Abstract

Some conventional drugs are swiftly accessible and poorly soluble in the body. Although it is less soluble and accessible, silymarin, a well-known antioxidant drug, is used to treat several ailments. It is integrated into green-designed Fagonia cretica extract (FCE) based on PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 in this work to enhance these characteristics. UV–visible spectrometry, X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and zeta potential analysis were all used to thoroughly analyze the nanocomposites. As a result, ZnFe2O4 nanocomposites (NCs) produced nanostructures with an average crystal size of 7.66 nm, whereas PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 nanodrug produced with an average crystal size of 25.38 nm. The ZnFe2O4 NCs produced nanostructures with an average grain size of 332 nm and 504 nm, respectively as deduce by SEM analysis. Silymarin was estimated to have a loading efficiency of 27.39% into ZnFe2O4 NCs. To examine the produced nano-drug’s in vivo antioxidative capacity in the liver in comparison to pure silymarin, albino rats intoxicated with CCl4 were administered different dosages of 500 and 1500 μg/kg body weight. In hepatic tissue, CCl4 increased ROS and TBARS and lowered SOD, POD, and CAT levels, causing DNA damage that was mitigated subsequently by PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4. In a rat model of CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity, the in vivo assessment experiments showed that the synthesized PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 efficiently displayed a hepatoprotective effect by mitigating cellular abnormalities caused by CCl4 toxication. Additionally, the PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 was shown to reduce the degree of DNA damage in the COMET experiment. In contrast to the traditional drug silymarin, the PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4. Nanocomposites may be useful in the future in sustaining a variety of tissues by lowering oxidative stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, liver injuries are a major health concern that necessitates the development of novel therapeutic approaches1. Numerous antiquated methods for boosting a drug’s bioavailability and effectiveness involve the use of various carrier molecules; nonetheless, these materials have demonstrated toxicity and numerous adverse effects on healthy cells and organs2. Among the different strategies, nanotechnology has shown promise in providing customized solutions for medication delivery3,4,5 and treatment effectiveness6,7. Because of their remarkable qualities, nanoparticles are widely used in a variety of biomedical applications8,9,10,11,12. Because of their special qualities, they are well-suited for biological applications, such as cell separation13, medication delivery, immunoassays14, and biosensing15. Traditional chemical techniques for creating nanoparticles frequently use hazardous substances, which can be harmful to the environment. Changing synthesis methods to green chemistry16, which is safe and avoids harmful compounds, is becoming more and more important to allay these worries17,18,19,20.

Various therapeutic molecules can be produced by plants which can be employed as biomaterials21. The well-known herbal remedy Fagonia cretica has anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties, as well as immunomodulatory, antioxidant, anti-stomach ulcer, blood pressure-regulating, reducing-potential, and antiparasitic properties. F. cretica has a wide variety of plant metabolites that are fit for human consumption, such as terpenoids, alkaloids, coumarins, tannins, phenolic acids, sterols, flavonoids, and saponins22. This plant has very active functional biomolecules that play a key role in stabilizing and reducing the nanomaterials23,24. Leveraging the bioactive components present in the plant extract25This approach ensures the resulting nanocomposite is not only sustainably produced but also possesses biodegradable26, biocompatible24,27, and eco-friendly characteristics28.

Silymarin is a well-known hepatoprotective and antioxidative agent29,30. It is derived from the seeds and fruits of milk thistle, belonging to theAsteraceae family,and has a long history of use in treating liver diseases due to its reported antioxidative activities31,32. However, challenges such as limited bioavailability, rapid elimination, poor absorption, and low water solubility have hindered its preference33,34,35. Although there have been multiple attempts to solubilize SIL, none of them have produced any fruitful pharmacological results. The use of advanced nanotechnology may be essential for enhancing the pharmacological effects and bioavailability of drugs, especially those derived from plants36. Numerous technologies can be used to administer drugs with low water solubility, including solid dispersion, reducing the drug’s crystalline size, using excipients (lipid formulations, complexing agents, surfactants, etc.) to improve solubility, and, more recently, using nanocomposites as vehicles for the controlled and gradual release of pharmaceuticals. This approach reduces side effects and addresses availability and resistance issues. Plenty of nanocomposites have been used for drug delivery.

The folic acid-gold nanocomposite was used as a carrier to release gemcitabine to treat human mammary gland breast adenocarcinoma37, and PEG@CNTs nanocomposite was used for cisplatin loading to treat head and neck cancer38. Bismuth sulphide nanoparticles composite with mesoporous silica nanoparticles were used to load doxorubicin for the treatment of multidrug-resistant breast cancer39.

The present study focuses on the green synthesis of ZnFe2O4 NCs by using F. cretica plant extract as a reducing agent40,41 and sustainable production of silymarin-loaded, PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 NCs42,43. PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 NCs have garnered significant attention in the medical and nanotechnology fields due to the low toxicity associated with Zn2 + and Fe ions44,45,46. And they were used to mitigate the CCl4 toxicity. Despite the utility of iron oxide nanoparticles in therapeutic agents, challenges such as agglomeration, biodegradability, and toxicity persist47,48,49. To overcome these limitations, nano-ferrites are prepared with surface modifications involving other oxides. This study not only contributes to the growing field of Nano-medicine but also addresses the urgent need for safer and more effective treatments for liver-related ailments. By sustainably harnessing the power of nanotechnology, this research endeavors to pave the way for advanced therapeutic interventions to overcome the challenges posed by liver injuries.

Experimental section

Materials

All the chemicals used for ZnFe2O4 NCs synthesis, serology, histopathology and oxidative/antioxidant enzymes study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). All chemicals and reagents used throughout the experiments were of analytical or HPLC grade and were used without any purification.

Fagonia cretica extract formation

We used 10 g of powder (F. cretica plant, collected from the Cholistan Institute of Desert Studies, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur) for plant extract formation in a conical flask with 100 mL of distilled water. The mixture was heated for 2 h, at 90 °C. The extract solution was filtered using filter paper and placed in an oven (LabTech LDO-060E, Daihan Labtech co., Ltd. Korea) overnight at 80 °C to obtain the dry powder50. The resulting product F. cretica extract (FCE), was preserved for further experiments.

Green synthesis of ZnFe2O4 NCs

Facile green synthesis of ZnFe2O4 NCs was done by using a previously used method with a few modifications51. For synthesis, two solutions were formed; solution one contains zinc acetate dihydrate (0.5 g in 50 ml dist. H2O) and solution 2 contains (1 g FeCl3 in 50 ml dist. H2O). Both solutions were mixed, and 10 ml of FCE was added. Further pH 12 was maintained with 3 M sodium hydroxide NaOH solution. The whole mixture was placed on a hotplate and vigorous stirring was done for 3 h at 80 °C. The color of the solution was turned from brown to reddish brown, which was the visual confirmation of biological ZnFe2O4 NCs formation. The solution was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min using (HERMLE Z300K centrifuge (Germany), and precipitates were washed thrice with dist. H2O. The resulting product was dried at 80 °C for 24 h, and the powder form product was stored for further use.

