of the downsampling module use 2 × 2 convolutional layers for downsampling.

Dense-connected lightweight vision transformer block

In the detection of agricultural leaf diseases, the main difficulties lie in the complex and diverse presentation of disease features, as well as the problems of small and unevenly distributed disease features, which pose challenges to leaf disease recognition. To address this issue, we designed a structure called DLVT Block. By combining the CNN + Transformer structure, it can extract important defect regions in the image and enhance the model’s attention to tiny defects in the image. This module is mainly composed of the LVT module with a Transformer structure and the MAIR module with a convolutional neural network structure, and uses a dense connection method to connect the output of each layer to the input of the next layer along the channel dimension.

As shown in Fig. 5, the DLVT module structure consists of three LVT modules and one MAIR module. The first three LVT modules do not add the self-attention mechanism. Instead, they enhance the image representation ability through the Ghost Module and the LVT Feed-Forward Network (LVT FFN). Then, the LVT module 3 with the self-attention mechanism added is used to extract the global information in the image. Finally, using the dense connection method, before the MAIR module extracts local feature information from the input, the outputs of the first three LVT modules are connected to the input of the DLVT module along the channel dimension.

Lightweight vision transformer block

In this section, a multi-scale lightweight Transformer architecture proposed in this paper is mainly introduced. The aim is to increase the richness of information obtained by the model. Meanwhile, the long-range dependency of the self-attention mechanism is utilized to obtain the positions of tiny defects in the image and enhance the model’s attention to tiny defects. The Transformer architecture is mainly composed of a self-attention mechanism and a feed-forward network (FFN). The self-attention mechanism can effectively extract global information from the input, while the feed-forward network enhances the expression ability of the input image features.

Among them, Swin Transformer uses the W-MSA module based on the shifted window multi-head self-attention mechanism to replace the global attention mechanism in the Vision Transformer (VIT). Then, a two-layer multi-layer perceptron (MLP) with a Gelu non-linear activation function is used in the middle to enrich the image features extracted by W-MSA, as shown in Fig. 6a. To achieve a lightweight Transformer model, EfficientFormer proposes a new attention variant called GroupAttention, which is combined with a deep-learning-based Token interaction structure and a linear feed-forward network (FFN) to form a new Transformer module, as shown in Fig. 6b.

To further lightweight the Transformer model, this paper proposes a new Transformer Block structure, mainly consisting of Ghost model, CLSHSA, and LVT FFN, as shown in Fig. 6c. Among them, Token Interaction is mainly responsible for local feature aggregation or conditional position embedding, CLSHSA is mainly responsible for modeling global context, and LVT FFN is mainly responsible for channel interaction. By combining Token Interaction and CLSHSA, local and global dependencies are captured in a lightweight manner. To reduce computational redundancy in the neural network model, CLSHSA is not used in the first and second LVT Blocks, but dense connections are used to input the first two layers of LVT Block into the last LVT Block to obtain global feature information from multi-level features of the input image, and then the obtained feature information is passed to the last layer of MARI Block. In the LVT block, there are two situations depending on the stage. In each DLVT Block, the first two LVT Blocks do not include CLSHSA, but instead use dense connections to uniformly input the output images obtained from the first two LVT Blocks into the last LVT Block with CLSHSA, which helps to better capture multi-level features of the input image.

The Ghost module and LVT FFN structures are shown in Fig. 7. Figure 7a shows the ghost module, which mainly processes input data at multiple scales to introduce more local inductive bias. In its structure, a 1 × 1 convolution is first used to compress the number of channels of the input image, then depth-separable convolution is used to generate more feature maps, and different feature maps are concatenated together to generate new outputs. This method can effectively reduce the number of parameters and computational cost required for calculation while generating rich feature maps.

LVT FFN mainly consists of two 1 × 1 convolutions and a Relu non-linear activation function, which can further non-linearly map and extract high-level features from the input feature maps, as shown in Fig. 7b. First, when the feature map passes through the first layer of 1 × 1 convolution, it can expand the number of image channels. After passing through the non-linear activation function, it then passes through the second 1 × 1 convolution to integrate the image channels to retain important image feature information channels.

Channel lightweight single-head self-attention

In the Transformer architecture, global information extraction from input data is primarily achieved through the self-attention mechanism. In self-attention, this is accomplished by calculating the relationships between each element in the input image and other elements to extract global feature information. Initially, the image features are processed through linear transformations to obtain three matrices: Q (Query), K (Key), and V (Value). The matrices K and Q are used to compute the attention weights, while V represents the values used for weighted summation to obtain the final output. However, due to the quadratic computational complexity of self-attention relative to the size of the image, neural network models using Transformer structures require substantial computational resources. As a result, many lightweight methods for the self-attention mechanism have been proposed.

Figure 8 shows the design of various single-head attention mechanisms. Figure 8a shows a single-head self-attention mechanism that retains all channels of the input image, then calculates the weights of the self-attention mechanism and weights the values in the image. However, this method considers all image channels when calculating K and Q, resulting in some computational redundancy. Figure 8b shows a lightweight single-head self-attention mechanism proposed in the SHViT model. In this attention mechanism, a pre-convolution method is used to split the input image channels into two parts. One part of the channel images uses a self-attention mechanism to obtain global information. The other part of the channel images is not processed. Finally, the feature maps obtained from both parts are concatenated.

