Abstract

A high-temperature-operable binary inverter was designed through structural optimization of SiC-based CMOS FinFETs using 3D TCAD simulations. A FinFET architecture was incorporated into SiC CMOS with an optimized fin structure to overcome the critical challenges of high subthreshold swing (SS) and threshold voltage (Vth) inherent in planar MOSFET-based SiC CMOS technology, thus achieving a high-performance logic system. Subsequent structural optimization led to Vth values of 1.83 and 2.54 V for the n-type and p-type FinFETs, respectively, along with substantially enhanced SS values of 73.33 and 77.74 mV/decade, respectively. Additionally, to validate the applicability of SiC CMOS FinFETs to high-temperature environments compared to conventional Si CMOS FinFETs, the self-heating characteristics, as well as the temperature-dependent behavior of Vth and SS, were analyzed up to 700 K. Finally, a binary inverter was designed based on the optimized FinFETs. The circuit operated at a low supply voltage of 3.3 V and achieved a noise margin of 0.820 V (0.249 VDD) with a maximum gain of 13.3 at 300 K. Especially, it maintained stable operation with a noise margin of 0.811 V (0.246 VDD) and a gain of 5.80 even at 700 K. These results confirmed its robustness and potential for next-generation logic systems and high-temperature CMOS applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The constant growth in aerospace, defense, automotive, and energy harvesting industries has led to an increasing demand for electronics that can reliably operate in high-temperature environments1,2,3,4,5. However, despite their long-standing dominance in integrated circuits, conventional Si-based semiconductors face fundamental limitations under extreme conditions, such as thermal instability, restricted frequency performance, and inadequate breakdown voltages6,7. This has accelerated the development of wide-bandgap semiconductors like silicon carbide (SiC), which can maintain stable operation at elevated temperatures without performance degradation, owing to their superior thermal conductivity and inherent material robustness8,9,10,11,12. These superior properties have rapidly positioned SiC as the leading choice for harsh-environment applications.

However, SiC-based systems still need to be integrated with Si CMOS circuits due to the limited development of SiC logic devices, significantly complicating the manufacturing process of SiC-based integrated circuits. This hybrid approach not only creates fabrication challenges but also imposes operational constraints in high-temperature environments where co-integrated Si logic components are required. Therefore, developing next-generation SiC CMOS devices becomes essential for implementing fully integrated system-on-chip (SoC) solutions and overcoming these limitations13,14. Successful development of such devices would eliminate heterogeneous integration requirements, thereby simplifying the fabrication process. Furthermore, SiC ICs eliminate the need for dedicated cooling or thermal isolation systems due to superior thermal conductivity (> 490 W/m K), allowing for more compact circuit designs15. Previous studies have been limited to demonstrating the basic applicability of SiC CMOS technology using planar MOSFET structures16. However, these implementations exhibit severely degraded complementary operation due to the threshold voltage (Vth) asymmetry between the n-type and p-type SiC devices. This effect originates from the carrier mobility imbalance, which prevents standard CMOS functionality. Moreover, their inherently high Vth values lead to high operating voltages, increasing power consumption. To address these limitations of conventional SiC CMOS technology, we propose utilizing recently developed SiC FinFET archietecture. Recent studies have successfully fabricated SiC based FinFETs and analyzed their performance, including on/off-state behavior, switching dynamics, and mobility/carrier concentration for implementation across diverse application fields17,18,19.

In this work, a FinFET structure was adopted to enhance gate controllability, thus achieving a low Vth value and enabling low-voltage operation of SiC-based CMOS devices. Furthermore, a multi-fin structure was introduced to compensate for the asymmetrical mobility and contact resistance that degrade the on-current in PMOS devices. The current characteristics were analyzed as functions of the fin width (WFin) and height (HFin) via TCAD simulations created using Sentaurus Synopsys. These simulations enabled optimization of the device structure for CMOS operation and the subsequent design of a low-voltage-operable SiC CMOS binary inverter. The material parameters and models of SiC, including carrier mobility, incomplete ionization, interface traps density, doping-dependent effects, and high-field dependance, were calibrated using experimental data obtained from fabricated SiC planar MOSFETs to ensure simulation accuracy. And the temperature-dependent variations in Vth and the subthreshold swing (SS), ON/OFF ratio and, drain induced barrier lowering (DIBL) for the optimized SiC CMOS FinFETs were analyzed across a wide temperature range from 300 to 700 K. The self-heating characteristics of these devices were also evaluated and compared with those of Si-based devices. Based on these researches, our study demonstrates the feasibility of implementing high-performance logic systems using SiC CMOS FinFET technology, which effectively addresses the performance degradation of conventional Si-based systems in high-temperature environments. The obtained results clearly revealed several advantages of replacing conventional Si CMOS logic systems with the SiC-based technology, particularly in high-temperature environments. Furthermore, the noise margin and gain of the designed binary inverter were analyzed up to 700 K, proving its reliable operation even at elevated temperatures. This work demonstrates a functional SiC-based CMOS logic system capable of stable high-temperature operation, addressing both the limitations of conventional Si technology in extreme environments and the critical challenges of existing SiC CMOS implementations.