Synthesis of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4

To load the silymarin drug in ZnFe2O4 NCs, the previously used method was applied with little modification52. First, 1 g of ZnFe2O4 NCs was mixed with silymarin solution (200 mg in 40 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO). The silymarin and ZnFe mixture was placed on a hotplate at room temperature, with 24 h of stirring. To remove the adsorbed drug on the surface, the silymarin-loaded ZnFe2O4 was cleaned three times with a 1:1 ratio of methanol and dist. H2O. After washing, the solution was centrifuged for 8 min at 4000 rpm. The yellowish precipitates in the pallet were dried overnight at 80 °C in an oven. The resulting silymarin drug-loaded ZnFe2O4 NCs were obtained. Furthermore, for the biocompatible particle formation, the previously used procedure was applied with little modifications53. 250 mg of silymarin-loaded ZnFe2O4 NCs were mixed in 30 mL of polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution (1.6 mM). After 24 h vigorous stirring at room temperature, the solution was washed with water and methanol (1:1) and centrifuged for 8 min at 4000 rpm. The obtained PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 NCs were dried for 24 h at 80 °C in an oven and preserved for the next characterization and applications. The percentage of the silymarin loading in ZnFe2O4 NCs was calculated by the Eq. 54:

Characterization

Various characterization techniques were systematically employed to validate the successful formation of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4. The formation and silymarin loading in ZnFe2O4 NCs were confirmed using UV–vis absorption spectra on an (Agilent Cary 60 spectrophotometer USA) between the 200 − 800 nm spectral range. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis between the scanning range of 5 − 80° was done to find the crystalline behavior of the samples using a (Bruker D8 Germany). Different functional groups in samples were determined by FTIR analysis between the 650 to 4000 scanning range with Agilent FTIR Spectrophotometer (Cary 360-ATR USA). To observe the morphology and shape of the NCs, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted with Cube 10, an Emcraft instrument from South Korea. To determine the surface charge zeta potential (ξ), analysis was performed on ZS XPLORER (Malvern Panalytical, UK) at 25 °C.

In vitro drug release study

ZnFe2O4 NCs were carefully chosen for the drug delivery application, and their efficacy and release properties were examined to evaluate their performance. A significant part of therapeutics involves managing drug release, which aims to maximize pharmaceutical delivery for maximal effectiveness and minimize negative effects. Enhancing treatment results and patient compliance greatly depends on the capacity to regulate the release of medications at a desired rate, duration, and location. It entails creating drug delivery systems that can precisely target the afflicted tissues or cells and control the release of treatments over a predefined period. To assess the release tendency under various circumstances, the drug release investigation was carried out at two distinct pH levels: an acidic medium (pH 5.0) and a physiological pH (7.4). To accomplish physiological conditions, 20 mg of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 was dissolved in 50 ml of each buffer solution. These solutions were shaken for 36 h at 37 °C. At various intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36), 2 ml of sample was withdrawn from each of the pH mediums and immediately replaced with an equal volume of the new buffer. The drug-releasing capacity from the ZnFe2O4 NCs was calculated with UV spectrometry at 288 nm55. The silymarin drug release percentage (%) was calculated by using the following formula56.

Here, mr is the released and ml is the total amount of encapsulated silymarin.

In vivo evaluation

Animal ethics

For in vivo studies, twenty-four Wistar Albino rats (Rattus norvegicus) weighing between 100 and 160 g were obtained from the Pharmacy Department, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan. Each group having four rats was placed in a separate clean steel cage under carefully regulated conditions, including a 20–25 °C temperature range, 60 ± 4% humidity, and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Throughout the trial, the rats were fed a normal rodent diet and had unlimited access to water. The rats were acclimated to their surroundings for one week before the trial. All experiments followed the National Institutes of Health’s "Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals" (NIH publication no. 85–23, 1985) and were approved ethically by the University’s ethical committee. Before any surgery, the animals were fasted for 12 h.

Dose selection and drug administration

For evaluation of the hepatoprotective effects of prepared PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4, all rats were split up into six groups. Randomization and blinding measures are performed while each group consists of four rats. The dosing pattern for each group was used by following the previously published study57:

Group T1: The control group without any treatment, with excess food and water.

Group T2: In this group, rats were treated for 7 days with void ZnFe2O4 NCs 1000 μg/kg body weight.

Group T3: In this group, rats were treated with CCl4 (1 mL/kg body wt..) in olive oil as a carrier with a 3:7 v/v ratio.

Group T4: In this group, rats were treated for 7 days with 100 mg/kg body weight of silymarin after 24 h of CCl4 toxicity.

Group T5: In this group, rats were treated for 7 days with PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 with a concentration of 500 µg/kg body weight after 24 h of CCl4 toxicity.

Group T6: In this group, rats were treated for 7 days with PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 with a concentration of 1500 µg/kg body weight after 24 h of CCl4 toxicity.

All the treatments were given intraperitoneally (i.p.).

On the eighth day following the trial’s end, the blood was collected from each rat’s jugular vein for hematological analysis using EDTA-anticoagulated tubes and for biochemical analysis in falcon tubes. The serum was extracted for analysis by centrifuging the blood for 15 min at 4000xg at 4 °C58. Following dissection, the liver was removed right away, cleaned with normal saline, weighed, and split into two halves. One piece was kept at -80 °C for biochemical and enzymatic tests, while the other was kept in a 10% formalin solution for histological analysis59.

Physical parameters

Daily records of the feed intake were made. Every day, several physical conditions like diarrhea, poor posture, anorexia, fatigue, and behavioral abnormalities, were also assessed. The starting and final body weights were determined by using the following formula:

While using the following formula, the relative weight of the liver (as a percentage of body weight) was calculated7.

Hematology parameters

An automated hematology analyzer (HEMA-V6190, China) was employed to evaluate the hematological profile of rats in both treated and untreated groups. Blood parameters such as red blood cells (RBC) and white blood cells (WBC) counts, hemoglobin (HGB), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), hematocrit (HCT), and lymphocytes were assessed within an hour after blood collection.

Serum biochemistry analysis

To assess hepatotoxicity, serum biochemical analysis was conducted using a fully automated chemistry Beckman Coulter-AU680 analyzer, USA. Serum parameters, including Aspartate transaminase (AST), Alanine transaminase (ALT), and total bilirubin, were measured to monitor liver function.

