Abstract

In vertebrate females, plasma calcium concentrations decrease after the reproductive period to prevent calcium from leaking from the body. Goldfish scales store calcium internally, which is released into the blood by osteoclast resorption. Previously, we found that melatonin increases calcitonin (CT), an osteoclast inhibitor, through melatonin receptors in goldfish scales, and inhibits osteoclast activity. However, the physiological function of the melatonin-dependent suppression of osteoclast activity is unclear. In this study, we found that plasma calcium levels increased during the reproductive stage in female goldfish and decreased during the post-reproductive stage. Histological and mRNA expression analyses of osteoclast marker molecules revealed that osteoclasts in the scales were inactivated during the late and post-reproduction stages when the expression of CT and its receptor increased in female goldfish scales. Moreover, exogenous melatonin suppressed plasma calcium levels in female goldfish during their late reproductive stage in cases of increased melatonin receptor expression. Taken together, these results suggest that melatonin inactivates scale osteoclast resorption by increasing CT levels in the scales and prevents calcium leakage from the body during the late and post-reproductive stages of female goldfish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Seasonal changes have serious consequences for an organism’s survival and species conservation1,2,3. Therefore, organisms maintain their species by limiting their reproductive stages to certain seasons and by adapting to environmental changes4. For example, horses have a gestational period of approximately 1 year, whereas hamsters have a gestation period of a few weeks, and birds experience a short breeding period during spring5,6. They all give birth during spring and summer, and their pups are programmed to develop when provided plenty of food.

Melatonin is a small, amphiphilic, indoleamine molecule that exhibits a variety of biological activities7,8. It was originally considered an endocrine hormone that is primarily synthesized in the pineal gland and released into the blood to interact with melatonin receptors throughout the body9,10. However, melatonin is also produced in small amounts in other tissues and organs, including the brain, retina, intestine, ovary, skin, crystalline lens, and bone11,12. Furthermore, it regulates diverse physiological functions, such as the sleep–wake cycle10,13, circadian clocks14,15, glucose metabolism16,17, immune system activity18, and bone metabolism19,20. In particular, evidence suggests that melatonin acts as a reproduction regulator21,22,23.

Previous studies in quails reported that type 2 deiodinase (Dio2), which is involved in the seasonal reproduction (season-dependent testis development) of males, is induced by the mediobasal hypothalamus of the brain during reproduction24. It converts the low active form of thyroid hormones in the hypothalamus into an active form [i.e., triiodothyronine (T3)], which then promotes testicular development25. Notably, in hamsters exhibiting seasonal reproduction26, Dio2 expression has been reportedly suppressed by daily injections of exogenous melatonin27. The antigonadotrophic effect of melatonin has also been reported in female mammals21. For example, daily injection of melatonin into female rats decreases the incidence of estrus and reduces ovary weight28. In humans, melatonin receptors are expressed in various cell types of the female reproductive tract29,30,31,32,33. Furthermore, clinical and in vitro studies have provided evidence that melatonin inhibits human ovulation34,35,36,37.

Proper control of plasma calcium concentrations is important for numerous physiological functions, such as neurotransmission, muscle contraction, and blood coagulation38,39. In vertebrate females, calcium demands are exacerbated during the reproductive stage. For example, a study using a mouse model with hypocalcemia revealed that calcium deficiency results in a significantly reduced number of oocytes after ovarian stimulation, as well as a reduced ability to mature40. This suggests that serum calcium levels play an important role in determining the number and maturation of oocytes in mammals. In nonmammalian vertebrates, including bony fishes, plasma calcium levels increase exactly at the same time as reproductive development in females41,42,43,44. Conversely, the calcium supply is terminated immediately after reproduction to prevent it from leaving the body. Whether this occurs and how the plasma calcium concentration decreases from the late reproductive to non-reproductive stages is unclear.

Mammalian bone tissue consists of osteoblasts, osteoclasts, osteocytes, and calcified bone matrices45. It stores calcium and is involved in regulating blood calcium levels8. Parafollicular cells in the thyroid gland produce calcitonin (CT)46, a hormone that binds to the CT receptor on osteoclasts and inhibits their activity to reduce the blood calcium level47. In contrast, the parathyroid gland secretes parathyroid hormone (PTH), which promotes osteoclast activity to increase blood calcium levels48.

The regulatory mechanisms for internal calcium are similar between bony fishes and mammals8,49. Freshwater bony fishes, such as goldfish and rainbow trout, store internal calcium in their scales50, which, like mammalian bone, are comprised of osteoblasts, osteoclasts, osteocytes, and calcified bone matrix and are involved in regulating calcium levels in the blood51,52,53. Notably, freshwater bony fishes rely on their internal calcium stores in their scales to increase calcium availability during the reproductive period.

In freshwater bony fish scales, PTH activates osteoclasts54, whereas CT acts as an inhibitor of osteoclastic activity55,56. Previously, we found that melatonin increases CT levels and suppresses osteoclastic resorption in the goldfish scale57,58. Therefore, we hypothesized that melatonin-induced CT-dependent suppression of osteoclast activity in scales may reduce plasma calcium concentrations following reproduction in female goldfish. This study provides evidence supporting our hypothesis, and we propose that the anti-calcium effect of melatonin is required for the efficient transition from the reproductive to non-reproductive stages in these fish.

Results and discussion

The plasma calcium level increases during the reproductive stage in female goldfish and sharply decreases after the reproductive stage

The reproductive stage of goldfish was reported to be from March to May59,60,61. It was also reported that the level of the gonadosomatic index (GSI), an indicator of gonadal development, was low in goldfish around August, demonstrating that August is the non-reproductive stage of goldfish59,60,61. To identify the reproductive stage of female goldfish in our experimental setting and to determine whether blood calcium levels change during the reproductive stage, the GSI and the plasma calcium levels in female goldfish were measured from December to August. Figure 1A displays that the GSI level was highest in March, which was significantly higher than those in December, June, and August, but not when compared with the other months tested. Based on this result, the reproductive stage of female goldfish in our experimental setting was confirmed to occur from January to May. In addition, December was defined as the pre-reproductive stage, and June to August as the post-reproductive stage in our experimental setting.