In this paper, to achieve a lightweight Transformer structure, a single-head self-attention mechanism combined with CNN channel attention, called CLSHSA, is proposed. The inspiration primarily comes from the fact that the matrices Q and K in self-attention mechanism calculations generate significant redundancy, and the channel dependency of matrices Q and K is lower than that of matrix V when processing images48. The CLSHSA structure is shown in Fig. 9a. Before calculating the matrices K and Q, the input image has its channel dimensions reduced using a CL Block (Channel Lightweight Block). Self-Attention is then used to weight the input matrix V, thereby extracting global information and achieving a lightweight processing of the self-attention mechanism49. The computation of CLSHSA is illustrated in Eqs. 1, 2, and 3.

In the CL Block, the main components are a fully connected layer, pooling layer, Sigmoid activation function, and ReLU activation function, as shown in Fig. 9b. The data input to the CL Block undergoes global pooling first, followed by two fully connected layers and the ReLU activation function to obtain the channel weight information of the image. The Sigmoid function is then used to generate a weight vector to apply weighting to the image channels. Finally, another fully connected layer integrates the weighted channel information and removes redundant channel information, achieving lightweight processing of the self-attention mechanism.

Multi-scale attention inverted residual block

The MAIR Block is located at the last step of the DLVT Block. Its purpose is to form the CNN structure in the model by combining the multi-scale attention mechanism and the inverted residual block. It combines the previously extracted multi-scale information and the information focusing on tiny regions to extract the defect positions in the model and constrain the important channels. The structure is illustrated in Fig. 10a and mainly consists of two 1 × 1 pointwise convolutions, one 3 × 3 depthwise convolution, Batch Normalization, and the Multi-scale Efficient Local Attention (MELA) mechanism. The input image first undergoes a 1 × 1 pointwise convolution to expand the image’s expressiveness, then the expanded channels are processed with depthwise convolution, and ReLU activation function is applied to enhance the non-linear expression of image features. Finally, a second pointwise convolution integrates the number of channels, and the integrated image is fed into the MELA attention mechanism.

In this paper, to effectively extract local feature information from images after concatenation, a Multi-scale Efficient Local Attention (MELA) mechanism is proposed. MELA is inspired by the CA (Coordinate Attention) and ELA (Efficient Local Attention) mechanisms. It obtains spatial weights for different regions of the image based on horizontal and spatial positional information of the input image50. ELA, utilizing the coordinate positional information approach from CA, redesigns the attention mechanism structure to achieve a lightweight implementation without dimensionality reduction. The structure is shown in Fig. 10b. The goal of this paper is to achieve effective extraction of features with uneven spatial distribution. To this end, a multi-scale attention mechanism, MELA, is constructed, with its structure illustrated in Fig. 10c.

The image input to the MELA attention mechanism is processed in two parts. One part uses average pooling with kernels of (H, 1) and (1, W) to extract horizontal and vertical feature vectors, respectively. These extracted feature vectors are then processed using a 3 × 3 convolutional layer and Batch Normalization, with Sigmoid calculating the spatial weights of the input image in the horizontal and vertical directions. In the other part, the input image is directly processed using a 3 × 3 convolutional layer and Batch Normalization, followed by Sigmoid to obtain the spatial weights of the image. These weights are combined with the horizontal and vertical weights of the image to perform weighted processing. This method effectively focuses on disease areas in the image by combining the weights at different locations and the multi-scale weights of the entire image.

In the MELA attention mechanism, to obtain attention weights at different scales, the input representations of height h and width w in channel c are first obtained using pooling kernels of (H, 1) and (1, W) along the vertical and horizontal directions, respectively. The calculation process is shown in Eqs. 4 and 5.

where \({z}_{c}\) represents the encoding result of average pooling in the c-th channel in the horizontal direction w and vertical direction h; \({x}_{c}\) represents the feature value of the c-th channel at height h and width w in the feature map. To effectively utilize the obtained feature vectors, we apply one-dimensional convolution (conv1d) to process information in the horizontal and vertical directions. The processed information is then enhanced using Batch Normalization (BN), and finally, the attention weights are computed using the Sigmoid function. The calculation process is shown in Eqs. 6 and 7. In these equations, \({F}_{w}\) and \({F}_{h}\) represent the convolution operations with 3 × 3 kernels in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively.

Then, to obtain multi-scale global weights, the input image feature information is processed using a convolution operation \({F}_{2}\) with a 3 × 3 kernel and Batch Normalization \({B}_{2}\), followed by the calculation of weights using the Sigmoid function. The calculation method is shown in Eq. 8.

Finally, the obtained weights \({g}^{h}\) and \({g}^{w}\) and multi-scale weights \({g}^{s}\) are used to weight the input image, resulting shown in Eq. 9.

where \(y\) is the final output of MELA. Inspired by CA attention and ELA attention, MELA can effectively combine spatial position information and multi-scale information to find regions of interest in the image, improving accuracy.