Tissue homogenization and biochemical analyses

To estimate oxidative and antioxidant enzymes, the frozen livers were thoroughly homogenized in 2 mL phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH = 7.4). Following 20 min, the homogenates were centrifuged for 5 min at 6000 rpm, and the supernatant was collected and stored at 4 °C to assess the different biomarkers. Oxidative stress biomarkers, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), were assessed at wavelengths of 505 nm and 532 nm, respectively60. Concurrently, various antioxidant parameters, such as catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and peroxidase (POD), were determined at wavelengths of 240 nm61, 560 nm62, and 470 nm63, respectively, utilizing a UV − vis spectrophotometer (752 UV, UK). A minimum of three readings were recorded at 15-s intervals during the analysis.

Histopathological assessment

Paraffin-fixed stained liver slices were subjected to histopathological evaluation using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains64. A microtome was used to section the liver, and the stained slides were examined by an experienced pathologist using a compound microscope (IRMECO IR-850, China) at 40X magnification65.

Comet assay

Following a previous process, the evaluation of DNA damage in liver tissues was conducted using single-cell gel electrophoresis66. Following dissection, the organs are promptly submerged in cold normal saline. 200 mg of hepatic tissue was homogenized and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min, and the cells from the pellets were mixed with 0.75 percent low-melting-point agarose (LMPA). The cells in LMPA were placed on sterilized glass slides that had been dipped in 0.1% normal melting point agarose (NMPA) and allowed to solidify at 4 °C for 10–12 min. After coating the slide once more with LMPA, it was submerged in the lysis buffer for ten minutes. Following the electrophoresis at 25 V, the slides were stained with 1% ethidium bromide and were examined at 100X magnification under the fluorescence microscope. To determine the frequency of DNA damage in each tissue, 400–500 cells on the slide were examined. DNA damage was defined as an emitted “cloud” of DNA material that either develops a tail towards the electric field or fluoresces surrounding the nucleus.

Statistical analysis

To examine the treatment effects of the prepared PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4, IBM SPSS version 20 was used to do a one-way analysis of variance. All measured parameters, including weight, hematology, serum biochemistry, and oxidative/antioxidant biomarkers, were provided as mean ± standard deviation for the PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 treated and normal group’s data. P ≤ 0.05 was used as the significance threshold to compare the various treatments.

Results and discussions

The green synthesis ofPEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 Nanocomposits, characterization, and their biological and chemical properties, especially the hepatic tissues studies, hematological parameters, which play a key role in reducing ROS and DNA damage in the rat model of liver injury, as shown in Fig. 1.

Physicochemical characterizations

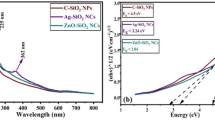

We verified the synthesis of ZnFe2O4 NCs and PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 with the help of UV–vis spectra (Fig. 2a). ZnFe2O4 NCs showed absorbance at 341 nm, which matches with previous published work67. Pure drug silymarin showed absorbance at 262 nm and 318 nm68, while PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 showed absorbance at 288 nm and 336 nm. The band shifting from 341 to 336 nm and from 262 to 288 nm is due to the composite formation between ZnFe2O4 NCs and the silymarin drug. PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 spectra confirmed the presence of silymarin with ZnFe2O4 NCs. The FTIR results of ZnFe2O4 NCs, free silymarin, and PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 are shown in Fig. 2c.

The FTIR spectrum of ZnFe2O4 NCs showed characteristic peaks such as 842 for (C-H, aromatic stretch), 1024 for (C–O), 1398 for (S = O), 1551 for (N–H bend), 2105 for (C = C bend), 3233 for (O–H bend). FTIR spectrum of pure silymarin gave characteristic peaks at 903 and 994 for (C-H out of plane bending for alkenes), 1279 for (C–O stretching), 1654 for (-C = O stretching), 2105 (C = C), 2918 for (C–H, alkyl), 3323 for (O–H)69. The PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 spectrum showed that due to the presence of silymarin with ZnFe2O4 NCs, the shifting of peaks observed from 842, 1024, 1398, 1551, 2105, and 3323 to 829, 1066, 1321, 1565, 2109, and 3338, respectively. Furthermore, an additional peak at 2859 for (C-H stretch) indicated that the silymarin drug had been successfully encapsulated within ZnFe2O4 NCs55. Figure 2b demonstrates the XRD analysis of ZnFe2O4 NCs, free silymarin, and PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4. The peaks for ZnFe2O4 NCs matched well with JCPDS card no 82–104970. The ZnFe2O4 NCs analysis diffractogram represents sharp and intense peaks at 2θ = 27.19°, 31.42°, 45.18°, 56.30°, and 62.97 o, which correspond to the planes of (220), (311), (400), (511), (440), respectively. The silymarin represents characteristic peaks at 2θ = 12.78°, 15.62°, 18.72°, 22.47°, 25.28°, 28.96° and 41.77° demonstrating the crystalline behavior of silymarin. For silymarin-loaded NCs, peaks at 2θ = 31.64 o, 45.68°, 56.43°, and 62.54 o are for ZnFe2O4 NCs, while peaks at 22.55 o, 29.53 o, and 34.45 o confirmed the silymarin’s presence in PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4. The PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 analysis showed crystalline behavior because of the silymarin’s encapsulation with ZnFe2O4 NCs. The following Scherrer equation was used to calculate the crystalline size of the manufactured NCs71:

D is for the average crystal size of NCs, K for the constant, λ is for X-ray wavelength, θ for Bragg’s angle, whereas line broadening at full width at half maximum (FWHM) is denoted by β72. The average crystalline size determined from XRD for ZnFe2O4 NCs was 7.66 nm73 Table S2 while for PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 the determined average crystalline size was 25.38 nm Table S3. The current study is supported by a previous study that prepared ZnFe2O4 NCs between the 7 to 40 nm range74. The greater crystalline size of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 than ZnFe2O4 NCs is because of the drug encapsulation in ZnFe2O4 NCs crystals. The surface structure of pure ZnFe2O4 NCs is oval and spherical75, which are in good agglomeration because of the presence of magnetic interaction among the particles, as illustrated in Fig. 3a. SEM of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 depicted a non-defined structure, which is due to the silymarin loading76 Fig. 3b. Comparing these SEM pictures further verified that the silymarin was loaded with ZnFe2O4 NCs. The average grain size of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 and ZnFe2O4 nanostructures was determined using SEM with the aid of the histogram analysis. Figures 3c and 3d illustrate the average grain size of ZnFe2O4 NCs and PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4, which were 332 nm and 504 nm, respectively. These results match the previous literature77. The zeta potential analysis results unequivocally showed that the values for synthesized ZnFe2O4 NCs were detected at 18.62 ± 1.22 mV and + 4.86 ± 0.69 for PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 (Fig. 4 a, b). Because it contains several flavonoids, silymarin has a high positive charge78. Following drug loading, silymarin is responsible for the zeta-potential’s transition from negative to positive. These findings confirmed the adherence of the positively charged silymarin with the negatively charged ZnFe2O4 NCs.