Seasonal changes in gonadosomatic index (GSI) and plasma calcium levels in female goldfish. GSI (A) and plasma calcium levels (B) of female goldfish were measured from December 2008 to August 2009 (each month n = 10-23). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Abbreviations: Dec, December; Jan, January; Feb, February; Mar, March; Apr, April; Jun, June; Aug, August.

The plasma calcium level was highest in May and sharply decreased thereafter (Fig. 1B). The plasma calcium level in May was significantly higher than those in December, January, June, and August, but not when compared with the other months tested. These results indicate that plasma calcium levels increase during the reproductive stage in female goldfish and decrease at the post-reproductive stage. Consistent with our results here, previous studies showed that plasma calcium, which is required for the formation of yolk proteins62, is elevated in reproductive stage bony fishes43,50. Saltwater fish use calcium transport mechanisms in their gills and gastrointestinal tract to obtain calcium from the environment and regulate plasma calcium levels63,64. Freshwater fish such as goldfish and rainbow trout rely on internal calcium stores in their scales as well as environmental sources to increase calcium availability during the reproductive period65,66. There is also evidence that osteoclasts detected in bony fish scales regulate plasma calcium levels49,67,68. To determine whether scales are involved in elevated plasma calcium during the reproductive stage of female goldfish, we evaluated osteoclast activity in female goldfish scales during and after the reproductive stage, as described below.

Osteoclasts in the scales of the female goldfish are activated during the reproductive stage

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) is the characteristic marker of osteoclast activity69. We first examined whether the osteoclastic activities in the female goldfish scales are higher in the reproductive stage (January to April) than in the post-reproductive stage (June) by TRAP staining assay. Consistent with a previous study54, TRAP was detected in the scales of female goldfish (Fig.2A). Ratios of scales expressing TRAP in female goldfish were determined from January to August (Fig. 2B). The ratio at the late reproductive stage (April) was significantly higher than that at the early reproductive stage (January). Then, the ratios of TRAP-negative scales in the female goldfish were determined. The ratio at the post-reproductive stage (June) was significantly higher than those at the reproductive stage (February and April).

Seasonal changes in osteoclast activity in female goldfish scales. (A) Representative samples of goldfish scale expressing tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) (left panel) and the TRAP negative scale (right panel); white arrows indicate TRAP-stain-positive area. (B) Ratios of TRAP-positive scales in female goldfish (left graph) and the ratios of TRAP-negative scales in female goldfish (right panel) from January 2009 to August 2009 (each month n = 4-6; 200 scales were analyzed for each individual). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). (C) Expression levels of genes involved in osteoclast activation were examined in female goldfish scales from December 2008 to August 2009 [for cathepsin K (cathK) and receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ ligand (rankl)] or June 2009 [for vacuolar- ATPase subunit d2 (V-ATPase)] (each month n = 8 for each gene examined). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Average expression levels in December (Dec) were set to 1. Abbreviations: Dec, December; Jan, January; Feb, February; Mar, March; Apr, April; Jun, June; Aug, August.

Next, the gene expression levels involved in the osteoclast activation, such as cathepsin K (cathK)70, Vacuolar-ATPase subunit d2 (V-ATPase)71, and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (rankl)72, were examined in the scales of female goldfish before (December), during (from January to May), and after (June and/or August) the reproductive stage (Fig. 2C). The cathK expression during the late reproductive stage (April) was significantly higher than that in other months tested. Additionally, cathK expression during the reproductive stage (January to April) was significantly higher than during the pre-reproduction stage (December). V-ATPase expression during the mid-reproductive stage (March) was significantly higher than during the pre- and post-reproductive stages. Furthermore, V-ATPase expression during the early reproductive stage (January to March) was significantly higher than during the post-reproductive stage. Rankl expression during the reproductive stage (January to April) was significantly higher than that of the pre-reproductive stage. Furthermore, the rankl expression at the part of the reproductive stage (January and April) was significantly higher than that of the post-reproduction stage (June). Overall, our results reveal that osteoclasts in female goldfish scales are activated during the reproductive stage, and further, this activation is suppressed during the final part of the stage. The activated osteoclasts in the scales are speculated to contribute to increased plasma calcium levels49,60, which is required for the formation of the egg yolk protein in female individuals during the reproduction stage73,74.

17β-estradiol (E2) is a female-dominant sex hormone that plays a critical role in reproduction and sexual differentiation in vertebrates75,76. Studies have shown that E2 receptor is expressed in scale osteoclasts of sea bream (Sparus auratus) and Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus)77, and that E2 increases the osteoclast activity in rainbow trout scales68. E2 receptor has also been shown to be expressed in goldfish scales78. Additionally, plasma E2 concentrations have been shown to increase during the reproductive stage in female goldfish59. Based on these findings, we tested whether E2 activates osteoclasts in female goldfish scales, as described below.

Plasma E2 level in female goldfish increases during the reproductive stage, and exogenous E2 promotes expression of gene involved in osteoclast activation

We compared plasma E2 levels during and after the reproductive period. As shown in Fig. 3A, the E2 level in late March (March 24th) was significantly higher than that in early March (March 8th). It was also significantly higher than those of late and post-reproduction stages. On the other hand, the E2 level in late March (March 24th) was not significantly different from those of April. Although the number of goldfish used in this measurement was small (n=3-5 at each point), these results are consistent with a previous study, which showed elevated plasma E2 levels during the reproductive period in female goldfish59.

Changes in plasma 17β-estradiol (E2) levels in female goldfish and effects of exogenous E2 on expression of osteoclastic gene in the scales of female goldfish. (A) Plasma E2 levels of female goldfish were measured from March 2016 to June 2016 (each month, n = 3-6). Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). (B) mRNA expression of cathepsin K (cathK) in the scales of goldfish without (CNT) and with injection of E2 (E2). The female goldfish were injected intraperitoneally with 4 μg/g body weight of exogenous E2 in October 2016. *P < 0.05 indicates a significant difference vs. control.