Experimental results and analysis

Experimental design

The computer used in this paper runs on Windows 11 operating system, using a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12,700 (2.10 GHz) processor. GPU acceleration is used for model training and testing, with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 (12G) GPU. The software environment uses Python 3.9.13, PyTorch 1.13.1, and CUDA 11.6 framework. Additionally, in training the neural network model, Adam is set as the optimizer, the learning rate is set to 0.000001, the number of iterations is set to epochs = 200, and the batch size is set to 16.

Evaluation indicators

In this study, precision, recall, accuracy, and F1 score are used to evaluate the recognition effect of different models on the grape leaf dataset. The calculation methods are shown in Eqs. 10, 11, 12, and 13.

where TP (True Positive) represents the number of positive samples correctly predicted as positive by the model; TN (True Negative) represents the number of negative samples correctly predicted as negative by the model; FP (False Positive) represents the number of negative samples incorrectly predicted as positive by the model; FN (False Negative) represents the number of positive samples incorrectly predicted as negative by the model.

In this study, precision represents the proportion of samples correctly judged as positive by the network model. Recall measures the proportion of positive samples correctly identified by the network model among the actual positive samples. Accuracy represents the proportion of total samples correctly classified by the network model. The F1 score comprehensively considers precision and recall, and is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. In addition, two parameters, Flops (floating-point operations) and Params (number of parameters), are introduced to evaluate the size of the model. The larger these two parameters, the more computational resources the model requires.

Model performance testing

In this study, to comprehensively evaluate the recognition ability of the model, we conducted a series of experiments under different batch sizes to determine the optimal batch size for training and verify the generalization performance of the model. In the experiments, we trained the model using three different batch sizes (8, 16, and 32) for comparison. Significantly different model performances were observed. Interestingly, when the batch size was 16, the average recognition accuracy of the model reached 98.48%, and the highest recognition accuracy reached 99.79%. Additionally, the experimental data showed that when the batch size was 32, the average recognition accuracy was 98.88%, while when the batch size was 8, the average recognition accuracy was 98.33%. Although the accuracy slightly decreased when the batch size was 8, the maximum difference in the highest recognition accuracy among different batch sizes was only 0.38%. The average highest recognition accuracy across the three batch sizes reached 99.60% (Table 2).

After determining the training batch size, we selected the parameter of batch = 16 to train the model. Each time we trained the model, we re-divided the dataset at a ratio of 8:2. The best average recognition accuracy could reach 98.58%, and the worst recognition accuracy could reach 98.27%. This issue was mainly due to the influence of dataset division. The difference in the number of easily recognizable samples in the test-set samples led to variations in recognition accuracy. However, the overall recognition accuracy of the model could still reach a relatively high level. Finally, the batch size had a certain impact on the model’s recognition accuracy; however, the impact on the model performance was minimal, and the model consistently demonstrated high-level performance under different conditions.

Considering the influence of dataset division on the model training results, a more comprehensive evaluation of the model’s learning ability on the grape dataset was needed. To address this issue, we adopted the K-fold cross-validation method in the study to estimate the model performance while avoiding overfitting and variance. This method could divide the dataset into k parts according to the given parameter k. We used (k-1) parts to train the model and the remaining 1 part for model testing, thereby effectively verifying the model’s recognition ability for the entire dataset. In our experiment, we used the standard value K = 10, trained the model 10 times, and calculated the average accuracy value each time, as shown in Fig. 11. Among them, the highest average accuracy value of the model learning was 98.64%, the lowest average accuracy value was 98.11%, the variance was 0.53%, and the overall average was 98.43%.

In addition, to reduce the influence of outliers, we also used the Trimmed Mean method to reduce the impact of outliers and improve the evaluation stability, and its value was 98.45%. After cross-experiment verification, the arithmetic mean was 98.41%, and the Trimmed Mean value of 98.45% was lower than the model accuracy value we used. This was mainly because in cross-validation, we set K = 10, and the test-set in the model testing accounted for only 10%. However, the difference between the values obtained by our 8:2 division method and the Trimmed Mean was not significant, and the variance of the average recognition accuracy was only 0.03. This proved that our model could fully learn the information in the dataset and achieve accurate results. Moreover, in this round, we obtained the highest recognition accuracy of the model, 99.79%, so we used it as the main comparison parameter to compare with the other data presented in this paper.