Methodology

The fabricated SiC planar MOSFETs used for calibration is shown in Fig. 1a. The fabrication process of the SiC planar MOSFETs is detailed in Supplementary Fig. 1c. The device fabrication process begins with an n-type 4 H-SiC epitaxial layer (thickness = 12 μm, doping concentration = 1 × 1016 cm-3) grown on a n-type SiC substrate. The p-well region was formed through Al ion implantation (5 × 1017 cm-3), while N-doping (1 × 1020 cm-3) was employed to form the source/drain regions. All implanted species were activated through high temperature annealing at 1700 °C for 1 h in an Ar atmosphere. The gate dielectric was formed via thermal oxidation followed by NO annealing to minimize interface trap density at the SiO2/SiC interface. A 4000 Å-thick n + doped polysilicon layer was then deposited and patterned to form the gate electrodes. Ohmic contacts were established via Ni deposition (5000 Å) and rapid thermal annealing (1000 °C, 60 s) to form nickel silicide. The active region was defined through wet etching with channel dimensions of 8 μm × 10 μm.

The parameter calibration results between simulated and measured drain current (ID)-drain voltage (VDS) and ID-gate voltage (VGS) characteristics for the planar MOSFET are presented in Fig. 1b. Various modeling and parameter values were considered to evaluate the distinct material properties of SiC during the parameter calibration process, which differed from those of conventional Si. The inversion and accumulation layer mobility (IALMob) model was employed to account for the dominant scattering mechanisms within the channel region, including Coulomb scattering, phonon scattering, and surface roughness scattering20,21. Also, the dopant incomplete ionization model parameters were calibrated to account for the high activation energy originating from the strong covalent bonding of 4 H-SiC (Si–C bond energy = 4.6 eV). The model parameters, including the ionization energy, ionization coefficient, degeneracy factor, and cross section for p-type (Al) and n-type (N) dopants, were calibrated to represent the behavior of incomplete ionization accurately22,23. In addition to the modeling described above, various parameters and models were implemented to capture the material-specific characteristics of SiC. These included the interface trap profile24, mobility anisotropy depending on the crystal orientation25, mobility degradation depending on the doping concentration26,27, and high-field dependence models28. A high level of agreement between the simulation results and the measured data was achieved by implementing these parameter values and models, as shown in Fig. 1b. This validated the accuracy of the subsequent SiC CMOS FinFET simulations and significantly enhanced the predictive capability for device design optimization.

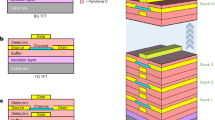

In addition, the process diagram of the SiC FinFET is also detailed in Fig. 2a. Although this study relies on TCAD simulations, a hypothetical process flow incorporating essential steps of SiC-based device fabrication and bulk FinFET processing is described. This ensures the structural parameters remain physically grounded thereby enabling meaningful comparison with experimentally fabricated devices reported in previous studies. The device fabrication begins with fin patterning using 193 nm water immersion lithography. To overcome the 45 nm half-pitch limitation of this technology, self-aligned double patterning (SADP) is employed to achieve fin widths under approximately 40 nm29. For inter-fin isolation, shallow trench isolation (STI) is formed by depositing SiO2 via PECVD, followed by CMP and wet etching to precisely define the HFin30. A 10 nm gate oxide is then grown by thermal oxidation, with subsequent nitridation annealing performed to reduce interface trap density at the SiC/SiO2 interface and improve current characteristics31. Gate electrodes are formed using LPCVD-deposited in-situ doped poly-Si, with phosphorus doping for n-type devices and boron doping for p-type devices. Source and drain regions are implanted with nitrogen for n-type and aluminum for p-type devices. Finally, ohmic contacts are formed by depositing Ni followed by 950 °C annealing for n-type devices32, and Ni/Ti/Al with 800 °C annealing for p-type devices33. This optimized fabrication process enables high-performance SiC CMOS FinFETs with excellent interface quality and contact properties.

Results and discussion

FinFET devices are characterized by superior performance owing to enhanced multi-gate coupling that enables higher drive currents, low SS values allowing for lower values of Vth, improved carrier mobility from reduced electric field effects, and small Vth mismatches between the n-type and p-type devices, which is essential for a balanced switching behavior as well as high noise margins in CMOS circuit implementations34. These characteristics were employed to overcome the issues of high SS and Vth values in previously reported SiC CMOS devices16.