In October, during the non-reproductive stage, exogenous E2 (4 μg/g of body weight) was injected intraperitoneally into female goldfish. Expression of the gene involved in osteoclast activation, cathK70, was determined in the scales. As shown in Fig. 3B, exogenous E2 significantly increased the expression of cathK in the scales, evidence that E2 increases osteoclast activity in goldfish scales. It is important to note that the number of goldfish used in this measurement was small (4 in the control group and 3 in the E2-administered group). Our results are consistent with those of previous studies where E2 treatment increased scale osteoclastic activity and decreased scale calcium content, indicating an E2-mediated increase of scale resorption in rainbow trout66,68. In freshwater bony fishes, including goldfish65, killifish65, and rainbow trout66,67,68, the increased demand for calcium during the reproductive stage is met through mobilization of internal calcium stores, predominantly from the scales, so bone is initially preserved. E2 treatment has been shown to decrease pharyngeal bone resorption in rainbow trout66, consistent with E2’s physiological role in mammals and birds, where E2 decreases bone resorption79,80. It appears that in freshwater teleosts, E2 promotes scale resorption and supplies calcium to protect the skeleton during the reproductive stage.

mRNA expression of calcitonin (CT) and its receptor (CTR) in the scales of female goldfish increases during the late and post-reproductive stages

CT binds to CTR on osteoclasts and inhibits their activity, reducing the amount of calcium that enters the bloodstream8. In addition, osteoblast lineage cells produce CT, which inhibits the activity of osteoclasts in scales of bony fish, including goldfish57,58. To examine whether CT is involved in the decreased osteoclast activity in the scales of female goldfish during the late and post-reproductive stages, the mRNA expression of CT and CTR was determined from female goldfish scales during the reproductive (March to May) and post-reproductive (June) stages. As shown in Fig. 4, the mRNA expression of CT was highest at late April (April 25th), and this was significantly higher than that at late March (March 24th) and early April (April 11th). In addition, the mRNA expression of CTR at late April (April 25th) and early May (May 9th) was significantly higher than that in March (March 8th and 24th) and early April (April 11th). These mRNA expression profiles of CT and CTR support the idea that CT function in goldfish scales increases during the late and post-reproductive stages, which could decrease goldfish scale osteoclast activity and plasma calcium levels in female goldfish.

mRNA expression of the melatonin receptor Mel1a1.4 in the scales of female goldfish increases during the late reproductive and post-reproductive stages

In a previous study, we found that melatonin treatment increases CT expression and suppresses osteoclast activity in cultured goldfish scales58, suggesting that melatonin may play a role in reducing the scales’ osteoclast activity and the plasma calcium level in female goldfish during the late reproductive stage. To test this idea, melatonin levels were measured during (March to May) and after (June) the reproduction stage. As melatonin levels have been known to change during day and night9,81, they were separately measured at different times of the day and night. As shown in Fig. 5A, melatonin levels were higher at night than during the day. Furthermore, melatonin levels both at daytime and nighttime were unchanged during and after the reproduction stage. Accordingly, in the current study, plasma melatonin levels did not correlate with reproductive activity in female goldfish. It is important to note that the number of goldfish used in this measurement was small (n=4 at each point).

Seasonal changes in plasma melatonin levels and melatonin receptor Mel1a 1.4 (mel1a 1.4) expression levels of female goldfish scales. (A) Plasma melatonin levels in goldfish at midnight (closed circle, each time point n = 4) and at midday (open circle, each time point n = 4) from March 2016 to June 2016. (B) mRNA expression levels of mel1a 1.4 of goldfish scales at midnight (upper graph; each time point n = 6) and at midday (lower graph; each time point n = 6) from March 2016 to June 2016. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). The average expression on March 8 was set to 1.

Melatonin shows its effects by binding to melatonin receptors in the plasma membrane to activate the intracellular signaling pathways82,83. In addition, our previous study reported that melatonin acts on osteoblast lineage cells by binding to melatonin receptors, which promotes CT production in goldfish scales58. Accordingly, the melatonin receptor mel1a1.4 expression levels in the scales of female goldfish were determined during and after the reproduction stage. As shown in Fig. 5B, nighttime mel1a1.4 expression levels reached their peak during the late reproductive stage [from late April (April 25th) to early May (May 9th)]. These levels were significantly higher than during the middle reproduction stage [from early March (March 8th) to early April (April 11th)]. In addition, daytime mel1a1.4 expression level was highest at late April (April 25th). The mel1a1.4 expression level at late April (April 25th) was significantly higher than that in early March (March 8th), but not when compared with the other time points tested. In particular, the nighttime mel1a1.4 expression level supports the idea that melatonin suppresses osteoclast activity in the scales to reduce plasma calcium levels in female goldfish during the late part of the reproductive stage. The expression of melatonin receptors during reproduction has been enhanced in organisms other than goldfish. For example, the mRNA levels of the melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2 in the developing ovarian follicles of mares were higher during the reproductive than during the non-reproductive periods84. The mRNA levels of two of the three melatonin receptors in turbots, a flatfish species, were also elevated in the female gonads during the late reproductive stage85. A similar seasonal regulation of melatonin receptor expression was also observed in the testes of birds86. These findings suggest that the seasonal regulation of physiological functions’ response to melatonin is driven by reproduction-related changes in melatonin receptor expression.