Drug loading efficiency

To assess the potential use of ZnFe2O4 NCs as the hepatoprotective system, the traditional antioxidant silymarin was loaded onto ZnFe2O4 NCs using a previously developed drug-loading technique79. After five hours, there was sufficient drug loading (27.39%), which, in comparison to earlier research, represents a noteworthy percentage of poorly soluble silymarin drug loading79,80. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time an FCE-based green ZnFe2O4 nano-biocomposite has been used to incorporate the silymarin drug. Therefore, 5 h of loading reaction is enough to attain the top of loading capacity in future silymarin drug loading experiments in the ZnFe2O4 NCs system. Consequently, this investigation validates ZnFe2O4 NCs’ noteworthy ability to encapsulate a substantial quantity of silymarin.

In vitro drug release assay

Silymarin was chosen as a model drug to explore the potential uses of ZnFe2O4 NCs as nanocarriers, because ZnFe2O4 NCs are stable at physiological pH 7.4 and break down at acidic pH 5. It’s crucial to emphasize that, while controlled delivery at different rates has been observed in both pHs, faster release has only been observed in acidic pH81. As illustrated in Fig. 4c at pH 7.4, PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 exhibited a slow drug release in the first 2 h of 8.85%, at 12 h the rate was 26.48% and at 24 h it was 47.35%. While at pH 5.0, high drug release was noted as in the first 2 h of it was 16.11%, at 12 h 57.29% and at 24 h 73.21%.

In an acidic environment, silymarin drug release from PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 is because the acidic conditions are associated with endosomes and lysosomes within cells, which may aid in the active release of drugs82. The intensity of the bonding contacts between the silymarin drug’s H and -OH groups might be responsible for the pH-dependent release. Conversely, the PEG coating may separate from the PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 hybrids as a result of the electrostatic interaction’s instability in a mildly acidic atmosphere, which would hasten the release of silymarin83.

Toxicity of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 NCs

To evaluate the toxicity of the prepared ZnFe2O4 NCs, rats were treated with NCs for 7 days. During this period, no rats died in the control group or the PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 treated groups. The current study found that model animals did not die when they ingested 1000 μg/kg of ZnFe2O4 NCs and 1500 μg/kg of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4, suggesting that this may be the maximal safe dose that does not result in any physical alterations. No significant variation was seen in the weight of control and nanocomposites exposed rats throughout the trial Table S1.

Hematological parameters

In the current study, it was observed that, in comparison to the control group (T1), the rats treated with ZnFe2O4 NCs (T2) for seven days showed no changes in their blood parameters. On the other hand, in contrast to the control group, the group treated with CCl4 (T3), showed that the levels of various blood parameters such as hemoglobin (HGB), red blood cells (RBC), hematocrit (HCT), hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) was decreased. While white blood cells (WBC), lymphocytes (LYM), and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) increased. The alterations in the levels of these blood parameters are brought on by liver dysfunction and oxidative stress caused by CCl4. In group T4, after 24 h intoxicity of CCl4 followed by treatment with silymarin (100 mg/kg body weight) for 7 days, it was noticed that the level of HGB, RBC, HCT, MCHC, and MCH in blood was increased while the level of WBC, LYM, and MCV was decreased. This is because of the antioxidative protective effect of silymarin. The groups T5 and T6 were treated with 500 µg/kg body weight and 1500 µg/kg body weight doses of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 respectively, followed by the 24-h toxicity of CCl4. It was examined that PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 mitigated the CCl4-induced toxicity rate and gradually increased HGB, RBC, HCT, MCHC, and MCH levels, and gradually decreased WBC, LYM, and MCV levels in the blood Table 1. The T6 group, which received 1500 µg, had the best outcomes, with blood parameter levels that were comparable to those of the control group. It is shown that, at far lower concentrations of 1500 µg/kg body weight than the free silymarin 100 mg/kg body weight, PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 produced meaningful results (Fig. 5a). These results are supported by the previously published work84,85.

Comparison of various (a) hematological parameters, (b) serum parameters and (c) oxidative and antioxidative biomarkers in liver of treated rats. (Asterisk “*” shows the significant variation in hematological, serological parameters, and antioxidant enzymes of different treated groups from the control group).

Analysis of serum biochemistry

Table S4 lists the concentrations of several liver biochemical indicators in each group’s serum. There was no significant difference observed in the serum concentrations of total bilirubin, AST, and ALT between rats treated with ZnFe2O4 NCs at 1000 µg/kg body weight alone (T2) and control (T1). In comparison to the control group (T1), the results showed an increase in bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) following CCl4 treatment (T3). In T4, exposure to silymarin (100 mg/kg body weight) attenuated the rise of serum biomarkers bilirubin, AST, and ALT levels caused by CCl4 and returned them to values comparable to the control group. The co-administration of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 at low dosages of 500 µg/kg body weight (T5), and 1500 µg/kg body weight (T6) effectively restored the level of these biomarkers to the T1 group (Fig. 5b). The same results were observed by Jasim et al., who used silymarin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles to treat CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity86, and Akheratdoost et al., chitosan NPS loaded wth silymarin to treat diet-induced hyperlipidemia rats87.

Antioxidant enzymes in the liver

An analysis of the liver antioxidant enzyme status of treated rats is shown in Table S5. The rats treated with CCl4 (T3) showed tissue-specific damage and a notable decrease in the concentration of antioxidant enzymes, including peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT), and superoxide dismutase (SOD). The rats (T4) treated with traditional medicine, silymarin (100 mg/kg body weight), were spared liver damage, as indicated by a markedly increased level of these previously mentioned indicators. In groups T5 and T6, rats were exposed to PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 at dosages of 500 µg/kg body weight and 1500 µg/kg body weight, respectively, and the concentration of these antioxidant indicators was brought back to control values (T1). When rats treated with CCl4 were given a greater dosage of nano-silymarin (1500 µg/kg body weight), the impact became more apparent, and the degree of protection reached was similar to that of silymarin/CCl4 treatment (T4). However, rats exposed to pure ZnFe2O4 NCs (100 mg/kg body weight) maintained the level of these enzymes at the same level as control rats (Fig. 5c). A low dosage of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 was found to produce more effective results than a large dosage of the silymarin-based medication. The same results were noted by Alaryani, who treated CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity with silymarin-loaded zinc nanoparticles88.