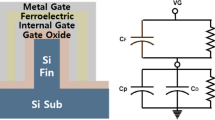

The SiC CMOS FinFET structures and the corresponding device parameters are illustrated in Fig. 2b, where PFin is fin pitch, Tox is gate oxide thickness, Lch is channel length, and Nch is channel doping concentration. The n-type device consisted of one fin, while the p-type device incorporated seven fins to compensate for low hole mobility. To achieve a small Vth value, n+ and p+ poly-Si gates were implemented for n-type and p-type devices, respectively. The doping concentrations were optimized to 5 × 1017 and 1 × 1020 cm-3 for the channel region and the source/drain using Al (n-type) and N (p-type) dopants, respectively. The simulation adopted reference specific contact resistance values of 2.8 × 10− 632 and 6.6 × 10− 5 Ω cm233 for the n- and p-type devices, respectively. The source/drain width was increased to expand the contact area in order to address contact resistance degradations in scaled devices, mitigating the impact on the on-current saturation. Additionally, p-type FinFET optimization was initially performed using a single-fin structure, providing a foundation for multi-fin structure aimed at balancing the on-current levels between n-type and p-type devices.

The device design specifically utilized quantum-confinement effects for optimal performance, focusing on a sub-60 nm value of WFin, where volume inversion became prominent35. The modified local density approximation (MLDA) model was adopted in simulations to account for these quantum mechanical effects within the narrow fin regions. The MLDA model effectively incorporated the quantum-confinement effects with reduced computational complexity and stable convergence, making it suitable for nanoscale FinFET simulations36.

Structure optimization

The structural characteristics of the SiC-based CMOS FinFETs that are crucial for high-performance logic design must be evaluated before analyzing their high-temperature behavior. Therefore, the characteristic variations in the properties of FinFETs were investigated as a function of WFin and HFin to obtain the optimized structure for CMOS operation. The fin structure optimization approach for SiC-based CMOS FinFETs was specifically aimed at achieving low power consumption by reducing the values of Vth and SS, as shown in Fig. 3. The Vth was defined as VGS at which ID = (W/L) ×10− 7 A (constant current method).

Initially, the procedure was focused on optimizing the WFin parameter for the n-type and p-type devices, at a fixed HFin value of 100 nm, as shown in Fig. 3a and b, respectively. Both n-type and p-type FinFETs exhibited improved Vth and SS values as the value of WFin was reduced. Significant improvements in Vth and SS were observed when the WFin value was lowered to 60 nm, due to the previously mentioned quantum mechanical effects. However, the improvement in device parameters began to saturate as the value of WFin was scaled below 30 nm. This was attributed to the trade-off between the enhanced volume inversion, which increased carrier concentration and the intensified surface roughness and phonon scattering, which deteriorated carrier mobility (see Fig. 4). Furthermore, sub-30 nm fabrication faces CMOS infrastructure limitations, requiring e-beam lithography instead of optical patterning37. Therefore, WFin = 30 nm was selected as the optimal point, balancing electrical characteristic optimization with fabrication challenges.

Subsequent optimization of HFin was conducted at the optimized WFin value of 30 nm. The values of Vth and SS decreased as HFin was increased up to 100 nm for both n-type and p-type devices. However, the improvement in SS saturated once the value of HFin increased beyond 100 nm. In addition, a slight increase was observed in the Vth parameter, suggesting an optimal HFin value of 100 nm. Furthermore, considering both process feasibility and structural stability, the optimized fin structure (WFin = 30 nm and HFin = 100 nm) with an aspect ratio of 3 provided an optimal balance between performance and structural stability38. This moderate aspect ratio avoided fabrication challenges, such as pattern collapse, which are common in high-aspect-ratio structures. Thus, an HFin value of 100 nm is a reasonable choice that ensures both electrical performance and process reliability.

Consequently, the optimized FinFETs exhibited Vth values of 1.83 and 2.54 V, with SS values equal to 73.33 and 77.74 mV/decade for n-type and p-type devices, respectively These results confirm their suitability for high-performance CMOS implementation, as all structurally optimized devices achieved both low Vth and SS values around 70 mV/decade—fully compatible with practical logic circuit requirements, as demonstrated in prior research39,40,41,42.

Transfer characteristics of the optimized SiC-based CMOS FinFETs at high temperatures

A comparative analysis of device electrical characteristics under high temperatures is essential to evaluate the feasibility of SiC-based CMOS FinFETs as a replacement for conventional Si CMOS devices in high-temperature applications. In this context, the temperature-dependent variations in the on-current and SS characteristics of the two types of devices were compared and analyzed.