Exogenous melatonin suppresses plasma calcium levels in female goldfish during the late reproductive stage

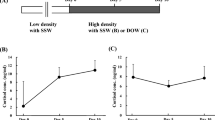

To gather further evidence of the role of melatonin in the regulation of plasma calcium levels in female goldfish during the reproductive stage, the effects of intraperitoneally administered exogenous melatonin on plasma calcium levels in female goldfish were measured (Fig. 6A). Various melatonin doses were intraperitoneally injected into female goldfish during the late reproductive stage. Plasma calcium levels were then measured in melatonin-treated goldfish. High-dose melatonin (10 μg/g of body weight) suppressed plasma calcium levels, whereas low-dose melatonin (0.1 μg and 1 μg/g of body weight) did not. Previous studies have used high exogenous melatonin concentrations to demonstrate its remarkable effects on physiological processes, including bone metabolism in rats87, hypnotic effects on humans88,89, and human fertilization90,91. Next, the effects of intraperitoneally administered exogenous melatonin on plasma calcium levels in female goldfish were measured at various time points during the reproduction stage (Fig. 6B). Exogenous melatonin significantly suppressed plasma calcium levels when administered during the late reproductive stage (April). Conversely, exogenous melatonin did not affect plasma calcium levels when administered at the early reproductive stage (February). Previously, we found that melatonin increases CT levels, an inhibitor of osteoclastic resorption55,56, in goldfish scales57,58. Thus, the suppression of plasma calcium concentration by exogenous melatonin may be mediated by the CT-dependent suppression of osteoclast activity in scales. In addition, mel1a1.4 expression at night in female goldfish scales was higher during the late reproductive stage (April) compared with the mid-reproductive stage (March) (Fig. 5B). The upregulation of mel1a1.4 expression was induced during the late reproductive stage, which suggests a mechanism for the period-dependent suppressive effect of melatonin on plasma calcium levels in female goldfish (Fig. 6B).

Effects of melatonin on plasma calcium levels in female goldfish. (A) Effects of different doses (0.1 μg, 1 μg, and 10 μg/g body weight) of exogenous melatonin on plasma calcium levels in female goldfish were evaluated at midnight (n = 9 or 10) in April 2010. The horizontal axis in the graph depicts the time (hours) after exogenous melatonin administration. Value at time point 0 was set as 100% for each result of the melatonin doses. *P < 0.05 indicates significant difference vs. control at 24 h after melatonin (10 μg/g body weight) injection. Close circle, control group; close triangle, 0.1 μg/g body weight melatonin-administered group; open triangle, 1 μg/g body weight melatonin-administered group; and open circle, 10 μg/g body weight melatonin-administered group. (B) Effects of exogenous melatonin (10 μg/g body weight) on plasma calcium levels in female goldfish were evaluated (each time point n = 8-12) in April 2009 (left graph) and February 2009 (right graph). The horizontal axis in each graph shows the time (hours) after exogenous melatonin administration. The value at time point 0 was set as 100% for each graph. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 indicate significant differences vs. control at each time point. Close circle: control groups, open circle: melatonin-administrated groups.

In freshwater bony fish, such as goldfish and rainbow trout, E2 increased osteoclastic activity in the scales and released calcium stored in the scales into the blood to increase its availability during the reproductive period49,67,68. The plasma E2 levels were enhanced during reproduction in female goldfish (Fig. 3A). In addition, exogenous E2 injection increased the expression of cathK, which is involved in osteoclast activation in female goldfish scales70 (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that scales contribute to the plasma calcium supply during reproduction in female goldfish. We also found that plasma calcium levels decreased during the post-reproductive stage. Previously, we reported that melatonin acts on osteoblast lineage cells by binding to melatonin receptors and promoting CT production, an inhibitor of osteoclast resorption55,56, in goldfish scales57,58 (Fig. 7). We propose that the melatonin-induced CT-dependent suppression of osteoclast activity in scales contributes to a decrease in plasma calcium levels after reproduction in female goldfish, based on the following findings (Fig. 7). First, osteoclast marker expression in the scales decreased during the late and post-reproductive stages in female goldfish (Fig. 2). Second, the expression of CT and CTR in female goldfish scales increased during the late and post-reproductive stages (Fig. 4). Third, the expression of the melatonin receptor mel1a1.4 in female goldfish scales increased during the late reproductive and post-reproductive stages (Fig. 5B). Finally, exogenous melatonin suppressed plasma calcium levels in female goldfish during the late reproductive stage in cases of increased melatonin receptor expression (Fig. 6). Because calcium is needed for eggshell protein formation in fish73,74, the melatonin-mediated decrease in plasma calcium levels could halt the reproduction stage, potentially preventing calcium excretion from the body.

Methods

Ethical treatment of animals

This study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations in the ethical guidelines of Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU). All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of TMDU (permit number: 0170339 A). Additionally, the protocols were in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.092. All experiments were performed in a manner that minimized pain and discomfort.

Goldfish

Female goldfish (Carassius auratus) were purchased from Higashikawa Fish Farm (Yamatokoriyama, Japan). The origin of the female goldfish used in the current study was of the Wakin variety (Japanese goldfish). All of the fish were bred for generations in the Higashikawa Fish Farm and had typical Wakin characteristics, which are the closest to the original goldfish species, with a carp-like tail, carp-like shape, and red body color. The mean and standard error for the weight of the goldfish used in this study were 41.85 ± 1.24 g.

Goldfish were maintained under outdoor conditions during experimental periods (described in each figure) at an open site on the rooftop of the third building of College of Liberal Arts and Sciences of the TMDU, Ichikawa. Here, seasonal changes in the gonadosomatic index (GSI), plasma calcium concentrations, and scale osteoclast activity were examined.

Determination of the GSI

Goldfish were weighted and sacrificed with benzocaine (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Ovaries were collected and weighed. Based on these measurements, the GSI, i.e., the ovarian (gonad)-to-body weight ratio (gonad weight/body weight × 100) was calculated. The number of goldfish used in this analysis was 20 in December, 16 in January, February, March, and April, 23 in May, 14 in June, and 10 in August.

Measurement of plasma calcium, E2, and melatonin concentrations

To collect plasma, goldfish were first anesthetized with benzocaine, and whole blood was collected from the caudal vein using a 1-mL heparinized syringe with a 21-G needle (Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Plasma samples were obtained after blood centrifugation at 1000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and then stored at −80°C to measure the plasma calcium or melatonin concentration.

Plasma calcium concentrations were measured using the Calcium E Test Wako (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The number of goldfish used in this measurement was 20 in December, 16 in January, February, March, and April, 23 in May, 14 in June, and 10 in August.

Plasma E2 concentrations were measured using the estradiol enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The number of goldfish used in this measurement was 4 on March 8th, 6 on March 24th, April 11th, April 25th, May 9th and June 2nd, 5 on May 23rd, and 3 on June 20th.