Comparative experiments of different network models

In this study, to test the recognition performance of the DLVT model, comparison experiments were conducted using existing mainstream image classification models. The comparative models discussed in this paper mainly include CNN models such as ConvNextV251, EfficientNetV252, MobileNetV453, ResNet5054, DenseNet12155, InceptionNext56,and GhostNetV257, as well as Transformer models such as Deit358, EfficientFormerV259, MobileVitV260, Swin TransformerV261, TinyVit62, CaitNet63, and MvitV264. The evaluation results of the comparative experiments are shown in Table 3. Among the 15 network models participating in the experiment, six models achieved an average recognition accuracy of over 96%: EfficientFormer, Swin Transformer, ResNet, DenseNet, TinyVit, and DLVTNet. Among these, DenseNet and DLVTNet achieved average recognition accuracies of over 98%. we also tested the model inference time. Under the same device conditions, DLVTNet achieves a single inference time of 8 ms, which is better than most of the models participating in the comparison experiment. Moreover, the average accuracy and model size of our proposed model are superior to those of MobileNet V4 (6.9 ms) and DeiT3 (7 ms). This indicates that the lightweight Transformer structure we proposed has stronger practical application capabilities compared with the existing mainstream Transformer structures, verifying the rationality of our design concept.

In addition, in the experiments, our proposed model outperforms DenseNet121 by 0.18 in terms of accuracy and 0.42 in terms of the F1-score. Considering that the DenseNet model mainly uses a pure convolutional approach, although it enhances the information reuse through its unique Dense connection method, it still faces certain difficulties when dealing with the free and tiny defects in grape leaf images. We will further verify this idea in the follow-up research.

Table 3 reflects the Flops and Params required for the different network models in the comparison experiment, which can be used to evaluate the computational resources required by each model. Of the 12 neural network models participating in the comparison experiment, only MobileNet V3 has a smaller Flops requirement than DLVTNet. However, MobileNet V3’s Params requirement is four times that of DLVTNet, and its average recognition accuracy is only 88.16%. DLVTNet requires only 0.49G of Flops, making it the second smallest after MobileNet, and it has the smallest Params requirement among the models tested, with a maximum difference of up to 28 times compared to others. Despite this, DLVTNet has the highest average recognition accuracy and Recall, with parameters of 98.48, 98.48, 98.47, and 98.46, respectively, as highlighted in black and bold in Table 3. Figure 12 shows the accuracy curve comparison of the network models in the parameter comparison experiment. Figure 12a compares the accuracy curves of DLVTNet and CNN models, while Fig. 12b compares those of LVTNet and Transformer models, marking the peak recognition accuracy curve. As shown in Fig. 12a, the recognition accuracy of the DLVTNet model can reach up to 99.79%. In addition, the accuracy curve of our model is pink. It is clearly superior to the existing lightweight CNN and lightweight Transformer models in terms of convergence speed, and its recognition ability is also comparable to that of large-scale SOTA models. Meanwhile, from the figure, we can observe that the accuracy curve of the model trained with the optimized dataset is smoother. Compared with the curves obtained from training with other datasets (as shown in Fig. 20), our dataset is more conducive to the full learning of the model.

In addition, to effectively express the recognition accuracy of the LDVTNet model for grape diseases, this paper also conducted confusion matrix tests on the models appearing in Table 2, and the test results are shown in Fig. 13. In the confusion matrix, B M, B R, H, and L B correspond to black_measles, black_rot, healthy, and leaf_blight, respectively, which are the four categories of grape leaves. These are abbreviations of the first letters of the grape diseases shown in Fig. 1. In the detection results shown in Fig. 13, the LDVTNet model achieved correct recognition of all sample images, while DenseNet, ResNet, Swin Transformer, Tiny Vit, and EfficientFormer performed slightly worse, with recognition errors of less than 5 samples. The remaining models have larger errors, with Deit3, MobileNet, and InceptionNext having more than 10 misrecognized samples, mainly distributed in the Black Measles and Black Rot disease categories. Primarily, since the visual manifestations of these two types of diseases tend to be similar, it is difficult for general models to effectively extract the differences in the similar minute features at the early onset stage of the diseases. This makes it challenging for the models to achieve effective recognition. Although we obtained favorable recognition results in the confusion matrix test, the data still comes from the dataset. Therefore, the effectiveness of the model when tested on real-world samples remains uncertain.

Confusion matrix test renderings for different network models, a–l Network models shown in Table 2, respectively.

Ablation experiments

In this study, to comprehensively validate the contributions of different methods to the recognition performance of the DLVTNet model, we designed a series of ablation experiments to systematically evaluate the impact of six methods on model performance. These methods include: using the original grape leaf dataset, using a dataset enhanced by FastGAN, introducing the Ghost module, introducing the CLSHSA attention mechanism, introducing the MARI module, and employing dense connections. Through these experiments, we can not only visually observe the independent contributions of different methods to model performance but also comprehensively assess their combined effects on improving model performance. The experimental results are detailed in Table 4 and Figs. 14, 15, covering multiple aspects such as average recognition accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, computational cost, parameter count, and feature extraction effectiveness.

Among the six methods tested in the ablation experiments, the base backbone network alone occupies 0.329 GFLOPs and 0.719 M Params. First, we compared the effects of different data augmentation methods on model recognition performance. As shown in Fig. 14a, the classification performance of the original dataset was poor, with significant overlaps between samples of different categories, particularly between blue and orange samples. This indicates that training the model using the original dataset with disordered sample distribution severely limits its classification performance, making it difficult to effectively distinguish between different disease categories. Subsequently, we introduced the FastGAN-enhanced dataset for comparison. As shown in Fig. 13b, using the optimized dataset with a more reasonable sample distribution can effectively enhance the model’s clustering ability and increase the inter-class distance, which verifies our assumption of optimizing the dataset through the generative model.