The Si-based FinFET was designed with the same fin structure as the previously optimized SiC FinFET (WFin = 30 nm, HFin = 100 nm) to obtain a fair comparison between the two devices. Also, the n-type and p-type regions were doped with phosphorus and boron at equivalent doping concentrations, respectively. Furthermore, commonly used specific contact resistance values of 10⁻8 Ω cm² for n-type and 10⁻7 Ω cm² for p-type devices were applied to reflect the intrinsic characteristics of Si.

The transfer characteristics of the structurally optimized SiC CMOS FinFET across an ambient temperature range from 300 to 700 K are illustrated in Fig. 5a. A steady reduction in the value of Vth was observed in both n-type and p-type devices a temperature increased from 300 to 700 K, with ΔVth = 1.1 V for the n-type and 0.9 V for the p-type devices within this range. Additionally, the on-current levels of the n-type and p-type SiC FinFETs increased at high temperatures. Coulomb scattering is the primary factor limiting mobility under low-field conditions in conventional planar SiC MOSFETs43. However, quantum confinement induces volume inversion even at low electric fields in the structurally optimized SiC-based FinFETs proposed here, which leads to high carrier concentration within the narrow fin structure36. This high carrier concentration induces screening effects43, which shift the dominant mobility-limiting mechanism from Coulomb scattering to phonon scattering. Phonon scattering increases with temperature and leads to mobility degradation as temperature increases. The temperature-dependent phonon scattering mobility component (µSP) can be expressed by the following equation44:

where E⊥ denotes the electric field component perpendicular to the interface, A and B are numerical constants determined through theoretical analysis and experimental fitting, and T represents the ambient temperature. However, this effect is counterbalanced by a simultaneous increase in carrier concentration, as shown in Fig. 5c and d. Temperature-dependent increase in carrier concentration occurs because elevated temperatures reduce the occupied interfacial trap density33, enabling more carriers to participate in conduction, as depicted in Fig. 5c and d. Consequently, the SiC-based CMOS FinFETs displayed enhanced on-current performance under high-temperature operation. However, this improvement in current saturation for p-type devices was less pronounced compared to the n-type devices. This was attributed to the inherently high specific contact resistance of SiC-based p-type devices, which limited their on-current levels. A multi-fin structure can be adopted for p-type devices to mitigate this imbalance, enabling on-current matching with their n-type counterparts.

Conversely, Si-based FinFETs exhibited decreased on-current values at elevated temperatures (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online), as phonon scattering became dominant, causing severe mobility degradation45,46,47. These results demonstrated that SiC-based CMOS FinFETs offered a significant advantage over Si technology for high-temperature applications, as they maintained or even improved current drive capability under thermal stress while Si devices suffered due to performance degradation issues.

SS is another important parameter that must be evaluated at high temperatures to ensure the stable operation of CMOS devices, as its deterioration can significantly impact switching behavior and leakage current in thermally challenging environments. The variation in the SS value was analyzed for both Si and SiC CMOS FinFETs to assess this temperature-dependent behavior quantitatively. The results of this analysis are presented in Fig. 5b, which compares their thermal stability. The value of SS for Si-based CMOS FinFETs climbed to become approximately three times higher than that of SiC CMOS FinFETs as the temperature was increased from 300 to 700 K. Especially, the SS value of SiC FinFETs remained below 200 mV/decade for both n-type and p-type devices even at 700 K, while it exceeded beyond 350 mV/decade for Si FinFETs —an indication of unreliable CMOS operation. The temperature-dependent behaviors of both ON/OFF ratio (Table 1) and DIBL (Table 2) were also analyzed. At 300 K, these parameters show lower performance in SiC compared to Si, mainly due to SiC’s lower carrier mobility and higher trap density. However, under high-temperature conditions, while Si-based devices exhibit severe performance degradation that makes them unsuitable for logic applications, SiC-based devices demonstrate significantly better performance stability even at 700 K, suggesting their potential for reliable logic circuit operation in high-temperature environments. These results demonstrated that replacing conventional Si CMOS with SiC CMOS can effectively overcome the thermal limitations of Si while simultaneously ensuring reliable high-temperature operation.

Self-heating characteristics

It is necessary to consider all thermal factors, including self-heating effects, in order to accurately evaluate the behavior of CMOS devices under high-temperature conditions. Self-heating significantly affects the electrical characteristics of the device, making its analysis essential for understanding the behavior of the device at elevated temperatures48. In this study, the self-heating effect was observed in the structurally optimized SiC CMOS FinFET via DC characteristic analysis49. The value of ΔTmax (defined as the difference between maximum lattice temperature and operating ambient temperature) was measured as a function of DC power consumption to quantify this effect. Furthermore, given the temperature-dependence of both the thermal conductivity and heat capacity, the self-heating behavior under elevated temperature conditions was investigated to understand the operation of the device operation in high-temperature conditions50.