For the measurement of plasma melatonin concentration, four times the volume of acetone was added to the goldfish plasma and stirred 10 min using a vortex mixer, followed by centrifugation at 20,800 × g for 10 min. Supernatants were then transferred into clean test tubes and dried at 65 °C under a stream of nitrogen gas. After dissolving residues into 100-µL of Milli-Q water, mixtures were filtered through 0.22 μm-pore filters (Centrifugal Filter Units Ultrafree-MC-GV 0.22 μm, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and stored at −80°C until liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis. The number of goldfish used in this measurement was 4 for each time point.

For the LC-MS/MS analysis of melatonin, 10 µL samples were injected into an HPLC system (AC30AD, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a C18 2.0 × 150-mm, 3 µm Kinetex column (Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan). The mobile phase comprised 10 µM ammonium acetate in 0.05% (v/v) acetic acid with varying MeOH concentrations. The linear gradient was run for over 20 min from 5% to 50% and then maintained at 100% MeOH for 10 min. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min, and the auto sampler and column oven were maintained at 4 °C and 25 °C, respectively. Melatonin was detected using a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC-MS-8050, Shimadzu) and quantified using the multiple reaction monitoring method with transitions of parent ions to product ions. The transition for melatonin was m/z 233.0–130.0. The limit of sensitivity for melatonin was 11.1 fg for a 2:1 signal-to-noise ratio. Intra- and inter-assay variation coefficients were 3.94% and 4.60%, respectively.

Evaluation of the effect of exogenous melatonin on plasma calcium levels in female goldfish

Sexually mature female goldfish were anesthetized with benzocaine and intraperitoneally injected with melatonin (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.) in February or April. Melatonin was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Industries). Goldfish were kept continuously under outdoor conditions. Their plasma calcium levels were determined at 12 and 24 h after the injection of melatonin, as described in the previous section. The number of goldfish used in the evaluation in Fig. 6A was 9 for the control group and 0.1 μg/g body weight melatonin-administered group, 10 for 1 μg/g body weight melatonin-administered group and 10 μg/g body weight melatonin-administered group. The number of goldfish used in the February 2009 evaluation in Fig. 6B was 12 in the control group and 11 in the melatonin-administered group, respectively. The number of goldfish used in the April 2009 evaluation in Fig. 6B was 8 for each of the control and melatonin-administered groups.

Evaluation of the effect of exogenous E2 on osteoclastic gene expression in female goldfish scales

Sexually mature goldfish were maintained under outdoor conditions prior to the experiment. They were then acclimated for 1 week under indoor conditions with a 12L:12D photoperiod and a controlled temperature of 26 °C ± 1°C. The female goldfish were anesthetized with benzocaine and injected intraperitoneally with 4 μg/g body weight of E2 (Sigma-Aldrich). Osteoclastic gene expression in the scales was analyzed with RT-PCR at 3 days after injection of E2. The number of goldfish used in the evaluation was 4 in the control group and 3 in the E2-administered group.

Histological observations of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity in goldfish scales

Two hundred scales on the right side of the body were collected from each fish and then fixed in 10% formaldehyde in a 0.05 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Simultaneously, eight scales on the left side of the body of each fish were collected in ISOGEN (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis, as described in the next section.

The scales were stained to check for the presence of TRAP using a commercial acid phosphatase leukocyte kit (Sigma-Aldrich). The scales were washed using distilled water and incubated with TRAP-staining solution for 1 h at 37 °C under dark conditions. The assay components comprised naphthol AS-BI phosphate solution, diazotized fast garnet GBC base solution, sodium nitrite solution, acetate solution (pH 5.2), and 10 mM of L(+)-tartrate solution.

The scales were examined under two different conditions based on TRAP staining and scale erosion level: TRAP-stained negative and TRAP-stained positive scales. The former group was characterized by the total absence of TRAP staining points inside the scale, whereas the latter group was stained inside the scale and absorbed over five ridges (incremental line of scale) by the osteoclasts. The numbers of TRAP-stained negative and TRAP-stained positive scales were counted, and the proportion of each scale was determined. The number of goldfish used in the histological observations was 6 in January, February, March, April, and June, and 4 in August.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from goldfish scales using ISOGEN (Nippon Gene) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, the total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan). Each quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the MX3000 P ® QPCR System (Agilent, Tokyo, Japan). For a 10 μL PCR reaction, 1-μL containing the cDNA template was combined with 9 μL of the SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM (Takara) and mixed with appropriate primers to a final concentration of 200 nM. The reaction mixture was incubated at 90 °C for 10 s, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s and at 60 °C for 40 s. β-actin was used for normalization. PCR primer sequences used in the current study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The number of goldfish used in the RT-PCR at each time point was 8 for cathk, V-ATPase, and rankl and 6 for ct, ctr, and mel1a1.4.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as means ± standard errors. Means of more than two groups were compared using analysis of variance. Multiple comparisons were evaluated with Tukey’s honestly significant difference tests. Differences between the two groups were assessed with a Student’s t-test. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Data that support the study findings are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Parmesan, C. Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 37, 637–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100 (2006).

Falvo, C. A., Koons, D. N. & Aubry, L. M. Seasonal climate effects on the survival of a hibernating mammal. Ecol. Evol. 9, 3756–3769. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.5000 (2019).

Chen, J., Okimura, K. & Yoshimura, T. Light and hormones in seasonal regulation of reproduction and mood. Endocrinology 161, bqaa130. https://doi.org/10.1210/endocr/bqaa130 (2020).

Nakane, Y. & Yoshimura, T. Universality and diversity in the signal transduction pathway that regulates seasonal reproduction in vertebrates. Front. Neurosci. 8, 115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2014.00115 (2014).

Karsch, F. J. et al. Neuroendocrine basis of seasonal reproduction. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 40, 185–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-571140-1.50010-4 (1984).

Nakayama, T. & Yoshimura, T. Seasonal Rhythms: The role of Thyrotropin and Thyroid Hormones. Thyroid 28, 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2017.0186 (2018).