To further enhance the models feature extraction capabilities, we introduced the multi-scale Ghost module and the self-attention mechanism CLSHSA. The combination of these two methods not only improved the average classification accuracy by 2.52% but also effectively reduced the models computational cost and parameter count, decreasing them by 0.031 G and 0.074 M, respectively. Furthermore, we introduced the MARI module to enable deeper processing of the extracted features. Although the computational cost increased by 0.406 G, the average recognition accuracy improved by 1.1%. As shown in Fig. 14c, the clustering performance of the model was significantly enhanced, with increased inter-class distances and clearer distributions between different samples. However, some samples still failed to cluster correctly, indicating that the MARI modules capability for complex feature extraction remains to be improved. Finally, we incorporated dense connections into the model by integrating multi-scale information from the Ghost module and global information from CLSHSA into the MARI module, thereby enhancing the models ability to handle complex feature extraction. The experimental results demonstrated that the DLVTNet model with dense connections achieved an average classification accuracy of 98.48% during training while maintaining low computational cost and parameter count (0.493 G and 1.054 M, respectively). As shown in Fig. 14d, all tested samples were clustered into their correct categories, with distinct inter-class distances.

Figure 15 compares the accuracy and loss curves of DLVTNet models employing different methods in the ablation experiments. As shown in Fig. 15a, the accuracy curve of the DLVTNet model using the proposed innovative methods demonstrates a significant advantage over models using incomplete methods. Among the six methods, the accuracy curve of the model using the original dataset (blue) showed the slowest improvement, with a maximum accuracy of only 94.12%, lower than that of the model using the FastGAN-enhanced dataset (97.62%). The introduction of the Ghost and CLSHSA methods, represented by the green and brown curves in Fig. 15a, respectively, improved the convergence speed of the accuracy curves. After introducing the MARI module, the maximum recognition accuracy reached 99.50%, as shown by the orange curve in Fig. 15a, with notably faster convergence during the early stages of model training. Finally, the DLVTNet model with dense connections achieved a maximum recognition accuracy of 99.79%, as shown by the pink curve in Fig. 15a, with the fastest convergence speed among all six methods. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 15b, the loss value curves of the six methods indicate that the complete DLVTNet model exhibits the fastest convergence. Finally, we also output the feature maps of different modules at different stages in the ablation experiment to compare the feature extraction effects. It can be clearly observed from Fig. 16 that as the modules are added, the model pays more attention to the defect position in the upper-left corner. In the feature map of Fig. 16f, the features of the defect area in the upper-left corner are significantly different from those in other positions. This verifies our assumption about the model, that is, the LVT Block and MARI Block are used to obtain the multi-scale information, tiny defect information, and important defect positions of the image respectively, and the method of densely connecting and splicing information at each level effectively helps the model to cluster different samples, which has achieved remarkable results in the grape leaf disease dataset.

Comparative experiments with different attention mechanisms

This paper proposes a deep learning network model DLVTNet that combines CNN and Transformer. In this model, MELA is used as the last layer of the dense connection block to extract regions of interest from the input image. To verify the performance of the MELA attention mechanism, this section compares it with five mainstream and new attention mechanisms: ECA65, CBAM66, GAM67, NAM68, and ELA69. The experimental data obtained are shown in Table 5. Among them, ours has the highest average recognition accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 score, which are 98.48%, 98.48%, 98.47%, and 98.46, respectively, about 0.63%, 0.33%, 1.98%, 0.31%, and 0.47% higher than the average accuracy of the other five attention mechanisms. The accuracy change curves of the six attention mechanisms are shown in Fig. 17, where the MELA attention mechanism can effectively improve the recognition accuracy of the model, with its highest accuracy reaching 99.79%, surpassing other mainstream attention mechanisms.

In addition, this study also visualizes the regions of interest in disease images for different attention mechanisms, and the results are shown in Fig. 18. It can be observed that using the MELA attention mechanism can effectively capture the leaf disease areas, with the best focus on disease areas among the six attention mechanisms. Furthermore, ECA, CBAM, and NAM attention mechanisms can also capture regions of interest, but their focus areas are relatively scattered and fail to accurately focus on the disease areas in the leaves, with more useless areas. Among the six attention mechanisms, GAM has the lowest accuracy, and its class activation map also has the worst effect on focusing on disease areas, failing to effectively localize diseases. This problem is mainly because our attention mechanism introduces a multi-scale information processing branch, which effectively combines the original processing of data in the x and y directions within the image (as shown in Fig. 10). This method can effectively process the feature image. The ECA attention mechanism mainly focuses on the channel information of the image and ignores the most important free disease distribution in agricultural leaf diseases. As shown in Fig. 18a, it fails to effectively focus on the main disease distribution area within the sample. In contrast, although the GAM attention mechanism improves the accuracy at any cost through feature interaction, in the detection of agricultural leaf diseases, the multiple information interaction affects the retention of key information in the model. As shown in Fig. 18c, its focus is far from the disease area.