The lattice temperature profile in the cross-section of a SiC FinFET under the condition of VGS = VDS = 3.3 V is presented in Fig. 6a. This indicates that the high heat transfer characteristics previously reported in conventional Si bulk FinFETs were preserved51, where the heat generated at the fin top effectively dissipated through the bulk substrate. Thus, self-heating was almost negligible under low-power operation conditions due to the structural characteristics of bulk FinFETs and the high thermal conductivity of SiC.

However, considering the unique characteristics of SiC CMOS technology, it is essential to analyze the self-heating behavior not only at low VDD levels, such as 3.3 V, but also across a wide range of applications involving relatively higher operating voltages, such as 5.0 V. In addition, to compare the self-heating characteristics of SiC FinFETs with conventional Si FinFETs, the variation in ΔTmax as a function of DC power consumption was analyzed for both Si- and SiC-based FinFETs at operating temperatures of 300 and 700 K, as shown in Fig. 6b. The difference between the ΔTmax values of Si- and SiC-based FinFETs was minimal under low-power or low-temperature conditions due to the excellent heat dissipation-characteristics of conventional bulk Si FinFETs. However, a sharp difference in the value of ΔTmax between both types of devices was clearly observed at higher DC power levels or elevated temperatures. This temperature-dependent behavior was quantitatively assessed through the thermal resistance (Rth), defined as the slope of the ΔTmax versus DC power graph. As a result, the Rth values were found to be 0.209 K/µW for the Si-based FinFETs and 0.062 K/µW for the SiC-based FinFETs under low-temperature operation at 300 K. This indicated that SiC offers superior thermal stability even at low temperatures. In contrast, the Rth values were obtained to be 0.450 K/µW for the Si FinFETs and 0.173 K/µW for the SiC FinFETs under high-temperature operation at 700 K, demonstrating an even more pronounced difference. In particular, the rapid increase in the Rth value of the Si FinFETs further intensified the phonon scattering effects as the temperature increased, thereby accelerating the on-current degradation46,47.

a The obtained cross-sectional lattice temperature profile for n-type SiC-based FinFET for gate voltage (VGS) = drain voltage (VDS) = 3.3 V. The maximum temperature (Tmax) location and heat transfer paths have been indicated by arrows. b The variation in Tmax as a function of DC power for Si- and SiC-based FinFETs under ambient temperature of 300 and 700 K.

Additionally, the Si FinFET exhibited significant SS degradation for even slight temperature variations at high temperatures above 600 K, as observed in Fig. 5b. Conversely, the SiC-based FinFET displayed relatively lower sensitivity to such changes in temperature. This emphasized the importance of the excellent self-heating characteristics of SiC-based CMOS FinFETs in high-temperature operations, attributed to their low Rth values.

Design of a binary inverter for high temperatures

A binary inverter was designed using the optimized SiC-based CMOS FinFETs. A multi-fin structure was adopted for the p-type FinFET to address common challenges in SiC CMOS technology, such as the intrinsic asymmetry in carrier mobility and the mismatch in on-current levels between the n-type and p-type devices. The p-type device design was based on seven fins, enabling the switching voltage of the inverter to be set close to the 0.5 VDD, thereby achieving a more balanced performance.

Additionally, a low VDD of 3.3 V was achieved by exploiting the advantages of FinFET architecture to obtain a low Vth value, enabling low-power CMOS circuit implementation. This voltage level is widely used in standard ICs, facilitating compatibility with conventional systems. Consequently, the proposed design addresses both the power consumption issues reported in prior studies and the integration challenges with standard CMOS ICs.

The performance of the proposed binary inverter was further evaluated under elevated temperatures up to 700 K to verify its operational reliability. The effects of temperature on VTC, noise margin, maximum gain, and switching voltage were observed and analyzed. The variation in the VTC of the binary inverter from 300 to 700 K is illustrated in Fig. 7a. The switching voltage moved toward 0.5 VDD at high ambient temperatures, indicating that the inherent asymmetry between the n-type and p-type SiC-based CMOS devices, in terms of Vth and on-current, can be compensated during high-temperature operation. The low on-current of p-type devices at 300 K improved with an increase in temperature. This effect was amplified in the multi-fin structures, where simultaneous mobility improvement across multiple fins mitigated the current saturation far more effectively than in single-fin n-type devices. Figure 7b provides a quantitative analysis of how VTC characteristics vary with temperature, focusing on noise margin and maximum gain. It reveals how high-level noise margin and low-level noise margin (marked in Fig. 7a as NMH and NML, respectively) change differently with temperature, where the noise margin is determined by the smaller of these two values (Min (Low, High)). Significantly, the highest noise margin of 1.00 V (0.3 VDD) was observed at 600 K, attributed to the switching voltage approaching 0.5 VDD, resulting in nearly identical NMH and NML values at 600 K. This result stems from the switching voltage reaching 0.5 VDD, where the temperature-dependent increase in NML counterbalances the decrease in NMH, allowing the noise margin to be maintained even at high temperatures. Although the maximum gain slightly decreased at higher temperatures, the device demonstrated reliable operation not only at room temperature but also under high-temperature conditions.