Ramis, M. R., Esteban, S., Miralles, A., Tan, D. X. & Reiter, R. J. Protective effects of melatonin and mitochondria-targeted antioxidants against oxidative stress: A review. Curr. Med. Chem. 22, 2690–2711. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867322666150619104143 (2015).

Hirayama, J. et al. Physiological consequences of space flight, including abnormal bone metabolism, space radiation injury, and circadian clock dysregulation: Implications of melatonin use and regulation as a countermeasure. J. Pineal Res. 74, e12834. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12834 (2023).

Reiter, R. J. Melatonin: the chemical expression of darkness. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 79, C153-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/0303-7207(91)90087-9 (1991).

Reiter, R. J., Tan, D. X. & Galano, A. Melatonin: exceeding expectations. Physiology (Bethesda). 29, 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.00011.2014 (2014).

Acuña-Castroviejo, D. et al. Extrapineal melatonin: Sources, regulation, and potential functions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 2997–3025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-014-1579-2 (2014).

Luchetti, F. et al. Melatonin regulates mesenchymal stem cell differentiation: A review. J. Pineal Res. 56, 382–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12133 (2014).

Bedrosian, T. A., Fonken, L. K. & Nelson, R. J. Endocrine effects of circadian disruption. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 78, 109–131. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105102 (2016).

Cajochen, C., Kräuchi, K. & Wirz-Justice, A. Role of melatonin in the regulation of human circadian rhythms and sleep. J. Neuroendocrinol. 15, 432–437. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.00989.x (2003).

Zisapel, N. New perspectives on the role of melatonin in human sleep, circadian rhythms and their regulation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175, 3190–3199. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14116 (2018).

Peschke, E. et al. Diabetic Goto Kakizaki rats as well as type 2 diabetic patients show a decreased diurnal serum melatonin level and an increased pancreatic melatonin-receptor status. J. Pineal Res. 40, 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00287.x (2006).

Peschke, E. Melatonin, endocrine pancreas and diabetes. J. Pineal Res. 44, 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00519.x (2008).

Xia, Y. et al. Melatonin in macrophage biology: Current understanding and future perspectives. J. Pineal Res. 66, e12547. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12547 (2019).

Maria, S. et al. Biological effects of melatonin on osteoblast/osteoclast cocultures, bone, and quality of life: Implications of a role for MT2 melatonin receptors, MEK1/2, and MEK5 in melatonin-mediated osteoblastogenesis. J. Pineal Res. 64, 1111/jpi.12465 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12465

Munmun, F. & Witt-Enderby, P. A. Melatonin effects on bone: Implications for use as a therapy for managing bone loss. J. Pineal Res. 71, e12749. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12749 (2021).

Olcese, J. M. Melatonin and Female Reproduction: An Expanding Universe. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 85. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00085 (2020).

Méndez, N. et al. From gestational chronodisruption to noncommunicable diseases: Pathophysiological mechanisms of programming of adult diseases, and the potential therapeutic role of melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 75, e12908. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12908 (2023).

Hazlerigg, D. G., Simonneaux, V. & Dardente, H. Melatonin and seasonal synchrony in mammals. J. Pineal Res. 76, e12996. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12996 (2024).

Yoshimura, T. et al. Light-induced hormone conversion of T4 to T3 regulates photoperiodic response of gonads in birds. Nature 426, 178–181. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02117 (2003).

Yasuo, S. et al. The reciprocal switching of two thyroid hormone-activating and -inactivating enzyme genes is involved in the photoperiodic gonadal response of Japanese quail. Endocrinology 146, 2551–2554. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2005-0057 (2005).

O’Jile, J. R. & Bartness, T. J. Effects of thyroxine on the photoperiodic control of energy balance and reproductive status in Siberian hamsters. Physiol. Behav. 52, 267–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9384(92)90269-8 (1992).

Watanabe, M. et al. Photoperiodic regulation of type 2 deiodinase gene in Djungarian hamster: possible homologies between avian and mammalian photoperiodic regulation of reproduction. Endocrinology 145, 1546–1549. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2003-1593 (2004).

Wurtman, R. J., Axelrod, J. & Chu, E. W. Melatonin, a pineal substance: effect on the rat ovary. Science 141, 277–278. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.141.3577.277 (1963).

Niles, L. P., Wang, J., Shen, L., Lobb, D. K. & Younglai, E. V. Melatonin receptor mRNA expression in human granulosa cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 156, 107–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00135-5 (1999).

Woo, M. M. Direct action of melatonin in human granulosa-luteal cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 4789–4797. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.86.10.7912 (2001).

Schlabritz-Loutsevitch, N., Hellner, N., Middendorf, R., Müller, D. & Olcese, J. The human myometrium as a target for melatonin. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 908–913. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2002-020449 (2003).

Lanoix, D., Beghdadi, H., Lafond, J. & Vaillancourt, C. Human placental trophoblasts synthesize melatonin and express its receptors. J. Pineal Res. 45, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00555.x (2008).

Sharkey, J. T., Puttaramu, R., Word, R. A. & Olcese, J. Melatonin synergizes with oxytocin to enhance contractility of human myometrial smooth muscle cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94, 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2008-1723 (2009).

Brzezinski, A., Seibel, M. M., Lynch, H. J., Deng, M. H. & Wurtman, R. J. Melatonin in human preovulatory follicular fluid. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 64, 865–867. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-64-4-865 (1987).

Voordouw, B. C. et al. Melatonin and melatonin-progestin combinations alter pituitary-ovarian function in women and can inhibit ovulation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 74, 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.74.1.1727807 (1992).

Nakamura, Y., Tamura, H., Takayama, H. & Kato, H. Increased endogenous level of melatonin in preovulatory human follicles does not directly influence progesterone production. Fertil. Steril. 80, 1012–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(03)01008-2 (2003).

Scarinci, E. et al. “Hormone of darkness” and human reproductive process: direct regulatory role of melatonin in human corpus luteum. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 42, 1191–1197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-019-01036-337 (2019).

Tinawi, M. Disorders of Calcium Metabolism: Hypocalcemia and Hypercalcemia. Cureus. 13, e12420. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.12420 (2021).