Oxidative biomarkers in liver

Table S5 demonstrates that rats exposed to CCl4 (T3) exhibited higher levels of oxidative biomarkers (TBARS and ROS) in their liver samples than the unexposed rats (T1). In T4, treated with silymarin 100 mg/kg body weight, exhibited a notable restoration of these biomarkers by mitigating the hepatotoxicity induced by CCl4. Conversely, these parameters were progressively restored to those of control rats by co-administering PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4at dosages of 500 µg/kg body weight and 1500 µg/kg body weight to CCl4-exposed rats. On liver parameters, a 1500 µg/kg body weight dose of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 demonstrated therapeutic effects similar to silymarin 100 mg/kg body weight. It was shown that the modest dose of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 produced more effective results than the high dose of the traditional medication silymarin. Moreover, rats exposed to a 100 mg/kg body weight dose of ZnFe2O4 NCs did not produce any effect on these biomarkers (Fig. 5c). The same results were observed in Rabey’s work; he treated CCl4-induced neurotoxicity in rats with silymarin and vanillic acid loaded silver NPs89. Demerdash’s work also showed the same results, in which silymarin-loaded chitosan particles were used to treat aluminium-induced oxidative stress and hyperlipidemia in wistar albino rats90.

Microscopic histopathological examination

Figure 6 depicts the histological changes in the H&E-stained coronal slices of the liver. The liver tissues of the unexposed rats (T1) showed normal liver structures under a microscope, including the portal hepatic area, the lobule structure, and the hepatocytes. When hepatic tissues treated with CCl4 (T3) were examined under a microscope, they showed signs of severe histopathological abnormalities such as pyknosis, congestion, nuclear hypertrophy, hemorrhages, karyolysis, karyorrhexis, ceroid development, and vacuolar degeneration. The liver tissues also seemed fatty and pale yellow in color Table 2.

Photomicrograph showing different histopathological alterations in the liver of NCs treated and untreated rats. (T1-T2) Liver with normal histoarchitecture of hepatocytes (T3) severe inflammatory exudate (asterisk), atrophy of nuclei and hepatocytes and hypertrophy of cytoplasm (arrowhead) (T4) severe inflammatory exudate (asterisk), atrophy of nuclei and hepatocytes and hypertrophy of cytoplasm (arrowhead) necrosis of hepatocytes (arrow) (T5) severe inflammatory exudate (asterisk), atrophy of nuclei and hepatocytes and hypertrophy of cytoplasm (arrowhead) increased sinusoidal spaces (double asterisk) (T6) increased severe inflammatory exudate (asterisk), fatty degenerations (arrow), atrophy of nuclei and hepatocytes and hypertrophy of cytoplasm (arrowhead). 400X.

When ZnFe2O4 NCs were administered alone at a dose of 1000 µg/kg body weight, the normal histological characteristics of the liver tissues were preserved, just like in the T1. In (T4), after concurrently administering silymarin (100 mg/kg body weight), the histological alterations caused by CCl4 were reversed, revealing normal liver morphology characterized by distinct and well-defined hepatocytes. Likewise, co-administration with PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 at dosages of 500 µg/kg body weight and 1500 µg/kg body weight resulted in the recovery of hepato-pathological damage in rats that had been intoxicated with CCl4. Our results are good in match with Abdullah et al., who used silymarin conjugated gold nanoparticles to treat hepatic fibrosis in rats69, and Alamri et al., who treated CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in male rats with the help of silymarin-loaded AgNPs91.

Comet assay

Figure 7a. shows the findings of the genotoxicity evaluation in isolated hepatic cells of rats treated with CCl4, silymarin, and varying concentrations of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 nanocomposite. The results showed that CCl4 had a far higher genotoxic potential, as seen by the higher frequency of DNA damage in liver cells. Figure 7b. illustrates the protective effects of varying PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 dosages on genotoxicity caused by CCl4-toxicity in rat liver cells. Due to DNA damage in the liver (6.19 ± 0.22), the isolated cells of CCl4-induced toxicity (T3), rats had a significantly greater DNA damage percentile by electrophoresis when compared to other groups (P ≤ 0.05). A significant gradual decreased comet formation was examined in rats treated with PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 and CCl4 such in the liver (4.26 ± 0.21) for the 500 µg treated group (T5) and (3.14 ± 0.35) for 1500 µg treated group (T6). Co-administration of silymarin and CCl4 (T4), mitigated the DNA toxicity and brought comet readings back to the kidney’s control range (3.49 ± 0.14). Rats treated with ZnFe2O4 NCs alone showed a non-significant rise in comet value (2.31 ± 0.14) compared to the normal group Table S6. According to our research, a significantly higher frequency of DNA damage (%) in the liver in CCl4 exposed rates is observed. CCl4 elevates the free radical generation which in turn results in oxidative stress and DNA damage. Our results are in line with a previous study that discovered DNA damage in many rat organs after exposure to CCl4. Following the administration of a 1500 µg/kg dose of PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 nano-drug, the toxicity induced by CCl4 was reduced, and all altered parameters returned to normal, comparable to the normal group. Saif et al., found similar results in CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity amelioration with nano-silymarin57,92.

Photos showing DNA-damaged material fluorescing around a nucleus, making a “tail” of variable length along the electric field in isolated cells of the liver of rats treated with CCl4 and PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4. Severe DNA damage (%) in the CCl4-treated rats. Severe to mild decreases in frequency and intensity of DNA damage (%) in PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 treated rats. H & E stain; 100X (a). DNA damage (%) mitigation with different PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 doses in the liver (b).

Conclusions

The results of this study propose that ZnFe2O4 NCs are for boosting silymarin’s solubility, absorption, and in vivo hepatoprotective benefits. The coprecipitation approach was used to manufacture PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 nanocomposites. When compared with the conventional medication, the optimized PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 formulation substantially enhanced silymarin’s solubility and attained in vitro drug release for twenty-four hours. Additionally, compared to the plain medication, the optimized PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 synthesis showed upgraded hepatoprotective properties in a rat model of CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity. This was demonstrated by the successful recovery of normal levels of antioxidant enzymes and the reduction of all cellular alterations caused by CCl4-intoxication. Additionally, the reduction in DNA damage level validated the therapeutic effect of nano silymarin. In the end, our findings show how effectively silymarin-loaded nanocomposites (PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4) enhance the pharmacological effects of less soluble medication silymarin by studying its solubility and bioavailability for further confirmation. The main limitation in the current work is that the study primarily focused on in vitro and in vivo evaluations using a CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity rat model, which may not fully represent clinical scenarios in humans. Further pharmacokinetic and long-term toxicity studies are required to confirm the safety and efficacy of the developed formulation. Additionally, while the PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 nanocomposite demonstrated controlled drug release, further optimization may be needed to enhance targeted delivery and minimize potential systemic effects. Future studies should further explore the scalability and stability of this nanocarrier system for potential pharmaceutical applications.