Transient characteristics of SiC CMOS FinFETs and binary inverter

The gate capacitance of the SiC FinFETs and the propagation delay characteristics of a binary inverter were characterized to assess the applicability of the optimized SiC CMOS FinFETs to high‑frequency CMOS circuits. The gate capacitance of the optimized SiC CMOS FinFET was measured at 100 kHz with VDS = 0 V. Figure 8a reveals atto-farad-scale (aF) capacitance, confirming excellent potential for high-frequency operation. And the switching behavior of the CMOS inverter designed in the previous section was analyzed to evaluate dynamic performance (Fig. 8b). Parameters including rise time (tr), fall time (tf), propagation delays (tpHL, tpLH), and average delay (tp) were characterized at 300 K and 700 K (Table 3). As shown in previous sections, the reduced propagation delay at 700 K is attributed to the increased on-current of SiC FinFETs at high temperatures, demonstrating their superior high-temperature performance.

Conclusion

A SiC-based CMOS FinFET was designed by optimizing the fin structure to achieve characteristics suitable for CMOS operation. This approach successfully addressed issues reported in previous SiC-based CMOS designs, enabling the realization of a low Vth and SS device. The improved value of SS in the device proposed in this work makes it suitable not only for low-frequency but also for high-frequency applications, unlike conventional SiC CMOS technologies, which exhibit low SS values and can only be used for low-frequency applications. Specifically, at 700 K operation, the n-type and p-type SiC FinFETs demonstrate 59.1% and 47.1% lower SS, 2.9 and 4.4 times higher ON/OFF ratios, and 37.2% and 27.6% improved DIBL characteristics, respectively, compared to their Si FinFET counterparts. Both types exhibit 61.6% lower Rth, confirming their superiority for extreme-temperature applications.

Furthermore, a binary inverter operating at a low supply voltage of 3.3 V was successfully implemented, confirming that the optimized SiC CMOS FinFETs could retain the low-power consumption characteristic essential to CMOS technology. Simulation results also confirm reliable device operation and self-heating characteristics at temperatures up to 700 K, suggesting the applicability of SiC-based CMOS technology in high-temperature environments beyond the operational limits of conventional Si-based CMOS. These results demonstrate the capability of implementing high-performance logic systems using SiC CMOS technology, highlighting their potential as a next-generation alternative to conventional Si CMOS technology. To achieve a more robust and balanced CMOS operation, future studies should focus on simultaneously optimizing both the hole mobility of SiC PMOS and the contact resistance of SiC CMOS by addressing the asymmetry between p-type and n-type devices. Such improvements would not only enhance device symmetry but also enable the utilization of the increase in temperature-induced on-current more effectively, leading to superior high-temperature performance.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Neudeck, P., Okojie, R. & Chen, L. Y. High-temperature electronics—a role for wide bandgap semiconductors? Proc. IEEE. 90, 1065–1076. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2002.1021571 (2002).

Johnson, R., Evans, J., Jacobsen, P., Thompson, J. & Christopher, M. The changing automotive environment: high-temperature electronics. IEEE Trans. Electron. Package Manuf. 27, 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEPM.2004.843109 (2004).

Watson, J. & Castro, G. A review of high-temperature electronics technology and applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 26 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-015-3459-4 (2015).

Dreike, P., Fleetwood, D., King, D., Sprauer, D. & Zipperian, T. An overview of high-temperature electronic device technologies and potential applications. IEEE Trans. Compon. Package Manuf. Technol. Part. A. 17, 594–609. https://doi.org/10.1109/95.335047 (1994).

Buttay, C. et al. State of the art of high temperature power electronics. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 176, 283–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2010.10.003 (2011). Microtechnology and Thermal Problems in Electronics.

Kroetz, G. H., Eickhoff, M. H. & Moeller, H. Silicon compatible materials for harsh environment sensors. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 74, 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-4247(98)00296-9 (1999).

French, P., Krijnen, G. & Roozeboom, F. Precision in harsh environments. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2 https://doi.org/10.1038/micronano.2016.48 (2016).

Wijesundara, M. & Azevedo, R. Silicon Carbide Microsystems for Harsh Environments vol. 22 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

Kimoto, T. & Cooper, J. A. Fundamentals of Silicon Carbide Technology: Growth, Characterization, Devices and Applications (Wiley, 2014).