Arora, N. & Koirala, A. Calcium, Magnesium and Phosphate Disorders. Adv Kidney Dis Health. 32, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.akdh.2024.10.007 (2025).

Safari, H., Hajian, M., Nasr-Esfahani, M. H., Forouzanfar, M. & Drevet, J. R. Vitamin D and calcium, together and separately, play roles in female reproductive performance. Sci. Rep. 12, 10470. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14708-7 (2022).

Björnsson, B. T., Haux, C., Förlin, L. & Deftos, L. J. The involvement of calcitonin in the reproductive physiology of the rainbow trout. J. Endocrinol. 108, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.0.1080017 (1986).

Norberg, B. et al. Changes in plasma vitellogenin, sex steroids, calcitonin, and thyroid hormones related to sexual maturation in female brown trout (Salmo trutta). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 75, 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-6480(89)90085-3 (1989).

Allen, P. J. et al. Calcium regulation in wild populations of a freshwater cartilaginous fish, the lake sturgeon Acipenser fulvescens. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 154, 437-450 (2009) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.07.014

Takagi, T. et al. Development of a system for measuring calcitonin in the stingray Dasyatis akajei (a cartilaginous fish): the possible involvement of stingray calcitonin in gonadal development. Int. Aquat. Res. 11, 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40071-019-00236-0 (2019).

Florencio-Silva, R., Sasso, G. R., Sasso-Cerri, E., Simões, M. J. & Cerri, P. S. Biology of Bone Tissue: Structure, Function, and Factors That Influence Bone Cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 421746. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/421746 (2015).

Allen, E. & Fingeret, A. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Thyroid. StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC. (2023) PMID: 29262169

Sexton, P. M., Findlay, D. M. & Martin, T. J. Calcitonin. Curr Med Chem. 6, 1067–1093 (1999) (PMID: 10519914).

Khan M, Jose A, Sharma S. Physiology, Parathyroid Hormone (PTH). StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC. PMID: 29763115 (2023).

Kuroda, K. et al. Possible involvement of Calcitonin I and II in calcium metabolism of the female reproductive physiology of goldfish (Carassius auratus). Int. Aquat. Res. 15, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.22034/IAR.2023.1965945.1322 (2023).

Guerreiro, P. M., Fuentes, J., Canario, A. V. & Power, D. M. Calcium balance in sea bream (Sparus aurata): the effect of oestradiol-17beta. J. Endocrinol. 173, 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.0.1730377 (2002).

Suzuki, N., Somei, M., Seki, A., Reiter, R. J. & Hattori, A. Novel bromomelatonin derivatives as potentially effective drugs to treat bone diseases. J. Pineal Res. 45, 229–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00623.x (2008).

de Vrieze, E., Moren, M., Metz, J. R., Flik, G. & Lie, K. K. Arachidonic acid enhances turnover of the dermal skeleton: studies on zebrafish scales. PLoS ONE 9, e89347. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089347 (2014).

Carnovali, M., Banfi, G. & Mariotti, M. Age-dependent modulation of bone metabolism in zebrafish scales as new model of male osteoporosis in lower vertebrates. GeroScience. 43, 927–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-020-00267-0 (2021).

Suzuki, N. et al. Parathyroid hormone 1 (1–34) acts on the scales and involves calcium metabolism in goldfish. Bone 48, 1186–1193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2011.02.004 (2011).

Suzuki, N., Suzuki, T. & Kurokawa, T. Suppression of osteoclastic activities by calcitonin in the scales of goldfish (freshwater teleost) and nibbler fish (seawater teleost). Peptides 21, 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00181-3 (2000).

Sekiguchi, T. et al. Calcitonin-typical suppression of osteoclastic activity by amphioxus calcitonin superfamily peptides and insights into the evolutionary conservation and diversity of their structures. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 246, 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.01.004 (2017).

Ikegame, M. et al. Melatonin is a potential drug for the prevention of bone loss during space flight. J. Pineal Res. 67, e12594. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12594 (2019).

Suzuki, N. & Hattori, A. Melatonin suppresses osteoclastic and osteoblastic activities in the scales of goldfish. J. Pineal Res. 33, 253–258. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.02953.x (2002).

Kobayashi, M., Aida, K. & Hanyu, I. Annual Changes in Plasma Levels of Gonadotropin and Steroid Hormones in Goldfish. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish. 52, 1153–1158. https://doi.org/10.2331/suisan.52.1153 (1986).

Lorenzoni, M., Corboli, M., Ghetti, L., Pedicillo, G. & Carosi A. Growth and reproduction of the goldfish Carassius auratus: a case study from Italy. In: Gherardi F, ed. Biological invaders in inland waters: Profiles, distribution, and threats. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 259-273 (2007) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6029-8_13

Zhang, D. et al. Defining global neuroendocrine gene expression patterns associated with reproductive seasonality in fish. PLoS ONE 4, e5816. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005816 (2009).

Hiramatsu, N. et al. Ovarian yolk formation in fishes: Molecular mechanisms underlying formation of lipid droplets and vitellogenin-derived yolk proteins. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 221, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2015.01.025 (2015).

Wood, C. M. & Shuttleworth, T. J. Flik, G., Verbost, P. M., Bonga, S. E. W. Calcium Transport Processes in Fishes. In. Cellular and Molecular Approaches to Fish Ionic Regulation, San Diego, CA: Academic 14, 317–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1546-5098(08)60251-4 (1995).

Larsson, D., Björnsson, B. T. & Sundell, K. Physiological concentrations of 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 rapidly decrease the in vitro intestinal calcium uptake in the Atlantic cod. Gadus morhua. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 100, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1006/gcen.1995.1150 (1995).

Mugiya, Y., Watabe, N. Studies on fish scale formation and resorption—II. Effect of estradiol on calcium homeostasis and skeletal tissue resorption in the goldfish, Carassius auratus, and the killifish, Fundulus heteroclitus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 57, 197-202 (1977) https://doi.org/10.1016/0300-9629(77)90455-8

Persson, P., Johannsson, S. H., Takagi, Y. & Björnsson, B. T. Estradiol-17β and nutritional status affect calcium balance, scale and bone resorption, and bone formation in rainbow trout. Oncorhynchus mykiss. J. Comp. Physiol. B 167, 468–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003600050098 (1997).