Category activation diagram of DLVTNet using different attention mechanisms. Mechanisms of attention in Table 5 are from (a) to (e), respectively. Each of the three rows represents a different disease category.

Comparison experiments with different datasets

The method proposed in this paper demonstrates effective detection performance for grape leaf disease recognition and detection. However, using only a single type of leaf disease makes it difficult to prove the generalization capability of the DLVTNet model. To address this, this section tests the DLVTNet model across datasets using tomato leaf disease images from the publicly available New Plant Diseases Dataset (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/vipoooool/new-plant-diseases-dataset). Different categories of tomato image samples are shown in Fig. 19. This dataset includes 10 types of leaf categories, with a total of 18,345 images. The training and test set splits are shown in Table 6.

To compare with existing mainstream models, this section’s experiments used models consistent with those in the comparative experiments of Part 3.3. These models include CNN models such as ConvNext, EfficientNet, MobileNet, ResNet, DenseNet, and InceptionNext, as well as Transformer models including Deit, EfficientFormer, MobileVit, Swin Transformer, TinyVit, and the DLVTNet proposed in this paper, totaling 12 network models. Table 7 presents the evaluation parameters for the 12 models trained on the tomato leaf dataset. Models with an average recognition accuracy exceeding 97% include Deit, EfficientFormer, ResNet, DenseNet, and DLVTNet. Among these, DenseNet and DLVTNet models have an average recognition accuracy above 98%, with DLVTNet achieving the highest average evaluation parameters among the 12 models, specifically 98.57%, 98.74%, 98.57%, and 98.55%.

Figure 20 shows the accuracy curves for the 12 network models tested. Figure 20a compares the accuracy curves of DLVTNet and CNN models. It shows that the accuracy curves of DLVTNet and ConvNext models experienced significant fluctuations in the early stages of training, but DLVTNet was able to converge to a higher level of accuracy. Figure 20b compares the accuracy curves of the DLVTNet model with Transformer models. Most models, except for TinyVit and MobileVit, experienced significant fluctuations, but TinyVit and MobileVit had recognition accuracies much lower than the other models. In the accuracy curve comparison of different network models in Fig. 20, DLVTNet experienced significant fluctuations in the early training stages but exhibited a higher accuracy improvement trend compared to other models, with a peak recognition accuracy of 99.92%, the highest among the 12 neural network models. This indicates that while the DLVTNet model proposed in this paper has some limitations, it still achieves effective recognition of tomato leaf diseases.

Conclusions and discussion

This paper proposes a method for grape leaf disease recognition and detection based on deep learning. This method can effectively identify different types of grape leaf diseases and enhance the richness of data samples First, in response to the problem that existing data augmentation methods struggle to effectively enrich the information in image datasets, the FastGAN generative adversarial network is employed to generate a large number of grape leaf samples. This approach effectively enriches the feature representations of grape leaf diseases at different stages and resolves the issue of data imbalance. On this basis, a lightweight neural network model called DLVTNet is proposed. By combining the Transformer-based LVT module and the CNN-based MARI module, this model effectively fuses the global and local information in images to achieve leaf disease recognition. Specifically, the LVT module innovatively introduces the Ghost module to enhance the image information extraction ability. Moreover, based on the low dependence of K and Q on the number of image channels in the self-attention mechanism, a channel-based local self-attention mechanism (CLSHSA) is proposed. This mechanism realizes a lightweight self-attention mechanism without reducing the model’s recognition ability. Furthermore, the inverted residual module is improved by introducing the MELA attention mechanism. The MELA attention mechanism uses the position information and multi-scale information in the image to obtain weights, thereby enhancing the MARI module’s ability to extract local information. Finally, this paper uses a dense connection method to connect the LVT module and the MARI module, increasing the reuse of image information within the DLVTNet model and further enhancing the model’s recognition ability.

To verify the performance of the DLVTNet model, this study conducted comparative experiments, ablation experiments, and experiments on different attention mechanisms. The experimental results show that through sufficient experimental verification, it can be confirmed that the method of optimizing the expressions of diseases in different cycles through GAN can serve as an effective way to optimize the dataset. It can optimize the sample distribution in the dataset and help the model further learn the differences between different categories to achieve excellent clustering effects. In addition, the proposed DLVTNet can effectively focus on the important defect areas in the model and capture the disease characteristics of free-distributed lesions within the image. At the same time, it realizes the lightweight design of the model. Compared with the existing pure convolutional models, this model has certain advantages, and its size is much smaller than the existing Transformer models, which meets our original design intention. This method can also provide a certain direction for the integration of CNN networks and self-attention mechanisms, and can effectively capture long-range dependencies in actual detection. Finally, we introduced the tomato disease dataset for testing to verify the generalization ability of this method. In the obtained data, our model showed excellent performance. However, the accuracy curves of all the models participating in the experiment fluctuated greatly due to the influence of the dataset, which further confirmed the effect of our dataset optimization. However, there are still certain limitations in our research in this article. Firstly, our dataset is sourced from public dataset samples, without considering the real-world disease situations. Secondly, we used the existing general GAN model to optimize the dataset, and it remains a question whether the optimization effect of the dataset can be further improved. Thirdly, the disease categories we tested are only limited to grapes, and it is unclear whether it can show advantages for a large number of different types of agricultural diseases. Finally, our model does not take the latest research results into account, and there is still room for further optimization of its model structure. In the follow-up, we will conduct in-depth research on the optimization effect of generative models on agricultural leaf diseases, the small differences in leaf characteristics among different categories, the lightweight improvement of the model, and the real-world data distribution problems, aiming to solve the practical problems in agricultural disease detection and realize the practical application of deep learning methods.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mira-de-Orduña, R. Climate change associated effects on grape and wine quality and production. Food Res. Int. 43, 1844–1855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2010.05.001 (2010).