Mehregany, M., Zorman, C., Rajan, N. & Wu, C. H. Silicon carbide mems for harsh environments. Proc. IEEE 86, 1594–1609. https://doi.org/10.1109/5.704265 (1998).

Harris, G. L. Properties of Silicon Carbide13 (Iet, 1995).

Hornberger, J. et al. Silicon-carbide (sic) semiconductor power electronics for extreme high-temperature environments. In. IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings (IEEE Cat. No.04TH8720), vol. 4, 2538–2555 Vol.4, (2004). https://doi.org/10.1109/AERO.2004.1368048 (2004).

Kuhns, N. et al. Complex high-temperature Cmos silicon carbide digital circuit designs. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 16, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDMR.2016.2530664 (2016).

Chen, J. S., Kornegay, K. & Ryu, S. H. A silicon carbide Cmos intelligent gate driver circuit with stable operation over a wide temperature range. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits. 34, 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1109/4.743772 (1999).

Cheng, Z. et al. High thermal conductivity in wafer-scale cubic silicon carbide crystals. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1891898/v1 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. A review of silicon carbide Cmos technology for harsh environments. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 178, 108422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2024.108422 (2024).

Udrea, F. et al. Experimental demonstration, challenges, and prospects of the vertical sic finfet. In 2022 IEEE 34th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs (ISPSD), 253–256, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISPSD49238.9813617 (2022).

Naydenov, K., Donato, N. & Udrea, F. Operation and performance of the 4 h-sic junctionless finfet. Eng. Res. Express. 3 https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-8695/ac12bc (2021).

Naydenov, K. et al. The finfet effect in lateral 4 h-sic and silicon multi-gate mosfets. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 39 https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6641/ad8e7f (2024).

Mujtaba, S. A. Advanced Mobility Models for Design and Simulation of Deep Submicrometer MOSFETs (Stanford University, 1996).

Lee, J. W. et al. Mobility analysis of surface roughness scattering in Finfet devices. Solid State Electron. 62, 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sse.2011.04.020 (2011).

Hitova, L., Yakimova, R., Trifonova, E., Lenchev, A. & Janzén, E. Heat capacity of 4 h-sic determined by differential scanning calorimetry. J. Electrochem. Soc. 147, 3546 (2000).

Kuznetsov, N. & Zubrilov, A. Deep centers and electroluminescence in 4 h Sic diodes with a p-type base region. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 29, 181–184 (1995).

Potbhare, S., Goldsman, N., Pennington, G., McGarrity, J. M. & Lelis, A. Characterization of 4 h-sic mosfet interface trap charge density using a first principles coulomb scattering mobility model and device simulation. In International Conference On Simulation of Semiconductor Processes and Devices, 95–98 (IEEE, 2005).

Pernot, J. et al. Electrical transport in n-type 4 h silicon carbide. J. Appl. Phys. 90, 1869–1878 (2001).

Hatakeyama, T., Fukuda, K. & Okumura, H. Physical models for Sic and their application to device simulations of Sic insulated-gate bipolar transistors. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 60, 613–621. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2012.2226590 (2013).

Ayalew, T. SiC semiconductor devices technology, modeling and simulation. Ph.D. thesis, Technische Universität Wien (2004).

Lophitis, N., Arvanitopoulos, A., Perkins, S. & Antoniou, M. TCAD Device Modelling and Simulation of Wide Bandgap Power Semiconductors (2018).

Bencher, C., Chen, Y., Dai, H., Montgomery, W. & Huli, L. 22nm half-pitch patterning by Cvd spacer self alignment double patterning (sadp)—art. No. 69244e. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.772953 (2008).

Radamson, H. et al. The challenges of advanced Cmos process from 2d to 3d. Appl. Sci. 7 https://doi.org/10.3390/app7101047 (2017).

Chanthaphan, A., Hosoi, T., Shimura, T. & Watanabe, H. Study of sio2/4 h-sic interface nitridation by post-oxidation annealing in pure nitrogen gas. AIP Adv. 5 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4930980 (2015).

Chang, S. C., Wang, S. J., Uang, K. M. & Liou, B. W. Investigation of au/ti/al ohmic contact to n-type 4 h–sic. Solid State Electron. 49, 1937–1941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sse.2005.08.013 (2005).

Konishi, R. et al. Development of ni/al and ni/ti/al ohmic contact materials for p-type 4 h-sic. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 98, 286–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-5107(03)00065-5 (2003).

Jurczak, M., Collaert, N., Veloso, A., Hoffmann, T. & Biesemans, S. Review of finfet technology. In 2009 IEEE International SOI Conference, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/SOI.2009.5318794 (2009).

Kato, T. et al. Enhanced performance of 50 nm ultra-narrow-body silicon carbide mosfets based on finfet effect. In 2020 32nd International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs (ISPSD), 62–65, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISPSD46842.9170182 (2020).