Statement on experimental research

The methods comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and domestic legislation of Pakistan.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Crystallography Open Database (COD) repository, with accession number 9005110.

Change history

27 November 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29407-2

References

Subramaniyan, V., Lubau, N. S. A., Mukerjee, N. & Kumarasamy, V. Alcohol-induced liver injury in signalling pathways and curcumin’s therapeutic potential. Toxicol. Rep. 11, 355–367 (2023).

Mitchell, M. J. et al. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 20, 101–124 (2021).

Yu, H. et al. Designing a Silymarin Nanopercolating System Using CME@ZIF-8: An Approach to Hepatic Injuries. ACS Omega https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c08494 (2023).

Saif, M. S. et al. Advancing Nanoscale Science: Synthesis and Bioprinting of Zeolitic Imidazole Framework-8 for Enhanced Anti-Infectious Therapeutic Efficacies. Biomedicines 11, 2832 (2023).

Huang, L. et al. Bile acids metabolism in the gut-liver axis mediates liver injury during lactation. Life Sci. 338, 122380 (2024).

Hamed, K. A. et al. Assessing the Efficacy of Fenugreek Saponin Nanoparticles in Attenuating Nicotine-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Male Rats. ACS Omega 8, 42722–42731 (2023).

Ali, A. et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Silica, Silver-Silica, and Zinc Oxide-Silica Nanoparticles for Evaluation of Blood Biochemistry, Oxidative Stress, and Hepatotoxicity in Albino Rats. ACS Omega 8, 20900–20911 (2023).

Tian, J., An, M., Zhao, X., Wang, Y. & Hasan, M. Advances in Fluorescent Sensing Carbon Dots: An Account of Food Analysis. ACS Omega https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c07986 (2023).

Huang, L., Chen, R., Luo, J., Hasan, M. & Shu, X. Synthesis of phytonic silver nanoparticles as bacterial and ATP energy silencer. J. Inorg. Biochem. 231, 111802 (2022).

Hasan, M., Mustafa, G., Iqbal, J., Ashfaq, M. & Mahmood, N. Quantitative proteomic analysis of HeLa cells in response to biocompatible Fe2C@C nanoparticles: 16O/18O-labelling & HPLC-ESI-orbit-trap profiling approach. Toxicol. Res. (Camb) https://doi.org/10.1039/c7tx00248c (2018).

Mustafa, G. et al. A comparative proteomic analysis of engineered and bio synthesized silver nanoparticles on soybean seedlings. J. Proteom. 224, 103833 (2020).

Cao, D. et al. Lipid-coated ZnO nanoparticles synthesis, characterization and cytotoxicity studies in cancer cell. Nano Converg. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40580-020-00224-9 (2020).

Li, C. et al. A Metabolic Reprogramming Amino Acid Polymer as an Immunosurveillance Activator and Leukemia Targeting Drug Carrier for T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Adv. Sci. 9, 2104134 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Sensitive and low-power metal oxide gas sensors with a low-cost microelectromechanical heater. ACS Omega 6, 1216–1222 (2021).

Tran, H. N. & Gautam, V. Micro/nano devices for integration with human brain organoids. Biosens. Bioelectron. 218, 114750 (2022).

Hasan, M. et al. Biological entities as chemical reactors for synthesis of nanomaterials: Progress, challenges and future perspective. Mater. Today Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtchem.2018.02.003 (2018).

Hasan, M. et al. Crest to trough cellular drifting of green-synthesized zinc oxide and silver nanoparticles. ACS Omega 7, 34770–34778 (2022).

Manzoor, Y. et al. Incubating green synthesized iron oxide nanorods for proteomics-derived motif exploration: A fusion to deep learning oncogenesis. ACS Omega https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c05948 (2022).

Batool, S. et al. Green synthesized ZnO-Fe2O3-Co3O4 nanocomposite for antioxidant, microbial disinfection and degradation of pollutants from wastewater. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 105, 104535 (2022).

Qasim, S. et al. Green synthesis of iron oxide nanorods using Withania coagulans extract improved photocatalytic degradation and antimicrobial activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2020.111784 (2020).

Sun, D. Y. et al. Unlocking the full potential of memory T cells in adoptive T cell therapy for hematologic malignancies. Int. Immunopharmacol. 144, 113392 (2025).

Zheng, P. et al. A multi-omic analysis reveals that Gamabufotalin exerts anti-hepatocellular carcinoma effects by regulating amino acid metabolism through targeting STAMBPL1. Phytomedicine 135, 156094 (2024).

Kamran, S. H., Shoaib, R. M., Ahmad, M., Ishtiaq, S. & Anwar, R. Antidiabetic and renoprotective effect of Fagonia cretica L. methanolic extract and Citrus paradise Macfad. juice in alloxan induced diabetic rabbits. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 5, 365–380 (2017).

Patel, D. & Kumar, V. Protective effects of fagonia cretica L. Extract in cafeteria diet induced obesity in wistar rats. J. Nat. Remedies 20, 185–190 (2020).

Iqbal, P., Ahmed, D. & Asghar, M. N. A comparative in vitro antioxidant potential profile of extracts from different parts of Fagonia cretica. As. Pac. J. Trop. Med. 7, S473–S480 (2014).

Li, J. et al. Purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) polysaccharide attenuates carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver injury by modulating the gut microbiota in mice. Genomics 117, 110983 (2025).

Naeem, K., Yawar, W., Muhammad, B. & Rehana, I. Assessment of macronutrients and heavy metals in Fagonia cretica linn of Pakistan by atomic spectroscopy. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 28, 177–185 (2014).

Hasan, M. et al. Bioinspired synthesis of zinc oxide nano-flowers: A surface enhanced antibacterial and harvesting efficiency. Mater. Sci. Eng., C https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2020.111280 (2021).

Kumar, S. A., Prabhakar, R., Vikram, N. R., Dinesh, S. P. S. & Rajeshkumar, S. Antioxidant activity of silymarin/hydroxyapatite/chitosan nano composites-an in vitro study. Int. J. Dent. Oral Sci. https://doi.org/10.19070/2377-8075-21000278 (2021).

Ahmed, M. A., Tayawi, H. M. & Ibrahim, M. K. Protective effect of silymarin against kidney injury induced by carbon tetrachloride in male rats. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 33, 127–130 (2019).

Borah, A. et al. Neuroprotective potential of silymarin against CNS disorders: Insight into the pathways and molecular mechanisms of action. CNS Neurosci. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.12175 (2013).

Clichici, S. et al. Hepatoprotective effects of silymarin coated gold nanoparticles in experimental cholestasis. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 115, 111117 (2020).