Prathibha, S. R., Hongal, A. & Jyothi, M. P. IOT Based Monitoring System in Smart Agriculture. In 2017 International Conference on Recent Advances in Electronics and Communication Technology (ICRAECT), 81–84, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRAECT.2017.52 (2017).

Burr, T. J., Bazzi, C., Süle, S. & Otten, L. Crown gall of grape: biology of Agrobacterium vitis and the development of disease control strategies. Plant Dis. 82(12), 1288–1297. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.12.1288 (1998).

Zhang, E., Zhang, N., Li, F. & Qi, G. Texture-based Fabric Defect Detection Method. In 2023 7th International Conference on Electrical, Mechanical and Computer Engineering (ICEMCE), 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEMCE60359.2023.10490814 (2023).

Zhanga, Z. et al. Image recognition of maize leaf disease based on GA-SVM. Chem. Eng. Trans. 46, 199–204. https://doi.org/10.3303/CET1546034 (2015).

Tan, A., Zhou, G. & He, M. Surface defect identification of citrus based on KF-2D-Renyi and ABC-SVM. Multimed. Tools Appl. 80, 9109–9136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-020-10036-y (2021).

Bhaldar, H. Novel Algorithm for Detection and Classification of Grape Leaf Disease Using K-Mean Clustering. In 2nd National Conference on Recent Advances in Engineering and Technology (NCRAET_17) (2007).

Phookronghin, K., Srikaew, A., Attakitmongcol, K. & Kumsawat, P. 2 Level Simplified Fuzzy ARTMAP for Grape Leaf Disease System Using Color Imagery and Gray Level Co-Occurrence Matrix. In 2018 International Electrical Engineering Congress (iEECON), 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1109/IEECON.2018.8712183 (2018).

Mohammed, K. K., Darwish, A. A. & Hassenian, A. E. Artificial Intelligent System for Grape Leaf Diseases Classification. In Computer Science, Agricultural and Food Sciences, 19–29, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51920-9_2 (2020).

Adeel, A. et al. Diagnosis and recognition of grape leaf diseases: An automated system based on a novel saliency approach and canonical correlation analysis based multiple features fusion. Sustain. Comput.: Inform. Syst. 24, 100349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suscom.2019.08.002 (2019).

Padol, P. B. & Yadav, A. A. SVM classifier based grape leaf disease detection. In 2016 Conference on Advances in Signal Processing (CASP), 175–179, https://doi.org/10.1109/CASP.2016.7746160 (2016).

Jaisakthi, S. M., Mirunalini, P., Thenmozhi, D. & Vatsala. Grape Leaf Disease Identification using Machine Learning Techniques. In 2019 International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Data Science (ICCIDS), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCIDS.2019.8862084 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Identification of tomato leaf diseases based on combination of ABCK-BWTR and B-ARNet. Comput. Electron. Agric. 178, 105730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105730 (2020).

Goncharov, P., Uzhinskiy, A., Ososkov, G., Nechaevskiy, A. & Zudikhina, J. Deep Siamese networks for plant disease detection. EPJ Web of Conferences https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202022603010 (2020).

Bao, W., Yang, X., Liang, D., Hu, G. & Yang, X. Lightweight convolutional neural network model for field wheat ear disease identification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 189, 106367 (2021).

Atila, Ü., Uçar, M., Akyol, K. & Uçar, E. Plant leaf disease classification using EfficientNet deep learning model. Eco. Inform. 61, 101182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2020.101182 (2021).

Lin, J. et al. GrapeNet: a lightweight convolutional neural network model for identification of grape leaf diseases. Agriculture 12(6), 887 (2022).

Fang, S. et al. Multi-channel feature fusion networks with hard coordinate attention mechanism for maize disease identification under complex backgrounds. Comput. Electron. Agric. 203, 107486 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Huang, S., Zhou, G., Hu, Y. & Li, L. Identification of tomato leaf diseases based on multi-channel automatic orientation recurrent attention network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 205, 107605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2022.107605 (2023).

Sharma, V., Tripathi, A. K. & Mittal, H. DLMC-Net: Deeper lightweight multi-class classification model for plant leaf disease detection. Eco. Inform. 75, 102025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102025 (2023).