Udrea, F. et al. The finfet effect in silicon carbide mosfets. In 2021 33rd International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs (ISPSD), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.23919/ISPSD50666.2021.9452282 (2021).

Kretz, J., Dreeskornfeld, L., Hartwich, J. & Rösner, W. 20 nm electron beam lithography and reactive ion etching for the fabrication of double gate finfet devices. Microelectron. Eng. 67–68, 763–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9317(03)00136-9 (2003). Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Micro- and Nano-Engineering.

Kawasaki, H. et al. Challenges and solutions of finfet integration in an sram cell and a logic circuit for 22 nm node and beyond. In 2009 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2009.5424366 (2009).

Salahuddin, S. & Datta, S. Can the subthreshold swing in a classical Fet be Lowered below 60 mv/decade? 2008 IEEE Int. Electron. Devices Meeting. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2008.4796789 (2008).

Yongbiao, Z., Feng, Z., Zhou, Y. & Han, S. T. Energy-efficient transistors: suppressing the subthreshold swing below the physics limit. Mater. Horizons. 8 https://doi.org/10.1039/D0MH02029J (2021).

Beckers, A. & Enz, C. Theoretical limit of low temperature subthreshold swing in field-effect transistors. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. PP 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2019.2963379 (2019).

Wu, C. et al. High performance 22/20nm finfet cmos devices with advanced high-k/metal gate scheme. In 2010 International Electron Devices Meeting, 27.1.1–27.1.4. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2010.5703430 (2010).

Potbhare, S. et al. A physical model of high temperature 4 h-sic mosfets. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 55, 2029–2040. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2008.926665 (2008).

Potbhare, S., Goldsman, N., Pennington, G., Lelis, A. & McGarrity, J. Numerical and experimental characterization of 4 h-silicon carbide lateral metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 044515. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2335967 (2006).

Nasri, F. et al. Temperature effects on electrical response of Finfet transistors in the static regime. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 70, 1595–1600. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2023.3248537 (2023).

Longxiang, Y. & Du, G. Impact of ambient temperature on the self-heating effects in Finfets. J. Semicond. 39 https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-4926/39/9/094011 (2018).

Feng, T., Lindsay, L. & Ruan, X. Four-phonon scattering significantly reduces intrinsic thermal conductivity of solids. Phys. Rev. B. 96, 161201. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.96.161201 (2017).

Song, Y. et al. Electrical and thermal performances of omega-shaped-gate nanowire field effect transistors for low power operation. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 20, 4092–4096. https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2020.17787 (2020).

McAlister, S., Bardwell, J., Haffouz, S. & Tang, H. Self-heating and the temperature dependence of the Dc characteristics of Gan heterostructure field effect transistors. J. Vac Sci. Technol. A 24 https://doi.org/10.1116/1.2172921 (2006).

Glassbrenner, C. J. & Slack, G. A. Thermal conductivity of silicon and germanium from 3°k to the melting point. Phys. Rev. 134, A1058–A1069. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.134.A1058 (1964).

Poljak, M., Jovanovic´, V. & Suligoj, T. Improving bulk finfet dc performance in comparison to soi finfet. Microelectron. Eng. 86(2078). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mee.2009.01.066 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Korea Electrotechnology Research Institute (KERI) Primary research program through the National Research Council of Science and Technology (NST) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) (No. 25A01009, 25A01006). This work was also supported in part by NRF funded by the Korean government (RS-2024-00405200), and in part by the Brain Korea 21 Four Program. And, the EDA tool was supported by the IC Design Education Center (IDEC), Korea.

Funding

T. S. K. (Tae Seong Kwon), D. Y. P. (Do Yeon Park), H. W. K. (Hyoung Woo Kim), and J. H. S. (Jae Hwa Seo) : This research was supported by the Korea Electrotechnology Research Institute (KERI) Primary Research Program through the National Research Council of Science & Technology (NST) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) (No. 25A01009, 25A01006). T. S. K. (Tae Seong Kwon), D. Y. P. (Do Yeon Park), and S. Y. W. (Sung Yun Woo) : This work was also supported in part by NRF funded by the Korean government (RS-2024-00405200), and in part by the Brain Korea 21 Four Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. S. K. prepared figures and wrote the main manuscript text. Y. J. Y., J. H. S., and S. Y. W. conceptualized the study. J. H. B. contributed to the investigation, supervision, review, and editing of the manuscript. D. Y. P. corrected and improved the details of the manuscript. Y. S. S and H. W. K. conducted simulation study and data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwon, T.S., Yoon, Y.J., Park, D.Y. et al. Structurally optimized SiC CMOS FinFET for high-temperature and low-power SoC logic integration. Sci Rep 15, 28158 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14081-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14081-1