Lv, F. et al. Optimized luteolin loaded solid lipid nanoparticle under stress condition for enhanced bioavailability in rat plasma. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 16, 9443–9449 (2016).

Dang, H. et al. Luteolin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles synthesis, characterization, & improvement of bioavailability, pharmacokinetics in vitro and vivo studies. J. Nanopart. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-014-2347-9 (2014).

Hasan, M. et al. LX loaded nanoliposomes synthesis, characterization and cellular uptake studies in H2O2 stressed SH-SY5Y cells. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2014.8201 (2014).

Li, H. et al. The effects of Chuanxiong on the pharmacokinetics of warfarin in rats after biliary drainage. J. Ethnopharmacol. 193, 117–124 (2016).

Al-Hartomy, O. A., Khasim, S., Roy, A. & Pasha, A. Highly conductive polyaniline/graphene nano-platelet composite sensor towards detection of toluene and benzene gases. Appl. Phys. A 125, 12 (2018).

Nagesh, P. K. B. et al. PSMA targeted docetaxel-loaded superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for prostate cancer. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 144, 8–20 (2016).

Pan, Q. et al. Lactobionic acid and carboxymethyl chitosan functionalized graphene oxide nanocomposites as targeted anticancer drug delivery systems. Carbohydr. Polym. 151, 812–820 (2016).

Hussain, R. et al. Casting zinc oxide nanoparticles using fagonia blend microbial arrest. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-022-04152-8 (2022).

Zulfiqar, H. et al. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using: Fagonia cretica and their antimicrobial activities. Nanoscale Adv https://doi.org/10.1039/c8na00343b (2019).

Abdel Maksoud, M. I. A., El-Sayyad, G. S., El-Bastawisy, H. S. & Fathy, R. M. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of silver-decorated zinc ferrite nanoparticles synthesized by a gamma irradiation-coupled sol-gel method against some pathogenic bacteria from medical operating room surfaces. RSC Adv. 11, 28361–28374 (2021).

Khan, A. U. et al. Iron-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles-triggered elicitation of important phenolic compounds in cell cultures of Fagonia indica. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 147, 287–296 (2021).

Luo, F. et al. PEGylated dihydromyricetin-loaded nanoliposomes coated with tea saponin inhibit bacterial oxidative respiration and energy metabolism. Food Funct. 12, 9007–9017 (2021).

Yazdi, J. R. et al. Folate targeted PEGylated liposomes for the oral delivery of insulin: In vitro and in vivo studies. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111203 (2020).

Perinelli, D. R., Cespi, M., Bonacucina, G. & Palmieri, G. F. PEGylated polylactide (PLA) and poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) copolymers for the design of drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Investig. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40005-019-00442-2 (2019).

Hasan, M. et al. Physiological and anti-oxidative response of biologically and chemically synthesized iron oxide: Zea mays a case study. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04595 (2020).

Khan, S. et al. Biosynthesized iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3o4 nps) mitigate arsenic toxicity in rice seedlings. Toxics. 9, 2 (2021).

Üstün, E., Önbaş, S. C., Çelik, S. K., Ayvaz, M. Ç. & Şahin, N. Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles by using ficus carica leaf extract and its antioxidant activity. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 12, 2108–2116 (2022).

Uddin, S. et al. Green synthesis of nickel oxide nanoparticles using leaf extract of Berberis balochistanica: Characterization, and diverse biological applications. Microsc. Res. Tech. 84, 2004–2016 (2021).

Krishnan, S. et al. Facile green synthesis of ZnFe2O4/rGO nanohybrids and evaluation of its photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutant, photo antibacterial and cytotoxicity activities. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 611, 125835 (2021).

Rathore, P. et al. Collagen Nanoparticle-Mediated Brain Silymarin Delivery: An Approach for Treating Cerebral Ischemia and Reperfusion-Induced Brain Injury. Front. Neurosci. 14, 538404 (2020).

Yousaf, A. M., Malik, U. R., Shahzad, Y., Mahmood, T. & Hussain, T. Silymarin-laden PVP-PEG polymeric composite for enhanced aqueous solubility and dissolution rate: Preparation and in vitro characterization. J. Pharm. Anal. 9, 34–39 (2019).

Saif, M. S. et al. Potential of CME@ZIF-8 MOF Nanoformulation: Smart Delivery of Silymarin for Enhanced Performance and Mechanism in Albino Rats. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsabm.4c01019 (2024).

Shriram, R. G. et al. Phytosomes as a Plausible Nano-Delivery System for Enhanced Oral Bioavailability and Improved Hepatoprotective Activity of Silymarin. Pharmaceuticals 15, 790 (2022).

Hussein-Al-Ali, S. H. et al. Preparation and characterisation of ciprofloxacin-loaded silver nanoparticles for drug delivery. IET Nanobiotechnol. 16, 92–101 (2022).

Saif, M. S. Improving the bioavailability of three-dimensional ZIF-8 MOFs against carbon tetrachloride-induced brain and spleen toxicity in rats. Mater. Chem. Phys. 328, 129997 (2024).

Uchendu, N. O., Ezechukwu, C. S. & Ezeanyika, L. U. S. Biochemical Profile of Albino Rats with Experimentally Induced Metabolic Syndrome fed Diet Formulations of Cnidoscolus Aconitifolius, Gongronema Latifolium and Moringa Oleifera Leaves. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2021, 1–11 (2021).

Ghaffar, A. et al. Assessment of genotoxic and pathologic potentials of fipronil insecticide in Labeo rohita (Hamilton, 1822). Toxin Rev. 40, 1289–1300 (2021).

Zhao, L. et al. Cadmium activates the innate immune system through the AIM2 inflammasome. Chem. Biol. Interact 399, 111122 (2024).

Rehman, T. et al. Exposure to heavy metals causes histopathological changes and alters antioxidant enzymes in fresh water fish (Oreochromis niloticus). Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2021, 1–11 (2021).

Marklund, S. & Marklund, G. Involvement of the Superoxide Anion Radical in the Autoxidation of Pyrogallol and a Convenient Assay for Superoxide Dismutase. Eur. J. Biochem. 47, 469–474 (1974).

Hallaji, B., Haghighi, M., Abolghasemi, R. & Mozafarian, M. Effect of foliar applications of aminolevulinic acid (bulk and nano-encapsulated) on bell pepper under heat stress. Plant Stress 12, 100477 (2024).

He, J. et al. Graveoline attenuates D-GalN/LPS-induced acute liver injury via inhibition of JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 177, 117163 (2024).

Yassin, N. Y. S. et al. Tackling of Renal Carcinogenesis in Wistar Rats by Silybum marianum Total Extract, Silymarin, and Silibinin via Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis, Nrf2, PPAR γ, NF- κ B, and PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathways. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 7665169 (2021).