Zhao, S., Peng, Y., Liu, J. & Wu, S. Tomato leaf disease diagnosis based on improved convolution neural network by attention module. Agriculture 11, 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11070651 (2021).

Zhao, Y., Sun, C., Xu, X. & Chen, J. RIC-Net: A plant disease classification model based on the fusion of Inception and residual structure and embedded attention mechanism. Comput. Electron. Agric. 193, 106644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106644 (2022).

Zeng, W. & Li, M. Crop leaf disease recognition based on Self-Attention convolutional neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 172, 105341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105341 (2020).

Chen, J., Zhang, D., Zeb, A. & Nanehkaran, Y. Identification of rice plant diseases using lightweight attention networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 169, 114514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114514 (2021).

Ji, M., Zhang, L. & Wu, Q. Automatic grape leaf diseases identification via UnitedModel based on multiple convolutional neural networks. Inf. Process. Agric. 7, 418–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2019.10.003 (2020).

Suo, J. et al. CASM-AMFMNet: A network based on coordinate attention shuffle mechanism and asymmetric multi-scale fusion module for classification of grape leaf diseases. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.846767 (2022).

Liu, B. et al. Grape leaf disease identification using improved deep convolutional neural networks. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.01082 (2020).

Cai, C. et al. Identification of grape leaf diseases based on VN-BWT and Siamese DWOAM-DRNet. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 123, 106341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106341 (2023).

Alsubai, S. et al. Hybrid deep learning with improved Salp swarm optimization based multi-class grape disease classification model. Comput. Electr. Eng. 108, 108733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2023.108733 (2023).

Adeel, A. et al. Entropy-controlled deep features selection framework for grape leaf diseases recognition. Expert Syst. https://doi.org/10.1111/exsy.12569 (2020).

Yuhao, R. & Jinyu, H. Lightweight YOLOv8 for grape leaf lesion detection Proc. SPIE. 133960J https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3050541.

Moonwar, W. et al. Tomato Leaf Disease Classification with Vision Transformer Variants. In Pattern Recognition, 95–107, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47634-1_8 (2023).

Vallabhajosyula, S., Sistla, V. & Kolli, V. K. K. A novel hierarchical framework for plant leaf disease detection using residual vision transformer. Heliyon 10, e29912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29912 (2024).

Waheed, A. et al. An optimized dense convolutional neural network model for disease recognition and classification in corn leaf. Comput. Electron. Agric. 175, 105456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105456 (2020).

Chen, Z., Wang, G., Lv, T. & Zhang, X. Using a hybrid convolutional neural network with a transformer model for tomato leaf disease detection. Agronomy 14, 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14040673 (2024).

Han, D. & Guo, C. Automatic classification of ligneous leaf diseases via hierarchical vision transformer and transfer learning. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1328952 (2024).

Hu, B., Jiang, W., Zeng, J., Cheng, C. & He, L. FOTCA: hybrid transformer-CNN architecture using AFNO for accurate plant leaf disease image recognition. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1231903 (2023).

Li, G., Wang, Y., Zhao, Q., Yuan, P. & Chang, B. PMVT: a lightweight vision transformer for plant disease identification on mobile devices. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1256773 (2023).

Karthik, R. et al. GrapeLeafNet: A dual-track feature fusion network with inception-ResNet and shuffle-transformer for accurate grape leaf disease identification. IEEE Access 12, 19612–19624. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3361044 (2024).

Li, H., Shi, L., Fang, S. & Yin, F. Real-time detection of apple leaf diseases in natural scenes based on YOLOv5. Agriculture 13(4), 878 (2023).

Liu, W. & Zhang, A. Plant disease detection algorithm based on efficient swin transformer. Comput. Mater. Continua 82, 3045–3068. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.058640 (2025).

Zhang, L. et al. JuDifformer: Multimodal fusion model with transformer and diffusion for jujube disease detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 232, 110008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2025.110008 (2025).

Li, W. et al. Grape disease detection using transformer-based integration of vision and environmental sensing. Agronomy 15(4), 831 (2025).

Lu, X. et al. A hybrid model of ghost-convolution enlightened transformer for effective diagnosis of grape leaf disease and pest. J. King Saud Univ. – Comput. Inf. Sci. 34, 1755–1767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2022.03.006 (2022).

Karthik, R. et al. A dual-track feature fusion model utilizing group shuffle residual DeformNet and swin transformer for the classification of grape leaf diseases. Sci. Rep. 14, 14510. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64072-x (2024).

Liu, B., Zhu, Y., Song, K. & Elgammal, A. Towards Faster and Stabilized GAN Training for High-fidelity Few-shot Image Synthesis. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2101.04775 (2021).

Zeng, W., Li, H., Hu, G. & Liang, D. Lightweight dense-scale network (LDSNet) for corn leaf disease identification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 197, 106943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2022.106943 (2022).

Yun, S. & Ro, Y. SHViT: Single-Head Vision Transformer with Memory Efficient Macro Design. ArXiv abs/2401.16456, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.16456 (2024).