Persson, P., Sundell, K. & Björnsson, B. T. Estradiol-17β-induced calcium uptake and resorption in juvenile rainbow trout. Oncorhynchus mykiss. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 13, 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00003417 (1994).

Persson, P., Takagi, Y. & Björnsson, B. T. Tartrate resistant acid phosphatase as a marker for scale resorption in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss: effects of estradiol-17β treatment and refeeding. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 14, 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00004071 (1995).

Vaes, G. Cellular biology and biochemical mechanism of bone resorption. A review of recent developments on the formation, activation, and mode of action of osteoclasts. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 231, 239-271 (1988) PMID: 3286076

Henriksen, K. et al. Assessment of osteoclast number and function: application in the development of new and improved treatment modalities for bone diseases. Osteoporos. Int. 18, 681–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0286-8 (2007).

Duan, X., Yang, S., Zhang, L. & Yang, T. V-ATPases and osteoclasts: ambiguous future of V-ATPases inhibitors in osteoporosis. Theranostics. 8, 5379–5399. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.28391 (2018).

Nagy, V. & Penninger, J. M. The RANKL-RANK Story. Gerontology 61, 534–542. https://doi.org/10.1159/000371845 (2015).

Schjeide, O. A. Calcium transport in nonmammalian vertebrates. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 200, 165–173 (1985) (PMID: 3905108).

Berg, A. H., Westerlund, L. & Olsson, P. E. Regulation of Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) egg shell proteins and vitellogenin during reproduction and in response to 17beta-estradiol and cortisol. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 135, 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2003.10.004 (2004).

de Assis Ramos, M. M. et al. A review on lipid and polymeric nano-based 17-β-estradiol delivery systems: advances and challenges. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 27, 13633. https://doi.org/10.3389/jpps.2024.13633 (2024).

Wang, T., Li, S., Yu, Y. & Li, F. Sex reversal induced by 17β-estradiol may be achieved by regulating the neuroendocrine system of the Pacific white shrimp Penaeus vannamei. BMC Genomics 26, 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-025-11236-2 (2025).

Pinto, P. I. et al. Immunohistochemical detection of estrogen receptors in fish scales. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 160, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.10.011 (2009).

Yoshikubo, H. et al. Osteoblastic activity and estrogenic response in the regenerating scale of goldfish, a good model of osteogenesis. Life Sci. 76, 2699–2709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.063 (2005).

Beck, M. M. & Hansen, K. K. Role of estrogen in avian osteoporosis. Poult. Sci. 83, 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/83.2.200 (2004).

Shi, V. & Morgan, E. F. Estrogen and estrogen receptors mediate the mechanobiology of bone disease and repair. Bone 188, 117220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2024.117220 (2024).

Cipolla-Neto, J. & Amaral, F. G. D. Melatonin as a Hormone: New Physiological and Clinical Insights. Endocr. Rev. 39, 990–1028. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2018-00084 (2018).

Dubocovich, M. L. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXV. Nomenclature, classification, and pharmacology of G protein-coupled melatonin receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 343–380. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.110.002832 (2010).

Liu, J. MT1 and MT2 Melatonin Receptors: A Therapeutic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 56, 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124742 (2016).

Coelho, L. A. et al. Seasonal Variation of Melatonin Concentration and mRNA Expression of Melatonin-Related Genes in Developing Ovarian Follicles of Mares Kept under Natural Photoperiods in the Southern Hemisphere. Animals 13, 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13061063 (2023).

Zhao, C. et al. Changes of melatonin and its receptors in synchronizing turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) seasonal reproduction and maturation rhythm. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 41, 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13131-021-1923-y (2022).

McGuire, N. L., Kangas, K. & Bentley, G. E. Effects of Melatonin on Peripheral Reproductive Function: Regulation of Testicular GnIH and Testosterone. Endocrinology 152, 3461–3470. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2011-1053 (2011).

Miki, Y. et al. Melatonin is more effective on bone metabolism when given at early night than during the day in ovariectomized rats. Melatonin Res. 6, 161–172. https://doi.org/10.32794/mr112500147 (2023).

Dollins, A. B., Zhdanova, I. V., Wurtman, R. J., Lynch, H. J. & Deng, M. H. Effect of inducing nocturnal serum melatonin concentrations in daytime on sleep, mood, body temperature, and performance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 1824–1828. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.5.1824 (1994).

Dijk, D. J. et al. Melatonin effect on daytime sleep in men: suppression of EEG low frequency activity and enhancement of spindle frequency activity. Neurosci. Lett. 201, 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3940(95)12118-n (1995).

Tamura, H. et al. The role of melatonin as an antioxidant in the follicle. J. Ovarian Res. 5, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-2215-5-5 (2012).

Espino, J. et al. Impact of melatonin supplementation in women with unexplained infertility undergoing fertility treatment. Antioxidants (Basel). 8, 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox8090338 (2019).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410 (2020).

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by grants to J.H. (the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [JSPS] Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [B] no. 25K03509 and the Kobayashi foundation), N.S. (the JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [C] no. 23K10933), A.H. (the JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research [C] no. 22K11823), and K.W. (JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists, No. 22J01508). This work was supported in part by the cooperative research program of the Institute of Nature and Environmental Technology, Kanazawa University (acceptance nos. 23026 and 23028).

Funding

The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, 22J01508, 23K10933, 22K11823, 25K03509, Kanazawa University, 23026, Kobayashi foundation

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M., N.S. and A.H. contributed to the study conception. Y.M., K.W., R.M., and K.K. performed experiments. Y.M., K.W., R.M., K.K., H.M., N.S., J.H., and A.H. analyzed data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.H., K.W., Y.M., and A.H. All authors commented on it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maruyama, Y., Watanabe, K., Matsuoka, R. et al. Melatonin suppresses the plasma calcium level in female goldfish during the late and post-reproductive stages. Sci Rep 15, 31480 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14026-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14026-8