Ali, A. et al. Exploring the impact of silica and silica-based nanoparticles on serological parameters, histopathology, organ toxicity, and genotoxicity in Rattus norvegicus. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 19, 100551 (2024).

Golsefidi, M. A. et al. Hydrothermal method for synthesizing ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles, photo-degradation of Rhodamine B by ZnFe2O4 and thermal stable PS-based nanocomposite. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 27, 8654–8660 (2016).

Rajnochová Svobodová, A. et al. UVA-photoprotective potential of silymarin and silybin. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 310, 413–424 (2018).

Abdullah, A. S. et al. Preparation and characterization of silymarin-conjugated gold nanoparticles with enhanced anti-fibrotic therapeutic effects against hepatic fibrosis in rats: Role of micrornas as molecular targets. Biomedicines 9, 1767 (2021).

Seyfoori, A., Ebrahimi, S. A. S., Omidian, S. & Naghib, S. M. Multifunctional magnetic ZnFe 2 O 4 -hydroxyapatite nanocomposite particles for local anti-cancer drug delivery and bacterial infection inhibition: An in vitro study. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 96, 503–508 (2019).

Saif, M. S. et al. Phyto-reflexive Zinc Oxide Nano-Flowers synthesis: An advanced photocatalytic degradation and infectious therapy. J. Market. Res. 13, 2375–2391 (2021).

Sasaki, K. et al. Thin ZIF-8 Nanosheets Synthesized in Hydrophilic TRAPs. Dalton Trans. 50, 10394–10399 (2021).

Tomar, D. & Jeevanandam, P. Synthesis of ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles with different morphologies via thermal decomposition approach and studies on their magnetic properties. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 564, 170033 (2022).

Nguyen, L. T. T. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and application of ZnFe2O4@ZnO nanoparticles for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B under visible-light illumination. Environ. Technol. Innov. 25, 102130 (2022).

Asri, M. et al. Sustainable green synthesis of ZnFe2O4@ZnO nanocomposite using Oleaster tree bark methanolic extract for photocatalytic degradation of aqueous humic acid in the presence of UVc irradiation. Aqua Water Infrastructure, Ecosyst. Soc. 72, 1800–1814 (2023).

Ge, X. et al. Recent development of metal-organic framework nanocomposites for biomedical applications. Biomaterials 281, 121322 (2021).

Choi, E., Lee, C. H. & Kim, D. W. Influence of Humidity and Heating Rate on the Continuous ZIF Coating during Hydrothermal Growth. Membranes (Basel) 13, 414 (2023).

Veiko, A. G., Lapshina, E. A. & Zavodnik, I. B. Comparative analysis of molecular properties and reactions with oxidants for quercetin, catechin, and naringenin. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 476, 4287–4299 (2021).

He, S. et al. Metal-organic frameworks for advanced drug delivery. Acta Pharm. Sinica B. 11, 2362–2395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.019 (2021).

Simon-Yarza, T. et al. A Smart Metal-Organic Framework Nanomaterial for Lung Targeting. Angewandte Chemie – Int. Edition 56, 15565–15569 (2017).

Abdul Latip, A. F., Hussein, M. Z., Stanslas, J., Wong, C. C. & Adnan, R. Release behavior and toxicity profiles towards A549 cell lines of ciprofloxacin from its layered zinc hydroxide intercalation compound. Chem. Cent. J. 7, 119 (2013).

Hsu, C. Y. et al. An overview of nanoparticles in drug delivery: Properties and applications. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 46, 233–270 (2023).

Sun, S. et al. Drug delivery systems based on polyethylene glycol hydrogels for enhanced bone regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1117647 (2023).

Abdullah, A. S. et al. Green Synthesis of Silymarin-Chitosan Nanoparticles as a New Nano Formulation with Enhanced Anti-Fibrotic Effects against Liver Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 5420 (2022).

Kar, P. et al. β-sitosterol conjugated silver nanoparticle-mediated amelioration of CCl4-induced liver injury in Swiss albino mice. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 34, 102113 (2022).

Jasim, N. Y. & Ghadhban, R. F. Frontiers in Health Informatics. Front. Health Inf. 13, 587–598 (2024).

Akheratdoost, V., Panahi, N., Safi, S., Mojab, F. & Akbari, G. Protective effects of silymarin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles in the diet-induced hyperlipidemia rat model. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 27, 725–732 (2024).

Alaryani, F. S. et al. Molecular mechanisms of conjugated zinc nano-particles for nano drug delivery against hepatic cirrhosis in CCl4-induced rats model. Rend. Lincei. Sci. Fis. Nat. 34, 1133–1143 (2023).

El Rabey, H. A. et al. Silymarin and Vanillic Acid Silver Nanoparticles Alleviate the Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Male Rats. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 4120553 (2023).

El-Demerdash, F. M., Ahmed, M. M., El-Sayed, R. A., Mohemed, T. M. & Gerges, M. N. Nephroprotective effects of silymarin and its fabricated nanoparticles against aluminum-induced oxidative stress, hyperlipidemia, and genotoxicity. Environ. Toxicol. 39, 3746–3759 (2024).

Alamri, E. S. et al. Enhancement of the Protective Activity of Vanillic Acid against Tetrachloro-Carbon (CCl4) Hepatotoxicity in Male Rats by the Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs). Molecules 27, 8308 (2022).

Saif, M. S. et al. Potential of CME@ZIF-8 MOF Nanoformulation: Smart Delivery of Silymarin for Enhanced Performance and Mechanism in Albino Rats. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 7, 6919–6931 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We all authors would like to acknowledge, The Islamia University Bahawalpur, Pakistan, National Research Program for University (NRPU) for Higher Education Commission, Pakistan (Grant ID: 9458).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Waqas and M. saqib Saif designed the study. S. Batool and T. Tariq prepared the samples and conducted the tests/analyses. R. hussain, G. Mustafa, M. Hasan, and M. Mahmood Ahmed wrote the manuscript. M. Hasan and M. Ghorbanpour revised the text critically. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All methods performed in this study were in compliance with the relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Preparation of the rat for in vivo studies

All animal experiments were conducted by the Regulations Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (published by the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research) and are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines for the reporting of animal experiments.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the captions of Figure 2, in which ‘ZnFe2O4 ’ and ‘PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O’ were incorrectly given as ‘ZnFe’ and ‘PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe’. Additionally, in figure 3, wrong photos were uploaded for PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 SEM (3b) and particle size distribution (3d).

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Waqas, M., Saif, M.S., Batool, S. et al. Green PEGylated-Sily@ZnFe2O4 nanocomposites for amelioration of ROS and DNA damage in rat liver. Sci Rep 15, 28461 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14126-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14126-5